Myths on mental illness

Mental Health Myths and Facts

Can you tell the difference between a mental health myth and fact? Learn the truth about the most common mental health myths.

Mental Health Problems Affect Everyone

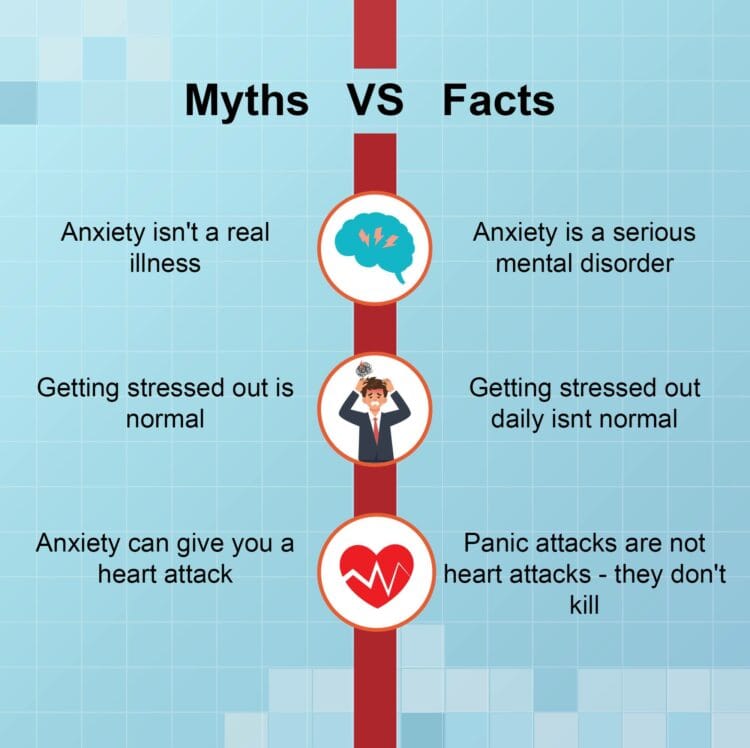

Myth: Mental health problems don't affect me.

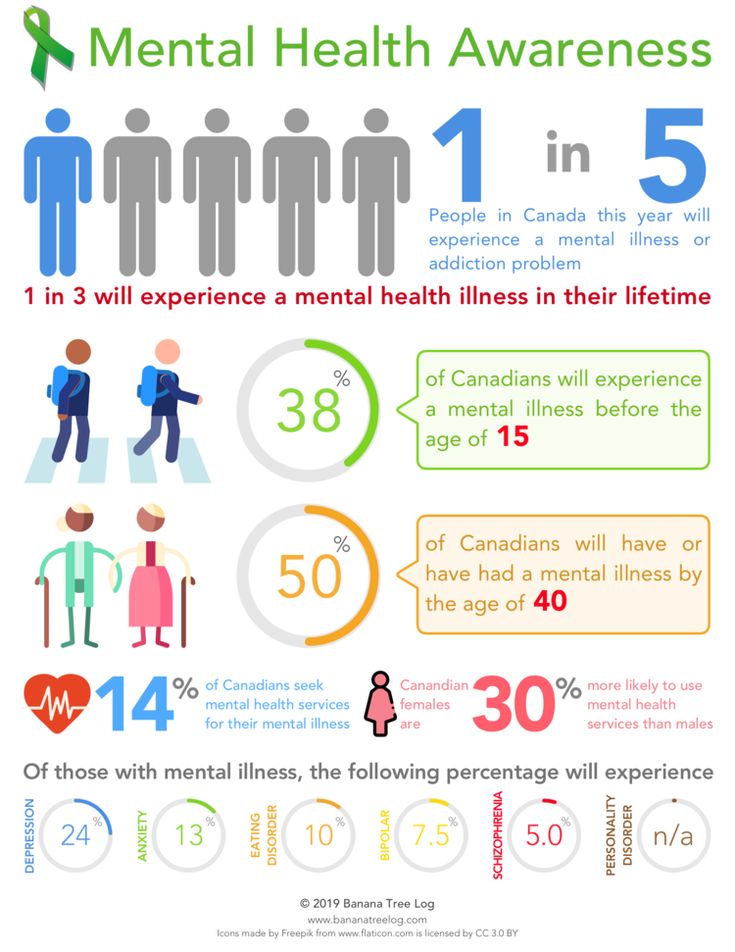

Fact: Mental health problems are actually very common. In 2020, about:

- One in five American adults experienced a mental health issue

- One in 6 young people experienced a major depressive episode

- One in 20 Americans lived with a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression

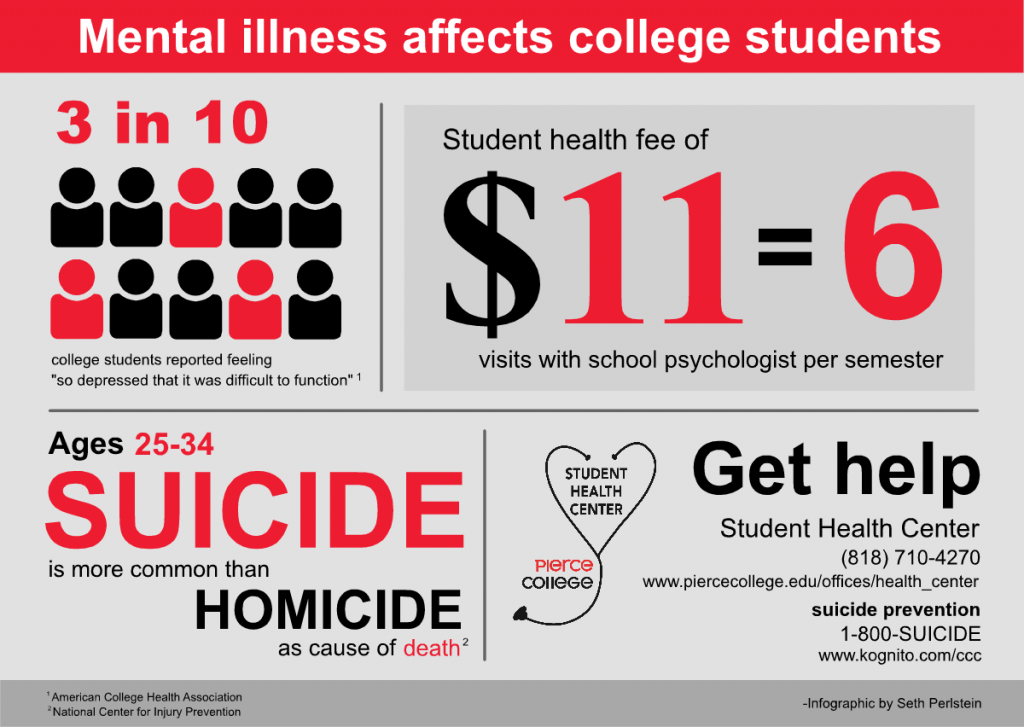

Suicide is a leading cause of death in the United States. In fact, it was the 2nd leading cause of death for people ages 10-24. It accounted for the loss of more than 45,979 American lives in 2020, nearly double the number of lives lost to homicide. Learn more about mental health problems.

