Signs of autism in the womb

How pregnancy may shape a child's autism | Spectrum

Autism is predominantly genetic in origin, but a growing list of preterm exposures for mother and baby may sway the odds.

Photography by Ethan Hill

Even after her first child, Shane, was diagnosed with autism last year at the age of 2, Melissa Patao knew she wanted a bigger family. She was aware that any other children she had would have high odds of being diagnosed with the condition — estimates suggest that about 20 percent of siblings of autistic children also receive a diagnosis — but she was more than willing to take the chance. “I just adore Shane so much; he’s my world,” she says. In August, Patao gave birth to her second son, Zayden.

If it turns out that Zayden is also on the spectrum, “so be it,” Patao says. But all through her pregnancy, she wondered ‘what if?’ She found herself poring over research studies in an attempt to understand his odds of having autism and what might influence them.

Patao, who is training to become a pediatric nurse practitioner, found no shortage of reading material: Last year alone, scientists published more than 100 papers on events during pregnancy that can influence a child’s odds of having autism. Genes determine about 50 to 95 percent of that risk. But that means that “there’s more to the story than just that genetic predisposition,” says Daniele Fallin, a genetic epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Environmental contributions must also factor in.

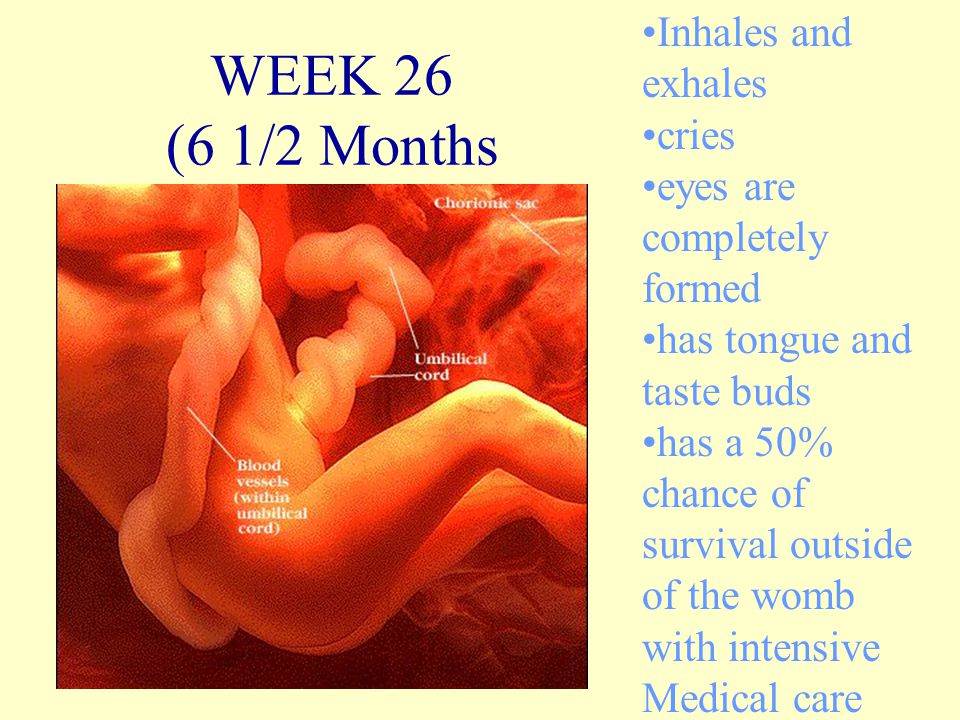

The baby’s earliest environment — the womb — is critical: Because the fetal brain produces about 250,000 neurons every minute during pregnancy, experiences that interfere with that process can affect the developing brain in lasting ways. Studies have linked autism to a number of factors in pregnancy, among them the mother’s diet, the medicines she takes and her mental, immune and metabolic conditions, including preeclampsia (a form of high blood pressure) and gestational diabetes. Other preliminary work has implicated the quality of the air she breathes and the pesticides she is exposed to. And some research suggests that birth complications and birth timing may also play a role.

Other preliminary work has implicated the quality of the air she breathes and the pesticides she is exposed to. And some research suggests that birth complications and birth timing may also play a role.

The relationship between many of these factors and autism is still speculative. “That question of causality, it’s a burden that is very difficult to fulfill,” says Brian Lee, an epidemiologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia. This is generally true of research into environmental exposures, and particularly so for studies in pregnant women: Researchers cannot ethically expose pregnant women to possible risks; observational studies can only identify correlations, not causes; and the results of animal studies do not always extrapolate to people.

But researchers are starting to uncover biological threads that tie some of these prenatal exposures together. Many affect common biochemical pathways previously implicated in autism, such as those involving inflammation and aberrant immunity in both mother and baby. Each may only “contribute a little bit of risk here and there,” Lee says, but it is crucial to try to understand how all the pieces add up.

Each may only “contribute a little bit of risk here and there,” Lee says, but it is crucial to try to understand how all the pieces add up.

Uncertain outcome: Melissa Patao wonders whether her baby, Zayden, has autism like his brother Shane.

