Shapiro emdr therapy

History of EMDR - EMDR Institute

Shapiro then conducted a case study4 and a controlled study1 to test the effectiveness of EMD. In the controlled study, she randomly assigned 22 individuals with traumatic memories to two conditions: half received EMD, and half received the same therapeutic procedure with imagery and detailed description replacing the eye movements. She reported that EMD resulted in significant decreases in ratings of subjective distress and significant increases in ratings of confidence in a positive belief. Participants in the EMD condition reported significantly larger changes than those in the imagery condition.

Shapiro wrote “a single session of the procedure was sufficient to desensitize subjects’ traumatic memories, as well as dramatically alter their cognitive assessments

6.” Unfortunately, Shapiro has often been erroneously cited as claiming that “EMDR can cure [posttraumatic stress disorder] PTSD in one session (F. Shapiro, 1989).”7 Shapiro never made this statement; what she actually wrote was that the EMD procedure "serves to desensitize the anxiety … not to eliminate all PTSD-related symptomatology and complications, nor to provide coping strategies for the victims8” and reported "an average treatment time of five sessions"8 to comprehensively treat PTSD.

1989 was the first year that controlled studies investigating the treatment of PTSD were published. Besides Shapiro’s article, three other studies9,10,11 were published. The Brom et al.9 study compared the results of psychodynamic therapy, hypnotherapy, and desensitization and provided an average of 16 sessions. It found clinically significant treatment effects for 60% of the civilian participants, with no differences between the conditions. The Cooper and Clum10 study compared flooding to standard care in a Veterans Administration Hospital. They reported moderate clinical effects after 6-14 sessions, with a 30% patient drop-out rate. The Keane et al.11 (1989) study compared flooding to a wait-list control for veteran participants and reported moderate clinical effects after 14-16 sessions. [See Comparison of EMDR and Cognitive Behavioral Therapies for more information.

The Keane et al.11 (1989) study compared flooding to a wait-list control for veteran participants and reported moderate clinical effects after 14-16 sessions. [See Comparison of EMDR and Cognitive Behavioral Therapies for more information.

Shapiro continued to develop this treatment approach, incorporating feedback from clients and other clinicians who were using EMD. In 1991 she changed the name to Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing12 (EMDR) to reflect the insights and cognitive changes that occurred during treatment, and to identify the information processing theory that she developed to explain the treatment effects.

Because EMDR therapy was an effective treatment, achieving results very quickly for many clients, Shapiro felt an ethical obligation to teach other clinicians so that individuals suffering from PTSD could find relief. However, EMDR was still experimental since it had not received independent confirmation through other controlled studies. She attempted to resolve this ethical dilemma by teaching EMDR only to licensed clinicians, and by ensuring that everyone who learned the approach was trained by the EMDR Institute in the same model. That way safeguards would be in place, clinicians would be taught to inform clients of its status, and a feedback system would allow everyone that was trained to get the most up to date information. In 1995, after other controlled studies had been published, the label “experimental” and the training restrictions were removed and a textbook of procedures was published13 . Shapiro has been severely criticized by some for her method of dissemination, because she initially restricted training and because she taught an experimental procedure. However, these critics ignore the APA ethics code mandated responsibilities of an innovator to determine training practices and the fact that even as late as 1998, there were no treatments for PTSD that were designated as well-established and empirically validated15.

She attempted to resolve this ethical dilemma by teaching EMDR only to licensed clinicians, and by ensuring that everyone who learned the approach was trained by the EMDR Institute in the same model. That way safeguards would be in place, clinicians would be taught to inform clients of its status, and a feedback system would allow everyone that was trained to get the most up to date information. In 1995, after other controlled studies had been published, the label “experimental” and the training restrictions were removed and a textbook of procedures was published13 . Shapiro has been severely criticized by some for her method of dissemination, because she initially restricted training and because she taught an experimental procedure. However, these critics ignore the APA ethics code mandated responsibilities of an innovator to determine training practices and the fact that even as late as 1998, there were no treatments for PTSD that were designated as well-established and empirically validated15. At that time, independent reviewers for the Clinical Psychology Division of the American Psychological Association identified three treatments with “probable efficacy.” These were EMDR, exposure therapy, and stress inoculation therapy.

At that time, independent reviewers for the Clinical Psychology Division of the American Psychological Association identified three treatments with “probable efficacy.” These were EMDR, exposure therapy, and stress inoculation therapy.

Since the initial studies were published in 1989, hundreds of case studies have been published, and there have been numerous controlled outcome studies16 . These studies have demonstrated EMDR’s effectiveness in PTSD treatment and EMDR is now recognized as efficacious in the treatment of PTSD [See Efficacy of EMDR and Summary of PTSD Studies].

A professional association, independent from Shapiro and the EMDR Institute was founded in 1995 to establish standards for training and practice. The EMDR International Association (EMDRIA) declares that its primary objective is “to establish, maintain and promote the highest standards of excellence and integrity in Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) practice, research and education. ” Information about EMDRIA is available at www.emdria.org

” Information about EMDRIA is available at www.emdria.org

Despite its demonstrated effectiveness, similar to most new approaches in psychotherapy, EMDR has been surrounded by controversy. While some critics have labeled EMDR a “pseudoscience” others have commented that these conclusions are based on misinterpretations of the literature [see "Confusion, Misinformation, and Charges of "Pseudoscience"]. Another area of debate is the role of eye movements in EMDR [See Eye Movements and Alternate Dual Attention Stimuli and What has research determined about EMDR's eye movement component? In the Commonly Asked Questions section.

1Shapiro, F. (1989). Efficacy of the eye movement desensitization procedure in the treatment of traumatic memories. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2, 199-223.

2Shapiro, F. & Forrest, M. (1997). EMDR The Breakthrough Therapy for Overcoming Anxiety, Stress and Trauma. New York: Basic Books

New York: Basic Books

5Shapiro, F. (1989). Eye movement desensitization: A new treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 20, 211-217.

6Shapiro, F. (1989). Efficacy of the eye movement desensitization procedure in the treatment of traumatic memories. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2, 199-223

7Lohr, J. M., Tolin, D. F., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (1998). Efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Implications for behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy, 29, 123-156.

8Shapiro, F. (1989). Efficacy of the eye movement desensitizatioin procedure in the treatment of traumatic memories. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2, 199-223.

9Brom, D., Kleber, R. J., & Defares, P. B. (1989). Brief psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, 607-612

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, 607-612

10Cooper, N.A., & Clum, G.A. (1989). Imaginal flooding as a supplementary treatment for PTSD in combat veterans: A controlled study. Behavior Therapy, 20, 381-391.

11Keane, T.M., Fairbank, J.A., Caddell, J.M., & Zimmering, R.T., (1989). Implosive (flooding) therapy reduces symptoms of PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans. Behavior Therapy, 20, 245-260.

12Shapiro, F., (1991). Eye movement desensitization & reprocessing procedure: From EMD to EMD/R-a new treatment model for anxiety and related traumata. Behavior Therapist, 14, 133-135.

13Shapiro, F. (1995). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing: Basic Principles, Protocols and Procedures (1st edition). New York: Guilford Press

15Chambless, D.L., Baker, M.J., Baucom, D.H., Beutler, L. E., Calhoun, K.S., Crits-Christoph, P., Daiuto, A., DeRubeis, R., Detweiler, J., Haaga, D.A.F., Bennett Johnson, S., McCurry, S., Mueser, K.T., Pope, K.S., Sanderson, W.C., Shoham, V., Stickle, T., Williams, D.A., & Woody, S.R. (1998) . Update on empirically validated therapies, II., The Clinical Psychologist, 51, 3-16.

E., Calhoun, K.S., Crits-Christoph, P., Daiuto, A., DeRubeis, R., Detweiler, J., Haaga, D.A.F., Bennett Johnson, S., McCurry, S., Mueser, K.T., Pope, K.S., Sanderson, W.C., Shoham, V., Stickle, T., Williams, D.A., & Woody, S.R. (1998) . Update on empirically validated therapies, II., The Clinical Psychologist, 51, 3-16.

