People who hate

The Science Behind Why We Love to Hate

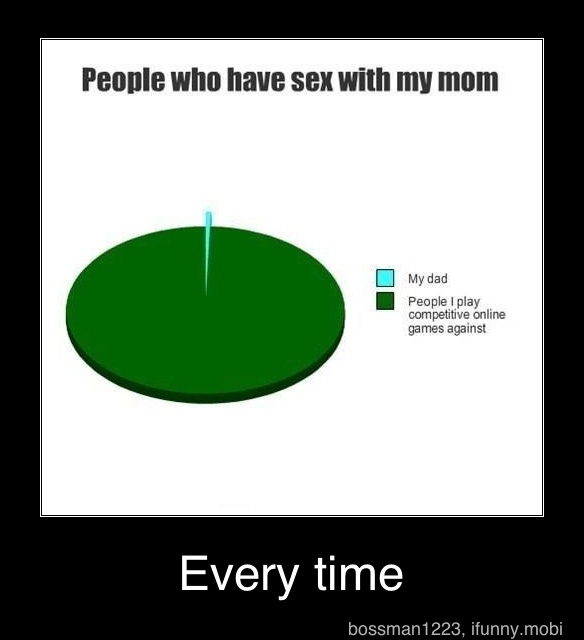

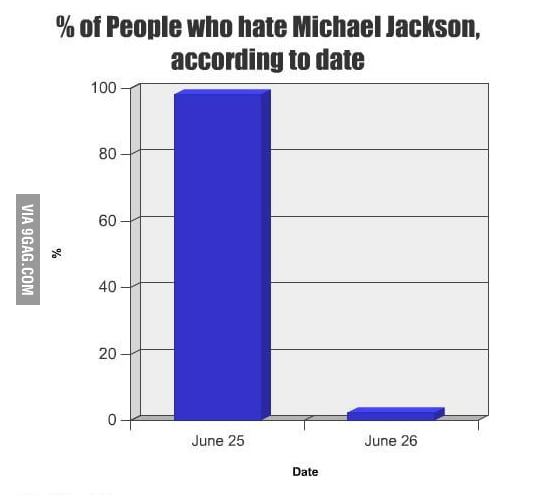

Have you ever heard the cliche, “no bond is stronger than two people who hate the same person?” It turns out there is actually some truth to that statement. Despite hating people being a socially unacceptable act, on the few occasions when people have the guts and/or strong emotion to motivate them to share their negative opinions about a person, it often pays off in the form of new or stronger connections.

Research has found that people form stronger bonds when they are able to talk about their dislike toward someone else than when they both have positive feelings toward someone. The question is, why does an action as disrespectful as spewing negativity about other people increase hateful individual’s quantity and quality of connections?

The Fiery Emotions that Fuel Hatred

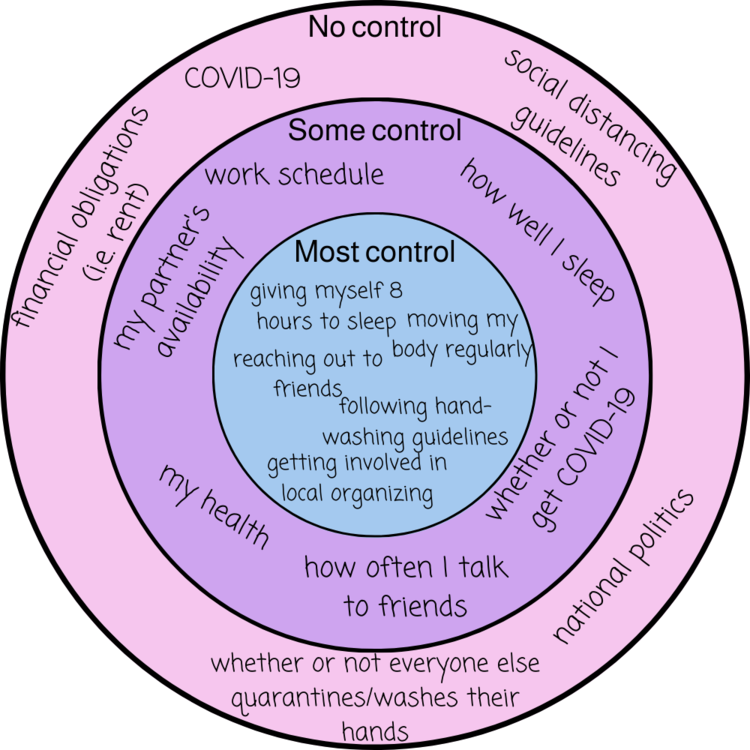

If you are a generally positive, forgiving person, the concept of hating others, much less someone you barely know, is a foreign concept to you. The majority of the time, people don’t say hateful things because they are a cruel, judgemental, antisocial person. Instead, common feelings and psychological needs bring out the worst behaviors in some individuals and prompt them to say negative statements about another person.

