Viktor frankl meaning in life

Viktor Frankl on the Human Search for Meaning – The Marginalian

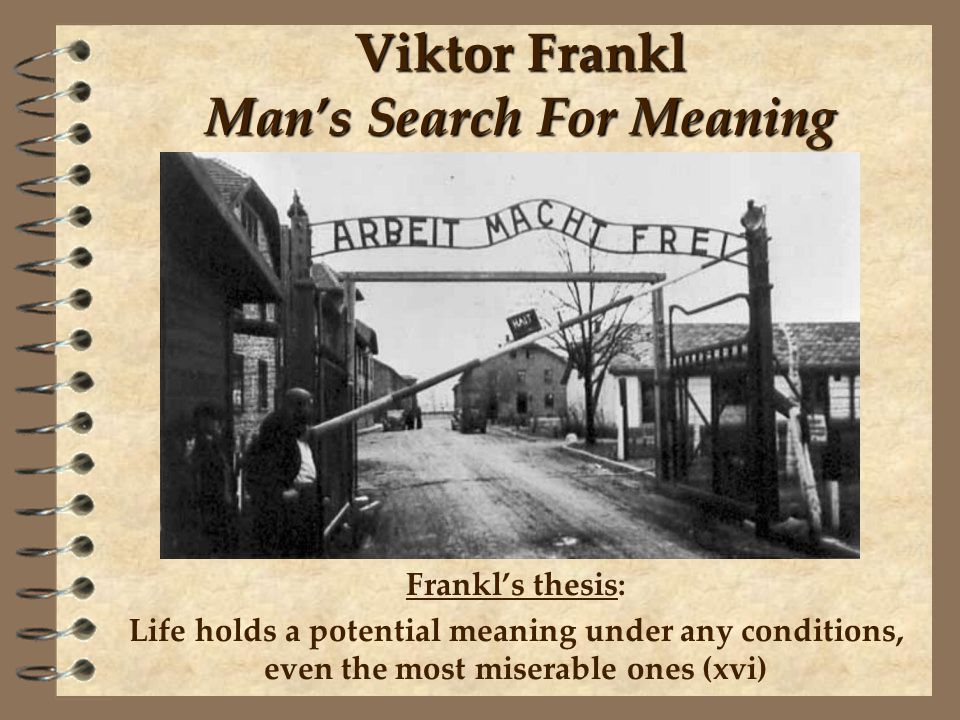

Celebrated Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl (March 26, 1905–September 2, 1997) remains best-known for his indispensable 1946 psychological memoir Man’s Search for Meaning (public library) — a meditation on what the gruesome experience of Auschwitz taught him about the primary purpose of life: the quest for meaning, which sustained those who survived.

For Frankl, meaning came from three possible sources: purposeful work, love, and courage in the face of difficulty.

In examining the “intensification of inner life” that helped prisoners stay alive, he considers the transcendental power of love:

Love goes very far beyond the physical person of the beloved. It finds its deepest meaning in his spiritual being, his inner self. Whether or not he is actually present, whether or not he is still alive at all, ceases somehow to be of importance.

![]()

Frankl illustrates this with a stirring example of how his feelings for his wife — who was eventually killed in the camps — gave him a sense of meaning:

We were at work in a trench. The dawn was grey around us; grey was the sky above; grey the snow in the pale light of dawn; grey the rags in which my fellow prisoners were clad, and grey their faces. I was again conversing silently with my wife, or perhaps I was struggling to find the reason for my sufferings, my slow dying. In a last violent protest against the hopelessness of imminent death, I sensed my spirit piercing through the enveloping gloom. I felt it transcend that hopeless, meaningless world, and from somewhere I heard a victorious “Yes” in answer to my question of the existence of an ultimate purpose. At that moment a light was lit in a distant farmhouse, which stood on the horizon as if painted there, in the midst of the miserable grey of a dawning morning in Bavaria. “Et lux in tenebris lucet” — and the light shineth in the darkness.

For hours I stood hacking at the icy ground. The guard passed by, insulting me, and once again I communed with my beloved. More and more I felt that she was present, that she was with me; I had the feeling that I was able to touch her, able to stretch out my hand and grasp hers. The feeling was very strong: she was there. Then, at that very moment, a bird flew down silently and perched just in front of me, on the heap of soil which I had dug up from the ditch, and looked steadily at me.

Of humor, “another of the soul’s weapons in the fight for self-preservation,” Frankl writes:

Lithograph by Leo Haas, Holocaust artist who survived Theresienstadt and Auschwitz (public domain)It is well known that humor, more than anything else in the human make-up, can afford an aloofness and an ability to rise above any situation, even if only for a few seconds. … The attempt to develop a sense of humor and to see things in a humorous light is some kind of a trick learned while mastering the art of living. Yet it is possible to practice the art of living even in a concentration camp, although suffering is omnipresent.

