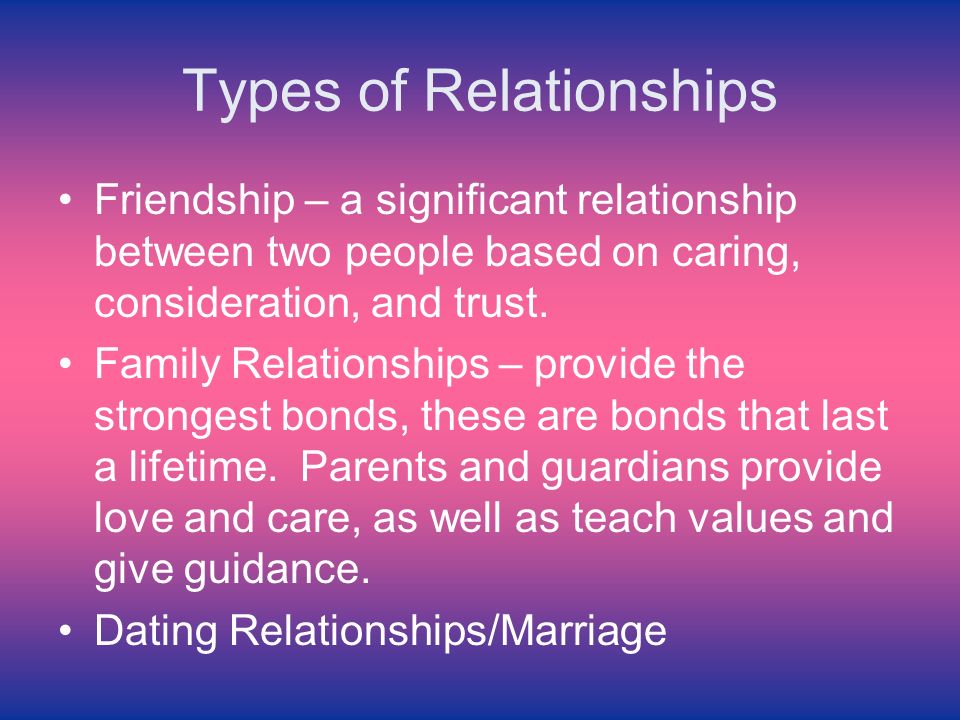

Psychological definition of friendship

The Three Basics of Friendship

Source: JohnnyGreig /iStock

Friendship may sometimes feel complicated, but it turns out that recognizing your true friends can be surprisingly simple. There are some fundamental elements that every close bond — including those with family and romantic partners — shares: To call someone a friend, the relationship must be long-lasting, it must be positive, and it must involve cooperation. That’s the three-legged stool that friendship rests on, say the evolutionary biologists I’ve been reporting on. Similar personalities or a shared sense of humor do matter, but they're less essential than you might think. Remove a leg of that stool, though, and your “friend” may not be there for you when you need them—and being able to count on someone in a crisis, say the researchers, is the whole reason we have friends in the first place.

Getting Serious About Friendship

This stripped-down definition of friendship is the result of a shift in how scientists think about social behavior. For a long time — centuries, really — serious scientists didn’t study friendship, because they didn’t much respect it. It was too squishy, too ephemeral, too hard to define and measure (and defining and measuring are essential to the scientific process).

But then primatologists — yes, the researchers who spend their time observing monkeys and apes — noticed that the animals they watched seemed to have friends, too. A debate ensued about whether it was appropriate to use the word “friend” when talking about animals. In the end, the scientists decided to call it like they saw it, and what they saw was friendship.

How could they tell? Because in animals, the researchers could measure the interactions between individuals, over the lifetimes of generations of baboons and macaques and chimpanzees. From those years of observation, they developed — for the first time — the basic, standard definition of a close social bond I’ve already cited. “Friendship is a long-term, positive relationship that involves cooperation,” says psychologist Robert Seyfarth of the University of Pennsylvania, who, with his wife, biologist Dorothy Cheney, spent decades observing baboons and vervet monkeys in Africa and is a pioneer in the field.

Animals actively work to build these friendship bonds. They do it, the theory goes, to avoid being eaten by predators. Multiple studies, by Seyfarth and others, have shown that animals with the strongest social networks live longest and have greater reproductive success. “What friendship is about at the end of the day,” says evolutionary anthropologist Robin Dunbar of the University of Oxford, “is creating small-scale, intensely bonded groups that act as protection [to life’s] stresses.”

It’s not hard to see the logic in that for humans as well. Studies have shown that people who are socially connected also live longer. Seen this way, the three essential ingredients of friendship make a lot of sense.

Monkeys spend a lot of the day grooming.

Source: Lydia Denworth

Investing Time

The more time we spend with our friends — talking, sharing a meal, going to a movie — the closer we usually become. Monkeys spend time together by grooming each other — for as much as 20 percent of their waking hours. But they don’t groom with all members of their troop equally; they pick and choose, just as we do, building bonds over time. All of it, says Dunbar, lays groundwork to help us cope with what lies ahead, whether it’s a lion or a lay-off. “If you need a shoulder to cry on,” says Dunbar, “you need to prepare that shoulder ahead of time.”

But they don’t groom with all members of their troop equally; they pick and choose, just as we do, building bonds over time. All of it, says Dunbar, lays groundwork to help us cope with what lies ahead, whether it’s a lion or a lay-off. “If you need a shoulder to cry on,” says Dunbar, “you need to prepare that shoulder ahead of time.”

Source: dean bertoncelj/Shutterstock

Accentuating the Positive

Grooming consists of picking dirt and bugs out of one another’s fur, but it also triggers endorphins and oxytocin, the neurotransmitters, or chemical messengers, that make monkeys feel good and bond them more closely to each other. Human activities like laughing, singing, dancing, and storytelling — those things we do with friends — trigger the same neurotransmitters. In other words, there’s biology behind the feeling that a real friend is someone you want to spend time with, and who makes you feel good. By contrast, unpleasant interactions set off our stress responses.

Being Helpful

All that investing of time and good feeling only pays off if, eventually, your friend is there to help when you need it and vice versa — to bring dinner over in a crisis, to help you move. The two of you must cooperate. When you don’t — when a relationship feels too lopsided — it often fades away, or it should, because you need to invest in someone else.

On average, research shows that most of us have about five people in our lives who meet these three criteria, and those are the people we count as our most intimate friends. Who are yours? And are you doing everything you should to ensure that you will be able to count on each other when necessary?

The psychology of friends | BPS

‘Friendship is the single most important thing affecting our psychological health and wellbeing, as well as our physical health and wellbeing.’ Spending time with our friends releases endorphins in the brain and makes us happy. This is Professor Robin Dunbar’s response to the Wellcome Collection’s latest exhibition ‘On Happiness’, and there is a wealth of research that might back up his statement.

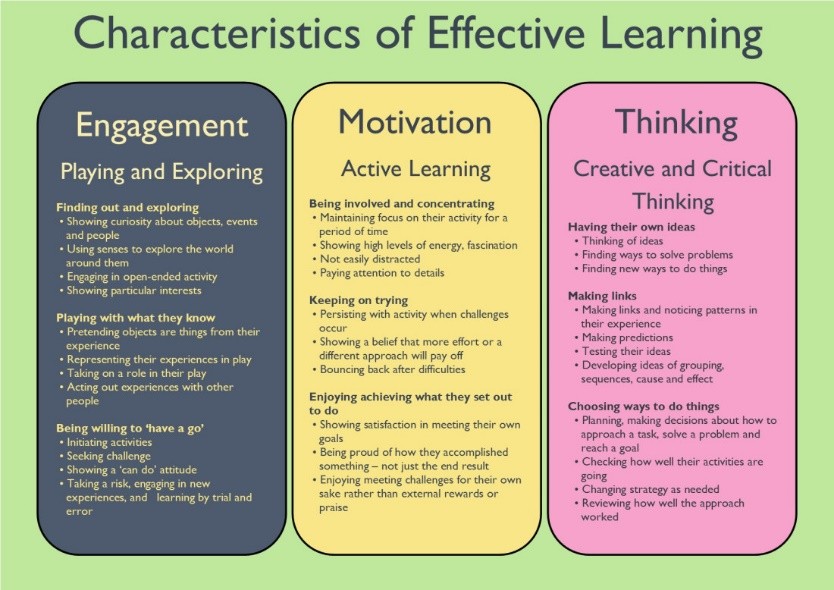

Indeed, good friendships may be essential for wellbeing at every stage of life. Making friends is crucial for children in their development and ability to form later relationships. And the bedrock of childhood friendships may start with play – which hones social and communication skills.

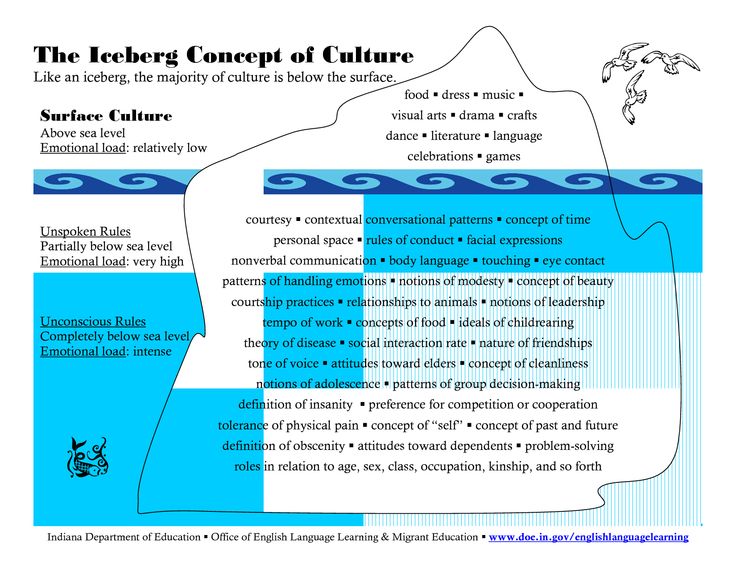

The way we connect with our friends may change as we get older, or as technology opens up new ways of connecting. Teenagers today can harness social media to communicate with friends in a way previous generations could not. They may have different types of friendship, with online and offline groups of friends – that may or may not overlap.