16For complete listing see See Shapiro, F., (2001). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing: Basic Principles, Protocols and Procedures (2nd edition). New York: Guilford Press

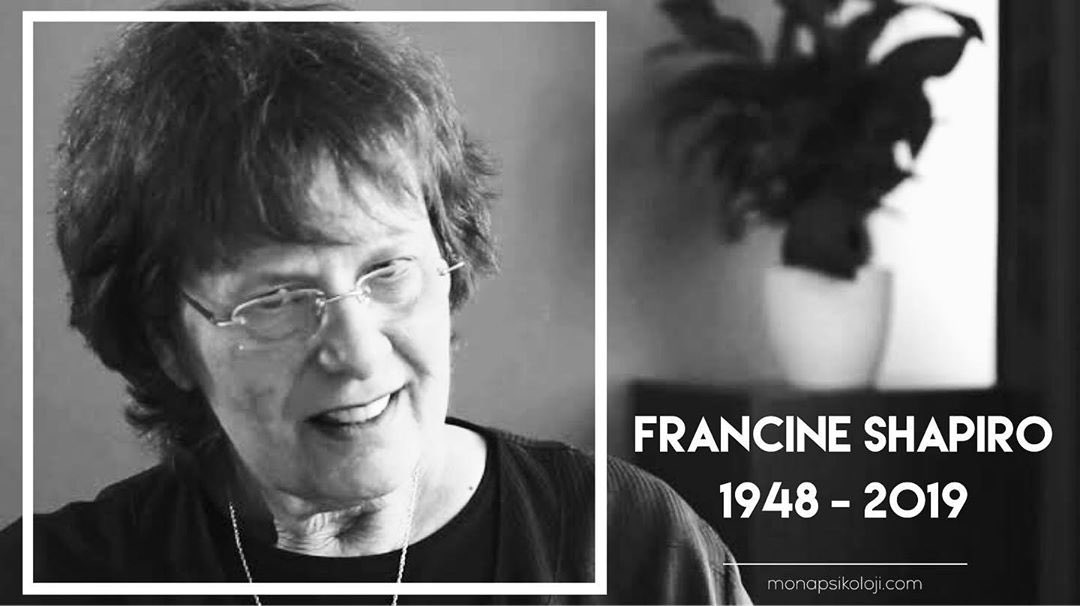

EMDR Therapy Beginnings: Francine Shapiro

The dawn of a new year has us appreciating new beginnings. New projects and fresh starts often need persistence and courage to get them off the ground. The beginning of EMDR therapy was no exception as Francine Shapiro, Ph.D., laid the foundation for this therapy even in the midst of doubts and questions. In the beginning stages of projects or endeavors, it is important to be curious, open-minded, and hopeful for future change. Dr. Shapiro and early EMDR clinicians demonstrated these qualities by researching and pursuing client success while developing the principles of EMDR therapy. We want to honor Dr. Shapiro’s courage, persistence, and curiosity by sharing a collection of resources below. Included are valuable academic and popular writings, videos, podcasts, and book contributions.

Dr. Shapiro and early EMDR clinicians demonstrated these qualities by researching and pursuing client success while developing the principles of EMDR therapy. We want to honor Dr. Shapiro’s courage, persistence, and curiosity by sharing a collection of resources below. Included are valuable academic and popular writings, videos, podcasts, and book contributions.

_______________________________________________________________________

Peer-Reviewed Research Articles, Sole Author:Please note that due to publication and copyright protection, some articles may not be available in an open-access form, however, we have indicated those that are with ‘Open access‘ in front of the doi link. In addition, as Dr. Shapiro was a prolific writer, it is very possible we have some missing articles. We would be happy to add them in if brought to our attention at [email protected].

Shapiro, F. (1989a). Efficacy of the eye movement desensitization procedure in the treatment of traumatic memories. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2(2), 199-223. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490020207

Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2(2), 199-223. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490020207

Shapiro, F. (1989b). Eye movement desensitization: A new treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 20(3), 211-217. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(89)90025-6

Shapiro, F. (1991). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: From EMD to EMDR/R – a new treatment model for anxiety and related traumata. The Behavior Therapist, 14(5), 133-135.

Shapiro, F. (1993). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) in 1992. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(3), 417-421. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490060312

Shapiro, F. (1994a). Alternative stimuli in the use of EMD(R). Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 25(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(94)90071-X

Shapiro, F. (1994b). EMDR: In the eye of a paradigm shift. The Behavior Therapist, 17, 153-157.

Shapiro, F. (1996a). Errors of context and review of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing research. Journal of Behavior Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry, 27(3), 313-317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(96)00035-3

Shapiro, F. (1996b). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): Evaluation of controlled PTSD research. Journal of Behavior Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry, 27(3), 209-218. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(96)00029-8

Shapiro, F. (1999). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and the anxiety disorders: Clinical and research implications of an integrated psychotherapy treatment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 13(1-2), 35-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(98)00038-3

Shapiro, F. (2001). The challenges of treatment evolution and integration. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 43(3-4), 183-186. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2001.10404275

Shapiro, F. (2002a). EMDR 12 years after its introduction: Past and future research. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.1126

EMDR 12 years after its introduction: Past and future research. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.1126

Shapiro, F. (2002b). EMDR and the role of the clinician in psychotherapy evaluation: Towards a more comprehensive integration of science and practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(12), 1453-1463. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10104

Shapiro, F. (2007). EMDR, adaptive information processing, and case conceptualization. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 1(2), 68-87. Open access: https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.1.2.68

Shapiro, F. (2012). EMDR therapy: An overview of current and future research. Revue Europeenne de Psychologie Appliquee/European Review of Applied Psychology 62(4), 193-195. Open access: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2012.09.005

Shapiro, F. (2013). The case: Treating Jared through eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(5), 494-496. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21986

Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(5), 494-496. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21986

Shapiro, F. (2014a). The role of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in medicine: Addressing the psychological and physical symptoms stemming from adverse life experiences. The Permanente Journal, 18(1), 71-77. Open access: https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/13-098

Shapiro, F. (2014b). EMDR therapy humanitarian assistance programs: Treating the psychological, physical, and societal effects of adverse experiences worldwide. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 8(4), 181-186. Open access: http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.8.4.181

_______________________________________________________________________

Peer-Reviewed Research Articles, Co-Author:Brown, S., & Shapiro, F. (2006). EMDR in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Clinical Case Studies 5(5), 403-420. Open access: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1534650104271773

Open access: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1534650104271773

Landin-Romero, R., Novo, P., Vicens, V., McKenna, P. J., Santed, A., Pomarol-Clotet, E., Salgado-Pineda, P., Shapiro, F., & Amann, B. L. (2013). EMDR therapy modulates the default mode network in a subsyndromal, traumatized bipolar patient. Neuropsychobiology, 67(3), 181-184. https://doi.org/10.1159/000346654

Luber, M., & Shapiro, F. (2009). Interview with Francine Shapiro: Historical overview, present issues, and future directions of EMDR. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 3(4), 217-231. Open access: https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.3.4.217

Madrid, A., Skolek, S., & Shapiro, F. (2006). Repairing failures in bonding through EMDR. Clinical Case Studies, 5(4), 271-286. Open access: https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650104267403

Novo, P., Landin-Romero, R., Radua, J., Vicens, V., Fernandez, I., Garcia, F., Pomarol-Clotet, E. , McKenna, P. J., Shapiro, F., & Amann, B. L. (2014). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy in subsyndromal bipolar patients with a history of traumatic events: A randomized, controlled pilot-study. Psychiatry Research, 219(1), 122-128. Open access: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165178114003837?via%3Dihub

, McKenna, P. J., Shapiro, F., & Amann, B. L. (2014). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy in subsyndromal bipolar patients with a history of traumatic events: A randomized, controlled pilot-study. Psychiatry Research, 219(1), 122-128. Open access: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165178114003837?via%3Dihub

Ricci, R. J., Clayton, C. A., & Shapiro, F. (2006). Some effects of EMDR treatment with previously abused child molesters: Theoretical reviews and preliminary findings. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 17(4), 538-562. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14789940601070431

Schneider, J., Hofmann, A., Rost, C., & Shapiro, F. (2007). EMDR and phantom limb pain: Theoretical implications, case study, and treatment guidelines. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 1(1), 31-45. Open access: https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.1.1.31

Schneider, J., Hofmann, A., Rost, C. , & Shapiro, F. (2008). EMDR in the treatment of chronic phantom limb pain. Pain Medicine, 9(1), 76-82. Open access: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00299.x

, & Shapiro, F. (2008). EMDR in the treatment of chronic phantom limb pain. Pain Medicine, 9(1), 76-82. Open access: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00299.x

Shapiro, F., & Laliotis, D. (2011). EMDR and the adaptive information processing model: Integrative treatment and case conceptualization. Clinical Social Work Journal, 39(1), 191-200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-010-0300-7

Shapiro, F., Vogelmann-Sine, S., & Sine, L. F. (1994). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Treating trauma and substance abuse. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 26(4), 379-391. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.1994.10472458

Solomon, R. M., & Shapiro, F. (2008). EMDR and the Adaptive Information Processing model: Potential mechanisms of change. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 2(4). Open access: https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.2.4.315

Zabukovec, J., Lazrove, S., & Shapiro, F. (2000). Self-healing aspects of EMDR: The therapeutic change process and perspectives of integrated psychotherapies. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 10(2), 189-206. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009400317083

(2000). Self-healing aspects of EMDR: The therapeutic change process and perspectives of integrated psychotherapies. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 10(2), 189-206. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009400317083

_______________________________________________________________________

Video:National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine. (2013, April 12). Treating trauma with EMDR: Healing from our nightmares. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S2BhZwHXFro (4 min)

The Psychology Webinar Group. (2014, February 6). Francine Shapiro Ph.D. EMDR Webinar “The Past is Present” [Video PPT presentation]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsQbzfW9txc&feature=youtu.be (58 min)

VEN EMDR. (2014, July 25). EMDR interview Francine Shapiro [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8GUd5hhnkVE (44 min)

_______________________________________________________________________

Podcast/Audio:Brit, M. (Host). (2011, March 19). Episode 143: EMDR – An Interview with Founder Francine Shapiro [Audio podcast episode]. In The Psych Files. Audioboom. https://audioboom.com/posts/5153445-episode-143-emdr-an-interview-with-founder-francine-shapiro (22 min)

(Host). (2011, March 19). Episode 143: EMDR – An Interview with Founder Francine Shapiro [Audio podcast episode]. In The Psych Files. Audioboom. https://audioboom.com/posts/5153445-episode-143-emdr-an-interview-with-founder-francine-shapiro (22 min)

