Panic attack fever

Psychogenic fever: how psychological stress affects body temperature in the clinical population

1. Bakwin H. Emotional deprivation in infants. J Pediatr 1949; 35:512-21; PMID:18143946; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0022-3476(49)80071-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. White KL, Long WN Jr. The incidence of psychogenic fever in a university hospital. J Chronic Dis 1958; 8:567-86; PMID:13587612; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0021-9681(58)90050-X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Meyer R, Beck D. Psychodynamics of psychogenic fever. Zeitschrift fur Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychoanalyse 1976; 22:169-70; PMID:941539 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Malleson N. Panic and phobia; a possible method of treatment. Lancet 1959; 1:225-7; PMID:13631975; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(59)90052-2 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. O'Toole JK, Dyck G. Report of psychogenic fever in catatonia responding to electroconvulsive therapy. Dis Nerv Syst 1977; 38:852-3; PMID:908250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. McNeil GN, Leighton LH, Elkins AM. Possible psychogenic fever of 103.5 degrees F in a patient with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:896-7; PMID:6731643; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1176/ajp.141.7.896 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Weinstein L. Clinically benign fever of unknown origin: a personal retrospective. Rev Infect Dis 1985; 7:692-9; PMID:4059757; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/clinids/7.5.692 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Timmerman RJ, Thompson J, Noordzij HM, van der Meer JW. Psychogenic periodic fever. Neth J Med 1992; 41:158-60; PMID:1470287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Miric D, Venet R, Aproh E, Nguyen-Duc H. Psychogenic fever or psychogenic hyperthermia? J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45:1287-8; PMID:9329503; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb03796.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Araki T, Oka T, Oyama N, Akamine M, Kubo C. A case of psychogenic fever treated successfully with art therapy. Jpn J Psychosom Med 2004; 44:289-94 [Google Scholar]

11. Nozu T, Uehara A. The diagnoses and outcomes of patients complaining of fever without any abnormal findings on diagnostic tests. Intern Med 2005; 44:901-2; PMID:16157998; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.901 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Nozu T, Uehara A. The diagnoses and outcomes of patients complaining of fever without any abnormal findings on diagnostic tests. Intern Med 2005; 44:901-2; PMID:16157998; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.901 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Kura N, Oka T, Ando T, Ishikawa T, Kubo C, Ago Y. A case of psychogenic fever treated successfully with tandospirone in combination with psychotherapy and autogenic training. Jpn J Psychosom Med 2004; 44:297-303 [Google Scholar]

13. Hiramoto T, Oka T, Yoshihara K, Kubo C. Pyrogenic cytokines did not mediate a stress interview-induced hyperthermic response in a patient with psychogenic fever: a case report. Psychosom Med 2009; 71:932-6; PMID:19875636; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bfb02b [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Oka T, Kanemitsu Y, Sudo N, Hayashi H, Oka K. Psychological stress contributed to the development of low-grade fever in a patient with chronic fatigue syndrome: a case report. Biopsychosoc Med 2013; 7:7; PMID:23497734; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1751-0759-7-7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Biopsychosoc Med 2013; 7:7; PMID:23497734; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1751-0759-7-7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Oka T, Oka K. Age and gender differences of psychogenic fever: a review of the Japanese literature. Biopsychosoc Med 2007; 1:11; PMID:17511878; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1751-0759-1-11 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Kaneda Y, Tsuji S, Oka T. Age distribution and gender differences in psychogenic fever patients. Biopsychosoc Med 2009; 3:6; PMID:19379524; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1751-0759-3-6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Friedmann M, Kohnstmann O. Zur Pathogenese und Psychotherapie bei Basodowsher Krankheit. Ztschr f d ges Neurol u Psychiat 1914; 23:357; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF02867687 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Falcon-Lesses M, Proger SH. Psychogenic fever. N Engl J Med 1930; 203:1034-6; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJM193011202032113 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Bakwin H. Psychogenic fever in infants. Am J Dis Child 1944; 67:176-81 [Google Scholar]

Bakwin H. Psychogenic fever in infants. Am J Dis Child 1944; 67:176-81 [Google Scholar]

20. Kintner AR, Rowntree LG. Long continued, low grade, idiopathic fever. JAMA 1934;102:889-92; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/jama.1934.02750120001001 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Wolf S, Wolf HD. Intermittent fever of unknown origin. Arch Internal Med 1942;70:293-302; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/archinte.1942.00200200113007 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Singer R, Harker CT, Vander AJ, Kluger MJ. Hyperthermia induced by open-field stress is blocked by salicylate. Physiol Behav 1986; 36:1179-82; PMID:3725924; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90497-X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Soszynski D, Kozak W, Kluger MJ. Endotoxin tolerance does not alter open field-induced fever in rats. Physiol Behav 1998; 63:689-92; PMID:9523916; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0031-9384(97)00515-5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Butterweck V, Prinz S, Schwaninger M. The role of interleukin-6 in stress-induced hyperthermia and emotional behaviour in mice. Behav Brain Res 2003; 144:49-56; PMID:12946594; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0166-4328(03)00059-7 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Behav Brain Res 2003; 144:49-56; PMID:12946594; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0166-4328(03)00059-7 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Long NC, Vander AJ, Kunkel SL, Kluger MJ. Antiserum against tumor necrosis factor increases stress hyperthermia in rats. Am J Physiol 1990; 258:R591-5; PMID:2316707 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Morimoto A, Nakamori T, Morimoto K, Tan N, Murakami N. The central role of corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF-41) in psychological stress in rats. J Physiol 1993; 460:221-9; PMID:8487193; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019468 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Oka T, Oka K, Kobayashi T, Sugimoto Y, Ichikawa A, Ushikubi F, Narumiya S, Saper CB. Characteristics of thermoregulatory and febrile responses in mice deficient in prostaglandin EP1 and EP3 receptors. J Physiol 2003; 551:945-54; PMID:12837930; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.048140 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Shibata H, Nagasaka T. Contribution of nonshivering thermogenesis to stress-induced hyperthermia in rats. Jpn J Physiol 1982; 32:991-5; PMID:7169705; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2170/jjphysiol.32.991 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Shibata H, Nagasaka T. Contribution of nonshivering thermogenesis to stress-induced hyperthermia in rats. Jpn J Physiol 1982; 32:991-5; PMID:7169705; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2170/jjphysiol.32.991 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Shibata H, Nagasaka T. Role of sympathetic nervous system in immobilization- and cold-induced brown adipose tissue thermogenesis in rats. Jpn J Physiol 1984; 34:103-11; PMID:6727066; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2170/jjphysiol.34.103 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Gao B, Kikuchi-Utsumi K, Ohinata H, Hashimoto M, Kuroshima A. Repeated immobilization stress increases uncoupling protein 1 expression and activity in Wistar rats. Jpn J Physiol 2003; 53:205-13; PMID:14529581; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2170/jjphysiol.53.205 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Ootsuka Y, Blessing WW, Nalivaiko E. Selective blockade of 5-HT2A receptors attenuates the increased temperature response in brown adipose tissue to restraint stress in rats. Stress 2008; 11:125-33; PMID:18311601; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1080/10253890701638303 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi.org/ 10.1080/10253890701638303 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Borsini F, Lecci A, Volterra G, Meli A. A model to measure anticipatory anxiety in mice? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989; 98:207-11; PMID:2502791; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00444693 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Zethof TJ, Van der Heyden JA, Tolboom JT, Olivier B. Stress-induced hyperthermia as a putative anxiety model. Eur J Pharmacol 1995; 294:125-35; PMID:8788424; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00520-X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Vinkers CH, van Bogaert MJ, Klanker M, Korte SM, Oosting R, Hanania T, Hopkins SC, Olivier B, Groenink L. Translational aspects of pharmacological research into anxiety disorders: the stress-induced hyperthermia (SIH) paradigm. Eur J Pharmacol 2008; 585:407-25; PMID:18420191; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.097 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Beig MI, Baumert M, Walker FR, Day TA, Nalivaiko E. Blockade of 5-HT2A receptors suppresses hyperthermic but not cardiovascular responses to psychosocial stress in rats. Neuroscience 2009;159: 1185-91; PMID:19356699; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.038 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Neuroscience 2009;159: 1185-91; PMID:19356699; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.038 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Hayashida S, Oka T, Mera T, Tsuji S. Repeated social defeat stress induces chronic hyperthermia in rats. Physiol Behav 2010; 101:124-31; PMID:20438740; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.027 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Lkhagvasuren B, Nakamura Y, Oka T, Sudo N, Nakamura K. Social defeat stress induces hyperthermia through activation of thermoregulatory sympathetic premotor neurons in the medullary raphe region. Eur J Neurosci 2011; 34:1442-52; PMID:21978215; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07863.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Lkhagvasuren B, Oka T, Nakamura Y, Hayashi H, Sudo N, Nakamura K. Distribution of Fos-immunoreactive cells in rat forebrain and midbrain following social defeat stress and diazepam treatment. Neuroscience 2014; 272:34-57; PMID:24797330; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j. neuroscience.2014.04.047 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

