Stories of children in poverty

What Poverty Means To This Teen : NPR

Heard on All Things Considered

From

By

Jairo Gomez

Seventeen-year-old Jairo Gomez lives in a one-bedroom apartment with eight other family members. His school attendance has suffered because he often has to stay home to babysit his younger siblings. Emily Kwong/WNYC hide caption

toggle caption

Emily Kwong/WNYC

Seventeen-year-old Jairo Gomez lives in a one-bedroom apartment with eight other family members. His school attendance has suffered because he often has to stay home to babysit his younger siblings.

Emily Kwong/WNYC

Jairo Gomez is 17 years old and lives in a tiny apartment in New York City with eight other family members. He has grown up in poverty, like one-third of all kids in the city. With WNYC's program Radio Rookies, Gomez tells the story of how poverty has held him back, and how he's trying to overcome it.

There are nine of us in my family, and we live in a one-bedroom apartment. I share a bunk bed with my sister Judy.

"It's just so stuffed," Judy says. "We don't have enough space for seven kids."

I've seen articles posted on Facebook about how unlikely it is to get out of poverty, how poor people usually stay poor. If I don't get an education, I'll be stuck like my parents.

Jairo Gomez

On the floor we have two mattresses side by side, where three of my other sisters sleep. You have to step toe to heel to get out of the room.

"All we actually need is like a big closet," Judy laughs.

My mom, step-dad and the two youngest ones sleep in the living room.

My mom cleans other people's houses. When she gets home, she keeps on cleaning and takes care of my sisters and brother.

I used to think of my family as middle class, but after my parents split up, my mom had four more kids.

"The truth is I haven't looked it up in the dictionary, the word 'poor,' " says my mom, who speaks only Spanish. "To me, poor is when you don't have enough for soup or a roll of toilet paper."

During my freshman year in high school, I wore ripped jeans, and my sneakers had holes in them. It was kind of embarrassing, but I still didn't think I was poor.

I asked my mom to do the math, and she said right now, my family makes $30,000 a year. According to the federal government, we're $15,000 below the poverty line.

That kind of scares me. I've seen articles posted on Facebook about how unlikely it is to get out of poverty, how poor people usually stay poor. If I don't get an education, I'll be stuck like my parents.

If I don't get an education, I'll be stuck like my parents.

But I haven't always been able to make school my priority. When I was younger, I felt like a robot. All I did was go home and help baby-sit and clean. I never had that freedom before — to be able to hang out and skate with my friends. So in ninth grade, I started cutting every day.

Then, when I was in the 10th grade, for the second time my mom started asking me if I could stay home from school to watch the kids. If I said no, most of the money she would make would go to a baby sitter.

I failed every class that year. That made me finally realize that if I ever wanted to graduate, I needed to be in school. I switched to a transfer school, and my first trimester, I got perfect attendance. I told my mom I wasn't going to take care of the little ones anymore.

"At first I felt annoyed, like, 'How could this kid dare to say that to me?' " my mom says, "when I feel that I try my best to give what's necessary. But then I thought about it, and I thought, 'Maybe I'm not doing my job right. I'm not providing enough.' "

I'm not providing enough.' "

Hearing her say that makes me feel selfish, especially since now my sisters are stuck at home every day.

"Sometimes I wish, like, yeah, you would stay home and, like, help," Judy says.

Judy is 14. She and my older sister, Sarahi, who is in college, are always home baby-sitting, cleaning up after my little sisters and helping feed them.

"I don't want to put this all on Mom," Judy says.

Sometimes I feel like I blame my mom too much for having more kids than she could afford. She's always telling us we're lucky because we'll have each other to go to. But when we still had two of our sisters in diapers, and the pregnancy tests came out positive again and again, Judy, Sarahi and I were like, "I'm not washing the bottles this time."

Because he's often babysitting his younger siblings and trying to keep his grades up, Jairo hardly has any time to do what he loves — skateboarding. Emily Kwong/WNYC hide caption

toggle caption

Emily Kwong/WNYC

Because he's often babysitting his younger siblings and trying to keep his grades up, Jairo hardly has any time to do what he loves — skateboarding.

Emily Kwong/WNYC

I asked my mom why she had so many of us.

"With each pregnancy, I accepted it and let it happen," she says. "And I felt happy, but I never thought, 'This son I'm gonna have, I'm gonna educate and motivate to become a doctor, or this daughter I'm going to have I'm gonna motivate to become a lawyer.'

"The job of the mother is to feed and clothe them, to give them love, when maybe I didn't have time to give them each enough love," she adds.

It gets me mad that my mom works so hard. And there are people out there who are just born into it. They make money like nothing. They don't have to clean houses, wake up early, drain themselves.

