Bipolar 5 year old symptoms

NIMH » Bipolar Disorder in Children and Teens

Does your child go through extreme changes in mood and behavior? Does your child get much more excited or much more irritable than other kids? Do you notice that your child goes through cycles of extreme highs and lows more often than other children? Do these mood changes affect how your child acts at school or at home?

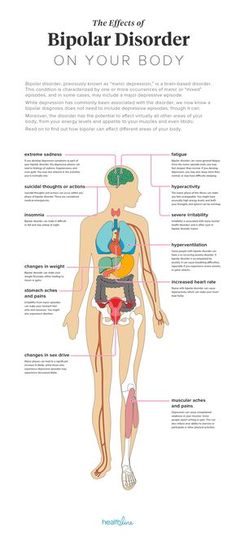

Some children and teens with these symptoms may have bipolar disorder, a brain disorder that causes unusual shifts in mood, energy, activity levels, and day-to-day functioning. With treatment, children and teens with bipolar disorder can get better over time.

What is bipolar disorder?

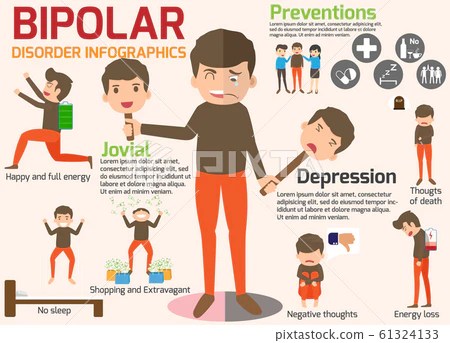

Bipolar disorder is a mental disorder that causes people to experience noticeable, sometimes extreme, changes in mood and behavior. Sometimes children with bipolar disorder feel very happy or “up” and are much more energetic and active than usual.

This is called a manic episode. Sometimes children with bipolar disorder feel very sad or “down” and are much less active than usual. This is called a depressive episode.

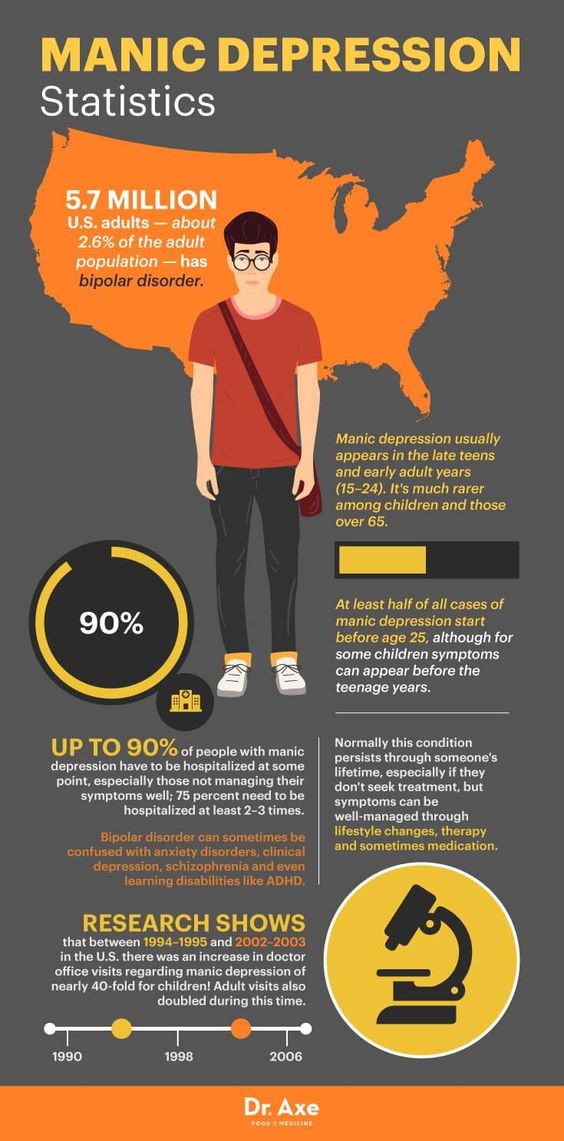

Bipolar disorder, which used to be called manic-depressive illness or manic depression, is not the same as the normal ups and downs every child goes through. The mood changes in bipolar disorder are more extreme, often unprovoked, and accompanied by changes in sleep, energy level, and the ability to think clearly. Bipolar symptoms can make it hard for young people to perform well in school or to get along with friends and family members. Some children and teens with bipolar disorder may try to hurt themselves or attempt suicide.

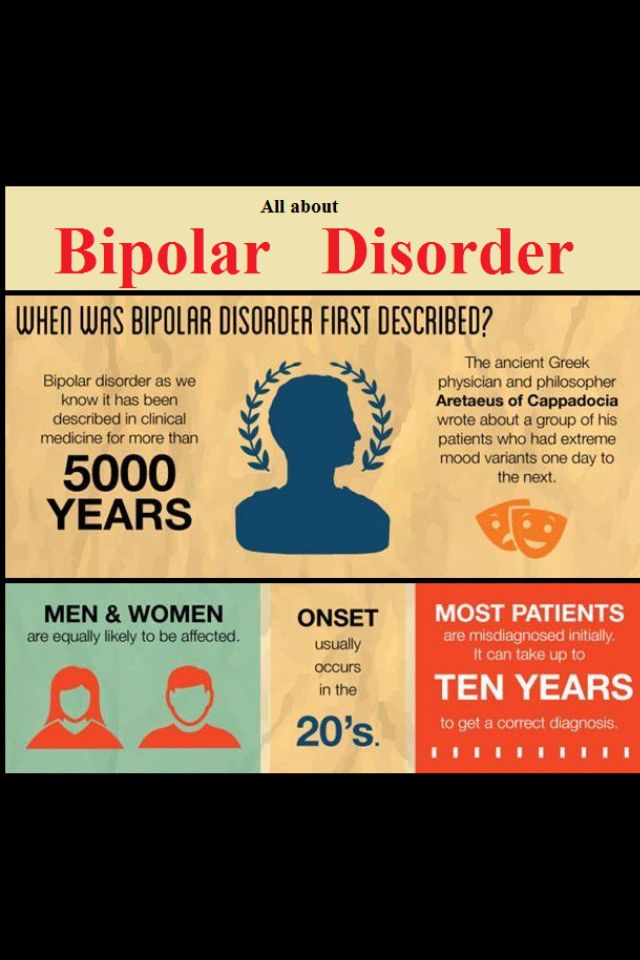

Most people are diagnosed with bipolar disorder in adolescence or adulthood, but the symptoms can appear earlier in childhood. Bipolar disorder is often episodic, but it usually lasts a lifetime.

