Origin of yawning

Why do we yawn? | New Scientist

Many animals yawn but we are not entirely sure why. Perhaps it makes us more alert, reduces anxiety, or cools an overheating brain. Contagious yawning is even more mysterious but seems to be confined to highly social animals, which might provide a clue to its purpose.

What is yawning?

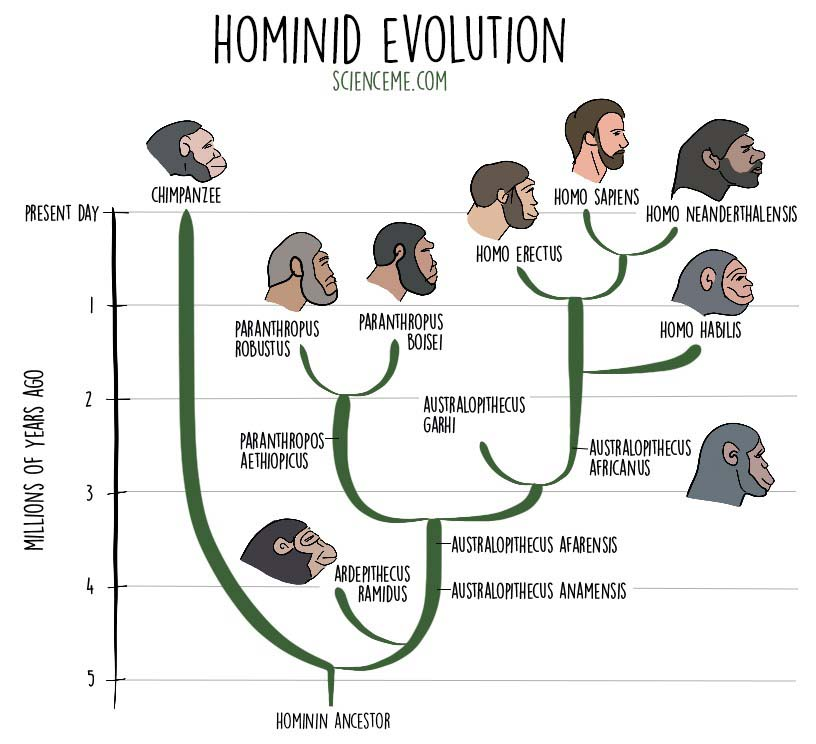

Yawning is an evolutionarily ancient reflex that we share with lots of animals – not just mammals but also birds, reptiles and fish. Humans begin yawning in the womb at around 11 weeks gestation. However, we don’t feel the urge to yawn when other people do until around four or five years old.

This indicates that there are two types of yawning – spontaneous and contagious – each requiring a separate explanation. Although we have some promising ideas, yawning is still something of a puzzle.

We tend to think of yawning as a sign of being tired or bored. That probably explains the popular perception that it is a way to get more oxygen into the blood to increase alertness. However, when psychologist Robert Provine at the University of Maryland, tested this idea he found it didn’t stand up – people were just as likely to yawn when breathing air high in oxygen.

Advertisement

A closer look at when people yawn suggests another explanation. It turns out that most spontaneous yawning actually happens when we are limbering up for activity such as a workout, performance or exam, or simply when we wake up. That has led to the idea that yawning helps us gear up by increasing blood flow to the brain. How exactly that might work is not clear, but it does fit with the observation that some fish yawn in anticipation of a fight.

Another possibility is that yawning cools the brain. This idea emerged from the observation that people yawned far less when their heads were cooled by cold packs. Temperature regulation is crucial for physiological performance. It is controlled by a brain region called the hypothalamus, and involves production of adrenaline and cortisol, hormones that increase alertness and help us deal with stress. That might also explain why people often yawn when feeling anxious – as do monkeys.

That might also explain why people often yawn when feeling anxious – as do monkeys.

Why is yawning contagious?

Explaining contagious yawning is even trickier. Apart from humans, the only other species known to catch yawns from one another are chimps, dogs (which can be infected by human yawns), the wonderfully named high-yawning Sprague-Dawley rat, budgerigars and lions, who appear to use yawning to send signals to the rest of the pride.

These animals are all very sociable, which suggests contagious yawning might have something to do with empathy, or at least a tendency to mimic and synchronise actions with others, a foundation of empathy. But whether contagious yawning helps us build social relationships is another matter. It could simply be a by-product of the way we and other highly-social animals instinctively respond to others.