I know I should be thinking about going to college when I graduate if I don't want that life, but I'd have to stay at home to afford it. Nine of us in a one-bedroom apartment, no privacy, one bathroom and toys everywhere. I don't know if I can make myself do it.

I don't know if I can make myself do it.

Now I'm working 13-hour shifts, making food deliveries on a bike. Honestly, I'd rather do that and earn money for my own place. We're told, "If you work hard, you'll get results." But for my family, there haven't been any results — just survival.

Produced by Courtney Stein and edited by Kaari Pitkin for All Things Considered.

Faces of Child Poverty – BC Child Poverty Report Card

With 1 in 5 children living in poverty in the province, you can bet that every British Columbian knows a child who is affected. Children are poor because their parents are poor for many different reasons, but what is universal is that the stress and deprivation of living in poverty have lifelong negative implications for children and their families.

In order to put a human face to the statistics of child poverty, five brave mothers and couples have shared their stories of hardship and resilience. These stories point to clear policy solutions.

For low-income grandmother Georgia, securing enough food for the family every week and accessing public transit are some of the family’s key challenges. “When we see security, we hop off.”

Lynda, a mother of four, struggles to make ends meet while raising her family on her disability assistance, which in turn impacts her health and wellbeing as a parent.

Married couple Sabrina and Shawn Moreau understand all too well the benefits of taking their kids beyond the busy streets of the Downtown Eastside: “I can only access what we can walk to,” Sabrina says, “we really don’t travel on transit—we have to walk everywhere.”

Larsen, a former youth in foster care who ran away at age 13 and began a fight against breast cancer in grade 11, is now a single mother raising two children, aged 4 and 15, on disability assistance in a drafty BC Housing unit in Surrey, BC. She knows all too well the challenges of low welfare rates, lack of quality affordable housing, poor quality childcare, and aging housing stock that drives up the energy bills.

Indigenous single mother Suzanne, 31, was also raised in foster care and now raises four children of her own—including 2 twin boys—far below the poverty line. She says racism against Indigenous people is one of the biggest issues facing her family.

Read these stories, then take action by emailing the Premier. Tell her to adopt a comprehensive poverty reduction plan to ensure that stories like these don’t continue to be so common in BC.

Gloria’s Story

Indigenous grandmother Gloria Bonner faces an uphill battle as a grandparent raising two grandsons with special needs.

Gloria has raised her grandsons—from two different daughters—since they were little. Now 7 and 11, she is coping with diagnoses of mild autism and FASD between them, and raising the boys in poverty on her low welfare income.

Long waiting lists for her two sons are a fact of life for Gloria, a fierce advocate for her grandsons.

In order to secure a child care space instead of a spot on a long waiting list, Gloria had to conceal their special needs or risked waiting out the early years on waiting lists.

Grandparents raising grandchildren face complicated bureaucracies – legal, financial and governmental – that are difficult and often expensive to navigate. With two different and complicated legal situations, an ongoing court process, and a challenging relationship with one of her daughters, she needs an enormous amount of support.

Securing enough food for the family every week and accessing public transit are some of the family’s key challenges.

“Both the boys are growing fast, and when you are trying to manage the groceries—we do a lot of rationing. They might want more, but we have to save it to have some for later too,” Gloria says.

