Otherwise specified dissociative disorder

Other Specified & Unspecified Dissociative Disorders

Other Specified Dissociative Disorder

This disorder is characterized by a loss of awareness or orientation to their surroundings and/or identity. The functions of consciousness, memory, identity, or perception of one’s environment is disrupted.

In a dissociative trance, a person may be completely unresponsive to outside, surrounding stimuli (for instance, someone trying to talk to them may be ignored). This person may perceive that things around them are “surreal,” “blurred,” or moving around them while they remain paralyzed and unable to gain control over their environment.

The person may experience periods during which they question, reject, or detach from their awareness of who they are. These symptoms are rare and usually occur in those who have experienced prolonged stress of torture, abuse, or captivity.

These symptoms cannot be part of a culturally-accepted practice or religious ritual.

Others chronically or recurrently experience a combination of these states, termed syndrome of mixed dissociative symptoms.

Dissociative experiences that are of transient or brief nature most often occur as an acute reaction to an intensely stressful experience or traumatic event. Some common dissociative symptoms in these instances include:

- The feeling that time is slowing down

- Amnesia (recognized following the stressor as an inability to recall important parts of the event)

- A narrowing of consciousness or “tunnel vision”

- Feeling as if one were on chemical anesthetics or analgesics to some degree

Unspecified Dissociative Disorder

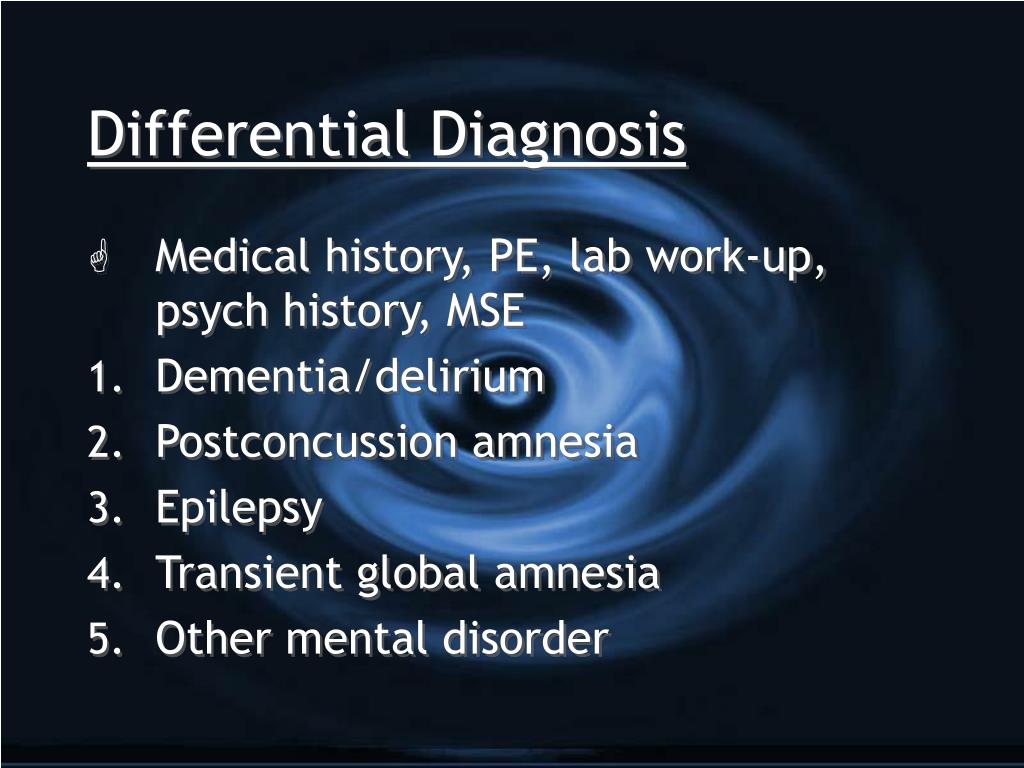

Sometimes, one may show signs of a noteworthy dissociative condition or an event that does not fit neatly into the typical presentation of a known dissociative disorder. At other times, the source of dissociative symptoms may be unclear. For example, in the ER after a car accident when the person has experienced a head trauma — here symptoms may be due to a medical injury.

Sometimes, even in non-emergency settings, a patient may require an ongoing assessment of their symptoms in order for a clinician to gather sufficient evidence to confirm the existence of a dissociative disorder.

In these situations, the unspecified dissociative disorder may be used (often as a “working diagnosis”). Specifically, the unspecified category applies to a dissociative episode or experience that significantly distresses a person and/or impacts ability to function in daily life, yet does not meet all the criteria for one of the established, known dissociative disorders. For example, if a person had met all but one symptom criteria for a particular dissociative disorder, this diagnosis would be appropriate.

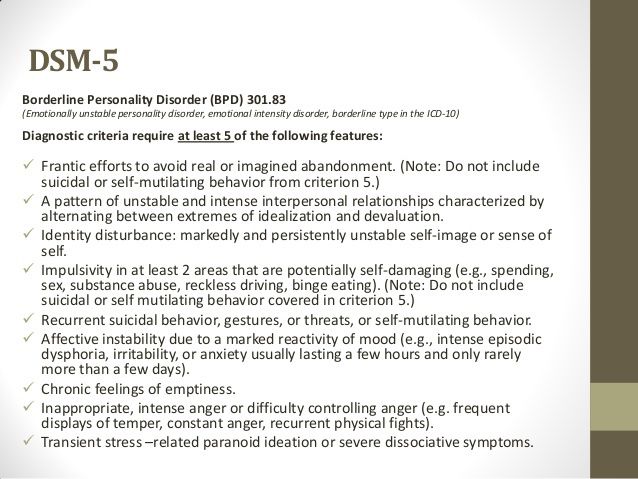

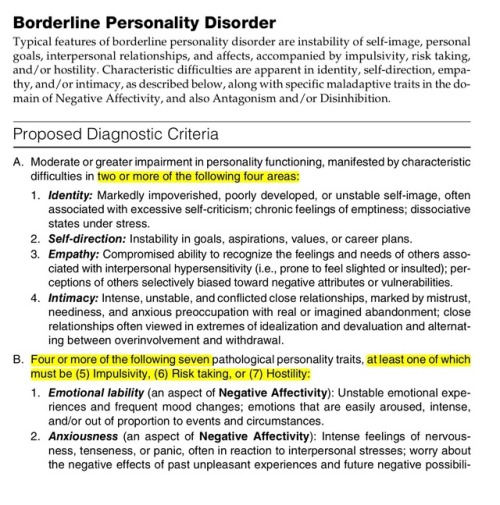

This criteria has been adapted for the 2013 DSM-5. Other specified dissociative disorder and unspecified dissociative disorder (diagnostic code 300.15) are new additions to the DSM-5.Dissociative Disorder: Not Otherwise Specified (NOS)

Dissociative disorder not otherwise specified historically refers to symptoms of a dissociative disorder that doesn’t quite meet full criteria. Currently, “other specified” or “unspecified” dissociative disorder is used.

