Obsessive compulsive shopping

A review of compulsive buying disorder

World Psychiatry. 2007 Feb; 6(1): 14–18.

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Compulsive buying disorder (CBD) is characterized by excessive shopping cognitions and buying behavior that leads to distress or impairment. Found worldwide, the disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 5.8% in the US general population. Most subjects studied clinically are women (~80%), though this gender difference may be artifactual. Subjects with CBD report a preoccupation with shopping, prepurchase tension or anxiety, and a sense of relief following the purchase. CBD is associated with significant psychiatric comorbidity, particularly mood and anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, eating disorders, and other disorders of impulse control. The majority of persons with CBD appear to meet criteria for an Axis II disorder, although there is no special "shopping" personality. Compulsive shopping tends to run in families, and these families are filled with mood and substance use disorders.

There are no standard treatments. Psychopharmacologic treatment studies are being actively pursued, and group cognitive-behavioral models have been developed and are promising. Debtors Anonymous, simplicity circles, bibliotherapy, financial counseling, and marital therapy may also play a role in the management of CBD.

Keywords: Compulsive shopping, compulsive buying, impulse control disorders

Compulsive buying disorder (CBD) was first described clinically in the early 20th century by Bleuler (1) and Kraepelin (2), both of whom included CBD in their textbooks. Bleuler writes: "As a last category Kraepelin mentions the buying maniacs (oniomaniacs) in whom even buying is compulsive and leads to senseless contraction of debts with continuous delay of payment until a catastrophe clears the situation a little - a little bit never altogether because they never admit to their debts" (1). Bleuler described CBD as an example of a "reactive impulse", or "impulsive insanity", which he grouped alongside kleptomania and pyromania.

CBD attracted little attention throughout the 20th century except among consumer behaviorists (3-6) and psychoanalysts (7-9). Interest was revived in the early 1990s, when clinical case series from three independent research groups appeared (10-12). The disorder has been described worldwide, with reports coming from the US (10-12), Canada (5), England (4), Germany (6), France (13), and Brazil (14).

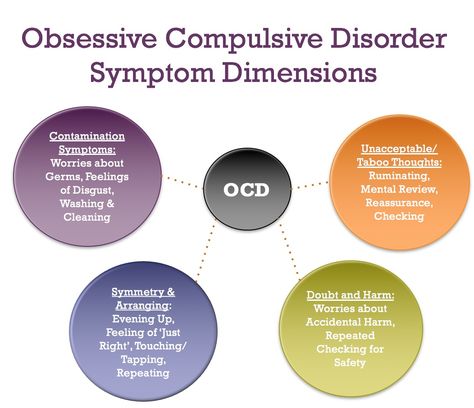

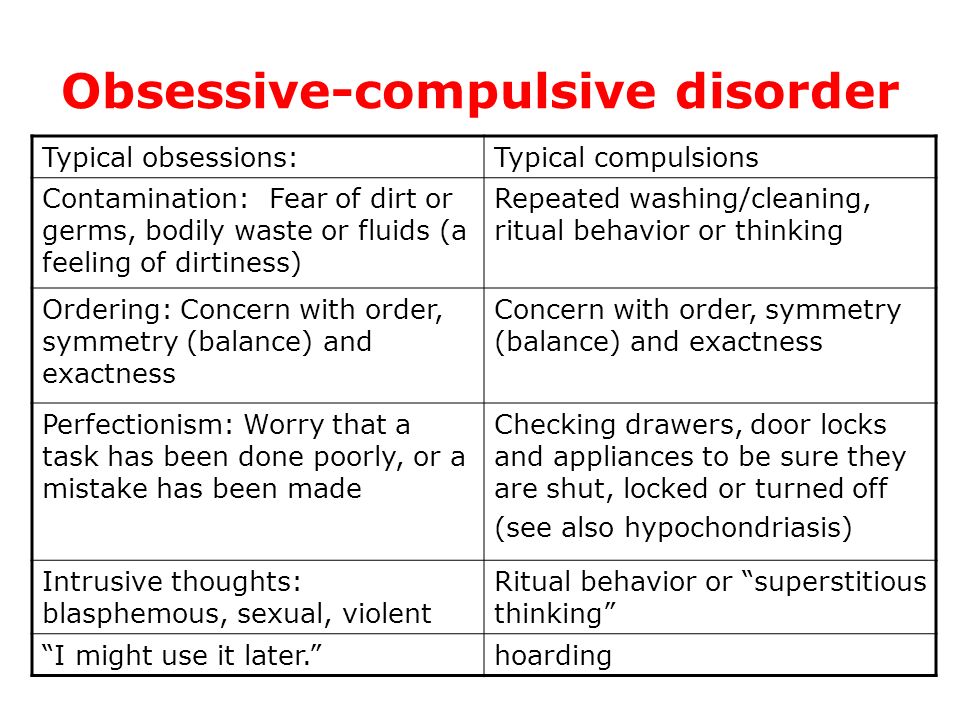

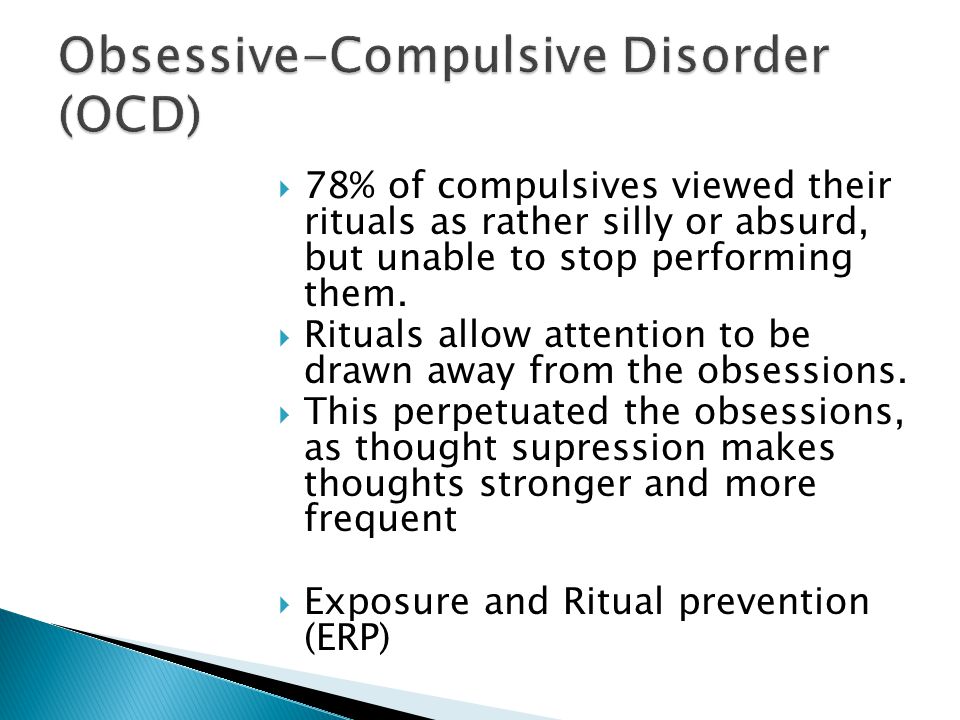

The appropriate classification of CBD continues to be debated. Some researchers have linked CBD to addictive disorders (15), while others have linked it to obsessive-compulsive disorder (16), and still others to mood disorders (17). While not included in DSM-IV (18), CBD was included in DSM-III-R (19) as an example of an "impulsecontrol disorder not otherwise specified". Research criteria have been developed that emphasize its cognitive and behavioral aspects (10). Some writers have criticized attempts to categorize CBD as an illness, which they see as part of a trend to "medicalize" behavioral problems (20). Yet, this approach ignores the reality of CBD, and both trivializes and stigmatizes attempts to understand or treat the disorder.

Yet, this approach ignores the reality of CBD, and both trivializes and stigmatizes attempts to understand or treat the disorder.

Koran et al (21) recently estimated the point prevalence of CBD to be 5.8% of respondents, based on results from a random telephone survey of 2,513 adults conducted in the US. Earlier, Faber and O'Guinn (22) had estimated the prevalence of CBD to fall between 2% and 8% of the general population of Illinois. Both research groups had used the Compulsive Buying Scale (CBS) (23) to identify compulsive buyers. Other surveys have reported figures ranging from 12% to 16% (24,25). There is no evidence that CBD has increased in prevalence in the past few decades.

Community based and clinical surveys suggest that 80% to 95% of persons with CBD are women (10-12,23). The reported gender difference could be artifactual: women readily acknowledge that they enjoy shopping, whereas men are more likely to report that they "collect". The report of Koran et al (21) suggests that this may be the case: in their survey, a near equal percentage of men and women met criteria for CBD (5. 5% and 6.0%, respectively). However, Dittmar (26) concluded from a general population survey in the United Kingdom, in which 92% of respondents considered compulsive shoppers were women, that the gender difference is real and is not an artifact of men being underrepresented in samples.

