Repetition compulsion examples

Repetition Compulsion: Signs, Causes, and Treatment

Repetition Compulsion: Signs, Causes, and Treatment | Psych Central- Conditions

- Featured

- Addictions

- Anxiety Disorder

- ADHD

- Bipolar Disorder

- Depression

- PTSD

- Schizophrenia

- Articles

- Adjustment Disorder

- Agoraphobia

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Childhood ADHD

- Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder

- Narcolepsy

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- Panic Attack

- Postpartum Depression

- Schizoaffective Disorder

- Seasonal Affective Disorder

- Sex Addiction

- Specific Phobias

- Teenage Depression

- Trauma

- Featured

- Discover

- Wellness Topics

- Black Mental Health

- Grief

- Emotional Health

- Sex & Relationships

- Trauma

- Understanding Therapy

- Workplace Mental Health

- Original Series

- My Life with OCD

- Caregivers Chronicles

- Empathy at Work

- Sex, Love & All of the Above

- Parent Central

- Mindful Moment

- News & Events

- Mental Health News

- COVID-19

- Live Town Hall: Mental Health in Focus

- Podcasts

- Inside Mental Health

- Inside Schizophrenia

- Inside Bipolar

- Wellness Topics

- Quizzes

- Conditions

- ADHD Symptoms Quiz

- Anxiety Symptoms Quiz

- Autism Quiz: Family & Friends

- Autism Symptoms Quiz

- Bipolar Disorder Quiz

- Borderline Personality Test

- Childhood ADHD Quiz

- Depression Symptoms Quiz

- Eating Disorder Quiz

- Narcissim Symptoms Test

- OCD Symptoms Quiz

- Psychopathy Test

- PTSD Symptoms Quiz

- Schizophrenia Quiz

- Lifestyle

- Attachment Style Quiz

- Career Test

- Do I Need Therapy Quiz?

- Domestic Violence Screening Quiz

- Emotional Type Quiz

- Loneliness Quiz

- Parenting Style Quiz

- Personality Test

- Relationship Quiz

- Stress Test

- What's Your Sleep Like?

- Conditions

- Resources

- Treatment & Support

- Find Support

- Suicide Prevention

- Drugs & Medications

- Find a Therapist

- Treatment & Support

Medically reviewed by Lori Lawrenz, PsyD — By Sarah Barkley — Updated on Sep 16, 2022

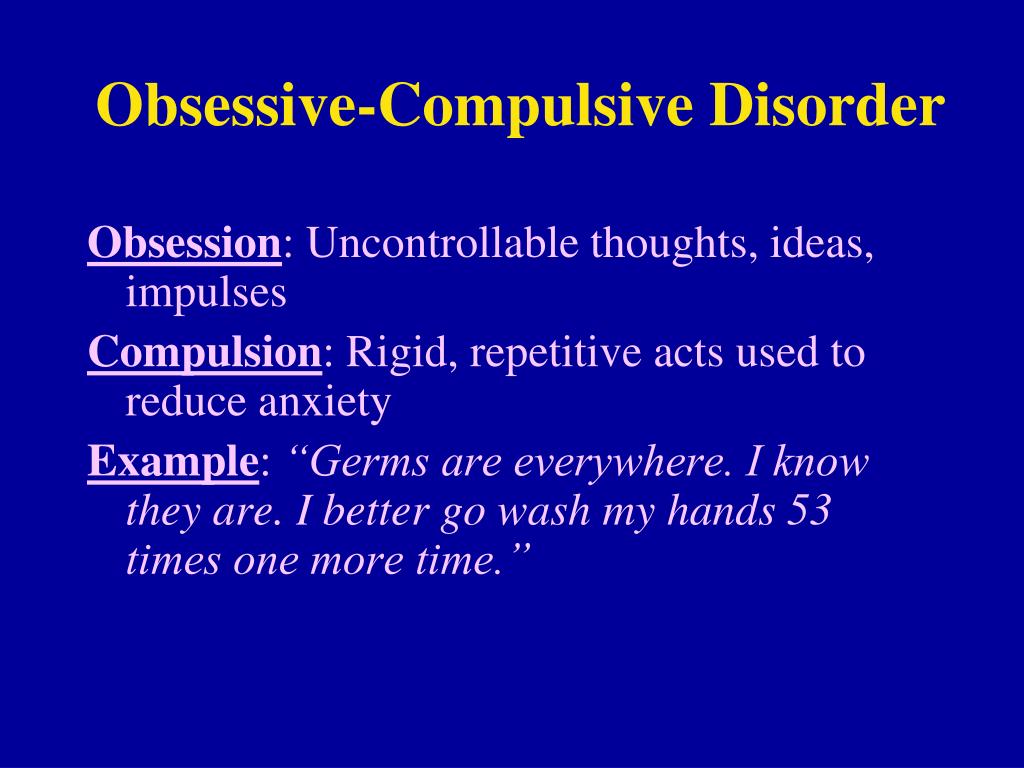

Repetition compulsion involves repeating painful situations that occurred in the past. It’s a way to ease tension from physical or emotional trauma, but it doesn’t always work that way.

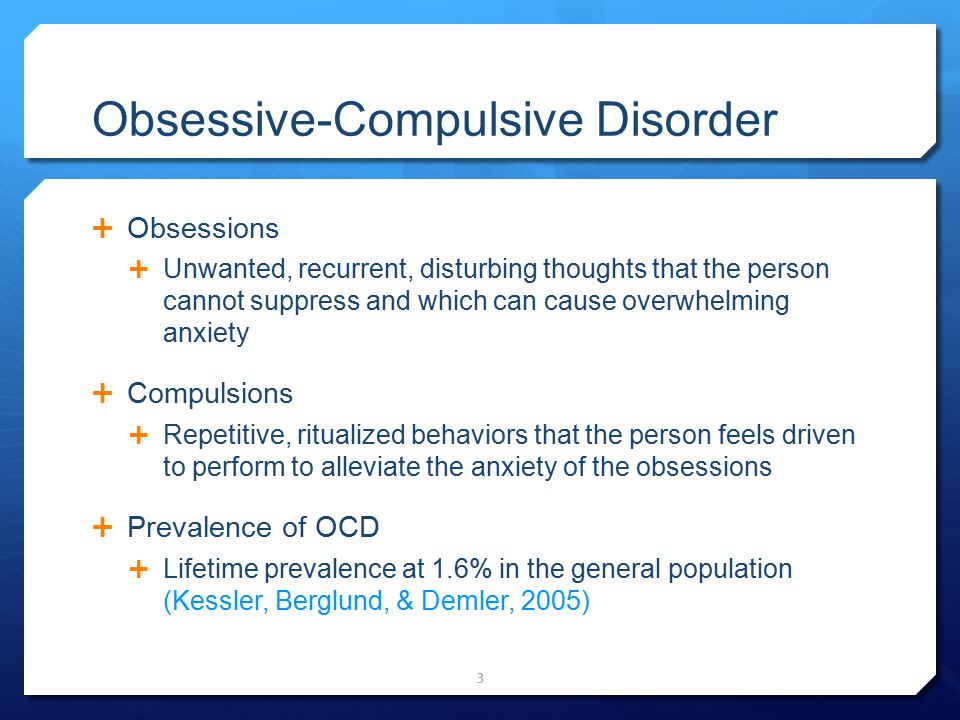

Repetition compulsion or trauma re-enactment involves unconsciously recreating early trauma. Someone experiencing this compulsion repeats emotionally or physically painful situations.

Trauma can include any experience where you feel overwhelmed with hopelessness or fear. You might want to repeat how things used to be in your life, even when it was detrimental to your well-being.

Learning about repetition compulsion can help you determine how to overcome it. You might not realize you’re doing it, and understanding the signs and causes is beneficial. Once you know what you’re dealing with, you can work to treat the compulsion and live a healthier life.

Repetition compulsion is when you unconsciously desire to reenact earlier trauma. However, this compulsion doesn’t help you overcome trauma and could worsen the situation. It occurs when you repeat traumatic behaviors from your past, even when you know it’s not good for you.

What is repetition compulsion in relationships?

Infidelity can relate to repetition compulsion if a child experienced a parent who cheated on their partner. When the child becomes an adult, they may repeat this behavior because they assume it’s normal. They may cheat on their partner or continuously stay with people who betray their trust.