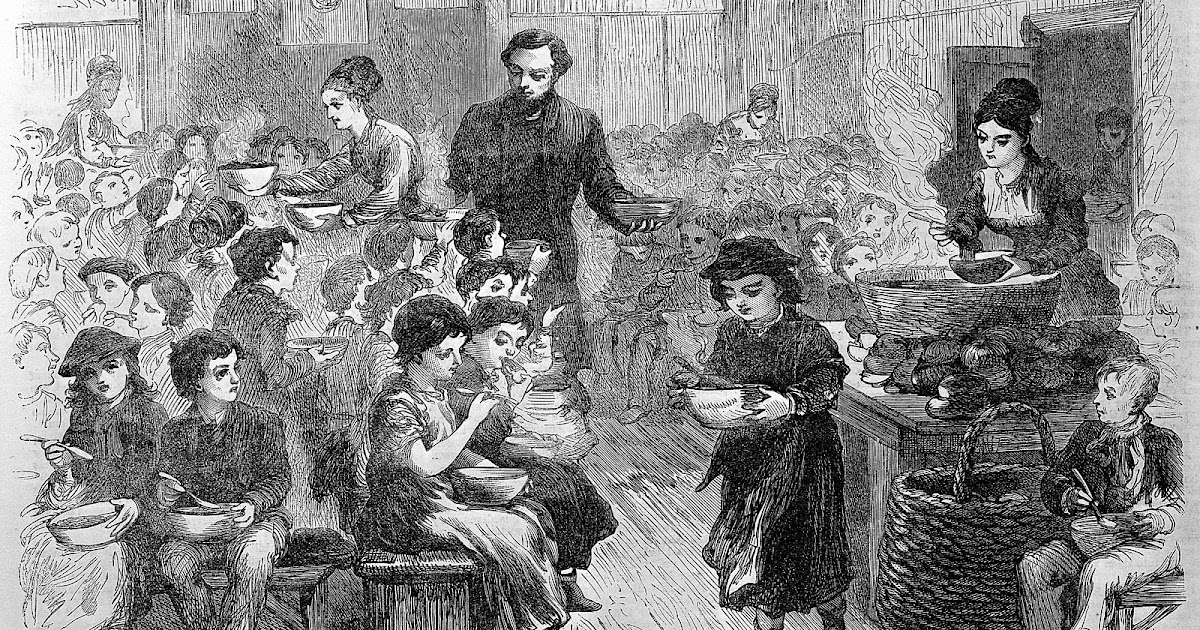

Gloria and her grandsons access free meals at community based charities three nights a week to get by.

Yet when it comes to transit, Vancouver lacks any discounts or supports for low income families or children to get out to community centres with swimming pools and visits to the doctor.

“We get bus passes in a good month, nothing other months.”

Unable to afford transit often, Gloria and her grandsons say they have to “hop it” to get to the library or the park.

“When we see security, we hop off.”

Lynda’s Story

“I have faced low income my whole life,” says Lynda Nickerson, who lives in Nanaimo BC with her husband and four children, ages 3 1/2, 6, 16, and 18.

Raising her family on her disability assistance (PWD), they struggle to make ends meet. Lynda’s health and wellbeing as a parent with mental illness is impacted.

“The impact of low income and the lack of supports for mental health are the big problems,” she says. Lack of quality affordable housing in Nanaimo, childcare struggles and minimal extended drug coverage—lack of a universal Pharmacare plan—are key issues facing her family right now.

“What is left over from our basic needs–that is what is left for medications for me that aren’t covered or approved.

I needed a sleeping aid recently, but when they told me it wasn’t approved…forget it.”

Lynda says she would like to be able to work, but with her depression and anxiety there are many days an eight hour shift would be impossible.

Effective September 1st, 2017, the province raised the earnings exemption for people on disability assistance. A family with two adults where only one person has the Persons with Disabilities designation can now make $14,000 per year.

Lynda would like to go back to school, but the cost of childcare is discouraging. Plus, the Single Parents Employment Program (SPEI), targets only single parents on welfare. Married or common-law couples are left out.

Complicating matters right now is the fact that the family has been renovicted from their current affordable rental at $1350, and must move by the end of the month. Listings in their unit size are topping $1850–a monthly price tag impossible on their income.

“There is deep discrimination against families,” Nickerson says, “an agent said to me they would rather rent to someone with 20 cats then to someone with four kids.

”

Renting lodgings that leak heat and need to be retrofitted, much of their income goes into a $130 a month hydro bill, plus another $130 for gas.

Some welcome relief for the family has arrived in fall 2017. Nanaimo recently made public transit free for up to two children under 14 accompanying an adult who is a pass-holder. The fact that the kids have to travel with a parent is limiting, however, and there is no discount for low income adults.

With the BC Housing waiting list very long and faced with rents they cannot afford, they have no idea where they can afford to live at the end of the month.

Sabrina and Shawn’s Story

Married couple Sabrina and Shawn Moreau are raising their three children in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighbourhood on a fixed welfare income. They speak passionately of the benefits to their family of being able to travel around their city, if only they could. Instead, they struggle to glimpse horizons beyond the busy streets of the Downtown Eastside.

“I can only access what we can walk to,” Sabrina says, “we really don’t travel on transit–we have to walk everywhere.”

She says they would have to take the bus to access the swimming pool or the skating rink, so they rarely do; the walks are too long with their young elementary school aged children and new baby girl. The fresh air and lush green of Stanley Park is frustratingly out of reach.

“If we had access to public transit for the whole family, we’d go to cool events in Stanley Park, or out in Surrey, you hear about these free events for families,” she says.

“It is a scramble to try to get anywhere,” says her husband, Shawn. “There is so much around that is out of reach–community centres, the PNE, Grouse Mountain–but we can’t afford the bus rides after food, paying rent, paying the bills.”

They know how much their kids lose out. If they access transit, though, the kids would have less to eat, and there is already scarcity in the kitchen.

Accessing health care for the whole family is also a major struggle due to their mobility crisis.

They are currently searching for a family clinic within walking distance that can take them all.

They find little room for families, however, as local supports respond to the addictions crisis in their neighbourhood.

Larsen’s Story

A former youth in care who ran away at age 13, B.L. Larsen lived on her own from ages 15 to 18, working at McDonalds every day after school to support herself. In Grade 11, she had breast tumors removed and other serious health issues began to emerge including depression, early osteoporosis, and kidney disease.