Robinson, J. (Host). (2014, July 18). Get past your past with EMDR eye movement desensitization and reprocessing & Francine Shapiro, Ph.D. In Get Real Radio: Empowering Lasting Transformation. Voice America [Audio podcast episode]. https://www.voiceamerica.com/episode/79155/get-past-your-past-with-emdr-eye-movement-desensitization-and-reprocessing-and-francine-shapiro-phd (56 min)

Take Care staff. (2015, February 1). Don’t overthink it: letting your brain work through trauma with EMDR. Take Care on WRVO Public Media [Audio interview with Francine Shapiro]. https://www.wrvo.org/post/dont-overthink-it-letting-your-brain-work-through-trauma-emdr (13 min)

_______________________________________________________________________

Obituaries:Carey, B. (2019, July 11). Francine Shapiro, developer of eye-movement therapy, dies at 71. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/11/science/francine-shapiro-dead.html

(2019, July 11). Francine Shapiro, developer of eye-movement therapy, dies at 71. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/11/science/francine-shapiro-dead.html

EMDR International Association. (2019, September). In memory of Francine Shapiro. Go With That, 24(3), 5-11. https://www.emdria.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/GWT.2019.24.3.In_.Memory.of_.Francine.Shapiro..pdf

Savage, J., & Sundwall, M. (Hosts). (2019, July 30). Episode 9: Remembering Francine Shapiro [Audio podcast episode]. In Notice That. http://emdr-podcast.com/episode-9-remembering-francine-shapiro/

Solomon, R., & Maxfield, L. (2019). Obituary: Francine Shapiro. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 13(3), 158-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.13.3.158

Warren, P. (2019, June 15). Francine Shapiro obituary. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/jul/15/francine-shapiro-obituary

_______________________________________________________________________

Online Articles:Bilanow, T. (2012, February 27). Ask an expert about E.M.D.R. The New York Times. https://consults.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/02/27/ask-an-expert-about-e-m-d-r/

(2012, February 27). Ask an expert about E.M.D.R. The New York Times. https://consults.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/02/27/ask-an-expert-about-e-m-d-r/

Careers in Psychology. (2012). Dr. Francine Shapiro: EMDR Psychologist [interview transcript]. https://careersinpsychology.org/interview/dr-francine-shapiro/

Shapiro, F. (n.d.). Clinician’s corner: EMDR therapy. International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Stress Points. http://sherwood-istss.informz.net/admin31/content/template.asp?sid=48003&brandid=4463&uid=1019027291&mi=5471628&mfqid=26491997&ptid=0&ps=48003

Shapiro, F. (2012, January 27). Baby boomers and distant dads. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ptsd-veterans_b_1228542

Shapiro, F. (2012, February 5). How memories keep us apart: The past is present. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ptsd-military_b_1250202

Shapiro, F. (2012, February 19). Why our unconscious rules us and what to do about it. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ptsd-veterans_b_1284642?ref=healthy-living

Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ptsd-veterans_b_1284642?ref=healthy-living

Shapiro, F. (2012, February 27). EMDR therapy and getting past your past. Good Therapy. https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/emdr-therapy-your-past-0227126/

Shapiro, F. (2012, February 28). The many faces of fear and how to deal with them. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ptsd-fear_b_1299786

Shapiro, F. (2012, March 2). The evidence on E.M.D.R. The New York Times: Consults. https://consults.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/02/the-evidence-on-e-m-d-r/

Shapiro, F. (2012, March 16). Expert answers on E.M.D.R. The New York Times: Consults. https://consults.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/16/expert-answers-on-e-m-d-r/

Shapiro, F. (2012, June 13). How to take back your power after a divorce. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/how-to-take-back-your-pow_b_1582534?guccounter=1

Shapiro, F. (2012, August 29). Helping you and your children make it through divorce. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/helping-you-and-your-chil_b_1837948?utm_hp_ref=divorce-advice

(2012, August 29). Helping you and your children make it through divorce. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/helping-you-and-your-chil_b_1837948?utm_hp_ref=divorce-advice

Shapiro, F. (2012, Spring). How EMDR therapy opens a window to the brain. BrainWorld. https://brainworldmagazine.com/how-emdr-therapy-opens-a-window-to-the-brain/

Soderlund, J. (2000, Sep/Oct). Integral EMDR: An interview with Francine Shapiro. New Therapist Magazine, 9, 18-22. http://www.newtherapist.com/shapiro9.html

Tartakovsky, M. (2016, May 17). Using EMDR therapy to heal your past: Interview with creator Francine Shapiro. PsychCentral. https://psychcentral.com/lib/using-emdr-therapy-to-heal-your-past-interview-with-creator-francine-shapiro#1

Wetherford, R. (2014). Francine Shapiro on the evolution of EMDR therapy. Psychotherapy.net. https://www.psychotherapy.net/interview/francine-shapiro-emdr

_______________________________________________________________________

Books/Book Chapters:Adler-Tapia, R. , Settle, C., & Shapiro, F. (2011). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) psychotherapy with children who have experienced sexual abuse and trauma. In P. Goodyear-Brown (Ed.), Handbook of child sexual abuse: Identification, assessment, and treatment. New York, NY: Wiley Publishing.

, Settle, C., & Shapiro, F. (2011). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) psychotherapy with children who have experienced sexual abuse and trauma. In P. Goodyear-Brown (Ed.), Handbook of child sexual abuse: Identification, assessment, and treatment. New York, NY: Wiley Publishing.

Lake, K., & Shapiro, F. (2005). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. In M. Hersen (Ed.), Encyclopedia of behavior modification and cognitive behavior therapy, Vol. 1: Adult clinical application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

Laliotis, D., & Shapiro, F. (2022). EMDR therapy for trauma-related disorders. In U. Schnyder & M. Cloitre (Eds.), Evidence based treatments for trauma-related psychological disorders: A practical guide for clinicians, second edition. Cham, Switzerland, Springer Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97802-0_11

Rosenthal, H. (2006). An encounter with EMDR pioneer Francine Shapiro: The eyes have it. In (Author) Therapy’s best: Practical advice and gems of wisdom from twenty accomplished counselors and therapists. New York, NY: Routledge

In (Author) Therapy’s best: Practical advice and gems of wisdom from twenty accomplished counselors and therapists. New York, NY: Routledge

Shapiro, F. (1994). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: A new treatment for anxiety and related trauma. In L. Hyer (Ed.), Trauma victim: Theoretical and practical suggestions (pp. 501-523). Muncie, IN: Accelerated Development.

Shapiro, F. (1997). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Research and clinical significance. In W. J. Matthews & Edgette, J. H. (Eds.), Current thinking and research in brief therapy: Solutions, strategies, narratives (Vol 1, pp .239-260). New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel, Inc.

Shapiro, F. (1998). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): Historical context, recent research, and future directions. In L. VandeCreek & S. Knapp (Eds.), Innovations in clinical practice: A source book (Vol 16, pp. 143-162). Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press Inc.

Shapiro, F. (2001). Trauma and adaptive information processing: EMDR’s dynamic and behavioral interface. In M. F. Solomon, R. J. Neborsky, L., McCullough, M. Alpert, F. Shapiro, and D. M. David (Eds.), Short-term therapy for long-term change. (pp.112-129). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co

Shapiro, F. (Ed.). (2002). EMDR as an integrative psychotherapy approach: Experts of diverse orientations explore the paradigm prism. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Shapiro, F. (2012). Getting past your past: Take control of your life with self-help techniques from EMDR therapy. New York: NY, Rodale.

Shapiro, F. (2013). Redefining trauma and its hidden connections: Identifying and reprocessing the experiential contributors to a wide variety of disorders. In D. J. Siegel and M. Solomon (Eds.), Healing moments in psychotherapy (pp. 89-114). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co.

Shapiro, F. (2018, 2001, 1995). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures (3rd ed. ). New York, NY: The Guilford Press

). New York, NY: The Guilford Press

Shapiro, F., Kaslow, F. W., Maxfield, L. (2007). Handbook of EMDR and family therapy processes. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. Inc

Shapiro, F., & Forrest, M. S. (2016, 2004, 1997). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: The breakthrough “Eye Movement” therapy for overcoming anxiety, stress, and trauma (3rd ed.) New York, NY: Basic Books.

Shapiro, F., & Laliotis, D. (2015). EMDR therapy for trauma-related disorders. In U. Schnyder & M. Cloitre (Eds.), Evidence based treatments for trauma-related psychological disorders: A practical guide for clinicians (pp. 205-228). New York, NY: Springer.

Shapiro, F., Snyker, E., & Maxfield, L. (2004). EMDR: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. In F. W. Kaslow & T. Patterson (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral approaches (pp. 248-254). West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Shapiro, F., & Solomon, R. (1995). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Neurocognitive information processing. In G. S. Everley (Ed.), Innovations in disaster and trauma psychology: Applications in emergency services and disaster response (pp. 216-237). Elliot City, MD: Chevron Publishing.

Shapiro, F., & Solomon, R. (2010). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy. In I. B. Weiner & W. E. Craighead (Eds.), The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology, (4th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 629-632). Hoboken, NY: Wiley.

Shapiro, F., & Solomon, R. (2017). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy. In S. N. Gold, J. M. Cook, & C. J. Dalenberg (Eds.), Handbook of trauma psychology: Vol 2. Trauma practice. Washington, D. C. The American Psychological Association.

Shapiro, F., Wesselmann, D., & Mevissen, L. (2017). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (EMDR). In M.A. Landolt, M. Cloitre, & U. Schnyder (Eds.), Evidence based treatments for trauma-related disorders in children and adolescents (pp. 273-298). New York, NY: Springer.