Social connectedness and depression

Many studies suggest that having healthy friendships could have a protective effect on health and help us age better. Some research has examined whether social networks could influence mortality, heart attack survival, depression and anxiety. Our social networks (the ties we have) can affect our moods, with some evidence suggesting that feelings such as happiness can spread through a network.

Being a member of a social group, for example a book club or sports team, may carry its own health benefits. This is because the sense of belonging and friendship may be key to our social identity, which in turn can influence health. For example, studies show links between social connectedness and depression. Being a member of a low-status or stigmatised group may harm health, but at the same time this group membership can counter negative health effects, for example by providing social support.

Contact theory

Friendship may also be pivotal in boosting societal harmony. Contact theory - the idea that positive contact such as friendships between different groups can promote positive attitudes, has been studied as a way to reduce prejudice towards immigrants and promote intercultural relations. For example, studies in children have shown that white British schoolchildren with friends of south-Asian origin tended to have more positive attitudes towards those of south-Asian origin.

We also value friendship in our cultural life. The book, Dr Who Psychology, looked at the ideal sidekick for the Time Lord Dr Who, and suggested that as well as being highly empathetic and resilient, they might have traits in common with polar explorer Ernest Shackleton’s ideal travelling companion too. The developing friendships of children also provide fascinating fodder for TV, inspiring programmes such as The Secret Lives of 4 Year Olds.

The flipside of friendship

But are there downsides to friendship? Certainly, feeling socially rejected can be painful, especially for teenagers. And one in three children may experience the flipside of friendship – enemyship or ‘antipathetic relationships’, at any given time according to research. Teen friendships can be complicated, with former friends or current ‘frenemies’ more likely to bully within their own social circle.

The current Covid-19 pandemic means that reinvigorating our social connections may be especially important, particularly for new mothers. Psychologists have been aware of how children may have been impacted by time away from friends and have called on the UK government to prioritise play for children. Lockdown loneliness may have particularly profound effects in older adults, especially those with dementia.

Psychologists have been aware of how children may have been impacted by time away from friends and have called on the UK government to prioritise play for children. Lockdown loneliness may have particularly profound effects in older adults, especially those with dementia.

Repeated lockdowns have made us rethink the ways we stay in contact with friends. While social media is one way of keeping in touch, some people have discovered the value of online games such as Among Us and Animal Crossing to connect with friends.

Over on our Research Digest we’ve summarised lots of studies on friendship:

Are you addicted to spending time with your friends? Study satirises measures of social media addiction – Matthew Warren

School-age kids, but not preschoolers, understand that divulging a friend’s secret could damage the friendship – Emma Young

We prefer to experience good – and bad – events on the same day as a friend – Emma Young

How sharing a toilet helps students make more friends – Alex Fradera

People prefer strangers who share their political views to friends who don’t – Emily Reynolds

Struggling to stick to a workout routine? Copying your friends might help – Emily Reynolds

We’re worse at remembering exactly what we’ve given to friends than what we’ve given to strangers – Emma Young

Here’s why we eat more when we’re with friends and family – Emily Reynolds

Kids As Young As Five Underestimate How Much Their Peers Like Them – Emma Young

The “liking gap” – we tend to underestimate the positive first impression we make on strangers – Emma Young

Find more using the search function on the Research Digest

Friendship - Human Psychology

Friendship is content with the possible, without demanding what is due.

Aristotle

We all have a certain general idea of friendship, thanks to which we expect a certain return from it. And at the same time, each person understands it in his own way, depending on what beliefs he holds. Someone sees in friends people who can understand and support in difficult times, with whom you can share something intimate, someone is ideological like-minded people who are ready for anything for the sake of a common great goal, and someone who can simply take advantage of them by violating their trust. No matter how this or that person understands friendship, no matter what he expects from it, one thing remains unchanged, friendship brings people together for a while and imposes unspoken obligations on them. Over time, it can change a lot, depending on how friendly people treat each other and what they require from each other. And in some cases, unfortunately, even a very good and strong friendship can end in enmity and mutual hostility. In this article, I want to share with you my experience of solving such problems and help you prevent their occurrence by forming in you the correct [from my point of view] idea of friendship and its values.

What is friendship

There is a classic definition of friendship, according to which friendship is a disinterested relationship between people based on common interests, values, hobbies, as well as on mutual respect and mutual assistance. You can learn this without me from dictionaries and encyclopedias.

But if we talk about friendship as the cause of possible [and often inevitable] problems that may arise between people, then I would give this concept a slightly different definition. In my opinion, friendship is a certain expectation of a person from those whom he considers his friends. That is, unlike, say, just acquaintances or work colleagues, a friend is perceived by many people as a person who owes them something. And, of course, they owe him something too. Friendship can be compared to partnership, only without clearly defined conditions and rules. Friends seem to do everything voluntarily for each other, not counting who did more or less for whom. For mercantile people who love to use others for their own purposes, friendship is very convenient, because they can always calculate its benefits for themselves. And someone doesn’t even really understand why and for what he is friends with someone, but the need for close people who are at least somewhat interested and need you forces them to hold on to their friends, even if they are not entirely decent and honest.

And someone doesn’t even really understand why and for what he is friends with someone, but the need for close people who are at least somewhat interested and need you forces them to hold on to their friends, even if they are not entirely decent and honest.

Thus, in relation to many situations, I can say that friendship allows people to receive something valuable and necessary from each other completely free of charge, without any clear and precise conditions and mutual obligations. If an outsider needs to pay for certain services or give something in return, then the same can be obtained from friends without any payment and exchange, simply by asking them for help. They, too, can ask for something later, but this can be reacted to in different ways, including a justified refusal, because all obligations between friends are voluntary. So we can say that the essence of friendship is to pursue our own selfish interests through such unconditional cooperation with other people whom we call our friends. Often this selfish component of friendship is not even realized by many. People assure themselves and others that they are friends with someone not at all because of their selfish interests, but because they like the person, because they have a lot in common, and so on. In general, as a rule, friendship is given a noble look, without any “you - to me, I - to you” there. However, it has been noticed by me and others that there are always more people who want to be friends with rich and powerful people than with the poor, stupid and sick, from whom there is nothing to take.

Often this selfish component of friendship is not even realized by many. People assure themselves and others that they are friends with someone not at all because of their selfish interests, but because they like the person, because they have a lot in common, and so on. In general, as a rule, friendship is given a noble look, without any “you - to me, I - to you” there. However, it has been noticed by me and others that there are always more people who want to be friends with rich and powerful people than with the poor, stupid and sick, from whom there is nothing to take.

Problems with friends

Problems with friends, which people usually have and with whom I most often had to deal, were mainly related to excessive demands and unjustified expectations. People unreasonably placed excessive obligations, great responsibilities and high demands on their friends. Since you are my friend, then you must this, you must this. There can be very many such imposed debts, depending on the person's beliefs regarding friendship. They are not immediately and not always openly voiced, but people make demands on friends, guided by just such convictions. And who wants to be indebted to someone, obligated, to take responsibility for another, contrary to their desire and capabilities? This is how misunderstandings appear, just like in family life, when spouses argue with each other about who has done more for whom.

They are not immediately and not always openly voiced, but people make demands on friends, guided by just such convictions. And who wants to be indebted to someone, obligated, to take responsibility for another, contrary to their desire and capabilities? This is how misunderstandings appear, just like in family life, when spouses argue with each other about who has done more for whom.

Of course, conflicts between friends arise all the time, and to be even more precise, conflicts between people, especially acquaintances, have always been and will be. But basically, only those that are caused by chronic disagreements and accumulated grievances lead to serious negative consequences. It always seems to a person that he gives others more, but receives much less from them, because of this he comes to the conclusion that he is being used, deceived, he is not considered, his interests are ignored, he is not respected. And as a result, he begins to first take offense at people, in particular at his friends, then get angry at them, and then, because of the accumulated anger, the person begins to put pressure on his friends and make claims to them. In some cases, this happens gradually, in the form of regular criticism and moralizing edification, but more often in the form of an emotional outburst, when a person at one fine moment expresses to his friend or friends everything that he thinks about them. And he thinks about them in such cases badly or very badly. After that, the relationship deteriorates or completely collapses. This is what it means, unspecified and unconscious by many people, partnership, which they call friendship and in which everyone expects from another person - a friend, something that he cannot or does not want to give.

In some cases, this happens gradually, in the form of regular criticism and moralizing edification, but more often in the form of an emotional outburst, when a person at one fine moment expresses to his friend or friends everything that he thinks about them. And he thinks about them in such cases badly or very badly. After that, the relationship deteriorates or completely collapses. This is what it means, unspecified and unconscious by many people, partnership, which they call friendship and in which everyone expects from another person - a friend, something that he cannot or does not want to give.

In addition, people may misjudge the very situation they have with their friends. Imagine a man comes to you and says that his best friend betrayed him. And you start to figure it out and it turns out that it was not a friend who betrayed a person, but a person placed on a friend and friendship with him, too high and unjustified expectations. He idealized friendship, saw in it certain benefits, a certain meaning, which, in fact, were not in it. It turns out that it was not his best friend who betrayed him, but he betrayed himself, and not when a friend disappointed him with his behavior, actions, thereby not justifying his expectations and hopes, but when he placed these very expectations and hopes on this friend and his own. friendship with him. Therefore, one should not be fascinated by people more than necessary, so as not to be greatly disappointed with them later. We all know that people are selfish by nature, for some egoism is less reasonable, for others it is quite healthy and practical. But when a person establishes friendly relations with someone, what egoism does he focus on in the first and often the only place, evaluating his friend? As a rule, on a healthy, reasonable and practical, right? We expect honesty, decency, responsibility, reasonableness in our actions and adequate selfishness from other people, in which our interests will not suffer, without thinking about whether this particular person can be exactly the way we want to see him.