Subconsciously, this behavior may occur as a way to victimize their partner for the pain from their childhood trauma. Staying with a partner who cheats, is emotionally abusive, or is physically abusive could also be a way to handle the trauma they experienced in the past.

According to Freudian thought, narcissism can also play a role in repetition and how it affects relationships. You might want to view the narcissist as loving, possibly because their behavior is familiar to you from your past, causing you to sacrifice your well-being.

The child of a narcissistic parent might feel constant guilt from being blamed for things that aren’t their fault. If this happened to you, you might be more likely to engage in relationships with narcissists as an adult because this dynamic is familiar to you.

If this happened to you, you might be more likely to engage in relationships with narcissists as an adult because this dynamic is familiar to you.

For instance, you might find yourself gravitating towards narcissistic friends, co-workers, bosses, or partners who affect your daily life.

Repetition compulsion might occur from narcissistic trauma as a way to try and fix someone. It can also make you more likely to excuse toxic behavior as a way to rewrite the past. However, it can lead to further trauma and guilt.

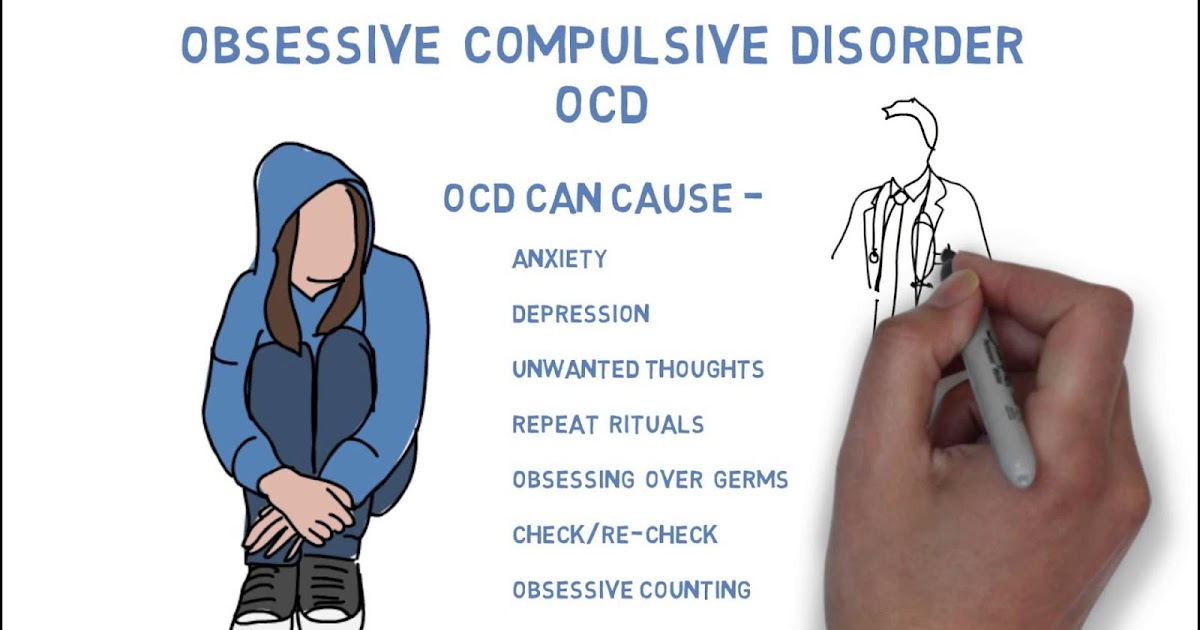

Repetition compulsion can negatively affect your life and mental well-being. It presents itself in the following ways:

- experiencing recurring dreams

- engaging in multiple abusive or toxic relationships during adulthood

- engaging in relationships with people who are emotionally distant

- having compulsions take precedence over pleasure

- repeating the same detrimental behavior without changing anything

- feeling destined to an unfavorable fate

Some older research includes information from Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis. It indicates that repetition compulsion happens when someone can’t discuss or remember the trauma. Without realizing it, these people repeat the trauma throughout their life.

It indicates that repetition compulsion happens when someone can’t discuss or remember the trauma. Without realizing it, these people repeat the trauma throughout their life.

Repetition compulsion could occur when you can’t discuss or remember past trauma or the details of the situation. When this happens, you might put yourself in an unhealthy position, although you may not realize that you’re repeating past trauma.

Repeating past trauma might occur because you subconsciously want to fix what happened. You may, without even realizing it, hope that by recreating your trauma, you can find closure and fix what happened in the past.

Some experts indicate that repetition compulsion might not have a purpose. Instead, you might repeat trauma because it’s what you know, even if it’s not a good situation. It can also be a method of linking the past to the present.

Experts indicate that other causes of repetition compulsion include:

- returning to an earlier state

- striving for understanding and seeking answers

- creating significance

- having a mental representation of past trauma

- maintaining a habitual pattern

- creating a defense mechanism

Risk factors include experiencing:

- physical or emotional abuse

- witnessing infidelity as a child

- emotionally distant caregivers or loved ones

- childhood trauma

Repetition compulsion can interfere with your well-being and emotional healing. However, you can make changes to break this pattern and develop healthier coping mechanisms.

However, you can make changes to break this pattern and develop healthier coping mechanisms.

Psychodynamic therapy

One way to overcome repetition compulsion is through psychodynamic therapy. Psychodynamic therapy involves exploring and identifying past trauma that could contribute to repetition. It helps you understand any subconscious issues you’re experiencing.

Psychodynamic therapy can help you understand your past’s effect on your life. It allows you to address and overcome traumatic experiences, leading to less intense feelings. You’ll likely have better judgment moving forward, allowing you to break the pattern of repetition compulsion.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) type of therapy involves recognizing dysfunctional automatic thoughts. CBT can help alleviate these negative thoughts, allowing you to think in realistic ways.

If you choose to try CBT, you’ll work with a therapist to change thinking patterns and behaviors. This type of therapy is more action-oriented than psychodynamic therapy, so you would spend less time discussing your past trauma and more time learning new skills.

This type of therapy is more action-oriented than psychodynamic therapy, so you would spend less time discussing your past trauma and more time learning new skills.

Group therapy

Many people who experience trauma also like to engage in group therapy. Group therapy for trauma can be a way to feel less alone with your pain and to feel a sense of solidarity with people who have related experiences.

You can either focus solely on group therapy or you can supplement it with individual therapy. Many people prefer group therapy not only because of the relationship-oriented aspect of it, but also because it tends to be more affordable.

Self-help techniques

Healing from your trauma is the first step toward breaking repetition compulsion patterns. Although working with a trauma therapist is likely best, you can simultaneously practice self-help techniques at home.

Part of coping involves reminding yourself that although can’t change the past, you can move forward and live a healthy life.

Some at-home practices you can try include:

- positive affirmations

- journaling

- deep breathing

- mindfulness meditation

- yoga

- positive visualization

Repetition compulsion can occur for various reasons regarding trauma early in life. It can involve physical, sexual, mental, or emotional abuse. This compulsion can also result from trauma developed from witnessing dysfunctional situations.

Once you identify the compulsion, you can work on overcoming it. You can turn to a mental health professional or practice self-help methods to improve your situation. There is hope, and you can make it happen.

Last medically reviewed on September 15, 2022

6 sourcescollapsed

- Blass RB. (2020). The role of repetition in narcissism and self-sacrifice: A Freudian Kleinian reflection on the person's foundational love of the other.

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00207578.2020.1809154 - Chand SP, et al.

(2022). Cognitive behavioral therapy.

(2022). Cognitive behavioral therapy.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470241/ - Freud, S. (n.d.). Compulsion to Repeat.

freudfile.org/psychoanalysis/compulsion_repeat.html - Levy MS. (1998). A helpful way to conceptualize and understand reenactments.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC3330499/ - Van de Vijver G, et al. (2017). The mark, the thing, and the object: On what commands repetition in Freud and Lacan.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5743745/ - Weiss H. (2021). Reply to the letter by Michel Sanchez-Cardenas: Does the repetition compulsion really have a purpose?

tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00207578.2021.1962114?scroll=top&needAccess=true

FEEDBACK:

Medically reviewed by Lori Lawrenz, PsyD — By Sarah Barkley — Updated on Sep 16, 2022

Read this next

The Science Behind PTSD Symptoms: How Trauma Changes the Brain

Medically reviewed by Kendra Kubala, PsyD

Trauma (PTSD) can have a deep effect on the body, rewiring the nervous system — but the brain remains flexible, and healing is possible.

