Mirtazapine and lexapro

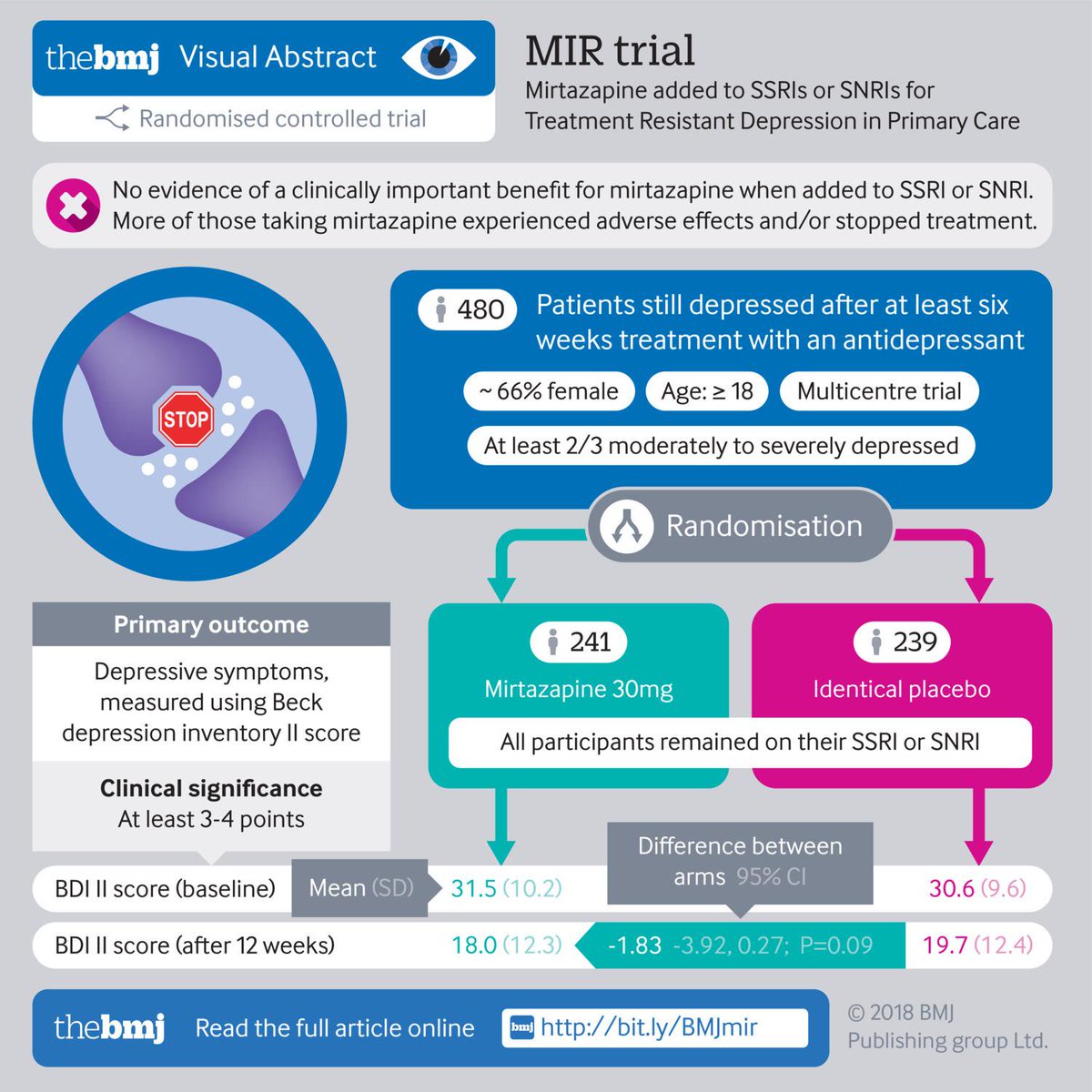

Introduction - Combining mirtazapine with SSRIs or SNRIs for treatment-resistant depression: the MIR RCT

Background

Depression is ranked among the top five contributors to the global burden of disease and by 2030 is predicted to be the leading cause of disability in high-income countries.1 In the UK, people with depression are usually managed in primary care and antidepressants are often the first-line treatment. The number of prescriptions for antidepressants has risen dramatically in recent years, increasing by 6.8% (3.9 million items) between 2014 and 2015. Indeed, antidepressants have shown a greater increase in the volume of prescribing in recent years than drugs for any other therapeutic area, with over 61 million prescriptions being issued in England in 2015, at a cost of £2685M. 2

However, the largest study of sequenced treatment for depression, the STAR*D (Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression) study,3 found that half of those treated did not experience a reduction of ≥ 50% in depressive symptoms following 12–14 weeks of treatment with a single antidepressant. The reasons for non-response include non-adherence to medication, which may be a result of intolerance. However, a substantial proportion of those who take their antidepressants in an adequate dose and for an adequate period do not experience a clinically meaningful improvement in their depressive symptoms. This can be termed treatment-resistant depression (TRD).

When first-line antidepressant treatments do not work, general practitioners (GPs) can be unsure of what to offer next. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) now advises GPs to reconsider the treatment options if there has been no response after 4–6 weeks of treatment with antidepressant medication.4 However, there is currently limited evidence to guide management.

Existing evidence on the pharmacological management of treatment-resistant depression

The current NICE guideline4 describes the following pharmacological strategies for sequencing treatments after inadequate response to the initial treatment: switching antidepressants, augmenting medication by adding a drug that is not an antidepressant and combining antidepressants. The guideline4 comments that the evidence for the benefit of switching, either within or between classes, is weak.

The guideline4 comments that the evidence for the benefit of switching, either within or between classes, is weak.

Connolly and Thase5 comment that switching antidepressants after an inadequate response is not ‘unequivocally supported by the data, although switching from a SSRI [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor] to venlafaxine or mirtazapine may offer greater benefits’. Similarly, there is very little evidence on combining two antidepressants.

