Baby sign language statistics

Research on Baby Sign Language

Research on baby sign language has found that teaching baby signs improved cognitive and emotional development. Far from slowing down speech, baby sign language actually increases the rate of verbal development and at the same time increases the parent/child bond.

The most significant research was an NIH-funded study comparing two groups of 11-month-old babies. One group was taught baby sign language. The second group was given verbal training. Surprisingly, the signing group were more advanced talkers than the group given verbal training. The lead of the signing group continued to grow, with the signers exhibiting verbal skills three months ahead of the non-signers at two years old. Their lead seemed to shrink a little after two years old, but even at three years old, the signers were still ahead 1.

The authors of the NIH study followed up with the children at eight years old. Surprisingly, there was still a difference. Signers showed IQ’s 12 points higher than the non-signers, even though they had long since stopped signing. This put the signers in the top 25% of eight year olds, compared to the non-signers, who were close to average2.

Results like these have led to research on how signing could be used to improve early infant education. This research has turned up a whole host of benefits to signing. Some of these benefits include making mothers feel better about themselves and more “tuned in” to their baby, reducing baby distress and improving communication between parent and child3.

Now keep in mind that these studies have all been relatively small – the NIH-funded study, for example, had only 100 babies. However, these early results look very promising. These results, combined with all the anecdotal reports from signing parents, gives a lot of reason to be very optimistic about the results from future baby sign language research.

1. Susan W. Goodwyn, Linda P. Acredolo and Catherine A. Brown. Impact of Symbolic Gesturing on Early Language Development, Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 24, 81-103 (2000). Link to paper

Link to paper

2. Linda P. Acredolo, and Susan W. Goodwyn, The Longterm Impact of Symbolic Gesturing During Infancy on IQ at Age 8, International Conference on Infant Studies (July 18, 2000: Brighton, UK).

3. Claire D. Vallotton, Catherine C. Ayoub, Symbols Build Communication and Thought: The Role of Gestures and Words in the Development of Engagement Skills and Social-Emotional Concepts During Toddlerhood, Social Development 19:3,601-626 (August 2010) Link to abstract

If you found this information useful, check out our award-winning baby sign language kit. It includes more than 600 signs, covers advanced teaching methods for faster results, and includes fun teaching aids like flash cards.

The Deluxe Baby Sign Language Kit, bundles together everything you need to get started with signing in one box, at a steep discount. The kit includes: (1) Baby Sign Language Guide Book; (2) Baby Sign Language Dictionary; (3) Baby Sign Language Flash Cards; and (4) Baby Sign Language Wall Chart.

Baby Sign Language Guide Book shows you how to teach your child how to sign. The book begins with a Quick Start Guide that will teach you your first signs and get you ready to sign in 30 minutes. As your baby progresses, you can delve into more advanced topics like combining signs to make phrases, using props, and transitioning to speech. (Regularly $19.95)

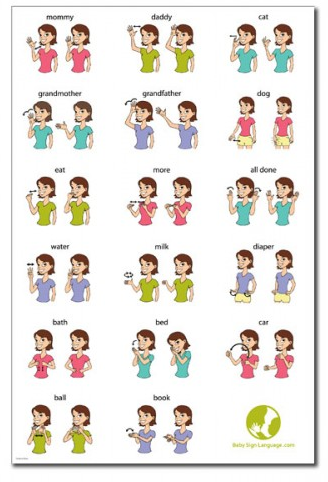

Baby Sign Language Dictionary contains over 600 signs, including the most common words, the alphabet and numbers. The dictionary helps you expand your child’s vocabulary and has the breadth of coverage that lets you follow any child’s natural interests. Each sign is illustrated with two or more diagrams, showing you the starting position, the ending position, and intermediate motion. This makes learning new signs easy. (Regularly $19.95)

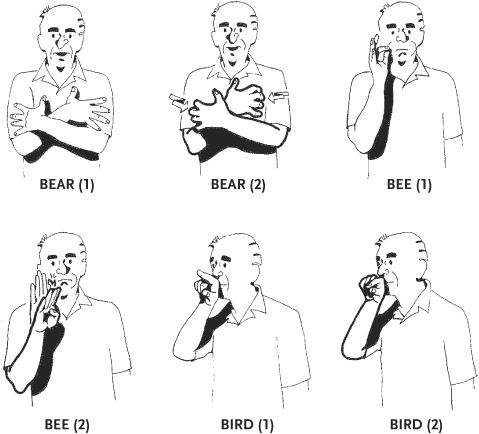

Baby Sign Language Flash Cards include 52 sturdy board (4×6 inches) flash cards, covering a variety of basic signs. The flash cards allow you to teach words, such as animal names, that Baby is not exposed to in everyday life. The face of the flash cards shows the word and image for the child. The back of the flash cards show how the sign is performed – a handy reminder for the adult. (Regularly $24.95)

The flash cards allow you to teach words, such as animal names, that Baby is not exposed to in everyday life. The face of the flash cards shows the word and image for the child. The back of the flash cards show how the sign is performed – a handy reminder for the adult. (Regularly $24.95)

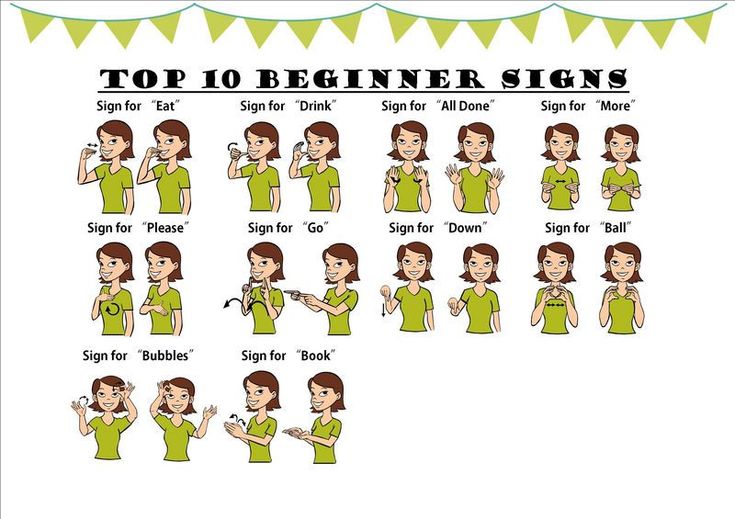

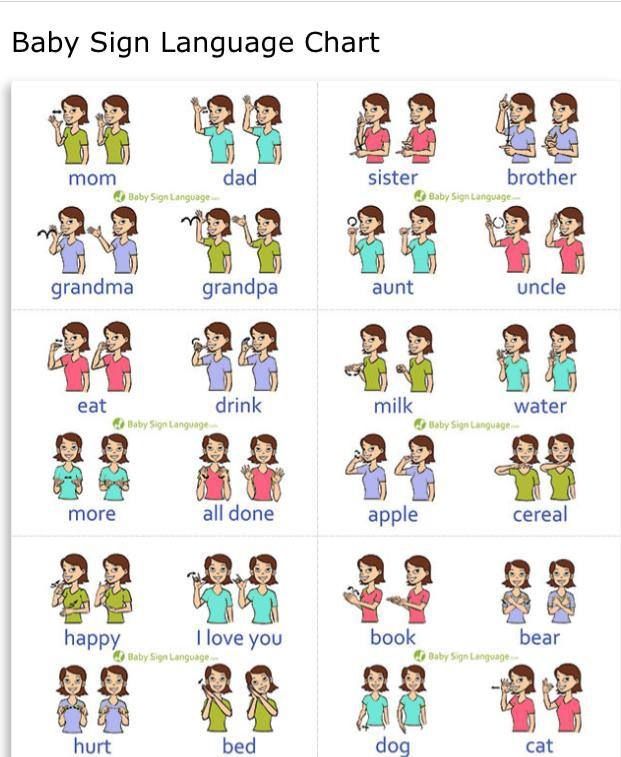

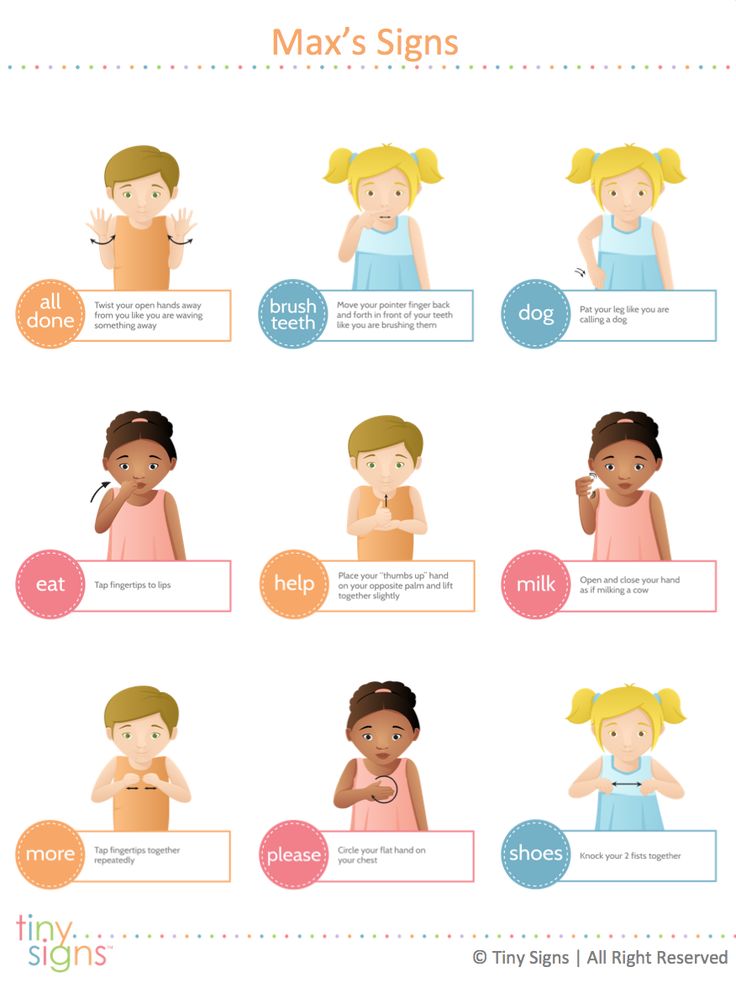

Baby Sign Language Wall Chart includes 22 basic signs and makes a handy reminder for caregivers. The Baby Sign Language Wall Chart covers basic signs, like eat, drink, and sleep. Hang the poster in Baby’s nursery to help babysitters or other occasional caregivers learn and decode the most commonly used baby signs. (Regularly $9.95)

100% Signing Guarantee

Your baby signs to your complete satisfaction, or you get a full refund.

No questions. No time limits. No regrets.

Baby Sign Language Guide Book

Learn the best techniques for effectively teaching baby sign language. Including:

Including:

• Quick Start Guide – learn the first 10 signs and the basic principles required to start teaching your baby to sign (Chapter 1).

• Advanced Teaching Methods – use teaching aids like books, flash cards, and toys to keep lessons interesting and challenging (Chapter 5).

• Phrases – teach your baby to combine signs and communicate more complex thoughts (Chapter 6).

• Taming the Terrible Twos – reduce frustration and tantrums by enabling your toddler to communicate (Chapter 7).

• Transitioning to Speech – use sign language to expedite and improve speech development (Chapter 8).

Sarah learned her first 10 signs at six month and it made our lives much easier. Instead of screaming, she could tell us when she was hungry, thirsty, or tired. She learned another 50 signs by nine months and that was a blast. Now she is talking much earlier than the other children in her preschool and we think it is because of her signing.

We can’t imagine missing out on all the little things she shared with baby sign language. Thank You!

– Bennett & Melissa Z., CA

Pediatrician Approved

“It’s easy to see why so many parents swear by it, why child care centers include it in their infant and toddler classrooms, and why it has become so commonplace as an activity of daily learning … we approve.”

Heading Home With Your Newborn (Second Edition)

Dr. Laura A. Jana MD FAAP & Dr .Jennifer Shu MD FAAP

American Academy of Pediatricians

Baby Sign Language Flash Cards

52 high quality flash cards (4 x 6″). Featuring:

• Clean Images – real life pictures, isolated on a white background to make learning easier.

• Signs on the Rear – diagrams on the back illustrating the signign motion in case you need a reminder.

• Baby Friendly – printed on thick stock so little hands can play with the cards and they will live to play another day.

I was thrilled to see how easy the signs were for Abigail (3) and Eden (21 months). Much to my surprise they could figure out many of the signs from the flashcards on their own.

– Carrie P., TX

Study: Signing Enriches

“The Sign Training group told us over and over again … [signing] made communication easier and interactions more positive.”

“these data demonstrate clearly that … [signing] … seems to “jump start” verbal development”

“can facilitate and enrich interactions between parent and child”

Impact of Symbolic Gesturing on Early Language Development

Dr. Susan Goodwyn, Dr. Linda Acredolo, & Dr. Catherine Brown

Journal of Nonverbal Behavior

Baby Sign Language Dictionary

The Baby Sign Language Dictionary includes :

• Words (500+) – learn signs for nearly every topic of interest.

• Letters – sign the alphabet and teach basic spelling.

• Numbers (0-10) – introduce counting and basic mathematics.

