Schizophrenia auditory hallucination

Auditory Hallucinations - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf

Continuing Education Activity

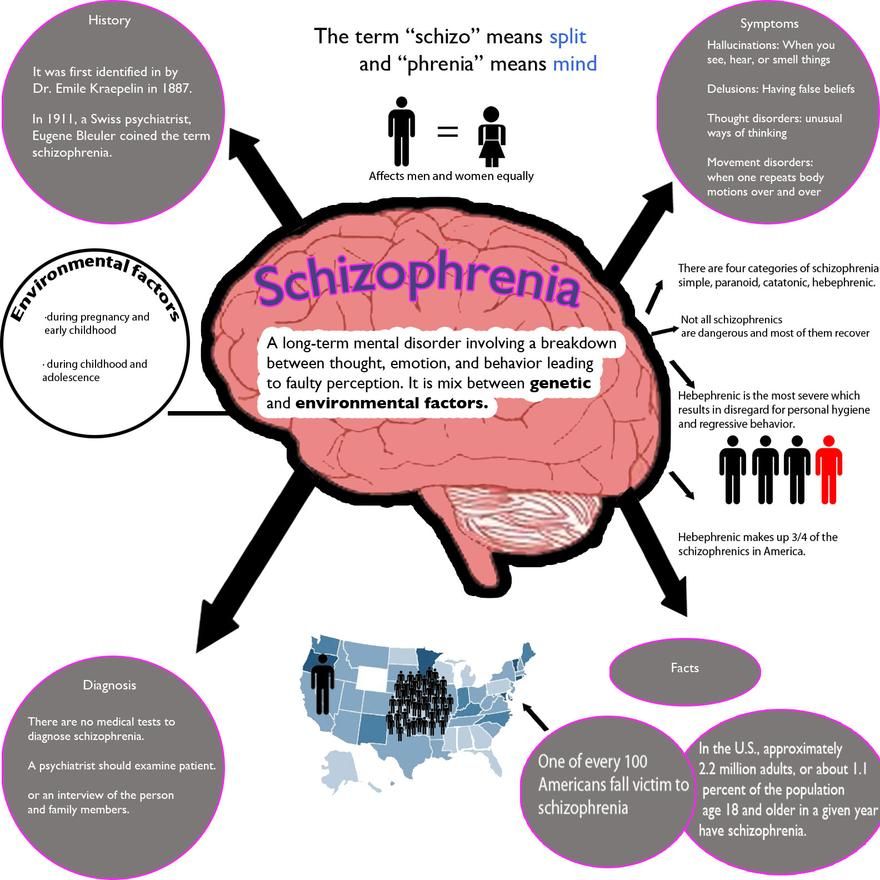

Auditory hallucinations are the sensory perceptions of hearing noises without an external stimulus. This symptom is particularly associated with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders but is not specific to it. This activity provides an overview of the current understanding of auditory hallucinations in terms of etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment options, with further explanation of approaches to enhance the interprofessional team's integrity in improving the outcome of individuals with this condition.

Objectives:

Review the etiology of auditory hallucinations.

Describe the pathophysiology of auditory hallucinations.

Outline the management options of auditory hallucinations.

Summarize the interprofessional team strategies for enhancing care coordination and improving patient outcomes.

