Psychosis after death loved one

Are Grief Hallucinations Common?

What grief does to your body isn’t yet fully understood. It may include hallucinations in some cases. But they may have a purpose.

Everyone experiences and expresses grief differently. There’s certainly no right or wrong way to mourn a loss. In some cases, this may include seeing or feeling the presence of a departed loved one.

Although rare, bereavement hallucinations are possible when someone’s in a heightened state of emotional pain.

What are hallucinations?

Hallucinations are perceptions that are unique to you and that others can’t perceive at the same time. For example, seeing, hearing, smelling, touching, or tasting something without a stimulus.

A grief hallucination may involve seeing, feeling, or hearing someone you’ve recently lost.

Yes, you can experience hallucinations of a loved one during your grieving time.

You may hear their voice or feel their touch, for example, or you may see their presence in places you go.

Dr. Joseph Shrand, a psychiatrist in Dedham, Massachusetts, explains that hallucinations come in two general categories:

- enjoyable “egosyntonic”

- not enjoyable “egodystonic”

These terms come from psychoanalysis. Egosyntonic refers to experiences that are consistent with your idea of self and your needs, likes, or goals.

Egodystonic refers to experiences that feel intrusive, offensive, hurtful, contradictory, or that you feel go against your sense of self.

Visions of a lost loved one tend to be egosyntonic hallucinations. They’re typically comforting and may make you feel like they’re still around, explains Shrand.

How common are grief hallucinations?

Since the early 1970s, research has indicated that bereavement hallucinations are commonplace.

Some of the most recent data, from 2015, indicates that as many as 60% of people who’ve lost their spouses report at least one grieving hallucinatory experience.

Research is inconclusive about what exactly causes someone to experience hallucinations of a loved one who has passed away.

Grief affects the body in many ways. Facing a loss may affect your mental and emotional health differently, although in most cases, the pain tends to decrease with time.

According to research on the neuroscience behind grief and loss, grieving can be a form of emotional learning. The brain may process the emotions related to grieving as a learning experience that helps reduce separation distress.

In other words, creating opportunities to feel like a part of your loved one is still with you might help you deal with intense emotional pain. Grief hallucinations may be the result of your brain trying to cope.

The same research suggests that prolonged grief disorder could be related to the brain having difficulty processing the loss.

Prolonged grief disorder, once known as complicated grief, is a condition listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5). You may be experiencing this long lasting grief if your pain doesn’t ease with time, escalates, or makes daily functioning a challenge.

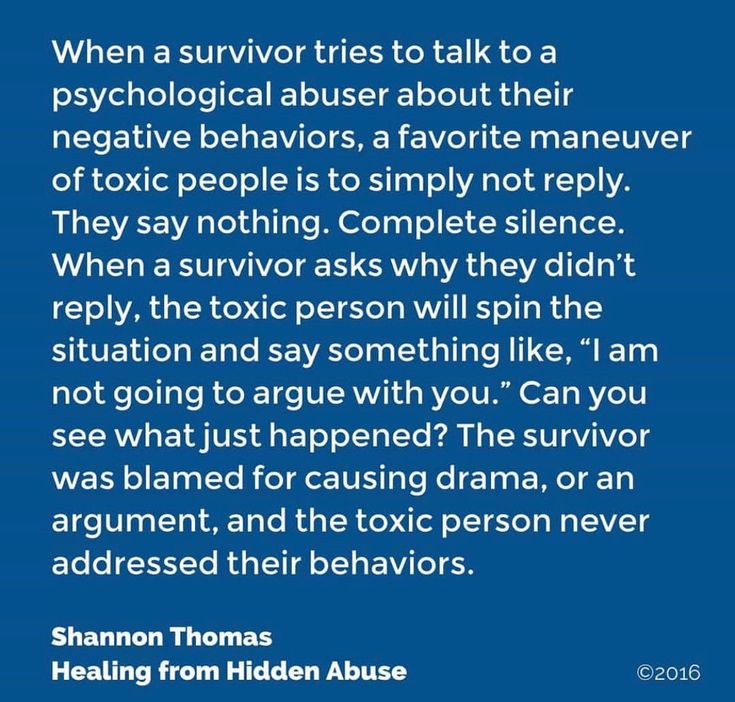

There is no compelling evidence that grief causes psychosis. However, 2014 research suggests that the unexpected death of a loved one may lead to experiencing mental health conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder.