Cloitre, & U. Schnyder (Eds.), Evidence based treatments for trauma-related disorders in children and adolescents (pp. 273-298). New York, NY: Springer.

Solomon, R. M., & Shapiro, F. (1997). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: A therapeutic tool for trauma and grief. In C. R. Figley & B. E. Bride (Eds.), Death and trauma: The traumatology of grieving. The series in trauma and loss (pp. 231-247). Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis.

Wesselmann, D., & Shapiro, F. (2013). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. In J. Ford & C. Courtois (Eds.). Treating complex traumatic stress disorders in children and adolescents (pp. 203-224). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

EMDR THERAPY: A Review of Development and Mechanisms of Action

Udy Oren, Roger Solomon

This article presents the history and development of EMDR from the original discovery of Dr. Francine Shapiro in 1987 to current results, as well as future directions for research and clinical practice. . EMDR is an integral psychotherapy that considers dysfunctionally stored memories as a core element in the development of psychopathology.

. EMDR is an integral psychotherapy that considers dysfunctionally stored memories as a core element in the development of psychopathology.

Key words: psychotherapy method, EMDR, eye movement desensitization and processing, effective psychotherapy.

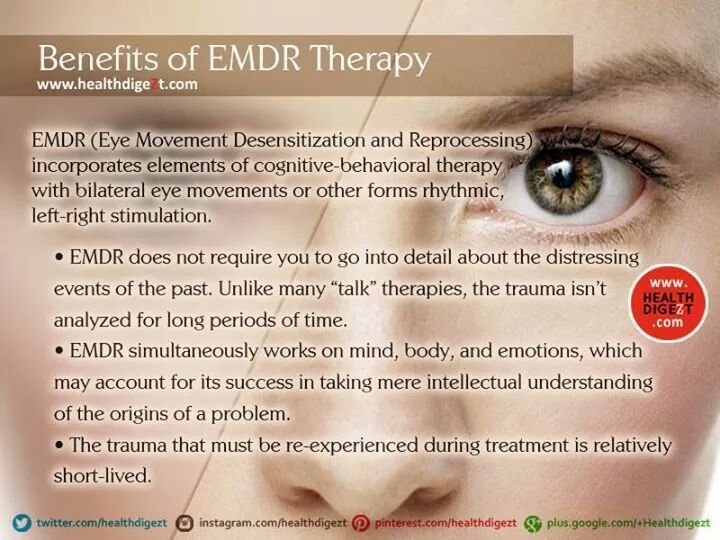

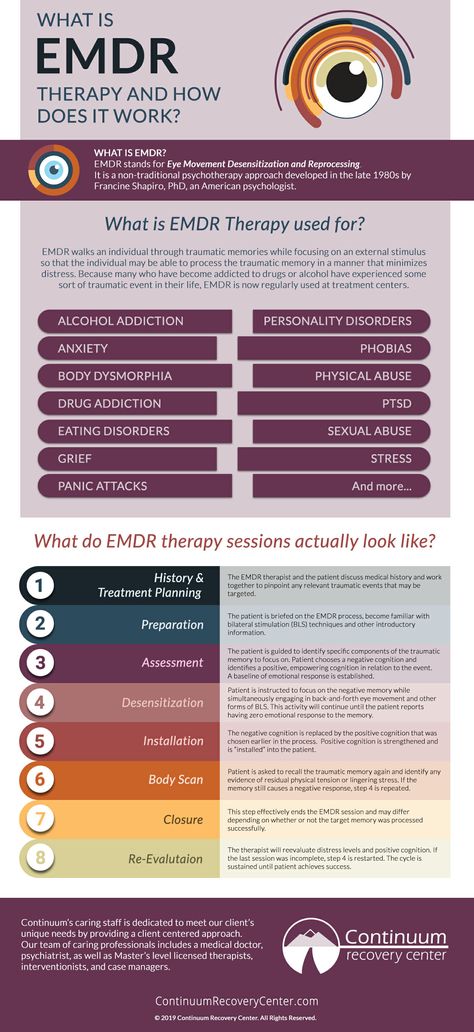

Eye Movement Densitization and Processing (EMDR) is a therapeutic approach based on the Adaptive Information Processing (API) model. From the point of view of this integrative psychotherapeutic approach, dysfunctionally stored memories are considered to be the primary basis of clinical pathology. Processing these memories and integrating them into larger adaptive networks of memories allows them to be transformed and the system to function again.

Over the past 25 years, enough clinical research has been conducted on EMDR therapy to lead to widespread acceptance of this approach as an effective treatment for psychic trauma. The history of therapy, the API model, clinical application and elements of the procedure itself are described in various literature (European EMDR Association: http://www. emdr-europe.org/), which also describes studies confirming two main theories explaining the mechanisms of action of bilateral stimulation (BLS) used during EMDR therapy.

emdr-europe.org/), which also describes studies confirming two main theories explaining the mechanisms of action of bilateral stimulation (BLS) used during EMDR therapy.

EMDR is an integrative psychotherapeutic approach whose procedural elements fit well with most other types of psychotherapy (F. Shapiro, 2001, 2002). The therapy is based on the API model, which emphasizes the role of our brain's information processing system in the development of both healthy human functioning and pathology. Within the IPA model, insufficiently processed memories of uncomfortable or traumatic experiences are considered as the primary source of any psychopathology not caused by organic disorders. The processing of these memories leads to a resolution of the problem by rebuilding the system and assimilating the memory data into larger adaptive memory networks. EMDR is an 8-phase therapy that includes a three-part protocol focusing on:

- memories behind current problems;

– situations in the present and triggers that need to be dealt with separately in order to bring the client into a stable state of psychological health;

- as well as the integration of positive memory scripts for more adaptive behavior in the future.

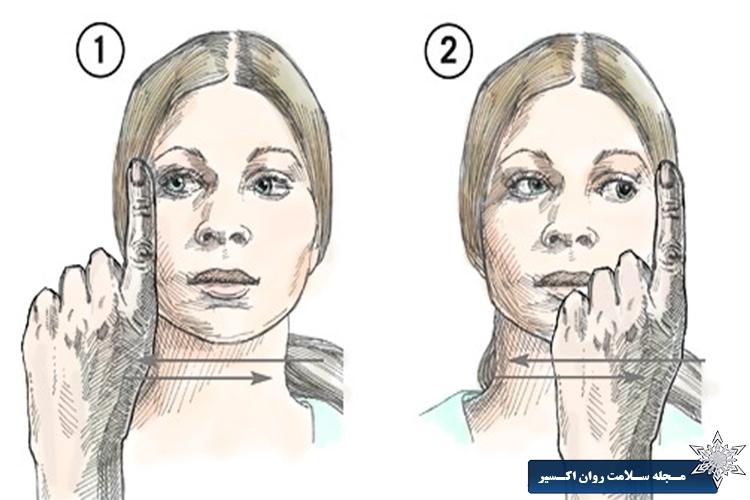

One of the distinguishing features of EMDR is the use of bilateral stimulation, in particular side-to-side eye movements, alternating knee tapping, or alternating auditory stimulation, using standardized procedures and protocols to work with all aspects of the target memory network.

History of occurrence.

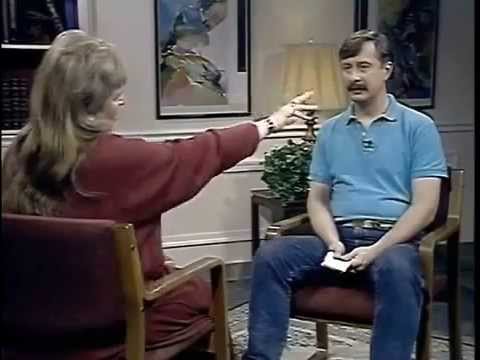

The history of EMDR began in 1987 when F. Shapiro discovered the effects of eye movements on disturbing memories. Based on this, she developed a therapy protocol she called Eye Movement Desensitization (EMD). Since initially F. Shapiro adhered to behavioral views, she first decided that the effect of eye movements was similar to systematic desensitization, and decided that it was based on the body's natural relaxation reaction.

She also suggested that the EMD process is related to the phenomenon of REM sleep and its effects on humans.

Shapiro's first studies were randomized clinical trials and showed promising results in the treatment of victims of sexual violence and war veterans (Shapiro, 1989).

Shapiro continued to develop and improve EMD procedures beyond the behavioral paradigm and in 1991 changed the name of the therapy to EMDR. The decision to add the word "processing" was due to the realization that desensitization is only one of the results of therapy, in fact, has a deeper effect, which can be better understood from the theory of information processing.

Early 1990s EMDR is experiencing a period of rapid growth and, at the same time, fierce discussions. The support of Joseph Wolpe, author of the method of systematic desensitization, as well as the publication of the results of several studies (Marquis, 1991; Wolpe & Abrams, 1991) led to the assertion that EMDR is a very promising form of psychotherapy. On the other hand, opponents of EMDR questioned the role of eye movements themselves (Lohr et al., 1992) and saw no scientific reason to add them to what they considered to be a type of exposure therapy (McNally, 1999). This criticism was recognized as erroneous (see review in Perkins & Rouanzoin, 2002), but the presence of opponents did not prevent F. Shapiro and her colleagues from continuing their work and conducting additional research. As empirical data was collected, EMDR therapy training programs began throughout the US, as well as in Europe, Australia, and Central and South America.