neuroscience.2014.04.047 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Mohammed M, Ootsuka Y, Blessing W. Brown adipose tissue thermogenesis contributes to emotional hyperthermia in a resident rat suddenly confronted with an intruder rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2014; 306:R394-400; PMID:24452545; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.00475.2013 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Yokoi Y. Effect of ambient temperature upon emotional hyperthermia and hypothermia in rabbits. J Appl Physiol 1966; 21:1795-8; PMID:5929304 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Snow AE, Horita A. Interaction of apomorphine and stressors in the production of hyperthermia in the rabbit. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1982; 220:335-9; PMID:7199085 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Kohlhause S, Hoffmann K, Schlumbohm C, Fuchs E, Flugge G. Nocturnal hyperthermia induced by social stress in male tree shrews: relation to low testosterone and effects of age. Physiol Behav 2011; 104:786-95; PMID:21827778; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.07.023 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi.org/ 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.07.023 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Schmelting B, Corbach-Sohle S, Kohlhause S, Schlumbohm C, Flugge G, Fuchs E. Agomelatine in the tree shrew model of depression: effects on stress-induced nocturnal hyperthermia and hormonal status. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2014; 24:437-47; PMID:23978391; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.07.010 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Pedernera-Romano C, Ruiz de la Torre JL, Badiella L, Manteca X. Effect of perphenazine enanthate on open-field test behaviour and stress-induced hyperthermia in domestic sheep. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2010; 94:329-32; PMID:19799930; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.09.013 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Muchlinski AE, Baldwin BC, Padick DA, Lee BY, Salguero HS, Gramajo R. California ground squirrel body temperature regulation patterns measured in the laboratory and in the natural environment. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 1998; 120:365-72; PMID:9773514; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/S1095-6433(98)10037-5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi.org/ 10.1016/S1095-6433(98)10037-5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Lee BY, Padick DA, Muchlinski AE. Stress fever magnitude in laboratory-maintained California ground squirrels varies with season. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2000; 125:325-30; PMID:10794961; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1095-6433(00)00157-4 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Parr LA, Hopkins WD. Brain temperature asymmetries and emotional perception in chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes. Physiol Behav 2000; 71:363-71; PMID:11150569; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0031-9384(00)00349-8 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Meyer LC, Fick L, Matthee A, Mitchell D, Fuller A. Hyperthermia in captured impala (Aepyceros melampus): a fright not flight response. J Wildl Dis 2008; 44:404-16; PMID:18436672; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7589/0090-3558-44.2.404 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Gray DA, Maloney SK, Kamerman PR. Restraint increases afebrile body temperature but attenuates fever in Pekin ducks (Anas platyrhynchos). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008; 294:R1666-71; PMID:18337310; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.00865.2007 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008; 294:R1666-71; PMID:18337310; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.00865.2007 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Bittencourt Mde A, Melleu FF, Marino-Neto J. Stress-induced core temperature changes in pigeons (Columba livia). Physiol Behav 2015; 139:449-58; PMID:25479572; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.11.067 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Oka T, Oka K, Hori T. Mechanisms and mediators of psychological stress-induced rise in core temperature. Psychosom Med 2001; 63:476-86; PMID:11382276; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00006842-200105000-00018 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Vinkers CH, Groenink L, van Bogaert MJ, Westphal KG, Kalkman CJ, van Oorschot R, Oosting RS, Olivier B, Korte SM. Stress-induced hyperthermia and infection-induced fever: two of a kind? Physiol Behav 2009; 98:37-43; PMID:19375439; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.04.004 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Ivanov AI, Pero RS, Scheck AC, Romanovsky AA. Prostaglandin E(2)-synthesizing enzymes in fever: differential transcriptional regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2002; 283:R1104-17; PMID:12376404; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.00347.2002 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Prostaglandin E(2)-synthesizing enzymes in fever: differential transcriptional regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2002; 283:R1104-17; PMID:12376404; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.00347.2002 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. Ivanov AI, Romanovsky AA. Prostaglandin E2 as a mediator of fever: synthesis and catabolism. Front Biosci 2004; 9:1977-93; PMID:14977603; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2741/1383 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

55. Steiner AA, Ivanov AI, Serrats J, Hosokawa H, Phayre AN, Robbins JR, Roberts JL, Kobayashi S, Matsumura K, Sawchenko PE, et al.. Cellular and molecular bases of the initiation of fever. PLoS Biol 2006; 4:e284; PMID:16933973; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040284 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. Romanovsky AA, Steiner AA, Matsumura K. Cells that trigger fever. Cell Cycle 2006; 5:2195-7; PMID:16969135; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.5.19.3321 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Yamagata K, Matsumura K, Inoue W, Shiraki T, Suzuki K, Yasuda S, Sugiura H, Cao C, Watanabe Y, Kobayashi S. Coexpression of microsomal-type prostaglandin E synthase with cyclooxygenase-2 in brain endothelial cells of rats during endotoxin-induced fever. J Neurosci 2001; 21:2669-77; PMID:11306620 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yamagata K, Matsumura K, Inoue W, Shiraki T, Suzuki K, Yasuda S, Sugiura H, Cao C, Watanabe Y, Kobayashi S. Coexpression of microsomal-type prostaglandin E synthase with cyclooxygenase-2 in brain endothelial cells of rats during endotoxin-induced fever. J Neurosci 2001; 21:2669-77; PMID:11306620 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Engblom D, Saha S, Engstrom L, Westman M, Audoly LP, Jakobsson PJ, Blomqvist A. Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 is the central switch during immune-induced pyresis. Nat Neurosci 2003; 6:1137-8; PMID:14566340; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nn1137 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Schiltz JC, Sawchenko PE. Signaling the brain in systemic inflammation: the role of perivascular cells. Front Biosci 2003; 8:s1321-9; PMID:12957837; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2741/1211 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