In some cases, these conditions can appear with symptoms of psychosis, including hallucinations.

Psychosis is a mental state that occurs when your brain isn’t able to distinguish between what’s real in your environment and what isn’t.

It’s possible some people may experience hallucinations when facing the loss of a loved one, explains Barbara Rubel, a board certified expert in traumatic stress from Kendall Park, New Jersey. But, most people don’t experience an episode of psychosis when grieving, she adds.

While they might sometimes fit the hallucination diagnostic criteria, grief hallucinations may not necessarily be a lapse in reality.

Research suggests sensory experiences during mourning, particularly sensing the presence of a lost loved one, might come from a subconscious effort to maintain a connection to that person.

In a 2009 review on grief and bereavement, experts noted hallucinations during acute grief provided study participants with a sense of connection to the loved one, as did keeping mementos like clothing, pictures, or favorite possessions.

Depression vs. grief

Symptoms of depression can accompany grief, so how can you tell what’s clinical depression and what’s bereavement?

Uncomplicated grief — and the intense emotions it may cause you — will tend to get better in time.

Clinical depression, however, is a mental health condition that lasts longer than 2 weeks and lasts even in the absence of grief. It may also intensify with time if no formal treatment is sought.

People living with prolonged grief disorder are more likely to experience grief hallucinations, according to the DSM-5.

But it’s also possible that anyone grieving a recent and unexpected loss can experience them as well.

A 2009 literature review noted that these sensory experiences could be common immediately after the loss of a loved one.

“Anyone bereaved can experience a hallucination,” says Rubel. “However, there are many influences that impact grief, such as sudden death, traumatic death, suicide, a love/hate relationship, a young child, for example.”

The exact nature of bereavement sensory experiences is unclear.

By definition, seeing a loved one who has passed, hearing their voice, or feeling their touch are experiences that can be defined clinically as hallucinations.

What’s less clear is many people’s feeling of a loved one’s presence. Unlike traditional hallucinations, the perception that your loved one is near or in the same space as you isn’t clearly linked to one of your five senses.

It cannot be defined as a delusion either, another symptom of psychosis that refers to a firm belief that defies evidence.

Similarly, reminders of a loved one aren’t necessarily hallucinations. Smelling their essence when you’re in a store, for example, isn’t necessarily a hallucination.

The stimulus might be there — for example, a similar odor. You could associate the similarity to something familiar that makes you feel close to your lost loved one.

You could associate the similarity to something familiar that makes you feel close to your lost loved one.

If you’re experiencing vivid, disruptive, or disorienting sensory changes, a health professional can help you explore potential causes.

A mental health specialist can also help you work through the grieving process, especially if you feel you’re having a hard time coping with the emotional pain.

If bereavement hallucinations aren’t impairing or persistent, Shrand suggests allowing them to take a natural course.

“I would not try to convince the person they were hallucinating and deprive them of that comfort,” he says. “Some spouses talk to their departed loved ones for decades. Some parents know their child is contacting them even if they can’t see them. Rather than experience overwhelming loss, they find a way to keep that loved one close.”

Sensing a loved one who has passed, hearing their voice, or catching a glimpse of them can be sensory experiences known as bereavement or grief hallucinations.

Many people find these moments comforting. In fact, grief hallucinations are considered by some experts as a common feature of the bereavement process.

Some forms of grief, like prolonged grief disorder, may present with other mental health symptoms and may require professional attention.

Experiencing a grief hallucination doesn’t mean you’ve developed psychosis or another mental health condition. Sometimes, bereavement hallucinations may be your way of coping with a loved one’s loss.

If you’re finding it hard to cope with your loss, it may be a good idea to reach out to a support group or mental health professional.