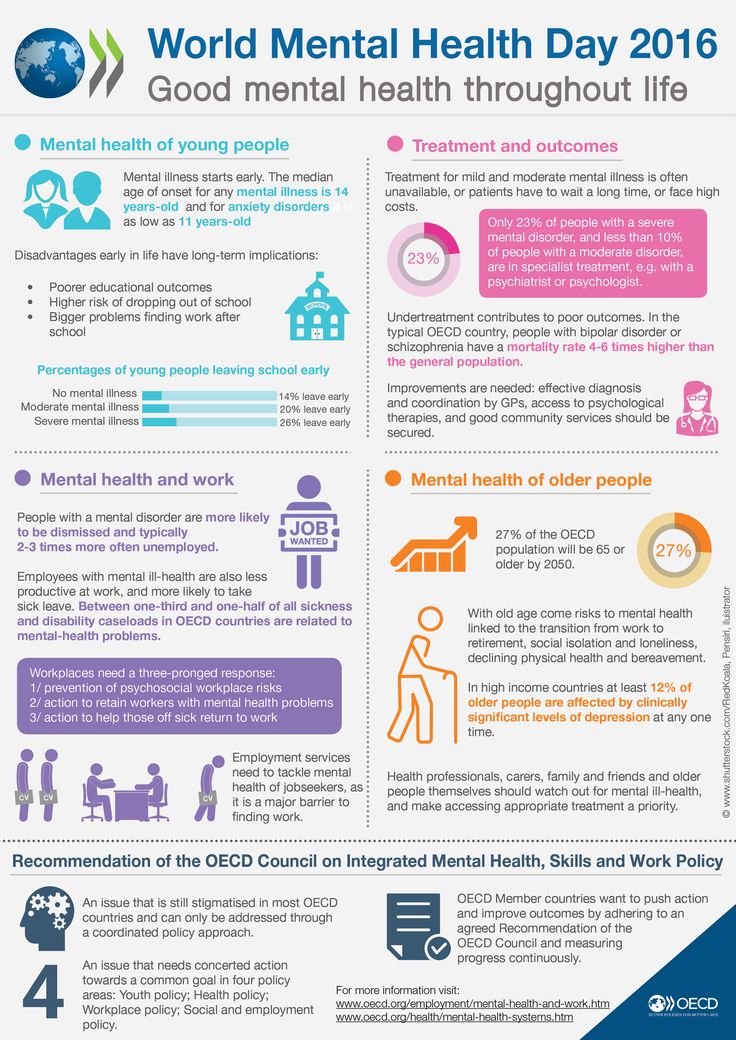

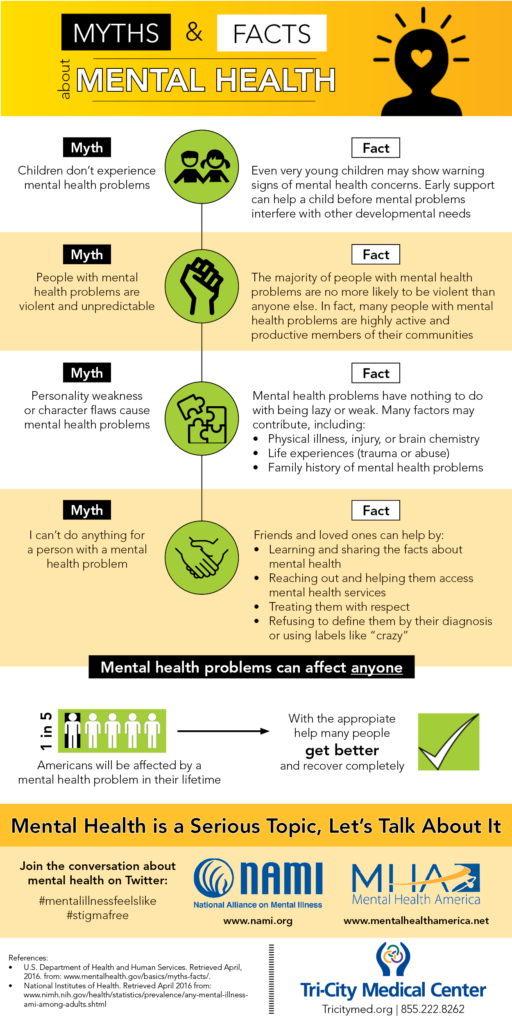

Myth: Children don't experience mental health problems.

Fact: Even very young children may show early warning signs of mental health concerns. These mental health problems are often clinically diagnosable, and can be a product of the interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors.

Half of all mental health disorders show first signs before a person turns 14 years old, and three-quarters of mental health disorders begin before age 24.

Unfortunately, only half of children and adolescents with diagnosable mental health problems receive the treatment they need. Early mental health support can help a child before problems interfere with other developmental needs.

Myth: People with mental health problems are violent and unpredictable.

Fact: The vast majority of people with mental health problems are no more likely to be violent than anyone else. Most people with mental illness are not violent and only 3%–5% of violent acts can be attributed to individuals living with a serious mental illness. In fact, people with severe mental illnesses are over 10 times more likely to be victims of violent crime than the general population. You probably know someone with a mental health problem and don't even realize it, because many people with mental health problems are highly active and productive members of our communities.

In fact, people with severe mental illnesses are over 10 times more likely to be victims of violent crime than the general population. You probably know someone with a mental health problem and don't even realize it, because many people with mental health problems are highly active and productive members of our communities.

Myth: People with mental health needs, even those who are managing their mental illness, cannot tolerate the stress of holding down a job.

Fact: People with mental health problems are just as productive as other employees. Employers who hire people with mental health problems report good attendance and punctuality as well as motivation, good work, and job tenure on par with or greater than other employees.

When employees with mental health problems receive effective treatment, it can result in:

- Lower total medical costs

- Increased productivity

- Lower absenteeism

- Decreased disability costs

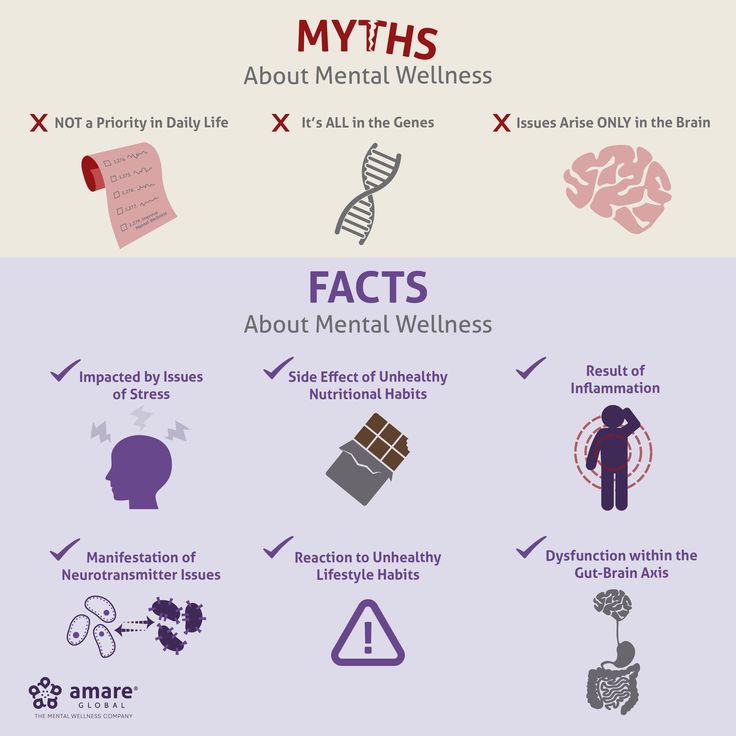

Myth: Personality weakness or character flaws cause mental health problems.

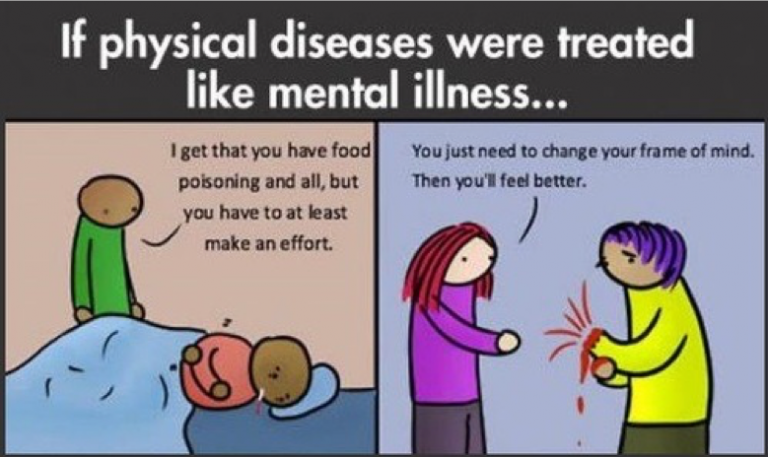

People with mental health problems can snap out of it if they try hard enough.