The Surprising Science of Yawning

In 1923, Sir Francis Walshe, a British neurologist, noticed something interesting while testing the reflexes of patients who were paralyzed on one side of their bodies. When they yawned, they would spontaneously regain their motor functions. In case after case, the same thing happened; it was as if, for the six or so seconds the yawn lasted, the patients were no longer paralyzed. What’s more, Walshe reported that some of his patients had noticed “that when the fingers are extended and abducted during a yawn, they are able to flex and extend them rapidly, a thing they were unable to do at any other time. Indeed, one man added that he always waited for a yawn so that he might exercise his fingers in this way.”

Walshe concluded that yawning was activated by a primal center of the brain that fell outside conscious control. One’s ability to yawn could thus remain completely intact, even when “cortical control is more or less completely abolished over the musculature of one half of the body. ” Yawning, then, was one of our most primitive, fundamental behaviors—a conclusion that echoed Charles Darwin’s observation, in 1838, that “seeing a dog & horse & man yawn, makes me feel how much all animals are built on one structure.”

” Yawning, then, was one of our most primitive, fundamental behaviors—a conclusion that echoed Charles Darwin’s observation, in 1838, that “seeing a dog & horse & man yawn, makes me feel how much all animals are built on one structure.”

Yawning is one of the first things we learn to do. “Learn” may not even be quite the right word. Johanna de Vries, a professor of obstetrics at Vrije University Amsterdam, has discovered that the human fetus yawns during its first trimester in the womb. And, unless we succumb to neurodegenerative disease, yawning is something we keep doing throughout our lives. “You don’t decide to yawn,” Robert Provine, a neuroscientist and the author of “Curious Behavior: Yawning, Laughing, Hiccupping, and Beyond,” told me. “You just do it. You’re playing out a biological program.” We yawn unconsciously and we yawn spontaneously. We can’t yawn on command—and we sometimes can’t stop ourselves from letting out a big yawn, even at the most inopportune times. (Case in point: Sasha Obama’s infamous yawn during her father’s 2013 Inaugural Address.) But what, precisely, are we accomplishing with all this yawning? If it’s so evolutionarily old, it must be doing

something important to have survived.

(Case in point: Sasha Obama’s infamous yawn during her father’s 2013 Inaugural Address.) But what, precisely, are we accomplishing with all this yawning? If it’s so evolutionarily old, it must be doing

something important to have survived.

In 400 B.C., Hippocrates speculated that yawning was somehow related to fever: we yawned to expel the bad air that had accumulated inside our bodies, making us ill, much like “the large quantities of steam that escape from cauldrons when water boils.” That intuition has proved remarkably resilient. As recently as 2011, the psychologist Gordon Gallup argued that the yawn is a cooling mechanism for the brain and the body. But the evidence for those theories has been decidedly mixed, and, for now, the physiological function of the yawn remains elusive. As Provine puts it, “Yawning may have the dubious distinction of being the least understood, common human behavior.”

A more reliable clue to why we yawn may come from when, precisely, we do so. We usually think of yawning as a signal of sleepiness or boredom—one of the reasons Sasha Obama’s yawn seemed so inappropriate. Indeed, fatigue and boredom do reliably elicit yawns. While yawning isn’t actually related to the amount of sleep we get—how physiologically tired we are—or the time of day we choose to wake up and go to bed, it does seem to grow more intense when we’re feeling subjectively sleepy. In a series of studies conducted in the eighties and nineties, Provine demonstrated that people report yawning more frequently when they are feeling tired. They are especially prone to yawning in the hour immediately after waking and the hour preceding their usual bedtimes. Yawning also increases with boredom. In one experiment, Provine’s subjects yawned far more frequently when looking at static than when watching music videos. We also yawn when we’re getting hungry—a tendency we appear to share with other primates.

We usually think of yawning as a signal of sleepiness or boredom—one of the reasons Sasha Obama’s yawn seemed so inappropriate. Indeed, fatigue and boredom do reliably elicit yawns. While yawning isn’t actually related to the amount of sleep we get—how physiologically tired we are—or the time of day we choose to wake up and go to bed, it does seem to grow more intense when we’re feeling subjectively sleepy. In a series of studies conducted in the eighties and nineties, Provine demonstrated that people report yawning more frequently when they are feeling tired. They are especially prone to yawning in the hour immediately after waking and the hour preceding their usual bedtimes. Yawning also increases with boredom. In one experiment, Provine’s subjects yawned far more frequently when looking at static than when watching music videos. We also yawn when we’re getting hungry—a tendency we appear to share with other primates.