Here are four of the primary reasons why people hate others:

People want a scapegoat

When you are struggling, whether it’s problems at work, low self-esteem, conflicts in your relationships, etc., it feels much better to funnel your negative energy into blaming someone else than to confront your own role in your problems. A lot of people join hate groups because it allows them to funnel the blame for all of their problems into another group of people while being supported by a group of people who share their beliefs and make them feel like they belong.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

They’re lonely and seeking connections, even hateful ones

Many other people join hate groups because it fills their need for friendship and belonging. You don’t need to do or be anything special, all you have to do is be negative towards other people. It feels easy. Likewise, some people find it easier to make connections by putting others down and seeing who agrees than to prove to people that they are interesting and valuable companions.

It feels easy. Likewise, some people find it easier to make connections by putting others down and seeing who agrees than to prove to people that they are interesting and valuable companions.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

They fear the unknown

When someone new enters a group, particularly if they are in a position of influence, many people immediately begin gossiping negative things about the person because they fear how that individual will change their group dynamics. Sharing hatred toward the new person is a way for the existing group to strengthen their bonds in defensive against the outsider.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Their insecurities get the best of them

Hatred also surfaces when people are highly insecure. Often, they’ll compare themselves to other people and when they come to the conclusion that the other person may be better than them or possesses traits that they don’t want to acknowledge that they also share, people may speak out against that person to project their anxiety onto them.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Understanding the Bonding Power of Hatred

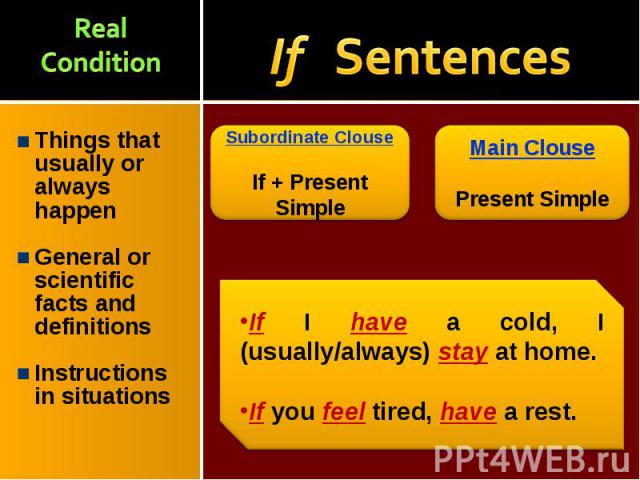

Expressing dislike for other people is controversial. We’re taught from a young age that you should only say nice things about other people, so when someone says something negative, it catches other people’s attention and draws them in. If people share the negative opinions, it opens the ability for people to form connections in three key ways:

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Humans desire structure and certainty in their social lives. To establish that, people naturally divide into in-groups (social circles where everyone feel like they belong with one another) and out-groups (people who exist outside of social circles and are typically not welcomed into them). When people declare their dislike for others, it helps people understand the boundaries between social circles. This is a powerful motivator for people to form bonds because it satisfies their need to feel connected to others.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Mutual dislike evokes a stronger response than mutual like

In one study, people were shown a video of two people having a conversation in which the man is politely hitting on the woman. After being asked if they liked or disliked the man, they were told they were going to meet people who shared their opinion of them and asked how likely they were going to get along with the person they meet. People who had a negative opinion of the man were far more likely to say they would get along well with someone who shared their negative opinion than those who had a positive opinion.

After being asked if they liked or disliked the man, they were told they were going to meet people who shared their opinion of them and asked how likely they were going to get along with the person they meet. People who had a negative opinion of the man were far more likely to say they would get along well with someone who shared their negative opinion than those who had a positive opinion.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Sharing hatred can be an expression of vulnerability

Research shows that to form lasting, intimate bonds with people, you have to be vulnerable with them–that is you have to share your authentic, unfiltered feelings. Instead of being negative toward another person because of the internal struggles described above, you may share that you hate someone for a valid, personal reason such as they hurt you or hurt someone and/or something you care about. This instance is a moment of vulnerability because you are sharing a difficult experience which can lead others to hate the other person on your behalf and bond with you.

↑ Table of Contents ↑

Bonds of Hatred Come at a Cost

Though there are some bonding benefits to spewing negativity about other people, don’t try to use this tactic to make friends because its risks far outweigh any good that comes from it. Be aware of these potential consequences of speaking poorly about others:

To know if someone else dislikes the same person as you, one of you has to make the first move and say something negative. This can come at a serious cost to your reputation of people around you if they do not agree with your negative opinions. Researchers have discovered that when we hear someone talking about other people, we impose the content of what’s said onto the speaker. It’s a phenomenon called spontaneous trait transference and to understand how it works, pretend you and I met at a conference and are having a conversation like this:

You: “Hey Vanessa, what did you think of the last speaker?”