60. Kluger MJ. Fever: role of pyrogens and cryogens. Physiol Rev 1991; 71:93-127; PMID:1986393 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Leon LR. Invited review: cytokine regulation of fever: studies using gene knockout mice. J Appl Physiol 2002; 92:2648-55; PMID:12015385; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/japplphysiol.01005.2001 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Leon LR. Invited review: cytokine regulation of fever: studies using gene knockout mice. J Appl Physiol 2002; 92:2648-55; PMID:12015385; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/japplphysiol.01005.2001 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Nakamura K, Matsumura K, Hubschle T, Nakamura Y, Hioki H, Fujiyama F, Boldogkoi Z, Konig M, Thiel HJ, Gerstberger R, et al.. Identification of sympathetic premotor neurons in medullary raphe regions mediating fever and other thermoregulatory functions. J Neurosci 2004; 24:5370-80; PMID:15190110; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1219-04.2004 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Rathner JA, Madden CJ, Morrison SF. Central pathway for spontaneous and prostaglandin E2-evoked cutaneous vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008; 295:R343-54; PMID:18463193; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.00115.2008 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

64. Kerman IA, Enquist LW, Watson SJ, Yates BJ. Brainstem substrates of sympatho-motor circuitry identified using trans-synaptic tracing with pseudorabies virus recombinants. J Neurosci 2003; 23:4657-66; PMID:12805305 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brainstem substrates of sympatho-motor circuitry identified using trans-synaptic tracing with pseudorabies virus recombinants. J Neurosci 2003; 23:4657-66; PMID:12805305 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Tanaka M, Owens NC, Nagashima K, Kanosue K, McAllen RM. Reflex activation of rat fusimotor neurons by body surface cooling, and its dependence on the medullary raphe. J Physiol 2006; 572:569-83; PMID:16484305; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.102400 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

66. Nakamura K, Morrison SF. Central efferent pathways for cold-defensive and febrile shivering. J Physiol 2011; 589:3641-58; PMID:21610139; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.210047 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

67. Nakamura K, Matsumura K, Kaneko T, Kobayashi S, Katoh H, Negishi M. The rostral raphe pallidus nucleus mediates pyrogenic transmission from the preoptic area. J Neurosci 2002; 22:4600-10; PMID:12040067 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Lazarus M, Yoshida K, Coppari R, Bass CE, Mochizuki T, Lowell BB, Saper CB. EP3 prostaglandin receptors in the median preoptic nucleus are critical for fever responses. Nat Neurosci 2007; 10:1131-3; PMID:17676060; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nn1949 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Lazarus M, Yoshida K, Coppari R, Bass CE, Mochizuki T, Lowell BB, Saper CB. EP3 prostaglandin receptors in the median preoptic nucleus are critical for fever responses. Nat Neurosci 2007; 10:1131-3; PMID:17676060; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nn1949 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

69. Morrison SF, Nakamura K. Central neural pathways for thermoregulation. Front Biosci 2011; 16:74-104; PMID:21196160; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2741/3677 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

70. DiMicco JA, Sarkar S, Zaretskaia MV, Zaretsky DV. Stress-induced cardiac stimulation and fever: common hypothalamic origins and brainstem mechanisms. Auton Neurosci 2006; 126–127:106-19; PMID:16580890; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.02.010 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

71. Dimicco JA, Zaretsky DV. The dorsomedial hypothalamus: a new player in thermoregulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007; 292:R47-63; PMID:16959861; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu. 00498.2006 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

00498.2006 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

72. Kataoka N, Hioki H, Kaneko T, Nakamura K. Psychological stress activates a dorsomedial hypothalamus-medullary raphe circuit driving brown adipose tissue thermogenesis and hyperthermia. Cell Metab 2014; 20:346-58; PMID:2498183715677520 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Saha S, Engstrom L, Mackerlova L, Jakobsson PJ, Blomqvist A. Impaired febrile responses to immune challenge in mice deficient in microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2005; 288:R1100-7; PMID:15677520; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.00872.2004 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

74. Lecci A, Borsini F, Volterra G, Meli A. Pharmacological validation of a novel animal model of anticipatory anxiety in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990; 101:255-61; PMID:1971957; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF02244136 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

75. Bouwknecht JA, Hijzen TH, van der Gugten J, Maes RA, Olivier B. Stress-induced hyperthermia in mice: effects of flesinoxan on heart rate and body temperature. Eur J Pharmacol 2000; 400:59-66; PMID:10913585; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0014-2999(00)00387-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Eur J Pharmacol 2000; 400:59-66; PMID:10913585; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0014-2999(00)00387-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

76. Olivier B, Bouwknecht JA, Pattij T, Leahy C, van Oorschot R, Zethof TJ. GABAA-benzodiazepine receptor complex ligands and stress-induced hyperthermia in singly housed mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2002; 72:179-88; PMID:11900786; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0091-3057(01)00759-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

77. Pecoraro N, de Jong H, Ginsberg AB, Dallman MF. Lesions of the medial prefrontal cortex enhance the early phase of psychogenic fever to unexpected sucrose concentration reductions, promote recovery from negative contrast and enhance spontaneous recovery of sucrose-entrained anticipatory activity. Neuroscience 2008; 153:901-17; PMID:18455879; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.043 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

78. Pae YS, Lai H, Horita A. Hyperthermia in the rat from handling stress blocked by naltrexone injected into the preoptic-anterior hypothalamus. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1985; 22:337-9; PMID:4039067; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90400-9 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1985; 22:337-9; PMID:4039067; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90400-9 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

79. Egawa M, Yoshimatsu H, Bray GA. Preoptic area injection of corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulates sympathetic activity. Am J Physiol 1990; 259:R799-806; PMID:2221147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Vinkers CH, Bijlsma EY, Houtepen LC, Westphal KG, Veening JG, Groenink L, Olivier B. Medial amygdala lesions differentially influence stress responsivity and sensorimotor gating in rats. Physiol Behav 2010; 99:395-401; PMID:20006965; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.12.006 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

81. Ootsuka Y, Mohammed M. Activation of the habenula complex evokes autonomic physiological responses similar to those associated with emotional stress. Physiol Rep 2015; 3:e12297; PMID:25677551; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.14814/phy2.12297 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

82. Zhang W, Sunanaga J, Takahashi Y, Mori T, Sakurai T, Kanmura Y, Kuwaki T. Orexin neurons are indispensable for stress-induced thermogenesis in mice. J Physiol 2010; 588:4117-29; PMID:20807795; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.195099 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Orexin neurons are indispensable for stress-induced thermogenesis in mice. J Physiol 2010; 588:4117-29; PMID:20807795; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.195099 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

83. Eikelboom R. Learned anticipatory rise in body temperature due to handling. Physiol Behav 1986; 37:649-53; PMID:3749329; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90299-4 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

84. Pardon MC, Kendall DA, Perez-Diaz F, Duxon MS, Marsden CA. Repeated sensory contact with aggressive mice rapidly leads to an anticipatory increase in core body temperature and physical activity that precedes the onset of aversive responding. Eur J Neurosci 2004; 20:1033-50; PMID:15305872; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03549.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