Currently, “other specified” or “unspecified” dissociative disorder is used.

If you’re experiencing dissociative symptoms that don’t seem to match the major types of dissociative disorder, you may have what mental healthcare professionals previously called dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (DDNOS).

The term DDNOS was used until 2013, when the most recent version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) introduced new criteria for classifying dissociative disorders.

Thus, people who once would have received a diagnosis of DDNOS would now be diagnosed with one of several other conditions.

Dissociative disorder not otherwise specified is a former condition classification that mental healthcare professionals no longer use.

Before the classification change, older studies found that 8.3% of people experienced DDNOS. In contrast, studies have found that the most severe form of dissociative disorder, dissociative identity disorder (DID), is present in about 1% of the population.

Thus, DDNOS and the conditions that have replaced this former classification are fairly common.

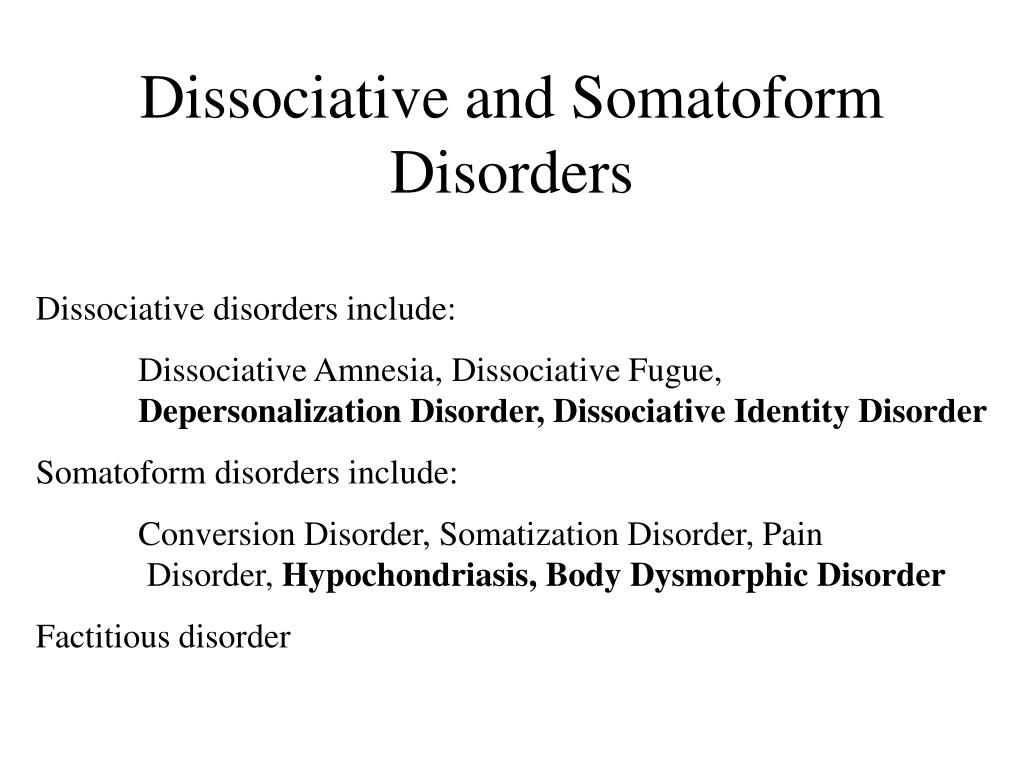

The DSM-5 now includes five conditions in the category of dissociative disorders:

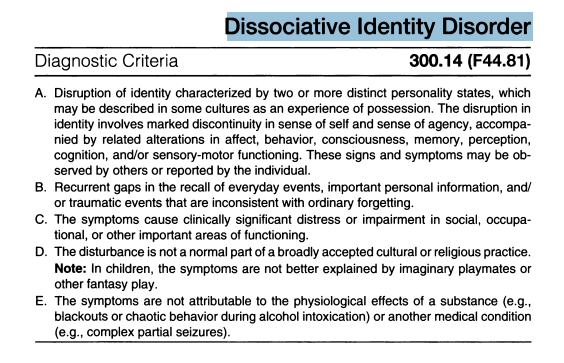

- dissociative identity disorder (DID)

- dissociative amnesia (DA), including dissociative fugue (DF)

- depersonalization/derealization disorder (DPDRD)

- other specified dissociative disorder (OSDD)

- unspecified dissociative disorder (UDD)

What used to be called dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (DDNOS) now falls mainly into the above categories of “other specified dissociative disorder” and “unspecified dissociative disorder,” although some people’s conditions may fall into other categories.

Other diagnostic classifications

This definition of DDNOS is specifically from the DSM-5.

Other diagnostic authorities, such as the International Classification of Diseases, 11th edition (ICD-11), have their own overlapping but distinct diagnostic criteria for dissociative disorders.

Dissociative identity disorder not otherwise specified is no longer a diagnosable disorder, according to the latest version of the DSM.

However, in all cases of dissociative disorders, the person would have dissociative symptoms that cause them significant problems or distress in key areas of their life, like with family, friends, or at work.

