Rudolf steiner personality types

The Four Temperaments: Understanding the Waldorf Early Childhood Approach

As a parent of a young child, I recently returned to the four temperaments and found the numerous articles and blog posts on them confusing, if not misleading. I am writing this to share with you some of my observations based on my perceptions and understanding.

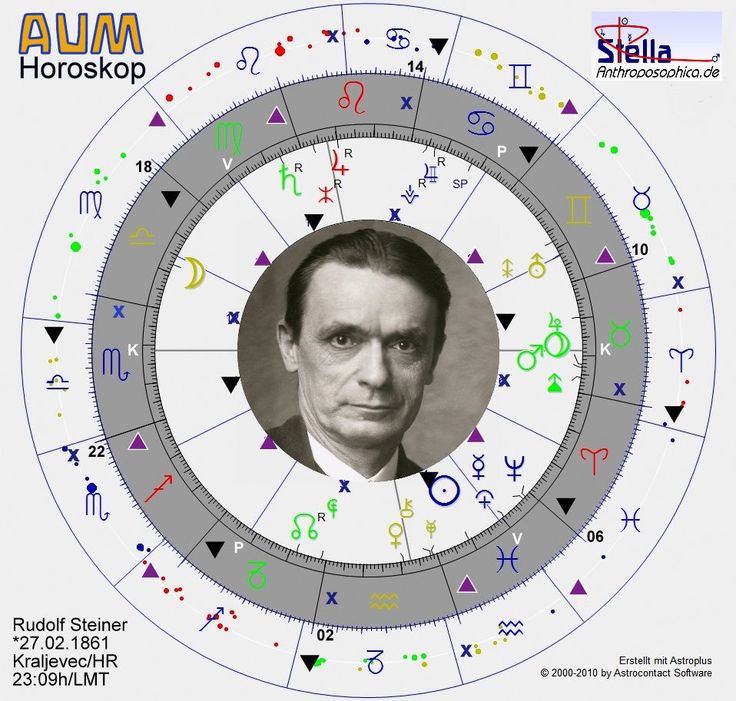

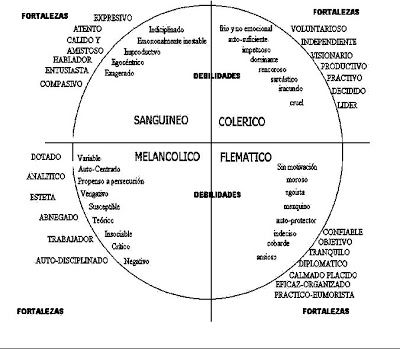

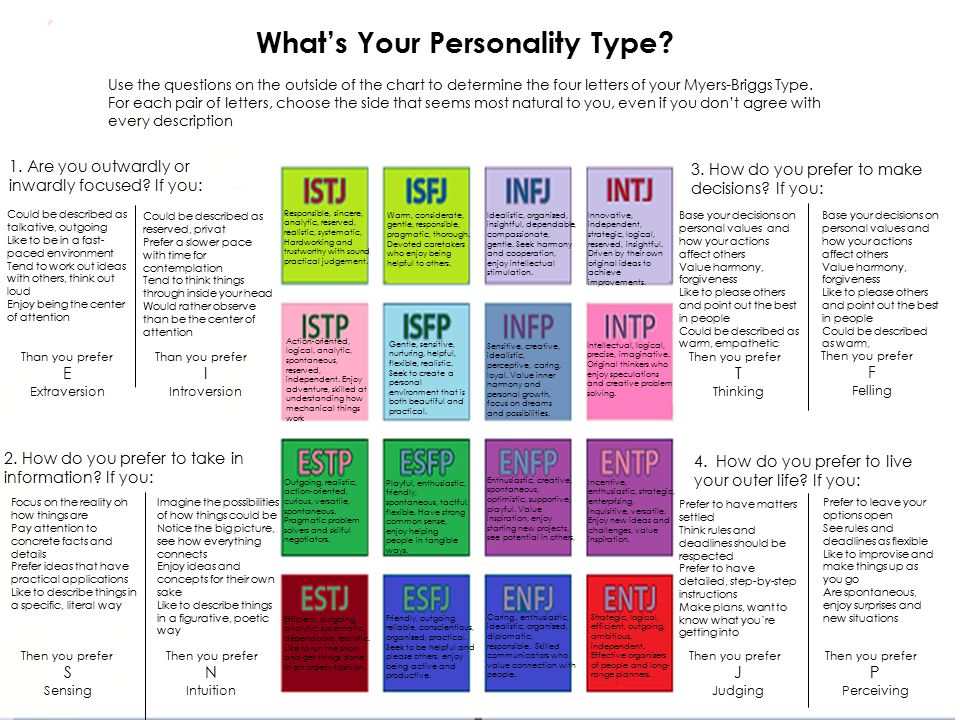

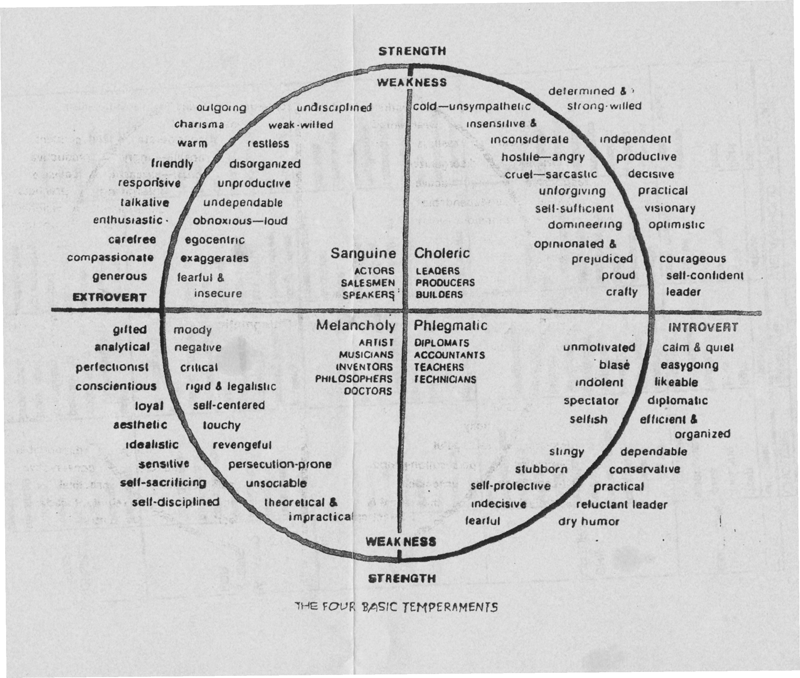

Rudolf Steiner developed an approach to education that was based upon the unique blossoming of the inner and outer life of the individual in seven-year cycles. For early childhood, he placed importance on the awareness of temperaments (choleric, sanguine, phlegmatic and melancholic) in the context of his larger world view.

To clarify, there are not four types of children within the temperaments, but in truth a unique temperament for every individual. Hence, when one contemplates temperaments in a child, one must appreciate that the four temperaments are actually ‘forces’ that interact with other personality attributes and social influences in a singular fashion as well as the forces within the various temperaments.

(Nevertheless, I sometimes refer here to a temperament as a type for facility of writing, e.g. I write, ‘phlegmatic’ instead of the more cumbersome, ‘a child with dominant phlegmatic tendencies overriding and interacting with the other three.’) Within each temperament there is, in turn, much variation, further complicating one’s perceptions. One temperament always dominates, however ‘informed’ and influenced it is by the presence of the other three.