Boredom, hunger, fatigue: these are all states in which we may find our attention drifting and our focus becoming more and more difficult to maintain. A yawn, then, may serve as a signal for our bodies to perk up, a way of making sure we stay alert. When the psychologist Ronald Baenninger, a professor emeritus at Temple University, tested this theory in a series of laboratory studies coupled with naturalistic observation (he had subjects wear wristbands that monitored physiology and yawning frequency for two weeks straight), he found that yawning is more frequent when stimulation is lacking. In fact, a yawn is usually followed by increased movement and physiological activity, which suggests that some sort of “waking up” has taken place.

A yawn, then, may serve as a signal for our bodies to perk up, a way of making sure we stay alert. When the psychologist Ronald Baenninger, a professor emeritus at Temple University, tested this theory in a series of laboratory studies coupled with naturalistic observation (he had subjects wear wristbands that monitored physiology and yawning frequency for two weeks straight), he found that yawning is more frequent when stimulation is lacking. In fact, a yawn is usually followed by increased movement and physiological activity, which suggests that some sort of “waking up” has taken place.

“You yawn when you’re obviously not bored,” Provine points out. “Olympic athletes sometimes yawn before their events; concert violinists may yawn before playing a concerto.” Provine once had a lab member who had been part of the Army Special Forces. As part of his research, he decided to look at soldiers who were preparing to jump from an airplane for the first time. The incidence of yawning went up just before they made their way to the cabin door. A yawn, Provine believes, may simply signal a change of physiological state: a way to help our mind and body transition from one behavioral state to another—“sleep to wakefulness, wakefulness to sleep, anxiety to calm, boredom to alertness.” So, rather than condemn poor Sasha, we may be better off praising her: in yawning, her body may have been making an effort to reëngage itself rather than succumb to fatigue or hunger.

A yawn, Provine believes, may simply signal a change of physiological state: a way to help our mind and body transition from one behavioral state to another—“sleep to wakefulness, wakefulness to sleep, anxiety to calm, boredom to alertness.” So, rather than condemn poor Sasha, we may be better off praising her: in yawning, her body may have been making an effort to reëngage itself rather than succumb to fatigue or hunger.

Yet the idea that we yawn when we’re about to change states is unlikely to be the whole story, for one simple reason: we yawn, most reliably of all, when we see or hear others yawning—whether or not we happen to be feeling particularly drowsy or bored or anxious or hungry ourselves. It’s a phenomenon known as contagious yawning. We also yawn when we so much as think about yawning: in one of Provine’s studies, eighty-eight per cent of people who were instructed to think of yawns yawned themselves within thirty minutes. We yawn when we read about it. “One reason my enthusiasm for studying contagion diminished is because everything causes yawning,” Provine says. (Are you yawning yet?)

(Are you yawning yet?)

Why are yawns so contagious? Does the fact that we catch them from one another shed light on their underlying function? One possibility is that contagious yawning serves as a way of showing empathy. While all vertebrate mammals experience spontaneous yawning, only humans and our closest relatives, chimpanzees, seem to experience the contagion effect—a sign that there may be a deeper social meaning to the experience. What’s more, while spontaneous yawning occurs in the womb, contagious yawning develops only later in life, as does empathy. Children younger than five don’t yawn any more often when watching videos of yawns than they would normally.

Proponents of the empathy theory cite evidence from studies of closeness: how close we feel to someone affects how likely we are to yawn when they do. We’re more likely to catch a yawn from a family member versus a friend, a friend versus an acquaintance, and an acquaintance versus a stranger. Recent evidence suggests that the effect extends to race: we catch yawns more easily from members of our own race than from members of different races. Chimpanzees and bonobos share this pattern of favoritism. In one recent study, Frans de Waal and Matthew Campbell had two groups of chimpanzees watch a series of videos. In some videos, they saw familiar chimpanzees either yawning or resting, and in others they saw unfamiliar chimpanzees doing the same thing. Both groups yawned more frequently when watching their own group members yawn. A similar pattern was observed in bonobos, who yawned more frequently the stronger their social bond with the yawner. Some scientists cite further evidence from studies of subjects with schizophrenia and autism: in both cases, contagious yawning is diminished, though spontaneous yawning remains intact.

