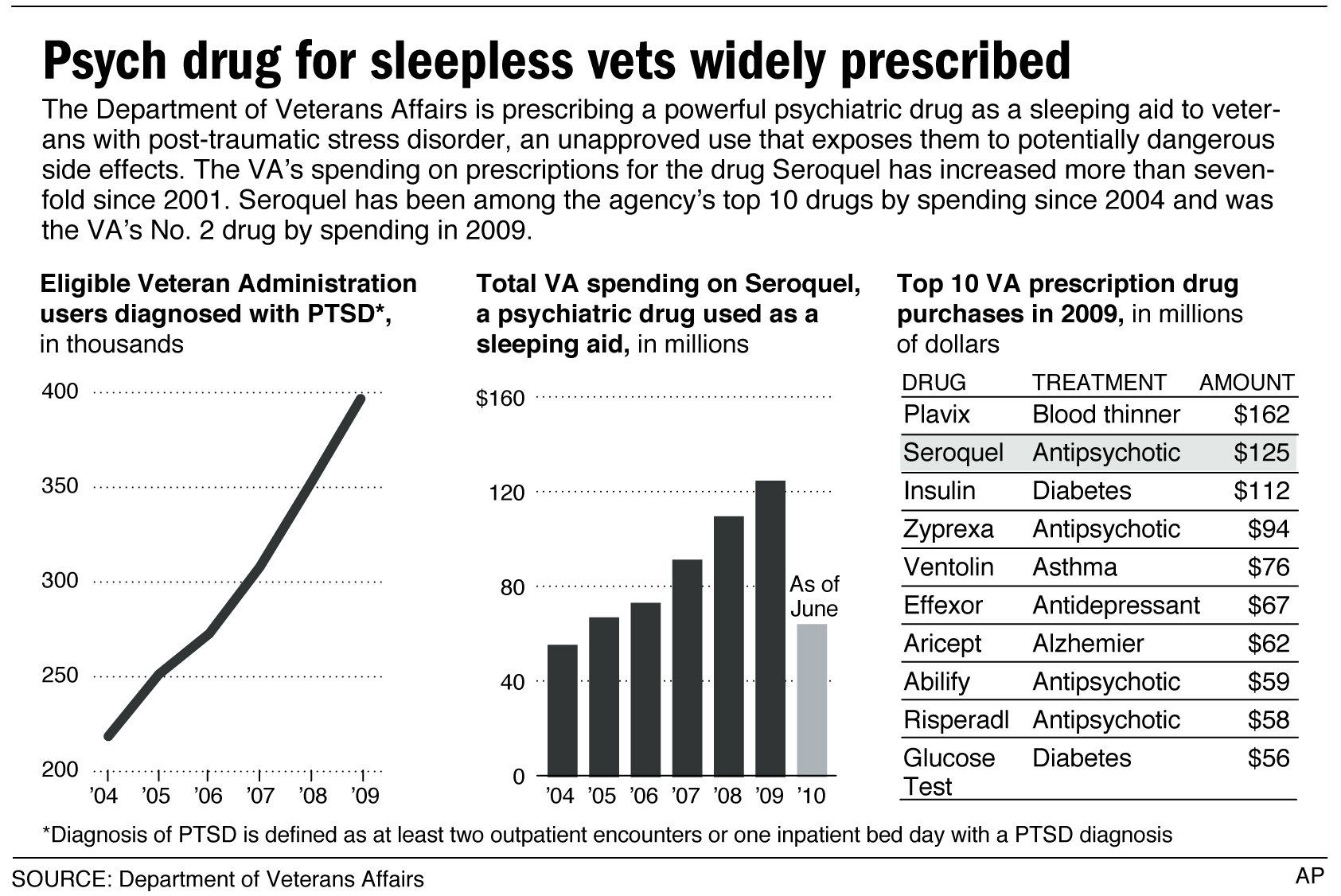

Seroquel for sleep aid

Will it work for you?

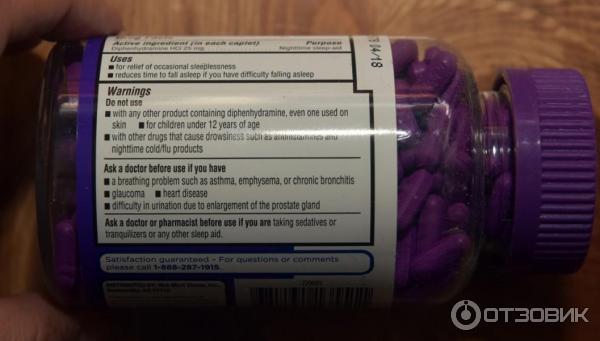

Many doctors are unwilling to prescribe traditional sleeping tablets because of concerns that they can lead to addiction and tolerance. GPs often turn to other types of drugs that display sedative side effects and instead prescribe these to help people sleep.

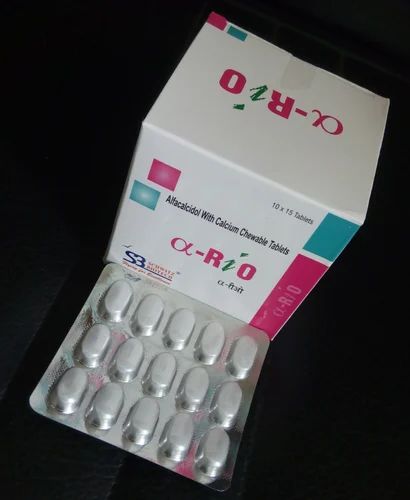

These drugs are used ‘off label’: they’re not licensed to treat certain conditions but can be effective, nevertheless. Quetiapine is one such off label drug used to treat insomnia. You can find more information about quetiapine from NICE on their website.

Quetiapine is an antipsychotic medication

In the UK quetiapine is licensed for the following indications:

- schizophrenia

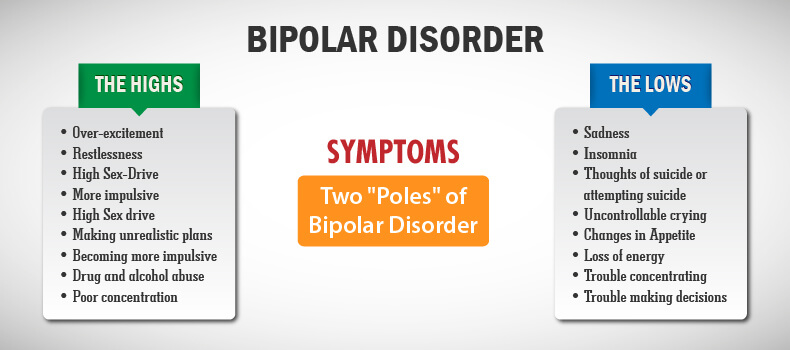

- treatment of mania in bipolar disorder

- treatment of depression in bipolar disorder

- prevention of mania and depression in bipolar disorder

- in addition to primary medication to treat major depression.

In the USA quetiapine is commonly sold under the brand name Seroquel.

Quetiapine as a treatment for primary insomnia

Despite a lack of evidence pointing to its effectiveness in helping improve sleep, quetiapine is increasingly prescribed at low doses to manage sleep disorders.

For instance, between 2005 and 2012, prescriptions of quetiapine for sleep disturbances increased by 300% in Canada.1

In addition, data from a wide-ranging US survey found that between 1999 and 2010, quetiapine was the fourth most common drug prescribed for insomnia (11%).2

Neither of these countries had approved the drug as a licensed alternative to treating insomnia.3

People with sleeping issues often turn to medication first. Many people don’t know that there are more effective treatments without side effects. Sleepstation’s online CBTi programme can significantly improve sleep in just four sessions.

Sleepstation is:

clinically validated and accredited by the NHS

proven to be more effective than medication

delivered entirely online

uniquely personal to your situation

fully supported by sleep experts.

Is quetiapine useful as a treatment for insomnia?

Quetiapine can improve symptoms that may interfere with sleep, such as reducing feelings of anxiety and depression. So it’s difficult to evaluate its effects as a sleep medication when the drug is designed to improve symptoms that, in themselves, also affect sleep.

To establish whether the drug has a direct effect on sleep, we can look at trials with healthy volunteers who do not show any signs of psychiatric illness. These studies allow the drug’s influence on sleep to be accurately assessed.

However, where quetiapine is concerned, there have been very few studies that have evaluated its effect on sleep in patients who were not also experiencing a psychiatric illness.

One study evaluated 14 healthy males who were given placebo or quetiapine at 25mg and 100mg doses for three consecutive nights. 4

4

Both doses of quetiapine produced statistically significant improvements in objective and subjective ratings of sleep including:

- total sleep time

- sleep efficiency

- sleep latency

- duration of stage N2 sleep.

Despite these positive effects, the 100mg dose was found to decrease the amount of REM sleep, which is a stage of sleep important for our emotional wellbeing.

The 100mg dose also increased the number of periodic leg movements and two subjects taking quetiapine experienced orthostatic hypotension, which is a drop in blood pressure when a person moves from sitting to standing.

In a study of people with primary insomnia, 25 participants received either 25mg of quetiapine or a placebo. No significant improvements were seen in how long people slept for, how quickly they fell asleep, their daytime alertness or sleep satisfaction.5

A more recent study replicated insomnia by using traffic noise to keep people awake. They found that 50mg quetiapine increased sleep continuity and total sleep time when compared to placebo.

They found that 50mg quetiapine increased sleep continuity and total sleep time when compared to placebo.