READ MORE

Trauma Denial: How to Recognize It and Why It Matters

Medically reviewed by Matthew Boland, PhD

Denying or minimizing a traumatic event is a natural and useful response to pain. But in the long term, it may hurt you more. Here's why and how to…

READ MORE

4 Somatic Therapy Exercises for Healing from Trauma

Medically reviewed by N. Simay Gökbayrak, PhD

Somatic experiencing may help you treat trauma-related symptoms. Although working with a therapist is recommended, you could also practice these 4…

READ MORE

When Everyone Else Is Married with Children

If your friends are settling down, it can feel lonely. But tips, like exploring new hobbies and traditions, can help you enjoy singleness and maintain…

READ MORE

What to Do If Your Partner Doesn't Want to Attend Marriage Counseling

Marriage counselors can help you effectively communicate with your partner.

But if your spouse won't go to marriage counseling, other options are…

But if your spouse won't go to marriage counseling, other options are…READ MORE

Self Punish Often? How to Course Correct without Chastising

Medically reviewed by Jennifer Litner, LMFT, CST

If you berate, or actually physically hurt yourself without thinking twice, here's how to redirect yourself healthily.

READ MORE

What Is a Moral Compass and How to Find Yours

Your moral compass and ethics may sound like the same set of values, but your moral compass is your personal guide to what’s right and wrong.

READ MORE

Atelophobia: Overcoming this Fear of Making Mistakes

The fear of making mistakes or being imperfect is known as atelophobia. Here are treatments and self-help methods to overcome it.

READ MORE

What Is an ‘Energy Vampire’ and How to Protect Yourself

Medically reviewed by Danielle Wade, LCSW

After being with a friend, colleague, or family member, do you tend to feel emotionally exhausted? You might be dealing with an energy vampire.

READ MORE

10 Exercises to Heal Your Inner Child

Medically reviewed by Joslyn Jelinek, LCSW

Inner child exercises can help you parent and nurture your inner child, offering them the comfort they need. We look at 10 exercises you can try today.

READ MORE

Causes, theories behind it, and more

Repetition compulsion, or repetitive compulsion, is sometimes also called trauma reenactment. It involves repeating physically or emotionally painful situations that happened in the past.

The reenactment may take the form of recurring dreams and may affect relationships in various ways. Experts have several theories to explain the factors that may cause this phenomenon.

Older research from 1998 reports on some of these theories from various experts, including Sigmund Freud, who is the father of psychoanalysis. His view is that a person’s inability to discuss or remember past traumatic events might lead them to repeat these traumas compulsively.

One possible strategy for overcoming repetition compulsion is psychoanalysis, which consists of exploring and identifying early trauma that may be responsible for later reenactions.

Read on to learn more about repetition compulsion, including underlying theories about its causes, how it affects relationships, and strategies to overcome this behavior.

Repetition compulsion refers to an unconscious need to reenact early traumas. A person with this condition repeats these traumas in new situations that might symbolize the initial trauma.

Repetition compulsion can act as a barrier to therapeutic change in a person. Therapy aims to help the person remember the trauma and understand how it is influencing their current behavior.

Examples

There are different forms of reenactment, one of which is dreams. According to a 1990 case study, someone with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) might have recurring dreams of the experience or initial trauma, which might cause them to become preoccupied with it.

Research also notes that many people relive past traumas in their present lives. For example, people who experience sexual abuse during childhood are more likely to experience it as an adult.

Additionally, someone who experiences violence in their childhood may be more likely to become a perpetrator of violence in later life. The helplessness they felt as a child might motivate them to take the extreme measure of committing violence to avoid feeling it again. This behavior is a form of reenactment.

Although these examples show the negative effects of repetition compulsion, reenactment can also potentially be positive. An example of an adaptive reenactment might be when a grieving individual repeatedly tells stories about their lost loved one. This enables them to work through their loss and can reduce the pain that typically comes with grieving.

The following are some examples of repetition compulsion patterns of behavior in relationships:

- Detachment: A person who experiences violent beating as a child may use a technique called detachment as a coping mechanism.

This may lead to detachment in later relationships. Detachment refers to a person’s inability to fully engage with their feelings or the feelings of others.

This may lead to detachment in later relationships. Detachment refers to a person’s inability to fully engage with their feelings or the feelings of others. - Familiarity: People may seek the comfort of familiarity, even if it relates to something negative. For instance, an individual with a distant parent or caregiver may seek a partner who has a distant personality.

- Self-hatred: Experiencing abuse as a child may lead to feelings of self-hatred and make a person feel as though they deserve mistreatment. As an adult, this may cause them to gravitate toward others who mistreat them.

- Abandonment: After experiencing abandonment as a child, a person may demonstrate possessiveness and clinginess in relationships later on in life. These behaviors stem from the desire to avoid more abandonment.

- Triggers of past emotions: Someone whose parents or caregivers neglected them when they were a child may harbor feelings of anger about that situation.

As a result, the person may become excessively angry in later life, even in response to a minor incident. For instance, they could become angry when a friend does not return a phone call.

As a result, the person may become excessively angry in later life, even in response to a minor incident. For instance, they could become angry when a friend does not return a phone call. - Fear-motivated behavior: As an example of this, there have been links between sexual abuse in childhood and prostitution in adulthood. Research cites a specific example in which a woman explained that her involvement in prostitution was an attempt to control the opposite sex after being a victim of abuse earlier in life.

Some possible causes of repetitive compulsion behaviors include:

Rigid defenses

People may have a rigid or inflexible way of defending themselves against experiencing a repetition of their trauma, but having these mechanisms can inadvertently result in the reenactment occurring anyway.

For example, a person who experiences abandonment in their childhood may act possessively in relationships later on in life to avoid the past feelings of loneliness or neglect. However, the person may risk losing their partner if they behave in this way and may end up feeling those emotions anyway.

However, the person may risk losing their partner if they behave in this way and may end up feeling those emotions anyway.

Affective dysregulation

Affective dysregulation relates to having poorly regulated emotional reactions in response to negative stimuli. For example, people who experience frequent, harsh disapproval from a parent or caregiver may have low self-esteem. They may also be very sensitive to criticism. Consequently, in later relationships, these people may consider criticism harsh, even when it is not, and respond with hostility.

Ego deficits

Ego deficits can refer to a limitation in mental resources. This limitation might manifest as various psychosocial problems in a person.

Long-term abuse may result in psychosocial effects that can include:

- self-abusive behavior

- low self-esteem

- substance use disorders

- inability to trust

- difficult interpersonal relationships

For instance, a person with a history of growing up in an abusive environment may feel reluctant to leave an abusive partner later in life. This reluctance may stem from the inability to trust others to provide the necessary help.

This reluctance may stem from the inability to trust others to provide the necessary help.

Experts propose several theories that may explain this type of behavior. These include:

Freud theory

Some people are unable to talk about or remember a past trauma, so they express it through actions rather than words. Freud states that those who do not remember past trauma may have the drive to repeat the repressed experience in their present life.

Achieving mastery

Mastery in this context may mean that a person with traumatic past experiences is reenacting their trauma as a way to cope and heal. The problem with this theory is that reenactments rarely lead to mastery without treatment. Instead, traumatized people often lead traumatized lives.

Hyperarousal theory

An older 1989 study adds that physiological hyperarousal may play a role in repetition compulsion. This means that a person displays increased responsiveness to stimuli that remind them of the initial trauma. Hyperarousal can lead to a wide range of symptoms, including anxiety, elevation in heart rate, and stress. This type of response can hinder a person’s ability to make rational judgments.

Hyperarousal can lead to a wide range of symptoms, including anxiety, elevation in heart rate, and stress. This type of response can hinder a person’s ability to make rational judgments.

Repetitive compulsion can be very challenging to treat.

However, research from 1998 notes that psychotherapy can be effective. It involves exploring a person’s past traumatic relationships and experiences to identify how and why they are reenacting a trauma. The goal is to help a person understand the unconscious forces that drive them.

