Ssri for autism

SSRIs and autism | Raising Children Network

What are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)?

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are antidepressant medicines traditionally used to treat depression, anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

SSRIs include sertraline, fluoxetine and citalopram.

Who are SSRIs for?

SSRIs are sometimes prescribed for autistic people who show high levels of anxiety, depression, aggressive behaviour, repetitive behaviour or hyperactive behaviour.

What are SSRIs used for?

SSRIs are used to treat depression, anxiety, OCD and some characteristics of autism, like repetitive or aggressive behaviour.

Where do SSRIs come from?

The first SSRI, fluoxetine, was launched in 1987. SSRIs rapidly became the most widely used treatment for depression. They were also found to be helpful in treating OCD and anxiety.

Since the 1980s, researchers have tested SSRIs for use with autistic people who also have anxiety and OCD.

What is the idea behind using SSRI therapy for autistic people?

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that regulates sleep, mood and emotions. Lack of serotonin has been linked to a range of conditions including anxiety and OCD.

SSRIs can be used to help regulate serotonin. Changing the balance of serotonin seems to help brain cells send and receive chemical messages.

SSRIs are an effective treatment for anxiety, which is common among autistic people.

Also, autistic people have some similar characteristics to people with OCD, including repetitive behaviour, special interests and a preference for routines. SSRIs are effective for treating OCD, so researchers believe that they might also improve similar characteristics in autistic people.

What does SSRI therapy involve?

This therapy involves taking oral medicine on a daily basis. The specific medicine and dosage depends on each person’s needs. Children are started on the lowest possible dose.

A GP, paediatrician or psychiatrist should monitor a child taking SSRIs. The child will need regular appointments with this doctor, especially during the first 4 weeks.

If a doctor prescribes SSRIs for your child, the doctor will probably also recommend a mental health therapy. This might be a therapy like counselling or psychotherapy, which can help your child understand and better manage their thoughts and feelings.

Does SSRI therapy help autistic children?

Research suggests SSRIs don’t change the core characteristics of autism in children. Also, emerging evidence suggests they might cause harm.

It’s possible, however, that SSRIs might help some autistic children with anxiety, but more high-quality research is needed.

It’s also possible that SSRIs might help some autistic adults who also have depression or anxiety.

SSRIs can have some side effects.

Who practises this method?

Your GP or paediatrician or a psychiatrist can prescribe selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and give you information about the potential benefits and risks of using them.

Where can you find a practitioner?

It’s best to speak to your GP, a paediatrician or a psychiatrist about this therapy.

You can find psychiatrists at Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists – Find a psychiatrist.

Parent education, training, support and involvement

If your child is taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), you need to ensure your child takes the medicine. You also need to monitor the effects, including any rare but serious side effects.

Cost considerations

The cost of this therapy varies depending on the brand of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) used and its dose or strength. It also depends on whether the medicine is covered by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and whether you have a concession card – for example, a Health Care Card.

Therapies and supports for autistic children range from behaviour therapies and developmental approaches to medicines and alternative therapies. When you understand the main types of therapies and supports for autistic children, it’ll be easier to work out the approach that will best suit your child.

When you understand the main types of therapies and supports for autistic children, it’ll be easier to work out the approach that will best suit your child.

Commentary on ‘Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for autism spectrum disorders (ASD)’

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

- PMC3160736

Evid Based Child Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 Jul 1.

Published in final edited form as:

Evid Based Child Health. 2011 Jul; 6(4): 1082–1085.

doi: 10.1002/ebch.786

PMCID: PMC3160736

NIHMSID: NIHMS290663

PMID: 21874125

1 and 2

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

This is a commentary on a Cochrane review, published in this issue of EBCH, first published as: Williams K, Wheeler DM, Silove N, Hazell P. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2010 Aug 4 (8):{"type":"entrez-nucleotide","attrs":{"text":"CD004677","term_id":"30321415"}}CD004677. Further information for this Cochrane review is available in this issue of EBCH in the accompanying Summary article.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2010 Aug 4 (8):{"type":"entrez-nucleotide","attrs":{"text":"CD004677","term_id":"30321415"}}CD004677. Further information for this Cochrane review is available in this issue of EBCH in the accompanying Summary article.