However, there was evidence of hangover effects in the morning with quetiapine causing daytime sleepiness and difficulty concentrating.6

How quetiapine could disrupt your sleep

Quetiapine has a long list of side effects and a large number of these are potentially disruptive to your sleep. It’s hardly ideal for a drug that’s meant to help you sleep!

Side effects that could disrupt your sleep — and that occur in at least one in 10 people taking quetiapine — include:

- dizziness, weakness and shortness of breath

- feeling sleepy

- headaches, fever, shortness of breath

- a dry mouth

- weight gain and increased appetite

- a rapid or irregular heartbeat

- constipation, upset stomach, indigestion, vomiting

- swelling of arms or legs

- sleep disorders

- feeling irritated

- thoughts of suicide.

In the clinical trials of quetiapine there have been other reports of side effects that could potentially disturb sleep.

Two patients, on low dose quetiapine for insomnia, discontinued the drug due to akathisia — a movement disorder characterised by a feeling of inner restlessness and an inability to stay still.7

In another study of low dose quetiapine for insomnia in people diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, two out of 13 participants stopped using the drug due to an exacerbation of restless leg symptoms.8

Quetiapine or sleeping tablets?

One of the most cited reasons for avoiding the use of using traditional sleeping tablets to treat insomnia is a concern that they’re addictive. This is why GPs look to prescribe alternatives that are not associated with addiction.

However repeated studies have shown that quetiapine has abuse potential. 910111213 This raises serious questions concerning its suitability as a replacement for either benzodiazepines or so-called ‘Z’ drugs.

Does the evidence warrant use of quetiapine for insomnia?

While there’s some evidence that quetiapine can improve sleep in healthy participants, only minor improvements in sleep are seen in patients with insomnia.

The unclear results seen in the few trials described above provide little evidence to justify prescribing quetiapine for insomnia. 121314 The general consensus amongst studies is that quetiapine should be avoided as a drug for insomnia.

The results are reinforced by a review of quetiapine for use in insomnia which concluded that any benefit in the treatment of insomnia has not been proven to outweigh potential risks. 15

This is true even in patients who require treatment for a condition for which quetiapine is approved, such as schizophrenia.

The general consensus amongst studies is that quetiapine should be not be used as a drug for insomnia.

So it’s difficult to understand how a drug hardly renowned for improving insomnia — and associated with such a broad range of side-effects and a potential for addiction and abuse — can be so widely prescribed.

Should you question quetiapine?

If you’re prescribed quetiapine by your GP or psychiatrist then you have a legitimate case for asking why they’re using this drug rather than the benzodiazepines and the ‘Z’ drugs that have proven effectiveness in the treatment of insomnia.

Remember this is about your health and your sleep, not theirs. You have every right to discuss the most appropriate treatment for your condition.

The best starting point for treating insomnia that has lasted for more than four weeks (chronic insomnia) is well-recogised to be cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi).

Unlike sleeping pills, CBTi helps you overcome the underlying causes of your sleep problems rather than just alleviating the symptoms. It’s the method we use at Sleepstation and it’s incredibly effective.

The first step in treating insomnia with CBTi is to identify the causes of the insomnia. At Sleepstation, we guide you through this, then help you to address the causes of your sleep problem and provide you with the tools you need to rebuild your sleep.

With help from our sleep experts and sleep coaches, you’ll better understand your sleep and learn ways to combat your sleep problems and stop them reoccuring. Most people see an improvement their sleep after just three sessions.

Sleepstation’s programme works if you’re currently taking sleeping tablets and can help to reduce the amount you’re taking, or stop altogether. You can get started in just a couple of clicks, here.

Summary

- Quetiapine is neither approved nor recommended for primary insomnia although the drug is often prescribed off-label as a sleep aid.

- There is evidence of addiction to quetiapine.

- Side effects associated with quetiapine — such as next morning hangover symptoms and daytime fatigue — means that patients should be cautious.

- Drugs such as quetiapine cannot treat a sleep problem, they will only mask them.

- Sleepstation is a clinically-validated, drug-free alternative that is proven to improve sleep.

References

-

Pringsheim T, Gardner DM. Dispensed prescriptions for quetiapine and other second-generation antipsychotics in Canada from 2005 to 2012: a descriptive study. CMAJ Open 2014;2:E225-32.

↑ -

Bertisch SM, Herzig SJ, Winkelman JW, Buettner C. National use of prescription medications for insomnia: NHANES 1999-2010. Sleep 2014;37:343–9.

↑ -

Marston L, Nazareth I, Petersen I, Walters K, Osborn DPJ. Prescribing of antipsychotics in UK primary care: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006135.

↑ -

Cohrs S, Rodenbeck A, Guan Z, Pohlmann K, Jordan W, Meier A, et al. Sleep-promoting properties of quetiapine in healthy subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:421–9.

↑

-

Tassniyom K, Paholpak S, Tassniyom S, Kiewyoo J. Quetiapine for primary insomnia: a double blind, randomized controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai 2010;93:729–34.

↑ -

Karsten J, Hagenauw LA, Kamphuis J, Lancel M. Low doses of mirtazapine or quetiapine for transient insomnia: A randomised, double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol 2017;31:327–37.

↑ -

Catalano G, Grace JW, Catalano MC, Morales MJ, Cruse LM. Acute akathisia associated with quetiapine use. Psychosomatics 2005;46:291–301.

↑ -

Juri C, Chaná P, Tapia J, Kunstmann C, Parrao T. Quetiapine for insomnia in Parkinson disease: Results from an open-label trial.

↑ Clin Neuropharmacol 2005;28:185–7.

Clin Neuropharmacol 2005;28:185–7. -

Waters BM, Joshi KG. Intravenous quetiapine-cocaine use (“Q-ball”). Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:173–4.

↑ -

Hussain MZ, Waheed W, Hussain S. Intravenous quetiapine abuse. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1755–6.

↑ -

Pinta ER, Taylor RE. Quetiapine addiction? Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:174–5.

↑ -

Pierre JM, Shnayder I, Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC. Intranasal quetiapine abuse. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1718.

↑ -

Erdoğan S. Quetiapine in substance use disorders, abuse and dependence possibility: a review.

↑ Turk Psikiyatri Derg 2010;21:167–75.

Turk Psikiyatri Derg 2010;21:167–75. -

Wine JN, Sanda C, Caballero J. Effects of quetiapine on sleep in nonpsychiatric and psychiatric conditions. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:707–13.

↑ -

Pigeon WR. Diagnosis, prevalence, pathways, consequences & treatment of insomnia. Indian J Med Res 2010;131:321–32.

↑

Quetiapine for primary insomnia: Consider the risks

Review

Vania Modesto-Lowe, MD, MPH, Agata K. Harabasz, MD and Sophia A. Walker, MD

Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine May 2021, 88 (5) 286-294; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.88a.20031

- Article

- Figures & Data

- Info & Metrics

ABSTRACT

The second-generation antipsychotic drug quetiapine (Seroquel) is increasingly being used off-label for treating insomnia in the general population, possibly to avoid standard medications with known addictive qualities and adverse side effects. However, evidence to support using it in this way is scant, and quetiapine is associated with weight gain and other metabolic effects. It must be used cautiously and with appropriate monitoring for adverse effects and abuse.

However, evidence to support using it in this way is scant, and quetiapine is associated with weight gain and other metabolic effects. It must be used cautiously and with appropriate monitoring for adverse effects and abuse.

KEY POINTS

Quetiapine affects multiple central nervous system receptors, resulting in a variety of effects, including sedation.

The use of quetiapine to treat insomnia should be confined primarily to patients with comorbid mood or schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Compared with many other antipsychotic drugs, quetiapine is less associated with dystonia and extrapyramidal side effects but tends to cause weight gain, metabolic syndrome, and QTc prolongation.

Body mass index, weight, blood pressure, fasting glucose, and lipid levels should be measured before starting treatment and then regularly monitored, even for low doses.

Despite having no euphoric effects, quetiapine is often abused to enhance or counter side effects of illicit drugs.

Quetiapine carries particular risks for elderly patients.

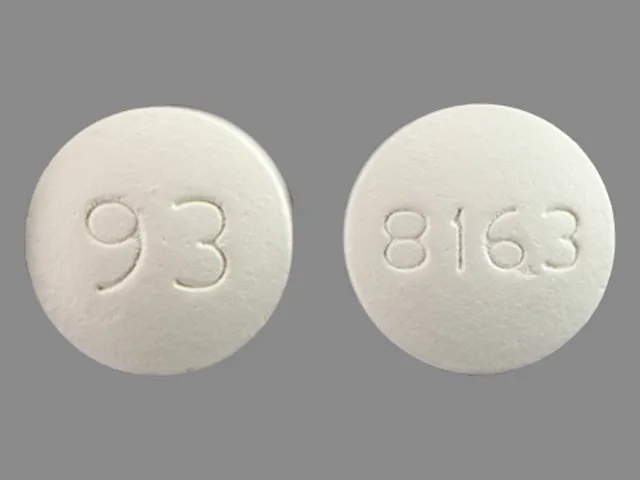

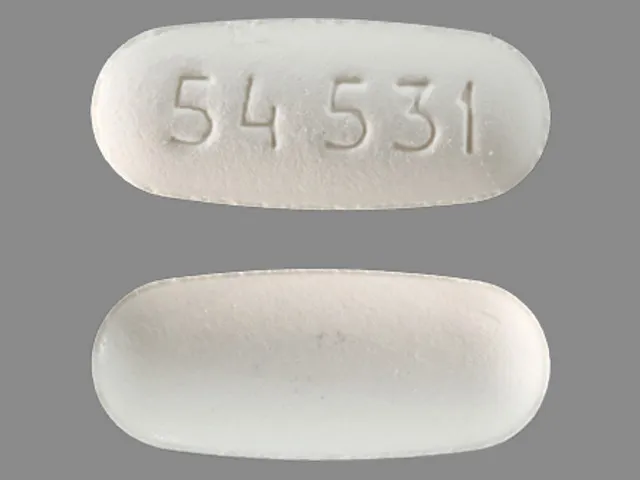

Prescriptions for quetiapine (Seroquel), a second-generation antipsychotic medication, have risen sharply in recent years.1,2 Despite its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) only for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (depression, acute mania, and maintenance), and major depressive disorder (as an adjunct medication),3 only a minority of patients filling prescriptions for quetiapine have these diagnoses. Rather, quetiapine is increasingly being used off-label, including for insomnia, anxiety, agitation, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).4 It is generally regarded as being nonaddictive and having a good safety profile. However, its cardiometabolic effects and potential for abuse warrant caution for its off-label use.

