Motivational interviewing process

The 4 Processes of Motivational Interviewing

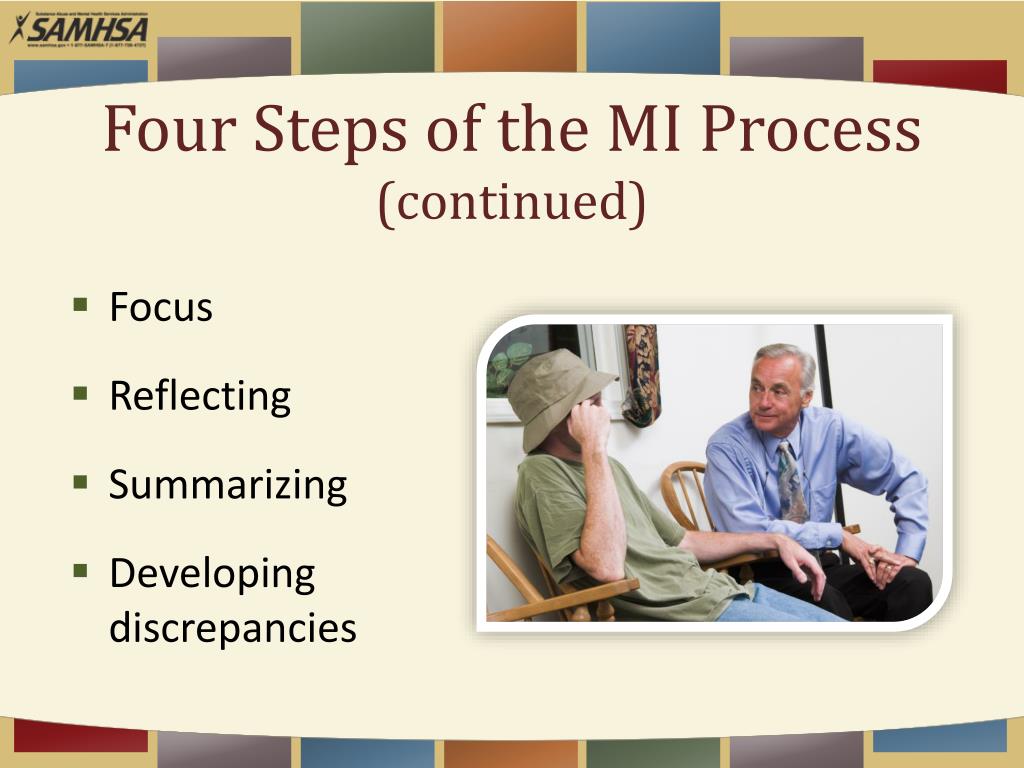

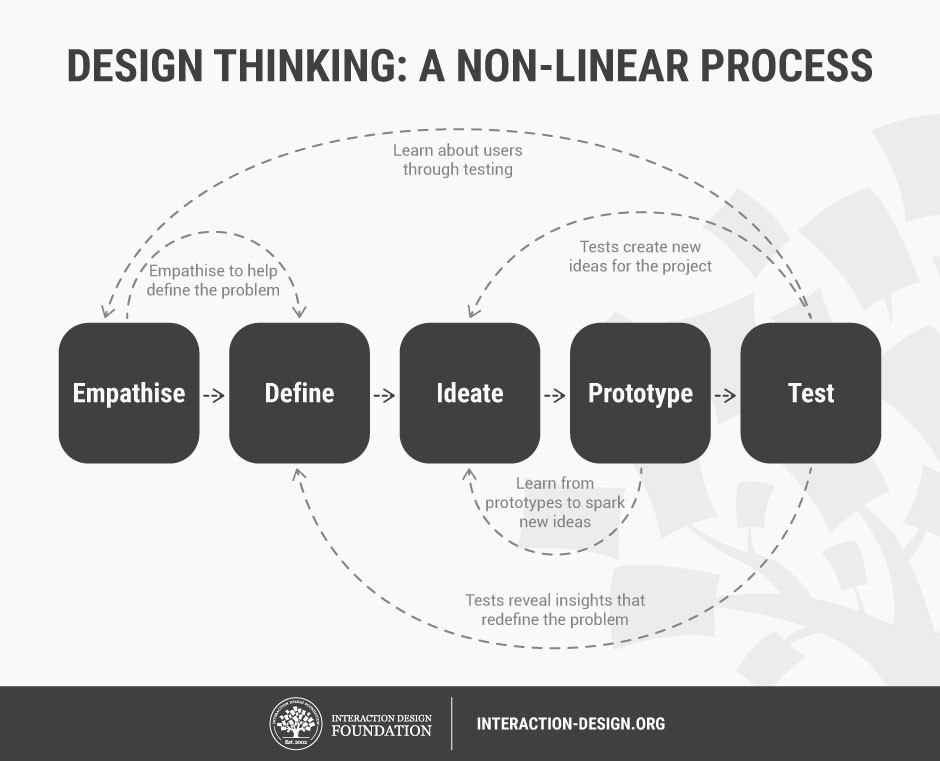

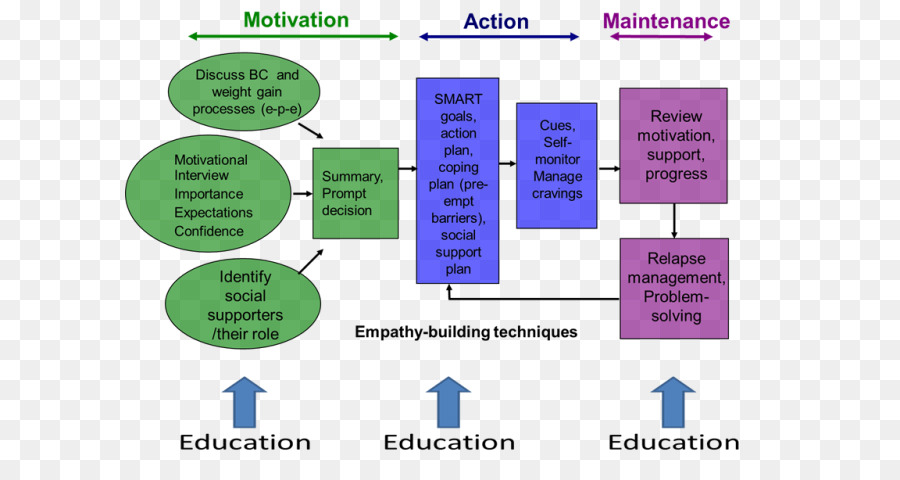

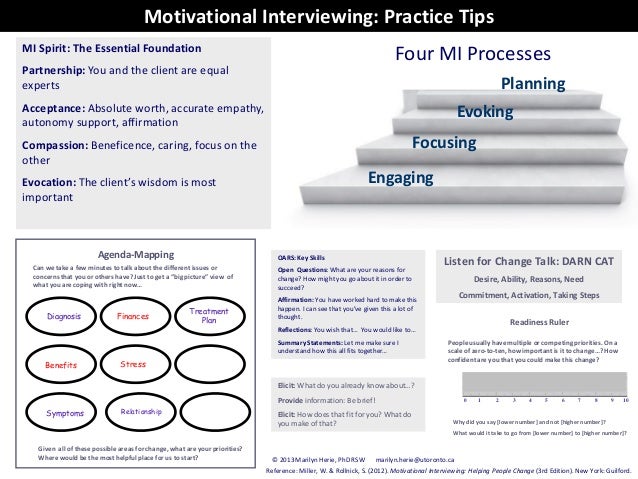

A successful motivational interviewing conversation has four different processes: engagement, focusing, evoking, and planning. The steps often aren’t linear.

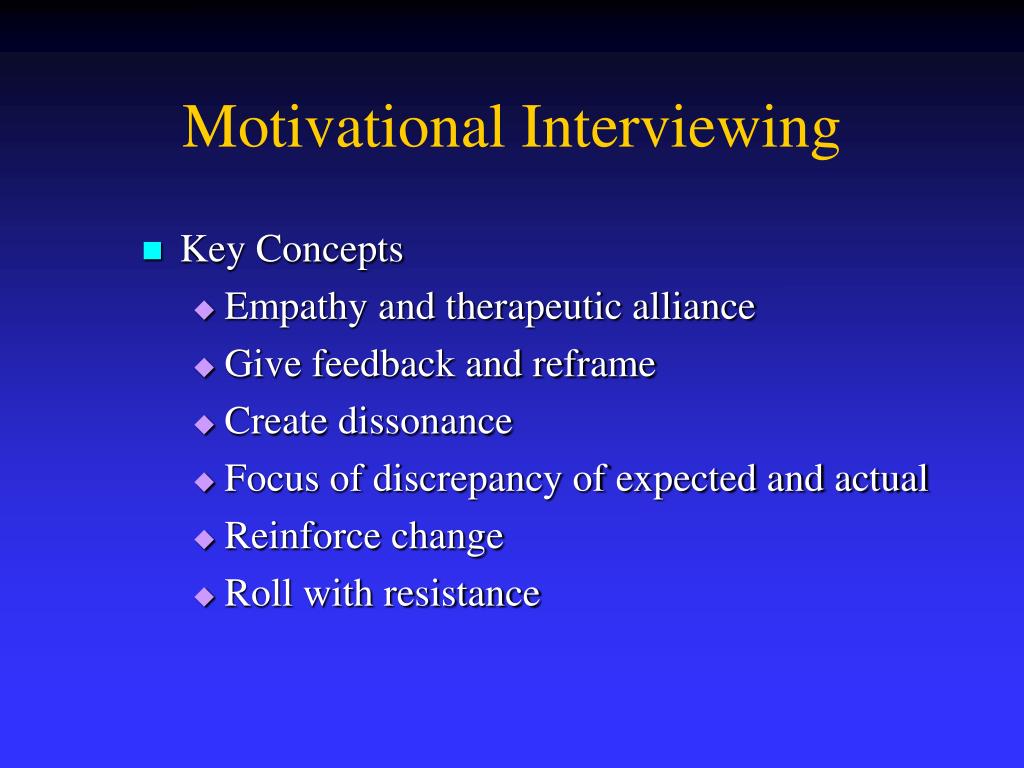

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a coaching or counseling style based on the fundamental idea that motivation must come from the person making the personal change (rather than change being forced by the counselor).

The creators of MI, William Miller and Stephen Rollnick, define motivational interviewing as “a directive, client-centred counselling style for eliciting behaviour change by helping clients to explore and resolve ambivalence.”

In their book “Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change,” Miller and Rollnick have defined four essential processes of motivational interviewing that the practitioner and the client should move through.

The general process of MI is dynamic and can differ based on the client’s needs, and the four processes aren’t linear. Practitioners can return to previous processes any time. However, certain processes need to come before others; for example, focusing always needs to come before evoking.

If you’re a healthcare professional or mental health therapist you’re probably familiar with the concept of engagement, also known as relationship-building or therapeutic rapport. This is an essential process for any health counseling, not just MI.

Trust is critical in the MI relationship. The person receiving care needs to understand that their MI practitioner wants what is best for them and that they and their counselor are equal partners.

To build engagement during this process, MI practitioners rely on several key MI concepts, including:

- accurate empathy

- autonomy

- acceptance

- OARS (open questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries)

The care recipient should enter into the relationship knowing that their MI practitioner will not try to force them to make changes they are not ready to make. Their autonomy will always be honored, as will their expertise on their own life.

Their autonomy will always be honored, as will their expertise on their own life.

Engagement is a process that happens continuously throughout the entire MI relationship — not just as a first step.

And although the processes of MI are not often linear, engagement needs to come first. Without engagement, discord (conflict) will likely come up in the relationship later.

MI is more than a supportive conversation. For MI to be effective, both the care recipient and the practitioner need to be in agreement about the end goal of treatment.