Me: “Ugh, he was so boring and dry. I had trouble keeping myself awake. ”

”

This can go one of two ways: If you also thought the speaker was boring, we would bond over our shared dislike of him. But, if you thought the speaker was interesting or at the very least, deserving of a decent review, you would hear my opinion and think that I am boring and dry because your brain would project my statements onto me. It might not be instantaneous or something you’re fully conscious of, but how you feel about me would decrease in response toward my negativity toward another person.

On the flip side, if I raved about how intelligent the speaker was and how I loved his energy, your brain would also project those traits onto me and give you a more positive impression of me.

Another danger of sharing negative opinions toward other individuals, particularly when you are with people you don’t know well is that you create a negative emotional impression of yourself. People only remember a small portion of what you say however, they develop concrete memories of how you made them feel. If your words evoke anger, frustration, disgust and other cynical emotions in other people, they are going to associate those feelings with you. Most people don’t like feeling those ways and may be less eager to see you in the future because you bring down their emotional state.

If your words evoke anger, frustration, disgust and other cynical emotions in other people, they are going to associate those feelings with you. Most people don’t like feeling those ways and may be less eager to see you in the future because you bring down their emotional state.

Bottom line: Given these risks, unless your hatred is founded in a socially acceptable ideological belief, comes from a personal experience of being hurt or could be otherwise justified by most people, it is best to keep it to yourself.

The People Who Hate People

Of all the objections NIMBYs raise to new housing and infrastructure, perhaps the most risible is that their community is already too crowded.

By Jerusalem DemsasH. Armstrong Roberts / Retrofile / GettySome propositions are so obvious that no one takes the time to defend them. A few such propositions are that human life is good, that people can and often do provide more benefits to the world than they take away, and that we should design society to support people in leading lives that are good for themselves and others.

These ideas came under attack, sometimes subtly and sometimes overtly, by environmentalists in the 20th century who were worried about overpopulation. Although major organizations have abandoned population management as an explicit policy goal, the underlying fear that too many people are running up on the limits of too few resources and Well shouldn’t someone do something about that? has never fully been rooted out of American political thought. It is alive and well among NIMBYs. Of all the objections people raise to new housing and infrastructure, perhaps the most risible is that their community is already too crowded. Some even suggest that municipalities should limit housing supply explicitly to combat population growth.

At a recent Palo Alto city-council meeting, one resident argued against pro-housing policies, saying, “Does it make sense to be planning for more people? … More people on the planet spells more consequential implications for climate change, loss of biodiversity, stress, war, famine, etc. At a time when humans are in major ecological overshoot, doesn’t it make more sense to plan for a reduced population, plan for reducing population, not increasing it?”

At a time when humans are in major ecological overshoot, doesn’t it make more sense to plan for a reduced population, plan for reducing population, not increasing it?”

Invariably, the problem is always other people. The man behind the organization that sued UC Berkeley to reduce its enrollment, Phil Bokovoy, told The New Yorker that he opposed building more housing in Berkeley in part because “I don’t think we’ll be able to tackle climate change unless we tackle population growth and rising living standards over a huge part of the world.”

Lest you worry that this is a California-specific brain disease, let me reassure you that this antihuman thinking has permeated discourses all over the nation—and the world.

But population growth is not the problem that so many people seem to think it is, not least because of the global decline in fertility; arguably, declining population growth is the real population-related concern of the century. And even if it were a concern, the policies that NIMBYs support not only fail to create a climate-conscious built environment but actually make fighting climate change more difficult.

Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 book, The Population Bomb, catalyzed overpopulation concerns among the American public. Ehrlich, a Stanford biologist, also served as the first president of the group Zero Population Growth (ZPG). As the historian Keith Woodhouse recounts in his book, The Ecocentrists, “The group’s goal was an end to population growth; the means, troublingly, were not yet specified. Within three years [of its founding in 1970], ZPG had thirty-two thousand members.”

The Population Bomb opens not with a depiction of overconsumption by high-income Westerners but with the author’s memory of a taxi ride with his wife and daughter “one stinking hot night in Delhi.” Ehrlich describes the “crowded slum area” and proceeds to detail, in prose dripping with disgust, the view from his cab window of people just living their lives: “People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing, and screaming. People thrusting their hands through the taxi window, begging. ” This goes on and culminates in the almost-too-on-the-nose admission: “All three of us were, frankly, frightened.”

” This goes on and culminates in the almost-too-on-the-nose admission: “All three of us were, frankly, frightened.”

As Ehrlich’s family gawked at Delhiites, the U.S. was emitting 18.66 tons of carbon per capita to India’s .33, meaning that the average American was emitting 56 times more than the average Indian. If Ehrlich was genuinely concerned about overconsumption, why is the opening image of his book that of poor, brown people and not the suburban car-centric sprawl that characterizes his home country?