It turns out that it was not his best friend who betrayed him, but he betrayed himself, and not when a friend disappointed him with his behavior, actions, thereby not justifying his expectations and hopes, but when he placed these very expectations and hopes on this friend and his own. friendship with him. Therefore, one should not be fascinated by people more than necessary, so as not to be greatly disappointed with them later. We all know that people are selfish by nature, for some egoism is less reasonable, for others it is quite healthy and practical. But when a person establishes friendly relations with someone, what egoism does he focus on in the first and often the only place, evaluating his friend? As a rule, on a healthy, reasonable and practical, right? We expect honesty, decency, responsibility, reasonableness in our actions and adequate selfishness from other people, in which our interests will not suffer, without thinking about whether this particular person can be exactly the way we want to see him. And it is our problem, not his problem, that he does not meet our requirements. And if his subsequent behavior destroys many of our illusions, then this will be a pattern, not a surprise.

And it is our problem, not his problem, that he does not meet our requirements. And if his subsequent behavior destroys many of our illusions, then this will be a pattern, not a surprise.

When a person does not understand what his friendship with someone is like, he expects from her, from his friends or a friend, such decisions and actions that only according to his convictions should take place. We all have some stereotypical ideas about what a real friend should do, how he should act. But what does it mean should? How is this debt formalized when people become friends? After all, no one agrees with each other in advance about what their friendship will be like, who and what will do for the other, what obligations each of the friends undertakes and how he will report on them. Everyone enters into this form of relationship with their own beliefs about it, without any agreements, even verbal, everything happens by itself.

Friendship is a partnership, if we consider it from the point of view of obligation. But it, this partnership, is voluntary and does not imply the discussion of any specific obligations and sanctions for their non-fulfillment. So, to wait and even more so to demand, but it’s better to just ask, from a person you can only do what he wants and is ready to give, being your friend.

But it, this partnership, is voluntary and does not imply the discussion of any specific obligations and sanctions for their non-fulfillment. So, to wait and even more so to demand, but it’s better to just ask, from a person you can only do what he wants and is ready to give, being your friend.

Betrayal of friends

Betrayal of friends, as well as betrayal of people in general, is a phenomenon that is not that common, but occurs quite often. People are far from perfect in this matter, so when it is possible to betray someone for their own selfish interests or out of fear, then even if it is about best friends, they would rather do it than not. Because it's easier. Setting up a friend and getting something for it or running away, leaving a friend in trouble, is always easier than remaining loyal to him. Of course, as a person who constantly works with various human problems, I may have a biased attitude towards the topic of betrayal, because people often turn to me with this problem. And, of course, sometimes it begins to seem to me that this happens often, that people constantly betray each other. But I get rid of such a trap of perception, which narrows my worldview and thinking, by communicating with these people on the topic of more successful relationships that they had or that they know about, when no one betrays anyone, thereby helping both them and myself more look at this issue objectively. People do not always do bad things to each other, they also do a lot of good things when they are friends.

And, of course, sometimes it begins to seem to me that this happens often, that people constantly betray each other. But I get rid of such a trap of perception, which narrows my worldview and thinking, by communicating with these people on the topic of more successful relationships that they had or that they know about, when no one betrays anyone, thereby helping both them and myself more look at this issue objectively. People do not always do bad things to each other, they also do a lot of good things when they are friends.

This is the good thing you should pay attention to when evaluating your friendship with someone. This will help to evaluate the quality of friendship. After all, it may turn out that what a person calls betrayal is only the bar of the capabilities of his friend or friends, which he or they have not been able to overcome by giving up. Any person can break down when he encounters certain circumstances, and then one or another of his weaknesses will manifest itself and he will make a choice not in favor of his friend, but in favor of himself or someone else. Difficulties allow you to evaluate the quality of a friendship by comparing what a friend gives you with what they betray you for. No wonder they say that a friend is known in trouble. Everyone can betray, but not everyone before they betray can benefit you. In addition, if you do not subject a person to overwhelming tests for him, then he will not betray you. You know that your friend is weak on something, so do not trust him in this matter, be prudent. Difficulties break people, only some people are broken by some difficulties, and others by others. Someone is ready to betray you at the very first sharing of something, for example, money, which not everyone is able to resist. And someone in more serious situations breaks down when it comes to life and death, when a person is simply not ready to sacrifice everything for a friend, friends. And in order not to be killed about his betrayal, if it happened, you should think about why he did it, how difficult the situation in which you were betrayed was really difficult for your friend and how you yourself would act in his place.

Difficulties allow you to evaluate the quality of a friendship by comparing what a friend gives you with what they betray you for. No wonder they say that a friend is known in trouble. Everyone can betray, but not everyone before they betray can benefit you. In addition, if you do not subject a person to overwhelming tests for him, then he will not betray you. You know that your friend is weak on something, so do not trust him in this matter, be prudent. Difficulties break people, only some people are broken by some difficulties, and others by others. Someone is ready to betray you at the very first sharing of something, for example, money, which not everyone is able to resist. And someone in more serious situations breaks down when it comes to life and death, when a person is simply not ready to sacrifice everything for a friend, friends. And in order not to be killed about his betrayal, if it happened, you should think about why he did it, how difficult the situation in which you were betrayed was really difficult for your friend and how you yourself would act in his place. The correct logic, which allows one to assess the real capabilities of a person, his weaknesses, character, beliefs that influence his actions, can very well help to understand the reason for his treacherous act, and even prevent it. Remember that each of us can betray, it all depends on the circumstances in which we find ourselves. A thin branch breaks quickly, a thick stick is much more difficult to break.

The correct logic, which allows one to assess the real capabilities of a person, his weaknesses, character, beliefs that influence his actions, can very well help to understand the reason for his treacherous act, and even prevent it. Remember that each of us can betray, it all depends on the circumstances in which we find ourselves. A thin branch breaks quickly, a thick stick is much more difficult to break.

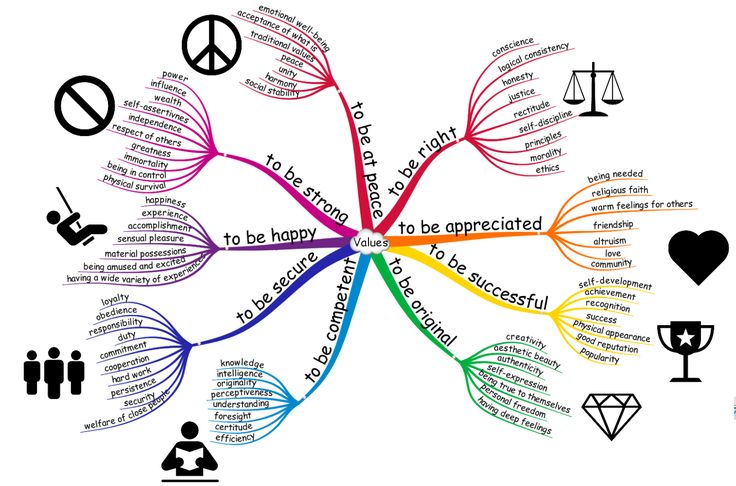

It is also not uncommon for people to befriend someone, like you, for some benefit. This is a kind of friendship of convenience or necessity, when you are simply convenient for a person at a given time. And as long as he needs you for something, he is with you, and as soon as the benefit from you disappears, friendship will evaporate with it. Such temporary friends are recognized by their fickleness and greed. They are always looking for the best options, the best, in their opinion, and do not hold on to anything, especially people. They can run from job to job because of insignificant benefits, and often change their place of residence, thinking that it is better where they are not. It is even difficult for such people to determine their life values, because they want the best for themselves, but do not understand what it is. They do not have a fundamental value base from which they could build on their decisions, especially with a long-term perspective. Today they want one thing, tomorrow another, the day after tomorrow a third. So if you are friends with such people, then only for the sake of temporary interests. You can't really trust them with anything. Remember that you choose your own friends and agree to be friends with someone, so you should always know why someone agrees to be friends with you, in which he sees her attractiveness for himself. And you can adjust to the interests of this person, knowing in advance where and when they can end.

It is even difficult for such people to determine their life values, because they want the best for themselves, but do not understand what it is. They do not have a fundamental value base from which they could build on their decisions, especially with a long-term perspective. Today they want one thing, tomorrow another, the day after tomorrow a third. So if you are friends with such people, then only for the sake of temporary interests. You can't really trust them with anything. Remember that you choose your own friends and agree to be friends with someone, so you should always know why someone agrees to be friends with you, in which he sees her attractiveness for himself. And you can adjust to the interests of this person, knowing in advance where and when they can end.

Well, it would not be superfluous to say that no one in this world, even the best friends, can be completely trusted. Maybe it's hard, and sometimes impossible, but it's smart and we should strive for this. The most serious people with whom I had the opportunity to communicate and work were very distrustful. And given their life experience, it was quite justified. They treated people well, with understanding, they just never fully revealed themselves to them and tried to predict their behavior in certain situations, based not on their words, but on previous actions. After all, sometimes a person himself does not know what he is capable of, if he encounters some kind of problem or some kind of temptation. We want to believe that we are capable of acting intelligently in any situation, but we often act very unpredictably even for ourselves, especially when faced with situations that are unusual for us. Therefore, often the betrayal of friends is spontaneous. As people who betrayed someone in their lives told me, it's all about the circumstances that have developed in such a way that they had no choice. Of course, there is always a choice, and with honor you can get out of many situations without betraying or substituting anyone. But this requires special qualities from a person. And in order not to think or guess about the extent to which your friend is reliable and faithful to you, it is better not to trust him too much, allowing for the idea that under certain circumstances he will be forced to betray you.