Dissociative symptoms the person might have depend on the specific disorder. They include:

- gaps in memory about certain events, time periods, or people

- you don’t feel a consistent sense of identity and might perceive that other personalities (or alters) sometimes take control of your actions

- you feel emotionally detached or numb

- you frequently feel like you are separated from your body and watching yourself from afar

- you experience other mental healthcare conditions and situations, such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts

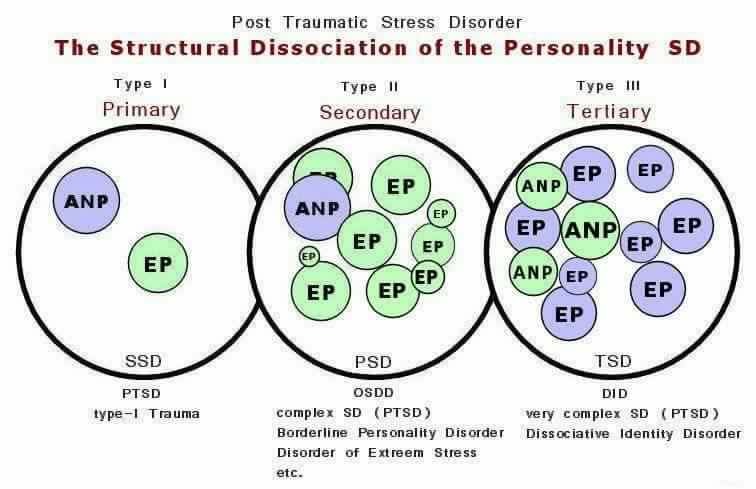

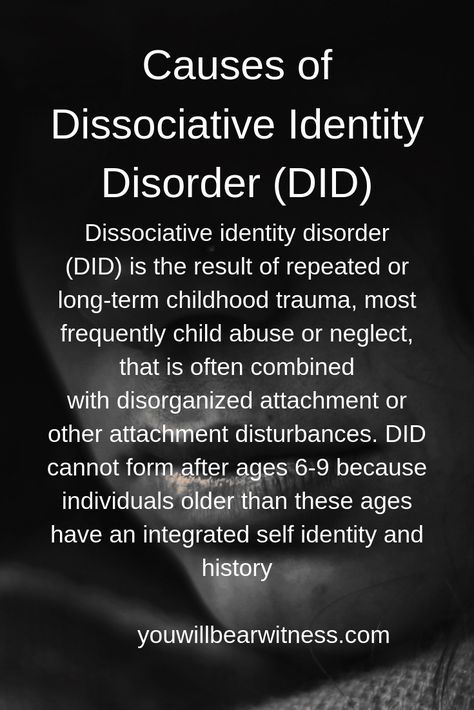

Researchers have found that dissociative disorders are strongly associated with psychological trauma, particularly prolonged traumatic experiences in childhood.

Every version of the DSM seeks to improve upon previous versions so that mental healthcare professionals can use the classification system to provide diagnoses that are as accurate and precise as possible.

To serve that purpose, in its newest edition published in 2013, the DSM has broken down the classification of DDNOS into the classifications we list above.

A mental healthcare professional might diagnose someone who would have formerly been diagnosed with DDNOS with one of the following conditions:

- dissociative identity disorder (DID), which has broader criteria in the DSM-5 compared with before

- depersonalization/derealization disorder, which now also has broader criteria

- other specified dissociative disorder

- unspecified dissociative disorder

The last two in this list are new classifications created to replace DDNOS.

In both of these conditions, the person shows dissociative symptoms that cause them significant problems or distress. However, their dissociative symptoms may be less defined or frequent than the symptoms of someone with DID, for example.

However, their dissociative symptoms may be less defined or frequent than the symptoms of someone with DID, for example.

Other specified dissociative disorder

Most people who would have been diagnosed with DDNOS with the previous version of the DSM would now be diagnosed with this condition.

Mental healthcare professionals use this classification in situations where they decide to specify the reason why the person doesn’t meet criteria to be diagnosed with a specific dissociative disorder.

Reasons a healthcare professional might specify include:

- The person has long-term changes in or questions about their identity after they experience prolonged, intense coercive persuasion, such as brainwashing, cult indoctrination, political imprisonment, or torture.

- The person frequently and repeatedly experiences dissociative symptoms, but they don’t have amnesia, or it’s hard to determine when or whether they felt breaks from their sense of self or felt like someone else was in control.

- The person experiences strong dissociative symptoms in reaction to stressful events.

- The person experienced a dissociative trance in which they became unresponsive but not as part of a normal cultural or religious practice.

Unspecified dissociative disorder

A person diagnosed with unspecified dissociative disorder would also have dissociative symptoms but would not satisfy all the standard indicators to be diagnosed with any of the other dissociative disorders.

It’s different than otherwise specified dissociative disorder (OSDD) in that the diagnosing healthcare professional decides they don’t want to specify why the person doesn’t meet the criteria.

Reasons for this could be:

- There’s not enough information available to make a specific diagnosis, such as in cases where a person has just come into the emergency room.

- The clinician decides for some other reason not to specify how the person did not meet the criteria.

If you think you might have a dissociative disorder, such as other specified dissociative disorder or unspecified dissociative disorder, consider reaching out to a licensed psychotherapist who has experience treating dissociative disorders.

You could ask a doctor to recommend a therapist or search for an expert yourself online. You can also try using this therapist search tool.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness offers this list of resources for getting help with dissociative disorders.

You can also learn more about dissociative disorders from these organizations:

- The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)

- The American Psychiatric Association (APA)

Whether you’re a mental healthcare professional or you’re experiencing dissociative symptoms yourself, you may be looking for more information on how DDNOS is diagnosed.

Though healthcare professionals no longer use DDNOS as a diagnosis, they have other ways to more accurately diagnose and treat people experiencing these dissociative conditions.

📖 List of diagnostic headings of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, 1995 (ICD-10), including borderline conditions.

20, Clinical features of the main forms of borderline mental disorders, Section II. Clinic of borderline mental disorders. Borderline mental disorders. Tutorial. Aleksandrovsky Yu. A. Page 14. Read online

20, Clinical features of the main forms of borderline mental disorders, Section II. Clinic of borderline mental disorders. Borderline mental disorders. Tutorial. Aleksandrovsky Yu. A. Page 14. Read online List of diagnostic rubrics International Statistical Classification of Diseases and health problems, tenth revision, 1995 (ICD-10), including boundary conditions.

2020 edition WHO. Russian translation S.-P., 1994, 1995; adapted option for use in the Russian Federation. M., 1998.

