Prevent psychopathic behavior

Possible Interventions for Preventing the Development of Psychopathic Traits among Children and Adolescents?

1. Offord D.R., Boyle M.H., Racine Y.A. The epidemiology of antisocial behavior in childhood and adolescence. Dev. Treat. Child. Aggress. 1991;17:31–54. [Google Scholar]

2. Frick P.J., Ray J.V., Thornton L.C., Kahn R.E. Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychol. Bull. 2014;140:1–57. doi: 10.1037/a0033076. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Waller R., Hyde L.W. Callous-unemotional behaviors in early childhood: The development of empathy and prosociality gone awry. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018;20:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.037. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. DeLisi M. Psychopathy as Unified Theory of Crime. Palgrave Macmillan; New York, NY, USA: 2016. Why Psychopathy as Unified Theory of Crime? pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

5. Seagrave D., Grisso T. Adolescent development and the measurement of juvenile psychopathy. Law Hum. Behav. 2002;26:219–239. doi: 10.1023/A:1014696110850. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Ogden T. Sosial Kompetanse og Problematferd Blant Barn og Unge. Gyldendal Akademisk; Oslo, Norway: 2015. [Google Scholar]

7. McCart M.R., Sheidow A.J. Evidence-Based Psychosocial Treatments for Adolescents with Disruptive Behavior. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2016;45:529–563. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1146990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Dadds M.R., Cauchi A.J., Wimalaweera S., Hawes D.J., Brennan J. Outcomes, moderators, and mediators of empathic-emotion recognition training for complex conduct problems in childhood. Psychiatry Res. 2012;199:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.04.033. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Moffitt T.E. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychol. Rev. 1993;100:674. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Psychol. Rev. 1993;100:674. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Moffitt T.E. Male antisocial behaviour in adolescence and beyond. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018;2:177–186. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0309-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Moffitt T.E., Caspi A. Childhood predictors differentiate life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Dev. Psychopathol. 2001;13:355–375. doi: 10.1017/S0954579401002097. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. APA . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

13. Fairchild G., Van Goozen S.H.M., Calder A.J., Goodyer I.M. Research Review: Evaluating and reformulating the developmental taxonomic theory of antisocial behaviour. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2013;54:924–940. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Piquero A.R., Farrington D.P., Fontaine N.M.G., Vincent G., Coid J., Ullrich S. Childhood risk, offending trajectories, and psychopathy at age 48 years in the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Psychol. Public Policy Law. 2012;18:577–598. doi: 10.1037/a0027061. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Piquero A.R., Farrington D.P., Fontaine N.M.G., Vincent G., Coid J., Ullrich S. Childhood risk, offending trajectories, and psychopathy at age 48 years in the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Psychol. Public Policy Law. 2012;18:577–598. doi: 10.1037/a0027061. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Fox B.H., Jennings W.G., Farrington D.P. Bringing psychopathy into developmental and life-course criminology theories and research. J. Crim. Justice. 2015;43:274–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2015.06.003. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Corrado R.R., DeLisi M., Hart S.D., McCuish E.C. Can the causal mechanisms underlying chronic, serious, and violent offending trajectories be elucidated using the psychopathy construct? J. Crim. Justice. 2015;43:251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2015.04.006. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Frick P.J., White S.F. Research Review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2008;49:359–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01862.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry. 2008;49:359–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01862.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Rowe R., Maughan B., Moran P., Ford T., Briskman J., Goodman R. The role of callous and unemotional traits in the diagnosis of conduct disorder. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2010;51:688–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02199.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Frick P.J., Stickle T.R., Dandreaux D.M., Farrell J.M., Kimonis E. Callous–Unemotional Traits in Predicting the Severity and Stability of Conduct Problems and Delinquency. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2005;33:471–487. doi: 10.1007/s10648-005-5728-9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Pardini D.A., Lochman J.E., Frick P. Callous/Unemotional Traits and Social-Cognitive Processes in Adjudicated Youths. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2003;42:364–371. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00018. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Kimonis E.R., Frick P.J., Munoz L.C., Aucoin K.J. Callous-unemotional traits and the emotional processing of distress cues in detained boys: Testing the moderating role of aggression, exposure to community violence, and histories of abuse. Dev. Psychopathol. 2008;20:569–589. doi: 10.1017/S095457940800028X. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Dev. Psychopathol. 2008;20:569–589. doi: 10.1017/S095457940800028X. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Pardini D.A., Loeber R. Interpersonal and Affective Features of Psychopathy in Children and Adolescents: Advancing a Developmental Perspective Introduction to Special Section. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2007;36:269–275. doi: 10.1080/15374410701441575. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Lynam D.R., Caspi A., Moffitt T.E., Loeber R., Stouthamer-Loeber M. Longitudinal evidence that psychopathy scores in early adolescence predict adult psychopathy. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2007;116:155–165. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Essau C.A., Sasagawa S., Frick P.J. Callous-unemotional traits in a communitysample of adolescents. Assessment. 2006;13:454–469. doi: 10.1177/1073191106287354. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Eisenberg N., Fabes R.A. Empathy: Conceptualization, measurement, and relation to prosocial behavior. Motiv. Emot. 1990;14:131–149. doi: 10.1007/BF00991640. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Motiv. Emot. 1990;14:131–149. doi: 10.1007/BF00991640. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Vaish A., Carpenter M., Tomasello M. Young Children Selectively Avoid Helping People with Harmful Intentions. Child Dev. 2010;81:1661–1669. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01500.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Talwar V., Lee K. Development of lying to conceal a transgression: Children’s control of expressive behaviour during verbal deception. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2002;26:436–444. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000373. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Ronald A., Happé F., Hughes C., Plomin R. Nice and Nasty Theory of Mind in Preschool Children: Nature and Nurture. Soc. Dev. 2005;14:664–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00323.x. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Patterson G.R. Coercive Family Process. Castalia Publishing Company; Eugene, OR, USA: 1982. A social learning approach, Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

30. Dargis M., Li J.J. The Interplay between Positive and Negative Parenting and Children’s Negative Affect on Callous-Unemotional Traits. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020;29:2614–2622. doi: 10.1007/s10826-020-01783-5. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020;29:2614–2622. doi: 10.1007/s10826-020-01783-5. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Waller R., Gardner F., Hyde L.W. What are the associations between parenting, callous–unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013;33:593–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.001. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Pardini D.A., Lochman J.E., Powell N. The development of callous-unemotional traits and antisocial behavior in children: Are there shared and/or unique predictors? J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2007;36:319–333. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444215. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Hawes D.J., Dadds M.R., Frost A.D., Hasking P.A. Do childhood callous-unemotional traits drive change in parenting practices? J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2011;40:507–518. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.581624. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Dishion T.J., Patterson G.R. The development and ecology of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In: Cicchetti D., Cohen D.J., editors. Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. Wiley; New York, NY, USA: 2006. pp. 503–541. [Google Scholar]

In: Cicchetti D., Cohen D.J., editors. Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. Wiley; New York, NY, USA: 2006. pp. 503–541. [Google Scholar]