Shapiro and her colleagues from continuing their work and conducting additional research. As empirical data was collected, EMDR therapy training programs began throughout the US, as well as in Europe, Australia, and Central and South America.

The faculty of the EMDR Institute (www.emdr.com) have made a commitment from the very beginning to provide philanthropic education in hot spots and disaster areas around the world. At 1995 after the Oklahoma bombing, the EMDR community responded by creating the EMDR Humanitarian Assistance Program (EMDR-HAP).

The EMDR-HAP Program (www.emdrhap.org) and its affiliates around the world have continued to run hundreds of charity trainings in areas such as war-torn Bosnia, Nicaragua, Northern Ireland, Mexico City, post-quake Istanbul, Southeast Asia after the tsunami, in Israel, Palestine, Haiti after the earthquake, and at the request of many US government agencies.

Since 1995, when the first EMDR association (www.emdria.org) was founded in the USA, many other state and regional associations have appeared, including EMDR Asia (www. emdr-asia.org), EMDR Ibero-America (www.emdria.org). .emdriberoamerica.org), as well as the EMDR Europe Association (www.emdreurope.org), which has over 20 national associations and over 8,000 members (24,000 members in 2017. editor's note).

emdr-asia.org), EMDR Ibero-America (www.emdria.org). .emdriberoamerica.org), as well as the EMDR Europe Association (www.emdreurope.org), which has over 20 national associations and over 8,000 members (24,000 members in 2017. editor's note).

Due to the large amount of empirical research accumulated over the past 20 years, EMDR therapy is recognized as an effective therapy for trauma and is included in the clinical guidelines of many professional organizations and recommended by the ministries of health in different countries. In Europe, these include the Clinical Resource Efficiency Support Committee of the Department of Health Northern Ireland (CREST, 2003), the Guidance for the Delivery of Mental Health Services of the National Committee of the Netherlands (2003), the Study of the French State Institute of Medicine and Health (INSERM, 2004), UK Government Collaborating Center for Mental Health (NICE, 2005), Swedish Council for Technology Evaluation (2001), and UK Department of Health. In the United States, such organizations include the American Psychiatric Association (2004), the American Psychological Association (Chambles et al., 1998), State Institute of Mental Health (2007), and Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (2004). EMDR is also included in the recommendations of the International Traumatic Stress Society (ISTSS) (Foa, Keane & Friedman, 2009) (http://www.emdreurope.org/info.asp?CategoryID=15).

In the United States, such organizations include the American Psychiatric Association (2004), the American Psychological Association (Chambles et al., 1998), State Institute of Mental Health (2007), and Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (2004). EMDR is also included in the recommendations of the International Traumatic Stress Society (ISTSS) (Foa, Keane & Friedman, 2009) (http://www.emdreurope.org/info.asp?CategoryID=15).

Clinical studies.

Numerous practice guidelines and meta-analyses (Bisson & Andrew, 2007) show that EMDR has a therapeutic effect that is equal in strength and duration to that of the most extensively studied CBT techniques. The results of about 20 controlled studies have confirmed the effectiveness of EMDR therapy: for the treatment of PTSD; in the treatment of a wide range of disorders, including phobias (de Jongh, Ten Broeke & Renssen, 1999; de Jongh, van den Oord & Ten Broeke, 2002), panic disorder (Goldstein et al., 2000; Fernandez & Faretta, 2007), generalized anxiety disorder (Gauvreau & Bouchard, 2008), problems with self-control and self-esteem (Soberman, Greenwald & Rule, 2002), complicated cases of mourning (Solomon & Rando, 2007), dysmorphia (Brown, McGoldrick & Buchanan, 1997), olfactory disorder syndrome (McGoldrick, Begum & Brown, 2008), sexual dysfunction (Wernik, 1993), pedophilia (Ricci et al. , 2006), fear of failure (Barker & Barker, 2007), chronic pain (Grant & Threlfo, 2002), migraines (Marcus, 2008), and phantom pain in amputees (Schneider et al., 2008; Tinker & Wilson, 2006; de Roos, Veenstra et al., 2010). Most studies evaluate the effectiveness of EDMR with adults, however, there are several studies showing unusually positive results with children (Greenwald, 1998; Ahmad & SundelinWahlsten, 2008; Chemtob, Nakashima & Carlson, 2002; de Roos & de Jongh, 2008; Jaberghaderi, Greenwald, Rubin, Dolatabadim & Zand, 2004).

, 2006), fear of failure (Barker & Barker, 2007), chronic pain (Grant & Threlfo, 2002), migraines (Marcus, 2008), and phantom pain in amputees (Schneider et al., 2008; Tinker & Wilson, 2006; de Roos, Veenstra et al., 2010). Most studies evaluate the effectiveness of EDMR with adults, however, there are several studies showing unusually positive results with children (Greenwald, 1998; Ahmad & SundelinWahlsten, 2008; Chemtob, Nakashima & Carlson, 2002; de Roos & de Jongh, 2008; Jaberghaderi, Greenwald, Rubin, Dolatabadim & Zand, 2004).

When looking at the results of studies comparing the effectiveness of EMDR and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), it is important to remember that EMDR therapy does not require the 30 to 100 hours of homework that most forms of cognitive behavioral therapy do. However, with EMDR it is possible to achieve the same therapeutic effect with less psychological trauma to the client, as well as by working exclusively in sessions. As a result, the therapy is gentler, more tolerable by both clients and therapists (Arabia, Manca & Solomon, 2011), and is also able to produce positive results when sessions are carried out over several days in a row (Wesson & Gould, 2009).

One of the elements of EMDR, bilateral stimulation, has attracted the most attention from both clinicians and scientists. Several theories have been put forward to explain the action of BLS, but the mechanisms of action are still being studied. An early component analytic study assessing the role of eye movements produced conflicting results. However, critics have found a flaw in this study due to the use of an incorrectly selected patient group and insufficient duration of therapy (Chemtob, Tolin, van der Kolk & Pitman, 2000). On the other hand, specific physiological effects of eye movement during EMDR therapy sessions have been identified (Propper et al., 2007; Elofsson, von Scheele, Theorell & Sondergaard, 2008; Sack, Lempa, Steinmetz, Lamprecht & Hofmann, 2008; Wilson , Silver, Covi & Foster, 1996). Scientists believe that eye movements lead to an increase in parasympathetic activity and a decrease in psychophysiological arousal. Similar physiological results were obtained in a study where a patient experienced a decrease in pulse rate and galvanic skin reflex after one session of EMDR (Aubert-Khalfa, Roques & Blin, 2008).

Two theories enjoy the greatest support from scientists. One concerns the orienting reflex, which, in their opinion, is directly related to the processes that take place during REM sleep (Stickgold, 2002, 2008). This theory is also supported by those randomized studies in which it was found that eye movements improve the functioning of event memory (Christman, Garvey, Propper & Phaneuf, 2003), increase the flexibility of attention focus (Kuiken, Bears, Miall & Smith, 2002; Kuiken, Chudleigh & Racher, 2010) and enhance the ability to recognize true information (Parker & Dagnall, 2007; Parker, Relph & Dagnall, 2008; Parker, Buckley & Dagnall, 2009). The orienting reflex hypothesis has also been evaluated in studies showing decreased levels of arousal (MacCulloch & Feldman, 1996; Barrowcliff, Gray, MacCulloch, Freeman & MacCulloch, 2003; Barrowcliff, Gray, Freeman & MacCulloch, 2004; Schubert, Lee & Drummond, 2011).

The second dominant hypothesis is that eye movements and other forms of dual focus stimulation (such as tapping and auditory stimulation) disrupt the habitual functioning of short-term memory. Randomized trials of this theory show that eye movements reduce the saturation and/or emotional charge of memories and frightening images (Andrade, Kavanagh & Baddeley, 1997; Engelhard, van Uijen & van den Hout, 2010; Engelhard et al., 2011; Gunter & Bodner, 2008; Kavanagh, Freese, Andrade & May, 2001; Maxfield, Melnyk & Hayman, 2008; Sharpley, Montgomery & Scalzo, 1996; van den Hout, Muris, Salemink & Kindt, 2001; van den Hout et al., 2011). At the moment, it is not known when exactly the change in saturation and emotional charge occurs - before or after the decrease in physiological arousal, whether these two phenomena are closely related or whether they represent independent elements of the process (Sack et al., 2007, 2008a, b).

Randomized trials of this theory show that eye movements reduce the saturation and/or emotional charge of memories and frightening images (Andrade, Kavanagh & Baddeley, 1997; Engelhard, van Uijen & van den Hout, 2010; Engelhard et al., 2011; Gunter & Bodner, 2008; Kavanagh, Freese, Andrade & May, 2001; Maxfield, Melnyk & Hayman, 2008; Sharpley, Montgomery & Scalzo, 1996; van den Hout, Muris, Salemink & Kindt, 2001; van den Hout et al., 2011). At the moment, it is not known when exactly the change in saturation and emotional charge occurs - before or after the decrease in physiological arousal, whether these two phenomena are closely related or whether they represent independent elements of the process (Sack et al., 2007, 2008a, b).

Ten randomized trials support both hypotheses. Therefore, there is good reason to believe that both theories are correct and that both processes described contribute to the therapeutic effect of EMDR. All of these findings collectively tell us that while previous component analyzes have failed to confirm the importance of bilateral pacing for EMDR, there is little doubt that the next generation of component analyzes of diagnosed patients will add to our knowledge base—provided, of course, that they are done well. research work (F. Shapiro, 2001).

research work (F. Shapiro, 2001).