The evidence for the effectiveness of augmentation with a non-antidepressant is likewise of variable quality. There is some evidence for augmentation with lithium or a thyroid hormone, but mainly in combination with tricyclic antidepressants, which are not prescribed as often today. The use of the atypical antipsychotics to augment the newer antidepressants is better supported by research,

6,7 with quetiapine (Seroquel; AstraZeneca plc, Cambridge, UK) and aripiprazole (Abilify®; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) the most promising.8 However, this combination has not, to date, been adopted with any enthusiasm in UK primary care. This may be because of a lack of experience in prescribing them for this indication as they are usually initiated in secondary care. There are also concerns about their adverse events (AEs), including sedation, metabolic syndrome and central obesity and extrapyramidal effects.9 Indeed, the current NICE guidance recommends that antidepressants should not be combined or augmented without the advice of a consultant psychiatrist.4

Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) the most promising.8 However, this combination has not, to date, been adopted with any enthusiasm in UK primary care. This may be because of a lack of experience in prescribing them for this indication as they are usually initiated in secondary care. There are also concerns about their adverse events (AEs), including sedation, metabolic syndrome and central obesity and extrapyramidal effects.9 Indeed, the current NICE guidance recommends that antidepressants should not be combined or augmented without the advice of a consultant psychiatrist.4

It is possible that GPs would consider adding a second antidepressant, rather than an atypical antipsychotic or lithium, as part of the management of TRD. They are more familiar with these drugs and their starting routines; in addition, there is less concern about their AEs and less need for monitoring. In general, stepwise combination of drug treatments is a standard part of the management of chronic diseases such as asthma and hypertension in primary care and has led to improved clinical outcomes. GPs are comfortable with this model of care and would probably readily adopt this strategy if it were found to be effective. We think that there may be an opportunity to substantially improve the treatment of people with depression in primary care by using antidepressants in combination. However, one of the reasons that this strategy has not been adopted is the lack of convincing evidence for its effectiveness, especially in the primary care setting.

GPs are comfortable with this model of care and would probably readily adopt this strategy if it were found to be effective. We think that there may be an opportunity to substantially improve the treatment of people with depression in primary care by using antidepressants in combination. However, one of the reasons that this strategy has not been adopted is the lack of convincing evidence for its effectiveness, especially in the primary care setting.

There is a pharmacological rationale for adding a second antidepressant to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) with a different and complementary mode of action. Mirtazapine, an alpha2-adrenoreceptor antagonist, increases central noradrenergic and serotonergic neurotransmission by inhibiting negative feedback from synaptic noradrenaline (NA) acting on presynaptic alpha2 autoreceptors on noradrenergic neurones and alpha2 heteroreceptors on 5-hydroxytryptaminergic (5-HT) neurones. Its mechanism of action is, therefore, different from that of both SSRIs and SNRIs, which inhibit synaptic neurotransmitter reuptake after release. Thus, treatment with mirtazapine in combination with either a SSRI or a SNRI may produce a sustained increase in both 5-HT and NA synaptic availability in terminal fields. A further property of mirtazapine not shared by SSRIs and SNRIs is its affinity for the 5-HT2C receptor, where it acts as an inverse agonist. This mechanism has been linked to specific therapeutic effects. Overall, there is the potential for a synergistic action that could enhance the clinical response compared with the response of those patients receiving only monotherapy. Mirtazapine is now off patent and relatively inexpensive.

Its mechanism of action is, therefore, different from that of both SSRIs and SNRIs, which inhibit synaptic neurotransmitter reuptake after release. Thus, treatment with mirtazapine in combination with either a SSRI or a SNRI may produce a sustained increase in both 5-HT and NA synaptic availability in terminal fields. A further property of mirtazapine not shared by SSRIs and SNRIs is its affinity for the 5-HT2C receptor, where it acts as an inverse agonist. This mechanism has been linked to specific therapeutic effects. Overall, there is the potential for a synergistic action that could enhance the clinical response compared with the response of those patients receiving only monotherapy. Mirtazapine is now off patent and relatively inexpensive.

Because of its different mechanism of action, there is an argument that switching to mirtazapine alone after SSRI treatment failure might be an effective strategy, rather than subjecting patients to the potential AE burden of a second medication. The STAR*D study compared mirtazapine with nortriptyline in a group of patients who had not responded to two consecutive antidepressant monotherapy regimes.10 The rates of remission were low for both drugs, suggesting that switching to mirtazapine monotherapy is not the most useful strategy.

The STAR*D study compared mirtazapine with nortriptyline in a group of patients who had not responded to two consecutive antidepressant monotherapy regimes.10 The rates of remission were low for both drugs, suggesting that switching to mirtazapine monotherapy is not the most useful strategy.

In spite of the potential benefit of combining mirtazapine with a SSRI, there is relatively little trial evidence to support this strategy. Carpenter et al.11 compared the addition of mirtazapine to a SSRI with placebo in a group of 26 patients who had not responded to at least 4 weeks of monotherapy. Although the sample size was very small, the results in terms of effectiveness and tolerability are encouraging,11 but more definitive evidence is required before widespread adoption of this strategy. In patients who have not failed previous treatment, Blier et al.12,13 reported that mirtazapine in combination with a SSRI gave a greater improvement than monotherapy12 and that it was well tolerated with either a SSRI or a SNRI (venlafaxine),13 with both combinations providing significantly higher remission rates than a SSRI alone. In contrast, a larger study found no benefit from combining antidepressants, including mirtazapine and venlafaxine, over SSRI monotherapy with escitalopram (Cipralex®; Lundbeck, Copenhagen, Denmark), although combined treatment had a higher side-effect burden.14

In contrast, a larger study found no benefit from combining antidepressants, including mirtazapine and venlafaxine, over SSRI monotherapy with escitalopram (Cipralex®; Lundbeck, Copenhagen, Denmark), although combined treatment had a higher side-effect burden.14

Mirtazapine treatment is, however, associated with more weight gain than SSRIs15 and, therefore, as well as assessing the efficacy of its combination with SSRIs, it is important to determine its AE burden, especially when used long term.

