Middle functioning autism

The 3 Levels of Autism Explained

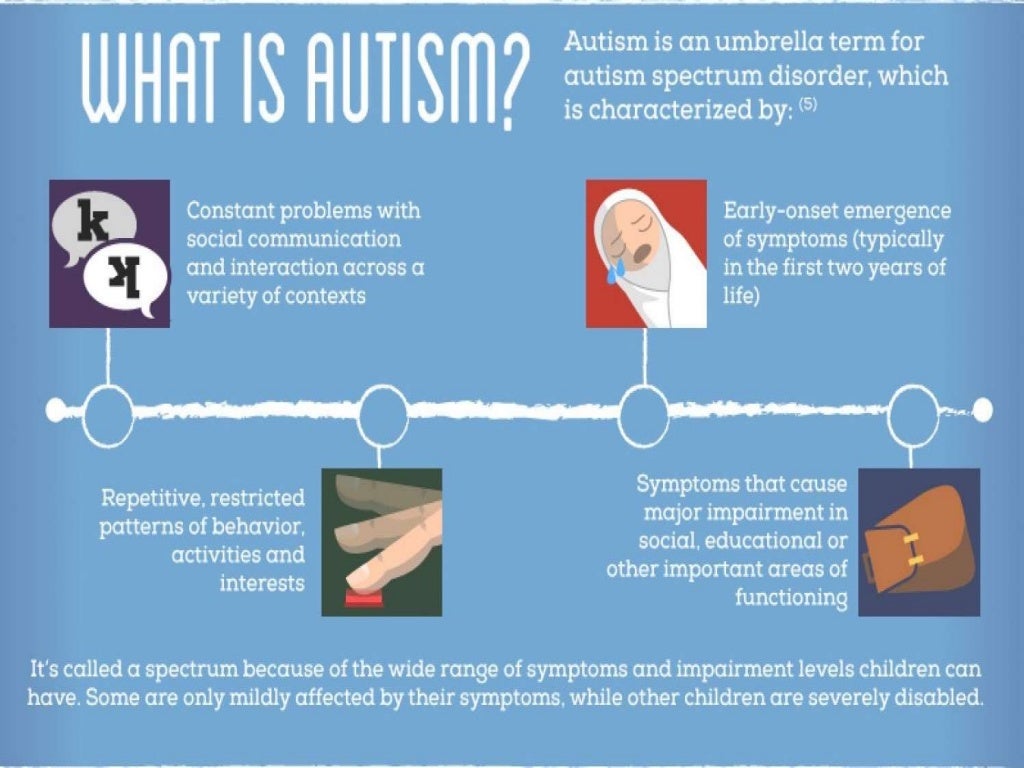

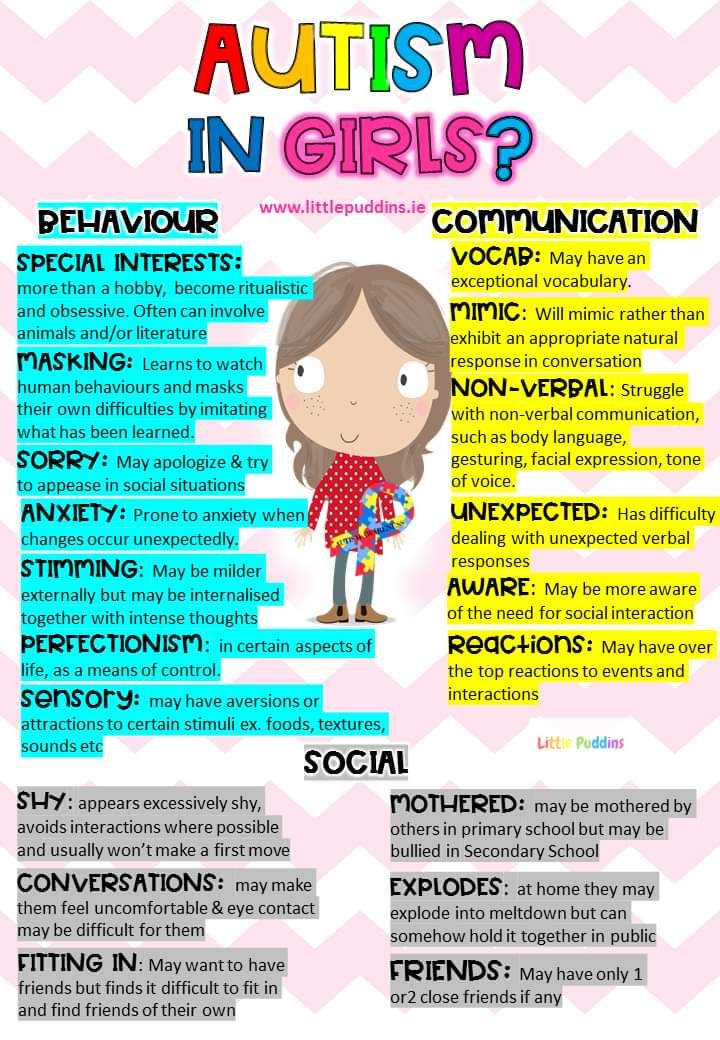

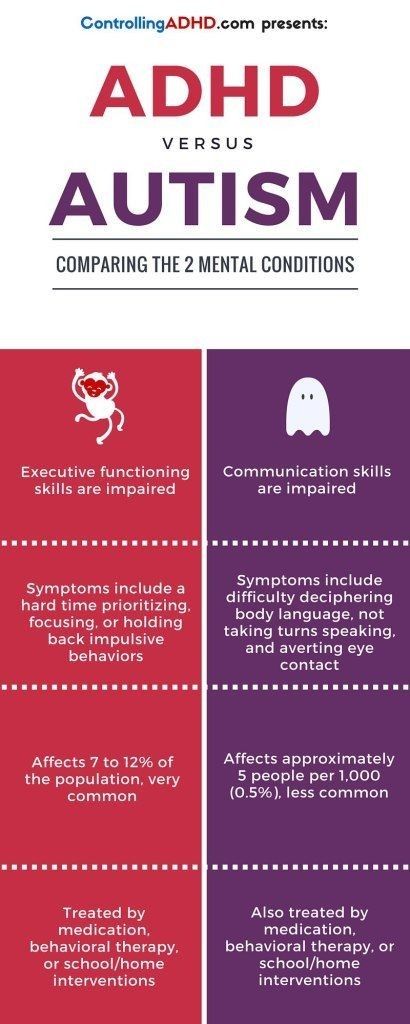

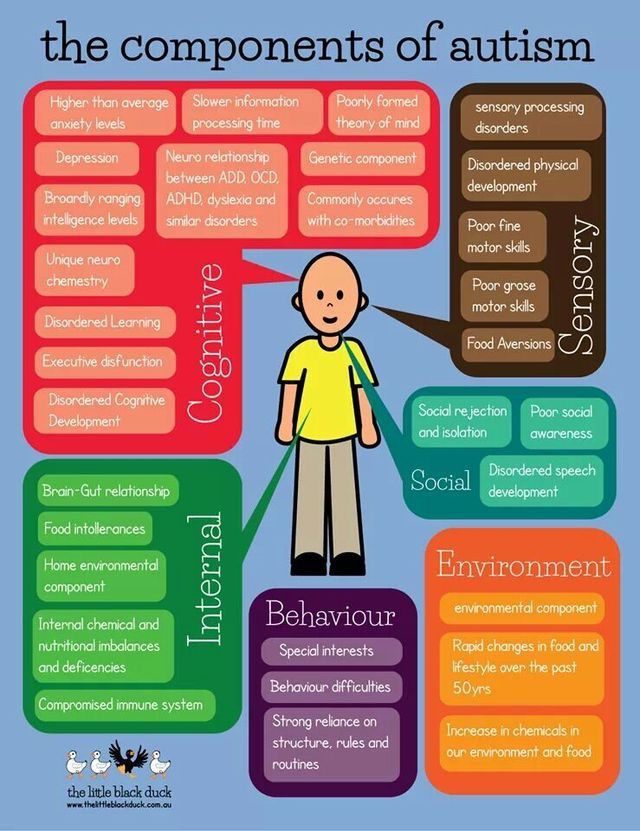

Autism is a diagnosis that often carries a certain connotation. Those who are unfamiliar with the nuances of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may assume that all children on the spectrum participate in repetitive behaviors, don’t make eye contact, and are largely non-verbal. While these signs can certainly be present, there are many children who fall within the spectrum whose symptoms are far milder and even those whose symptoms are more severe. It’s a wide and diverse range of possible complications, and despite what some may think, children within the spectrum do not all fall into neat little categories. For that reason, the classifications of ASD have changed significantly over the years.

