Part of the brain responsible for emotion

The Anatomy of Emotions

iStock.com/cglade

In the 1970s, anthropologist Paul Ekman proposed that humans experienced six basic emotions: anger, fear, surprise, disgust, joy, and sadness. Since then, scientists have disputed the exact number of human emotions — some researchers maintain there are only four, while others count as many as 27. And, scientists also debate whether they are universal to all human cultures and whether we’re born with them or learn them through experience. Even the definition of emotion is a topic of controversy. One thing is clear though — emotions arise from activity in distinct regions of the brain.

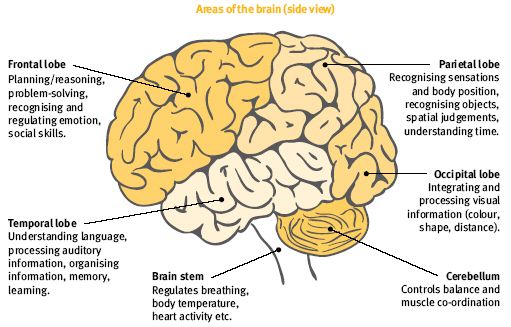

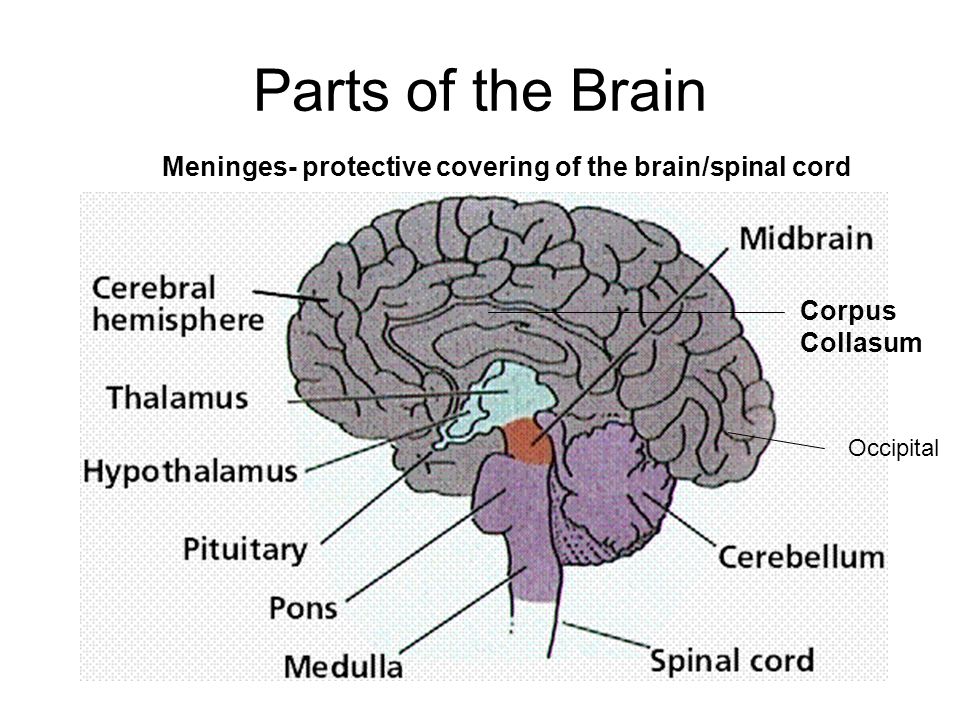

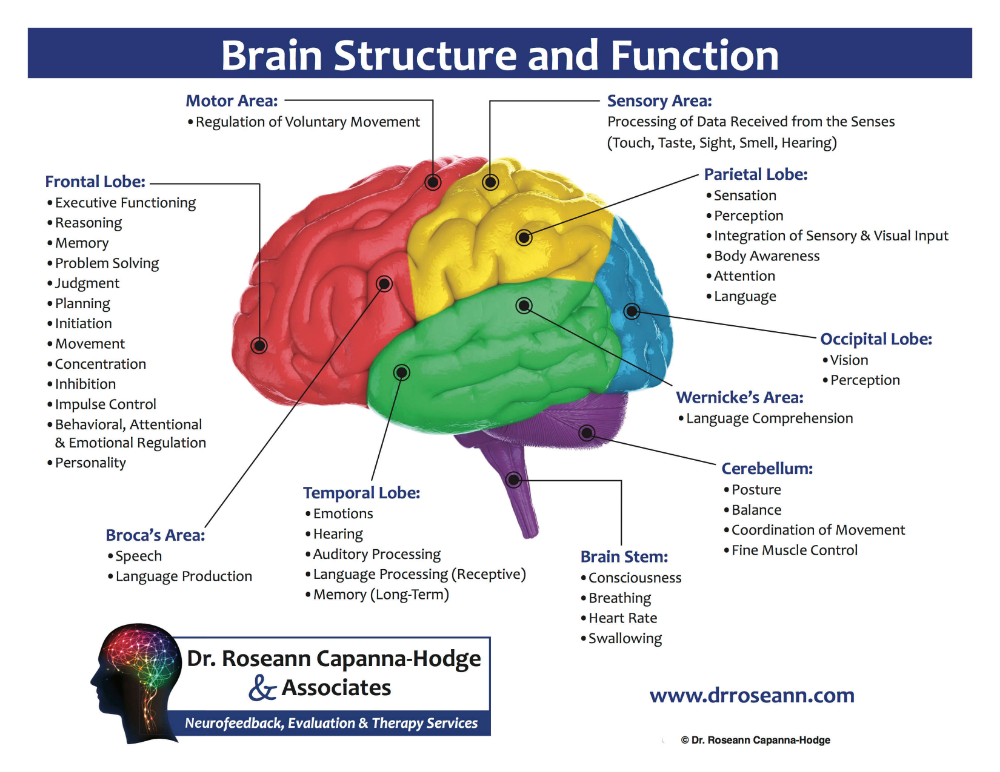

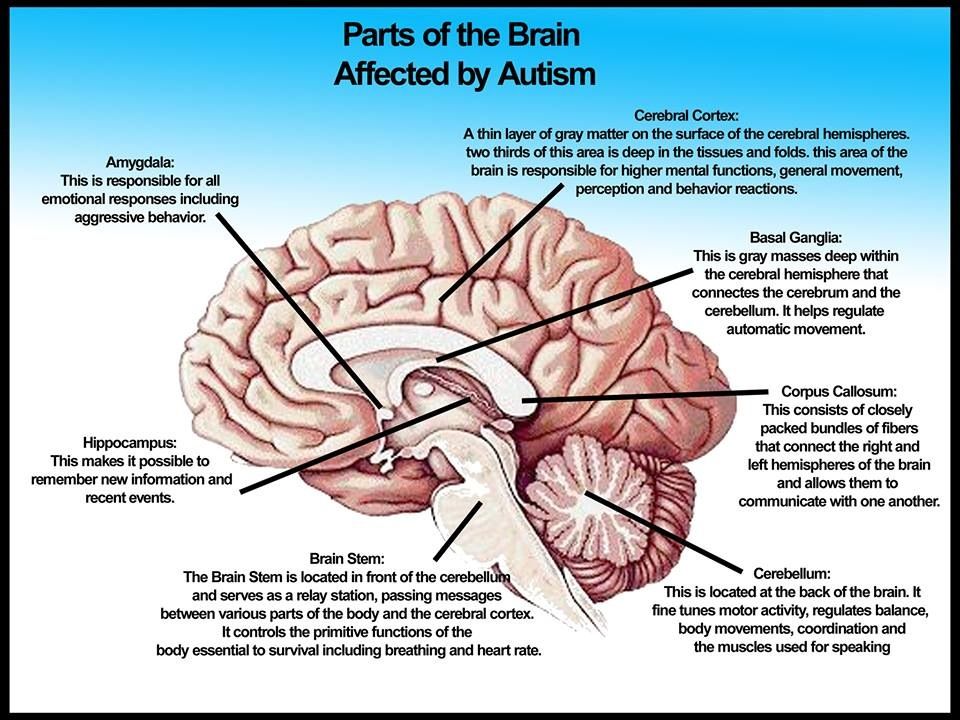

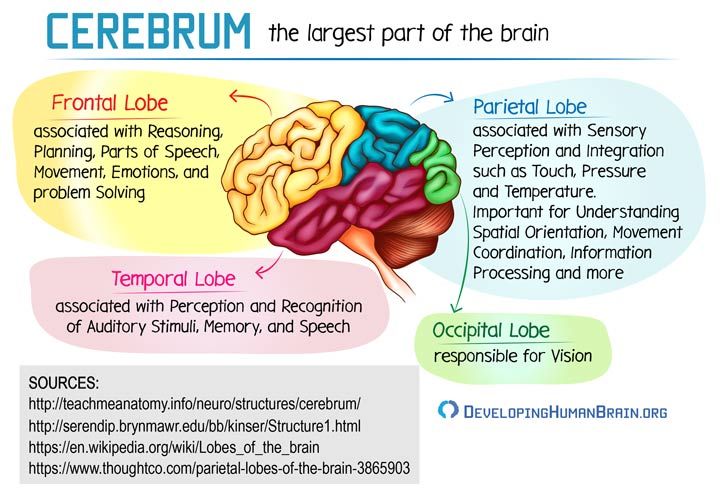

Three brain structures appear most closely linked with emotions: the amygdala, the insula or insular cortex, and a structure in the midbrain called the periaqueductal gray.

Explore the Amygdala 3D BRAIN