35. Pasalich D.S., Dadds M.R., Hawes D.J., Brennan J. Do callous-unemotionaltraits moderate the relative importance of parental coercion versus warmth in child conduct problems? An observational study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2011;52:1308–1315. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02435.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Muñoz L.C., Pakalniskiene V., Frick P.J. Parental monitoring and youth behavior problems: Moderation by callous-unemotional traits over time. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2011;20:261. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0172-6. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Barker E.D., Oliver B.R., Viding E., Salekin R.T., Maughan B. The impact of prenatal maternal risk, fearless tem-perament and early parenting on adolescent callous-unemotional traits: A 14-year longitudinal investigation. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2011;52:878–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02397.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry. 2011;52:878–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02397.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Waller R., Gardner F., Hyde L.W., Shaw D.S., Dishion T.J., Wilson M.N. Do harsh and positive parenting predict parent reports of deceitful-callous behavior in early childhood? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2012;53:946–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02550.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Kroneman L.M., Hipwell A.E., Loeber R., Koot H.M., Pardini D.A. Contextual risk factors as predictors of disruptive behavior disorder trajectories in girls: The moderating effect of callous-unemotional features. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2011;52:167–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02300.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Muratori P., Lochman J.E., Lai E., Milone A., Nocentini A., Pisano S., Masi G. Which dimension of parenting predicts the change of callous unemotional traits in children with disruptive behavior disorder? Compr. Psychiatry. 2016;69:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.06.002. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry. 2016;69:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.06.002. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. O’Connor T.G., Humayun S., Briskman J.A., Scott S. Sensitivity to parenting in adolescents with callous/unemotional traits: Observational and experimental findings. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2016;125:502–513. doi: 10.1037/abn0000155. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Kauten R.L., Lui J.H., Doucette H., Barry C.T. Perceived family conflict moderates the relations of adolescent narcissism and cu traits with aggression. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015;24:2914–2922. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-0095-1. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

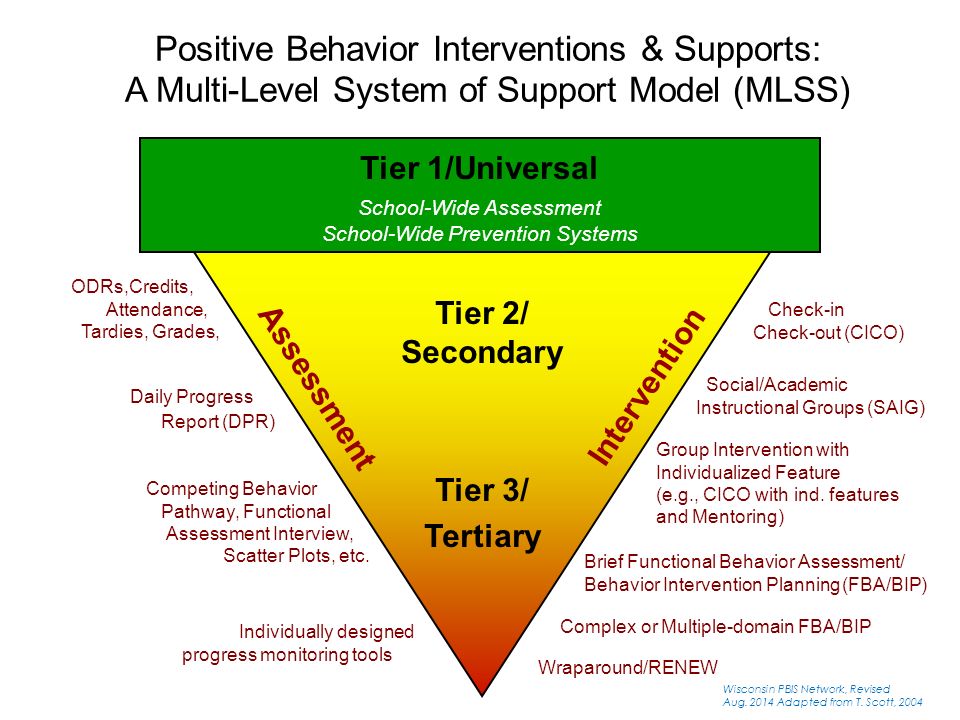

43. Weisz J.R., Ng M.Y., Lau N. Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. John Wiley & Sons Limited; Oxford, UK: 2015. Psychological interventions: Overview and critical issues for the field; pp. 461–482. [Google Scholar]

44. Hawes D.J., Dadds M.R. The Treatment of Conduct Problems in Children with Callous-Unemotional Traits. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005;73:737–741. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.737. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Psychol. 2005;73:737–741. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.737. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Hawes D.J., Dadds M. Stability and Malleability of Callous-Unemotional Traits during Treatment for Childhood Conduct Problems. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2007;36:347–355. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444298. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Dishion T.J., Stormshak E.A. Intervening in Children’s Lives: An Ecological, Family-Centered Approach to Mental Health Care. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC, USA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

47. Hyde L.W., Shaw D.S., Gardner F., Cheong J., Dishion T.J., Wilson M. Dimensions of callousness in early childhood: Links to problem behavior and family intervention effectiveness. Dev. Psychopathol. 2013;25:347–363. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412001101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Kimonis E.R., Fleming G., Briggs N., Brouwer-French L., Frick P.J., Hawes D.J., Bagner D.M., Thomas R., Dadds M. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy Adapted for Preschoolers with Callous-Unemotional Traits: An Open Trial Pilot Study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019;48:S347–S361. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1479966. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy Adapted for Preschoolers with Callous-Unemotional Traits: An Open Trial Pilot Study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019;48:S347–S361. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1479966. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Neuman K.J., Bagner D.M. Treatment of Early Childhood Callous-Unemotional Traits: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go from Here? J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2021;60:1348–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2021.05.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. McDonald R., Dodson M.C., Rosenfield D., Jouriles E.N. Effects of a parenting intervention on features of psychopathy in children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2011;39:1013–1023. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9512-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Somech L.Y., Elizur Y. Promoting Self-Regulation and Cooperation in Pre-Kindergarten Children with Conduct Problems: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2012;51:412–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac. 2012.01.019. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2012.01.019. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Kjøbli J., Zachrisson H.D., Bjørnebekk G. Three Randomized Effectiveness Trials—One Question: Can Callous-Unemotional Traits in Children Be Altered? J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2018;47:436–443. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1178123. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Kjøbli J., Bjørnebekk G. A Randomized Effectiveness Trial of Brief Parent Training: Six-Month Follow-Up. Res. Soc. Work. Pr. 2013;23:603–612. doi: 10.1177/1049731513492860. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. Kjøbli J., Hukkelberg S., Ogden T. A randomized trial of group parent training: Reducing child conduct problems in real-world settings. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013;51:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.11.006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

55. Kjøbli J., Ogden T. A randomized effectiveness trial of individual child social skills training: Six-month follow-up. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health. 2014;8:31. doi: 10.1186/s13034-014-0031-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. Baglivio M.T., Jackowski K., Greenwald M.A., Wolff K.T. Comparison of multisystemic therapy and functional family therapy effectiveness: A multiyear statewide propensity score matching analysis of juvenile offenders. Crim. Justice Behav. 2014;41:1033–1056. doi: 10.1177/0093854814543272. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Henggeler S.W. Multisystemic therapy: An overview of clinical procedures, outcomes, and policy implications. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Rev. 1999;4:2–10. doi: 10.1017/S1360641798001786. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

58. Henggeler S.W., Schoenwald S.K., Borduin C.M., Rowland M.D., Cunningham P.B. Multisystemic Therapy for Antisocial Behavior in Children and Adolescents. Guilford Press; New York, NY, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

59. Mihalic S.F., Elliott D.S. Evidence-based programs registry: Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development. Eval. Program Plan. 2015;48:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan. 2014.08.004. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2014.08.004. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

60. van der Stouwe T., Asscher J.J., Stams G.J.J., Deković M., van der Laan P. The effectiveness of Multisystemic Therapy (MST): A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014;34:468–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

61. Butler S., Baruch G., Hickey N., Fonagy P. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Multisystemic Therapy and a Statutory Therapeutic Intervention for Young Offenders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2011;50:1220–1235.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.017. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Manders W.A., Deković M., Asscher J.J., van der Laan P., Prins P.J.M. Psychopathy as Predictor and Moderator of Multisystemic Therapy Outcomes among Adolescents Treated for Antisocial Behavior. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013;41:1121–1132. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9749-5. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Alexander J.F., Waldron H.B., Robbins M.S., Neeb A.A. Functional Family Therapy for Adolescent Behavior Problems. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

American Psychological Association; Washington, DC, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

64. Hartnett D., Carr A., Hamilton E., Reilly G.O. The Effectiveness of Functional Family Therapy for Adolescent Behavioral and Substance Misuse Problems: A Meta-Analysis. Fam. Process. 2017;56:607–619. doi: 10.1111/famp.12256. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