The second process of MI — focusing — is where goal agreements take place. Focusing is a necessary prerequisite for the next process of MI: evoking. Without focusing, this practice isn’t MI.

In some settings, some goals are predetermined. For example, a substance use counselor providing court-ordered treatment will by definition try to move the care recipient toward changing their substance use habits.

When there is a predefined focus, but the client doesn’t share a willingness to set this as the goal of treatment, then the focus should be negotiated between you. Practitioners can also use evoking (the next process of MI) to decrease the client’s ambivalence (mixed feelings).

Practitioners can also use evoking (the next process of MI) to decrease the client’s ambivalence (mixed feelings).

But focusing is also where the care recipient’s expertise on their own life needs to come into play. For example, they might say that to be able to change their substance use habits, they need to first find a mental health therapist to address their depression. Their expertise about what’s best for them needs to be honored.

MI doesn’t work when the overall goal of the conversation isn’t clear, defined, and agreed upon between both parties.

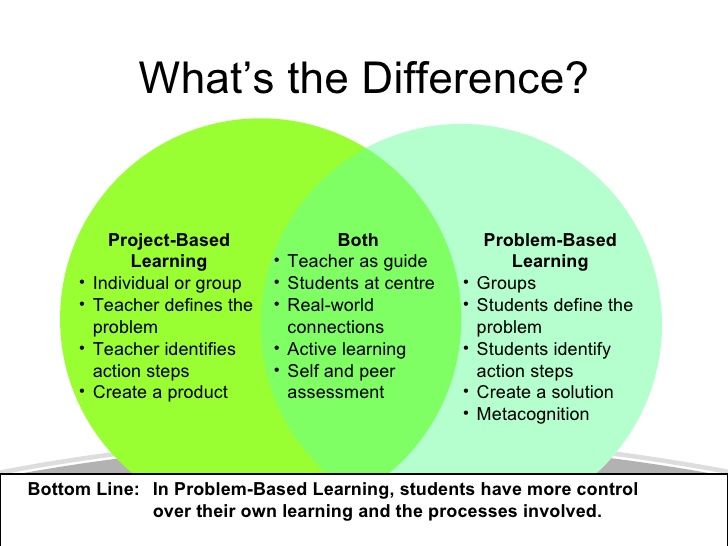

In many ways, the process of evoking is what makes MI unique among counseling styles. Other counseling or therapy methods also include engagement, focusing, and planning — but evoking is how MI practitioners increase motivation toward change.

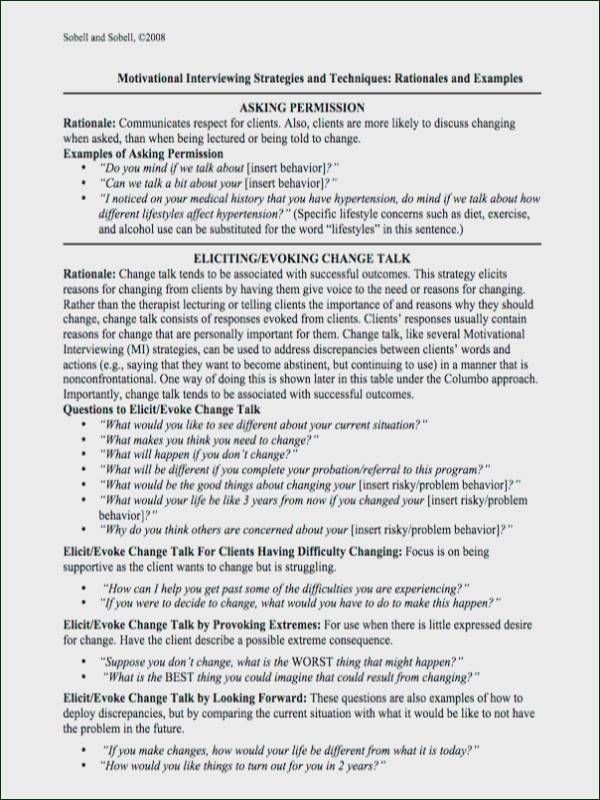

Evoking is an MI-specific process where the practitioner draws out “change talk” from the care recipient about the focus. Change talk is any statement made by the care recipient that supports making the change.

For example, in the statement “I know I need to quit drinking, but I just don’t think I can do it,” the statement, “I know I need to quit drinking” is change talk.

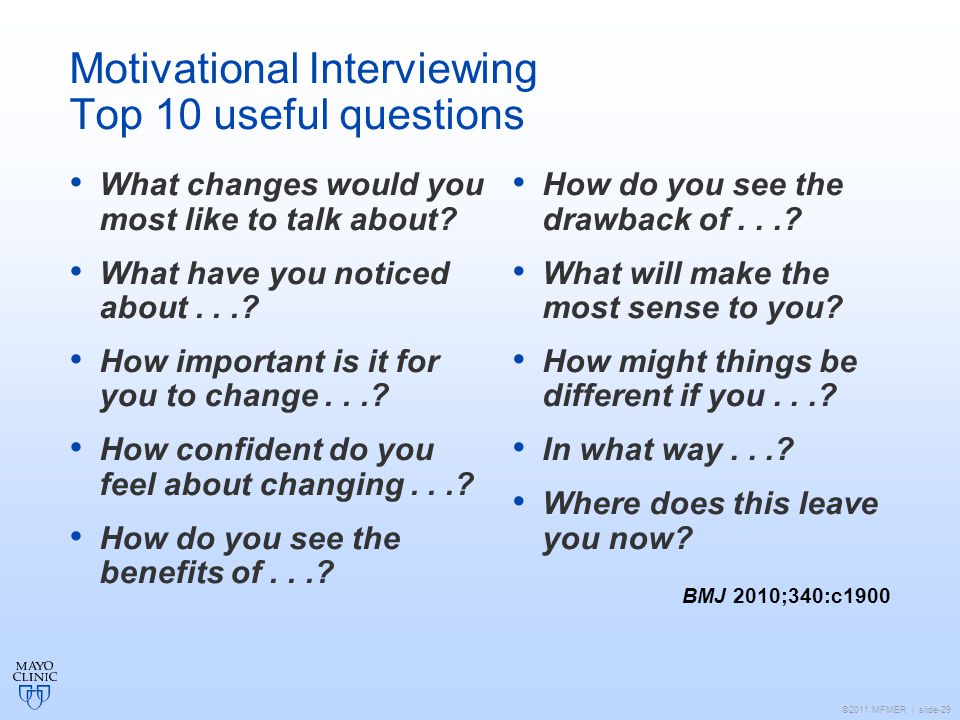

MI practitioners evoke change talk using various methods, including:

- open questions

- targeted reflections

- providing summaries

For example, after hearing the above statement the MI practitioner might reflect in a way that emphasizes the change talk, such as, “This is really important to you — you know you need to quit, and at this point, you’re just looking for ways to be successful.” They could also ask a question: “What are the reasons you think you need to quit?”

For evoking to be successful, MI practitioners must be able to recognize, reflect, and ask questions to elicit change talk even when the care recipient is very ambivalent. This is also why focusing is so important — without a determined focus or goal it’s impossible to know what change to evoke change talk for.

MI differs from other counseling methods because practitioners actively encourage (evoke) change talk and hope rather than instilling it. In the process of evoking, practitioners never give unsolicited advice or tell the care recipient why they have to change. Instead, they draw out the client’s reasons for wanting or needing to change.

If practitioners don’t recognize change talk, and if they try to force the person to change, then discord will arise in the relationship.

Planning is the only process that’s not necessary for the MI relationship. This is because, if evoking is done well, then care recipients are often able to make a plan on their own.

As a practitioner, perhaps the most important part of planning is remembering that you don’t need to have all of the answers. Trust your client’s expertise on their own life. Although you can provide some professional expertise when necessary, your client will also have answers about what type of plan will work best for them.

One of the most important tasks in the MI process of planning is helping the care recipient get there. To do this, you can ask key questions, such as:

- So you’ve told me that you need to change and that you feel like you can if you really put your mind to it. What do you think you’ll do next?

- What’s your plan for moving forward?

- How will you know if you’ve been successful in your plan?

Planning is also the process in which attending to possible barriers to success could be appropriate. Talking about barriers earlier in the processes, when the care recipient may still be ambivalent, could be counterproductive.

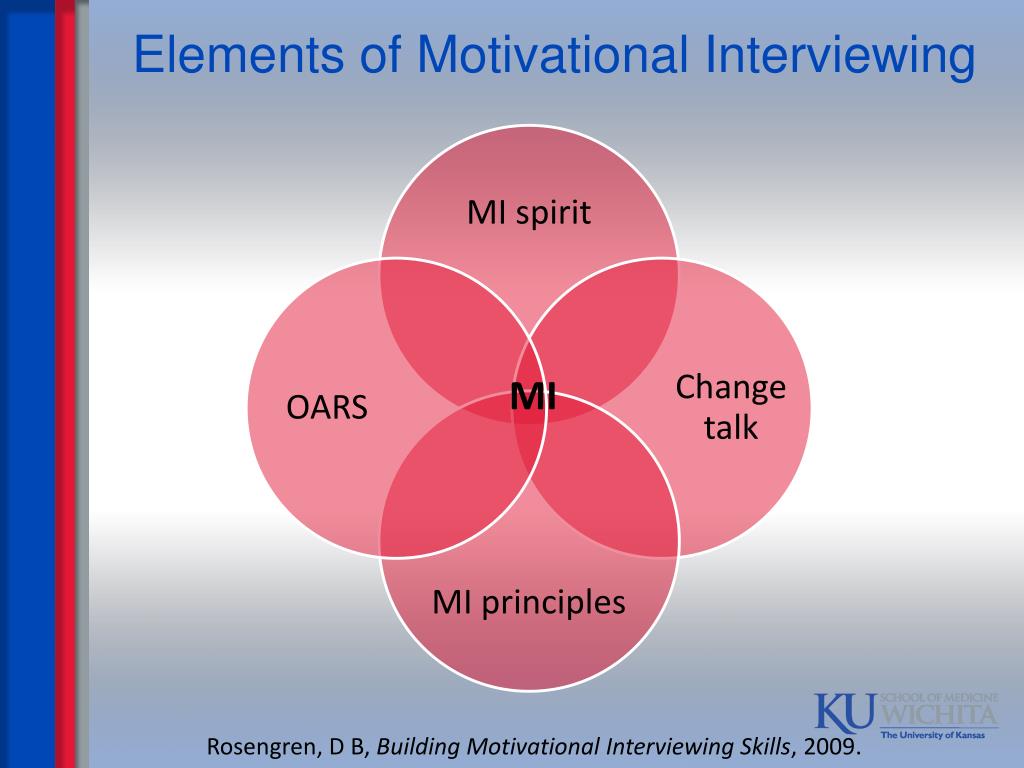

On top of being familiar with the four processes of MI, there are also other concepts you need to keep in mind to be able to successfully facilitate an MI conversation:

- Check your righting reflex. The righting reflex is a key MI concept. It refers to the practitioner’s instinct to “fix” the client. Remember that your role is to be a guide, not a savior.

- Don’t be afraid to move between processes. For example, if discord arises while you’re evoking around a specific goal, then move back to focusing to discuss a different goal with your client.

- Remember to use more reflections than questions. Asking too many questions in a row, especially closed questions, can make your client feel interrogated.

- Try to let go of the “assessment mindset.” Your goal as an MI practitioner is to evoke motivation from the client to change. It isn’t to gather factual information. You can practice MI even when you don’t have all the facts about the client’s life.