A paired, almond-shaped structure deep within the brain, the amygdala integrates emotions, emotional behavior, and motivation. It interprets fear, helps distinguish friends from foes, and identifies social rewards and how to attain them. The amygdala is also important for a type of learning called classical conditioning. Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov first described classical conditioning, where, through repeated exposure, a stimulus elicits a particular response, in his studies of digestion in dogs. The dogs salivated when a lab technician brought them food. Over time, Pavlov noted the dogs also began to salivate at the mere sight of the technician, even if he was empty-handed.

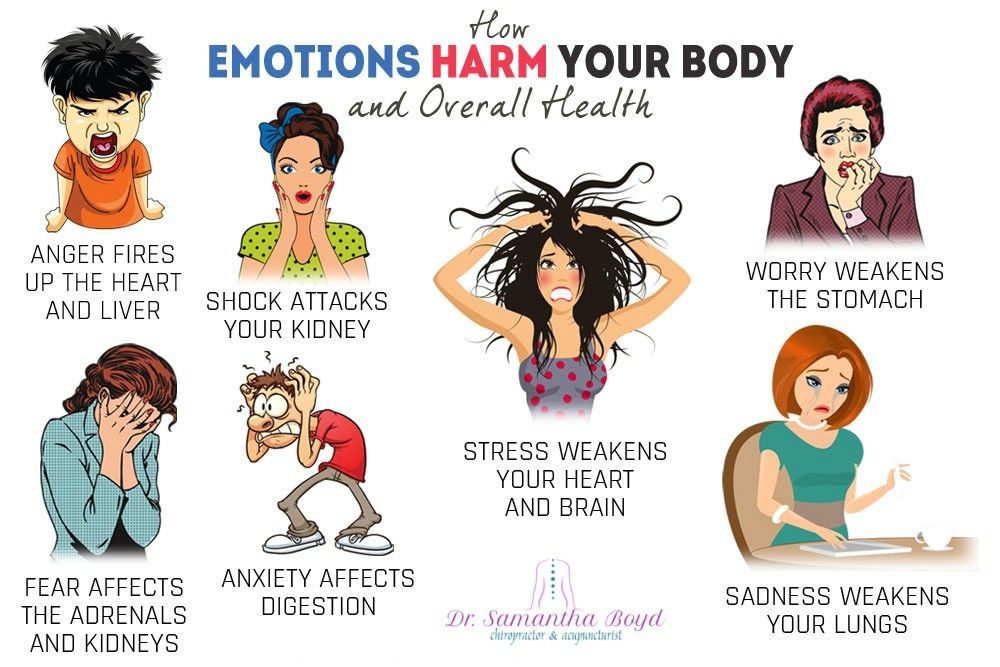

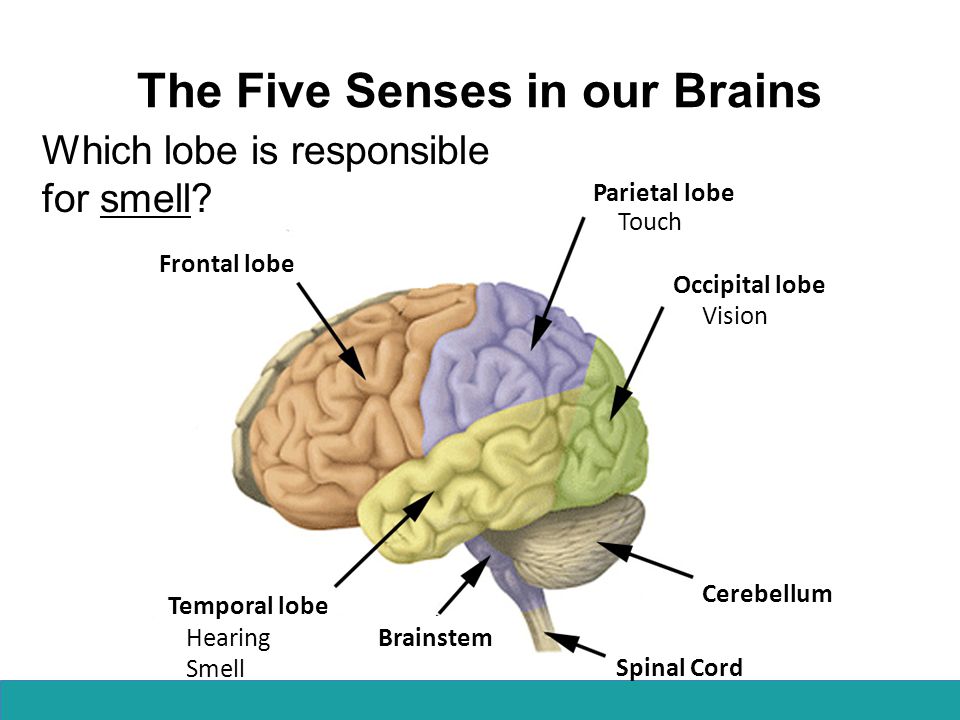

The insula is the source of disgust — a strong negative reaction to an unpleasant odor, for instance. The experience of disgust may protect you from ingesting poison or spoiled food. Studies using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have found the insula lights up with activity when someone feels or anticipates pain. Neuroscientists think the insula receives a status report about the body’s physiological state and generates subjective feelings about it thus linking internal states, feelings, and conscious actions.