65. Robbins M.S., Alexander J.F. Functional Behaviour in Family Adolescents Therapy for Antisocial. In: Allen J.L., Hawes D.J., Essau C.A., editors. Family-Based Intervention for Child and Adolescent Mental Health: A Core Competencies Approach. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2021. pp. 152–165. [Google Scholar]

66. White S.F., Frick P.J., Lawing K., Bauer D. Callous-unemotional traits and response to functional family therapy in adolescent offenders. Behav. Sci. Law. 2012;31:271–285. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2041. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

67. Thøgersen D.M., Bjørnebekk G., Scavenius C., Elmose M. Callous-Unemotional Traits Do Not Predict Functional Family Therapy Outcomes for Adolescents with Behavior Problems. Front. Psychol. 2021;11:3976. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.537706. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Front. Psychol. 2021;11:3976. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.537706. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

68. Mattos L.A., Schmidt A.T., Henderson C.E., Hogue A. Therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in the outpatient treatment of urban adolescents: The role of callous–unemotional traits. Psychotherapy. 2017;54:136–147. doi: 10.1037/pst0000093. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

69. Frick P.J., Viding E. Antisocial behavior from a developmental psychopathology perspective. Dev. Psychopathol. 2009;21:1111–1131. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990071. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

70. Da Silva D.R., Rijo D., Castilho P., Gilbert P. The Efficacy of a Compassion-Focused Therapy–Based Intervention in Reducing Psychopathic Traits and Disruptive Behavior: A Clinical Case Study with a Juvenile Detainee. Clin. Case Stud. 2019;18:323–343. doi: 10.1177/1534650119849491. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

71. da Silva D.R., Rijo D., Salekin R.T. , Paulo M., Miguel R., Gilbert P. Clinical change in psychopathic traits after the PSYCHOPATHY.COMP program: Preliminary findings of a controlled trial with male detained youth. J. Exp. Criminol. 2020;17:397–421. doi: 10.1007/s11292-020-09418-x. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Paulo M., Miguel R., Gilbert P. Clinical change in psychopathic traits after the PSYCHOPATHY.COMP program: Preliminary findings of a controlled trial with male detained youth. J. Exp. Criminol. 2020;17:397–421. doi: 10.1007/s11292-020-09418-x. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

72. Wilkinson S., Waller R., Viding E. Practitioner Review: Involving young people with callous unemotional traits in treatment—Does it work? A systematic review. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2016;57:552–565. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12494. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