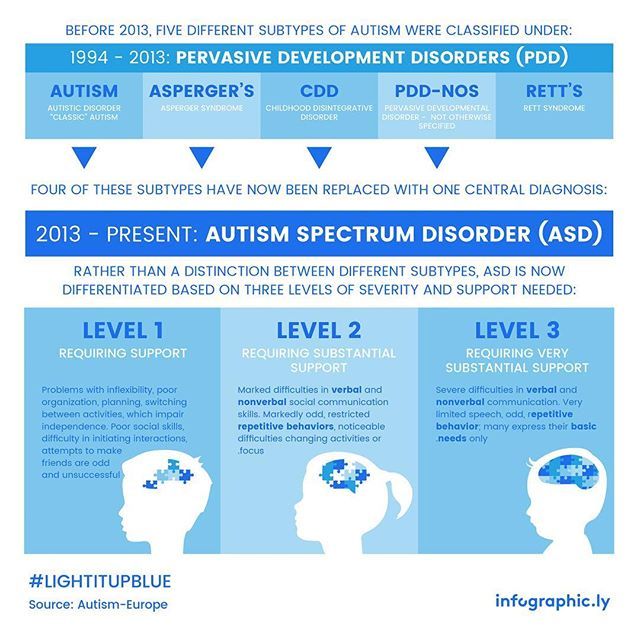

Previous Autism Spectrum Disorder TerminologyMuch of the misconception surrounding ASD comes from terminology that was used prior to 2013. In this prior classification system, children fell into one of the following three categories:

- Autistic Disorder – More severe cases of ASD were previously classified as autistic disorder.

The condition was often defined by communication troubles, repetitive behaviors, and social challenges among other symptoms.

- Asperger’s Syndrome – On the opposite end of the spectrum was Asperger’s syndrome which was characterized by milder symptoms which may impact an individual’s communication or social skills.

- Pervasive Development Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) – For children who fell in the middle and didn’t fully meet the requirements for either autistic disorder or Asperger’s, a diagnosis of PDD-NOS was often given.

While the old system of classification may seem a little more cut-and-dried, the subtle differences that often distinguished one from the other left room for a lot of confusion and much was open to interpretation. To address this, ASD is now categorized into three different levels, indicating what level of support a patient may need.

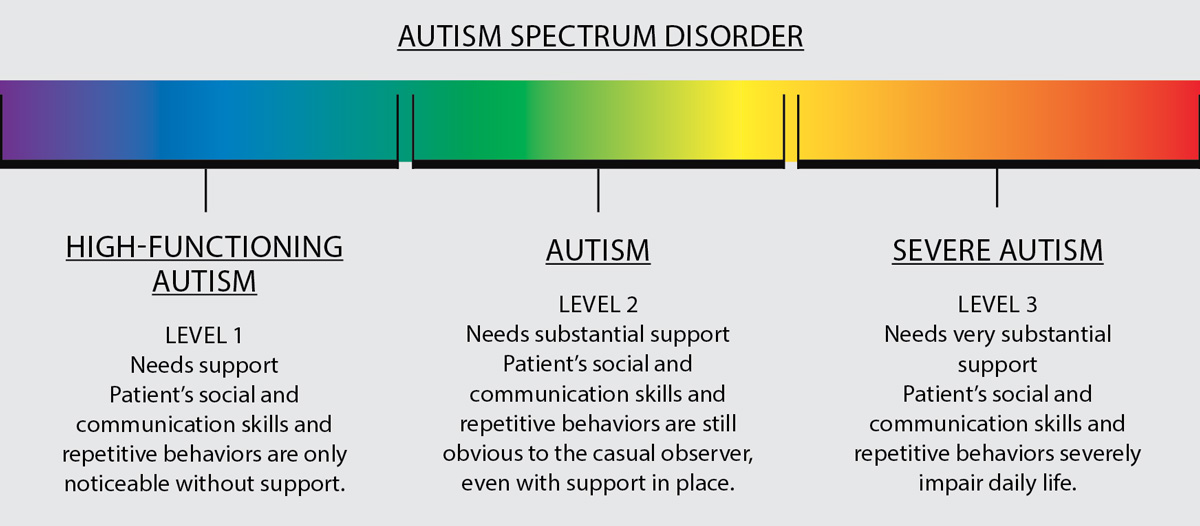

- ASD Level 1 – Level 1 ASD is currently the lowest classification. Those on this level will require some support to help with issues like inhibited social interaction and lack of organization and planning skills.

- ASD Level 2 – In the mid-range of ASD is Level 2. In this level, individuals require substantial support and have problems that are more readily obvious to others. These issues may be trouble with verbal communication, having very restricted interests, and exhibiting frequent, repetitive behaviors.

- ASD Level 3 – On the most severe end of the spectrum is Level 3 which requires very substantial support. Signs associated with both Level 1 and Level 2 are still present but are far more severe and accompanied by other complications as well. Individuals at this level will have limited ability to communicate and interact socially with others.

Parents of a child with suspected or diagnosed ASD need the support of a knowledgeable and understanding pediatrician. At Lane Pediatrics, our physicians fit the bill with experienced, compassionate, and comprehensive care. Learn more about them and our pediatric services by clicking below.

At Lane Pediatrics, our physicians fit the bill with experienced, compassionate, and comprehensive care. Learn more about them and our pediatric services by clicking below.

The 3 Levels of Autism: Symptoms and Support Needs

Three levels of autism exist to clarify the amount of support an autistic person might want or need.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental difference that can appear in many forms.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) outlines diagnostic criteria based on functioning in two domains:

- social communication

- restricted interests/repetitive behaviors

These criteria state that autistic people sometimes benefit from support, but there’s a wide range of differences in support needs.

Some autistic people are fluent conversationalists and might want only occasional help interpreting social cues or unpacking issues in therapy. Others get stuck and frustrated by social or functional roadblocks if they haven’t had regular coaching in relevant skill areas.

And some are nonspeaking, highly sensitive to sensory input, and communicate with emotional and behavioral outbursts when their needs aren’t recognized or met. They may use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) tools like picture symbols or electronic devices to express their thoughts and may benefit from support in multiple areas.

When diagnosing the condition, doctors assign levels of autism to help the person get the amount of support that’s right for them.

A person can also have different levels across the two domains — for example, someone might have level 1 autism for social communication and level 2 for restricted/repetitive behaviors. Each of those criteria has its own degree of support.

A person with level 1 autism requires the least amount of support.

Level 1 social communication characteristics may include:

- trouble understanding or complying with social conventions

- the appearance of disinterest in social interactions

- some emotional or sensory dysregulation

Level 1 restricted interests and repetitive behavior traits can be:

- a need for additional personal organization strategies

- behavioral rigidity and inflexibility

- stress during transitions

- attention span differences

- perseveration (focusing on something longer than is helpful)

An autistic person at level 1 in social communication might want therapy or coaching to enable them to navigate social nuances. Therapy for level 1 restricted and repetitive behaviors can help an autistic person learn self-regulation strategies.

Therapy for level 1 restricted and repetitive behaviors can help an autistic person learn self-regulation strategies.

At school, they can benefit from accommodations like extra time for tests and intermittent support from an education assistant (EA).

An autistic person who meets the level 2 criteria in either category has similar characteristics as those in level 1 but to a greater extent.

Social communication traits at level 2 may include:

- using fewer words or noticeably different speech

- missing nonverbal communication cues like facial expressions

- exhibiting atypical social behavior, like not responding or walking away during a conversation

Restricted interests and repetitive behavior traits at level 2 might resemble:

- a high interest in specific topics

- noticeable distress when dealing with change or disruption

An autistic person at level 2 might need school accommodations like scribing or reading support, as well as an EA nearby to help with social interactions during recess and lunch breaks.