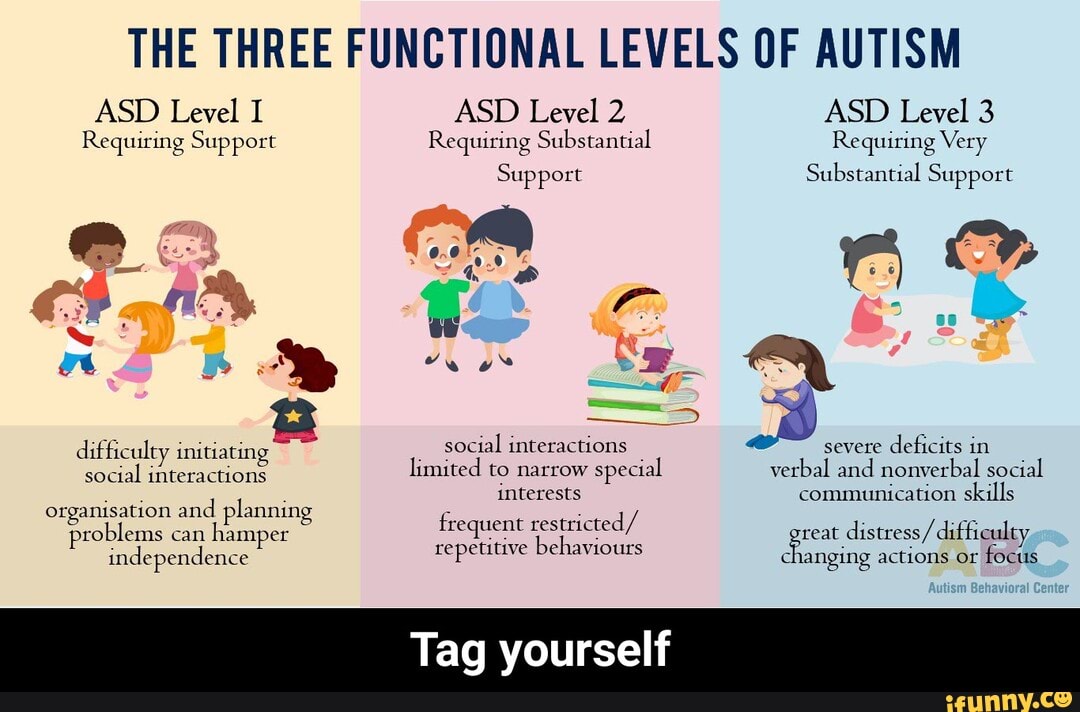

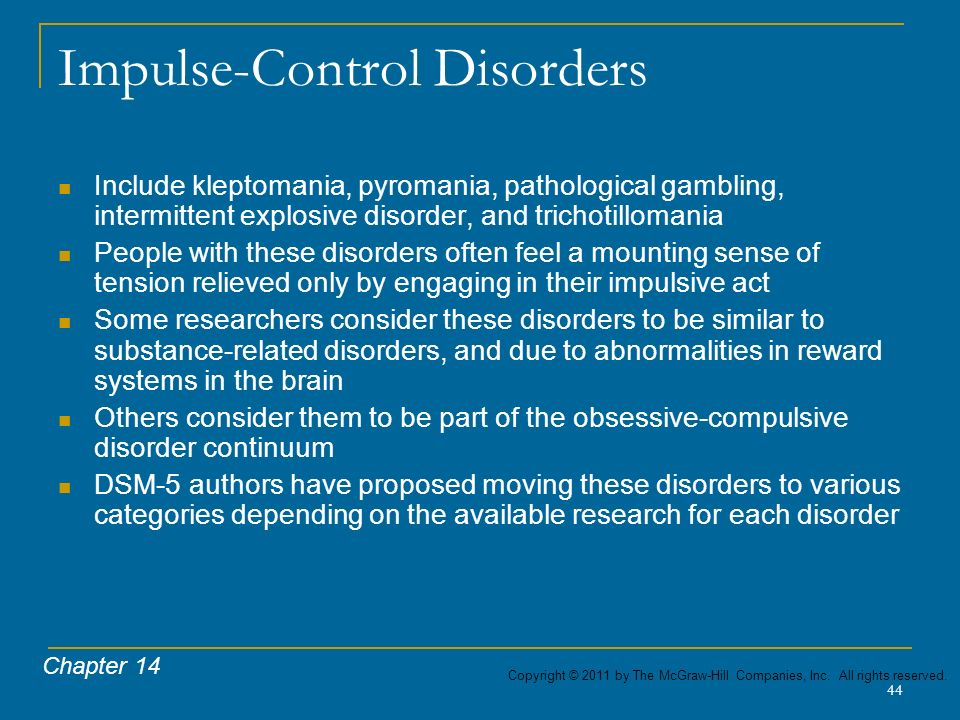

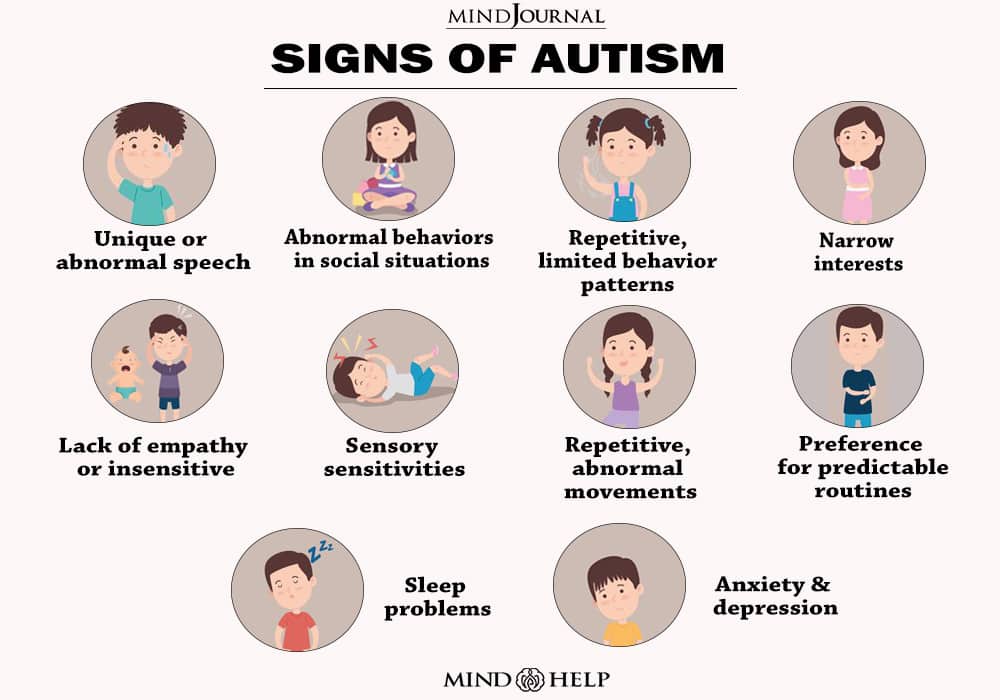

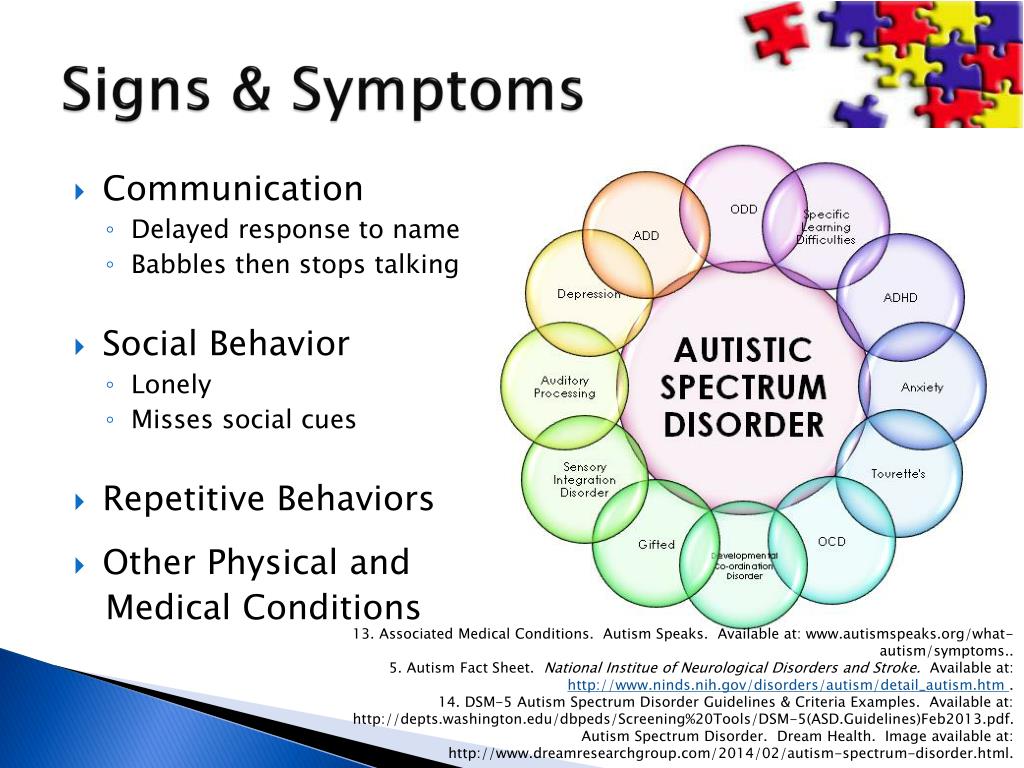

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) are characterized by core symptoms of social deficits, communication abnormalities, and stereotyped/repetitive behaviors. Although a number of educational interventions, behavioral therapies and medications are commonly used in an attempt to reduce problematic symptoms and behaviors in children, adolescents, and adults with ASDs, none of these treatments are curative and many of the commonly used treatments have not been adequately studied to determine their efficacy. In clinical practice, psychotropic medications such as stimulants, neuroleptics, and antidepressants are sometimes used in an attempt to reduce either core ASD symptoms (such as stereotyped behavior) or co-existing symptoms such as inattention, hyperactivity, or agitation. The repetitive and stereotyped behaviors of ASD have some similarity to compulsive behaviors seen in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and this rationale has been used to justify treatment of such behaviors with SSRIs, which have established efficacy in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder (1, 2). In addition to treating the ASD core symptom of repetitive/stereotyped behavior, SSRIs may also be used as a treatment for co-occurring disorders such as depression or anxiety.

The repetitive and stereotyped behaviors of ASD have some similarity to compulsive behaviors seen in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and this rationale has been used to justify treatment of such behaviors with SSRIs, which have established efficacy in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder (1, 2). In addition to treating the ASD core symptom of repetitive/stereotyped behavior, SSRIs may also be used as a treatment for co-occurring disorders such as depression or anxiety.

The prescription of SSRIs for individuals with ASDs is a common practice and may be increasing over time. According to a 1988-2005 longitudinal study of medication use in 286 adolescents and adults with ASD followed over a 4.5 year period, 57% were taking psychotropic medication at the beginning of the study and 64% were taking psychotropic medication at the end of the study (3). There was a statistically significant increase in the proportion taking psychotropic medications over time, and at both time points, the proportion taking psychotropic medication was higher for older individuals. SSRIs were among the most commonly prescribed medications, and the proportion taking this class of medication increased from 24% to 36% over the course of the study. Polypharmacy also increased over the course of the study, such that individuals took an average of 1.0 psychotropic medication at the start of the study and 1.4 medications at the study's end. In addition to this study (which involved samples from Massachusetts and Wisconsin), statewide surveys in North Carolina and Ohio also demonstrated frequent use of SSRIs in the treatment of ASD (4). An increase in the prescribing of psychotropic medications for individuals with ASD over the period of 1993 to 2001 in North Carolina was also noted.

SSRIs were among the most commonly prescribed medications, and the proportion taking this class of medication increased from 24% to 36% over the course of the study. Polypharmacy also increased over the course of the study, such that individuals took an average of 1.0 psychotropic medication at the start of the study and 1.4 medications at the study's end. In addition to this study (which involved samples from Massachusetts and Wisconsin), statewide surveys in North Carolina and Ohio also demonstrated frequent use of SSRIs in the treatment of ASD (4). An increase in the prescribing of psychotropic medications for individuals with ASD over the period of 1993 to 2001 in North Carolina was also noted.