To begin, it might help to feel or imagine one’s way into the temperaments by how they reflect the larger stages of life’s journey. The sanguine is the temperament of youth; the choleric, of the second quarter; the melancholic, the third quarter; and phlegmatic, the fourth and final phase. Youth, the sanguine period, might be characterized by strong emotions, openness to experiences and strong likes and dislikes; the second stage of life (choleric) might be felt as period in which one’s ego turns to how it will transform the world; the third quarter (melancholic) is often one of shifting reflections over life and a deeper awareness of its transiency; and finally, the last quarter of life (phlegmatic) might be felt as one in which feelings ‘separate’ from oneself and appear almost as to arise before one’s being for contemplation and immersion, as does memory in its nearness and farness. If we feel these stages of life deeply, we can imagine better how our child’s temperament might shape their early personality.

If we feel these stages of life deeply, we can imagine better how our child’s temperament might shape their early personality.

The choleric child has a strong presence of ‘me-ness,’ of being an energy-centered ego or body that draws others to it. The sanguine, on the other hand, reacts emotionally to experiences of the world. Since the period of childhood is most similar to sanguinity, often the sanguine child is exuberant and content. The melancholic child seems burdened by experience and the passage of things without a mature awareness as to what this actually constitutes; it may translate to aggression or even dissatisfaction. Finally, the phlegmatic force in a child is one that draws them into deep immersion in activities and other children’s doings.

As another imaginative exercise, sometimes these four temperaments are characterized by elements: fire (choleric), air (sanguine), water (phlegmatic) and earth (melancholic). Hence one might feel an ‘earthy’ element to their child and identify melancholic tendencies. However, I suspect that many parents will find that their child is ‘fiery’ despite what their temperament might actually be.

However, I suspect that many parents will find that their child is ‘fiery’ despite what their temperament might actually be.