Chimpanzees and bonobos share this pattern of favoritism. In one recent study, Frans de Waal and Matthew Campbell had two groups of chimpanzees watch a series of videos. In some videos, they saw familiar chimpanzees either yawning or resting, and in others they saw unfamiliar chimpanzees doing the same thing. Both groups yawned more frequently when watching their own group members yawn. A similar pattern was observed in bonobos, who yawned more frequently the stronger their social bond with the yawner. Some scientists cite further evidence from studies of subjects with schizophrenia and autism: in both cases, contagious yawning is diminished, though spontaneous yawning remains intact.

An American psychologist explained the phenomenon of yawning by the need to warn of danger - Gazeta.Ru

An American psychologist explained the phenomenon of yawning by the need to warn of danger - Gazeta.Ru | News

close

100%

American psychologist Andrew Gallup put forward a new theory explaining the origin of yawning in humans and other mammals. According to this scientist, yawning developed as a signal within society, which warns fellow tribesmen that one or another of its members is losing vigilance and may need additional protection from predators. An article about this was published in the journal Animal Behavior .

According to this scientist, yawning developed as a signal within society, which warns fellow tribesmen that one or another of its members is losing vigilance and may need additional protection from predators. An article about this was published in the journal Animal Behavior .

Many previous studies attempting to answer the question of why people yawn have also linked yawning to some kind of evolutionary acquisition. "Contagious" yawning may have been spreading some important signals among different social groups. Speculation has also been popular that animals yawn to replenish oxygen, cool their brains, or even exercise their lungs more often.

If yawning did develop as a social signal designed to warn other members of the collective that an individual has become less vigilant, then this may also explain the phenomenon of "contagious yawning" - a reflex yawn after we see or hear a yawn another person, this may further signal the need to redouble vigilance among different groups of social animals. nine0003

nine0003

Considering that this behavior developed on the African plains hundreds of thousands of years ago and is no longer relevant to modern humans, it is possible that yawning may eventually disappear. Previous analysis has already shown a positive correlation between yawn duration and brain size, which means that the larger the brain, the more actively its owner yawns.

Subscribe to Gazeta.Ru in News, Zen and Telegram.

To report a bug, highlight text and press Ctrl+Enter

News

Zen

Telegram

Maria Degtereva

New life from the New Year

About holiday promises

Marina Yardaeva

A healthy economy does not need children

Why working after school is a bad idea

Georgy Bovt

From a sick head to a healthy one

About how biotechnology will change society and whether it will make it better

Alena Solntseva

Points behind bars

About upcoming changes for prisoners

Georgy Malinetsky

Say a word about a poor associate professor

About remuneration in universities

Error found?

Close

Thank you for your message, we will fix it soon.

Continue reading

The oldest riddle: why do we yawn?

- David Robson

- BBC Future

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter to help you understand what's going on.

Image copyright Getty

For two millennia, scientists have been trying to figure out why we yawn. Could a recent theory shed some light on this mystery? Correspondent BBC Future tried to figure it out.

Could a recent theory shed some light on this mystery? Correspondent BBC Future tried to figure it out.

While talking with Robert Provin, a psychologist at the University of Maryland in Baltimore (USA), I suddenly felt an irresistible desire rising from the very depths of my body. The more I tried to fight it, the stronger it became - until it took over me completely. By this point, I was already thinking only about how to restrain myself and not yawn. I couldn't think of anything else.

Robert Provin says that this happens all the time with his interlocutors. During his lectures, he often notices that most of the people in the audience sit with their mouths open and their nostrils flaring. Luckily, as the author of Strange Behavior: Yawning, Hiccups, Laughing, and More, he doesn't take offense at all. nine0003

"My lecture only benefits from this," he says.

"I'm speaking and at some point I notice that the audience starts to yawn. And then I ask people to experiment with their yawning - close their lips or draw in air through clenched teeth. Or try to yawn with their nose pinched," explains the scientist.

And then I ask people to experiment with their yawning - close their lips or draw in air through clenched teeth. Or try to yawn with their nose pinched," explains the scientist.

Image copyright, Getty

Image caption,American Christy Koval yawned at the Sydney Olympics. Nerves?