This article focuses on the use of quetiapine for treating insomnia, its basic pharmacology, evidence of efficacy, and adverse effects, and it provides recommendations for clinical monitoring of patients receiving the drug.

AN INCREASINGLY POPULAR DRUG

Second-generation antipsychotic use has increased worldwide, with quetiapine, risperidone, and olanzapine being the most frequently prescribed.1 In Canada, prescriptions written by family physicians for quetiapine increased 300% from 2005 to 2012, with a 10-fold increase in its use for sleep disorders.2 The pattern was similar in the United States from 1996 to 2003, with up to 70% of prescriptions for second-generation antipsychotics being written for conditions other than psychosis.4

Bertisch et al,5 using US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data from 1999 to 2010, found that nearly 3% of 32,328 respondents reported having used a commonly prescribed insomnia medication over the previous month. Quetiapine ranked fourth among frequently prescribed medications, following the “Z-drugs” (the benzodiazepine receptor agonists zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone), trazodone, and benzodiazepines. 5

5

Prescriptions for quetiapine to treat sleep disturbances have also increased in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.6–8

POTENTIAL FOR ABUSE

Quetiapine, used alone, does not produce euphoria or other pleasurable effects typically associated with drugs of abuse, but it can enhance or counter the side effects of substances such as marijuana, cocaine, and heroin,9 a practice that is colloquially referred to as “seroquelling.” Although the mechanism underlying its rewarding effects remains elusive, misuse of the drug may be driven by its ability to counteract overstimulation caused by other substances of abuse.10 There are also reports of quetiapine use for “self-detoxification,” in an effort to mitigate withdrawal symptoms from other substances such as alcohol, cocaine, benzodiazepines, and opioids.9 These trends appear to be more prevalent in correctional facilities (where commonly abused drugs are not readily available) and among patients with a previous history of substance abuse. 9 Those who abuse quetiapine typically consume high doses, which has led to several cases of accidental overdose, some of which have been fatal.9

9 Those who abuse quetiapine typically consume high doses, which has led to several cases of accidental overdose, some of which have been fatal.9

These emerging patterns of abuse, along with the drug’s potential metabolic and cardiac complications, signal the need for caution for use in the general patient population.

DIFFERENT DOSES HAVE DIFFERENT EFFECTS

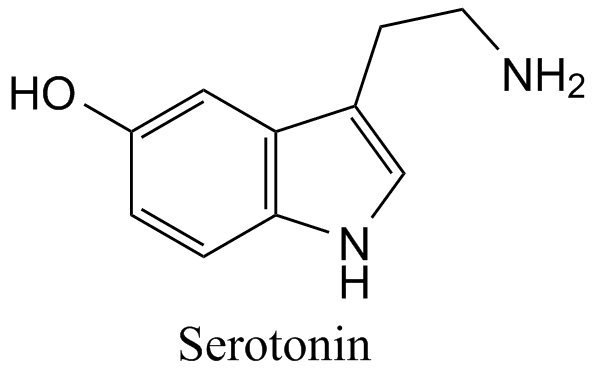

Quetiapine works similarly to other second-generation antipsychotics, but its uniqueness lies in the various affinities of the drug and its active metabolite (norquetiapine) for multiple central nervous system receptors in a dose-dependent manner (Table 1). Lower dosages primarily affect histaminergic (h2) and alpha 1 and alpha 2 adrenergic receptors, mediating sedative effects.11 Medium and high doses have an additive affinity for serotonergic receptors (5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C) and the dopamine D2 receptors, causing mood stabilization and improvements in anxiety, deep sleep, and psychosis. 12

12

TABLE 1

Quetiapine activity in the central nervous system

This quality of increasing doses causing different effects has led to the “Goldilocks” analogy: “Papa Bear” doses (> 800 mg daily) are for treatment of schizophrenia, “Mama Bear” doses (300-600 mg daily) are for mood disorders, and “Baby Bear” doses (25-100 mg daily) are for sedative-hypnotic effects.13

Among antipsychotics drugs, quetiapine is the least potent binder of the D2 receptor and has the fastest dissociation time from it, which explains the larger doses required for achieving antipsychotic effects as well as its lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects.12,14

PHARMACOKINETIC PROFILE LENDS ITSELF TO ABUSE

Quetiapine is available as an oral tablet in an immediate-release formulation (time to peak plasma level 1.5 hours) and an extended-release formulation (6 hours).2,15 Its half-life, about 6 hours, is the shortest of all the second-generation antipsychotics.

The short duration to peak plasma concentration with the immediate-release formulation is generally comparable with that of many of the approved hypnotics, including Z-drugs and benzodiazepines.16 At peak plasma levels, h2-receptor occupancy is more than 90% at just 50 mg of the immediate-release formulation,13 which is consistent with the receptor profile for strong hypnotic effects even at the lowest therapeutic doses.

Quetiapine’s pharmacokinetic profile may make it more attractive for abuse, especially for crushing tablets for intravenous injection or intranasal snorting. It can also be mixed with other drugs of abuse9 to achieve faster and more intense effects, such as sedation and relaxation. Quetiapine taken through such alternative routes is associated with an increased risk of neuroleptic toxicity.10

ADVERSE EFFECTS

Weight gain, metabolic effects

Common adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics include weight gain and motor symptoms. 17 Clozapine and olanzapine are more recognized for causing weight gain, but long-term use of quetiapine is also associated with moderate weight gain (10 kg on average), as well as development of metabolic syndrome.18 The mechanism behind weight gain in this class of drugs is unclear, but antihistaminergic effects may be causing enhanced appetite.

17 Clozapine and olanzapine are more recognized for causing weight gain, but long-term use of quetiapine is also associated with moderate weight gain (10 kg on average), as well as development of metabolic syndrome.18 The mechanism behind weight gain in this class of drugs is unclear, but antihistaminergic effects may be causing enhanced appetite.

Second-generation antipsychotics also increase levels of blood glucose and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, effects that seem to resolve when treatment is stopped.19,20 While weight gain alone is concerning, the metabolic changes associated with second-generation antipsychotic use can lead to higher risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke, with quetiapine among the antipsychotic drugs associated with the largest metabolic effects.21

Low doses not totally harmless

Whether quetiapine’s metabolic effects occur even at low doses has been investigated in retrospective studies. Cates et al22 studied43 patients taking low-dose quetiapine for insomnia. About two-thirds of them gained weight: daily dosages below 200 mg at bedtime used for an average of 11 months were associated with an average weight gain of 4.9 lb (P = .037) and a body mass index (BMI) increase of 0.8 kg/m2 (P = .048).

About two-thirds of them gained weight: daily dosages below 200 mg at bedtime used for an average of 11 months were associated with an average weight gain of 4.9 lb (P = .037) and a body mass index (BMI) increase of 0.8 kg/m2 (P = .048).

Carr et al23 studied 403 veterans taking low-dose quetiapine (average daily dose 116.8 mg) for an average of 44 months. Statistically significant increases were found in systolic blood pressure (1.95 mm Hg, P = .036), diastolic blood pressure (1.97 mm Hg, P = .001), BMI (0.52 kg/m2, P = .001), weight (1.88 kg, P = .002), and fasting blood glucose (6.71 mg/dL, P = .002).

Williams et al24 investigated low-dose quetiapine (< 100 mg daily for at least 1 month) in 534 patients in military hospitals. The mean weight gain was 5.56 ± 1.25 lb (P < .001) at 6 months and 10.58 ± 2.20 lb (P < .001) at 12 months compared with baseline.

Extrapyramidal effects

The low affinity of quetiapine for the D2 receptor, as well as a preference for binding to D2 receptors in the limbic pathway over the striatum, make movement disorders a less prominent side effect.25 However, extrapyramidal adverse effects do occur,19 with reports of restless legs syndrome, tardive dyskinesia, akathisia, and periodic leg movement disorder.14 In studies of quetiapine for bipolar disorder, the incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms increased in a dose-dependent manner, occurring in around 7% to 12% of patients.26,27

QTc prolongation

Quetiapine’s labeling carries a warning for QTc prolongation. Risk is dose-dependent.