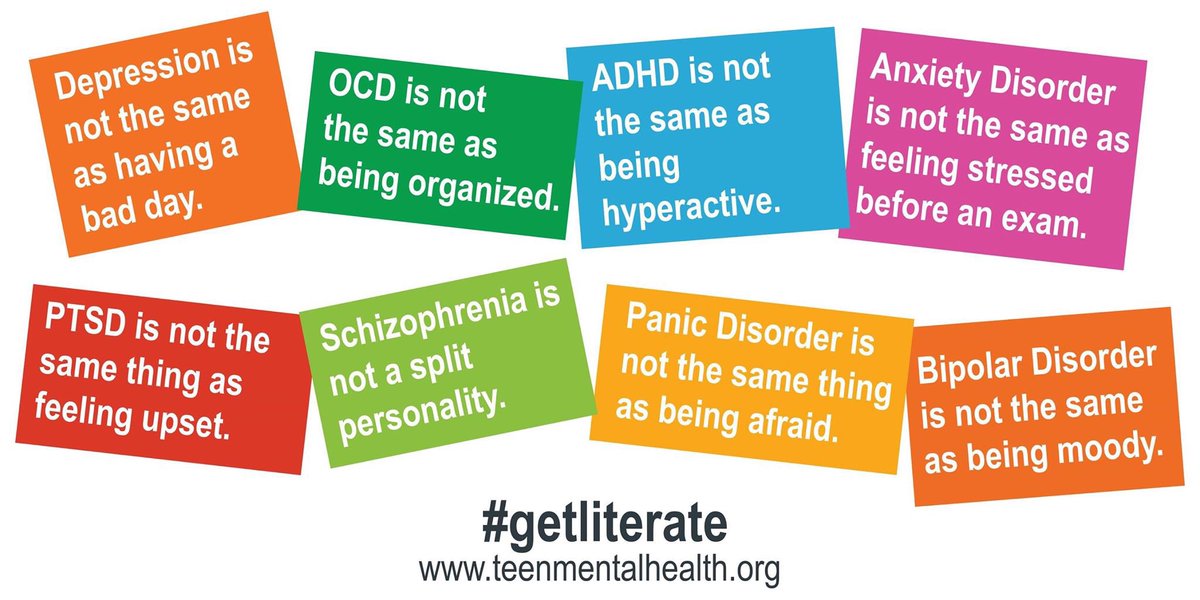

Waldorf teachers are trained to feel their way into the inner tendencies of a child so as to be able to nurture the child’s growth in a positive fashion. If not, the unique temperamental tendencies of a child may be misunderstood, combatted and judged from some projected cultural behavioral expectation. For example, a choleric child in mainstream culture may appear as having Attention Deficit Disorder. (This does not mean that every child with ADD has a choleric temperament.) In the Waldorf approach, the choleric child learns to respect the consistent rhythmic authority of the teacher. The child might be paired with another strongly choleric child so that the two learn from each other by a form of ‘resistance awareness.’ The phlegmatic child may appear to be listless and detached, and perhaps lack the ability to engage in ‘normal’ transitions due to their tendency to immerse themselves in their given activity. A child with phlegmatic tendencies will sometimes exhibit explosive anger when this is disrupted, like a little sloth lashing out with unexpected hooked claws. In the Waldorf approach, phlegmatics are sometimes paired with each other so that their mirroring tendencies awaken the energies to engage beyond them. Teachers share their sense of having endured trials with melancholics, winning the child’s mutual identification and admiration. (I note here that a melancholic might be misdiagnosed as being depressed, although, again, a depressed child is not necessarily melancholic in temperament.) Sanguines, in general, require the calm, steady interiority from their teacher’s meditative presence.

A child with phlegmatic tendencies will sometimes exhibit explosive anger when this is disrupted, like a little sloth lashing out with unexpected hooked claws. In the Waldorf approach, phlegmatics are sometimes paired with each other so that their mirroring tendencies awaken the energies to engage beyond them. Teachers share their sense of having endured trials with melancholics, winning the child’s mutual identification and admiration. (I note here that a melancholic might be misdiagnosed as being depressed, although, again, a depressed child is not necessarily melancholic in temperament.) Sanguines, in general, require the calm, steady interiority from their teacher’s meditative presence.

From ages seven to fourteen, the presence and power of the four temperaments recede to other shaping forces that shift into the foreground. Even though their early dominant influence retracts, they may be sensed in us adults as a residual presence.