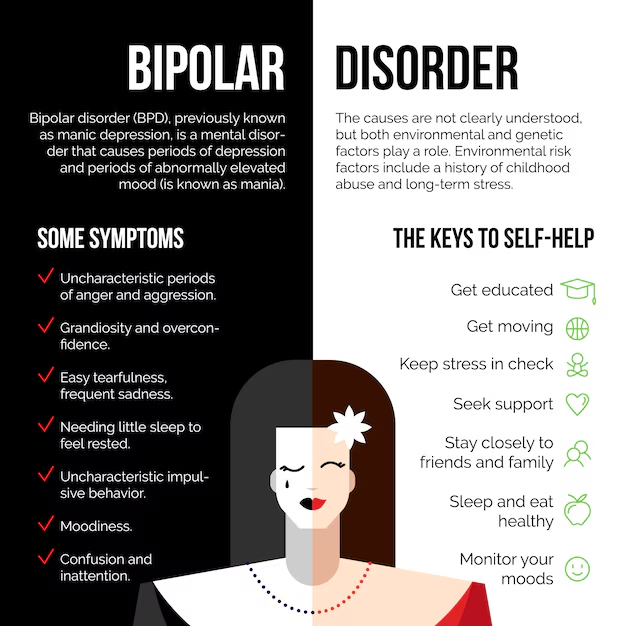

F3 Affective mood disorders

F30 Manic Episode

F30.0 Hypomania

Psychology bookap

F30.1 Mania without psychotic symptoms

F30.2 Mania with psychotic symptoms

F30.

8 Other manic episodes

F30.9 Manic episodes, unspecified

F31 Bipolar affective disorder

F31.0 Bipolar affective disorder, current hypomanic episode

Psychology bookap

F31.1 Bipolar affective disorder, current episode of mania without psychotic symptoms

F31.2 Bipolar affective disorder, current manic episode with psychotic symptoms

F31.3 Bipolar affective disorder, current episode of moderate or mild depression

.30 without somatic symptoms

.31 with somatic symptoms

F31.4 Bipolar affective disorder, current episode of severe depression without psychotic symptoms

Psychology bookap

F31.5 Bipolar affective disorder, current episode of severe depression with psychotic symptoms

F31.6 Bipolar affective disorder, current episode mixed

F31.7 Bipolar affective disorder, condition remissions

Psychology bookap

F31.

8 Other bipolar affective disorders

F31.9 Bipolar affective disorder, unspecified

F32 Depressive episode

F32.0 Mild depressive episode

.00 without somatic symptoms

.01 with somatic symptoms

F32.1 Moderate depressive episode

.10 without somatic symptoms

.11 with somatic symptoms

F32.2 Severe depressive episode without psychotic symptoms

Psychology bookap

F32.3 Major depressive episode with psychotic symptomatic

F32.8 Other depressive episodes

F32.9 Depressive episodes, unspecified

F33 Recurrent depressive disorder

F33.0 Recurrent depressive disorder, current mild episode

.00 without somatic symptoms

.01 with somatic symptoms

F33.

1 Recurrent depressive disorder, current moderate episode

.10 without somatic symptoms

.11 with somatic symptoms

F33.2 Recurrent depressive disorder, current severe episode without psychotic symptoms

Psychology bookap

F33.3 Recurrent depressive episode, current severe episode with psychotic symptoms

F33.4 Recurrent depressive disorder, condition remission

F33.8 Other recurrent depressive disorders

F33.9 Recurrent depressive disorder, unspecified

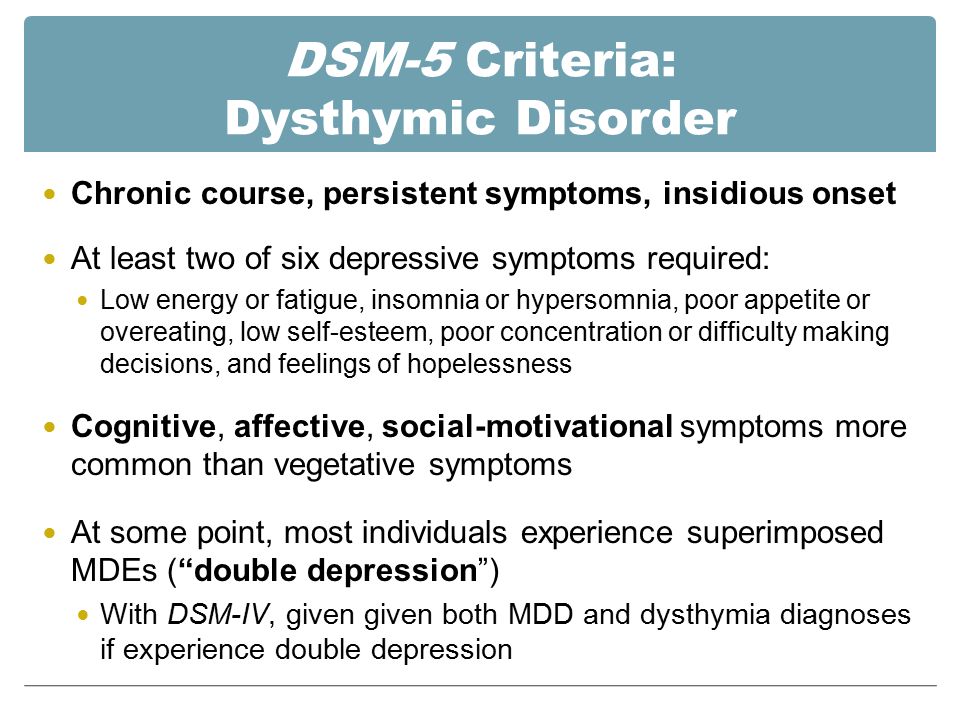

F34 Chronic (affective) mood disorders

F34.0 Cyclothymia

Psychology bookap

F34.1 Dysthymia

F34.8 Other chronic affective disorders F34.9 Chronic (affective) mood disorder, unspecified

F38 Other (affective) mood disorders

F38.0 Other single (affective) disorders moods

.

00 mixed affective episode

F38.1 Other recurrent (affective) disorders moods

.10 recurrent short-term depressive disorder

F38.8 Other specified (affective) disorders moods

F39 Unspecified (affective) mood disorders

F4 Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders

F40 Anxiety-phobic disorders

F40.0 Agoraphobia

.00 without panic disorder

.01 with panic disorder

F40.1 Social phobias

Psychology bookap

F40.2 Specific (isolated) phobias

F40.8 Other phobic anxiety disorders

F40.9 Phobic anxiety disorder, unspecified

F41 Other anxiety disorders

F41.0 Panic disorder (episodic paroxysmal anxiety)

Psychology bookap

F41.