After discussing the common psychological patterns that unfold in inmates, Frankl is careful to challenge the assumption that human beings are invariably shaped by their circumstances. He writes:

But what about human liberty? Is there no spiritual freedom in regard to behavior and reaction to any given surroundings? … Most important, do the prisoners’ reactions to the singular world of the concentration camp prove that man cannot escape the influences of his surroundings? Does man have no choice of action in the face of such circumstances?

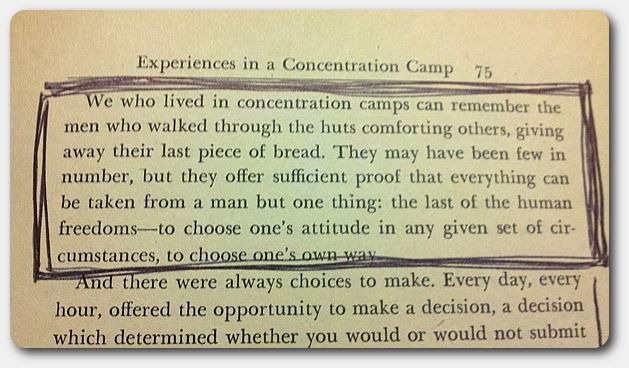

We can answer these questions from experience as well as on principle. The experiences of camp life show that man does have a choice of action. … Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress.

[…]

Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.

Much like William James did in his treatise on habit, Frankl places this notion of everyday choice at the epicenter of the human experience:

Every day, every hour, offered the opportunity to make a decision, a decision which determined whether you would or would not submit to those powers which threatened to rob you of your very self, your inner freedom; which determined whether or not you would become the plaything of circumstance, renouncing freedom and dignity to become molded into the form of the typical inmate.

Like Henry Miller and Philip K. Dick, Frankl recognizes suffering as an essential piece not only of existence but of the meaningful life:

If there is a meaning in life at all, then there must be a meaning in suffering. Suffering is an ineradicable part of life, even as fate and death. Without suffering and death human life cannot be complete.

The way in which a man accepts his fate and all the suffering it entails, the way in which he takes up his cross, gives him ample opportunity — even under the most difficult circumstances — to add a deeper meaning to his life.

It may remain brave, dignified and unselfish. Or in the bitter fight for self-preservation he may forget his human dignity and become no more than an animal. Here lies the chance for a man either to make use of or to forgo the opportunities of attaining the moral values that a difficult situation may afford him. And this decides whether he is worthy of his sufferings or not. … Such men are not only in concentration camps. Everywhere man is confronted with fate, with the chance of achieving something through his own suffering.

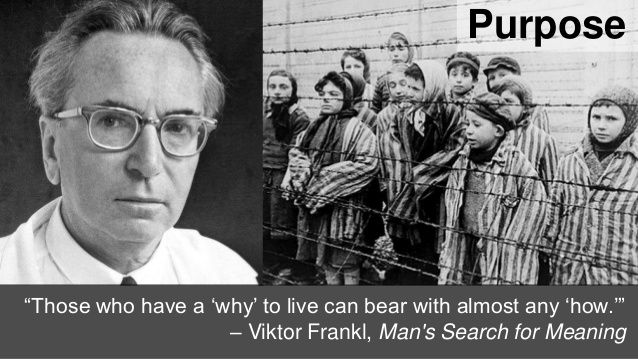

In working as a psychiatrist to the inmates, Frankl found that the single most important factor in cultivating the kind of “inner hold” that allowed men to survive was teaching them to hold in the mind’s grip some future goal. He cites Nietzsche’s, who wrote that “He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how,” and admonishes against generalization:

Lithograph by Leo Haas, Holocaust artist who survived Theresienstadt and Auschwitz (public domain)Woe to him who saw no more sense in his life, no aim, no purpose, and therefore no point in carrying on.

He was soon lost. The typical reply with which such a man rejected all encouraging arguments was, “I have nothing to expect from life any more.” What sort of answer can one give to that?

What was really needed was a fundamental change in our attitude toward life. We had to learn ourselves and, furthermore, we had to teach the despairing men, that it did not really matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us. We needed to stop asking about the meaning of life, and instead to think of ourselves as those who were being questioned by life — daily and hourly. Our answer must consist, not in talk and meditation, but in right action and in right conduct. Life ultimately means taking the responsibility to find the right answer to its problems and to fulfill the tasks which it constantly sets for each individual.

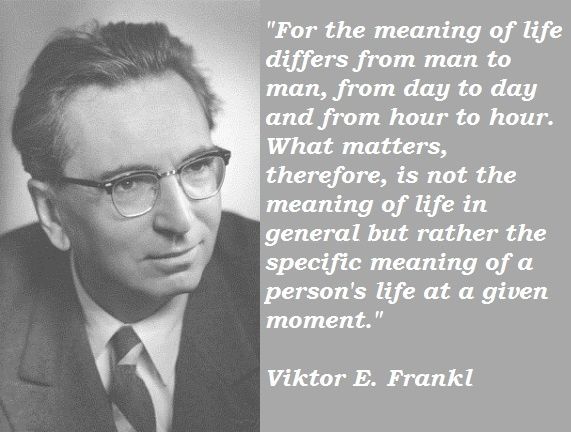

These tasks, and therefore the meaning of life, differ from man to man, and from moment to moment. Thus it is impossible to define the meaning of life in a general way.