With the help of experiments like this, Robert Provin has been trying to solve this riddle for many years - why do we yawn? We all know that fatigue, boredom, or someone else's presence can cause us to yawn incessantly. But how does it serve our body, what is its meaning? nine0003

When Robert Provin first started working on this problem in the late 1980s, he wrote that yawning is the most mysterious function of the human body. Nearly three decades later, we may be closer to the answer. But the scientific community, however, is still arguing about which answer would be more correct.

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next. nine0003

episodes

The End of History Podcast

Many believe that Hippocrates was the first to explore the phenomenon of yawning 2,500 years ago. The famous ancient Greek physician believed that yawning helps the body get rid of harmful air, especially at elevated temperatures.

"Like large volumes of steam escaping from cauldrons of boiling water, the air accumulated in the body comes out of the mouth when the body temperature rises," wrote Hippocrates.

Variations of this explanation prevailed in Europe until the 19th century, when scientists suggested that yawning aided breathing by increasing the supply of oxygen to the circulatory system and stimulating the removal of carbon dioxide from it. nine0003

nine0003

If this were true, people would probably yawn more or less regularly, depending on the level of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the surrounding air. But when Robert Provin, determined to test this theory, invited volunteers to inhale various mixtures of gases, this did not affect the frequency of yawns in any way.

Many researchers have drawn attention to the contagious nature of yawns. It's true, I personally felt it in the course of communication with Robert Provin.

image copyrightThinkstock

Image caption,Yawning is highly contagious - once you start...

"About half of the people who see someone yawn start yawning too," he says. "It's so contagious that anything associated with yawning can cause such a reaction. It is enough to see or hear someone else yawn, or even just read about it. "

For this reason, some researchers have questioned whether yawning is not a primitive form of communication. If so, what information does it convey? nine0003

If so, what information does it convey? nine0003

When we yawn, we often feel tired. Therefore, one of the assumptions is that yawning helps to set the biological clocks of others to a single regimen.

"In my opinion, the most likely signaling role of a yawn is to help synchronize the behavior of a social group. Get everyone to fall asleep at about the same time," says Christian Hesse of the University of Bern, Switzerland. "Having a common routine, The group is able to work more effectively during the day." nine0003

But we yawn not only from fatigue, but also from stress. Olympians suddenly begin to yawn just before a race, and musicians often can't help but yawn before a concert. Therefore, some researchers, including Provin, believe that movements that strain the jaw muscles may play a role in rebooting the brain. When you start to feel sleepy, they keep you alert, and when something distracts you, these movements help you focus.

Image copyright Thinkstock

Image captionIs yawning a signal to others? All sleep!

By spreading in a group, contagious yawns can help everyone achieve the same level of attention, for example, increase everyone's alertness. The mechanism is not entirely understood, although French researcher Olivier Valusinsky suggested that yawning helps pump cerebrospinal fluid around the brain. This, in turn, increases neural activity.

The mechanism is not entirely understood, although French researcher Olivier Valusinsky suggested that yawning helps pump cerebrospinal fluid around the brain. This, in turn, increases neural activity.

There are many different explanations contradicting one another, and therefore it is still very far from a single theory that unites all these investigations. nine0003

But, at least in recent years, an idea has emerged that has the potential to reconcile all the contradictions and paradoxes and turn them into a single convincing theory.

Andrew Gallup, now at the State University of New York at Oneonta (USA), while preparing for his bachelor's degree, became interested in the idea that yawning might be a way to cool the brain.

Sharp movements of the jaw cause increased blood circulation in the region of the skull, which removes excess heat. A deep breath brings cool air into the paranasal sinuses and the area of the carotid artery leading to the brain, says this researcher. nine0003

nine0003

Image copyright, Getty

Image caption,Bill Clinton's speech at the UN made Fidel Castro yawn. Pumping air through the nasal cavities should cause the mucus covering them to evaporate, which should also cool the head like an air conditioning system.

To test this theory, obviously, you need to see how often people yawn at different temperatures. Gallup found that under normal conditions, approximately 48% of people feel the urge to yawn. But when a cold compress was placed on the participants' foreheads, that number dropped to 9.%.

Active breathing through the nose, which can also cool the brain, proved to be even more effective, completely removing the urge to yawn. This study, by the way, gives us a hint on how to deal with an unexpected bout of yawning in an inappropriate situation.