Now, Larsen is a single mother raising two children, aged 4 and 15, on disability assistance in a drafty BC Housing unit in Surrey, BC. She knows all too well the challenges of low welfare rates, lack of quality affordable housing, poor quality childcare, and aging housing stock that drives up the energy bills.

Too often, she says, she has had to approach welfare and ‘beg’ for an emergency food voucher to feed her family.

“They [welfare staff] belittle me so terribly…I have nothing to fall back on. When unforeseen things happen, you are stuck. I had to beg and cry for two hours for a $20 food voucher for my kids.”

Larsen says it took 12 years—8 years on her own and four with her first daughter–before she found a unit in BC Housing with rent tied to income.

Yet aging BC Housing stock is impacting her ability to meet the basic needs of her family to stay warm and fed.

“It’s cold, my son is cold, I want to have the heat up but I can’t. You shouldn’t have to turn your heat off just to make sure you can pay your bill.”

Larson is on the BC Hydro equal payment system, paying $135 per month year round. From December to spring, it costs $250 to heat her home. Just when she needs to keep her family warm, she turns the heat off to ensure her bills do not surpass the fixed monthly amount.

“I keep the heat off as much as possible to balance my bill…my suite has windows, skylights and sliding doors, the cold air comes right in.

”

Larsen says the recent $100 raise to welfare only amounts to $10 a year, since the rates had not gone up in a decade. Raising the earnings exemption without a way for her to access a job that works for her unique situation is ‘pointless’.

“My doctors said ‘no’ when I asked them if I could work. I can’t access the SPEI [Single Parents Employment Initiative], it is too much for me.”

Previously, Marshall worked 4-8 hours a week at $10 an hour, which brought in crucial extra income to feed her kids. Then, the company went out of business and she has not been able to find something to replace it ever since.

Even if she could find a way to access the earning exemption, lack of quality, affordable childcare is a huge barrier.

“I can’t afford childcare anyway, so what is the point?”

Suzanne’s Story

Indigenous single mother Suzanne, 31, is raising four children–including 2 twin boys–far below the poverty line.

She says racism against Indigenous people is one of the biggest issues facing her family.

Raised in foster care by a “racist white family” who rejected her Indigenous identity, her foster parents threw her out at age 13. They dropped her off one night at a shelter for youth and drove away. Abandoned to the streets throughout her youth, Suzanne says she didn’t feel helped or supported until she was a single mother and disaster struck.

“They wouldn’t help me until they apprehended my child because of her dad,” she says, “and then I fought for her.”

To secure the support they need to access transit and childcare, single mothers often have to keep a family support file open with the Ministry of Children and Family Development, Suzanne says.

Her oldest daughter has mental health challenges, and other than some counselling, she will not get the real support she needs until she is fully diagnosed. Her daughter has been waiting 1.5 years for a full assessment. The transportation support she needs to take her daughter to counselling every week on the bus she gets through her support file.

“So basically, I have to have social workers in my life who judge me and my kids and my life to get the supports I need.”

The dangers of unlicensed, low quality childcare she knows all too well. While accessing a home-based unlicensed child care setting, Suzanne arrived one day, accompanied by a social worker she was with, to find her toddler daughter and the other children alone in dirty diapers in play pens. An elderly relative was out of sight on the fourth floor. The caregiver had left them unattended to run an errand at the local drugstore.

‘They [social workers] told me I couldn’t leave her there anymore, of course, but then there was zero help for me to find other childcare, so then I had none. Then they come down on you for being a crappy parent when you have no break.”

Pursuing yoga teacher training full time now, Williams feels that the racism she experienced early in life is what needs to change the most.

“People need to start believing we [Indigenous people and parents] can make it in life,” Williams says.