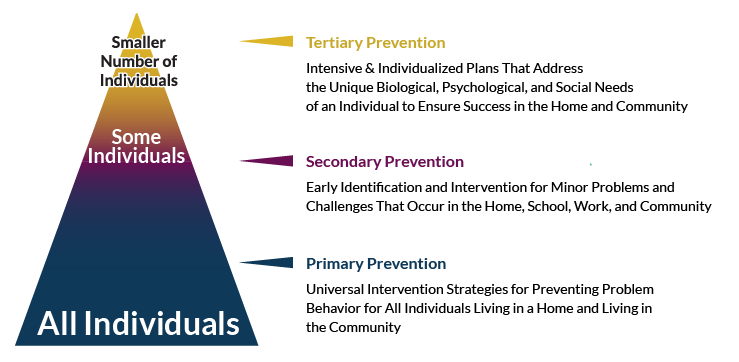

The Science of Preventing Dangerous Psychopathy

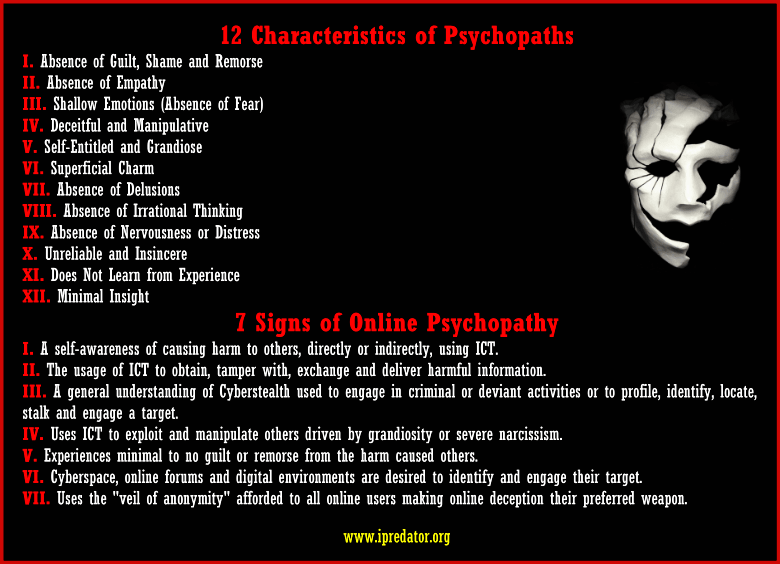

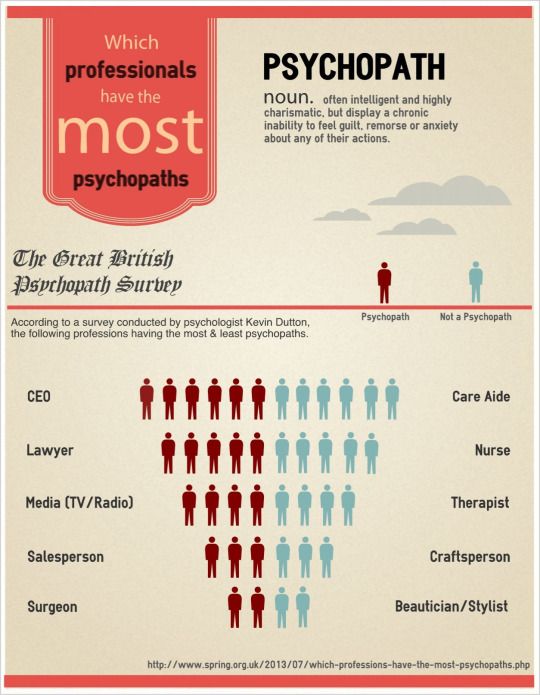

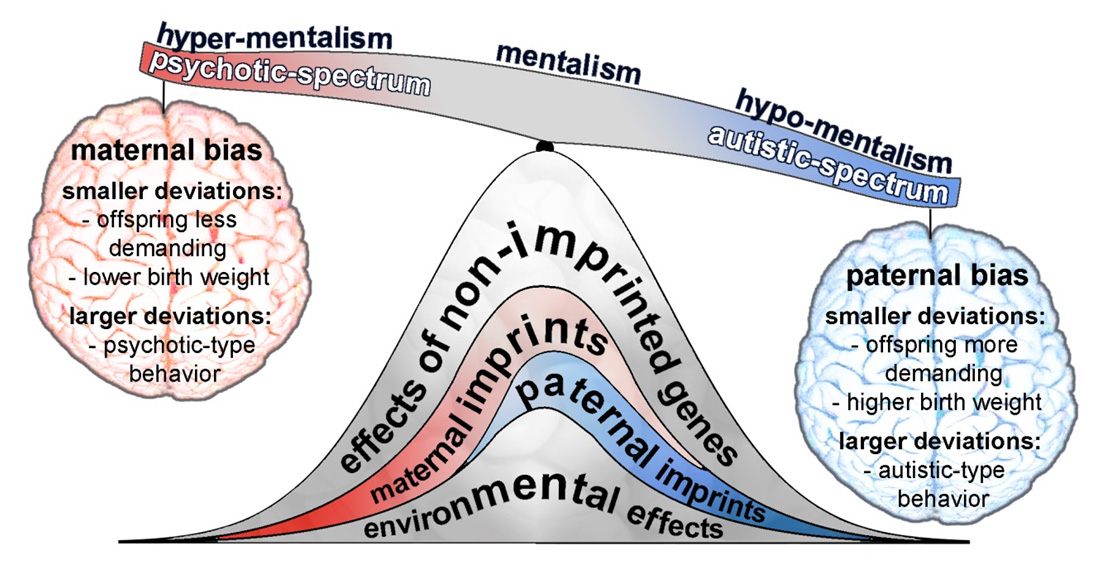

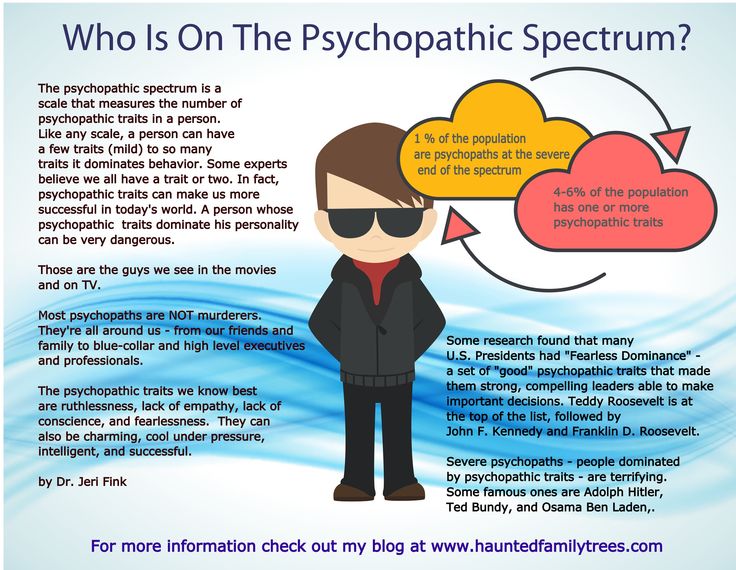

What makes someone a psychopath? Nature or nurture? And can we stop at risk children from growing up into dangerous adult psychopaths? One of the oldest queries in psychology — nature versus nurture — asks if what makes us who we are is predisposed by our DNA, or by life experiences. It is a pretty poignant question when it comes to psychopaths, who are estimated to account for up to 50% of all serious crimes in the US.