They may also have schoolwork adapted to their level and be part of a social skills group. While in high school they might participate in an off-campus job training program.

Outside school, an autistic person at level 2 might benefit from activities such as:

- speech therapy

- occupational therapy

- social skills coaching

- applied behavior analysis (ABA) therapy

An autistic person assessed as level 3 in either social communication or restricted/repetitive behaviors will need the most support and seem noticeably different at a young age.

Level 3 social communication means the person may:

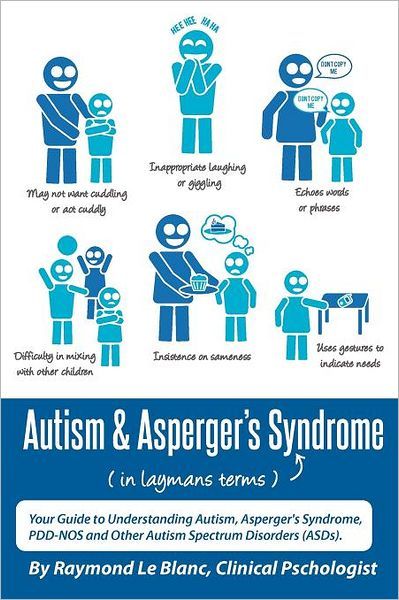

- be nonspeaking or have echolalia (repeating words or phrases they hear)

- prefer solitary activities

- interact with others only to meet an immediate need

- seem unable to share imaginative play with peers

- demonstrate a limited interest in friendships

If they are at level 3 for restricted/repetitive behaviors, they might:

- engage in repetitive physical behaviors like rocking, blinking, or spinning in circles

- express extreme distress when asked to switch tasks or focus

Support for level 3 autism includes the same therapies as level 2, but at a more comprehensive level and with greater scheduling frequency. People with this level of autism might use AAC, like a speech-generating device or Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS).

People with this level of autism might use AAC, like a speech-generating device or Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS).

Education accommodations include one-on-one time with an EA, a separate education setting like a resource room, and modified level-specific activities. In high school, they might be in a specialized program learning functional literacy and numeracy, as well as life skills.

Before the DSM-5 was published, autism was one of several diagnoses listed under the category of pervasive developmental disorders (PDD). This has since changed.

In the DSM-5 and DSM-5-TR, four of the previous PDD diagnoses are now included in the category of autism spectrum disorder:

- Asperger’s syndrome

- pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS)

- autistic disorder

- childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD)

A fifth diagnosis formerly in the PDD category is Rett syndrome, which is not considered a type of autism.

Asperger’s syndrome

You may have heard the term Asperger’s syndrome (AS) or “Aspie” in relation to autism.

People diagnosed with AS have autistic traits, plus two defining characteristics:

- typical language development

- average to above-average intelligence

The DSM-5 and DSM-5-TR no longer use the term Asperger’s syndrome. It’s an outdated diagnosis from the DSM-4. You might still hear people refer to themselves or the autistic people in their lives as Aspies or having AS, if they were identified before the arrival of the DSM-5 in 2013.

PDD-NOS

Pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) is another outdated DSM-IV diagnosis that has since been included as part of ASD in the DSM-5.

People diagnosed with PDD-NOS have significant impairments in communication and noticeable repetitive behaviors and restricted interests. They may also experience a delay in language development or live with an intellectual disability.

However, symptoms aren’t severe enough or don’t appear early enough in life, to meet the criteria for what was previously known as autistic disorder.

Autistic disorder

Also from the DSM-4, autistic disorder is the term previously used to describe autism resulting in comprehensive support needs. People diagnosed with autistic disorder have similar symptoms as those with PDD-NOS but these symptoms are more pronounced.

Childhood disintegrative disorder

According to a 2017 study, childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD) is a rare form of autism characterized by developmental regression resulting in severe autism with intellectual disability.

Although more research is needed, the study found evidence of neurobiological differences between people with CDD and other forms of autism.

Rett syndrome

Rett syndrome results in some autistic-like traits and was previously included in the PDD category. However, researchers have since discovered that Rett syndrome results from a genetic mutation, so they no longer considered it a type of autism.

Autism is categorized into different levels based on the amount of support an autistic person might need.

The DSM-5 and DSM-5-TR include three levels of support needs for autism spectrum disorder. The previous DSM-4 categorized autism as separate diagnoses of Asperger’s syndrome, PDD-NOS, autistic disorder, and CDD.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has an autism information page with links to resources. You can also visit Psych Central’s autism hub for more information and resources.

What does "high-functioning" or "low-functioning" autism mean, and are these terms necessary?

04/08/16

Terms such as "low functioning" are often used to describe people with autism, but they can be misleading and create negative attitudes towards people. Research into everyday life helps build a better understanding of people with autism

Author: Nicholette Zeladt

Source: Spectrum News

Alex Garish does a great job on stage. An 11-year-old girl flies into the dining room of her Montreal home, her arms outstretched like the wings of an airplane, her arrival buzzing. She leans over and makes a sharp U-turn just before landing softly on the wicker chair in front of the computer. A few strokes of her fingers, and she turns on a cartoon about circles, squares and other geometric shapes and forgets about everything in the world. Only from time to time she looks back at the guest sitting at the table behind her. nine0003

An 11-year-old girl flies into the dining room of her Montreal home, her arms outstretched like the wings of an airplane, her arrival buzzing. She leans over and makes a sharp U-turn just before landing softly on the wicker chair in front of the computer. A few strokes of her fingers, and she turns on a cartoon about circles, squares and other geometric shapes and forgets about everything in the world. Only from time to time she looks back at the guest sitting at the table behind her. nine0003

Alex was diagnosed with autism at the age of 2 and did not speak until she was 4 years old. Now she only speaks simple phrases of two or three words. Standardized tests show that she has a mild degree of mental retardation. She has trouble using the toilet and washing herself. She does not know how to tell the time by the clock, she cannot cross the road herself. If she is upset, she becomes hysterical, throws objects or throws herself on the floor. nine0003

Across the St. Lawrence River in Montreal is John Walsh, a 13-year-old boy who was diagnosed with autism at age 3 and, like Alex, had a speech delay. (At the request of his mother, Mary Walsh, these are not their real names, as John does not know he has autism.) Unlike Alex, John has no signs of intellectual disability. He attends a typical general education school and excels in reading and math. He can use public transport himself and can even explain to passers-by how to navigate the city's complex metro system. John easily carries on a conversation, although he tends to take everything literally, and some phrases, such as "hail a taxi", confuse him. nine0003

(At the request of his mother, Mary Walsh, these are not their real names, as John does not know he has autism.) Unlike Alex, John has no signs of intellectual disability. He attends a typical general education school and excels in reading and math. He can use public transport himself and can even explain to passers-by how to navigate the city's complex metro system. John easily carries on a conversation, although he tends to take everything literally, and some phrases, such as "hail a taxi", confuse him. nine0003

Alex's parents describe her as "low functioning" while John's parents describe him as "high functioning". However, such labels can be misleading.

“At the time of diagnosis, parents often ask if their child is high or low on the spectrum? says Tony Charman, professor of clinical child psychology at King's College London. “And you seem to understand what they are asking about, but you don't really know it. Are they asking about "severity of autism"? Or about daily functioning and adaptation?” nine0003

For example, despite his speech and cognitive difficulties, Alex copes well with many aspects of daily life. She spends most of her weekdays at a school for children with autism and other developmental disabilities. As soon as she gets home, she immediately runs to her room and quickly changes into home clothes without help. She keeps her room clean and tidy. Dozens of her original drawings hang on the walls of her bedroom. She likes to repeat the full names of her favorite composers: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven. If it seems to her that her younger brother is in pain, she immediately rushes to him with a first-aid kit to somehow help. nine0003

She spends most of her weekdays at a school for children with autism and other developmental disabilities. As soon as she gets home, she immediately runs to her room and quickly changes into home clothes without help. She keeps her room clean and tidy. Dozens of her original drawings hang on the walls of her bedroom. She likes to repeat the full names of her favorite composers: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven. If it seems to her that her younger brother is in pain, she immediately rushes to him with a first-aid kit to somehow help. nine0003

During dance lessons at her school, Alex often sets an example for other children, and her mother, Wendy Garish, boasts that her teacher calls her the best dancer in the class. She even has friends in her class, and every Wednesday she has lunch with a boy she particularly likes. “They love each other,” Wendy says. “When they walk side by side, she always takes his hand.”