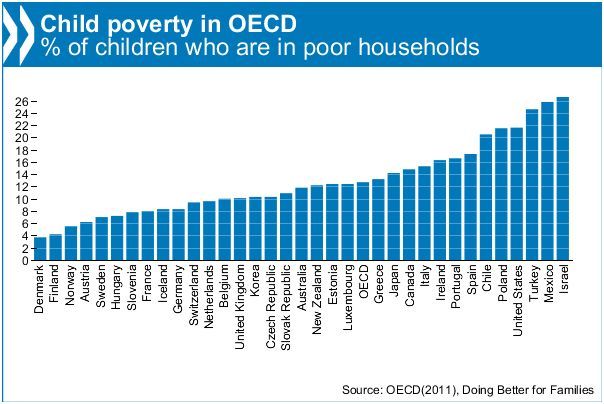

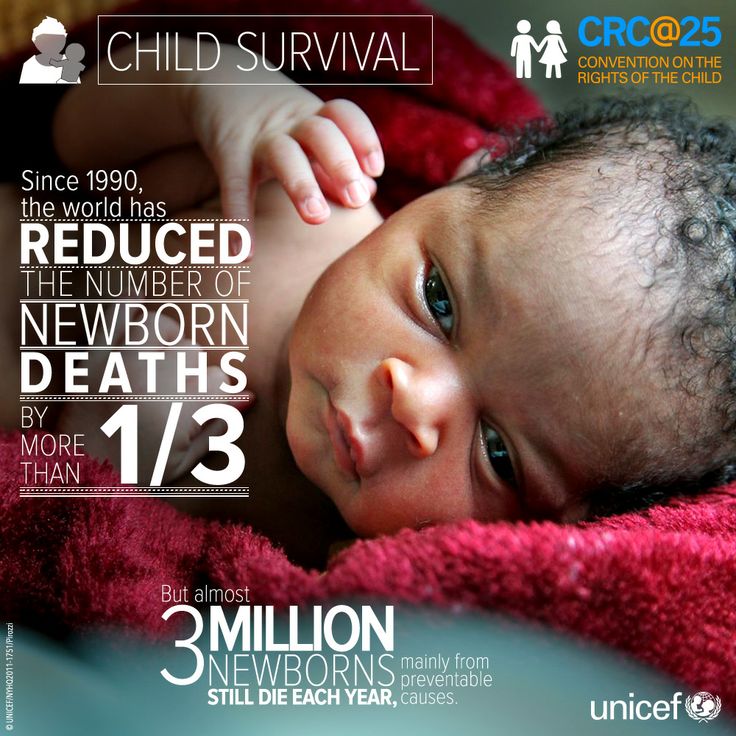

One in six children live in extreme poverty, and this figure is rising during the pandemic

Two-thirds of poor children live in sub-Saharan Africa, where social safety nets are very weak. We are talking about boys and girls from families surviving on $1.90 a day per person or less - this is the amount taken as the basis for determining the international indicator of extreme poverty. The countries of South Asia account for almost a fifth of the poor children.

Photo WFP/A.Etefa

Already before the COVID-19 pandemic, 356 million children worldwide were living in extreme poverty.

The most vulnerable are children in conflict zones, where more than 40 percent of them live in poor families. The world average is 15 percent.

A new study found that between 2013 and 2017, the number of people living in extreme poverty fell by 29 million. However, experts call this achievement weak and uneven. In addition, they fear that even this modest progress will be reversed due to the pandemic.

Struggling to survive

“One in six children living in extreme poverty is one in six children struggling to survive,” said UNICEF's Sanjay Wijesekera. He added that already these figures are shocking. However, they do not reflect the difficult financial situation of families in which they find themselves due to the pandemic.

The UNICEF spokesman called on all countries of the world to urgently develop a plan for the protection of children in order to prevent their rampant levels of poverty "unseen for many, many years."

Children make up about a third of the world's population, but among all the world's poor, they are half. In the world today, the smallest are the hardest hit: in developing countries, almost 20 percent of all children under the age of 5 live in extreme poverty.

“We are all extremely concerned that even before the COVID-19 pandemic, one in six children lived in extreme poverty and that 50 percent of the world's poor were children,” said Carolina Sanchez-Paramo of the World Bank. She emphasized that poverty deprives hundreds of millions of children of the opportunity to fulfill their potential in terms of physical and mental development. These poor, ill-healthy boys and girls have little chance of getting a good education and finding a decent job as an adult. The representative of the World Bank believes that during the recovery period after the pandemic, the authorities of all countries should support the poor.

She emphasized that poverty deprives hundreds of millions of children of the opportunity to fulfill their potential in terms of physical and mental development. These poor, ill-healthy boys and girls have little chance of getting a good education and finding a decent job as an adult. The representative of the World Bank believes that during the recovery period after the pandemic, the authorities of all countries should support the poor.

See also

The pandemic in Europe and Central Asia will increase the number of children living in poverty by 44 percent

After all, the COVID-19 crisis will hit children and women the hardest and could reverse hard-won gains in the fight for gender equality and social justice.

According to the World Bank and UNICEF, most countries responded to economic shocks by expanding social protection programs by providing one-time cash benefits to the poor. Experts have welcomed such moves, but believe they are short-term and inadequate for the magnitude of the shock. The authors of the study suggest expanding the system of regular social support for families with children, as well as investing more in family-oriented strategies.

The authors of the study suggest expanding the system of regular social support for families with children, as well as investing more in family-oriented strategies.

“Poverty is the inability to save one’s children when a mother’s money could do it”

An excerpt from the book “Stories of women who challenged a patriarchal society”

The topic of women’s rights is becoming one of the most relevant on the agenda - and rightly so. We do our best to support women and try to draw attention to the problems they face. And it's great that publishing houses that publish books about equality and the struggle of women for a fair attitude to themselves help us in this, among other things.