The periaqueductal gray, located in the brainstem, has also been implicated in pain perception. It contains receptors for pain-reducing compounds like morphine and oxycodone, and can help quell activity in pain-sensing nerves — it might be part of the reason you can sometimes distract yourself from pain so you don’t feel it as acutely. The periaqueductal gray is also involved in defensive and reproductive behaviors, maternal attachment, and anxiety.

While emotions are intangible and hard to describe — even for scientists — they serve important purposes, helping us learn, initiate actions, and survive.

Adapted from the 8th edition of Brain Facts by Alexis Wnuk

About the Author

Content Provided By

References

Craig ADB. 2009. How do you feel--now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 10(1):59–70. doi:10.1038/nrn2555.

Linnman C, Moulton EA, Barmettler G, Becerra L, Borsook D. 2012. Neuroimaging of the Periaqueductal Gray: State of the Field. Neuroimage. 60(1):505–522. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.095.

2012. Neuroimaging of the Periaqueductal Gray: State of the Field. Neuroimage. 60(1):505–522. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.095.

Related Topics Emotions Anatomy Emotions, Stress & Anxiety Thinking, Sensing & Behaving Brain Anatomy & Function

What Part of the Brain Controls Emotions? Fear, Happiness, Anger, Love

Overview

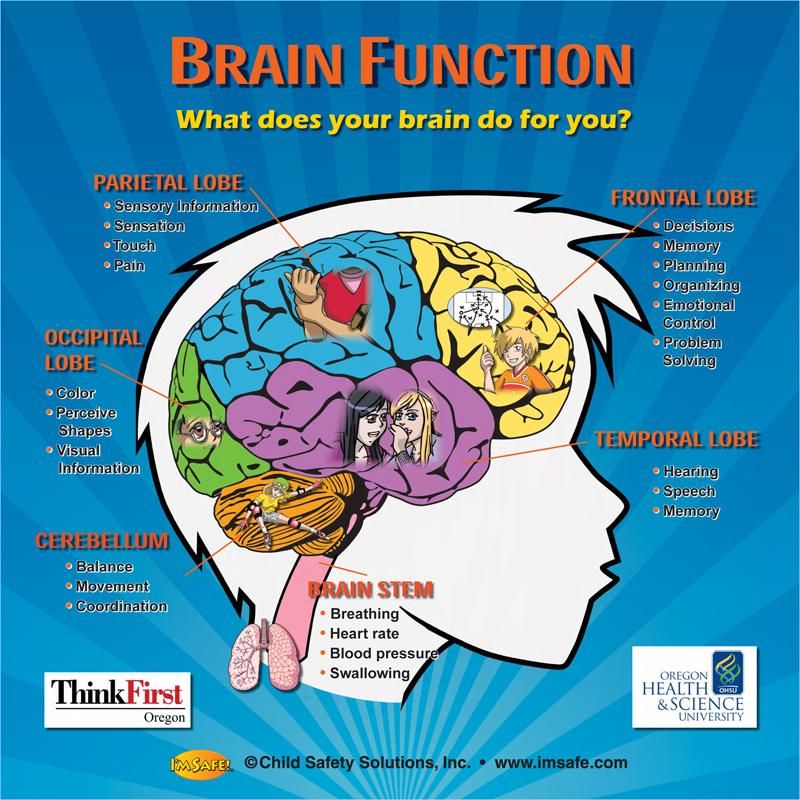

The brain is a very complex organ. It controls and coordinates everything from the movement of your fingers to your heart rate. The brain also plays a crucial role in how you control and process your emotions.

Experts still have a lot of questions about the brain’s role in a range of emotions, but they’ve pinpointed the origins of some common ones, including fear, anger, happiness, and love.

Read on to learn more about what part of the brain controls emotions.