Nicholas loves his signs and it lights up our lives every time he shares one of his little secrets. He is so observant, and we would miss it all without the signs.

– Donald Family, NY

Baby Sign Language Wall Chart

The full color wall chart (24 x 36″) includes 17 everyday signs. Use the wall chart for:

• Caregivers – help babysitters and other caregivers learn the basic signs so they can understand baby’s signs.

• Family – teach family the basic signs so they can join in the fun.

Everyone thought I was nuts when I started. A month later, all my friends saw Michelle’s first signs. Then they wanted to know how they could start.

Then they wanted to know how they could start.

Michelle is talking now and doesn’t sign much anymore, but it gave her a headstart over other children her age. Everyone says she talks like a three year old. Now she is helping me teach her baby brother Jordan how to sign.

– Adelaide S., CA

Study: Better in School

A group of second graders who signed as infants, performed better academically than a control group six years later. The signers had a 12 IQ point advantage.

Longterm Impact of Symbolic Gesturing During Infancy at Age 8

Dr. Linda P. Acredolo (Professor, U.C. Davis)

Dr. Susan W. Goodwyn (Professor, California State University)

100% No Regret Guarantee

Your baby loves signing, or a full refund.

As you can tell, we love Baby Sign Language. It transformed the way we interacted with our children, and we want every family to have the opportunity. Baby Sign Language will make a difference for your child. Give it a try.

Give it a try.

If for any reason you aren’t completely blown away, we will cheerfully give you a complete refund, including standard shipping. No time limit. We are that confident!

A guide for the science-minded parent

© 2018 – 2022 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

What is “baby sign language”? The term is a bit misleading, since it doesn’t refer to a genuine language. A true language has syntax, a grammatical structure. It has native speakers who converse fluently with each other.

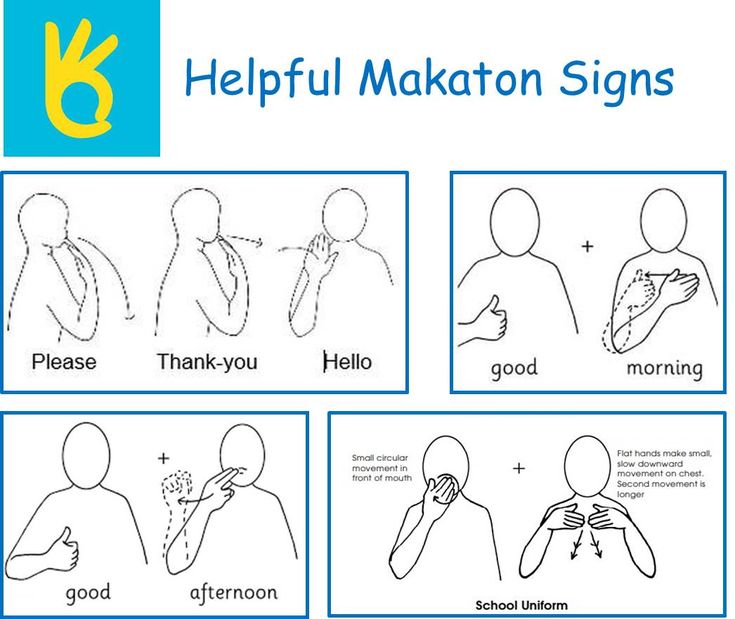

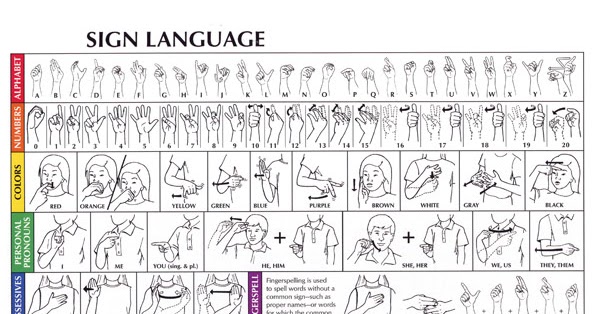

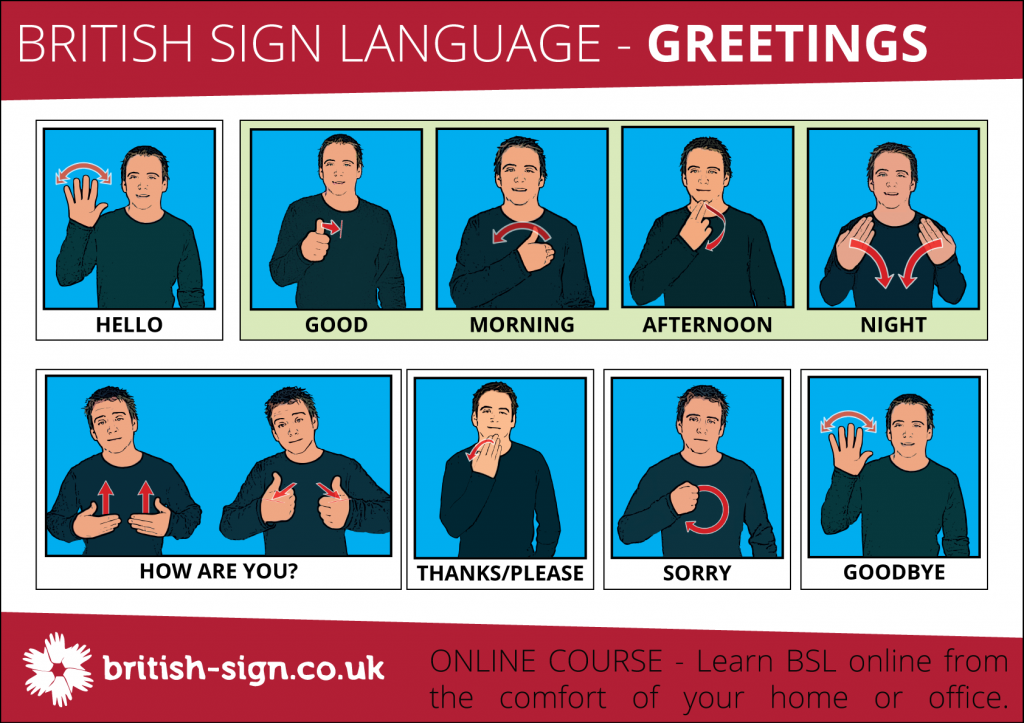

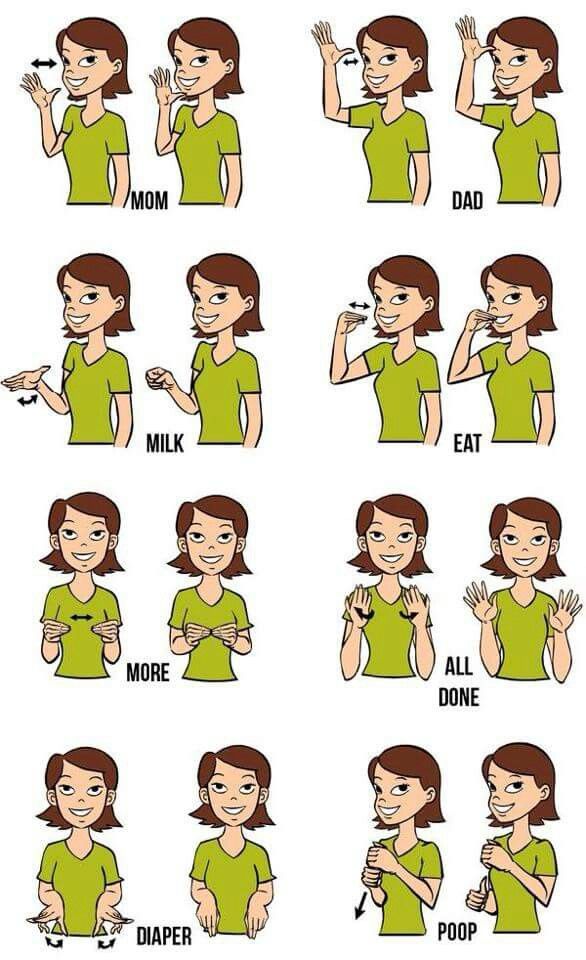

American Sign Language (ASL) and British Sign Language (BSL) are examples of genuine languages. By contrast, baby sign language, also known as baby signing, usually refers to the act of communicating with babies using a modest number of symbolic gestures. Parents speak to their babies in the usual way – by voicing words – but they also make use of these signs. For instance, a mother might voice the question, “Do you want something to drink?” while making the visual sign for “drink. ”

”

Is baby sign language the same as ASL? Or BSL?

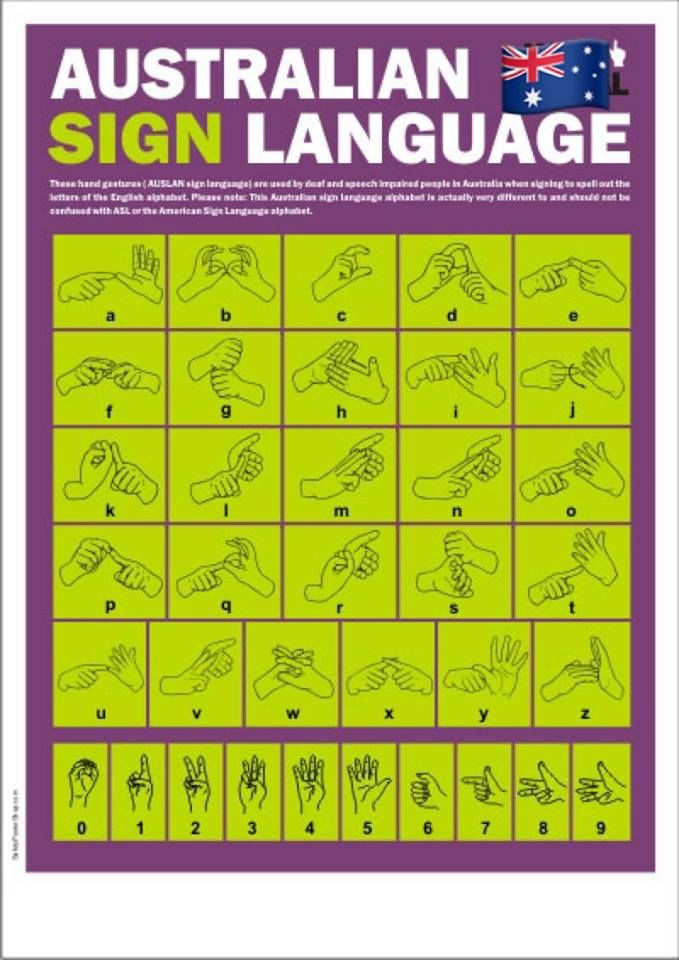

No, for the reasons stated above. But caregivers who teach baby sign language often use signs borrowed or adapted from the ASL or BSL lexicons.

Does baby sign language work?

The short answer is yes. It works in the sense that babies can learn to interpret and use signs. As I note below, research suggests that some babies start paying attention to signs by the age of 4 months (Novack et al 2022). By 8-10 months, they start producing signs themselves, and that can be an rewarding experience for families. But it isn’t clear that teaching babies to sign gives them any special, long-term, developmental advantages.