And given their life experience, it was quite justified. They treated people well, with understanding, they just never fully revealed themselves to them and tried to predict their behavior in certain situations, based not on their words, but on previous actions. After all, sometimes a person himself does not know what he is capable of, if he encounters some kind of problem or some kind of temptation. We want to believe that we are capable of acting intelligently in any situation, but we often act very unpredictably even for ourselves, especially when faced with situations that are unusual for us. Therefore, often the betrayal of friends is spontaneous. As people who betrayed someone in their lives told me, it's all about the circumstances that have developed in such a way that they had no choice. Of course, there is always a choice, and with honor you can get out of many situations without betraying or substituting anyone. But this requires special qualities from a person. And in order not to think or guess about the extent to which your friend is reliable and faithful to you, it is better not to trust him too much, allowing for the idea that under certain circumstances he will be forced to betray you.

Keep in mind that the severity of any betrayal is determined by your dependence on the one who betrayed you. The less he knows about you and the less you need him, the easier it will be for you to survive the conflict or parting with this person after he betrays you.

Friends and Enemies

In this world, it is impossible to live any kind of active life and not have enemies. No matter how wonderful a person you are, if you don’t sit at home all day long, but actively do something, meet and communicate with people, solve some problems, then you will definitely cross the road for someone somewhere. And you may have enemies. And if there are enemies, then allies are needed. Not always they can and should be friends, they can also be enemies of your enemies, who are also your potential enemies, but due to the circumstances they are ready to cooperate with you. However, seeking help from those who are able to be your friend is still preferable. Friendship can bind more obligations than a temporary union. That is why we are friends against someone or for something, in order to solve with the help of people for whom something is significant and valuable in some way, one or another of our problems. Only in this case it is necessary to purposefully and competently choose your friends, with a clear and precise calculation, so that, trying to establish friendly relations with people who have some significant opportunities for you. This, I repeat, is a calculation, such friendship is created not for spiritual comfort, but for the deeds that you do and the problems that you solve. Therefore, you may not really like such friends of yours, but such friendship is useful to you.

That is why we are friends against someone or for something, in order to solve with the help of people for whom something is significant and valuable in some way, one or another of our problems. Only in this case it is necessary to purposefully and competently choose your friends, with a clear and precise calculation, so that, trying to establish friendly relations with people who have some significant opportunities for you. This, I repeat, is a calculation, such friendship is created not for spiritual comfort, but for the deeds that you do and the problems that you solve. Therefore, you may not really like such friends of yours, but such friendship is useful to you.

In addition, your enemies, if you know them, can also become your friends if you find a way to connect their interests with yours. You can make some concessions to your enemies for this, thus extending the hand of friendship to them. In some cases, you should generally understand the reasons for your disagreements and understand when and how your enmity began. How many times have I come across situations where people were at enmity with each other, while having many common interests and not remembering even the very first reason for enmity. It’s just that once something became a bone of contention for them, emotions took over the mind and the conflict that arose, aimed at harming each other, grew like a snowball over time. And if you try to decompose all mutual grievances and claims and compare them with the benefits that people can get from making peace and creating friendly relations, then it may turn out that friendship is much more useful for them than their senseless enmity. In this way, you cannot turn all enemies into your friends, because it is impossible to combine some interests in principle, but at least try to simplify your life by finding grounds for friendship and ending hostility, I think it is very useful. I did this kind of work with people and was very pleased with its positive results. Smart people should be friends and cooperate, not harm each other and hate each other.

How many times have I come across situations where people were at enmity with each other, while having many common interests and not remembering even the very first reason for enmity. It’s just that once something became a bone of contention for them, emotions took over the mind and the conflict that arose, aimed at harming each other, grew like a snowball over time. And if you try to decompose all mutual grievances and claims and compare them with the benefits that people can get from making peace and creating friendly relations, then it may turn out that friendship is much more useful for them than their senseless enmity. In this way, you cannot turn all enemies into your friends, because it is impossible to combine some interests in principle, but at least try to simplify your life by finding grounds for friendship and ending hostility, I think it is very useful. I did this kind of work with people and was very pleased with its positive results. Smart people should be friends and cooperate, not harm each other and hate each other.

Speaking of friends and enemies, it is also important to know that your most cunning and insidious enemies can seek friendship with you, who do not openly express their aggression and antipathy towards you, but, on the contrary, demonstrate friendliness and a friendly attitude. After all, friendship is the best way to get as close as possible to a person, which will make it possible to deal him a crushing blow. Usually such blows are delivered through the disclosure of some confidential information, when a friend reveals some important secret about you that you have entrusted to him. You can also be framed or forced on you by a harmful "friendly" opinion, because of which you will make serious mistakes. Therefore, a clear enemy is not so terrible, whose intentions and goals you can see and therefore do not trust him and always be on the alert with him, like a friend who can become your enemy, knowing all your weaknesses. But especially terrible are the enemies who pretend to be your friends, to whom you can open yourself completely, thanks to their impeccable behavior and kind treatment of you. On the same flattery, you can go far, using it in order to please a person. So friendship, like love, can be poisonous.

On the same flattery, you can go far, using it in order to please a person. So friendship, like love, can be poisonous.

Often, hostility towards best friends is explained by the fact that they seem to a person to be a weaker victim, along with relatives, than strangers who perceive them more critically. Friends are easier to deceive than strangers because the friend trusts you with common stereotypes about friendship. He is ready to sacrifice something for you, ready to yield to you in something, because you are his friend. And that is why some unscrupulous people offer something disadvantageous in the first place to their friends and relatives, who treat them with trust and respect. It is easy to deceive someone who trusts you and this is a great temptation that not every person can resist. Also, many professional traders of different levels can become your friends, enveloping you with their flattery, emphasizing your uniqueness and exclusivity, demonstrating their concern for you in order to gain confidence in you, win you over, become your friend with whom you rather agree than not, and for whom you will do much more than for an outsider. Therefore, it is important to remain vigilant and not believe in disinterested and sacrificial friendship, especially from people who are unfamiliar and untested by time and difficulties, even if such friendship exists. Friendship, like love, weakens and weakens a person, which makes him a rather attractive victim for those who do not miss the opportunity to take advantage of someone's weakness.

Therefore, it is important to remain vigilant and not believe in disinterested and sacrificial friendship, especially from people who are unfamiliar and untested by time and difficulties, even if such friendship exists. Friendship, like love, weakens and weakens a person, which makes him a rather attractive victim for those who do not miss the opportunity to take advantage of someone's weakness.

Friendship between a man and a woman

Very briefly about whether there can be true friendship between a man and a woman that does not spill over into a closer relationship. I am asked this question from time to time by people who are trying to figure out the state of their relationship with the opposite sex. Someone thinks that no, there can be no such friendship, except perhaps only temporarily. But there are those who not only believe in such friendship, but also have it. I believe that, of course, such friendship does exist. In fact, I know she is. You don't often see her, but you can't call her a myth either. You just need to understand that such friendship can be maintained by special people who can control their desires and behavior and see the meaning in it. And there are few such people. There are many more who give in to their passions and follow their weaknesses. That is why true friendship between a man and a woman is rare.

You just need to understand that such friendship can be maintained by special people who can control their desires and behavior and see the meaning in it. And there are few such people. There are many more who give in to their passions and follow their weaknesses. That is why true friendship between a man and a woman is rare.

Ideal friendship

And finally, let's talk about what should be the ideal real friendship found in life, and not in smart books and articles. You and I can tell a lot about ideal friendship, based on our desires, ideas about it, the opinions of other people that we once liked. But in real life, just such an imaginary real friendship is rare. Therefore, it makes sense to talk more about such an ideal, to which someone has already managed to come and therefore it is within our power to achieve. So, ideal friendship, in my opinion and according to my observations, is such a friendship in which people - friends place adequate hopes, expectations, demands and responsibilities on each other [corresponding to their capabilities]. We have the right to take from people what they can and want to give us and give in return what we can and want to give, thus emphasizing the value for us of friendship with this person.

We have the right to take from people what they can and want to give us and give in return what we can and want to give, thus emphasizing the value for us of friendship with this person.

It is clear that in any relationship between people there will be a place for self-interest, there is no way out of this, and there is no need to leave. But, as in the relationship between a man and a woman, friends should not see each other as executors of their desires and their servants. Friendship is not a service to demand much from it. Too much demands on a person will inevitably lead to conflicts with him. Sometimes they are latent, and sometimes open. Because of these conflicts, there is mistrust between people, misunderstanding by them of each other. Because the conflict causes emotions, naturally, negative ones, and then emotions further spin and complicate the conflict, introducing new grievances into it. They confuse the mutual demands of people to each other, deprive them of the ability to think flexibly and constructively, narrow their view of the situation, limit their choice of ways to solve it. And for an ideal, as far as possible, and real friendship, you just need to learn to be content with what she gives you and give her what you need to give in order to keep her.

And for an ideal, as far as possible, and real friendship, you just need to learn to be content with what she gives you and give her what you need to give in order to keep her.

📖 5. PSYCHOLOGY OF FRIENDSHIP. Friendship: Ethical and psychological essay. Kon I. S. Page 6. Read online pdf

I have a friend, I love, so I exist.