The book’s main argument is that an increasing population will run out of resources and if steps aren’t taken to reduce the population, then scarcity will make the world poor. In particular, Ehrlich was concerned about the world running out of food, and he foretold that mass starvation events would mark the waning decades of the 20th century.

Ehrlich’s dire predictions have been wrong time and again. Hunger and undernourishment have declined since The Population Bomb was released. To emphasize how alarmist his predictions were, a brief aside: In 1969, the author predicted that “by the year 2000 the United Kingdom will simply be a small group of impoverished islands, inhabited by some 70 million hungry people, of little or no concern to the other 5-7 billion inhabitants of a sick world,” later adding, “I would take even money that England will not exist in the year 2000.”

To emphasize how alarmist his predictions were, a brief aside: In 1969, the author predicted that “by the year 2000 the United Kingdom will simply be a small group of impoverished islands, inhabited by some 70 million hungry people, of little or no concern to the other 5-7 billion inhabitants of a sick world,” later adding, “I would take even money that England will not exist in the year 2000.”

As careful students of history know well, England still exists.

To say that overpopulation hysterics were simply wrong is too generous. Twentieth-century critics on the left saw the movement for what it was: In the 1970s, New Left activists and Students for a Democratic Society both criticized ZPG and overpopulation mania. The latter group, Woodhouse writes, “accused ZPG of reckless simplification, reasoning that by treating all people as a single flat category, population activists ignored not only human difference but also human value.” New Left activists specifically called out the underlying racism of ZPG’s project: “ZPG says that there are too many people, especially non-white people, in the world … that these people are terrifying and violent, and that their population growth must be stopped—by ‘coercion’ if necessary. ”

”

One legacy of this intellectual tradition is the modern xenophobic anti-immigration movement. The Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), founded by John Tanton, was instrumental in advocating for strict immigration controls. (To get a flavor for the callousness of this group, check their website, which tells visitors “How to Report Illegal Aliens.”)

Tanton was president of ZPG from 1975 to 1977 and, as the historian Sebastian Normandin and the philosopher Sean A. Valles wrote in a 2015 paper, FAIR “began as a 1979 offshoot of ZPGs Immigration Committee, following ZPG approval of the proposal in 1978.” While the blend of “1960s ecology and neo-eugenics” seems “idiosyncratic or even fringe today … their influence remains.” The authors conclude that “today’s immigration restrictionist network was built and led by—and in some cases is still led by—a network of conservationists and population control activists.”

Tanton’s anti-immigration views were not just compatible with his concerns about overpopulation; they were born out of them: As Jason Riley wrote in 2019 for The Wall Street Journal, “Opposition to immigration, legal or illegal, was simply a means to that end. ”

”

What should be obvious, but apparently is not, is that opposing immigration actually reduces the U.S.’s ability to cultivate and take advantage of brilliant people who could develop the technological advances to save the planet. (Thirty-seven percent of American Nobel Prize winners in chemistry, medicine, and physics from 2000 to 2020 have been immigrants.)

A growing population means more people generating more ideas, but also more interactions among different people coming from different perspectives. These two effects can sound trivial but actually do lead to more and better ideas. The economist Hisakazu Kato argued in 2016 that “a large population will generate many ideas that could bring about rapid technological progress.”

Overpopulation concern-mongers not only underestimate the ability of people to help solve the problems of climate change; they also fail to accept that neither resources nor human needs are fixed. The idea that resources will “run out” implies that human ingenuity will remain stagnant. But it doesn’t. Norman E. Borlaug won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 (just two years after The Population Bomb was published) for helping Mexico become “self-sufficient in grain” by developing “a robust strain of wheat—dwarf wheat—that was adapted to Mexican conditions.” He then worked in India and Pakistan to introduce dwarf wheat to the countries’ agricultural landscape and became known as the father of the “Green Revolution.”

But it doesn’t. Norman E. Borlaug won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 (just two years after The Population Bomb was published) for helping Mexico become “self-sufficient in grain” by developing “a robust strain of wheat—dwarf wheat—that was adapted to Mexican conditions.” He then worked in India and Pakistan to introduce dwarf wheat to the countries’ agricultural landscape and became known as the father of the “Green Revolution.”

As Gregg Easterbrook noted some years ago in The Atlantic, Ehrlich had written in 1968 that it was a “fantasy” that India would “ever” feed itself. But “by 1974 India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals.” Borlaug himself was concerned about population growth, but instead of pursuing an anti-humanist agenda, he turned to technological innovation to save countless lives.

The economist Julian Simon, a longtime critic of the overpopulation activists, bet Ehrlich that the price of five metals would fall from 1980 to 1990. As The New York Times noted in Simon’s obituary, Ehrlich believed that “rising demand for raw materials by an exploding global populace would pare supplies of nonrenewable resources, driving up prices.” Simon won the bet.