The Cochrane review provides some support for the use of SSRIs in adults with ASD. The authors note that in this group, various SSRIs have shown efficacy in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive behaviors (fluvoxamine), anxiety (fluoxetine) and/or aggression (fluvoxamine) and have led to improvement in clinical global impression (fluoxetine and fluvoxamine). On the other hand, the review authors conclude that there is no evidence to support the use of SSRIs in children and adolescents with ASD, either for treatment of core symptoms or treatment of co-occurring non-core symptoms and behaviors. Also, they point out that SSRIs have a significant risk of causing harm, since side effects were sometimes more common in children treated with SSRIs than in children assigned to placebo. While we agree with many of the reviewers' findings, we would posit that the summary statement that there is no evidence of SSRI efficacy in children with ASD is based on an extremely limited and inadequate number of studies and target symptoms. We are also concerned that the positive outcomes of the Hollander et al. (2005) study may not have received adequate attention (5). Although this was a small study which used complex methods to evaluate multiple outcome measures (some of which showed no treatment effects), the study results provided some evidence of fluoxetine's efficacy in treating repetitive behaviors in ASD, and the low-dose liquid formulation was reasonably well tolerated.

On the other hand, the review authors conclude that there is no evidence to support the use of SSRIs in children and adolescents with ASD, either for treatment of core symptoms or treatment of co-occurring non-core symptoms and behaviors. Also, they point out that SSRIs have a significant risk of causing harm, since side effects were sometimes more common in children treated with SSRIs than in children assigned to placebo. While we agree with many of the reviewers' findings, we would posit that the summary statement that there is no evidence of SSRI efficacy in children with ASD is based on an extremely limited and inadequate number of studies and target symptoms. We are also concerned that the positive outcomes of the Hollander et al. (2005) study may not have received adequate attention (5). Although this was a small study which used complex methods to evaluate multiple outcome measures (some of which showed no treatment effects), the study results provided some evidence of fluoxetine's efficacy in treating repetitive behaviors in ASD, and the low-dose liquid formulation was reasonably well tolerated. We list some specific concerns about existing studies of SSRI treatment for ASDs below:

We list some specific concerns about existing studies of SSRI treatment for ASDs below:

Sample Heterogeneity

It is possible that benefits from SSRI treatment in young people with ASD were undetectable because of heterogeneity of treatment response among individuals with ASDs. As mentioned in the Cochrane review, large trials are needed to investigate any subgroup differences in medication responses. The authors of the review mention pre- vs. post-puberty and low vs. high IQ as relevant comparisons. We also suggest that other variables, such as high vs. low overall ASD core symptom or target symptom severity may be relevant. For example, it is possible that patients with more severe forms of ASD (for example non-verbal individuals with autistic disorder and high levels of agitation) will be less responsive to SSRI treatment and may also be more susceptible to side effects from SSRIs. Higher functioning individuals with diagnoses of Asperger's Disorder or Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) may show better responses to SSRIs. Also, changes in the severity of some target symptoms (such as repetitive behavior) may be undetectable in individuals with very low baseline rates of that target symptom.

Also, changes in the severity of some target symptoms (such as repetitive behavior) may be undetectable in individuals with very low baseline rates of that target symptom.

One possible reason for failure to find improvement in global impression scores could be the presence of behavioral side effects in a subset of study subjects. Even if some of the target behaviors improved, the presence of such side effects could lead to an overall worsening of behavior in some individuals, and this could affect ratings of overall global improvement. A commonly described side effect of SSRIs in children is a behavioral activation or disinhibition syndrome (1, 6, 7). Behavioral side effects in the activation/disinhibition category may be particularly common in children with ASD after initiation of treatment with an SSRI (1). It is unclear to what extent this category of side effects in a subset of study subjects may have obscured the detection of any positive effects of SSRIs in children with ASD, but some of the side effects reported in the reviewed studies are consistent with activation/disinhibition. Detailed measures of behavioral side effects will be important in future studies of SSRIs in ASD. If it is determined that specific SSRIs are less likely to cause behavioral activation side effects, such drugs might be preferred over other SSRIs in the treatment of ASD. As suggested by one of the studies referred to in the review (8), treatment response may also be associated with specific genetic polymorphisms. It is possible that genetic polymorphisms will be found to be associated with target symptom improvement as well as susceptibility to behavioral activation and other side effects from a drug. Pharmacogenetic studies may eventually lead to individualized drug selection based on a patient's genetic profile.

Detailed measures of behavioral side effects will be important in future studies of SSRIs in ASD. If it is determined that specific SSRIs are less likely to cause behavioral activation side effects, such drugs might be preferred over other SSRIs in the treatment of ASD. As suggested by one of the studies referred to in the review (8), treatment response may also be associated with specific genetic polymorphisms. It is possible that genetic polymorphisms will be found to be associated with target symptom improvement as well as susceptibility to behavioral activation and other side effects from a drug. Pharmacogenetic studies may eventually lead to individualized drug selection based on a patient's genetic profile.

Target Symptoms and Assessment Tools

Improved definition of target symptoms and inclusion criteria requiring a threshold level of baseline target symptom severity may be helpful in future studies. If stereotyped/repetitive behavior is the target symptom, it would be reasonable to require that this particular symptom domain lead to behavioral disruption that interferes with school and/or home life. There may be a ceiling effect for individuals who have only mild symptoms at baseline and would be unable to improve to a degree that is clinically and statistically significant. Outcome measures in studies of SSRIs in ASD have included interviews with clinician ratings of global improvement (CGI) and/or questionnaire-based instruments that inquire about repetitive behaviors typical of ASD and/or obsessive-compulsive disorder. In some cases, the CGI may be too broad of a measure, especially if it includes consideration of all problematic symptoms and behaviors rather than specific target symptoms. For example, it seems unlikely that a CGI that includes consideration of overall ASD severity would be significantly impacted by a change in the frequency or severity of a child's repetitive behaviors. Instead, more specific questions measuring the frequency of repetitive behaviors, severity of distress during transitions or forced interruption of repetitive behavior, disruptive behavior in response to changes in usual routines, and degree to which teachers/parents/others have to modify the child's environment or adjust their own plans to accommodate the repetitive/stereotyped behaviors may be useful.

There may be a ceiling effect for individuals who have only mild symptoms at baseline and would be unable to improve to a degree that is clinically and statistically significant. Outcome measures in studies of SSRIs in ASD have included interviews with clinician ratings of global improvement (CGI) and/or questionnaire-based instruments that inquire about repetitive behaviors typical of ASD and/or obsessive-compulsive disorder. In some cases, the CGI may be too broad of a measure, especially if it includes consideration of all problematic symptoms and behaviors rather than specific target symptoms. For example, it seems unlikely that a CGI that includes consideration of overall ASD severity would be significantly impacted by a change in the frequency or severity of a child's repetitive behaviors. Instead, more specific questions measuring the frequency of repetitive behaviors, severity of distress during transitions or forced interruption of repetitive behavior, disruptive behavior in response to changes in usual routines, and degree to which teachers/parents/others have to modify the child's environment or adjust their own plans to accommodate the repetitive/stereotyped behaviors may be useful. Observational assessments that are able to quantify frequency of stereotyped/repetitive motor behaviors may also be helpful. Investigators may also want to obtain specific examples of repetitive behaviors from the caregivers of individual study subjects and ask caregivers to rate the frequency, severity, and impairment from these specific target symptoms throughout the course of the medication trial. Ratings of the impact of such behaviors on family life could also be used. Considering the studies discussed in the Cochrane Review, one instrument that comes close to measuring individualized target behaviors in this manner is the CY-BOCS-PDD, which includes questions regarding specific OCD-like compulsive behaviors and repetitive behaviors typical of ASD, followed by scales that rate the severity of time spent, interference, distress, resistance, and control with reference to the behaviors reported to be present (9). However, even this instrument may not be sensitive enough to detect some types of clinically significant behavioral improvements.