5% and 6.0%, respectively). However, Dittmar (26) concluded from a general population survey in the United Kingdom, in which 92% of respondents considered compulsive shoppers were women, that the gender difference is real and is not an artifact of men being underrepresented in samples.

The age of onset of CBD appears to be in the late teens or early twenties (11,12,27), though McElroy et al (10) reported a mean age at onset of 30 years. It may be that the age of onset corresponds with emancipation from the home, and the age at which people first establish credit accounts.

There are no careful longitudinal studies of CBD, but the majority of subjects studied by Schlosser et al (12) and McElroy et al (10) describe their course as continuous. Aboujaoude et al (28) suggested that persons with CBD who responded to treatment with citalopram were likely to remain in remission during one-year follow-up, a finding that suggests that treatment could alter the natural history of the disorder. The authors' personal observation is that subjects with CBD typically report decades of compulsive shopping behavior at the time of presentation, although it might be argued that clinical samples are biased in favor of severity.

The authors' personal observation is that subjects with CBD typically report decades of compulsive shopping behavior at the time of presentation, although it might be argued that clinical samples are biased in favor of severity.

There is some evidence that CBD runs in families and that within these families mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders are excessive. McElroy et al (8) reported that, of 18 individuals with CBD, 17 had one or more first-degree relatives (FDRs) with major depression, 11 with an alcohol or drug use disorder, and three with an anxiety disorder. Three had relatives with CBD. Black et al (29) used the family history method to assess 137 FDRs of 33 persons with CBD. FDRs were significantly more likely than those in a comparison group to have depression, alcoholism, a drug use disorder, "any" psychiatric disorder, and "more than one psychiatric disorder". CBD was identified in 9.5% of the FDRs of the CBD probands (CBD was not assessed in the comparison group). In molecular genetic studies, Devor et al (30) failed to find an association between two serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms and CBD, while Comings (31) reported an association of CBD with the DRD1 receptor gene.

In molecular genetic studies, Devor et al (30) failed to find an association between two serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms and CBD, while Comings (31) reported an association of CBD with the DRD1 receptor gene.

Persons with CBD are preoccupied with shopping and spending, and devote significant time to these behaviors. While it might be argued that a person could be a compulsive shopper and not spend, and confine his or her interest to window shopping, this pattern is uncommon. The author's personal observation is that the two aspects - shopping and spending - are intertwined. Persons with CBD often describe an increasing level of urge or anxiety that can only lead to a sense of completion when a purchase is made.

The author has been able to identify four distinct phases of CBD: 1) anticipation; 2) preparation; 3) shopping; and 4) spending. In the first phase, the person with CBD develops thoughts, urges, or preoccupations with either having a specific item, or with the act of shopping. In the second phase, the person prepares for shopping and spending. This can include decisions on when and where to go, on how to dress, and even which credit cards to use. Considerable research may have taken place about sale items, new fashions, or new shops. The third phase involves the actual shopping experience, which many individuals with CBD describe as intensely exciting, and can even lead to a sexual feeling (12). Finally, the act is completed with a purchase, often followed by a sense of let down, or disappointment with oneself (21). In a study of the antecedents and consequences of CBD, Miltenberger et al (32) reported that negative emotions (e.g., depression, anxiety, boredom, self-critical thoughts, anger) were the most commonly cited antecedents to CBD, while euphoria or relief from the negative emotions were the most common consequence.

In the second phase, the person prepares for shopping and spending. This can include decisions on when and where to go, on how to dress, and even which credit cards to use. Considerable research may have taken place about sale items, new fashions, or new shops. The third phase involves the actual shopping experience, which many individuals with CBD describe as intensely exciting, and can even lead to a sexual feeling (12). Finally, the act is completed with a purchase, often followed by a sense of let down, or disappointment with oneself (21). In a study of the antecedents and consequences of CBD, Miltenberger et al (32) reported that negative emotions (e.g., depression, anxiety, boredom, self-critical thoughts, anger) were the most commonly cited antecedents to CBD, while euphoria or relief from the negative emotions were the most common consequence.

Individuals with CBD tend to shop by themselves, although some will shop with friends who may share their interest in shopping (11,12). In general, CBD is a private pleasure which could lead to embarrassment if someone not similarly interested in shopping accompanied them. Shopping may occur in just about any venue, ranging from high fashion department stores and boutiques to consignment shops or garage sales. Income has relatively little to do with the existence of CBD: persons with a low income can still be fully preoccupied by shopping and spending, although their level of income will lead them to shop at a consignment shop rather than a department store.

In general, CBD is a private pleasure which could lead to embarrassment if someone not similarly interested in shopping accompanied them. Shopping may occur in just about any venue, ranging from high fashion department stores and boutiques to consignment shops or garage sales. Income has relatively little to do with the existence of CBD: persons with a low income can still be fully preoccupied by shopping and spending, although their level of income will lead them to shop at a consignment shop rather than a department store.

Typical items purchased by persons with CBD include (in descending order) clothing, shoes, compact discs, jewelry, cosmetics, and household items (11,12,32). Individually, the items purchased by compulsive shoppers tend not to be particularly expensive, but the author has observed that many compulsive shoppers buy in quantity resulting in out of control spending. Anecdotally, patients often report buying a product based on its attractiveness or because it was a bargain. In the study by Christenson et al (11), compulsive shoppers reported spending an average of $110 during a typical shopping episode compared with $92 reported in the study by Schlosser et al (12).

In the study by Christenson et al (11), compulsive shoppers reported spending an average of $110 during a typical shopping episode compared with $92 reported in the study by Schlosser et al (12).

Although research has not identified gender specific buying patterns, in the author's experience men tend to have a greater interest than women in electronic, automotive, or hardware goods. Like women, they are also interested in clothing, shoes, and compact discs.

Subjects generally are willing to acknowledge that CBD is problematic. Schlosser et al (10) reported that 85% of their subjects expressed concern with their CBD-related debts, and that 74% felt out of control while shopping. In the study by Miltenberger et al (32), 68% of persons with CBD reported that it negatively affected their relationships. Christenson et al (11) reported that nearly all of their subjects (92%) tried to resist their urges to buy, but were rarely successful. The subjects indicated that 74% of the time they experienced an urge to buy, the urge resulted in a purchase.

CBD tends to occur year round, although it may be more problematic during the Christmas or other important holidays, and around the birthdays of family members and friends (12). Schlosser et al (12) found that subjects reported a range of behaviors regarding the outcome of a purchase, including returning the item, failing to remove the item from the packaging, selling the item, or even giving it away.

In a study of 44 subjects with CBD, Black et al (33) reported that greater severity was associated with lower gross income, less likelihood of having an income above the median, and spending a lower percentage of income on sale items. Subjects with more severe CBD were also more likely to have comorbid Axis I or Axis II disorders. These data suggest that the most severe forms of CBD are found in persons with low incomes who have little ability to control or to delay their urge to make impulsive purchases.

Persons with CBD frequently meet criteria for Axis I disorders, particularly mood disorders (21-100%) (27,34), anxiety disorders (41-80%) (10,12), substance use disorders (21-46%) (11,29), and eating disorders (8-35%) (10,27). Disorders of impulse control are also relatively common in these individuals (21-40%) (10,11).

Disorders of impulse control are also relatively common in these individuals (21-40%) (10,11).

Schlosser et al (12) found that nearly 60% of subjects with CBD met criteria for at least one Axis II disorder. While there was no special "shopping" personality, the most frequently identified personality disorders were the obsessive-compulsive (22%), avoidant (15%), and borderline (15%) types. Krueger (7), a psychoanalyst, described four patients who he observed to have aspects of narcissistic character pathology.

The etiology of CBD is unknown, though speculation has settled on developmental, neurobiological, and cultural influences. Psychoanalysts (7-9) have suggested that early life events, such as sexual abuse, are causative factors. Yet, no special or unique family constellation or pattern of early life events has been identified in persons with CBD.