As The New York Times noted in Simon’s obituary, Ehrlich believed that “rising demand for raw materials by an exploding global populace would pare supplies of nonrenewable resources, driving up prices.” Simon won the bet.

If the overpopulation alarmists of the 1970s had really wanted, above all, to protect the environment, they should have promoted the development of dense, energy-efficient communities.

The evidence is clear, and has been for some time, that density is good for the environment. As UC Berkeley researchers argued in a 2014 paper, “population-dense cities contribute less greenhouse-gas emissions per person than other areas of the country,” and “the average carbon footprint of households living in the center of large, population-dense urban cities is about 50 percent below average, while households in distant suburbs are up to twice the average.”

But the people worried about other people don’t have a pro-density history; quite the opposite.

As the urban planner Greg Morrow detailed in his 2013 dissertation, overpopulation activists fought for the very legal frameworks that would keep cities low-density and worsen suburban sprawl. Morrow noted that in the early 1970s, the UCLA professor Fred Abraham, then-president of ZPG of Los Angeles, argued that “we need fewer people here—a quality of life, not a quantity of life. We must request a moratorium on growth and recognize that growth should be stopped.” Morrow added that “the Sierra Club (L. Douglas DeNike) agreed and suggested ‘limiting residential housing is one approach to lower birth rates’ and recommended ‘a freeze on zoning to limit new residential construction.’”

Morrow noted that in the early 1970s, the UCLA professor Fred Abraham, then-president of ZPG of Los Angeles, argued that “we need fewer people here—a quality of life, not a quantity of life. We must request a moratorium on growth and recognize that growth should be stopped.” Morrow added that “the Sierra Club (L. Douglas DeNike) agreed and suggested ‘limiting residential housing is one approach to lower birth rates’ and recommended ‘a freeze on zoning to limit new residential construction.’”

Half a century later, NIMBYs who cite overpopulation concerns when opposing new housing say they are afraid of overcrowding on their streets and in their parking lots. Some continue to invoke the global South as a dark warning for the future. In an interview with Slate’s Henry Grabar, Bokovoy, the Berkeley anti-growth activist, warned that his city could end up like “Bangkok, Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur” if more students are allowed to attend the local UC campus. In Trussville, Alabama, the president of a local homeowners’ association played all the hits as he stated his opposition to the inclusion of multifamily housing in a new development in his area: “You’re bringing that many more people with that many more cars,” he complained. “We envision this side of town as spacious properties, higher home values … not having crowded streets.”

“We envision this side of town as spacious properties, higher home values … not having crowded streets.”

We have, of course, discovered an elusive technology to allow more people to live on less land: It’s called an apartment building. And if people would like fewer neighbors competing for parking spaces, then they should rest assured that buses, trains, protected bike lanes, and maintained sidewalks are effective, cutting-edge inventions available to all.

Perhaps you’re pessimistic about technology’s ability to help solve the big environmental problems we’re facing. You may not trust that technology could ever be sufficient to reduce carbon emissions, or that our political systems could make that technology widespread.

If that is the case, think for a second about what it would take to slash the population down by several billion. (Ehrlich himself recently put the optimal number at 1.5 to 2 billion.) The only way to do this is to kill people, limit the aid you give to sick people, and/or stop new people from being born.

Some believe that the third approach could be adequate, and achieved simply by providing people with contraceptives. But survey data show that women are actually having fewer children than they would like, so providing more family-planning services is not going to cut the population by four-fifths.

NIMBYs and overpopulation alarmists share a sense that the world is too full, that their communities are for the people who already live there, and that new people—immigrants from abroad or the next state over—are simply burdens. And in doing so, they create the world they imagine: unacceptable rates of homelessness, a country lagging far behind its peers in building mass transit, and declining trust.

“I think once you get past this idea that NIMBYs are simply curmudgeons or busybodies then you start to realize why this attitude toward growth today— which in the context of the present housing crises and cost of living crises seems so ridiculous—actually has very firmly embedded ideological roots within…liberalism and thus why it’s so difficult to root out among people who consider themselves liberals,” the historian Jacob Anbinder explained to me.

Between a politics of scarcity that demands inhumane policy interventions and a politics of abundance, it’s not much of a choice, but it’s one that population skeptics have to make. Enough with the innuendo: If overpopulation is the hill you want to die on, then you’ve got to defend the implications.

What are the names of people who hate people?