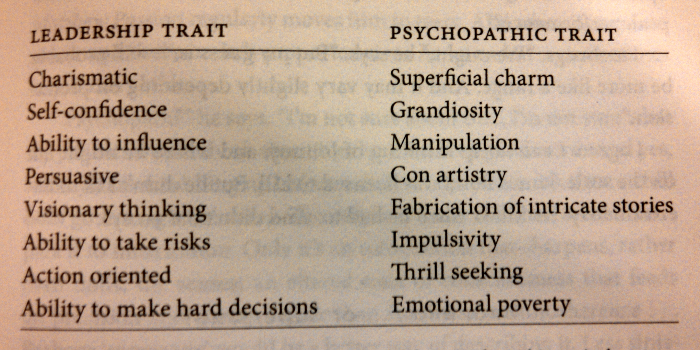

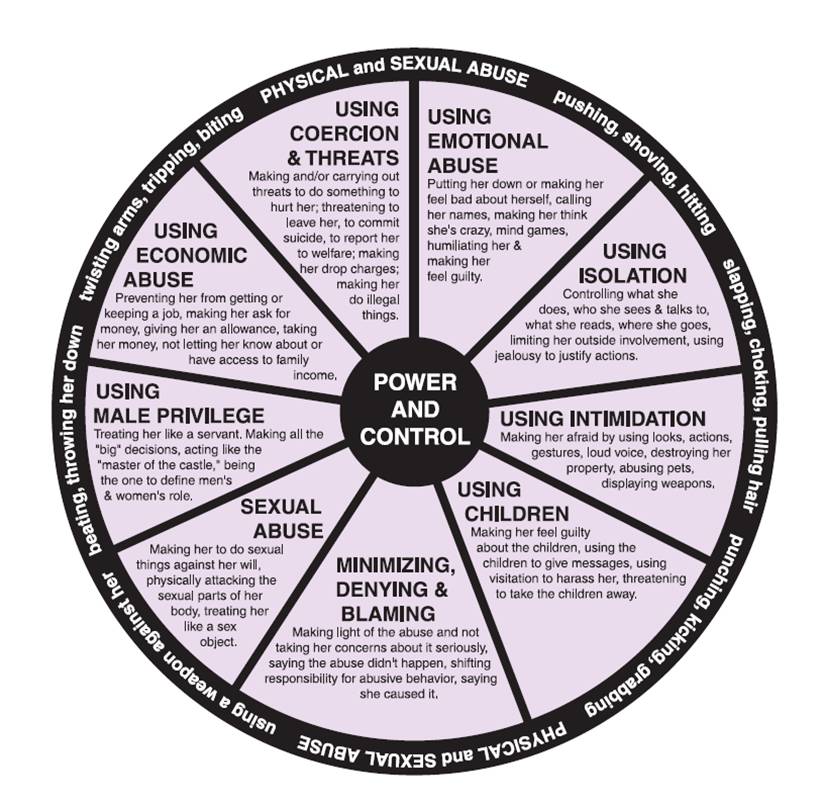

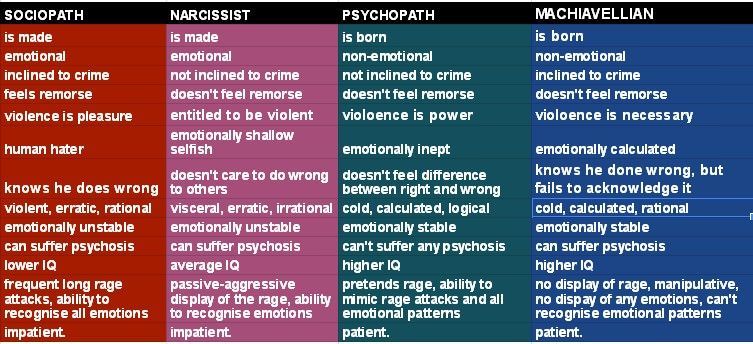

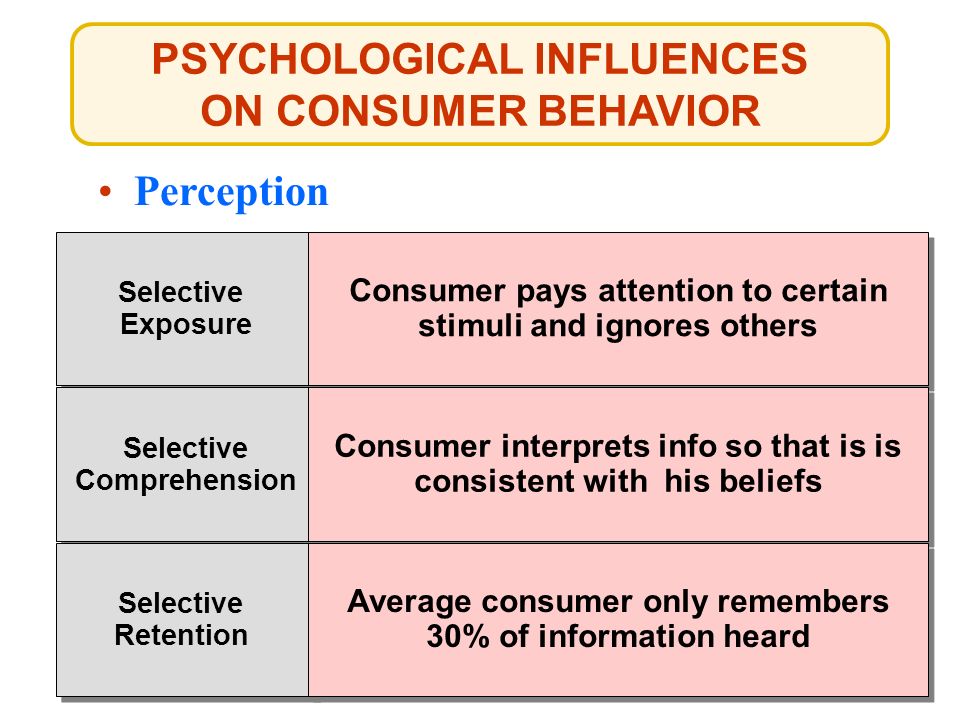

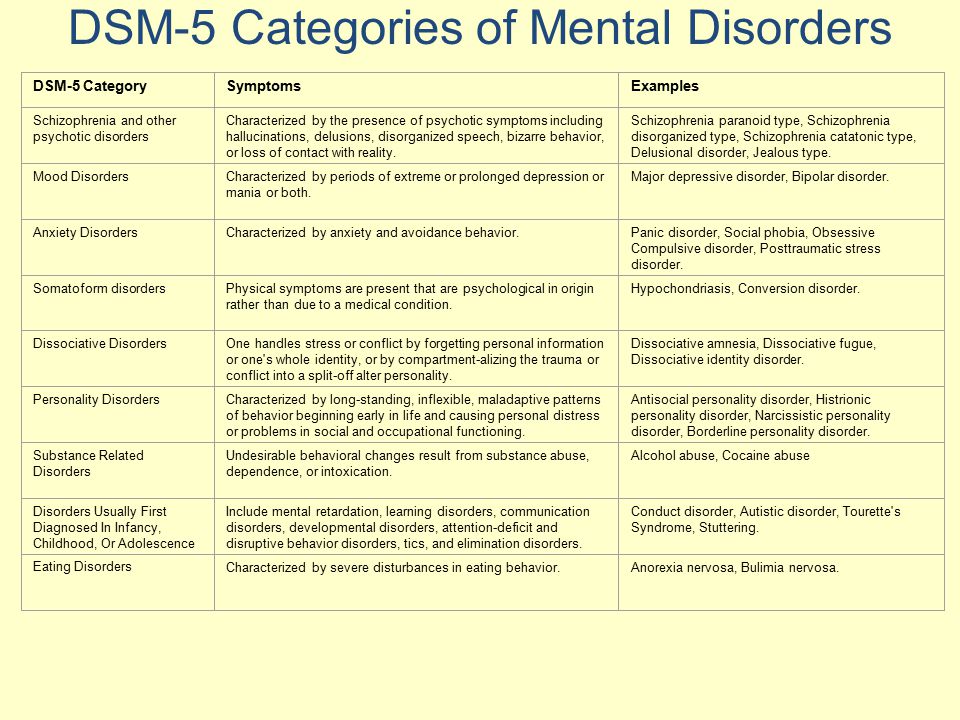

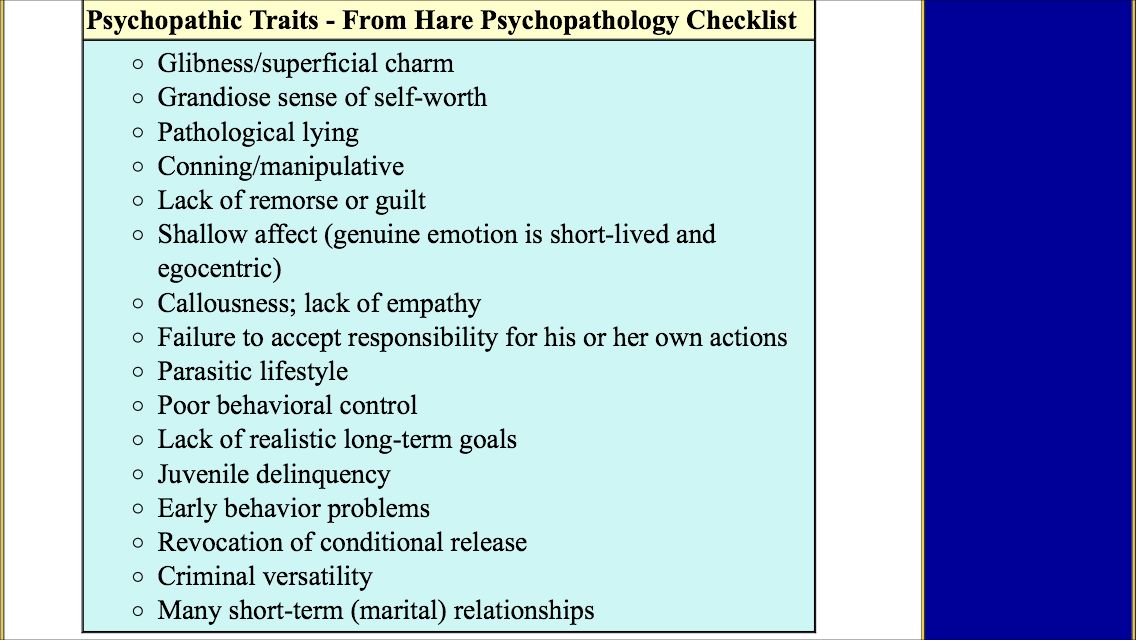

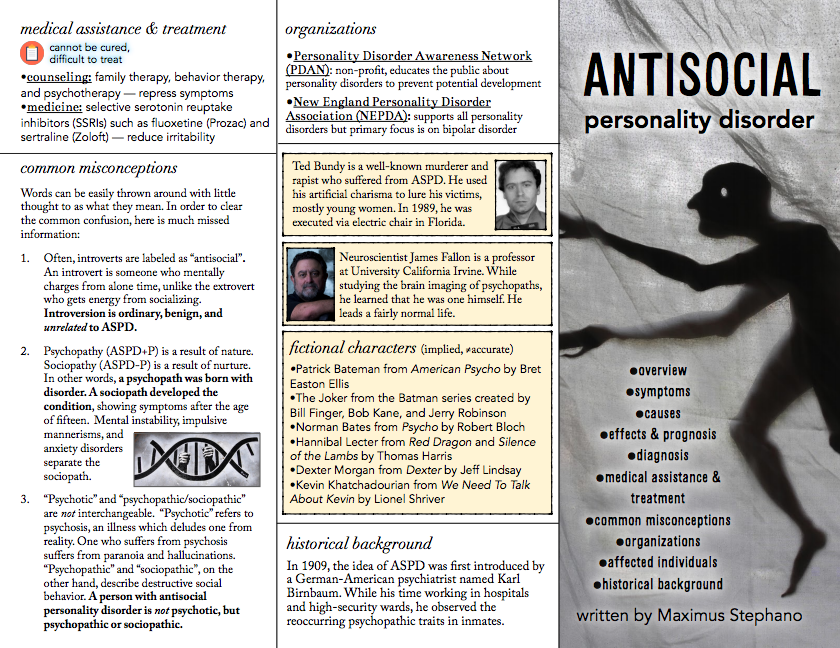

Clinically known as anti-social personality disorder in the DMS-V, some troublesome psychopathic traits include:

- An egocentric identity

- Absence of pro-social standards in goal-setting

- Lack of empathy

- Incapacity for mutually intimate relationships

- Manipulativeness

- Deceitfulness

- Callousness

- Irresponsibility, impulsivity and risk taking

- Hostility

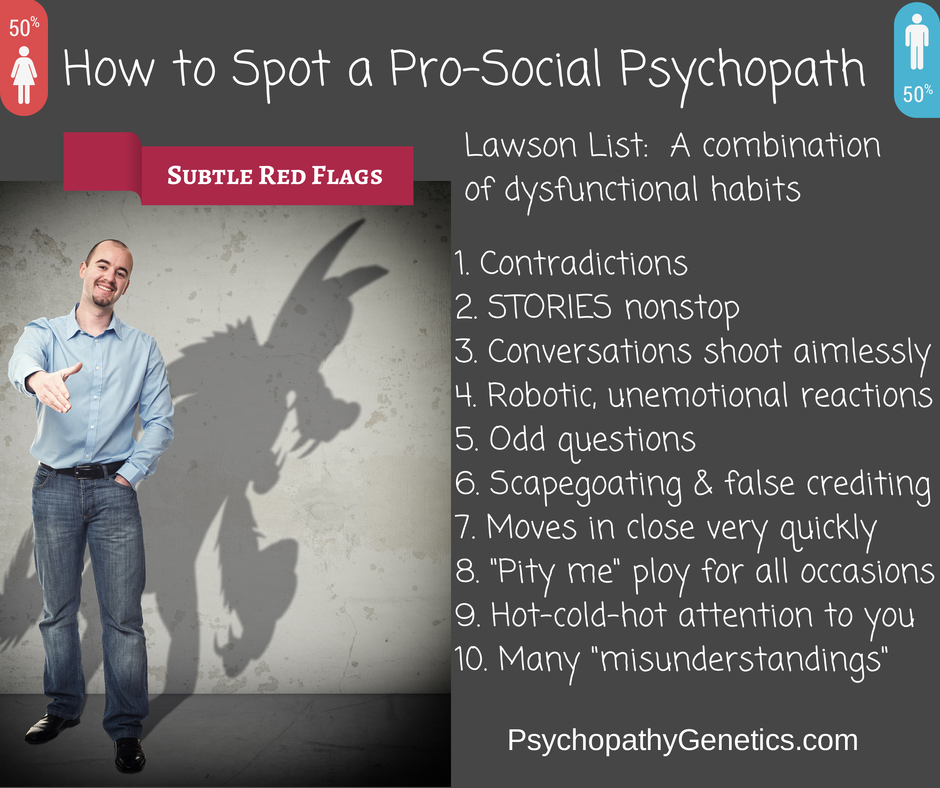

Although these characteristics may be unpleasant, not all psychopaths are dangerous or criminals, and not all dangerous criminals are psychopaths. Counter-intuitively there are pro-social psychopaths too. Nonetheless, some psychopaths do pose a genuine threat for the safety of others.

The real unsolved problem when it comes to psychopathy is how to treat the personality disorder. Although certainly not to be considered impossible with the malleable brains we have even as adults, Dr. Nigel Blackwood, a leading Forensic Psychiatrist at King’s College London, has stated that adult psychopaths can be treated or managed, but not cured. Curing adult psychopathy is considered a near-impossible challenge.

Curing adult psychopathy is considered a near-impossible challenge.

Therefore, understanding when and how psychopathy develops from child to adult is an important part of the research engine that will hopefully identify what parents, caregivers and governments can do to prevent an at risk child from growing up to be a dangerous psychopath.

Development of Psychopathic Personalities Is Mainly Due to Genes

Enter new psychopathy research published in Development and Psychopathology by lead author Dr. Catherine Tuvblad from the University of Southern California. Her research was a twin-based study designed to overcome many previous drawbacks and limitations. Ultimately, the study was designed to provide a more reliable indication of the extent to which genes or the environment, that is nature or nurture, is responsible for the development of psychopathic personality features as a child grows into a young adult.

In the study, 780 pairs of twins and their caregivers filled out a questionnaire that allowed for measuring features of child psychopathy at ages 9–10, 11–13, 14–15, and 16–18. This included measuring psychopathic personality features indicative of future psychopathy, such as high levels of callous behavior towards peers and problems adhering to social norms.

This included measuring psychopathic personality features indicative of future psychopathy, such as high levels of callous behavior towards peers and problems adhering to social norms.

The changes in the children’s psychopathic personality features between age groups was considered to be:

- 94% due to genetics between the ages of 9-10 and 11-13, and 6% environmental.

- 71% due to genetics between the ages of 11–13 and 14–15, and 29% environmental.

- 66% due to genetics between 14-15 and 16-18<, and 34% environmental. ((This suggests that environmental factors may gradually play a greater part in changing the levels of psychopathic features a child develops in later teenage years, which is very promising for the development of future interventions for the prevention of psychopathy. It should be noted that while the children’s test results pointed to the environment around them becoming increasingly important to their psychopathic behavior, their parents almost exclusively thought that the psychopathy they observed in their children was purely genetic.

Considering parents are largely responsible for their child’s environment, its not that surprising. Nurture is important at key developmental stages in psychopathy development.))

Considering parents are largely responsible for their child’s environment, its not that surprising. Nurture is important at key developmental stages in psychopathy development.))

The analysis also revealed that there may be a key turning point in the development of psychopathy during the age range studied. The authors considered this turning point to be caused by the onset of puberty, when gene-environment interactions that are highly significant in inhibiting or promoting the development of psychopathy are at play.

Interestingly, the data also indicates that if these rapid gene-environment based changes in psychopathic traits occur early on (e.g. 11-13), any later additional environmental changes to psychopathic traits would be minimal. In other words, once the psychopathic personality traits are set during puberty, they tend to last into later years.

Other research has found that there may be other key turning points on route to becoming a psychopath much earlier in life. One study found that the total number of early negative life events between the ages of 0-4 were positively correlated with the emotion-based aspects of psychopathy. The findings suggest that early environmental factors could have important implications for the development of psychopathic traits and may also impact attachment to parents for children with genetic potential for psychopathy.

One study found that the total number of early negative life events between the ages of 0-4 were positively correlated with the emotion-based aspects of psychopathy. The findings suggest that early environmental factors could have important implications for the development of psychopathic traits and may also impact attachment to parents for children with genetic potential for psychopathy.

So although psychopathy is largely genetic, where it’s mostly down to if you have the right combination of genes needed to become a psychopath or not, life experiences during puberty and early infant years could make or break a potential psychopath.

Is The Cure for Psychopathy Love?

So what does science suggest as a successful environmental antidote to developing psychopathy? Believe it or not, love!

One neuroscientist, Dr. James Fallon, made a shocking discovery that on paper he is a psychopath. For example, he had a version of the monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) gene that is linked with violent crime and psychopathy. Also known as the warrior gene, MAOA encodes an enzyme that affects the neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin.

Also known as the warrior gene, MAOA encodes an enzyme that affects the neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin.

His brain scans also resembled those of a psychopath. He had low activity in certain areas of the frontal and temporal lobes linked challenges with empathy, morality and self-control. In his family tree, there were also seven alleged murderers.

Although Dr. Fallon, in his own words, is obnoxiously competitive, kind of an asshole and won’t even let his grandchildren win games, he was certainly not a dangerous psychopath. So why not? His genes and even his brain screamed potential for antisocial psychopathy.

His answer was that the love he received from his mother led to him becoming a pro-social psychopath. And a newly published study tends to agree with him. OK love in itself is not enough. But, how a mother expresses that love in guiding the child’s pro-social behavior and in setting good examples of pro-social behavior might be the real key.

A new discovery coming from research on adopted infants suggests this is the case. Researchers found that the development of one of the largest child risk factors for psychopathy, that is highly heritable from biological mothers with severe antisocial behaviors — callous-unemotional behavior — was inhibited by high levels of positive reinforcement at 18 months by the adopted mother.

Further research will hopefully identify a whole repertoire of ways parents, schools and governments alike can lovingly nurture the development of at risk children through these key developmental stages. Ultimately, this could stop a large amount of future violent criminals literally in their diapers, before they even start.

Methods for the treatment of psychopathology, schizophrenia, psychopathy diseases in a hospital in Zelenograd

- Narcology

- Library

- Psychopathy disease: what is it and how is it treated?

What is this disease - "psychopathy"? Does it need to be treated and where to turn for help?