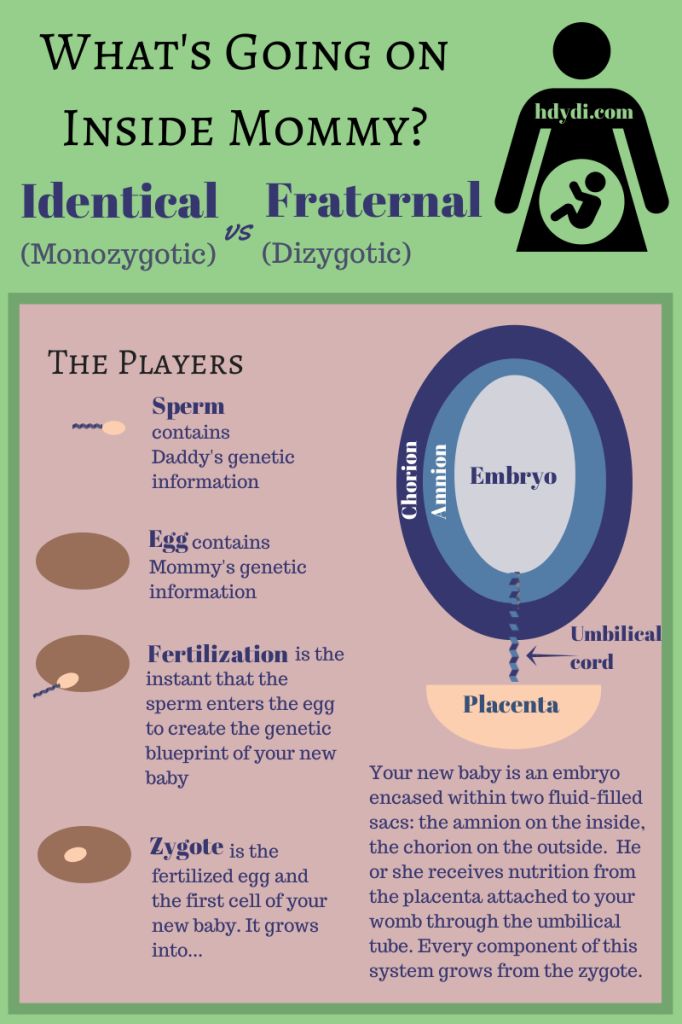

Inside the womb:Autism has been tied to events throughout pregnancy, including the first few days after conception. Even before a tiny human blastocyst attaches itself to the nutrient-rich lining of its mother’s uterus, factors that will shape its nervous system are already in play. In the days immediately following conception, genes that govern brain wiring are turned on and off in a process that requires folate, or vitamin B9. Folate may be important for the building of fundamental brain structures later on, too.

If a mother’s diet is deficient in folate, these processes can go awry, increasing the risk for neural defects, such as spina bifida and possibly autism. In a 2013 study, Norwegian researchers followed more than 85,000 women from 18 weeks into their pregnancies until an average of about six years after delivery, collecting information that included whether and when the women took supplements of folic acid, the synthetic form of folate, as well as the health of their children. Those who took supplements, especially between four weeks before and eight weeks after conception, were about 40 percent less likely to have children diagnosed with autism than those who did not take the supplements. Other studies have linked vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women with autism in their children, but the implications are unclear.

Those who took supplements, especially between four weeks before and eight weeks after conception, were about 40 percent less likely to have children diagnosed with autism than those who did not take the supplements. Other studies have linked vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women with autism in their children, but the implications are unclear.

How strongly a blastocyst attaches to the mother’s uterine wall after fertilization can affect its access to folic acid and other nutrients. A strong attachment ensures that the embryo connects with the mother’s blood vessels and remodels them to supply it with nutrients and oxygen throughout pregnancy, says Cheryl Walker, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of California, Davis. By contrast, a shallow implantation can lead to fetal growth restriction and low birth weight, both of which are linked to autism.

A shallow attachment can also lead to preeclampsia in the mother. Children with autism are twice as likely as typical children to have been exposed to preeclampsia, according to a 2015 study. In a woman with preeclampsia, blood vessels in the placenta “don’t dilate as well, and they don’t end up giving as many resources to that baby,” says Walker, who was involved in the study. As a result, the fetal brain may be starved of nutrients it needs to grow properly.

In a woman with preeclampsia, blood vessels in the placenta “don’t dilate as well, and they don’t end up giving as many resources to that baby,” says Walker, who was involved in the study. As a result, the fetal brain may be starved of nutrients it needs to grow properly.

The fetus’ immune system can also interfere with its brain development. Certain molecules, called cytokines, that control the migration of cells in the immune system are also crucial for neurons and immune cells to get to their correct locations in the nervous system. “The two systems talk to each other in ways that we didn’t realize they did,” says Judy Van de Water, a neuroimmunologist at the University of California, Davis.

Infections during pregnancy may scramble this signaling. A successful pregnancy involves an intricate immune dance: A woman’s immunity has to tamp down so that it does not attack the fetus as a foreign invader but also remain vigilant enough to ward off harmful infections. Even when that goes to plan, though, serious infections can ramp up her immune response, to the detriment of her child. For example, a 1977 study found a surprisingly high prevalence of autism — 1 in 13 — among children born to mothers who were infected with rubella during pregnancy. And a 2015 study that followed more than 2.3 million children born in Sweden from 1984 to 2007 reported that women who are hospitalized for infections during pregnancy have about a 30 percent increase in the odds of having a child with autism compared with other pregnant women.

For example, a 1977 study found a surprisingly high prevalence of autism — 1 in 13 — among children born to mothers who were infected with rubella during pregnancy. And a 2015 study that followed more than 2.3 million children born in Sweden from 1984 to 2007 reported that women who are hospitalized for infections during pregnancy have about a 30 percent increase in the odds of having a child with autism compared with other pregnant women.