85. Kant GJ, Bauman RA, Pastel RH, Myatt CA, Closser-Gomez E, D'Angelo CP. Effects of controllable vs. uncontrollable stress on circadian temperature rhythms. Physiol Behav 1991; 49:625-30; PMID:2062941; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90289-Z [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi.org/ 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90289-Z [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

86. Endo Y, Shiraki K. Behavior and body temperature in rats following chronic foot shock or psychological stress exposure. Physiol Behav 2000; 71:263-8; PMID:11150557; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0031-9384(00)00339-5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

87. Bhatnagar S, Vining C, Iyer V, Kinni V. Changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function, body temperature, body weight and food intake with repeated social stress exposure in rats. J Neuroendocrinol 2006; 18:13-24; PMID:16451216; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01375.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

88. Nozu T, Okano S, Kikuchi K, Yahata T, Kuroshima A. Effect of immobilization stress on in vitro and in vivo thermogenesis of brown adipose tissue. Jpn J Physiol 1992; 42:299-308; PMID:1434095; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2170/jjphysiol.42.299 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

89. Rygula R, Abumaria N, Havemann-Reinecke U, Ruther E, Hiemke C, Zernig G, Fuchs E, Flugge G. Pharmacological validation of a chronic social stress model of depression in rats: effects of reboxetine, haloperidol and diazepam. Behav Pharmacol 2008; 19:183-96; PMID:18469536; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282fe8871 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Pharmacological validation of a chronic social stress model of depression in rats: effects of reboxetine, haloperidol and diazepam. Behav Pharmacol 2008; 19:183-96; PMID:18469536; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282fe8871 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

90. Marks A, Vianna DM, Carrive P. Nonshivering thermogenesis without interscapular brown adipose tissue involvement during conditioned fear in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2009; 296:R1239-47; PMID:19211724; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.90723.2008 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

91. Carrive P, Gorissen M. Premotor sympathetic neurons of conditioned fear in the rat. Eur J Neurosci 2008; 28:428-46; PMID:18702716; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06351.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

92. Kuroshima A, Habara Y, Uehara A, Murazumi K, Yahata T, Ohno T. Cross adaption between stress and cold in rats. Pflugers Arch 1984; 402:402-8; PMID:6522247; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00583941 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

93. Kuroshima A, Yahata T. Changes in the colonic temperature and metabolism during immobilization stress in repetitively immobilized or cold-acclimated rats. Jpn J Physiol 1985; 35:591-7; PMID:4068366; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2170/jjphysiol.35.591 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Kuroshima A, Yahata T. Changes in the colonic temperature and metabolism during immobilization stress in repetitively immobilized or cold-acclimated rats. Jpn J Physiol 1985; 35:591-7; PMID:4068366; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2170/jjphysiol.35.591 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

94. Sugama S, Fujita M, Hashimoto M, Conti B. Stress induced morphological microglial activation in the rodent brain: involvement of interleukin-18. Neuroscience 2007; 146:1388-99; PMID:17433555; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.043 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

95. Hinwood M, Morandini J, Day TA, Walker FR. Evidence that microglia mediate the neurobiological effects of chronic psychological stress on the medial prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 2012; 22:1442-54; PMID:21878486; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/cercor/bhr229 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

96. Hinwood M, Tynan RJ, Charnley JL, Beynon SB, Day TA, Walker FR. Chronic stress induced remodeling of the prefrontal cortex: structural re-organization of microglia and the inhibitory effect of minocycline. Cereb Cortex 2013; 23:1784-97; PMID:22710611; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/cercor/bhs151 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Cereb Cortex 2013; 23:1784-97; PMID:22710611; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/cercor/bhs151 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

97. Johnson JD, Zimomra ZR, Stewart LT. Beta-adrenergic receptor activation primes microglia cytokine production. J Neuroimmunol 2013; 254:161-4; PMID:22944319; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.08.007 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

98. Oka T, Aou S, Hori T. Intracerebroventricular injection of interleukin-1 β induces hyperalgesia in rats. Brain Res 1993; 624:61-8; PMID:8252417; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90060-Z [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

99. Oka T, Oka K, Hosoi M, Hori T. Intracerebroventricular injection of interleukin-6 induces thermal hyperalgesia in rats. Brain Res 1995; 692:123-8; PMID:8548295; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00691-I [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

100. Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol 2006; 27:24-31; PMID:16316783; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi.org/ 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

101. Song C, Wang H. Cytokines mediated inflammation and decreased neurogenesis in animal models of depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2011; 35:760-8; PMID:20600462; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.06.020 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

102. Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 65:732-41; PMID:19150053; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

103. Wynn FR. The psychic factor as an element in temperature disturbance. JAMA 1919; 73:31-4; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/jama.1919.02610270035010 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

104. Kleitman N. The effect of motion pictures on body temperature. Science 1945; 102:430-1; PMID:17730629; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.102.2652. 430 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

430 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

105. Gotsev T, Ivanov A. Psychogenic elevation of body temperature in healthy persons. Acta Physiol Hung 1950; 1:53-62; PMID:14782995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Aschoff J, Fatranska M, Gerecke U, Giedke H. Twenty-four-hour rhythms of rectal temperature in humans: effects of sleep-interruptions and of test-sessions. Pflugers Arch 1974; 346:215-22; PMID:4856415; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00595708 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

107. Renbourn ET. Body temperature and pulse rate in boys and young men prior to sporting contests. A study of emotional hyperthermia: with a review of the literature. J Psychosom Res 1960; 4:149-75; PMID:14437326; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0022-3999(60)90008-8 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

108. Marazziti D, Di Muro A, Castrogiovanni P. Psychological stress and body temperature changes in humans. Physiol Behav 1992; 52:393-5; PMID:1326118; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90290-I [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

109. Briese E. Emotional hyperthermia and performance in humans. Physiol Behav 1995; 58:615-8; PMID:8587973; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00091-V [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Briese E. Emotional hyperthermia and performance in humans. Physiol Behav 1995; 58:615-8; PMID:8587973; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00091-V [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

110. Shah SJ, PAtel HM. Effect of examination stress on parameters of autonomic functions in medical students. Int J Sci Res 2014; 3:273-6 [Google Scholar]

111. Vinkers CH, Penning R, Hellhammer J, Verster JC, Klaessens JH, Olivier B, Kalkman CJ. The effect of stress on core and peripheral body temperature in humans. Stress 2013; 16:520-30; PMID:23790072; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3109/10253890.2013.807243 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

112. Oka T, Kaneda Y, Takenaga M, Hayashida S, Tamagawa Y, Kodama N, Tsuji S. Efficacy of paroxetine for treating chronic stress-induced low-grade fever. Jpn J Psychosom Intern Med 2006; 10:5-8 [Google Scholar]

113. Reimann HA. The problem of long, continued, low grade fever. JAMA 1936;107:1089-94; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/jama.1936.02770400001001 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

114. Ziegler LH, Cash PT. A study of the influence of emotions and affects on the surface temperature of the human body. Am J Psychiatr 1938;95:677-96; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1176/ajp.95.3.677 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Ziegler LH, Cash PT. A study of the influence of emotions and affects on the surface temperature of the human body. Am J Psychiatr 1938;95:677-96; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1176/ajp.95.3.677 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