Defining treatment-resistant depression

Many definitions of TRD have been proposed. These definitions cover a broad spectrum, ranging from failure to respond to at least 4 weeks of antidepressant medication given at an adequate dose16 to more stringent criteria based on non-response to multiple courses of treatment.5 A number of staging systems have been proposed, including, most recently, the three-stage model suggested by Conway et al. 17 However, as the authors acknowledge, although the various models may provide guidance in defining TRD, they lack empirical support.

17 However, as the authors acknowledge, although the various models may provide guidance in defining TRD, they lack empirical support.

In this study we used a more inclusive definition of TRD, that is, patients who still met the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10),18 criteria for depression after taking a SSRI or a SNRI antidepressant at an adequate dose [based on the British National Formulary (BNF)19 and advice from psychopharmacology experts] for a minimum of 6 weeks. This definition corresponds to stage I TRD as described by Thase and Rush.20 It is directly relevant to UK primary care, given the large numbers of non-responders in primary care and the current uncertainty about what course of action to recommend for this group of patients.

Although this 6-week criterion seems a relatively short period to define treatment resistance, many of the patients who satisfy this criterion of ‘non-response’ are suffering from moderate to severe chronic depression. The baseline measures for a recent study of the effectiveness of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for TRD in primary care, CoBalT (Cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for primary care patients with treatment resistant depression: a randomised controlled trial),21 found that 59% of those recruited had been depressed for > 2 years, 70% had been prescribed their current antidepressant for > 12 months and 28% satisfied the ICD-10 criteria18 for severe depression. These data on chronicity and severity illustrate the extent of the unmet need in this population.22

The baseline measures for a recent study of the effectiveness of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for TRD in primary care, CoBalT (Cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for primary care patients with treatment resistant depression: a randomised controlled trial),21 found that 59% of those recruited had been depressed for > 2 years, 70% had been prescribed their current antidepressant for > 12 months and 28% satisfied the ICD-10 criteria18 for severe depression. These data on chronicity and severity illustrate the extent of the unmet need in this population.22

It is, therefore, important to undertake a study to investigate the effectiveness of the addition of mirtazapine to SSRIs or to SNRIs in primary care. In the UK, most depression is diagnosed and treated in primary care; this is where most antidepressants are prescribed and where most treatment resistance is encountered. The rise in antidepressant prescribing has continued at a steady rate in the UK despite the introduction of the government initiative Improving Access to Psychological Services (IAPT). Failure to adequately respond to treatment is a substantial problem and there is a need to develop the evidence base for the rational prescribing of antidepressants in primary care. An effective intervention has the potential to have a substantial impact on the health and economic burden associated with this patient group.

Failure to adequately respond to treatment is a substantial problem and there is a need to develop the evidence base for the rational prescribing of antidepressants in primary care. An effective intervention has the potential to have a substantial impact on the health and economic burden associated with this patient group.

Aims and objectives

This trial investigated whether or not combining mirtazapine with SNRI or SSRI antidepressants results in better patient outcomes and more efficient NHS care than SNRI or SSRI therapy alone in TRD. All patients who entered the trial were recruited from primary care and had TRD, defined as meeting ICD-1018 criteria for depression after at least 6 weeks of treatment with either a SSRI or a SNRI antidepressant at an adequate dose.

Our specific aims were to:

determine the effectiveness of the addition of the antidepressant mirtazapine to a SSRI or a SNRI in reducing depressive symptoms and improving quality of life (QoL) at 12 and 24 weeks and 12 months (compared with the addition of a placebo)

determine the cost-effectiveness of this intervention over 12 months

qualitatively explore patients’ views and experiences of taking either two antidepressant medications or an antidepressant and a placebo and identify patients’ reasons for completing or not completing the study, including reasons for withdrawal from the study medication

qualitatively explore GPs’ views on prescribing combined antidepressant therapy in this patient group.

Efficacy and safety of add on low-dose mirtazapine in depression

Indian J Pharmacol. 2012 Mar-Apr; 44(2): 173–177.

doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.93843

,,1,2 and 2

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Objectives:

Although antidepressant medications are effective, they have a delayed onset of effect. Mirtazapine, an atypical antidepressant is an important option for add-on therapy in major depression. There is insufficient data on mirtazapine in Indian population; hence this study was designed to study the add-on effect of low-dose mirtazapine with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in major depressive disorder (MDD) in Indian population.

Materials and Methods:

In an open, randomized study, 60 patients were divided into two groups. In Group A (n=30) patients received conventional SSRIs for 6 weeks. In Group B (n=30) patients received conventional SSRIs with low-dose mirtazapine for 6 weeks. Patients were evaluated at baseline and then at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 weeks.

Patients were evaluated at baseline and then at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 weeks.

Results:

There was significant improvement in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), Montgomery and Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS) scores (P<0.05) in both groups. Mirtazapine in low dose as add on therapy showed improvement in scores, had earlier onset of action, and more number of responders and remitters as compared to conventional treatment (P<0.05). No serious adverse event was reported in either of the groups.

Conclusion:

Low-dose mirtazapine as add-on therapy has shown better efficacy, earlier onset of action and more number of responders and remitters as compared to conventional treatment in MDD in Indian patients.