Bombora Publishing House publishes Melinda Gates' book The Moment of Takeoff. Stories of women who challenged a patriarchal society."

This is a manifesto for an equal society in which women are valued and recognized in all areas of life. This is an emotional statement that is so necessary in our time, which will give strength and suggest ways to solve problems for each of us, regardless of gender, the publishers say.

This is an emotional statement that is so necessary in our time, which will give strength and suggest ways to solve problems for each of us, regardless of gender, the publishers say.

With their permission, we publish an excerpt from the chapter on empowering mothers.

In 2016, during a trip to Europe, I made a special trip to Sweden to say goodbye to one of my heroes.

Hans Rosling died in 2017, he was a pioneer in international healthcare. Hans became famous for conveying facts to experts that they should have known without his help, but did not. He is also known for his unforgettable TED Talks, which have received over 25 million views and the number continues to grow.

The book Factfulness, which was co-authored with his son and daughter-in-law, brought him popularity, about the fact that the world is actually better than we think about it. In addition, they created the Gapminder Foundation, under the auspices of which original work was done on data and graphics that allowed people to see the world as it is.

For me personally, Hans was a wise mentor whose stories helped me to look at poverty through the eyes of the poor.

I want to tell you the story he shared with me. This story helped me see the impact of conditions of extreme poverty on how women's empowerment helps to eradicate it.

But still, I must warn you that Hans Rosling was less impressed with me than I was with him, at least at the very beginning. In 2007, even before we met, he came to an event where I was going to speak. He later revealed that he was skeptical. He thought: “American billionaires will ruin everything with their money!” (And he was right to be worried. I'll talk more about that later.)

According to him, I won him over by not talking about me sitting in my office in Seattle, reading information and developing various theory, but tried to share what she learned from the midwives, nurses and mothers she met during her trips to Africa and South Asia.

I told true stories of women farmers who walked miles from the fields to the clinic, waited in line in hot weather and eventually found out that the contraceptives they needed were out of stock. I talked about midwives who complained about low pay, low-quality training, and the lack of ambulances.

I deliberately tried to treat every visit with no prejudice. I was driven by curiosity and a desire to learn.

In this, Hans and I were similar, with the difference that he started much earlier than me and with more intensity.

As a young man, Hans and his wife Agnetha, who was also an outstanding medical worker, moved to Mozambique. Hans took up medical practice in a poor region far from the capital. He was one of two doctors who were responsible for 300,000 people. Hans considered all the people in the area to be his patients, even if he had never seen them in his life, and he usually did not see them.

About 15,000 births a year were performed in his county, and more than 3,000 children died.

About ten children died on its territory every day. Hans treated diarrhea, malaria, cholera, pneumonia and took on problematic deliveries. When there are only two doctors for 300,000 people, everyone has to be treated.

This experience shaped him and what he later taught me. Since we met, there has not been a case that, appearing at the same event, we did not find time for each other, even if it was a few minutes in the hallway between sessions. During our meetings, both long and short, he became my teacher. Hans not only told me about extreme poverty, but also helped me look back and understand what I had seen.

“Extreme poverty breeds disease,” he said. “That is the worst thing. It started the Ebola epidemic. Because of her, the radical Islamist organization Boko Haram kidnaps girls.

It took me a long time to figure out what he knew, even though I had the opportunity to learn everything from him.

Nearly 750 million people now live in extreme poverty compared to 1.85 billion in 1990 year. According to policymakers, people living in extreme poverty have to make do with the equivalent of $1.9 a day. But these figures do not reflect the fullness of their desperate situation.

In fact, extreme poverty means that no matter how much you work, you are trapped. You don't see a way out. Your efforts hardly matter. You have been left behind by those who could have helped you. That's what Hans helped me understand.

Throughout our friendship he always said:

- Melinda, you have to be close to people at the very margins of society.

Together we tried to see life through the eyes of the people we hoped to help. I told him about my first trip on behalf of the foundation and how respectfully I left the people I met, because I knew that I could not stand their way of life.

I told him about my first trip on behalf of the foundation and how respectfully I left the people I met, because I knew that I could not stand their way of life.