Unexpected Death of a Loved One Linked to Psychiatric Disorders

The sudden loss of a loved one can trigger a variety of psychiatric disorders in people with no history of mental illness, according to researchers at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and colleagues at Columbia’s School of Social Work and Harvard Medical School. While previous studies have suggested there is a link between sudden bereavement and an onset of common psychiatric disorders, this is the first study to show the association of acute bereavement and mania in a large population sample. Findings are published online in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

While previous studies have suggested there is a link between sudden bereavement and an onset of common psychiatric disorders, this is the first study to show the association of acute bereavement and mania in a large population sample. Findings are published online in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

In people aged 30 years or older, the unexpected death of a loved one roughly doubled the risk for new-onset mania after controlling for prior psychiatric diagnoses, other traumatic experiences, and certain demographic variables like sex, race, income, education, and marital status. For those 50–54 years of age or ≥70 years, the risk increase was more than fivefold. There was no significant effect in people younger than 30 years.

The researchers analyzed data from 27,534 participants in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Between about 20% and 30% of these participants identified the unexpected death of a loved one as the most traumatic event in their lives. This was still the case among those reporting 11 or more lifetime traumatic events, where losing a loved one unexpectedly was most traumatic for 22%.

This was still the case among those reporting 11 or more lifetime traumatic events, where losing a loved one unexpectedly was most traumatic for 22%.

“Our findings should alert clinicians to the possible onset of a wide range of psychiatric disorders, including disorders such as mania, after an unexpected death in otherwise healthy individuals,” says Katherine Keyes, PhD, assistant professor of Epidemiology at the Mailman School, and principal investigator. “However, it is also notable that the majority of individuals in the present study did not develop mental health issues in the wake of an unexpected death of a loved one.”

Losing a loved one suddenly also raised the risk of major depression, excessive use of alcohol, and anxiety disorders, including panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and phobias. The largest risk increases were for post-traumatic stress disorder, which was seen across age groups with an increased risk as high as 30-fold. Most other disorders were concentrated in the older age groups.

While developing a psychiatric disorder for the first time in old age is relatively rare, these data indicate that psychiatric disorder onset in older age is commonly associated with the death of a loved one, according to the authors.

“Clinically, our results highlight the importance of considering a possible role for loss of close personal relationships through death in assessment of psychiatric disorders. When someone loses a close personal relationship, even late in life, there is a profound effect on sense of self and self-reflection. These data indicate that, even in adults with no history of psychiatric disorders, it is also a vulnerable risk period for the onset of a potentially disabling psychiatric disorder,” says Dr. Keyes.

Co-authors are Mailman School Department of Epidemiology’s Charissa Pratt, MPH, and Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH; Katie A. McLaughlin, PhD, Harvard Medical School; Karestan C. Koenen, PhD, Mailman School Department of Epidemiology; and M. Katherine Shear, MD, Columbia School of Social Work.

Dr. Shear received a contract from Guilford Press to write a grief treatment manual. The other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

This study was supported by NIMH grants MH-092526, MH-093612, MH-078928, MH-60783, MH-70741, and grant AA-021511 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

About Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health

Founded in 1922, Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health pursues an agenda of research, education, and service to address the critical and complex public health issues affecting New Yorkers, the nation and the world. The Mailman School is the third largest recipient of NIH grants among schools of public health. Its over 450 multi-disciplinary faculty members work in more than 100 countries around the world, addressing such issues as preventing infectious and chronic diseases, environmental health, maternal and child health, health policy, climate change & health, and public health preparedness. It is a leader in public health education with over 1,300 graduate students from more than 40 nations pursuing a variety of master’s and doctoral degree programs. The Mailman School is also home to numerous world-renowned research centers including ICAP (formerly the International Center for AIDS Care and Treatment Programs) and the Center for Infection and Immunity. For more information, please visit www.mailman.columbia.edu.

It is a leader in public health education with over 1,300 graduate students from more than 40 nations pursuing a variety of master’s and doctoral degree programs. The Mailman School is also home to numerous world-renowned research centers including ICAP (formerly the International Center for AIDS Care and Treatment Programs) and the Center for Infection and Immunity. For more information, please visit www.mailman.columbia.edu.