1 Generalized anxiety disorder

F41.2 Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder

F41.3 Other mixed anxiety disorders

Psychology bookap

F41.8 Other specified anxiety disorders

F41.9 Anxiety disorder, unspecified

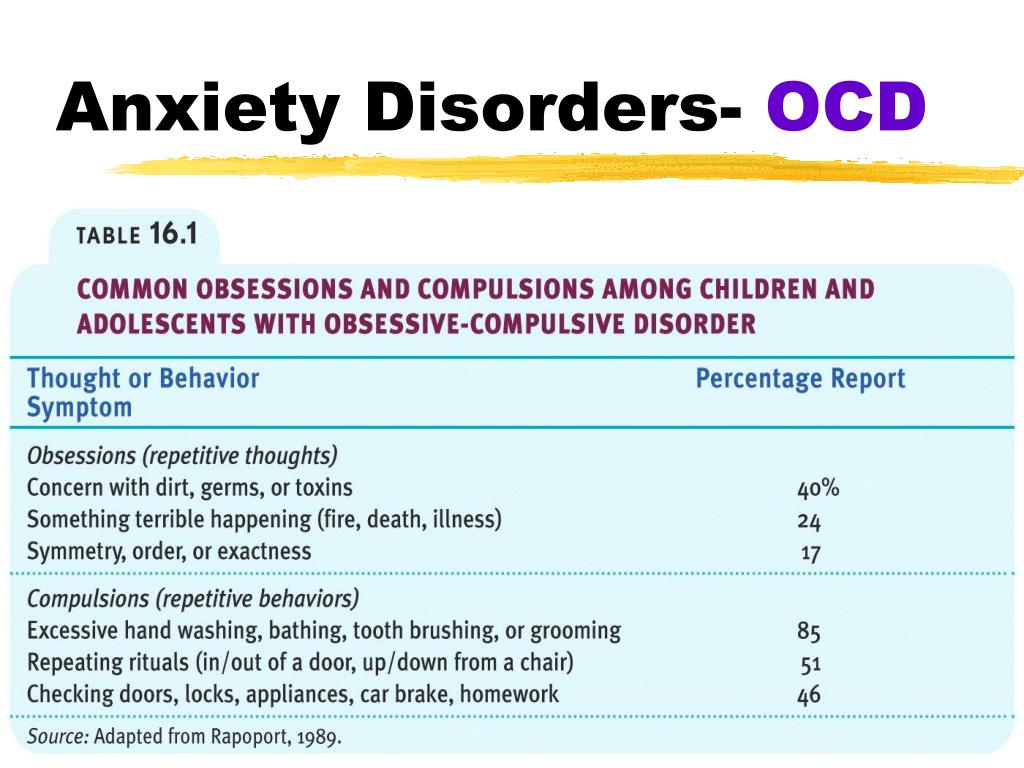

F42 Obsessive-compulsive disorder

F42.0 Predominantly intrusive thoughts or ruminations (mental gum)

Psychology bookap

F42.1 Predominantly compulsive actions (obsessional rituals)

F42.2 Mixed obsessive thoughts and actions

F42.8 Other obsessive-compulsive disorders

F42.9 Obsessive-compulsive disorder, unspecified

F43 Severe stress reactions and adjustment disorders 21

21 Socially stressful disorders (CVD) are described in detail in the relevant section of this manual. In ICD-10, SSRs are not distinguished, however, more and more evidence is accumulating to consider their inclusion in the classification schemes for mental illness.

F43.0 Acute stress reaction

Psychology bookap

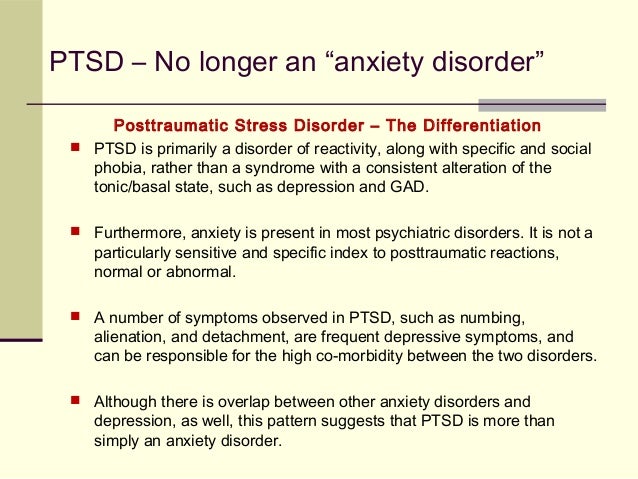

F43.1 Post-traumatic stress disorder

F43.2 Adjustment disorders

.20 short-term depressive reaction

Psychology bookap

.21 prolonged depressive response

.22 mixed anxiety and depressive reaction

.23 with predominant disturbance of other emotions

Psychology bookap

.24 with predominance of behavioral disorder

.25 mixed disorder of emotions and conduct

.28 other specific predominant symptoms

F43.8 Other reactions to severe stress 22

22 B this group includes nosogenic reactions that occur due to a serious somatic illness (the last is a traumatic event in these cases).

F43.9 Severe stress response, unspecified

F44 Dissociative (conversion) disorders 23

23 B ICD-10 the term "hysteria" is not used because of its many and varied meanings. The term "dissociative" is used instead. It combines the disorders described earlier in within the framework of hysteria and includes both properly dissociated, and conversion disorders.

F44.0 Dissociative amnesia

Psychology bookap

F44.1 Dissociative fugue

F44.2 Dissociative stupor

F44.3 Trances and states of mastery

Psychology bookap

F44.4 Dissociative motor disorders

F44.5 Dissociative convulsions

F44.6 Dissociative anesthesia and sensory loss perception

Psychology bookap

F44.7 Mixed dissociative (conversion) disorders

F44.8 Other dissociative (conversion) disorders

.80 Ganser syndrome

Psychology bookap

.81 multiple personality disorder

.82 transient dissociative (conversion) disorders that occur in childhood and adolescence aged

.88 other specified dissociative (conversion) disorders

F44.9 Dissociative (conversion) disorder, unspecified

F45 Somatoform disorders 24

24 Common in domestic medicine, the term "psychosomatic disorder" in ICD-10 is not used due to ambiguity of its definition in different languages and in the presence of unequal psychiatric traditions. In addition, psychological factors are important and broader in the origin and the course of various diseases, and not only included among the "psychosomatic". In ICD-10 for designation of "association" of physical or somatic manifestations with mental disorders the concept of "somatoform disorders" is used.

F45.

