Can low thyroid cause depression

The Link between Thyroid Function and Depression

1. D'haenen H, Boer JAD, Willner P. Biological Psychiatry. Vol. 1. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2002 . [Google Scholar]

2. Wolkowitz OM, Rothschild AJ. Psychoneuroendocrinology: The Scientific Basis of Clinical Practice. 1st edition. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychiatric; 2003. [Google Scholar]

3. Larsen PR, Silva JE, Kaplan MM. Relationships between circulating and intracellular thyroid hormones: physiological and clinical implications. Endocrine Reviews. 1981;2(1):87–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Van Doorn J, Roelfsema F, Van Der Heide D. Concentrations of thyroxine and 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine at 34 different sites in euthyroid rats as determined by an isotopic equilibrium technique. Endocrinology. 1985;117(3):1201–1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Chanoine JP, Alex S, Fang SL, et al. Role of transthyretin in the transport of thyroxine from the blood to the choroid plexus, the cerebrospinal fluid, and the brain. Endocrinology. 1992;130(2):933–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Robbins J, Lakshmanan M. The movement of thyroid hormones in the central nervous system. Acta Medica Austriaca. 1992;19(supplement 1):21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Visser WE, Friesema ECH, Jansen J, Visser TJ. Thyroid hormone transport in and out of cells. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;19(2):50–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Williams GR. Neurodevelopmental and neurophysiological actions of thyroid hormone. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2008;20(6):784–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Taylor JW. Depression in thyrotoxicosis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1975;132(5):552–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Kathol RG, Delahunt JW. The relationship of anxiety and depression to symptoms of hyperthyroidism using operational criteria. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1986;8(1):23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Trzepacz PT, McCue M, Klein I, Levey GS, Greenhouse J. A psychiatric and neuropsychological study of patients with untreated Graves’ disease. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1988;10(1):49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A psychiatric and neuropsychological study of patients with untreated Graves’ disease. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1988;10(1):49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Whybrow PC, Prange AJ, Jr., Treadway CR. Mental changes accompanying thyroid gland dysfunction. A reappraisal using objective psychological measurement. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1969;20(1):48–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Demartini B, Masu A, Scarone S, Pontiroli AE, Gambini O. Prevalence of depression in patients affected by subclinical hypothyroidism. Panminerva Medica. 2010;52(4):277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Bauer M, Silverman DHS, Schlagenhauf F, et al. Brain glucose metabolism in hypothyroidism: a positron emission tomography study before and after thyroid hormone replacement therapy. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;94(8):2922–2929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Joffe RT, Levitt AJ. Basal thyrotropin and major depression: relation to clinical variables and treatment outcome. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;53(12):833–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;53(12):833–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Saravanan P, Chau WF, Roberts N, Vedhara K, Greenwood R, Dayan CM. Psychological well-being in patients on ’adequate’ doses of L-thyroxine: results of a large, controlled community-based questionnaire study. Clinical Endocrinology. 2002;57(5):577–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Panicker V, Saravanan P, Vaidya B, et al. Common variation in the DIO2 gene predicts baseline psychological well-being and response to combination thyroxine plus triiodothyronine therapy in hypothyroid patients. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;94(5):1623–1629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Van Der Deure WM, Appelhof BC, Peeters RP, et al. Polymorphisms in the brain-specific thyroid hormone transporter OATP1C1 are associated with fatigue and depression in hypothyroid patients. Clinical Endocrinology. 2008;69(5):804–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Baskin HJ, Cobin RH, Duick DS. American association of clinical endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the evaluation and treatment of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Endocrine Practice. 2002;8(6):457–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Baskin HJ, Cobin RH, Duick DS. American association of clinical endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the evaluation and treatment of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Endocrine Practice. 2002;8(6):457–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Ingram RE. The International Encyclopedia of Depression. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