Every day we meet dozens of people with different personalities, problems, phobias and lifestyles. Among them there is at least one percent with a serious personality disorder and forms of individualism. The most interesting are people who hate people. Today this issue is especially relevant, because any such deviation from the accepted norm can be harmless and dangerous. Each of these disorders in science has been given specific definitions, signs of manifestation and causes are described. So what are people called who don't like people? Let's try to figure it out. nine0003

Sociopaths

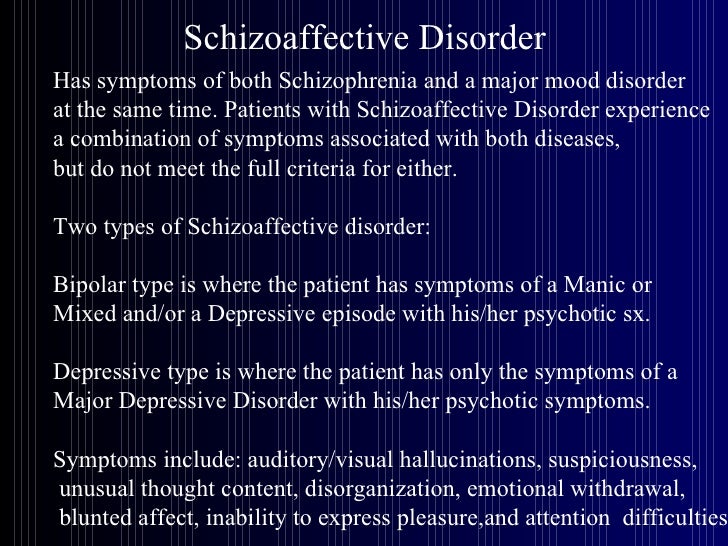

Quite a common personality disorder, manifested in the systematic violation of social norms, aggression towards people and the inability to build friendly relationships with them. Visually, a sociopath can be described as a frequently conflicted person who is unable to show empathy towards others. Simply put, these are people who hate people, do not seek to make new acquaintances. But they cannot be called unsociable. They show interest in others, but "throw off" any burden of obligations to them. At the same time, sociopaths do not have a sense of guilt. Sociopathy is classified as a dangerous disorder, since the patient, not getting what he wants, can be aggressive and even resort to violence. Sociopathy breaks the character and behavior of the patient. If left untreated, the disorder will become uncontrollable. nine0003

Visually, a sociopath can be described as a frequently conflicted person who is unable to show empathy towards others. Simply put, these are people who hate people, do not seek to make new acquaintances. But they cannot be called unsociable. They show interest in others, but "throw off" any burden of obligations to them. At the same time, sociopaths do not have a sense of guilt. Sociopathy is classified as a dangerous disorder, since the patient, not getting what he wants, can be aggressive and even resort to violence. Sociopathy breaks the character and behavior of the patient. If left untreated, the disorder will become uncontrollable. nine0003

How to stop hating people? Recommendations...

Life is complicated. Sometimes it is difficult to sort out one's feelings, because it is not always clear...

Experts do not have a common opinion about the clear causes of a person's sociopathy. However, there are assumptions about congenital (hereditary) and acquired mental pathology. The latter is due to the conditions of development and formation of personality (strict parents, excessive criticism and demands). nine0003

The latter is due to the conditions of development and formation of personality (strict parents, excessive criticism and demands). nine0003

Misanthropes

Often on the forums you can meet the question: "What are people called who do not like people?" And among the many answers slips the term "misanthrope." Who are they and how to recognize misanthropes? Such people either have no friends, or a very narrow circle of friends. They eschew noisy companies, the misanthropes themselves call their desire for loneliness philosophy or individuality. Misanthropes are characterized by pessimism, distrust, and excessive suspicion. The extreme form is the enjoyment of hatred for people. But, despite the obvious alienation and unsociableness, misanthropes are harmless. Among them, history knows talented creative personalities: A. Schopenhauer, J. Swift, A. Gordon. nine0003

Black magic: punish the enemy at home by...

The article tells about what black magic is capable of. Punish the enemy, return the negative...

Punish the enemy, return the negative...

A person usually comes to misanthropy when he is not satisfied with the environment, communication with people, their actions. This process is often accompanied by depression and a reshuffling of priorities.