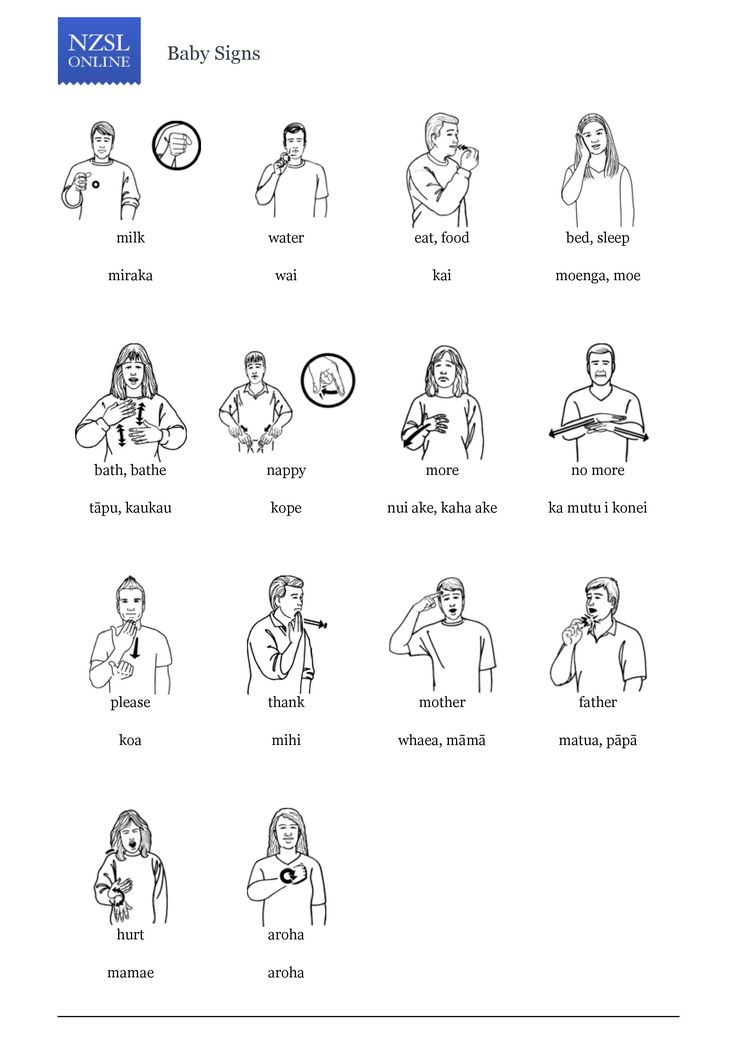

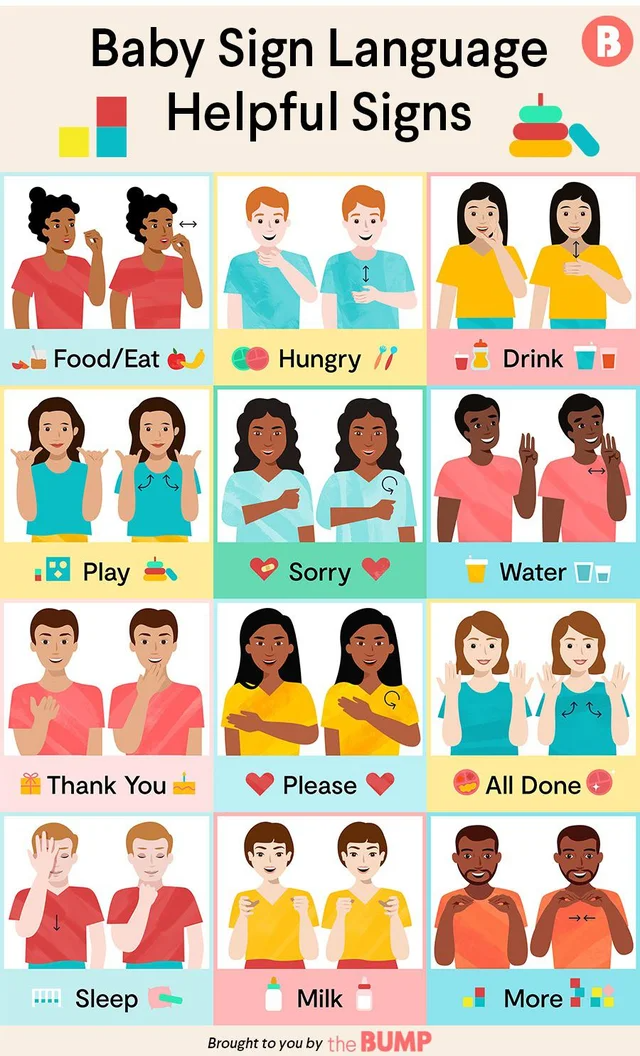

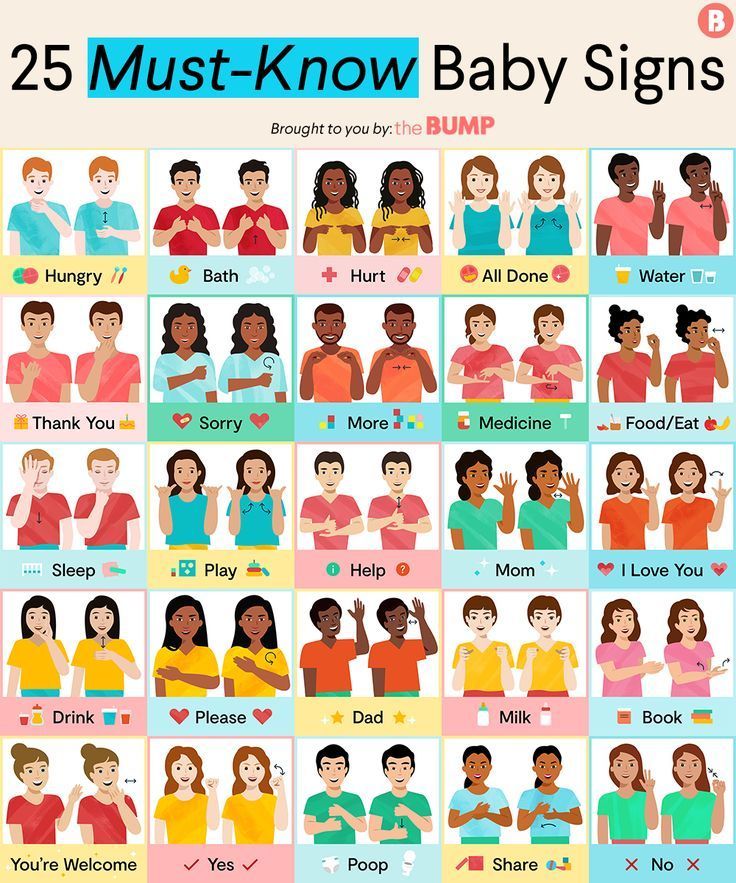

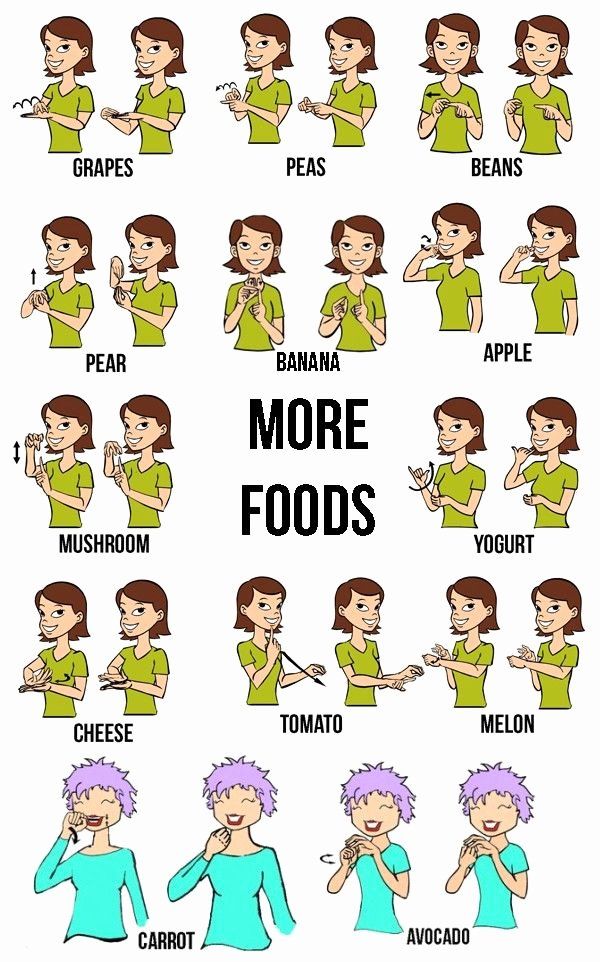

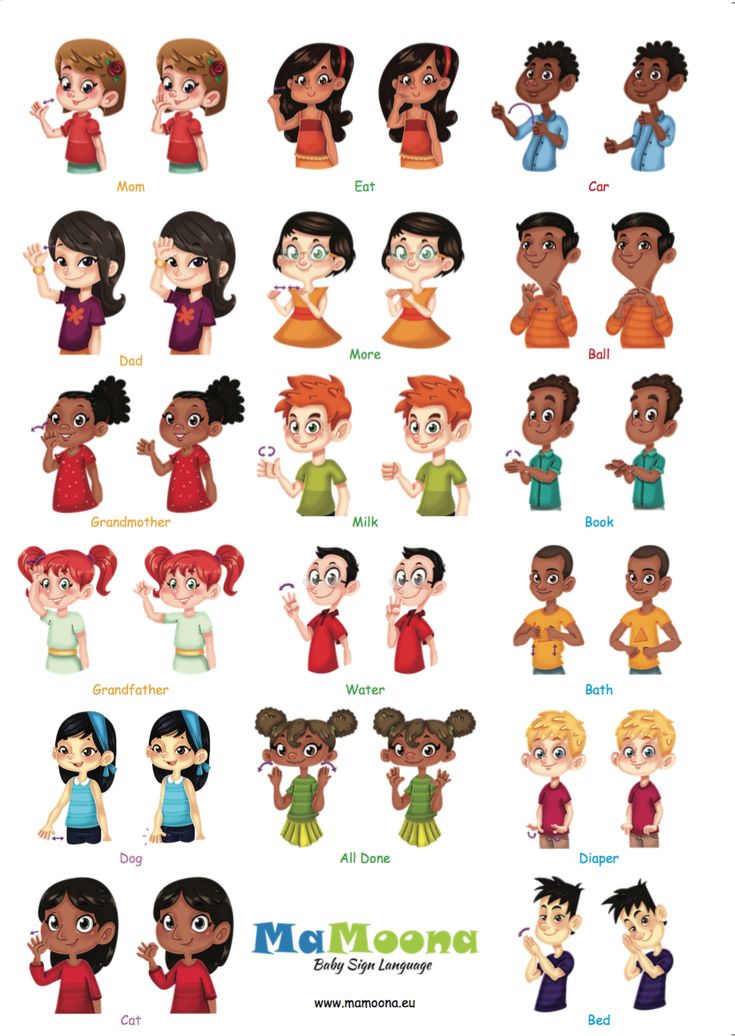

What signs do babies learn?

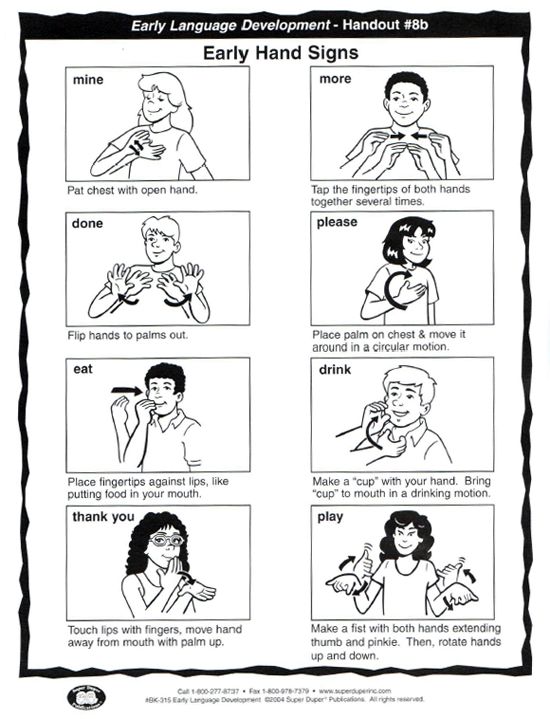

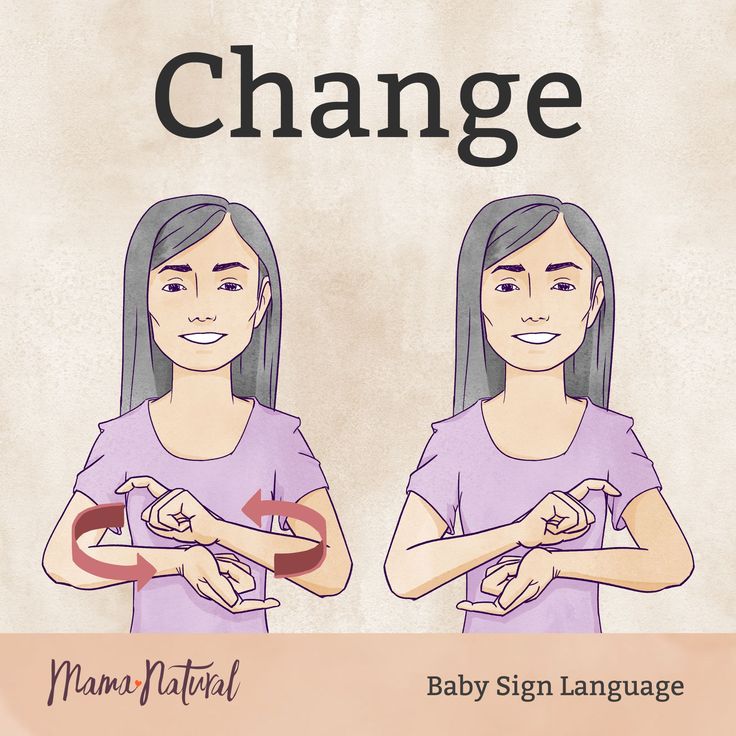

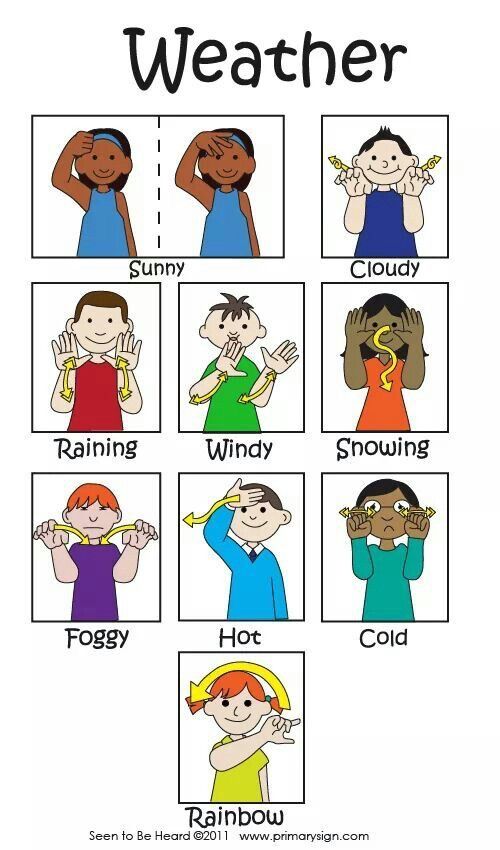

It depends. In some families, parents take a “DIY” approach. They notice helpful gestures that arise naturally during conversation— iconic gestures that “act out” or resemble the things they stand for. With deliberate use of these iconic gestures — and patient repetition — their babies eventually learn to interpret these gestures as signs.