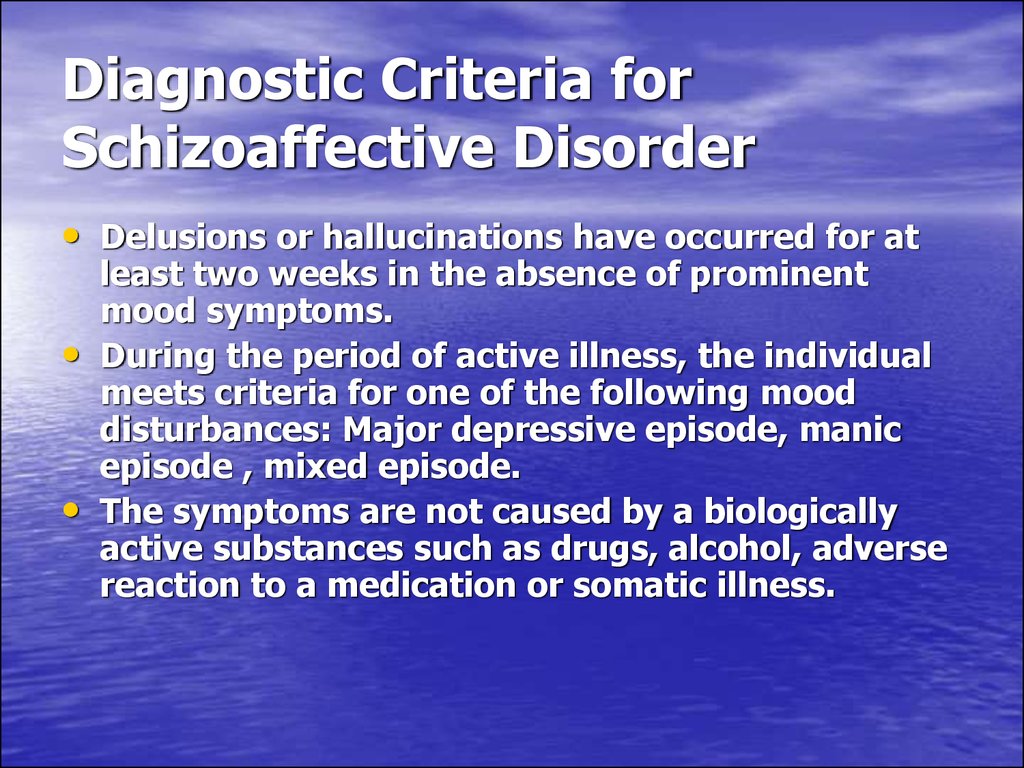

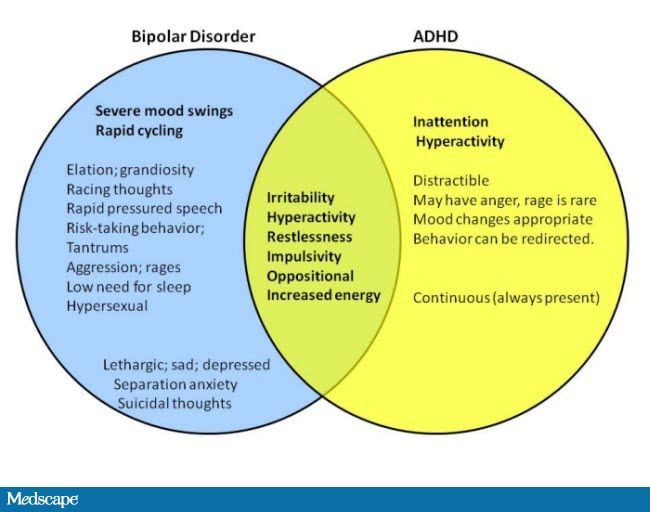

Signs and symptoms of bipolar disorder may overlap with symptoms of other disorders that are common in young people, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct problems, major depression, and anxiety disorders. Diagnosing bipolar disorder can be complicated and requires a careful and thorough evaluation by a trained, experienced mental health professional.

Diagnosing bipolar disorder can be complicated and requires a careful and thorough evaluation by a trained, experienced mental health professional.

With treatment, children and teens with bipolar disorder can manage their symptoms and lead successful lives.

What causes bipolar disorder?

The exact causes of bipolar disorder are unknown, but several factors may contribute to the illness.

For example, researchers are beginning to uncover genetic mechanisms that are linked to bipolar disorder and other mental disorders. Research shows that people’s chance of having bipolar disorder is higher if they have a close family member with the illness, which may be because they have the same genetic variations. However, just because one family member has bipolar disorder, it does not mean that other members of the family will have it. Many genes are involved in the disorder, and no single gene causes it.

Research also suggests that adversity, trauma, and stressful life events may increase the chances of developing bipolar disorder in people with a genetic risk of having the illness.

Some research studies have found differences in brain structure and function between people who have bipolar disorder and those who do not. Researchers are studying the disorder to learn more about its causes and effective treatments.

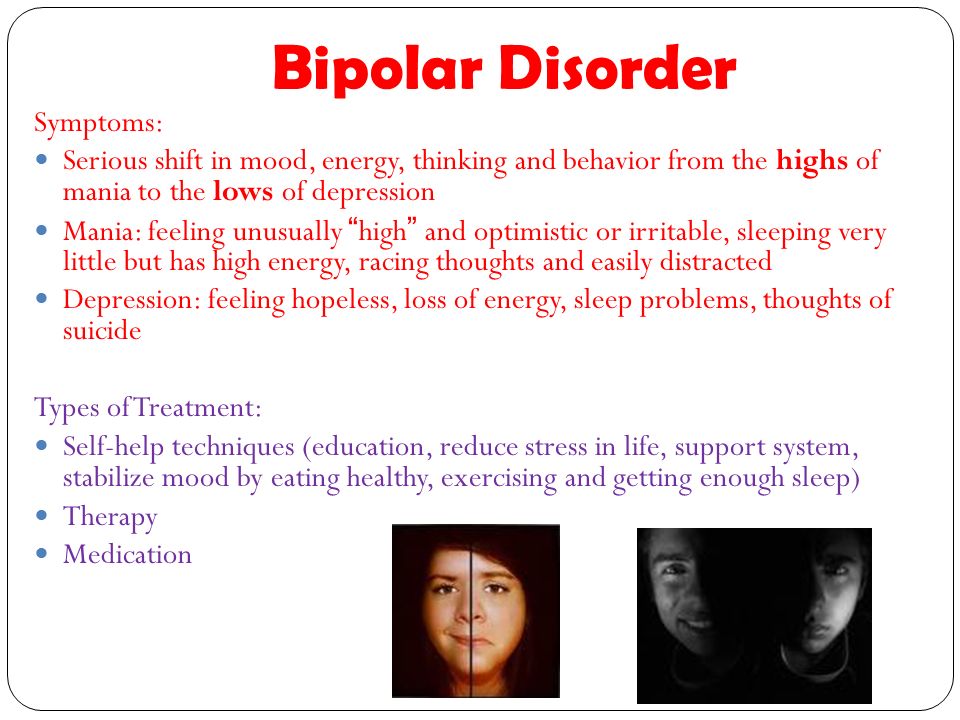

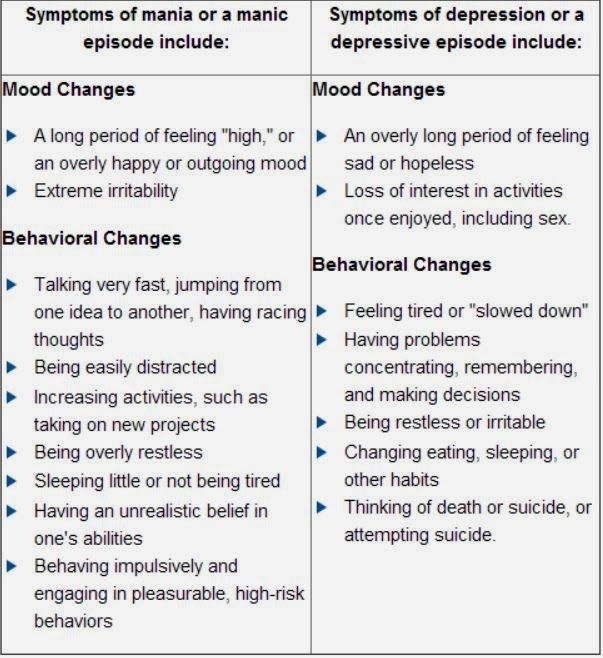

What are the symptoms of bipolar disorder?