Experience of bereavement — Such cases

For the first time in Russia, the book Fundamentals of Palliative Care, edited by Robert Twycross and Andrew Wilcock, is published — the first fundamental manual on palliative care in Russian, prepared for publication by the Vera Hospice Foundation. "Things Like This" publishes a chapter from this book

Fundamentals of Palliative Care is a comprehensive guide covering all aspects of care for terminally ill people. This manual has been used by European specialists for more than 20 years, and now it is available to Russian-speaking medical students, doctors, and nurses. The book Introducing Palliative Care was first published in 1995 and after it was repeatedly reprinted in different languages of the world. The fifth edition of the book was translated into Russian in the 2016 edition.

The book Introducing Palliative Care was first published in 1995 and after it was repeatedly reprinted in different languages of the world. The fifth edition of the book was translated into Russian in the 2016 edition.

Dr. Robert Twycross is one of the pioneers of the hospice movement in the world. He taught a course in palliative medicine at Oxford and directed the WHO Collaborating Center for Palliative Care for 17 years. In Fundamentals of Palliative Care, Twycross has put together a detailed and comprehensive guide to managing palliative patients: treating painful symptoms associated with their illnesses, as well as communicating with relatives and loved ones.

Andrew Wilcock is Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and Fellow in Palliative Medicine and Oncology with the Macmillan Service at the University of Nottingham in the UK. Editor and one of the creators of the International Palliative Care Formulary, scientific consultant on prescribing drugs in palliative care of the British National Formulary.

Bereavement

The experience of loss is one of the most severe crises in life, which affects the health of a significant number of people. Bereavement support is one of the main elements of palliative care. It includes both caring for the patient's body after his death, and helping relatives and friends of the deceased. If the death of a person is expected, some of his relatives may experience "anticipatory (anticipatory) grief", in which case help in experiencing the loss can begin to be provided even before death.

The period of bereavement is the time of experiencing the death of a loved one, and grief is a reaction to longing and anguish that occurs after death. Grief is a transitional process during which people adjust to the reality of loss and learn to live without a deceased loved one. Grief is not just an emotional experience; it highlights behavioral, cognitive, physical, social and spiritual aspects. Thus, grief requires a holistic approach.

The experience of loss is associated with increased mortality, in particular from cardiovascular diseases, in the first months after the loss of a loved one. There is an increase in the frequency of somatic and mental illness, infections and alcohol abuse, as well as seeking medical help and psychotropic drugs.

There is an increase in the frequency of somatic and mental illness, infections and alcohol abuse, as well as seeking medical help and psychotropic drugs.

Patterns of grief

Grief is a deeply personal experience that people experience in different ways. Nevertheless, several typical stages can be distinguished, and on their basis, a number of models of grief experience.

They can be used to support those who are grieving, but the model is always a simplification and should therefore be used with caution. The sequential passage through the stages of experiencing grief is not typical. Usually people vacillate between different stages of such a path, which can lead to confusion both for themselves and those around them.

Grief is not a stable process. A person goes through a certain stage of this process, but then returns to it again. And so in a circle. All repeats.

Common reactions to bereavement:

Emotions

Anxiety; anger; anxiety; depression; guilt; feeling of loneliness; sense of relief

attitude

Despair; low self-esteem; self-criticism; a feeling of unreality of what is happening; social isolation; suspicion; longing for the deceased

Behavior

Alcohol abuse; increased fatigue; tearfulness

Physiological changes

Dry mouth; hair loss; headache; indigestion; insomnia; loss of appetite, weight loss; muscle pain; cardiopalmus; dyspnea; stress-induced disease, infection; the use of psychoactive substances; visual impairment

Therefore, one should not make hasty judgments about the stage of grief that a bereaved person is or should be in. Personal characteristics are of great importance. For people who rely primarily on their feelings, the experience of grief tends to be more in line with traditional patterns, while for people who tend to make sense of what is happening first, it becomes more of a cognitive process. To cope with a situation, such people search for information, think about problems, take action, and look for ways to distract themselves - this model is not necessarily associated with difficulties. In addition, the manifestation and expression of grief is culturally determined. In the UK and the US, self-confidence and independence are highly valued, which forces grieving people, especially if they are male, to suppress their emotions and not show that they are suffering.