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Introduction

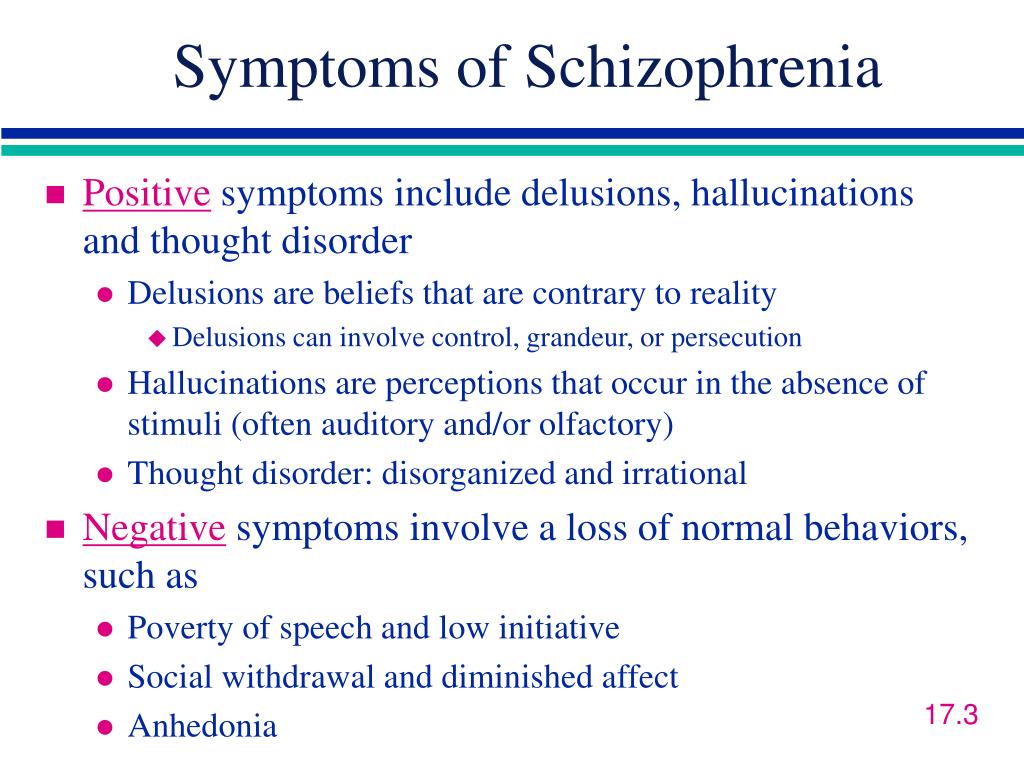

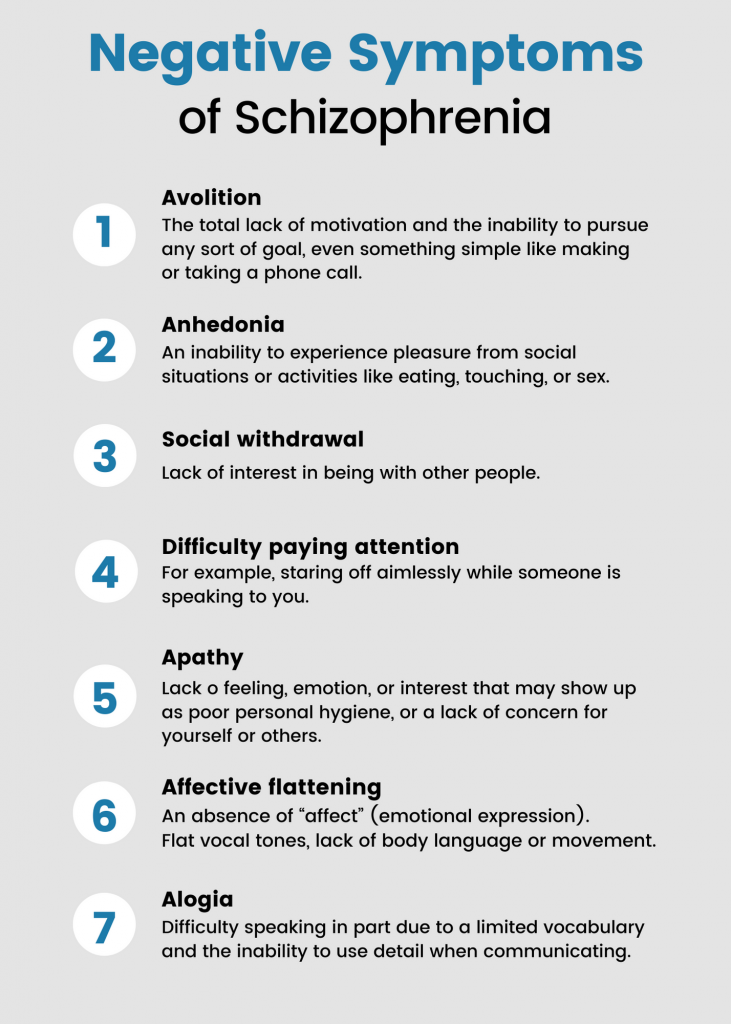

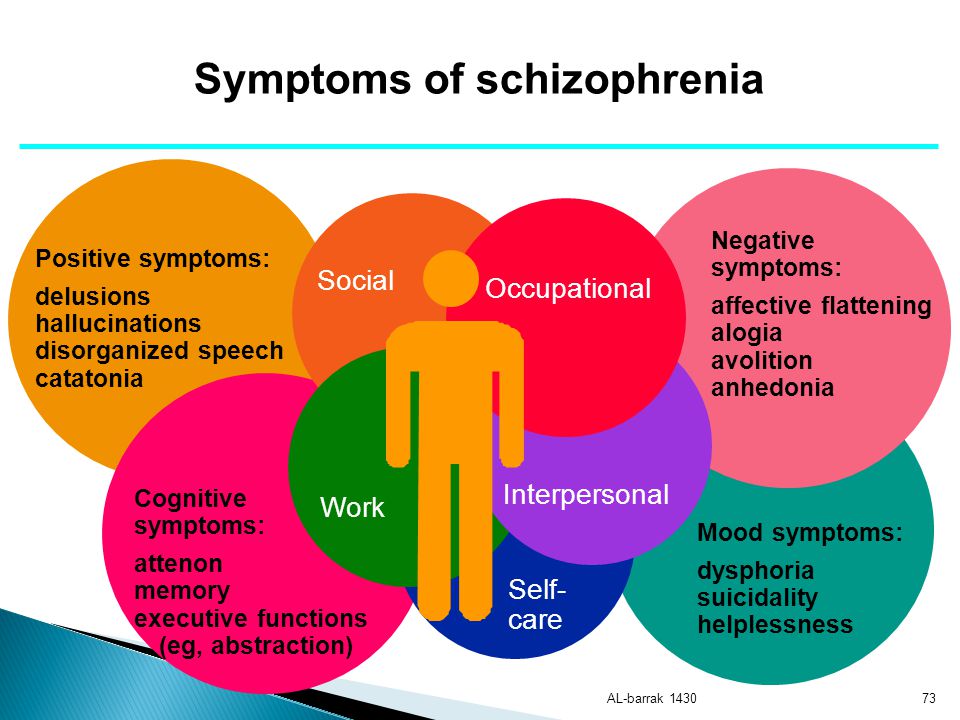

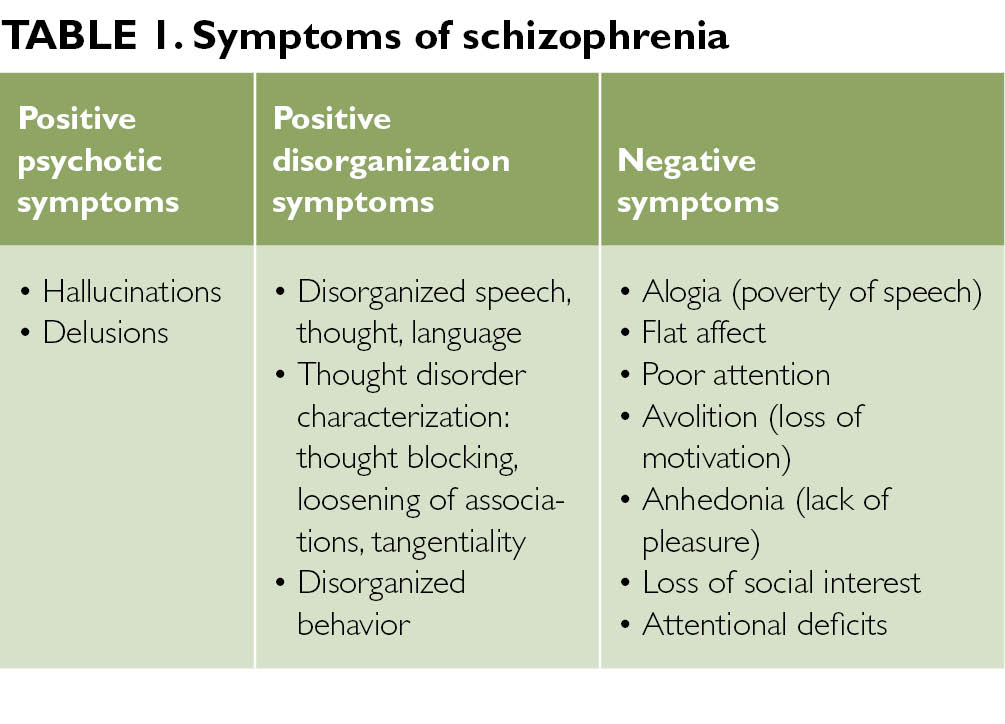

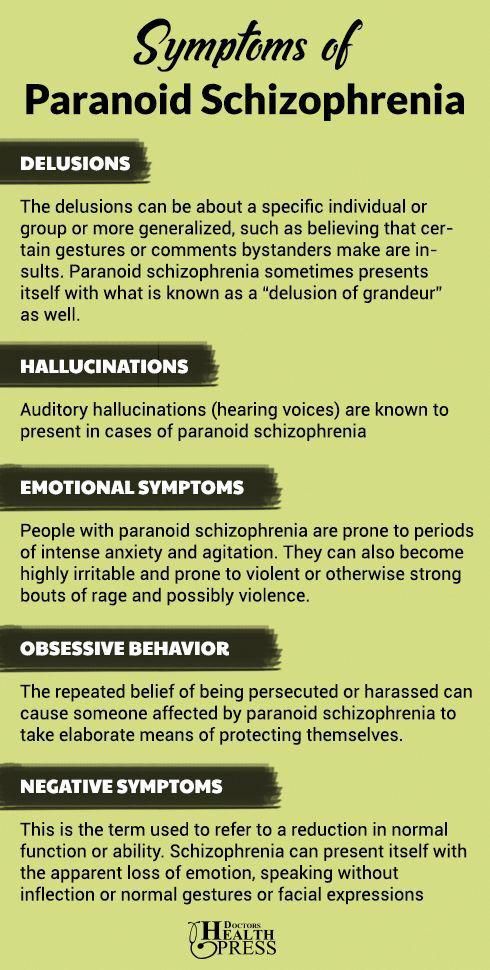

Auditory hallucinations, or paracusias, are sensory perceptions of hearing in the absence of an external stimulus. Auditory hallucinations can refer to a plethora of sounds; however, when the hallucinations are voices, they are distinguished as auditory verbal hallucinations. This specific subset of paracusias is particularly associated with schizophrenia but is not specific to it. Nonpsychotic disorders associated with auditory verbal hallucinations are affective, trauma-related, substance-related, and neurological disorders.[1] These voices can be distressful when they are threatening, derogatory, commanding, or haunting, affecting an individual's social and occupational functioning. Fortunately, paracusias respond well to the administration of psychotropic medications.