For instance, suppose you take your baby outside and find that it’s very cold. You begin talking to your baby about it, and find yourself behaving like a mime: When you say the word “cold” you act out an exaggerated shiver with your arms. If you repeat this experience multiple times, your baby may learn to regard shivering arms as a sign for “cold.” You have invented your own sign!

In the same way, your family might invent a number of additional signs — signs based on pantomiming certain actions, or representing other creatures or objects with hand movements (like holding your hands to the side of your head to depict a rabbit with long ears).

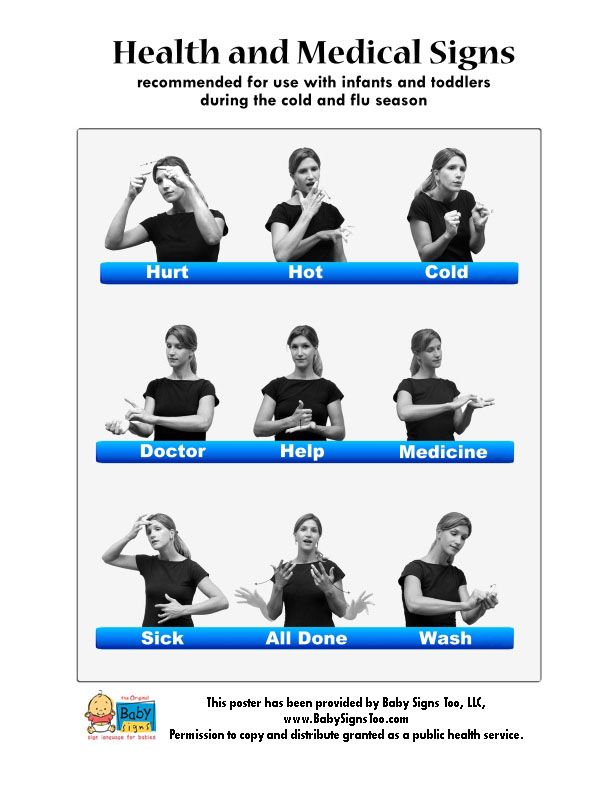

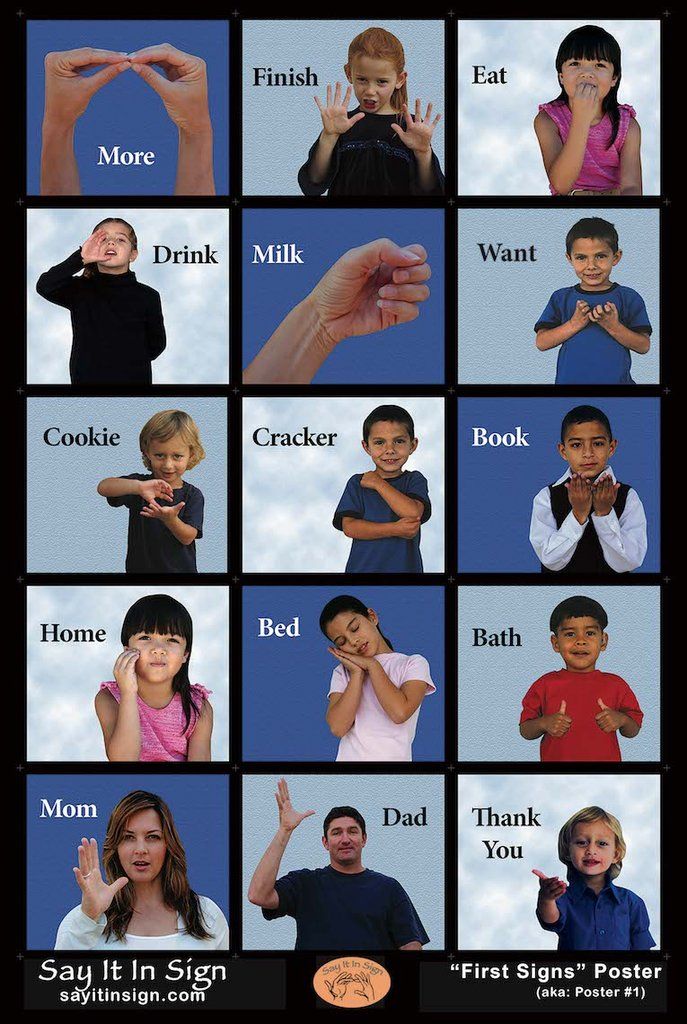

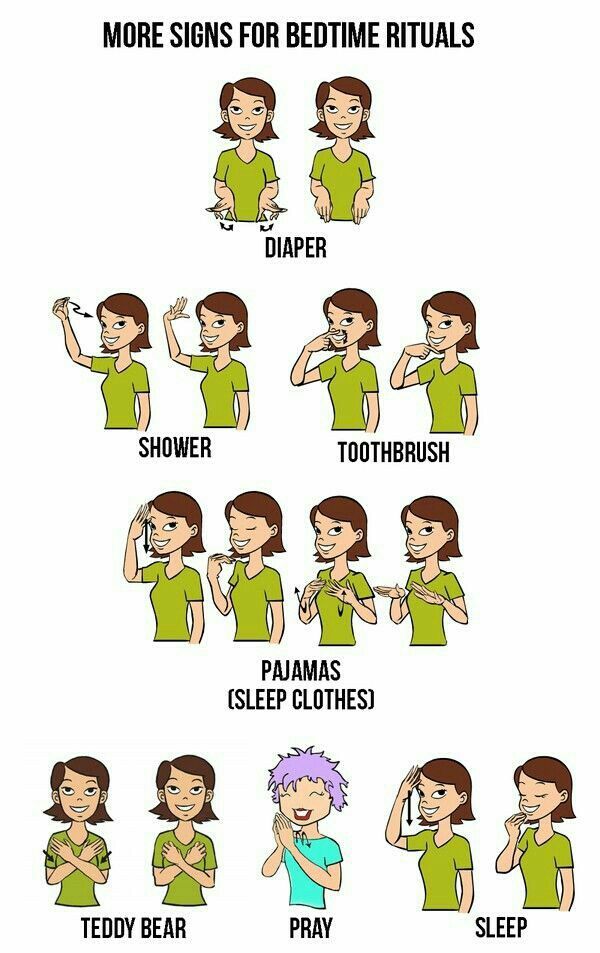

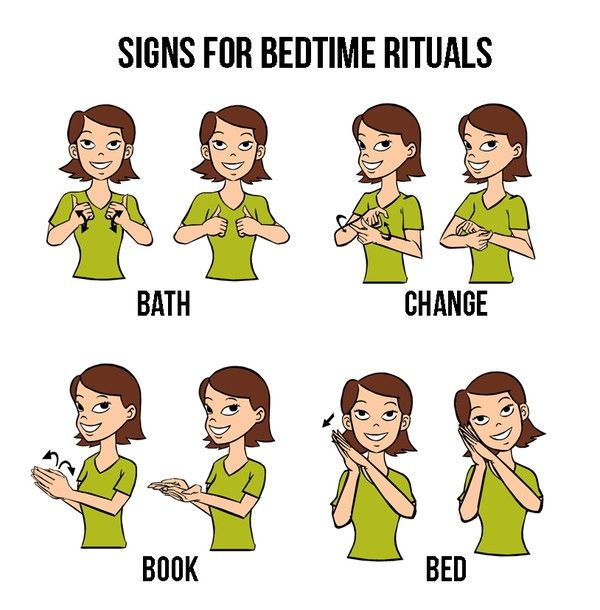

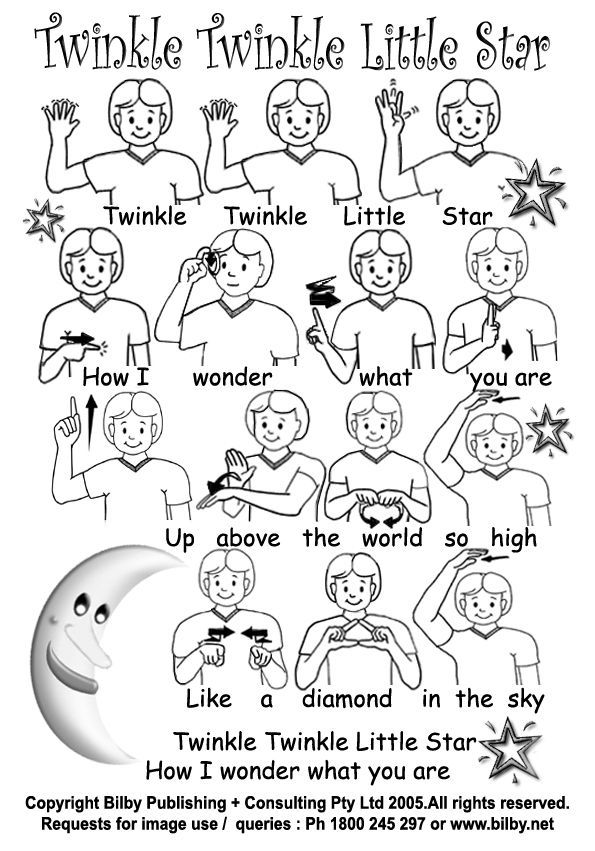

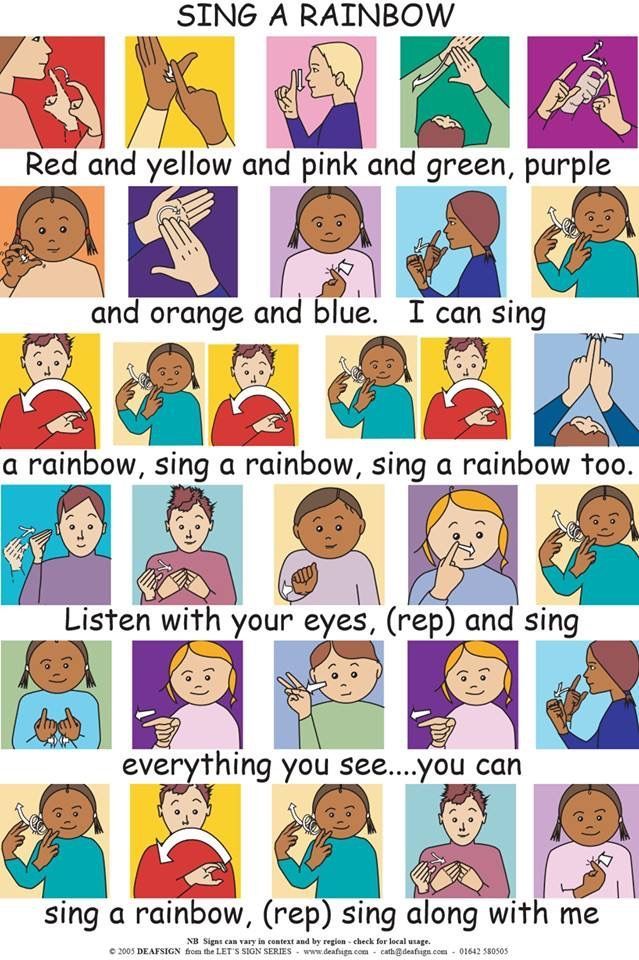

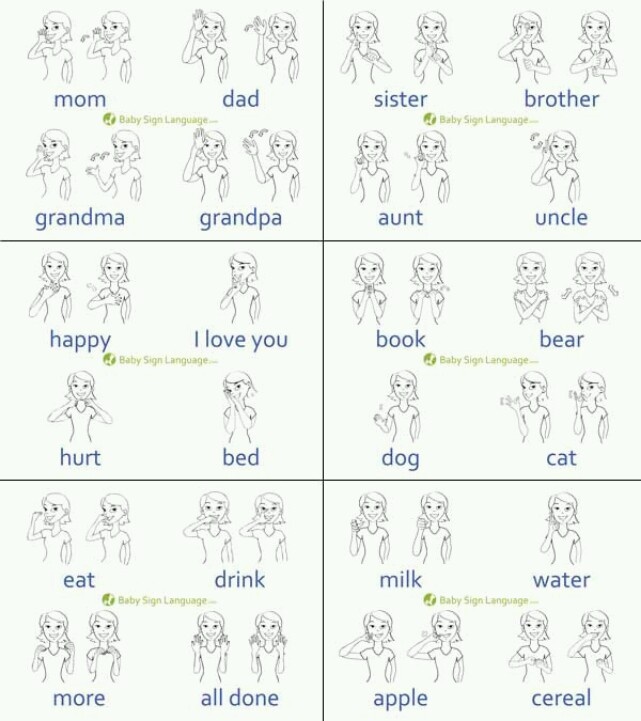

But there’s another, more standardized approach to baby sign language: teaching your baby a set of pre-existing signs from a chart, book, or video. As Lorraine Howard and Gwyneth Doherty-Sneddon (2014) note, such signs are often adapted from languages for the hearing impaired. And while some of these signs involve iconic gesturing, many others do not.