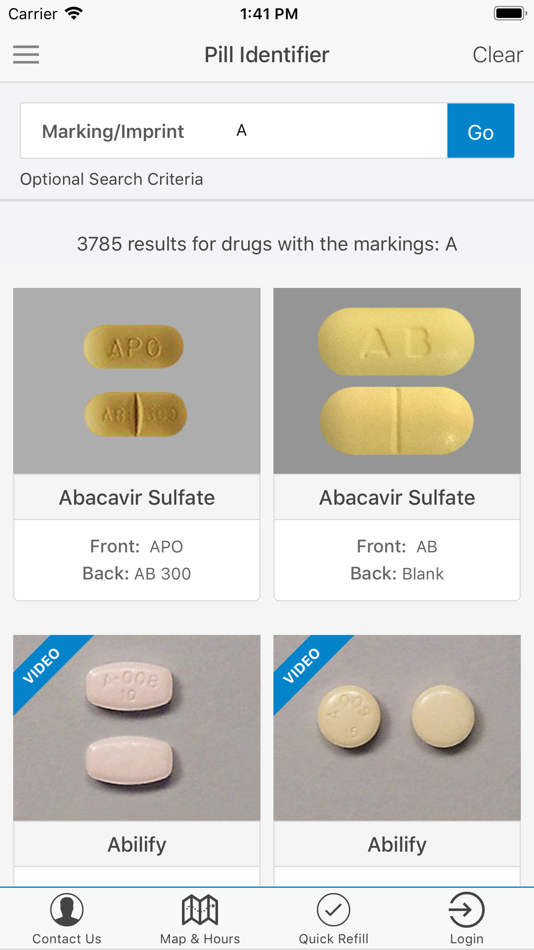

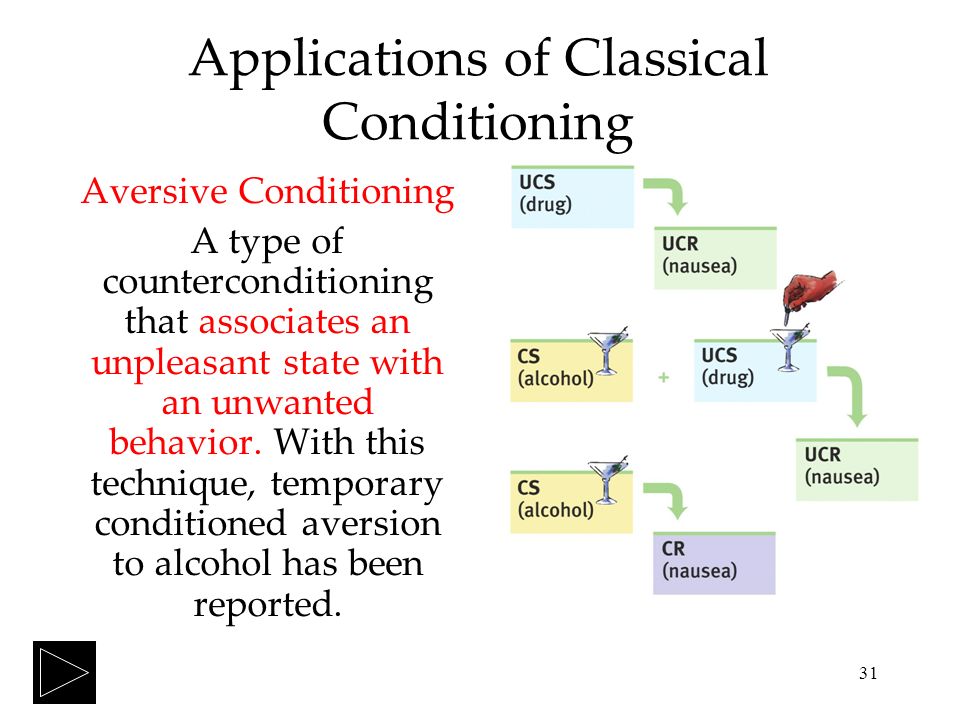

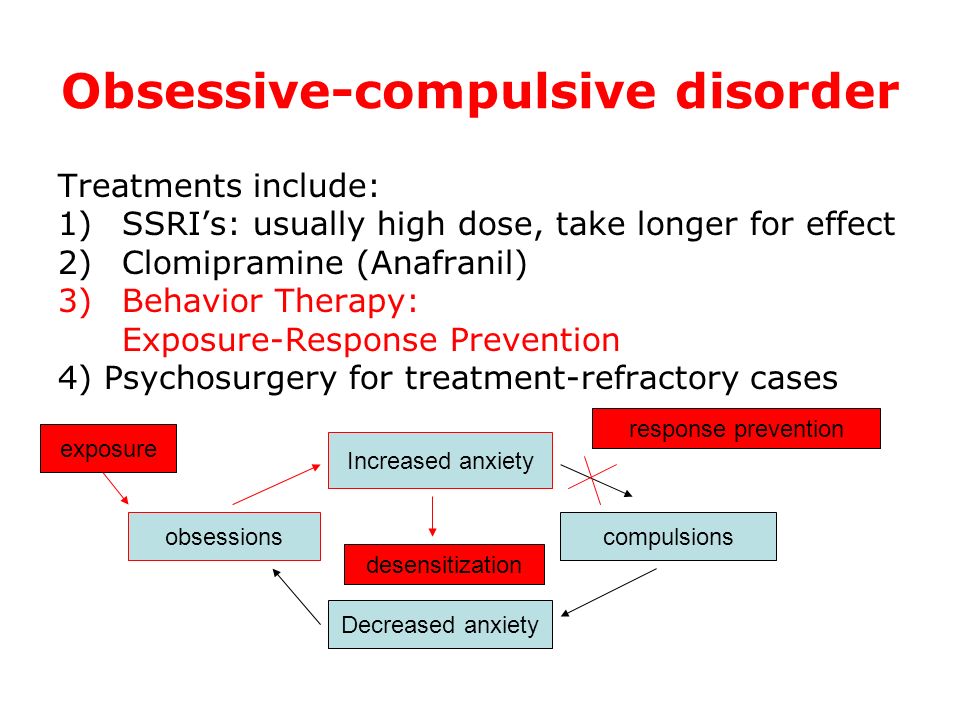

Neurobiological theories have centered on disturbed neurotransmission, particularly involving the serotonergic, dopaminergic, or opioid systems. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been used to treat CBD (27,34- 38), in part because investigators have noted similarities between CBD and obsessive-compulsive disorder, a disorder known to respond to SSRIs. Dopamine has been theorized to play a role in "reward dependence", which has been claimed to foster "behavioral addictions" (e.g., CBD, pathological gambling) (39). Case reports suggesting benefit from the opiate antagonist naltrexone have led to speculation about the role of opiate receptors (40,41). There is currently no direct evidence to support the role of these neurotransmitter systems in the etiology of CBD.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been used to treat CBD (27,34- 38), in part because investigators have noted similarities between CBD and obsessive-compulsive disorder, a disorder known to respond to SSRIs. Dopamine has been theorized to play a role in "reward dependence", which has been claimed to foster "behavioral addictions" (e.g., CBD, pathological gambling) (39). Case reports suggesting benefit from the opiate antagonist naltrexone have led to speculation about the role of opiate receptors (40,41). There is currently no direct evidence to support the role of these neurotransmitter systems in the etiology of CBD.

Cultural mechanisms have been proposed to recognize the fact that CBD occurs mainly in developed countries (42). Elements which appear necessary for the development of CBD include the presence of a market-based economy, the availability of a wide variety of goods, disposable income, and significant leisure time. For these reasons, CBD is unlikely to occur in poorly developed countries, except among the wealthy elite (Imelda Marcos and her many shoes come to mind).

The goal of assessment is to identify CBD through inquiries regarding the person's attitudes and behaviors towards shopping and spending (43). Inquiries might include: "Do you feel overly preoccupied with shopping and spending?"; "Do you ever feel that your shopping behavior is excessive, inappropriate or uncontrolled?"; "Have your shopping desires, urges, fantasies, or behaviors ever been overly time consuming, caused you to feel upset or guilty, or lead to serious problems in your life such as financial or legal problems or the loss of a relationship?".

Clinicians should note past psychiatric treatment, including medications, hospitalizations, and psychotherapy. A history of physical illness, surgical procedures, drug allergies, or medical treatment is important to note, because it may help rule out medical explanations as a cause of the CBD (e.g., neurological disorders, brain tumors). Bipolar disorder needs to be ruled out as a cause of the excessive shopping and spending. Typically, the manic patient's unrestrained spending corresponds to manic episodes, and is accompanied by euphoric mood, grandiosity, unrealistic plans, and often a giddy, expansive affect. The pattern of shopping and spending in the person with CBD lacks the periodicity seen with bipolar patients, and suggests an ongoing preoccupation.

Typically, the manic patient's unrestrained spending corresponds to manic episodes, and is accompanied by euphoric mood, grandiosity, unrealistic plans, and often a giddy, expansive affect. The pattern of shopping and spending in the person with CBD lacks the periodicity seen with bipolar patients, and suggests an ongoing preoccupation.

Normal buying behavior should also be ruled out. In the US and other developed countries, shopping is a major pastime, particularly for women, and frequent shopping does not necessarily constitute evidence in support of a diagnosis of CBD. Normal buying can sometimes take on a compulsive quality, particularly around special holidays or birthdays. Persons who receive an inheritance or win a lottery may experience shopping sprees as well.