On the other hand, although John is successful in school and in many aspects of his daily life, he has problems that are not always visible from the outside. He has no friends at all, and it is difficult for him to understand other people's emotions from facial expressions or tone of voice. During physical education, he walks around the gym instead of playing games with others. He can be very inflexible, which is a key sign of autism. For example, for each day of the week, he must wear a shirt of a certain color - blue on Mondays and orange on Fridays. However, the school requires students to wear only black and white, a rule that used to cause him great anxiety. Before he got used to this rule, John could only go to school if he wore the "correct" color shirt under a black and white uniform, which he pulled off as soon as he got home. nine0003

He has no friends at all, and it is difficult for him to understand other people's emotions from facial expressions or tone of voice. During physical education, he walks around the gym instead of playing games with others. He can be very inflexible, which is a key sign of autism. For example, for each day of the week, he must wear a shirt of a certain color - blue on Mondays and orange on Fridays. However, the school requires students to wear only black and white, a rule that used to cause him great anxiety. Before he got used to this rule, John could only go to school if he wore the "correct" color shirt under a black and white uniform, which he pulled off as soon as he got home. nine0003

It is clear that Alex and John are functioning well in certain aspects of life, but are having problems in others. Each has its own unique skills and difficulties. Their stories are a perfect illustration of the problem of autism research in general: what exactly do the terms "high functioning" and "low functioning" mean, and who can be called that?

Research currently underway in Canada may help answer this question. Since 2004, a team of researchers from five universities has been following more than 400 children since they were diagnosed with autism. Alex and John are one of those kids. The purpose of the study is to describe and classify the developmental trajectories of children, that is, how their symptoms and abilities change in different areas over the next years and even decades. This long-term study should help explain why the skills of these two children began to differ so much over time, even though they were virtually the same at the time of diagnosis. The study should also explain how to change traditional labels to more accurately describe children with autism. nine0003

Since 2004, a team of researchers from five universities has been following more than 400 children since they were diagnosed with autism. Alex and John are one of those kids. The purpose of the study is to describe and classify the developmental trajectories of children, that is, how their symptoms and abilities change in different areas over the next years and even decades. This long-term study should help explain why the skills of these two children began to differ so much over time, even though they were virtually the same at the time of diagnosis. The study should also explain how to change traditional labels to more accurately describe children with autism. nine0003

Other research teams are developing multi-component techniques to measure how well people with autism function in various areas of daily life, from interacting with other people to visiting public places. These new tools can form the basis of a common language so that scientists, practitioners and families understand what is being said. Also, new tools can help develop a personalized approach to treatment, depending on the lack of specific skills in a person. In addition to these purely practical tasks, such studies offer a more holistic view of the life of a person with autism in all its diversity. nine0003

Also, new tools can help develop a personalized approach to treatment, depending on the lack of specific skills in a person. In addition to these purely practical tasks, such studies offer a more holistic view of the life of a person with autism in all its diversity. nine0003

Beyond Labels

In autism research, the term "high functioning" usually refers to someone who scores above 70 or 80 on an intelligence quotient (IQ) test. Sometimes researchers exclude people who do not meet this criterion from studies because they may have difficulty understanding instructions and cooperating during the study.

Relying on IQ is too crude, however, says Peter Satmari, head of the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Alliance at the Center for Addiction and Mental Health at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, who is leading the long-term Canadian study. "This test doesn't measure functioning, it measures the presence or absence of an intellectual disability," he says. “It says nothing about how successful children with autism are in the real world. ” nine0003

” nine0003

Some researchers use symptom severity as a metric. For example, they consider a child to be low-functioning who often avoids contact with other people, shakes their hands a lot, or exhibits other repetitive behaviors and limited interests.

Meanwhile, parents of children with autism usually judge functioning by whether their child talks and how easy it is for him or her to participate in various activities. According to Katherine Lord, director of the Center for Autism and Brain Development at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, parents often use the word "low functioning" as a simple way to indicate that their child has some kind of disability, without going into details exactly what these are. violations consist. “Sometimes there is a lot of media coverage of people with autism who can talk about themselves or who have various amazing talents, so many families just want to emphasize that this does not apply to their children,” she explains. nine0003

However, such a label often forms a negative attitude towards such children in society and limits their future opportunities. “The term ‘low-functioning’ is just a nightmare,” says Lorde. “This does not mean that the child cannot do anything, it just means that he needs more support.” (In the US, the diagnostic manual provides for varying degrees of severity of autism based on the level of support a person needs, not on ability.)

“The term ‘low-functioning’ is just a nightmare,” says Lorde. “This does not mean that the child cannot do anything, it just means that he needs more support.” (In the US, the diagnostic manual provides for varying degrees of severity of autism based on the level of support a person needs, not on ability.)

But the label "highly functional" also comes with undesirable consequences. Anyone, even if they don't have autism, will function better in some areas of life and worse in others, whether it's the ability to make friends and maintain friendships, learn new things, remember information, solve math problems, or focus. The word "high-functioning" implies that a person will be equally competent in all areas, but that's just not true, says Charman: "A person can have a very high level of intelligence and still have severe social impairment and huge great difficulty in everyday situations due to sensory sensitivity or high levels of anxiety.” nine0003

In fact, both labels are very restrictive. As a result, one child may be deprived of opportunities for which he is really ready, and another child may be denied the help he needs.

As a result, one child may be deprived of opportunities for which he is really ready, and another child may be denied the help he needs.

However, a complete rejection of any labels also does not seem likely. Researchers need some language to describe the different manifestations of autism, says Lord. “The problem is that we, like all people, like to classify everything with words,” says Lord. "It's just desirable to come up with something better than 'high-functioning' and 'low-functioning'." nine0003

Various paths

Satmari's research suggests similar alternatives. The idea for the study dates back to the 1990s, before Alex and John were born. Satmari and his colleagues wanted to design and conduct a survey that would prioritize further research from the perspective of the autism community, which includes parents, professionals, and government officials. They conducted a survey to evaluate these priorities, and the most popular offer came as a complete surprise to them. nine0003

nine0003

“I thought most people would ask to investigate what form of early intervention is most effective, or what treatment is best,” Satmari says. Instead, the question that most often came up was: “What factors are associated with a favorable prognosis?” In other words, what determines how well a person with autism will function in everyday life?

To answer this question, Satmari and colleagues launched the Autism Spectrum Pathways research project to follow children diagnosed with autism between the ages of 2 and 4 over a long period of time. Because different researchers had different ideas about what a “good prognosis” is for people with autism, the research team decided not to focus on any particular area, but to evaluate children's functioning in a variety of areas. nine0003

"We found many different kinds of so-called 'good predictions'," says Mayada Elzabag, professor of psychiatry at McGill University in Montreal, who is working with Satmari on this study. “Our goal is to cover as many possible areas that we understand and consider meaningful. ”

”

The researchers measured cognition, language skills, and autism symptom severity using standardized tests four times during the first four years of the study and approximately every two years thereafter. Parents and other family members completed questionnaires about their own stress level, how they cope with difficult situations, as well as self-care skills, behaviors, symptoms and treatment of the child. nine0003

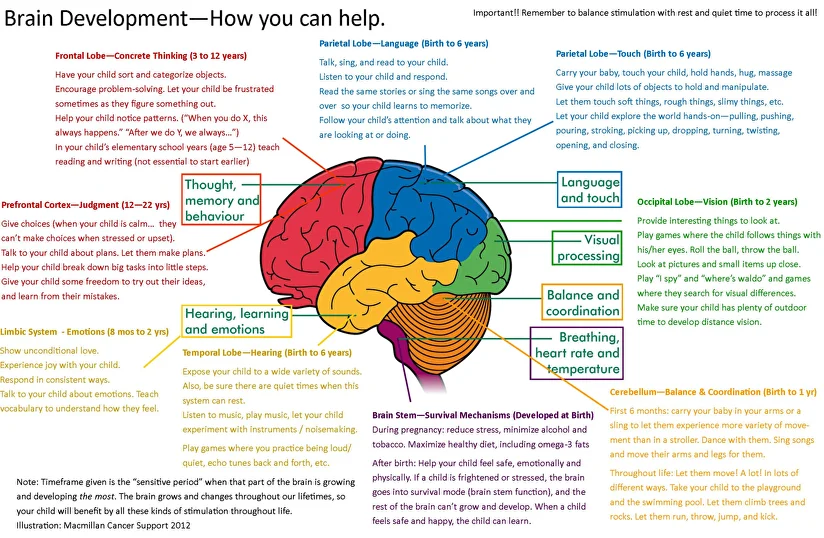

One of the aims of the study is simply to describe how a child's symptoms, skills, and abilities change as they grow up, and to determine whether there are distinct subgroups of children along developmental trajectories. Another goal is to understand how certain traits in early childhood—IQ, language ability, gender, or age at diagnosis—may predict later changes.