21. Loosen PT. Hormones of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis: a psychoneuroendocrine perspective. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1986;19(6):401–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Vandoolaeghe E, Maes M, Vandevyvere J, Neels H. Hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid-axis function in treatment resistant depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1997;43(2):143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Bauer MS, Whybrow PC, Winokur A. Rapid cycling bipolar affective disorder. I. Association with grade I hypothyroidism. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47(5):427–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Jackson IMD. The thyroid axis and depression. Thyroid. 1998;8(10):951–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jackson IMD. The thyroid axis and depression. Thyroid. 1998;8(10):951–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Sullivan GM, Hatterer JA, Herbert J, et al. Low levels of transthyretin in the CSF of depressed patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(5):710–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Pilhatsch M, Winter C, Nordström K, Vennström B, Bauer M, Juckel G. Increased depressive behaviour in mice harboring the mutant thyroid hormone receptor alpha 1. Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;214(2):187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Hennemann G, Docter R, Friesema ECH, De Jong M, Krenning EP, Visser TJ. Plasma membrane transport of thyroid hormones and its role in thyroid hormone metabolism and bioavailability. Endocrine Reviews. 2001;22(4):451–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Hatterer JA, Herbert J, Hidaka C, Roose SP, Gorman JM. CSF transthyretin in patients with depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150(5):813–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Sullivan GM, Hatterer JA, Herbert J, et al. Low levels of transthyretin in the CSF of depressed patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(5):710–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Sullivan GM, Mann JJ, Oquendo MA, Lo ES, Cooper TB, Gorman JM. Low cerebrospinal fluid transthyretin levels in depression: correlations with suicidal ideation and low serotonin function. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(5):500–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Suzuki T, Abe T. Thyroid hormone transporters in the brain. Cerebellum. 2008;7(1):75–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Chopra IJ, Solomon DH, Huang TS. Serum thyrotropin in hospitalized psychiatric patients: evidence for hyperthyrotropinemia as measured by an ultrasensitive thyrotropin assay. Metabolism. 1990;39(5):538–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Bahls SC, De Carvalho GA. The relation between thyroid function and depression: a review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2004;26(1):41–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2004;26(1):41–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Jackson IMD, Luo LG. Antidepressants inhibit the glucocorticoid stimulation of thyrotropin releasing hormone expression in cultured hypothalamic neurons. Journal of Investigative Medicine. 1998;46(9):470–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Williams MD, Harris R, Dayan CM, Evans J, Gallacher J, Ben-Shlomo Y. Thyroid function and the natural history of depression: findings from the Caerphilly Prospective Study (CaPS) and a meta-analysis. Clinical Endocrinology. 2009;70(3):484–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Premachandra BN, Kabir MA, Williams IK. Low T3 syndrome in psychiatric depression. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2006;29(6):568–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Kirkegaard C, Korner A, Faber J. Increased production of thyroxine and inappropriately elevated serum thyrotropin in levels in endogenous depression. Biological Psychiatry. 1990;27(5):472–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Linnoila M, Lamberg BA, Potter WZ. High reverse T3 levels in manic and unipolar depressed women. Psychiatry Research. 1982;6(3):271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Linnoila M, Lamberg BA, Potter WZ. High reverse T3 levels in manic and unipolar depressed women. Psychiatry Research. 1982;6(3):271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Kirkegaard C, Faber J. Altered serum levels of thyroxine, triiodothyronines and diiodothyronines in endogenous depression. Acta Endocrinologica. 1981;96(2):199–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Nemeroff CB. Clinical significance of psychoneuroendocrinology in psychiatry: focus on the thyroid and adrenal. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1989;50:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Linnoila M, Cowdry R, Lamberg BA. CSF triiodothyronine (rT3) levels in patients with affective disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 1983;18(12):1489–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Nemeroff CB, Simon JS, Haggerty JJ, Evans DL. Antithyroid antibodies in depressed patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142(7):840–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Joffe RT. Antithyroid antibodies in major depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1987;76(5):598–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1987;76(5):598–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Haggerty JJ, Jr., Evans DL, Golden RN, Pedersen CA, Simon JS, Nemeroff CB. The presence of antithyroid antibodies in patients with affective and nonaffective psychiatric disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 1990;27(1):51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Gold MS, Pottash ALC, Extein I. ’Symptomless’ autoimmune thyroiditis in depression. Psychiatry Research. 1982;6(3):261–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Fountoulakis KN, Iacovides A, Grammaticos P, Kaprinis GS, Bech P. Thyroid function in clinical subtypes of major depression: an exploratory study. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4, article 6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Monteleone P. Circadian rhythm disturbances in depression: implications for treatment and quality of remission. Medicographia. 2009;31(2):132–139. [Google Scholar]

48. Souetre E, Salvati E, Wehr TA, Sack DA, Krebs B, Darcourt G. Twenty-four-hour profiles of body temperature and plasma TSH in bipolar patients during depression and during remission and in normal control subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;145(9):1133–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Twenty-four-hour profiles of body temperature and plasma TSH in bipolar patients during depression and during remission and in normal control subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;145(9):1133–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Poirier MF, Lôo H, Galinowskia A, et al. Sensitive assay of thyroid stimulating hormone in depressed patients. Psychiatry Research. 1995;57(1):41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Prange AJ, Jr., Lara PP, Wilson IC, Alltop LB, Breese GR. Effects of thyrotropin-releasing hormone in depression. The Lancet. 1972;2(7785):999–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Kastin AJ, Ehrensing RH, Schalch DS, Anderson MS. Improvement in mental depression with decreased thyrotropin response after administration of thyrotropin-releasing hormone. The Lancet. 1972;2(7780):740–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Nemeroff CB, Evans DL. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), the thyroid axis, and affective disorder.

Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1989;553:304–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Loosen PT, Prange AJ., Jr. Serum thyrotropin response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone in psychiatric patients: a review. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1982;139(4):405–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Kirkegaard C. The thyrotropin response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone in endogenous depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1981;6(3):189–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Hinkle PM, Tashjian AH., Jr. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone regulates the number of its own receptors in the Gh4 strain of pituitary cells in culture. Biochemistry. 1975;14(17):3845–3851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Garbutt JC, Mayo JP, Little KY, et al. Dose-response studies with protirelin. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51(11):875–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Kirkegaard C, Faber J, Hummer L, Rogowski P. Increased levels of TRH in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with endogenous depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1979;4(3):227–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Banki CM, Bissette G, Arato M, Nemeroff CB. Elevation of immunoreactive CSF TRH in depressed patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;145(12):1526–1531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Duval F, Mokrani MC, Bailey P, et al. Thyroid axis activity and serotonin function in major depressive episode. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1999;24(7):695–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Duval F, Mokrani MC, Crocq MA, Bailey P, Macher JP. Influence of thyroid hormones on morning and evening TSH response to TRH in major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 1994;35(12):926–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Otsuki M, Dakoda M, Baba S. Influence of glucocorticoids on TRF-induced TSH response in man. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1973;36(1):95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Zeng H, Schimpf BA, Rohde AD, Pavlova MN, Gragerov A, Bergmann JE. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1-deficient mice display increased depression and anxiety-like behavior. Molecular Endocrinology. 2007;21(11):2795–2804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Prange AJ, Jr., Wilson IC, Rabon AM, Lipton MA. Enhancement of imipramine antidepressant activity by thyroid hormone. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1969;126(4):457–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Wheatley D. Potentiation of amitriptyline by thyroid hormone. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1972;26(3):229–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Wilson IC, Prange AJ, McClane TK, Rabon AM, Lipton MA. Thyroid-hormone enhancement of imipramine in nonretarded depressions. New England Journal of Medicine. 1970;282(19):1063–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Coppen A, Whybrow PC, Noguera R, Maggs R, Prange AJ. The comparative antidepressant value of L-tryptophan and imipramine with and without attempted potentiation by liothyronine. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1972;26(3):234–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Altshuler LL, Bauer M, Frye MA, et al. Does thyroid supplementation accelerate tricyclic antidepressant response? A review and meta-analysis of the literature. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(10):1617–1622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Aronson R, Offman HJ, Joffe RT, David Naylor C. Triiodothyronine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression: a meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53(9):842–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Papakostas GI, Cooper-Kazaz R, Appelhof BC, et al. Simultaneous initiation (coinitiation) of pharmacotherapy with triiodothyronine and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for major depressive disorder: a quantitative synthesis of double-blind studies. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;24(1):19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Cooper-Kazaz R, van der Deure WM, Medici M, et al. Preliminary evidence that a functional polymorphism in type 1 deiodinase is associated with enhanced potentiation of the antidepressant effect of sertraline by triiodothyronine. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;116(1-2):113–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Joffe RT, Singer W. A comparison of triiodothyronine and thyroxine in the potentiation of tricyclic antidepressants. Psychiatry Research. 1990;32(3):241–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Baumgartner A. Thyroxine and the treatment of affective disorders: an overview of the results of basic and clinical research. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;3(2):149–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Bauer M, Berghöfer A, Bschor T, et al. Supraphysiological doses of L-Thyroxine in the maintenance treatment of prophylaxis-resistant affective disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(4):620–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Bauer M, Goetz T, Glenn T, Whybrow PC. The thyroid-brain interaction in thyroid disorders and mood disorders. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2008;20(10):1101–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Joffe RT, Singer W. The effect of tricyclic antidepressants on basal thyroid hormone levels in depressed patients. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1990;23(2):67–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Rao ML, Ruhrmann S, Retey B, et al. Low plasma thyroid indices of depressed patients are attenuated by antidepressant drugs and influence treatment outcome. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1996;29(5):180–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Campos-Barros A, Meinhold H, Stula M, et al. The influence of desipramine on thyroid hormone metabolism in rat brain. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1994;268(3):1143–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Baumgartner A, Dubeyoko M, Campos-Barros A, Eravci M, Meinhold H. Subchronic administration of fluoxetine to rats affects triiodothyronine production and deiodination in regions of the cortex and in the limbic forebrain. Brain Research. 1994;635(1-2):68–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Whybrow PC, Prange AJ., Jr. A hypothesis of thyroid-catecholamine-receptor interaction. Its relevance to affective illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1981;38(1):106–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Kicey CA. Catecholamines and depression: a physiological theory of depression. American Journal of Nursing. 1974;74(11):2018–2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Eker SS, Akkaya C, Sarandol A, Cangur S, Sarandol E, Kirli S. Effects of various antidepressants on serum thyroid hormone levels in patients with major depressive disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2008;32(4):955–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Harris B, Fung H, Johns S, et al. Transient post-partum thyroid dysfunction and postnatal depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1989;17(3):243–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Pop VJ, de Rooy HA, Vader HL, et al. Postpartum thyroid dysfunction and depression in an unselected population. New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;324(25):1815–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Harris B, Othman S, Davies JA, et al. Association between postpartum thyroid dysfunction and thyroid antibodies and depression. British Medical Journal. 1992;305(6846):152–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Kuijpens JL, Vader HL, Drexhage HA, Wiersinga WM, Van Son MJ, Pop VJ. Thyroid peroxidase antibodies during gestation are a marker for subsequent depression postpartum. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2001;145(5):579–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Harris B, Oretti R, Lazarus J, et al. Randomised trial of thyroxine to prevent postnatal depression in thyroid-antibody-positive women. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180:327–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Kinuya S, Michigishi T, Tonami N, Aburano T, Tsuji S, Hashimoto T. Reversible cerebral hypoperfusion observed with Tc-99 m HMPAO SPECT in reversible dementia caused by hypothyroidism. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 1999;24(9):666–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Constant EL, De Volder AG, Ivanoiu A, et al. Cerebral blood flow and glucose metabolism in hypothyroidism: a positron emission tomography study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86(8):3864–3870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Forchetti CM, Katsamakis G, Garron DC. Autoimmune thyroiditis and a rapidly progressive dementia: global hypoperfusion on SPECT scanning suggests a possible mechanism. Neurology. 1997;49(2):623–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Krausz Y, Freedman N, Lester H, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow in patients with mild hypothyroidism. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2004;45(10):1712–1715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Nagamachi S, Jinnouchi S, Nishii R, et al. Cerebral blood flow abnormalities induced by transient hypothyroidism after thyroidectomy: analysis by Tc-99 m-HMPAO and SPM96. Annals of Nuclear Medicine. 2004;18(6):469–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Krausz Y, Freedman N, Lester H, et al. Brain SPECT study of common ground between hypothyroidism and depression. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;10(1):99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. Drevets WC. Neuroimaging studies of mood disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48(8):813–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Mayberg HS. Modulating dysfunctional limbic-cortical circuits in depression: towards development of brain-based algorithms for diagnosis and optimised treatment. British Medical Bulletin. 2003;65:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Brody AL, Saxena S, Stoessel P, et al. Regional brain metabolic changes in patients with major depression treated with either paroxetine or interpersonal therapy: preliminary findings. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(7):631–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Goldapple K, Segal Z, Garson C, et al. Modulation of cortical-limbic pathways in major depression: treatment-specific effects of cognitive behavior therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(1):34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Martin SD, Martin E, Rai SS, Richardson MA, Royall R. Brain blood flow changes in depressed patients treated with interpersonal psychotherapy or venlafaxine hydrochloride: preliminary findings. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(7):641–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Are Thyroid Conditions and Depression Linked?