0 Somatization disorder

Psychology bookap

F45.1 Undifferentiated somatoform disorder

F45.2 Hypochondriacal disorder

F45.3 Somatoform autonomic dysfunction

.30 heart and cardiovascular system

Psychology bookap

.31 upper gastrointestinal tract

.32 lower gastrointestinal tract

.33 respiratory system

Psychology bookap

.34 urogenital system

.38 other body or system

F45.4 Chronic somatoform pain disorder

Psychology bookap

F45.8 Other somatoform disorders

F45.9 Somatoform disorder, unspecified

F48 Other neurotic disorders

F48.0 Neurasthenia

Psychology bookap

F48.1 Depersonalization-derealization syndrome

F48.8 Other specific neurotic disorders

F48.9 Neurotic disorder, unspecified

F5 Behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disorders and physical factors

F50 Eating disorders

F50.

0 Anorexia nervosa

Psychology bookap

F50.1 Atypical anorexia nervosa

F50.2 Bulimia nervosa

F50.3 Atypical bulimia nervosa

Psychology bookap

F50.4 Overeating associated with other psychological violations

F50.5 Vomiting associated with other psychological violations

F50.8 Other eating disorders

F50.9 Eating disorder, unspecified

F51 Inorganic sleep disorders

F51.0 Insomnia of inorganic nature

Psychology bookap

F51.1 Hypersomnia of inorganic nature

F51.2 Nonorganic sleep-wake disorder nature

F51.3 Sleepwalking (somnambulism)

Psychology bookap

F51.4 Night terrors (night terrors)

F51.5 Nightmares

F51.8 Other nonorganic sleep disorders

F51.9 Inorganic sleep disorder, unspecified

F52 Non-organic sexual dysfunction disorder or disease

F52.

0 Absence or loss of sexual desire

F52.1 Sexual aversion and lack of sexual satisfaction

.10 sexual disgust

. 11 lack of sexual satisfaction

F52.2 No genital response

Psychology bookap

F52.3 Orgasmic dysfunction

F52.4 Premature ejaculation

F52.5 Vaginismus of inorganic origin

Psychology bookap

F52.6 Nonorganic dyspareunia

F52.7 Increased sexual desire

F52.8 Other sexual dysfunction, not due to organic disorder or disease

F52.9 Unspecified sexual dysfunction, not due to organic disorder or disease

F53 Mental and behavioral disorders, associated with the postpartum period, not classified in other sections

F53.0 Mild mental and behavioral disorders, associated with the postpartum period, not classified in other sections

Psychology bookap

F53.

1 Severe mental and behavioral disorders, associated with the postpartum period, not classified in other sections

F53.8 Other mental and behavioral disorders, associated with the postpartum period, not classified in other sections

F53.9 Postpartum mental disorder, unspecified

F54 Psychological and behavioral factors associated with disorders or diseases classified elsewhere in other sections

F55 Abuse of non-causing substances dependencies

F55.0 Antidepressants

Psychology bookap

F55.1 Laxatives

F55.2 Analgesics

F55.3 Deacidifiers

Psychology bookap

F55.4 Vitamins

F55.5 Steroids or hormones

F55.6 Specific herbs and folk remedies

Psychology bookap

F55.8 Other non-addictive substances

F55.9 Unspecified

F59 Unspecified behavioral syndromes associated with with physiological disorders and physical factors

F6 Disorders of mature personality and behavior in adults 25

25 Disorders mature personality and behavior in adults, including in this category, are stable and are expression of the characteristics inherent in the individual lifestyle and way of relating to oneself and others ("models behavior"). In most cases, these disorders ontogenetically formed, appear in childhood or adolescence and persist into adulthood. They are not secondary to other mental disorders or diseases of the brain. extreme conditions and other psychotraumatic factors contribute to decompensation (reaction) of existing disorders of mature personality. In our country, most of those attributed to this category of disorders is traditionally considered in within psychopathy and pathological personality development.

extreme conditions and other psychotraumatic factors contribute to decompensation (reaction) of existing disorders of mature personality. In our country, most of those attributed to this category of disorders is traditionally considered in within psychopathy and pathological personality development.

F60 Specific personality disorders

F60.0 Paranoid personality disorder

Psychology bookap

F60.1 Schizoid personality disorder

F60.2 Antisocial personality disorder

F60.3 Emotionally unstable personality disorder

.30 impulsive type

.31 border type

F60.4 Histrionic personality disorder

Psychology bookap

F60.5 Anancaste (obsessive-compulsive) disorder personalities

F60.6 Anxious (avoidant) personality disorder

F60.7 Dependent personality disorder

Psychology bookap

F60.8 Other specific personality disorders

F60.

9 Personality disorder, unspecified

F61 Mixed and other personality disorders

F61.0 Mixed personality disorders

F61.1 Disturbing personality changes

F62 Chronic personality changes, unrelated with brain damage or disease

F62.0 Chronic personality change after experience disasters

Psychology bookap

F62.1 Chronic personality change after mental diseases

F62.8 Other chronic personality changes

F62.9 Chronic personality change, unspecified

F63 Disorders of habits and impulses

F63.0 Pathological gambling

Psychology bookap

F63.1 Pathological arson (pyromania)

F63.2 Pathological theft (kleptomania)

F63.3 Trichotilomania

Psychology bookap

F63.8 Other disorders of habits and drives

F63.9 Disorder of habits and drives, unspecified

F64 Gender identity disorders

F64.

0 Transsexualism

Psychology bookap

F64.1 Dual role transvestism

F64.2 Gender identity disorder in children

F64.8 Other gender identity disorders

F64.9 Gender identity disorder, unspecified

F65 Disorders of sexual preference

F65.0 Fetishism

Psychology bookap

F65.1 Fetish transvestism

F65.2 Exhibitionism

F65.3 Voyeurism

Psychology bookap

F65.4 Pedophilia

F65.5 Sadomasochism

F65.6 Multiple disorders of sexual preference

Psychology bookap

F65.8 Other disorders of sexual preference

F65.9 Disorder of sexual preference, unspecified

F66 Psychological and behavioral disorders, related to sexual development and orientation

F66.0 Disorder of puberty

Psychology bookap

F66.1 Ego-dystonic sexual orientation

F66.