For example:

1) choleric: Oprah Winfrey, Jason Statham, Hillary Clinton, Shakira

2) sanguine: Ursula K. LeGuin, Pope Francis, Yo-Yo Ma, Tom Cruise

LeGuin, Pope Francis, Yo-Yo Ma, Tom Cruise

3) phlegmatic: Emma Thompson, Owen Wilson, David Letterman, Dalai Lama

4) melancholic: Ang Lee, Dolores O’Riordan, Brad Pitt, James Dean, Tina Fey

If you are curious what your child’s temperament might be and how it may help you in understanding your child, email me.

— Alton C. Frabetti, Ph.D.

Alton C. Frabetti, Ph.D. is a Waldorf School at Moraine Farm parent. He lived in Italy for ten years studying Rudolph Steiner and Massimo Scaligero and founded an art gallery. Upon his return to the United States he completed an MA in philosophy and an MFA in sculpture at Stony Brook University and recently completed a Ph.D. in the Humanities from the University of Louisville in Aesthetics and Creativity.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Temperaments in a Waldorf School August 18 2015

The four temperaments are used in Waldorf schools for evaluating the character of each child one is teaching. These temperaments provide the teacher with tools for forging an inner connection, making the child feel that his or her teacher knows with wisdom what is behind each decision made in the classroom. Diagnosing temperaments correctly helps to build trust between teacher and student, teacher and class. Teachers often arrange seating of children so that students with similar temperaments are seated together or near each other. This provides a kind of gentle “homeopathic” experience or mirror to the child that helps the child build balance within his or her character without being heavy-handed, or too didactic.

These temperaments provide the teacher with tools for forging an inner connection, making the child feel that his or her teacher knows with wisdom what is behind each decision made in the classroom. Diagnosing temperaments correctly helps to build trust between teacher and student, teacher and class. Teachers often arrange seating of children so that students with similar temperaments are seated together or near each other. This provides a kind of gentle “homeopathic” experience or mirror to the child that helps the child build balance within his or her character without being heavy-handed, or too didactic.

Teachers in Waldorf schools are careful to avoid using the temperaments too much or too strongly. The danger of labeling a child is risky if the evaluative tool of determining a temperament is overused. Also, temperaments can transform as a young person grows and so attentiveness around temperaments is called for, instead of “final decisions” about them. The awareness of temperaments offers a teacher gossamer path into a student’s disposition for compassionate connection.