Once the individual understands the effect that the past is having on the present, they have the opportunity to integrate the traumatic experience. This may lead to less intense feelings and better judgment. The aim of treatment is to break the pattern of repetition.

Some people may not wish to undergo in-depth psychoanalysis or psychodynamic therapy. For these individuals, other types of talk therapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), may be a more suitable approach.

Learn more about psychodynamic therapy.

Repetition compulsion, or trauma reenactment, may occur due to various painful experiences early in life, such as physical, sexual, or emotional abuse. An inability to resolve or integrate the past trauma can result in the person reliving the circumstances.

Psychoanalysis and psychotherapy can enable someone to work through the trauma, which can help stop the reenactments.

V.S. EgorovPhD in Law, Head of the Department of Criminal, Penal Law and Criminology

Perm branch of the Nizhny Novgorod Academy of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia. 614038, Perm, st. Acad. Vedeneeva, 100

E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You must have JavaScript enabled to view.

The article is devoted to the theoretical and legal analysis of preventive and resocializing measures of state coercion in criminal law. The essence of this criminal law institution, the procedure for its implementation, individual measures of preventive and resocializing influence in relation to persons who have committed a socially dangerous act prohibited by criminal law are considered.

Key words: criminal enforcement; preventive and resocializing impact

One of the main priorities of criminal policy in modern conditions is the economy of criminal repression, which involves the provision of assistance in the socialization of unstable citizens, the priority of preventive measures over the application of criminal punishment for an already committed crime. The timely implementation of preventive and resocializing measures against a person prone to antisocial forms of behavior is, as a rule, more appropriate and effective than strict coercion of the perpetrator within the framework of criminal liability.

Therefore, a preventive re-socializing effect has become an independent type of state coercion in criminal law, which is devoid of the element of punishment, but allows it to have an effective impact on its addressee. I.A. Burlakova focuses in this regard on the fact that the fulfillment by a person of the requirements and restrictions imposed during probation (which are one of the manifestations of preventive-resocializing measures of influence) largely disciplines the convict and allows you to check the degree of his correction [1, p. 107].

107].

Measures of preventive and resocializing influence are coercive and are directly related to the restriction or deprivation of the rights and freedoms of the person to whom they are applied. However, they do not relate to criminal liability, do not contain punishment and do not imply any suffering of the person to whom they are applied. N. Yu. Skripchenko [12, p. 18]. Such an approach cannot be recognized as correct, because the indicated criminal law institution is not aimed at causing negative consequences to an individual (which characterize the essence of punishment), but is called upon to exert a corrective effect on a teenager in a specific way, which, although associated with restrictions, is not inherently punishment.

The compulsory nature of preventive and resocializing measures is determined by the mandatory procedure for application. This provision means that the presence or absence of the desire of a person in respect of whom measures of a preventive and resocializing nature are prescribed is of no fundamental importance, since a citizen is obliged to undergo them in full. In the absence of his consent, these measures of state coercion are performed involuntarily and are provided, in accordance with Part 4 of Art. 90 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, the possibility of applying measures of criminal liability.

In the absence of his consent, these measures of state coercion are performed involuntarily and are provided, in accordance with Part 4 of Art. 90 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, the possibility of applying measures of criminal liability.

The compulsory procedure for the application of measures of a preventive and resocializing nature is explained by the need to exert an effective influence on a person, when there is no reason to punish him (when an assault is committed in a state of insanity) or it is inappropriate (for example, when a minor commits a crime of minor gravity for the first time), but leave the deed without consequences it is forbidden. The fact of committing a socially dangerous act clearly confirms the fact that a person poses a serious threat both to himself and to others. Therefore, in such cases, measures of state coercion of a preventive and resocializing nature are a special way of responding to the clearly asocial behavior of an individual, when the achievement of the desired result is ensured by influencing significant interests, and otherwise it is not possible to influence him. The primary task of applying measures of a preventive and resocializing nature is to create the prerequisites under which the likelihood of a repetition of the delict is excluded or significantly reduced by eliminating the conditions that contribute to the asocial orientation of the subject's act, as well as the implementation of the educational process. In such cases, the individual, without being liable, is forcibly limited in his behavior, is obliged to carry out socially useful activities.

The primary task of applying measures of a preventive and resocializing nature is to create the prerequisites under which the likelihood of a repetition of the delict is excluded or significantly reduced by eliminating the conditions that contribute to the asocial orientation of the subject's act, as well as the implementation of the educational process. In such cases, the individual, without being liable, is forcibly limited in his behavior, is obliged to carry out socially useful activities.

Measures of state coercion of a preventive and resocializing nature are applied in cases of release from liability or punishment, or in the absence of grounds for criminal liability. At the same time, in some cases, the implementation of measures of state coercion of a preventive and resocializing nature can occur along with the implementation of criminal liability. This applies to coercive measures of a medical nature in relation to persons recognized as partially sane. They are subject to criminal liability, but the disease requires appropriate medical supervision. On this basis, these persons undergo criminal liability measures, in parallel with which compulsory medical measures are applied.

On this basis, these persons undergo criminal liability measures, in parallel with which compulsory medical measures are applied.

The foregoing allows us to conclude that preventive and resocializing measures of state coercion have common content, goals and orientation. Measures of state coercion of a preventive and resocializing nature should be understood as obligations and prohibitions provided for by criminal law, applied by a court decision without fail to a person who has committed a socially dangerous act prohibited by criminal law, in order to ensure positive changes in the state of his health and personality, as well as to prevention of re-offending.

Measures of preventive and resocializing state coercion include: restrictions and obligations imposed in the case of probation and parole, compulsory educational measures for minors, as well as compulsory medical measures.

Restrictions and obligations imposed upon probation and parole from serving a sentence . Regarding the legal nature of probation, several different points of view have developed in the literature. According to M.D. Shargorodsky, it is a special procedure for serving a sentence [17, p. 156–157]. N.G. considers a conditional sentence to be a special case of sentencing. Kadnikov [4, p. 131]. In turn, D.A. Shestakov believes that a suspended sentence is the non-application to the person who committed the crime of the punishment imposed by the court [16, p. 552]. Yu.M. Tkachevsky proposes to consider this institution as a conditional release of the perpetrator from the real suffering of the appointed punishment [15, p. 20]. In our opinion, the last of the presented positions is more correct, since the application of a suspended sentence means the release of the guilty person from the actual serving of the sentence imposed by the court, which is not actually applied.

Regarding the legal nature of probation, several different points of view have developed in the literature. According to M.D. Shargorodsky, it is a special procedure for serving a sentence [17, p. 156–157]. N.G. considers a conditional sentence to be a special case of sentencing. Kadnikov [4, p. 131]. In turn, D.A. Shestakov believes that a suspended sentence is the non-application to the person who committed the crime of the punishment imposed by the court [16, p. 552]. Yu.M. Tkachevsky proposes to consider this institution as a conditional release of the perpetrator from the real suffering of the appointed punishment [15, p. 20]. In our opinion, the last of the presented positions is more correct, since the application of a suspended sentence means the release of the guilty person from the actual serving of the sentence imposed by the court, which is not actually applied.

In most cases, probation is used for crimes that do not pose an increased public danger, if the correction of the perpetrator can be achieved without the actual application of criminal punishment. At the same time, the court takes into account the nature and degree of public danger of the crime committed, the identity of the perpetrator, including mitigating and aggravating circumstances. A necessary prerequisite for the application of probation is the requirement not to commit new offenses, as well as the possibility of correcting a person without serving a sentence.

At the same time, the court takes into account the nature and degree of public danger of the crime committed, the identity of the perpetrator, including mitigating and aggravating circumstances. A necessary prerequisite for the application of probation is the requirement not to commit new offenses, as well as the possibility of correcting a person without serving a sentence.

Parole from serving a sentence, in accordance with Art. 79 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, is applied to persons sentenced to detention in a disciplinary military unit or deprivation of liberty, if it is recognized by the court that for their correction they do not need to fully serve the sentence imposed by the court. The grounds for the application of conditional early release from punishment are the loss by the convict of public danger and his correction.