The initial phase of the study has already made discoveries about how symptom severity and daily living skills may change from diagnosis to 6 years of age. (The second phase, for which scientists collected data last year, answers the question about the functioning of children up to 11-12 years old, and the third phase observes children up to 18 years old). After analyzing four years of data, Satmari and colleagues reported last year that they were able to divide children into two groups based on the severity of symptoms, including social and communication impairments, repetitive behaviors and limited interests. Most of the children had severe symptoms at the time of diagnosis that had changed little over time up to 6 years. A small group, 11%, started out with relatively mild autism symptoms that improved significantly over time. nine0003

After analyzing four years of data, Satmari and colleagues reported last year that they were able to divide children into two groups based on the severity of symptoms, including social and communication impairments, repetitive behaviors and limited interests. Most of the children had severe symptoms at the time of diagnosis that had changed little over time up to 6 years. A small group, 11%, started out with relatively mild autism symptoms that improved significantly over time. nine0003

The team then analyzed skills for everyday life, so-called adaptive functioning - how children communicate and interact with others, whether they can make phone calls or use the Internet, whether they can eat, dress, bathe, brush their teeth on their own, do they understand the concepts time or money. One group of children, approximately 29%, had very poor day-to-day skills that deteriorated over time. The second group, about half of the children, had moderate functioning skills that remained stable. The third and smallest group of children had the most developed skills at the time of diagnosis, which improved with age. nine0003

The third and smallest group of children had the most developed skills at the time of diagnosis, which improved with age. nine0003

Surprisingly, the first and second types of measurements practically did not correspond to each other. Children with the most severe symptoms of autism did not necessarily have the lowest daily skills, and it appears that the severity of symptoms generally has little to do with daily tasks.

This data reflects what parents often report: There are children like Alex who may have limited interests and speech problems but can still manage day to day tasks. It also confirms that measurements in one area of functioning cannot predict how successful a child will be in other areas. nine0003

At the same time, some experts evaluate the severity of autism symptoms to determine which child needs treatment the most, or to understand how effective a particular type of therapy is. According to Satmari, their study casts doubt on this approach. “We should focus on how the child functions in everyday situations and what he does in the real world, and if his symptoms prevent him from doing this, then fine, but if something does not interfere in real situations, then this is not about it. gotta worry." nine0003

gotta worry." nine0003

However, not all experts agree that symptom severity and daily living skills are completely independent of each other. According to Lord, Satmari and colleagues controlled for differences in language ability and age when they measured symptom severity, but only controlled for age when they measured everyday skills. This means they can't really compare these numbers to each other. (The children's language skills were similar at the start of the study, Satmari said, but he did not comment on how differences in language skills in later years might have affected the results.) nine0003

In any case, by describing the dynamic nature of autism, Satmari's data indicate that the same label should not be used throughout a child's life. Most studies categorize children with autism as "high-functioning" and "low-functioning" based on one measure of IQ. However, "children can change, and the degree to which they differ from other children can also change," says Lonnie Zweigenbaum, director of the Center for Autism Research at the University of Alberta, who worked with Satmari on the study. That is why it is impossible to judge the level of functioning of a child with autism depending on one test in early childhood. nine0003

That is why it is impossible to judge the level of functioning of a child with autism depending on one test in early childhood. nine0003

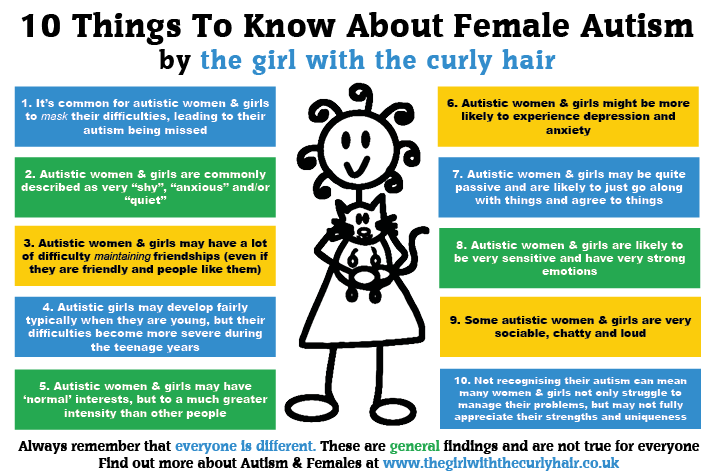

Since only data from the first phase of the study were analyzed, it is too early to talk about factors in early childhood that may indicate one or another prognosis. So far, researchers have been able to understand that in boys, autism symptoms are more stable during childhood, while girls are more likely to start out with milder symptoms that improve with age. What's more, children who were diagnosed earlier, as well as those with higher intelligence or earlier speech onset, had better day-to-day skills and developed more over time. nine0003

For example, Alex's social and language skills have improved tremendously over the past three years, says Wendy, her mother. Alex's parents are increasingly confident in her ability to handle household chores. Although Alex still needs help with washing or using the toilet, she has no problem choosing and dressing herself, brushing her teeth, making her bed, and setting her own meals.

One day in February, for example, Wendy placed a plate of chocolate chip cookies on the table, and Alex immediately looked into the matter. She brought the cookie to her nose and took a deep breath. Disgusted on her face, she tossed the cookies back onto her plate and ran out of the room. She fumbled in the fridge for a while, then returned to the ice cream parlor. It was clear that she understood when the family would have dessert and made the decision about what she would eat as she did not like what the others would eat. nine0003

At the same time, Alex's parents worry that the label "low-functioning" will hinder her development. For example, Alex enjoys swimming and her parents say they have seen ads for swimming lessons, but only for high-functioning children with autism.

“She can swim, she's a better swimmer than many high-functioning kids,” says her father, Peter Garish. “It's just that they're afraid that 'low-functioning' means they require a lot more attention. They default to thinking low-functioning people can't do the same." nine0003

They default to thinking low-functioning people can't do the same." nine0003

New measurements

Last year, the Satmari team received funding to continue monitoring children up to the age of 18. As scientists prepare to study the development of children during adolescence, they are pondering the influence of the environment on how successful a person with autism will be in life. They will examine the impact of factors such as high school education, family socioeconomic status, ethnicity, use of support services, and parental mental health. “A lot of autism research focuses only on the personality of a child with autism, their symptoms, IQ and speech, all variables in them are inside the child. Satmari says. “We offer a more holistic approach.” nine0003

So far, researchers have focused on quantifiable abilities: symptom severity, IQ, skills, and behaviors. Elzabag also plans to conduct qualitative research.

A side project within Pathways, Voices of the RAS, plans to collect the opinions of the children themselves, to record their hopes and dreams, interests, feelings and thoughts. So far, the details of such a study are only being worked out, but the team of scientists plans to conduct interviews with those children who can communicate using words, and for children who cannot, alternative methods of self-expression will be offered, for example, through drawings and photographs. The aim of the researchers is to determine what a "good prognosis" is from the child's own point of view and to compare the findings with traditional measures of prognosis in research. The people who can best describe the good prognosis for these children are the children themselves, Elzabag said. nine0003

So far, the details of such a study are only being worked out, but the team of scientists plans to conduct interviews with those children who can communicate using words, and for children who cannot, alternative methods of self-expression will be offered, for example, through drawings and photographs. The aim of the researchers is to determine what a "good prognosis" is from the child's own point of view and to compare the findings with traditional measures of prognosis in research. The people who can best describe the good prognosis for these children are the children themselves, Elzabag said. nine0003

Other teams of scientists are also developing methods that will go beyond the traditional high versus low functioning. For example, researchers at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden are developing a standardized test to compile a complex profile of functioning in children with autism.