Sedation

Given their action on histamine receptors, second-generation antipsychotics commonly cause sedation. Quetiapine also has sleep latency-enhancing properties (reducing the time from being fully awake to falling asleep), attributable to its serotonergic action, leading to the drug’s off-label use for insomnia. 11 Outside of this context, sedation is generally considered to be an undesirable side effect for most patients.18

11 Outside of this context, sedation is generally considered to be an undesirable side effect for most patients.18

Some side effects lessened

Quetiapine’s low affinity for D2 receptors results in fewer of the endocrine side effects associated with antipsychotic drugs, namely, prolactin elevation and associated amenorrhea, galactorrhea, sexual dysfunction, and osteoporosis.12,14,18

CONCERNS FOR THE ELDERLY

Use of second-generation antipsychotics is becoming more widespread in the elderly as clinicians try to avoid adverse effects (particularly extrapyramidal symptoms) of traditional antipsychotics.28 However, use of second-generation antipsychotics comes with its own set of risks in this population. Second-generation antipsychotics have received FDA black-box warnings for a nearly twofold increase in incidence of cardiovascular events, stroke, and overall mortality.21 The American Geriatrics Society 2019 Beers Criteria note an increased rate of cognitive decline associated with antipsychotics in patients with dementia and strongly recommends avoiding their use in this population. 29

29

Given its action on adrenergic receptors, quetiapine can be associated with orthostatic hypotension, especially in the elderly.12 Syncope from hypotension can lead to hip fractures, transient ischemic attacks, myocardial infarction, and even death.21 A 2013 study investigating 4 second-generation antipsychotics to treat psychiatric conditions in patients over age 40 found a high incidence of side effects (50% of participants) and life-threatening conditions (24%), noting that adverse effects were twice as common with quetiapine than with the other drugs.30 Furthermore, quetiapine’s clearance is about 40% lower in elderly patients than in younger patients.25 In view of the increasing use of second-generation antipsychotics in the elderly, these findings are especially worrisome.

STANDARD INSOMNIA MEDICATIONS HAVE DISADVANTAGES

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition31 defines insomnia as difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, or early morning awakening, resulting in significant physical or emotional distress. Insomnia affects about 30% of the population worldwide, and 10% have symptoms that severely affect their daily function.32 People with insomnia often experience irritability, fatigue, physical distress, and impaired cognition.32 The disorder has been linked with poor academic and work functioning as well as cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and hypertension.32 Therapeutic goals for patients with insomnia include improving sleep and daytime function and reducing distress.32

Insomnia affects about 30% of the population worldwide, and 10% have symptoms that severely affect their daily function.32 People with insomnia often experience irritability, fatigue, physical distress, and impaired cognition.32 The disorder has been linked with poor academic and work functioning as well as cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and hypertension.32 Therapeutic goals for patients with insomnia include improving sleep and daytime function and reducing distress.32

Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs

Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs have been approved by the FDA for treating insomnia. They enhance gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission, leading to sedation, reduced sleep latency, and increased sleep efficiency. While benzodiazepines nonspecifically bind to GABA receptors in the central nervous system, Z-drugs preferentially bind to the GABA receptor alpha-1 subunit, making them less sedating. This subunit mediates sleep effects while appearing to confer a better safety profile for the Z-drugs. 11 However, to varying degrees, both classes are associated with cognitive and memory impairments, rebound insomnia, risk of dependence and misuse, as well as car accidents, falls, and workplace accidents.11

11 However, to varying degrees, both classes are associated with cognitive and memory impairments, rebound insomnia, risk of dependence and misuse, as well as car accidents, falls, and workplace accidents.11

Because benzodiazepines are associated with tolerance and subsequent withdrawal, treatment is recommended for only 2 to 4 weeks at a time.33 Given these risks and limitations, as well as the status of these drugs as schedule IV controlled substances requiring prescription monitoring, physicians are often hesitant to prescribe them to patients in favor of alternatives.6

IS QUETIAPINE THE ANSWER?

Quetiapine is increasingly being turned to as an off-label alternative for treating insomnia, owing to its well-known sedative and sleep-promoting effects at low doses.

Study in healthy men

In a seminal 2004 study, Cohrs et al34 explored the effects of quetiapine on sleep architecture and subjective sleep quality in 14 healthy men, using self-assessment and polysomnography recordings 3 times (4 days apart) for 3 consecutive nights. In the second set (standard sleep conditions) and third set (acoustic stress conditions), treatment was given on the first and second night, consisting of either placebo, quetiapine 25 mg, or quetiapine 100 mg by mouth 1 hour before sleep.

In the second set (standard sleep conditions) and third set (acoustic stress conditions), treatment was given on the first and second night, consisting of either placebo, quetiapine 25 mg, or quetiapine 100 mg by mouth 1 hour before sleep.

Relative to placebo, quetiapine 25 mg and 100 mg significantly improved subjective sleep quality and sleep initiation, duration, and efficiency, with a dose-dependent increase in stage 2 sleep. Periodic leg movements during sleep were noted with quetiapine 100 mg.

Studies in mood and psychotic disorders

Guidelines from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine35 and others agree that off-label use of antipsychotics should be avoided, although quetiapine may be useful for insomnia in patients with psychiatric disorders.

In 2009, Wine et al36 reviewed 10 controlled studies and case reports assessing the effects of immediate-release quetiapine on sleep in patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, history of trauma, or depression. Their analysis suggested that quetiapine improved total sleep time, efficiency, and subjective sleep within a dose range of 12.5 mg to 800 mg; however, decreased rapid-eye-movement sleep was noted in some populations. Notable adverse events included akathisia, metabolic changes, and periodic leg movements.

Their analysis suggested that quetiapine improved total sleep time, efficiency, and subjective sleep within a dose range of 12.5 mg to 800 mg; however, decreased rapid-eye-movement sleep was noted in some populations. Notable adverse events included akathisia, metabolic changes, and periodic leg movements.

In 2014, Anderson and Vande Griend37 analyzed studies investigating quetiapine for insomnia, including a review of the 2010 EMBOLDEN II (Efficacy of Seroquel for Bipolar Depression) trial,38 which found that quetiapine improved sleep in patients with bipolar depression over 8 weeks. Despite this, Anderson and Vande Griend argued that given the insufficient evidence of efficacy for treating insomnia and potential risks associated with the drug, they did not recommend quetiapine for insomnia even in patients with psychiatric disorders.

In 2008, Endicott et al39 conducted a secondary analysis of the large multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled BOLDER (Bipolar Depression) I and II trials, which had demonstrated efficacy of quetiapine for acute bipolar depression. 26,27 In a secondary analysis, they found sleep quality and total sleep time to be improved among patients treated with quetiapine.

26,27 In a secondary analysis, they found sleep quality and total sleep time to be improved among patients treated with quetiapine.

Studies in posttraumatic stress disorder

Some data support the use of quetiapine for PTSD symptoms such as nightmares and insomnia. A 2005 study40 in 20 postwar veterans with PTSD found that adding low-dose quetiapine resulted in significant improvements in sleep quality, latency, duration, night terrors, and nightmares.

A 2016 randomized controlled trial41 investigating quetiapine monotherapy for treatment of PTSD found a statistically significant reduction in the total Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale score (P = .02) and its re-experiencing (P = .0004) and hyperarousal (P = .007) subscale scores compared with placebo. No statistically significant differences in weight or blood pressure were found between groups, but quetiapine use was associated with increased somnolence and sedation.

Byers et al42 compared prazosin and quetiapine for treating nighttime symptoms in veterans with PTSD (N = 237) and found that short-term effectiveness of the 2 drugs was similar at 60%. However, patients taking prazosin were significantly more likely to remain in the study, and those in the quetiapine group were likelier to stop the medication because of side effects.

Studies for primary insomnia

A 2012 summary of a 2011 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality review of safety and efficacy data of off-label uses for atypical antipsychotics17 was inconclusive concerning the use of quetiapine for insomnia. Only 1 relevant study met the authors’ inclusion criteria: a 2010 study43 in just 13 patients with primary insomnia conducted in Thailand. In this randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial, participants received either quetiapine 25 mg or placebo each night for 2 weeks. There were nonsignificant trends for longer total sleep time and shorter sleep latency in the quetiapine group.

The 2014 Anderson and Vande Griend37 analysis of studies investigating quetiapine for insomnia concluded that data were insufficient to make a decision regarding safety and efficacy for this use. Existing literature was scarce, consisting of studies that included only small numbers of patients with specific conditions, and few studies used objective sleep quality measures such as polysomnography. They concluded that given its high side-effect profile and lack of data on efficacy, quetiapine should not be used to treat insomnia.

In 2018, Atkin et al11 reviewed the evidence for multiple pharmacologic agents used for insomnia and compared their effect on sleep physiology. The authors concluded that there was limited evidence to support the use of quetiapine for insomnia in the general population, but there may be a role for using it to improve sleep in patients with conditions that can be treated with quetiapine, such as psychotic or mood disorders. They also concluded that compared with other medications used for insomnia, quetiapine poses a low risk of dependence.

MANY BELIEVE OFF-LABEL QUETIAPINE TO BE SAFER THAN ALTERNATIVES

Why do some clinicians prescribe quetiapine off-label?

In 2017, Chow et al44 reviewed the use of nighttime-only quetiapine in 83 children and adolescents treated in an inpatient psychiatric setting. Forty seven (57%) received it for insomnia alone, and 21 (25%) received it for insomnia plus another indication. Youths in the first group had longer lengths of stay and were more likely to be female and have anxiety, eating disorders, or borderline personality disorder. Hence, quetiapine probably was prescribed in an effort to target multiple issues (eg, mood, anxiety, sleep) while avoiding polypharmacy.

In 2018, Kelly et al45 investigated outpatient prescribing of quetiapine among family physicians. Quetiapine was generally reserved for patients who had not responded to other therapies or had psychiatric comorbidities or difficult social backgrounds. Many physicians prescribed it to avoid benzodiazepine use and minimize risk for abuse. Many physicians interviewed believed that low doses of quetiapine were generally safe, so they did not monitor patients for side effects.