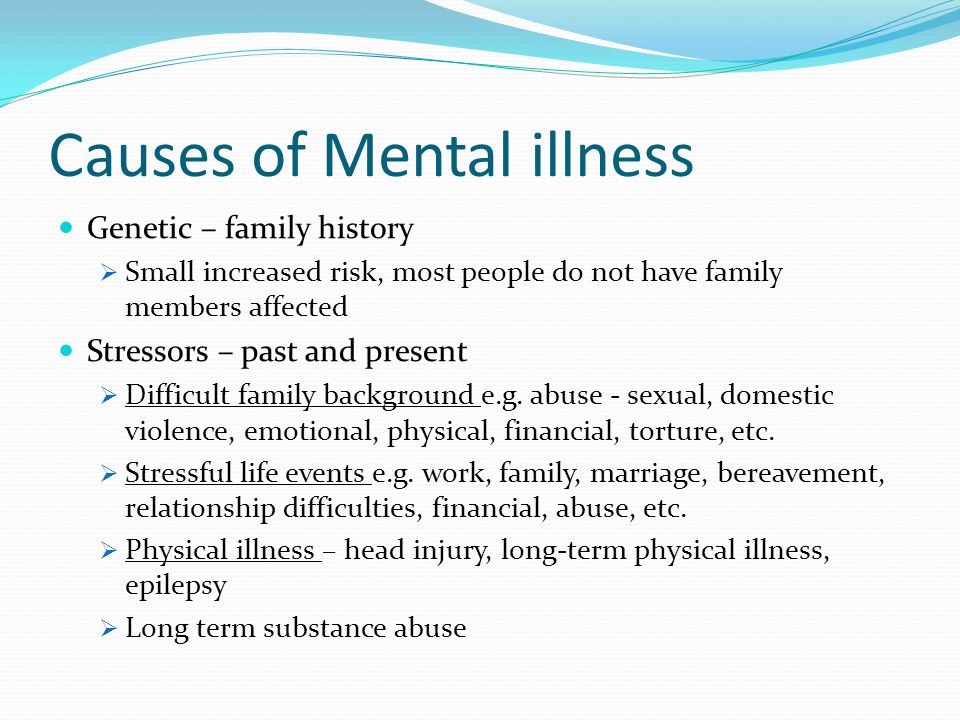

People with mental health problems can snap out of it if they try hard enough.Fact: Mental health problems have nothing to do with being lazy or weak and many people need help to get better. Many factors contribute to mental health problems, including:

- Biological factors, such as genes, physical illness, injury, or brain chemistry

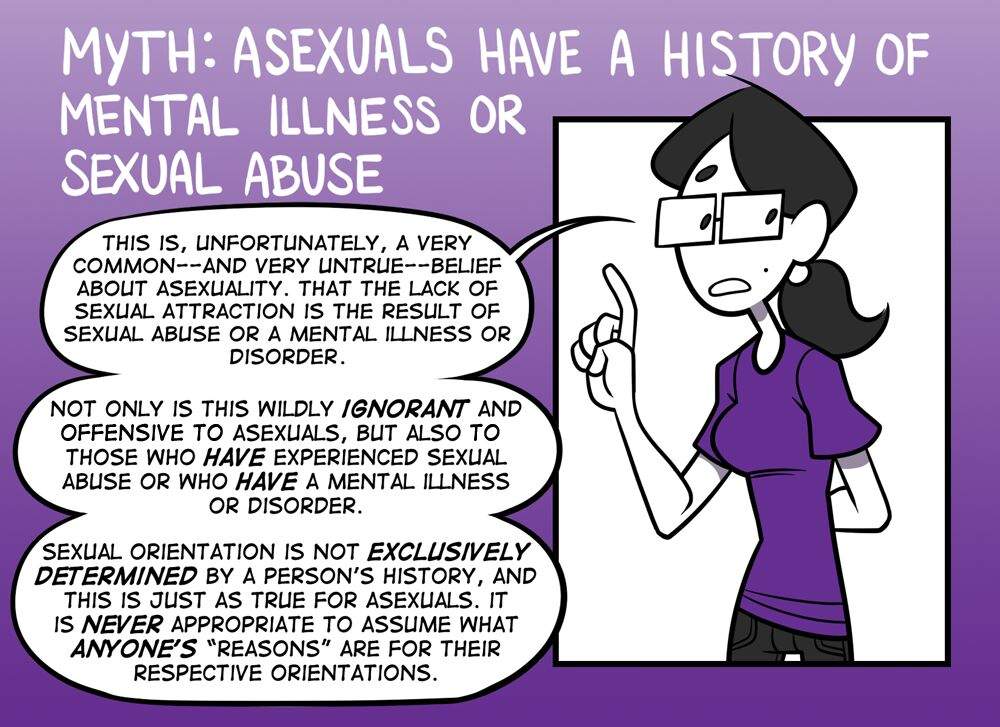

- Life experiences, such as trauma or a history of abuse

- Family history of mental health problems

People with mental health problems can get better and many recover completely.

Helping Individuals with Mental Health Problems

Myth: There is no hope for people with mental health problems. Once a friend or family member develops mental health problems, he or she will never recover.

Fact: Studies show that people with mental health problems get better and many recover completely. Recovery refers to the process in which people are able to live, work, learn, and participate fully in their communities. There are more treatments, services, and community support systems than ever before, and they work.

There are more treatments, services, and community support systems than ever before, and they work.

Myth: Therapy and self-help are a waste of time. Why bother when you can just take a pill?

Fact: Treatment for mental health problems varies depending on the individual and could include medication, therapy, or both. Many individuals work with a support system during the healing and recovery process.

Myth: I can't do anything for a person with a mental health problem.

Fact: Friends and loved ones can make a big difference. In 2020, only 20% of adults received any mental health treatment in the past year, which included 10% who received counseling or therapy from a professional. Friends and family can be important influences to help someone get the treatment and services they need by:

- Reaching out and letting them know you are available to help

- Helping them access mental health services

- Learning and sharing the facts about mental health, especially if you hear something that isn't true

- Treating them with respect, just as you would anyone else

- Refusing to define them by their diagnosis or using labels such as "crazy", instead use person-first language

Myth: Prevention doesn't work.

It is impossible to prevent mental illnesses.

It is impossible to prevent mental illnesses.Fact: Prevention of mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders focuses on addressing known risk factors such as exposure to trauma that can affect the chances that children, youth, and young adults will develop mental health problems. Promoting the social-emotional well-being of children and youth leads to:

- Higher overall productivity

- Better educational outcomes

- Lower crime rates

- Stronger economies

- Lower health care costs

- Improved quality of life

- Increased lifespan

- Improved family life

Last Updated: 02/28/2022

Busted: 7 myths about mental health

Dispelling myths about mental health can help break the stigma and create a culture that encourages people of any age to seek support when they need it. Here are seven common misconceptions about mental health:

1. Myth: If a person has a mental health condition, it means the person has low intelligence.

Fact: Mental illness, like physical illness, can affect anyone regardless of intelligence, social class, or income level.

2. Myth: You only need to take care of your mental health if you have a mental health condition.

Fact: Everyone can benefit from taking active steps to promote their well-being and improve their mental health. Similarly, everyone can take active steps and engage in healthy habits to optimize their physical health.

3. Myth: Poor mental health is not a big issue for teenagers. They just have mood swings caused by hormonal fluctuations and act out due to a desire for attention.