Model of adaptive information processing (API).

Behind the transformation of EMD into EMDR was primarily the API model, which is the theoretical basis for the entire clinical practice of EMDR (F. Shapiro, 1995, 2001). According to this model, networks of memories that store all previous experience are the basis for both human health and the emergence of pathology. New experience is an endless stream of conscious and unconscious elements of information that are processed by the brain with the help of an information processing system within these networks of memories. This system is inherently adaptive in that it is capable of using information to support human growth and development through learning when it functions normally. Relevant sensory, cognitive, emotional and somatic information is stored in memory networks, which in the future will be used to enable a person to adaptively respond to the world around him.

Apparently, some stressful negative events lead to an overload of the information processing system, as a result of which they cannot be assimilated adaptively. Such an event is stored in memory along with disturbing emotions, physical sensations and fears experienced at the time of the event. These situations can sometimes represent serious traumas, but more often they are everyday negative events that happen to people at home, in relationships, at school, at work, and so on, such as humiliation, rejection, and failure. In such situations, information regarding the negative event is stored in isolation from adaptive memory networks. Current situations in the present may trigger earlier memories, whereby the individual may experience some or all of the sensory, cognitive, emotional, and somatic aspects of events, resulting in maladaptive or symptomatic behavior.

Such an event is stored in memory along with disturbing emotions, physical sensations and fears experienced at the time of the event. These situations can sometimes represent serious traumas, but more often they are everyday negative events that happen to people at home, in relationships, at school, at work, and so on, such as humiliation, rejection, and failure. In such situations, information regarding the negative event is stored in isolation from adaptive memory networks. Current situations in the present may trigger earlier memories, whereby the individual may experience some or all of the sensory, cognitive, emotional, and somatic aspects of events, resulting in maladaptive or symptomatic behavior.

The API model considers negative beliefs, behaviors, and personality traits as a consequence of dysfunctionally stored memories (F. Shapiro, 2001). From this point of view, any negative self-belief (e.g., "I'm stupid"), any negative emotional reaction (e.g., fear in the presence of an authority figure), any negative somatic reaction (e. g., abdominal pain before an exam) are symptoms rather than the cause of current problems. The reason is considered to be memories of unprocessed events from the patient's life that are activated in the present. This view of psychological pathology is the main theoretical basis of EMDR therapy and helps the clinician understand the client, formulate a treatment plan, and select appropriate therapeutic interventions.

g., abdominal pain before an exam) are symptoms rather than the cause of current problems. The reason is considered to be memories of unprocessed events from the patient's life that are activated in the present. This view of psychological pathology is the main theoretical basis of EMDR therapy and helps the clinician understand the client, formulate a treatment plan, and select appropriate therapeutic interventions.

During an EMDR session, standardized procedures and protocols are used to access the memory associated with the current difficulty, which also uses brief bilateral stimulation (eye movements, tactile and auditory stimulation). Recordings of sessions (F. Shapiro, 2001, 2002; Shapiro & Forrest, 1997) show that processing mainly occurs due to the rapid establishment of intrapsychic connections between emotions, insights, sensations and memories that arise during the session, which change after each next set of bilateral stimulation. According to the API model, this process is seen as establishing a connection between the target memory and adaptive information, which allows the client to move forward, passing through the necessary stages of affect and awareness related to topics such as (1) the right degree of responsibility, (2) safety in present moment, and (3) the possibility of making choices in the future.

EMDR processing is understood as an inducement to the emergence of new associations and connections, which makes further learning possible and leads to the preservation of memories in a new, adaptive form. Once this has happened, the client can look at the disturbing event and at himself from a new, adaptive perspective. This new point of view does not carry the negative cognitions, affect and somatic sensations that were previously at the center of his maladaptive perception of this event. Consequently, the event ceases to have a negative impact on the client's personality, his worldview, as well as his emotional and somatic experience. This reworking, leading to new learning, is a central element of the EMDR model and therapy. The three-part protocol used in EMDR therapy works and recycles the positive experiences and new information/education needed to overcome any lack of knowledge or skills.

8-phase therapeutic approach.

EMDR Integrative Psychotherapy uses an 8-phase protocol to guide the therapist in dealing with current psychological difficulties stemming from past negative events.

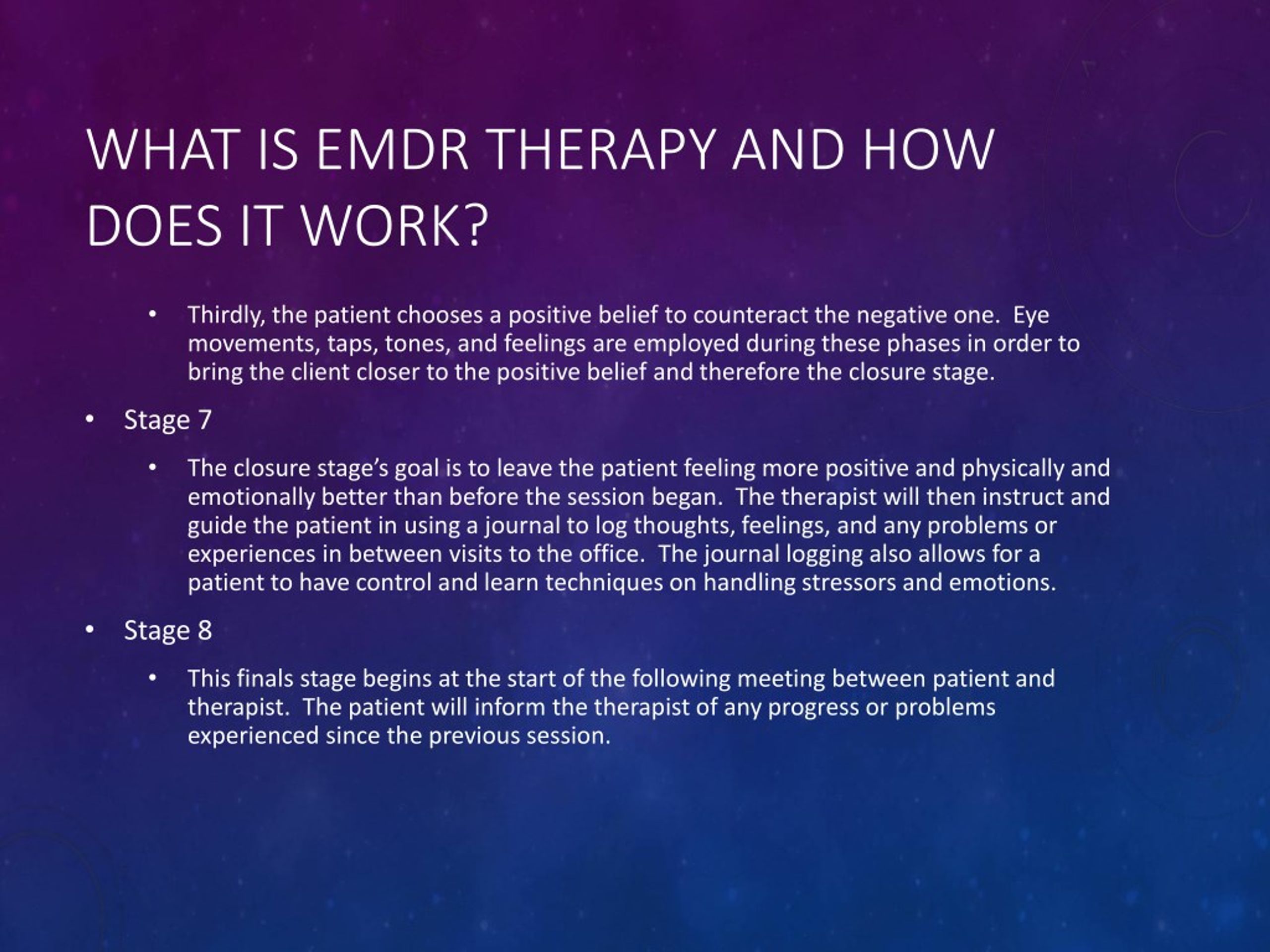

Phase 1 - History taking. The therapist collects general psychological data, focusing on current strengths and difficulties, past events that are related to current problems, present situations that cause problems, and positive goals for the future.

Phase 2 - Preparation. The therapist prepares the client for reprocessing by establishing a therapeutic alliance, providing psychological preparation for the client's difficulties, as well as explaining the EMDR process, and teaching the client specific types of relaxation techniques to help the client maintain a "dual focus" during a series of reprocessing sessions.

Phase 3 – Evaluation. The therapist will help the client clarify the details of the target memory, including the central picture, current negative cognition, desired positive cognition, current emotions and physical sensations, and some basic scale measurements.

Phase 4 - Desensitization. The therapist follows the client in guiding the processing of a disturbing memory from a past or current target event. At a later stage, positive scenarios for future behavior are also processed. Processing includes changes in sensory, cognitive, emotional and somatic information. The purpose of this phase is to reduce the anxiety associated with the memory to the lowest possible level and to promote personal growth through gaining insight and new perspectives, resulting in a new sense of self and worldview.

At a later stage, positive scenarios for future behavior are also processed. Processing includes changes in sensory, cognitive, emotional and somatic information. The purpose of this phase is to reduce the anxiety associated with the memory to the lowest possible level and to promote personal growth through gaining insight and new perspectives, resulting in a new sense of self and worldview.