Several instruments have been developed to either identify CBD or rate its severity. The CBS (23), already mentioned, consists of seven items representing specific behaviors, motivations, and feelings associated with compulsive buying, and reliably distinguishes normal buyers from those with CBD. Edwards (44) has developed a useful 13-item scale that assesses important experiences and feelings about shopping and spending. Monahan et al (45) modified the Yale Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale to create the YBOCS-Shopping Version (YBOCS-SV) to assess cognitions and behaviors associated with CBD. This 10-item scale rates time involved, interference, distress, resistance, and degree of control for both cognitions and behaviors. The instrument is designed to measure severity of CBD, and change during clinical trials.

Edwards (44) has developed a useful 13-item scale that assesses important experiences and feelings about shopping and spending. Monahan et al (45) modified the Yale Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale to create the YBOCS-Shopping Version (YBOCS-SV) to assess cognitions and behaviors associated with CBD. This 10-item scale rates time involved, interference, distress, resistance, and degree of control for both cognitions and behaviors. The instrument is designed to measure severity of CBD, and change during clinical trials.

There are no evidence-based treatments for CBD. In recent years, treatment studies of CBD have focused on the use of psychotropic medication (mainly antidepressants) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Interest in CBT has largely replaced earlier interest in psychodynamic therapies. Several competing CBT models have been developed, the most successful involving the use of group treatment (46-49). The first use of group therapy was described by Damon (46). Subsequent group models were developed by Burgard and Mitchell (47), Villarino et al (48), and more recently by Benson and Gengler (49). Mitchell et al (50) reported that their group CBT model produced significant improvement compared to a wait list in a 12-week pilot study; improvement was maintained during a 6-months follow-up. Benson (51) has recently developed a comprehensive self-help program which combines cognitive- behavioral strategies with self-monitoring. A detailed workbook, a shopping diary, and a CD-ROM are included.

Subsequent group models were developed by Burgard and Mitchell (47), Villarino et al (48), and more recently by Benson and Gengler (49). Mitchell et al (50) reported that their group CBT model produced significant improvement compared to a wait list in a 12-week pilot study; improvement was maintained during a 6-months follow-up. Benson (51) has recently developed a comprehensive self-help program which combines cognitive- behavioral strategies with self-monitoring. A detailed workbook, a shopping diary, and a CD-ROM are included.

Several self-help books (bibliotherapy) are available (52- 54), and may be helpful to some persons with CBD. Debtors Anonymous, patterned after Alcoholics Anonymous, is a voluntary, lay-run group that provides an atmosphere of mutual support and encouragement for those with substantial debts. Simplicity circles are available in some US cities; these voluntary groups encourage people to adopt a simple lifestyle, and to abandon their CBD (55). Many subjects with CBD develop substantial financial problems, and may benefit from financial counseling (56). The author has seen cases in which a financial conservator has been appointed to control the patient's finances, and appears to have helped. While a conservator controls the person's spending, this approach does not reverse his or her preoccupation with shopping and spending. Marriage (or couples) counseling may be helpful, particularly when CBD in one member of the dyad has disrupted the relationship (57).

The author has seen cases in which a financial conservator has been appointed to control the patient's finances, and appears to have helped. While a conservator controls the person's spending, this approach does not reverse his or her preoccupation with shopping and spending. Marriage (or couples) counseling may be helpful, particularly when CBD in one member of the dyad has disrupted the relationship (57).

Psychopharmacologic treatment studies have yielded mixed results. An early case series suggested that antidepressants could curb CBD (58), and an early open-label trial using fluvoxamine showed benefit (34). Yet, two subsequent randomized controlled trials found that fluvoxamine did no better than placebo (35,36). In another open-label trial (28), citalopram produced substantial improvement. In this particular study, responders to open-label citalopram were then enrolled in a nine-week randomized placebo controlled trial (38). Compulsive shopping symptoms returned in five of eight subjects assigned to placebo compared with none of the seven who continued taking citalopram. By comparison, escitalopram showed little effect for CBD in an identically designed discontinuation trial by the same investigators (39). Grant (40) and Kim (41) have described cases in which persons with CBD improved with naltrexone, suggesting that opiate antagonists might play a role in the treatment of CBD. Interpretation of treatment studies is complicated by the high placebo response rate associated with CBD (ranging to 64%) (35).

By comparison, escitalopram showed little effect for CBD in an identically designed discontinuation trial by the same investigators (39). Grant (40) and Kim (41) have described cases in which persons with CBD improved with naltrexone, suggesting that opiate antagonists might play a role in the treatment of CBD. Interpretation of treatment studies is complicated by the high placebo response rate associated with CBD (ranging to 64%) (35).

The author has developed a set of recommendations (59). First, pharmacologic treatment trials provide little guidance, and patients should be informed that they cannot rely on medication. Further, patients should: a) admit that they have CBD; b) get rid of credit cards and checkbooks, because they are easy sources of funds that fuel the disorder; c) shop with a friend or relative; the presence of a person without CBD will help curb the tendency to overspend; and d) find meaningful ways to spend one's leisure time other than shopping.

1. Bleuler E. New York: Macmillan; 1930. Textbook of psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

New York: Macmillan; 1930. Textbook of psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

2. Kraepelin E. 8th ed. Leipzig: Barth; 1915. Psychiatrie. [Google Scholar]

3. O'Guinn TC. Faber RJ. Compulsive buying: a phenomenological exploration. J Consumer Res. 1989;16:147–157. [Google Scholar]

4. Elliott R. Addictive consumption: function and fragmentation in post-modernity. J Consumer Policy. 1994;17:159–179. [Google Scholar]

5. Valence G. D'Astous A. Fortier L. Compulsive buying: concept and measurement. J Consum Policy. 1988;11:419–433. [Google Scholar]

6. Scherhorn G. Reisch LA. Raab G. Addictive buying in West Germany: an empirical study. J Consum Policy. 1990;13:355–387. [Google Scholar]

7. Krueger DW. On compulsive shopping and spending: a psychodynamic inquiry. Am J Psychother. 1988;42:574–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Lawrence L. The psychodynamics of the compulsive female shopper. Am J Psychoanal. 1990;50:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Winestine MC. Compulsive shopping as a derivative of childhood seduction. Psychoanal Q. 1985;54:70–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Compulsive shopping as a derivative of childhood seduction. Psychoanal Q. 1985;54:70–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. McElroy S., Jr Keck PE., Jr Pope HG, Jr, et al. Compulsive buying: a report of 20 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:242–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Christenson GA. Faber JR. de Zwann M. Compulsive buying: descriptive characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Schlosser S. Black DW. Repertinger S, et al. Compulsive buying: demography, phenomenology, and comorbidity in 46 subjects. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1994;16:205–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Lejoyeux M. Tassain V. Solomon J, et al. Study of compulsive buying in depressed patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:169–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Bernik MA. Akerman D. Amaral JAMS, et al. Cue exposure in compulsive buying. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Krych R. Abnormal consumer behavior: a model of addictive behaviors. Adv Consum Res. 1989;16:745–748. [Google Scholar]

Adv Consum Res. 1989;16:745–748. [Google Scholar]

16. Hollander E, editor. Obsessive-compulsive related disorders. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

17. Lejoyeux M. Andes J. Tassian V, et al. Phenomenology and psychopathology of uncontrolled buying. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;152:1524–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed, revised. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text revision. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

20. Lee S. Mysyk A. The medicalization of compulsive buying. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1709–1718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Koran LM. Faber RJ. Aboujaoude E, et al. Estimated prevalence of compulsive buying in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1806–1812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Faber RJ. O'Guinn TC. Classifying compulsive consumers: advances in the development of a diagnostic tool. Adv Consum Res. 1989;16:147–157. [Google Scholar]

Faber RJ. O'Guinn TC. Classifying compulsive consumers: advances in the development of a diagnostic tool. Adv Consum Res. 1989;16:147–157. [Google Scholar]

23. Faber RJ. O'Guinn TC. A clinical screener for compulsive buying. J Consumer Res. 1992;19:459–469. [Google Scholar]

24. Magee A. Compulsive buying tendency as a predictor of attitudes and perceptions. Adv Consum Res. 1994;21:590–594. [Google Scholar]

25. Hassay DN. Smith CL. Compulsive buying: an examination of consumption motive. Psychol Marketing. 1996;13:741–752. [Google Scholar]

26. Dittmar H. Understanding and diagnosing compulsive buying. In: Coombs R, editor. Addictive disorders: a practical handbook. New York: Wiley; 2004. pp. 411–450. [Google Scholar]

27. Koran LM. Bullock KD. Hartston HJ, et al. Citalopram treatment of compulsive shopping: an open-label study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:704–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Aboujaoude E. Gamel N. Koran LM. A 1-year naturalistic following of patients with compulsive shopping disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:946–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:946–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Black DW. Repertinger S. Gaffney GR, et al. Family history and psychiatric comorbidity in persons with compulsive buying: preliminary findings. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:960–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Devor EJ. Magee HJ. Dill-Devor RM, et al. Serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT) polymorphisms and compulsive buying. Am J Med Genet. 1999;88:123–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Comings DE. The molecular genetics of pathological gambling. CNS Spectrums. 1998;6:20–37. [Google Scholar]