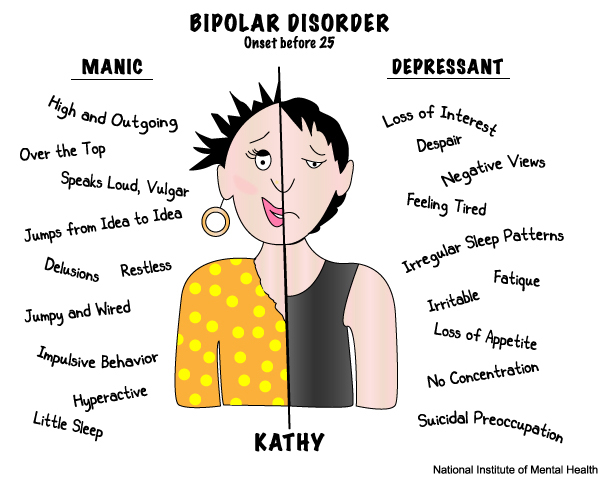

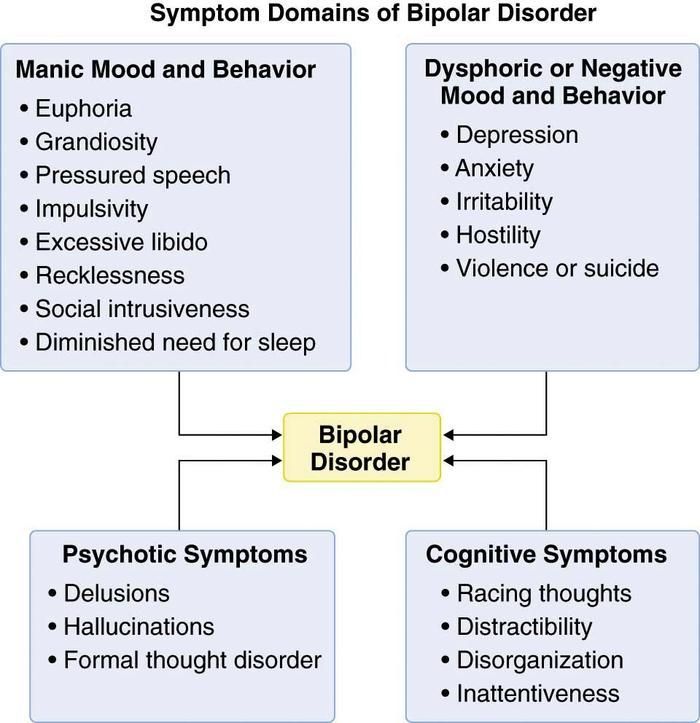

Mood episodes in bipolar disorder include intense emotions along with significant changes in sleep habits, activity levels, thoughts, or behaviors. A person with bipolar disorder may have manic episodes, depressive episodes, or “mixed” episodes. A mixed episode has both manic and depressive symptoms. These mood episodes cause symptoms that often last for several days or weeks. During an episode, the symptoms last every day for most of the day.

These mood and activity changes are very different from the child’s usual behavior and from the behavior of healthy children and teens.

Children and teens having a manic episode may:

- Show intense happiness or silliness for long periods of time.

- Have a very short temper or seem extremely irritable.

- Talk fast about a lot of different things.

- Have trouble sleeping but not feel tired.

- Have trouble staying focused, and experience racing thoughts.

- Seem overly interested or involved in pleasurable but risky activities.

- Do risky or reckless things that show poor judgment.

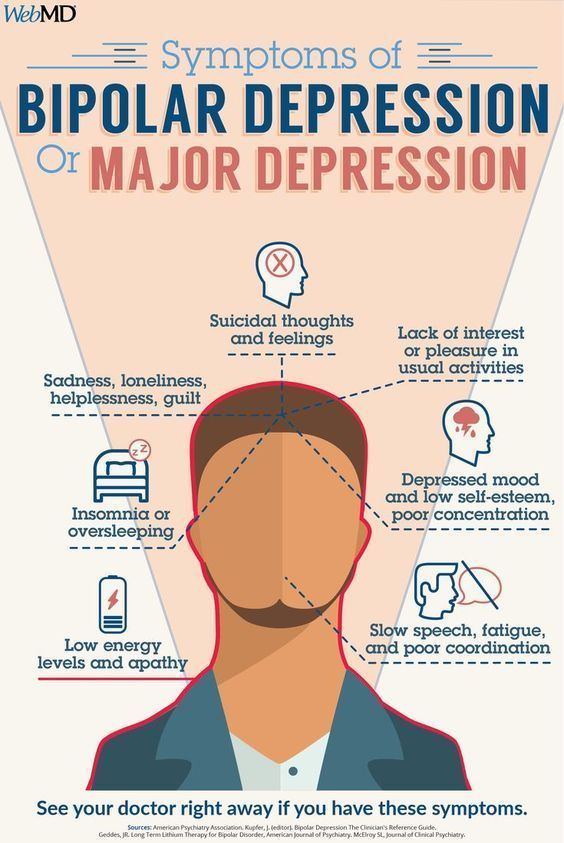

Children and teens having a depressive episode may:

- Feel frequent and unprovoked sadness.

- Show increased irritability, anger, or hostility.

- Complain a lot about pain, such as stomachaches and headaches.

- Have a noticeable increase in amount of sleep.

- Have difficulty concentrating.

- Feel hopeless and worthless.

- Have difficulty communicating or maintaining relationships.

- Eat too much or too little.

- Have little energy and no interest in activities they usually enjoy.

- Think about death, or have thoughts of suicide.

Can children and teens with bipolar disorder have other problems?

Young people with bipolar disorder can have several problems at the same time. These include:

- Misuse of alcohol and drugs. Young people with bipolar disorder are at risk of misusing alcohol or drugs.

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Children and teens who have both bipolar disorder and ADHD may have trouble staying focused.

- Anxiety disorders. Children and teens with bipolar disorder also may have an anxiety disorder.

Sometimes extreme behaviors go along with mood episodes. During manic episodes, young people with bipolar disorder may take extreme risks that they wouldn’t usually take or that could cause them harm or injury. During depressive episodes, some young people with bipolar disorder may think about running away from home or have thoughts of suicide.

If your child shows signs of suicidal thinking, take these signs seriously and call your child’s health care provider.

If you think your child is in crisis and needs immediate help, call 911. You also can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (Lifeline) at 1‑800‑273‑TALK (8255), or text the Crisis Text Line (text HELLO to 741741). These services are confidential, free, and available 24/7.

How is bipolar disorder diagnosed?

A health care provider will ask questions about your child’s mood, sleeping patterns, energy levels, and behavior. There are no blood tests or brain scans that can diagnose bipolar disorder. However, the health care provider may use tests to see if something other than bipolar disorder is causing your child’s symptoms. Sometimes health care providers need to know about medical conditions in the family, such as depression or substance use.

Other disorders have symptoms like those of bipolar disorder, including ADHD, disruptive mood regulation disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and anxiety disorders. It also can be challenging to distinguish bipolar disorder from depression that occurs without mania, which is referred to as “major depression.” A health care provider who specializes in working with children and teens can make a careful and complete evaluation of your child’s symptoms to provide the right diagnosis.

It also can be challenging to distinguish bipolar disorder from depression that occurs without mania, which is referred to as “major depression.” A health care provider who specializes in working with children and teens can make a careful and complete evaluation of your child’s symptoms to provide the right diagnosis.

How is bipolar disorder treated?

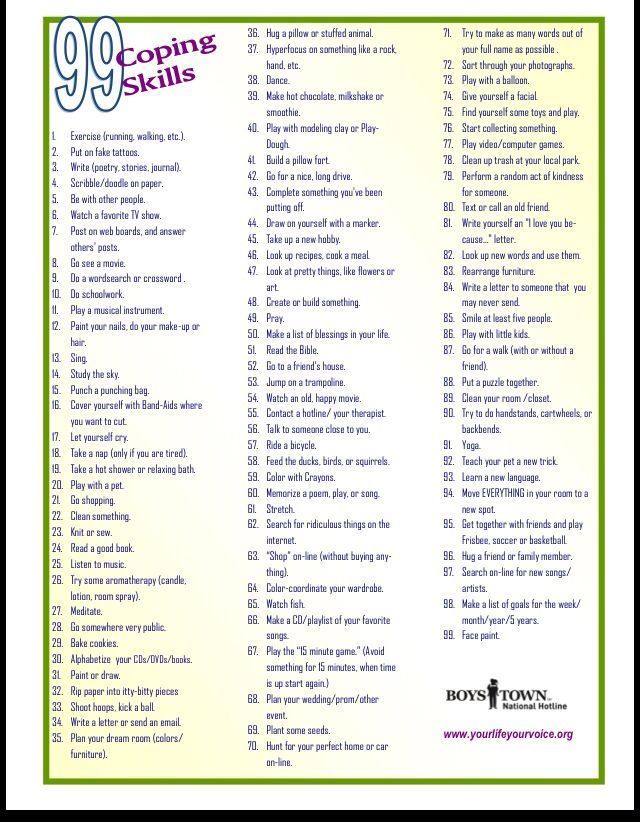

Children and teens can work with their health care provider to develop a treatment plan that will help them manage their symptoms and improve their quality of life. It is important to follow the treatment plan, even when your child is not currently experiencing a mood episode. Steady, dependable treatment works better than treatment that starts and stops.