2 Sexual relations disorder

F66.8 Other psychosocial developmental disorders

F66.9 Psychosocial development disorder, unspecified

F68 Other disorders of adult personality and behavior in adults

F68.0 Exaggeration of physical symptoms by psychological reasons

Psychology bookap

F68.1 Intentional induction or feigning of symptoms or disability, physical or psychological (faking disorder)

F68.8 Other specific disorders of the mature personality and behavior in adults

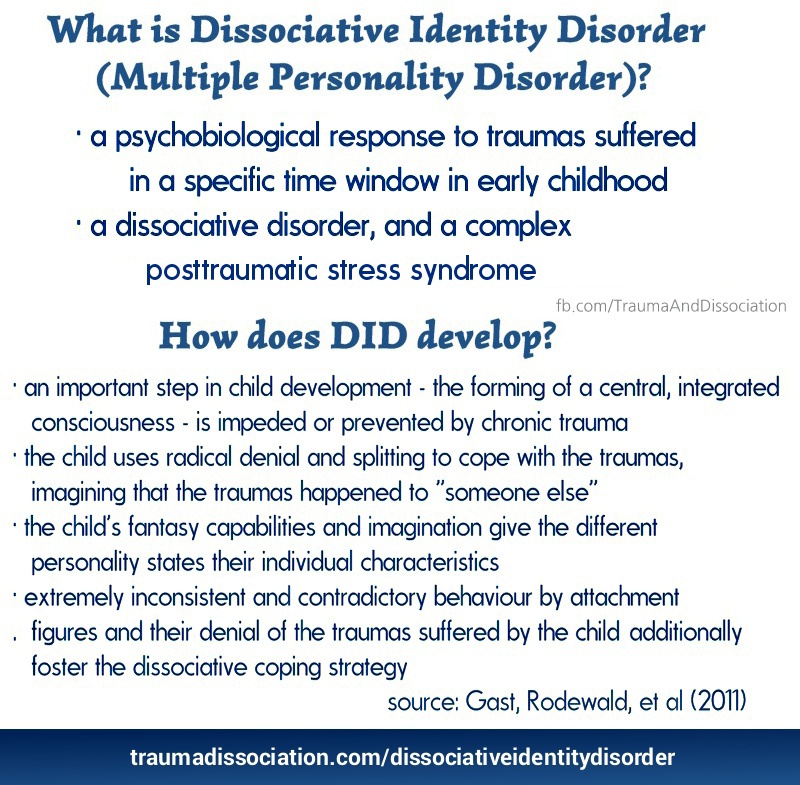

What is dissociative identity disorder?

Dissociative identity disorder is a mental disorder characterized by either having two or more personalities, or a state of disconnection from the outside world, one's identity, and an inability to remember certain daily life events and important personal information. This disorder is often mistaken for depression, anxiety, or psychosis. Long before our days, this condition was called possession, and it was treated with exorcism. In the 19th century, this disorder was called hysteria, and in the 20th century it was called multiple personality disorder or multiple personality disorder.

Long before our days, this condition was called possession, and it was treated with exorcism. In the 19th century, this disorder was called hysteria, and in the 20th century it was called multiple personality disorder or multiple personality disorder.

Types of dissociative identity disorder

There are several types of dissociative disorders, which are characterized by different symptoms and manifestations. One of them is dissociative fugue, a disorder in which a person can find himself in a completely unfamiliar place and not remember how he got there. In this case, a person may forget some important information about himself and not even remember his name. At the same time, memory for some information, such as literature, science, and other things, can be preserved. In a state of fugue, a person assumes a different personality and identity with a different character, mannerisms and behavior. While in this identity, a person can lead an outwardly normal life. A dissociative fugue can last for hours or years. After that, a person may find himself in a completely unfamiliar place and at the same time not remember anything that happened to him in a state of fugue.

A dissociative fugue can last for hours or years. After that, a person may find himself in a completely unfamiliar place and at the same time not remember anything that happened to him in a state of fugue.

A person who has a dissociative disorder is actually suffering a lot from their condition.

Another type of dissociative disorder is the presence of several personalities in which a person finds himself in turn or simultaneously. At such moments, he disconnects from himself and stops feeling his own body, and also cannot see himself from the outside. Personalities within a person can have different ages, genders, nationalities, mental abilities, temperaments, and behave in completely different ways. Often these personalities can even have different physiological manifestations. For example, while in one personality, a person can see poorly and wear glasses, and in another, have excellent vision and walk without glasses or lenses (or think that he sees perfectly and does without glasses). Just as in the case of dissociative fugue, when switching, one person cannot remember what happened to the person during immersion in another.

Just as in the case of dissociative fugue, when switching, one person cannot remember what happened to the person during immersion in another.

Manifestations of dissociative identity disorder

This disease affects both children (adolescents) and adults and presents with similar symptoms. However, dissociative disorder with multiple personalities in adolescents is quite rare. In old age, dissociation practically does not develop. When a specialist suspects a person of dissociative identity disorder, he usually asks if it happened that the person suddenly found himself in some place and did not understand how he got there. Also, the patient may suddenly speak in a completely different voice, he may have a different handwriting. For example, a person who has one of his personalities as a child may suddenly begin to write in a child's handwriting. Such phenomenal manifestations can be evoked in a patient suffering from dissociative personality disorder, and in a state of hypnosis. That is why the French psychiatrist Jean-Martin Charcot at one time mistakenly believed that hypnosis is a pathological condition that causes hysteria and the manifestation of multiple personalities. However, later it turned out that hypnosis is only superficially similar to dissociative personality disorder, but does not cause it, and the disease itself develops without any connection with hypnosis.

That is why the French psychiatrist Jean-Martin Charcot at one time mistakenly believed that hypnosis is a pathological condition that causes hysteria and the manifestation of multiple personalities. However, later it turned out that hypnosis is only superficially similar to dissociative personality disorder, but does not cause it, and the disease itself develops without any connection with hypnosis.

See also

Myths about hypnosis

A person who has a dissociative disorder is actually very distressed by his condition. He sees the negative or dismissive attitude of those around him: they look at him strangely, they reject him, no one finds a common language with him, because of him the family can collapse, and so on. At the moment of a dissociative state, a person does not have the opportunity to critically look at himself and his own behavior. That is, in a situation where one of the alternative personalities appears, he is in an inadequate state.

The main theory about the origin of this disease is based on the fact that in childhood such people experienced a traumatic situation, usually bullying or violence.

Dissociation is one of three conditions in which the patient is exempt from criminal liability, along with psychosis and mental retardation. There were cases when people in a dissociative state committed murder and rape. In such situations, even taking into account the severity of the crimes, patients are not sent to prison, but are sent to a psychiatric hospital or, in extreme cases, to a special ward of the psychiatric department of the prison.