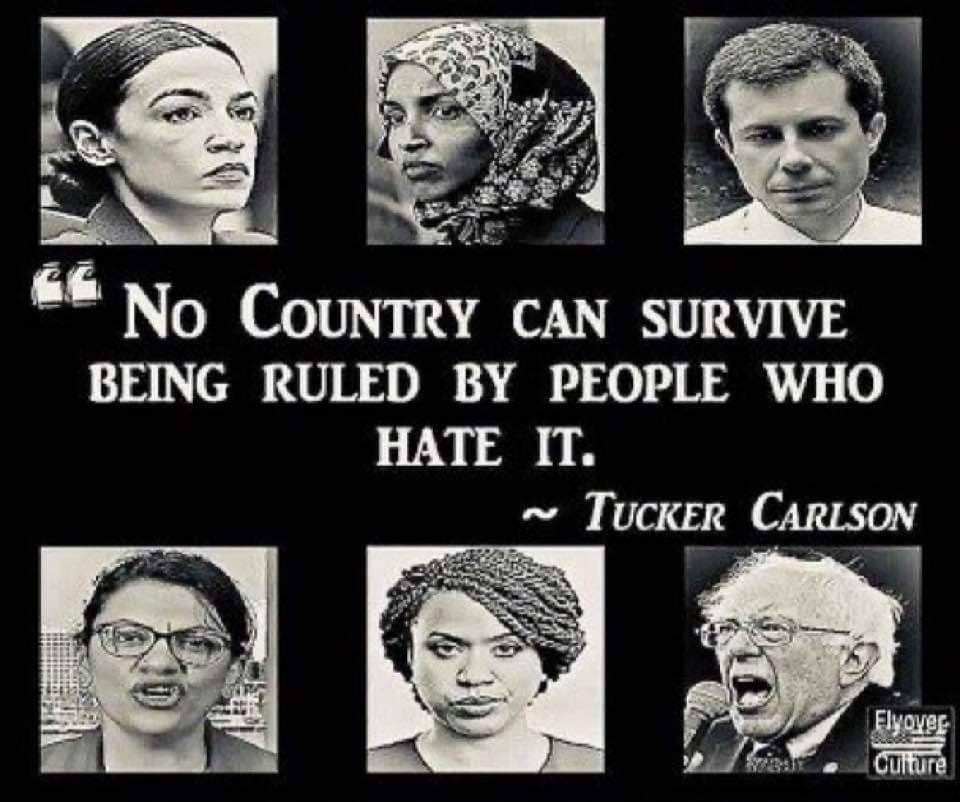

Xenophobes

Another form of human hostility is xenophobia. Unlike the previous ones, it is characterized by ideology. Xenophobes are not just people who hate people. Their hostility is associated with a specific feature: national, religious, racial. Experts believe that the roots of xenophobia are hidden in the biological theory of protective reflexes. When a person sees people with a different appearance, mannerisms, character and behavior, at the biological level, the instinct to preserve his species works in him. It is he who prevents the formation of interracial and interethnic marriages. A similar phenomenon can be observed in the animal world. In society, xenophobia acquires a hostile, aggressive character when it becomes an idea. In the modern world, the concepts of "xenophobia", "racism" and "nationalism" have become identical. nine0003

In the modern world, the concepts of "xenophobia", "racism" and "nationalism" have become identical. nine0003

Misanthrope - who is this? What personality traits are inherent in people...

In the lexicon of a modern person, one can increasingly hear terms that have come to us from others...

Nationalists

Today, there is rarely anyone who does not know what people are called who do not like people of another nationality. Nationalism has gone through several stages in its history. Each of them was sometimes uniting, sometimes aggressive. Today, nationalism is part of the state policy that protects the interests of its people in a constitutional way. However, this kind of xenophobia has many faces. History remembers many examples of aggressive nationalism (from ancient Rome to the present day). There are people who hate people of another nation, but show their intolerance quite peacefully. When it becomes a mass phenomenon, it is worth talking about extremism. nine0003

nine0003

Racists

Since the days of colonization, people who do not like people of a different skin color have been called racists. Of course, this phenomenon is much wider. It is based on spiritual, intellectual and physical inequalities. Racists clearly divide society into superior and inferior races and seek to consolidate a certain hierarchy. All this turns into a beautiful ideology of the world order. However, experts believe that racism is one of the forms of phobias towards the “alien”.

Racists can be conditionally divided into two groups. The first includes people who hate people of a different race and in every possible way deny any contact with them, seek to dominate or eradicate them (extreme). Another group of racists behave tolerantly towards other races. But he categorically denies close relations with them (marriage, kinship). nine0003

Animal lovers

“The more I get to know people, the more I like dogs,” the famous misanthrope Schopenhauer once wrote. But not all misanthropes love animals. What do you call people who don't like people but love animals? The term "animal lover" is usually used here. Such people have a dozen cats, dogs or other pets at home. These are selfless volunteers protecting the rights and lives of animals. But no matter how strong their love for the animal world is, they try to avoid human society. Moreover, they feel dislike. nine0003

But not all misanthropes love animals. What do you call people who don't like people but love animals? The term "animal lover" is usually used here. Such people have a dozen cats, dogs or other pets at home. These are selfless volunteers protecting the rights and lives of animals. But no matter how strong their love for the animal world is, they try to avoid human society. Moreover, they feel dislike. nine0003

The causes of animal love are various. Everyone has their own story: depression, personal philosophy, disappointment in people, betrayal, betrayal, old age, etc. Experts say that not all animal lovers are misanthropes. Many of them have families, like-minded friends. This means that they are capable of loving people.