In connection with the above, we can conclude that conditional conviction and parole are designed to save criminal repression. At the same time, the state provides the convict with a chance to improve without the application or full serving of a criminal sentence. However, this does not mean the termination of the implementation of coercive measures in relation to him. It's just that in this case it moves from a punitive-correctional plane to another - a preventive-resocializing plane. Therefore, in case of conditional condemnation, the court establishes a probationary period during which the convicted person must prove his correction by his behavior. In case of conditional early release, the entire remaining unserved part of the term, the convict is considered to be conditionally released. V.V. Pronnikov and A.A. Nechepurenko note that non-punitive legal restrictions on probation on the content side are requirements addressed to the subject not to perform certain actions (prohibitions) and requirements to act in this way (prescriptions) [8, p. 37].

At the same time, the state provides the convict with a chance to improve without the application or full serving of a criminal sentence. However, this does not mean the termination of the implementation of coercive measures in relation to him. It's just that in this case it moves from a punitive-correctional plane to another - a preventive-resocializing plane. Therefore, in case of conditional condemnation, the court establishes a probationary period during which the convicted person must prove his correction by his behavior. In case of conditional early release, the entire remaining unserved part of the term, the convict is considered to be conditionally released. V.V. Pronnikov and A.A. Nechepurenko note that non-punitive legal restrictions on probation on the content side are requirements addressed to the subject not to perform certain actions (prohibitions) and requirements to act in this way (prescriptions) [8, p. 37].

Measures of state coercion of a preventive and resocializing nature, applied in case of conditional conviction or parole, are expressed in a number of obligations and restrictions provided for by the criminal law: do not change the permanent place of residence, place of work and study without notifying the penitentiary inspectorate, do not visit certain place, undergo treatment for alcoholism, drug addiction and substance abuse or a sexually transmitted disease, provide financial support to the family. The court also has the right to impose other restrictions and prohibitions on the convict, the implementation of which may contribute to his correction. These include, for example, imposing the obligation to get a job or return to an educational institution, to appear for registration at the penitentiary inspection, to compensate for the damage caused by the crime, etc.

The court also has the right to impose other restrictions and prohibitions on the convict, the implementation of which may contribute to his correction. These include, for example, imposing the obligation to get a job or return to an educational institution, to appear for registration at the penitentiary inspection, to compensate for the damage caused by the crime, etc.

The application of the above obligations and restrictions (with the exception of the obligation to provide material support to the family, which is one of the security measures) makes it possible to have a positive impact on the convict, forcing him to a socially useful lifestyle and creating conditions for his correction. Therefore, A.S. Mikhlin emphasizes that the restrictions imposed in cases of applying the considered types of exemption from punishment contribute to the correction of convicts, the process of their resocialization [6, p. 84–86]. The fulfillment of these duties and restrictions is mandatory and is ensured by the possibility of the actual application of the punishment imposed upon probation, and in the case of parole, the unserved part of the punishment. The second way to ensure the fulfillment of the assigned obligations is the possibility for the court to supplement the list of restrictions in case the person evades their implementation. During the probationary period and the unserved part of the punishment, the behavior of the person is constantly monitored by the penitentiary inspection at the place of residence of the convict, and in relation to conditionally convicted servicemen - by the command of their military units.

The second way to ensure the fulfillment of the assigned obligations is the possibility for the court to supplement the list of restrictions in case the person evades their implementation. During the probationary period and the unserved part of the punishment, the behavior of the person is constantly monitored by the penitentiary inspection at the place of residence of the convict, and in relation to conditionally convicted servicemen - by the command of their military units.

Along with the noted prohibitions and restrictions, conditional conviction and parole must be associated with imposing on the convict the obligation to refrain from committing repeated crimes and violations of public order. The fulfillment of this duty is reinforced by the threat of the actual application of the imposed or unserved punishment, which, as L.E. Eagle, has an additional impact on the convict [7, p. 6].

Compulsory educational measures applied to minors . The level of development of the psyche of minors in a fairly complete way allows them to realize the social danger and the actual nature of unlawful behavior. Despite this, adolescence remains characterized by a significant gap between the degree of intellectual development, social maturity and the level of demands placed on young people by society. The lack of extensive life experience, coupled with individual psychological characteristics, can lead to the formation in individual adolescents of a superficial idea of moral categories and concepts. The personality of minors is highly dependent on the environment, economic condition and moral climate in the family. In addition, the desire for self-assertion, characteristic of the younger generation, can take spontaneous forms in such persons, which often leads to the commission of situational crimes.

Despite this, adolescence remains characterized by a significant gap between the degree of intellectual development, social maturity and the level of demands placed on young people by society. The lack of extensive life experience, coupled with individual psychological characteristics, can lead to the formation in individual adolescents of a superficial idea of moral categories and concepts. The personality of minors is highly dependent on the environment, economic condition and moral climate in the family. In addition, the desire for self-assertion, characteristic of the younger generation, can take spontaneous forms in such persons, which often leads to the commission of situational crimes.

These circumstances leave a significant imprint on the behavior of minors, who are more susceptible to influence from other persons, especially adults. All this causes a lower degree of social danger for teenagers. It should also be taken into account that minors are much more susceptible to correction compared to adults, they more easily perceive the educational impact inherent in the content of criminal law coercion measures. This is explained by the fact that, as a rule, they do not have time to develop a stable asocial orientation, as well as the skills of criminal activity.

This is explained by the fact that, as a rule, they do not have time to develop a stable asocial orientation, as well as the skills of criminal activity.

The indicated points demonstrate the need for a special approach to the issues of criminal coercion of minors, one of the manifestations of which is the possibility of applying measures of educational influence provided for by law. This makes it possible to fully take into account the specifics of the consciousness and behavior of minors, and also makes it possible to achieve the goal of punishment without its application. Compulsory measures of educational influence are not a way to implement criminal liability and have significant differences from punishment. Their content includes such methods of influence that allow a sufficient influence on a minor without the use of strict methods of coercion that can negatively affect his moral and physical development. These measures are educational. However, they have their own characteristics: the usual measures of education applied to a minor by parents or persons replacing them turned out to be ineffective, which is confirmed by the fact that he committed a crime. Therefore, the state takes this process under its control, starting to educate a teenager with specific methods of influence that are coercive.

Therefore, the state takes this process under its control, starting to educate a teenager with specific methods of influence that are coercive.

Compulsory measures of educational influence are aimed at preventing new crimes by minors, their education and correction through influence not related to punishment. “... With regard to adolescents who have committed unlawful acts, education can simultaneously be both a goal and one of the ways to achieve the goals of criminal law. In the latter case, educational influence turns into a measure that replaces criminal liability (punishment), into compulsory measures of educational influence" [10, p. 34]. Yu.E. Pudovochkin, who considers measures of educational influence as a form of implementation of criminal liability, as well as a special type of liability - juvenile. At the same time, he admits the presence of an element of punishment in them [9, With. 198–210]. This approach seems to be completely untenable. Compulsory measures of educational influence are used as an alternative to criminal liability, upon release from it. Their very name directly indicates that, despite their coercive nature, they are not aimed at causing suffering to a teenager, but at educating him and instilling socially useful skills. In the process of implementing coercive measures of educational influence, certain rights and freedoms of a minor may be limited, but there is no reason to call this responsibility and ways of expressing punitive influence. Therefore, the assertion that measures of educational influence, such as warning, transfer under supervision, are specifically aimed at causing any negative consequences to a teenager and are a measure of criminal liability, seems unreasonable.

Their very name directly indicates that, despite their coercive nature, they are not aimed at causing suffering to a teenager, but at educating him and instilling socially useful skills. In the process of implementing coercive measures of educational influence, certain rights and freedoms of a minor may be limited, but there is no reason to call this responsibility and ways of expressing punitive influence. Therefore, the assertion that measures of educational influence, such as warning, transfer under supervision, are specifically aimed at causing any negative consequences to a teenager and are a measure of criminal liability, seems unreasonable.

The foregoing allows us to derive the following definition of compulsory measures of educational influence in relation to minors: these are special methods of education provided for by criminal law, applied involuntarily to a minor who has committed a crime, when exempted from criminal liability and punishment in order to correct him and prevent the commission of crimes by imposing official duties and restrictions.

Compulsory measures of educational influence are used when a minor is released from criminal liability or criminal punishment. According to Art. 90 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, measures of coercive influence in relation to minors are: warning, transfer under the supervision of parents or persons replacing them, or a specialized state body, imposing the obligation to make amends for the harm caused, limiting leisure and establishing special requirements for the behavior of a minor. In addition, on the basis of Art. 92 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, upon release from punishment, such a measure of coercion as placement in a special educational and educational institution of a closed type of an education management body can be applied to a teenager.