Treatment options include:

- Medication. Several types of medication can help treat symptoms of bipolar disorder. Children respond to medications in different ways, so the right type of medication depends on the child.

This means children may need to try different types of medication to see which one works best for them. Some children may need more than one type of medication because their symptoms are complex. Children should take the fewest number of medications and the smallest doses possible to help their symptoms. A good way to remember this is “start low, go slow.” Medications can cause side effects. Always tell your child’s health care provider about any problems with side effects. Do not stop giving your child medication without speaking to a health care provider. Stopping medication suddenly can be dangerous and can make bipolar symptoms worse.

This means children may need to try different types of medication to see which one works best for them. Some children may need more than one type of medication because their symptoms are complex. Children should take the fewest number of medications and the smallest doses possible to help their symptoms. A good way to remember this is “start low, go slow.” Medications can cause side effects. Always tell your child’s health care provider about any problems with side effects. Do not stop giving your child medication without speaking to a health care provider. Stopping medication suddenly can be dangerous and can make bipolar symptoms worse. - Psychosocial Therapy. Different kinds of psychosocial therapy can help children and their families manage the symptoms of bipolar disorder. Therapies that are based on scientific research—including cognitive behavioral approaches and family-focused therapy—can provide support, education, and guidance to youth and their families.

These therapies teach skills that can help people manage bipolar disorder, including skills for maintaining routines, enhancing emotion regulation, and improving social interactions.

These therapies teach skills that can help people manage bipolar disorder, including skills for maintaining routines, enhancing emotion regulation, and improving social interactions.

What can children and teens expect from treatment?

With treatment, children and teens with bipolar disorder can get better over time. Treatment is more effective when health care providers, parents, and young people work together.

Sometimes a child’s symptoms may change, or disappear and then come back. When this happens, your child’s health care provider may recommend changes to the treatment plan. Treatment can take time, but sticking with the treatment plan can help young people manage their symptoms and reduce the likelihood of future episodes.

Your child’s health care provider may recommend keeping a daily life chart or mood chart to track your child’s moods, behaviors, and sleep patterns. This may make it easier to track the illness and see whether treatment is working.

How can I help my child or teen?

Help begins with the right diagnosis and treatment. Talk to your family health care provider about any symptoms you notice.

If your child has bipolar disorder, here are some basic things you can do:

- Be patient.

- Encourage your child to talk, and listen to your child carefully.

- Pay attention to your child’s moods, and be alert to any major changes.

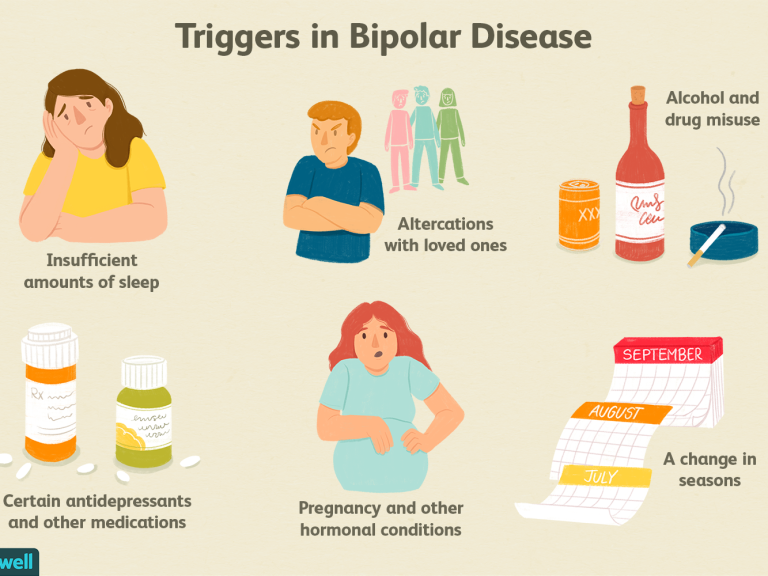

- Understand triggers, and learn strategies for managing intense emotions and irritability.

- Help your child have fun.

- Remember that treatment takes time: sticking with the treatment plan can help your child get better and stay better.

- Help your child understand that treatment can make life better.

How does bipolar disorder affect caregivers and families?

Caring for a child or teenager with bipolar disorder can be stressful for parents and families. Coping with a child’s mood episodes and other problems—such as short tempers and risky behaviors—can challenge any caregiver.

Coping with a child’s mood episodes and other problems—such as short tempers and risky behaviors—can challenge any caregiver.

It is important that caregivers take care of themselves, too. Find someone you can talk to or consult your health care provider about support groups. Finding support and strategies for managing stress can help you and your child.

Where do I go for help?

If you’re not sure where to get help, your doctor, pediatrician, or other family health care provider is a good place to start. A health care provider can refer you to a qualified mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist or psychologist, who has experience treating bipolar disorder and can evaluate your child’s symptoms.

You can learn more about getting help and finding a health care provider on the National Institute of Mental Health website. Hospital health care providers can help in an emergency. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has an online tool to help you find mental health services in your area.

I know someone who is in crisis. What do I do?

If you know someone who might be thinking about hurting themselves or someone else, get help quickly.

- Do not leave the person alone.

- Call 911 or go to the nearest hospital emergency room.

- Call the toll-free National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or the toll-free TTY number at 1-800-799-4TTY (4889). You also can text the Crisis Text Line (text HELLO to 741741) or go to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline website.

What should I know about clinical trials?

Clinical trials are research studies that look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge so that others may be better helped in the future.

Researchers at NIMH and around the country conduct clinical trials with patients and healthy volunteers. Talk to your health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you. For more information, visit the NIMH Clinical Trials webpage.

Reprints

This publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission from NIMH. Citation of NIMH as a source is appreciated. To learn more about using NIMH publications, please contact the NIMH Information Resource Center at 1-866‑615‑6464, email [email protected], or refer to our reprint guidelines.

For More Information

MedlinePlus (National Library of Medicine) (En español)

ClinicalTrials.gov (En español)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

National Institutes of Health

NIH Publication No. 20-MH-8081

Revised 2020

Bipolar Symptoms in Children: Signs and Behaviors

Bipolar is a brain disorder that causes unusual, extreme shifts in mood, energy, and day-to-day functioning. Until a few decades ago, it was widely believed that only adults could have bipolar disorder. Studies conducted since then indicate that many adults with the disorder did exhibit symptoms in childhood. In fact, about 30 percent of adults with bipolar disorder report experiencing symptom onset before the age of 13.1 One study estimates an overall prevalence of 1.8% of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents.2

Until a few decades ago, it was widely believed that only adults could have bipolar disorder. Studies conducted since then indicate that many adults with the disorder did exhibit symptoms in childhood. In fact, about 30 percent of adults with bipolar disorder report experiencing symptom onset before the age of 13.1 One study estimates an overall prevalence of 1.8% of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents.2