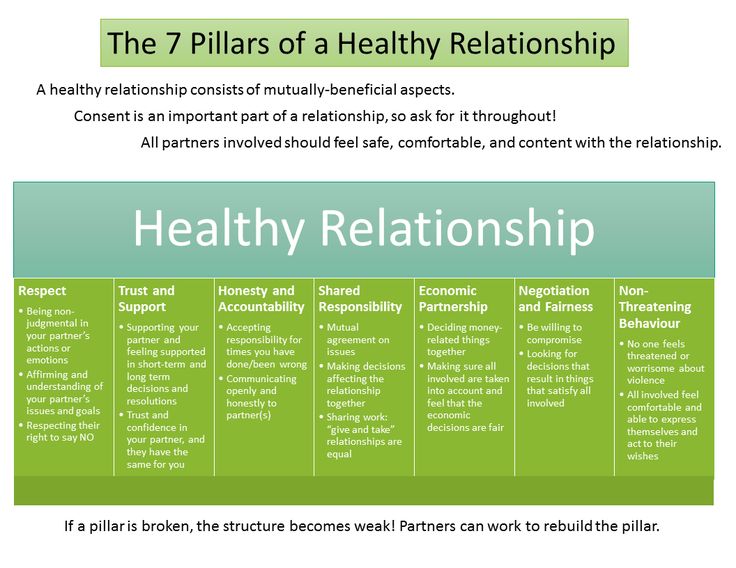

Tolerance is the way to harmony

People who hate people are called different concepts. Since their dislike wears different shades of manifestation. Summarizing, one clear and correct conclusion can be drawn: any hostility towards people is unnatural for a person. Therefore, it leads to aggression, the destruction of man and the world. nine0003

Therefore, it leads to aggression, the destruction of man and the world. nine0003

According to statistics, up to 3 percent of the world's population suffer from such disorders. And that's millions! Of these, only a few turn to specialists for help. The rest consider it a style or philosophy of life, their own ideology, politics. To resolve the situation, you need to understand the cause and try to find ways to solve it. And act! As a rule, the first sprouts of human hostility usually take root in childhood. Therefore, it is very important to educate in children a sense of tolerance and equality between people, regardless of their gender, social status, nationality and race. nine0003

Without hiding hostility - who is a misanthrope?

There are people who can't stand oranges. There are those who do not like mass gatherings of people. And there are people who simply do not like humanity, they would gladly become the main characters of Ray Bradbury's story "Vacation". We tell you who misanthropes are and what to do with them.

Who is a misanthrope?

A misanthrope is a person who despises, hates other people, feels rejection towards them. Moreover, his neglect applies to all people in general, which separates the misanthrope from sexists, racists and opponents of certain groups of people. He dislikes humanity as a species, like Agent Smith, he believes that homo sapiens is a virus that destroys the beautiful world created by nature. Therefore, humanity needs to multiply less, and in rather radical forms of misogyny, people can simply wrap themselves in sheets and self-destruct. nine0003

What do misanthropes dislike about people?

It's no secret that people are far from ideal creatures from the picture, where everyone is nice, smiles at each other, smells like lavender and doesn't know what violence is. However, misanthropes elevate the shortcomings of humanity to the status of vices. In total there are three large groups of main sources of claims.

Aesthetic flaws

Not the main reason misanthropes dislike humanity in general, but aesthetic flaws are often mentioned in misanthropes' public writings. They do not like the desire of mankind for beauty, but they also do not like the manifestation of human ugliness, unpleasant odors of sweat and other secretions, aging, obsession with appearance. nine0003

They do not like the desire of mankind for beauty, but they also do not like the manifestation of human ugliness, unpleasant odors of sweat and other secretions, aging, obsession with appearance. nine0003

Intellectual deficiencies

This list includes a tendency to false beliefs that limit the possibilities of cognition or even interfere with acting rationally. Human stupidity, naivety, bias are added to them.

Moral shortcomings

These include cruelty, indifference to the suffering of others, selfishness, moral laziness, cowardice, injustice, greed and ingratitude. The damage caused by these vices can be divided into three categories: harm caused directly to other people, harm caused directly to animals, and harm caused indirectly to both humans and animals as a result of environmental damage. Examples of these categories include the Holocaust, animal husbandry, and pollution causing climate change. nine0003

Misanthropes in culture

The word misanthrope comes from the Greek word misanthrōpos, its spread across Europe in the 17th century was facilitated by the play of the same name by Molière, although characters with a similar temperament were also found in William Shakespeare and later in Gustave Flaubert.

Today, when humanity has realized and acknowledged its shortcomings, the image of a misanthrope often appears in movies and TV shows: sometimes as a villain, sometimes as an object for laughter. Here are some stories about misanthropes. nine0003

Saint Vincent

2014 dir. Ted Murphy

Maggie just got divorced and moved to another city with her young son. She works around the clock and, so that the child does not stay alone for a long time, she asks her neighbor - a veteran of the Vietnam War - to look after the boy. And it does not strike her at all that dear Vincent hates people.

A Christmas Carol

2009, dir. Robert Zemeckis

A classic story written by Charles Dickens and adapted many times.