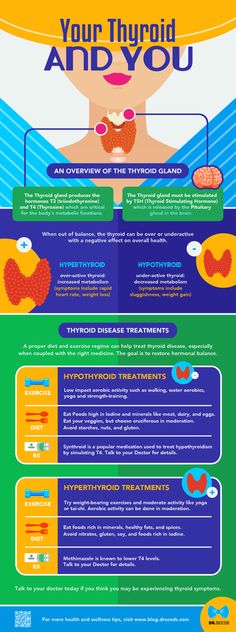

Your thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland at the front of your throat that secretes hormones. These hormones regulate your metabolism, energy levels, and other vital functions in your body.

More than 12 percent of Americans will develop a thyroid condition in their lifetime. But as many as 60 percent of those who have a thyroid condition aren’t aware of it.

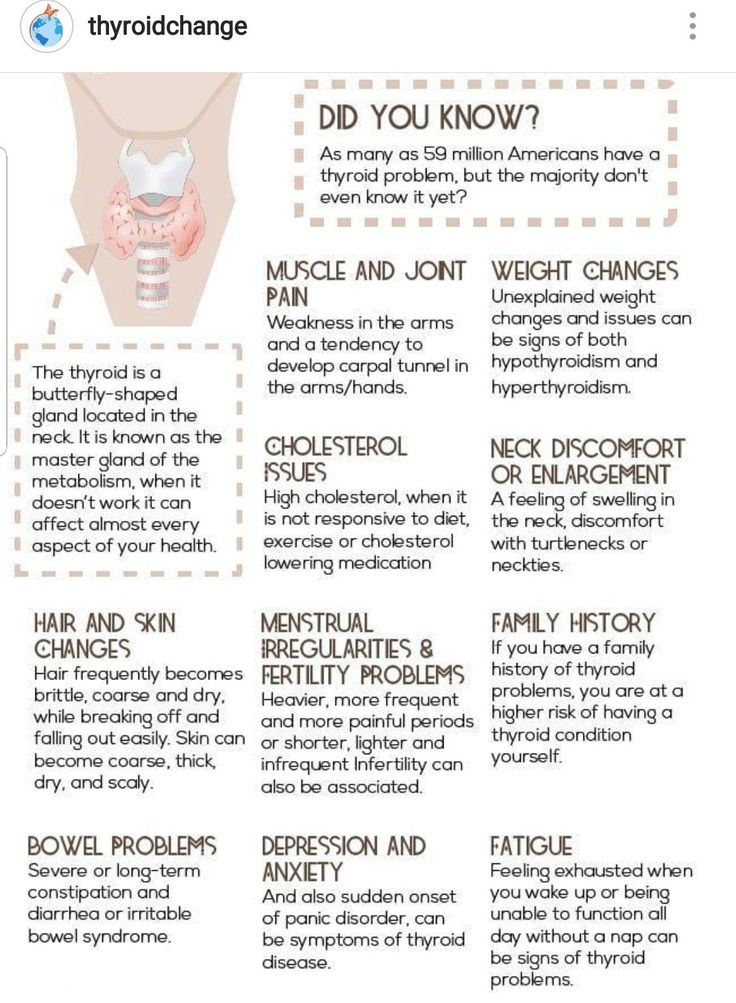

Thyroid disease has some symptoms in common with certain mental health conditions. This is especially true for depression and anxiety. Sometimes thyroid conditions are misdiagnosed as these mental health conditions. This can leave you with symptoms that may improve but a disease that still needs to be treated.

Let’s take a closer look at the links among thyroid conditions, depression, and anxiety.

Researchers have known for a long time that people who have thyroid conditions are more likely to experience depression and vice versa. But with the rising diagnosis rates of anxiety and depression, there’s an urgency to revisit the issue.

Hyperthyroidism is a condition characterized by an overactive thyroid. A review of the literature estimates that up to 60 percent of people who have hyperthyroidism also have clinical anxiety. Depression occurs in up to 69 percent of people diagnosed with hyperthyroidism.

Hyperthyroidism is connected in particular to mood disorders and bipolar depression. But the research is conflicting as to how strong this connection is. One 2007 study revealed that thyroiditis is likely connected to having a genetic predisposition of bipolar disorder.

On top of that, lithium can aggravate or trigger hyperthyroidism. It’s a prevalent treatment for bipolar depression.

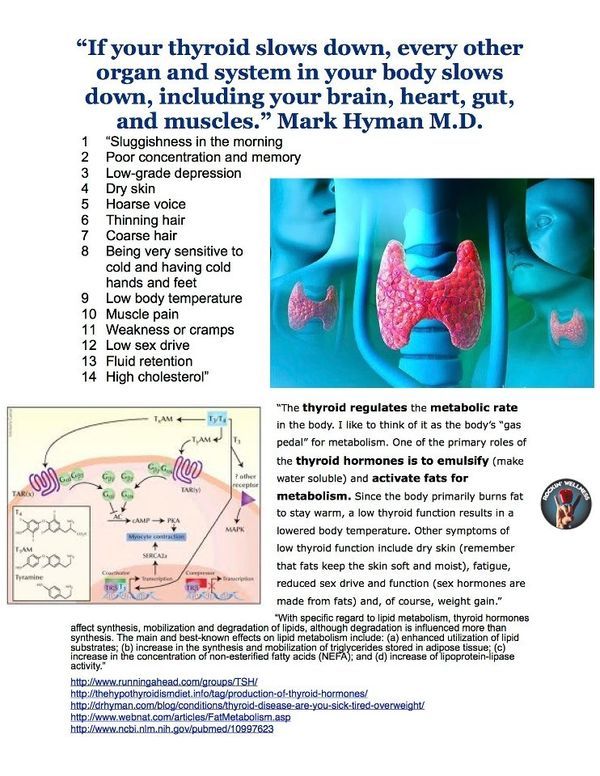

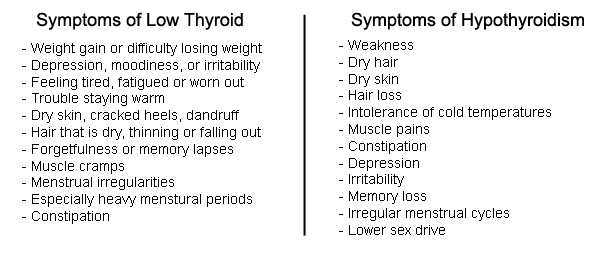

Hypothyroidism is a condition characterized by a “sluggish” or underactive thyroid. It’s linked specifically to depression in some literature. The deficiency of thyroid hormones in your central nervous system can cause fatigue, weight gain, and a lack of energy. These are all symptoms of clinical depression.

If you have hyperthyroidism, your symptoms may have a lot in common with clinical anxiety and bipolar depression. These symptoms include:

- insomnia

- anxiety

- elevated heart rate

- high blood pressure

- mood swings

- irritability

Hypothyroidism symptoms, on the other hand, have a lot in common with clinical depression and what doctors call “cognitive dysfunction.” This is memory loss and difficulty organizing your thoughts. These symptoms include:

- bloating

- weight gain

- memory loss

- difficulty processing information

- fatigue

The overlap in thyroid conditions and mood disorders can result in a misdiagnosis. And if you’ve been diagnosed with a mental health condition but have an underlying thyroid condition, too, your doctors might miss it.