Fact: Teenagers often have mood swings, but that does not mean that adolescents may not also struggle with their mental health. Fourteen per cent of the world’s adolescents experience mental-health problems. Globally, among those aged 10–15, suicide is the fifth most prevalent cause of death, and for adolescents aged 15–19 it is the fourth most common cause. Half of all mental health conditions start by the age of 14.

Half of all mental health conditions start by the age of 14.

4. Myth: Nothing can be done to protect people from developing mental health conditions.

Fact: Many factors can protect people from developing mental health conditions, including strengthening social and emotional skills, seeking help and support early on, developing supportive, loving, warm family relationships, and having a positive school environment and healthy sleep patterns.

The ability to overcome adversity relies on a combination of protective factors, and neither environmental nor individual stressors alone will necessarily result in mental health problems. Children and adolescents who do well in the face of adversity typically have biological resistance as well as strong, supportive relationships with family, friends and adults around them, resulting in a combination of protective factors to support well-being.

5. Myth: A mental health condition is a sign of weakness; if the person were stronger, they would not have this condition.

Fact: A mental health condition has nothing to do with being weak or lacking willpower. It is not a condition people choose to have or not have. In fact, recognizing the need to accept help for a mental health condition requires great strength and courage. Anyone can develop a mental health condition.

6. Myth: Adolescents who get good grades and have a lot of friends will not have mental health conditions because they have nothing to be depressed about.

Fact: Depression is a common mental health condition resulting from a complex interaction of social, psychological, and biological factors. Depression can affect anyone regardless of their socioeconomic status or how good their life appears at face value. Young people doing well in school may feel pressure to succeed, which can cause anxiety, or they may have challenges at home. They may also experience depression or anxiety for no reason that can be easily identified.

7. Myth: Bad parenting causes mental conditions in adolescents.

Fact: Many factors – including poverty, unemployment, and exposure to violence, migration, and other adverse circumstances and events – may influence the well-being and mental health of adolescents, their caregivers and the relationship between them. Adolescents from loving, supporting homes can experience mental health difficulties, as can adolescent from homes where there may be caregivers who need support to maintain an optimum environment for healthy adolescent development. With support, caregivers can play an essential role in helping adolescents to overcome any problems they experience.

Harmful myths about mental illness: rare, untreated, dangerous, guilty

Mental illness is surrounded by a huge number of myths that in the public mind make a person with such a disorder not just unusual, but not quite “one of us” and so they seem to legitimize a condescending attitude, and even a refusal to communicate, a demand for isolation, and even bullying.

Myth 1.

“Mental illnesses are rare”

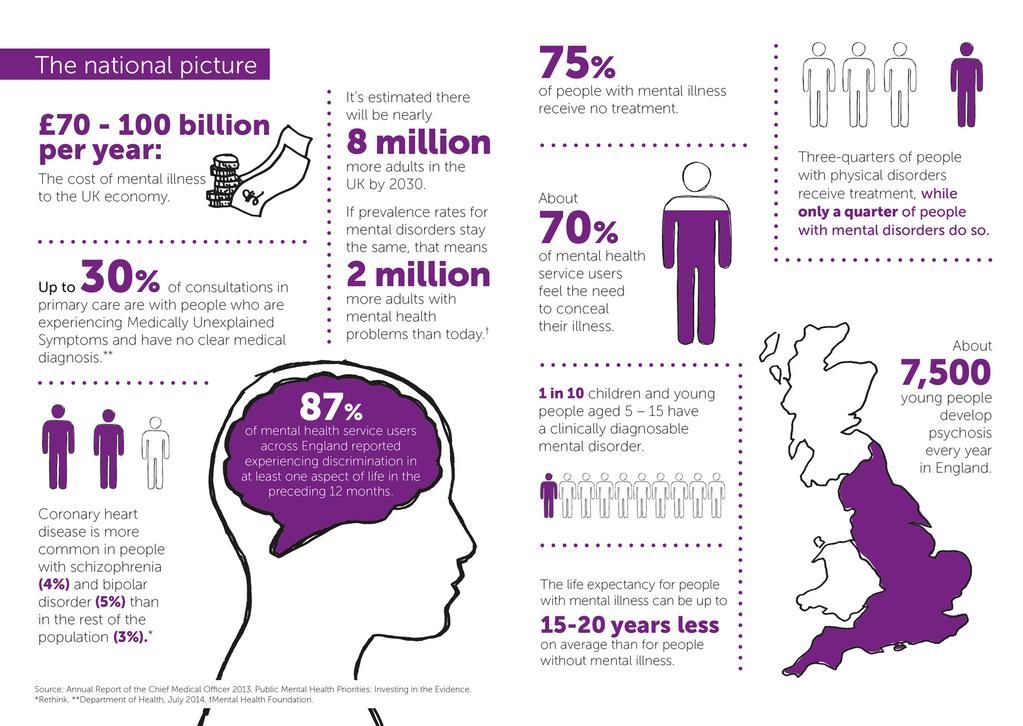

“Mental illnesses are rare” According to the World Health Organization, about 450 million people on our planet live permanently with mental disorders. At the same time, every fourth inhabitant of the Earth experiences at least one episode of mental illness (depression, anxiety disorder, post-traumatic syndrome, panic attacks) during his life.

Depression is one of the most common disorders affecting about 264 million people worldwide, and a recent US study found that the number of adults with depression has tripled during the coronavirus pandemic.

In general, mental disorders, according to WHO, are one of the leading groups of diseases worldwide.

This means that even if we forget for a moment about considerations of ethics and humanity and approach the issue exclusively from a formal point of view, a person with a mental illness is undoubtedly one of us.

Myth 2. “A mentally ill person is dangerous to others”

This is perhaps the most harmful myth that leads to the stigmatization of people with mental disorders. The reason that it is very stable, to some extent, lies in the fact that the public consciousness is strongly influenced by individual cases of crimes committed by people with mental disabilities, as well as famous works of art on this subject, for example, the film by acclaimed director Stanley Kubrick's The Shining starring the legendary Jack Nicholson.

The reason that it is very stable, to some extent, lies in the fact that the public consciousness is strongly influenced by individual cases of crimes committed by people with mental disabilities, as well as famous works of art on this subject, for example, the film by acclaimed director Stanley Kubrick's The Shining starring the legendary Jack Nicholson.

Aggressively obedient object: how we imagine mentally disabled people

It is impossible to deny the fact that individual patients with certain diagnoses fall into a violent state, and sometimes this happens unpredictably. In this state, a person can be really dangerous for himself and for others. However, among the mentally ill, such an absolute minority, and for a significant number of them, modern medicine is able to help overcome such episodes or reduce them to a minimum.

Statistical studies show two things: firstly, mentally ill people are much more likely to be victims of violent crime than their perpetrators, and secondly, the proportion of crimes committed by people with mental disabilities roughly corresponds to their share in the population.

According to Canadian psychiatrists Marie Ruwe and Randon Welton, authors of an article in the journal Psychiatry, violence attracts media attention, and a violent crime committed by a person with a mental disorder becomes a sensation that only the most morally stalwart journalist or editor will refuse.

All this, however, only reinforces the stigmatization that innocent patients already suffer from.

In conclusion, the authors of the review write: “People with mental illnesses who receive adequate medical care do not pose a greater danger to others than the general population. …

The total impact of mental illness as a factor that plays a role in the violence that occurs in society is greatly exaggerated.”

As Sir Graham Thornycroft, professor of psychiatry at King's College London, points out, there is a group of mental patients more prone to violence than others. As a rule, these are patients with a triple diagnosis, when one person suffers from three disorders at once, for example, one of the severe mental illnesses (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder), plus drug addiction, plus antisocial personality disorder.

Such combinations are quite rare, and it is extremely unfair to extend the characteristic "prone to violence" to all people with mental illness.