KEY WORDS: Add-on, depression, mirtazapine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

Depression is one of the leading causes of global disease burden and disability.[1] The consequences of underreporting of depression and lack of treatment for it are enormous. For instance, depression is the most important risk factor for suicide, which claims around 0.85 million lives annually, and is among the top three causes of death in young people ages 15-35.[2,3]

For instance, depression is the most important risk factor for suicide, which claims around 0.85 million lives annually, and is among the top three causes of death in young people ages 15-35.[2,3]

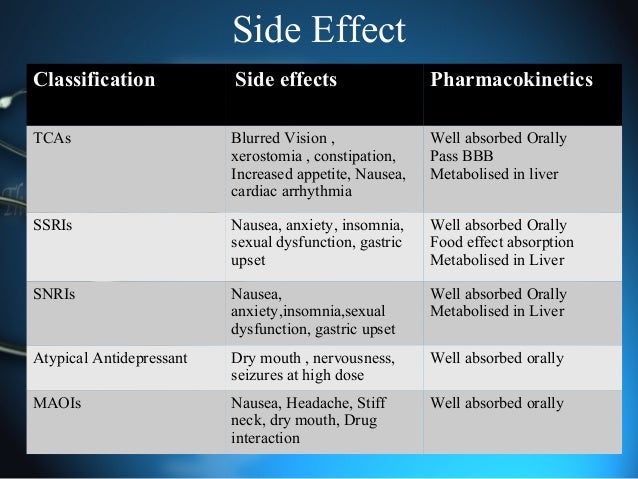

The current modalities of treatment for depression include tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). TCAs and MAOIs are not preferred these days because of their adverse effect profile and dangerous food interactions respectively. SSRIs are presently the most widely used antidepressants because of their better safety and tolerability.[4]

Many current therapies for depression provide remission in only approximately one-third of patients and few have complete resolutions.[5] These antidepressant medications also have a delayed onset of therapeutic effect. This latency is problematic in that it prolongs the impairments associated with depression, leaves patients vulnerable to an increased risk of suicide, increases the likelihood that a patient will prematurely discontinue therapy and increases medical costs associated with severe depression. [6] Thus, there is continuous search for newer novel compounds that have better efficacy or can augment the effect of conventional antidepressants in these patients.

[6] Thus, there is continuous search for newer novel compounds that have better efficacy or can augment the effect of conventional antidepressants in these patients.

Mirtazapine, an atypical antidepressant is a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NASSA) and is structural analogue of serotonin with potent antagonistic effects at several postsynaptic serotonin receptor types (including 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT3 receptors) and can produce gradual down-regulation of 5-HT2A receptors. It also limits the effectiveness of inhibitory α2 adrenergic heteroceptors on serotonergic neurons as well as inhibitory α2 autoreceptors and 5-HT2A heteroceptors on noradrenergic neurons. This effect may enhance release of amines and contribute to the antidepressant effects. Mirtazapine is also a potent histamine H1 receptor antagonist and is relatively sedating. Mirtazapine appears to be useful in patients with depression who present with anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance. Its additional beneficial effects on the symptoms of anxiety and sleep disturbance associated with depression may reduce the need for concomitant anxiolytic and hypnotic medication seen with some antidepressants. It has low potential for interaction with drugs that are metabolized by CYP2D6, including antipsychotics, TCA and some SSRIs. It is also reported to be effective for augmentation or combination therapy in patients with refractory depression.[4] This makes mirtazapine an important option for the treatment of major depression in patients who require additional therapy. A few studies reported more number of responders at an earlier time period when mirtazapine was used as add on therapy.[7,8] However, most of the studies on mirtazapine as an add on therapy have been done on a small number of patients. This study is done to evaluate the effect of low-dose mirtazapine as add on therapy with SSRIs.

Its additional beneficial effects on the symptoms of anxiety and sleep disturbance associated with depression may reduce the need for concomitant anxiolytic and hypnotic medication seen with some antidepressants. It has low potential for interaction with drugs that are metabolized by CYP2D6, including antipsychotics, TCA and some SSRIs. It is also reported to be effective for augmentation or combination therapy in patients with refractory depression.[4] This makes mirtazapine an important option for the treatment of major depression in patients who require additional therapy. A few studies reported more number of responders at an earlier time period when mirtazapine was used as add on therapy.[7,8] However, most of the studies on mirtazapine as an add on therapy have been done on a small number of patients. This study is done to evaluate the effect of low-dose mirtazapine as add on therapy with SSRIs.

Patients

This prospective, open, comparative, randomized, parallel group study was conducted in 60 patients suffering from major depressive disorder (MDD) as per ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria. [9,10] Patients were enrolled in the study after an informed written consent. Patients of both sexes between the ages of 18-75 years with Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17 items) score ≥18 were included in the study.[11] The study plan was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

[9,10] Patients were enrolled in the study after an informed written consent. Patients of both sexes between the ages of 18-75 years with Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17 items) score ≥18 were included in the study.[11] The study plan was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Newly diagnosed patients, non-responders or partial responders to the earlier prescribed antidepressants and patients not tolerating earlier prescribed antidepressants were included in the study. Patients were screened at the beginning of the study. A detailed medical and psychiatry history was obtained. Mental status and physical examination was carried out. Patients with suicidal tendencies, schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder, seizure disorder, alcohol or substance abuse, concurrent major illness or systemic dysfunction involving hepatic and renal system were excluded. Pregnant women, lactating mothers and women not using contraceptives or desiring to have children were also excluded. Patients who qualified inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled in the study.

Patients who qualified inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled in the study.