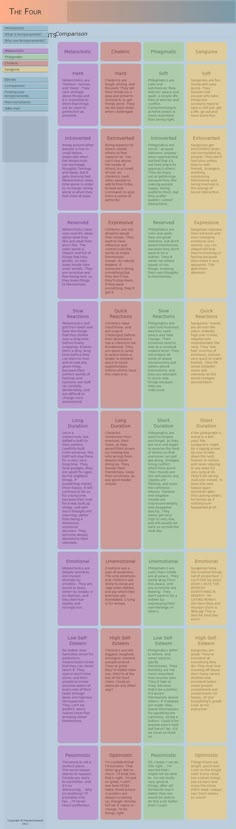

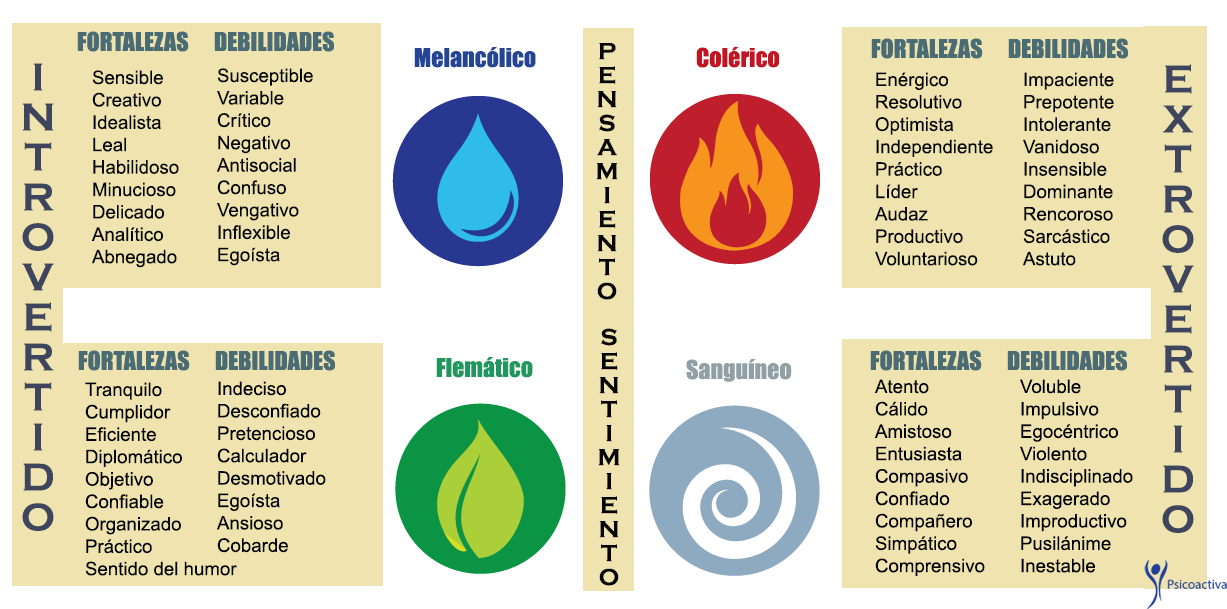

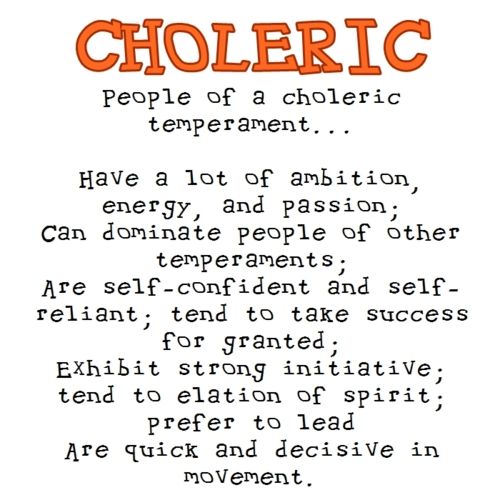

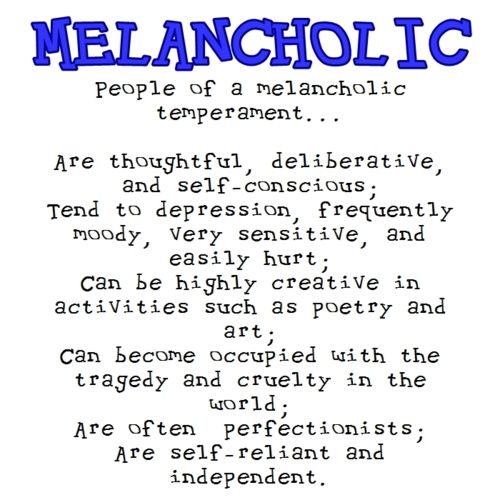

The four temperaments are: choleric, sanguine, phlegmatic, and melancholic.

The choleric is a person who is fulfilled by deeds. This temperament tends to be fiery with a keen interest in all things, a high level of engagement in all they do, and quickness to action. They are natural leaders and get a lot done in group work. Teachers do well to give them many difficult tasks, make clear rules, and stick to them with the fulfillment of any promised consequences. If the teacher fails to gain a choleric’s respect, trouble will ensue! Cholerics have a good sense of judgment and can usually be trusted to divide things evenly from a firm sense of fairness and equity. They are first to want to go out for recess, and they are impatient with those who are slow or weak. Red is the favorite color most often, and division is the favorite arithmetic function. Cholerics are difficult to live with because of their intensity and quick judgments; however, without cholerics, little gets done in a crowd. They tend to be heroic and commanding in a natural way and are loyal defenders of friends, family, and community when necessary. They tend to be heroic and commanding in a natural way and are loyal defenders of friends, family, and community when necessary. | | |