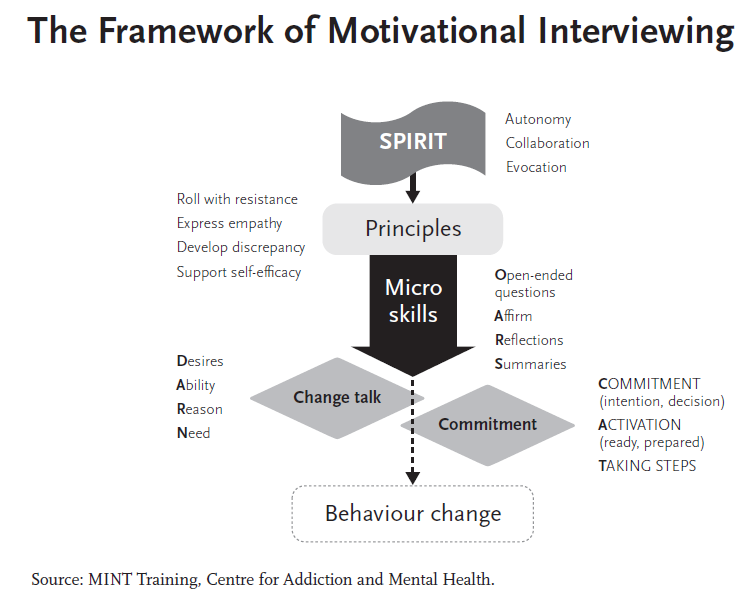

- Keep the spirit of MI in mind as you move through the processes. The four spirits of MI are:

- partnership or collaboration

- compassion

- evocation

- acceptance

There are four processes to an MI conversation: engaging, focusing, evoking, and planning.

Planning is the only process that isn’t a necessary component of MI. Although the processes are dynamic and often not linear, there is also a logical sequence to them (for example, engaging must necessarily come first — but it can also be revisited later on in the process).

Although the processes are dynamic and often not linear, there is also a logical sequence to them (for example, engaging must necessarily come first — but it can also be revisited later on in the process).

To learn more MI strategies, look for opportunities to train with a member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT).

The 4 Processes of Motivational Interviewing

A successful motivational interviewing conversation has four different processes: engagement, focusing, evoking, and planning. The steps often aren’t linear.

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a coaching or counseling style based on the fundamental idea that motivation must come from the person making the personal change (rather than change being forced by the counselor).

The creators of MI, William Miller and Stephen Rollnick, define motivational interviewing as “a directive, client-centred counselling style for eliciting behaviour change by helping clients to explore and resolve ambivalence. ”

”

In their book “Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change,” Miller and Rollnick have defined four essential processes of motivational interviewing that the practitioner and the client should move through.

The general process of MI is dynamic and can differ based on the client’s needs, and the four processes aren’t linear. Practitioners can return to previous processes any time. However, certain processes need to come before others; for example, focusing always needs to come before evoking.

If you’re a healthcare professional or mental health therapist you’re probably familiar with the concept of engagement, also known as relationship-building or therapeutic rapport. This is an essential process for any health counseling, not just MI.

Trust is critical in the MI relationship. The person receiving care needs to understand that their MI practitioner wants what is best for them and that they and their counselor are equal partners.

To build engagement during this process, MI practitioners rely on several key MI concepts, including:

- accurate empathy

- autonomy

- acceptance

- OARS (open questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries)

The care recipient should enter into the relationship knowing that their MI practitioner will not try to force them to make changes they are not ready to make. Their autonomy will always be honored, as will their expertise on their own life.

Their autonomy will always be honored, as will their expertise on their own life.

Engagement is a process that happens continuously throughout the entire MI relationship — not just as a first step.

And although the processes of MI are not often linear, engagement needs to come first. Without engagement, discord (conflict) will likely come up in the relationship later.

MI is more than a supportive conversation. For MI to be effective, both the care recipient and the practitioner need to be in agreement about the end goal of treatment.

The second process of MI — focusing — is where goal agreements take place. Focusing is a necessary prerequisite for the next process of MI: evoking. Without focusing, this practice isn’t MI.

In some settings, some goals are predetermined. For example, a substance use counselor providing court-ordered treatment will by definition try to move the care recipient toward changing their substance use habits.

When there is a predefined focus, but the client doesn’t share a willingness to set this as the goal of treatment, then the focus should be negotiated between you. Practitioners can also use evoking (the next process of MI) to decrease the client’s ambivalence (mixed feelings).

Practitioners can also use evoking (the next process of MI) to decrease the client’s ambivalence (mixed feelings).

But focusing is also where the care recipient’s expertise on their own life needs to come into play. For example, they might say that to be able to change their substance use habits, they need to first find a mental health therapist to address their depression. Their expertise about what’s best for them needs to be honored.

MI doesn’t work when the overall goal of the conversation isn’t clear, defined, and agreed upon between both parties.

In many ways, the process of evoking is what makes MI unique among counseling styles. Other counseling or therapy methods also include engagement, focusing, and planning — but evoking is how MI practitioners increase motivation toward change.

Evoking is an MI-specific process where the practitioner draws out “change talk” from the care recipient about the focus. Change talk is any statement made by the care recipient that supports making the change.

For example, in the statement “I know I need to quit drinking, but I just don’t think I can do it,” the statement, “I know I need to quit drinking” is change talk.

MI practitioners evoke change talk using various methods, including:

- open questions

- targeted reflections

- providing summaries

For example, after hearing the above statement the MI practitioner might reflect in a way that emphasizes the change talk, such as, “This is really important to you — you know you need to quit, and at this point, you’re just looking for ways to be successful.” They could also ask a question: “What are the reasons you think you need to quit?”

For evoking to be successful, MI practitioners must be able to recognize, reflect, and ask questions to elicit change talk even when the care recipient is very ambivalent. This is also why focusing is so important — without a determined focus or goal it’s impossible to know what change to evoke change talk for.

MI differs from other counseling methods because practitioners actively encourage (evoke) change talk and hope rather than instilling it. In the process of evoking, practitioners never give unsolicited advice or tell the care recipient why they have to change. Instead, they draw out the client’s reasons for wanting or needing to change.

If practitioners don’t recognize change talk, and if they try to force the person to change, then discord will arise in the relationship.

Planning is the only process that’s not necessary for the MI relationship. This is because, if evoking is done well, then care recipients are often able to make a plan on their own.

As a practitioner, perhaps the most important part of planning is remembering that you don’t need to have all of the answers. Trust your client’s expertise on their own life. Although you can provide some professional expertise when necessary, your client will also have answers about what type of plan will work best for them.

One of the most important tasks in the MI process of planning is helping the care recipient get there. To do this, you can ask key questions, such as:

- So you’ve told me that you need to change and that you feel like you can if you really put your mind to it. What do you think you’ll do next?

- What’s your plan for moving forward?

- How will you know if you’ve been successful in your plan?

Planning is also the process in which attending to possible barriers to success could be appropriate. Talking about barriers earlier in the processes, when the care recipient may still be ambivalent, could be counterproductive.

On top of being familiar with the four processes of MI, there are also other concepts you need to keep in mind to be able to successfully facilitate an MI conversation:

- Check your righting reflex. The righting reflex is a key MI concept. It refers to the practitioner’s instinct to “fix” the client. Remember that your role is to be a guide, not a savior.

- Don’t be afraid to move between processes. For example, if discord arises while you’re evoking around a specific goal, then move back to focusing to discuss a different goal with your client.

- Remember to use more reflections than questions. Asking too many questions in a row, especially closed questions, can make your client feel interrogated.

- Try to let go of the “assessment mindset.” Your goal as an MI practitioner is to evoke motivation from the client to change. It isn’t to gather factual information. You can practice MI even when you don’t have all the facts about the client’s life.

- Keep the spirit of MI in mind as you move through the processes. The four spirits of MI are:

- partnership or collaboration

- compassion

- evocation

- acceptance

There are four processes to an MI conversation: engaging, focusing, evoking, and planning.

Planning is the only process that isn’t a necessary component of MI. Although the processes are dynamic and often not linear, there is also a logical sequence to them (for example, engaging must necessarily come first — but it can also be revisited later on in the process).

Although the processes are dynamic and often not linear, there is also a logical sequence to them (for example, engaging must necessarily come first — but it can also be revisited later on in the process).

To learn more MI strategies, look for opportunities to train with a member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT).

5 motivational interview questions (with sample answers) • BUOM

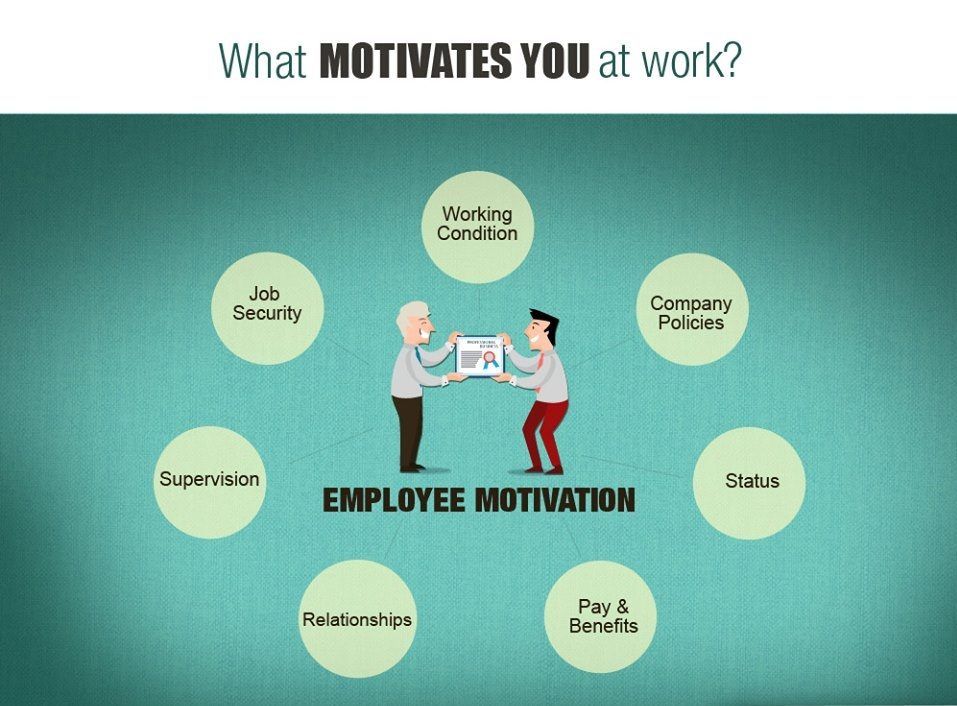

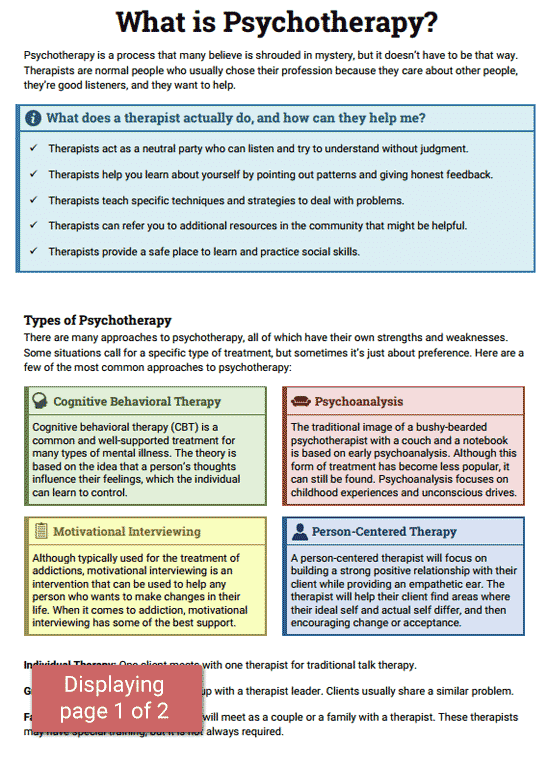

The motivational interview is a tool that can help people think about how they feel about themselves and their jobs. During such an interview, you can learn more about your attitude to work by answering open-ended questions. Understanding the nature of the questions and the best way to answer them will help you feel confident giving effective answers during a motivational interview.