Predicting risk: Manish Arora studies chemical exposures that may affect a child’s odds of autism.

That risk may be mediated at least in part by inflammation and disrupted immune signaling in the mother. A 2013 study of 1.2 million Finnish births found that women with the highest levels of C-reactive protein, a common inflammation marker, in their blood are 80 percent more likely to have children diagnosed with autism than women with the lowest levels. Last year, Van de Water and her colleagues reported that women who went on to have autistic children with intellectual disability had elevated blood levels of certain cytokines halfway through gestation.

Some cytokines seem to be particularly important in mediating autism risk. In mice, immune activation contributes to autism only when a subset of immune cells, called T-helper 17 cells, release a cytokine called interleukin 17. In mice without these cells, inflammation during pregnancy does not seem to lead to autism. T-helper 17 cells are produced in response to specific gut bacteria, raising the possibility that pregnant women with these bacteria are especially susceptible to the kind of inflammation that contributes to autism. Eliminating those specific bacteria from pregnant women’s guts might lower the odds of autism in their children — a possibility researchers are investigating.

Obesity, diabetes before and during pregnancy, stress and autoimmune conditions in the mother have been associated with autism in her child, too: All either induce inflammation or impair immune signaling in other ways. These pieces of evidence, taken together, are called the ‘maternal immune activation hypothesis. ’ A meta-analysis of 32 papers published earlier this year found that women who are obese or overweight before pregnancy are 36 percent more likely than women at a healthy weight to have children later diagnosed with autism.

’ A meta-analysis of 32 papers published earlier this year found that women who are obese or overweight before pregnancy are 36 percent more likely than women at a healthy weight to have children later diagnosed with autism.

Van de Water’s work has shown that some autoimmune reactions can even directly damage the fetal brain. (During pregnancy, a woman’s antibodies can cross the placenta and even cross the fetal blood-brain barrier.) In 2013, Van de Water’s team reported that 23 percent of mothers of autistic children carry antibodies to fetal brain proteins, compared with 1 percent of mothers of typical children. No one knows why these women might have these antibodies — it’s “the $50 million question,” Van de Water says — but researchers posit they may be yet another byproduct of a maternal immune system gone haywire. Factors outside the mother’s body can also wield powerful effects.

“We’re starting to put things together that we never, ever thought to look at in combination.Outside the womb:” Judy Van de Water

Manish Arora’s desk at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City is a chaotic jumble of half-empty coffee mugs, philosophy books and baby teeth. The tiny teeth were donated for a study unrelated to autism, but they may uncover secrets about the condition nonetheless, he says.

Arora is many things: a dentist, a scientist and a father to 6-year-old triplets. He is soft-spoken and often speaks in metaphors. In his professional life, he strives to understand how chemical exposures early in life affect brain development, a passion shaped by his childhood growing up on the border of Zambia and what is now Zimbabwe. He remembers trucks spraying pesticides such as DDT on the ground — and sometimes also on children playing outside — to control malaria, a practice that he continued to think about as he got older because of its potential harm.

As Arora knows from his dentistry work, baby teeth provide a record of a body’s chemical exposures. Teeth, he explains, are like trees: As they grow, they create rings — about one-tenth the diameter of a human hair — that record the chemicals and metals they encounter. These growth rings begin to form at the end of the first trimester of gestation and continue throughout life. “Today, you and me are forming a growth ring and it’s capturing everything that we’re exposed to,” he says. By studying the growth rings of discarded baby teeth, he and his colleagues can analyze what fetuses were exposed to in utero. The stress of birth creates a dark mark that can be used as a reference point.

Teeth, he explains, are like trees: As they grow, they create rings — about one-tenth the diameter of a human hair — that record the chemicals and metals they encounter. These growth rings begin to form at the end of the first trimester of gestation and continue throughout life. “Today, you and me are forming a growth ring and it’s capturing everything that we’re exposed to,” he says. By studying the growth rings of discarded baby teeth, he and his colleagues can analyze what fetuses were exposed to in utero. The stress of birth creates a dark mark that can be used as a reference point.

In May, Arora and his colleagues reported an analysis of baby teeth collected from 193 children, including 32 sets of twins in which one twin is autistic and the other is not. The team analyzed the children’s tooth growth rings using a highly sensitive form of mass spectrometry. The levels of metals such as zinc and copper typically cycle together in a pattern — both metals help to regulate neuronal firing — but in autistic children, the cycles are shorter, less regular and less complex than in controls. Arora’s team created an algorithm based on these group differences that can predict a child’s autism with more than 90 percent accuracy.

Arora’s team created an algorithm based on these group differences that can predict a child’s autism with more than 90 percent accuracy.

Arora’s work is part of a growing field that is attempting to decipher what kinds of environmental exposures increase the odds of autism and how they interact with human biology and genetics. These are tough questions to answer. Researchers cannot easily collect blood or saliva samples from fetuses to see what’s circulating through them. Instead, they try to discern fetal exposures by using the mother’s environment as a proxy. If a pregnant woman takes a particular medication, for instance, researchers can extrapolate that the fetus, too, was exposed.