32. Miltenberger RG. Redlin J. Crosby R, et al. Direct and retrospective assessment of factors contributing to compulsive buying. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2003;34:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Black DW. Monahan P. Schlosser S, et al. Compulsive buying severity: an analysis of compulsive buying scale results in 44 subjects. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Black DW. Monahan P. Gabel J. Fluvoxamine in the treatment of compulsive buying. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Monahan P. Gabel J. Fluvoxamine in the treatment of compulsive buying. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Black DW. Gabel J. Hansen J, et al. A double-blind comparison of fluvoxamine versus placebo in the treatment of compulsive buying disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2000;12:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Ninan PT. McElroy SL. Kane CP, et al. Placebo-controlled study of fluvoxamine in the treatment of patients with compulsive buying. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:362–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Koran LM. Chuang HW. Bullock KD, et al. Citalopram for compulsive shopping disorder: an open-label study followed by a double- blind discontinuation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:793–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Koran LM. Escitalopram treatment evaluated in patients with compulsive shopping disorder. Primary Psychiatry. 2005;12:13. [Google Scholar]

39. Holden C. Behavioral addictions; do they exist? Science. 2001;294:980–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Grant JE. Three cases of compulsive buying treated with naltrexone. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2003;7:223–225. [Google Scholar]

41. Kim SW. Opioid antagonists in the treatment of impulse-control disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Black DW. Compulsive buying disorder: definition, assessment, epidemiology and clinical management. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Black DW. Assessment of compulsive buying. In: Benson A, editor. I shop, therefore I am - compulsive buying and the search for self. New York: Aronson; 2000. pp. 191–216. [Google Scholar]

44. Edwards EA. Development of a new scale to measure compulsive buying behavior. Fin Counsel Plan. 1993;4:67–84. [Google Scholar]

45. Monahan P. Black DW. Gabel J. Reliability and validity of a scale to measure change in persons with compulsive buying. Psychiatry Res. 1995;64:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Damon JE. Los Angeles: Price Stein Sloan; 1988. Shopaholics: serious help for addicted spenders. [Google Scholar]

Damon JE. Los Angeles: Price Stein Sloan; 1988. Shopaholics: serious help for addicted spenders. [Google Scholar]

47. Burgard M. Mitchell JE. Group cognitive-behavioral therapy for buying disorders. In: Benson A, editor. I shop, therefore I am - compulsive buying and the search for self. New York: Aronson; 2000. pp. 367–397. [Google Scholar]

48. Villarino R. Otero-Lopez JL. Casto R. Madrid: Ediciones Piramide; 2001. Adicion a la compra: analysis, evaluaction y tratamiento. [Google Scholar]

49. Benson A. Gengler M. Treating compulsive buying. In: Coombs R, editor. Addictive disorders: a practical handbook. New York: Wiley; 2004. pp. 451–491. [Google Scholar]

50. Mitchell JE. Burgard M. Faber R, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for compulsive buying disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1859–1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Benson A. Stopping overshopping - A comprehensive program to help eliminate overshopping. New York: April Benson, 2006 www.stoppingovershopping. com. [Google Scholar]

com. [Google Scholar]

52. Arenson G. Blue Ridge Summit: Tab Books; 1991. Born to spend: how to overcome compulsive spending. [Google Scholar]

53. Catalano EM. Sonenberg N. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications; 1993. Consuming passions - help for compulsive shoppers. [Google Scholar]

54. Wesson C. New York: St. Martin's Press; 1991. Women who shop too much: overcoming the urge to splurge. [Google Scholar]

55. Andrews C. Simplicity circles and the compulsive shopper. In: Benson A, editor. I shop, therefore I am - compulsive buying and the search for self. New York: Aronson; 2000. pp. 484–496. [Google Scholar]

56. McCall K. Financial recovery counseling. In: Benson A, editor. I shop, therefore I am - compulsive buying and the search for self. New York: Aronson; 2000. pp. 457–483. [Google Scholar]

57. Mellan O. Overcoming overspending in couples. In: Benson A, editor. I shop, therefore I am - compulsive buying and the search for self. New York: Aronson; 2000. pp. 341–366. [Google Scholar]

pp. 341–366. [Google Scholar]

58. McElroy S. Satlin A. Pope HG, et al. Treatment of compulsive shopping with antidepressants: a report of three cases. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1991;3:199–204. [Google Scholar]

59. Kuzma J. Black DW. Compulsive shopping - when spending begins to consume the consumer. Current Psychiatry. 2006;7:27–40. [Google Scholar]

5 Patterns of Compulsive Buying

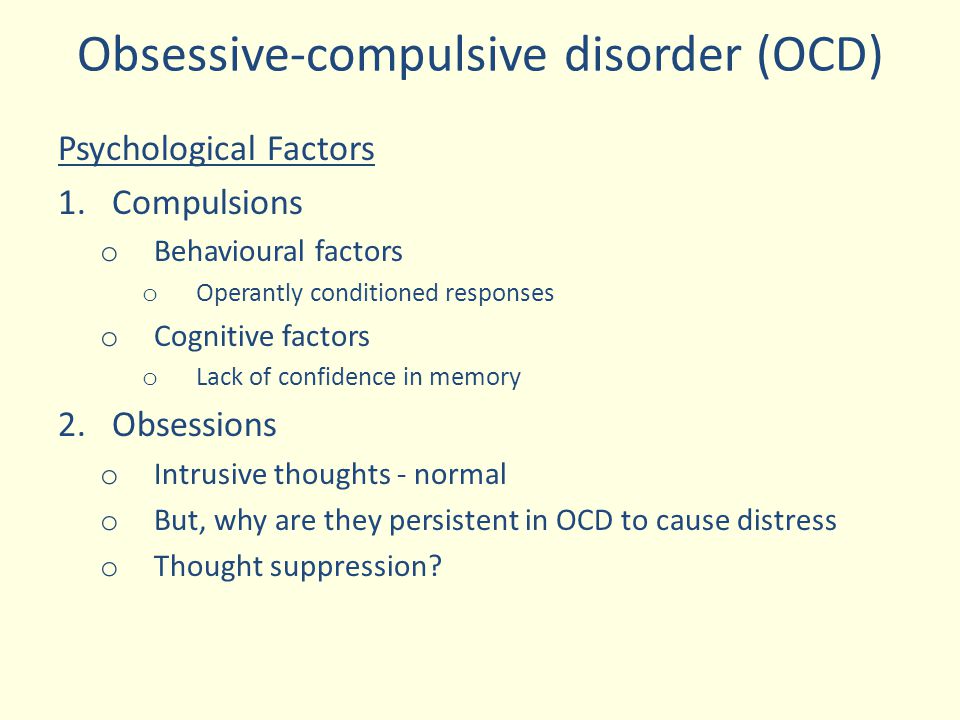

Compulsive behavior refers to the continued repetition of a behavior despite adverse consequences. The compulsions are fuelled by the obsessions (e.g., intrusive thoughts of contaminations). Compulsive buying is characterized by excessive preoccupation or poor impulse control with shopping, and adverse consequences, like marital conflict and financial problems.

About 6% of the U.S. population can be said to have compulsive buying behavior with 80% of compulsive buyers being women. Many women have been socialized from a very young age to enjoy shopping with their mothers and friends (Workman & Paper, 2010). However, compulsive buying is likely to increase for men with the evolution of digital commerce. It is much faster and easier now to find what you are looking for.

However, compulsive buying is likely to increase for men with the evolution of digital commerce. It is much faster and easier now to find what you are looking for.

Compulsive buying is similar to behavioral addiction, such as binge eating and gambling (Lawrence et al., 2014). Compulsive spending frequently co-occurs with other mental illnesses like depression, anxiety, and eating disorders. Unlike other addictions, which take hold in the teens, spending addictions mostly develop in the 30s when people achieve financial independence.

Compulsive buying is not listed as an addiction in the DSM-5. However, the impulse problem appears to share certain characteristics common in addictive disorders (Black, 2012).

1. Impulse purchase. Compulsive buyers often purchase things on impulse that they can do without. And they often try to conceal their shopping habits. Spending without adequate reflection can result in having many unopened items (boxes of shoes or clothes) in their closets as they continue the cycle of buying. Compulsive buyers may develop into hoarders later in life after their products have accumulated with time (Mueller, 2007).

Compulsive buyers may develop into hoarders later in life after their products have accumulated with time (Mueller, 2007).

2. Buyers high. Compulsive shoppers experience a rush of excitement when they buy. The euphoric experience is not from owning something but from the act of buying it. This rush of excitement is often experienced when they see a desirable item and consider buying it. And this excitement can become addictive.