Myth 3. “We are to blame”

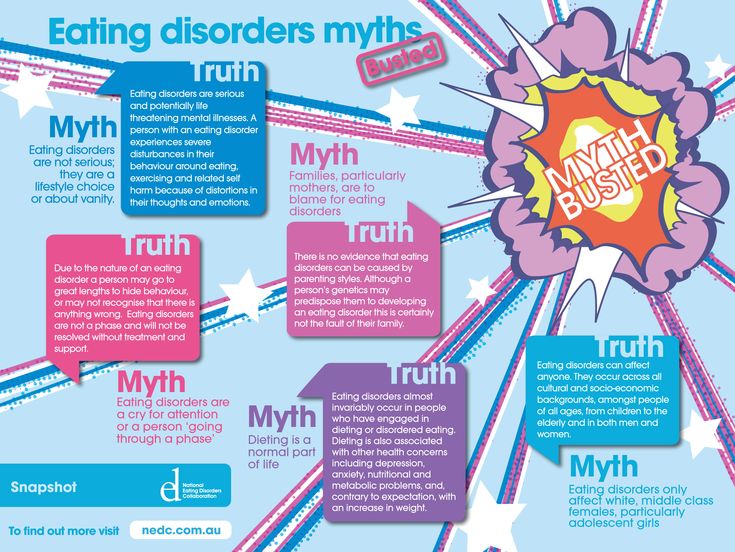

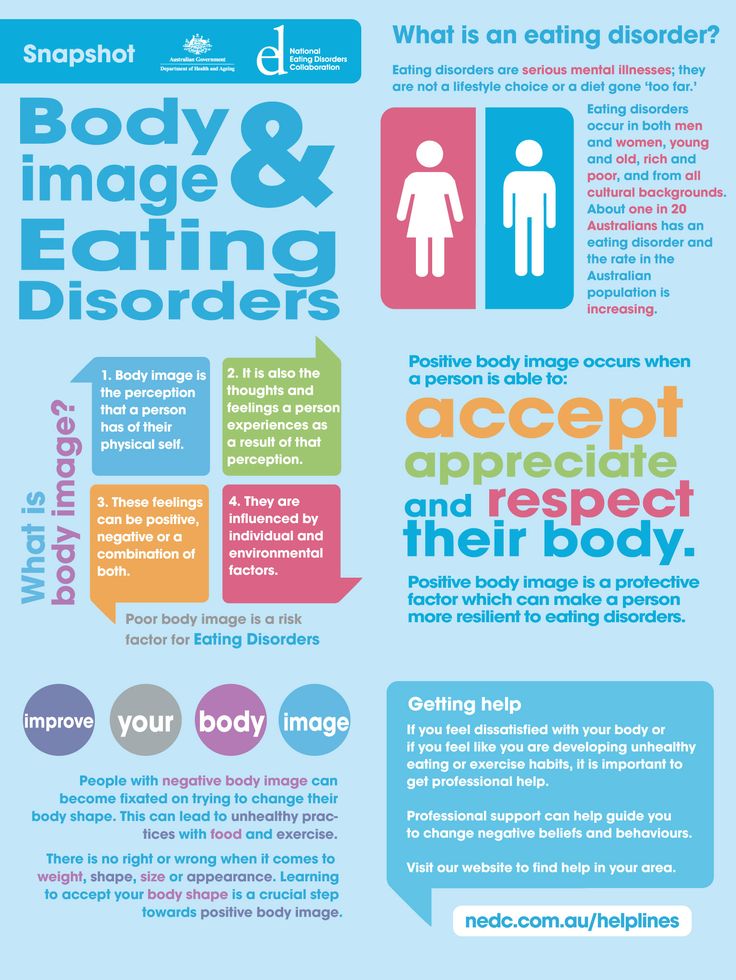

This statement can often be heard about people suffering from depression, addictions, or eating disorders.

From the outside, it seems that a person simply shows weakness, does not consider it necessary to pull himself together, or makes a conscious choice in favor of behavior that brings a lot of trouble to himself and others.

In fact, getting out of depression or alcohol/drug addiction is no easier than recovering from, for example, stomach ulcers.

The patient needs not only the support of loved ones, but also qualified medical care.

In one of the studies with the characteristic title "Strong-willed but not successful: The importance of strategies in recovery from addiction", an international group of scientists analyzed how the willpower of the patient correlates with and chances of getting rid of addiction.

The researchers concluded that there is no direct dependence, and often people suffering from any type of addiction have quite normal willpower, but their recovery depended much more on whether they found suitable strategies for controlling external factors contributing to the continuation of their addiction.

Perhaps even more unfair is the rumor about people suffering from eating disorders, especially women. You can often hear that girls are prone to anorexia or bulimia because of the desire to have a beautiful figure.

This is not true.

Firstly, men also suffer from these disorders, and secondly, eating disorders are a very serious mental illness, which in some cases leads to the death of the patient.

If a girl is afraid to eat a donut, this is a warning sign. If you really want to help, try to convince your loved one to get specialist advice, and ideally get treatment.

Myth 4. “People with mental disabilities cannot work”

In a sense, this myth contradicts the previous one. At the same time, both are quite tenacious, although the general public is becoming aware of more and more about the employment, successes and even achievements of people with mental problems.

At the same time, both are quite tenacious, although the general public is becoming aware of more and more about the employment, successes and even achievements of people with mental problems.

Of course, there are those among them whose illness is very severe and makes it impossible to live a normal life with a regular working day and a significant daily workload. But it also happens to those who suffer from serious physical ailments.

However, most people with mental illness can be as productive as anyone else. A 2014 American study analyzed employment data for people with psychiatric diagnoses. They were compared with the general indicators of employment in the population.

It turned out that the employment of people without mental illness was 75.9%, of people with relatively mild mental disorders - 68.8%, with moderate illnesses - 62.7%. And even 54.5% of people with severe mental illness worked.

In addition, scientists have found that the difference in the level of employment of people with and without mental diagnoses in the group of 18-25 years old was only 1%, and at the age of 50-64 - 21%.

Perhaps this reflects the fact that in today's world, young people with these kinds of problems receive much more assistance in terms of training and employment than those for whom it was relevant 30-40 years ago.

Myth 5. “Schizophrenia means that a person has a split personality”

Actually, a separate article could be dedicated to the myths about schizophrenia, since it is this disease that seems mysterious and even mystical, which means it causes increased interest and fear, both of which are very conducive to myth-making.

In fact, there are a number of subtypes of schizophrenia, and not all of them are associated with split consciousness, voices in the head and hallucinations.

Schizophrenia, indeed, is characterized by certain distortions in the perception of reality, oneself, as well as in emotional reactions, thinking and behavior, but the degree of their severity can be very different.

People diagnosed with schizophrenia may experience mood swings and behavioral patterns, but in a large number of cases the patient is helped by modern therapies.

There are, of course, severe forms, when a person becomes maladaptive for months, however, even with such a course of the disease, there are periods of remission in which he can lead a relatively normal life.

As for split consciousness, this is a symptom of multiple personality disorder, which is extremely rare and is not schizophrenia.

Myth 6. “Mental illness is incurable.”

This is a very harmful misconception.

Firstly, some patients are cured with the help of various drugs and psychotherapy. At the same time, a cure is understood as such a decrease in the manifestations of the disease, which allows a person to lead a full-fledged lifestyle.

Secondly, the treatment may not lead to a complete cure of the disease, but give the patient long enough periods of remission, when the symptoms are under control and the person can enjoy life.

The process of recovery from a mental illness is almost never simple and short. It is difficult to go through it alone without the acceptance and support of loved ones, as well as the professional help of doctors. But following this path, a person, as a rule, sees positive changes and is inspired by them.

It is difficult to go through it alone without the acceptance and support of loved ones, as well as the professional help of doctors. But following this path, a person, as a rule, sees positive changes and is inspired by them.

Advances in medicine and biotechnology, greater openness and public concern for people with mental illness can fundamentally change the situation in which a serious diagnosis has become a life sentence.