The team's work is based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), a massive tool developed by the World Health Organization to measure how various diseases affect daily functioning. The ICF includes over 1,400 indicators to be assessed on a scale from 0 to 9from how the disease affects physical well-being and the ability to perform daily tasks to how environmental factors such as relationships or access to support services affect a person's daily life.

The ICF includes over 1,400 indicators to be assessed on a scale from 0 to 9from how the disease affects physical well-being and the ability to perform daily tasks to how environmental factors such as relationships or access to support services affect a person's daily life.

Because the ICF is so voluminous, it is impractical for frequent use in research. To make it more useful for autism research, Karolinska's team, led by neuropsychiatrist Sven Bolte, is developing the so-called ICF Core Lists for Autism Spectrum Disorder, which will address brain function, communication, social skills, and relationships. Everyone will be able to use these lists as a way to determine the strengths and limitations of a person with autism, Bolte said, instead of a vinaigrette of various types of tests. nine0003

Another team at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada, is developing a method to classify children with autism based on their communication in everyday life. This approach is based on a motor function classification tool for children with cerebral palsy developed 20 years ago.

This method focuses on social communication because interviews with a group of autism experts have shown that this area of functioning is the most important for the development of a classification system, but scientists can develop the same scheme for other areas of functioning, says Briano Di Rezze , professor of rehabilitation sciences at McMaster University, who is leading the project. This classification includes five short paragraphs to describe the level of ability. For example, at the lowest, fifth level, a child is described who rarely interacts with other people, and if he has speech, then it is addressed only to himself, and in general he does not understand the meaning of communication. At the same time, the first level describes a child who can participate in a dialogue with another person and maintain relationships. nine0003

Di Rezze says such a system should be easy for everyone and take little time so that scientists, educators and parents of children with autism can describe the child's functioning in the same language. If the teacher evaluates the child differently than his parents, then this is an opportunity to talk about the differences in the child's behavior at school and at home. “Perhaps there are some other conditions at the school, and they need to be paid attention to and help,” says Di Rezze.

If the teacher evaluates the child differently than his parents, then this is an opportunity to talk about the differences in the child's behavior at school and at home. “Perhaps there are some other conditions at the school, and they need to be paid attention to and help,” says Di Rezze.

Each of the new tools may allow physicians to indicate specific support needs. And everyone is paying more attention to what people with autism can do, what they can't, notes Zweigenbaum. “I think this is a huge breakthrough from how we have historically defined functioning in autism,” he says. nine0003

This shift in focus also reduces negative attitudes towards autism and helps clinicians better connect with families. “Medicine and the healthcare system is designed to deal with medical problems, and it's hard for parents to talk about what their children are doing well because the system itself is focused on deficits,” says Di Rezze. “When we introduce them to the idea of focusing on strengths, it’s like a breath of fresh air for them. ”

”

Indeed, parents say they like the emphasis on ability. nine0003

John's mother, Mary, is pleased with his progress since his diagnosis. Maybe one day he could go to college, even become a lawyer. However, first of all, she says, it is important for her that he be happy and feel that he has his own place in society.

For her, his limited interests are not so much a problem that needs to be corrected as an ambiguous dignity, and the absence of friends no longer bothers her as much as before. “If he doesn’t care about this, then why should I? she says. - If my son is passionate about watches, the subway, politics and different types of aircraft, then he does not need to be treated for this. Isn’t it wonderful that some people can be addicted to such unusual things?” nine0003

Alex's parents also say that the main thing for them is to develop her strengths, and her progress over the past few years helps them to remain optimistic, although they have no idea what the future holds for her.

They are afraid that someone will take advantage of Alex's naivety, or that she will never be able to live on her own. At the same time, she has made such progress over the past three years that Wendy hopes that Alex can get some simple work, maybe a computer job, that will help her feel successful. "I would be very happy to know that she has become part of society." nine0003

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

Diagnostics and tests, Scientific research

NEDUGAMNET.RU - all about medicine in Tyumen

Autism

Autism is a mental development disorder characterized by motor and speech disorders. Children with autism prefer loneliness, do not want to make friends, do not communicate with peers. They slowly develop speech, instead of words, autists often use gestures, do not respond to smiles. The disease is more common in boys. nine0003

The disease is more common in boys. nine0003

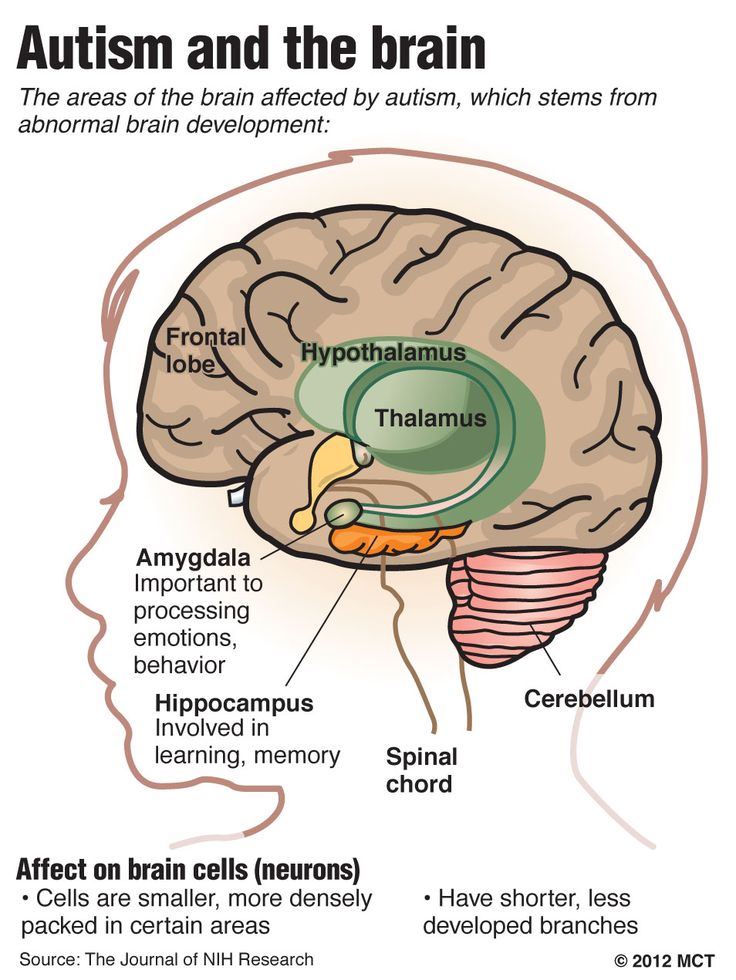

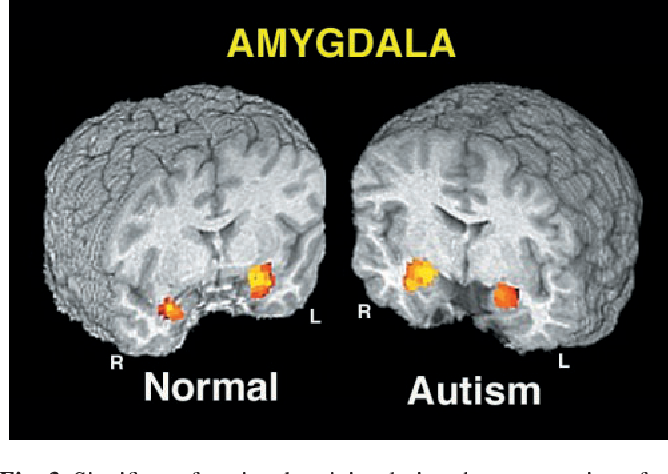

Causes

Causes unknown. Scientists suggest the possible impact of traumatism in childbirth, infection, traumatic brain injury, the introduction of a vaccine on the development of the disease. Some scientists refer autism to childhood schizophrenia. There is also an assumption about congenital dysfunction of the brain.