In this article, we list five typical motivational interview questions and provide sample answers to help you prepare for a motivational interview.

What is a motivational interview?

Motivational interviewing is a counseling technique designed to help people find their intrinsic motivation to change. In the workplace, the motivational interview method is sometimes used to help current employees who feel they need to make some changes in their work lives. As the name suggests, they are looking for new inspiration that will help them carry out their work tasks with excitement and passion. Instead of suggesting possible changes, motivational interviewers often try to help their interviewees find solutions on their own. They do this by using questions that help the interviewee evaluate their own work life and what they think might help them resolve their current situation. nine0003

In the workplace, the motivational interview method is sometimes used to help current employees who feel they need to make some changes in their work lives. As the name suggests, they are looking for new inspiration that will help them carry out their work tasks with excitement and passion. Instead of suggesting possible changes, motivational interviewers often try to help their interviewees find solutions on their own. They do this by using questions that help the interviewee evaluate their own work life and what they think might help them resolve their current situation. nine0003

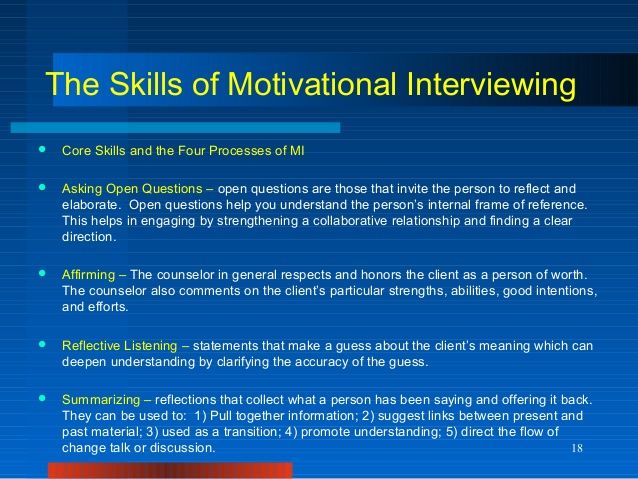

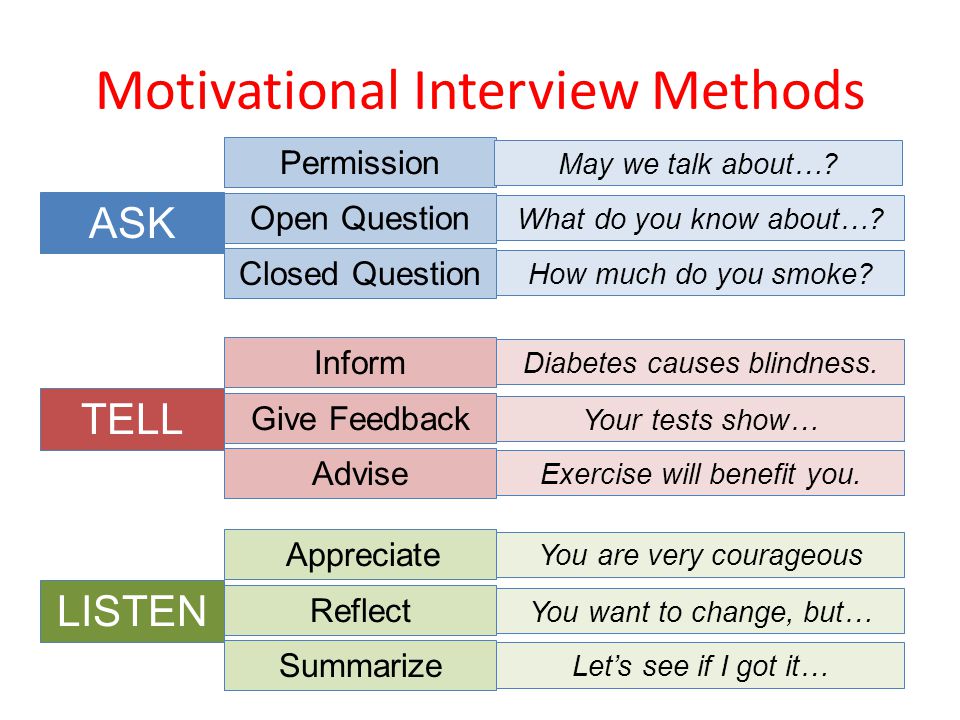

What is the OARS method?

The OARS method is a common way for motivational interviewers to ask questions and provide feedback. OARS stands for open questions, affirmations, reflective listening, and debriefing, and this technique encourages you to be open and honest about your feelings about your work. It also allows the interviewer to help you solve the problem you are struggling with. They ask questions about your situation that help you imagine possible outcomes and remember what makes you feel positive and motivated about your work. nine0003

nine0003

5 motivational interview questions with sample answers

Your answers to the motivational interview questions are individual to you. An honest answer is the key to achieving the goals of the interview. Here are some open-ended motivational interview questions with sample answers to help you prepare:

1. Can you tell me about a time you stayed motivated by doing repetitive work?

The STAR method can help you answer questions that are directly related to your work tasks. Although the interviewer asks this question to help them understand how you feel at work, STAR can help you clearly describe your work methodology. STAR means:

-

Situation: Providing background information to help make your answer understandable

-

Task: The specific duty or topic that your story is about.

-

Action: What did you do to resolve the situation

-

Result: The permission granted by your action.

Example: “I once had an assignment to manage a project to help implement a new policy. I needed to create goals and schedule and then supervise the team throughout the project. I've done this many times before and I didn't have the motivation. to complete it this time. Later, I realized that focusing on working with my team instead of working on specific tasks made the project a lot more enjoyable for me. By focusing on good work with my colleagues, I made sure we completed the project on time. time and helped implement the policy effectively.” nine0003

I needed to create goals and schedule and then supervise the team throughout the project. I've done this many times before and I didn't have the motivation. to complete it this time. Later, I realized that focusing on working with my team instead of working on specific tasks made the project a lot more enjoyable for me. By focusing on good work with my colleagues, I made sure we completed the project on time. time and helped implement the policy effectively.” nine0003

2. How do you define professional success for yourself?

During a motivational interview, it is important to remember that the main goal of the interviewer is to understand how you really feel about your career. If they ask what you think about success, consider being as honest as possible. If your definition of success now is different from when you started your career, it may help your interviewer understand you and your situation better.

Example: “When I started working as a social worker, I always felt that success was becoming a leader, and I made that my goal. I gave myself two years to achieve this goal, and in those two years I achieved a lot. and helped many people. Then I realized that I could help people more directly in my current role. So right now success is more like building a career helping my clients and making sure I can get them exactly what they need to be better.” nine0003

I gave myself two years to achieve this goal, and in those two years I achieved a lot. and helped many people. Then I realized that I could help people more directly in my current role. So right now success is more like building a career helping my clients and making sure I can get them exactly what they need to be better.” nine0003

Read more: Interview question: "How do you define success?"

3. Can you tell me about the work environment that makes you most productive?

When it comes to your work environment and productivity, it's good to have specific details in mind. The interviewer probably wants to know how you work best in order to help you find solutions that will enable you to become a better and more productive employee. Consider talking about details that will help you increase your productivity, such as the time of day, your mood, your colleagues, or specific tasks that will help you do your tasks better. nine0003

Example: “At some point, I realized that I was most productive when I had a deadline. Without a deadline, I can always find a reason to edit or change the report simply because I have time. I would have finished the report, but I “would have spent extra time on it, although the quality of the work remained the same. This time I can spend on other projects. Now, if I get assignments without a deadline or in the distant future, I set the deadlines myself "to increase my productivity." nine0003

Without a deadline, I can always find a reason to edit or change the report simply because I have time. I would have finished the report, but I “would have spent extra time on it, although the quality of the work remained the same. This time I can spend on other projects. Now, if I get assignments without a deadline or in the distant future, I set the deadlines myself "to increase my productivity." nine0003

4. Would you rather work in an ideal low-pay environment or a less-ideal high-pay environment?

Understanding your ideal work situation can help the interviewer know your motivations behind your job or job. This can help them ask more specific questions based on your answer, so they can determine which situation might be most helpful in boosting your happiness at work. When answering this question, consider being honest about how you prefer to work, even if it's different from your current work situation. nine0003

Example: “I used to work in different conditions. Although higher wages appeal to me, I have noticed that less than ideal conditions change my attitude towards work. It is much more beneficial for me to be proud of the work I do. do even if the pay is lower.

It is much more beneficial for me to be proud of the work I do. do even if the pay is lower.

5. Tell me about a time when you thought you were going to miss a deadline. How did you decide?

Motivational interviewers may ask about high stress moments at work. This can help them understand how you feel about those moments and how you deal with them. The STAR method can also help here because it will help you structure the story about a particular event to tell the interviewer. nine0003

Example: “I once had an article due at the end of the week, even though I had a full schedule of other tasks. I realized that some of these tasks have a higher priority than others. priority tasks first before moving on to the rest. After I created the schedule, I realized that I have time between tasks to work on the article a little at a time. This allowed me to complete all my tasks before the end of the week. ."

Most common motivational interview questions

Motivational interviewers ask open-ended questions that help you think critically about your work. This will help you review your current situation to find ways to improve it. Many of these questions require you to evaluate your work life. Other questions may require you to evaluate your emotional connection to your work and how this may affect you while you work.

This will help you review your current situation to find ways to improve it. Many of these questions require you to evaluate your work life. Other questions may require you to evaluate your emotional connection to your work and how this may affect you while you work.

Questions assessing your working life may include:

-

What is good about your job?

-

How would you improve your work?

-

What attempts have you already made to improve your situation?

-

How is your job different now than when you started?

-

Can you tell me more about what you do at work?

-

Has anything happened at work lately?

-

How can changing the way you work make a difference? nine0003

-

What were your goals in finding this job?

-

How have your goals changed?

-

How do your colleagues influence the way you work?

-

How would you describe your relationship with colleagues?

-

What changes will help you achieve your goals?

-

Can you tell me about a time when you had a great idea at work?

-

What do you do to effectively manage your time at work? nine0003

-

How has your job helped you become a better professional or personal person?

-

Could you describe a time when you discovered a new method or process for doing your job?

-

How do your managers help motivate you at work?

-

What do you think motivates you the most in your work?

Questions assessing your emotional connections and responses may include:

-

What brings you here today?

-

How can I help you feel more comfortable at work?

-

Why is your job important to you?

-

What attracted you to your profession?

-

What relaxation techniques have helped you in the past?

-

What happened before you started to treat your work this way?

-

What do you think will happen if you don't make changes? nine0003

-

How are you feeling as you make progress?

-

What is the best part of your day?

-

What makes you feel supported at work?

-

What have you done at work that you are proud of?

| Motivational interviewing | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Psychological counseling - Theory and practice nine0203 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Page 1 of 2 Addictions as a modern problem. Some currently known addictions are called “chemical addictions”; the object of addiction in this case is a psychoactive substance (PAS), with the need to take certain physiological symptoms (for example, addiction to alcohol, drugs, etc.