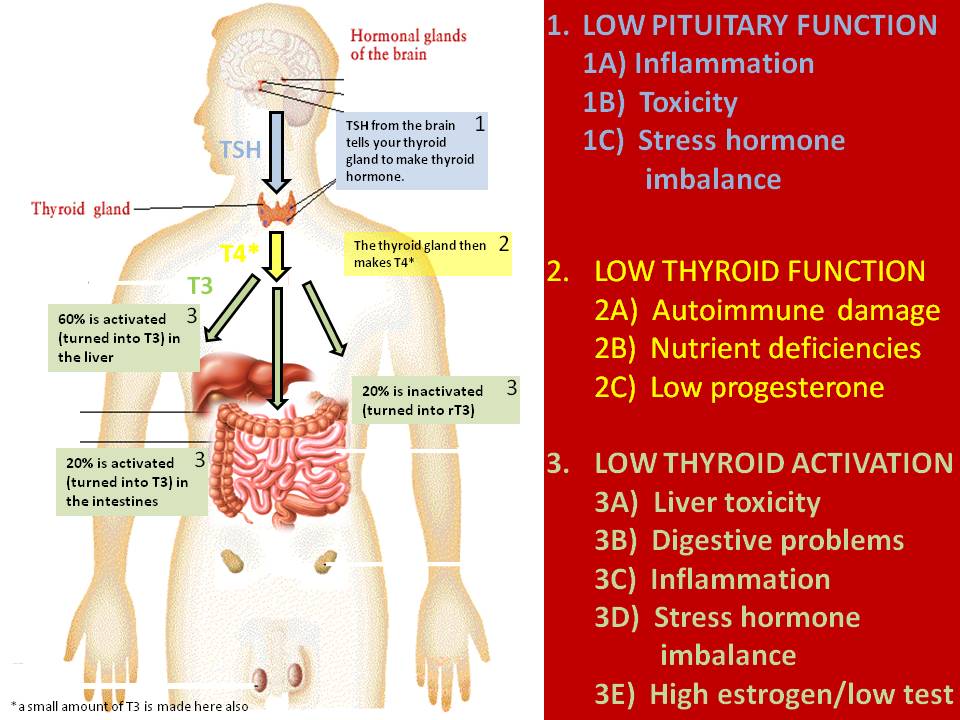

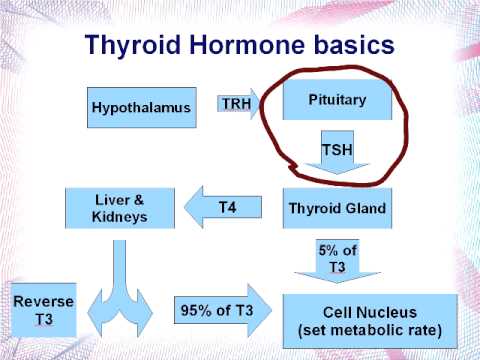

Sometimes a blood panel that’s testing your thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) can miss a thyroid condition. The T3 and T4 hormone levels are specific indicators that can reveal a thyroid condition that other blood tests overlook.

Hormone supplementation for a thyroid condition can be related to depression. Thyroid hormone replacement aims to bring your body back to its normal hormone levels if you have hypothyroidism. But this kind of treatment can interfere with medications for depression.

Medication for depression can be what’s decreasing or impacting your thyroid function. There’s a long list of medications that can have this effect. Lithium, a popular treatment for bipolar depression, can trigger symptoms of hyperthyroidism.

If you’re having symptoms of depression, you may be wondering if there is a connection to your thyroid. Even if your TSH levels have tested as normal, it’s possible that there’s more to the story of how your thyroid is functioning.

You can bring up the possibility of a thyroid condition to your general practitioner, family doctor, or a mental health professional. Ask specifically for the T3 and T4 hormone level screening to see if those levels are where they should be.

What you should never do is discontinue medication for a mental health condition without speaking to a physician.

If you’re looking for alternative treatments and new ways to address your depression, make a plan with your doctor to gradually switch dosages of your medication or incorporate supplements into your routine.

Depression, fatigue, overweight? Check your thyroid.

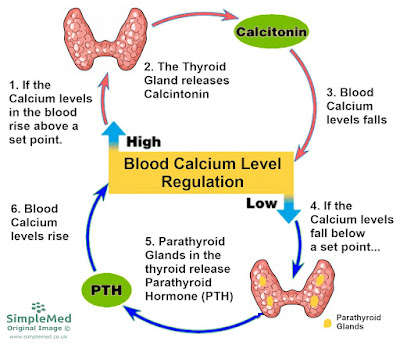

The thyroid gland is a very small organ located in our throat area, under the larynx. Normally, it weighs no more than 20 grams, consists of two lobes and an isthmus. The thyroid gland synthesizes thyroid hormones; T3 - triiodothyronine, T4 - thyroxine and calciotonin (parathyroid hormone) - regulating calcium levels.