Many physicians interviewed believed that low doses of quetiapine were generally safe, so they did not monitor patients for side effects.

CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

Considerations for use for primary insomnia

Given the scant evidence in favor of using quetiapine in the general population to treat insomnia and the risk of metabolic side effects even at low doses, the drug should be used with caution and only after other drug options have been exhausted. Practitioners should also consider prescribing it only in short courses in an effort to limit its long-term effects.20 For patients currently using it, providers should look for opportunities to discontinue it if clinically indicated.

Before prescribing quetiapine, one should compare its expected benefits (improved mood, sleep, functioning) and risks (metabolic syndrome, motor side effects, abuse).21

Age and comorbidities should be considered, particularly personal and family history of obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. 20

20

Given its reduced drug clearance in older individuals, caution should be used when dosing quetiapine for patients over age 65.

Patients at risk of QTc prolongation (those with heart disease, advanced age, taking other QTc-prolonging medications, electrolyte abnormalities, bradycardia, congenital long QT syndrome) should have an electrocardiogram and potassium level obtained after initiation and any time the dose or risk factors change.21

As with other second-generation antipsychotic drugs, signs of agranulocytosis should be monitored.

In pregnancy, antipsychotics may increase the risks of gestational diabetes, hypertension, and congenital malformation, although evidence for the safety of quetiapine in this setting is limited and conflicting.21

Monitor for metabolic changes

Detecting metabolic effects requires vigilance. Recommendations from the American Diabetes Association and allied organizations in 2004 are outlined in Table 2. 20 In patients with existing metabolic or cardiovascular disease or in those who gain 5% or more of their initial weight, alternative medications or closer monitoring is required.

20 In patients with existing metabolic or cardiovascular disease or in those who gain 5% or more of their initial weight, alternative medications or closer monitoring is required.

TABLE 2

Recommendations for monitoring during quetiapine treatment

Monitor for movement disorders

Patients should also be monitored for extrapyramidal side effects (Table 2), as some may be irreversible (eg, tardive dyskinesia) or otherwise cause distress (eg, restless legs syndrome, akathisia). Emergence of abnormal movements is most commonly monitored using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale,46 a survey consisting of 12 physical examination findings related to movement disorders. The scale can be employed routinely to detect tardive dyskinesia and monitor its severity over time. Provider familiarity with the scale as well as regular monitoring during follow-up visits is imperative to detect tardive dyskinesia early.46

Consider potential for abuse

Risk of drug abuse should be considered when weighing the risks and benefits of prescribing quetiapine. 10 It is important to identify patients who are at high risk of drug abuse (eg, prisoners, patients with a history of anxiolytic, sedative, or hypnotic misuse or abuse) at the onset of treatment, and to continue to monitor risk throughout treatment.47 Patients should be monitored for signs of tolerance, such as increasing dose or seeking other drugs.2

10 It is important to identify patients who are at high risk of drug abuse (eg, prisoners, patients with a history of anxiolytic, sedative, or hypnotic misuse or abuse) at the onset of treatment, and to continue to monitor risk throughout treatment.47 Patients should be monitored for signs of tolerance, such as increasing dose or seeking other drugs.2

However, the risk of misuse, abuse, and dependence with quetiapine is not as high as with benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, which require extensive follow-up and monitoring, possibly including in-person visits every 6 months to 1 year (minimum of every 3 months if the patient is also taking other controlled medications), yearly drug screening, monitoring in a state prescription monitoring and reporting system, limitations on quantity prescribed, and 2-point identification for prescribers, depending on local legislation.33,48 Second-generation antipsychotics do not require this level of monitoring.

BOTTOM LINE

In general, with proper monitoring, quetiapine may help to treat insomnia in patients with comorbid schizophrenia or mood disorders. Some data also support the use of quetiapine for nightmares and insomnia related to PTSD.

Evidence is insufficient to support the broad use of quetiapine to treat insomnia in the general patient population. Several organizations—including the American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, North American Association for the Study of Obesity, and the American Geriatric Society—have cautioned against using quetiapine off-label for sleep.20,35

Physicians need alternatives when facing difficult decisions about managing highly distressed patients. Other FDA-approved medications for sleep should be tried before quetiapine. And nonpharmacologic strategies, such as meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, and sleep hygiene, should always be recommended before drugs are given.

DISCLOSURES

The authors report no relevant financial relationships which, in the context of their contributions, could be perceived as a potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- ↵

- Halfdanarson O,

- Zoëga H,

- Aagaard L, et al

. International trends in antipsychotic use: a study in 16 countries, 2005-2014. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2017; 27(10):1064–1076. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.07.001

- ↵

- Pringsheim T,

- Gardner DM

. Dispensed prescriptions for quetiapine and other second-generation antipsychotics in Canada from 2005 to 2012: a descriptive study. CMAJ Open 2014; 2(4):E225–E232. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20140009

- ↵

- US Food and Drug Administration

. Highlights of prescribing information: Seroquel. Accessed February 12, 2021.

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/020639s069lbl.pdf.

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/020639s069lbl.pdf. - ↵

- Sankaranarayanan J,

- Puumala SE

. Antipsychotic use at adult ambulatory care visits by patients with mental health disorders in the United States, 1996-2003: national estimates and associated factors. Clin Ther 2007; 29(4):723–741. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.04.017

- ↵

- Bertisch SM,

- Herzig SJ,

- Winkelman JW,

- Buettner C

. National use of prescription medications for insomnia: NHANES 1999-2010. Sleep 2014; 37(2):343–349. doi:10.5665/sleep.3410

- ↵

- Haw C,

- Stubbs J

. Off-label use of antipsychotics: are we mad? Expert Opin Drug Saf 2007; 6(5):533–545. doi:10.1517/14740338.6.5.533

- Osborne V,

- Davies M,

- Layton D,

- Shakir SAW

.

Utilisation of extended release quetiapine (Seroquel XL™): results from an observational cohort study in England. Eur Psychiatry 2016; 33:61–67. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.12.004

Utilisation of extended release quetiapine (Seroquel XL™): results from an observational cohort study in England. Eur Psychiatry 2016; 33:61–67. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.12.004- ↵

- Huthwaite M,

- Tucker M,

- McBain L,

- Romans S

. Off label or on trend: a review of the use of quetiapine in New Zealand. N Z Med J 2018; 131(1474):45–50. pmid:29723178

- ↵

- Kim S,

- Lee G,

- Kim E,

- Jung H,

- Chang J

. Quetiapine misuse and abuse: is it an atypical paradigm of drug seeking behavior? J Res Pharm Pract 2017; 6(1):12–15. doi:10.4103/2279-042X.200987

- ↵

- Vento AE,

- Kotzalidis GD,

- Cacciotti M, et al

. Quetiapine abuse fourteen years later: where are we now? A systematic review.

Subst Use Misuse 2020;55(2):304–313. doi:10.1080/10826084.2019.1668013

Subst Use Misuse 2020;55(2):304–313. doi:10.1080/10826084.2019.1668013 - ↵

- Atkin T,

- Comai S,

- Gobbi G

. Drugs for insomnia beyond benzodiazepines: pharmacology, clinical applications, and discovery. Pharmacol Rev 2018; 70(2):197–245. doi:10.1124/pr.117.014381

- ↵

- Richelson E,

- Souder T

. Binding of antipsychotic drugs to human brain receptors focus on newer generation compounds. Life Sci 2000; 68(1):29–39. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00911-5

- ↵

- Stahl SM

. Dopamine system stabilizers, aripiprazole, and the next generation of antipsychotics, part 1, “Goldilocks” actions at dopamine receptors. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(11):841–842. doi:10.4088/jcp.v62n1101

- ↵

- Daly EJ,

- Trivedi MH

.

A review of quetiapine in combination with antidepressant therapy in patients with depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2007; 3(6):855–867. doi:10.2147/ndt.s1862

A review of quetiapine in combination with antidepressant therapy in patients with depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2007; 3(6):855–867. doi:10.2147/ndt.s1862 - ↵

- DeVane CL,

- Nemeroff CB

. Clinical pharmacokinetics of quetiapine: an atypical antipsychotic. Clin Pharmacokinet 2001; 40(7):509–522. doi:10.2165/00003088-200140070-00003

- ↵

- Roehrs T,

- Roth T

. Insomnia pharmacotherapy. Neurotherapeutics 2012; 9(4):728–738. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0148-3

- ↵

- Maher AR,

- Theodore G

. Summary of the comparative effectiveness review on off-label use of atypical antipsychotics. J Manag Care Pharm 2012; 18(5 suppl B):S1–S20. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2012.18.s5-b.1

- ↵

- Leucht S,

- Cipriani A,

- Spineli L, et al

.

Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013; 382(9896):951–962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3

Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013; 382(9896):951–962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3 - ↵

- Xu H,

- Zhuang X

. Atypical antipsychotics-induced metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a critical review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2019; 15:20872099. doi:10.2147/NDT.S208061

- ↵

- American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association

- American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists

- North American Association for the Study of Obesity

. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27(2):596–601. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.2.596

- ↵

- Solmi M,

- Murru A,

- Pacchiarotti I, et al

.