So far, though, results have been mixed. Studies suggest that autism is associated with thalidomide, a drug prescribed for morning sickness in the 1950s and 1960s and later found to cause serious birth defects. Valproate, a drug used to treat epilepsy, bipolar disorder and migraines, is also linked to autism when taken during pregnancy. But for other common drugs, such as antidepressants, an association with autism is harder to discern.

But for other common drugs, such as antidepressants, an association with autism is harder to discern.

Chemical record: Growth rings in baby teeth reveal exposures before and after birth.

Part of the problem is that women take antidepressants for underlying mental-health conditions — so if an association is found, it is often unclear whether the root cause is her medication or her genetics. “It’s very difficult to disentangle,” says Hilary Brown, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto Scarborough in Canada. Last year, through a clever study design, she and her colleagues inched a bit closer to the truth. They studied sibling pairs in which one sibling had been exposed to antidepressants in utero and the other had not, allowing them to control for the severity of the mother’s depression, among other factors. They reported that the siblings exposed to antidepressants were no more likely to have autism than their unexposed siblings. The results suggest that the medications themselves do not increase autism risk.

Some research has also linked the use of acetaminophen (commonly marketed as Tylenol) during pregnancy to autism. But again, it is unclear whether it is acetaminophen that is the problem, or the underlying reason for its use — pain or an infection, leading back to the maternal immune activation hypothesis.

Air pollution might also be linked to autism risk, but the details are hazy. At least 14 studies have suggested an association with autism, and air pollution is known to trigger inflammation, but analyses of individual airborne chemicals have been inconsistent. Researchers are also confused by the fact that cigarette smoking, which contains many of the same chemicals as air pollution, is not associated with the condition.

Certain pesticides, such as chlorpyrifos, can disrupt sex-hormone pathways implicated in animal models of autism. But again, studies linking pesticides to autism have been mixed, and questions about causation are unresolved. More answers may emerge, however, as researchers uncover new ways to study interactions between fetuses and the outside world. In addition to Arora’s work on baby teeth, researchers are investigating what kinds of chemical stories meconium, a newborn’s first feces, can tell.

In addition to Arora’s work on baby teeth, researchers are investigating what kinds of chemical stories meconium, a newborn’s first feces, can tell.

“If it’s a difficult birth … then that increases the risk of autism dramatically.” Sam WangBirth and beyond:

Princeton University neuroscientist Sam Wang has long been interested in autism’s potential environmental causes, but he says he finds the research intimidating. “It’s like the sands of the seas,” he says. “It’s this enormous literature, and people who work in it have all these different perspectives.”

Several years ago, in an attempt to bring clarity to the issue, Wang perused about 100 studies and then ranked dozens of associations between autism and both genetic and environmental factors by their relative risk ratios. He described his findings in a 2014 op-ed in The New York Times.

What came out on top in Wang’s analysis of environmental factors was birth — in particular, rare birth injuries to the cerebellum, a brain region that coordinates muscle movements, among other functions. “If it’s a difficult birth, or there’s a bleed on the cerebellum, then that increases the risk of autism dramatically,” by a whopping 3,800 percent, he says. “It’s bigger than any other risk factor, other than sharing your entire genome with a person with autism.” Wang’s research supports the link, too: He has shown that mice with early damage to the cerebellum later have serious cognitive and behavioral problems that mimic autism traits.

“If it’s a difficult birth, or there’s a bleed on the cerebellum, then that increases the risk of autism dramatically,” by a whopping 3,800 percent, he says. “It’s bigger than any other risk factor, other than sharing your entire genome with a person with autism.” Wang’s research supports the link, too: He has shown that mice with early damage to the cerebellum later have serious cognitive and behavioral problems that mimic autism traits.

The timing of birth also made Wang’s list: Babies born at least nine weeks premature seem to have higher odds of autism, he found.

When Noelle Mathias found out she was pregnant with her eldest daughter, Elena, in 2008, she took good care of herself. Mathias exercised, ate well and didn’t drink alcohol or smoke. “As far as I knew, it was a normal pregnancy,” she recalls. But her water broke early at 36 weeks and Elena was born less than 24 hours later. When Elena was 2, Mathias and her husband noticed she wasn’t responding to her name. They had Elena evaluated and, soon after, the girl was diagnosed with autism.

It’s impossible to know whether Elena’s preterm birth played a causal role in her diagnosis. Is being born early itself the issue, or might an underlying genetic susceptibility or environmental insult increase the odds of both preterm birth and autism?

Mathias’ second pregnancy was full term, and her daughter Elisa, now 8, is developmentally typical. But in Mathias’ third pregnancy, her water broke at only 25 weeks and she spent 53 days in the hospital on bed rest, hoping to delay birth as long as possible. Her son Emmanuel held out until 33 weeks and then spent time in the neonatal intensive care unit. He’s 2 now and seems to be developing typically.

Mathias has no idea why her first child has had a different outcome from the others. Parsing the risk for any one child is complicated by the fact that autism “isn’t just a ‘you have it or you don’t’ condition — it’s this wide phenotypic spectrum,” says Kristen Lyall, an epidemiologist at Drexel University’s A.J. Drexel Autism Institute. Perhaps some environmental factors preferentially influence social skills, whereas others primarily shape cognitive development, for instance.

Perhaps some environmental factors preferentially influence social skills, whereas others primarily shape cognitive development, for instance.

Keeping watch: The Patao family participates in a ‘baby sibling’ study, monitoring Zayden for signs of autism.