Causes of dissociative identity disorder

Scientists have not yet found the genetic causes of dissociative personality disorder. The main theory about the origin of this disease is based on the fact that in childhood such people experienced a traumatic situation, usually bullying or violence. However, even this theory does not explain all 100% of cases of dissociative states. There are patients who, without an overt or identified traumatic situation in childhood, suffer from dissociative personality disorder. With regard to the physiological manifestations of this disorder, there is an assumption that in such patients certain areas of the brain stop working and others turn on. However, none of the theories suggesting physiological causes of dissociation currently explains all cases of the disease.

There are patients who, without an overt or identified traumatic situation in childhood, suffer from dissociative personality disorder. With regard to the physiological manifestations of this disorder, there is an assumption that in such patients certain areas of the brain stop working and others turn on. However, none of the theories suggesting physiological causes of dissociation currently explains all cases of the disease.

Diagnosis of dissociative personality disorder

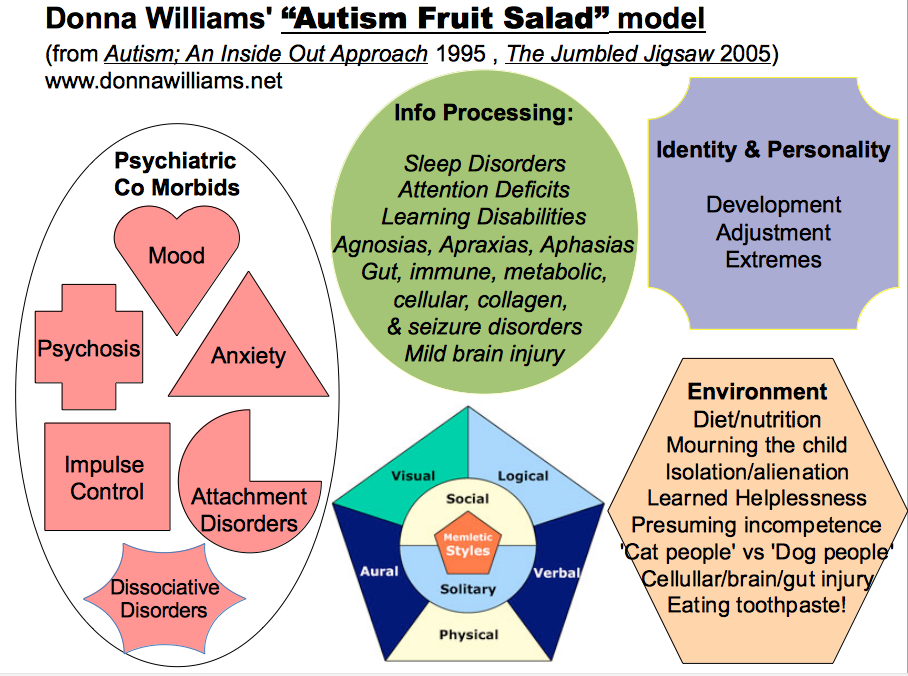

Diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder is made through clinical interviews with several specialists. Sometimes the diagnosis requires not one, but several meetings with psychologists and psychiatrists, so that they have the opportunity to identify different aspects of the disorder, look at the patient's condition from several points of view and assemble a consultation. However, the specialist who identifies this disorder must have a great deal of experience and qualifications, since this disease can often be confused with others. In its manifestations, it can be similar to depression, anxiety or psychosis. It is also common for patients with dissociative identity disorder to be diagnosed with schizophrenia. Dissociation is a rare disorder and not every mental health professional can diagnose this disorder.

In its manifestations, it can be similar to depression, anxiety or psychosis. It is also common for patients with dissociative identity disorder to be diagnosed with schizophrenia. Dissociation is a rare disorder and not every mental health professional can diagnose this disorder.

Medications do not cure dissociative identity disorder, but only relieve some of the symptoms.

See also

Mental norm and pathology

A separate task for a specialist in the process of diagnosing dissociation in a child is to distinguish diseases from the presence of imaginary friends in a child, which very often appear in perfectly healthy children at a certain age. To do this, a specialist must be highly qualified in the field of developmental psychology and clearly be able to recognize a dissociative disorder not only in adults, but also in children.

Treatment for dissociative identity disorder

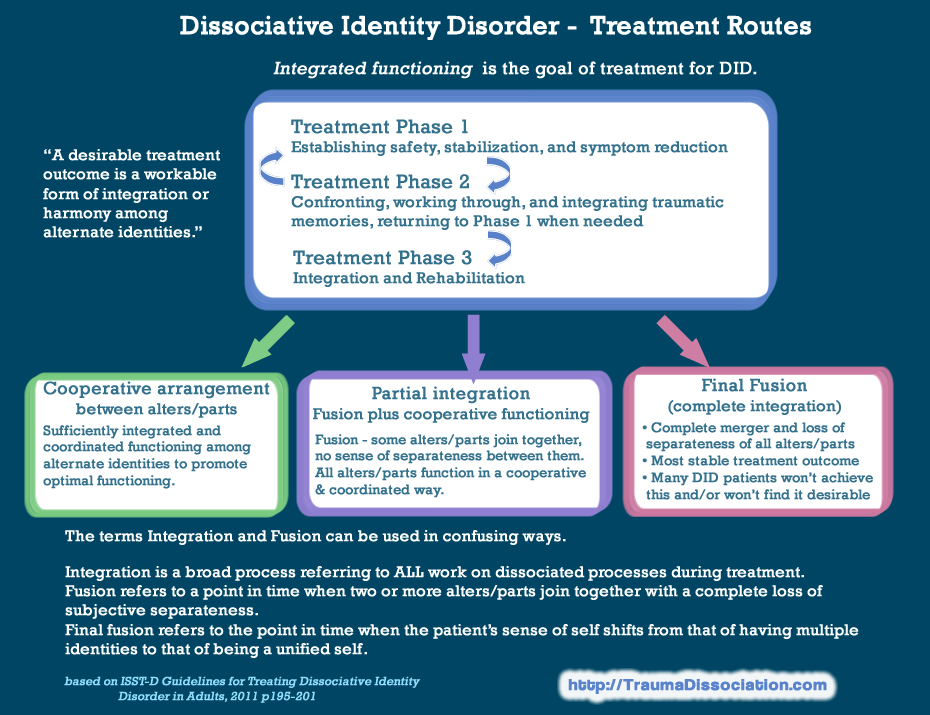

The main treatment for dissociative identity disorder is hypnosis.