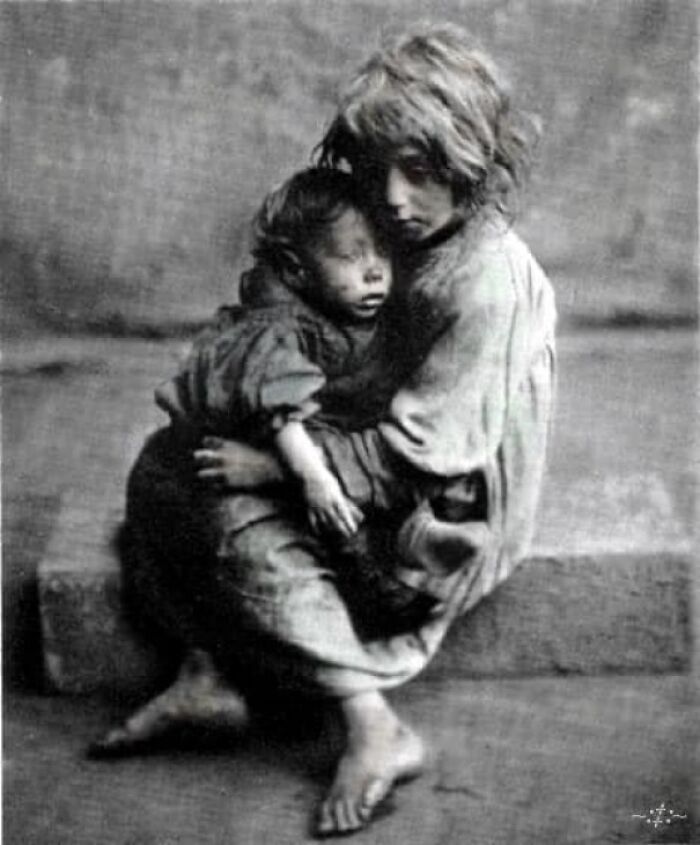

I was visiting the slums of a big city, and it wasn't that small children came up to the car and begged for money that shocked me. I expected to see something like this. I was shocked that small children were left to their own devices. I don't know why I was surprised by this, because it is an obvious consequence of the fact that poor mothers have no choice: in order to survive, they must get a job. But with whom do they leave their offspring?

I saw children walking with babies. I saw a five-year-old running down the street with friends carrying a tiny toddler. I have seen children play near electric wires on the roof, run near sewers on the edge of the street, or near pots of boiling water used by street vendors to cook their food. Danger was part of their daily routine, part of their reality.

The situation could not have been changed by a better choice on the part of the mother, because there was no better choice.

Mothers had to work and did their best to take care of their children in the current situation.

I had so much respect for their ability to keep doing what they have to do to feed their children! I discussed with Hans many times what he saw, and I think this prompted him to tell me what he saw. The story that Hans shared with me a few months before his death, in his opinion, best captures the essence of poverty.

While Hans was a doctor in Mozambique in the early 1980s, a cholera epidemic broke out in his area. Every day he, along with a small group of employees, drove around the area in a health service jeep looking for infected people so as not to wait for them to come to him.

One day at sunset they drove into a remote village. It had about fifty houses, all built from mud blocks. The locals cultivated cassava fields and grew cashews, but they had no donkeys, cows, or horses—no means of transport with which to get their produce to market.

It had about fifty houses, all built from mud blocks. The locals cultivated cassava fields and grew cashews, but they had no donkeys, cows, or horses—no means of transport with which to get their produce to market.

When Hans's team arrived, the crowd looked into the windows of his jeep and began to chant "Doutor Comprido, Doutor Comprido", which means "Doctor High, Doctor High" in Portuguese. That's what they called Hans: not Dr. Rosling or Dr. Hans, but simply Dr. Tall. Most of the villagers had never seen him before, but everyone had heard something about him. Now Doctor High has come to their village.

Getting out of the car, he asked the village chiefs:

— Fala português? (Do you speak Portuguese?)

“Poco, poco,” they replied. (A little.) - Bem vindo, Doutor Comprido. (Welcome, Doctor Tall.)

Then Hans asked:

— How do you know me?

— Oh, you are very well known in this village.

— But I've never been here before.

— No, you have never been here. That's why we're so glad you came. We are very happy.

Others echoed:

- Greetings, greetings, Doctor Tall!

More and more people slowly joined the crowd. Soon about fifty people gathered around, they smiled and looked at Dr. Tall.

“But very few people come to my hospital from this village,” said Hans.

— We very rarely go to the hospital.

— So how do you know me?

— Oh, everyone respects you. You are highly respected.

- Am I respected? But I've never been here before.

— No, you have never been here. And yes, very few people go to your hospital, but one woman came and you treated her. Therefore, you are highly respected.

Therefore, you are highly respected.

- Ah! A resident of this village?

— Yes, one of our women.

— Why did she come?

- Childbirth problem.

— So she came for treatment?

- Yes, and you are so respected because you treated her.

Hans felt some pride and asked:

— Can I see her?

“No,” the people present answered in unison.

- No, you won't be able to see her.

— Why? Where is she?

She is dead.

— Oh, I'm sorry. She died?

- Yes, she died after you treated her.