Safety, tolerability, and risks associated with first-and second-generation antipsychotics: a state-of-the-art clinical review. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2017; 13:757–777. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S117321

Safety, tolerability, and risks associated with first-and second-generation antipsychotics: a state-of-the-art clinical review. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2017; 13:757–777. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S117321 - ↵

- Cates ME,

- Jackson CW,

- Feldman JM,

- Stimmel AE,

- Woolley TW

. Metabolic consequences of using low-dose quetiapine for insomnia in psychiatric patients. Community Ment Health J 2009; 45(4):251–254. doi:10.1007/s10597-009-9200-0

- ↵

- Carr CN,

- Lopchuk S,

- Beckman ME,

- Baugh TB

. Evaluation of the use of low-dose quetiapine and the risk of metabolic consequences: a retrospective review. Ment Health Clin 2016; 6(6):308–313. doi:10.9740/mhc.2016.11.308

- ↵

- Williams SG,

- Alinejad NA,

- Williams JA,

- Cruess DF

.

Statistically significant increase in weight caused by low-dose quetiapine. Pharmacotherapy 2010; 30(10):1011–1015. doi:10.1592/phco.30.10.1011

Statistically significant increase in weight caused by low-dose quetiapine. Pharmacotherapy 2010; 30(10):1011–1015. doi:10.1592/phco.30.10.1011 - ↵

- Nemeroff CB,

- Kinkead B,

- Goldstein J

. Quetiapine: preclinical studies, pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and dosing. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63(suppl 13):5–11. pmid:12562141

- ↵

- Calabrese JR,

- Keck PE Jr.,

- Macfadden W, et al

. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162(7):1351–1360. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1351

- ↵

- Thase ME,

- Macfadden W,

- Weisler RH, et al

. Efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy in bipolar I and II depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study (the BOLDER II study).

J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26(6):600–609. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000248603.76231.b7

J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26(6):600–609. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000248603.76231.b7 - ↵

- Gareri P,

- Segura-Garcia C,

- Manfredi VG, et al

. Use of atypical antipsychotics in the elderly: a clinical review. Clin Interv Aging 2014; 9:1363–1373. doi:10.2147/CIA.S63942

- ↵

- 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel

. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019; 67(4):674–694. doi:10.1111/jgs.15767

- ↵

- Jin H,

- Shih PA,

- Golshan S, et al

. Comparison of longer-term safety and effectiveness of 4 atypical antipsychotics in patients over age 40: a trial using equipoise-stratified randomization.

J Clin Psychiatry 2013; 74(1):10–18. doi:10.4088/JCP.12m08001

J Clin Psychiatry 2013; 74(1):10–18. doi:10.4088/JCP.12m08001 - ↵

- American Psychiatric Association

. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- ↵

- Roth T

. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med 2007; 3(5 suppl):S7–S10. pmid:17824495

- ↵

- Parsons G

. Dependence on benzodiazepines or Z-drugs: having that conversation. Pharm J 2012; 289:399–402.

- ↵

- Cohrs S,

- Rodenbeck A,

- Guan Z, et al

. Sleep-promoting properties of quetiapine in healthy subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004; 174(3):421–429. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1759-5

- ↵

- Schutte-Rodin S,

- Broch L,

- Buysse D,

- Dorsey C,

- Sateia M

.

Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2008; 4(5):487–504. pmid:18853708

Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2008; 4(5):487–504. pmid:18853708 - ↵

- Wine JN,

- Sanda C,

- Caballero J

. Effects of quetiapine on sleep in nonpsychiatric and psychiatric conditions. Ann Pharmacother 2009; 43(4):707–713. doi:10.1345/aph.1L320

- ↵

- Anderson SL,

- Vande Griend JP

. Quetiapine for insomnia: a review of the literature. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2014; 71(5):394–402. doi:10.2146/ajhp130221

- ↵

- McElroy SL,

- Weisler RH,

- Chang W, et al

. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine and paroxetine as monotherapy in adults with bipolar depression (EMBOLDEN II). J Clin Psychiatry 2010; 71(2):163–174.

doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04942gre

doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04942gre - ↵

- Endicott J,

- Paulsson B,

- Gustafsson U,

- Schiöler H,

- Hassan M

. Quetiapine monotherapy in the treatment of depressive episodes of bipolar I and II disorder: improvements in quality of life and quality of sleep. J Affect Disord 2008; 111(2-3):306–319. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.019

- ↵

- Robert S,

- Hamner MB,

- Kose S,

- Ulmer HG,

- Deitsch SE,

- Lorberbaum JP

. Quetiapine improves sleep disturbances in combat veterans with PTSD: sleep data from a prospective, open-label study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005; 25(4):387–388. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000169624.37819.60

- ↵

- Villarreal G,

- Hamner MB,

- Canive JM, et al

. Efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy in posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173(12):1205–1212. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070967

Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173(12):1205–1212. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070967 - ↵

- Byers MG,

- Allison KM,

- Wendel CS,

- Lee JK

. Prazosin versus quetiapine for nighttime posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in veterans: an assessment of long-term comparative effectiveness and safety. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2010; 30(3):225–229. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181dac52f

- ↵

- Tassniyom K,

- Paholpak S,

- Tassniyom S,

- Kiewyoo J

. Quetiapine for primary insomnia: a double blind, randomized controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai 2010; 93(6):729–734. pmid:20572379

- ↵

- Chow ES,

- Zangeneh-Kazemi A,

- Akintan O,

- Chow-Tung E,

- Eppel A,

- Boylan K

. Prescribing practices of quetiapine for insomnia at a tertiary care inpatient child and adolescent psychiatry unit: a continuous quality improvement project.

J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017; 26(2):98–103. pmid:28747932

J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017; 26(2):98–103. pmid:28747932 - ↵

- Kelly M,

- Dornan T,

- Pringsheim T

. The lesser of two evils: a qualitative study of quetiapine prescribing by family physicians. CMAJ Open 2018; 6(2):E191–E196. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20170145

- ↵

- Gharabawi GM,

- Bossie CA,

- Lasser RA,

- Turkoz I,

- Rodriguez S,

- Chouinard G

. Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) and Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS): cross-scale comparison in assessing tardive dyskinesia. Schizophr Res 2005; 77(2-3):119–128. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.03.008

- ↵

- Mattson ME,

- Albright VA,

- Yoon J,

- Council CL

. Emergency department visits involving misuse and abuse of the antipsychotic quetiapine: results from the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN).

Subst Abuse 2015; 9:39–46. doi:10.4137/SART.S22233

Subst Abuse 2015; 9:39–46. doi:10.4137/SART.S22233 - ↵

- US Department of Justice

- Drug Enforcement Administration, Diversion Control Office

. Title 21 United States Code Controlled Substances Act. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/21cfr/21usc/.

PreviousNext

Back to top

causes, treatment, effective remedies for sleep problems, how to fall asleep without pills

Igor Ivanov

psychotherapist

It happens that people suffer from bad sleep for years and cannot find a doctor who can help.

I experienced insomnia a few years ago. At first, due to long stress, in the evenings he began to fall asleep for two hours, and then he began to get up very early and could not fall asleep after that. As a result, he slept every night for five to six hours, during the day he could not concentrate on work, he could not think well and felt constant fatigue.

To solve the problem, I went to the therapist at the clinic. He prescribed me valerian and motherwort, but this did not affect my sleep in any way. I decided to try melatonin, but it didn't help either. After that, I went to a psychiatrist. In the first few months, the doctor prescribed 10 different drugs for me, none of which worked. In total, during the treatment, I took about 25 different prescription and over-the-counter drugs.

I was treated by more than one doctor. Some of the medicines were prescribed by an expensive doctor from one of Moscow’s fashionable clinics of evidence-based medicine. Of all the drugs, only one helped me, but it caused unpleasant side effects, and I refused it. After that, I decided to take up treatment myself and delved into the study of clinical trials and clinical guidelines.

Go see a doctor

Our articles are written with love for evidence-based medicine. We refer to authoritative sources and go to doctors with a good reputation for comments. But remember: the responsibility for your health lies with you and your doctor. We don't write prescriptions, we make recommendations. Relying on our point of view or not is up to you.

But remember: the responsibility for your health lies with you and your doctor. We don't write prescriptions, we make recommendations. Relying on our point of view or not is up to you.

I am a physician and psychotherapist, so I am familiar with the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia not only as a patient and a theorist, but also as a helping specialist. It turned out that none of the drugs prescribed to me by doctors had proven effectiveness in treating insomnia. In addition, I was not given a normal diagnosis and was not offered psychotherapy, which is the therapy of choice in the treatment of insomnia.

Several years of my life turned into a slow torture that could have been prevented if I had the information described in this article. Hope it helps someone save time.

First, I'll tell you what insomnia is and why it occurs.

Prescription drugs for insomnia that my doctors prescribedWhat is insomnia and how does it manifest itself

Insomnia is officially called insomnia, and five conditions must be met to make a diagnosis:

- The person falls asleep much longer than usual, or sleep is easily interrupted and after waking up it is difficult to fall asleep, or sleep feels superficial and there is no feeling of rest after it.

- Sleep disorders occur at least three times a week.

- There is concern about poor sleep and its consequences.

- Poor sleep makes it difficult to work normally and lead an active social life.

- A person has the conditions for a normal sleep: for example, there is no job, because of which you have to sleep at different times every day, and there is no noisy construction going on outside the apartment window.

Draft clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic insomnia in adults — Russian Society of SomnologistsPDF, 395 KB

Insomnia can be acute or chronic. Acute lasts less than three months. It is often caused by stress, and in most cases, sleep returns to normal after it stops. Sometimes brief medication can be helpful.

This article will mainly discuss treatments for chronic insomnia, that is, one that lasts longer than three months.