Personal characteristics are of great importance. For people who rely primarily on their feelings, the experience of grief tends to be more in line with traditional patterns, while for people who tend to make sense of what is happening first, it becomes more of a cognitive process. To cope with a situation, such people search for information, think about problems, take action, and look for ways to distract themselves - this model is not necessarily associated with difficulties. In addition, the manifestation and expression of grief is culturally determined. In the UK and the US, self-confidence and independence are highly valued, which forces grieving people, especially if they are male, to suppress their emotions and not show that they are suffering.

The traditional model

The traditional model states that the process of grief consists of certain stages, but in reality one stage can occur simultaneously with another and unexpected changes are possible.

Numbness

The first reaction is shock and distrust, accompanied by a feeling of the unreality of what is happening and the mechanicalness of life (existence "on autopilot").![]() Somatic symptoms may or may not be present.

Somatic symptoms may or may not be present.

Separation and pain

Stupefaction gradually gives way to intermittent intense melancholy, anxiety, tension, anger and self-criticism. There is an irresistible desire to return the deceased. This can manifest itself in dreams and in the fact that a person hears the deceased and feels his presence, or excessively indulges in memories. There may also be an obsession to re-analyze the circumstances of the death. Somatic symptoms are common.

Despair

This stage occurs when the realization comes that the deceased person will not return. There are signs such as poor concentration, apathy, social withdrawal, lack of purpose, and deep sadness.

Acceptance

Despair gradually gives way to acceptance of the loss. Acceptance of the irreparable situation first occurs at the intellectual level, and later at the level of feelings. Sadness and emotional shifts can last for more than a year.

Decoupling and reorganization

Eventually, the grieving person begins to adapt to life without a deceased loved one: he rebuilds his personality and redefines goals, acquires new skills and assumes new roles. Gradually, lighter feelings appear, energy returns, new hobbies arise and relationships are born. At the memory of a departed loved one, emotions are no longer overwhelmed, however, anniversaries and memorable days cause a temporary aggravation of grief.

The normal course of life is interrupted by loss, which primarily causes shock, as well as numbness and denial. What follows is protest, accompanied by anger and guilt, followed by disorganization, as well as sadness, a feeling of loneliness and emptiness. And finally, a reorganization takes place, thanks to which a person can return to the original level of functioning, often changing his attitude to life and acquiring new values.

Bilateral process model

This model illustrates that the bereaved person oscillates between two extremes: bereavement activities (e. g., thinking about the deceased, yearning for them, reminiscing, expressing their feelings) and recovery activities, in which a person is looking for a way to distract himself in order to cope with everyday life (for example, suppresses memories, controls emotions, finds a business for himself).

g., thinking about the deceased, yearning for them, reminiscing, expressing their feelings) and recovery activities, in which a person is looking for a way to distract himself in order to cope with everyday life (for example, suppresses memories, controls emotions, finds a business for himself).

Orientation towards restoration allows a person to adapt and acquire a new self-identity, but since in everyday life there are many reminders of loss, he rushes between two types of behavior. The predominant behavior and degree of fluctuation of each individual will depend on personality factors, gender and cultural background. Over time, a person usually shifts from bereavement behavior to recovery behavior.

This model helps to understand why one day a person can look great and the next day he is grieving. Difficulties arise when a person tends to experience loss exclusively (chronic grief) or only to recovery behavior (absent grief).

Grieving parents may choose different types of bereavement experiences: one will be primarily bereavement-oriented, and the other will be recovery-oriented. This leads to tension between them as they cannot understand how each of them deals with grief.

This leads to tension between them as they cannot understand how each of them deals with grief.