Questions about the meaning of life can never be answered by sweeping statements. “Life” does not mean something vague, but something very real and concrete, just as life’s tasks are also very real and concrete. They form man’s destiny, which is different and unique for each individual. No man and no destiny can be compared with any other man or any other destiny. No situation repeats itself, and each situation calls for a different response. Sometimes the situation in which a man finds himself may require him to shape his own fate by action. At other times it is more advantageous for him to make use of an opportunity for contemplation and to realize assets in this way. Sometimes man may be required simply to accept fate, to bear his cross. Every situation is distinguished by its uniqueness, and there is always only one right answer to the problem posed by the situation at hand.

In considering the human capacity for good and evil and the conditions that bring out indecency in decent people, Frankl writes:

Human kindness can be found in all groups, even those which as a whole it would be easy to condemn.

The boundaries between groups overlapped and we must not try to simplify matters by saying that these men were angels and those were devils.

[…]

From all this we may learn that there are two races of men in this world, but only these two — the “race” of the decent man and the “race” of the indecent man. Both are found everywhere; they penetrate into all groups of society. No group consists entirely of decent or indecent people. In this sense, no group is of “pure race” — and therefore one occasionally found a decent fellow among the camp guards.

Life in a concentration camp tore open the human soul and exposed its depths. Is it surprising that in those depths we again found only human qualities which in their very nature were a mixture of good and evil? The rift dividing good from evil, which goes through all human beings, reaches into the lowest depths and becomes apparent even on the bottom of the abyss which is laid open by the concentration camp.

The second half of the book presents Frankl’s singular style of existential analysis, which he termed “logotherapy” — a method of healing the soul by cultivating the capacity to find a meaningful life:

Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather he must recognize that it is he who is asked.

In a word, each man is questioned by life; and he can only answer to life by answering for his own life; to life he can only respond by being responsible. Thus, logotherapy sees in responsibleness the very essence of human existence.

This emphasis on responsibleness is reflected in the categorical imperative of logotherapy, which is: “Live as if you were living already for the second time and as if you had acted the first time as wrongly as you are about to act now!”

Frankl contributes to history’s richest definitions of love:

Love is the only way to grasp another human being in the innermost core of his personality. No one can become fully aware of the very essence of another human being unless he loves him. By his love he is enabled to see the essential traits and features in the beloved person; and even more, he sees that which is potential in him, which is not yet actualized but yet ought to be actualized. Furthermore, by his love, the loving person enables the beloved person to actualize these potentialities.

By making him aware of what he can be and of what he should become, he makes these potentialities come true.

Frankl wrote the book over the course of nine consecutive days, with the original intention of publishing it anonymously, but upon his friends’ insistent advice, he added his name in the last minute. In the introduction to the 1992 edition, in reflecting upon the millions of copies sold in the half-century since the original publication, Frankl makes a poignant meta-comment about something George Saunders recently echoed, noting:

In the first place I do not at all see in the bestseller status of my book an achievement and accomplishment on my part but rather an expression of the misery of our time: if hundreds of thousands of people reach out for a book whose very title promises to deal with the question of a meaning to life, it must be a question that burns under their fingernails. … At first, however, it had been written with the absolute conviction that, as an anonymous opus, it could never earn its author literary fame.

In the same introduction, he shares a piece of timeless advice on success he often gives his students:

Don’t aim at success — the more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it. For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side-effect of one’s dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one’s surrender to a person other than oneself. Happiness must happen, and the same holds for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it. I want you to listen to what your conscience commands you to do and go on to carry it out to the best of your knowledge. Then you will live to see that in the long run—in the long run, I say!—success will follow you precisely because you had forgotten to think of it.

(Hugh MacLeod famously articulated the same sentiment when he wrote that “The best way to get approval is not to need it.”)

If there ever were a universal reading list of existential essentials, Man’s Search for Meaning would, without a shadow of a doubt, be on it.

Viktor Frankl | Happiness and Meaning |Pursuit of Happiness

Striving to find meaning in one’s life is the primary motivational force in man ~Viktor Frankl ~

Frankl’s BackgroundVictor Emil Frankl (1905 – 1997), Austrian neurologist, psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, devoted his life to studying, understanding and promoting “meaning.”

His famous book, Man’s Search for Meaning, tells the story of how he survived the Holocaust by finding personal meaning in the experience, which gave him the will to live through it. He went on to later establish a new school of existential therapy called logotherapy, based in the premise that man’s underlying motivator in life is a “will to meaning,” even in the most difficult of circumstances.

Frankl pointed to research indicating a strong relationship between “meaninglessness” and criminal behaviors, addictions and depression. Without meaning, people fill the void with hedonistic pleasures, power, materialism, hatred, boredom, or neurotic obsessions and compulsions. Some may also strive for Suprameaning, the ultimate meaning in life, a spiritual kind of meaning that depends solely on a greater power outside of personal or external control.