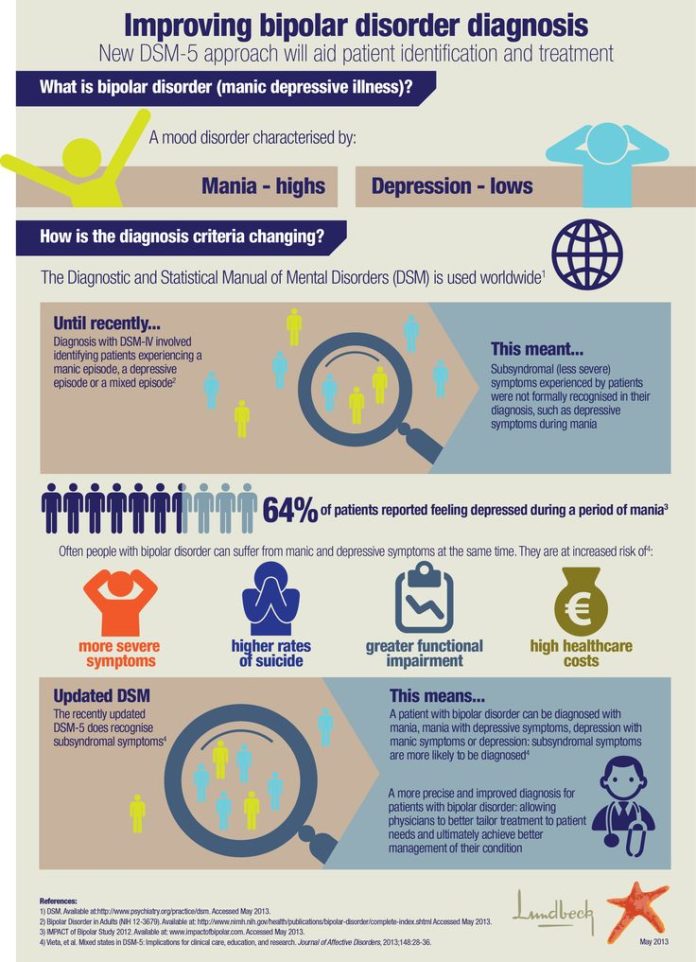

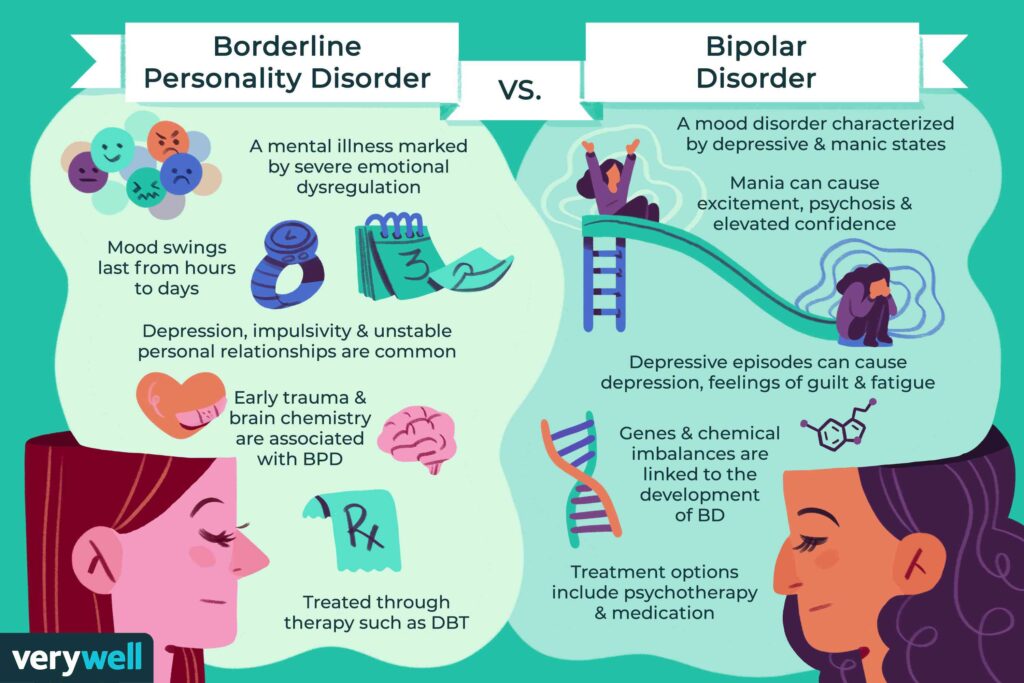

Core bipolar symptoms include manic episodes, where the individual is abnormally and persistently elated and energetic for weeks on end, and the opposite: depressive episodes. The clinical presentation of bipolar disorder in children, while controversial, is significantly different than it is in adults. A lack of child-specific criteria in the DSM-5 is one reason for the diagnostic challenges in identifying pediatric bipolar disorder.

[Self-Test: Does My Child Have Bipolar Disorder?]

Bipolar Symptoms in Children: Presentation

Every child’s symptoms differ, but during a manic phase, you may see signs like:

- Acting hyper, exuberantly happy, or incredibly silly behavior — seemingly at random and in a way that is unusual to the child’s personality

- Talking quickly or switching topics mid-sentence (seemingly without noticing)

- Hyperfocusing on a single subject or project that seems to come out of nowhere

- Erupting in extreme upset when obstacles arise or they are told “no”

- Highly imaginative; coming up with complex storylines

- Angering quickly and becoming violent over small slights

- Not feeling tired or requiring much sleep, and showing little interest in napping, resting, or going to bed at night; getting up frequently during the night

- Becoming preoccupied with sex or sexual thoughts; talking about sex at inappropriate times

- Acting on sexual desires in public, dangerous, or age-inappropriate ways; masturbating excessively or engaging in risky sex at a young age

- Seeing or hearing things that aren’t there

[10 Myths (and Truths) About Bipolar Disorder]

During a depressive phase, you might see symptoms like:

- Acting unusually weepy and sad

- Complaining of frequent stomachaches and headaches

- Sleeping longer than usual

- Eating too little or too much; might gain or lose weight very rapidly

- Showing little interest in regular activities

- Talking about being a “bad” child, or wondering aloud if everyone hates them

- Becoming preoccupied with death; talking about suicide or, for very young children, how it would be better for everyone if they “went away forever” or “were never born”

Symptoms of Pediatric Bipolar at School

Bipolar disorder will sometimes look a little different at school, where your child is around peers and adults to whom they are not related. During a manic phase, symptoms at school might include:

During a manic phase, symptoms at school might include:

- Appearing at times to be a “social butterfly;” making new friends easily and charming adults with a “precocious” personality

- Acting overly bossy with friends; getting irrationally upset over slight disagreements or friends not taking orders

- Disobeying teachers and other authority figures; acting “out of control;” exhibiting excessive hyperactivity

- Behaving inappropriately — removing clothing in the classroom or singing loudly during class

- Being unable to sleep during naptime or settle down to quietly read

- Being unable to make transitions; becoming upset or violent when unwelcome change occurs

- Difficulty focusing on schoolwork; often seeming unable to sit still

- Jumping between acting “goofy” — even when other students aren’t playing along — to being angry and aggressive, often with seemingly no provocation

- Acting in ways that are dangerously impulsive; throwing themselves off the jungle gym, climbing the highest tree, or trying to “escape” from school, for instance

[Watch Out! Doctors Mistake Bipolar Disorder for ADHD]

During a depressive phase, you might see signs at school like:

- Becoming uninterested in friends or regular playtime activities; sitting alone during recess instead of joining in the fun

- Demonstrating antisocial behavior or developing a fear of classmates; suddenly clinging to parent’s leg when being dropped off, for instance

- Believing that nobody likes him

- Complaining about aches and pains to the teacher frequently; often asking to be excused to the nurse’s office or picked up by a parent

- Becoming fixated on death, often bringing it up to other students or to the teacher

- Being unable to focus on schoolwork; seeming “zoned out”

For most children with bipolar disorder, the cycling between mania and depression occurs at a much more rapid pace than it would for adults. While it’s common for cycles to happen over the course of weeks, months, or years for adults, in extreme cases, your child may cycle between these different symptoms several times in one day.

While it’s common for cycles to happen over the course of weeks, months, or years for adults, in extreme cases, your child may cycle between these different symptoms several times in one day.

Pediatric Bipolar Disorder vs. ADHD

ADHD and bipolar disorder share similar symptoms including impulsivity, irritability, and hyperactivity, among others. ADHD and bipolar disorder commonly co-occur, but rates of comorbidity vary considerably across studies. This dynamic explains why a careful differential diagnosis (where a doctor differentiates between conditions that could explain a child’s symptoms) is crucial:

- ADHD symptoms tend to appear in early childhood, whereas bipolar disorder typically develops later in childhood.

- As the child progresses through school, increased academic demands can exacerbate ADHD symptoms, which should not be confused for the start of the mood disorder.3

- A child with ADHD may exhibit disinhibited behavior – not to be confused with the elated mood bipolar disorder can bring 3

- Children with ADHD may resist bedtime, whereas children with bipolar disorder (especially during manic episodes) may have a reduced need for sleep.