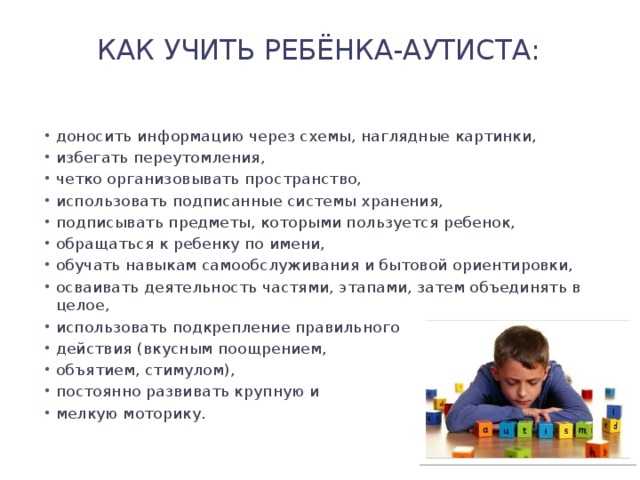

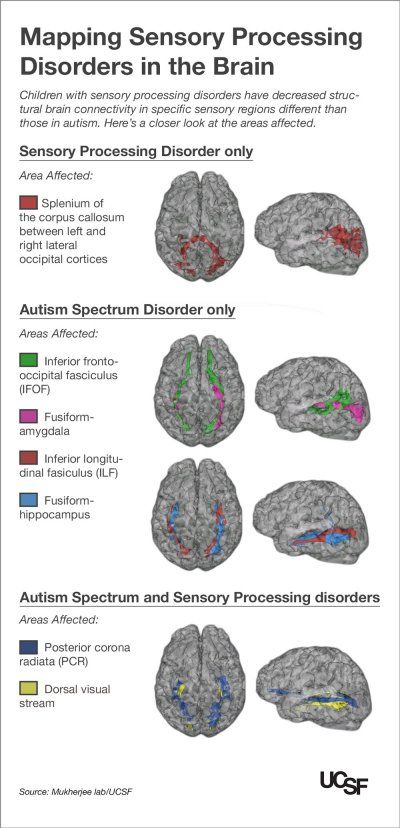

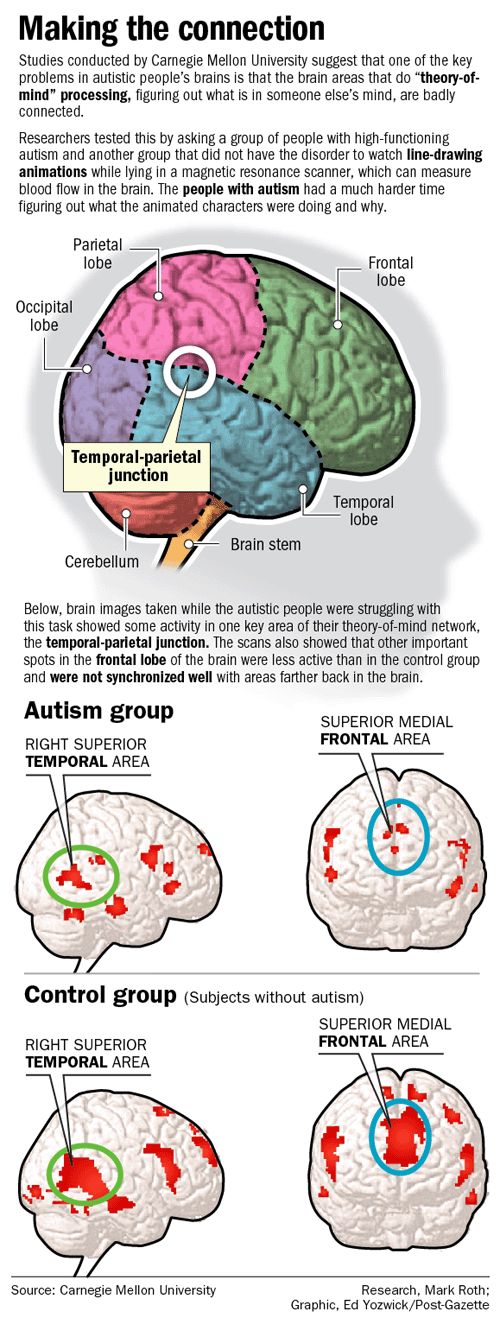

Changes in many parts of the brain are found in autism, but how they develop remains unclear. Parents notice signs of the disease during the first two years of a child's life. With early cognitive and behavioral interventions, the child can be helped to learn social interaction, self-help, and communication skills, but there are currently no methods developed that can completely cure autism. In some cases, children, upon reaching adulthood, manage to move on to an independent life. nine0003