Some may also strive for Suprameaning, the ultimate meaning in life, a spiritual kind of meaning that depends solely on a greater power outside of personal or external control.

“What man actually needs is not a tensionless state but rather the striving and struggling for some goal worthy of him. What he needs is not the discharge of tension at any cost, but the call of a potential meaning waiting to be fulfilled by him.”

Viktor Frankl was an Austrian neurologist and psychologist who founded what he called the field of “Logotherapy”, which has been dubbed the “Third Viennese School of Psychology” (following Freud and Alder). Logotherapy developed in and through Frankl’s personal experience in the Theresienstadt Nazi concentration camp. The years spent there deeply affected his understanding of reality and the meaning of human life. His most popular book, Man’s Search for Meaning, chronicles his experience in the camp as well as the development of logotherapy. During his time there, he found that those around him who did not lose their sense of purpose and meaning in life were able to survive much longer than those who had lost their way. William James would have considered this life changing event to be a “crisis of meaning.”

During his time there, he found that those around him who did not lose their sense of purpose and meaning in life were able to survive much longer than those who had lost their way. William James would have considered this life changing event to be a “crisis of meaning.”

Logotherapy

In The Will to Meaning, Frankl notes that “logotherapy aims to unlock the will to meaning in life.” More often than not, he found that people would ponder the meaning of life when for Frankl, it is very clear that, “it is life itself that asks questions of man.” Paradoxically, by abandoning the desire to have “freedom from” we take the “freedom to” make the “decision for” one’s unique and singular life task (Frankl 1988, p. 16).

Logotherapy developed in a context of extreme suffering, depression and sadness and so it is not surprising that Frankl focuses on a way out of these things. His experience showed him that life can be meaningful and fulfilling even in spite of the harshest circumstances. On the other hand, he also warns against the pursuit of hedonistic pleasures because of its tendency to distract people from their search for meaning in life.

On the other hand, he also warns against the pursuit of hedonistic pleasures because of its tendency to distract people from their search for meaning in life.

Meaning

Only when the emotions work in terms of values can the individual feel pure joy (Frankl 1986, p. 40).

In the pursuit of meaning, Frankl recommends three different kinds of experience: through deeds, the experience of values through some kind of medium (beauty through art, love through a relationship, etc.) or suffering. While the third is not necessarily in the absence of the first two, within Frankl’s frame of thought, suffering became an option through which to find meaning and experience values in life in the absence of the other two opportunities (Frankl 1992, p. 118).

Though for Frankl, joy could never be an end to itself, it was an important byproduct of finding meaning in life. He points to studies where there is marked difference in life spans between “trained, tasked animals,” i. e., animals with a purpose, than “taskless, jobless animals.” And yet it is not enough simply to have something to do, rather what counts is the “manner in which one does the work” (Frankl 1986, p. 125)

e., animals with a purpose, than “taskless, jobless animals.” And yet it is not enough simply to have something to do, rather what counts is the “manner in which one does the work” (Frankl 1986, p. 125)

Responsibility

Human freedom is not a freedom from but freedom to (Frankl 1988, p. 16).

As mentioned above, Frankl sees our ability to respond to life and to be responsible to life as a major factor in finding meaning and therefore, fulfillment in life. In fact, he viewed responsibility to be the “essence of existence” (Frankl 1992, 114). He believed that humans were not simply the product of heredity and environment and that they had the ability to make decisions and take responsibility for their own lives. This “third element” of decision is what Frankl believed made education so important; he felt that education must be education towards the ability to make decisions, take responsibility and then become free to be the person you decide to be (Frankl 1986, p. xxv).

xxv).

Individuality

Frankl is careful to state that he does not have a one-size-fits all answer to the meaning of life. His respect for human individuality and each person’s unique identity, purpose and passions does not allow him to do otherwise. And so he encourages people to answer life and find one’s own unique meaning in life. When posed the question of how this might be done, he quotes from Goethe: “How can we learn to know ourselves? Never by reflection but by action. Try to do your duty and you will soon find out what you are. But what is your duty? The demands of each day.” In quoting this, he points to the importance attached to the individual doing the work and the manner in which the job is done rather than the job or task itself (Frankl 1986, p. 56).