Assistance in dealing with bereavement

The basis of support during bereavement is general quality assistance during the life of the patient, well-established communication and trusting relationships built with the family. The promptly carried out procedure for ascertaining and registering death, the removal of equipment and medicines from the house, and the willingness to answer questions help to alleviate the pain of loss in many ways.

Some of the health professionals who can provide bereavement care are general practitioners, community nurses, community palliative care nurses, and various bereavement support organizations.

There are special support groups for survivors of trauma or suicide of a loved one, stillbirth or death of a child, and support groups for bereaved children. After the death of a patient who was under the care of a hospice, for relatives of a patient with an increased risk of complicated grief, assistance in experiencing loss is officially provided.

For most people, it is enough to give them the opportunity to express their grief and support them by offering to talk about their feelings and listening carefully. This is of great therapeutic value and belongs to the mandatory skills of every medical worker. By far the most beneficial influence on bereavement outcomes is family and friends, who provide the necessary support and allow the person to express grief and speak freely about their experiences for as long as they need it.

The main task is to help a person find strength in himself and find his own ways to overcome it. Because some people are reluctant to ask for help, it's important to ask how they are coping with the situation. Often they need someone to confirm that their experience of grief is normal.

Bereavement reactions are either immediate or delayed; both short-term and long-term; both moderate and strong. Most bereaved people go through this period with the support of family and friends, and a healthcare professional who is willing to listen to them. About 10% need the help of a volunteer bereavement team or support group, and about 5% have complicated (pathological) grief that requires the participation of a psychologist or psychiatrist.

About 10% need the help of a volunteer bereavement team or support group, and about 5% have complicated (pathological) grief that requires the participation of a psychologist or psychiatrist.

In addition, it is important to provide support not only to family members, but also to caregivers, especially if the death was traumatic. For most of them, it is enough to give them the opportunity to express their grief in an atmosphere of support.

Complicated grief

Complicated grief is grief that leads to long-term physical and mental health problems.

His risk factors are listed below:

• premature and sudden death;

• death too severe;

• highly dependent, conflicting or difficult relationship with the deceased;

• poor social support;

• inability to talk openly with anyone and prepare for

death;

• anger, if it makes it difficult to provide support and leads to social isolation;

;

• Life circumstances that take away time and opportunity to deal with loss, such as financial hardship, lack of employment, needy children or elderly relatives;

• loss of loved ones in the past;

• the presence of a somatic or mental illness;

• history of alcoholism, drug addiction or suicidal behavior .

Complicated grief usually takes the form of extremes of normal grief. Formal criteria for complicated grief remain controversial. In addition, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) no longer includes complicated grief as a psychiatric diagnosis, but it also no longer lists bereavement as an exclusion criterion. major depressive disorder.

Complicated grief requires the help of psychologists and psychiatrists. In particular, the following treatments are possible: guided mourning; interpersonal (interpersonal) psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy and family-oriented grief therapy.

Short-term treatment with benzodiazepine hypnotics may help, but it is important to carefully monitor these prescriptions to prevent dependence.

For those who develop an apparent psychiatric disorder (eg depression, anxiety disorder, substance abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychosis), treatment will be provided in accordance with standard psychiatric practice.

the electronic version of the book can be read at pro-palliativ.ru

Even more important news and good texts from us and our colleagues - in the telegram channel "Takikh Del." Subscribe!

medicine palliative care psychological care

How to survive the death of a loved one?

Sorrow and grief are completely normal reactions to the loss of a loved one. If the next day after the death of a loved one, a person forgot about this event, continued to live a normal life and have fun, then either this person is mentally ill, or he is an alien. Grieving is always very difficult and painful, but the main thing is to consistently go through all the stages of loss, not to try to hide your feelings or drown them out with parties and alcohol. It is very important not to refuse the support of loved ones and to be able to ask for help in time. After all, it happens that grief drags on for a very long time and then you need to pull yourself together and use the services of a psychologist.

Of what stages does the experience of loss consist?

In the 1950s, American psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross developed a system of stages for accepting loss. These stages have been reviewed and criticized many times, but one way or another, all scientists studying this issue partly returned to the Kubler-Ross stages. The first reaction of a person to the loss of a loved one is the denial of the loss, due to shock. This can reach a painful mental reaction: a coffin with the body of his loved one is standing in front of a person, an autopsy has already been performed, but he continues to deny that his loved one has died.