Source :

Medical myths: Mental health misconceptions Fifty years ago, I noticed that at the heart of modern psychiatry, as before, there is a conceptual error - a systematic misinterpretation of unwanted behavior as a diagnosis of mental illness, implying that it is due to a neurological disease, that its pharmacological treatment can be offered. Instead, I proposed that the "psychiatric patient" be viewed as an active participant in life's dramas, and not as a passive victim of pathophysiological processes over which he cannot control. In this article, I will briefly review the recent history of culturally validated medicalization of (undesirable) behavior and its social implications.

In this article, I will briefly review the recent history of culturally validated medicalization of (undesirable) behavior and its social implications.

In my essay, The Myth of Mental Illness, published in 1960, and in a book of the same title published a year later, I explicitly stated my goal: to challenge the medical character of the concept of mental illness and to reject the moral legitimacy of the involuntary psychiatric interventions it justified [1, 2]. I proposed to consider the phenomena that were then called "psychoses" and "neuroses" and now called "mental illness" as behavior that disturbs or embarrasses others or oneself, to reject the idea of patients as helpless victims of pathobiological processes they cannot control, to reject the practice of corrective psychiatry as an unacceptable foundational ideal of a free society.

Fifty Years of Change in Mental Health in the USA

In the 1950s, when I wrote The Myth of Mental Illness, , the idea that it was the responsibility of the federal government to ensure the health of Americans was not yet realized at the national level. Most of the people who were called "psychiatric patients", considered incurable, were hidden away in state psychiatric hospitals. The doctors who assisted them were hired by the state. Other doctors working in the private sector voluntarily treated their patients and were paid for by clients or their families.

Most of the people who were called "psychiatric patients", considered incurable, were hidden away in state psychiatric hospitals. The doctors who assisted them were hired by the state. Other doctors working in the private sector voluntarily treated their patients and were paid for by clients or their families.

From that time on, the clear distinctions between somatic and psychiatric hospitals, voluntary and involuntary treatment of patients, private and public psychiatry began to blur to the point of their absence. Now almost all mental health care is the responsibility of the government, it is regulated and paid for by public funds. Few or none of the psychiatrists live off the funds collected directly from the patients themselves, and no one is free to enter into a contract with his patients about the duration of the therapeutic relationship. Every mental health professional has a legal responsibility to prevent "the patient from endangering himself and others" [3]. In other words, psychiatry has been medicalized and politicized. The opinion of official American psychiatry, embodied in the official documents of the American Psychiatric Association and disseminated through diagnostic and statistical manuals, has the sanction of federal and state authorities. There are no legally valid approaches to mental illness, just as there are none for measles or melanoma.

The opinion of official American psychiatry, embodied in the official documents of the American Psychiatric Association and disseminated through diagnostic and statistical manuals, has the sanction of federal and state authorities. There are no legally valid approaches to mental illness, just as there are none for measles or melanoma.

Is mental illness a medical or legal concept?

Fifty years ago, it made sense to say that mental illness is not a disease. It makes sense to do this today. In the debate about what counts as a mental illness, medical criteria have been replaced by politico-legal and economic ones: for example, old diseases like homosexuality have disappeared, but new ones have appeared, in particular attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Fifty years ago, the question "What is mental illness?" interested doctors, philosophers, sociologists and laymen. But now this is no longer the case. The final decision on this issue belongs to the political authorities: they proclaim at the legislative level that mental illnesses are the same diseases as all others. In 1999, US President Bill Clinton stated: “Mental illnesses can be accurately diagnosed and successfully treated, just like physical illnesses” [4]. Surgeon General David Satcher agreed: “Similarly, when things go wrong with the heart, kidneys or liver, the same happens with the brain” [5]. Thus, political power and professional interests united, turning the delusion into a "false fact" [6].

In 1999, US President Bill Clinton stated: “Mental illnesses can be accurately diagnosed and successfully treated, just like physical illnesses” [4]. Surgeon General David Satcher agreed: “Similarly, when things go wrong with the heart, kidneys or liver, the same happens with the brain” [5]. Thus, political power and professional interests united, turning the delusion into a "false fact" [6].

The claim that mental illness is a diagnosable disease of the brain does not rely on scientific research, it is a fallacy, or fiction, or a naive revival of the somatic assumption of the long-discredited humoral theory of disease. My claim that mental illnesses are fictional illnesses also does not rely on scientific research, but rather is an extension of the scientific materialistic definition of pathology as structural or functional changes in cells, tissues and organs. If we accept this definition, then it follows that mental illness is a metaphor, a declaration of such a view is a statement of analytic truth and not a subject of empirical falsification.

The "Myth of Mental Illness" has offended many psychiatrists, as well as many patients. My act, if that is what it is, was to draw public attention to the linguistic pretensions of psychiatry and its preemptive rhetoric. Who can object to "helping suffering patients" or "giving the patient life-saving help"? Discarding this jargon, I insisted that psychiatric hospitals are like prisons, not hospitals, that involuntary psychiatric hospitalization is a form of confinement and not medical care, and that the correctional function of psychiatrists as judges and prison guards is not medicine and treatment. I pointed out that we would discard the traditional psychiatric perspective and instead interpret mental illness and psychiatric responses to it as a matter of morality, law, and rhetoric rather than medicine, treatment, or science.

Mental illness as a metaphor

The suggestion that mental illness should not be considered a medical problem runs counter to public opinion and psychiatric dogma. When a person hears from me that he does not have a mental illness, he most likely answers me: “As far as I know, mental illnesses are diseases of the brain, they are diagnosed in the same way as cancer. In time, thanks to advances in medical technology, psychiatrists will be able to demonstrate that mental illness is a disease of the body.” This possible future does not invalidate my argument that mental illness is a metaphor. It proves it. A doctor who comes to the conclusion that a person diagnosed with a mental illness has a brain disease indicates that he has been misdiagnosed: he does not have a mental illness, he has an unrecognized disease of the body. A doctor's misdiagnosis is not proof that mental illness belongs to a class of brain disorders.

When a person hears from me that he does not have a mental illness, he most likely answers me: “As far as I know, mental illnesses are diseases of the brain, they are diagnosed in the same way as cancer. In time, thanks to advances in medical technology, psychiatrists will be able to demonstrate that mental illness is a disease of the body.” This possible future does not invalidate my argument that mental illness is a metaphor. It proves it. A doctor who comes to the conclusion that a person diagnosed with a mental illness has a brain disease indicates that he has been misdiagnosed: he does not have a mental illness, he has an unrecognized disease of the body. A doctor's misdiagnosis is not proof that mental illness belongs to a class of brain disorders.

Such a process of biological discovery has taken place in the history of medicine, some forms of "madness" have been identified as manifestations of other somatic diseases, such as beriberi or neurosyphilis. As a result of these discoveries, these forms of psychopathology began to be classified and treated as forms of neuropathology. If all the conditions that are now called "mental illness" are diseases of the brain, then it will not be strange that this term will lose its meaning. However, since the term refers to some people's judgment of other people's (bad) behavior, the opposite is true. The history of psychiatry is the history of the over-expansion of the list of mental disorders.

If all the conditions that are now called "mental illness" are diseases of the brain, then it will not be strange that this term will lose its meaning. However, since the term refers to some people's judgment of other people's (bad) behavior, the opposite is true. The history of psychiatry is the history of the over-expansion of the list of mental disorders.

Changing perspectives of human life (and disease)

The thesis that I put at the forefront in "The Myth of Mental Illness" was nothing new. It only seemed and seems to be so today, since we have replaced the old religious-humanistic perspective with the tragic nature of modern life - dehumanized and pseudo-medical.