115. Duras FP. Hyperpyrexia due to hysteria. Lancet 1942; 11:39; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)62135-9 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

116. Oka T, Oka K. Mechanisms of psychogenic fever. Adv Neuroimmune Biol 2012; 3:3-17 [Google Scholar]

117. Bohorfoush JG, Craig JB, Patterson HS. Catatonia as a cause of fever of undetermined origin. J Med Assoc Ga 1965; 54:324-5; PMID:5887902 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118. Buchwald D, Goldenberg DL, Sullivan JL, Komaroff AL. The “chronic, active Epstein-Barr virus infection” syndrome and primary fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 1987; 30:1132-6; PMID:2823835; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/art.1780301007 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

119. Enerback S. Human brown adipose tissue. Cell Metab 2010; 11:248-52; PMID:20374955; http://dx. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.008 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.008 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

120. van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Vanhommerig JW, Smulders NM, Drossaerts JM, Kemerink GJ, Bouvy ND, Schrauwen P, Teule GJ. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:1500-8; PMID:19357405; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa0808718 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

121. Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, Kuo FC, Palmer EL, Tseng YH, Doria A, et al.. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:1509-17; PMID:19357406; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

122. Virtanen KA, Lidell ME, Orava J, Heglind M, Westergren R, Niemi T, Taittonen M, Laine J, Savisto NJ, Enerback S, et al.. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:1518-25; PMID:19357407; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa0808949 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

123. Saito M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Matsushita M, Watanabe K, Yoneshiro T, Nio-Kobayashi J, Iwanaga T, Miyagawa M, Kameya T, Nakada K, et al.. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes 2009; 58:1526-31; PMID:19401428; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2337/db09-0530 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Saito M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Matsushita M, Watanabe K, Yoneshiro T, Nio-Kobayashi J, Iwanaga T, Miyagawa M, Kameya T, Nakada K, et al.. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes 2009; 58:1526-31; PMID:19401428; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2337/db09-0530 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

124. Lkhagvasuren B, Masuno T, Kanemitsu Y, Sudo N, Kubo C, Oka T. Increased prevalence of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome in psychogenic fever patients. Psychother Psychosom 2013; 82:269-70; PMID:23735890; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000345171 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

125. Lkhagvasuren B, Tanaka H, Sudo N, Kubo C, Oka T. Characteristics of the orthostatic cardiovascular response in adolescent patients with psychogenic fever. Psychother Psychosom 2014; 83:318-9; PMID:25116930; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000360999 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

126. Oka T. Mechanism and treatment of psychogenic fever. Jpn J Psychosom Intern Med 2005; 9:117-21. [Google Scholar]

Mechanism and treatment of psychogenic fever. Jpn J Psychosom Intern Med 2005; 9:117-21. [Google Scholar]

127. Oka T, Hayashida S, Kaneda Y, Kodama N, Hashimoto T, Tsuji S. Why do chronic stress-induced hyperthermia patients worry about slightly elevated body temperature? Jpn J Psychosom Intern Med 2006; 10:243-6 [Google Scholar]

128. Oka T. Influence of psychological stress on chronic fatigue syndrome. Adv Neuroimmune Biol 2013; 4:301-9 [Google Scholar]

129. Almeida MC, Steiner AA, Branco LG, Romanovsky AA: Neural substrate of cold-seeking behavior in endotoxin shock. PLoS One 2006; 1:e1; PMID:17183631; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0000001 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

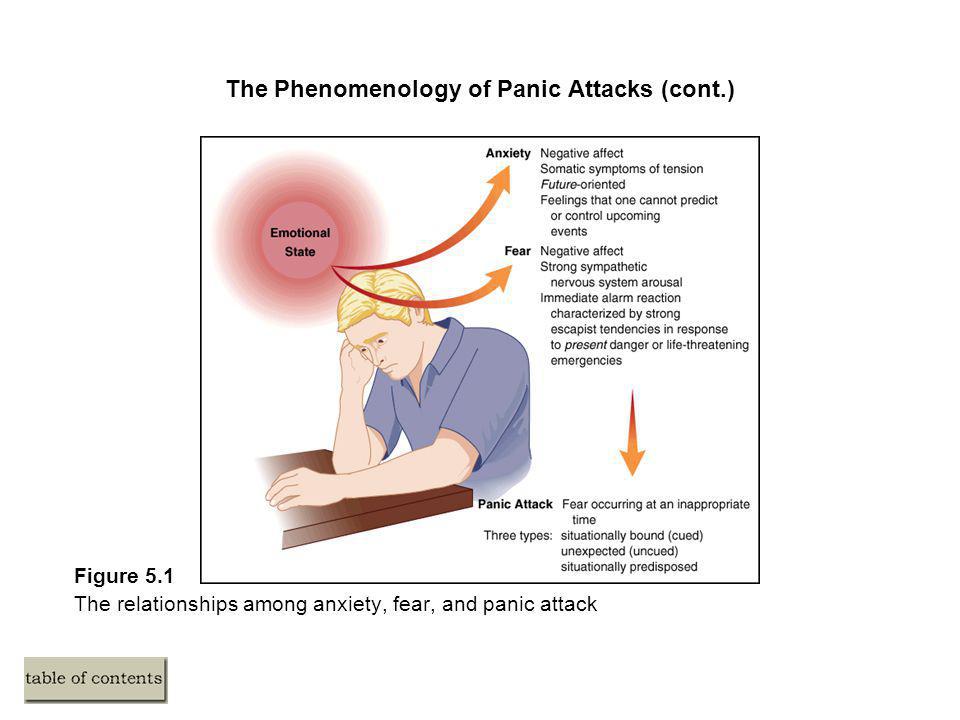

Can Anxiety Cause a Fever?

You're feeling anxiety. You're sweating. You're getting hot and cold flashes. Someone puts their hand to your head and tells you that you're burning up.

Now you're confused. You've always worried that something was wrong – that anxiety was not anxiety at all, but that you're sick and the doctors haven't figured it out yet. Now it appears to be confirmed, since you've developed a fever.

Now it appears to be confirmed, since you've developed a fever.

See a Doctor – Never Assume Anxiety

If you've checked your temperature and you see that you have a fever, or you simply feel ill, see your doctor. Only a doctor can diagnose the cause of a fever and ensure that you're in good health. Even though anxiety causes a lot of different physical problems, anxiety is also generally harmless and a health issue is not. Never be afraid to visit a doctor if you're concerned.