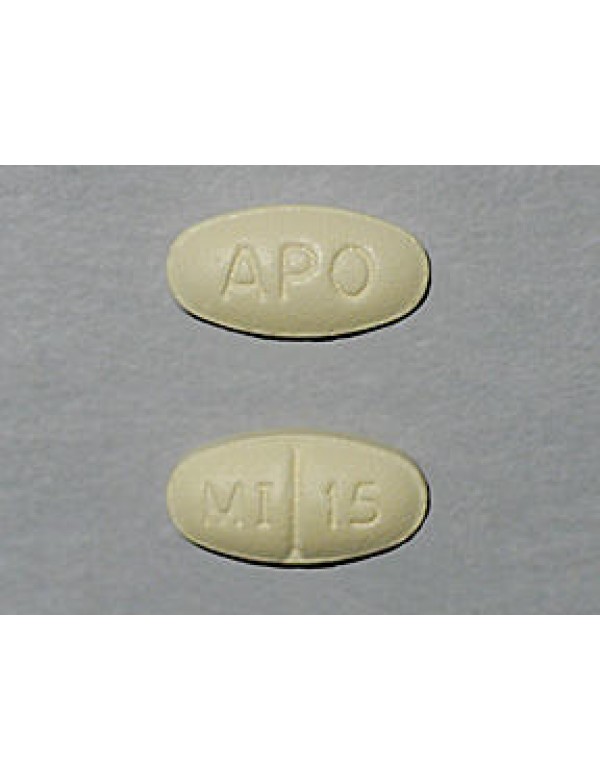

Medication

Patients were randomly divided into two groups using randomization table. Treatment in group A patients was started with SSRIs in the conventional dose range (escitalopram 10-30 mg, citalopram 20-60 mg, sertraline 50-150 mg, fluoxetine 20-40 mg, paroxetine 10-50 mg per day). Group B patients received SSRIs in the conventional dose range along with low-dose mirtazapine 7.5 mg per day. Both drugs were given either in single or divided doses based on the clinical improvement of the patient every week. Compliance was checked by pill count method. Record of concomitant medication was maintained throughout the study.

Clinical Measurement and Safety Assessment

Primary outcome measure was changes in total score of HDRS. The HDRS scale is the most commonly used scale focusing on somatic symptomatology. A 17-item version is used with score range from 0-50. A score of >8 indicates depression whereas a score of >23 means severe depression. [11] Secondary outcome measures included reduction in the score of Montgomery and Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS) and Amritsar depressive Inventory (ADI).[12,13] The MADRS score is designed to be sensitive to assess treatment effects. It has 10 items of core symptoms of depressive illness. Each item has a score range of 0-6., a score of >12 indicates depression.[12] The ADI scores are brief and effective psychological tool, easy to administer, and consists of 30 items with a total score of 30. A score in range of 5-13 indicates reactive depression and a score between 14 and 23 indicates endogenous depression.[13] Scores were recorded at baseline and then at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 weeks after the treatment. Time to onset of action was defined as 40% reduction in the scores as compared to baseline.[14] Response to drugs was defined as decrease in HDRS, MADRS and ADI score of ≥50% from baseline. Remission was defined when the HDRS score was ≤7 and MADRS score was ≤12[14,15] in a patient.

[11] Secondary outcome measures included reduction in the score of Montgomery and Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS) and Amritsar depressive Inventory (ADI).[12,13] The MADRS score is designed to be sensitive to assess treatment effects. It has 10 items of core symptoms of depressive illness. Each item has a score range of 0-6., a score of >12 indicates depression.[12] The ADI scores are brief and effective psychological tool, easy to administer, and consists of 30 items with a total score of 30. A score in range of 5-13 indicates reactive depression and a score between 14 and 23 indicates endogenous depression.[13] Scores were recorded at baseline and then at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 weeks after the treatment. Time to onset of action was defined as 40% reduction in the scores as compared to baseline.[14] Response to drugs was defined as decrease in HDRS, MADRS and ADI score of ≥50% from baseline. Remission was defined when the HDRS score was ≤7 and MADRS score was ≤12[14,15] in a patient. Safety evaluation was based on spontaneously reported adverse effects and duration of hospitalization in the two groups. Laboratory investigations and ECG examination was also done at baseline and at the end of study i.e., 6 weeks.

Safety evaluation was based on spontaneously reported adverse effects and duration of hospitalization in the two groups. Laboratory investigations and ECG examination was also done at baseline and at the end of study i.e., 6 weeks.

Statistical Methods

The data was expressed as Mean±Standard Error (SE). The primary statistical analysis was intention to treat (ITT) analysis for all safety and efficacy variables with the last observation being carried forward (LOCF) for those patients who had at least 2 weeks data. Results were analyzed using nonparametric tests (Chi-Square, Friedman two way analyses, Kruskal Wallis test) and parametric tests (two-tailed test was used for t-test analysis). A P value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Both the groups tolerated the treatment. All the patients continued the medication till the end of treatment. summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients. The mean age of the patients in both the groups was comparable (41. 6 yrs in Group A vs. 38.6 in Group B). Similarly, the ratio of males and females was also comparable in both the groups (12:18 in Group A vs. 18:12 in Group B). The patient is both the groups had comparable HDRS score (20.76 in Group A vs. 20.53 in Group B). The mean duration of illness (3.82 in Group A vs. 3.6 in Group B) was comparable.

6 yrs in Group A vs. 38.6 in Group B). Similarly, the ratio of males and females was also comparable in both the groups (12:18 in Group A vs. 18:12 in Group B). The patient is both the groups had comparable HDRS score (20.76 in Group A vs. 20.53 in Group B). The mean duration of illness (3.82 in Group A vs. 3.6 in Group B) was comparable.

Table 1

Demographic and baseline characteristics of patients in both groups at baseline

Open in a separate window

Efficacy Variables

The HDRS, MADRS and ADI score reduced significantly as compared to baseline in both groups. HDRS score (mean±SE) at baseline was 20.76 ± 0.32 which reduced significantly to 10.23 ± 0.71 at the end of 6 weeks in group A. Similarly, HDRS score reduced significantly from 20.53 ± 0.47 to 7.7 ± 0.54 at the end of 6 weeks in group B []. The MADRS score (mean±SE) decreased significantly from 28.42 ± 0.64 to 14.62 ± 0.96 in group A and from 28.67 ± 1.03 to 11.03 ± 0.94 in group B at the end of 6 weeks []. The ADI score (mean±SE) decreased significantly from 19.15 ± 0.34 to 8 ± 0.56 in group A and from 18.3 ± 0.33 to 6.33 ± 0.48 in group B at the end of 6 weeks [].

The ADI score (mean±SE) decreased significantly from 19.15 ± 0.34 to 8 ± 0.56 in group A and from 18.3 ± 0.33 to 6.33 ± 0.48 in group B at the end of 6 weeks [].