Why sleep problems occur

Sleep hygiene disorders. A person can lie in bed all day and work in it at the computer. In this case, a person associates a bed not only with sleep, but also with work, which means that it is more difficult to fall asleep in it. If you go to bed every day at different times, for example, due to night shifts at work or frequent flights to different time zones, then the circadian rhythms of the brain that control sleep are disrupted, which also worsens sleep.

A person can lie in bed all day and work in it at the computer. In this case, a person associates a bed not only with sleep, but also with work, which means that it is more difficult to fall asleep in it. If you go to bed every day at different times, for example, due to night shifts at work or frequent flights to different time zones, then the circadian rhythms of the brain that control sleep are disrupted, which also worsens sleep.

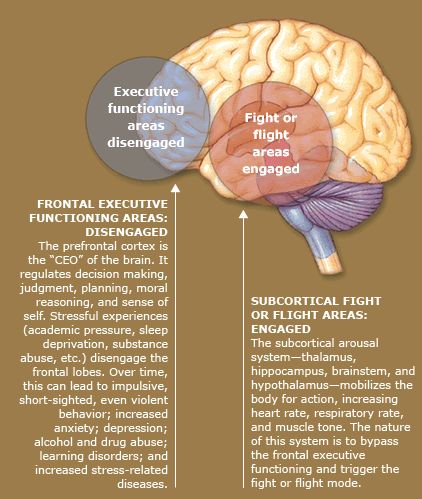

Fear of not getting enough sleep. Before going to sleep, a person is worried that he will fall asleep for a long time, the sleep will be superficial, so he will not get enough sleep. Due to excitement and anxiety, a person really falls asleep for a long time, sleeps poorly and does not get enough sleep. Also, lying in bed at night, he can often look at the clock to estimate how many hours of sleep he has left: if it turns out that there is too little time left, then the anxiety only intensifies.

Mental disorders. For example, a depressed person can lie in bed at night for several hours and replay in his head over and over thoughts about how he was offended by his boss, who was rude for no reason, and what a goat this boss is. Because of these thoughts and experiences, a person cannot fall asleep and, as a result, does not sleep well.

For example, a depressed person can lie in bed at night for several hours and replay in his head over and over thoughts about how he was offended by his boss, who was rude for no reason, and what a goat this boss is. Because of these thoughts and experiences, a person cannot fall asleep and, as a result, does not sleep well.

/bye-depression/

“It felt like a high-security sanatorium”: how much I spent on depression treatment

But poor sleep also worsens the course of mental disorders. For example, if a person is depressed, then depression and insomnia reinforce each other. In such cases, all disorders are treated in parallel.

Other sleep disorders. The cause of insomnia may be another sleep disorder: for example, restless legs syndrome, in which a person in bed feels uncomfortable all the time, and he constantly moves them to remove this discomfort. Because of this, he cannot relax and fall asleep.

Another example is sleep apnea. In this case, a person’s breathing stops during sleep, he begins to choke and wakes up. And so many times a night. Another possible disorder is narcolepsy, in which a person can suddenly and uncontrollably fall asleep during the day, as well as experience bouts of severe muscle weakness, experiencing vivid emotions: for example, while laughing. In such cases, both insomnia and another disorder are also treated in parallel.

Other diseases. Sleep problems can be caused by a wide variety of illnesses, such as chronic pain, hormonal imbalances, or the effects of traumatic brain injury. In such cases, both insomnia and another disorder are also treated in parallel.

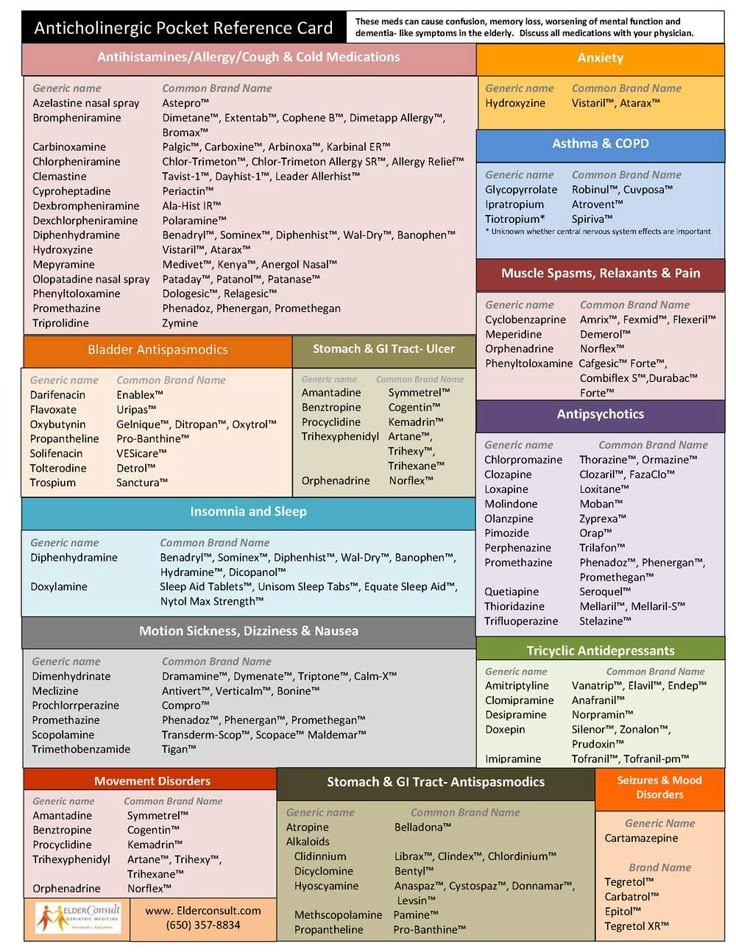

Medicines and psychoactive substances. Some medications, narcotics, and other psychoactive substances interfere with sleep. Sleep problems can be caused by coffee, alcohol, certain drugs, pain relievers, antidepressants, blood pressure medications, nasal decongestants, and asthma medications. If you suspect that you are taking a medication that can affect sleep, then carefully read the instructions for it and consult with the doctor who prescribed it.

If you suspect that you are taking a medication that can affect sleep, then carefully read the instructions for it and consult with the doctor who prescribed it.

Combination of reasons. Often insomnia occurs due to several reasons. For example, a depressed person feels constantly tired: he has neither the strength nor the desire to get out of bed. In order to distract from sad thoughts and get at least some pleasure, he grossly violates sleep hygiene and watches videos on YouTube for half the night without getting out of bed. As a result, his sleep is even more disturbed.

6 things for healthy sleep

Idiopathic insomnia. The word "idiopathic" means that the disorder occurs for an unknown reason. Such insomnia develops in childhood, can last a lifetime, and its cause cannot be established. It is believed that the reason lies in the disruption of the part of the brain responsible for the cycles of sleep and wakefulness. Occurs rarely.

Here is an algorithm that will help you better understand what to do if you find sleep problems. It is published in the manual of the British Association for Psychopharmacology.

Evidence-Based Treatment Consensus for Insomnia, Parasomnia and Circadian Rhythm Disorders - British Association for PsychopharmacologyPDF, 558KB

Who to contact to diagnose insomnia

If you are concerned about the poor quality of your sleep, the first step is to get tested. According to CHI, a psychiatrist treats insomnia. There are also sleep doctors who specialize in sleep disorders, but in Russia, consultations with such doctors are not paid at the expense of compulsory medical insurance.

The doctor explains how long insomnia lasts, how much it worsens the quality of life and what can be caused. If necessary, he prescribes tests: this is necessary to exclude other diseases that can disturb sleep.

/stat-sleeping/

How much do Russians sleep

Another doctor may suggest undergoing a polysomnographic examination. In this procedure, a person sleeps through the night in a clinic with sensors that monitor brain activity, breathing rate and depth, body movements, and other parameters that can affect sleep quality during sleep. This study is recommended in cases where the doctor has a suspicion that sleep problems are caused by another disorder: for example, sleep apnea syndrome.

In this procedure, a person sleeps through the night in a clinic with sensors that monitor brain activity, breathing rate and depth, body movements, and other parameters that can affect sleep quality during sleep. This study is recommended in cases where the doctor has a suspicion that sleep problems are caused by another disorder: for example, sleep apnea syndrome.

It is also helpful to complete a sleep diary for several weeks. If possible, it is helpful to start keeping a diary before the first visit to the doctor. This will help the doctor better understand what is causing the problem and how to deal with it.

In this diary, you need to note the time of going to bed, the duration of falling asleep, the number of nightly awakenings, the time of the final awakening, the duration of sleep during the day, the total sleep time per night, and a number of other parameters.

I used to keep a sleep diary, it helped me keep track of the effects of the medications I was taking. In the course of keeping a diary, it was difficult to fix the exact time of falling asleep and waking up, but a fitness tracker helped with this.

In the course of keeping a diary, it was difficult to fix the exact time of falling asleep and waking up, but a fitness tracker helped with this.

Many fitness trackers and smartwatches have a sleep and wake time tracking feature. This can be handy for filling out a diary. Some of them also track sleep phases, but studies show that this feature usually does not work well - you should not focus on such data.

The Quantified Scientist is a YouTube channel that tests the accuracy of wearable devices, including sleep phase tracking

I created a diary template in a Google spreadsheet. You can copy it to yourself. In the second sheet of the table, as an example, the first few lines are filled inWho should be contacted in case of sleep problems

Viktor Lebedev

psychiatrist

Usually, the path of a patient with sleep disorders begins with a local therapist who complains about problems with sleep. This is the most accessible specialist in the state system of medical care. Usually, the doctor prescribes a tranquilizer to correct insomnia, such as phenazepam. In some cases, he writes a prescription for antidepressants, say, amitriptyline, or Z-drugs - zopiclone. The appointment of antipsychotics - for example, quetiapine in small doses - is exotic for this link of care.