It may also be that certain combinations of factors — several environmental exposures in a row, perhaps, or a particular exposure along with a genetic susceptibility — are necessary to tilt a child’s brain development toward autism. A 2016 study, for example, found that in mice, maternal infection can modulate the effects of genes linked to autism, including CNTNAP2. “We’re starting to put things together that we never, ever thought to look at in combination,” Van de Water says. “You’ve got people working together that never would’ve necessarily crossed paths.” As part of those efforts, researchers are looking for fetal and infant biomarkers of autism, such as irregular cytokine profiles, anti-fetal antibodies and markers of oxidative stress, which might open the door to earlier and more effective interventions.

Because Zayden has an older brother with autism, Melissa Patao was able to enroll him in a ‘baby sibling’ study at the Yale Child Study Center. Researchers there followed Patao’s pregnancy with Zayden and plan to continue to track his development into toddlerhood. For now, Zayden is doing everything a 3-month-old usually does: He is smiling and interacting with his family, and he recently started laughing. His brother Shane is also doing well — he is engaging in pretend play and his language skills, which are only slightly delayed, are continually improving.

Patao welcomes the fact that Zayden will be monitored so closely. She and her husband will know if he shows autism traits early, and he will have access to recommended interventions at the youngest possible age, when they are known to have the largest impact. “Being part of this study was something so meaningful for me,” Patao says. “It totally took away the overwhelming anxiety of wondering, ‘what if?’”

Cite this article: https://doi. org/10.53053/EPQM9169

org/10.53053/EPQM9169

Syndication

This article was republished in The Atlantic.

TAGS: antidepressants, autism, baby sibs, biomarkers, CNTNAP2, environment, epigenetics, fever, immune system, maternal infection, obesity, pregnancy, valproic acid

A routine prenatal ultrasound can identify early signs of autism, study finds -- ScienceDaily

Science News

from research organizations

- Date:

- February 9, 2022

- Source:

- Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

- Summary:

- A routine prenatal ultrasound in the second trimester can identify early signs of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), a new study has found.

- Share:

FULL STORY

A routine prenatal ultrasound in the second trimester can identify early signs of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), a new study by Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and Soroka Medical Center has found.

advertisement

Researchers from the Azrieli National Centre for Autism and Neurodevelopment Research published their findings recently in the peer-reviewed journal Brain.

The researchers examined data from hundreds of prenatal ultrasound scans from the fetal anatomy survey conducted during mid-gestation. They found anomalies in the heart, kidneys, and head in 30% of fetuses who later developed ASD, a three times higher rate than was found in typically developing fetuses from the general population and twice as high as their typically developing siblings.

Anomalies were detected more often in girls than in boys and the severity of the anomalies was also linked to the subsequent severity of ASD.

This study and others will be discussed at the Israeli Meeting for Autism Research to be held February 15-16 at BGU.

Prof. Idan Menashe, a member of the Centre and the Department of Public Health in the Faculty of Health Sciences, led the research with his MD/PhD student Ohad Regev.

"Doctors can use these signs, discernable during a routine ultrasound, to evaluate the probability of the child being born with ASD," says Prof. Menashe, "Previous studies have shown that children born with congenital diseases, primarily those involving the heart and kidneys, had a higher chance of developing ASD. Our findings suggest that certain types of ASD that involve other organ anomalies, begin and can be detected in utero."

A previous study of the Centre found early diagnosis and treatment increased social ability by three times as much. Prenatal diagnosis could mean a course of treatment from birth instead of waiting until age 2 or 3 or even later.

The study was conducted as part of Ohad Regev's doctoral thesis, advised by Prof. Idan Menashe and Prof. Reli Hershkovitz. Additional researchers from Ben-Gurion University and Soroka Medical Center included: Dr. Amnon Hadar, Dr. Gal Meiri, Dr. Hagit Flusser, Dr. Analya Michaelovski, and Prof. Ilan Dinstein.

This study was supported by a grant from the Israel Science Foundation (No. 1092/21) and made use of the National Autism Database supported by the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Technology, and the Azrieli Foundation.

1092/21) and made use of the National Autism Database supported by the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Technology, and the Azrieli Foundation.

make a difference: sponsored opportunity

Story Source:

Materials provided by Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

- Ohad Regev, Amnon Hadar, Gal Meiri, Hagit Flusser, Analya Michaelovski, Ilan Dinstein, Reli Hershkovitz, Idan Menashe. Association between ultrasonography foetal anomalies and autism spectrum disorder. Brain, 2022; DOI: 10.1093/brain/awac008

Cite This Page:

- MLA

- APA

- Chicago

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. "A routine prenatal ultrasound can identify early signs of autism, study finds. " ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 9 February 2022. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2022/02/220209112107.htm>.

" ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 9 February 2022. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2022/02/220209112107.htm>.

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. (2022, February 9). A routine prenatal ultrasound can identify early signs of autism, study finds. ScienceDaily. Retrieved November 22, 2022 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2022/02/220209112107.htm

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. "A routine prenatal ultrasound can identify early signs of autism, study finds." ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2022/02/220209112107.htm (accessed November 22, 2022).

advertisement

"Children of the rain". What you need to know about autism

11 April 2019 12:01

Behind the poetic expression "children of the rain" lies the daily feat of people who are faced with a diagnosis of autism. Children who will never be able to perceive themselves as part of the world around them, and parents for whom every day is a series of battles and victories. First, fighting with yourself, accepting and realizing that their child will never be cured, and then fighting the disease for every gesture, every smile, every look and word of the child - small, but such important victories.