The first two hormones are responsible for the physical, mental state of the body, seriously affect the immune system, stimulating the production of T-cells. With the most active participation of these hormones, almost all metabolic processes in the body are performed, a constant body temperature is maintained, and energy is produced. Will an orchestra play without a conductor? nine0003

It will probably be, but we won't hear a beautiful, well-coordinated melody. So it is with the thyroid gland, it regulates all the endocrine glands, affects the metabolism, determines our well-being on a global scale, so to speak. Accordingly, if the conductor (our thyroid gland) is ill, can hardly stand on his feet and impulsively pulls his arms, the symphony will not work. Here it will not be up to the game, if only to somehow survive. And the body, exhausted and unbalanced, endures ... until the first serious illness, until the first weakness ...

It's not just sex hormones that affect how you look and feel. Among the most influential are also the hormones produced by the thyroid gland.

Too low thyroid activity and you feel like an amoeba. Yes, hypothyroidism makes you feel like you just want to lie on the couch with a bag of chips all day. Everything works slower, including your heart, intestines, and your brain. A general drop in brain activity in hypothyroidism leads to depression, cognitive impairment, anxiety, and mental fog. nine0003

The thyroid gland controls the production of many neurotransmitters. Among them are serotonin, dopamine, adrenaline and norepinephrine. An underactive thyroid can lead to a compensatory increase in adrenaline (produced by the adrenal glands), which makes you feel constantly tense, as well as cortisol, another stress hormone. Thus, you feel tired, tense and stressed at the same time.

Experts conservatively estimate that one third of all depression is directly related to thyroid imbalance. More than 80% of people with mild hypothyroidism have poor memory. nine0003

Symptoms of underactive thyroid gland:

- Feeling chilly

- Weight gain

- Constipation

- Fatigue

- High cholesterol

- High blood pressure

- Dry, thinning hair or lack of hair, especially on the eyebrows, where one third of the hairline is often missing

- Dry skin

- Dry eye syndrome

- Thin, broken or peeling nails

- Irregular menses

- Endometriosis

- Infertility

- Miscarriage

- Severe menopause

Even if your thyroid is slightly underactive, you may still have symptoms of what is known as subclinical hypothyroidism. If you are chronically fatigued, overweight, dry skin, dizzy, depressed, constantly cold, and if your body temperature is consistently below 36.6 degrees, then you may have an underactive thyroid gland. nine0003

An overactive thyroid causes hyperthyroidism. In this state, everything in the body is working too fast, including the heart, intestines, and digestion, as if you are rushing forward at crazy speed. A person feels nervous and nervous, as after large doses of caffeine. If you suffer from insomnia, anxiety, irritability, chaotic thinking, rapid heart rate, shortness of breath, weight loss despite an increased appetite, unreasonable fever, then you may have an overactive thyroid gland. In extreme cases, other characteristic signs appear: goiter (an outgrowth on the thyroid gland), significant weight loss, bulging eyes. nine0003

What does the thyroid gland suffer from?

The thyroid gland is a small, butterfly-shaped gland located in the lower part of the neck. When the doctor runs his hands along the base of the throat, he checks for an obvious enlargement of your thyroid gland. But without a blood test, it is impossible to say exactly what is happening there. And it may take some time to optimize the thyroid gland.

The main thyroid-related hormones - TSH, T3, T4 - must be balanced. Tens of millions of people around the world (5-25% of the world's population) are thought to have thyroid problems. In their book Thyroid Mental Power, Richard and Carily Shames write that “Over the past 40 years, we have witnessed a significant increase in the number of synthetic chemicals that lead to hormonal disorders. These substances penetrate our air, food and water... the most sensitive human tissue turned out to be the thyroid gland.” nine0003

Most thyroid problems are autoimmune, where the body attacks itself. This may be due to environmental toxins present in the body or an allergy to the food we eat or something in the air we breathe. It is suspected that the recent dramatic increase in hypothyroidism may be due to the fact that the toxins we ingest interfere with the peripheral conversion of T4 to T3.

Thyroid depressant factors:

- Too much stress and cortisol

- Selenium deficiency

- Protein deficiency, excess sugar

- Chronic diseases

- Liver or kidney disorders

- Cadmium, mercury, lead poisoning

- Herbicides, pesticides

- Birth control pills, excessive estrogen production

Problems with the thyroid gland - after the birth of a child.

Thyroid problems can occur at any time in a woman's life. But a particularly vulnerable period is the birth of a child. During pregnancy, the immune system relaxes somewhat so that immune cells and antibodies do not reject the placenta, with which the baby feeds. This is why many women with thyroid problems believe that pregnancy is the best state of their lives. nine0003

However, nine months later, the situation changes. The baby is born, the placenta is gone, and the immune system functions that were shut down to prevent early placental rejection are now turning on dramatically. It is well known that thyroid disorders usually return within 6 months after childbirth. According to researchers from Charles University in Prague, in 35% of women who have antibodies to their own thyroid gland, 2 years after the birth of a child, the thyroid gland begins to malfunction again. nine0003

Having a thyroid problem when you're struggling to cope with a 2 year old is a disaster. Studies indicate that about 70% of women who suffer from hypothyroidism in the postpartum period become careless and make more mistakes when caring for their children.