Techniques

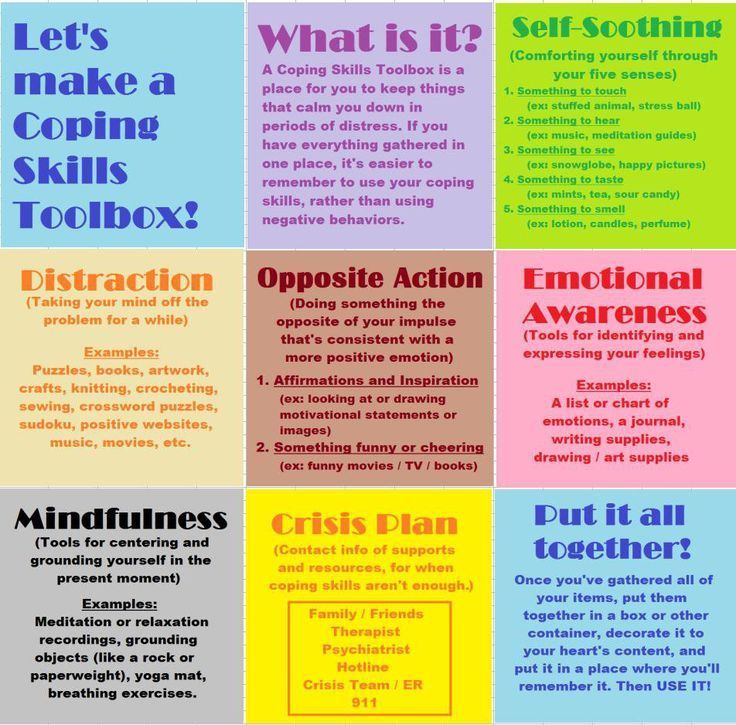

Frankl’s logotherapy utilizes several techniques to enhance the quality of one’s life. First is the concept of paradoxical Intention, wherethe therapist encourages the patient to intend or wish for, even if only for a second, precisely what they fear. This is especially useful for obsessive, compulsive and phobic conditions, as well as cases of underlying anticipatory anxiety.

This is especially useful for obsessive, compulsive and phobic conditions, as well as cases of underlying anticipatory anxiety.

The case of the sweating doctor

A young doctor had major hydrophobia. One day, meeting his chief on the street, as he extended his hand in greeting, he noticed that he was perspiring more than usual. The next time he was in a similar situation he expected to perspire again, and this anticipatory anxiety precipitated excessive sweating. It was a vicious circle … We advised our patient, in the event that his anticipatory anxiety should recur, to resolve deliberately to show the people whom he confronted at the time just how much he could really sweat.A week later he returned to report that whenever he met anyone who triggered his anxiety, he said to himself, “I only sweated out a little before, but now I’m going to pour out at least ten litres!” What was the result of this paradoxical resolution? After suffering from his phobia for four years, he was quickly able, after only one session, to free himself of it for good. (Frankl, 1967)

(Frankl, 1967)

Dereflection

Another technique is that of dereflection, whereby the therapist diverts the patients away from their problems towards something else meaningful in the world. Perhaps the most commonly known use of this is for sexual dysfunction, since the more one thinks about potency during the sexual act, the less likely one is able to achieve it.

The following is a transcript from Frankl’s advice to Anna, 19-year old art student who displays severe symptoms of incipient schizophrenia. She considers herself as being confused and asks for help.

Patient: What is going on within me?

Frankl: Don’t brood over yourself. Don’t inquire into the source of your trouble. Leave this to us doctors. We will steer and pilot you through the crisis. Well, isn’t there a goal beckoning you – say, an artistic assignment?

Patient: But this inner turmoil ….

Frankl: Don’t watch your inner turmoil, but turn your gaze to what is waiting for you.

What counts is not what lurks in the depths, but what waits in the future, waits to be actualized by you….

Patient: But what is the origin of my trouble?

Frankl: Don’t focus on questions like this. Whatever the pathological process underlying your psychological affliction may be, we will cure you. Therefore, don’t be concerned with the strange feelings haunting you. Ignore them until we make you get rid of them. Don’t watch them. Don’t fight them. Imagine, there are about a dozen great things, works which wait to be created by Anna, and there is no one who could achieve and accomplish it but Anna. No one could replace her in this assignment. They will be your creations, and if you don’t create them, they will remain uncreated forever…

Patient: Doctor, I believe in what you say. It is a message which makes me happy.

Discernment of Meaning

Finally, the logotherapist tries to enlarge the patient’s discernment of meaning in at least three ways: creatively, experientially and attitudinally.

a) Meaning through creative values

Frankl writes that “The logotherapist’s role consists in widening and broadening the visual field of the patient so that the whole spectrum of meaning and values becomes conscious and visible to him”. A major source of meaning is through the value of all that we create, achieve and accomplish.

b) Meaning through experiential values

Frankl writes “Let us ask a mountain-climber who has beheld the alpine sunset and is so moved by the splendor of nature that he feels cold shudders running down his spine – let us ask him whether after such an experience his life can ever again seem wholly meaningless” (Frankl,1965).

c) Meaning through attitudinal values

Frankl argued that we always have the freedom to find meaning through meaningful attitudes even in apparently meaningless situations. For example, an elderly, depressed patient who could not overcome the loss of his wife was helped by the following conversation with Frankl:

Frankl asked “What would have happened if you had died first, and your wife would have had to survive you. ”

”

“Oh,” replied the patient, “for her this would have been terrible; how she would have suffered!”

Frankl continued, “You see such a suffering has been spared her; and it is you who have spared her this suffering; but now, you have to pay for it by surviving her and mourning her.” The man said no word, but shook Frankl’s hand and calmly left his office (Frankl, 1992).