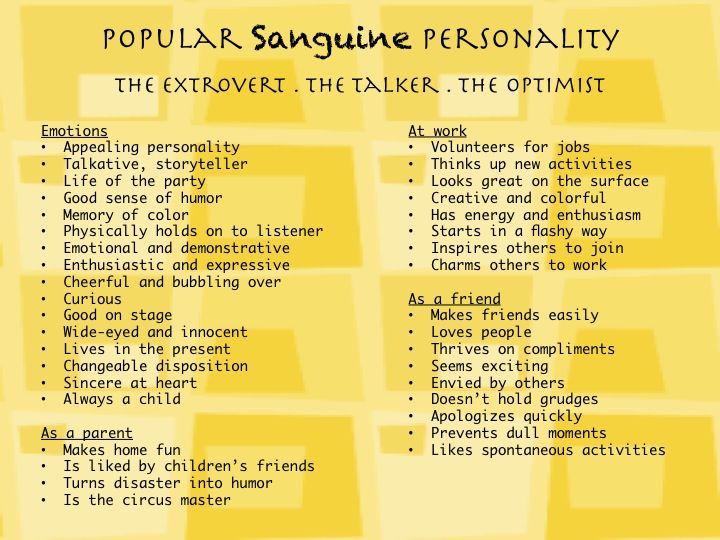

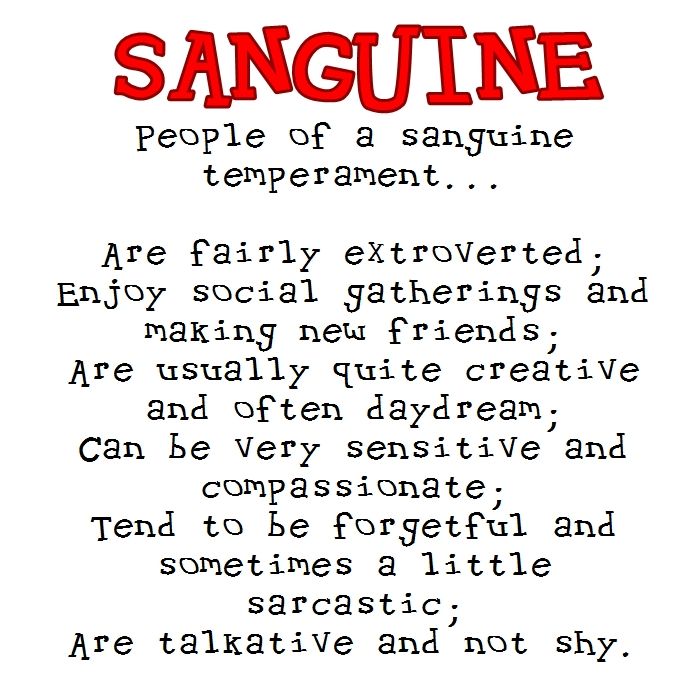

| The sanguine is the most social of the temperaments. A party with no sanguines will tend to be fairly dull. Sanguine children have trouble concentrating because their attention flits a bit. Their color is yellow, and they delight in quick changes and varied ideas. They love people and discussions. The favorite in arithmetic is multiplication. These children know all the news in any classroom and can trace activities from the beginning to the end. If a teacher wants to know what happened, s/he need only ask a sanguine. Seating sanguines together holds the promise that they all might get weary of how much talking is going on and talk a little less themselves. Jumping rope, skipping, and running are all favorites of the sanguine elementary school student. | ||

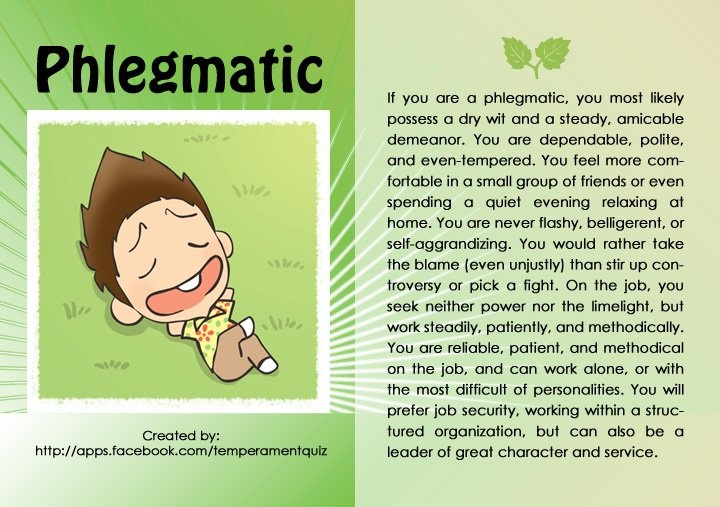

The phlegmatic is a complacent soul who would rather be left to his or her own devices than to be stirred to great action. Phlegmatics love food and mealtimes and look forward to these with a particular interest. They tend to like water and swimming (or, better yet, floating) and they are particularly unflappable. They have a knack at being cheerful and they tend to avoid describing any situation in terms of being a crisis. Finding the things that genuinely motivate these students is the task of the teacher because; left to their own devices they might do very little on their own, assuming that activities have little to do with them without the right kind of encouragement. Upsetting a phlegmatic, or making him or her move too frequently can cause the phlegmatic to behave like a choleric. The anger of a phlegmatic is infrequent but intense. Addition is a favorite of the phelgmatic. Green is often their favorite color. When phelgmatics are seated together they help each other to realize that very little happens in their group and they are stirred to break the inactivity and take the initiative of their own. Phlegmatics love food and mealtimes and look forward to these with a particular interest. They tend to like water and swimming (or, better yet, floating) and they are particularly unflappable. They have a knack at being cheerful and they tend to avoid describing any situation in terms of being a crisis. Finding the things that genuinely motivate these students is the task of the teacher because; left to their own devices they might do very little on their own, assuming that activities have little to do with them without the right kind of encouragement. Upsetting a phlegmatic, or making him or her move too frequently can cause the phlegmatic to behave like a choleric. The anger of a phlegmatic is infrequent but intense. Addition is a favorite of the phelgmatic. Green is often their favorite color. When phelgmatics are seated together they help each other to realize that very little happens in their group and they are stirred to break the inactivity and take the initiative of their own. | ||