Observational assessments that are able to quantify frequency of stereotyped/repetitive motor behaviors may also be helpful. Investigators may also want to obtain specific examples of repetitive behaviors from the caregivers of individual study subjects and ask caregivers to rate the frequency, severity, and impairment from these specific target symptoms throughout the course of the medication trial. Ratings of the impact of such behaviors on family life could also be used. Considering the studies discussed in the Cochrane Review, one instrument that comes close to measuring individualized target behaviors in this manner is the CY-BOCS-PDD, which includes questions regarding specific OCD-like compulsive behaviors and repetitive behaviors typical of ASD, followed by scales that rate the severity of time spent, interference, distress, resistance, and control with reference to the behaviors reported to be present (9). However, even this instrument may not be sensitive enough to detect some types of clinically significant behavioral improvements. While tools such as the CY-BOCS-PDD are available to measure repetitive behaviors, the field has few options for adequately measuring target symptoms of anxiety or depression (especially in individuals with more limited language skills). The authors of the Cochrane review suggest that, on a case-by-case basis, it is reasonable to use SSRIs in children with ASD when targeting symptoms of co-occurring disorders for which the drugs are approved. However, it is not clear whether SSRIs have the same efficacy for such disorders when used in individuals with ASD. In future studies, it would be helpful to include anxiety and depression as target symptoms. Since symptoms of these disorders may present differently in ASD than non-ASD subjects, it may also be important to develop improved measures of anxiety and depression designed specifically for use in individuals with ASD.

While tools such as the CY-BOCS-PDD are available to measure repetitive behaviors, the field has few options for adequately measuring target symptoms of anxiety or depression (especially in individuals with more limited language skills). The authors of the Cochrane review suggest that, on a case-by-case basis, it is reasonable to use SSRIs in children with ASD when targeting symptoms of co-occurring disorders for which the drugs are approved. However, it is not clear whether SSRIs have the same efficacy for such disorders when used in individuals with ASD. In future studies, it would be helpful to include anxiety and depression as target symptoms. Since symptoms of these disorders may present differently in ASD than non-ASD subjects, it may also be important to develop improved measures of anxiety and depression designed specifically for use in individuals with ASD.

Other SSRIs

The authors of the review note that no adequate randomized controlled trials of paroxetine, sertraline, or escitalopram have been conducted.![]() It is possible that these agents may be more effective or associated with fewer side effects than the SSRIs used in existing randomized controlled trials. Sertraline may be particularly appropriate for study since it already has an FDA indication for pediatric OCD. One of us (AR) suspects based on clinical experience that paroxetine is somewhat less likely than other SSRIs to cause a disinhibition syndrome. This hypothesis is based on observations of multiple young clinic patients with ASD who developed behavioral disinhibition on a first and/or second SSRI trial but subsequently benefitted from low-dose paroxetine without the occurrence of disinhibition side effects that were observed with previous SSRIs. Although the half-life of paroxetine is relatively short and this characteristic may increase the likelihood of discontinuation effects when doses are missed or prior to the next scheduled dose, the short half life may be advantageous if the drug must be discontinued due to behavioral disinhibition (behavioral side effects should wear off faster after discontinuation or reduction in dose if a drug with a short half life is used).

It is possible that these agents may be more effective or associated with fewer side effects than the SSRIs used in existing randomized controlled trials. Sertraline may be particularly appropriate for study since it already has an FDA indication for pediatric OCD. One of us (AR) suspects based on clinical experience that paroxetine is somewhat less likely than other SSRIs to cause a disinhibition syndrome. This hypothesis is based on observations of multiple young clinic patients with ASD who developed behavioral disinhibition on a first and/or second SSRI trial but subsequently benefitted from low-dose paroxetine without the occurrence of disinhibition side effects that were observed with previous SSRIs. Although the half-life of paroxetine is relatively short and this characteristic may increase the likelihood of discontinuation effects when doses are missed or prior to the next scheduled dose, the short half life may be advantageous if the drug must be discontinued due to behavioral disinhibition (behavioral side effects should wear off faster after discontinuation or reduction in dose if a drug with a short half life is used). Disadvantages of paroxetine include the lack of currently approved pediatric indications and its interference with the metabolism of multiple other drugs. However, if paroxetine turned out to be efficacious and better tolerated than other SSRIs, the risk/benefit ratio of its use in ASD might be favorable.

Disadvantages of paroxetine include the lack of currently approved pediatric indications and its interference with the metabolism of multiple other drugs. However, if paroxetine turned out to be efficacious and better tolerated than other SSRIs, the risk/benefit ratio of its use in ASD might be favorable.

Combination Therapy

Medication trials focusing on combination therapy are greatly needed. Although polypharmacy in the treatment of individuals with ASD seems to be an increasingly common occurrence (3), clinical trials using combination treatments are not available to inform us regarding the safety and efficacy of prescribing multiple psychotropic medications at once. Randomized controlled trials comparing single agents to placebo and a combination of two drugs would be helpful. For example, a study comparing treatment responses for individuals treated with an SSRI alone vs. SSRI plus a stimulant (or SSRI plus a neuroleptic) vs. placebo could be done. Appropriate target symptoms for each drug as well as measures of overall functioning would be appropriate outcome measures.

The Cochrane review clearly provides important guidance for current clinical practice. There is a reasonable amount of support for the use of SSRIs to treat repetitive behaviors (and perhaps other core symptoms) in adults with ASD. Since review of existing studies does not support the efficacy of SSRIs in children and adolescents with ASDs, any use of these drugs within this younger age range should be done cautiously. We recognize that few psychotropic medications are specifically approved for use in children with ASD, and providers may choose to treat such patients in an off-label manner based on mechanistic hypotheses about possible beneficial drug effects or the presence of symptoms similar to those of other disorders for which SSRIs are approved. If clinicians offer to prescribe SSRIs to children with ASD, it is important that they inform parents about the lack of evidence of their efficacy in RCTs, discuss the potential risks (including behavioral side effects), and discuss alternative pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. When treating individuals in an off-label manner, it is particularly important to define clear target symptoms and assess whether such symptoms have improved with addition of the drug, keeping in mind the possibility of placebo effects and adverse drug reactions. If a drug does not seem to produce significant benefit or if side effects outweigh any beneficial effects, it is important to discontinue the ineffective drug rather than continuing that drug while adding on new medications. Given the evidence of adverse behavioral side effects from SSRIs in young patients with ASD, caution should be used with initial dosing and side effects must be closely monitored. The use of low initial doses and slow upward titration may help to reduce side effects. As a general rule, one of us has previously suggested starting with a half tablet of the smallest available tablet size and increasing by a half tablet per week to reach a moderate target dose (1). For example, in the case of sertraline, the recommended starting dose for treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children age 6-12 years is 25mg (smallest tablet size), so starting at half that dose (12.

When treating individuals in an off-label manner, it is particularly important to define clear target symptoms and assess whether such symptoms have improved with addition of the drug, keeping in mind the possibility of placebo effects and adverse drug reactions. If a drug does not seem to produce significant benefit or if side effects outweigh any beneficial effects, it is important to discontinue the ineffective drug rather than continuing that drug while adding on new medications. Given the evidence of adverse behavioral side effects from SSRIs in young patients with ASD, caution should be used with initial dosing and side effects must be closely monitored. The use of low initial doses and slow upward titration may help to reduce side effects. As a general rule, one of us has previously suggested starting with a half tablet of the smallest available tablet size and increasing by a half tablet per week to reach a moderate target dose (1). For example, in the case of sertraline, the recommended starting dose for treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children age 6-12 years is 25mg (smallest tablet size), so starting at half that dose (12. 5 mg) would be reasonable when treating a child in this age range who may be at some increased risk of behavioral side effects due to an ASD diagnosis. The dose could then be increased by 12.5mg per week (if well tolerated) to an initial target dose of 25-50 mg and held at 25-50mg for 4-6 weeks before any further increase is considered. Liquid formulations can allow for even smaller starting doses in children at the lower end of this age range or in those who have shown sensitivity to side effects of other medications. For adolescents and adults with ASD, it may also be advisable to start a bit below the FDA-recommended starting dose for the drug and to use a relatively slow upward titration. If side effects occur during upward titration, these may decrease with a dose reduction. If disinhibition is severe and present even at low doses, or if the medication does not result in symptom improvement, the SSRI should be tapered off and discontinued. Finally, we agree with the Cochrane review's call for additional study of SSRIs in ASD, including examination of possible sub-group variables, larger trials, examination of other target symptoms in children with ASD (e.

5 mg) would be reasonable when treating a child in this age range who may be at some increased risk of behavioral side effects due to an ASD diagnosis. The dose could then be increased by 12.5mg per week (if well tolerated) to an initial target dose of 25-50 mg and held at 25-50mg for 4-6 weeks before any further increase is considered. Liquid formulations can allow for even smaller starting doses in children at the lower end of this age range or in those who have shown sensitivity to side effects of other medications. For adolescents and adults with ASD, it may also be advisable to start a bit below the FDA-recommended starting dose for the drug and to use a relatively slow upward titration. If side effects occur during upward titration, these may decrease with a dose reduction. If disinhibition is severe and present even at low doses, or if the medication does not result in symptom improvement, the SSRI should be tapered off and discontinued. Finally, we agree with the Cochrane review's call for additional study of SSRIs in ASD, including examination of possible sub-group variables, larger trials, examination of other target symptoms in children with ASD (e. g., anxiety, depression) and RCTs with three yet unstudied SSRIs.

g., anxiety, depression) and RCTs with three yet unstudied SSRIs.