3. Shopping to dampen unpleasant emotions. Compulsive shopping is an attempt to fill an emotional void, like loneliness, lack of control, or lack of self-esteem. Often, a negative mood, such as an argument or frustration triggers an urge to shop. However, the decrease in negative emotions is temporary and it is replaced by an increase in anxiety or guilt (Donnelly et al., 2016).

4. Guilt and remorse. Purchases are followed by feelings of remorse. They feel guilty and irresponsible for purchases that they perceive as indulges. The result may be a vicious cycle, that is, negative feeling fuel another “fix,” purchasing something else.

The result may be a vicious cycle, that is, negative feeling fuel another “fix,” purchasing something else.

5. The pain of paying. Paying with cash is more painful than paying with credit cards (Ariely and Kreisler, 2017). The main psychological force of credit cards is that they separate the pleasure of buying from the pain of paying. Credit cards seduce us into thinking about the positive aspects of a purchase. In fact, CBD is only prevalent in developed countries where there is a system of credit and a consumer culture.

How to restrain the urge to spend? The most effective first step in treatment is to identify why and how your shopping initially became a problem. A useful strategy is to keep track of your triggers (negative emotions such as family conflict, anxiety, or loneliness). And one needs to be reminded that additional material goods and services initially provide extra pleasure, but it is usually temporary. The extra pleasure wears off. It is also helpful to emphasize the importance of managing credit cards or getting rid of credit cards. It is a known fact that the use of cash tends to reduce excessive spending.

It is also helpful to emphasize the importance of managing credit cards or getting rid of credit cards. It is a known fact that the use of cash tends to reduce excessive spending.

Compulsive shopping. Change your brain

Compulsive shopping. Change your brain - change your life!WikiReading

Change your brain - change your life!

Amen Daniel

Contents

Compulsive shopping

Compulsive shopping is another manifestation of disturbances in the belt system. Compulsive shoppers get euphoric from the rush to buy. They spend an incongruous amount of time thinking about shopping and everything related to it. This dependence can undermine their financial situation, relationships with others and reflect badly on their work.

Jill

Jill worked as an office manager for a large law firm in San Francisco. Before work, during lunch breaks and after work, she was irresistibly drawn to the shops in Union Square, which was very close to her work. When Jill chose clothes for herself or members of her family, she felt joyful excitement. She liked to buy gifts even for strangers. For her, the very fact of making a purchase was important. Although she knew not to spend so much money, the pleasure of the purchase was too great for her to stop. She often quarreled with her husband because she spent too much. She began to take money at work. She had a corporate checkbook, so Jill began writing fictitious checks to non-existent suppliers to cover her debts. After her fraud was nearly discovered during an audit, she stopped. But the addiction persisted. Her husband divorced her after discovering a $30,000 debt on her credit card. Jill was ashamed, fearful and depressed, and she asked for help. All her life she was prone to unrest. She had an eating disorder as a teenager and one of her cousins had OCD. SPECT scanning revealed marked hyperfunction of the cingulate system. When Jill had obsessive thoughts about shopping or when she broke down and started spending money, it was extremely difficult for her to break out of this state.

When Jill chose clothes for herself or members of her family, she felt joyful excitement. She liked to buy gifts even for strangers. For her, the very fact of making a purchase was important. Although she knew not to spend so much money, the pleasure of the purchase was too great for her to stop. She often quarreled with her husband because she spent too much. She began to take money at work. She had a corporate checkbook, so Jill began writing fictitious checks to non-existent suppliers to cover her debts. After her fraud was nearly discovered during an audit, she stopped. But the addiction persisted. Her husband divorced her after discovering a $30,000 debt on her credit card. Jill was ashamed, fearful and depressed, and she asked for help. All her life she was prone to unrest. She had an eating disorder as a teenager and one of her cousins had OCD. SPECT scanning revealed marked hyperfunction of the cingulate system. When Jill had obsessive thoughts about shopping or when she broke down and started spending money, it was extremely difficult for her to break out of this state. Treatment helped Jill, including the drug Zoloft (an anti-manic antidepressant).

Treatment helped Jill, including the drug Zoloft (an anti-manic antidepressant).

Obsessive Compulsive Style

obsessive-compulsive style Wilhelm Reich called compulsive people "living machines." the description turns out to be quite appropriate, because it corresponds to their subjective experience. However, it is a good example of a common

1. What is shopping

1. What is shopping Shopping is called shopping. This word comes from the English shopping, which means "make purchases." This term has appeared quite recently. What is the reason for its occurrence in Russian? After all, purchases were made before. Probably, this is

2. Shopping addiction

2. Shopping addiction

Shopping addiction

Children's shopping

Children's shopping Children go shopping both with their parents and on their own. This depends on the choice of purchase. If a child is allowed to go to the store alone, they don't give him much money. Therefore, his purchases are limited to chips, sweet soda,

Teen shopping

Teen shopping Teenagers, unlike children, are more passionate about their appearance. Advertising imposes new principles on teenagers: to be significant, you need to look cool, have cool things (a new model mobile phone, fashionable shoes and clothes, stylish

Internet shopping

Internet shopping Recently, online shopping has become increasingly popular in Russia. Perhaps the reason for this is the convenience and simplification of the purchase process. In order to place an order, you do not have to go anywhere or drive. As a result, time is saved. About

In order to place an order, you do not have to go anywhere or drive. As a result, time is saved. About

Book shopping

book shopping The book industry is one of the fastest growing. The shelves of bookstores were flooded with books of various contents. Readers are promised to be taught practically everything, to be told about everything, to satisfy every taste. The number of

Mobile shopping

Mobile shopping Mobile phones are becoming more and more integral to our lives. They are no longer just a means of communication. Modern mobile phones are equipped with additional devices: clocks, radios, mp3 players, cameras and cameras, voice recorders, etc.

Shopping in a department store

Shopping in a department store Department stores differ from ordinary stores in that they display goods visually. In one building there are departments of various specializations, where all consumer needs can be met. It also sells goods for everyday needs and

In one building there are departments of various specializations, where all consumer needs can be met. It also sells goods for everyday needs and

Shopping in a supermarket

Shopping in a supermarket A supermarket is a store that sells lower quality goods as well as groceries. The presented range of goods is not very large. These are mainly cheap consumer goods. Supermarkets are focused on

Shopping Mall

shopping mall The name of the store "mall" comes from the American word mall, which is the common name for a shopping and entertainment center. The shopping mall is a new approach to the shopping process in stores. Particular emphasis in shopping malls is placed on

7. Shopping abroad

7. Shopping abroad Shopping is widespread all over the world, not only in Europe but also in Asia. Travel companies even organize special shopping tours to different countries. Buyer behavior and shopping mall policies vary from country to country, although

Travel companies even organize special shopping tours to different countries. Buyer behavior and shopping mall policies vary from country to country, although

Shopping in France

Shopping in France The capital of France has long been considered the center of world fashion. The most prestigious and expensive shops are located on the streets of Paris. In them, you can not see customers hung from head to toe with packages and bags. For most tourists, the goods offered in such

UK shopping

Shopping in the UK England is also a trendsetter in world fashion. Therefore, people who come there to see the local sights cannot help but walk through the famous English shops. The large Harodz department store is included in

Shopping in Turkey

Shopping in Turkey Turkey is the most popular place of "pilgrimage" for Russian tourists. Hundreds of thousands of Russians travel to this warm Asian country every year. It is considered a resort area. However, Turkey is famous not only for its seaside resorts, but also for

Hundreds of thousands of Russians travel to this warm Asian country every year. It is considered a resort area. However, Turkey is famous not only for its seaside resorts, but also for

2. Compulsive nature

2. Compulsive nature If the most general function of the character is protection from stimuli and maintenance of mental balance, then it should be especially easy to reveal itself in a compulsive character. After all, the compulsive nature is one of the most studied

Addition for purchases (compulsive shopping) - Psychiatrist Diary No. 02 2014

Subscribe to new numbers

Addiction to shopping (compulsive shopping) №02 2014

Author: A. Yu.Egorov

Yu.Egorov

St. Petersburg State University; Northwestern State Medical University named after N.N. I.I. Mechnikov of the Ministry of Health of Russia, St. Petersburg; Institute of Evolutionary Physiology and Biochemistry. I.M. Sechenov RAS, St. Petersburg

Page numbers in issue: 11-13

Shopping addiction (compulsive shopping) refers to non-chemical forms of addictive disorders. Non-chemical addictions are called addictions, where the object of dependence is a behavioral pattern, and not psychoactive substances (PSA).

Shopping addiction (compulsive shopping) refers to non-chemical forms of addictive disorders. Non-chemical addictions are called addictions, where the object of dependence is a behavioral pattern, and not psychoactive substances (PSA).