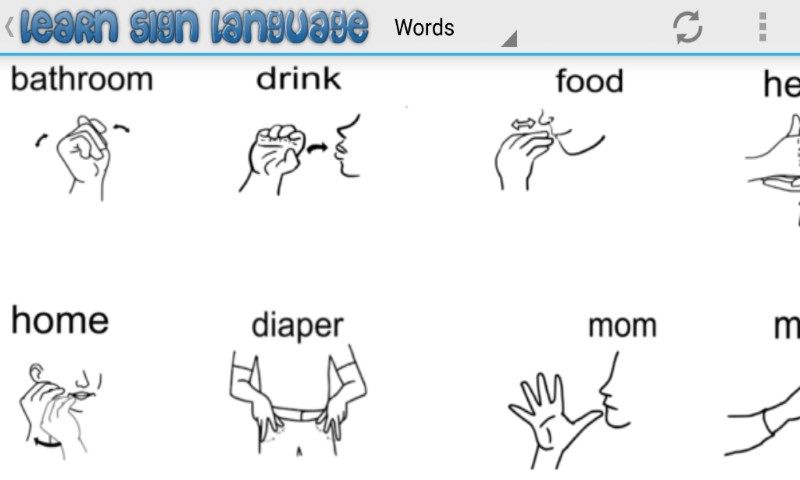

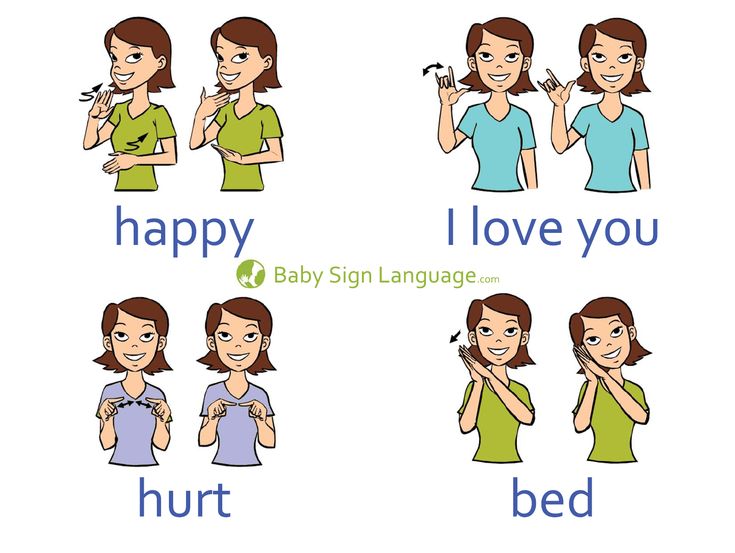

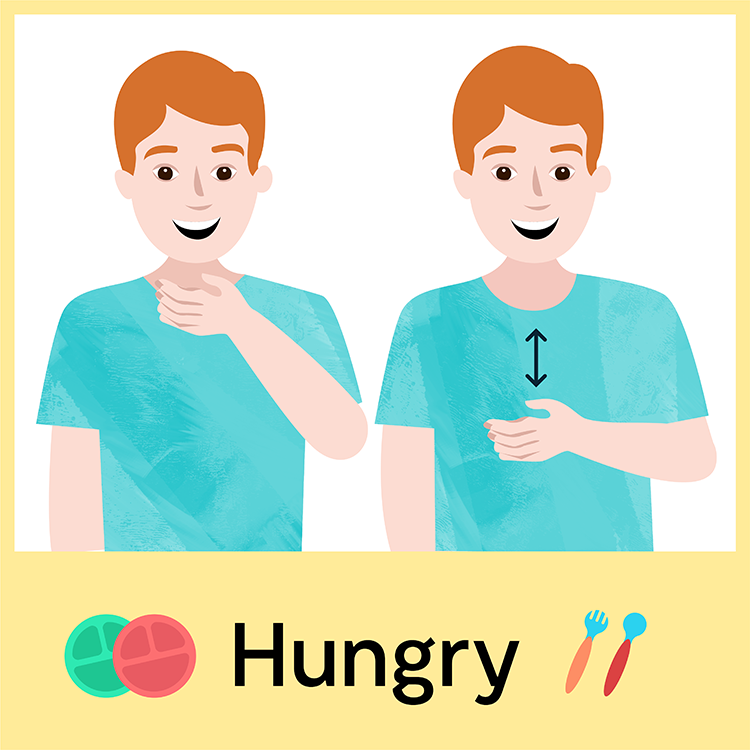

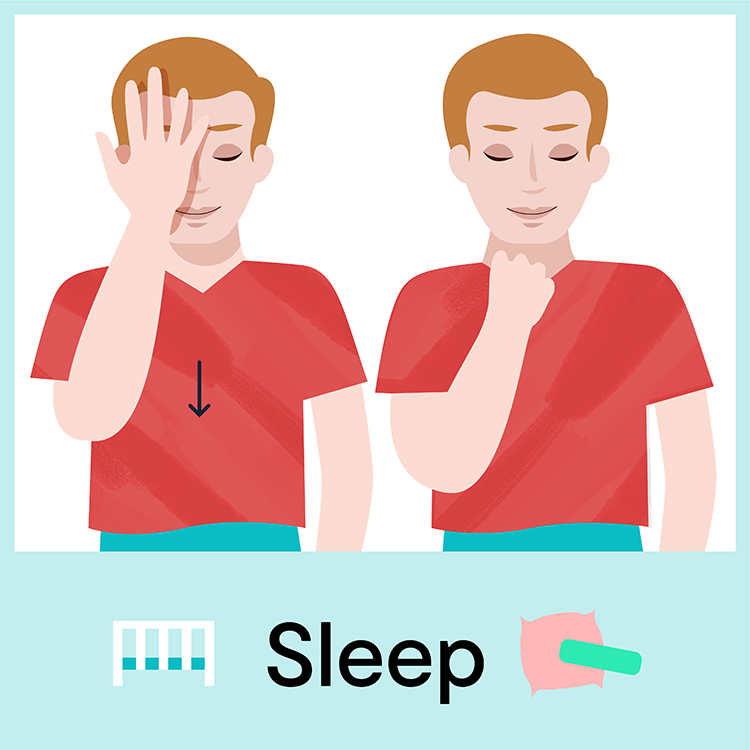

For example, consider the ASL sign for “drink.” As you can see from this illustration provided by Michael Fetters of the University of Michigan, the sign looks like you’re holding a cup to your mouth:

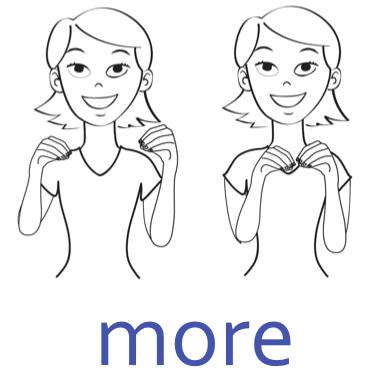

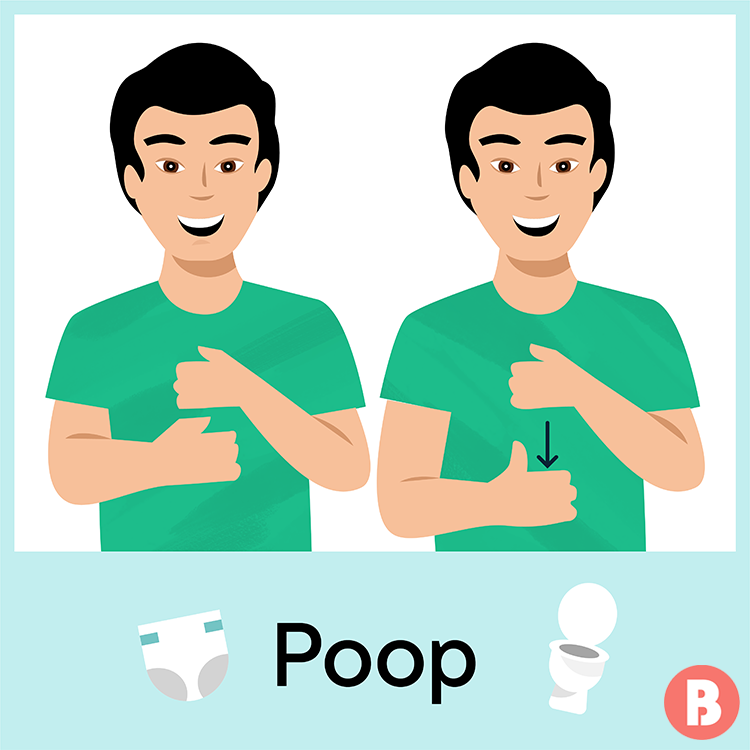

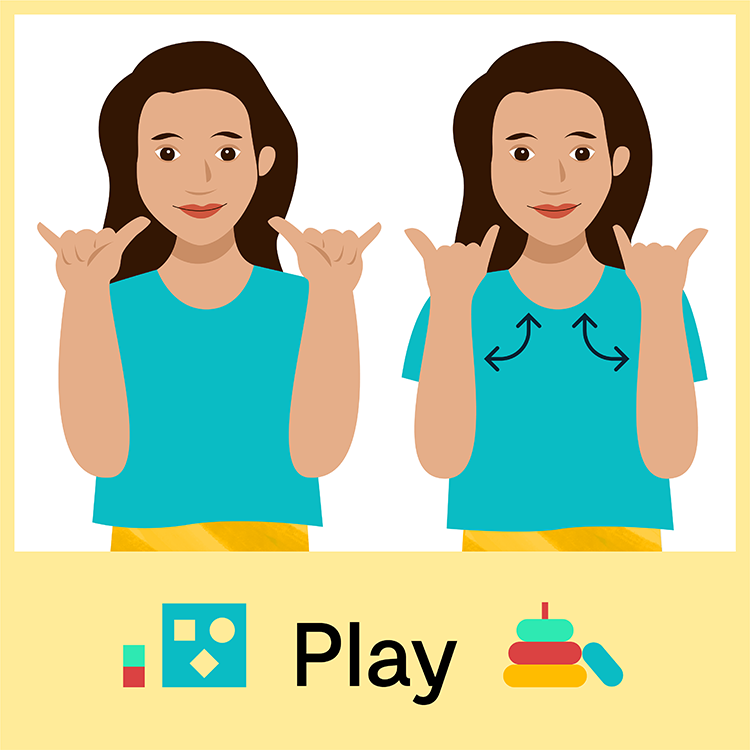

© 2012 Regents of the University of Michigan, courtesy Dr. Michael Fetters CC BY-SAIt’s very iconic. If you didn’t already know what this sign is supposed to mean, you could probably figure it out. But most ASL signs aren’t like this. The gestures don’t resemble the meaning in any obvious way. You can see what I mean in these illustrations of the ASL signs for “play”, “hurt”, and “mother” or “mommy”. The mapping of signs to meanings seems arbitrary, just as is the case for most spoken words.

© 2012 Regents of the University of Michigan, courtesy Dr. Michael Fetters CC BY-SADoes it matter if a baby sign is iconic or arbitrary? Research suggests that it does. Babies tend to learn iconic signs more readily than arbitrary ones (Thompson et al 2012; Caselli and Pyers 2020).

Teaching a baby to communicate using gestures can be exciting and fun. It’s an opportunity to watch your baby think and learn. The process might encourage you to pay closer attention to your baby’s attempts to communicate. It might help you appreciate the challenges your baby faces when trying to decipher language.

These are good things, and for some parents, they are reason enough to try baby signing. But what about other reasons — developmental reasons?

You’ll find many enthuastic claims online (Nelson et al 2012). Some advocates believe that baby signing programs have long-term cognitive benefits. They’ve speculated that babies taught to sign will amass larger spoken vocabularies, and even develop higher IQs.

Others have claimed that signing has important emotional benefits. They maintain that young babies may learn signs more easily than they learn spoken words, leading them to communicate more effectively at an earlier age. As a result, these infants end up experience less frustration and few temper tantrums.

Does the research support these claims? Not exactly. But it depends on what you mean by baby-signing. If you mean “teaching babies a few, arbitrary signs as a supplement to spoken language” then there’s no compelling evidence of long-term advantages. But if you’re thinking of the more spontaneous, pantomime use of gesture, that’s a different story. There is reason to think that easy-to-decipher, iconic gesturing can help babies learn. To see what I mean, let’s take a closer look at the research.

Do baby signing programs boost long-term cognitive skills?

Overall, the evidence is lacking. The very first studies hinted that baby sign language training could be at least somewhat advantageous, but only for a brief time period (Acredolo and Goodwyn 1988; Goodwyn et al 2000).

In these studies, Linda Acredolo and Susan Goodwyn instructed parents to use signs with their infants. Then the researchers tracked the children across 6 time points, up to the age of 36 months. When the children’s language skills were tested at each time point, the researchers found that babies taught signs were sometimes a bit more advanced than babies in a control group. For instance, the signing children seemed to possess larger receptive vocabularies. They recognized more words.