M. Prishvin

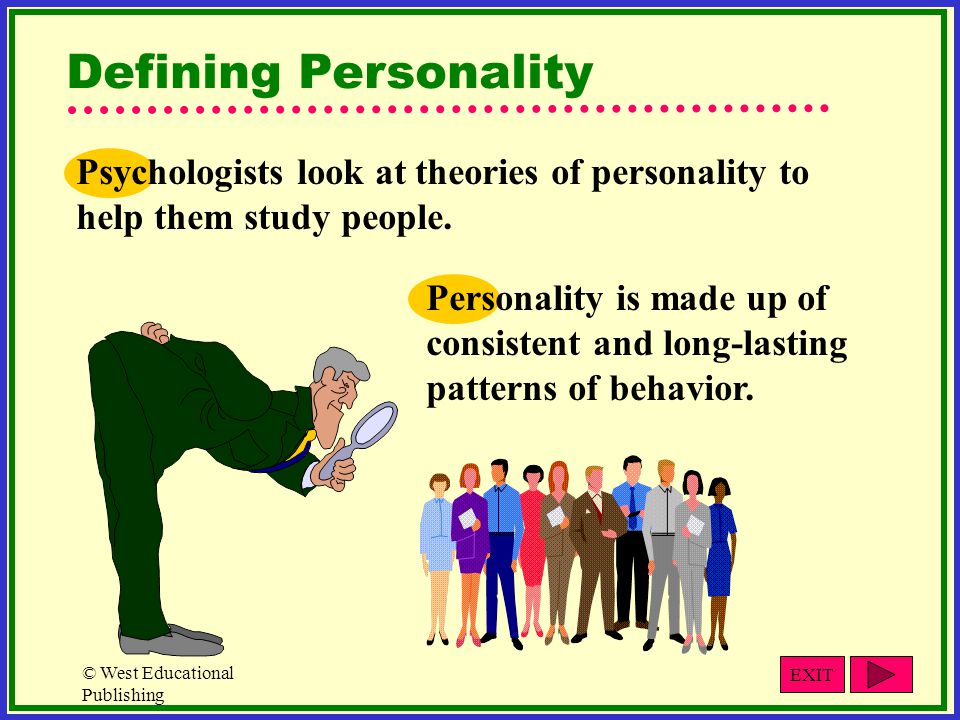

What is friendship from the point of view of psychology All its worldly definitions are metaphors, each of which highlights one aspect of the problem. "Friend - comrade" implies the presence of joint activities and common interests. "Friend is a mirror" emphasizes the function of self-knowledge, and in this case the partner is assigned the passive role of reflection; "Friend-compassionate" personifies emotional empathy. "Friend the interlocutor" highlights the communicative side of friendship, self-disclosure and mutual understanding. "Friend - "alter ego" implies both assimilation, likening another to oneself, and identification, likening oneself to another, self-dissolution in another.

Each of these metaphors is valid in its own way. But do they refer to different types of friendship, or different components of it, or different stages in the development of the same relationship? Real progress in the study of the psychology of friendship begins not with the clarification of definitions, but with the differentiation of questions.

Originated at the end of the 19th century. The psychology of friendship, as well as other human sciences, initially (and up to the middle of the 20th century) posed questions of a general nature: what is the source of friendship, how do its rational and emotional components correlate, and what supports the relationship that once emerged? Researchers of this period collected a lot of empirical material about how different people - mainly children and adolescents - understand friendship and choose friends. But the interpretation of the data for the most part did not go beyond the framework of the ideas of ordinary consciousness and was not linked to any special psychological theories.

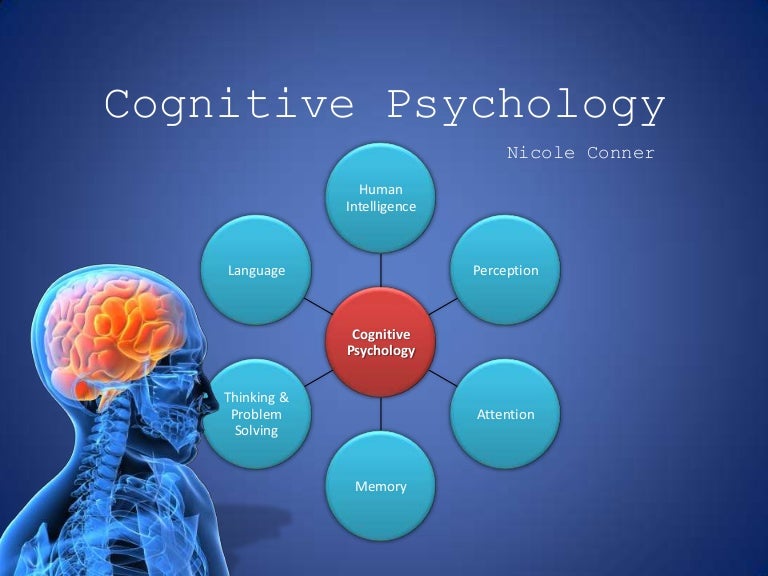

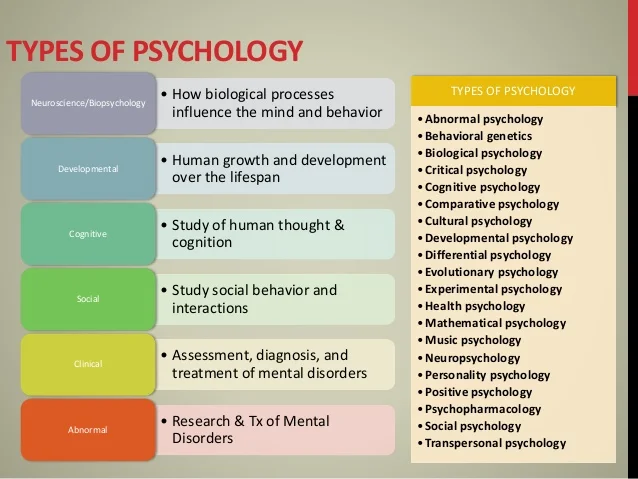

The analytical period in the psychology of friendship, which began in the late 1950s, was associated with socio-psychological studies of interpersonal attraction. The word "attraction" (attraction), like the ancient Greek "philia", literally means attraction, attraction. In social psychology, the concept of "interpersonal attraction" is defined as a cognitive (cognitive) component of an emotional attitude towards another person, or as a certain social attitude, or, finally, as an emotional component of interpersonal perception (social perception).

The main question of the psychology of attraction: "What attracts people to each other?" - content is ambiguous. It also covers the needs of the subject, prompting him to choose one or another partner; and properties of the object (partner) that stimulate interest or sympathy for him; and features of the interaction process that favor the emergence and development of dyadic (pair) relations; and the objective conditions for such interaction (for example, belonging to a common circle of friends). This ambiguity of the problem has led to the thematic diversity of psychological studies of attraction. Of the 403 empirical studies of her published in 1972–1976 in American scientific journals, 147.5 were devoted to the formation of impressions in people about each other, 128.5 to the processes of verbal and behavioral interaction, meetings and contacts, only 127 more or less long friendships (33) or love (94) relationships.

This ambiguity of the problem has led to the thematic diversity of psychological studies of attraction. Of the 403 empirical studies of her published in 1972–1976 in American scientific journals, 147.5 were devoted to the formation of impressions in people about each other, 128.5 to the processes of verbal and behavioral interaction, meetings and contacts, only 127 more or less long friendships (33) or love (94) relationships.

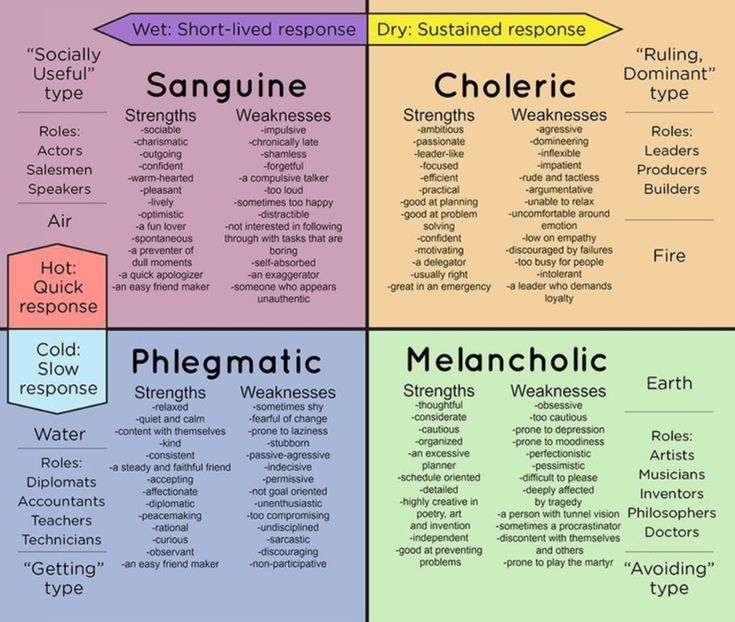

Equally diverse were the theories of attraction themselves. Some of them described mainly its intra-individual, internal prerequisites, others - the mechanisms of communication, the third - the stages of its development, the fourth - the final results. Depending on the initial theoretical and methodological guidelines of the authors, friendship was considered either as a peculiar form of exchange, or as the satisfaction of emotional needs, or as an information process of mutual cognition, or as a social interaction of individuals, or as a unique and unrepeatable dialogue of individuals.