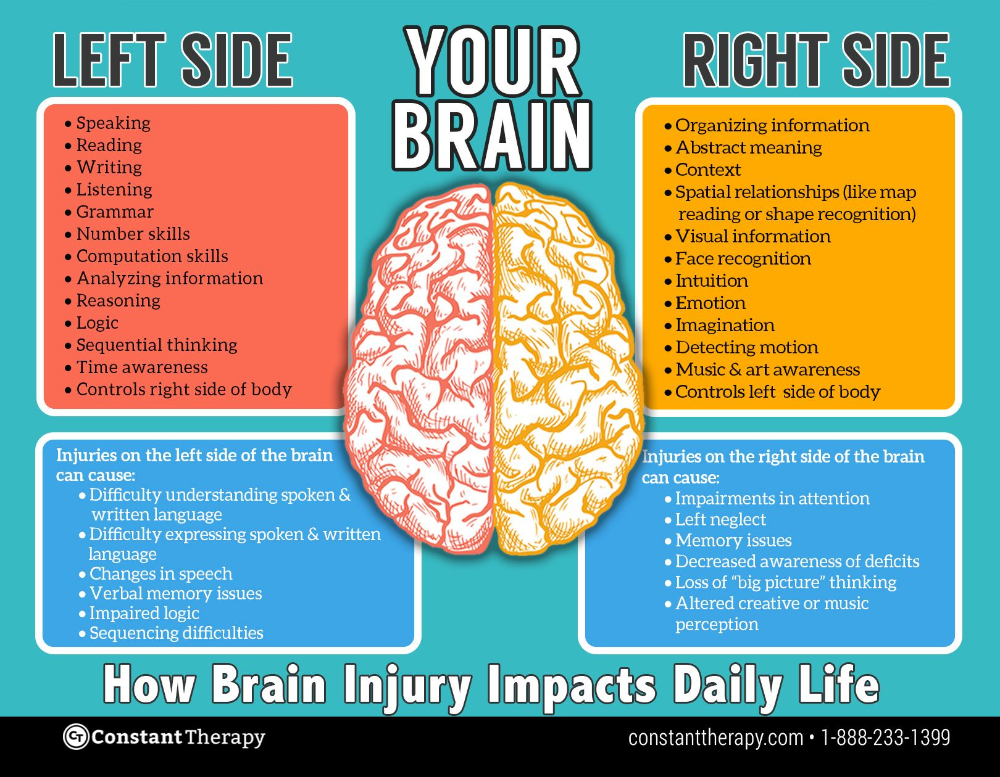

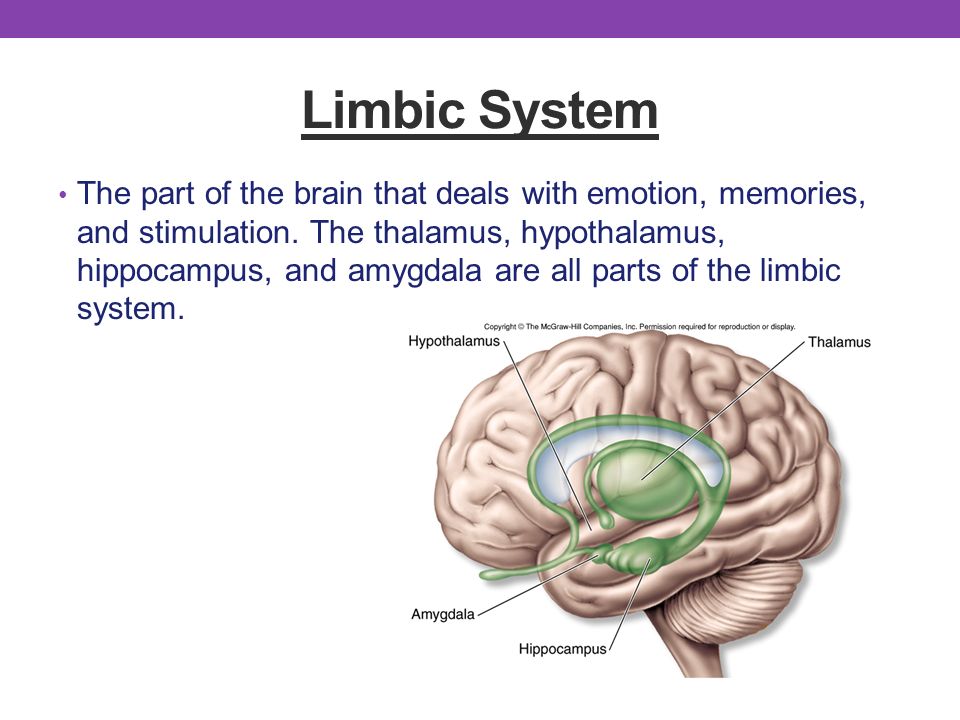

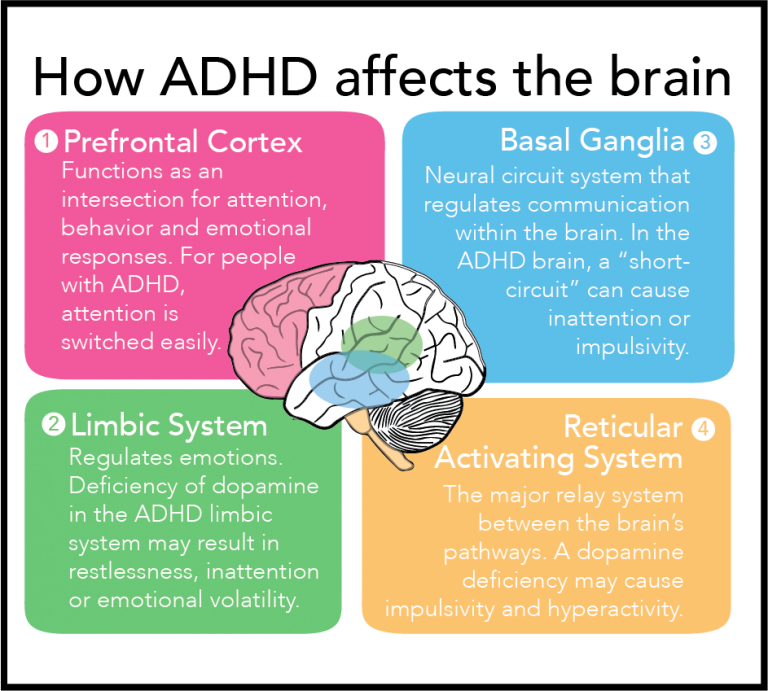

The limbic system is a group of interconnected structures located deep within the brain. It’s the part of the brain that’s responsible for behavioral and emotional responses.

Scientists haven’t reached an agreement about the full list of structures that make up the limbic system, but the following structures are generally accepted as part of the group:

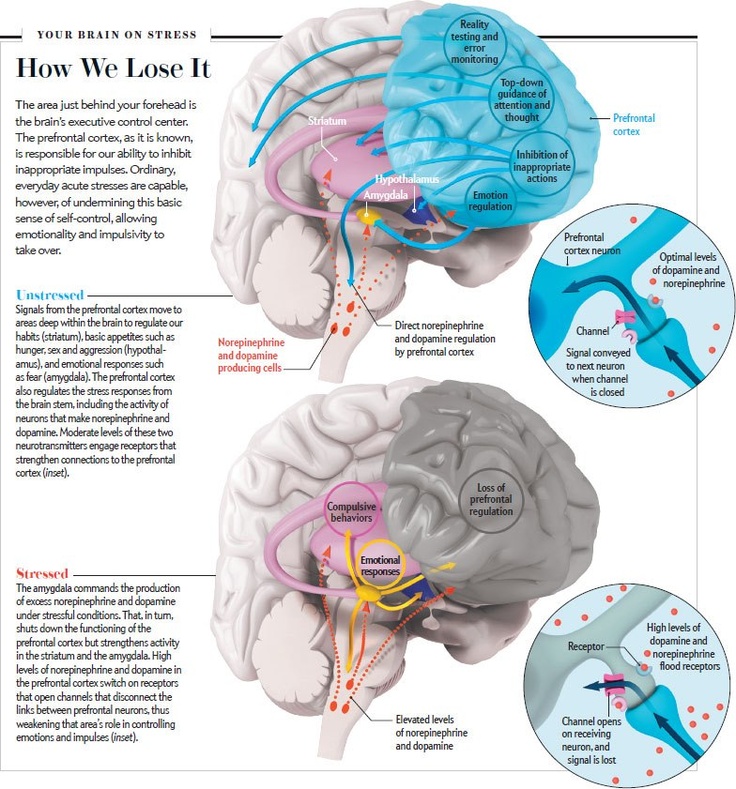

- Hypothalamus. In addition to controlling emotional responses, the hypothalamus is also involved in sexual responses, hormone release, and regulating body temperature.

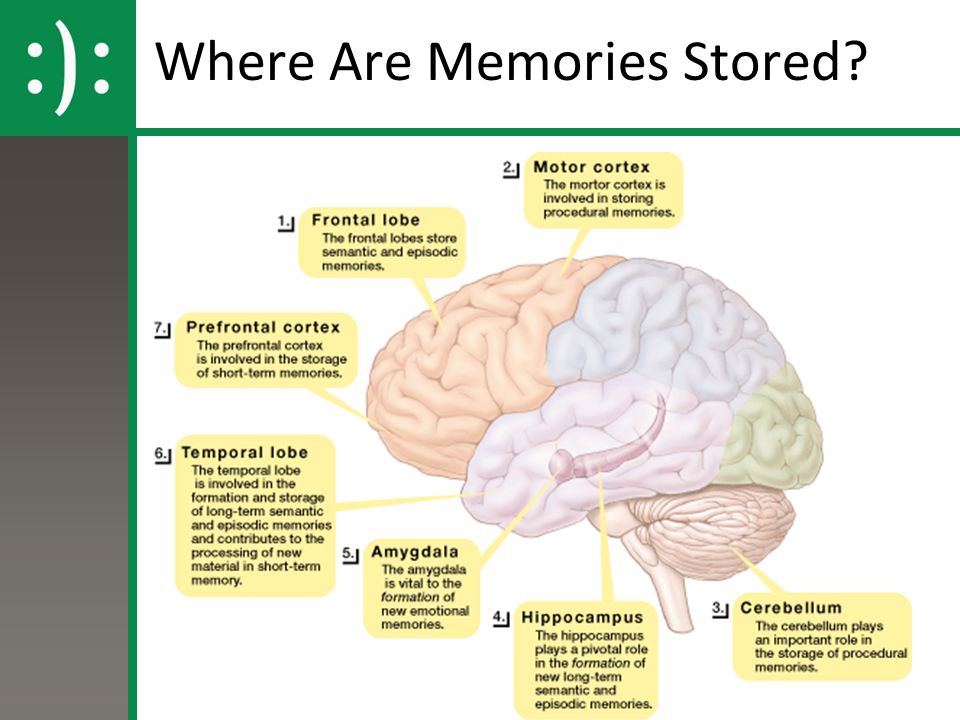

- Hippocampus. The hippocampus helps preserve and retrieve memories. It also plays a role in how you understand the spatial dimensions of your environment.