When the children’s language skills were tested at each time point, the researchers found that babies taught signs were sometimes a bit more advanced than babies in a control group. For instance, the signing children seemed to possess larger receptive vocabularies. They recognized more words.

But the effect was weak, and detected only for a couple of time points during the middle of the study. For the last two time points, when babies were 30 months and 36 months old, there were no statistically significant differences between groups (Goodwyn et al 2000). In other words, there was no evidence that babies benefited in a lasting way.

And subsequent studies — using stringent controls — have also failed to find any long-term vocabulary advantage for babies taught to sign (Johnston et al 2005; Kirk et al 2012; Fitzpatrick et al 2014; Seal and DePaolis 2014).

For example, Elizabeth Kirk and her colleagues (2012) randomly assigned 20 mothers to supplement their speech with symbolic gestures of baby sign language. The babies were tracked from 8 months to 20 months of age, and showed no linguistic benefits compared to babies in a control group.

The babies were tracked from 8 months to 20 months of age, and showed no linguistic benefits compared to babies in a control group.

And what about IQ? Although some advocates have claimed that baby sign language training boosts a child’s IQ, the relevant research has yet to appear in any peer-reviewed journal. On this question, it’s safe to say that the jury is still out.

This is an interesting idea, and it’s been championed by advocates of baby signing programs. The proposal is that babies are capable of communicating via sign language months before they are ready to communicate with spoken language. Is there compelling scientific evidence for this claim? Once again, the answer is no.

The best evidence available on the question comes from a few, small studies of children raised to sign from birth. For example, two of the most relevant studies feature samples of fewer than a dozen children for a given age range. In these studies, the average timing of first signed words appears to be a bit earlier than the average timing observed for children learning spoken language.

But there is big problem. The sample sizes are just too small to draw any firm conclusions. For example, one long-term study (tracking the same babies from an early age) featured only 11 infants (Bonvillian et al 1983). Another study relies on data collected from only a few individuals each age group — for instance, just five individuals between the ages of 12 and 13 months (Anderson and Reilly 2002). When researchers rely on such small samples, we run a high risk of getting results that are skewed: It’s relatively easy to end up with a group of individuals who aren’t representative of the population as a whole.

And this is especially true when there is a lot of individual variation, as is the case for the timing of language production. For instance, at 13 months of age, it’s normal for some children to produce as few as 4 words, while others might produce many, many more. What if — by chance — your small sample includes mostly early bloomers? Or late bloomers?

Finally, there are methodological problems to be solved. We need to make sure we use similar standards when we count signs and spoken words, and different studies aren’t always comparable in this respect. So we still have a long way to go before we can answer this question. Read more about it in this Parenting Science article.

We need to make sure we use similar standards when we count signs and spoken words, and different studies aren’t always comparable in this respect. So we still have a long way to go before we can answer this question. Read more about it in this Parenting Science article.

I think that’s very likely. For example, the ASL sign for “spider” looks a lot like a spider. It’s iconic, which may make it easier for babies to decipher. And it might be easier for babies to produce the gesture than to speak the English word, “spider,” which includes tricky elements, like the blended consonant “sp.” The same might be said for the ASL signs for “elephant” and “deer.”

But most ASL signs aren’t iconic, and, as I explain here, some gestures can be pretty difficult for babies to reproduce — just as some spoken words can be difficult to pronounce. So it’s unlikely that a baby is going to find one mode of communication (signing or speaking) easier across the board.

Individual families might experience benefits. But without controlled studies, it’s hard to know if it’s really learning to sign that makes the difference. To date, claims about stress aren’t well-supported. One study found that parents enrolled in a signing course felt less stressed afterwards, but this study didn’t measure parents’ stress levels before the study began, so we can’t draw conclusions (Góngora and Farkas 2009).

But without controlled studies, it’s hard to know if it’s really learning to sign that makes the difference. To date, claims about stress aren’t well-supported. One study found that parents enrolled in a signing course felt less stressed afterwards, but this study didn’t measure parents’ stress levels before the study began, so we can’t draw conclusions (Góngora and Farkas 2009).

Nevertheless, there are hints that signing may help some parents become more attuned to what their babies are thinking.

In the study led by Elizabeth Kirk, the researchers found that mothers who had been instructed to use baby signs behaved differently than mothers in the control group. The signing mothers tended to be more responsive to their babies’ nonverbal cues, and they were more likely to encourage independent exploration (Kirk et al 2012).

So perhaps baby signing encourages parents to pay extra attention when they communicate. Because they are consciously trying to teach signs, they are more likely to scrutinize their babies’ nonverbal signals.

As a result, some parents might become better baby “mind-readers” than they might otherwise have been, and that’s a good thing. Being tuned into your baby’s thoughts and feelings helps your baby learn faster.

But of course parents don’t need to participate in a baby sign language program to achieve these effects. The important thing is tuning into your baby, and figuring out what he or she wants. And this begs the question: Does teaching your baby signs (from ASL or other languages) necessarily give you more insight into what your baby wants?

Families can communicate quite successfully

without using formal “baby signs”© 2012 Regents of the University of Michigan, courtesy Dr. Michael Fetters CC BY-SAFor example, consider the sign for “more,” borrowed from ASL. You bring your fingers and thumb together on each hand, and then tap your hands together by the fingertips. It’s a perfectly useful sign, and many babies have learned it. But what happens if you don’t teach your baby this sign?

Will your baby be incapable of letting you know that he wants more applesauce? Will your baby somehow fail to get across the message that she wants to play another round of peek-a-boo?

When parents pay attention to their babies — and engage them in conversation, one-on-one — they learn to read their babies’ cues. A baby might pat the table when he wants more applesauce. A baby might reach out and smile when she wants to play with you. They aren’t signs borrowed from a language like ASL, but, in context, their meaning is clear. When we respond appropriately to these spontaneous gestures, we are engaged in successful communication, and we are helping our babies build the social skills they need to master language.

A baby might pat the table when he wants more applesauce. A baby might reach out and smile when she wants to play with you. They aren’t signs borrowed from a language like ASL, but, in context, their meaning is clear. When we respond appropriately to these spontaneous gestures, we are engaged in successful communication, and we are helping our babies build the social skills they need to master language.

That doesn’t mean there is no reason to teach formal signs. You might find that some signs are helpful — that they allow for communication that is otherwise difficult for your baby. But it’s wrong to think of formal signs as the only gestures that matter. From the very beginnings of humanity, parents and babies have communicated by gesture. And research suggests that gestures matter. A lot!

In fact, this is so important, it’s worth considering in more detail. Whether or not you decide to teach your baby sign language, you should embrace the use of gestures when you communicate.

Why everyday gestures can have a big impact on your baby’s development

Our nonverbal cues can help babies learn language

Imagine I stranded you in the middle of a remote, isolated nation. You don’t speak the local language, and the locals don’t recognize any of your words. What would you do? Very quickly, you’d resort to pantomime. And as you tried to learn the language, you’d soon appreciate that some people are a lot more helpful than others.

It isn’t just that they’re friendlier. Some people just seem to have a better knack for non-verbal cues. They follow your gaze, and comment on what you’re looking at. They point at the things they are talking about. They use their hands and facial expressions to act out some of the things they are trying to say. And they’re really good at it. When they talk, it’s easier to figure out what they mean.

Researchers call this ability “referential transparency,” and it helps babies as well as adults. The evidence? Erica Cartmill and her colleagues (2013) made video recordings of real-life conversations between 50 parents and their infants – first when the babies were 14 months old, and again when they are 18 months old. Then, for each parent-child pair, the researchers selected brief vignettes – verbal interactions where the parent was using a concrete noun (like the word “ball”).

Then, for each parent-child pair, the researchers selected brief vignettes – verbal interactions where the parent was using a concrete noun (like the word “ball”).

The researchers muted the soundtrack of each vignette, and inserted a beeping noise every time the parent uttered the target word. Next, they showed the resulting video clips to more than 200 adult volunteers. They asked the volunteers to guess what the parents were talking about. When you hear the beep, what word do you think the parent is saying?

The researchers were pretty tough graders. They didn’t, for example, count guesses as correct if they were too general (like guessing “toy” when the correct answer was “teddy bear”). Nor did they give volunteers credit for guesses that were too specific (guessing “finger” when the correct answer was “hand”). They also tried to eliminate vignettes where it was possible for volunteers to read the parents’ lips.

So the test wasn’t easy, and it might give us an idea of how challenging it is for babies to decipher unfamiliar words. The outcome? It turns out there was a lot of variation between parents. Some parents spoke with referential transparency only 5% of the time. Others were more like expert foreign language teachers, making their meanings clear up to 38% of the time.

The outcome? It turns out there was a lot of variation between parents. Some parents spoke with referential transparency only 5% of the time. Others were more like expert foreign language teachers, making their meanings clear up to 38% of the time.

And — here’s the part with implications for the long-term — there were links between a parent’s referential transparency score and her child’s vocabulary three years later. Babies who had more “transparent” parents tested with larger vocabularies when they were four and half years old.

The link remained significant even after controlling for the babies’ vocabularies at the beginning of the study. And there were other interesting points too. Although the sheer number of works spoken by parents predicted a child’s vocabulary, it was high-quality, transparent communication that mattered most. And while researchers replicated a well-known finding – that parents of higher socioeconomic status (SES) use more words with their kids – there were no links between SES and referential transparency. Parents of high SES were no more likely than other parents to speak to their babies in a highly transparent way.

Parents of high SES were no more likely than other parents to speak to their babies in a highly transparent way.

What do we make of these results? We can’t be sure that referential transparency caused larger vocabularies. Maybe parents who scored high on referential transparency did so because they possessed a heritable trait – one they passed on to their kids – that makes people both better communicators and better verbal learners.

But remember: Parents with high referential transparency were easier for adult volunteers to understand, and these adults were unrelated to the parents. So it isn’t hard to imagine how referential transparency could lead to long-term language gains. And other research suggests that we can help our babies by being responsive to our babies’ spontaneous gestures. For example, consider the importance of pointing.

Babies learn words faster when we label the things they point at

Most babies begin pointing between 9 and 12 months, and this can mark a major breakthrough in communication. By pointing, babies can make requests (e.g., “Give me that toy”). They can also ask questions (“What is that?”) and make comments (“Look at that!”).

By pointing, babies can make requests (e.g., “Give me that toy”). They can also ask questions (“What is that?”) and make comments (“Look at that!”).

But the impact of this communicative breakthrough depends on our own behavior. Are we paying attention? Do we respond appropriately? As psychologists Jana Iverson and Susan Goldin-Meadow have noted, a baby who points at a new object might prompt her parent to label and describe the object. If the parent responds this way, the baby gets information at just the right moment—when she is curious and attentive. And that could have big implications for learning (Iverson and Goldin-Meadow 2005).

Experiments have confirmed the effect: Babies are quicker to learn the name of an object if they initiate a “lesson” by pointing. And if the adult tries to initiate — by labeling an object that the baby didn’t point at? Then there is no special learning effect (Lucca et al 2018).

So there’s good reason to think that gestures affect learning. But the trick is to emphasize easy-to-decipher gestures.

But the trick is to emphasize easy-to-decipher gestures.We want to be like that those language tutors in the remote, far-off country – the ones who respond to other people’s requests for information, and who have a knack for supplementing speech with easy-to-understand pantomime.

Does this mean that abstract, non-iconic signs pose a problem? Can baby sign language

delay speech development?That’s a reasonable question, given that baby signing programs feature signs that are non-iconic. Could the difficulty of learning such signs be a roadblock?

Studies haven’t found that babies trained to use signs suffer any disadvantages. So if you and your baby enjoy learning and using signs, you shouldn’t worry that you’re putting your baby at risk for a speech delay. In essence, you’re just teaching your baby extra vocabulary — vocabulary borrowed from a second language.

Still, it’s helpful to remember that iconic gestures are easier for your baby to figure out. For example, in one experimental study, 15-month-old toddlers were relatively quick to learn the name of a new object when the adults gestured in an illustrative, pantomime-like way. The toddlers were less likely to learn the name for an object when the spoken word was paired with an arbitrary (non-representational) gesture (Puccini and Liszkowski 2012).

For example, in one experimental study, 15-month-old toddlers were relatively quick to learn the name of a new object when the adults gestured in an illustrative, pantomime-like way. The toddlers were less likely to learn the name for an object when the spoken word was paired with an arbitrary (non-representational) gesture (Puccini and Liszkowski 2012).

What’s the takeaway?

Non-verbal communication is crucial for language development. Gestures can provide babies with important information, and help them decipher your meaning. But not all gestures are equally helpful. Research suggests that the most effective approach is

- to pay attention to our babies, and respond appropriately to their spontaneous attempts to gesture and verbalize; and

- to communicate with babies using a combination of speech and transparent getures — like pantomime and pointing.

In addition, I suspect it’s beneficial to build on those signs and gestures that you and your baby spontaneously invent. They already have meaning to your baby, and they are probably easier for your baby to remember.

They already have meaning to your baby, and they are probably easier for your baby to remember.

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t also teach your baby sign language, including some arbitrary, non-iconic signs. It can be fun and interesting, and your child might end up learning signs that are very useful. But to help your baby learn, it makes sense to emphasize gestures that are easy to decipher, and which have personal meaning to your baby.