Perhaps the best confirmation of the correctness of Andrew Gallup were the stories of two women who turned to the scientist immediately after the publication of his work. Both suffered from pathological bouts of yawning, often lasting up to an hour.

Both suffered from pathological bouts of yawning, often lasting up to an hour.

"It put them out of action for a long time and interfered with their normal life," says Andrew Gallup. "They had to retire somewhere on the sidelines, and all this negatively affected their professional and personal life."

Image copyright, Getty

Image caption,Margaret Thatcher couldn't help but yawn during a European security meeting

Both women found that the only way to cope with an attack was to take a dip in cold water. Inspired by this information, Gallup asked them to conduct a small experiment - to measure the temperature in the mouth with an ordinary thermometer before and after bouts of yawning. As he expected, immediately before the attack, the temperature in the mouth was elevated, and the attack of yawning itself continued until the temperature in the mouth dropped to 37C. nine0003

This was an important discovery because the assumption that yawning cools the brain explained why many other seemingly unrelated circumstances lead to yawning.

Our body temperature usually rises before and after sleep. Brain cooling can help us focus: it wakes us up when we are bored or distracted. And spreading to those present, yawning can help focus the entire group.

Andrew Gallup's theory was wary of many of his colleagues. "The Gallup group was unable to provide any convincing experimental evidence for this theory," says Christian Hess. nine0003

Image copyright, Getty

Image caption,US Secretary of State Warren Christopher couldn't help but yawn during Madeleine Albright's speech at UN

First of all, Gallup's critics point out that he didn't measure brain temperature fluctuations directly. He himself claims to have found the expected fluctuations in brain temperature in experimental rats.

Robert Provin, however, is more optimistic. He believes that Gallup's theory may be the right explanation for how yawning helps the brain work. nine0003

But even if Andrew Gallup could find a theory that could unify all the previous explanations, there are still many mysteries. For example, why do fetuses yawn in the mother's womb?

For example, why do fetuses yawn in the mother's womb?

It is possible that they are simply preparing for an independent life. Maybe yawning somehow helps the growth of the fetus. For example, it develops articulation of the jaw joints or promotes an increase in lung capacity, suggests Robert Provin. If this is true, then, according to the scientist, the function of yawning in the womb is more important than after the birth of the child. nine0003

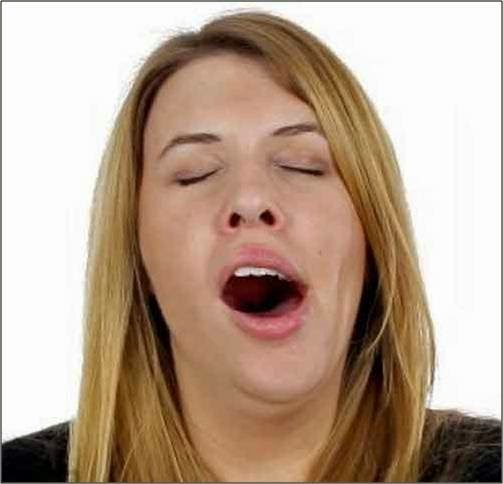

Robert Provin also points out strange parallels between yawning and sex. (This, by the way, also applies to some other functions, such as sneezing) The facial expression of a person in such cases is surprisingly similar. Take a look at this photo and you will understand what I'm talking about.

Image copyright Thinkstock

Image captionIs this man yawning? Or... doing something more intimate?

Just like sex, yawning and sneezing involve a preparation phase that ends with a pleasant release. nine0003

nine0003

"If this business starts, it goes on to the end, no one wants to interrupt this process," notes Provin. For this reason, he wonders if the same mechanism of nervous activity is behind these so different functions.

"Mother Nature doesn't constantly reinvent the wheel," he says, pointing out that some antidepressants cause orgasms when you yawn.

In the end, the desire to yawn was too strong for me during our conversation with Robert Provin. The day was sunny and warm, so perhaps the urge to yawn had the noble purpose of protecting my brain from overheating during this fascinating conversation. The relief I experienced as a result of a good yawn completely justified all my desperate attempts to keep my mouth shut.

I can bet that by this moment you yourself already wanted to yawn once or twice. According to Robert Provin, the article on yawning may well cause it. So don't be shy. Remember that when you open your mouth in a sweet yawn, you turn on one of the most mysterious functions of your body, over which mankind has been struggling since ancient times.