- Amygdala. The amygdala helps coordinate responses to things in your environment, especially those that trigger an emotional response. This structure plays an important role in fear and anger.

- Limbic cortex. This part contains two structures, the cingulate gyrus and the parahippocampal gyrus. Together, they impact mood, motivation, and judgement.

From a biological standpoint, fear is a very important emotion. It helps you respond appropriately to threatening situations that could harm you.

This response is generated by stimulation of the amygdala, followed by the hypothalamus. This is why some people with brain damage affecting their amygdala don’t always respond appropriately to dangerous scenarios.

When the amygdala stimulates the hypothalamus, it initiates the fight-or-flight response. The hypothalamus sends signals to the adrenal glands to produce hormones, such as adrenaline and cortisol.

As these hormones enter the bloodstream, you might notice some physical changes, such as an increase in:

- heart rate

- breathing rate

- blood sugar

- perspiration

In addition to initiating the fight-or-flight response, the amygdala also plays a role in fear learning. This refers to the process by which you develop an association between certain situations and feelings of fear.

This refers to the process by which you develop an association between certain situations and feelings of fear.

Much like fear, anger is a response to threats or stressors in your environment. When you’re in a situation that seems dangerous and you can’t escape, you’ll likely respond with anger or aggression. You can think of the anger response and the fight as part of the fight-or-flight response.

Frustration, such as facing roadblocks while trying to achieve a goal, can also trigger the anger response.

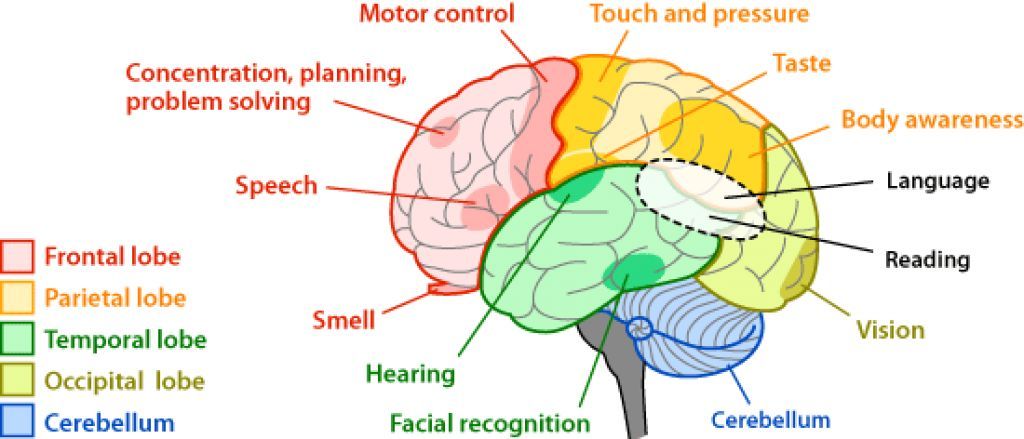

Anger starts with the amygdala stimulating the hypothalamus, much like in the fear response. In addition, parts of the prefrontal cortex may also play a role in anger. People with damage to this area often have trouble controlling their emotions, especially anger and aggression.

Parts of the prefrontal cortex of the brain may also contribute to the regulation of an anger response. People with damage to this area of the brain sometimes have difficulty controlling their emotions, particularly anger and aggression.

Happiness refers to an overall state of well-being or satisfaction. When you feel happy, you generally have positive thoughts and feelings.

Imaging studies suggest that the happiness response originates partly in the limbic cortex. Another area called the precuneus also plays a role. The precuneus is involved in retrieving memories, maintaining your sense of self, and focusing your attention as you move about your environment.

A 2015 study found that people with larger gray matter volume in their right precuneus reported being happier. Experts think the precuneus processes certain information and converts it into feelings of happiness. For example, imagine you’ve spent a wonderful night out with someone you care about. Going forward, when you recall this experience and others like it, you may experience a feeling of happiness.

It may sound strange, but the beginnings of romantic love are associated with the stress response triggered by your hypothalamus. It makes more sense when you think about the nervous excitement or anxiety you feel while falling for someone.

As these feelings grow, the hypothalamus triggers release of other hormones, such as dopamine, oxytocin, and vasopressin.

Dopamine is associated with your body’s reward system. This helps make love a desirable feeling.

A small 2005 study showed participants a picture of someone they were romantically in love with. Then, they showed them a photo of an acquaintance. When shown a picture of someone they loved, the participants had increased activity in parts of the brain that are rich in dopamine.

Oxytocin is often referred to as the “love hormone.” This is largely because it increases when you hug someone or have an orgasm. It’s produced in the hypothalamus and released through your pituitary gland. It’s associated with social bonding as well. This is important for trust and building a relationship. It can also promote a feeling of calmness and contentment.

Vasopressin is similarly produced in your hypothalamus and released by your pituitary gland. It’s also involved in social bonding with a partner.

The brain is a complex organ that researchers are still trying to decode. But experts have identified the limbic system as one of the main parts of the brain that controls basic emotions.

As technology evolves and scientists get a better glimpse into the human mind, we’ll likely learn more about the origins of more complex emotions.

The brain region responsible for the emotional component of moral and ethical assessments has been identified

American psychologists have found that patients with bilateral damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex are guided only by reason when solving complex moral dilemmas, while in healthy people emotions play an important role. In imaginary situations, the studied patients do not see the difference between a murder committed in absentia (for example, by pressing a button) and one's own hand, while the difference seems huge to healthy people. Perfectly distinguishing good and evil on a conscious level, such patients are not capable of empathy and never feel guilty. nine0004

nine0004

Eric Kandel, who received the Nobel Prize in 2000 for his research on the molecular mechanisms of memory, became interested in psychoanalysis in his youth and became a neuroscientist in the hope of finding out in which parts of the brain the Freudian "ego", "superego" and "id" are located (what to him, however, failed). Half a century ago, such dreams seemed naive, but today neuroscientists have come close to revealing the biological foundations of the most complex aspects of the human psyche.

Article by American psychologists and neuroscientists, published in the latest issue of the journal Nature , reports an important success in the study of the material nature of morality and morality, that is, that aspect of the psyche that Sigmund Freud called the "superego" (super-self). Freud believed that the superego functions largely unconsciously, and as it turns out, he was quite right.