The separation of everyday life from religion (secularization), with the medicalization of the soul and the human suffering inherent in life, can be traced in England since the late 16th century. It was preceded by Shakespeare's Lady Macbeth. Overcoming guilt after the murders she committed, Lady Macbeth "goes crazy": she is agitated, anxious, unable to eat, rest or sleep. Her behavior disturbs Macbeth, who sends for a doctor for his wife to treat her. The Doctor arrives, quickly recognizes the source of Lady Macbeth's problems, and tries to thwart Macbeth's attempts to medicalize his wife's disorders:

Her behavior disturbs Macbeth, who sends for a doctor for his wife to treat her. The Doctor arrives, quickly recognizes the source of Lady Macbeth's problems, and tries to thwart Macbeth's attempts to medicalize his wife's disorders:

Her illness is not my part...

A sick conscience is only a deaf pillow

He dares to trust his secrets.

She needs a priest more,

than doctor

(act V, scene 1, translated by B. Pasternak) [7].

Macbeth rejects the doctor's diagnosis and demands that the doctor treat his wife. Then Shakespeare puts immortal words into the doctor's mouth, exactly the opposite of what psychiatrists and public health say and think:

Macbeth. Well, how sick, doctor?

Dr. Sovereign,

She is not as sick as the whirlwind of visions

Disturbs the world of her soul.

Macbeth. Spare her this.

Think up,

How to delete traces from memory

Nesting sadness, so that in consciousness

Erase memories writing

And means that give oblivion,

Release Tormented Chest

From the appendages that clog it.

Dr. The patient himself must

help yourself

(act V, scene 1, translated by B. Pasternak) [7].

Shakespeare recognizes as something deep and obvious that a mad man must cope for himself. Profound because the observed suffering forces one to help to do something for the sufferer. This is obvious because, in understanding Lady Macbeth's suffering as the result of an inner conversation (imaginations, hallucinations, the voice of consciousness), the means must also be inside (self-talk, "inner guidance").

Perhaps a brief comment about the inner conversation is needed here. In my book "The Meaning of Reason" [8] I pointed out that even Plato expressed the view of thinking as a conversation with oneself. At the request of Theaetetus of Athens to describe the process of thinking, Socrates replied: “This is a serious conversation that the mind has about any subject under consideration ... the thinking mind speaks to itself” [8]. (This is a modern translation. Ancient Greek did not have the word "mind" as a noun.)

Ancient Greek did not have the word "mind" as a noun.)

By the end of the 19th century, the medical capture of the soul had taken hold. Only philosophers and writers remained among those who denounced this tragic mistake. Sшren Kierkegaard warned: “In our time, the doctor who tries to heal the soul must know what he is doing. [Doctor] "You should go to the watering place, ride and have fun, have fun, have fun to the fullest..." - [Patient] "Calm down the anxious mind?" - [Doctor] "Nonsense! Get it out of your head! Anxious mind! There is no such thing at all” [9, With. 57].

Today, the role of a doctor as a healer of the soul is undeniable [10]. Bad people no longer exist, they are just mentally ill. "Protection by madness" cancels transgression, sin, temptation and tragedy. Lady Macbeth is human, like any of us, a "fallen being", she is human because she is mentally ill, she, like other people, is good, but mental illness makes her act unsoundly: "The current trend among critics is to take a new look at Lady Macbeth, her madness and suicide, makes her human again" [9].

Mental illness through the eyes of an outside observer

Everything I have read, observed, and studied supports my teenage impression that the behavior we call mental illness, and which has thousands of derogatory labels in our lexicon of insanity, is not a physical illness. It is the dissemination of the product of the medicalization of behavior, i.e. the observed constructs and definitions of a person's behavior are referred to as a clinical abnormality and indicate the need for treatment. Such a cultural transformation of modern medical ideology has largely replaced the old theological views and aroused political and professional interest.

In principle, medical practice always presupposes the consent of the patient, even if in fact this principle is sometimes violated. It follows from this principle that physical illness does not justify depriving the patient of liberty, but only in the event of legal failure (and sometimes a clear danger to others, for example, in infectious diseases). Thus, I came to the conclusion that only a few mentally ill people fall into the category of the sick, but the restriction of freedom and responsibility is based on the disease - literally and metaphorically - this is a gross violation of basic human rights.

Thus, I came to the conclusion that only a few mentally ill people fall into the category of the sick, but the restriction of freedom and responsibility is based on the disease - literally and metaphorically - this is a gross violation of basic human rights.

In medical school, I began to realize that my interpretation was correct. Mental illness is a myth, and it is foolish to look for causes and cures for such a fictitious illness. This understanding further strengthened my moral opposition to the power that psychiatrists have over their patients.

Physical illnesses have causes, such as infectious agents or dietary deficiencies, and can often be prevented or cured by addressing those causes. People who are said to be mentally ill, on the other hand, have the right to do as they see fit. They cannot be treated or corrected with drugs or other medical interventions, but it is possible to benefit them by respecting them, understanding their predicament, and helping them to cope independently with the obstacles they face.

Pathologists use the term "disease" to refer to a physical entity—cells, tissues, organs, and the body. Pathology textbooks describe changes in the body of the living or deceased, but not his personality, outlook and behavior. René Leriche, the founder of modern vascular surgery, easily remarked: “If someone wants to define a disease, it must be dehumanized… In a disease, when all is said and done, the person is the last one” [11].

In practical pathology and the scientific concept of disease, human suffering is not important. On the contrary, in practical medicine, in the system of care and the legal requirements of society, the person as a patient is of the highest importance. Why? Because in the practice of Western medicine, the requirement 9 is paramount.0131 primum non nocere (“do no harm!”) and allows the freedom of the patient not to seek help, accept medical care (diagnosis and treatment) or refuse it. In psychiatric practice, on the contrary, it is assumed that a mentally ill patient can be dangerous to himself or others, and the moral and professional duty of a psychiatrist is to protect the patient from himself, and society from the patient [3].

In accordance with the scientific criteria of pathology, the disease is a material phenomenon, it has verifiable characteristics in the body, so temperature is a verifiable characteristic of the disease. On the contrary, the diagnosis of disease in a patient is the judgment of a licensed physician, which is similar to the judgment of a certified appraiser on a work of art. Having a disease is not the same as being a patient in your professional capacity: not all patients are patients, and not all patients are ill. Be that as it may, doctors, politicians, the press, and the general public combine and confuse these two different categories [12].

Revisiting the Myth of Mental Illness

In the preface to The Myth of Mental Illness, , I unequivocally stated that this book did not contribute anything to psychiatry: “This is not a textbook on psychiatry ... psychiatrists and their patients, to understand what they do for each other" [2, p. XI].

Nevertheless, many critics have misunderstood and continue to misunderstand it as a super-radical attempt to turn mental illness from a medical problem into a linguistic-rhetorical phenomenon. It is not surprising that most of the positive assessments of my work are made not by psychiatrists, but by those who do not feel threatened by my revision of psychiatry and related fields [13, 14]. One of the most promising such assessments is made in the essay "The Rhetorical Paradigm in the History of Psychiatry: Thomas Szasz and the Myth of Mental Illness" by communication professor Richard E. Vatz and law professor Lee S. Weinberg. They wrote: “In his rhetorical attack on the medical paradigm in psychiatry, Szasz not only argued for an alternative paradigm, but also spoke clearly of psychiatry as a pseudo-science, comparing it with astrology ... accepting the rhetorical paradigm is completely impossible, since it represents a profound change - almost a refusal from psychiatry as a field of scientific knowledge. The vocabulary of the two paradigms is completely different and incompatible... Szasz only insists that psychiatric patients are moral persons, just like psychiatrists... In the rhetorical paradigm, a psychiatrist who suppresses a person with his power is considered in conclusion, rather than providing a “treatment”, the language with which psychiatrists defend themselves against moral responsibility for their actions.