Psychopathy or personality disorder, according to leading psychiatrists, is not a disease. This is a feature of personality and character that makes a person's behavior difficult and leads to problems when building relationships with other people. The main signs of psychopathy are social maladaptation, stability and totality of manifestations. But if psychopathy is not a disease, should it be treated? The answer is unequivocal: yes, because without treatment a person will not be able to lead a full-fledged lifestyle and will always be practically out of society. Treatment of psychopathologies in Zelenograd is one of the services of our medical center, "AXON 24". You can contact our specialists on all issues related to mental disorders and their treatment! nine0012

Although psychopathy is not a disease in the truest sense of the word, it definitely requires correction, because without therapy it can lead to the most negative consequences. Psychopaths quite often become alcoholics and drug addicts, and this fact is confirmed by official medical statistics. People with personality disorders do not understand how the mechanisms of the surrounding reality work, they are afraid of being rejected by societies, they are excessively impulsive and incapable of analyzing even elementary events. All this together pushes a person to consume alcohol or drugs; with the help of intoxicating substances, the patient runs away from society and from himself. nine0011 Psychopaths are prone to suicidal thoughts and often try to turn these destructive ideas into reality. They are driven to this by fear of the outside world, society. And in suicide, psychopaths sometimes begin to see the solution to all their problems. If a psychopath is dominated by emotional disturbances, he can commit crimes associated with sadism and extreme cruelty.

Psychopaths quite often become alcoholics and drug addicts, and this fact is confirmed by official medical statistics. People with personality disorders do not understand how the mechanisms of the surrounding reality work, they are afraid of being rejected by societies, they are excessively impulsive and incapable of analyzing even elementary events. All this together pushes a person to consume alcohol or drugs; with the help of intoxicating substances, the patient runs away from society and from himself. nine0011 Psychopaths are prone to suicidal thoughts and often try to turn these destructive ideas into reality. They are driven to this by fear of the outside world, society. And in suicide, psychopaths sometimes begin to see the solution to all their problems. If a psychopath is dominated by emotional disturbances, he can commit crimes associated with sadism and extreme cruelty.

Timely seeking medical help and behavior modification by psychotherapists, psychologists and psychiatrists helps to prevent such negative consequences. Effective methods of psychopathology therapy are used in our medical center, "AXON 24". Our hospital treats schizophrenia, psychopathy, borderline disorder, and other mental disorders, including alcohol and drug use disorders. nine0012

Effective methods of psychopathology therapy are used in our medical center, "AXON 24". Our hospital treats schizophrenia, psychopathy, borderline disorder, and other mental disorders, including alcohol and drug use disorders. nine0012

How is psychopathy treated?

Psychopathy requires combination therapy. During the period of active manifestation of emotional instability, the patient is prescribed medications that level the emotional background, restore peace of mind. Drug therapy is supplemented with psychotherapy sessions that help a person adapt to society, eliminate self-doubt, and reveal hidden potential that can be used in a useful way.

You can get a detailed consultation on the treatment of psychopathologies by making an appointment at our medical center, "AXON 24". nine0012

About the author:

Kozin V.A.

psychiatrist-narcologist of the highest category,

Ph.D. chief physician of MC AKSON 24

December 30 at 13:45

enter the short code from the SMS message to confirm the phone number: +7 (999) 999-9999

Invalid verification code

CALL NOW!

get a free consultation

Moscow

+7 495 565-35-03

Zelenograd

+7 495 649-41-03

How does a psychopath work? 8 phases through which victims of office predators go

Elena Isupova

Psychopaths are nearby and may be working with you. They are difficult to recognize: they pretend to be confident professionals, acquire patrons and thrive in a corporate environment. To avoid manipulation, it is important to learn as much as possible about the mode of action of office predators. The book "Snakes in Suits" tells us what to expect. nine0012

They are difficult to recognize: they pretend to be confident professionals, acquire patrons and thrive in a corporate environment. To avoid manipulation, it is important to learn as much as possible about the mode of action of office predators. The book "Snakes in Suits" tells us what to expect. nine0012

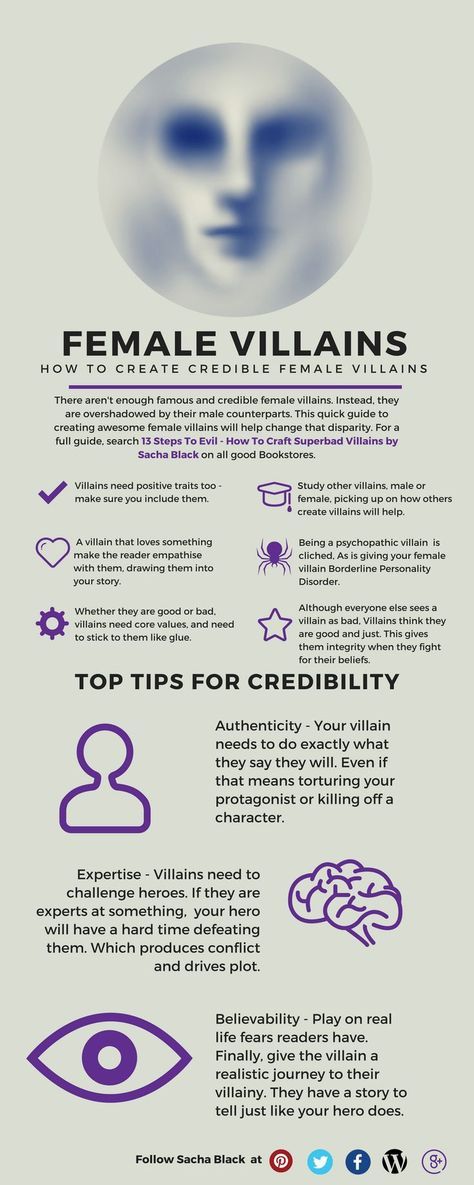

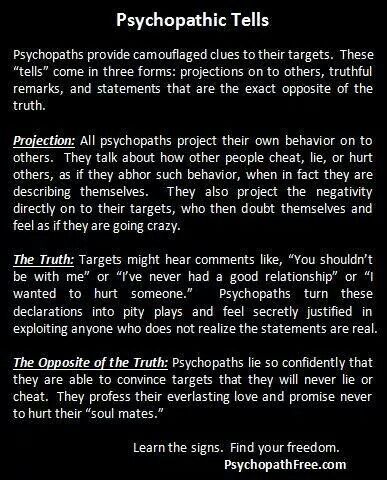

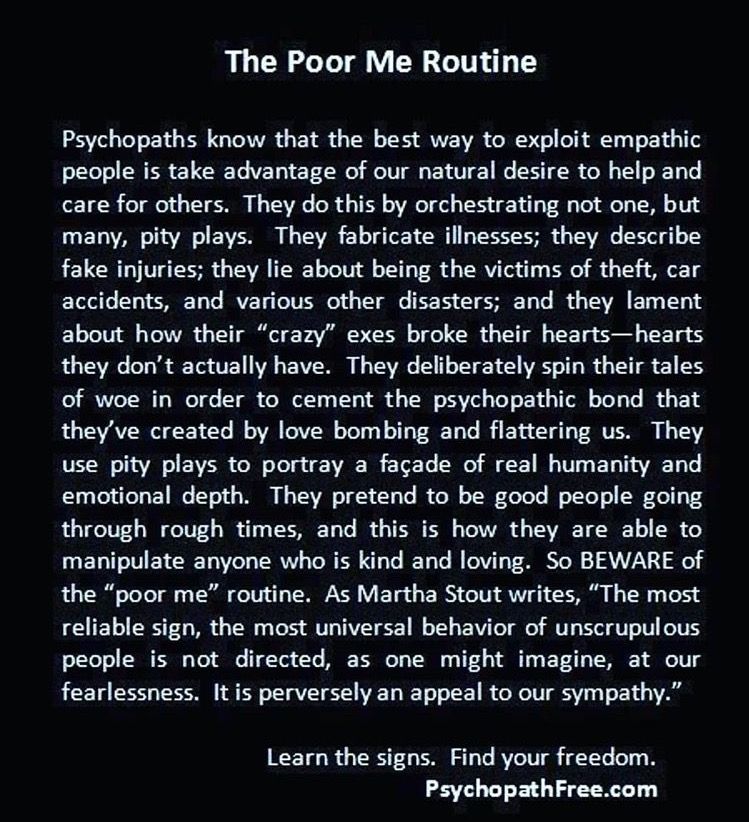

Phase 1: the seductiveness of psychopathic fiction

First impressions can be deceiving. Unfortunately, most of us may initially like a psychopath, because undeniable charm, good looks, eloquence, and skillful use of flattery and self-indulgence create an attractive image. However, the impression produced by a psychopath is reminiscent of a beautiful cover of a bad book. Unfortunately, there is one difference between books and people: we rarely buy a book without flipping through it or at least reading reviews, the same goes for buying a TV or a car - you are unlikely to decide on such a step without first studying their characteristics, but here the mask of a psychopath is often taken at face value. Since psychopaths present themselves in different ways, you can repeatedly fall for their bait. nine0012

Since psychopaths present themselves in different ways, you can repeatedly fall for their bait. nine0012

Therefore, it is wiser to be prudent (and even suspicious) by subjecting at least a general assessment of any new social contact, especially if it has the potential to affect your life in some way. At the very least, you should update your first impression of a person as you learn more about them, and have fallback routes in case you expose them or become uncomfortable around them.