ConclusionFrankl’s surprising resilience amidst his experiences of extreme suffering and sadness speaks to how his theories may have helped him and those around him. As the alarming suicide and depression rates among young teenagers and adults in the United States continue, his call to answer life’s call through logotherapy may be a promising resource.

Why the Modern World Needs Viktor Frankl's Logotherapy - The Knife

Back in 1946, in his book Man's Search for Meaning, Viktor Frankl described the feeling of despair so familiar to modern man. An Austrian psychoanalyst and Holocaust survivor said that many of his patients complained of "an overwhelming sense of the utter meaninglessness of life. "

"

The troubles of our age - from all sorts of addictions to belief in pseudo-scientific theories - fell on our heads not by chance. nine0003

As Frankl says, "an abnormal response to an abnormal situation is normal behavior." Our current situation is no less anomalous than in the 1940s: the planet's biosphere is rapidly collapsing, and the next generation of people, according to scientists, may be the last.

That's why it's worth turning to Frankl's book in these troubled times.

A psychotherapist in a concentration camp: an experience of survival

Frankl, before being sent to Auschwitz and then to Dachau, was already an established psychotherapist, representing the so-called third direction of the Viennese school of psychoanalysis. He did not share the views of Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler and rejected both the theory of the first about the "will to pleasure" and the "will to power" - the second. nine0003

"The search for the meaning of life," he wrote, "is the main motivation of human life, and not at all a 'secondary rationalization' (conscious explanation) of instinctive urges. "

"

Frankl asserted the value of literature, art, religion and other cultural phenomena that emphasize meaning and help us find purpose in life. According to the therapeutic method he developed, which he called logotherapy, "the desire to find the meaning of life is the main motivational force of man." nine0003

Frankl believed that a person is able to survive a variety of hardships; but if his life is meaningless, then he is doomed.

See also

Happiness is not in hedonism. Why scientists advise to stop chasing pleasure

Before Auschwitz, Viktor Frankl was the head of the neurology department at the Rothschild Hospital. At Auschwitz, he became "number 119104". The concentration camp was the zero point of meaning. Frankl managed to smuggle the manuscript of the book with him, but he lost it and had to restore it from memory. nine0003

He used his knowledge to provide psychological help to other prisoners and saw this as the purpose of life. The conclusions he came to in the course of these conversations formed the basis of his humanistic psychology.

The conclusions he came to in the course of these conversations formed the basis of his humanistic psychology.

Spiritual freedom in spite of the end of the world: where to look for meaning?

One of the most important was the conclusion that "a prisoner who has lost faith in the future is doomed." Frankl recalled that in the concentration camp, suicide was a common occurrence, and the best chances of survival were not for the strongest or healthiest prisoners, but for those who, despite suffering, were able to find the meaning of existence. Some prisoners managed to "find refuge from the surrounding nightmare in a rich inner life and spiritual freedom." This helped them endure camp life. nine0003

Frankl often had imaginary conversations with his wife Tilly (who, he later learned, had died in another concentration camp) or lectured to imaginary audiences about concentration camp psychology, a topic to which he would dedicate the rest of his life.

In Man's Search for Meaning, he wrote that "man can retain the remnants of spiritual freedom and independence of thought even under conditions of extreme mental and physical stress.

"

" The book reflected the spirit of its time and became a bestseller of the post-war era. It has been translated into more than 20 languages and sold 12 million copies. Many university departments and hospital departments have chosen to put humanistic psychology and logotherapy at the core of their work, even though they often resemble a secular form of rabbinism rather than psychoanalysis. nine0003

Man's Search for Meaning consists of two parts. The first, similar to the works of Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi, is Frankl's memoirs of the Holocaust. The second part is devoted to the theory of logotherapy. Here Frankl argues that a person can find the meaning of life in “the experience of goodness, truth and beauty, nature and culture; or - last but not least - in a meeting with another unique person, with his very uniqueness, in other words - in love ", not in spite of the end of the world, but because of it. nine0003

Criticism: Overoptimism and Victimblaming

The book has been criticized for being superficial and a model of positive new age culture. But such an assessment is not entirely fair. Frankl's "tragic optimism" is inappropriate to be identified with the naive positivity of Pollyanna from Eleanor Porter's novel of the same name. “Since Auschwitz, we have known what man is capable of. And since Hiroshima we have known what is at stake,” he writes.

But such an assessment is not entirely fair. Frankl's "tragic optimism" is inappropriate to be identified with the naive positivity of Pollyanna from Eleanor Porter's novel of the same name. “Since Auschwitz, we have known what man is capable of. And since Hiroshima we have known what is at stake,” he writes.

Some critics accuse Frankl of victim blaming. American scientist Lawrence Langer at 1982 even called Man's Search for Meaning a terrible book.

In his opinion, Frankl reduces the issue of survival to a positive attitude and denigrates the memory of millions of victims. There is some justice in this criticism. However, Frankl does not rebuke those who have lost their meaning. Logotherapy is not an ethical but a strategic approach to experiencing tragedy.