It is not surprising that most of the positive assessments of my work are made not by psychiatrists, but by those who do not feel threatened by my revision of psychiatry and related fields [13, 14]. One of the most promising such assessments is made in the essay "The Rhetorical Paradigm in the History of Psychiatry: Thomas Szasz and the Myth of Mental Illness" by communication professor Richard E. Vatz and law professor Lee S. Weinberg. They wrote: “In his rhetorical attack on the medical paradigm in psychiatry, Szasz not only argued for an alternative paradigm, but also spoke clearly of psychiatry as a pseudo-science, comparing it with astrology ... accepting the rhetorical paradigm is completely impossible, since it represents a profound change - almost a refusal from psychiatry as a field of scientific knowledge. The vocabulary of the two paradigms is completely different and incompatible... Szasz only insists that psychiatric patients are moral persons, just like psychiatrists... In the rhetorical paradigm, a psychiatrist who suppresses a person with his power is considered in conclusion, rather than providing a “treatment”, the language with which psychiatrists defend themselves against moral responsibility for their actions. .. The rhetorical paradigm poses a significant threat to institutional psychiatry... having lost the medical model as its defense, psychiatry will become a little less than mechanism for social control, and above all the main violator of personal freedom and autonomy, which is acceptable under the cover of medicine” [15].

.. The rhetorical paradigm poses a significant threat to institutional psychiatry... having lost the medical model as its defense, psychiatry will become a little less than mechanism for social control, and above all the main violator of personal freedom and autonomy, which is acceptable under the cover of medicine” [15].

Later, the famous medical historian Roy Porter summarized my thesis as follows: “All expectations of finding the etiology of mental illness in the body or in the mind are not Freud's subconscious. From Szasz's point of view, this categorical fallacy or blind faith is the standard psychiatric approach to insanity, whose history is distorted by criminal assumption and misguided questions" [16].

Having a disease does not make a person a patient

One of the most criminal assumptions inherent in the standard psychiatric approach to insanity is the treatment of the mentally ill who is seen as in need of psychiatric treatment, whether seeking or rejecting such help. In this regard, two specific difficulties are evident to psychiatry, but often go unnoticed, namely, that the term refers to two radically opposite types of practice: the treatment / healing of the soul through conversation and the correction / control of the person using force, which is authorized and required by the state. . Critics of psychiatry, journalists and the public are unable to distinguish between voluntary counseling of clients and prisoners of the correctional psychiatric system.

In this regard, two specific difficulties are evident to psychiatry, but often go unnoticed, namely, that the term refers to two radically opposite types of practice: the treatment / healing of the soul through conversation and the correction / control of the person using force, which is authorized and required by the state. . Critics of psychiatry, journalists and the public are unable to distinguish between voluntary counseling of clients and prisoners of the correctional psychiatric system.

In the past, when church and state were not separated, people accepted the theologically justified sanctions of the state for correction. Today, when medicine is not separated from the state, people accept therapeutically justified sanctions for correction. That is why 200 years ago psychiatry became a tool in the hands of the correctional apparatus of the state. And so all of today's medicine is threatened by the transformation of individual care into political control.

The problem discussed in this article is not new. One hundred years ago Eugen Bleuler in his great work Dementia Praecox came to a conclusion which reflects the following: “The most serious of all schizophrenic symptoms are suicidal intentions. I can even clearly state that the social system that exists today requires a great and completely unacceptable cruelty from the psychiatrist in this respect. People are understandably forced to continue living unbearable lives... Most of our worst restraints would not be necessary if we were not required to bind the patient in order to save his life, which for him, as for many others, is of no value. If all this at least served this purpose!... At the present time we psychiatrists are saddled with the tragic duty of obedience to the cruelty of society, but our duty is to do everything possible to change this view in the near future” [17].

One hundred years ago Eugen Bleuler in his great work Dementia Praecox came to a conclusion which reflects the following: “The most serious of all schizophrenic symptoms are suicidal intentions. I can even clearly state that the social system that exists today requires a great and completely unacceptable cruelty from the psychiatrist in this respect. People are understandably forced to continue living unbearable lives... Most of our worst restraints would not be necessary if we were not required to bind the patient in order to save his life, which for him, as for many others, is of no value. If all this at least served this purpose!... At the present time we psychiatrists are saddled with the tragic duty of obedience to the cruelty of society, but our duty is to do everything possible to change this view in the near future” [17].

Here I would like to point out that it would be a serious mistake to interpret this passage in such a way that we psychiatrists define and devalue persons diagnosed with schizophrenia, that their life is worthless. On the contrary, Bleuler, an exceptionally fine man and compassionate physician, stands up for recognizing the right of schizophrenics to determine and manage their lives, and psychiatrists should not deprive them of their freedom, taking their lives into their own hands.

On the contrary, Bleuler, an exceptionally fine man and compassionate physician, stands up for recognizing the right of schizophrenics to determine and manage their lives, and psychiatrists should not deprive them of their freedom, taking their lives into their own hands.

Despite Bleuler's great influence on world psychiatry, psychiatrists ignored his request to resist "obedience to the views of a cruel society." Ironically, the opposite happened: the schizophrenia discovered by Bleuler began to rapidly become medicalized, such a pseudo-science as suicidology appeared, which led psychiatry to plunge into the moral swamp in which it is located.

This article was presented at the International Congress of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Edinburgh on 24 June 2010. Szasz T. The myth of mental illness: 50 years later // The Psychiatrist. - 2011. - 35. - 179-182.

Editorial . The publication in 1960 of the book The Myth of Mental Illness by professional sociologist Thomas Sasz caused shock not only in the United States. They talked about it, wrote about it, argued about it. It was this book that formed the social phenomenon of antipsychiatry, the most pronounced, powerful in English-speaking countries. The scandal turned out to be very useful, first of all, for the most practical psychiatry. A radical look at the history of psychiatry, at the very subject of its competence, made it possible to change a lot. Philosophers, sociologists, psychologists, legal theorists and psychiatrists themselves (yes, there were some), who accepted the ideas of Thomas Szasz, allowed the psychiatric majority to see themselves for the first time in a kind of worldview "mirror". And when they saw their real image in this “mirror”, the majority changed. Realizing the shortcomings of traditional diagnostic practice, the psychiatric community of the 1960s and 70s introduced clear, specific diagnostic criteria into the classification of mental disorders. Thanks to the influence of antipsychiatrists, treatments that have not been backed up by rigorous scientific research have become a thing of the past.

They talked about it, wrote about it, argued about it. It was this book that formed the social phenomenon of antipsychiatry, the most pronounced, powerful in English-speaking countries. The scandal turned out to be very useful, first of all, for the most practical psychiatry. A radical look at the history of psychiatry, at the very subject of its competence, made it possible to change a lot. Philosophers, sociologists, psychologists, legal theorists and psychiatrists themselves (yes, there were some), who accepted the ideas of Thomas Szasz, allowed the psychiatric majority to see themselves for the first time in a kind of worldview "mirror". And when they saw their real image in this “mirror”, the majority changed. Realizing the shortcomings of traditional diagnostic practice, the psychiatric community of the 1960s and 70s introduced clear, specific diagnostic criteria into the classification of mental disorders. Thanks to the influence of antipsychiatrists, treatments that have not been backed up by rigorous scientific research have become a thing of the past. The very term psychiatric deinstitutionalization is from those times. At the same time, the priority of outpatient care was adopted and implemented. Psychiatric hospitals have become smaller, living conditions and treatment in them are better, the time spent by patients there is much shorter.

The very term psychiatric deinstitutionalization is from those times. At the same time, the priority of outpatient care was adopted and implemented. Psychiatric hospitals have become smaller, living conditions and treatment in them are better, the time spent by patients there is much shorter.

They were called extremists, fanatics, pseudo-professionals. Well, some of them were like that... But it was they who changed the practical psychiatry, humanized it. Our Western colleagues, having experienced the acute shock of the public scandal at first, soon made a wise decision: to understand and, if possible, accept the arguments of anti-psychiatrists. So, Thomas Sas himself was elected an honorary professor at several US medical universities, received prestigious awards, his books and articles are still of interest to readers. He is still alive today, still socially active. One of his latest works we offer today in our magazine.

Antipsychiatry is a thing of the past. The world has changed, the psychiatric doctrine has changed.