Whether you opt for the spontaneous, do-it-yourself approach, or you want to teach your baby gestures derived from real sign languages, keep the following tips in mind.

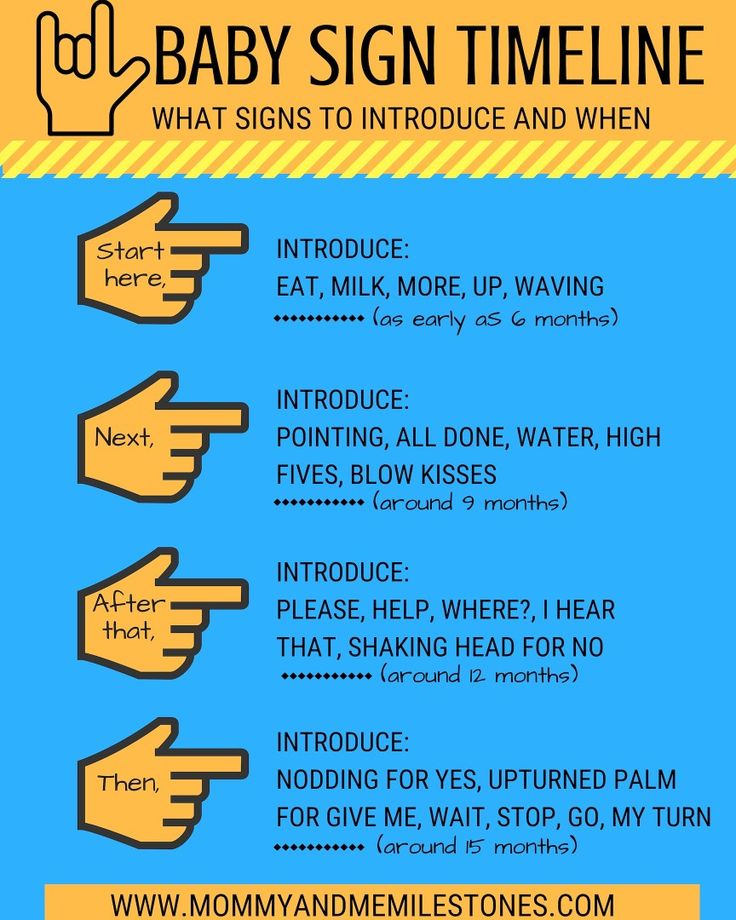

How early can you start introducing your baby to signs? As early as you like, but remember that it will take time for your baby to learn how to make signs.Babies with developmentally normal hearing begin learning about language from the very beginning. They overhear their mothers’ voices in the womb, and they are capable of recognizing their mother’s native language – distinguishing it from a foreign language – at birth. Over the following months, their brains sort through all the language they encounter, and they start to crack the code. And by the time they are 6 months old, babies show an understanding of many everyday words – like “mama,” “bottle,” and “nose.”

Over the following months, their brains sort through all the language they encounter, and they start to crack the code. And by the time they are 6 months old, babies show an understanding of many everyday words – like “mama,” “bottle,” and “nose.”

Many babies this age are also beginning to babble – repeating speech syllables like “ma ma ma” and “ba ba ba.” If a 6-month-old baby says “ba ba” after you give her a bottle, could it be that she’s trying to say the word “bottle”? If an infant sees his mother and says “mama,” is he calling her by name? It’s possible. And as noted above, research suggests that many babies are speaking their first words by the age of 10 months. (Read more about it in my article, “When do babies speak their first words?”)

So we might expect that babies are ready to observe and learn about signs at an early age — even before they are 6 months old. In support of this idea, a recent experimental study found evidence that babies as young as 4 months paid close attention to a signing adult. They watched as a native user of ASL signed to them, and looked back and forth between her signs and the object she was discussing (Novack et al 2022). Does this mean that 4 month old babies are ready to produce signs themselves? No. But it suggests we can help them learn about the meaning of signs, and that is a crucial part of language development.

They watched as a native user of ASL signed to them, and looked back and forth between her signs and the object she was discussing (Novack et al 2022). Does this mean that 4 month old babies are ready to produce signs themselves? No. But it suggests we can help them learn about the meaning of signs, and that is a crucial part of language development.

Babies learn words and signs by being repeatedly exposed to them, and by using them in real conversations. So let your signs come up naturally, and avoid turning these episodes into parent-driven lessons. Remember the experiments about pointing. Babies learn when they’re the ones who initiate.

Keep in mind that it’s normal for babies to be less than competent. Don’t pretend you can’t understand your baby just because his or her signs don’t match the model!Just a baby’s first attempt to say “bottle” falls short (“ba ba,”) his or her early attempts to gesture will likely be less than perfect. Baby sign language instructors call these attempts “sign approximations,” and they recommend that you run with them. In some cases, your baby might lack the fine motor skills to form the correct version of the sign.

Baby sign language instructors call these attempts “sign approximations,” and they recommend that you run with them. In some cases, your baby might lack the fine motor skills to form the correct version of the sign.

Pretending that your baby didn’t really communicate effectively to you — because your baby’s gesture isn’t exactly what you want — is counterproductive. Don’t forget: Babies develop better language skills when their parents are tuned in and helpful!

More reading

You can read more about the timing of signing and speaking in this article. I review the evidence, and address misconceptions about baby sign language.

For more information about communicating with babies, see my review of fascinating research about the effects of eye contact on infants. It discusses how shared gaze primes your baby’s brain for communication and language-learning.

In addition, see this Parenting Science article about how certain aspects of infant-directed speech help babies learn language.

Interested in gesture? You should be! Research suggests that gesture does more than help babies learn language. It can also help kids grasp mathematical concepts, and more. Read about it in my article, “The Science of gestures.”

Acredolo, LP and Goodwyn SW. 1988. Symbolic gesturing in normal infants. Child Development 59: 450-466.

Acredolo L and Goodwyn S. 1998. Baby Signs. Chicago: Contemporary Books.

Anderson D and Reilly J. 2002. The MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory: Normative data for American Sign Language. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 7: 83–106

Bonvillian JD, Orlansky MD, Novack LL. 1983. Developmental milestones: sign language acquisition and motor development. Child Dev. 54(6):1435-45.

Cartmill EA, Armstrong BF 3rd, Gleitman LR, Goldin-Meadow S, Medina TN, Trueswell JC. 2013. Quality of early parent input predicts child vocabulary 3 years later. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(28):11278-83.

Crais E, Douglas DD, and Campbell CC. 2004. The intersection of the development of gestures and intentionality. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 47(3):678-94.

2004. The intersection of the development of gestures and intentionality. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 47(3):678-94.

Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E, Thal DJ, Pethick SJ. 1994. Variability in early communicative development. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 59(5):1-173.

Fitzpatrick EM, Thibert J, Grandpierre V, and Johnston JC. 2014. How handy are baby signs? A systematic review of the impact of gestural communication on typically developing, hearing infants under the age of 36 months. First Language. 34 (6): 486–509.

Goodwyn SW, Acredolo LP, and Brown C. 2000. Impact of symbolic gesturing on early language development. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 24: 81-103.

Howard L and Doherty-Sneddon G. 2014. How HANDy are baby signs? A commentary on a systematic review of the impact of gestural communication on typically developing, hearing infants under the age of 36 months. First Language 34(6):510-515

Iverson JM and Goldin-Meadow S. 2005. Gesture paves the way for language development. Psychological Science 16(5): 367-371.

Psychological Science 16(5): 367-371.

Iverson, J.M., Capirci, O., Volterra, V., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (in press). Learning to talk in a gesture-rich world: Early communication of Italian vs. American children. First Language.

Johnston JC, Durieux-Smith A and Bloom K. 2005. Teaching gestural signs to infants to advance child development: A review of the evidence. First Language 25(2): 235-251.

Kirk E, Howlett N, Pine KJ, Fletcher BC. 2013. To Sign or Not to Sign? The Impact of Encouraging Infants to Gesture on Infant Language and Maternal Mind-Mindedness. Child Dev. 84(2):574-90.

Lucca K and Wilbourn MP. 2018. Communicating to Learn: Infants’ Pointing Gestures Result in Optimal Learning. Child Dev. 89(3):941-960.

Mayor J and Plunkett K. 2011. A statistical estimate of infant and toddler vocabulary size from CDI analysis. Developmental Science 14(4): 769-85.

Meins E, Fernyhough C, Fradley E, and Tuckey M. 2001. Rethinking maternal sensitivity: Mothers’ comments on infants’ mental processes predict security of attachment at 12 months. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Discipline 42: 637-648.

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Discipline 42: 637-648.

Meyer RP. 2016. Sign language acquisition. Oxford Handbooks Online. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935345.013.19.

Nelson LH, White KR, and Grewe J. 2012. Evidence for website claims about the benefits of teaching sign language to infants and toddlers with normal hearing. Infant and Child Development 21(5): 474-502.

Novack MA, Chan D, and Waxman S. 2022. I See What You Are Saying: Hearing Infants’ Visual Attention and Social Engagement in Response to Spoken and Sign Language. Front Psychol. 13:896049.

Oller DK. 2000. The emergence of the speech capacity. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Petitto LA. 1988. “Language” in the prelinguistic child. In F. S. Kessel (ed.), The development of language and language researchers: Essays in honor of Roger Brown (pp. 187–221). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Petitto LA and Marentette PF. 1991. Babbling in the manual mode: Evidence for the ontogeny of language. Science 251: 1493-1496.

Science 251: 1493-1496.

Puccini D and Liszkowski U. 2012. 15-Month-Old Infants Fast Map Words but Not Representational Gestures of Multimodal Labels. Front Psychol. 2012;3:101. Epub 2012 Apr 3.

Seal BC and DePaolis RA. 2014. Manual Activity and Onset of First Words in Babies Exposed and Not Exposed to Baby Signing. Sign Language Studies 14(4): 444-465.

Thompson R, Vinson DP, Woll B, and Vigliocco G. 2012. The road to language learning is iconic: Evidence from British Sign Language. Psychological Science 23: 1443–1448

image of mother holding gesturing infant by fizkes / shutterstock

image of baby girl clapping cropped from photo by istock / TakakoWatanabe

image of baby sitting on father’s lap by Drazen Zigic / shutterstock

Drawings of baby signs are © 2012 Regents of the University of Michigan. They appear courtesy Dr. Michael Fetters (PDF hereopens PDF file ), and are shared via the Creative Commons license BY-SA

Portions of this text derive from earlier, published versions of the article, written by the same author (Gwen Dewar). In addition, some of the sentences about Cartmill’s study originally appeared in blog post written by Gwen Dewar for BabyCenter.

In addition, some of the sentences about Cartmill’s study originally appeared in blog post written by Gwen Dewar for BabyCenter.

Content last modified 8/2022

International Day of the Deaf - RIA Novosti, 03.03.2020

Every year, the last full week of September is celebrated as the International Week of the Deaf, which ends with the International Day of the Deaf, celebrated on Sunday. In 2017, this day falls on September 24th.

International Day of the Deaf was established in 1958 to commemorate the creation in September 1951 of the World Federation of the Deaf, which is one of the oldest international organizations for people with disabilities. Currently, the World Federation of the Deaf (WFD) unites 133 national organizations from all five continents.

The World Federation of the Deaf is one of the world's leading organizations dedicated to addressing the issue of equal rights for deaf and hearing people.

According to WHO, more than 5% of the world's population—360 million people (328 million adults and 32 million children)—suffer from disabling hearing loss (hearing loss in the better ear of more than 40 dB in adults and 30 dB in children). ). Most of these people live in low- and middle-income countries.

). Most of these people live in low- and middle-income countries.

Approximately one in three people over the age of 65 suffer from disabling hearing loss. The highest prevalence of this condition in this age group is found in South Asia, Pacific Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Hearing loss can be mild, moderate, severe or profound. It can develop in one or both ears and lead to difficulty hearing spoken language or loud sounds.

"Hearing loss" refers to people with hearing loss ranging from mild to severe. They usually communicate using spoken language and may use hearing aids, cochlear implants (a prosthesis that compensates for hearing loss), and other aids, as well as subtitles, to improve their hearing.

"Deaf" people generally suffer from profound hearing loss, in which they hear very little or no hearing at all. Often such people use sign language to communicate.

Hearing loss can develop due to genetic causes, as complications during childbirth, and as a result of certain infectious diseases, chronic ear infections, the use of certain drugs, exposure to excessive noise and aging.

There are more than 13 million hearing impaired people in Russia, including more than 1 million children.

According to the All-Russian Society of the Deaf, there are more than 300,000 deaf people who speak sign language. These statistics included those who lost their hearing completely or partially at an early age or with congenital hearing defects.

Famous people who lost their hearing at various ages include Renaissance poet Pierre de Ronsard, composer Ludwig van Beethoven, writers Victor Hugo, Jean Jacques Rousseau and Karel Capek; Italian artist Antonio Stagnoli, French sculptor Claude-Andre Dessen and others.

But no one who does not have hearing considers himself mute - the deaf have a sign language that is as full and rich as the language of verbal communication. The first school for deaf people, the Paris Institute of the Deaf and Dumb, was founded in 1760 in France by Abbé de L'Epe.