Etiology

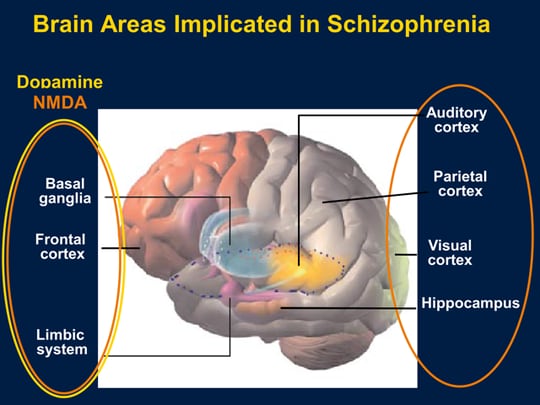

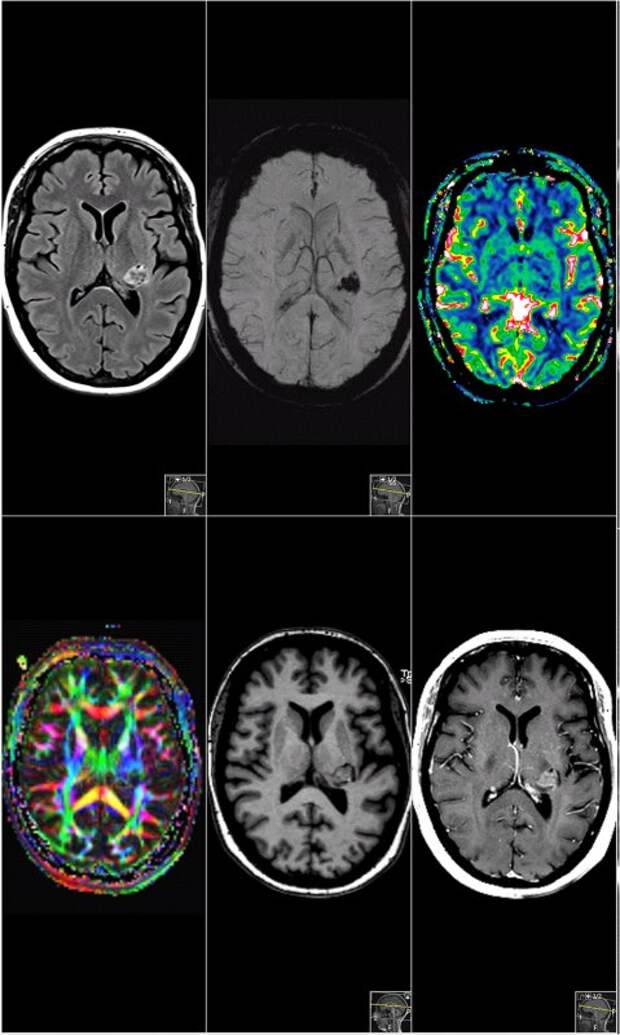

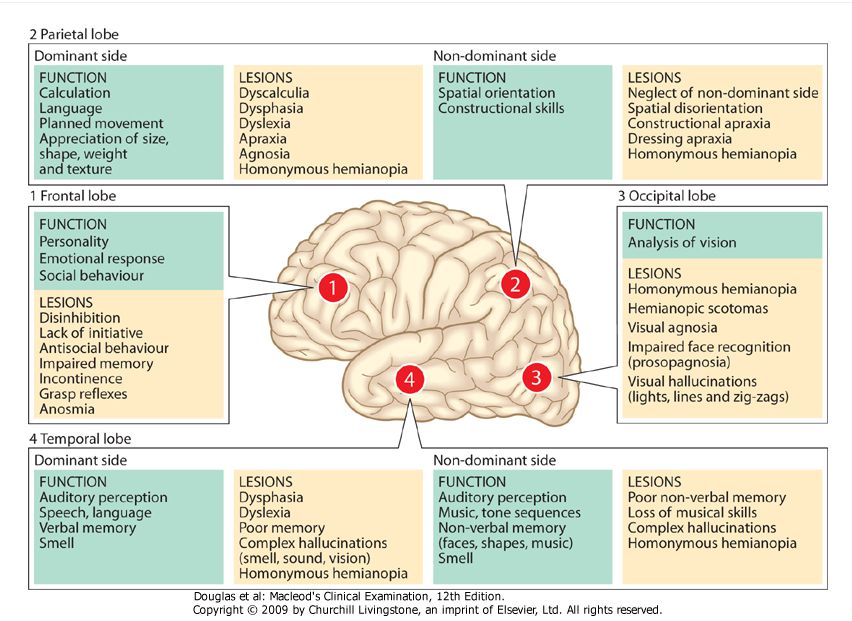

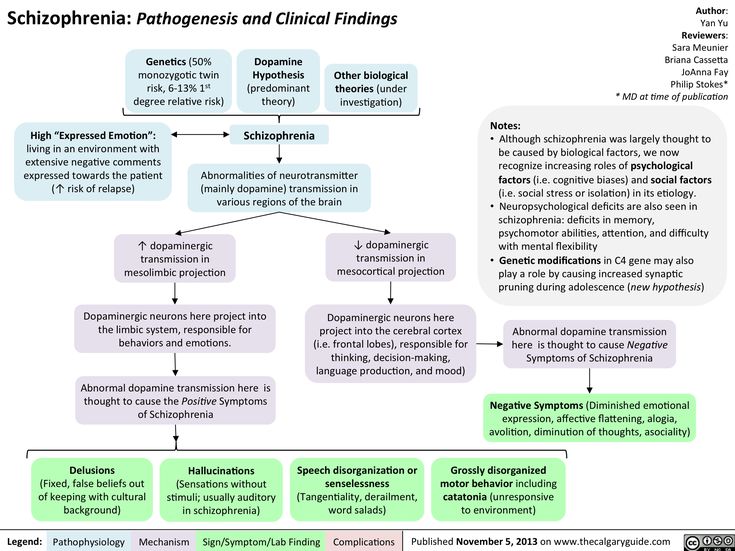

Because auditory hallucinations manifest in a variety of disorders, the etiology is thought to be heterogeneous. Hallucinations most often precipitate in the setting of psychosis. Imaging studies--PET and fMRI--of patients with schizophrenia demonstrate increased activity in the striatal and thalamic subcortical nuclei, paralimbic regions, and hypothalamus. Further analysis reveals deficits in left temporal lobe functioning.[2][3] Further consideration has been placed on aberrant glutamatergic transmission, which coincides with the hypo-functioning glutamate receptor hypothesis of psychosis.

Imaging studies--PET and fMRI--of patients with schizophrenia demonstrate increased activity in the striatal and thalamic subcortical nuclei, paralimbic regions, and hypothalamus. Further analysis reveals deficits in left temporal lobe functioning.[2][3] Further consideration has been placed on aberrant glutamatergic transmission, which coincides with the hypo-functioning glutamate receptor hypothesis of psychosis.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of auditory hallucinations in the general population ranges from 5 to 28%.[4] Auditory hallucinations are most prevalent in patients who have psychosis.[5] They are observed in 75% of individuals with schizophrenia, 20-50% of individuals with manic depression, 10% of individuals with major depression, and 40% of individuals with PTSD.[6]

In children and adolescents, the prevalence is 9% and 5 to 16%, respectively.[7][8] It most often manifests in children in the setting of conduct disorder, migraine, and anxiety.[9][10][11] The remission rate of auditory hallucinations in adolescence ranges from 3 to 40% each year. [12]

[12]

Pathophysiology

The precise mechanism by which paracusias occur remains elusive. However, several postulations have been suggested.[13]

fMRI findings have demonstrated spontaneous activation of the auditory network, consisting of the left superior temporal gyrus, transverse temporal gyri (Heschl's gyri), and the left temporal lobe.[14][15]

A neurocognitive model called the VOICE model has been offered, which attributes the paracusias to an unbalanced bottom-up limbic hyperexcitation mismatched against a hypoactive prefrontal inhibitory system.[16] This mismatch results in the spontaneous firing of sensory neurons in the absence of appropriate inhibitory mechanisms.