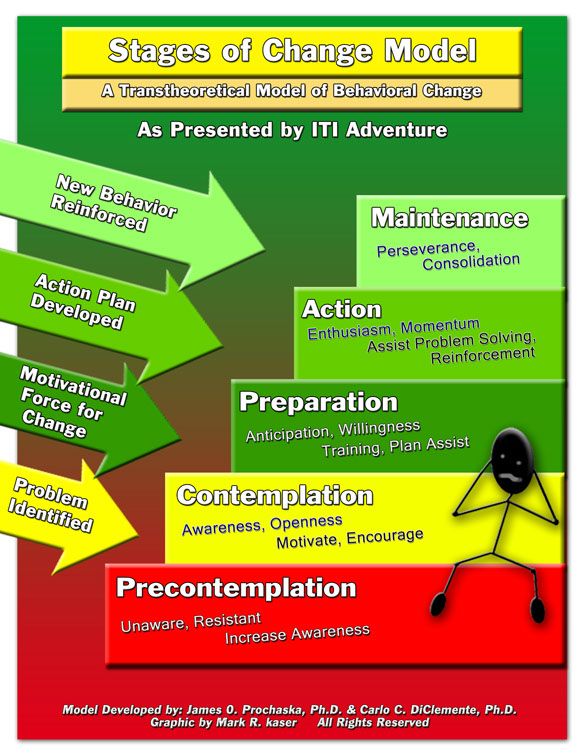

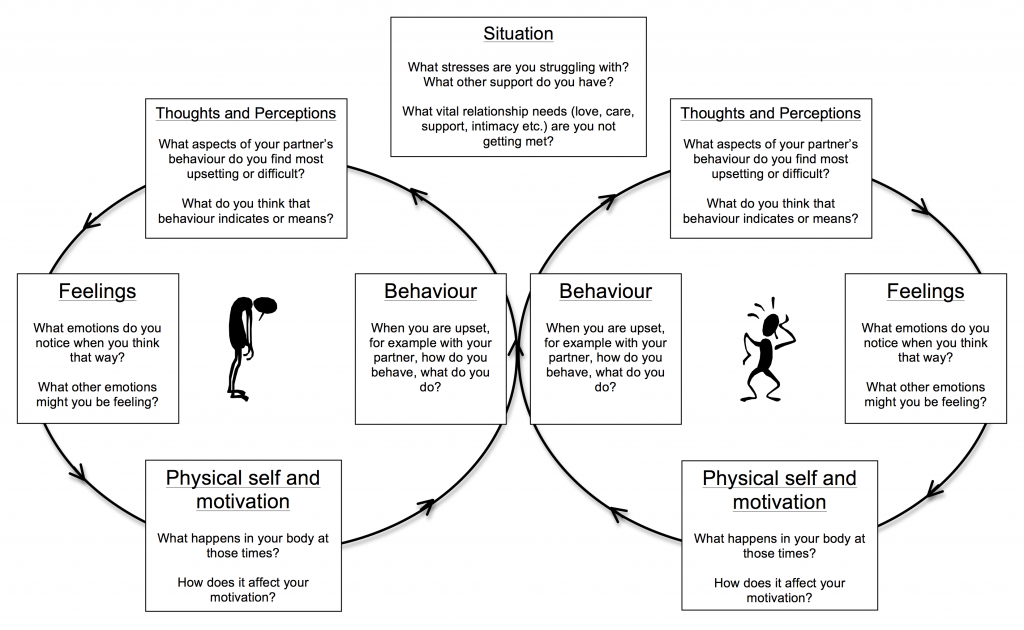

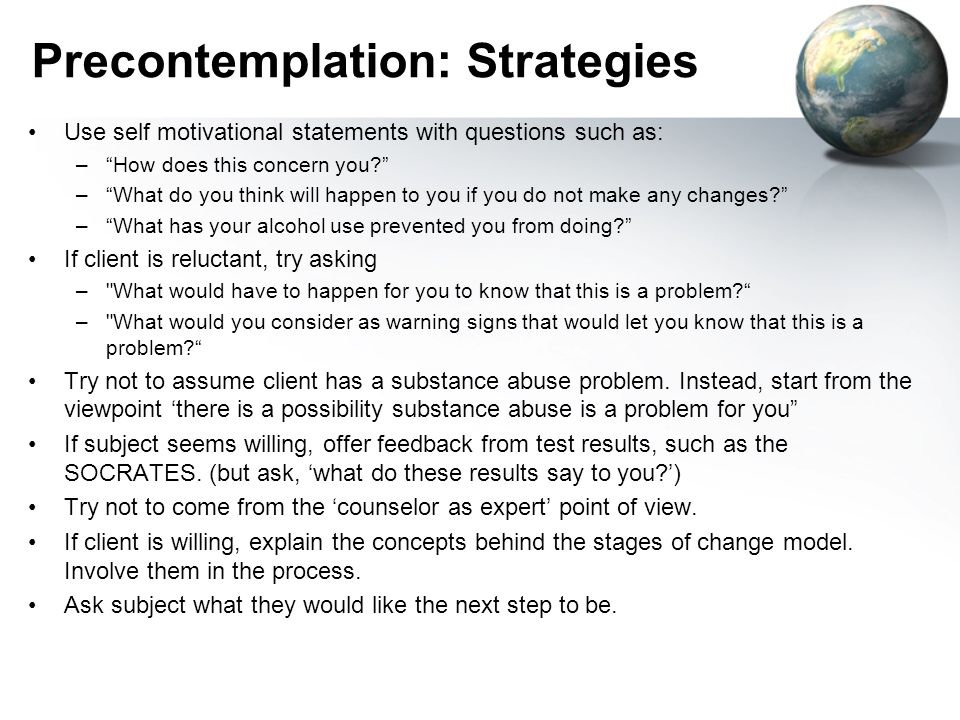

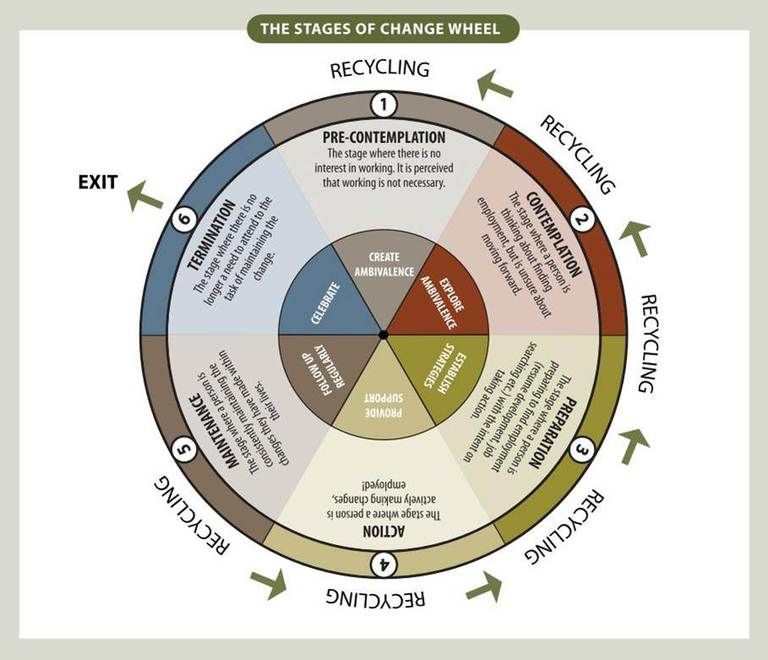

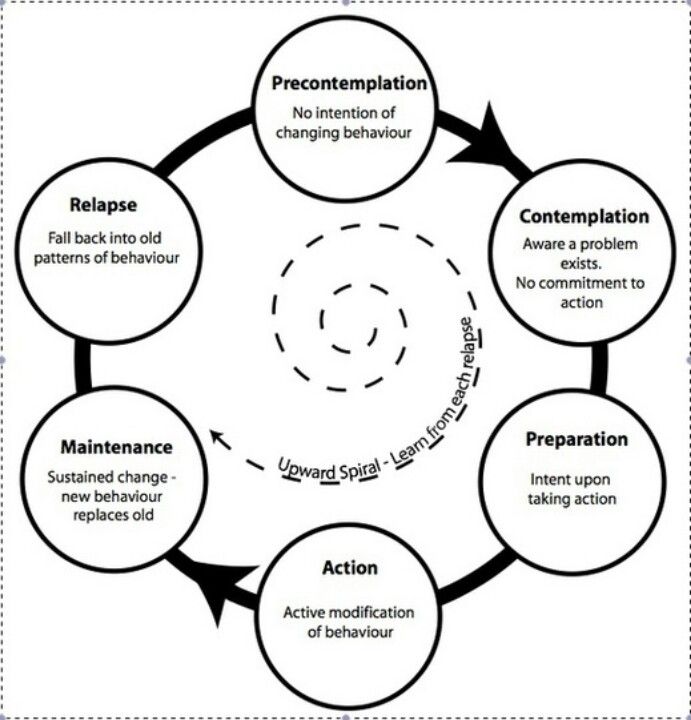

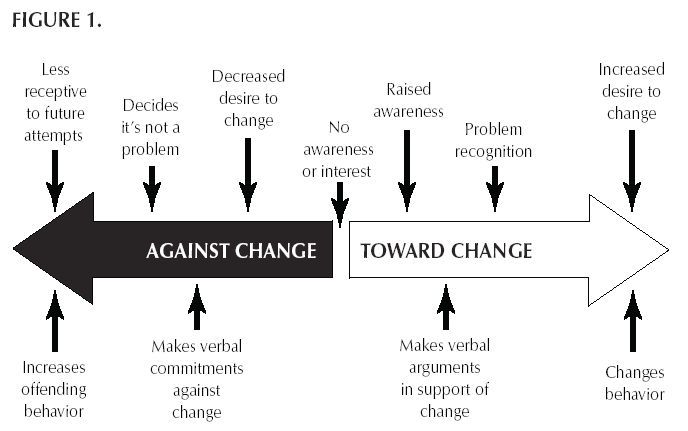

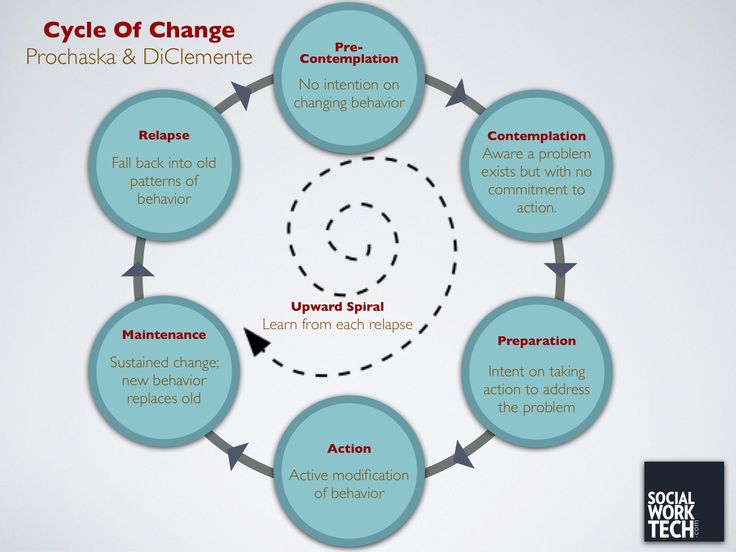

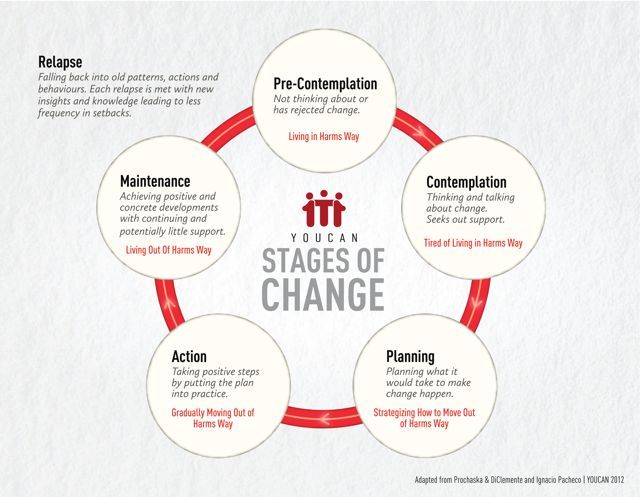

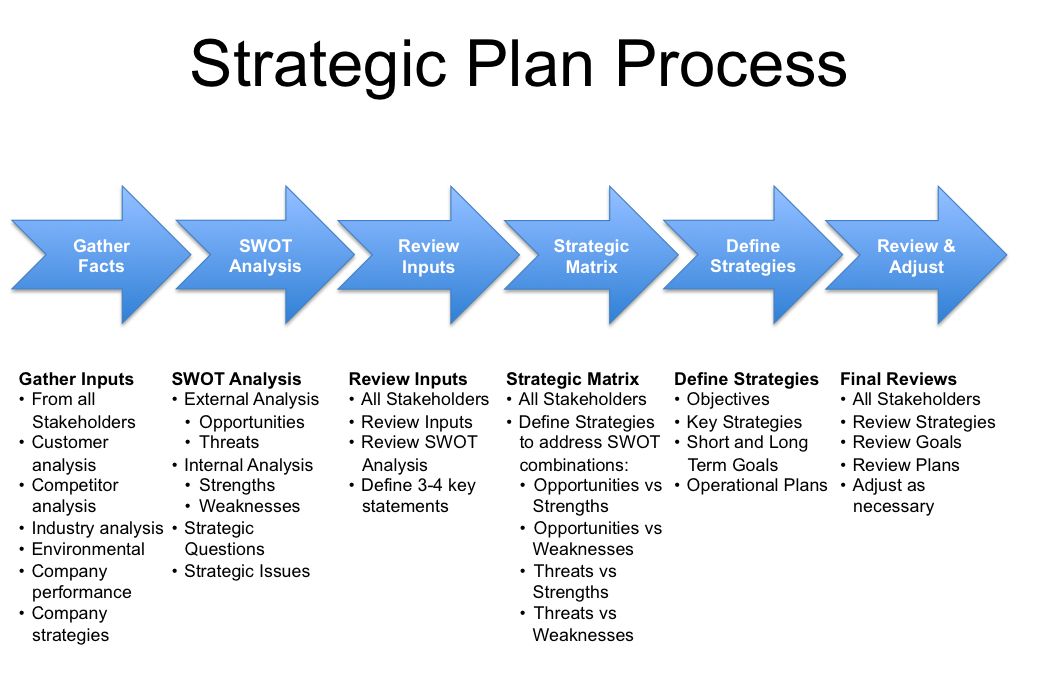

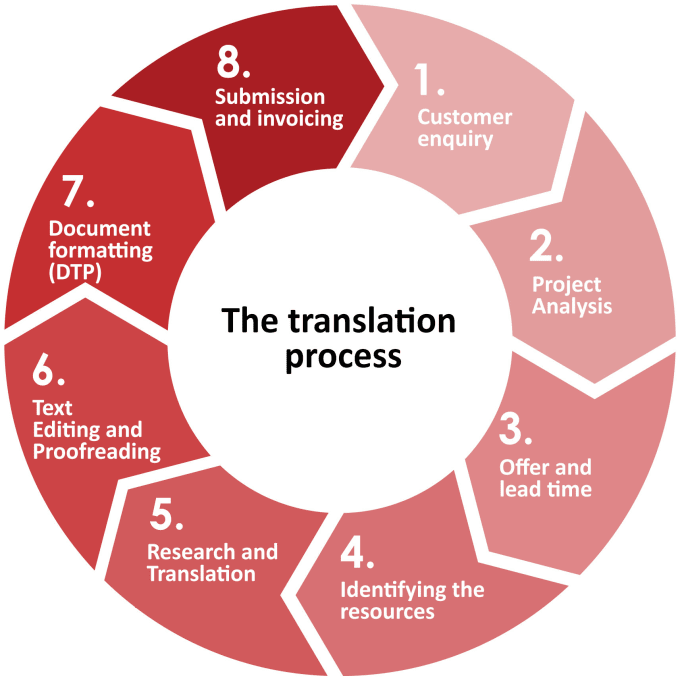

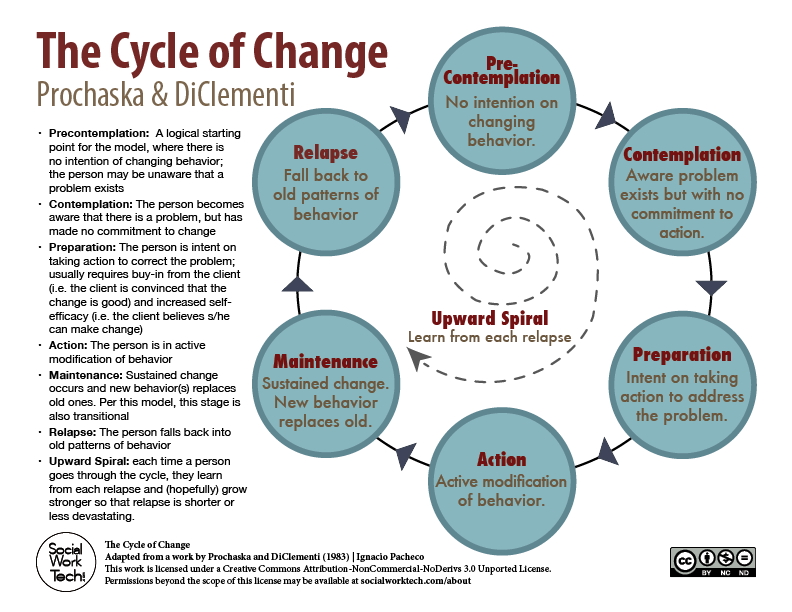

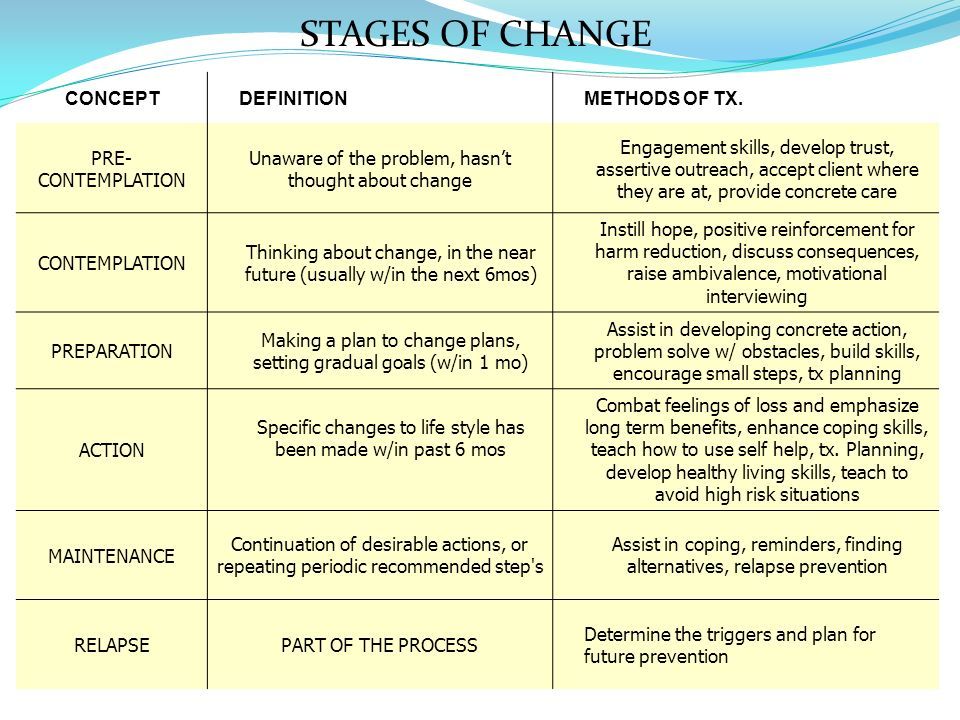

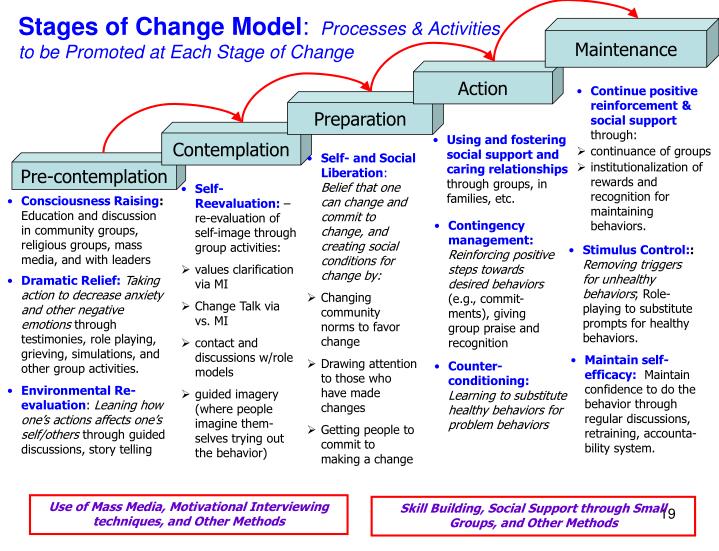

Motivational interviewing Motivational Interviewing (MI) was developed primarily as a method of psychological counseling for people who abuse alcohol but are not yet addicted. The theoretical basis of MI is the model of stages (stages) of readiness for change, developed by American psychologists James Prochaska and Carlo Di Clemente (J. Prochaska & C. DiCIemente) and first published in 1982. The approach proposed within the framework of this model defines a change in behavior not as a one-time event, but as a process that naturally proceeds through certain stages (stages). It is impossible to achieve real change in behavior without going through these stages in sequence. From one stage to another, the willingness to change grows. Movement in the direction of change and the transition from one stage to another is facilitated by factors that differ depending on the particular stage (stage). People at different stages of change require different incentives and types of support to move forward. At the same time, you can stay at each stage of changes for as long as you like, and returning to the original behavior after already achieved changes means sequentially going through all the stages again. Prethinking resistance to change People who are at this stage are not aware or do not want to be fully aware of the problem associated with their behavior. These people have no thoughts of changing behavior. Sometimes this is due to the absence of obvious and perceived harm from some behavior (for example, in a young smoker). and sometimes with demoralization, a feeling of powerlessness and the impossibility of change (for example, in an alcoholic with experience). Thinking about thinking about change People at this stage recognize the fact of the problem, realize it more or less fully. The person reflects on the potential for change. And may even imagine this change in the indefinite future. At this stage, people are able to think about the causes of the problem, postponing specific actions to solve it indefinitely (for example, many heavy smokers, people with malnutrition and overweight, alcohol abusers, etc.). For further movement towards change, it is necessary to focus not on the problem itself, but on its individual solution, not on the past, but on the future. nine0003 Decision making preparation for change The problem at this stage is fully recognized. A person makes a plan for change. Actual change It is at this stage that people not only realize the problem, but also take concrete steps to solve it (stop buying cigarettes, pour out the alcohol they have at home, go on a diet, etc.). This is the most stressful stage, requiring great strength, so it is advisable to plan its beginning for the period of the best possible form, both mental and physical. Save maintain change At this stage, the problem, once realized. may become