Drs. Reiersen and Handen both receive research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was supported by career development award number K08-MH-080287 (PI-AMR) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Declarations of Interest: Dr. Handen has worked as a consultant for Forest Laboratories, and has received research funding from Eli Lilly, Curemark, Forest Laboratories, and Autism Speaks. Dr. Reiersen has no interests to disclose.

1. Reiersen AM, Todd RD. Co-occurrence of ADHD and autism spectrum disorders: phenomenology and treatment. Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 2008 Apr;8(4):657–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Todd RD. Fluoxetine in autism. The American journal of psychiatry. 1991 Aug;148(8):1089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1991 Aug;148(8):1089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Esbensen AJ, Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Aman MG. A longitudinal investigation of psychotropic and non-psychotropic medication use among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2009 Sep;39(9):1339–1349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Aman MG, Lam KS, Van Bourgondien ME. Medication patterns in patients with autism: temporal, regional, and demographic influences. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology. 2005 Feb;15(1):116–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Hollander E, Phillips A, Chaplin W, Zagursky K, Novotny S, Wasserman S, et al. A placebo controlled crossover trial of liquid fluoxetine on repetitive behaviors in childhood and adolescent autism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005 Mar;30(3):582–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Reinblatt SP, DosReis S, Walkup JT, Riddle MA. Activation adverse events induced by the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluvoxamine in children and adolescents. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology. 2009 Apr;19(2):119–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology. 2009 Apr;19(2):119–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Reid JM, Storch EA, Murphy TK, Bodzin D, Mutch PJ, Lehmkuhl H, et al. Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Treatment-Emergent Activation and Suicidality Assessment Profile. Child & youth care forum. 2010 Feb 4;39(2):113–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Sugie Y, Sugie H, Fukuda T, Ito M, Sasada Y, Nakabayashi M, et al. Clinical efficacy of fluvoxamine and functional polymorphism in a serotonin transporter gene on childhood autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2005 Jun;35(3):377–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Scahill L, McDougle CJ, Williams SK, Dimitropoulos A, Aman MG, McCracken JT, et al. Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale modified for pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006 Sep;45(9):1114–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Why do viruses affect autism and how to deal with them? — Dr.

Levit Center

Levit Center 📍A retrovirus is a type of virus that inserts a copy of its gene into the DNA of the host cell it has invaded, thereby altering the gene of the host cell

.

📍 Function - from the Latin word - performance. .

.

📍 Pathology - from the Greek word - Patos - suffering, illness; .

.

📍 Logos is a teaching.

⠀.⠀⠀ ⠀

📍Tone - from the Latin word tension

. nine0003 📍Hyper - from the Greek word⠀ over, exceeding the norm. ⠀⠀

.⠀⠀

📍 Hypertonicity - increased tension

.

📍Muscle hypertonicity - increased muscle tension.

.

📍 Meningoencephalitis (inflammation of the cerebral membrane

.

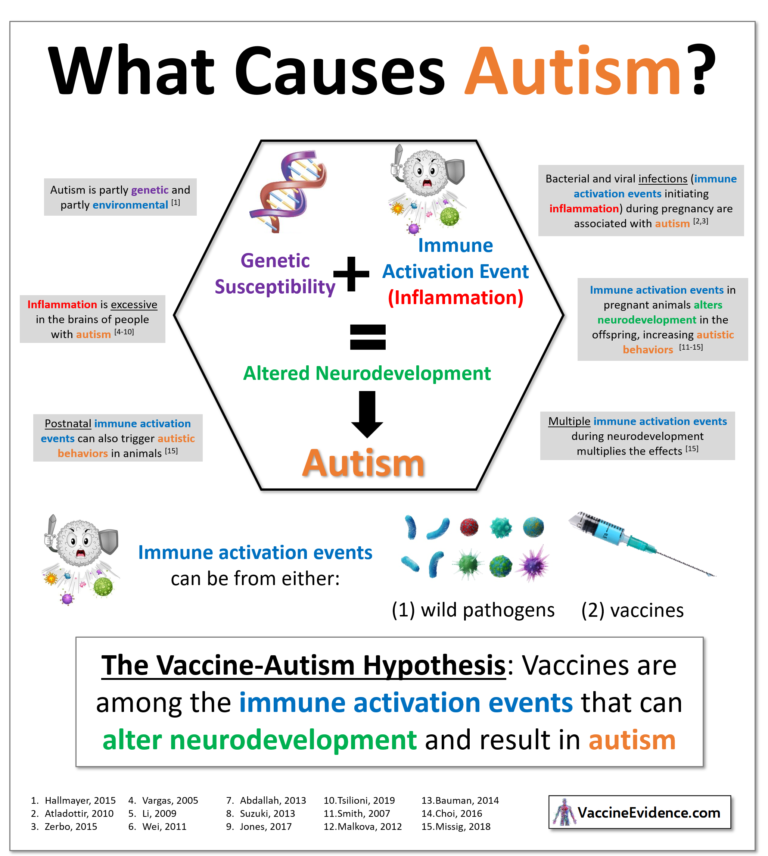

📍 Vaccination-Autism trigger

.

📍. Thrigiger-something that causes or can provoke

.

📍mmunity-recognition and removal of foreign substances and cells.

.

📍Autimm diseases - (auto in Greek means self), (immune - pertaining to the immune system. .

.

📍Vacuum - traction - (traction in Latin means stretching) - pulling the fetus by the head using vacuum.

.

📍To assist in Latin means to help.

.

📍Post - (post means after)

.

📍Post-vaccination complications - complications after vaccinations. . .

.

📍Genetics - (from the Greek word geneticist - damaging, originating from someone; a section of biology that studies genes, genetic variations and heredity in organisms).

.

📍 (Synapse - from the Greek word - connection, connection; this is the place of contact between two neurons, serves to transmit a nerve impulse between two cells; the impulse is transmitted chemically or electrically from one cell to another)

Immunity - recognition and removal of foreign substances and cells (including pathogenic bacteria and viruses)

Herpes and autism

It is generally accepted that autism is genetic in nature. Infectious and toxic causes of autism do not contradict genetic theory. Viruses such as herpes can provoke the development of autistic disorders if the child has such a predisposition.

Infection with the Herpes virus or a pathogen capable of inducing an abnormal immune response of the body. The virus can lead to the development of autism in children and other autoimmune diseases. nine0039

Here are some infectious diseases that have been found in most autistic children. They can be very dangerous for the developing brain of the baby, but at the same time they are quite often asymptomatic: herpesvirus 3)

Mononucleosis - Epstein-Barr virus (HerpesVirus 4)

Cytomegalovirus (HCMV - HerpesVirus 5)

Roseola (HerpesVirus 6, 7)

If the baby has a weak immune system, the virus may be forced out of his body late or not completely. But at the same time, the child will not look sick.

Due to initially reduced immunity in children, the risk of the virus affecting the brain and nervous system increases. This threatens with an autoimmune reaction. That is, the child's body begins to fight with itself and affects the cells of its own body, which can be the cause of autism and developmental delay. nine0039

nine0039

“If before or after birth (at particularly “dangerous moments”) the CNS (central nervous system) of a child becomes infected, this can lead to autism… For example, this applies to retroviruses.

A retrovirus is a type of virus that inserts a copy of its gene into the DNA of the host (patient) cell it has invaded, thereby changing the gene of the host (patient) cell .

They are fully integrated into the genetic material of the child's cells. Herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus are also considered to be one of the causes of autism. They can doze for a long time, and wake up from time to time, causing secret damage to the health of the child, his central nervous system. [nineteen0039

Where does the virus come from?

The baby may have an intrauterine infection due to a viral infection. A fetus infected with cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes, behaves differently than a healthy one. If a healthy child actively moves during childbirth, helps the mother, then a sick baby cannot do this, he is lethargic, sucks his breast very weakly.

If a healthy child actively moves during childbirth, helps the mother, then a sick baby cannot do this, he is lethargic, sucks his breast very weakly.