Some data suggest that the thalamus-amygdala pathways are activated, thereby processing an emotional response to the auditory hallucinations, further proved by another study detecting choline and N-acetyl aspirate ratio abnormalities in the thalamus.[13][17]

At a neurochemical level, of particular importance are dopamine (D2) and serotonin (5HT2a) receptors. Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated increased D2 receptor occupancy in the striatal system and 5HT2a receptor occupancy in the caudate nucleus.[18]

Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated increased D2 receptor occupancy in the striatal system and 5HT2a receptor occupancy in the caudate nucleus.[18]

History and Physical

Paracusias may be perceived as coming through the ears, on the surface of the body, in their mind, or anywhere in external space. They can occur as frequently as daily or as an isolated episode. The quality of the hallucination is also variable. They can be loud or soft. As mentioned previously, paracusias can be incoherent sounds or distinct voices. Depending on the level of insight maintained by the patient, the paracausias can be greatly impairing. Auditory hallucinations most often manifest in the setting of formal thought disorders; however, they can present in protean settings, as well.[19]

When associated with schizophrenia, paracusias vary according to the stage of the illness. In the late prodromal stages, inner speech becomes more objectified and externally perceived.[20]

Evaluation

The evaluation of paracusias consists of a general psychiatric interview that includes details regarding the evolution of the hallucinations, triggering factors, psychiatric review of systems, past psychiatric diagnosis, history of substance use, family history of psychiatric illness, and history of trauma.

Additionally, a detailed medical history and medication regimen--including over-the-counter supplements--should be obtained.

The clinician's most valuable assessment tool is the mental status examination, addressing mood, affect, appearance, behavior, speech, thought content, thought process, insight, and judgment. Furthermore, determination of the presence of 'first-rank' or 'Schneiderian' hallucinations--voices speaking to each other or narrating one's thoughts aloud--should be completed. The clinician should determine if the hallucinations are temporally associated with affective disturbances and, if so, if they are congruent with mood. To further assess the patient's safety and the safety of others, the patient should be asked to elaborate on whether the hallucinations command him or her to perform certain acts.

Lastly, organic medical etiologies should be ruled out using analysis and neurologic imaging. Laboratory analysis includes:

Urine toxicology

Complete blood count with differential

Vitamin B12 and D levels

Renal function test

Serum electrolytes

Hepatic function test

Blood alcohol

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be considered if organic brain abnormalities are considered in the differential diagnoses.

EEG for a seizure disorder

Treatment / Management

First, any underlying organic disease should be addressed and treated accordingly. If the organicity acted in the capacity of the inciting precipitant then the paracusias should ostensibly resolve as the disease dissipates.

However, if the hallucinations precipitated as a result of a primary psychiatric disorder then neuroleptics become the mainstay of treatment. Neuroleptics, colloquially referred to as antipsychotics, are a class of psychotropics that block dopamine receptors. The putative mechanism by which neuroleptics mitigate auditory hallucinations is by blocking dopamine D2 receptors in the mesolimbic tract. The initial subclass of neuroleptic's, the first generation antipsychotics (FGA), primary mechanism of action is the antagonism of the D2 receptor, whereas, the subsequent second-generation antipsychotics (SGA) act more indiscriminately on an expanded array of receptors.[21] Generally, debates between administering first or second-generation antipsychotics are resolved by considering the side effect profiles of the specific medications under consideration. [21]]

[21]]

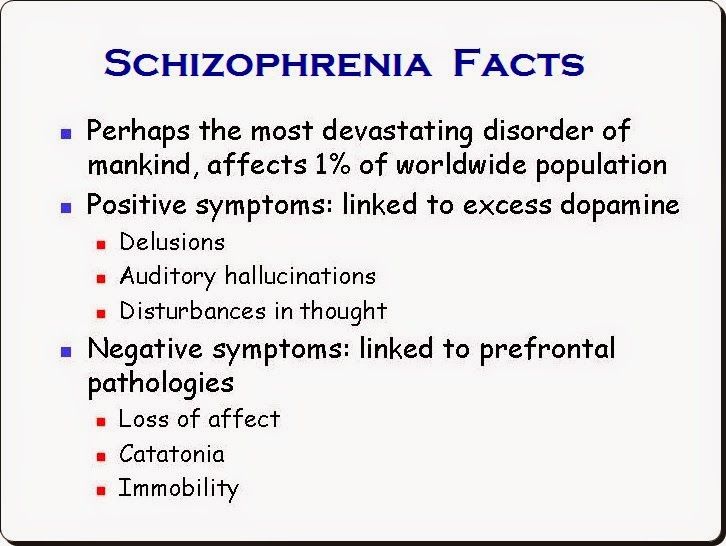

Independent of the subclass chosen, the perceptual anomalies should abate within a week of initiation of the psychotropic. Sometimes these auditory aberrations can persist and require the administration of an additional neuroleptic in conjunction with the first. In the event that the hallucinations still continue to demonstrate resistance--following the administration of 2 antipsychotics--the clinician is encouraged to switch to clozapine, an SGA. Clozapine has shown to be the most efficacious antipsychotic for the treatment of positive symptoms of schizophrenia--delusions, hallucinations, disorganized behavior, and speech--however, it is also associated with the greatest danger as it can induce blood dyscrasias, specifically agranulocytosis. This neuroleptic requires astute clinical monitoring, with weekly then biweekly blood draws.[21]

If the hallucinations manifest in the setting of affective disorders, such as depression or mania, then corresponding psychotropics should be given, adjunctively (e. g., antidepressants and mood stabilizers, respectively).

g., antidepressants and mood stabilizers, respectively).

Psychotherapy can also be applied in conjunction with pharmacotherapy. The most robustly researched psychotherapeutic modality has been cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT instructs the patient to modify how he or she experiences the paracusias, ultimately offering an improved sense of control over the hallucination. CBT uses Socratic interviewing rather than confrontation, implements reality testing, and can be provided in an individual or group format.[22]

Other treatment approaches include ACT (acceptance and commitment therapy), HIT (hallucination-focused integrative treatment), ATT (metacognitive therapy attention training technique), relating therapy, distraction techniques, and HVN (hearing voices network) self-help group, all strategies to cope better with the voices.

Emerging Treatments

Several studies have shown efficacy in reducing auditory hallucinations using transcranial magnetic stimulation but the evidence is still lacking. [23]

[23]

Differential Diagnosis

To differentiate the causes of auditory hallucinations, it is pertinent to focus on the following:

A detailed medical history along with laboratory analyses and neuroimaging to rule out organic etiologies.

Details regarding substance use (illicit and over the counter), medication profiles, and supplement use to rule out toxic-metabolic causes.[24][25]

Detailed psychiatric family history as many psychiatric illnesses show high heritability.

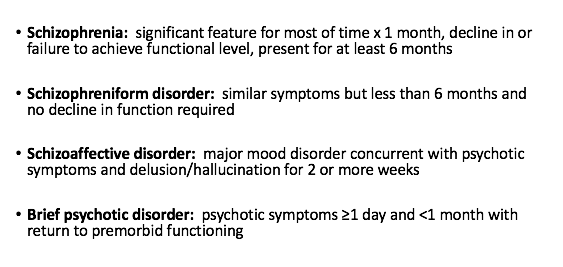

Manifestations of auditory hallucinations can occur in a multiplicity of psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, trauma-related disorders, dissociative disorders, personality disorders, and parasomnias.[26]