It was traditionally believed that morality and morality stem from a sound awareness of the norms of behavior accepted in society, from the concepts of good and evil learned in childhood. However, in recent years, a number of facts have been obtained that indicate that moral assessments are not only rational, but also emotional in nature. For example, various disturbances in the emotional sphere are often accompanied by changes in ideas about morality; when solving problems related to moral assessments, the parts of the brain responsible for emotions are excited; Finally, behavioral experiments show that people's attitudes towards various moral dilemmas are highly dependent on their emotional state. However, so far no one has been able to experimentally show that some area of the brain specializing in emotions is really necessary for the formation of "normal" judgments about morality. nine0005

However, in recent years, a number of facts have been obtained that indicate that moral assessments are not only rational, but also emotional in nature. For example, various disturbances in the emotional sphere are often accompanied by changes in ideas about morality; when solving problems related to moral assessments, the parts of the brain responsible for emotions are excited; Finally, behavioral experiments show that people's attitudes towards various moral dilemmas are highly dependent on their emotional state. However, so far no one has been able to experimentally show that some area of the brain specializing in emotions is really necessary for the formation of "normal" judgments about morality. nine0005

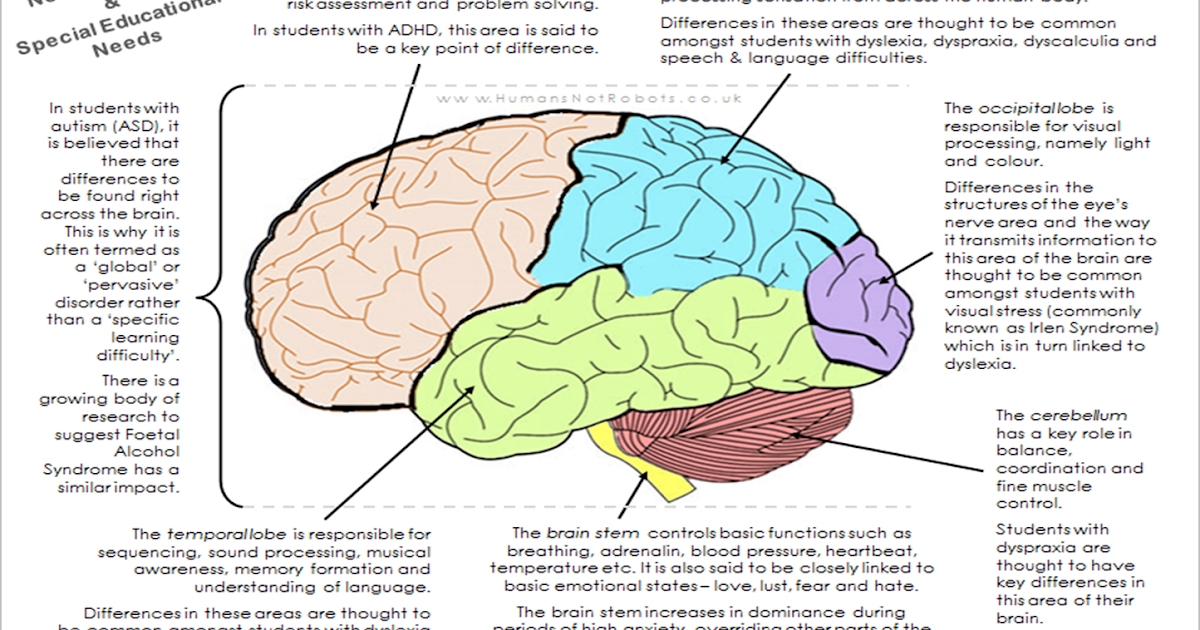

The authors of the article studied six patients who, in adulthood, received bilateral damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPC). It is known that this part of the brain carries out an emotional assessment of sensory information entering the brain, especially that which has a "social" coloring. VMPK also regulates the body's emotional responses (eg, increased heart rate when seeing a photograph depicting someone's suffering).

VMPK also regulates the body's emotional responses (eg, increased heart rate when seeing a photograph depicting someone's suffering).

Patients were carefully examined by qualified psychologists and neuropathologists, and the examination was carried out "blindly": the doctors did not know what scientific ideas would be tested on the basis of their conclusions. It turned out that all six had a normal level of intelligence (IQ from 80 to 143), memory and emotional background (that is, no pathological mood swings were detected). However, their ability to empathize was sharply reduced. For example, they almost did not react (at the physiological level) to "emotionally loaded" pictures depicting various catastrophes, crippled people, etc. Moreover, all six patients, as it turned out, were practically unable to feel embarrassment, shame, and guilt. At the same time, on a conscious level, they perfectly understand what is good and what is bad, that is, the accepted social and moral norms of behavior are well known to them. nine0005

nine0005

Then the subjects were asked to make their judgment about various imaginary situations. There were only 50 situations, and they were divided into three groups: "extra-moral", "moral impersonal" and "moral personal".

Situations from the first group do not require resolution of any conflicts between reason and emotions. Here is an example of such a situation: “You bought several pots of flowers in the store, but they all do not fit in the trunk of your car. Will you make two flights so as not to stain the expensive upholstery of the back seat? nine0005

Situations from the second group involve morality and emotions, but do not cause a strong internal conflict between utilitarian considerations (how to achieve the maximum "common good") and emotional restrictions or prohibitions. Example: “You are on duty at the hospital. Due to the accident, poisonous gas entered the ventilation system. If you do nothing, the gas will enter the ward with three patients and kill them. The only way to save them is to turn a special lever that will direct the poisonous gas into the ward where only one patient is lying. He will die, but those three will be saved. Will you turn the lever?" nine0005

The only way to save them is to turn a special lever that will direct the poisonous gas into the ward where only one patient is lying. He will die, but those three will be saved. Will you turn the lever?" nine0005

Situations of the third group required the resolution of an acute conflict between utilitarian considerations about the greatest common good and the need to do with one's own hands an act against which emotions rebel. For example, it was proposed to personally kill some stranger in order to save five other strangers. In contrast to the previous case, where the death of the victim was caused by the "impersonal" turning of the lever, here it was necessary to push the person under the wheels of an approaching train or strangle the child with one's own hands. nine0005

A complete list of all situations can be found here (Pdf, 180 Kb).

The responses of six patients with bilateral TMJ damage were compared with the responses of two control groups: healthy individuals and patients with comparable lesions in other brain regions.

Judgments about "non-moral" and "moral impersonal" situations in all three groups of subjects completely coincided. As for the third category of situations - "moral personal" - contrasting differences were revealed here. People with bilateral damage to the VMPK practically did not see the difference between the "absentee" murder with the help of some kind of lever and with their own hands. They gave almost the same number of positive answers in situations of the second and third categories. Healthy people and those who had damage to other parts of the brain agreed to kill someone with their own hands for the common good three times less than "in absentia". nine0005

Thus, when making moral judgments, people with damaged CMPC are guided only by reason, that is, "utilitarian" considerations about the greatest common good. The emotional mechanisms that guide our behavior, sometimes in spite of dry rational arguments, do not function in these people. They (at least in imaginary situations) can easily strangle someone with their hands, if it is known that this action will ultimately give a greater output of "total good" than inaction. nine0005

nine0005

The results obtained indicate that moral judgments are normally formed under the influence of not only conscious inferences, but also emotions. It seems that VPMC is necessary for the "normal" (same as in healthy people) resolution of moral dilemmas, but only if the dilemma involves a conflict between reason and emotions. Freud believed that the superego is located partly in the conscious, partly in the unconscious part of the psyche. Simplifying somewhat, we can say that the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the emotions it generates are necessary for the functioning of the unconscious fragment of the superego, while conscious moral control is successfully carried out without the participation of this cortex. nine0005

The authors note that their conclusions should not be extended to all emotions in general, but only to those associated with sympathy, empathy or a sense of personal guilt. Some other emotional reactions in patients with TMJ injuries, on the contrary, are more pronounced than in healthy people. For example, they have a reduced ability to restrain anger, they easily fall into a rage, which can also affect decision-making that affects morality and morality (see: Michael Koenigs, Daniel Tranel. Irrational Economic Decision-Making after Ventromedial Prefrontal Damage: Evidence from the Ultimatum Game // The Journal of Neuroscience , January 24, 2007, 27(4): 951–956).