Open in a separate window

Mean score of HDRS in both groups. P<0.05 as compared to SSRI group

Open in a separate window

Mean score of MADRS in both groups. P<0.05 as compared to SSRI group

Open in a separate window

Mean score of ADI in both groups. P<0.05 as compared to SSRI group

The improvement in group B was significantly (P<0.05) more as compared to group A from 2nd week onwards in HDRS score (16.1 ± 0.27 vs. 17.5 ± 0.36), 2nd week onwards in MADRS score (22.2 ± 0.68 vs. 23.9 ± 0.58) and at 3rd week onward in ADI score (12.5 ± 0.29 vs. 13.2 ± 0.37).

shows onset of action in both groups. Onset of action was at 4 weeks in Group B and 5 weeks in group A in HDRS and MADRS score, but at 4 weeks in group B and Group A in ADI score. The number of responders was more in group B as compared to group A []. The difference was statistically significant at 5th week (22 vs. 9) in HDRS score. Similarly in MADRS score also there were more number of responders in group B as compared to group A at 6th week (28 vs. 16). The number of remitters in our study was more in group B as compared to group A, this was statistically significant in HDRS score at 6 weeks (20 vs. 3) and at 5 weeks (10 vs. 3) and 6 weeks (23 vs. 15) in MADRS score []. There was no significant difference in vital parameters at the end of 6 weeks as compared to baseline in both groups. There was no significant difference between the groups too. Baseline systolic blood pressure/diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP) was 119/79 and 123/82 mm of Hg in group A and group B respectively. The SBP/DBP at the end of treatment was 126/84 and 122/84 mm of Hg in group A and group B, respectively.

The number of responders was more in group B as compared to group A []. The difference was statistically significant at 5th week (22 vs. 9) in HDRS score. Similarly in MADRS score also there were more number of responders in group B as compared to group A at 6th week (28 vs. 16). The number of remitters in our study was more in group B as compared to group A, this was statistically significant in HDRS score at 6 weeks (20 vs. 3) and at 5 weeks (10 vs. 3) and 6 weeks (23 vs. 15) in MADRS score []. There was no significant difference in vital parameters at the end of 6 weeks as compared to baseline in both groups. There was no significant difference between the groups too. Baseline systolic blood pressure/diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP) was 119/79 and 123/82 mm of Hg in group A and group B respectively. The SBP/DBP at the end of treatment was 126/84 and 122/84 mm of Hg in group A and group B, respectively.

Table 2

Time to onset of action in both groups

Open in a separate window

Table 3

Number (percentage) of responders and remitters in both groups

Open in a separate window

Adverse Events

There was no serious adverse event reported in both the groups. Two patients reported somnolence in group B. Two patients reported mild adverse events during treatment in group A. One patient withdrew from the study from group A due to the complaint of impairment in ejaculation. No significant change was observed in ECG in any patient in both the groups. There was no prolongation of hospitalization in any patient. No patient was lost to the follow-up.

Two patients reported somnolence in group B. Two patients reported mild adverse events during treatment in group A. One patient withdrew from the study from group A due to the complaint of impairment in ejaculation. No significant change was observed in ECG in any patient in both the groups. There was no prolongation of hospitalization in any patient. No patient was lost to the follow-up.

Although there are a number of therapeutic choices available for the treatment of major depression, it is generally acknowledged that current first line therapies provide less than satisfactory outcome in many instances. This is because nearly two-third of all patient are either partially or completely nonresponsive, only one-third experience full remission and many have tolerability concern that limit long-term treatment.[16] Thus the development of new agents that can meaningfully expand the expected therapeutic effect and tolerability of antidepressant therapy is an important medical need.

Mirtazapine is a α2 adrenergic antagonist produces a rapid increase in both noradrenergic and serotonergic transmission with enhance tonic activation of post synaptic serotonergic receptors. [4,17] Mirtazapine has shown significant improvement in depressed patients with anxiety and insomnia, including decreased sleep-onset latency, deeper sleep and fewer awakenings.[18,19] It is effective for augmentation or combination therapy in patients with refractory depression.[4]

In the present study, low dose add on mirtazapine therapy was very effective in improving HDRS score in patients of major depression. Low dose add on mirtazapine therapy also significantly improved MADRS and ADI scores in these patients. These results are in agreement with earlier studies which demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in the total score on the HDRS-17 and nearly all secondary efficacy measures, including remission, MADRS and ADI.[8,20] The response rate and number of remitters were significantly more with low dose add on mirtazapine therapy as compared to conventional therapy at the end of study. The HDRS-17 subset scores indicate that add on low-dose mirtazapine therapy was more effective in improving anxiety and somatic symptoms as compared to conventional therapy. These findings are in agreement with earlier studies.[4]

In this study, times to onset of action with low dose add on mirtazapine therapy, was earlier as compared to conventional therapy, with more responders at an earlier time period as seen with earlier studies.[20]

The most common adverse effects reported in our study with add on mirtazapine therapy was somnolence, whereas in the conventional group patients reported with nausea and sexual dysfunction. The adverse effect does not seem to be due to combination of mirtazapine with conventional therapy as the common adverse event reported with conventional therapy is insomnia, so both groups differ with respect to adverse events.

These results confirm and extend earlier finding, that mirtazapine, a dual action antidepressant is an effective and safe antidepressant in Indian patients of major depressive disorder for short-term augmentation and may be of more clinical utility in alleviation of anxiety symptoms and improvement of quality of life associated with depression. [21]

Our study showed that both treatment groups showed significant decrease in HDRS, MADRS and ADI score in both groups as compared to baseline. However, patients treated with add on low-dose mirtazapine had earlier onset of action and more number of responders and remitters. None of the groups had severe adverse events. Long term studies may help us find out whether the adverse event documented could be present on long-term follow-up.