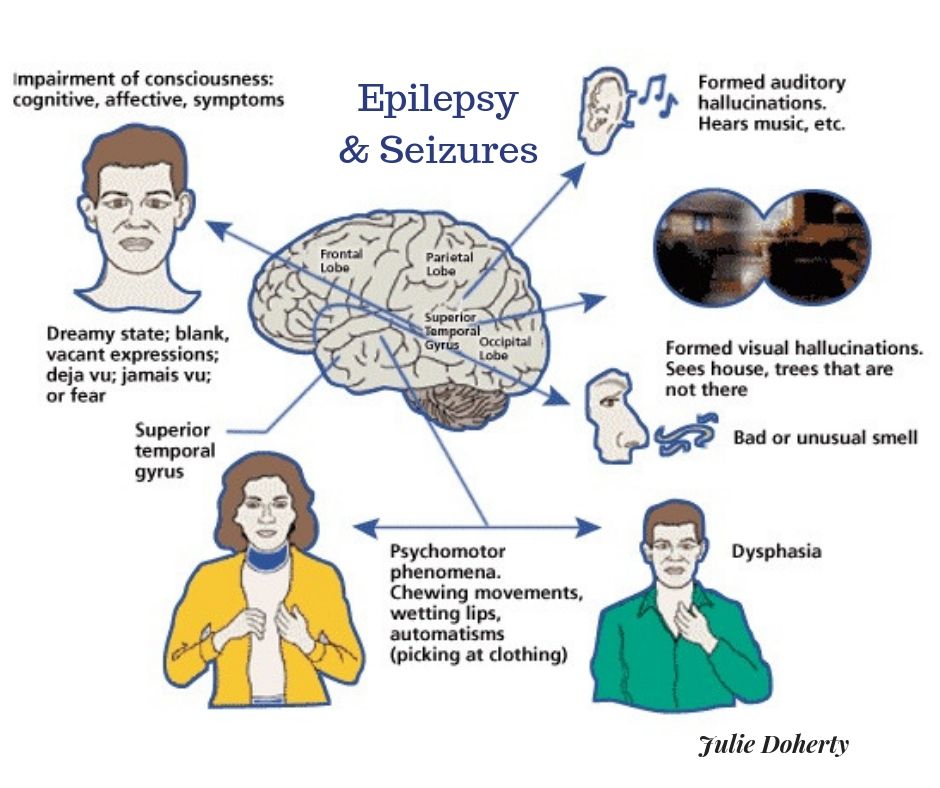

Furthermore, neurological conditions such as tinnitus, cerebral tumors, traumatic brain injury, epilepsy (particularly temporal lobe epilepsy), viral encephalitis, delirium, and cardiovascular events that involve the brainstem regions or areas of temporal, temporoparietal, or occipital pathways can present with auditory hallucinations. [27][28][27]

[27][28][27]

Other organic etiologies include neurodegenerative conditions, conditions that incur damage to the peripheral sensory pathways (e.g., acquired deafness, thyroid dysfunction, nutritional deficiencies), chromosomal abnormalities, autoimmune disorders, and acquired immunodeficiencies.[2][29][30][29][31][2][32]

Research suggests that auditory hallucinations can also precipitate, transiently, in response to conditions of extreme physiological and psychological stress such as dissociative identity disorder, fatigue, and bereavement.[33]

Prognosis

In the event that the etiology is that of an organic nature, the prognosis is contingent upon the underlying disease process. Therefore, the hallucinations should, in theory, resolve as the precipitant resolves. However, when the perceptual anomaly occurs in the setting of a primary psychiatric disorder, the remittance of the paracusias is more independent. Evidence demonstrates that the positive symptoms of schizophrenia respond well to the administration of neuroleptics; however, the actual psychotic disorder does not. Thus, the resolution of the hallucinations does not necessarily indicate the resolution of the underlying thought disorder.[34]

Thus, the resolution of the hallucinations does not necessarily indicate the resolution of the underlying thought disorder.[34]

Generally, factors that increase the risk of poor treatment response include early age of onset, male gender, and multiple inpatient hospitalizations.

Complications

Complications occur when the hallucinations command the patient to hurt himself or others. The paracusias can also be so self-deprecating that they cause the patient to attempt suicide. More common complications result from the side effects of antipsychotics. These can include both short-term and long-term side effects, including extrapyramidal symptoms--dystonia, tardive dyskinesia, parkinsonism--and metabolic syndrome.

Individuals may lack insight and judgment, leading to self-neglect, and may have to be hospitalized involuntarily. Care needs to be taken to build trust and respect with the patients for maintaining regular follow-up even after discharge from hospitals, given a notable high chance of relapse due to non-compliance with medications and appointments.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients and their families need to be educated regarding the significance of compliance with medications. Many patients do not adhere to their medication regimens, are lost to follow up, and end up relapsing and being hospitalized. Severely sick patients should be assigned to an assertive community treatment program while providing treatment, rehabilitation, and support services.

Other support groups focus on destigmatizing mental illness for the family and the individual. Engaging patients in vocational and art therapy can improve self-esteem and help integrate their functioning.

Lastly, educating patients about case management services can assist them by providing coordination between psychiatrists and social workers, keeping up with the appointments, and making home visits.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

There are some limitations in the understanding and strategies within the healthcare system towards auditory hallucinations. Defining the phenomena, suggesting treatment strategies, and providing support are essential. Next, recognizing the gravity of the complications that can occur could prevent self-neglect, suicidal, and homicidal events and minimize medication side effects.

Defining the phenomena, suggesting treatment strategies, and providing support are essential. Next, recognizing the gravity of the complications that can occur could prevent self-neglect, suicidal, and homicidal events and minimize medication side effects.

While a detailed history and mental status examination are paramount, identifying the cause of auditory hallucinations allows the right selection of the management strategies. Antipsychotics are the treatment of choice. Despite the clear-cut strategies, it is important to understand that auditory hallucinations are a sensory perception that will require patience and involvement by an interprofessional team to see results. Hence it is important to raise awareness and education in the inpatient and outpatient staff, customize discharge plans according to the individual with self-management strategies and communicate discharge plans and safety tools with caregivers and case managers.

The outcome of auditory hallucinations depends upon the coordination and the promptness of each caregiver during the care process. As such, it requires the coordinated activities of an interprofessional healthcare team. This team includes clinicians (MDs, DOs, NPs, PAs), specialists, counselors and social workers, nursing staff, and pharmacists. With open communication between the various disciplines, improved outcomes and minimizing adverse events are much more likely. [Level 5]

As such, it requires the coordinated activities of an interprofessional healthcare team. This team includes clinicians (MDs, DOs, NPs, PAs), specialists, counselors and social workers, nursing staff, and pharmacists. With open communication between the various disciplines, improved outcomes and minimizing adverse events are much more likely. [Level 5]

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

References

- 1.

Shinn AK, Wolff JD, Hwang M, Lebois LAM, Robinson MA, Winternitz SR, Öngür D, Ressler KJ, Kaufman ML. Assessing Voice Hearing in Trauma Spectrum Disorders: A Comparison of Two Measures and a Review of the Literature. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:1011. [PMC free article: PMC7050446] [PubMed: 32153431]

- 2.

Waters F, Fernyhough C. Hallucinations: A Systematic Review of Points of Similarity and Difference Across Diagnostic Classes. Schizophr Bull.

2017 Jan;43(1):32-43. [PMC free article: PMC5216859] [PubMed: 27872259]

2017 Jan;43(1):32-43. [PMC free article: PMC5216859] [PubMed: 27872259]- 3.

Miotto P, Pollini B, Restaneo A, Favaretto G, Sisti D, Rocchi MB, Preti A. Symptoms of psychosis in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 2010 Feb 28;175(3):237-43. [PubMed: 20022383]

- 4.

Stanghellini G, Langer AI, Ambrosini A, Cangas AJ. Quality of hallucinatory experiences: differences between a clinical and a non-clinical sample. World Psychiatry. 2012 Jun;11(2):110-3. [PMC free article: PMC3363387] [PubMed: 22654943]

- 5.

Rajkumar RP. The Impact of Childhood Adversity on the Clinical Features of Schizophrenia. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2015;2015:532082. [PMC free article: PMC4539488] [PubMed: 26345291]

- 6.

Choong C, Hunter MD, Woodruff PW. Auditory hallucinations in those populations that do not suffer from schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007 Jun;9(3):206-12. [PubMed: 17521516]

- 7.

Bartels-Velthuis AA, Jenner JA, van de Willige G, van Os J, Wiersma D.

Prevalence and correlates of auditory vocal hallucinations in middle childhood. Br J Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;196(1):41-6. [PubMed: 20044659]

Prevalence and correlates of auditory vocal hallucinations in middle childhood. Br J Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;196(1):41-6. [PubMed: 20044659]- 8.

van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Krabbendam L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med. 2009 Feb;39(2):179-95. [PubMed: 18606047]

- 9.

Askenazy FL, Lestideau K, Meynadier A, Dor E, Myquel M, Lecrubier Y. Auditory hallucinations in pre-pubertal children. A one-year follow-up, preliminary findings. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;16(6):411-5. [PubMed: 17468968]

- 10.