I must say that not every person who has lost a loved one goes through all the stages of experiencing grief - someone needs only two or three steps on the way to a normal state.

Next comes the stage of anger: “Why did this happen to me, to my relatives? Why not with someone else? It may be anger that a loved one died, while others survived. This often happens after an accident, such as an accident. The man wonders why the one who was sitting next to him survived, and this makes him very angry. The third stage is bargaining. A person bargains with fate, for example, guessing that the missing person will return if the coin falls one way or another.

This often happens after an accident, such as an accident. The man wonders why the one who was sitting next to him survived, and this makes him very angry. The third stage is bargaining. A person bargains with fate, for example, guessing that the missing person will return if the coin falls one way or another.

The fourth stage is depression. A person begins to accept the loss, but loses interest in life. The fifth stage is acceptance, which can be accompanied by melancholy and apathy. However, a person comes out of apathy and begins to look for new ways to accept the loss, interest in life. Someone helps to plant a tree, give birth to a child, or, for example, establish a fund to help cancer patients - it depends on the situation. I must say that not every person who has lost a loved one goes through all the stages of experiencing grief - someone needs only two or three steps on the way to a normal state.

What stage of the experience of loss is the most dangerous for the psyche?

Denial, anger and apathy are probably the most dangerous stages of experiencing loss. Some people in the denial stage may develop psychosis: such patients claim that their loved one has not died and is about to return. Being at the stage of anger, a person is able to harm others, since at this stage anger is directed not at oneself, but at others, at the outside world. In this state, a person can break loose on the one whom he considers guilty of the death of a loved one, and begin to take revenge. If a person stays in a state of apathy for a long time, it can develop into clinical depression.

Some people in the denial stage may develop psychosis: such patients claim that their loved one has not died and is about to return. Being at the stage of anger, a person is able to harm others, since at this stage anger is directed not at oneself, but at others, at the outside world. In this state, a person can break loose on the one whom he considers guilty of the death of a loved one, and begin to take revenge. If a person stays in a state of apathy for a long time, it can develop into clinical depression.

See also

First aid for anxiety attacks

It happens that a person is not able to cope with his pain from loss on his own, and gets stuck in one of the stages of grief. If he only partially returns to normal life or does not return at all, his grief becomes pathological, and this already requires professional help. In part, he should begin to return to normal after three months. It is worth starting to worry if a person cannot fully recover from the loss of a loved one within a year.

How to cope with changes in life after the death of a loved one?

After the death of a loved one, any person asks the question “How to live now?” So that the stages of experiencing loss pass naturally, and the pain of a person is not so strong, you can help yourself and arrange your life so that the stages of grief pass a little easier.

In no case should you get drunk or use drugs in order to forget about your grief for a while - it is important to consciously live it.

It is advisable not to be alone and to be more often with friends who can provide support. This doesn’t mean that you have to go to fun parties all the time and distract yourself from grief, but occasionally going to quiet gatherings with friends can be healing. It is very important in such a situation to be able to ask for help. In no case should you get drunk or use drugs in order to forget about your grief for a while - it is important to consciously live it.

What to do if there is no social circle? Create this circle, make acquaintances, get close to people who can provide support. A person is almost always surrounded by relatives, friends, colleagues, and if they do not offer help, you need to contact them yourself.

After the loss of a loved one, a person may immerse himself in himself and begin to avoid communication with people. Some begin to abuse alcohol in an effort to drown out inner pain. And not everyone in this situation can have friends who will stop and help to cope with the loss. Then it is best to seek the help of a psychotherapist. Now in cognitive behavioral therapy there are well-designed programs for dealing with loss. The specialist helps the patient consistently go through all the stages of grief and return to normal life as soon as possible.

See also

Painful emotions

How to help a child cope with the loss of a loved one?

Adults should organize a busy daily routine for the child, which will include a variety of activities and socializing with friends.