First, fighting with yourself, accepting and realizing that their child will never be cured, and then fighting the disease for every gesture, every smile, every look and word of the child - small, but such important victories.

Scientists have not been able to reliably establish the causes of the disease. It is known about the genetic predisposition: signs of autism are more often manifested in people whose family already has an autistic person. Pregnancy in mothers of such children proceeds normally, and the children themselves are often very attractive in appearance - autism, as a rule, does not affect the physical development of the child. However, the development of autism is still in some cases associated with the manifestation of other diseases:

- cerebral palsy;

- maternal rubella infection during pregnancy;

- tuberous sclerosis;

- impaired fat metabolism (the risk of having a baby with autism is greater in obese women).

All of these conditions can have a bad effect on the brain and, as a result, provoke symptoms of autism. However, what autism is, and what are the causes of its manifestation, is still not completely clear.

However, what autism is, and what are the causes of its manifestation, is still not completely clear.

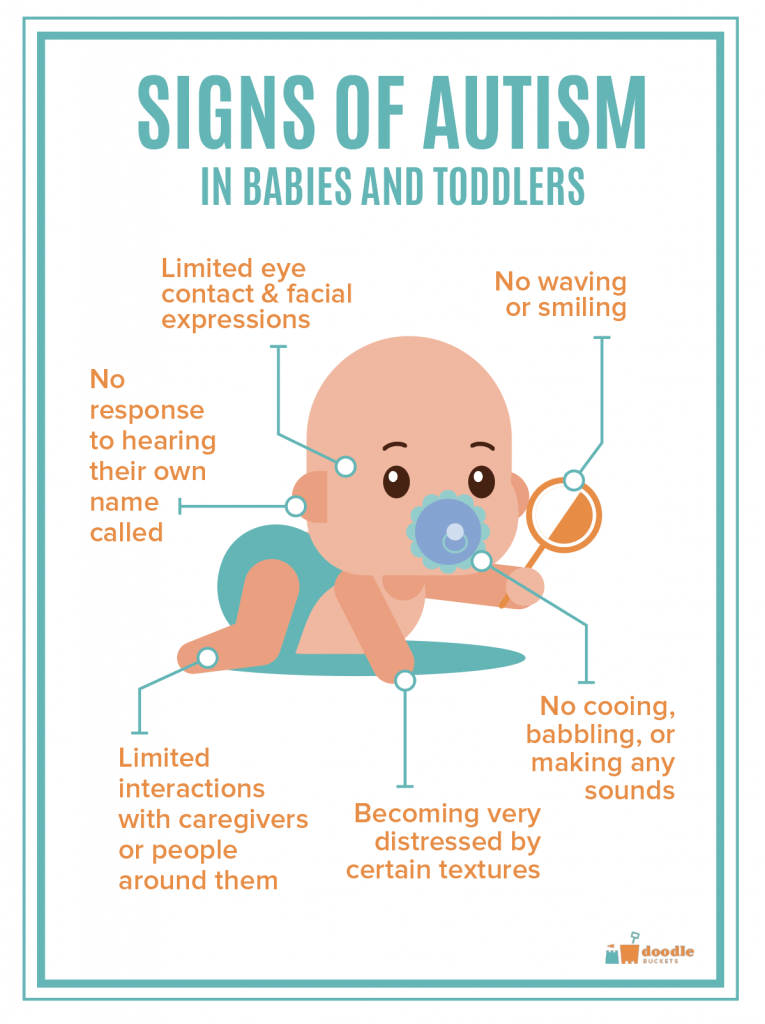

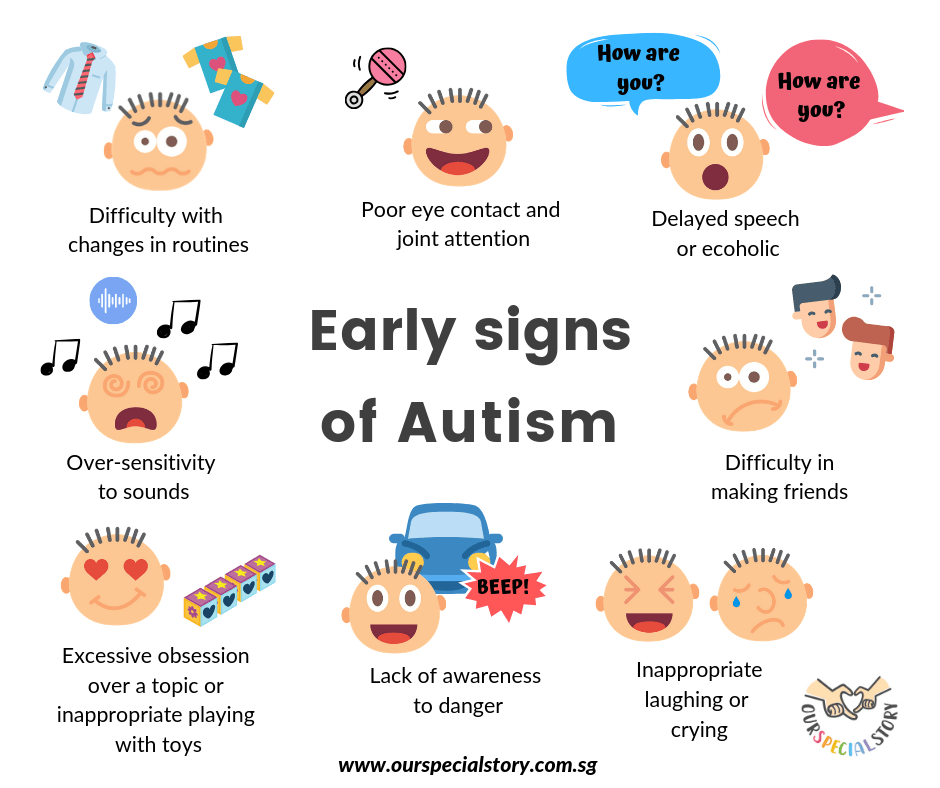

Early diagnosis plays an important role in the further development of an autistic child. Autism in children is manifested by certain signs. Early childhood autism is a condition that can manifest itself in children at a very early age - both at 1 year old and at 2 years old. What is autism in a child, and whether this disease occurs, is determined by a specialist. But you can independently figure out what kind of illness a child has and suspect him, based on information about the signs of such a condition.

Early signs of autism in a child

This syndrome is characterized by 4 main signs. In children with this disease, they can be determined to varying degrees.

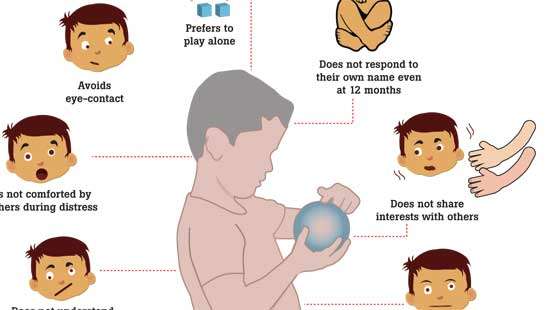

Signs of autism in children are as follows:

- impaired social interaction;

- broken communication;

- stereotyped behaviour;

- early symptoms of childhood autism in children under 3 years of age.

The first signs of autistic children can be expressed as early as the age of 2 years. Symptoms may be mild when eye-to-eye contact is impaired, or more severe when it is completely absent. As a rule, autism manifests itself very early - even before the age of 1, parents can recognize it. In the first months, such children are less mobile, react inadequately to stimuli from the outside, they have poor facial expressions.

The child cannot perceive a holistic image of a person who is trying to communicate with him. Even in the photo and video, you can recognize that such a baby's facial expressions do not correspond to the current situation. He does not smile when someone tries to amuse him, but he can laugh when the reason for this is not clear to anyone close to him. The face of such a baby is mask-like, grimaces periodically appear on it.