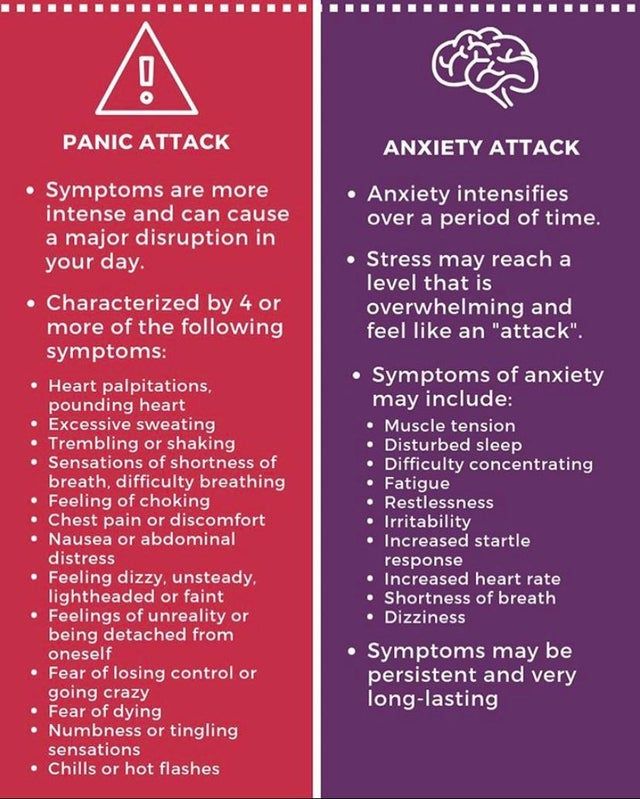

Anxiety and Fever: A Complicated Relationship

The reality is that anxiety does not generally cause a fever. That's not to say it can't – many people report a low grade fever as a result of their anxiety, and stress does have a known impact on the body's ability to fight infections, so it wouldn't be a surprise to find out that stress has, in fact, caused a mild fever in your body.

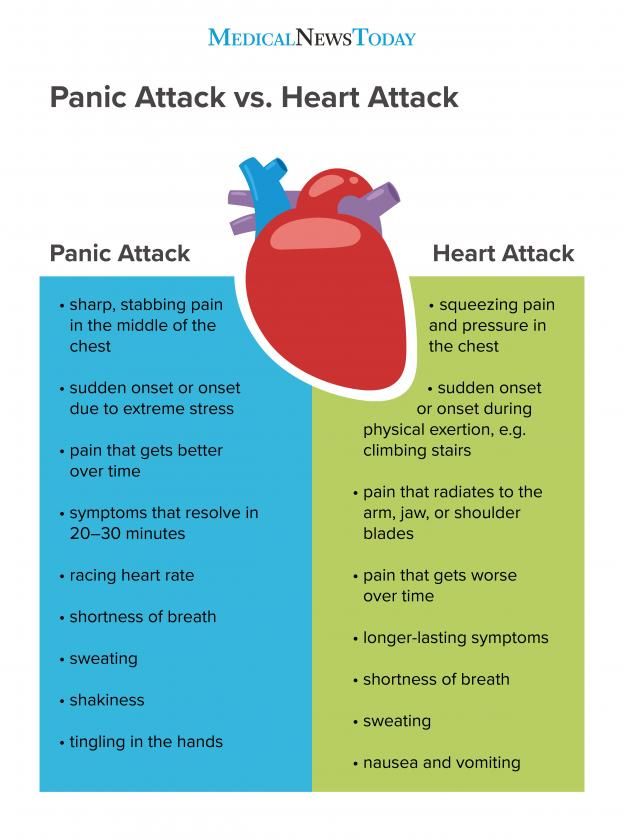

But as far as whether or not that temperature is noteworthy, it is very, very rare for stress to cause anything other than very low grade fever, and body temperature can fluctuate throughout the day. During an intense panic attack, some people have been found to show a 99.5 fahrenheit temperature, but medical professionals are mixed in whether or not they attribute these findings to being directly caused by anxiety.

During an intense panic attack, some people have been found to show a 99.5 fahrenheit temperature, but medical professionals are mixed in whether or not they attribute these findings to being directly caused by anxiety.

So yes, anxiety can in theory cause a fever, but it is not common. Usually when someone reports a fever from anxiety, they're reporting the "feeling" of having a fever without actually testing it. And anxiety does cause fever-like symptoms:

- The feeling of having swollen glands (although they're not usually swollen).

- Extreme hot and cold sensations and fluctuations.

- Nausea, weakness, and general ill feeling.

All of the symptoms of a fever are there, but without the actual fever. Since few people actually check their temperature during a panic attack, most people that think they have a fever are doing so because they're experiencing physical symptoms that resemble a fever.

If you do see a very mild fever that goes away when your anxiety is over, there's no need to panic. You may be one of the few that does develop a fever as a result of your anxiety attack. But it is not that common, which is why anyone that reports a fever – especially if it is over 99.5, or lasts for a long time – should contact a doctor and get the medical attention they need.

You may be one of the few that does develop a fever as a result of your anxiety attack. But it is not that common, which is why anyone that reports a fever – especially if it is over 99.5, or lasts for a long time – should contact a doctor and get the medical attention they need.

Other Potential Links Between Fever and Anxiety

Fever occurs when you're fighting an infection. Those with anxiety are more prone to reacting quickly to any changes in their physical health. It's possible that you are experiencing anxiety because you sense the illness, infection, or symptoms of a fever in ways that other people wouldn't notice until their illness became more pronounced.

Those with allergies, for example, may develop sinusitis (a mild infection) and generate a mild fever as a result. There are ample reasons you may have a mild fever, and while seeking treatment is always important, some of these reasons are harmless. If you're also someone that suffers from anxiety, it's not uncommon to worry that the fever is something more, or that it's linked to your anxiety symptoms. Rest assured that it often won't be, and it's simply a separate issue that needs its own attention.

Rest assured that it often won't be, and it's simply a separate issue that needs its own attention.

What Should You Do If You Feel You Have a Fever?

If you notice that you have a mild fever, you have two options. The best choice is always to contact your doctor. You may also wish to wait for your anxiety to calm down and check your temperature again. If it's really related to an anxiety attack, then it should be gone by the time your anxiety has decreased. If not, it is likely you are fighting off a different infection and may benefit from antibiotics or other medicinal treatments.

If you are someone that is simply experiencing the symptoms of a fever without the fever itself (hot flashes, etc.) then rest assured you are not alone. Many people that suffer from anxiety attacks have bouts of physical symptoms that feel exactly like fighting a fever. Your best bet is to respond to your anxiety attacks directly.

First, take hold of your breathing to make sure that you're not hyperventilating. Hyperventilation drastically increases some of the symptoms that mimic a fever, and can increase your anxiety as well. If you're feeling ill, get up and walk around a bit too. Sometimes taking yourself out of your situation is valuable for controlling the anxiety.

Hyperventilation drastically increases some of the symptoms that mimic a fever, and can increase your anxiety as well. If you're feeling ill, get up and walk around a bit too. Sometimes taking yourself out of your situation is valuable for controlling the anxiety.

Summary:

Severe anxiety may be able to cause short term low grade fever during the peak of a panic attack, but this is typically rare. More common is for an individual to have fever-like symptoms, or to feel additional anxiety when they find themselves with a fever of any kind. Only a doctor can diagnose the cause of a fever, but if you’re struggling with severe anxiety, anxiety reduction will help.

Was this article helpful?

- Yes

- No

Panic attacks - symptoms, causes and treatments

What is a panic attack?