In Russia, the first school for deaf children was opened in 1806 in Pavlovsk. In 1900, the first kindergarten in Europe for the deaf was opened in Moscow. At the beginning of the 20th century, institutions for children with hearing, vision or developmental problems were only a few. Early 19In the 1930s, a system of special education began to take shape in Russia. In the mid-1990s, there were 84 schools for the deaf in Russia. In recent years, the number of special institutions has increased, and the qualifications of teachers have increased.

In 1900, the first kindergarten in Europe for the deaf was opened in Moscow. At the beginning of the 20th century, institutions for children with hearing, vision or developmental problems were only a few. Early 19In the 1930s, a system of special education began to take shape in Russia. In the mid-1990s, there were 84 schools for the deaf in Russia. In recent years, the number of special institutions has increased, and the qualifications of teachers have increased.

In 2012, the status of sign language was legally approved in Russia. On December 30, 2012, Russian President Vladimir Putin approved amendments to the law on the social protection of disabled people, which clarified the status of Russian sign language and defined it as the language of communication in the presence of hearing and (or) speech impairments. According to the law, special textbooks, teaching aids, other educational literature, as well as the services of sign language interpreters, must be provided free of charge to deaf people when receiving education.

Currently, preschool and secondary educational institutions for children with hearing impairments operate in many regions of the Russian Federation; in a number of regions there are secondary specialized and higher educational institutions where children with hearing impairments can continue their education.

In Moscow, these universities include Moscow State University of Medicine and Dentistry, Russian State Social University, Moscow State Pedagogical University, Moscow State Technical University. N.E. Bauman, Russian State University for the Humanities, Moscow State University of Psychology and Education, Moscow State University of Technology and Management named after K.G. Razumovsky.

On International Day of the Deaf, the WFH recommends and encourages all associations of the deaf to campaign to raise the awareness of politicians, authorities, the media and the public about the problems of people with hearing impairments.

The material was prepared on the basis of information from RIA Novosti and open sources

Where and how sign language interpreters work

Maria Gureeva

Author

Share

People in my profession are called sign language interpreters, but the correct name is Russian sign language interpreters (RSL).

How furniture restorers work

The most important thing is to save the item from destruction

Tatyana Andreeva

RSL translator

Initially, I did not plan to become a RSL translator. After graduating from school, she received the specialty of an accountant, worked in her profession for five years; then there was an economic education. I learned about sign language by accident, but I was very interested in this topic: what it is, how to communicate in it, how you can understand each other, is it really a full-fledged language, and not just some separate gestures.

I went to the usual three-month courses. This is not a full-fledged education, but an optional one. In the classroom, there is an acquaintance with the language, the rules of communication in it, there is direct practice - communication with the deaf. I was drawn into this world, and the teacher was very supportive, who said that I was doing great and, if I like it, I should get a diploma as a translator of RSL. So I began to study further and mastered a new profession.

So I began to study further and mastered a new profession.

Interestingly, after 2012, Russian Sign Language is considered to be the language of communication recognized in our country (296-FZ of December 30, 2012).

How to become a certified RSL translator

To become a RSL translator and be able to work, you need to graduate from either a college or a university. I studied in St. Petersburg at the Interregional Center for the Rehabilitation of People with Hearing Problems (college). Higher education can be obtained at specialized institutes in Moscow and Novosibirsk.

About unified sign language

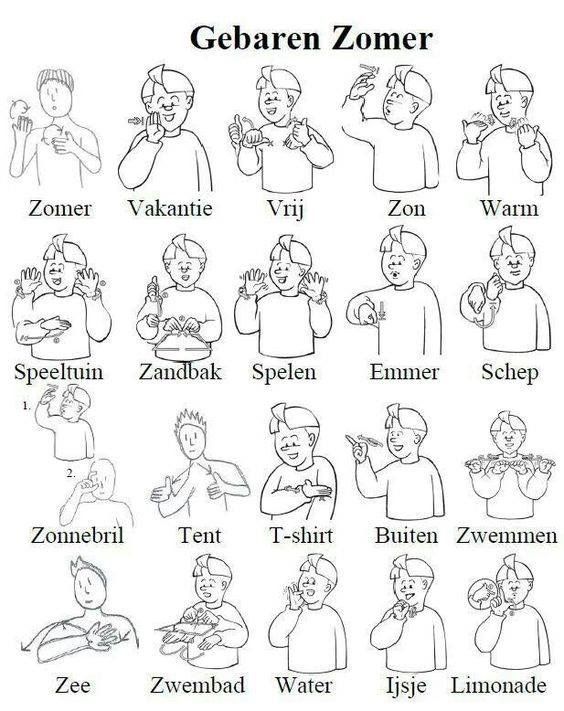

There is a word “Russian” in the name of my profession. It is not there by accident. A foreign sign language is different, but an international sign language has not yet been invented, although there have been attempts, even a name has been invented: gestuno. Nevertheless, there are about 300 gestures that are the same in different languages. For example, the gesture "home" is repeated almost everywhere.

For example, the gesture "home" is repeated almost everywhere.

The difficulty is that sign language is based on the alphabet (dactyl), which can be one-handed or two-handed. In Russia, we show our 33 letters with one, right hand. In England, the letters are shown with two hands.

Features of sign language

Sign language consists of two parts: the alphabet and gestures. It is not always possible to use gestures to translate any sentence or phrase that a hearing person says. If it's a name, a name, a compound word that doesn't have a gesture, I dactylize what I heard - I spell it out with my hand.

By the way, unlike letters, many gestures are shown with two hands. It is also interesting that sign language is not a copy of the Russian language. Sometimes - yes, a specific gesture means a specific word. But it also happens that one gesture can reproduce a whole sentence.

“With 100 thousand donated for the wedding, I bought a set of tools”

Jeweler, author of jewelry-statements

Features of deaf people

Deaf people are essentially foreigners. They live in our country without their own flag, nationality, but with their own language. They have their own humor. Very funny but special. So, when translating a joke into Russian, its “salt” is often lost. The deaf also have their own vocabulary and even swearing. Yes, some swear words are taken from the Russian language, but there are many that exist only in RSL.

They live in our country without their own flag, nationality, but with their own language. They have their own humor. Very funny but special. So, when translating a joke into Russian, its “salt” is often lost. The deaf also have their own vocabulary and even swearing. Yes, some swear words are taken from the Russian language, but there are many that exist only in RSL.

The written Russian language is a second language for the deaf (the native language is RZhL, where even sentences are built differently). That is, such people can be safely called bilinguals. The feeling of the Russian language in a deaf person depends on when he lost his hearing (was born like this, or, for example, it happened already in adulthood), he is deaf or hard of hearing. Everywhere has its own nuances.

Qualities required for a translator of RSL

The profession of a translator of RSL is necessary and in demand, but, according to statistics, few remain in it. So, on my course in college there were 20 people. Only two of them work as RSL translators. The features of the activity are indicated.

So, on my course in college there were 20 people. Only two of them work as RSL translators. The features of the activity are indicated.

First, you need to love people. Secondly, you need to love to communicate. Although there are many deaf people, they do not have a very large social circle. So, when a RSL interpreter or a person who knows sign language appears nearby, they, as a rule, are always happy to make contact and communicate a lot. These features must be taken into account: I think it will be difficult for an introvert in our profession.

It is important to understand that deaf people are people with disabilities. But this does not mean that those who hear are somehow higher or better than them. We are equal, we just speak different languages. If the RSL translator has such a position, then everything will be fine.

A broad outlook, a desire to learn will also serve their purpose: things that you have an idea about are translated much easier. I believe that there is never a lot of knowledge, so self-development is a necessary skill.

In my educational institution, in addition to RSL, we were taught legal law — they told us what rights people with disabilities have in our country, what rights and obligations an interpreter has. There were lectures on the structure of the ear (it is important to know what residual hearing is, how the deaf differ from the hearing impaired), on the psychology of the deaf (you need to understand why they are different and how different they are). They also taught the history of RSL. This is a young language: even before the 19th century, the deaf, unfortunately, were considered mentally retarded and were not taught at all. It was a big disaster, and I am very glad that a lot is being done in the field of adaptability of the deaf in society.

But, even despite the completed courses, college or institute, the RSL translator continues to study all his life. Something becomes obsolete, new gestures, new words appear. So, the coronavirus came - his gesture was formed in RSL. In addition, it is good to replenish your knowledge about the deaf, their psychology, since a language does not live without an environment: it is determined by those who speak it.

In the work of a translator of RSL, additional education also helps, because often we are needed not only at private meetings, but also at various events, in educational institutions, in courts. Therefore, if the translator has an economic or legal education, this is always a plus. This means that in the same court he will understand what he is saying and will not make a mistake in translation, which for someone may be fatal.

Tales from editors, stories that got us hooked, useful and useless messages - "lightning" - all in the telegram channel "Prosto Raboty". Only you are missing.

Read

How an RSL translator should look like

It seems that when a RSL translator works, all the attention of the audience is directed only to his hands. Actually it is not. RSL unites everything: both gestures, and how the body moves, what facial expressions and articulation are, how we speak and what we say.

There are general rules for how interpreters should dress. So, preference is given to dark clothing, so that hands can be clearly seen against its background. There should be no bright make-up, clothes, manicure (saturated color distracts attention; it is hard to look at it for a long time), long earrings. The latter are simply unsafe: many gestures are broadcast near the face, so with a quick translation, there is a chance of hurting them and getting hurt.

Where can an RSL translator work? I come to lectures at groups where there are deaf students, and I translate what the teacher says during the class. Such students study in ordinary groups, with hearing classmates.

So far, this practice is present only in some cities of Russia - primarily where they train RSL translators for the profession (Moscow, Novosibirsk, St. Petersburg). So the choice of educational institutions for the deaf today is limited. And there are many deaf people themselves, and in many professions they even surpass the hearing ones in some ways. So, in our college, deaf boys study radio engineering. All students need to solder, and the deaf sometimes solder the boards faster, more accurately and better than the rest, because they are not distracted by extraneous conversations, they are focused and attentive.

In general, the professions where the deaf can be employed are very different: from taxi drivers, masons, carpenters, cashiers in a store, welders to radio technicians, tourism managers, jewelers, florists and even guides (excursions for deaf tourists).

My work also includes translation into RSL when deaf students communicate with the college administration and teachers. From time to time I am busy at events: both the educational institution itself and the city ones, where our students are invited.

In addition, I am engaged in tutoring - I created a group in VK and teach RSL to everyone. This is a three-month training, within which people can get acquainted with RSL and begin to communicate with the deaf, as far as their abilities and language level allow.

Another niche for RSL translators is social translations, work for the All-Russian Society of the Deaf. In this case, interpreters can accompany the deaf to clinics and banks. The services of specialists of our profession are required in the police, courts.

I work as a Kirchenmusikdirektor in Petrikirche on Nevsky Prospekt

Two centuries ago, Johann Sebastian Bach held the same position in Leipzig

Who studies RSL

Among my students there are both relatives, friends of the deaf, and just those who are interested in this language. I am very happy when parents of deaf children start teaching RSL. Then afterwards they can freely communicate with their child and avoid many problems in communication.

There were a couple of cases when RSL lessons were taken from me “on a need-to-know basis”. Now there are many mixed groups in kindergartens, where deaf, hearing-impaired or implanted (those who have a cochlear implant) kids are engaged together with normotypical ones. And several educators came to me who wanted to study RSL at their own expense in order to better understand their wards.

It happens that a course of RZhA is ordered by audiologists. They give speeches to children with hearing aids, but they also need to communicate with their deaf parents, who often do not have these hearing aids. This is where RJA comes to the rescue.

Salary

It is difficult to name the average figures for the salary of RSL translators. Much depends on the place of residence - for example, in St. Petersburg, where I studied, and in Voronezh, where I live, the spread in terms of money is large in any profession. But in our field, experience and well-established connections have a great influence. A young translator in the capital may earn less than an experienced colleague from the region. At the same time, there is no established regulation on the salaries of RSL translators, but we hope that it will appear in the near future - then it will be possible to understand what rate you can focus on.

The reputation of the RSL translator among the deaf also contributes. It may be that there are two specialists in the city, but one is constantly busy, and the other is not hired anywhere, because he does not comply with the ethics of the RSL interpreter - for example, violates the confidentiality of the information received during sign language translation.

Benefits of my job

I really like the people I translate for. I really appreciate the communication with them. They really are different: this is a different outlook on life. It is very interesting to observe how the deaf react to certain circumstances, what point of view they hold and why.

Translating into RSL in different circumstances, helping people is what I love my job for. So, for several years I have been taking part in the initiatives of the ROOI “Perspektiva”, which helps the deaf to get new professions and get a job. To see that a deaf person gets what he has in mind, how he changes while pursuing his dream, what he CAN is worth a lot. Every time it's a little miracle.

“Oh, the guard gets up early!” - an ode to office security guards

The main characters of our time

Difficulties

As often happens, where there is a plus, there is a minus. The complexity of my work is that deaf people and I are different, we perceive the world and others differently. But still more difficult moments arise in relation to the deaf of society. So, when you want to say something to a deaf person, and there is an interpreter nearby, it is incorrect to speak only with the interpreter. Like, I’ll explain everything to you now, and you will translate it for him / her. Do not do it this way. It is right to look at the deaf and speak to the deaf.