Phase 2: formation of a psychopathic bond

Subtle charm and subtle manipulation can convince you that a psychopath likes you. During long conversations or meetings, he will try to convince you that he shares your beliefs, passions and views. As a rule, this happens imperceptibly; in fact, psychopathic manipulation can be so subtle that you will come to the conclusion that your views are similar just by listening to the psychopath's story about his life. Of course, all the stories he tells are carefully thought out and adapted to your hot buttons. In almost all the cases analyzed by the authors of the book, a common desire for all victims of psychopaths was the desire to find a kindred spirit, a person who shares their values, beliefs and life experience. You may feel a pleasant excitement, believing that the psychopath really feels sympathy and respect for you. In addition, you will begin to believe that a relationship with him, personal or professional, will develop. At this stage, many share personal information with the psychopath, believing that his story is true. nine0012

In almost all the cases analyzed by the authors of the book, a common desire for all victims of psychopaths was the desire to find a kindred spirit, a person who shares their values, beliefs and life experience. You may feel a pleasant excitement, believing that the psychopath really feels sympathy and respect for you. In addition, you will begin to believe that a relationship with him, personal or professional, will develop. At this stage, many share personal information with the psychopath, believing that his story is true. nine0012

Over time, the psychopath will make you believe that the two of you are special, unique and destined to be together. These insidious people try to present themselves as ideal friends, employees or business partners. This may require a lot of time and effort from them, and they usually court in secret. The attachment of a psychopath, unfortunately for you, is feigned and exists only in your imagination.

Attention to the formation of attachment is an excellent preventive measure. Be careful and do not rush to believe anyone's words. Building a serious relationship takes time, as well as common sense and careful evaluation. nine0012

Be careful and do not rush to believe anyone's words. Building a serious relationship takes time, as well as common sense and careful evaluation. nine0012

Phase 3: Participating in the psychopath's game

Once the psychopathic connection is established, you will find that your partner is using your vulnerabilities to force you into submission and strengthen the relationship. Surprisingly, this kind of "tug of war" often strengthens rather than weakens such a connection. This is especially true when you, against your will and against your own interests, do what you are asked to do in order to maintain a strong bond. Healthy relationships are harmonious: each participant gives something and receives something. The psychopathic connection is usually one-sided: you give, and he only receives (money, power, control). nine0012

When caught in a boss, co-worker, or emotional tyrant, try to find outward confirmation of your feelings. If you see that your relationship with this person is hurting you, it's time to end it.

Phase 4: self-doubt, guilt, and denial in psychopathic manipulation

The unscrupulous, deceitful, and manipulative behavior of psychopaths often confuses and destroys the victim. Some victims are tormented by doubts and blame themselves for what happened, while others generally deny the problem. In any case, doubts and fears about psychopaths turn into self-doubt. The situation is greatly aggravated if the victim cannot convince others, including family members and friends, that the cause of the trouble is not in her, but in someone else. “Everyone thought I was the problem,” is a phrase often repeated by those who have dealt with a psychopath. nine0012

It is difficult to help a person who, being unsure of himself, denies the obvious. The best thing that family members, friends or colleagues can do in this case is to provide victims with the necessary support by recommending that they contact the employee assistance program or mental health professionals.

Things get more complicated if the psychopath manages to convince your environment, including family and friends, that you are the problem! This state of affairs can be devastating and even make you question your own mental health. If you are lucky and those around you understand what is really happening, do not neglect their advice. In the workplace, employees who are of no value to the psychopath, his former victims, or those who noticed something was wrong can help you. nine0012

If you are lucky and those around you understand what is really happening, do not neglect their advice. In the workplace, employees who are of no value to the psychopath, his former victims, or those who noticed something was wrong can help you. nine0012

Phase 5: aggravation of the situation

If the psychopath's victims suddenly begin to ask questions about the inconsistency of his behavior with words, they are threatened with "punishment". At first, the psychopath categorically denies any inappropriate actions on his part and tries to go on the attack. Usually a person becomes ashamed of his suspicions, and as a result he begins to doubt himself even more. If the victims persist in expressing concern and suspicion, they are sure to fall under the hot hand of an angry psychopath. nine0012

Violence is different, most often psychological, emotional and physical. If you have been abused, immediately seek advice and help from those around you (friends, family members, or trusted colleagues).

Phase 6: Awareness and Understanding

Over time, constant lies, inconsistencies, negative emotions, and remarks from friends and family will lead you to think that you were a pawn in a psychopath's game. It will take a long time before you are convinced of the validity of your suspicions and accept this fact. Once that happens, everything will get better. nine0012

Realizing what happened, you will feel like a sucker. Many victims of psychopaths say to themselves, “How could you believe such a lie?!” This is a natural reaction, but it comes at a cost. People who feel fooled are reluctant to share it, and instead of trying to find confirmation or justification for their new opinion about the psychopath, they begin to avoid others.

Discussing your feelings with someone and writing about it in a diary is a good way to get rid of negative feelings. You may want to write down everything that happened after your encounter with the psychopath. And of course, you need to make sure that you have all the things in place: bank account, credit card, documents, computer, phone. It is very important to distance yourself from the psychopath and take measures to protect yourself from retribution from his side. Maybe you should (anonymously) post your story on a psychopath victim support group website. nine0012

It is very important to distance yourself from the psychopath and take measures to protect yourself from retribution from his side. Maybe you should (anonymously) post your story on a psychopath victim support group website. nine0012

Phase 7: Overcoming Shame

Shame is a natural response to abuse, and many cases of abuse go unreported because of this feeling. Meanwhile, it is extremely important to discuss it, if you have experienced this feeling, with family members, friends or specialists. It is necessary to seek help, firstly, because you do not deserve shame, just as you did not deserve violence. You are not to blame for anything: the psychopath is a social predator, and you have become his victim. Secondly, the very feeling of shame makes you an easy target for further manipulation. nine0012

Phase 8: Anger and Justification

Anger and the need for justification is a natural psychological response and an integral part of recovery. Anger may be the result of residual feelings that the victims constantly experienced, but due to fear and submission could not express. It is very important for the victim to work on their anger with a psychotherapist.

It is very important for the victim to work on their anger with a psychotherapist.

The need for justification is probably satisfied (at least for some people) by confirmation that the person they have been victimized is a psychopath. According to the stories of many people, the more they learned about the psychopathic process and, accordingly, understood it, the better they felt. It is very important to work through anger with a mental health professional, as thinking about past hurts only makes things worse, exacerbating the effects of psychological trauma. nine0012

Some people (actually most of us) seek to expose the psychopath and show the world his true face. At this stage, it is undesirable to widely talk about your feelings or make accusations on social networks, e-mail, messages and publications on the Internet. First of all, assess your current emotional state. Perhaps at the moment you are not able to think and act rationally. In addition, in a weakened state, it will not be easy for you to cope with a retaliatory blow.