The mentioned measures of coercion (except for the imposition of the obligation to make amends for the damage caused, which refers to the measures of provision) make it possible to exert a preventive and corrective effect on the adolescent in the least painful way, taking into account his psychophysiological and social characteristics. “Regarding the measures of state coercion, these measures are implemented in a milder form and in most cases preserve the usual educational environment for a minor, focus on achieving the goals set by the criminal law by ordinary educational means, only reinforced by the threat of state coercion. In addition, they do not entail the social and legal consequences that punishment entails.” The implementation of compulsory educational measures allows, outside the framework of criminal responsibility, to effectively influence the minor, explaining to him the danger of the deed and the possible consequences of re-committing crimes, eliminating the impact of external negative factors on him, and creating obstacles to communication with persons that negatively affect the teenager.

“Regarding the measures of state coercion, these measures are implemented in a milder form and in most cases preserve the usual educational environment for a minor, focus on achieving the goals set by the criminal law by ordinary educational means, only reinforced by the threat of state coercion. In addition, they do not entail the social and legal consequences that punishment entails.” The implementation of compulsory educational measures allows, outside the framework of criminal responsibility, to effectively influence the minor, explaining to him the danger of the deed and the possible consequences of re-committing crimes, eliminating the impact of external negative factors on him, and creating obstacles to communication with persons that negatively affect the teenager.

Measures of educational influence can be associated with different ways of coercion. The warning includes the censure of a teenager on behalf of the state, which prompts him to think about his behavior and reconsider his attitude to social interests [5, p. 127]. When transferring the behavior of a minor to supervision, strict control is exercised, which makes it possible to check how the assigned duties are performed, and ultimately helps to eliminate antisocial ties. The restriction of leisure is associated with a ban on the implementation of asocial forms of behavior by a teenager or the imposition of an obligation to take measures for socialization by returning to an educational institution or employment. Placement in a special educational institution of a closed type of the educational authority is used when a minor needs special conditions for education, training and requires a special pedagogical approach. The application of this measure is related to ensuring the personal safety of minors, their maximum protection from negative influences, isolation of minors, round-the-clock monitoring and control of minors, personal examination of minors, inspection of their belongings.

Compulsory medical measures. Only a mentally healthy person who is aware of the actual nature of what is happening and is able to control his behavior is subject to criminal liability and punishment. Therefore, if a socially dangerous act is carried out in a state of insanity, the individual is not the subject of a crime and cannot bear criminal responsibility. Situations are possible when a criminal act is committed by a sane citizen, who, after its completion, begins to suffer from a mental disorder that caused the onset of insanity. In such cases, a person is recognized as the subject of a crime, but is not subject to criminal punishment due to the inability to perceive punitive and educational influence.

Therefore, persons suffering from mental disorders that exclude sanity are not subject to the application of punishment and other measures of criminal liability: such an individual does not perceive the educational impact, and his health may worsen. At the same time, the presence of a mental illness in a person requires the application of treatment measures aimed at his recovery and the prevention of new socially dangerous acts. This is due to the fact that the patient poses a real threat to society, which is confirmed by the fact that he committed an attack. In addition, a mental disorder is a powerful desocializing factor that prevents a normal life and contributes to the loss of social ties, professional skills, and the deterioration of his mental and physical health.

It is also not uncommon for a person who has committed a crime to suffer from a mental disorder that does not exclude sanity. Such a person is recognized as the subject of a crime and is subject to criminal liability and punishment. At the same time, the presence of a mental illness in him requires the application of not only measures of responsibility to him, but also treatment aimed at improving his condition. Leaving him without medical attention, moreover, in the stressful conditions that take place in the execution of a criminal sentence, would almost certainly mean serious harm to the patient's health and further progression of mental illness.

Therefore, the criminal law provides for the possibility of imposing compulsory measures of a medical nature. They form an independent type of state-legal coercion in criminal law and consist in involuntary psychiatric treatment, implemented in relation to persons suffering from mental disorders and in a state of danger to themselves and others.

The foregoing allows us to derive a definition of compulsory medical measures: these are methods of treatment provided for by criminal law, applied involuntarily to persons who have committed a socially dangerous act and suffering from a mental disorder, in order to improve their condition or cure and prevent new attacks.

Compulsory measures of a medical nature do not express a negative assessment of the deed by the state and do not entail a criminal record. In the process of their implementation, the person is exposed not to punitive, but to therapeutic effects. Despite the compulsory order of application, medical measures are methods of treatment, not punishment, and consist in providing medical assistance to a person who has committed a socially dangerous act. Their implementation, according to the fair remark of T.N. Zhuravleva, due to the need to cure a mental disorder and eliminate the danger to society [3, p. 14]. The concepts of "punishment" and "coercion" are close, but not at all identical in their content. Punitive action involves not only limiting the interests of a person, but also entails suffering in response to his unlawful behavior. Kara, as noted by V.G. Smirnov, is mainly characterized by the infliction of hardships prescribed by law, adverse effects on the guilty person [13, p. 181]. In turn, coercive influence can be expressed not only in the form of punishment, but also in other forms (measures of restraint, enforcement of duties, preventive measures, etc.). Consequently, coercion by no means always marks a punishment, which equally applies to medical measures that are aimed, though not at voluntary, but precisely at treatment and are not associated with causing suffering. When conducting compulsory treatment, only officially approved methods of diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation are used.

The choice of methods of treatment may be determined solely by clinical indicators. Therefore, in the scientific literature there is an opinion that the studied form of criminal coercion is more a medical category than a legal one [11, p. 126–127]. In turn, B.A. Spasennikov, on the contrary, points out on this issue: coercive measures have a pronounced criminal-legal character, which is determined both by the basis and by the legislative procedure for their regulation [14, p. 42–47].

In our opinion, compulsory medical measures should be considered as a complex category in which legal and medical aspects coexist equally, forming a single phenomenon. On the one hand, they are provided for by the criminal law, which determines the grounds, goals and procedure for their application, as well as changes and termination. On the other hand, the direct process and methods of implementing compulsory treatment measures are determined purely from the standpoint of medicine. Therefore, to put this or that aspect in the first place would not only be methodologically incorrect, but would also mean opposing one to the other.

The correctness of this argument is confirmed by the grounds for the application of compulsory medical measures: legal and medical. The legal basis is the commission of an act prohibited by criminal law and the danger of a person to himself or others. The medical basis is the presence of a mental disorder in a person. Separately from each other, these grounds cannot determine the possibility of applying coercive measures of a medical nature. For this reason, the European Court of Human Rights found Naumenko's complaint justified regarding the unjustified use of psychotropic drugs due to his tendency to commit suicide, since this citizen did not suffer from a mental disorder [2, p. 12].

Summing up the consideration of measures of preventive-resocializing impact, it should be noted that, despite the independent nature of the criminal law institution under consideration, it has not found its way into the criminal law. On this basis, we propose to supplement the Criminal Code with Art. 42 5 “Measures of a preventive and resocializing nature” in two parts as follows: part 1 – “Measures of a preventive and resocializing nature are obligations and prohibitions provided for by criminal law, applied by a court decision without fail to a person who has committed a public offense prohibited by criminal law a dangerous act in order to ensure positive changes in the state of his health and personality, as well as to prevent the commission of repeated attacks”; Part 2 - “Measures of a preventive and resocializing nature are: restrictions and obligations imposed in the event of the application of conditional conviction and parole, compulsory measures of educational influence in relation to minors, as well as compulsory measures of a medical nature.”

Bibliographic list

- Burlakova I.A. Probation: theoretical, legal and practical problems: thesis ... cand. legal Sciences. M., 2003. 153 p.

- Bulletin of the European Court of Human Rights.

2002. No. 5. (Russian ed.).

- Zhuravleva T.N. Institute of compulsory medical measures in the legislation of the Russian Federation: author. dis…. cand. legal Sciences. Rostov n / D., 2000. 27 p.

- Kadnikov N.G. Classification of crimes under the criminal law of Russia / Law Institute of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation. M., 2000. 187 p.