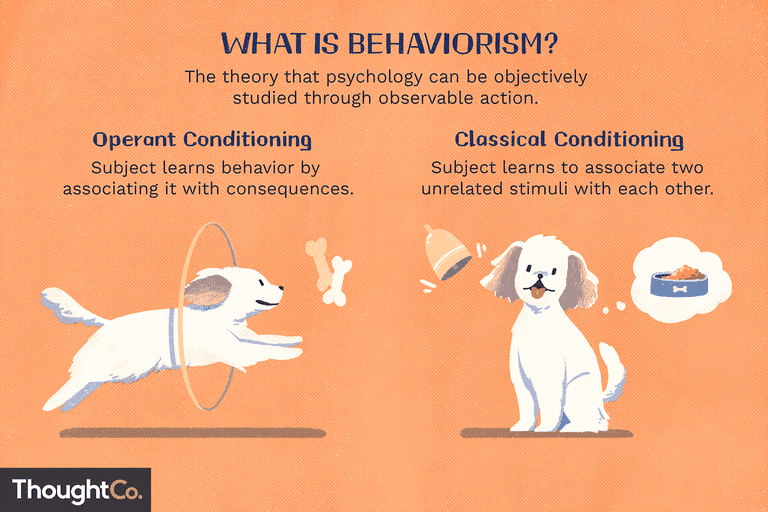

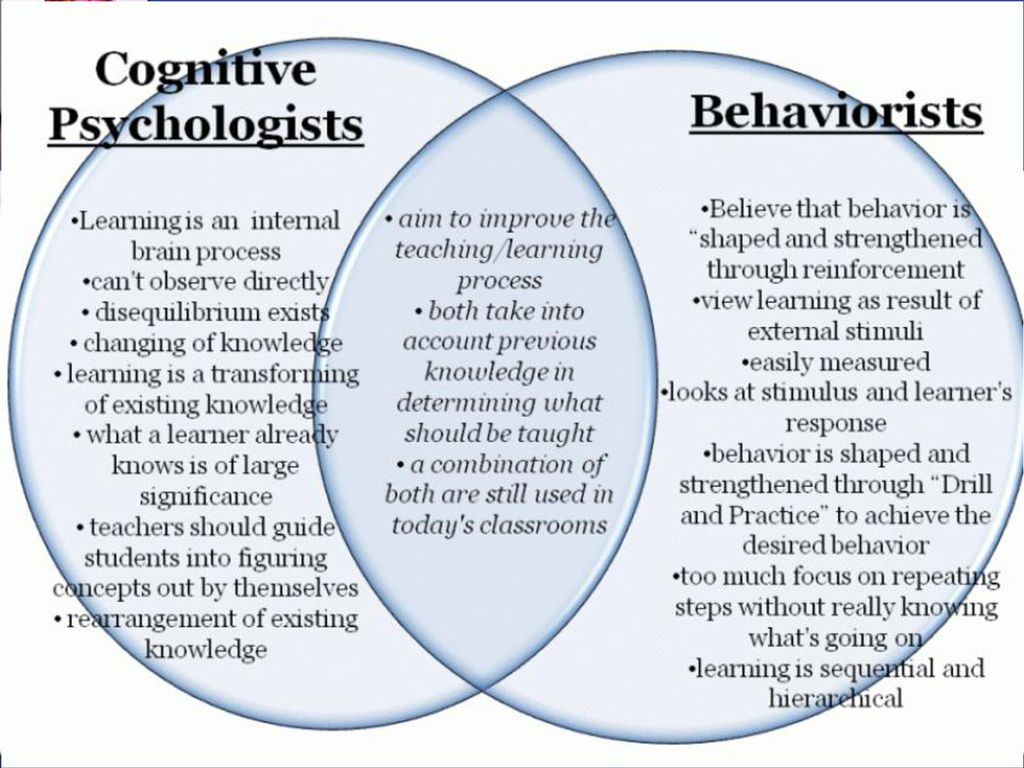

The simplest, behavioral model of attraction, characteristic of neobehaviorism (D. Homans, D. Thiebaud and G. Kelly), considers the exchange of rewards (positive reinforcement) and costs (negative reinforcement) to be the most important condition for any pair interaction. In order for personal relationships to develop and be maintained, according to neobehaviorist theorists, partners must receive maximum rewards and minimum costs from each other and from the interaction process itself. Experiments set up in accordance with this theoretical orientation try to weigh, first of all, the objective consequences, the "outcomes" of the process of friendly interaction: whether the partners manage to receive the desired "reward" in the form of pleasure, "reduction of tension", practical benefit, etc. More complex models, such as J. Clora and D. Byrne, A. and B. Lott, analyze not only "outcomes", but also types of incentives - the ratio of friendship factors such as the similarity of personal traits, the proximity of social attitudes and character. emotional interaction of partners. However, their common methodological basis remains the theory of learning.

emotional interaction of partners. However, their common methodological basis remains the theory of learning.

To explain such a complex phenomenon as friendship, this approach cannot be considered satisfactory - it is too elementary. Its prototype is a business partnership, in which the partner acts as a means of satisfying egoistic needs, a subject, and neither depth, nor intimacy, nor moral obligations to each other are assumed. Yes, and the very "exchange" is considered at the level of individual, isolated needs and desires of the individual, without regard to their place in the life world of a holistic personality. This is a kind of psychological equivalent of the old philosophical theory of "reasonable selfishness".

Although "exchange" - activities, motives, values, etc. - is objectively present in any interpersonal relationship, in more flexible theories of friendship it figures as a private, subordinate element.

Psychodynamic theory, represented, in particular, by psychoanalysis, sees the origins of friendship, like all other attachments, in the unconscious emotional needs of the individual. The founder of psychoanalysis, Z. Freud, believed that all human inclinations and attachments, be it friendship, parental love or devotion to an idea, are ultimately of an instinctive nature, being forms of sexual desire, libido, which he, however, defined very broadly.

The founder of psychoanalysis, Z. Freud, believed that all human inclinations and attachments, be it friendship, parental love or devotion to an idea, are ultimately of an instinctive nature, being forms of sexual desire, libido, which he, however, defined very broadly.

The authors of later psychoanalytic theories of motivation, developed within the framework of neo-Freudian concepts, recognize the existence. a person has special interpersonal, communicative needs. For example, the American psychologist W. Schutz, the author of the "fundamental orientation of interpersonal relations" model, claims that a person has a certain ratio of three interpersonal needs: belonging, (affiliation), control and love. The level of each of these needs is laid in early childhood, predetermining the future communicative properties and real communication of an adult. The decisive role of "significant, others" in the formation of personality is emphasized by the founder of the "interpersonal theory of psychiatry" X. S. Sullivan.

S. Sullivan.

In general, the psychodynamic theory of attraction is better suited to describe unaccountable and uncontrollable attachments than to freely created friendships. In psychoanalytic concepts, a friend is most often assigned the role of a mirror onto which the subject projects his own unconscious traits, or an ideal role model for identification. In addition, this concept tends to absolutize the "traumatic" consequences of negative childhood experiences, leaving the processes and mechanisms of adult interpersonal relations in the shade.

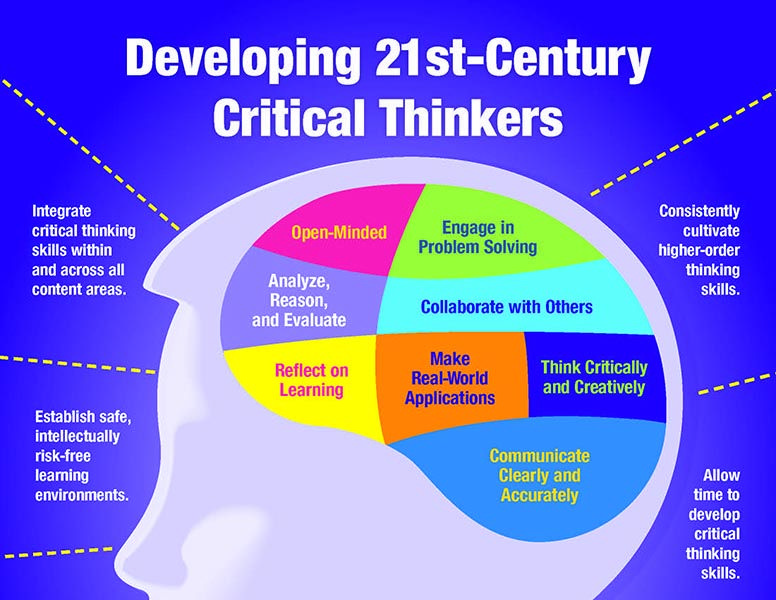

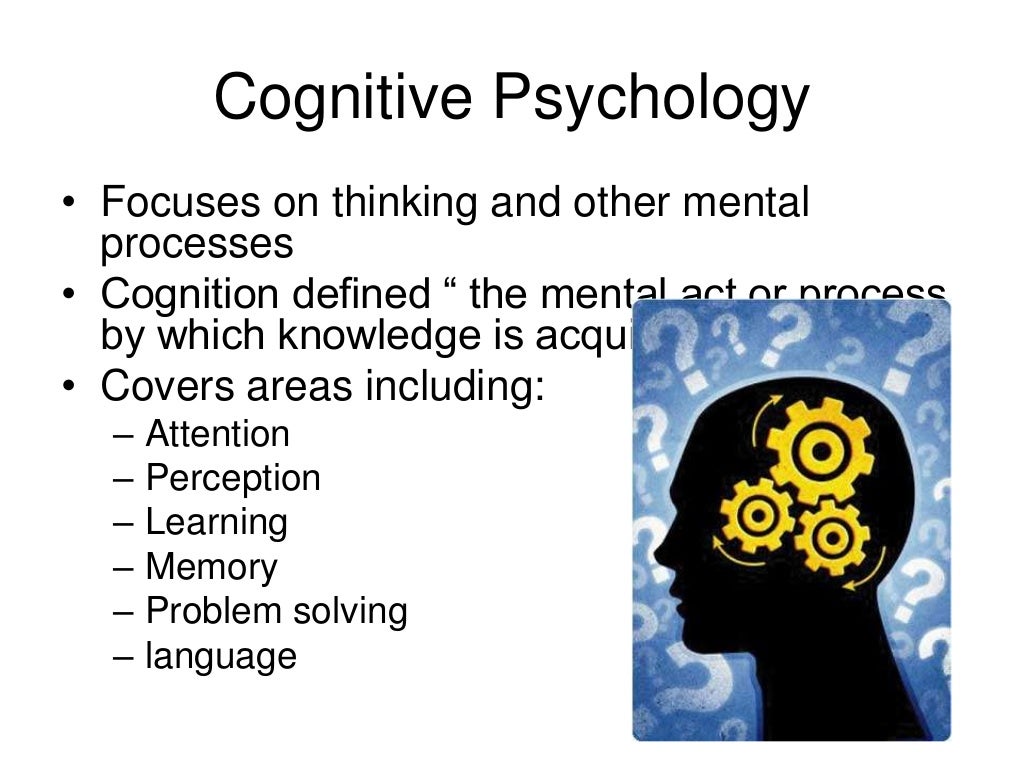

If the behavioral approach captures the "molecular" processes of interpersonal interaction, and the psychodynamic approach captures intrapersonal needs, then cognitive psychology analyzes the informational and procedural side of communication, trying to answer the question of how exactly interpersonal communication occurs. Representatives of this trend (F. Haider, T. Newcomb, E. Walster, Z. Rubin, etc.) primarily explore the cognitive and symbolic aspects of human relationships: social attitudes, value orientations, signs, meanings, etc.