For example, they have a reduced ability to restrain anger, they easily fall into a rage, which can also affect decision-making that affects morality and morality (see: Michael Koenigs, Daniel Tranel. Irrational Economic Decision-Making after Ventromedial Prefrontal Damage: Evidence from the Ultimatum Game // The Journal of Neuroscience , January 24, 2007, 27(4): 951–956).

Source: Michael Koenigs, Liane Young, Ralph Adolphs, Daniel Tranel, Fiery Cushman, Marc Hauser, Antonio Damasio. Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgments // Nature . Advance online publication 21 March 2007.

Alexander Markov

why are we ashamed of the temples, but afraid of the tonsils — T&P

Where do feelings come from in a person? It is known that our brain is responsible for them, but in what areas of it are certain emotions born? T&P publishes a translation of the article and compiles an "emotional brain map" to understand how we feel, why anger is similar to happiness, and why a person cannot live without gentle touches.

nine0053

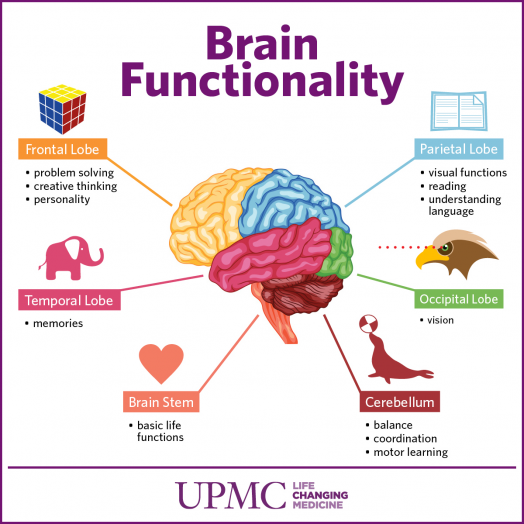

nine0053 Guilt and shame: the temporal lobes

It is easy for us to understand how memory or counting can be processes in the brain. Emotions, however, are not so smooth, partly because in speech we use phrases like “heartbreak” to describe sadness, or “blush” to describe shame. And yet, feelings are a phenomenon from the field of neurophysiology: a process that takes place in the tissues of the main organ of our nervous system. Today, we can partly appreciate it thanks to neuroimaging technology. nine0005

As part of their research, Petra Michl and several of her colleagues at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich recently took a series of MRI scans. They sought to find areas of the brain that are responsible for our ability to feel guilty or ashamed. Scientists have found that shame and guilt seem to be neighbors in the “block”, although each of these feelings has its own anatomical region.