Schreier HA. Auditory hallucinations in nonpsychotic children with affective syndromes and migraines: report of 13 cases. J Child Neurol. 1998 Aug;13(8):377-82. [PubMed: 9721892]

- 11.

Escher S, Romme M, Buiks A, Delespaul P, Van Os J. Independent course of childhood auditory hallucinations: a sequential 3-year follow-up study.

Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2002 Sep;43:s10-8. [PubMed: 12271794]

Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2002 Sep;43:s10-8. [PubMed: 12271794]- 12.

Rubio JM, Sanjuán J, Flórez-Salamanca L, Cuesta MJ. Examining the course of hallucinatory experiences in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2012 Jul;138(2-3):248-54. [PubMed: 22464200]

- 13.

Hugdahl K. Auditory Hallucinations as Translational Psychiatry: Evidence from Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Balkan Med J. 2017 Dec 01;34(6):504-513. [PMC free article: PMC5785654] [PubMed: 29019460]

- 14.

Kompus K, Westerhausen R, Hugdahl K. The "paradoxical" engagement of the primary auditory cortex in patients with auditory verbal hallucinations: a meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neuropsychologia. 2011 Oct;49(12):3361-9. [PubMed: 21872614]

- 15.

Ćurčić-Blake B, Ford JM, Hubl D, Orlov ND, Sommer IE, Waters F, Allen P, Jardri R, Woodruff PW, David O, Mulert C, Woodward TS, Aleman A. Interaction of language, auditory and memory brain networks in auditory verbal hallucinations.

Prog Neurobiol. 2017 Jan;148:1-20. [PMC free article: PMC5240789] [PubMed: 27890810]

Prog Neurobiol. 2017 Jan;148:1-20. [PMC free article: PMC5240789] [PubMed: 27890810]- 16.

Hugdahl K. "Hearing voices": auditory hallucinations as failure of top-down control of bottom-up perceptual processes. Scand J Psychol. 2009 Dec;50(6):553-60. [PubMed: 19930254]

- 17.

Martínez-Granados B, Brotons O, Martínez-Bisbal MC, Celda B, Martí-Bonmati L, Aguilar EJ, González JC, Sanjuán J. Spectroscopic metabolomic abnormalities in the thalamus related to auditory hallucinations in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008 Sep;104(1-3):13-22. [PubMed: 18650068]

- 18.

Hurlemann R, Matusch A, Kuhn KU, Berning J, Elmenhorst D, Winz O, Kolsch H, Zilles K, Wagner M, Maier W, Bauer A. 5-HT2A receptor density is decreased in the at-risk mental state. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2008 Jan;195(4):579-90. [PubMed: 17899021]

- 19.

Klosterkötter J. The meaning of basic symptoms for the genesis of the schizophrenic nuclear syndrome.

Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1992 Sep;46(3):609-30. [PubMed: 1487845]

Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1992 Sep;46(3):609-30. [PubMed: 1487845]- 20.

Sass LA, Parnas J. Schizophrenia, consciousness, and the self. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(3):427-44. [PubMed: 14609238]

- 21.

Pandarakalam JP. Persistent auditory hallucinations and treatment challenges. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2014 Apr;75(4):217-22. [PubMed: 24727961]

- 22.

Chadwick P, Birchwood M. The omnipotence of voices. A cognitive approach to auditory hallucinations. Br J Psychiatry. 1994 Feb;164(2):190-201. [PubMed: 8173822]

- 23.

Hoffman RE, Gueorguieva R, Hawkins KA, Varanko M, Boutros NN, Wu YT, Carroll K, Krystal JH. Temporoparietal transcranial magnetic stimulation for auditory hallucinations: safety, efficacy and moderators in a fifty patient sample. Biol Psychiatry. 2005 Jul 15;58(2):97-104. [PubMed: 15936729]

- 24.

Mosholder AD, Gelperin K, Hammad TA, Phelan K, Johann-Liang R. Hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms associated with the use of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder drugs in children.

Pediatrics. 2009 Feb;123(2):611-6. [PubMed: 19171629]

Pediatrics. 2009 Feb;123(2):611-6. [PubMed: 19171629]- 25.

Lebain P, Juliard C, Davy JP, Dollfus S. [Neuropsychiatric symptoms in preventive antimalarial treatment with mefloquine: apropos of 2 cases]. Encephale. 2000 Jul-Aug;26(4):67-70. [PubMed: 11064842]

- 26.

Fortuyn HA, Lappenschaar GA, Nienhuis FJ, Furer JW, Hodiamont PP, Rijnders CA, Lammers GJ, Renier WO, Buitelaar JK, Overeem S. Psychotic symptoms in narcolepsy: phenomenology and a comparison with schizophrenia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009 Mar-Apr;31(2):146-54. [PubMed: 19269535]

- 27.

Madhusoodanan S, Danan D, Brenner R, Bogunovic O. Brain tumor and psychiatric manifestations: a case report and brief review. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004 Apr-Jun;16(2):111-3. [PubMed: 15328904]

- 28.

Sachdev P, Smith JS, Cathcart S. Schizophrenia-like psychosis following traumatic brain injury: a chart-based descriptive and case-control study. Psychol Med. 2001 Feb;31(2):231-9.

[PubMed: 11232911]

[PubMed: 11232911]- 29.

Hammeke TA, McQuillen MP, Cohen BA. Musical hallucinations associated with acquired deafness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1983 Jun;46(6):570-2. [PMC free article: PMC1027453] [PubMed: 6875592]

- 30.

Davis AT. Psychotic states associated with disorders of thyroid function. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1989;19(1):47-56. [PubMed: 2722405]

- 31.

Kayser MS, Dalmau J. The emerging link between autoimmune disorders and neuropsychiatric disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011 Winter;23(1):90-7. [PMC free article: PMC3086677] [PubMed: 21304144]

- 32.

De Ronchi D, Bellini F, Cremante G, Ujkaj M, Tarricone I, Selleri R, Quartesan R, Piselli M, Scudellari P. Psychopathology of first-episode psychosis in HIV-positive persons in comparison to first-episode schizophrenia: a neglected issue. AIDS Care. 2006 Nov;18(8):872-8. [PubMed: 17012075]

- 33.

Mason OJ, Brady F. The psychotomimetic effects of short-term sensory deprivation.

J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009 Oct;197(10):783-5. [PubMed: 19829208]

J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009 Oct;197(10):783-5. [PubMed: 19829208]- 34.

González JC, Aguilar EJ, Berenguer V, Leal C, Sanjuan J. Persistent auditory hallucinations. Psychopathology. 2006;39(3):120-5. [PubMed: 16531686]

Why Am I Hearing Voices? Auditory Hallucination Causes and Treatment

Written by William Moore

In this Article

- Causes of Auditory Hallucinations

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

Nothing throws you for a loop like when you swear you can hear something that doesn’t seem to have an explanation. If what you heard really doesn’t have a source, it might be an “auditory hallucination.” It can range from a simple sound to hearing music so clearly, it’s hard to believe there’s no band or radio nearby.

Often, what people hear is voices. Sometimes, they’re mean, critical voices. But others might be neutral or even pleasant.

No matter what the sound is, it’s a clear sign to go talk to your doctor. The sooner you do, the quicker you can find out what’s going on and get treated.

The sooner you do, the quicker you can find out what’s going on and get treated.

Causes of Auditory Hallucinations

Mental illness is one of the more common causes of auditory hallucinations, but there are a lot of other reasons, including:

- Alcohol. Heavy drinking can cause you to see things that aren’t there. You might hear things, too, both as you drink or when you quit after you’ve been drinking for many years.

- Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia. You’re more likely to hear things in the later stages of Alzheimer’s. A similar condition called Lewy body dementia can cause it, too. (But it’s more common to see things -- visual hallucinations -- than hear them with this type of dementia.) For some people, the voices seem so real, they talk back to them.

- Brain tumors. Hearing things doesn’t mean you have a brain tumor.