A baby can also become infected with viruses from the mother - through mother's milk, saliva, or pick it up in a nursery. This happens with the Epstein-Barr virus, (herpes virus type 4) 90% of people are carriers and are almost asymptomatic at an early age.

The herpes virus type 1 and 2 is able to penetrate into brain areas through neurons. In this case, there may not be signs of obvious inflammation of the meninges of the meninges; check with the doctor for the membranes or membranes, in the literature in different ways (encephalitis, meningitis, etc.).

Areas of the brain that are not directly involved in the control of the body - walking, digestion, breathing - are the first to be hit. nine0039

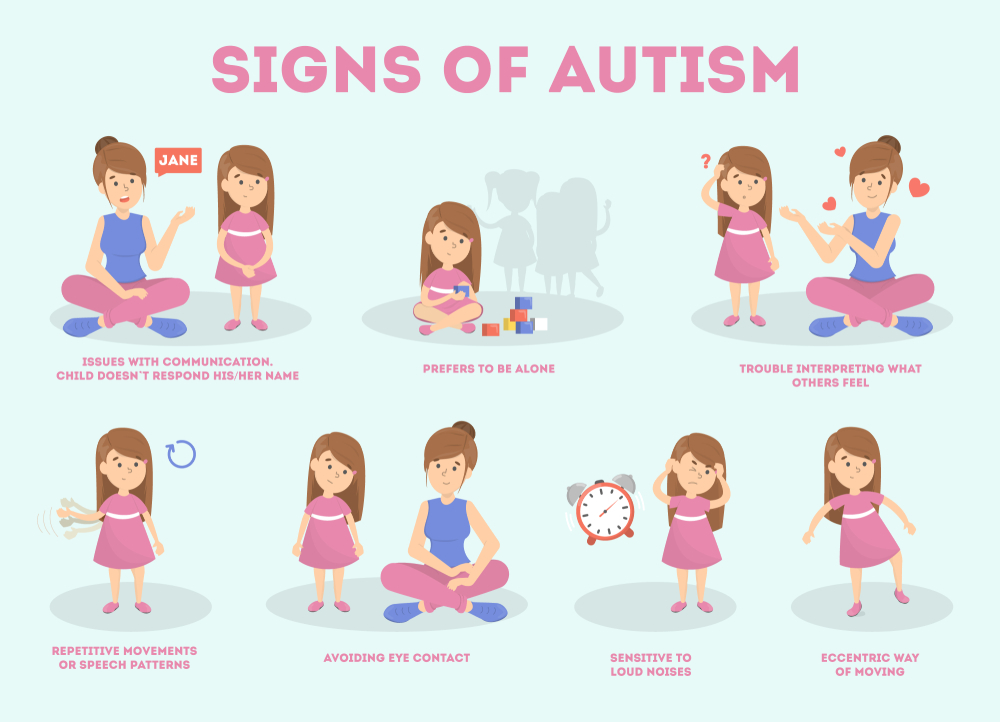

The weakest areas are responsible for communication and our emotional well-being .

Thus, the cerebellar amygdala regulates our emotions when we worry, feel sad, feel and recognize familiar faces. And it is she who is responsible for eye-to-eye contact, intonation of speech and manner of communication. [2]

And it is she who is responsible for eye-to-eye contact, intonation of speech and manner of communication. [2]

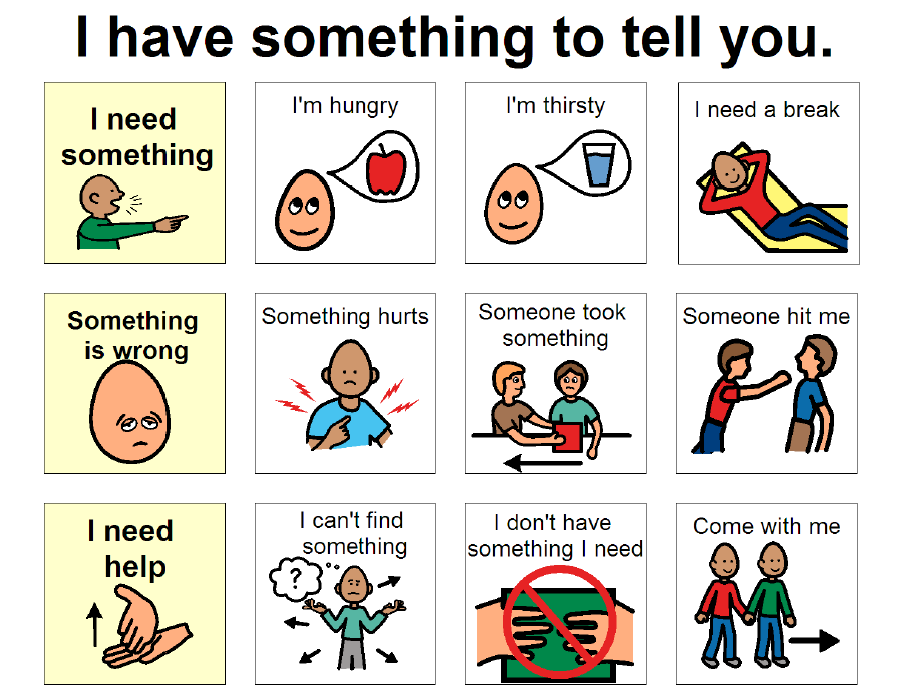

But communication disorders - isolation, lack of eye contact and emotions - are the main symptom of autism in children. Read more about signs in the article. nine0045

Fungi and immunity

Scientists have shown that the properties of the cellular mechanism are very important in protecting the body from viruses, infections and diseases caused by the fungal bacterium of the genus Candida (Candida albicans). It is scientifically substantiated that with a weakened immune system (immune response from Th 1 to Th 2), the likelihood of developing thrush in children increases dramatically. [3] And just in autistic children, there is a shift in the immune response towards Th 2. That is, such children are more prone to thrush of the mucous membranes. nine0039

With candidiasis (thrush), a special diet of BGBK (without dairy and flour) and sugar is very helpful. Fungi do not receive a nutrient medium and die. Many mothers of children with autism note a pronounced effect of the diet in a fairly short time.

Fungi do not receive a nutrient medium and die. Many mothers of children with autism note a pronounced effect of the diet in a fairly short time.

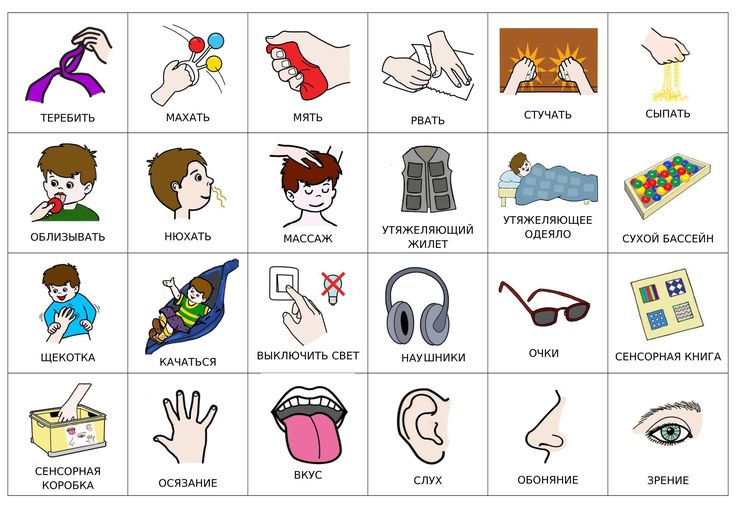

Some children lose stims — ( stereotyped repetitive movement) self-damaging behavior and scratching. There is a theory that children are constantly pulling themselves and scratching the skin due to itching from thrush. You can read about the BGBK diet and recipes here. nine0003 Theoretically, all these factors can cause an epidemic of autism among children. But in practice? We give an example from the book of Dr. McCandles, a doctor with 30 years of experience, the grandmother of a child with autism.

Case history of a girl with autism spectrum disorder.

"Case Report - Susie"

"In 1998 I was asked to look after a high-functioning 16-year-old autistic girl whose mother thought her daughter might be suffering from some kind of 'brain virus'. I told my mother that I had never treated anyone for "viruses in the brain" before and advised me to see another doctor in the area who dealt with immune disorders and viruses as one of the causes of autism, but she persisted. nine0039

nine0039

I will always be grateful to this mother, as well as to other meticulous parents who forced me to read and study to help their children. I went back to textbooks, research, and some new sources, such as Therese Binstock's publications and informal notes on pathogens, viruses, and autoimmunity. As I prepared to work with Susie, I began to research all I could about this complex issue.