Thyroid problems are one of the main causes of postpartum depression and anxiety. According to one study, 80-90% of cases of postpartum depression are associated with thyroid disorders. And without effective treatment, it is impossible to recover. nine0003

The post-pregnancy period is not the only vulnerable period in this regard. It has been estimated that one in four postmenopausal women has a thyroid imbalance.

How to check the thyroid gland?

You can check your thyroid gland with a blood test. Do not settle for TSH (pituitary thyroid stimulating hormone) analysis alone. Its levels may be normal even when you have undiagnosed thyroid problems.

Insist that the doctor check the following:

- TSH (According to the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, values above 3.0 are abnormal and need further testing)

- Free T3 (active)

- Free T4 (inactive)

Thyroid antibodies: thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO Ab) and thyroglobulin antibodies (TG Ab).

Liver function test. The fact is that 95% of T4 is activated in the liver, so the condition of the liver should be taken into account. nine0003

Ferritin level. Ferritin transports active T3 into cells. It should be above 90.

These tests may be helpful, but you still need to be diagnosed by a doctor. If you have thyroid problems, they can be effectively treated with a range of medications. Your doctor should regularly check your thyroid hormone levels to make sure you are not taking too much or too little of your medication.

Sad image What disease can cause depression and how to avoid it: Lenta.ru

According to WHO, about 300 million cases of depression have been identified among the entire population of the planet, while it is noted that women suffer from it many times more often. It is worth emphasizing that this disease has a seasonality, and it is during the autumn period that the likelihood of falling into depression increases. Lenta.ru, with the support of Berlin-Chemie/A. Menarini, talks about one of the reasons why this disorder occurs - and how to deal with it.

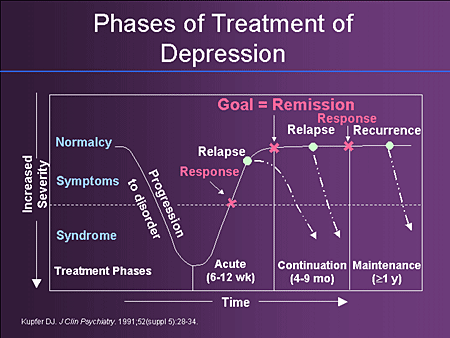

Failure occurs in everyone's life. Bad weather, interpersonal conflicts, problems at work, and more can make a person feel overwhelmed and overwhelmed, but being overwhelmed by domestic problems rarely lasts long. If the “bad period” is observed for a sufficiently long time, then the presence of depression in a person cannot be ruled out. But it can be one of the symptoms of another disease. nine0003

There are different types of depression:

- reactive depression. Occurs under the influence of psychotraumatic factors on a person;

- endogenous depression. Its source is unknown, but most likely it is a violation of the biochemical mechanisms of the brain;

- somatogenic depression. It is observed when a person has any underlying disease.

An example of such a pathological condition of the body that can lead to the formation of somatogenic depression is hypothyroidism, lack of thyroid hormones. nine0003

Hypothyroidism is a worldwide disease that is several times more common in women than in men.

Depression and thyroid gland

Due to the fact that thyroid hormones regulate the basic metabolism of the body, their deficiency can lead to disruption of all systems, including disorders in the sphere of emotions. There may be a sharp change in mood, a feeling of melancholy and sadness, up to panic and severe depressive states.

Hypothyroidism has been confirmed to cause depression, but the exact cause is not yet fully understood. There are various theories in this regard: the speed of blood flow in the vessels of the brain slows down, carbohydrate metabolism is disturbed, the work of neurotransmitters changes. All this indicates that the nervous system is very susceptible to a lack of thyroid hormones. nine0003

Causes of hypothyroidism

Most often, changes in the functioning of the thyroid gland are observed in the presence of autoimmune thyroiditis - an inflammatory disease of the thyroid gland. With the development of this condition, the cells of the immune system perceive the thyroid tissue as foreign and begin to "attack" it. As a result, its work is disrupted and the production of hormones decreases.

During pregnancy, a woman's body experiences hormonal "spikes" that can lead to thyroid damage, hypothyroidism, and a lack of thyroid hormones. Conducted surgical interventions on the thyroid gland can also be the reasons for the decrease in hormone production. nine0003

What to do if depression persists

When treating depression, it is first necessary to find out its source: whether it is a consequence of some other disease, that is, whether it is somatogenic depression. Statistically, most of all somatogenic depressions are caused by hypofunction of the thyroid gland. It is logical that the possibility of this condition must be excluded in the first place. To confirm hypothyroidism, you need only one study - a blood test for the content of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).