In contrast to the "naive" psychology, which tried to deduce attraction, attraction of certain people to each other directly from their objective similarities or differences, cognitive psychology emphasizes the importance of attribution (attribution) processes.

According to its theorists, what is important in friendship is not so much the actual coincidence or mismatch of individual traits as their perception, what qualities friends attribute to one another and what is the tendency of such attribution (we tend to see only good things in friends, and only bad things in enemies ). The "reinforcement exchange", which neobehaviorists interpret naively-mechanistically, in the light of the cognitive "theory of justice" appears to be a more complex psychological process: the desire to get maximum satisfaction from communication is usually measured by the individual with his ideas about a fair exchange, and this prompts him to take care not only about his own benefit, but also about the interests of the partner.

Cognitive psychology initiated the systematic study of the "language of friendship" - terms in which people comprehend and describe their relationships and ideas about each other, as well as "personal constructs" (D. Kelly, S. Duck, etc.) - specific oppositions , opposite concepts used by the subject to categorize themselves or other people. These concepts form his implicit (tacitly implied) theory of personality. For example, the categorization of others along the axis "people of the goal" - "people of emotions" reflects the individual's idea of antagonism, purposefulness and emotionality and is apparently determined by the specifics of his personal life experience. Knowledge of the "repertory positions" of an individual, the structure of social roles that are significant for him and their subjective meaning allows the psychologist to look into his inner world and his intimate environment. Of great importance for the psychology of friendship is also interpersonal competence - the development by an individual of the necessary communication skills, the ability to make acquaintances, open up and understand others.

Symbolic interactionism (D. Mead, D. McCall, etc.) highlights the socio-structural (role) and cultural-symbolic (meaning) aspects of personal relationships in connection with the development of self-awareness. Since a personality is formed and realizes itself only in interaction with other people, adherents of this direction see the goal of studying friendship in deciphering the psychological content of this process - understanding why a given Self is attached to a given Other. Interpersonal attraction, as defined by McCall, differs from formal or business relationships in that it contains the Self, desiring, "on the basis of its positive attachment to the Other, to establish a personal mutually active relationship with him.

Interactionists operate with such categories as. acceptance of the role of another, role behavior, definition of the situation and I. Acceptance of a role involves the ability to put oneself in the place of another person, imagining the requirements of his social position, his feelings and the meaning that this role and behavior has for him. Playing a role implies mastering a system of rules, the observance of which determines the effectiveness and appropriateness of appropriate actions, gestures, etc., and determining the situation means coordinating one’s own intentions and goals with the intentions and goals of other participants in the interaction. This is possible only if you have a stable system of self-esteem and at the same time the ability to look at yourself through the eyes of others. Such an approach makes sense in relation to the description of such phenomena as the development of interpersonal competence, the dependence of an individual's personal relations on his position and popularity in a group, the relationship of friendship with the level of development of self-awareness.

Playing a role implies mastering a system of rules, the observance of which determines the effectiveness and appropriateness of appropriate actions, gestures, etc., and determining the situation means coordinating one’s own intentions and goals with the intentions and goals of other participants in the interaction. This is possible only if you have a stable system of self-esteem and at the same time the ability to look at yourself through the eyes of others. Such an approach makes sense in relation to the description of such phenomena as the development of interpersonal competence, the dependence of an individual's personal relations on his position and popularity in a group, the relationship of friendship with the level of development of self-awareness.

Although all of the listed approaches to understanding the psychological aspects of interpersonal interaction are different in their initial assumptions, and in some ways even opposite, at the same time they are complementary, each of them has a certain rational grain. Any single act of interpersonal interaction and this whole process as a whole can be considered both as a behavioral process of rapprochement and correlation of two subjects independent of each other, and as the knowledge of one subject by another, and as the satisfaction of some internal emotional need of the subject, and as a process of symbolic interaction, during which individuals do not just exchange information, but assimilate each other's points of view and life prospects, thereby expanding the boundaries of their own selves.

Any single act of interpersonal interaction and this whole process as a whole can be considered both as a behavioral process of rapprochement and correlation of two subjects independent of each other, and as the knowledge of one subject by another, and as the satisfaction of some internal emotional need of the subject, and as a process of symbolic interaction, during which individuals do not just exchange information, but assimilate each other's points of view and life prospects, thereby expanding the boundaries of their own selves.

At the same time, a more complex theoretical model potentially includes elementary ones as its aspects or special cases. Thus, the model of communication as the interaction of self-conscious I and You includes the processes of their mutual cognition (since self-consciousness involves self-knowledge, and the assimilation of the life perspective of another is impossible without understanding his role and position) and the satisfaction of emotional needs (since the “I-image” also covers emotional-evaluative components ). The cognitive model, in turn, assumes the existence of elementary processes of exchange and reinforcement, described by the behaviorist scheme, etc.

The cognitive model, in turn, assumes the existence of elementary processes of exchange and reinforcement, described by the behaviorist scheme, etc.

However, despite some interesting partial results, the most important and unexpected conclusion of the psychology of attraction turned out to be the proof of the absence of factors rigidly determining the level of attraction. Its causes are valid only in a certain range of conditions and in combination with other variables. Being objectively determined, human communication, including such a form as friendship, is determined at the same time by the will of its participants, their desire, what style of behavior they choose, and other unpredictable features that depend only on them.

In the early 1980s, it became clear to psychologists that the study of individual attitudes and needs makes it difficult to discern the integrity of a person's life world, and the reduction of personal relationships to a series of "interactions" obscures their deep personal meaning. Laboratory methods are more suitable for analyzing static, non-evolving one-time encounters with strangers than natural, life relationships. In laboratory studies, it is almost impossible to take into account the development of personal relationships over time, as well as the active efforts and needs of their participants. Friendly relations and their "levels" were conceived not as living, dynamic, changeable processes that have a subjective meaning, but as stable "states".

Laboratory methods are more suitable for analyzing static, non-evolving one-time encounters with strangers than natural, life relationships. In laboratory studies, it is almost impossible to take into account the development of personal relationships over time, as well as the active efforts and needs of their participants. Friendly relations and their "levels" were conceived not as living, dynamic, changeable processes that have a subjective meaning, but as stable "states".

A new scientific and theoretical paradigm that replaced the theory of interpersonal attraction considers friendship as a special kind of personal relationship. What are its features?

1. The range of phenomena covered by the concept of "personal relations" is much narrower and more definite than the phenomena of "interpersonal attraction". This is not about casual short-term contacts, but only about relatively stable, developing relationships.

2. Unlike functional-role relations, personal relations are individual, personalized, in the course of their formation and development a new subjective, personal meaning is formed that enriches both participants, which does not happen with a simple information or behavioral exchange.

3. Personal relationships must be studied in the natural environment, taking into account the time factor, and not only in the ascending (acquaintance, deepening, maintenance), but also in the descending (deterioration, weakening, breaking of relations) stages of development.

4. Since we are talking about subject-subject relations, their development does not develop automatically, in accordance with universal norms, but depends on the conscious efforts and communicative strategy of partners.

5. Behind the illusion of a stable state and a smooth transition from one stage of a relationship to another lies a dramatic process of change, uncertainty, negotiations, attributions, etc.

6. The meaning and meaning of these processes are often not realized, and their consequences are interpreted differently by the participants in the relationship. Therefore, it is important to distinguish between their objective determination, subjective motivation and retrospective legitimation (explanation and justification).

The psychology of personal relationships as a special area of scientific research for the first time received a specific design and consolidation in the five-volume work of the same name, created with the participation of Soviet psychologists and published under the editorship of S. Duck and R. Gilmour. In addition, from 1984 a special interdisciplinary journal "Journal of Social and Personal Relationships" was published under the editorship of the same Duck, and in 1985 the International Society for the Study of Personal Relations was organized.

In philosophical and methodological terms, the approaches of this trend are close, on the one hand, to the ideas of "humanistic psychology" developed in the West, and on the other hand, to the "dialogical" understanding of communication developed on the basis of the ideas of M. M. Bakhtin, L. S. Vygotsky and A. A. Ukhtomsky by Soviet philosophers V. S. Bibler and M. S. Kagan, psychologists A. N. Leontiev, A. V. and V. A. Petrovsky, culturologists L. M. Batkin, Yu. Lotman, etc. Is it possible, however, to translate such a complex problem into the mainstream of empirical scientific research and what do we actually know about the objective prerequisites of friendship, its implied rules, stages of development and psychological mechanisms?

M. Batkin, Yu. Lotman, etc. Is it possible, however, to translate such a complex problem into the mainstream of empirical scientific research and what do we actually know about the objective prerequisites of friendship, its implied rules, stages of development and psychological mechanisms?

As for the objective prerequisites, like all other personal relationships, friendship largely depends on the system of social ties, the circle of direct communication of the individual, due to territorial proximity, social group affiliation - and joint activities. However, the psychological significance of these factors is not the same.

The American social psychologist T. Newcomb, as an experiment, settled first-year students of the University of Michigan into rooms in different combinations according to the principle of similarity or dissimilarity of attitudes, and then studied the dynamics of their relationship. It turned out that in the early stages of acquaintance, attraction depends more on spatial proximity than on the similarity of attitudes, but later on the situation changes and the similarity of attitudes outweighs the influence of proximity.

The influence of spatial proximity on personal relationships in most cases is mediated and supplemented by other factors mentioned by group membership and joint activities associated with a certain division of functions, cooperation and mutual assistance. Like ordinary consciousness, scientific psychology distinguishes between business, functional relationships and personal, individual attachments, as well as partnership due to belonging to the same team and friendship based on individual choice and personal sympathy.