— Did you say that this woman had problems with childbirth?

Yes.

— Who took her to the hospital?

- Her brothers.

— And she came to the hospital?

- Yes.

— And I treated her?

Yes.

— And then she died?

- Yes, she died on the table on which you treated her.

Hans got nervous. Do they think he's wrong? Are they going to unleash all their grief on him? He looked around to see if the driver was in the car, he wanted to get out of there as soon as possible. He realized that there was no way back, and began to speak slowly and quietly:

— So what was this woman sick with? I don't remember her.

— Oh, you must have remembered her because her baby's hand came out. The midwife tried to pull the child out by the hand, but she failed.

This, as Hans explained to me, is called the presentation of the hand of the fetus. Due to the position of the child's head, it was impossible to extract it.

At that moment, Hans remembered everything. When they arrived, the child was already dead. He had to remove the baby to save the mother's life. The caesarean section was canceled immediately. Hans did not have special equipment for the operation. So he tried to do a fetotomy (remove the dead baby piece by piece). The uterus ruptured and the mother bled to death right on the operating table. Hans couldn't help it.

“Yes, it's very sad,” said Hans. - Very sad. I tried to save her by cutting off the child's hand.

Yes, you cut off his hand.

— Yes, I cut off his hand. I tried to extract the body piece by piece.

- Yes, you tried to extract the body piece by piece. You told the brothers about it.

You told the brothers about it.

— I am very, very sorry that she died.

— Yes, and us too. We are very sorry, she was a good woman, they said.

Hans exchanged pleasantries with them, and when he had nothing more to say, he asked (out of curiosity and courage):

— But why do you respect me then, because I didn't save this woman's life?

— Oh, we knew it was a bad case. We know that most women who lose their hand die. We knew it was a tough one.

— But why do you respect me?

- Because of what you did next.

— And what happened next?

- You ran out of the office into the yard and stopped the vaccination car so that it would not leave. You ran after her and persuaded the driver to return, took the boxes out of the car and arranged for her, a woman from our village, to be wrapped in a white sheet. You gave her a sheet and even a small piece of cloth for the baby's parts. Then you arranged for her body to be placed in that jeep, asked one of your employees to step out to make room for the brothers who could ride with her. So after the tragedy, she returned home on the same day, when the sun was still shining. We had a funeral that same evening, her whole family was present, everyone was here. We did not expect that someone would show such respect for us, poor farmers living in the middle of the forest. You are deeply respected for what you do. Thank you very much. We will never forget you.

You gave her a sheet and even a small piece of cloth for the baby's parts. Then you arranged for her body to be placed in that jeep, asked one of your employees to step out to make room for the brothers who could ride with her. So after the tragedy, she returned home on the same day, when the sun was still shining. We had a funeral that same evening, her whole family was present, everyone was here. We did not expect that someone would show such respect for us, poor farmers living in the middle of the forest. You are deeply respected for what you do. Thank you very much. We will never forget you.

Hans paused in this story and said:

— I did not do all this. It was Mother Rose.

Mama Rosa was a Catholic nun who worked with Hans. She told him:

- Get permission from her family before having a fettotomy. Don't cut the baby until you get their permission. After that, they will ask you for only one thing: get the parts of the child. And then you will say: “Yes, you will get them, and we will give you fabric for the baby.” Here's how to do it. They don't want anyone to take their child's parts for themselves. They want to see all of it.

And then you will say: “Yes, you will get them, and we will give you fabric for the baby.” Here's how to do it. They don't want anyone to take their child's parts for themselves. They want to see all of it.

Hans explained:

— When this woman died, I burst into tears, and Mother Rosa hugged me and said:

— This woman is from a very distant village. We have to take her home. Otherwise, no one from this village will go to the hospital for the next ten years.

— But how do we do it?

“Run outside and stop the vaccination car,” Mother Rosa told me.

And Hans did it.

"Mother Rosa knew what the reality of these people looked like," he said. “I would never have thought to do that myself. It often happens in life that it is men of age who receive all the laurels for the work performed by younger men or women. It's wrong, but that's how it works.

It's wrong, but that's how it works.

This case was the most striking illustration of extreme poverty for Hans.

It was not even about the need to survive on one dollar a day. The main problem is that dying people had to get to the doctor for several days. The doctor was respected not for saving a life, but for returning a dead body to his native village.

If that woman had lived in a prosperous society, and not on the outskirts of the farmers in the remote forest of Mozambique, she would never have lost a child. She wouldn't have lost her life for anything. Here is the essence of poverty, which I was forced to see with my own eyes and feel in the example from Hans's story:

Poverty is the inability to protect one's family. Poverty is the inability to save one's children when the mother's money could do it. And since the strongest of all maternal instincts is to protect their children, poverty robs women of their last strength in the first place.