In conclusion, add-on therapy with mirtazapine had earlier onset of action, better efficacy and more number of responders and remitters as compared to conventional therapy in MDD in Indian patients.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

1. Hyman S, Chisholm D, Kessler R, Patel V, Whiteford H. Mental disorders. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, et al., editors. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press for the World Bank; 2006. pp. 605–25. [Google Scholar]

2. World Health Organization. Mental and behavioural disorders, department of mental health [Online] 2000. [Last cited in 2011]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/59.pdf .

3. Aaron R, Joseph A, Abraham S, Muliyil J, George K, Prasad J, et al. Suicides in young people in rural southern India. Lancet. 2004;363:1117–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Baldessarini RJ. Drug therapy of depression and anxiety disorder. In: Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL, editors. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006. pp. 429–60. [Google Scholar]

5. Davidson JR, Meltzer-Brody SE. The under recognition and under treatment of depression: What is the breadth and depth of the problem? J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Whooley MA, Simon GE. Managing depression in medical outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1942–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Carpenter LL, Jocic Z, Hall JM, Rasmussen SA, Price LH. Mirtazapine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:45–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Papakostas GI, Homberger CH, Fava M. A meta–analysis of clinical trials comparing mirtazapine with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:843–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Sartorius N. The classification of mental disorders in international classification of disease. In: Saddock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, editors. Kaplan and Sadocks Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. pp. 1139–51. [Google Scholar]

10. Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) 4th ed. Washington D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder; p. 356. [Google Scholar]

11. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Montgomery SA, Asberg MA. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Singh G. A new depressive inventory (Amritsar Depressive Inventory) Indian J Psychiatry. 1974;16:183–8. [Google Scholar]

14. Thase ME. Methodology to measure onset of action. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 15):18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Nierenberg AA. Do some antidepressants work faster than others? J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 15):22–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Mulrow CD, William JW, Chiquette E, Aguilar C, Hitchcock-Noel P, Lee S, et al. Efficacy of newer medication for treating depression in primary care patients. Am J Med. 2000;108:54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Haddjeri N, Blier P, de Montigny C. Noradrenergic modulation of central serotonergic neurotransmission: Acute and long-term actions of mirtazapine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;10(Suppl 4):11–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Ruigt GS, Kemp B, Groenhout CM, Kamphuisen HA. Effect of the antidepressant Org 3770 on human sleep. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;38:551–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Sorensen M, Jorgensen J, Viby-Mogensen J, Bettum V, Dunbar GC, Steffensen K. A double-blind group comparative study using the new anti-depressant Org 3770, placebo and diazepam in patients with expected insomnia and anxiety before elective gynaecological surgery. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1985;71:339–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Carpenter LL, Yasmina S, Pricea LH. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of antidepressant augementation with mirtazapine. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;51:183–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Bruscoli M. Response acceleration with mirtazapine augmentation of citalopram in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients without comorbid depression: A Pilot Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1394–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90,000 serpentin and escitalopram - the best of the new antidepressantssertralin and escitalopram - the best of the new antidepressants

02.

The new analysis showed that the sertralin 1 (Zoloft) and escitalopram 9000 2 (LexAp) of the 12 new generation antidepressants, while reboxetine is the least effective drug.

Italian researchers studied the results of 117 studies involving more than 25,000 patients with depression.

The drugs studied were: bupropion 3 (Zyban), citalopram 4 (Selexa), duloxetine 5 (Cymbalta), escitalopram, fluoxetine 6 (Prozac), fluvoxamine 9009 milnacipamine 7009 8 (savella), mirtazapine 9 (remeron), paroxetine 10 (paxil), reboxetine 11 (vestra), sertraline and venlafaxine 12 (effexor).

Data analysis showed that sertratalin and escitalopram are the best antidepressants in terms of efficacy and tolerability. Sertratalin was more effective than duloxetine (by 30%), fluvoxamine (by 27%), fluoxetine (by 25%), paroxetine (by 25%) and reboxetine (by 85%). Escilatopram was more effective than duloxetine (by 33%), fluoxetine (by 32%), fluvoxamine (by 35%), paroxetine (by 30%) and reboxetine (by 9%).5%).

Mirtazapine and venlafaxine were equally effective as sertratalin and escitalopram, but the latter two were better tolerated.

The results of the study were published online on January 29th and will be published in the next issue of The Lancet.

"The most important clinical implication of the results is that escitalopram and sertratalin are the best drugs for the treatment of moderate to severe depression in terms of efficacy and tolerability," said Dr. Andrea Cipriani of the University of Verona (Italy) in a news release of the journal.

"Sertratalin is a preferred drug over escitalopram because of its lower cost in most countries," he added.

Retrieved from HealthDay, January 29, 2009.

Prepared by ML

1 - In the Russian Federation sertraline is registered under the trade names Asentra, Deprefolt, Zolovt, Seralin, Serenata, Serlift, Sertraline hydrochloride, Stimuloton, Torin0055

3 - Not registered in the Russian Federation

4 - Citalopram is registered in the Russian Federation under the trade names Oprah, Pram, Sedopram, Siozam, Umorap, Cipramil, Citalek, Citalift, Citalopram Hydrobromide, Citalorin, Citol

5 - In Russia, duloxetine is registered under the trade names Intriv, Simbalta6 - In Russia, it is registered under the trade names Apo-Fluoxetine, Prodep, Prozac, Profluzak, Fluval, Fluoxetine-Acri capsules, Fluoxetine, Fluoxetine-Canon, Fluoxetine Geksal, Fluoxetine Lannacher, Fluoxetine hydrochloride

7 - Fluvoxamine is registered in the Russian Federation under the trade name Fevarin

8 - Milnacipran is registered in the Russian Federation under the trade name Ixel

10 - Paroxetine is registered in the Russian Federation under the trade names Adepress, Actaparoxetine, Apo-Paroxetine, Paxil, Paroxetine, Paroxetine Hydrochloride Hemihydrate, Plizil, Reksetin, Sirestill

11 - Not registered in Russia

12 - Registered in Russia under trade names Alventa, Velaxin, Velafax, Venlaxor, Efevelon

Return

What Will Mirtazapine Do? Mirtazapine should help you feel calm and relaxed . It may take some time for mirtazapine to show its full effect. This effect should reduce your behavior problems.