The melancholic is a deep thinker, poetic in tendency. Melancholics tend to feel many things personally. Tasks can feel insurmountable to them easily and they tend to consider many situations in the most difficult light. They would, for example, most often consider the glass, “half empty.” In history lessons, these students view the misfortunes of mankind most compassionately. They often offer insights into people’s motivation from an understanding of the deep feeling life possible in human beings. Of the four arithmetic processes, subtraction tends to be their favorite. Teachers must sympathize deeply with melancholics in order to ensure that they feel understood. Blue is often a favorite color of melancholic children. The advantage to seating melancholics together is that they realize, in watching others like them closely, that it is a wise practice to “get over yourself,” and get on with productivity! Melancholics tend to feel many things personally. Tasks can feel insurmountable to them easily and they tend to consider many situations in the most difficult light. They would, for example, most often consider the glass, “half empty.” In history lessons, these students view the misfortunes of mankind most compassionately. They often offer insights into people’s motivation from an understanding of the deep feeling life possible in human beings. Of the four arithmetic processes, subtraction tends to be their favorite. Teachers must sympathize deeply with melancholics in order to ensure that they feel understood. Blue is often a favorite color of melancholic children. The advantage to seating melancholics together is that they realize, in watching others like them closely, that it is a wise practice to “get over yourself,” and get on with productivity! |

So, these are the four temperaments in a brief sketch from an elementary school teacher’s perspective. They are difficult to analyze in actual children and can take a lifetime of study and consideration with others who teach children. In different subjects, a child might manifest different temperamental characteristics and this becomes helpful information to consider in settling in one’s mind and heart what motivates a child or not. By adulthood, most people have two or three temperaments in balance working at the same time, with one slightly in the lead.

They are difficult to analyze in actual children and can take a lifetime of study and consideration with others who teach children. In different subjects, a child might manifest different temperamental characteristics and this becomes helpful information to consider in settling in one’s mind and heart what motivates a child or not. By adulthood, most people have two or three temperaments in balance working at the same time, with one slightly in the lead.

My favorite temperament story was one of a giant spill during a watercolor class. A large jar of water fell from a student’s desk. The cholerics in the class dashed to the closet to grab the sponge mop there. One choleric child ran down the hall to grab the spaghetti mop from the maintenance closet. The sanguine children jumped up on their chairs and screamed and chattered. The phlegmatic students moved their chairs to the deepest part of the water spill and sat down and the melancholic students shook their heads in dismay, predicted that no one would ever be able to clean up such a large spill and that the paintings would all be ruined. One melancholic whose water jar it was started to cry. The teacher watching all this had a perfectly delightful time watching it unfold, and was saved from overreacting to a difficult turn in his lesson. So, temperaments are useful in a number of ways! The Waldorf approach works creatively in this way with children/students of all temperaments.

One melancholic whose water jar it was started to cry. The teacher watching all this had a perfectly delightful time watching it unfold, and was saved from overreacting to a difficult turn in his lesson. So, temperaments are useful in a number of ways! The Waldorf approach works creatively in this way with children/students of all temperaments.

Rudolf Steiner. Essence of Thomism: philologist - LiveJournal

Lecture at Dornach May 23, 1920 Tracing the spiritual development of Europe, one can show how those ideas that we find in any person of the 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th centuries then pass into the ideas of thinkers of subsequent centuries, up to the 13th century. Thus, one can trace a certain evolution of ideas, abstract concepts. But all these are actually only symptoms of a deeper process of development, proceeding, so to speak, behind the scene of external phenomena. In the depths of human souls, a real development of impulses takes place, the bearer of which is the man of Europe. This is an organic process of the formation of European humanity. Let us recall how Homer began his epic songs: “Anger, O goddess, sing Achilles, the son of Peleus,” or “Sing, O muse, the deeds of a wandering husband, Odysseus.” People of that era really felt that if they wanted to express something significant, sublime, then some higher spiritual and spiritual field of ordinary human consciousness spoke through them. In the people of that era, it was not the individual “I” of a person that expressed itself, but the group Soul of the whole human race. nine0005

This is an organic process of the formation of European humanity. Let us recall how Homer began his epic songs: “Anger, O goddess, sing Achilles, the son of Peleus,” or “Sing, O muse, the deeds of a wandering husband, Odysseus.” People of that era really felt that if they wanted to express something significant, sublime, then some higher spiritual and spiritual field of ordinary human consciousness spoke through them. In the people of that era, it was not the individual “I” of a person that expressed itself, but the group Soul of the whole human race. nine0005