largely irrelevant. The change, perhaps not permanent or permanent, does not allow for the full experience of the problem, and the effort expended on this change may seem excessive ("I hate to refuse beer when my neighbor treats me, what's wrong if I drink with him Especially since I don't have any more drinking scandals at home!))). Completion This is the final stage of behavior change. The problem finally loses its relevance, ceases to be a threat or a temptation. A person at this stage is firmly confident in changing his behavior and does not feel anxiety about a possible relapse. However, in some cases, at this stage, even after decades, people may still periodically feel cravings for the behavior that they got rid of (for example, drinking or smoking). nine0002 Cyclic spiral of change Unfortunately, it is extremely rare that the desired change in behavior occurs after a single consecutive passage through all stages. Such a linear advance in practice replaces the semblance of a spiral by advancing somewhat. people slide back into the initial stages (usually the stage of contemplation/thinking about change). How to determine the stage of readiness for change? There are different ways. Prochazka and Di Clemente offer the following questions to determine the stage of readiness / stage of change: Ambivalence From lat. ambo both and valentia strength. Self-efficacy The concept of self-efficacy as a belief in the success of one's actions, a positive assessment of one's own behavioral competence, was introduced by the American psychologist, the creator of the social cognitive direction, Albert Bandura. In a number of studies, Bandura showed that one of the causes of behavioral disorders may be a lack of faith in the effectiveness of one's own efforts. A person's subjective perception of his ability to act successfully in a given situation is the key to initiating action. At its core, self-efficacy is not a static characteristic, but a flexible variable that depends on a number of factors. Resistance Resistance always arises when the topic is important to a person and unpleasant for his self-esteem. Awareness of the destructive consequences of behavior (or simply the wrongness of one's own behavior) is unpleasant and naturally causes resistance. Essence of motivational interviewing Motivational interviewing was developed by American psychologists William Miller and Stefan Rollnick (W.R. Miller & S. Rollnick, 1991, 2002) as a practical consequence of the theoretical model of readiness for change. Basic Principles of Motivational Interviewing 1. The desire for change comes from the client and cannot be imposed on him from outside. There are aggressive motivational approaches based on coercion, persuasion, confrontation, and the use of external threats to pressure (for example, loss of a job, family, or health). The use of such threats can be effective in changing client behavior in the short term, but does not produce permanent results. MI is fundamentally different from such approaches and relies on the identification of actual unmet needs, the mobilization of internal resources and the client's own goals to stimulate behavior change. Motivational interviewing techniques By themselves, MI techniques do not represent anything complex or specific. Their use makes it possible to achieve a change in behavior with a correct understanding of the essence of MI.