4

4 - Family history of mood disorders is important, as bipolar disorder has a clear genetic component.3 When one parent has bipolar disorder, the risk to each child is 15 to 30 percent.1

View Article Sources

1 Singh T. (2008). Pediatric bipolar disorder: diagnostic challenges in identifying symptoms and course of illness. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa. : Township)), 5(6), 34–42.

2 Van Meter, A. R., Moreira, A. L., & Youngstrom, E. A. (2011). Meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies of pediatric bipolar disorder. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 72(9), 1250–1256. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10m06290

3Carlson GA. Differential diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. World Psychiatry. 2012;11(3):146-152. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2012.tb00115.x

4Harvey AG, Talbot LS, Gershon A. Sleep Disturbance in Bipolar Disorder Across the Lifespan. Clin Psychol (New York). 2009;16(2):256-277. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01164.x

Clin Psychol (New York). 2009;16(2):256-277. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01164.x

Previous Article Next Article

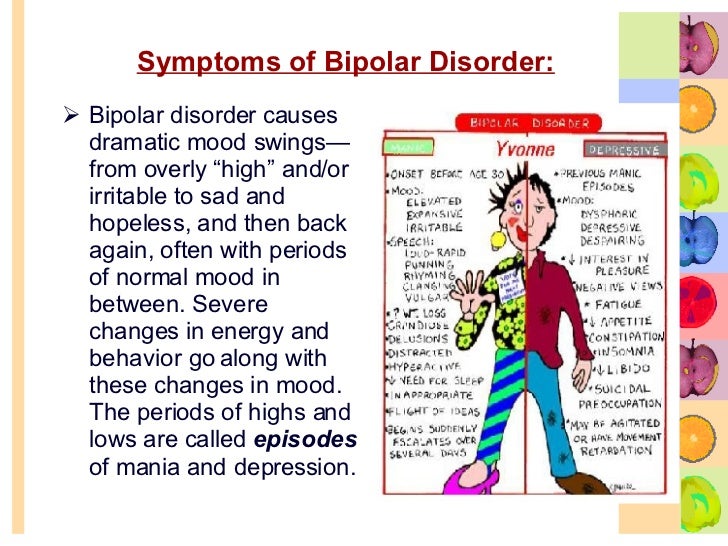

Bipolar Disorder | Symptoms, complications, diagnosis and treatment

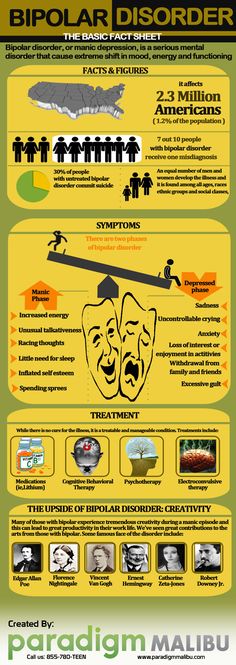

Bipolar disorder, formerly called manic depression, is a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression). Episodes of mood swings may occur infrequently or several times a year.

When you become depressed, you may feel sad or hopeless and lose interest or pleasure in most activities. When the mood shifts to mania or hypomania (less extreme than mania), you may feel euphoric, full of energy or unusually irritable. These mood swings can affect sleep, energy, alertness, judgment, behavior, and the ability to think clearly.

Although bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition, you can manage your mood swings and other symptoms by following a treatment plan. In most cases, bipolar disorder is treated with medication and psychological counseling (psychotherapy).

In most cases, bipolar disorder is treated with medication and psychological counseling (psychotherapy).

Symptoms

There are several types of bipolar and related disorders. They may include mania, hypomania, and depression. The symptoms can lead to unpredictable changes in mood and behavior, leading to significant stress and difficulty in life.

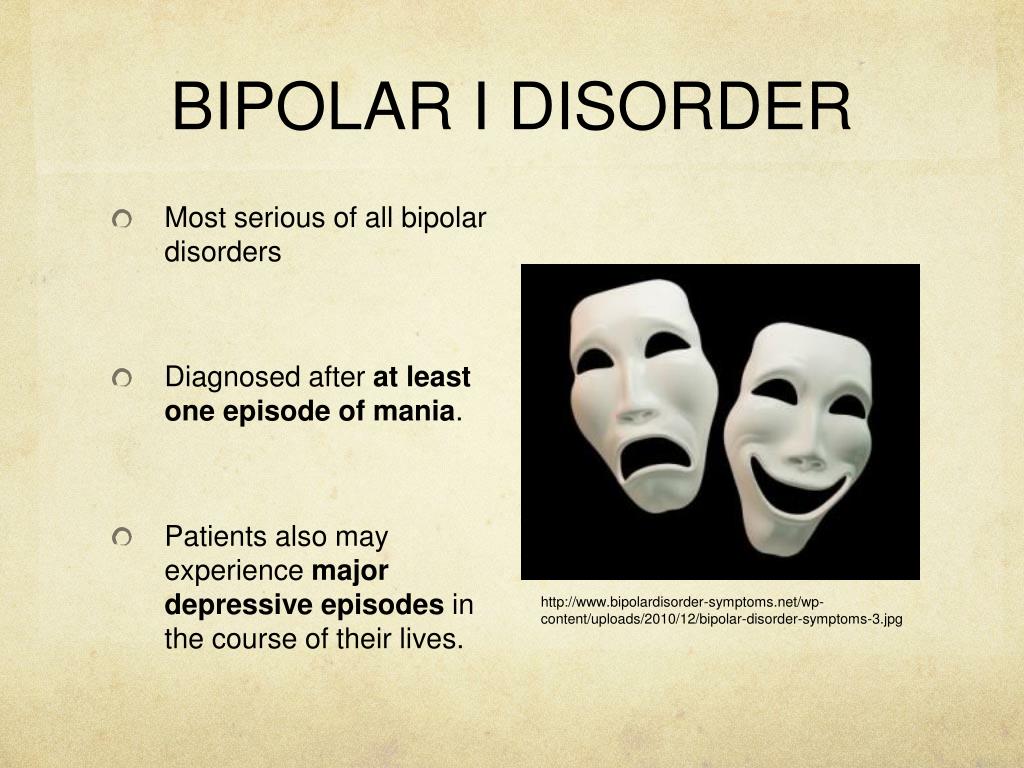

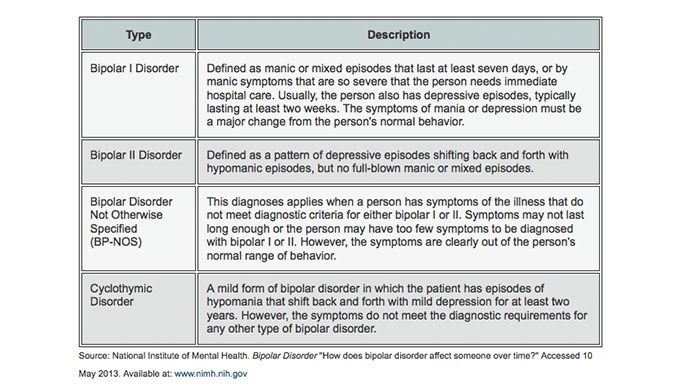

- Bipolar disorder I. You have had at least one manic episode, which may be preceded or accompanied by hypomanic or major depressive episodes. In some cases, mania can cause a break with reality (psychosis).

- Bipolar disorder II. You have had at least one major depressive episode and at least one hypomanic episode, but never had a manic episode.

- Cyclothymic disorder. You have had at least two years - or one year in children and adolescents - many periods of hypomanic symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms (though less severe than major depression).

- Other types. These include, for example, bipolar and related disorders caused by certain drugs or alcohol, or due to health conditions such as Cushing's disease, multiple sclerosis, or stroke.

Bipolar II is not a milder form of Bipolar I but is a separate diagnosis. Although bipolar I manic episodes can be severe and dangerous, people with bipolar II can be depressed for longer periods of time, which can cause significant impairment.

Although bipolar disorder can occur at any age, it is usually diagnosed in adolescence or early twenties. Symptoms can vary from person to person, and symptoms can change over time.