Business relations, or as some Soviet scientists call them after A.S. in them as a performer of a certain social function, role. Belonging to this collective and the feeling of solidarity with its other members (partnership) arising from it does not necessarily imply personal sympathy for each of them individually, without which friendship is unthinkable. “The question of the relationship of comrade to comrade,” wrote Makarenko, “is not a question of friendship, not a question of love, not a question of neighborhood, but this is a question of responsible dependence. ”

”

However, the difference between friendship and fellowship is relative. Close cooperation and mutual assistance in joint activities easily and imperceptibly grow into mutual sympathy. The team is united not only by the common interest of its members in the results of their joint activities, but also by a sense of group solidarity, belonging to the whole. The degree of emotional identification of individuals with the group is one of the main indicators of team cohesion. And identification with the team is impossible without mutual support and care for individual comrades. "Feeling of comradeship" is the most important common component of camaraderie and friendship. Therefore, companionship is not just a background, but a living breeding ground for the emergence and development of individualized friendship.

It is not for nothing that people acquire most of their friends precisely in the process of joint activities, in their production or educational teams, and the importance of this type of community far outweighs the role of territorial and domestic factors. This is evidenced, in particular, by the data of the already mentioned studies of L. A. Gordon and E. V. Klopov.

This is evidenced, in particular, by the data of the already mentioned studies of L. A. Gordon and E. V. Klopov.

The importance of joint activity and collective affiliation for the emergence of friendship is also proved by socio-psychological experiments. Known, for example, the experiment of the American social psychologist M. Sheriff.

A group of 11-12-year-old boys, taken from different schools and who had never met each other before, were taken to a country camp. For three days, teenagers had the opportunity to communicate completely freely with each other, they developed some kind of attachment, groups, gaming companies, etc. After certain personal relationships were established between the guys, a sociometric test was conducted, during which everyone named their best friends. Then the guys were divided into two teams so that two-thirds of the best friends of each were on the opposite team. Each team received its own task, communication between members of different teams was minimized, and the teams themselves were placed in a relationship of competition and rivalry. A few days later, the boys were again asked to name their best friends, emphasizing that they could choose not only from their own team, but also from another. This time the choice was completely different. Team membership decisively outweighed initial personal sympathies: the number of "best friends" from one's own team was 95%, in another - 88%.

A few days later, the boys were again asked to name their best friends, emphasizing that they could choose not only from their own team, but also from another. This time the choice was completely different. Team membership decisively outweighed initial personal sympathies: the number of "best friends" from one's own team was 95%, in another - 88%.

Experiment shows that individual preference completely determines the choice of friends where there are no established collectives and groups. But if an individual is already part of a group that has its own goals, a certain distribution of roles, etc., this also leaves an imprint on his personal preferences. As a rule, he chooses friends from among those people with whom he communicates more often in daily activities and with whom he is connected by a sense of group solidarity.

Of course, real life is more complicated than the experimental situation. Each person simultaneously belongs not to one, but to several different groups (industrial, socio-political, family) and has a number of reference groups with which he conforms his behavior. Meanwhile, the number of close friends is limited. Hence the problem of individual choice, from which, in fact, the psychology of friendship begins, in contrast to the psychology of collective activity or the psychology of communication.

Meanwhile, the number of close friends is limited. Hence the problem of individual choice, from which, in fact, the psychology of friendship begins, in contrast to the psychology of collective activity or the psychology of communication.

Like all solid human relationships, friendship is governed by a certain system of rules. The code of ancient institutionalized friendship was, as we have seen, quite explicit. Today, the rules of friendship are mostly tacitly implied. Nevertheless, their observance is very important for maintaining and appreciating the depth of friendships. What are these rules?

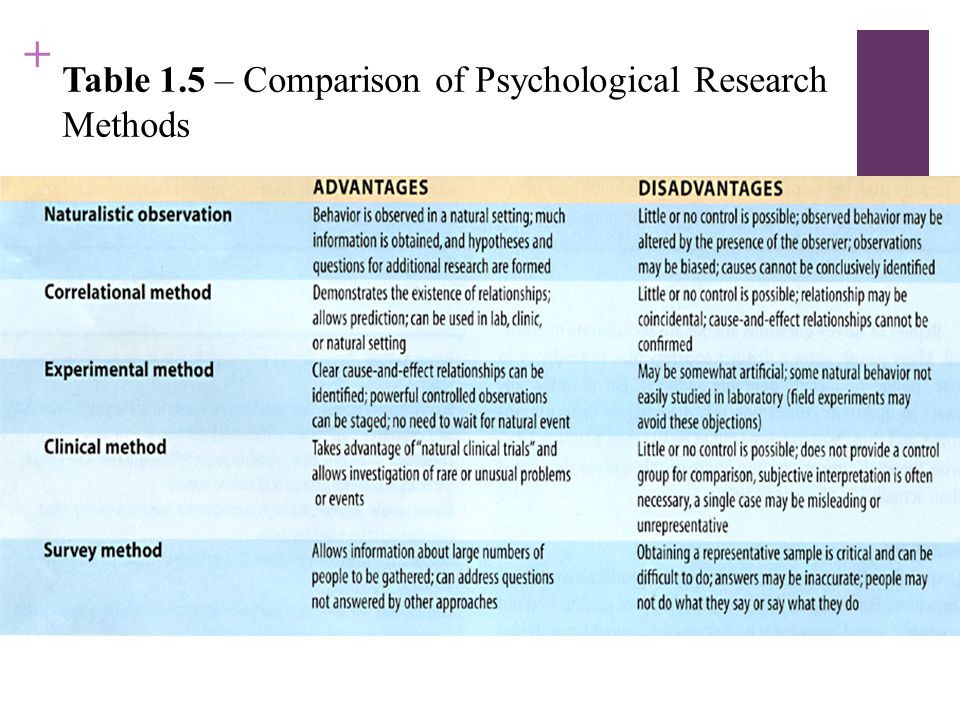

English psychologists M. Lharple and M. Henderson, through a series of surveys, established which of the 43 supposed general rules of behavior are considered the most important for friendship among the British, Italians, Japanese and Hong Kong residents (men and women aged 18 to 25 and from 30 up to age 60). Then, according to the criteria of compliance with or violation of these rules, the students compared successful, ongoing friendships with broken ones, as well as friendships that are highly or poorly rated by their participants. And finally, we checked which rules, if violated, most often lead to the breakup of friendship or are perceived as the reason for its termination.

And finally, we checked which rules, if violated, most often lead to the breakup of friendship or are perceived as the reason for its termination.

The researchers proceeded from the following hypotheses.

Like all other relationships, friendship involves a set of informal rules. These rules allow friends. maintain a certain level of this or that positive reinforcement, as well as avoid jealousy of third parties.

There are rules to ensure privacy and respect for the individuality of the other.

For all their cultural differences, different cultures have a similar informal code of friendship.

The rules of mutual reward distinguish between close and less intimate friendships.

The female friendship rules place more emphasis on self-disclosure and emotional support than the male friendship rules.

Help and spending time together are more important in the friendship of young people than in the friendship of older people.

When friendships break, people are more likely to attribute rule violations to others than to themselves.

When breaking friendships, breaking rules that provide positive reinforcement is mentioned less frequently than breaking rules that govern conflict situations, such as betrayal of trust or invasion of privacy.

Violation of certain rules is perceived as a natural cause for the termination of friendship; for example, failure to observe the norms of trust and mutual respect leads to a deterioration in relations, and violation of the rules that prevent conflicts, such as the prohibition to intrude into the partner’s inner world, leads to a break.

In general, the hypotheses were confirmed. Of the 27 general rules of friendship formulated on the basis of the first stage of the study, 13 turned out to be the most important, which were divided into four groups: exchange, intimacy, attitude towards third parties, mutual coordination.

Unwritten friendship rules:

Exchange

to share news about your successes

To show emotional support

,to help voluntarily, if you need

,, try so that it is pleasant to your friend in your company

,to return the debts and rendered services

Intimacy

Confidence in the other and trust in him

Attitude towards third parties

Protecting a friend in his absence

Be tolerant of other friends *

Do not criticize a friend in public **

Keep confidential secrets **

Do not be jealous or criticize other personal relationships of another **

Coordination

*

Respect the friend's inner peace and autonomy **

The six unstarred rules seem to be the most important, as they meet all four criteria: unanimously recognized as important for friendship; distinguish ongoing friendships from broken ones and highly valued relationships from low valued ones; non-compliance with these rules is considered a probable and valid reason for ending the friendship.

Rules marked with one asterisk meet three criteria, but do not distinguish close friends from less intimate ones. In other words, they are important for normal levels of friendship, but in especially close relationships they can be violated: close friends are not considered favors, they forgive intolerance towards mutual acquaintances and even some importunity.

Rules marked with two asterisks meet two criteria: they are considered important and their violation may contribute to the termination of friendship, but the assessment of the depth of friendship does not depend on them. These rules—avoid public criticism, keep a trusted secret, not be jealous of third parties, and respect the other's private world—are not specific to friendship and apply to many other personal relationships and situations.

The study of the unwritten code of friendship is of great theoretical and practical importance. It is obvious that friendship presupposes the observance of all the basic rules of human coexistence, which also operate in less close communal, collective and personal relationships. However, the correlation, significance and hierarchy of these rules are not the same. As friendship deepens and individualizes, the elementary general norms of "exchange" lose some of their meaning, giving way to more complex and subtle rules of intimacy.

However, the correlation, significance and hierarchy of these rules are not the same. As friendship deepens and individualizes, the elementary general norms of "exchange" lose some of their meaning, giving way to more complex and subtle rules of intimacy.

For all the differences between modern friendships and ancient institutionalized friendship, the concept of friendship is intrinsically characterized by the idea of exclusivity, extraordinaryness, which allows for the possibility of violating and exceeding some more elementary, generally accepted norms and rules.

Friends are allowed a lot of things that would inevitably complicate and even spoil relations with less close people - neighbors, workmates, etc. psychological requirements. And since the most important specific rules of friendship - to share one's experiences, provide moral support, voluntarily help in case of need, take care of a friend, trust him and be confident in him, protect a friend in his absence - are altruistic, their acceptance and observance implies a fairly high level moral consciousness of the individual, as well as the maturity of the most friendly relationship. It can be put differently: social psychology confirms that friendship is a moral relationship and it cannot be otherwise.