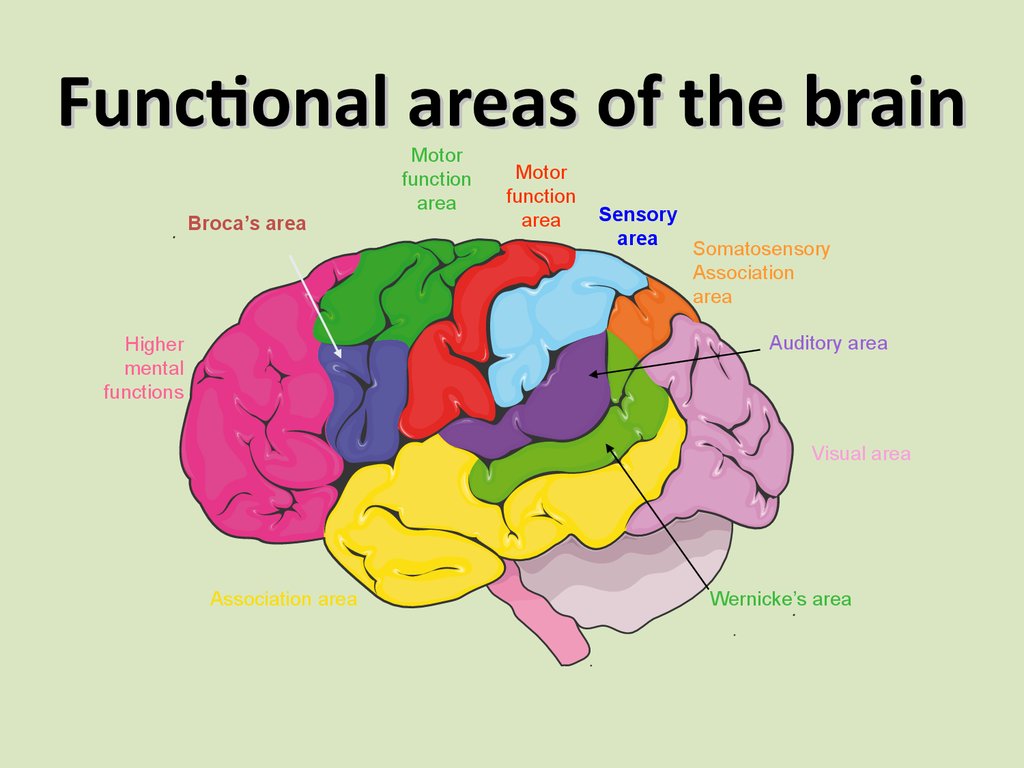

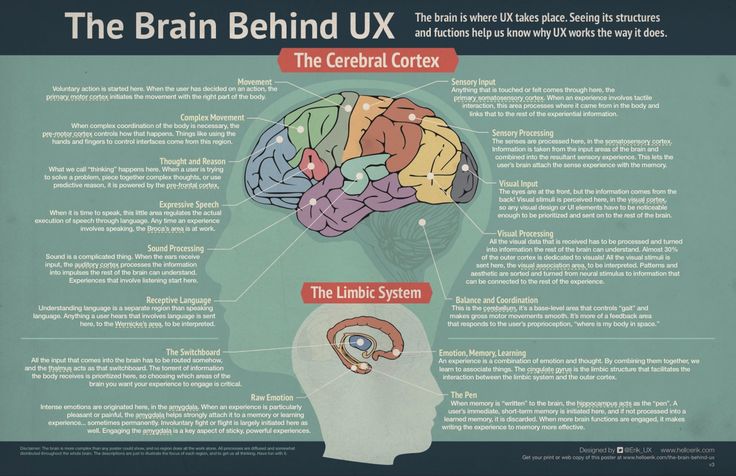

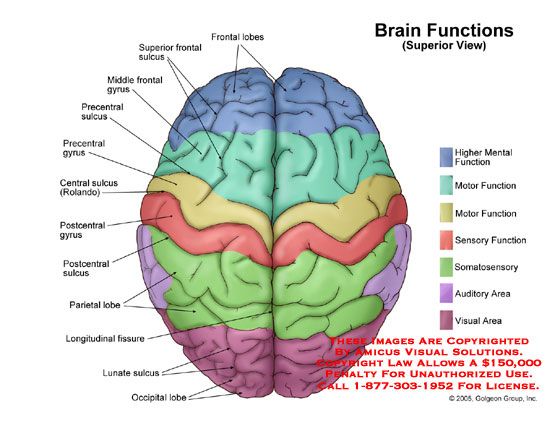

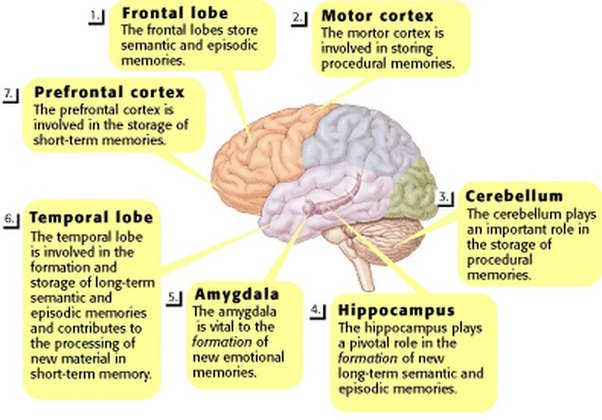

The researchers asked participants to imagine that they felt guilty or ashamed, and in both cases it activated the temporal lobes of the brain. At the same time, shame involved in them the anterior cingulate cortex, which monitors the external environment and informs the person about mistakes, and the parahippocampal gyrus, which is responsible for remembering scenes from the past. Guilt, in turn, "turned on" the lateral occipital-temporal gyrus and the middle temporal gyrus - the center of the vestibular analyzer. In addition, in people who were ashamed, the anterior and middle frontal gyrus began to work, and in those who felt guilty, the amygdala (tonsils) and insular lobe became more active. The last two areas of the brain are part of the limbic system, which regulates our basic fight-or-flight emotions, organ function, blood pressure, and other parameters. nine0005

At the same time, shame involved in them the anterior cingulate cortex, which monitors the external environment and informs the person about mistakes, and the parahippocampal gyrus, which is responsible for remembering scenes from the past. Guilt, in turn, "turned on" the lateral occipital-temporal gyrus and the middle temporal gyrus - the center of the vestibular analyzer. In addition, in people who were ashamed, the anterior and middle frontal gyrus began to work, and in those who felt guilty, the amygdala (tonsils) and insular lobe became more active. The last two areas of the brain are part of the limbic system, which regulates our basic fight-or-flight emotions, organ function, blood pressure, and other parameters. nine0005

Comparing MRI images of the brains of people of different sexes, scientists found that in women, guilt affected only the temporal lobes, while in men, the frontal lobes, occipital lobes and tonsils began to work in parallel - one of the most ancient elements of the brain that are responsible for the feeling of fear, anger, panic and pleasure.

Fear and Anger: The Amygdala

During fetal development, the limbic system forms immediately after the brainstem, which organizes reflexes and connects the brain to the spinal cord. Her work is the feelings and actions that are necessary for the survival of the species. The tonsils are an important element of the limbic system. These areas are located near the hypothalamus, inside the temporal lobes, and are activated when we see food, sexual partners, rivals, crying babies, and so on. The body's varied reactions to fear are also their work: if you feel like a stranger is following you in the park at night and your heart starts beating wildly, this is due to the activity of the tonsils. In the course of several independent studies conducted in various centers and universities, experts managed to find out that even artificial stimulation of these areas causes a person to feel the approach of imminent danger. nine0005

Anger is also a function of the amygdala in many ways. However, it is very different from fear, sadness, and other negative emotions. Human anger is amazing in that it is similar to happiness: like joy and pleasure, it makes us move forward, while fear or grief forces us to step back. Like other emotions, anger, anger and rage cover a variety of parts of the brain: in order to realize their impulse, this organ needs to assess the situation, turn to memory and experience, regulate the production of hormones in the body, and do much more. nine0005

However, it is very different from fear, sadness, and other negative emotions. Human anger is amazing in that it is similar to happiness: like joy and pleasure, it makes us move forward, while fear or grief forces us to step back. Like other emotions, anger, anger and rage cover a variety of parts of the brain: in order to realize their impulse, this organ needs to assess the situation, turn to memory and experience, regulate the production of hormones in the body, and do much more. nine0005

Tenderness and comfort: the somatosensory cortex

In many cultures, it is customary to hide sadness and shock: for example, in British English there is even an idiomatic expression "keep a stiff upper lip", which means "not to show your feelings." Nevertheless, neuroscientists argue that from the point of view of the physiology of the brain, a person simply needs the participation of other people. “Clinical experiments show that loneliness provokes stress more than any other factor,” says Stefan Klein, a German scientist and author of The Science of Happiness. “Loneliness is a burden on the brain and body. It results in restlessness, confusion in thoughts and feelings (a consequence of the work of stress hormones) and a weakened immune system. In isolation, people become sad and sick.” nine0005

“Loneliness is a burden on the brain and body. It results in restlessness, confusion in thoughts and feelings (a consequence of the work of stress hormones) and a weakened immune system. In isolation, people become sad and sick.” nine0005

One study after another shows that companionship is good for a person physically and spiritually. It prolongs life and improves its quality. “One touch from someone close to you and worthy of your trust eases sadness,” Stefan says. "This is a consequence of the work of neurotransmitters - oxytocin and opioids - which are released during moments of tenderness."

Recently, British researchers were able to confirm the theory of the usefulness of petting using computed tomography. They found that the touch of other people causes strong bursts of activity in the somatosensory cortex, which is already working constantly, monitoring all our tactile sensations. Scientists have come to the conclusion that the impulses that arise if someone gently touches our body during difficult times are associated with the process of isolating critical stimuli from the general stream that can change everything for us..png) Experts also noticed that participants in the experiment experienced grief easier when they were held by the hand of a stranger, and much easier when their palms were touched by a loved one. nine0005

Experts also noticed that participants in the experiment experienced grief easier when they were held by the hand of a stranger, and much easier when their palms were touched by a loved one. nine0005

Joy and laughter: the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus

When we experience joy, experience happiness, laugh or smile, many different areas of our brain “light up”. The already familiar amygdala, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and anterior insular cortex are involved in the process of creating and processing positive emotions, so that the feeling of joy, like anger, sadness or fear, covers the entire brain.

In happy moments, the right amygdala becomes much more active than the left. Today it is widely believed that the left hemisphere of our brain is responsible for logic, and the right hemisphere for creativity. However, we have recently known that this is not the case. Both parts of the brain are required for most functions, although hemispheric asymmetries exist: for example, the largest speech centers are located on the left, while intonation and accent processing is more localized on the right. nine0005

nine0005

The prefrontal cortex is several areas of the frontal lobes of the brain that are located in the front of the hemispheres, just behind the frontal bone. They are connected to the limbic system and are responsible for our ability to determine our goals, develop plans, achieve the desired results, change course and improvise. Studies show that in happy moments, the prefrontal cortex of the left hemisphere is more active in women than the same area on the right.

The hippocampus, which is located deep in the temporal lobes, together with the tonsils, help us to separate important emotional events from insignificant ones, so that the former can be stored in long-term memory, and the latter can be discarded. In other words, hippocampi evaluate happy events in terms of their significance for the archive. The anterior insular cortex helps them do this. It is also connected with the limbic system and behaves most actively when a person remembers pleasant or sad events. nine0005

Lust and love: not emotions

Today, the human brain is studied by thousands of neuroscientists around the world.