In Western literature, the term "behavioral or non-pharmacological addictions" is more often used to refer to these types of addictive behavior. It should be noted that the relevance of studying non-chemical forms of addictive disorders today turned out to be so high that behavioral addictions (gambling) are included in the new DSM-V classification (2013), in the section "Disorders associated with the use of psychoactive substances and addictive disorders" (Substance Use and Addictive Disorders). The issue of including other non-chemical addictions in this section was also actively discussed: sexual addiction, Internet addiction and shopping addiction.

The issue of including other non-chemical addictions in this section was also actively discussed: sexual addiction, Internet addiction and shopping addiction.

There is no unified classification of non-chemical addictions today. According to our classification, the latest version of which is shown in the table, shopping addiction belongs to the group of "socially acceptable" forms of non-chemical addictions.

Socially acceptable forms of addictive disorders are of particular interest to addictology in terms of preventive, therapeutic and rehabilitation measures for chemical addicts. At the same time, it is obvious that the social acceptability of various forms of non-chemical addictions is largely conditional and depends on a number of factors (cultural, national, social, etc.).

"Oniomaniacs", or shopping maniacs, have been the subject of research by psychiatrists since the time of E. Kraepelin, who first proposed this term in 1909. E. Bleiler classified oniomaniacs along with pyromaniacs, kleptomaniacs and alcoholics under the heading "Kraepelin's impulsive psychoses. " Descriptions of oniomania by the classics of psychiatry were based on the concept of J.E.D. Esquirol about monomania. In his “Manual of Psychiatry”, E. Bleuler describes oniomania as follows: “purchases are made impulsively and lead to ridiculous debts, while the collapse clarifies the situation for a while, but only to some extent, because patients will never admit all debts <...> we have always dealing with women. The impulsive moment is essential, that the patient cannot otherwise <...> the patients are not able to think about anything, they are not able to imagine the consequences of their ridiculous actions and decide that this can not be done.

" Descriptions of oniomania by the classics of psychiatry were based on the concept of J.E.D. Esquirol about monomania. In his “Manual of Psychiatry”, E. Bleuler describes oniomania as follows: “purchases are made impulsively and lead to ridiculous debts, while the collapse clarifies the situation for a while, but only to some extent, because patients will never admit all debts <...> we have always dealing with women. The impulsive moment is essential, that the patient cannot otherwise <...> the patients are not able to think about anything, they are not able to imagine the consequences of their ridiculous actions and decide that this can not be done.

Nevertheless, shopping addiction (compulsive shopping) has begun to attract widespread research attention in recent decades. Such an addiction could become widespread only in a mature consumer society, which is represented by modern developed countries and to which Russia is steadily moving, at least in large cities.

In a society of total scarcity, the development of addiction to shopping looks problematic as a mass phenomenon. Most researchers agree that shopping addiction is most common among the middle class. Other social factors that contribute to the development of this addiction include advertising in the media, easy access to credit in stores, paying for purchases with credit cards and on the Internet.

Most researchers agree that shopping addiction is most common among the middle class. Other social factors that contribute to the development of this addiction include advertising in the media, easy access to credit in stores, paying for purchases with credit cards and on the Internet.

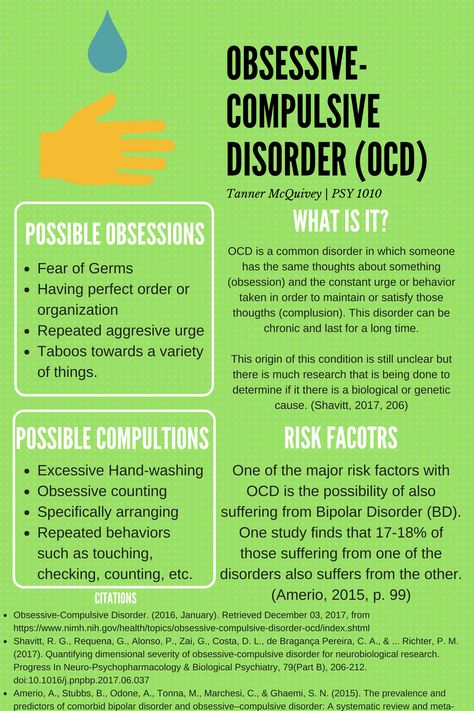

The place of shopping addiction among other mental disorders is still debated. Some authors refer compulsive shopping along with gambling, kleptomania, Tourette's syndrome, eating disorders to the obsessive-compulsive spectrum of disorders. Some researchers consider compulsive shopping behavior to be only part of a spectrum of so-called "abnormal consumer behavior" that includes pathological gambling, shoplifting, and credit card fraud. Of course, factors that contribute to a positive mood (for example, a refined aroma, beautiful colors, pleasant music) can trigger a shopping urge. However, compulsive shopping is more often formed in the context of negative emotions and, like other addictions, is a way to escape from them. Psychological factors in the development of addiction to shopping, which make up a kind of "shopping cycle", are shown in the figure.

Psychological factors in the development of addiction to shopping, which make up a kind of "shopping cycle", are shown in the figure.

Of the risk factors for the development of addiction, it has also been shown that various forms of psychotrauma in children under 12 years of age (physical neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and especially being a witness to violence and emotional abuse) correlate with the subsequent development of compulsive shopping.

Interesting data on the hereditary burden of shopping addiction were obtained by D. Black et al. 137 first-degree relatives were evaluated in 31 people with compulsive shopping. It turned out that relatives of addicts are significantly more likely than in the comparison group to have depression, alcoholism, drug addiction, "any mental disorder" and "more than one mental disorder." Shopping addiction was identified in 10% of first-degree relatives, but was not assessed in the comparison group. However, this figure is twice the population level.

The neurobiology of compulsive shopping is not well understood. One of the single studies was conducted by B. Knutson et al. using functional magnetic resonance imaging. It turned out that in a situation before making a purchase decision, the choice of a particular product activates the nucleus accumbens, and the situation of inflated prices is accompanied by activation of the isthmus and a decrease in activation of the prefrontal cortex. The activity of each of these regions depends on making purchases in excess of the expected volume. The data from this study provide evidence for common neurobiological mechanisms of compulsive shopping and other behavioral addictions.

Shopping addiction was first described in detail by P. Slater under the name "wealth addiction" almost 30 years ago. T. O'Guinn and R. Faber characterized compulsive shopping as "chronic, repetitive shopping that becomes the primary response to negative events and feelings." Although the diagnostic criteria for compulsive shopping appeared almost 30 years ago, it is still not presented as a separate mental disorder in the International Classification of Diseases.

10th revision, nor in the DSM.

R. Faber and T. O'Guinn report that this type of addiction affects 1.1% of the population, whose average age is 39 years. The addiction to spending money usually starts around the age of 30.

it affects predominantly women (92% of all addicts). R. Miltenberger et al. report that shopping addiction begins at a younger age - the average age of the women they surveyed was 17.5 years. D. Black cites data that this addiction occurs in 2–8% of the general population, of which women make up 80–95%. A. Benson said that from 1 to 10% of the US population suffer from addiction to shopping.

More recent research suggests that about 5% of the US population is addicted to shopping. L.Koran et al. telephone interviews with 2,513 American adults found the prevalence of addiction to be 5.8%. Among college students (youth), the incidence of compulsive shopping was 3.6%, with females significantly predominating over men: 4.4% versus 2.5%.

R. Faber and T. O'Guinn proposed a seven-point scale to identify this addiction. Shopping addiction was described and typified also according to the DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria for obsessive-compulsive and addictive disorders in the 1990s. The authors proposed four of its criteria, and the presence of one of them is sufficient for diagnosis:

Faber and T. O'Guinn proposed a seven-point scale to identify this addiction. Shopping addiction was described and typified also according to the DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria for obsessive-compulsive and addictive disorders in the 1990s. The authors proposed four of its criteria, and the presence of one of them is sufficient for diagnosis:

- Often there are preoccupations with shopping or sudden impulses to buy something that are felt to be overwhelming, intrusive and/or pointless.

- Regular purchases are made beyond one's means, things are often bought that are not needed, or shopping takes significantly longer than originally planned.

- Shopping preoccupations, sudden impulses to buy, or related behaviors are accompanied by marked distress, inappropriate use of time, become a serious hindrance in both daily life and professional life, or entail financial problems (for example, debt or bankruptcy).

- Excessive shopping or shopping does not necessarily occur during periods of hypomania or mania.

Addiction to shopping is manifested by repeated, irresistible desire to make many purchases. Between purchases, tension builds up, which can be relieved by the next purchase, after which guilt usually sets in. In general, a wide range of negative emotions characteristic of addicts is characteristic, positive emotions up to euphoria arise only in the process of making a purchase.

This category of addicts has growing debts, problems in relationships with the family, and there may be problems with the law. Sometimes addiction is realized through online purchases that are made not in supermarkets, but in virtual stores.