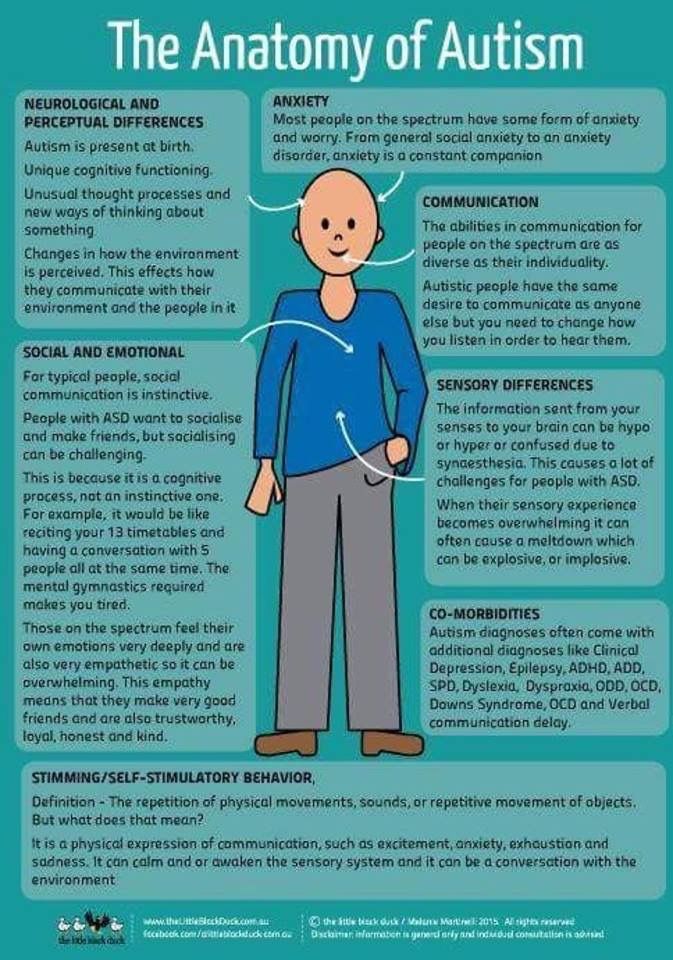

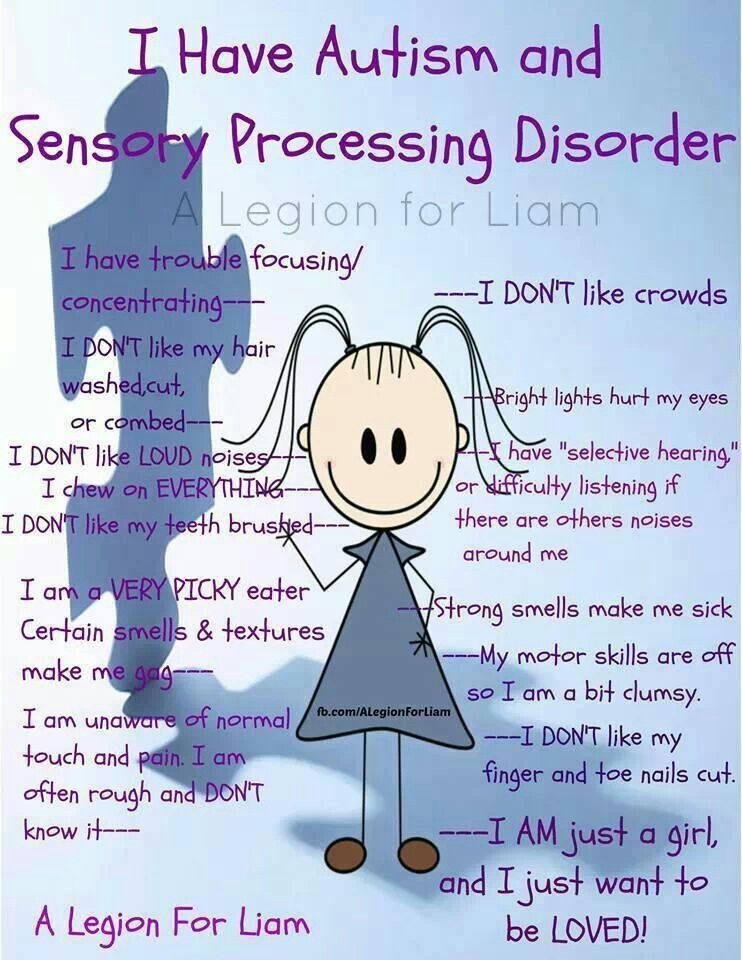

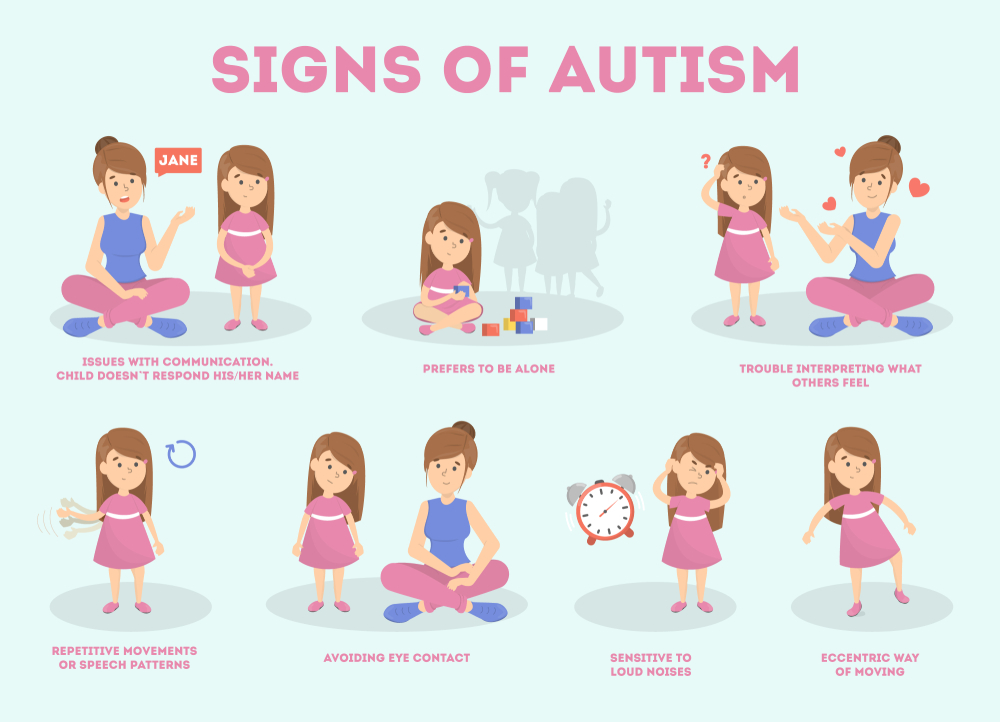

Symptoms of autism

Sometimes autism is diagnosed as early as infancy, but more often the symptoms of the disease appear by the age of 3 years. A characteristic manifestation of autism is an inadequate response to stimuli. Children get frightened and start crying at the slightest discomfort. Another sign of autism is a weak reaction of pleasure to communication with adults or to feeding, the revival of the child when interacting with inanimate objects, the manifestation of hysteria when the environment changes. Such children practically do not speak, do not show interest in events, are reluctant to play with peers, and at the same time do not suffer from loneliness at all. The child feels the need to accurately repeat the same actions, focuses on one thing. Adult autistic people are not capable of emotions of pity, sympathy and mutual understanding. nine0003

A characteristic manifestation of autism is an inadequate response to stimuli. Children get frightened and start crying at the slightest discomfort. Another sign of autism is a weak reaction of pleasure to communication with adults or to feeding, the revival of the child when interacting with inanimate objects, the manifestation of hysteria when the environment changes. Such children practically do not speak, do not show interest in events, are reluctant to play with peers, and at the same time do not suffer from loneliness at all. The child feels the need to accurately repeat the same actions, focuses on one thing. Adult autistic people are not capable of emotions of pity, sympathy and mutual understanding. nine0003

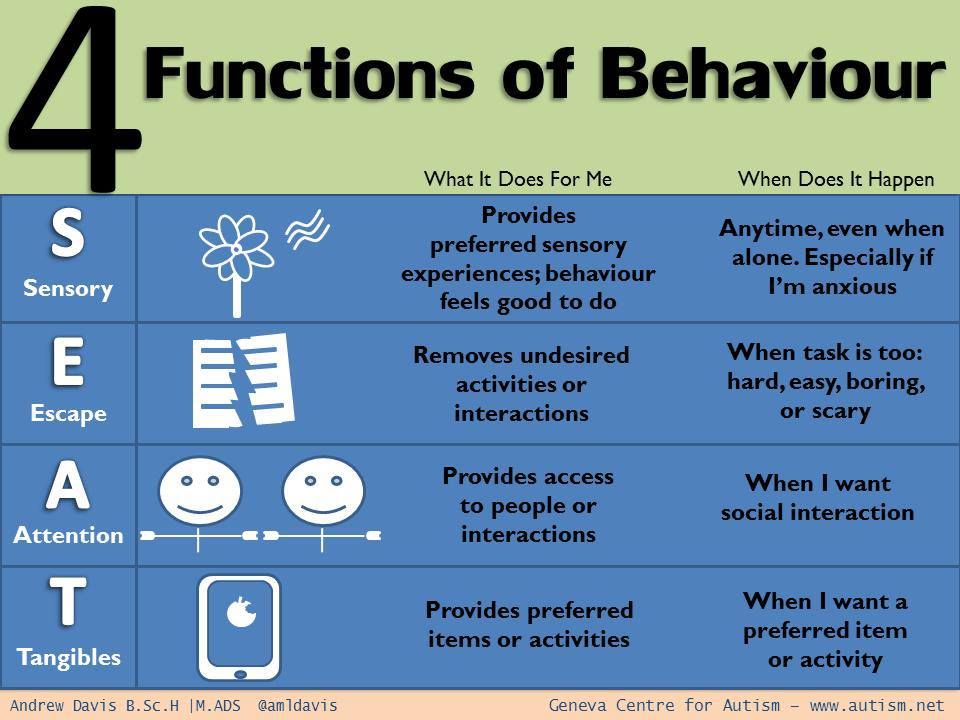

There are many forms of limited or repetitive behavior in autistic people, which are divided into the following categories according to the RBS-R (Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised) scale:

Between 0.5% and 10% of people with autism spectrum disorder have special skills or unusual abilities in one or more areas of knowledge (“island of genius”) - remembering facts, dates, arithmetic calculations, musical or artistic talents. nine0003

Diagnosis of autism

It is difficult to detect autism in infancy. The diagnosis of autism is made by a psychiatrist during the examination. Usually they use a questionnaire for diagnosing autism, an evaluation scale for childhood autism.

Types of disease

Distinguish between low-functioning, medium-functioning and high-functioning autism, using an IQ scale for this and assessing the level of care a person needs in everyday life. Autism is also divided into syndromic and non-syndromic. nine0003

Autism is also divided into syndromic and non-syndromic. nine0003

Patient response

If parents find their child has signs of autism, they should contact a child psychiatrist.

Treatment for autism

Treatment is individualized. Programs of special education, behavioral therapy help the child to acquire communication skills, contribute to the acquisition of work skills, increase the level of functioning, reduce the severity of symptoms. They use applied behavior analysis, “developmental models”, structured learning (TEACCH), social skills training, speech therapy, occupational therapy. In some cases, psychotropic and anticonvulsant drugs are prescribed. Antidepressants, stimulants, and antipsychotics are commonly used. nine0003

Complications of autism

Illness leads to impaired social interaction. In children, autism is manifested by reduced attachment to loved ones. Adults with autism have problems finding a profession, sexual relations, finding a job, using social skills, and estate planning.