Baby uses gestures only to indicate needs. As a rule, even in children under one year old, interest is sharply shown if they see an interesting object - the baby laughs, points with a finger, and demonstrates joyful behavior. The first signs in children under 1 year old can be suspected if the child does not behave like this. Symptoms of autism in children under one year old are manifested by the fact that they use a certain gesture, wanting to get something, but do not seek to capture the attention of their parents by including them in their game.

The first signs in children under 1 year old can be suspected if the child does not behave like this. Symptoms of autism in children under one year old are manifested by the fact that they use a certain gesture, wanting to get something, but do not seek to capture the attention of their parents by including them in their game.

An autistic person cannot understand other people's emotions. How this symptom manifests itself in a child can be traced already at an early age. If ordinary children have a brain designed in such a way that they can easily determine when they look at other people, they are upset, cheerful or scared, then an autistic person is not capable of this.

The child is not interested in peers. Already at the age of 2, ordinary children strive for company - to play, to get acquainted with their peers. Signs of autism in children of 2 years old are expressed by the fact that such a baby does not participate in games, but plunges into his own world. Those who want to know how to recognize a child 2 years old and older should simply look at the company of children: an autist is always alone and does not pay attention to others or perceives them as inanimate objects.

It is difficult for a child to play with imagination and social roles. Children 3 years old and even younger play, fantasizing and inventing role-playing games. In autistics, symptoms at 3 years old may be expressed by the fact that they do not understand what a social role in the game is, and do not perceive toys as integral objects. For example, signs of autism in a child of 3 years old can be expressed by the fact that the baby spins the wheel of a car for hours or repeats other actions.

Child does not respond to emotions and communication from parents. Previously, it was believed that such children are not emotionally attached to their parents at all. But now scientists have proven that when a mother leaves, such a child at 4 years old and even earlier shows anxiety. If family members are around, he looks less obsessed. However, in autism, signs in children of 4 years old are expressed by a lack of reaction to the fact that parents are absent. The autist shows anxiety, but he does not try to return his parents.

In children under 5 years of age and later, there is a delay in speech or its complete absence (mutism). The speech is incoherent, the child repeats the same phrases, devoid of meaning, speaks of himself in the third person. He does not respond to other people's speech either. When the “age of questions” comes, parents will not hear them from the baby, and if they do, then these questions will be monotonous and without practical significance.

Stereotyped behavior includes obsession with one activity, repetition of daily rituals, development of fears and obsessions. At the same time, if the sequence of the ritual is violated, the child becomes hysterical or may show aggression or self-aggression.