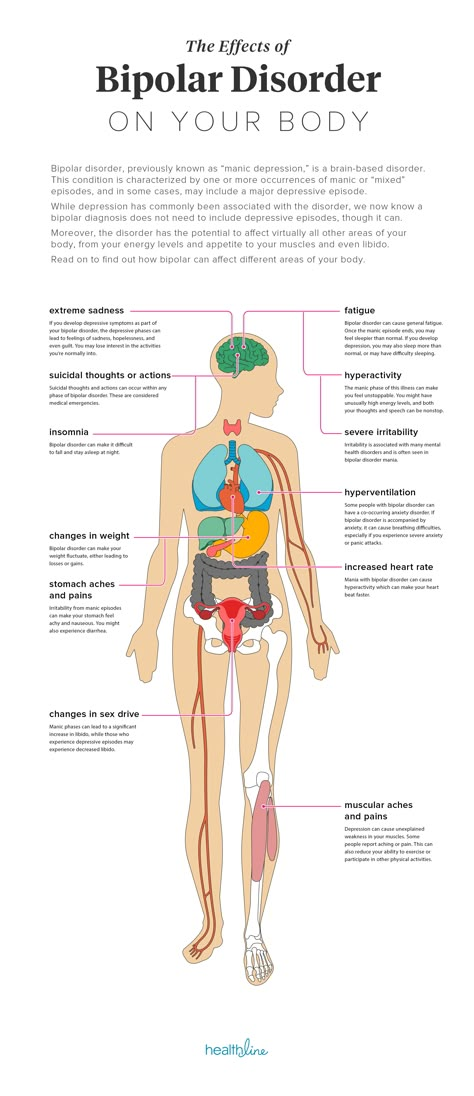

Panic attack is a severe attack of fear and anxiety for no apparent reason, which is accompanied by bodily reactions: rapid heartbeat and pulse, increased pressure, chills or fever, shortness of breath, dizziness.

Seizures can last from a couple of minutes to half an hour, occur suddenly and as if for no reason. You cannot die from a panic attack, but these attacks worsen a person's life and his psychological state.

Why do panic attacks occur?

There are many reasons for panic attacks. An attack can start due to stress, extreme fatigue, or excessive exercise. Causes can also be hormonal disruptions, somatic (i.e. bodily, not mental) diseases or pathologies of the central nervous system. A conflict situation, abuse of alcohol, coffee can provoke an attack. If a person is prone to avoiding negative emotions and is predisposed to a depressive state, he is also at risk.

To find the cause of panic attacks in a particular person, it is worth consulting a doctor. The doctor will take a medical history, prescribe tests and help with the appropriate treatment.

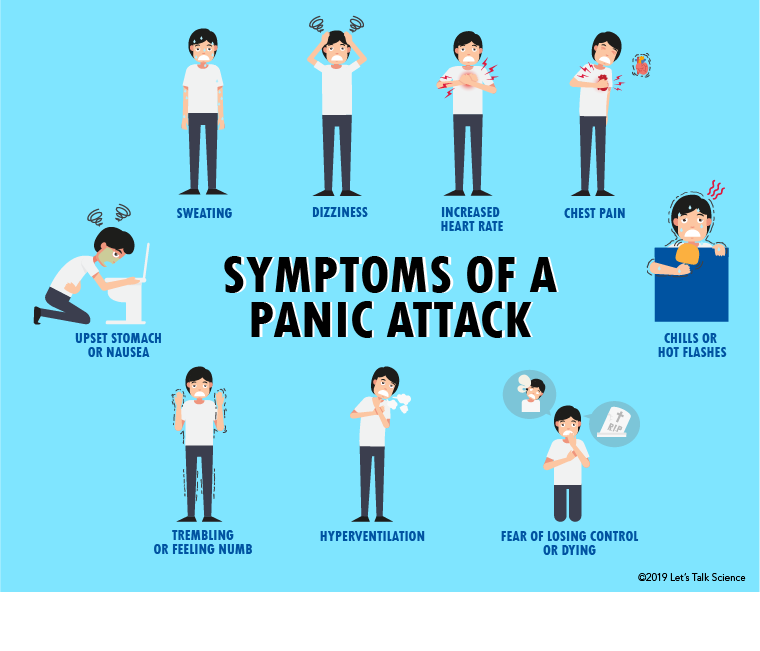

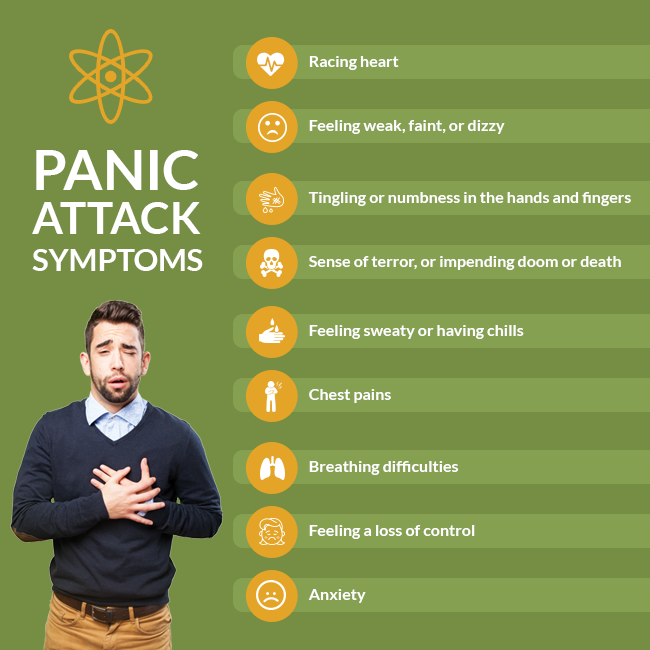

Symptoms of panic attacks

- How does a panic attack start? It becomes difficult to breathe, limbs begin to tremble and darken in the eyes.

- cold sweat;

- feeling of causeless fear and panic;

- chest pain;

- increased heart rate;

- nausea;

- dizziness.

Other symptoms include:

Other symptoms include: If you feel fear or panic and there is a reason for it - for example, before an important exam or job interview, this is normal and understandable. This is how your body reacts to a significant event for you.

Experiencing more than 4 symptoms at the same time without a good reason is most likely the beginning of a panic attack.

Have you experienced similar symptoms of panic attacks and have questions?

Leave your contacts and we will dial you ourselves to answer all questions

Write to

Panic attacks in adolescents

Panic attacks can occur in adolescents in the same way as in adults. The causes of seizures also coincide - stress and strong emotional experiences.

In adolescence, hormonal levels change in adolescents, which makes them less mentally stable. The nervous system undergoes a great load and reacts to it with panic attacks.

The nervous system undergoes a great load and reacts to it with panic attacks.

What to do if a teenager has a panic attack? Take the child by the hand and ask to breathe deeply, offer to drink a glass of water. Explain what's happening - it's an attack, but it will pass, you're safe. Offer to name objects of a certain color or play on the phone to distract.

What to do if a teenager has a panic attack? Take the child by the hand and ask to breathe deeply, offer to drink a glass of water. Explain what's happening - it's an attack, but it will pass, you're safe. Offer to name objects of a certain color or play on the phone to distract.