Phase 5 - Installation. The therapist helps the client identify the currently desired positive self-belief about the processed memory and reinforces it, facilitating the integration of the memory into adaptive memory networks.

Phase 6 - Body scan. The therapist helps the client to discover and process any residual somatic sensations, striving for a complete somatic resolution.

Phase 7 - Completion. The therapist gives the client feedback about the session and what to expect after the session is over. The client is asked to keep brief notes of psychological reactions between sessions. If necessary, the therapist may use relaxation techniques to help the client stabilize before the session ends.

If necessary, the therapist may use relaxation techniques to help the client stabilize before the session ends.

Phase 8 - Reassessment. The therapist evaluates the client at the start of the next session, paying special attention to the effect of the therapy and assessing what has happened between sessions. This step also includes a re-evaluation of the previously redesigned target to assess the persistence of the therapy effect, as well as to identify other aspects that potentially need further processing. The therapist uses this information to determine the next step(s) in the course of therapy.

Three-part protocol (past, present, future).

Upon completion of therapy planning (Phase 1) and preparation and stabilization (Phase 3), EMDR therapy includes a three-part protocol that addresses past, present, and future relevant memories/scripts. In this approach, the therapist helps the client identify the details of each memory/script (phase 3) and process it (phases 4, 5, 6). Based on the API model, the client is first asked to process past experiences (both earlier and more recent) related to current difficulties. Reprocessing then focuses on current situations that are causing maladaptive responses in the present (including negative thoughts, emotions, feelings, and behaviors). Once memories from the past and present have been processed, the client is asked to imagine adaptive behaviors that will be used as a memory script for the future. This is done in relation to each of the previously identified situations in the present that cause dysfunctional reactions. Then the scenarios, which include cognitive, somatic and behavioral information, are processed, which contributes to their integration into the adaptive network of memories. The client may then be asked to face a particular problematic situation and then provide the therapist with feedback that will help him decide whether to continue therapy.

Based on the API model, the client is first asked to process past experiences (both earlier and more recent) related to current difficulties. Reprocessing then focuses on current situations that are causing maladaptive responses in the present (including negative thoughts, emotions, feelings, and behaviors). Once memories from the past and present have been processed, the client is asked to imagine adaptive behaviors that will be used as a memory script for the future. This is done in relation to each of the previously identified situations in the present that cause dysfunctional reactions. Then the scenarios, which include cognitive, somatic and behavioral information, are processed, which contributes to their integration into the adaptive network of memories. The client may then be asked to face a particular problematic situation and then provide the therapist with feedback that will help him decide whether to continue therapy.

Mechanisms of action.

As with any form of psychotherapy, the neurophysiological nature of the effects of EMDR is currently unknown, but several mechanisms of action may contribute to the therapeutic effect. Scientists propose a range of possible mechanisms of action that distinguish EMDR from traditional CBT practices. One of these mechanisms concerns "suppression" (extinction) and "recovery" (reconsolidation). EMDR therapy proposes, among other mechanisms of action, the assimilation of adaptive information found in other memory networks that come into contact with the network containing the previously isolated anxiety event (Solomon & Shapiro, 2008). After the successful completion of therapy, it is assumed that the memory is no longer isolated, as it appears to be properly integrated into the larger memory network. This idea is quite consistent with recent neurobiological theories about memory retrieval (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998; Suzuki et al., 2004) who suggest that once a memory is accessed, it can become labile and then re-stored in an altered form. The process of EMDR associated with the attachment of new associations to previously isolated memory networks can indeed activate the recovery process.

Scientists propose a range of possible mechanisms of action that distinguish EMDR from traditional CBT practices. One of these mechanisms concerns "suppression" (extinction) and "recovery" (reconsolidation). EMDR therapy proposes, among other mechanisms of action, the assimilation of adaptive information found in other memory networks that come into contact with the network containing the previously isolated anxiety event (Solomon & Shapiro, 2008). After the successful completion of therapy, it is assumed that the memory is no longer isolated, as it appears to be properly integrated into the larger memory network. This idea is quite consistent with recent neurobiological theories about memory retrieval (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998; Suzuki et al., 2004) who suggest that once a memory is accessed, it can become labile and then re-stored in an altered form. The process of EMDR associated with the attachment of new associations to previously isolated memory networks can indeed activate the recovery process. Therefore, EMDR may have different mechanisms of action than the main mechanism of action of various types of exposure therapy, namely "repression" (Craske, 1999; Lee, Taylor & Drummond, 2006; Rogers & Silver, 2002). It is believed that "restoration" changes the original memory, and "stopping", in turn, creates a new memory that begins to compete with the old one.

Therefore, EMDR may have different mechanisms of action than the main mechanism of action of various types of exposure therapy, namely "repression" (Craske, 1999; Lee, Taylor & Drummond, 2006; Rogers & Silver, 2002). It is believed that "restoration" changes the original memory, and "stopping", in turn, creates a new memory that begins to compete with the old one.

During the evaluation phase of EMDR therapy, there are also additional mechanisms that help bring together the various fragments of memory. When undergoing exposure therapy, the client is asked to describe the memory in the most detailed way, while in EMDR therapy there are no such requirements. Rather, during the appraisal phase, the therapist helps the client isolate the negative memory image, identify the current negative belief and desired positive belief, associated emotions, and bodily sensations. Experience that has not been reworked enough can be stored in fragments (van der Kolk & Fisler, 1995). Therefore, the systematization of memory components as an element of the procedure stimulates the process of processing./s3/static.nrc.nl/bvhw/files/2017/05/data12951135-dea26e.jpg) This procedure activates memory networks containing other aspects of the negative experience, potentially enabling the client to reconnect parts of the experience, make sense of it, and facilitate the process of retaining the memory in narrative memory.

This procedure activates memory networks containing other aspects of the negative experience, potentially enabling the client to reconnect parts of the experience, make sense of it, and facilitate the process of retaining the memory in narrative memory.

Cognitive restructuring is another element of the procedure that can explain the effectiveness of EMDR. However, in traditional types of cognitive therapy, it is customary to identify some irrational belief about oneself (negative cognition), and then deliberately question it, restructure and reframe this belief, turning it into an adaptive belief about oneself (positive cognition) (Beck, Rush, Shaw & Emery, 1979). The assessment phase in EMDR differs from cognitive restructuring methods in that there is no deliberate attempt by the therapist to change or reframe the client's current belief. It is assumed that the belief will change spontaneously in the process of subsequent processing. However, from the point of view of the API, the preliminary formation of an association between negative cognition and more adaptive information that contradicts negative experiences can contribute to further processing, since it activates the corresponding adaptive networks.

The desensitization and installation phases have different mechanisms of action. One of the possible mechanisms of action is awareness. During the desensitization phase of EMDR, clients are instructed to "let whatever happens" and "just pay attention" to whatever comes up (F. Shapiro, 1989, 1995, 2001). This is quite consistent with the principles of mindfulness practice (Siegel, 2007). Instructions like this reduce excessive demands on themselves and perhaps help clients to observe without judgment what they are feeling and thinking. Research confirms that the adoption of the paradigm that sees negative thoughts and feelings as transient mental phenomena rather than as aspects of the personality (Teasdale, 1997; Teasdale et al., 2002) has a beneficial therapeutic effect. However, while meditation techniques most often ask participants to return to their original focus of attention (Tzan-Fu, Ching-Kuan & Nien-Mu, 2004), in EMDR therapy clients are asked to simply "notice" various associations as they occur.

Perceived mastery may be another important procedural element that makes EMDR an effective therapy. Whereas exposure techniques require concentration and do not encourage distraction from the incident in order to prevent avoidance, EMDR therapy uses only momentary attention to the various associations that occur within the client during sets of eye movements. Therefore, during EMDR, clients may experience an increase in the sense of being able to switch between experiencing the event, paying attention to what is happening, and communicating the change to the therapist. The client's ability to use coping strategies more effectively can improve along with their ability to cope with stress, anxiety and depression in dangerous situations. (Bandura, 2004). From an API perspective, this sense of ability and efficiency is encoded in the brain as adaptive information available to connect with memory networks containing dysfunctionally stored information.

Finally, exposure therapy maintains a high level of anxiety by initially focusing on the disturbing event, as mentioned above, while the eye movements used in EMDR seem to increase parasympathetic arousal and reduce the intensity and emotionality of negative material, as well as to increase the flexibility of attention. It is possible that such effects allow information from other memory systems to connect to a target network that contains dysfunctionally stored information (Shapiro, 1995, 2001) leading to transformation and then retrieval of the memory (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998; Suzuki et al., 2004). Further clinical studies are required to explore these hypotheses and better understand the specific, side-effects, and interactive effects of different factors on EMDR performance.

It is possible that such effects allow information from other memory systems to connect to a target network that contains dysfunctionally stored information (Shapiro, 1995, 2001) leading to transformation and then retrieval of the memory (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998; Suzuki et al., 2004). Further clinical studies are required to explore these hypotheses and better understand the specific, side-effects, and interactive effects of different factors on EMDR performance.

Conclusions.