Often, shopping addiction is combined with compulsive hoaring, which is defined as the acquisition and inability to give up possessions that seem useless or have limited value. A number of researchers distinguish compulsive hoarding as an independent addiction. In Russian psychopathology, pathological hoarding was described within the framework of the “Plyushkin syndrome” and was more often considered as a manifestation of disorders of involutional and senile age. In our opinion, compulsive hoarding in young and middle age (in the absence of pronounced organic changes in the brain) is phenomenologically close to compulsive shopping and can be considered as a variant of this addiction. Often these forms can be combined. Thus, it was shown that among patients who meet the criteria for compulsive hoarding, 61% had an addiction to purchases, and 85% reported that episodes of excessive purchases are not uncommon in their lives. As for Plushkin's syndrome, it is obvious that this is not a manifestation of an addictive disorder at all, but rather deep organic (often atrophic) disorders of the brain tissue.

In our opinion, compulsive hoarding in young and middle age (in the absence of pronounced organic changes in the brain) is phenomenologically close to compulsive shopping and can be considered as a variant of this addiction. Often these forms can be combined. Thus, it was shown that among patients who meet the criteria for compulsive hoarding, 61% had an addiction to purchases, and 85% reported that episodes of excessive purchases are not uncommon in their lives. As for Plushkin's syndrome, it is obvious that this is not a manifestation of an addictive disorder at all, but rather deep organic (often atrophic) disorders of the brain tissue.

Data from clinical studies report a high comorbidity between shopping addiction and other psychiatric disorders. So, affective disorders, according to various sources, occur in 21-100% of cases, anxiety disorders - in 41-80%, chemical dependence - in 21-46% and eating disorders -

in 8–35%.

Studies in the 1990s showed that shopping addiction is often combined with anxiety disorder (50%), chemical dependence (45. 8%), including alcoholism (20%) and food addictions (20.8%), depression (eighteen%). A specially conducted study showed that eating disorders (anorexia and bulimia) are often observed in shopping addiction. In turn, people with eating disorders often have an addiction to shopping. It has been suggested that addiction to spending money may be included in the familial and possibly genetic "clinical spectrum" of disorders, which includes addictive and affective disorders. Confirmation can be the data that, in turn, 38 out of 119(31.9%) of patients with depression reported episodes of uncontrolled spending of money to make purchases, and all of these patients were women. In addition, spending addicts have a significantly higher risk of recurrent depression, kleptomania, bulimia, and chemical dependencies: benzodiazepine abuse.

8%), including alcoholism (20%) and food addictions (20.8%), depression (eighteen%). A specially conducted study showed that eating disorders (anorexia and bulimia) are often observed in shopping addiction. In turn, people with eating disorders often have an addiction to shopping. It has been suggested that addiction to spending money may be included in the familial and possibly genetic "clinical spectrum" of disorders, which includes addictive and affective disorders. Confirmation can be the data that, in turn, 38 out of 119(31.9%) of patients with depression reported episodes of uncontrolled spending of money to make purchases, and all of these patients were women. In addition, spending addicts have a significantly higher risk of recurrent depression, kleptomania, bulimia, and chemical dependencies: benzodiazepine abuse.

Having studied the comorbid pathology of 20 compulsive buyers who met the criteria for addiction to shopping, S. McElroy et al. found that 19 (95%) of them had a lifetime diagnosis of an affective disorder, 16 (80%) of an anxiety disorder, 8 (40%) of a disorder of habits and drives,

7 (35%) - eating disorders. Their immediate family members often had affective disorders. The authors also note that 9 (69%) of 13 patients treated with thymoleptics experienced a reduction in frequency or complete remission in relation to episodes associated with uncontrolled purchases. A more recent study reports the following psychiatric comorbidities in 22 shopping addicts: 64% social phobia, 45% major depression, 41% obsessive-compulsive disorder, 32% post-traumatic stress disorder, 32% generalized anxiety disorder, 32 % eating disorders, 27% specific phobias, 27% panic disorder and 23% substance abuse.

Their immediate family members often had affective disorders. The authors also note that 9 (69%) of 13 patients treated with thymoleptics experienced a reduction in frequency or complete remission in relation to episodes associated with uncontrolled purchases. A more recent study reports the following psychiatric comorbidities in 22 shopping addicts: 64% social phobia, 45% major depression, 41% obsessive-compulsive disorder, 32% post-traumatic stress disorder, 32% generalized anxiety disorder, 32 % eating disorders, 27% specific phobias, 27% panic disorder and 23% substance abuse.

According to a German study, women with compulsive shopping had significantly higher rates of affective, anxiety, and eating disorders compared to controls.

This group had high scores for different forms of personality disorders (avoidant, depressive, obsessive-compulsive and borderline personality disorders), along with high rates of impulse control disorders. Other authors have also pointed out the connection between borderline personality disorder and shopping addiction./s3/static.nrc.nl/images/stripped/0608nntvcleaners.jpg)

After analyzing 46 cases, S. Schlosser et al. described an average portrait of a shopping addict in the early 1990s: a 31-year-old woman whose disorder began at age 18. The most common purchases are clothes, shoes, records/CDs. The average debt is 5422 dollars. USA, average annual income - 23 443 dollars. USA. She was more than 66% likely to have had a psychiatric diagnosis during her lifetime, most commonly an anxiety disorder, substance abuse, or mood disorder. She has about a 60% chance of meeting the DSM-III-R criteria for a "personality disorder" (obsessive-compulsive, borderline, or avoidant types).

Addiction to shopping is often accompanied by negative consequences. So, G. Christenson et al. [13] draw attention to the fact that this disorder leads to the accumulation of large debts (58.3%), inability to repay debts (41.7%), negative reactions from others (33.3%), legal and financial consequences (8, 3%), criminal problems with the law (8.3%), feelings of guilt (45. 8%).

8%).

Therapy

Attempts are being made to treat addiction to shopping with the help of psychotropic drugs. C. McElroy reports that the antidepressants fluoxetine, bupropion, and nortriptyline may be useful in the treatment of this addiction. D. Black et al. used fluvoxamine and reported improvement in 9out of 10 treated addicts. However, in

Two placebo-controlled studies found similar effects with fluvoxamine and placebo in shopper addicts. A pilot study of citalopram showed that this selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor was effective in reducing compulsive shopping. In a recent open-label, double-blind study of a new form of citalopram, escitalopram at a dose of 20 mg / day, the effectiveness of the treatment of compulsive shopping was shown.

It should be noted that the success of therapy in relation to addiction to shopping could also be of a secondary nature, since antidepressants have proven effectiveness in relation to affective and obsessive-compulsive symptoms, which almost always accompanies them. For other drugs, there is evidence that in an open-label 10-week study of memantine (dose 10 to 30 mg/day) for the treatment of shopping addiction, out of 9 participants, 8 (88.9%) completed it. According to the Yale-Brown scale for compulsive shopping, there was a significant decrease in indicators. The average effective dose of memantine was 23.4±8.1 mg/day. The effect of memantine has been associated with a reduction in shopping, spending money, and improved performance on cognitive tasks associated with impulsivity. In addition, the drug was well tolerated. Preliminary results have been obtained on the successful use of the opioid antagonist naltrexone in patients with shopping addiction.

For other drugs, there is evidence that in an open-label 10-week study of memantine (dose 10 to 30 mg/day) for the treatment of shopping addiction, out of 9 participants, 8 (88.9%) completed it. According to the Yale-Brown scale for compulsive shopping, there was a significant decrease in indicators. The average effective dose of memantine was 23.4±8.1 mg/day. The effect of memantine has been associated with a reduction in shopping, spending money, and improved performance on cognitive tasks associated with impulsivity. In addition, the drug was well tolerated. Preliminary results have been obtained on the successful use of the opioid antagonist naltrexone in patients with shopping addiction.

There are reports of the effectiveness of the Debtors Anonymous program, based on the 12-step program for Alcoholics Anonymous. J. Mitchell et al. recently published a report on the successful use of group cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for the correction of addiction to shopping, which was carried out for 10 weeks in 28 patients. A study of 6-month follow-ups showed that the positive effect of therapy is quite long-term.

A study of 6-month follow-ups showed that the positive effect of therapy is quite long-term.

A. Muller et al. conducted a randomized study of the comparative effectiveness of group cognitive-behavioral therapy on 31 patients. Treatment was specifically aimed at stopping compulsive shopping and controlling problem behaviors, creating a healthy buying pattern, restructuring inappropriate thoughts and negative feelings associated with shopping, and acquiring and developing healthy habits. Improvement after treatment was maintained during the 6-month follow-up. A smaller effect was observed in individuals who attended group classes less often.

Single data (2 clinical cases) were obtained on the effective combination of cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy with fluvoxamine in the treatment of people with compulsive shopping. The same group of researchers reported the successful use of fluvoxamine in combination with psychodynamic psychotherapy in patients with a comorbidity of shopping addiction and bulimia.