But it could happen when a tumor is in the part of the brain that deals with hearing. You might hear anything from random sounds to actual voices.

But it could happen when a tumor is in the part of the brain that deals with hearing. You might hear anything from random sounds to actual voices. - Drugs. Certain street drugs, like ecstasy and LSD, can make you see and hear things that aren’t there. It can happen while you’re using them or when you quit after using them for a long time.

- Epilepsy. When seizures from epilepsy affect the brain area that processes hearing, you might hear a buzzing sound or voices. In some cases, it warps how you hear things, so they’re not as loud or clear.

- Hearing loss. People with hearing loss in one or both ears may hear anything from odd sounds to music and voices, none of which are really there.

- High fevers and infections. Some infections, like encephalitis and meningitis, can make you hear things, along with the other symptoms. The same is true for high fevers.

- Intense stress. Serious stress, as you might have after going through something traumatic, can cause hallucinations. It’s especially common to hear the voice of a loved one after their recent death.

- Mental illness. Hearing voices is very common with schizophrenia. The voices may seem to come from inside your head or outside, like from the TV. And they could argue with you, tell you what to do, or just describe what’s happening. It can sometimes happen with other mental illnesses as well, including:

- Bipolar disorder

- Borderline personality disorder

- Major depressive disorder

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Schizoaffective disorder

- Migraines. Often, if you get migraines with auras, you see things. But some people hear things instead. Usually, it’s voices. And that may be more likely if you also have depression.

- Parkinson’s disease.

It’s more likely that you would see things that aren’t there when you have Parkinson’s. But in some cases, you hear things from the scenes you’re seeing.

It’s more likely that you would see things that aren’t there when you have Parkinson’s. But in some cases, you hear things from the scenes you’re seeing. - Side effects from medicine. If you begin to hear things once you start a new medicine or your doctor puts you on a higher dose of something you already take, that change could be the reason. It most often affects older adults and gets more likely the more medicines you take.

- Sleep issues. It’s pretty common to hear a sound just as you fall asleep or wake up. And it’s usually not something to see your doctor about. But if you fall asleep randomly (narcolepsy) or have a hard time falling asleep (insomnia), it’s much more likely to happen.

- Thyroid disease. Myxedema is a rare condition where your thyroid is not making enough hormone and your levels get dangerously low. It’s a life-threatening condition that can also make you hear things.

- Tinnitus. Doctors don’t think of the usual ringing or hissing of tinnitus as a hallucination. But this condition can raise your risk. It may be more likely if you also have depression.

Diagnosis

Your doctor will start with your health history and symptoms. You may answer questions like:

- What are you hearing? Voices? Buzzing? Other sounds?

- When did it start?

- Does it tend to happen at certain times, like as you’re falling asleep?

- Do you have any other symptoms when it happens?

- If it’s voices, are they threatening, rude, pleasant, or normal?

- What medicines are you taking?

- Are you using any other drugs?

After that, you’ll get some tests based on what your doctor thinks might be the cause. For example, your doctor might suggest you see a psychiatrist to check for a mental illness.

You could have some tests based on what your doctor thinks might be the cause:

- Electroencephalogram (EEG): This measures electrical signals in your brain, to look for epilepsy.

- Hearing exam: This checks for hearing loss or tinnitus.

The goal is to help your doctor narrow down what might be happening.

Treatment

This depends on what’s causing you to hear things. Sometimes, once you and your doctor solve that problem, the hallucinations go away, or at least may not happen as much.

In some cases, there’s an easy solution. Your doctor may lower the dose of a medicine you take. In others, treatment is more complex, and you may need to try several things to see what works. For example, with an illness like schizophrenia, you might need a mix of medications, therapy, and other care.

Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia

Auditory hallucinations can be a manifestation not only of schizophrenia, but also of a number of other mental disorders. With the exception of acute psychotic states, a person, as a rule, is critical of the voices in his head, that is, he perceives them as something imputed and suffers from their obsession.

The tension that arises in the patient as he tries to silence voices or ignore them by an effort of will can reach the point of physical discomfort and pain. Not to mention that a person suffering from auditory hallucinations is unable to do anything else. It is difficult for him to fall asleep, it is difficult to concentrate on work, homework, or even an easy hobby that usually does not require special concentration. nine0003

In clinical practice, there are a variety of types of auditory hallucinations in patients with schizophrenia: it can be the voices of one or more people, children and adults, male and female, familiar and unfamiliar - there is no special system here. But there is a systematic approach in the treatment of auditory hallucinations, which has been proving its effectiveness over the past 30 years.

In support of people suffering from auditory hallucinations (and not necessarily mentally ill in the usual sense of these words), at 1987 The Hearing Voices Movement was born. It challenges the accepted correspondence between schizophrenia and auditory hallucinations, promotes the social rehabilitation of people suffering from voices in their heads, and combats their stigmatization.

It challenges the accepted correspondence between schizophrenia and auditory hallucinations, promotes the social rehabilitation of people suffering from voices in their heads, and combats their stigmatization.

Among other things, it is to the Hearing Voices movement that patients who hear non-existent voices in their heads owe a therapeutic approach that excludes the active use of medication to combat auditory hallucinations. This approach focuses on cognitive techniques to reduce anxiety and psychological tension when they occur, shift attention to current activities or environmental events, and ultimately reduce the intensity of voices. This treatment is called metacognitive therapy. nine0003

Of particular importance in the course of psychotherapy of auditory hallucinations are meditative techniques that help to focus on productive activities. At the same time, you should not completely abandon medications - pharmacological support with the right dosage and combination of drugs only contributes to the success of cognitive-behavioral voice therapy.

The content of auditory hallucinations can also be very diverse: some voices talk to the person himself, others - to each other, voices can comment on the actions of the person and the environment, they can insistently demand to do what the person would not dare to do of his own free will, including violent acts towards oneself and others. Therefore, it is especially difficult to recognize the presence of auditory hallucinations and tell relatives about their content. Unfortunately, the stereotype that voices in the head are a symptom of a serious mental illness has not been overcome everywhere, and not always even the sincerity of the patient can change the view of his relatives on the problem. However, this is the first thing to be done in the course of treating auditory hallucinations. nine0003

- Schizophrenia

Share:

Hallucinations: A Difference That Matters

Hallucinations are clearly labeled as a psychiatric problem in clinical practice. If a patient has hallucinatory experiences (sound or visual images that are accessible only to the person himself), then this is an unequivocal reason for referral to a psychiatrist's consultation. This is a clinically correct decision, but not every hallucinatory experience experienced by the patient means that he has a chronic mental disorder. nine0003

If a patient has hallucinatory experiences (sound or visual images that are accessible only to the person himself), then this is an unequivocal reason for referral to a psychiatrist's consultation. This is a clinically correct decision, but not every hallucinatory experience experienced by the patient means that he has a chronic mental disorder. nine0003

Hallucinations may occur in short-term mental disorders, such as delirium. Alcoholic delirium or a state of confusion that occurs in elderly patients on the background of somatic diseases is a typical example of such hallucinations. The psychotic experience itself may be one-time and not affect the further picture of the disease. The defining symptoms in the future will be alcohol dependence syndrome (in the case of delirium tremens). In the states of confusion of old age, in the future, the patient can fully recover, without damage to the psyche, or get cognitive impairment. The hallucinations themselves will not be persistent. nine0003