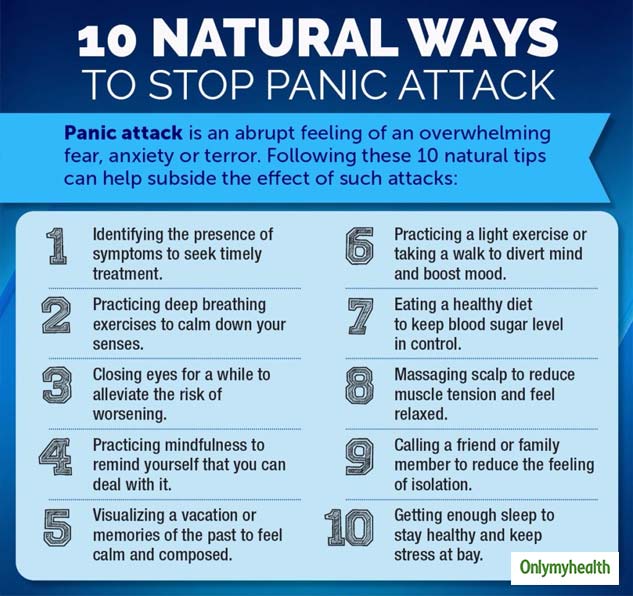

How to deal with panic attacks? 5 Easy Panic Attack Tricks - Neurologist's Tips

- Panic Attack First Aid is a series of simple steps that you can do wherever the attack strikes.

- 1. Breathe. Slow and deep inhalations and exhalations relax the body and help to recover.

- 2. "Ground yourself." Take off your shoes and feel the floor with your feet.

Touch objects with your hands. Pet a cat or dog if they are nearby.

Touch objects with your hands. Pet a cat or dog if they are nearby. - 3. Drink some water.

- 4. Stomp your feet or march in place to help release stress hormones.

- 5. Switch your attention - look around and name 5 objects near you. This will distract you and help you think more calmly.

You can stop an attack yourself. To understand the problem and the causes of panic attacks, we recommend that you consult a doctor. If this is not the first time this has happened, it is imperative to contact a specialist.

What to do in case of a panic attack at night

At night, the human body is relaxed and cannot maintain self-control, so stress seems to “catch up” with the body. Because of this, panic attacks can also occur at night.

To stop a panic attack in the middle of the night, do the following: normalize breathing, drink water, distract yourself.

Panic attacks as a complication after covid

After the coronavirus, the human body is severely depleted. In addition, isolation, uncertainty, economic difficulties have become a test that people have been struggling with for a long time. Panic attacks appear as one of the consequences of COVID-19as a reaction to stress and excessive emotional stress.

In addition, isolation, uncertainty, economic difficulties have become a test that people have been struggling with for a long time. Panic attacks appear as one of the consequences of COVID-19as a reaction to stress and excessive emotional stress.

How to treat panic attacks after covid? You can stop the attack with the help of the already described actions - breathing, switching attention.

Since the body is weakened after an illness, it is not recommended to postpone a visit to a specialist. The doctor will determine the possible causes and help choose the treatment so as not to aggravate the condition of a person who has been ill with COVID-19.

Panic attacks: treatment in Kyiv

To start treating panic attacks, you need to contact a doctor - a neurologist and an endocrinologist. Doctors will ask the patient about complaints and prescribe the necessary tests to rule out other diseases that cause similar symptoms.

Diagnosis is carried out by specialists from the Time+ Clinic for Neurology and Orthopedics. To find out the cause of panic attacks, an MRI of the brain (head), ultrasound of the vessels of the head and neck are done.

To find out the cause of panic attacks, an MRI of the brain (head), ultrasound of the vessels of the head and neck are done.

The Time+ clinic employs professionals and has all the necessary equipment to deal with the problem of panic attacks and help the patient.

Make an appointment

Neurologist

Work experience in the specialty 14 years, the highest certification category .

Neurologist

Specialization: back pain, migraine.

"For patients with Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease, I prescribe pharmacotherapy according to the latest international protocols. I am a supporter of the use of a minimum number of drugs, I focus on individual rehabilitation programs and a systematic approach."

✔Surgical treatment of panic attacks in Chita

A panic attack is an anxiety attack that cannot be explained.

Treatment of panic attacks requires immediate action. Timely referral to a psychotherapist. As a rule, treatment is accompanied by taking certain drugs after diagnosing the causes that provoked a panic attack.

The Recovery Clinic has everything you need to help a patient suffering from anxiety attacks:

- Inpatient department;

- Specialists in the field;

- Clinical laboratory;

- Medicines

Panic attack treatment in Chita

In Murmansk, the number of requests for panic attack treatment has recently increased. With what this is connected, it is rather difficult to say. But, as with any disease, first of all, you need to seek help from a doctor.

It is very important to track down a panic attack in time and immediately go for a consultation with a psychotherapist, otherwise you can look for a problem in the kidneys or heart for a very long time. A false diagnosis leads to the fact that a person begins to take drugs that he does not need at all and gradually becomes a hypochondriac.

If the course of treatment is not started on time, then panic attacks will intensify, and the intervals between them will decrease, the person will constantly expect them. Then the development of a disease such as panic disorder is possible. The danger of panic disorder is in constant relapses and the inability to control one's behavior.

When contacting the clinic, drugs are prescribed:

- Paroxetine;

- Tranquilizers;

- Benzodiazepines

Psychotherapy is dominated by the cognitive-behavioral method. The psychotherapist proceeds from the assumption that a mental disorder is associated with destructive thoughts and stereotypes of the patient's behavior.

The doctor may advise the patient to master the "stop thought" method. It takes about seven days to master the technique.

Panic attack, treatment

During a panic attack, fear and somatic symptoms predominate:

- Palpitations;

- Hand tremor;

- Excessive sweating;

- Chill;

- Choking, feeling short of breath;

- Whole body fever;

- Chest pain;

- Numbness of the body;

- No sleep;

- Pain in the abdomen

If the patient's anxiety is accompanied by an inexplicable fear, as well as several items from the list of symptoms, then a panic attack can be diagnosed.

It is worth remembering that an anxiety attack, fear are also symptoms of some other mental illness, such as depression or phobia. Also, a panic attack indicates the presence of problems with the vegetative-vascular system.

For a panic attack that progresses, it is characteristic that the level of fear decreases. Internal tension intensifies, however, there is no fear.

In addition to a sudden panic attack, there is a situational one. That is, a person suddenly cannot be in the crowd or he urgently needs to leave the apartment.

Treat a panic attack as soon as the first symptoms appear.

How to cure a panic attack?

It is possible to cure a panic attack quite quickly, provided that its cause is diagnosed in time. As well as an immediate course of medication and sessions with a psychologist. There is no point in fighting panic attacks on your own.

Therapy can be done at home or in a day hospital setting, whichever is considered more effective. Constant observation by the psychotherapist of the patient's condition will help to correct the treatment in time.

Constant observation by the psychotherapist of the patient's condition will help to correct the treatment in time.

Prices for the treatment of mental disorders | |||

| Schizophrenia | from 2970 rubles (day) | from 10 days | Order |

| Panic attacks | from 2970 rubles (day) | from 10 days | Order |

| Insomnia | from 2970 rub (day) | from 7 days | Order |

| Psychosomatics | from 2970 rubles (day) | from 7 days | Order |

| Neuroses | from 2970 rubles (day) | from 7 days | Order |

| Depression | from 2970 rubles (day) | from 7 days | Order |

| Psychosis | from 2970 rubles (day) | from 7 days | Order |

| Anorexia | from 2970 rubles (day) | from 7 days | Order |

| Bulimia | from 2970 rubles (day) | from 7 days | Order |

| Alcoholism and drug addiction in dual diagnosis | from 4970 rubles (per day) | from 10 days | Order |

Sign up for a consultation With a psychotherapist Turning to us you will be sure of solving your problem

Your name

Your phone

*Your information will remain confidential.