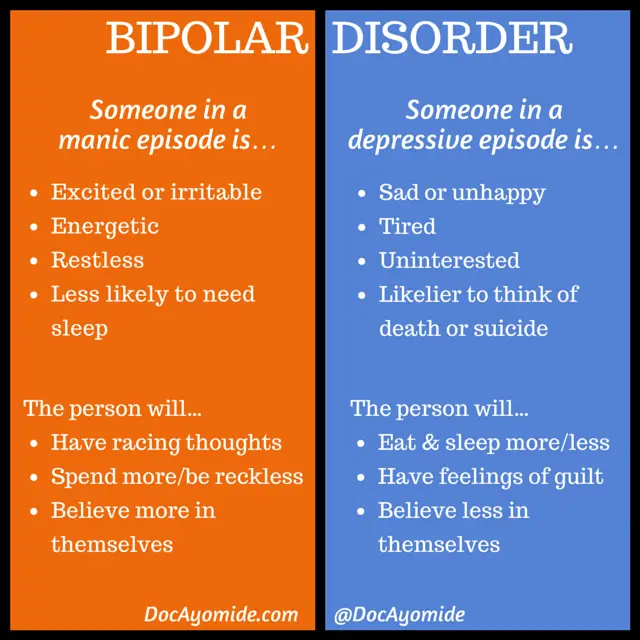

Mania and hypomania

Mania and hypomania are two different types of episodes, but they share the same symptoms. Mania is more pronounced than hypomania and causes more noticeable problems at work, school, and social activities, as well as relationship difficulties. Mania can also cause a break with reality (psychosis) and require hospitalization.

Both a manic episode and a hypomanic episode include three or more of these symptoms:

- Abnormally optimistic or nervous

- Increased activity, energy or excitement

- Exaggerated sense of well-being and self-confidence (euphoria)

- Reduced need for sleep

- Unusual talkativeness

- Distractibility

- Poor decision-making - for example, in speculation, in sexual encounters or in irrational investments

Major depressive episode

Major depressive episode includes symptoms that are severe enough to cause noticeable difficulty in daily activities such as work, school, social activities, or relationships. Episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

- Depressed mood, such as feeling sad, empty, hopeless, or tearful (in children and adolescents, depressed mood may manifest as irritability)

- Marked loss of interest or feeling of displeasure in all (or nearly all) activities

- Significant weight loss with no diet, weight gain, or decreased or increased appetite (in children, failure to gain weight as expected may be a sign of depression)

- Either insomnia or sleeping too much

- Either anxiety or slow behavior

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Decreased ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

- Thinking, planning or attempting suicide

Other features of bipolar disorder

Signs and symptoms of bipolar I and bipolar II disorder may include other signs such as anxiety disorder, melancholia, psychosis, or others. The timing of symptoms may include diagnostic markers such as mixed or fast cycling. In addition, bipolar symptoms may occur during pregnancy or with the change of seasons.

The timing of symptoms may include diagnostic markers such as mixed or fast cycling. In addition, bipolar symptoms may occur during pregnancy or with the change of seasons.

When to see a doctor

Despite extreme moods, people with bipolar disorder often do not realize how much their emotional instability disrupts their lives and the lives of their loved ones and do not receive the necessary treatment.

And if you are like people with bipolar disorder, you can enjoy feelings of euphoria and be more productive. However, this euphoria is always accompanied by an emotional disaster that can leave you depressed and possibly in financial, legal, or other bad relationships.

If you have symptoms of depression or mania, see your doctor or mental health professional. Bipolar disorder does not improve on its own. Getting mental health treatment with a history of bipolar disorder can help control your symptoms.

Seasonality and atypicality in affective disorders: actual problems

Authors: I. D. Spirin, A.V. Shornikov

D. Spirin, A.V. Shornikov

07/09/2016

In recent years, especially during recessions, the prevalence of mental disorders in general and depressive disorders in particular has increased. According to the forecasts of the World Health Organization, by 2020 mental illness will be among the main causes of disability in the population, and affective disorders will take second place after coronary heart disease. Despite the rather high proportion of bipolar affective disorder (BAD) both in the general population and in clinical samples, BAD is often diagnosed quite late. Unresolved problems in this area are atypical and seasonal patterns in affective disorders.

ID Spirin

One of the first references to the seasonality of bipolar disorder we find in S.S. Korsakov in the second edition of the "Course of Psychiatry" (1901): "In some patients, an attack appears fatally at certain intervals, as if according to a calendar, number for number. "

"

When applying the ICD-10 criteria, it is not possible to take into account some of the indicated features of BAD, including seasonality, in the diagnosis. Based on these criteria, seasonal patterns in bipolar disorder are coded under F 31.8 Other Bipolar Affective Disorders. This rubric also includes BAD type II, recurrent manic episodes, which makes this rubric extremely heterogeneous, making further research difficult [1].

According to DSM-V, the following features of bipolar disorder are distinguished:

• with anxiety distress;

• with mixed features;

• with fast cycles;

• with psychotic symptoms congruent to mood;

• with psychotic symptoms incongruent to mood;

• with catatonic inclusions;

• with peripartum onset;

• seasonal: refers only to the pattern of major depressive episodes [2].

By seasonality, we mean the regular seasonal pattern of at least one type of episode (i.e., mania, hypomania, or depression). Other types of episodes may not follow this pattern.

Other types of episodes may not follow this pattern.

DSM-V seasonality criteria are considered to be:

A. A regular temporal relationship between the onset of manic, hypomanic, or major depressive episodes and at certain times of the year (for example, autumn or winter) in bipolar type I and type II disorder.

Note: This does not include cases in which there is a clear effect of psychosocial seasonal stressors (e.g. regular unemployment every winter).

B. Complete remissions (or transition from major depression to mania or hypomania, or vice versa) that occur at specific times of the year (for example, depression disappears in the spring).

C. During the past 2 years, manic, hypomanic, or depressive episodes were temporally seasonal, as defined above, and episodes of this polarity did not occur out of season during that 2-year period.

D. Seasonal manias, hypomanias, or depressions outnumber any seasonal manias, hypomanias, or depressions that could occur during a person's lifetime [2].

An essential feature is the onset and course of major depressive episodes at characteristic times of the year. In most cases, episodes begin in the fall or winter and pass in the spring. Less commonly, recurrent summer depressive episodes may occur.

Major depressive episodes are often characterized by decreased energy, hypersomnia, binge eating, weight gain, and carbohydrate cravings, bringing seasonal affective disorder closer to atypical depression.

Within group bipolar disorder, seasonal patterns appear to be more likely in bipolar II than in bipolar I.

The prevalence of seasonality of the winter type of pattern may vary depending on latitude, age and gender. The prevalence of the disease increases at higher latitudes. Age is also a strong predictor of seasonality, with younger people at higher risk for winter depressive episodes. The prevalence of seasonal affective disorder in the United States ranges from 1.5 to 9% depending on the latitude, in Canada it is up to 5%, in the UK - up to 2%. There are no statistical data for Ukraine, which is primarily due to the lack of the possibility of diagnosing seasonality in affective disorders [3].

There are no statistical data for Ukraine, which is primarily due to the lack of the possibility of diagnosing seasonality in affective disorders [3].

The most common seasonal affective disorders are women, with a female:male ratio of 9:2.

Etiological theories primarily include various genetic theories, such as polymorphism in the ARNTL gene, polymorphism in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), which disrupts circadian rhythms and causes seasonal patterns of affective disorders. Genetic predisposition becomes a more significant factor in the presence of an unfavorable environment [4].

One of the most frequently discussed pathogenic theories of bipolar disorder is the theory of desynchronosis (D.F. Kripke). The essence of the theory is that the seasonally dependent course of depression can be associated with early evolutionary biological forms of expression of seasonally related rhythms of behavior, which are explained by photoperiodic mechanisms. And given the dependence of the occurrence of seasonal affective disorders on geographical latitude, the study of seasonal patterns of affective disorders in the conditions of the northern regions becomes relevant [5].

And given the dependence of the occurrence of seasonal affective disorders on geographical latitude, the study of seasonal patterns of affective disorders in the conditions of the northern regions becomes relevant [5].