Susie was (and still is) a pretty, fragile girl who I would have thought would be 14 years old rather than 16 - her age at the time. Her mother, a teacher/writer who became a housewife after Susie was born, described to me a whole team of tutors who came every day, including weekends and other events, and the enormous effort she put in over the years to get her daughter into a comprehensive school. nine0039

Although Susie was at the level of her class, as a first grader, she made great efforts not to upset her parents and teachers. At the same time, she was socially withdrawn, had no friends, young people were never interested in her, although she was pretty and had an attractive, albeit youthful figure.

She seemed a little dreamy and distracted, although she answered questions to the point quite well. She had strange eating habits - she refused to eat with everyone for years and limited herself to just a few foods. Regarding her medical history, her mother said that Susie developed normally until about age four, when she contracted rubella, a usually mild and rapid childhood illness that is caused by the herpes virus type 6 and is characterized by a rash. nine0039

Her behavior changed after her illness, and although she did not stop talking, she did not seem to study as well as the other children in her class. Mother showed me photographs of Susie from all the years - on Susie's arms and legs, one could notice an intermittent small rash, similar to short exacerbations of rubella. (It turned out she had a chronic, asymptomatic herpesvirus type 6 infection that flared up intermittently.)

I ordered routine tests, which were all within normal limits, introduced Susie to a complex of nutritional supplements (which she agreed to) and suggested a change in diet (which was difficult to persuade her to do). It's much easier to put a 3- or 4-year-old on a BGBK diet than a teenager! nine0039

It's much easier to put a 3- or 4-year-old on a BGBK diet than a teenager! nine0039

She tested positive for IgG (past or chronic infection) and IgM (recent infection or exacerbation) for herpes simplex virus type 6 (rubella). She also had very low levels of NK cell cytotoxicity, which meant that the immune system had a breakdown in the first line of defense that fights viruses.

I was surprised, but Susie's mother was not. She is one of the many smart mothers I have met since I started working with "special" children. I had already injected Susie with a small dose of SSRI (an antiviral drug) hoping to relieve her fear of communication a little, and she seemed to be a little more sociable. nine0039

She had been on a nutritional supplement for several months when I gave her Aciclovir (an antiviral drug effective against many herpes viruses and to varying degrees effective against Epstein-Barr virus and herpes virus type 6).

Approximately a week or ten days after the start of the reception, a striking change occurred in Susie. Her eyes cleared up, she became less detached, more intelligent and generally more emotional, she made friends. It seemed as if her classmates had never seen her before. nine0039

Her eyes cleared up, she became less detached, more intelligent and generally more emotional, she made friends. It seemed as if her classmates had never seen her before. nine0039

Within three months she became a normal naughty teenager, which completely amazed her parents and surprised the tutors who had been with her for years. She soon began to protest against so many classes and, despite the fact that most of them were canceled, she continued to receive B and C grades as usual, which pleasantly surprised her parents.

For the first time in her life, she began to attract the attention of boys and, like all normal schoolchildren, to participate in the usual school intrigues with her joys and misfortunes. She still had some learning difficulties, but the positive changes in all areas of her life were evident to everyone who knew her before her treatment. nine0039

Her parents were delighted and grateful for her "return". The mother's intuition that Susie had medical problems was finally justified in the eyes of Susie's father, a doctor who saw the reason for Susie's behavior solely in her low learning ability, which needed to be corrected with extra classes (as they did with her older sister ).

Susie has only been taking antiviral drugs for a few months, her virus titers have been declining while her NK cell count has increased. Periodically during her treatment, she took TransferFactor and the natural antiviral agent Monolaurin (Lauricidin). Even after her readings stabilized, Susie's mother didn't want to stop taking her antivirals, even though Susie hated the routine blood tests she had to check on her liver during treatment (the liver was fine). nine0039

Finally, by the time we finished school, we gradually stopped all medications. She also got tired of having to take so many supplements when she started to feel better. When she left last fall to take an exam at a private art college, she still had some eccentric eating habits, but we've all come to terms with it.

A few months ago, my parents called me and told me that Susie was getting B's in college and was constantly dating a guy her parents liked. I believe that the diagnosis of autism no longer applies to her, although some oddities in eating still persist. Interestingly, I find these weird eating habits not very different from the habits of many girls her age who care more about being slim than eating right.” (4)

Interestingly, I find these weird eating habits not very different from the habits of many girls her age who care more about being slim than eating right.” (4)

Sources:

1. Firth Uta p. “Autism: Solving the riddle”, 1989

neuroendocrinology, 1995

3. Romani L. “Cytokine modulation of specific and non-specific immunity to Candida albicans”. 1999 Mycoses

4. Children With Starving Brains: A Medical Treatment Guide for Autism Spectrum Disorder, Second Edition Paperback – January 1, 2003. Jaquelyn McCandless

Autism treatment in Israel | Hadassah Clinic

from March 1, 2022, Israel opened the borders for all foreign citizens, read more about the entry rules

Information for the new

Russian -speaking citizens of Israel

Employees of the International Department Operational Department:

- instruct how to collect documents and fill out the declarations necessary for the trip;

- organize face-to-face consultation with a doctor and all necessary procedures; nine0193

- help organize admission to the clinic.

For all questions, please contact our single call center by phone 8(800)550-96-30.

Treatment of autism in Israel is an effective set of medical measures aimed at developing adaptive abilities in a sick child. In Israel, children's health is given special attention. Israeli experts use the entire arsenal of modern medicine in the fight against the disease. nine0039

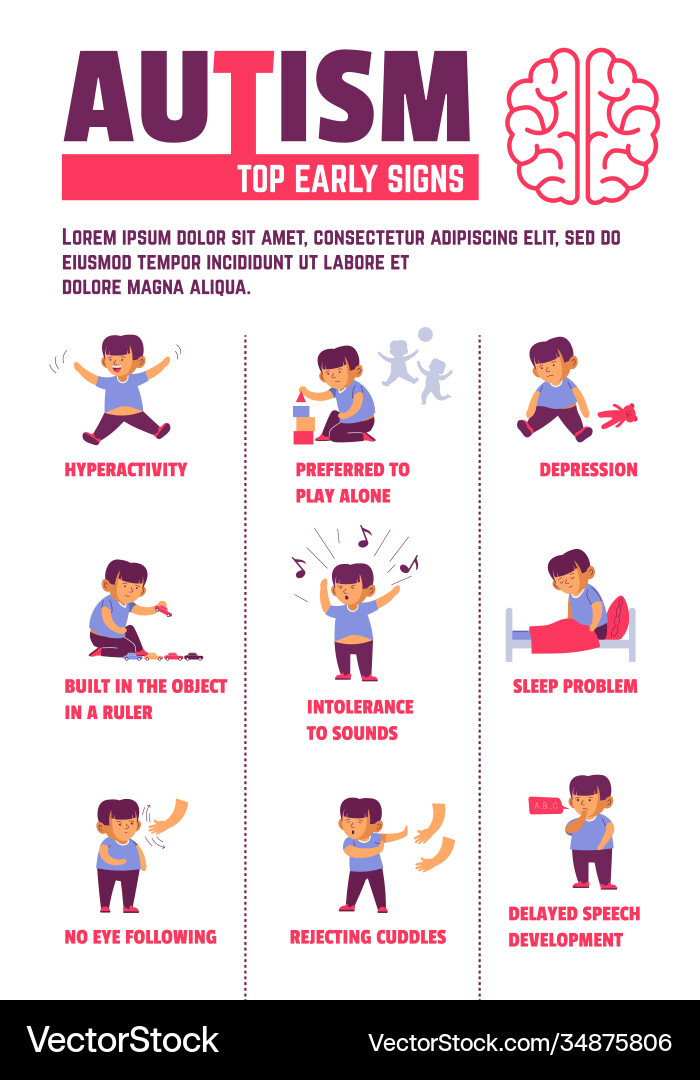

Infantile autism refers to an autistic disorder that occurs when the brain develops abnormally. It is characterized by repetitive movements, a problem in communicating with others, narrow interests. The disease is based on genetic disorders and mutation (about 400 causes in total).

Unwillingness to make contact with people is formed before 3 years, many consider this not a pathology, but an alternative condition. But only a small number of patients manage to live an independent life. nine0039

Most parents prefer to bring children with autism to Israel: positive results of treatment can be found on our website .