Can autism be cured and is it curable at all? Unfortunately, there is no cure. How you can help your child depends on each individual case. Drug treatment is prescribed only in case of destructive behavior of a small patient. But, despite the fact that the disease is not curable, it is possible to correct the situation. The best "treatment" in this case is regular practice every day and the creation of the most favorable environment for the autistic. Classes are held in stages:

The best "treatment" in this case is regular practice every day and the creation of the most favorable environment for the autistic. Classes are held in stages:

- To form the skills that are needed for training. If the child does not make contact, gradually establish it, not forgetting who it is - autistics. Gradually it is necessary to develop at least the rudiments of speech.

- Eliminate forms of behavior that are non-constructive: aggression, self-aggression, fears, withdrawing into oneself, etc.

- Learn to observe, imitate.

- Teaching social games and roles.

- Learn to make emotional contact.

The most common treatment for autism is practiced according to the principles of behaviorism (behavioral psychology). One of the subtypes of such therapy is ABA therapy. The basis of this treatment is to observe what the reactions and behavior of the baby look like. After all the features are studied, incentives are selected for a particular autist. Speech therapy practice is obligatory: if the kid regularly works with a speech therapist, his intonation and pronunciation are getting better. At home, parents help the child develop self-service and socialization skills. Since autists have no motivation to play, they get used to the daily routine, everyday affairs, cards are created where the order of performing this or that action is written or drawn.

Speech therapy practice is obligatory: if the kid regularly works with a speech therapist, his intonation and pronunciation are getting better. At home, parents help the child develop self-service and socialization skills. Since autists have no motivation to play, they get used to the daily routine, everyday affairs, cards are created where the order of performing this or that action is written or drawn.

Why is early diagnosis important? There are conditions that mimic autism that can be confused with its symptoms. But other methods are used to correct them.

ZPRR with autistic features

The symptoms of this disease are associated with a delay in psychoverbal development. They are in many ways similar to the signs of autism. Starting from a very early age, the baby does not develop in terms of speech in the way that existing norms suggest. In the first months of life, he does not babble, then he does not learn to speak simple words. At 2-3 years old, his vocabulary is very poor. Such children are often poorly developed physically, sometimes hyperactive. The final diagnosis is made by the doctor. It is important to visit a psychiatrist, speech therapist with the child.

Such children are often poorly developed physically, sometimes hyperactive. The final diagnosis is made by the doctor. It is important to visit a psychiatrist, speech therapist with the child.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

This condition is also often mistaken for autism. With a lack of attention, children are restless, it is difficult for them to study at school. There are problems with concentration, such children are very mobile. Even in adulthood, echoes of this state remain, because it is difficult for such people to remember information and make decisions. You should try to diagnose this condition as early as possible, practice treatment with psychostimulants and sedative drugs, and visit a psychologist.

Hearing loss

These are various hearing impairments, both congenital and acquired. Hearing-impaired children also have speech delays. Therefore, such children do not respond well to the name, fulfill requests and may seem naughty. At the same time, parents may suspect autism in children. But a professional psychiatrist will definitely send the baby for an examination of auditory function.

At the same time, parents may suspect autism in children. But a professional psychiatrist will definitely send the baby for an examination of auditory function.

Hearing aid helps solve problems.

Schizophrenia

Autism was previously considered one of the manifestations of schizophrenia in children. However, it is now clear that these are two completely different diseases. Schizophrenia in children begins later - at 5-7 years. The symptoms of this disease appear gradually. Such children have obsessive fears, talk to themselves, later delusions and hallucinations appear. This condition is treated with medication.

It is important to understand that autism is not a death sentence. Indeed, with proper care, the earliest correction of autism and support from specialists and parents, such a baby can fully live, learn and find happiness, becoming an adult.

early signs of autism can be detected on prenatal ultrasound

Researchers at Ben-Gurion University in Israel have made a major announcement: the first signs of autism in a fetus can be detected as early as the second trimester of pregnancy. On ultrasound during prenatal screening, fetuses who developed autism after birth show abnormalities in the structure of the heart, kidneys, and head. The results of this study have already been published by the journal Brain.

On ultrasound during prenatal screening, fetuses who developed autism after birth show abnormalities in the structure of the heart, kidneys, and head. The results of this study have already been published by the journal Brain.

Scientists compared ultrasound findings of fetuses who later developed autism with those of their healthy siblings and their peers who did not have any developmental abnormalities. Approximately 30% of fetuses subsequently diagnosed with autism were found to have abnormal anatomical findings during screening during the second trimester of pregnancy. This indicator is three times higher than the rate of this kind of pathology in the general population and two times higher than in peers without developmental disabilities.

The ultrasound findings that showed the strongest association with autism were abnormalities in the development of the heart, kidneys, and head. These findings were more common in girls with autism and were also associated with the severity of autistic symptoms in children.

"The results of this study show that early signs of autism can be detected in the womb," says study leader Prof. Ben-Gurion - "Physicians will be able to use these signs, which can be found on conventional ultrasound, to assess the likelihood of having a child with autism."

These ultrasound results are not 100% positive for autism, but at least then doctors could use them to refer a woman for a genetic diagnosis, explained Prof. Reli Hershkovitz.

"Previous studies have shown that children born with congenital disorders, especially heart and kidney disorders, are more likely to develop autism." Professor Menashe said.

Other related news:

- New discoveries in the study of autism

- Researchers at MC Chilov discovered the "Achilles' heel" of pancreatic cancer: a path to effective therapy

- Israeli study: Cancer can be prevented with peptide group

- Hope for patients with recurrent prostate cancer: Ichilov Medical Center confirms the effectiveness of the "citrus" drug

Publication date: 02/10/2022

Author of article

Dr.