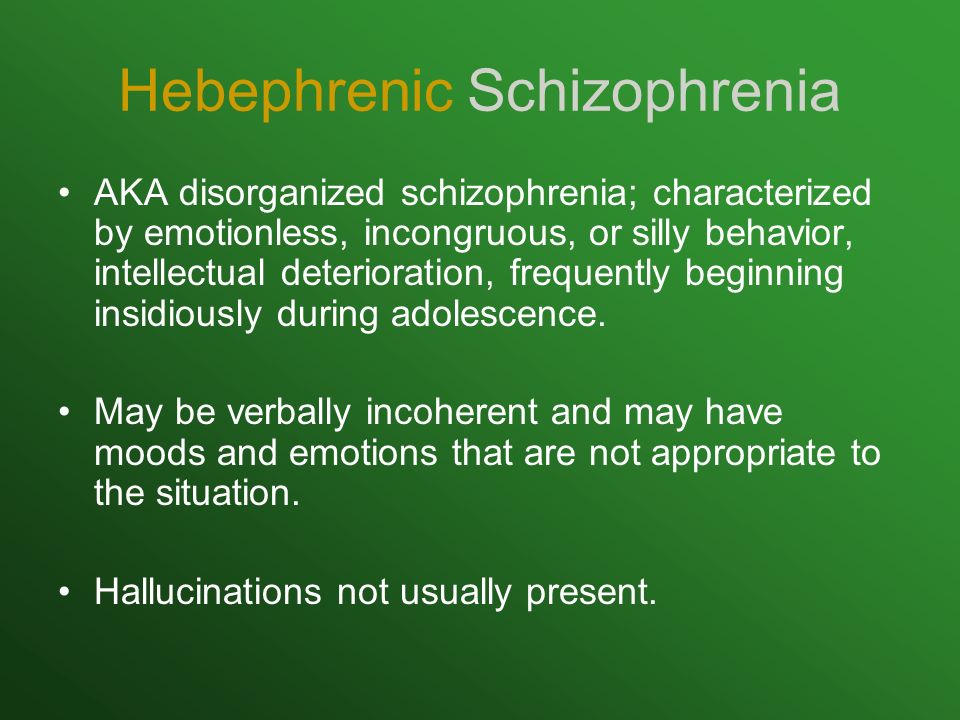

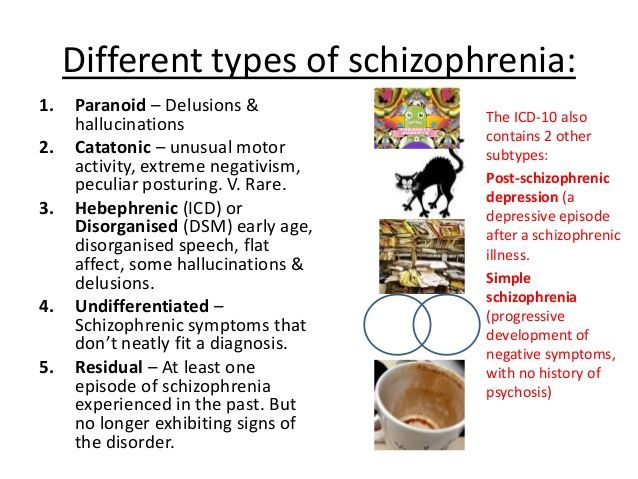

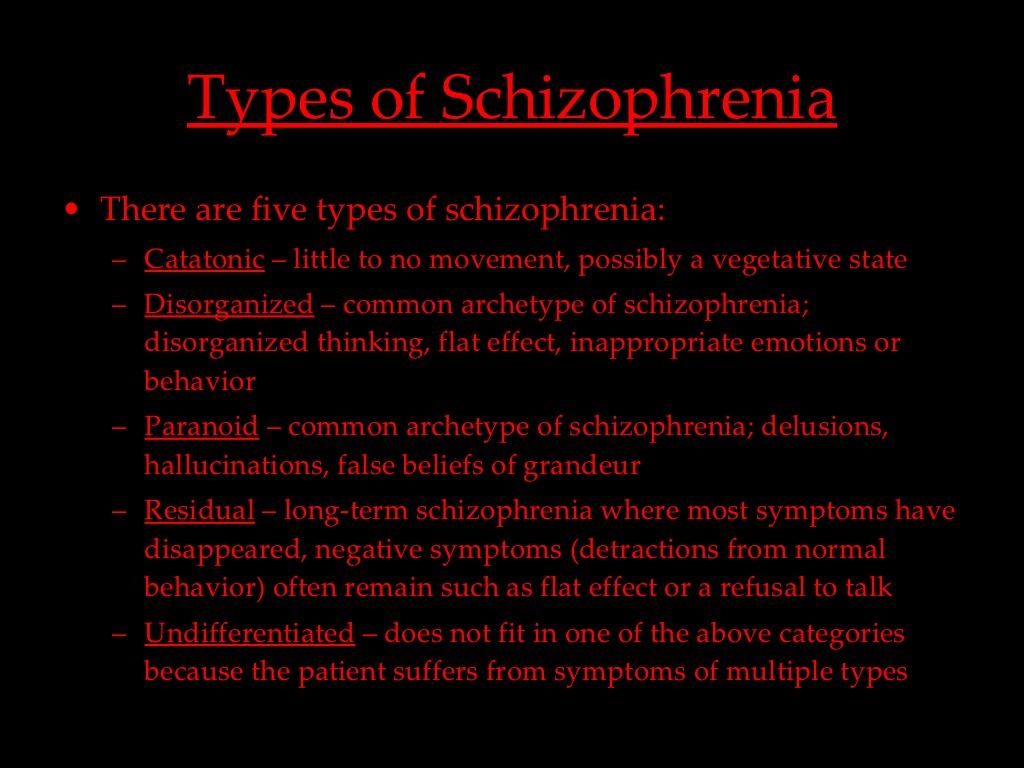

Quite often, auditory hallucinations (“voices in the head”) are labeled as a reliable sign of schizophrenia, a severe chronic mental disorder that often leads to disability. Even a single episode of auditory hallucinosis is qualified by some psychiatrists as a sign of schizophrenia, but this is a gross mistake. First, psychotic experiences in the form of auditory hallucinations are also found in other psychiatric disorders. Patients can experience auditory hallucinations in states of extreme nervous tension, in borderline personality disorder, in schizotypal disorder, in affective disorders (BD, mania or depression) with psychotic inclusions. Secondly, if you pay attention to the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia set out in the ICD-10, then there are clear guidelines for diagnosis. In particular, it is stated that hallucinatory experiences "should be noted throughout the majority of an episode lasting one month or more." Such experiences are described in diagnostic criteria as: nine0018 - hallucinatory voices, which are a current commentary on the patient's behavior or a discussion of it among themselves; other types of hallucinatory voices coming from some part of the body; or

Even a single episode of auditory hallucinosis is qualified by some psychiatrists as a sign of schizophrenia, but this is a gross mistake. First, psychotic experiences in the form of auditory hallucinations are also found in other psychiatric disorders. Patients can experience auditory hallucinations in states of extreme nervous tension, in borderline personality disorder, in schizotypal disorder, in affective disorders (BD, mania or depression) with psychotic inclusions. Secondly, if you pay attention to the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia set out in the ICD-10, then there are clear guidelines for diagnosis. In particular, it is stated that hallucinatory experiences "should be noted throughout the majority of an episode lasting one month or more." Such experiences are described in diagnostic criteria as: nine0018 - hallucinatory voices, which are a current commentary on the patient's behavior or a discussion of it among themselves; other types of hallucinatory voices coming from some part of the body; or

- persistent hallucinations of any sphere, which are accompanied by unstable

or incompletely formed delusions without a clear emotional content.

Other hallucinatory experiences that do not fit these descriptions are not signs of schizophrenia, and their definition as a symptom of schizophrenia is a gross error, leading to overdiagnosis of schizophrenia and errors in the treatment of patients. nine0003

It is also important to separate the hallucinations that are caused by schizophrenia from the hallucinatory experiences that occur during the use of hallucinogens (LSD, psilocybin). The difference arises already at the molecular level, at the level of neurotransmitter systems that are involved in the generation of hallucinatory images in the central nervous system. So, for example, in schizophrenia, hallucinatory experiences are associated with an increase in the intensity of signals in the dopamine system and typical antipsychotics (haloperidol, chlorpromazine), which block dopamine receptors on neurons, do well with them. The use of hallucinogens activates serotonin receptors (in particular, 5-HT2A) and traditional antipsychotics do not block these experiences.