It is a mistake to place the blame for feeling the meaninglessness of life on a suffering person. Prisoners are not responsible for the existence of concentration camps, just as a person born in poverty is not to blame for being poor, and any of us (unless, of course, you are the head of an oil company) are not to blame for the destruction of the ecosystem. nine0003

nine0003

Logotherapy does not mean accepting the status quo: the struggle to improve political, material, social, cultural and economic conditions must never stop. Logotherapy offers something else, a chance to find meaning in a situation where a person is unable to change anything.

In the preface to the 2006 edition, Rabbi Harold Kushner wrote, "Outside forces can take away everything you have except one choice: how to respond to circumstances." nine0008

Logotherapy requires patients to search for personal meaning and to remember that "life asks questions and challenges every day and every hour."

Modernity is Sick: We Need Logotherapy

“I realized the greatest secret that poetry, thought, and faith can share: the salvation of man is through love and in love,” Frankl writes.

In our cruel, limited and cowardly era, it is difficult to find examples of humanity. Our cruelty, narrow-mindedness, and cowardice are a reaction to the approaching end.

nine0008

nine0008 “Each age has its own collective neurosis, and each age needs its own psychotherapy to deal with it,” says Frankl. We are exhausted, anxious, angry and confused by the collapse of personal destinies, networks of relationships and communities, by the destruction of industry, democracy and the ecosystem of our planet. No wonder we suffer from a collective neurosis.

And yet, for some reason, humanistic psychology is not held in high esteem in our time. Instead, we have the sociobiology and neuroscience of today, with the Panglossian optimism of Steven Pinker and the platitudes of Jordan Peterson. nine0003

See also

Psychotherapy for the New Right. How Jordan Peterson Became North America's Leading Political Thinker

In one of the book's most memorable passages, Frankl relates how once, when the prisoners, exhausted to death after a day's work, were resting on the barrack floor, "a comrade ran in and called watch the magnificent sunset. Despite the rather scientific style of presentation, here Frankl gives free rein to his sense of the transcendent:

Despite the rather scientific style of presentation, here Frankl gives free rein to his sense of the transcendent:

“Standing outside, we looked at the clouds blazing in the west and at the sky full of clouds, constantly changing their color and shape, from steel blue to blood red. Our miserable gray dugouts contrasted sharply with all this wealth, and the puddles on the wet ground generously reflected the blazing sky. After a few minutes of moved silence, one prisoner said to another: “What a wonderful world this world could be!””

Logotherapy does not promise more sunsets in life; it is our individual and collective responsibility. nine0003

On the other hand, logotherapy promises delight at the sight of sunset, even if this sunset will be our last; she reminds that one can find meaning, beauty, grace even in hell. And the rest depends on us.

Viktor Frankl on Finding Meaning - T&P

Caring for other people brings meaning to our lives, but it doesn't necessarily make us happy.

At the same time, it is in finding meaning that psychologists see the path to healing from depression. T&P translated an article from The Atlantic about why it's good to have a purpose in life and how the pursuit of happiness can get in the way of happiness itself. nine0108

At the same time, it is in finding meaning that psychologists see the path to healing from depression. T&P translated an article from The Atlantic about why it's good to have a purpose in life and how the pursuit of happiness can get in the way of happiness itself. nine0108 In September 1942, Viktor Frankl, the famous Jewish psychiatrist and neurologist, was arrested and sent to a Nazi concentration camp with his wife and parents. When the camp was liberated three years later, most of his doctor's relatives died, including his pregnant wife. However, he - prisoner number 119104 - survived. A book about his life in the concentration camp "A Man in Search of Meaning", which instantly became a bestseller, Viktor Frankl wrote in 9 days. Reflecting on the fate of the prisoners, the author came to the conclusion that the difference between those who survived and those who did not was in one thing - the desire for Meaning. nine0003

According to Viktor Frankl's observations of concentration camp prisoners, people who managed to find meaning even under the most horrifying circumstances were much more resilient than others. “Everything can be taken away from a person, except for one thing,” Frankl wrote in his famous book, “the last of human freedoms is the ability to independently choose how one relates to certain circumstances.”

“Everything can be taken away from a person, except for one thing,” Frankl wrote in his famous book, “the last of human freedoms is the ability to independently choose how one relates to certain circumstances.”

In Man's Search for Meaning, Frankl describes an example of two prisoners who exhibited suicidal behavior. Like many others in the camp, these men lost hope, stopped seeing the meaning of life. "In both cases, it was important to let them know that something else was waiting for them in life, that they had a future." For one man, the youngest child, who was then living abroad, became such a ray of hope. For another, a scientist, this role was played by a series of books that he had to complete. Frankl wrote: “This uniqueness and exclusivity, which distinguishes each individual and gives meaning to his existence, has as much to do with creativity as it does with human love. When it turns out that it is impossible to replace one person with another, the responsibility of a person for his existence and its continuation is fully manifested. A person who has realized his responsibility to another human being who is passionately waiting for him, or to an unfinished work, will no longer be able to throw his life away. He knows the “why” he needs to live, and will be able to endure almost any “how.” nine0003