- Karelin D.V. Compulsory measures of educational influence as an alternative to criminal liability: thesis .... cand. legal Sciences. Tomsk, 2001. 258 p.

- Mikhlin A.S. Problems of early release from serving a sentence. M.: Delo, 2000. 176 p.

- Orel L.E. Parole from deprivation of liberty under Soviet criminal law. Kharkiv, 1966. 44 p.

- Pronnikov V.V., Nechepurenko A.A. The content of probation and ways to optimize its appointment // Ros. justice. 2007. No. 7. pp. 37–39.

- Pudovochkin Yu.

E. Responsibility of minors in criminal law: history and modernity. Stavropol, 2002. 256 p.

- Sverchkov V. On the possibility and effectiveness of exemption from criminal liability (punishment) in connection with the use of coercive measures of educational influence // Professional. 2000. No. 5(37). pp. 34–37.

- Sementsova I.A. Criminal liability of persons with mental disorders that do not exclude sanity: thesis .... cand. legal Sciences. M., 1999. 175 p.

- Skripchenko N.Yu. The use of coercive measures of educational influence in relation to minors (based on the materials of the Arkhangelsk region): author. dis…. cand. legal Sciences. M., 2002. 26 p.

- Smirnov V.G. Functions of Soviet criminal law (subject, tasks, methods of criminal law regulation). L .: Publishing house Leningrad. university, 1965. 186 p.

- Spasennikov B.A. Compulsory medical measures: history, theory, practice.

SPb.: Jurid. Center Press, 2003. 412 p.

- Tkachevsky Yu.M. Release from serving a sentence. M.: Yurid. lit., 1970. 240 p.

- Criminal law at the present stage: Problems of crime and punishment / ed. ON THE. Belyaeva, V.K. Glistina, V.V. Orekhov. St. Petersburg: Publishing House of St. Petersburg. un-ta, 1992. 608 p.

- Shargorodskiy M.D. Punishment under Soviet criminal law. M.: Publishing House of Moscow State University, 1973. Part 2. 160 p.

It is difficult to look for a black cat in a dark room, especially if it is not there. RAND Seeking Cyber Coercion

What is cyber enforcement, and how do states conduct cyber operations to coerce others? These questions are at the heart of the RAND Research Institute's recently published report Fighting Shadows in the Dark. Fighting Shadows in the Dark. Understanding and Countering Coercion in Cyberspace. The authors of this paper look at how four states — Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea — conducted cyber operations and try to figure out whether this was cyber coercion.

Peace through force does not imply the development of any generally acceptable mechanism for reducing tension in the ICT environment. And while, as the authors themselves point out, not all of the cases reviewed in the report are clear acts of cybercoercion, there is a need to develop means to detect early signs of cybercoercion and develop containment and resilience strategies. This is expected to be sufficient to successfully respond to cyber-coercion. The authors see no other way to solve the problem, except for the development of counteraction strategies (it can be assumed that using all available means, including through "public attribution").

In conclusion, the authors reiterate the thesis that in the case of cyber operations, there are no clear signals from states of either threats or expected behavior, let alone the means they can use for coercion. It is also argued that it is rather difficult to determine whether cyber operations directed against another country are intended to be coercive or otherwise. Perhaps here it makes sense to use Occam's methodological principle - "one should not multiply things unnecessarily." Indeed, as the authors postulate, ICT tools are actively used by many states to implement military-political tasks. However, if the purpose of a certain action is not to change the political behavior of another country, and there is no direct threat or use of force (which, by the way, violates the UN Charter), is there so-called coercion, or are we dealing with cyber activity that has become completely ordinary? A striking example of the policy of coercion, which the authors mention but do not consider, is related to the cyber attack on the facilities of Iran's nuclear program in 2010. First, there were demands from specific countries that Iran stop its nuclear program. Secondly, it was also about a possible strike if the requirements were not met. As you know, Iran did not change its policy, and the ensuing cyber attack was not an act of coercion or a limited show of force, but solved very specific tasks - Iran's nuclear program significantly slowed down development.

What is needed is not strategies to counter cyber coercion, of which there are practically no examples so far, but the development of mechanisms at the international level to prevent conflicts in cyberspace. One of such mechanisms can be the norms, rules and principles of responsible behavior of states in the ICT environment, formulated by the international community during the work of the UN Group of Governmental Experts.

What is cyber enforcement, and how do states conduct cyber operations to coerce others? These questions are at the heart of the RAND Research Center's recently published report Fighting Shadows in the Dark. Fighting Shadows in the Dark. Understanding and Countering Coercion in Cyberspace. The authors of this paper look at how four states — Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea — conducted cyber operations and try to figure out whether this was cyber coercion.

Turning directly to the conclusions of the study, we note the following theses. Cyber operations that can be classified as coercive constitute only a small fraction of the total number of cyber operations in the world. The main goal of cyber operations carried out by states remains espionage. Despite this, the authors believe that states such as Russia and North Korea use cyber operations as a tool of coercion more often than China and Iran. Also, contrary to what the theory of coercion postulates, in the cases under consideration, states often do not express a clear threat and do not make clear demands for policy change. On the contrary, states do not take responsibility by acting through proxy actors. The authors suggest that despite the low probability of success, states will continue to use cyber operations for coercion, and this practice may become more frequent in the future. To prepare for this scenario, the United States and its allies need to understand how cyber-coercion can emerge, create systems to warn of upcoming operations, and develop strategies to deter and respond to cyber-coercion.

Anastasia Tolstukhina:

Is the US launching cyber attacks on Russia's critical infrastructure?

Despite some scientific value of this report, the authors left a fairly large margin for criticism. First, it is necessary to dwell in more detail on a number of significant methodological problems. Secondly, leaving aside the fact that the study itself was commissioned by the US Department of Defense and affiliated structures, it is emphasized that the study relies only on open sources - indeed, the evidence base is mainly represented by reports from companies such as Mandiant and who bought it subsequently FireEye, whose leadership has some ties to both the Department of Defense and the US intelligence community. Thus, the evidence used by the authors in the course of the study of the involvement of a particular country in conducting cyber operations cannot be characterized as objective. Finally, it is regrettable that the solutions proposed by the authors are surprisingly one-sided, without any hint of the possibility of positive action.

Coercion

The methodology of the authors of the work in that part of it, which concerns the development of a definition of what constitutes coercion in cyberspace, is trying to rely, among other things, on the fundamental work of the American economist Thomas Schelling “Arms and Coercion”. It is argued that Schelling distinguishes two types of coercion - active (compulsion - compellence ) and passive (in the form of restraint - deterrence). At the same time, according to the authors, one involves the active use of force in one form or another to coerce actions, while the second involves the use of the threat of the use of force either to motivate action or to refrain from a specific action. Schelling's work itself says the following:

“...in part, deterrence [ deterrence ] has become a euphemism for the broader concept of coercion, as “defense” has replaced words like “war” and “military” in our official terminology. This euphemism is restrictive if it prevents us from realizing that there is a real difference between deterrence and what I should have called "coercion" in chapter 2, that is, a real difference between inducing inaction and inducing someone to take action. 1].

“...brute force succeeds when it is used, while the ability to inflict pain is most successful when it is in reserve. It is the threat of causing harm or receiving more harm that can force someone to yield or submit. It is implicit violence that can influence someone's choice - violence that can still be either restrained or used ... The threat of pain is trying to change someone's motives, and brute force is trying to overcome his strength. Unfortunately, the ability to inflict pain is often expressed through some kind of demonstration. Whether it's terror designed to elicit an irrational response, or calculated, deliberate violence designed to demonstrate one's determination to someone and indicate the possibility of it happening again, it's not the pain and damage itself that matters, but their effect on one's behavior. The required behavior (if it can be obtained at all through the threat of force) is the result of expectation greater violence"[2].

It is clear that Schelling draws a clear line between deterrence and coercion, and, more importantly, points out the limitations of the use of force in the implementation of coercion - force, as such, plays a secondary role, and in the first place is the expression of the threat of harm.