Usually, the doctor prescribes a tranquilizer to correct insomnia, such as phenazepam. In some cases, he writes a prescription for antidepressants, say, amitriptyline, or Z-drugs - zopiclone. The appointment of antipsychotics - for example, quetiapine in small doses - is exotic for this link of care.

The problem is that the level of knowledge of the local therapist and the duration of the appointment usually do not allow understanding the condition of a person with insomnia. For this reason, many quite quickly send the patient for a consultation with a neurologist, psychiatrist or psychotherapist. These specialists are already better able to understand what is happening with the patient.

Many psychiatric and neurological disorders can have sleep disturbances among their symptoms, so these brain doctors should be the first people an insomniac goes to. In large cities there are doctors - usually neurologists - with specialized training in somnology. If it is possible to get an appointment with him, then this is the best option.

How to treat insomnia

If insomnia has started recently, it makes sense to wait and not start treatment. In many cases, it goes away on its own. If the quality of life is significantly reduced due to poor sleep, then the doctor may prescribe a short course of drugs. This is described in more detail below in the section on drug therapy.

Previously, it was believed that if insomnia is caused by a mental disorder or a somatic disease, then it is necessary to treat this particular disease, and to conduct a separate therapy for insomnia only if it significantly reduces the quality of life.

There is now a consensus among insomnia researchers that chronic insomnia should be treated in the same way regardless of its cause. If, besides it, there is some kind of disease that reduces the quality of sleep, including mental, then it must be treated in parallel with insomnia.

Approaches to the treatment of insomnia

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia If insomnia lasts longer than three months and there are no objective causes for poor sleep, such as medication, loud noise at night, too high or too low temperature at night, then the first recommendation is cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, or KPT-I.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis - Annals of Internal Medicine article

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a meta-analysis of long-term effects in controlled trials - article in Sleep Medicine Reviews

Cognitive and behavioral methods treatment of insomnia: a meta-analysis - article in the journal Sleep Medicine Reviews

The effect of psychotherapy is fixed long after its completion. The effect of the drug, on the contrary, ends after stopping the intake, which means that in some cases, medications must be taken for years to maintain normal sleep. And the long-term use of many drugs is little studied, we know little about the consequences of such therapy. At the same time, a course of psychotherapy can, in principle, eliminate the need to take medication.

According to clinical studies, CBT-I speeds up falling asleep by about 20 minutes and significantly reduces night awakenings, a person stays in bed for 30 minutes less after waking up. The subjective quality of sleep also improves significantly compared to the control group of people who did not receive therapy.

The subjective quality of sleep also improves significantly compared to the control group of people who did not receive therapy.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy has two components: Cognitive Therapy, i.e. thinking change, and Behavioral Therapy, i.e. behavior change. I will first list the behavioral approaches, and then move on to the cognitive one.

Sleep hygiene. There are quite a few recommendations on sleep hygiene, they depend on how exactly it is violated in a particular person. From the beginning of therapy, it is also necessary to start keeping a sleep diary, which was discussed above: it can help to see some violations of sleep hygiene.

Here are some examples of recommendations.

Avoid strenuous exercise and stimulants two hours before bed: for example, coffee and alcohol impair sleep quality.

Avoid bright light two hours before bedtime, especially light from TV, computer and smartphone screens. Blue light from these sources is perceived by our brain as daylight, which disrupts the sleep-wake cycle. Also, all popular operating systems for computers and smartphones have the function of blocking blue light from the screen in the evening and at night. For the same purpose, sometimes they offer to buy glasses that do not let the blue light through.

Blue light from these sources is perceived by our brain as daylight, which disrupts the sleep-wake cycle. Also, all popular operating systems for computers and smartphones have the function of blocking blue light from the screen in the evening and at night. For the same purpose, sometimes they offer to buy glasses that do not let the blue light through.

Effects of light on human circadian rhythm - systematic review in International Chronobiology

Although the production of melatonin, the hormone that regulates sleep and wake cycles, is indeed reduced by blue light, and the recommendation to wear special glasses appears in a large number of sleep hygiene guidelines, the scientific evidence supporting the effectiveness of such glasses in the treatment of insomnia is still not enough.

Remove the clock from the room. If a person is nervous thinking about how many hours he will sleep today, he will start constantly looking at the clock, which will only increase his feelings.

Go to bed and get up at the same time. Our body has a built-in biological clock that keeps track of when we should fall asleep and wake up. They adjust other body functions to this mode, and as a result of their work, the quality of sleep increases. Therefore, if a person constantly lies down and gets up at different times, then this in itself worsens the quality of sleep.

For example, when I was struggling with my insomnia, I found myself sitting in bed with my phone until late when I could not fall asleep for a long time. Sometimes I looked at the clock on the wall to check how much sleep I had left. When I noticed these sleep hygiene violations, I removed the clock from the room and developed a rule: no phone in bed.

My blue light blocking glasses. At the time of writing, there is not enough scientific evidence to prove their effectiveness If a person has not violated sleep hygiene or the implementation of these recommendations did not help, then they move on to the next stage: stimulus control.

Stimuli control. A person should associate a bed only with sleep and sex. To achieve this, there are several techniques. For example, if a person lies in bed for two hours every night and cannot fall asleep, he gets used to the fact that two hours pass between going to bed and falling asleep.

"Sleep Nii" is a boring podcast that reads the license agreements of various services.

Psychotherapy seeks to break the habit of lying in bed for hours without sleep. If a person goes to bed and cannot fall asleep for half an hour, he is advised to get up and start doing something boring: for example, listen to an uninteresting podcast, and return to bed when he wants to sleep.

Also, to reduce the time for falling asleep, a person is asked to go to bed not at a fixed time at which he is used to, but when he wants to sleep.

Sleep restriction. If the previous tactic did not help, then the next step is to limit sleep. Among other things, the sleep diary records what time a person goes to bed, when he falls asleep, what time he wakes up and when he gets up. From these data, you can find out, for example, that a person goes to bed at midnight, falls asleep around three in the morning, wakes up at eight in the morning and gets up at nine in the morning. Thus, every night he spends nine hours in bed, but sleeps only five of them.

From these data, you can find out, for example, that a person goes to bed at midnight, falls asleep around three in the morning, wakes up at eight in the morning and gets up at nine in the morning. Thus, every night he spends nine hours in bed, but sleeps only five of them.

Then the time in bed is specially limited by the time of sleep: in our example, five hours. That is, at the moment when a person goes to bed, he sets the alarm so that it rings exactly in five hours. If after a week of such a regime a person begins to fall asleep quickly and does not lie in bed after waking up, then the time in bed increases by 20-30 minutes, and in this regime the person sleeps for the next week. This gradual increase in sleep time continues until the person begins to get enough sleep.

With the help of this exercise, an attempt is made to eliminate the habit of lying in bed without sleep for a long time, to accustom a person to fall asleep quickly and not to lie in bed after waking up. This method sometimes frightens patients. They already sleep little, they suffer, and they are offered to sleep even less, which is alarming.

This method sometimes frightens patients. They already sleep little, they suffer, and they are offered to sleep even less, which is alarming.

It's hard at first, but many people who have gone through psychotherapy end up saying it was the most effective remedy. If a person is completely afraid to use this method, then he has milder and less terrible modifications.

Important: This technique is not suitable for everyone. In bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and a number of other disorders, sleep restriction can worsen the condition, so it should only be used under the guidance of a specialist.

Cognitive therapy. Before going to sleep, a person may have disturbing thoughts. Often these are thoughts caused by the fear of not getting enough sleep: “I have an important presentation tomorrow, and if I don’t get enough sleep, I will perform terribly. Hell, my alarm goes off in seven hours, which means I won't get enough sleep. What if I can't sleep for another hour? It will be a disaster. " As a result, a person is even more nervous and cannot fall asleep.

" As a result, a person is even more nervous and cannot fall asleep.

The therapist helps assess the realism of these thoughts, as well as the client's beliefs that cause these thoughts. For example, a person may have a belief that if he does not get enough sleep, then the next night he needs to go to bed early. As I mentioned earlier, this can be harmful, as it will take longer for a person to fall asleep.

/psychotherapy-search/

How to choose a psychotherapist

Also, a person may think that plans will go awry even if he does not get enough sleep. For example, if he has planned a meeting with friends and is afraid of not getting enough sleep, then on the night before the meeting he is more worried than usual, and when he feels sleepy in the morning, he urgently cancels the meeting.

In reality, it may turn out that it was far from always worth canceling it: the person did not get enough sleep, but the meeting with friends would still go well.

It often turns out that people are afraid of what is actually not so scary. Psychotherapy allows you to see these irrational fears and reduce them.

Relaxation techniques. This is a set of techniques that reduce emotional and physical stress, such as meditation or progressive muscle relaxation. They help to relax before bed for people who have difficulty falling asleep.

Video instruction for progressive muscle relaxation

Relapse prevention. If therapy has significantly improved sleep, then the therapist discusses with the client what situations in the future may lead to the return of insomnia, by what signs it will be possible to understand that it is time to solve the problem, and how exactly the person can correct sleep on his own.

CBT-I, like any other method, does not help everyone. However, in my psychotherapeutic practice there are clients who have been suffering from insomnia for years and have lost hope of correcting the situation, but thanks to psychotherapy they return to normal life.