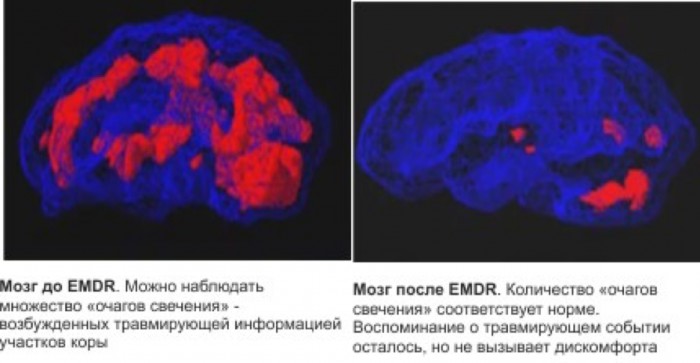

EMDR is one of the pioneering arts of psychotherapy. Primarily, this therapy is part of the evidence-based therapy group, which combines the clinical and scientific aspects of psychotherapy for decades after the establishment of recommendations for evidence-based treatments according to the Boulder Model (Fagan & Warden, 1996). Since the inception of EMDR, practitioners have always supported the development of clinical research, as evidenced by more than 30 randomized trials of trauma therapy. The API model forms the theoretical basis for EMDR, however, it is clear that the answers to the questions surrounding EMDR (and other therapies) lie in the human brain. As a result, more than ten studies have been devoted to the study of the neurobiological aspects of therapy, and their results indicate that psychotherapy and brain research should develop in tandem (Bossini, Fagiolini & Castrogiovanni, 2007; Pagani et al., 2007; Richardson et al. ., 2009).

As a result, more than ten studies have been devoted to the study of the neurobiological aspects of therapy, and their results indicate that psychotherapy and brain research should develop in tandem (Bossini, Fagiolini & Castrogiovanni, 2007; Pagani et al., 2007; Richardson et al. ., 2009).

EMDR is an integrative form of psychotherapy that includes elements that are compatible with a variety of approaches. The central place in therapy here is occupied by the body, however, the cognitive, emotional and behavioral aspects retain their importance. One of the most important advantages of EMDR is that it can also be used as a highly focused, short-term form of psychotherapy (in cases of single trauma: Shapiro, 1989; Jarero, Artigas & Luber, 2011; Kutz, Resnik & Dekel, 2008), and as a long-term, integrative, more widely applicable form of therapy (in cases of complex trauma, Korn, 2009). Along with positive psychology, EMDR is a form of humanistic therapy that believes in the client's inner resources and their ability to use those resources for personal growth. The working premise of EMDR is that the client heals himself with proper stimulation from the therapist, which leads to improved functioning of the internal information processing system (Shapiro, 1995, 2001). And finally, in all corners of the world, in dozens of countries, therapists of all cultures and professional orientations are successfully trained in EMDR. The very fact that EMDR has been successfully used in various cultures (Kim et al., 2010; Kavakcı, Kaptanog lu, Kug u & Dog an, 2010; Konuk et al., 2006; Uribe & Ramirez, 2006) indicates that EMDR makes a huge contribution to the development of the world of psychotherapy and to the well-being of mankind.

The working premise of EMDR is that the client heals himself with proper stimulation from the therapist, which leads to improved functioning of the internal information processing system (Shapiro, 1995, 2001). And finally, in all corners of the world, in dozens of countries, therapists of all cultures and professional orientations are successfully trained in EMDR. The very fact that EMDR has been successfully used in various cultures (Kim et al., 2010; Kavakcı, Kaptanog lu, Kug u & Dog an, 2010; Konuk et al., 2006; Uribe & Ramirez, 2006) indicates that EMDR makes a huge contribution to the development of the world of psychotherapy and to the well-being of mankind.

In summary, EMDR sees current problems as primarily related to dysfunctionally stored memories. There is direct work with past experience that has not been adequately processed and integrated into adaptive networks. EMDR is an evidence-based psychotherapeutic approach effective in trauma therapy. However, EMDR can be used to treat a wide range of disorders due to the fact that dysfunctionally stored memories are present in clients with all kinds of clinical diagnoses. (Mol et al., 2005; Obradovicˇı, Bush, Stamperdahl, Adler & Boyce, 2010). The EMDR integrative psychotherapeutic approach uses an eight-phase, three-stage (past, present, future) protocol that aims to free the client from the influence of experience that lays the foundation for the current pathology, as well as embedding a wide variety of elements of experience and memories into a common system in order to lead the client to a state of mental health.

(Mol et al., 2005; Obradovicˇı, Bush, Stamperdahl, Adler & Boyce, 2010). The EMDR integrative psychotherapeutic approach uses an eight-phase, three-stage (past, present, future) protocol that aims to free the client from the influence of experience that lays the foundation for the current pathology, as well as embedding a wide variety of elements of experience and memories into a common system in order to lead the client to a state of mental health.

Although the exact mechanisms behind these changes are unknown to us, a large number of randomized trials confirm that the eye movements used in EMDR correlate with the desensitization effect. Given the results of studies that show that eye movements per se lead to increased attentional flexibility and memory retrieval, it can be hypothesized that decreased arousal levels allow adaptive information from other memory networks to connect with the network that stores dysfunctionally stored information. This may lead to adaptive memory retrieval. However, as with other forms of psychotherapy, further brain research is needed to determine the exact biological basis for the therapeutic effect. Additional research is also needed to determine the neurobiological basis of eye movements and the interactive effects of various components of the EMDR therapy process. Given that homework is not used in EMDR therapy, daily therapy can easily validate the results of these studies, reducing the time frame that is usually required for other forms of therapy.

However, as with other forms of psychotherapy, further brain research is needed to determine the exact biological basis for the therapeutic effect. Additional research is also needed to determine the neurobiological basis of eye movements and the interactive effects of various components of the EMDR therapy process. Given that homework is not used in EMDR therapy, daily therapy can easily validate the results of these studies, reducing the time frame that is usually required for other forms of therapy.

Literature

1. Besser-Siegmund, K. EMDR in coaching / K. Besser-Siegmund, X Siegmund; per. with him N. Gust. - St. Petersburg: Werner Regen Publishing House, 2007. - 160 p.

2. Shapiro, F. Psychotherapy of emotional trauma using eye movements: basic principles, protocols and procedures /F. Shapiro; per. from English. A.S. Rigina - M .: Independent firm "Class" - 1998 - 496 p.

3. Perkins, B.R., & Rouanzoin, C.C. A critical evaluation of current views regarding eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): Clarifying points of confusion. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58 - 2002 - pp. 77–97.

Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58 - 2002 - pp. 77–97.

4. Shapiro, F. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Basic principles, protocols and procedures (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press - 2001 - 450 p.

5. Shapiro, F. Paradigms, processing, and personality development. In F. Shapiro (Ed.), EMDR as an integrative psychotherapy approach: Experts of diverse orientations explore the paradigm prism. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books - 2002 - pp. 3–26

6. Shapiro, F. EMDR, Adaptive Information Processing, and Case Conceptualization / F. Shapiro // Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, Volume 1, Number 2 – 22007 – pp. 68-87

EMDR method

EMDR Latvija

professional association of EMDR therapists

Description of the EMDR method

EMDR eye) is a new unique technique of psychotherapy, extremely effective in the treatment of emotional trauma. All psychotherapists world today, in addition to classical methods, it is used in working with those who have experienced emotional trauma, because with the help of EMDR can solve psychological problems much faster, than traditional forms of psychotherapy.

Discovery of the method:

The emergence of the EMDR technique is associated with random observation calming effects of spontaneously repetitive eye movements to bad thoughts.

EMDR was created by psychologist-psychotherapist Francine Shapiro in 1987. One day, while walking in the park, she noticed that the thoughts that had been troubling her suddenly vanished. Francine noted also, that if these thoughts are again called into the mind, they no longer have such a negative effect and do not seem so real as before. She noted that when disturbing thoughts, her eyes would spontaneously move rapidly side to side and up and down diagonally. Then disturbing thoughts disappeared, and when she deliberately tried remember them, then the negative charge inherent in these thoughts was significantly reduced.

Noticing this, Francine began to move her eyes intentionally, focusing on various unpleasant thoughts and memories. these thoughts also disappeared and lost their negative emotional coloring.

Shapiro asked her friends, colleagues and participants psychological seminars to do the same exercise. results were striking: the level of anxiety was reduced and people could more calmly and realistically perceive what bothered them.

This new psychotherapy technique was discovered by accident. In less than 20 years, Shapiro and her colleagues have specialized in more than 25,000 psychotherapists from various countries, which brought the method among the most rapidly spreading in around the world of psychotechnology.

Francine Shapiro now works at the Institute for Brain Research in Palo Alto (USA). In 2002 she was awarded the Sigmund Freud - the most important world award in the field psychotherapy.

How does EMDR work?

Each of us has an innate physiological mechanism information processing that keeps our mental health at the optimum level. Our natural inner information processing system is organized in such a way that that it allows her to restore mental health so much like how the body naturally recovers from injury. So, for example, if you cut your hand, then the forces of the body will focus on healing the wound. If something prevents such healing - some external object or repeated trauma - the wound begins to fester and causes pain. If the obstacle is removed, the healing will be completed.

So, for example, if you cut your hand, then the forces of the body will focus on healing the wound. If something prevents such healing - some external object or repeated trauma - the wound begins to fester and causes pain. If the obstacle is removed, the healing will be completed.

The balance of our natural processing system information at the neurophysiological level may be disturbed during trauma or stress arising in the course of our life. This blocks the natural tendency information processing system of the brain to provide state of mental health. As a result, there are various psychological problems psychological problems are the result of accumulated nervous system of negative traumatic information. key to psychological change is the ability perform the necessary information processing.