A person who has realized his responsibility to another human being who is passionately waiting for him, or to an unfinished work, will no longer be able to throw his life away. He knows the “why” he needs to live, and will be able to endure almost any “how.” nine0003

© Maria Baoli

It seems that today the ideas presented in Frankl's essay - the emphasis on meaning, the significance of suffering and responsibility not only to oneself, but to something greater - are at odds with the principles of modernity, when a person is more interested in personal happiness than the search for meaning. The author observes: “In the eyes of Europeans, an important characteristic of American culture is the imperative: over and over again it is ordered and prescribed to be happy. But happiness cannot be an object of striving, of chasing; it must be the result of something else. You need to have a reason to "be happy". nine0003

According to Gallup, having purpose and meaning in life increases well-being and life satisfaction, improves mental and physical health, improves resilience and self-confidence, and reduces depression. And a person who is solely in search of happiness, it turns out, feels less happy. This is what Frankl points out when he says that "the search for happiness interferes with happiness itself."

And a person who is solely in search of happiness, it turns out, feels less happy. This is what Frankl points out when he says that "the search for happiness interferes with happiness itself."

During a psychological research study, 400 Americans aged 18 to 78 answered the question of whether there is meaning and/or happiness in their lives. Based on the data received from the respondents - the level of stress, their financial capabilities and the presence of children - scientists came to the conclusion that a life endowed with meaning and a happy life overlap to a certain extent, but in fact are very different. A happy life, researchers said, is associated with the ability to take, while a meaningful life is associated with the ability to give. nine0003

“Happiness without meaning characterizes a rather superficial, self-centered, even selfish life in which everything goes well, needs and desires are easily satisfied, and difficulties are avoided”

“Happiness without meaning characterizes a rather superficial, concentrated only on oneself, even a selfish life in which everything goes well, needs and desires are easily satisfied, and difficulties are tried to be avoided, ”the authors of the article write. Psychologists say that happiness is nothing but the satisfaction of desire. An elementary example: you feel happy when you satisfy your hunger. In other words, people become happy when they get what they want. But not only people are capable of such feelings - animals also have needs and desires, and having satisfied them, they equally feel happy. nine0003

Psychologists say that happiness is nothing but the satisfaction of desire. An elementary example: you feel happy when you satisfy your hunger. In other words, people become happy when they get what they want. But not only people are capable of such feelings - animals also have needs and desires, and having satisfied them, they equally feel happy. nine0003

What distinguishes people from animals is not the search for happiness, but the pursuit of meaning - an exclusive feature of man. This was concluded by Roy Baumeister, who co-authored the book Willpower: Rediscovering Man's Greatest Strength with John Tierney. Martin Seligman, another well-known modern day psychologist, has described a meaningful life as “using your strengths and talents for the benefit of something bigger than your ego. For example, finding the meaning of life is associated with such simple actions as buying gifts for other people or taking care of children. People who have a high level of meaningfulness in life often continue to search for meaning, even realizing that this will be to the detriment of their happiness. “We take care of other people, we devote ourselves to them. It brings meaning to our lives, but it does not necessarily make us happy,” Baumeister concludes. nine0003

“We take care of other people, we devote ourselves to them. It brings meaning to our lives, but it does not necessarily make us happy,” Baumeister concludes. nine0003

Returning to the life of a Jewish psychotherapist, it is important to tell about an episode that occurred before his imprisonment in a concentration camp. An episode that defines the difference between the search for meaning and the search for happiness in life. Frankl was a successful psychologist with an international reputation. As a 16-year-old youth, he entered into correspondence with Sigmund Freud and received admiring comments from the great scientist. While attending medical school, he not only founded a center for the prevention of teen suicide, but also began to develop logotherapy, his own technique in clinical psychology, aimed at overcoming depression by finding personal meaning in life. nine0003

© Maria Baoli

By 1941, Viktor Frankl's theories were already in the public domain, he worked as head of the neurology department at the Rothschild Hospital in Vienna, where, at the risk of his own life and career, he makes false diagnoses of mentally ill patients in order to save them from Nazi euthanasia program. In the same year, a famous doctor makes a decision that changes his whole life.

In the same year, a famous doctor makes a decision that changes his whole life.

Having reached certain career heights and realizing the danger of the Nazi regime, Frankl requested a visa to America and received it just at 1941 years old. At that time, the Nazis had already begun to send Jews to concentration camps, taking the elderly first. On the one hand, Franul understood that the moment when they would descend on his parents' house would not have to wait long. He also understood that once this happened, he would have to go into prison with them to help them cope with the horrors of camp life. On the other hand, he had recently become a husband himself, and a fresh American visa tempted him to be safe and calmly continue his successful career. Viktor Frankl decided to set aside personal goals in order to stay with his family and help them, and later other prisoners in the concentration camp. nine0003

The truth that the Jewish doctor learned from the unimaginable suffering he had to go through in prison is still relevant today: “A person’s being is always directed towards something or someone other than himself — be it a meaning that must be realized , or another person to meet.