Forecast

There are famous and successful people among autistic people whose intellect has not suffered. Recovery is affected not only by timely treatment, but by the form of the disease:

- Asperger's syndrome - "autistic psychopathy", a severe personality disorder in which significant advances can be made in one area. nine0193

- Atypical autism is an umbrella term for neurological disorders that do not have diagnostic criteria for the disease.

- Rett's syndrome is a disintegration characterized by a severe degree of mental retardation.

- Heller's syndrome is a disintegrative disorder characterized by acquired dementia. The prognosis is unfavorable: loss of motor skills, changes in behavioral responses, loss of control over physiological functions.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to completely get rid of the pathology, but Israeli doctors have tremendous experience in making the life of an autistic person more independent. nine0039

nine0039

Statistics

In recent decades, there has been a sharp increase in the incidence of autism, annually by 13%. In the 70s, there was one sick person per 5,000 people, today every 68th is sick.

The use of improved schemes and advanced technologies in Israel for autism increases the effectiveness of treatment: the best doctors of the Hadassah clinic make efforts, knowledge and practical experience so that children adapt to society .

Methods

nine0002 The treatment and recovery of a child with autism in Israel is carried out by psychiatric, neurological, psychological, and pediatric specialists. Patients are consulted by a geneticist, gastroenterologist, speech therapist, epileptologist, occupational therapist, music therapist, art therapist, teachers, social workers. It is not surprising that autistic people from all over the world are brought to Israel for treatment. In Hadassah, an attending physician is attached to a small patient, who supervises him throughout the treatment and rehabilitation process. nine0039

nine0039

Ella Kiyansky - leading psychiatrist, director of the Children's Psychiatric Emergency Center.

Specialization: specialist in general psychiatry, as well as psychiatry for children and adolescents.

Experience — more than 32 years.

Read doctor's resume

The first 3-7 days in Israel, autism diagnostics are carried out, which is included in the cost of the course of treatment . Children can be treated inpatient or outpatient, the child stays in the hospital with his mother, where comfortable conditions are created, there is everything necessary for a long stay. nine0003 In order to make a diagnosis of autism, observation is necessary to identify characteristic signs and stereotyped behavior.

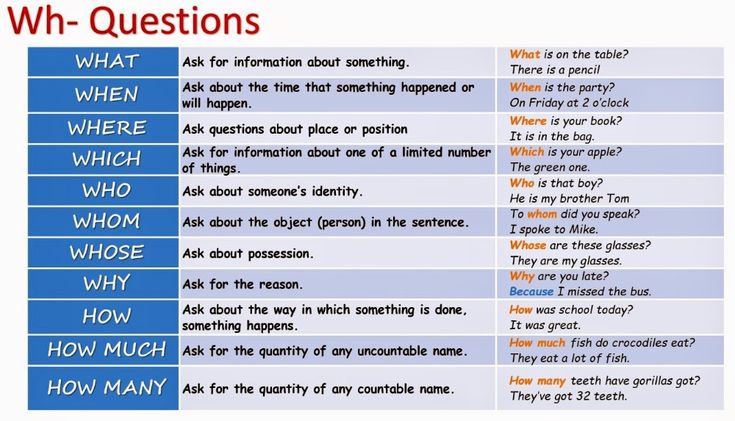

The following diagnostic criteria are used:

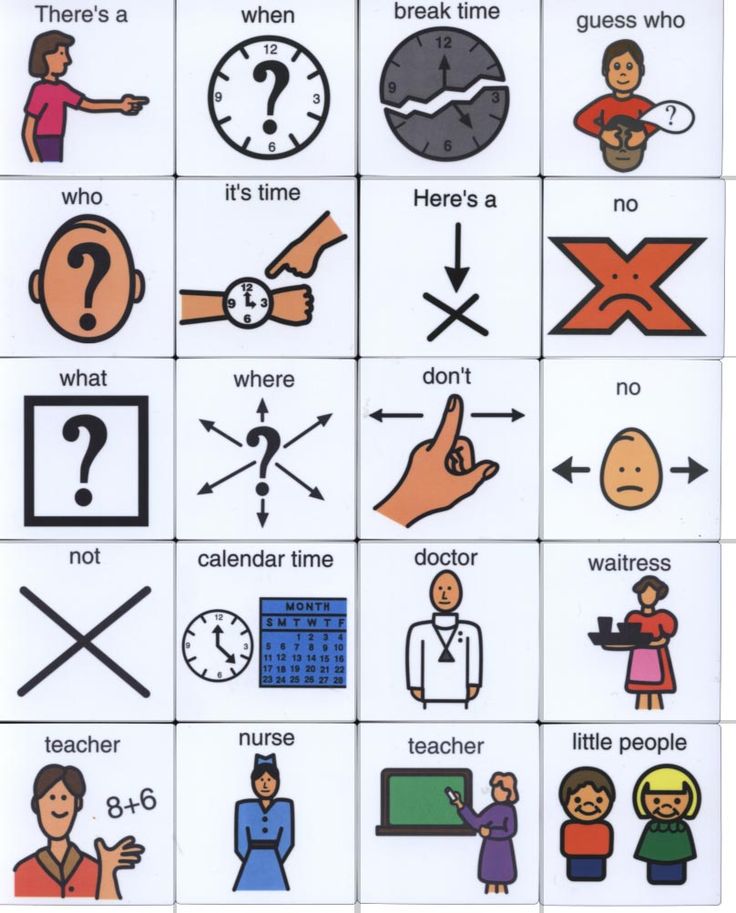

- dysfunction in social interaction is expressed in: the ability to use non-verbal means, the inability to contact peers, the lack of emotional ties and the desire for knowledge;

- qualitative problems in communication: use of facial expressions and gestures instead of speech, inability to carry on a conversation, idiosyncratic language, stereotyped interests and actions, repetition of meaningless rituals, mannerisms, persistent interest in one part of the subject; nine0193

- developmental delay in one of the areas: social, interaction through speech, role-playing games.

Early diagnosis of autism and the use of effective treatment methods in Israel guarantees the success of treatment in most cases .

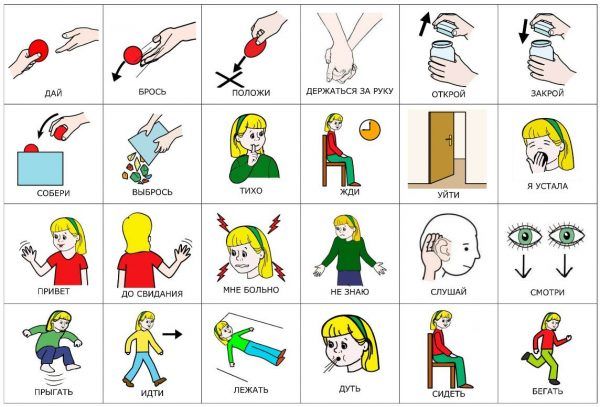

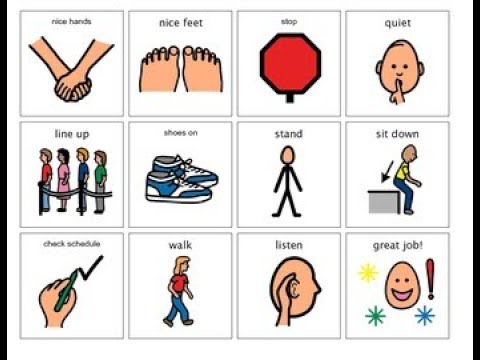

The autism treatment team uses the following methods in combination:

- occupational therapy - classes for self-development;

- art therapy is a fun way of psychological help based on games and creativity; nine0193

- physiotherapy - physiotherapy exercises, massage;

- diet therapy - proper nutrition speeds up the healing process;

- psychoanalysis and psychocorrection - psychologists are trying to artificially develop the missing brain functions;

- visual therapy - video games, video modeling;

- RDI - developmental treatment that takes into account the strengths of the baby;

- ABA Therapy is a science-based therapy that includes many recovery options; nine0193

- sensory integration - based on sensitivity to sensory stimuli;

- instructor activities - an attached instructor who is with the patient all the time, teaches simple skills, without which independent life is impossible;

- pet therapy - communication of a child with horses, dolphins, other animals will help to establish contact with people;

- speech therapy - a speech therapist is connected to classes from the age of 5 years of the patient.