Effectiveness of motivational interviewing MI has been shown to be effective in preventing and treating various types of addiction compared to other types of counseling. Accompanying clients with chemical addiction In terms of preventing unwanted effects, the safest way for clients with chemical dependence is to completely stop using drugs. Benefits of using motivational interviewing The use of MI ensures the development of a client's sense of responsibility and self-confidence, making it possible to regard counseling as a process of solving common tasks with a specialist, in which he takes an active position and makes decisions, and the specialist, for his part, appreciates his ideas and supports his undertakings . Literature |

Various forms of chemical and non-chemical addictions are widespread in the modern world and represent an urgent problem studied at the intersection of medicine, psychology and public health. nine0232 All addictions are characterized by specific psychological/mental symptoms:

Various forms of chemical and non-chemical addictions are widespread in the modern world and represent an urgent problem studied at the intersection of medicine, psychology and public health. nine0232 All addictions are characterized by specific psychological/mental symptoms:  ) are associated. Regarding others, it can be said that the object of addiction is a behavioral pattern; they are referred to in the literature as “behavioral addictions” (gambling, computer and Internet addictions, food addictions, shopaholism, etc.). nine0232 For a number of reasons (such as underestimation and denial of problems associated with addictive behavior, fear of social stigmatization, unwillingness to go to official medical institutions, etc.), people who are still developing addiction, as a rule, do not receive timely specialized help in first of all, diagnostic and consulting character. The role of a counseling psychologist at this stage can hardly be overestimated. Psychological intervention aimed at changing behavior can delay or even prevent the formation of addiction. nine0003

) are associated. Regarding others, it can be said that the object of addiction is a behavioral pattern; they are referred to in the literature as “behavioral addictions” (gambling, computer and Internet addictions, food addictions, shopaholism, etc.). nine0232 For a number of reasons (such as underestimation and denial of problems associated with addictive behavior, fear of social stigmatization, unwillingness to go to official medical institutions, etc.), people who are still developing addiction, as a rule, do not receive timely specialized help in first of all, diagnostic and consulting character. The role of a counseling psychologist at this stage can hardly be overestimated. Psychological intervention aimed at changing behavior can delay or even prevent the formation of addiction. nine0003  Subsequently, this method gained wide popularity both in the field of prevention and treatment of other addictions, and as a universal method of short-term psychological counseling and psychological and social support for various categories of clients. nine0232 The popularity and relevance of MI is related both to the simplicity and accessibility of this method, and the fact that MI is effective even in the case of single visits and in relation to those clients who do not seek help on their own (including unmotivated, negative or skeptical ).

Subsequently, this method gained wide popularity both in the field of prevention and treatment of other addictions, and as a universal method of short-term psychological counseling and psychological and social support for various categories of clients. nine0232 The popularity and relevance of MI is related both to the simplicity and accessibility of this method, and the fact that MI is effective even in the case of single visits and in relation to those clients who do not seek help on their own (including unmotivated, negative or skeptical ).

nine0232 The idea of certain stages of change turned out to be very simple, logical and intuitive for most of us. Having analyzed his own experience of changes, he will find these stages and easily characterize the readiness for changes corresponding to each stage.

nine0232 The idea of certain stages of change turned out to be very simple, logical and intuitive for most of us. Having analyzed his own experience of changes, he will find these stages and easily characterize the readiness for changes corresponding to each stage.  At this stage, informing about the individual risk of maintaining existing behavior and the individual benefit of change works to further move and initiate the process of change. nine0003

At this stage, informing about the individual risk of maintaining existing behavior and the individual benefit of change works to further move and initiate the process of change. nine0003  And even appoints a specific date for the start of its implementation (“from Monday”, “next month)”, “after the holidays)) etc.). However, real actions do not begin in any way and are pushed further and further away. Or they start, but immediately stop under some pretext (“I quit, but started smoking again because of trouble at work)”, “I decided to stop drinking, but I was invited to a party I’ll quit later)) etc.). At this stage, a thorough elaboration of the goal (complete failure or reduction to a certain level) and the development of criteria for achieving it (what exactly should be the results and for how long) will help to move on. nine0003

And even appoints a specific date for the start of its implementation (“from Monday”, “next month)”, “after the holidays)) etc.). However, real actions do not begin in any way and are pushed further and further away. Or they start, but immediately stop under some pretext (“I quit, but started smoking again because of trouble at work)”, “I decided to stop drinking, but I was invited to a party I’ll quit later)) etc.). At this stage, a thorough elaboration of the goal (complete failure or reduction to a certain level) and the development of criteria for achieving it (what exactly should be the results and for how long) will help to move on. nine0003  At this stage, changes become visible to others, and people at first encounter a keen interest in their changes, with congratulations and questions. However, the interest of others quickly dries up, and with it the positive reinforcement. It is important to understand that this stage is not the final one in the process of change. It is not only persistent adherence to the plan that contributes to further progress and the achievement of real change, but also analysis and problem solving. resulting from changes (“How do I explain to my friends that I don’t have to drink at parties?))), the search for social support and positive reinforcement. nine0003

At this stage, changes become visible to others, and people at first encounter a keen interest in their changes, with congratulations and questions. However, the interest of others quickly dries up, and with it the positive reinforcement. It is important to understand that this stage is not the final one in the process of change. It is not only persistent adherence to the plan that contributes to further progress and the achievement of real change, but also analysis and problem solving. resulting from changes (“How do I explain to my friends that I don’t have to drink at parties?))), the search for social support and positive reinforcement. nine0003  Focusing on change, keeping it in the focus of daily interests, perseverance and consistency will allow you to move forward at this stage and achieve change. nine0003

Focusing on change, keeping it in the focus of daily interests, perseverance and consistency will allow you to move forward at this stage and achieve change. nine0003  11o the experience gained in change allows, although returning to the initial stage, but already at a new level, more prepared for change, better understanding the reasons for failure and the path to success. Negative feelings of anger, impotence, confusion, shame, guilt, etc., which naturally arise after a breakdown or relapse, hinder progress, but do not mean the impossibility of achieving change, as does the fact of relapse itself. Psychological support in the process of change makes it easier to overcome despair and the desire to give up. We’ll find out exactly how by taking a closer look at motivational interviewing. nine0003

11o the experience gained in change allows, although returning to the initial stage, but already at a new level, more prepared for change, better understanding the reasons for failure and the path to success. Negative feelings of anger, impotence, confusion, shame, guilt, etc., which naturally arise after a breakdown or relapse, hinder progress, but do not mean the impossibility of achieving change, as does the fact of relapse itself. Psychological support in the process of change makes it easier to overcome despair and the desire to give up. We’ll find out exactly how by taking a closer look at motivational interviewing. nine0003  ..?

..?  ..”).

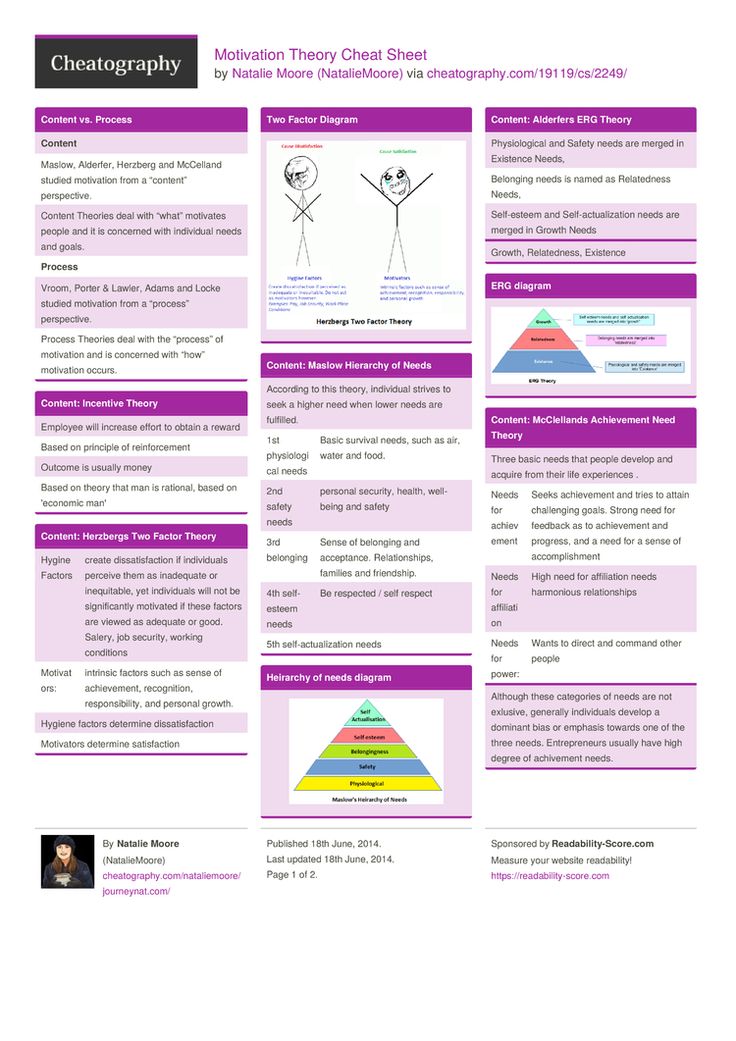

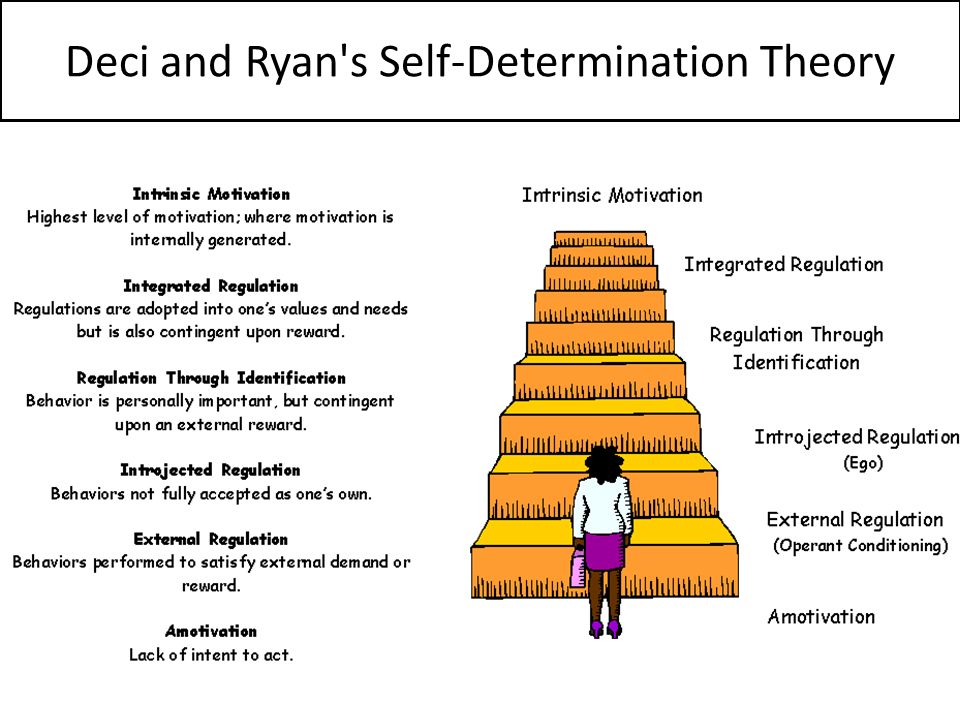

..”).  nine0232 Main factors influencing self-efficacy:

nine0232 Main factors influencing self-efficacy:  nine0232 Resistance is a response to an interaction situation perceived as threatening ("I don't want to talk about drinking because I don't want to be thought of as an alcoholic!"). The growing threat and the inability to avoid the situation activate the mechanisms of psychological defense and increase resistance

nine0232 Resistance is a response to an interaction situation perceived as threatening ("I don't want to talk about drinking because I don't want to be thought of as an alcoholic!"). The growing threat and the inability to avoid the situation activate the mechanisms of psychological defense and increase resistance  Initially, the use of MI was limited to counseling people whose alcohol consumption reached levels dangerous to health, but was not an addiction. Subsequently, the scope of MI has expanded significantly, including in counseling patients with addictions, both chemical and non-chemical (behavioral addictions). nine0232 W. Miller and S. Rollnick define MI as a directive, client-oriented method of counseling aimed at changing the client's behavior through analysis and resolution of contradictions (ambivalence). Unlike non-directive approaches in counseling, MI has a specific structure and a deterministic goal (behavior change). Unlike other directive approaches, MI does not allow pressure on the client, coercion, direct persuasion with an emphasis on professional authority, advice from a specialist, the imposition of diagnostic labels and results that the client should achieve. nine0232 As defined by its creators, MI represents a methodical approach, a style of interpersonal communication that strictly maintains a balance of guiding and client-oriented components, united by a philosophical concept and understanding of the mechanisms that trigger change.

Initially, the use of MI was limited to counseling people whose alcohol consumption reached levels dangerous to health, but was not an addiction. Subsequently, the scope of MI has expanded significantly, including in counseling patients with addictions, both chemical and non-chemical (behavioral addictions). nine0232 W. Miller and S. Rollnick define MI as a directive, client-oriented method of counseling aimed at changing the client's behavior through analysis and resolution of contradictions (ambivalence). Unlike non-directive approaches in counseling, MI has a specific structure and a deterministic goal (behavior change). Unlike other directive approaches, MI does not allow pressure on the client, coercion, direct persuasion with an emphasis on professional authority, advice from a specialist, the imposition of diagnostic labels and results that the client should achieve. nine0232 As defined by its creators, MI represents a methodical approach, a style of interpersonal communication that strictly maintains a balance of guiding and client-oriented components, united by a philosophical concept and understanding of the mechanisms that trigger change.

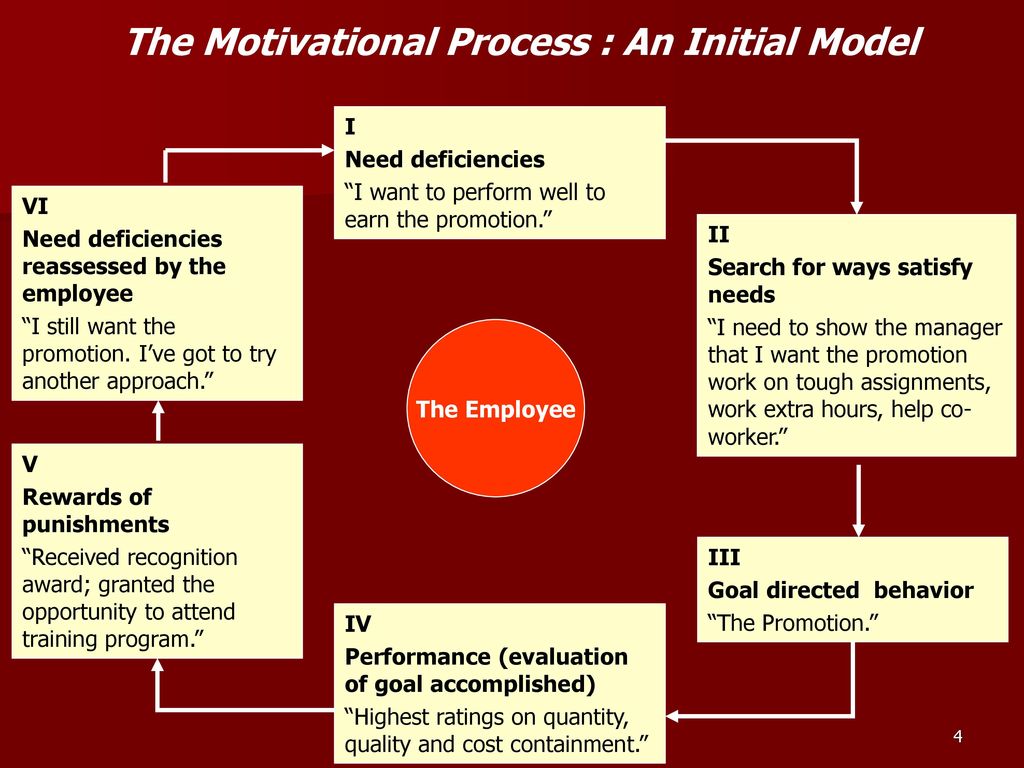

nine0232 2. Only the client himself (and not the specialist) can formulate and resolve his ambivalence. Ambivalence reflects the conflict between two unmet needs, as well as behaviors aimed at satisfying these needs. Each line of behavior has positive and negative aspects perceived by the client. Sequential analysis of confusing, conflicting needs is a tool by which clients learn to better understand themselves and their behavior. The task of the MI practitioner is to assist the client in this analysis and to guide him in making those decisions that promote change. nine0232 3. Direct persuasion is an inefficient way to resolve conflicts. In dealing with problem behavior, it is tempting for the therapist to “help” the client by convincing him of the seriousness of the problem, the danger of the situation, and describing the benefits of changing the behavior. Such actions are unacceptable within the framework of MI, as they increase resistance and suppress the client's own will.

nine0232 2. Only the client himself (and not the specialist) can formulate and resolve his ambivalence. Ambivalence reflects the conflict between two unmet needs, as well as behaviors aimed at satisfying these needs. Each line of behavior has positive and negative aspects perceived by the client. Sequential analysis of confusing, conflicting needs is a tool by which clients learn to better understand themselves and their behavior. The task of the MI practitioner is to assist the client in this analysis and to guide him in making those decisions that promote change. nine0232 3. Direct persuasion is an inefficient way to resolve conflicts. In dealing with problem behavior, it is tempting for the therapist to “help” the client by convincing him of the seriousness of the problem, the danger of the situation, and describing the benefits of changing the behavior. Such actions are unacceptable within the framework of MI, as they increase resistance and suppress the client's own will.  The general tone of MI is calm and revealing (ie aimed at getting the client information about himself). Persuasion

The general tone of MI is calm and revealing (ie aimed at getting the client information about himself). Persuasion  Therefore, the specialist conducting MI should pay special attention to all manifestations of motivation or counter-motivation (resistance) of the client. The increasing resistance of the client during the MI testifies that the specialist incorrectly assessed the client's readiness for change. Resistance can be reduced as a result of the correct actions of a specialist (“following the wave”). nine0232 7. The relationship between a specialist and a client is a partnership, excluding vertical interaction "expert performer". In the spirit of MI, the practitioner respects the client's free will and choice regarding their own behavior. The client's self-efficacy, his belief in his own strength and rightness are an independent value for a specialist using MI.

Therefore, the specialist conducting MI should pay special attention to all manifestations of motivation or counter-motivation (resistance) of the client. The increasing resistance of the client during the MI testifies that the specialist incorrectly assessed the client's readiness for change. Resistance can be reduced as a result of the correct actions of a specialist (“following the wave”). nine0232 7. The relationship between a specialist and a client is a partnership, excluding vertical interaction "expert performer". In the spirit of MI, the practitioner respects the client's free will and choice regarding their own behavior. The client's self-efficacy, his belief in his own strength and rightness are an independent value for a specialist using MI.  nine0003

nine0003  To avoid increasing resistance, medical information about individual risks or harms should be presented in a manner that is as objective as possible, without intimidation; indicating the source of the data; avoiding categorical; giving the patient the opportunity to determine the treatment strategy. The individual (subjective) significance of information is extremely important, and not general words (“drinking is harmful”). nine0232 Structuring information. Generalizing statements of a specialist are needed in order to structure and organize the information received from the client. Generalization is confirmation that the specialist listens and understands the client.

To avoid increasing resistance, medical information about individual risks or harms should be presented in a manner that is as objective as possible, without intimidation; indicating the source of the data; avoiding categorical; giving the patient the opportunity to determine the treatment strategy. The individual (subjective) significance of information is extremely important, and not general words (“drinking is harmful”). nine0232 Structuring information. Generalizing statements of a specialist are needed in order to structure and organize the information received from the client. Generalization is confirmation that the specialist listens and understands the client.  nine0232 MI sequence.

nine0232 MI sequence.

Evaluation of the effectiveness of MI is based on the data of scientific studies conducted in compliance with the principles of evidence. More information, data, and findings from the meta-analyses below can be found at pubmed.com. nine0232 Meta-analysis by Hattem et al. (Hettem et al., 2005) includes 72 clinical studies using MI, 31 of which are on problems with alcohol use. The results show a wide variation in the effectiveness of MI depending on the conditions of the study and the sample.

Evaluation of the effectiveness of MI is based on the data of scientific studies conducted in compliance with the principles of evidence. More information, data, and findings from the meta-analyses below can be found at pubmed.com. nine0232 Meta-analysis by Hattem et al. (Hettem et al., 2005) includes 72 clinical studies using MI, 31 of which are on problems with alcohol use. The results show a wide variation in the effectiveness of MI depending on the conditions of the study and the sample.  MI has been shown to be more effective than short-term methods such as directive confrontational counseling, educational intervention, social skills counseling, etc.

MI has been shown to be more effective than short-term methods such as directive confrontational counseling, educational intervention, social skills counseling, etc.  Efficiency varies depending on the period. Further studies are required to more confidently assess the effect of MI. nine0003

Efficiency varies depending on the period. Further studies are required to more confidently assess the effect of MI. nine0003  the specialist is ready to follow the goal of treatment that the client chooses for himself, and equally supports the client’s decision to completely abandon the use of psychoactive substances as well. and the decision to reduce the use of surfactants. nine0232 It is important that the practitioner refrains from judging, disapproving, negatively evaluating the client's goal of treatment and supporting any positive change in the client's substance use.

the specialist is ready to follow the goal of treatment that the client chooses for himself, and equally supports the client’s decision to completely abandon the use of psychoactive substances as well. and the decision to reduce the use of surfactants. nine0232 It is important that the practitioner refrains from judging, disapproving, negatively evaluating the client's goal of treatment and supporting any positive change in the client's substance use.

AFEW. Kyiv. 2004.

AFEW. Kyiv. 2004.