Interesting results were obtained in a number of works by T.L. Kot et al. They found that the presence of peaks of exacerbations of endogenous depressions in the winter-summer period in residents of the northern regions can be explained by the presence of pronounced photodesynchronosis during light deprivation in winter and "light pollution" during the "white nights" period and, given the low functional activity of the epiphysis in the summer period, a decrease endogenous antidepressant effect on the central nervous system, modulated by melatonin, the secretion of which decreases in summer [6].

So, with affective disorders, there are violations of circadian rhythms not only of melatonin, but also of others: behavioral (sleep-wakefulness, vital rhythm of activity), physiological (for example, body temperature), endocrine (melatonin, cortisol, thyroid hormones, prolactin, somatotropin ).

On the one hand, the level of melatonin is a biological marker of depression, on the other hand, sleep-wake rhythm disturbances can provoke depressive disorders. Desynchronosis should include forced and permanent disturbances in the rhythm of sleep-wakefulness, for example, during long flights, during the night nature of work. It is believed that desynchronosis is a significant risk factor for affective disorders.

Causal links between serotonin, melatonin, circadian rhythms, vitamin D and seasonal affective disorders have not yet been confirmed from the standpoint of evidence-based medicine. However, associations between these key factors are present and continue to be explored.

In our clinical practice, we found it convenient to use the data of V.E. Medvedev, who, in case of seasonal affective disorders, distinguishes two types of depression with a different somatovegetative complex and a stereotype of the course. It is appropriate to consider a special personal predisposition represented by hypochondriacal or neuropathic diathesis with sensitivity to weather and climatic conditions as a factor in the development of seasonality of affective disorders and the dominance of the somatovegetative symptom complex in the structure of depression.

Both traditional pharmacotherapy and non-pharmacological methods of treatment are used as the main methods of treatment for BAD with a seasonal pattern. Here, cognitive-behavioral therapy and light therapy (bright white or narrow blue light) are favored, which, according to the results of several randomized clinical trials, show comparable effectiveness.

CBT, light therapy, vitamin D, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and melatonergic antidepressants are indicated as prevention.

The seasonal pattern of affective disorders can be comorbid with other disorders such as attention deficit disorder, alcohol dependence, eating disorders, making it difficult to diagnose. In addition, seasonality of affective disorders can be combined with hypothyroidism, especially in endemic regions, while hypothyroidism can mask the symptoms of seasonality. We must also include shift workers, such as nurses, as a risk group, since this disorder can be caused by limited exposure to sunlight.

Another topical problem is atypical depression. Depending on the inclusion and sampling criteria, the prevalence of atypical depressive disorders ranges from 15 to 36% [7-10]. This is partly explained by the data of A.V. Serdyuk and others, according to which any "deviations" from the classical clinical picture of depression are considered as a reason to refute the diagnosis of an affective disorder. Depressive states in such cases are often classified in other headings [11].

The rubric "atypical depression" includes various depressive states characterized by reactive mood changes, sensitivity to interpersonal contacts (painful reaction to criticism or rejection by other people), inverted autonomic-somatic symptoms, such as increased appetite and hypersomnia.

Thus, in accordance with the DSM-V criteria, the diagnosis of atypical depression requires that the current criteria for a major depressive episode be taken into account, and there must also be: 1) mood reactivity - the ability to experience at least 50% improvement in mood after exposure to a positive event, as well as more at least two other criteria; 2) increased drowsiness - sleep duration more than 10 hours a day; 3) "lead paralysis" - a feeling of heaviness in the limbs; 4) hyperphagia - increased appetite or weight gain; 5) refusal of interpersonal sensitivity - increased sensitivity to criticism or refusal as a result of functional disorders from interpersonal contacts [2].

In our clinical practice, we increasingly encounter patients with bipolar disorder, in whom depressive episodes are diagnosed in the autumn-winter period, and hypomanic and manic episodes in the spring and summer.

Based on the foregoing, the main issues of diagnosing and treating BAD, promising for in-depth study, should be considered:

- development of an algorithm for interaction with primary care in order to increase the level of knowledge of general practitioners on BAD problems;

- strengthening the evidence base for diagnosing bipolar disorder, including atypical and with a seasonal pattern, as well as monitoring in this area;

- development and implementation in the practice of primary care physicians of simple and reliable standardized tools for the detection of bipolar spectrum disorders;

- prevention of this disorder in risk groups, primarily among people employed in shift work;

- clarification of the modern clinical structure of atypical depression;

- development of diagnostic tools for the detection of atypical and seasonal depressions, selection of criteria for their differentiation from non-circular depressions and bipolar disorder.

These issues are of particular importance in connection with the preparation of a new international classification of diseases (ICD-11), as discussions are underway to include type II bipolar disorder in it, the manifestation of which is considered to be atypical and seasonal depression.

References are under revision.

- Number:

- Thematic issue "Neurology, Psychiatry, Psychotherapy" No. 2 (37), cherven 2016

21.10.2022 Psychiastraita, the bartness of the non-bonds of the unanimous vitrati at the likovanni with antideparests: the results of a systematic look at the Merei Metaaliza of the Ekonomic Modeling

Great Depressive Rosemy of the Glorita, the 13th cause of the 13th reason. sickness [1, 2]. Antidepressants are the main means of treating the great depressive disorder. As previous studies have shown, drugs of the same class may have similar efficacy, but they may also vary significantly in the profile of side effects [3, 6-10]. Such manifestations as anxiety, sleeplessness, sexual dysfunction, changes in body mass, anhedonia (lack of satisfaction), are blamed practically on another patient's skin for depression, which can be overcome by the influx of antidepressants, which often become a cause [4]. Also, current recent data on side effects can help clinicians choose antidepressants to treat their patients....

sickness [1, 2]. Antidepressants are the main means of treating the great depressive disorder. As previous studies have shown, drugs of the same class may have similar efficacy, but they may also vary significantly in the profile of side effects [3, 6-10]. Such manifestations as anxiety, sleeplessness, sexual dysfunction, changes in body mass, anhedonia (lack of satisfaction), are blamed practically on another patient's skin for depression, which can be overcome by the influx of antidepressants, which often become a cause [4]. Also, current recent data on side effects can help clinicians choose antidepressants to treat their patients....

10/17/2022 PsychiatryPost-traumatic stress disorder in the minds of the military camp: space and possibility of phytotherapy

Ukraine continues to defend its independence from war in Russia. Our viiSkovі struggle in the minds of trival, the sobbing of the sovereign Zhitta Sustyatyv, and our civilian is the country of the same novin, about the no -reasoning of the hen of the hen of the tread, we are wounding the worship of the waist. It negatively affects the psycho-emotional state of people, so now not only psychiatrists, but representatives of other medical specializations and non-medical doctors can get stuck with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) ....

Our viiSkovі struggle in the minds of trival, the sobbing of the sovereign Zhitta Sustyatyv, and our civilian is the country of the same novin, about the no -reasoning of the hen of the hen of the tread, we are wounding the worship of the waist. It negatively affects the psycho-emotional state of people, so now not only psychiatrists, but representatives of other medical specializations and non-medical doctors can get stuck with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) ....

10/17/2022 PsychiatryGamalate-B6 in the wake of the anxious states

The anxious state is an emotional discord, mindful of the anxiety of the restlessness before the future podias or in the situation of innocence. These physical changes are accompanied by organic symptoms (psychosomatic illnesses). On the other hand, organic illness can be troublesome, as if causing illness, pain, suffering of the patient, disrupted by the rhythm of that special social life, just work. Sedative drugs, especially benzodiazepines and sedatives, are most commonly seen in anxiety states. ...

On the other hand, organic illness can be troublesome, as if causing illness, pain, suffering of the patient, disrupted by the rhythm of that special social life, just work. Sedative drugs, especially benzodiazepines and sedatives, are most commonly seen in anxiety states. ...

02.10.2022 Psychiatry Troubled discord in the practice of a family doctor: how can you safely repair it?

Scientific and practical conference “Until the Day of the Medical Practitioner (19.06.2022). International Conference on Advances in Health and Medical Science 2022 practitioners in various specialties for the development of topical nutrition and medical assistance to patients of a therapeutic profile. As part of the call, the professor of the Department of Internal Medicine of the Kharkiv National University named after I.