Pavel Karasev:

Cyberboys without rules

Further, when describing the logic of coercion, the authors cite several research papers that also repeat Schelling's theses. In one of them, the essence of coercion is described by the phrase: “if you do not do X, I will do Y”[3]. Another paper states that an act of coercion or a threat "requires clarity about the expected result ... [and must] be accompanied by some kind of insistent signal"[4]. It seems that these theses are correct and should be taken as a basis. The authors of the report go the other way - they claim that the practice of cyber coercion does not correspond to theoretical calculations (which, it should be noted, were derived from practice), and argue that the demands and threats put forward in the course of such coercion are not always unambiguous, just as they may not be unambiguous identification of the threatening party. However, if the characteristics that define it are removed from coercion, will it not cease to exist? The implementation of large-scale cyber attacks is no longer just a show of force, but the solution of specific problems, and thus they are not related to coercion.

The foregoing makes us think about the correctness of the question asked by the authors at the beginning of the report: "What is cyber coercion?". Consider what constitutes coercion in essence. It seems that this is, first of all, a form of policy aimed at maintaining or changing the existing order of distribution of power and property in the world community[5]. From this point of view, the essence of coercion is to change the political behavior of other actors in world politics with a possible limited show of force that does not escalate into full-scale hostilities. To some extent, the essence of the policy of coercion is described in the treatise of the ancient Chinese commander Sun Tzu “The Art of War”: “Who knows how to wage war, conquers a foreign army without fighting; takes other people's fortresses without besieging; crushes a foreign state, not holding his army for a long time. Still force coercion is also possible - Schelling, arguing about this, gives an example from the history of the conquest of the Wild West - the raids that were arranged on some Indian settlements were designed to break the resistance of all tribes, and subjugate them to their will. However, in this case, the Indians were quite clear about both the source of the threat, the possible consequences of resistance, and the demands placed on them, and the way of salvation - to submit or flee.

Taking the above thesis about coercion as a form of policy as a basis, it seems that a more correct question to ask is the following - can cyber tools be used to implement coercive politics, and if so, how effectively? Based on the definition of coercion, its implementation in general requires the requirement of party A to party B regarding the change in the latter's policy in a specific way - in the demonstration of force that can be used in full in case of non-compliance with the requirements. In some cases, demands, threats, or a show of force may be implicit, but it is obvious that they should be are understood by by the victim party and, moreover, are correctly understood by . This imposes certain conditions on the means used in the implementation of the policy of coercion.

The ICT environment has a number of properties that make exposure through it attractive. First of all, we are talking about anonymity and cross-border, which complicate the process of attribution, that is, determining the source of impact. The possibility of "plausible deniability" of cyberattacks is one of the most important advantages of their military-political use. As practice shows, cyberattacks can be used to project and demonstrate power, but the party using them to implement coercion will have to take responsibility, or otherwise show their involvement. According to some reports, a lot of cyber attacks are made on the state information infrastructure of Russia every day (2. 4 billion impacts were recorded in 2017, and more than 4 billion in 2018). It is impossible to recognize in this stream a show of force or a demand for a change in policy. Using the possibility of a cyber attack as a threat also seems to be ineffective, because a potential adversary gets the opportunity to prepare for an attack and successfully resist it.

Public policy

The authors of the report argue that, as more interconnected and interdependent information systems and networks develop, the ability to use cyber operations to influence and influence the economic, political and social well-being of other states increases. At the same time, the study of possible episodes of cybercoercion is limited to only four subjects of world politics that have been identified by the US government as causing the greatest concern - Russia, China, Iran and North Korea. For each country, an open source study was conducted that looked at existing cyber capabilities, published cyber operations doctrines, and available data on cyber groups associated with governments.

Artur Khetagurov:

Iranian Cyber Power

The study of doctrines and documents that reveal the positions of states on operations in cyberspace is incomplete, contradictory, and in some places downright erroneous. For example, while quoting from strategic planning documents of the Russian Federation, the authors simultaneously argue that “although Russia believes that its adversaries conduct such [information] operations against it, the documents demonstrate how Russia sees the potential role of cyber operations in its activities.” Here it is enough to pay attention to the Conceptual Views on the Activities of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation in the Information Space, which says: “The resolution of conflicts in the information space should be carried out, first of all, through negotiations, reconciliation, appeal to the UN Security Council or regional bodies, or agreements, or by other peaceful means." The authors also cite Chinese experts who highlight a number of shortcomings of network deterrence and coercion - first of all, the effectiveness of cyber operations can be reduced due to ambiguity[6]. The success of deterrence and enforcement depends on effective signaling. In order for the enemy to take the expected actions, he, first of all, must know the source and motivation of the impact exerted on him. The authors conclude that China “is taking a more prudent approach to using cyber operations for coercion, focusing on data theft or suppression of regime critics. However, China may try to expand the use of cyber operations for enforcement in the future.” This conclusion is not based on anything, especially if we take into account all the shortcomings that Chinese experts point out.

As far as considering the specific cyber capabilities of each state, it is very unfortunate that the work done by the RAND research group is not based on hard facts. For example, as evidence of Russian involvement in the 2018 cyberattacks on Montenegro, an article is cited stating: “According to three international information security companies, emails [with malware] came from APT28, also known as Fancy Bear, which, according to US intelligence agencies, is associated with the Russian military intelligence GRU. In a similar way, China's involvement in cyber attacks on South Korean networks and systems, and other episodes of cyber attacks under consideration are also "proven". Mention is made of a 2017 case in which the US Department of Justice filed charges of cyber espionage against three employees of the Chinese company Boyusec. Although federal prosecutors deliberately did not raise the issue of Boyusec's affiliation or ties to the Chinese government, private sector officials indicated that they believed Boyusec was working for the Chinese Ministry of State Security. The creation of myths is facilitated by repeated repetition and emphasis even on those facts that were subsequently refuted. Thus, among other things, it is claimed that in 2008 Russia carried out cyber attacks on Estonian government institutions, although this claim has long been refuted - an independent study confirmed that these were the actions of individual activists, not the government.

The RAND report relies on biased evidence provided by entities affiliated with the US intelligence community, which appears to be a tampering of facts for the purpose of creating a negative image of Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea as bad actors in cyberspace. At the same time, it is in modern American strategic planning documents that the image of an external threat to freedom and democracy is already clearly formed, and the goal is declared to ensure peace by force, which involves identifying opponents and exerting influence on them by all available means. In fact, in the US, the policy of coercion has already become the norm. As an example, we can recall the case that occurred this summer, when The New York Times published an article alleging that US intelligence agencies allegedly carried out cyber attacks on Russian facilities related to the generation and transmission of electricity. It is still unclear what exactly the goals of this publication were - was it a leak of information, and, if so, was it intentional or accidental? Or maybe it was an information "stuffing". US President Donald Trump accused journalists of treason, and representatives of the US National Security Council said that there were no risks to national security.

However, if you follow the example of the RAND research group and look at the broader context, it becomes clear that against the background of the difficult relations between Russia and the United States, this publication was a clear signal of the policy of coercion.

Konstantin Asmolov:

North Korean hackers: the truth is not terrible

***

Peace through force does not imply the development of any generally acceptable mechanism for reducing tension in the ICT environment. And while, as the authors themselves point out, not all of the cases reviewed in the report are clear acts of cybercoercion, there is a need to develop means to detect early signs of cybercoercion and develop containment and resilience strategies. This is expected to be sufficient to successfully respond to cyber-coercion. The authors see no other way to solve the problem, except for the development of counteraction strategies (it can be assumed that using all available means, including through "public attribution").

In conclusion, the authors reiterate the thesis that in the case of cyber operations, there are no clear signals from states of either threats or expected behavior, let alone the means they can use for coercion. It is also argued that it is rather difficult to determine whether cyber operations directed against another country are intended to be coercive or otherwise. Perhaps here it makes sense to use Occam's methodological principle - "one should not multiply things unnecessarily." Indeed, as the authors postulate, ICT tools are actively used by many states to implement military-political tasks. However, if the purpose of a certain action is not to change the political behavior of another country, and there is no direct threat or use of force (which, by the way, violates the UN Charter), is there so-called coercion, or are we dealing with cyber activity that has become completely ordinary? A striking example of the policy of coercion, which the authors mention but do not consider, is related to the cyber attack on the facilities of Iran's nuclear program in 2010. First, there were demands from specific countries that Iran stop its nuclear program. Secondly, it was also about a possible strike if the requirements were not met. As you know, Iran did not change its policy, and the ensuing cyber attack was not an act of coercion or a limited show of force, but solved very specific tasks - Iran's nuclear program significantly slowed down development.