Also, does everyone put on weight after taking mirtazapine?

Mirtazapine is less likely to cause weight gain than with TCA. It also doesn't lead to as many other side effects as other antidepressants.

Accordingly, does mirtazapine 30 mg work better than 15 mg?

No significant differences were found between the increase (45) and stay (30) groups. Conclusions. Increasing the dose of mirtazapine from 15 mg/day to 30 mg/day may be effective in patients with depression without initial improvement. However, efficacy cannot be higher than 30 mg/day. .

exactly the same. How much mirtazapine should I take for anxiety?

How much will I take? The usual starting dose of mirtazapine is 15 at 30mg per day . This can be increased to 45 mg per day. If you have liver or kidney problems, your doctor may prescribe a lower dose.

Can I take mirtazapine intermittently?

Take this medicine exactly as directed by your doctor to get the best results for you. Take no more don't take it more often , and don't take it longer than your doctor has told you to.

Contents

Does mirtazapine make you happy?

Mirtazapine will not change your personality or make you euphorically happy . It will just help you feel like yourself again. However, don't expect to feel better overnight. Some people feel worse during the first few weeks of treatment before they start to feel better.

What is the best antidepressant for weight loss?

There are over a dozen antidepressants commonly prescribed. But only one has been consistently associated with weight loss in studies: bupropion (brand name Wellbutrin) .

Does mirtazapine 30 mg calm you down?

Results: 15mg/kg dose of MIR-induced sedation for up to 60 minutes, while 30mg/kg or more sedated 0112 minutes and only in the first days of admission.

What is the strongest antidepressant?

The most effective antidepressant compared with placebo was the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline , more than doubling the likelihood of response to treatment (odds ratio [OR] 2.13, 95% confidence interval [CrI] 1.89–2.41).

How soon will mirtazapine make you sleepy?

Tablets 15 mg and are fully effective. in about 9 hours0112 . At nights of intense restlessness, restlessness, and agitation, mirtazapine can slow my thoughts down and make me feel deeply tired, allowing me to fall into a deep sleep.

Is 7.5 mg of mirtazapine enough for sleep?

Major original studies support FDA-approved prescription of the antidepressant mirtazapine 15–45 mg/day. Although the drug is commonly used off-label at lower doses (7.5 to 15 mg at bedtime), primarily for a sedative effect, the antidepressant effects of at doses of 7.5 mg/day have not been reported.

How does mirtazapine help with anxiety?

Mirtazapine appears to act as an alpha-2 antagonist, hence increasing synaptic norepinephrine and serotonin, and also blocks some postsynaptic serotonergic receptors that conceptually mediate excessive anxiety when stimulated by serotonin.

What is the best antidepressant for anxiety?

The antidepressants most commonly prescribed for anxiety are SSRIs such as Prozac, Zoloft, Paxil, Lexapro and Celexa . SSRIs have been used to treat generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

How much weight do you gain on mirtazapine?

Remeron (mirtazapine) may make you feel more hungry than usual and lead to weight gain. For most people, this weight gain is 5 to 10 pounds .

Does mirtazapine make you angry?

Precautions - when taking mirtazapine

It can also cause agitation, aggression and forgetfulness. . If you drink alcohol, drink only small amounts and see how you feel. Don't stop taking your medication. If you develop a fever, sore throat or mouth while taking mirtazapine, tell your doctor right away.

Which anxiety medications cause weight loss?

Bupropion is an antidepressant that may cause weight loss in some people. Antidepressants are a common form of treatment for depression.

How can I avoid weight gain on antidepressants?

How to avoid weight gain associated with taking antidepressants

- Reasons.

- Talk to your doctor.

- Ask about a change of medication.

- Get a medical examination.

- Add diet and exercise.

How fast can you lose weight on Wellbutrin?

A 2012 study showed that obese adults who took bupropion SR (standard release) at doses of 300 or 400 mg lost 7.2% and 10% of body weight, respectively, over 24 weeks and maintained this weight loss by 48 weeks (Anderson, 2012).

Will mirtazapine 30 mg help me sleep?

Mirtazapine has been found to reduce the time it takes a person to fall asleep as well as reducing the duration of early, light sleep stages and increasing the depth of sleep 2 . It also slightly reduces REM (sleep within a dream) and nighttime wakefulness, and improves the continuity and overall quality of sleep. 3 .

How many milligrams of mirtazapine should I take while I sleep?

Major original studies support FDA-approved prescription of the antidepressant mirtazapine 15–45 mg/day. Although the drug is commonly used off-label at lower doses ( 7. 5 to 15 mg at bedtime ) primarily due to its hypnotic effect, an antidepressant effect has been reported at doses of 7.5 mg/day.

Does mirtazapine lose its effectiveness for sleep?

So, it is used in low dosage (15mg) because of its sedative effect. It is described that, at higher dosages this sedative effect is "lost" .

What is the #1 antidepressant?

Zoloft is the most commonly prescribed antidepressant; nearly 17% of participants in a 2017 antidepressant use study reported that they were taking the medication. 1 Paxil (paroxetine): You may be more likely to get sexual side effects if you choose paxil compared to other antidepressants.

What are the top 5 antidepressants?

The 12 most popular and effective antidepressants: a list of psychiatrists

- Celexa (citalopram)

- Wellbutrin (bupropion)

- Paxil (paroxetine)

- Savella (milnacipran)

- Prozac (fluoxetine)

- Cymbalta (duloxetine)

- Luvox (fluvoxamine)

- Vestra (reboxetine)

What is the strongest medicine for anxiety?

The strongest anti-anxiety medication currently available is: benzodiazepines , Xanax to be exact.