When Klopstock began his "Messiad", he already wrote: "Sing, immortal soul", that is, he addressed that individual being that lives in an individual person. At the time when Klopstock wrote, this feeling of his individual soul had already strongly developed in man. But this same inner impulse - to release, to form human individuality - awakens and unfolds throughout the entire era, from the time of the beginning of the spread of Christianity and up to the flowering of scholasticism. nine0009 This process of the formation of individual consciousness in a European person was accompanied by spiritual battles that found their culmination with Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. Outwardly, it looks as if Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas were trying to dialectically combine the teachings of Augustine with the teachings of Aristotle. At the same time, Albert was the bearer of predominantly church ideas, and Thomas was the bearer of finely developed philosophical ideas. The desire to find agreement between those and other ideas runs, like the main thread, through all the works of both thinkers. nine0005

nine0009 This process of the formation of individual consciousness in a European person was accompanied by spiritual battles that found their culmination with Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. Outwardly, it looks as if Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas were trying to dialectically combine the teachings of Augustine with the teachings of Aristotle. At the same time, Albert was the bearer of predominantly church ideas, and Thomas was the bearer of finely developed philosophical ideas. The desire to find agreement between those and other ideas runs, like the main thread, through all the works of both thinkers. nine0005

And now, much of what they imprinted in their thoughts and which is a kind of flourishing of the feelings and will of a European person - this continues to live on, right up to our days; from here we have drawn, however latently, all sorts of ideas for all our scientific disciplines, as well as for social life. To modern man, Augustine's doctrine of predestination seems paradoxical and even meaningless. But it crystallized in him as a result of a difficult internal struggle between, on the one hand, adherence to the teachings of Plotinus, who spoke only about the universal human, that is, about the inherent in humanity as a whole, and on the other hand, the feeling of human individuality awakened in Augustine's soul, the desire for individuality. That is why in Augustine his own teaching received such a chased and at the same time soulfully colored, heartfelt interpretation. That is why his personality makes such a strong impression on us and seems to us infinitely endearing. nine0005

But it crystallized in him as a result of a difficult internal struggle between, on the one hand, adherence to the teachings of Plotinus, who spoke only about the universal human, that is, about the inherent in humanity as a whole, and on the other hand, the feeling of human individuality awakened in Augustine's soul, the desire for individuality. That is why in Augustine his own teaching received such a chased and at the same time soulfully colored, heartfelt interpretation. That is why his personality makes such a strong impression on us and seems to us infinitely endearing. nine0005

However, already during the life of Augustine, some of his contemporaries could not come to terms with his teaching that a person is just a member deprived of independence of one of the two parts of humanity - either people chosen, redeemed by God, or, on the contrary, forever condemned Them. Especially unbearable was the thought of people eternally condemned by God to eternal perdition. Augustine himself had already had a bitter fight with Pelagius, who was already fully imbued with the individualizing European impulse, anticipating in this respect the people of later centuries. Therefore, Pelagius could only reason in the following way. There can be no question that a person is not able to influence his own destiny; he can and must engender from his individuality a certain force, thanks to which his soul will be able to join that which will be able to free it from the captivity of the externally sensible, to raise it into purely spiritual regions, where it can then find its redemption and return to freedom and immortality. In other words, an individual person can find in himself the strength to overcome original sin. The Church occupied a middle position between these two opponents - Augustine and Pelagius - and was looking for some way out, some intermediate formulation that would be, so to speak, not too white and not too black. nine0005

Therefore, Pelagius could only reason in the following way. There can be no question that a person is not able to influence his own destiny; he can and must engender from his individuality a certain force, thanks to which his soul will be able to join that which will be able to free it from the captivity of the externally sensible, to raise it into purely spiritual regions, where it can then find its redemption and return to freedom and immortality. In other words, an individual person can find in himself the strength to overcome original sin. The Church occupied a middle position between these two opponents - Augustine and Pelagius - and was looking for some way out, some intermediate formulation that would be, so to speak, not too white and not too black. nine0005

And the accepted wording read: things are as Augustine said, but at the same time not exactly as he said; it is not exactly as Pelagius said, but at the same time, in a certain way, it is so. According to the accepted ecclesiastical formulation, people do not divide God's eternal wise decision into sinners predestined for perdition and those chosen for grace; they themselves participate in their falling into sinfulness or in their attainment of fullness of grace. But at the same time, if there is no divine predestination, there is divine providence. God foresees in advance which person will remain in mortal sin, and which one will be filled with grace. This church dogma has spread. The crux of the matter, however, did not lie at all in some kind of divine providence, but in the distinct formulation of the following question and in a justified answer to it: can an individual individual man find such forces in his individual mental life and bind himself to them in such a way that they can lead him out of the accomplished separation of it from the divine-spiritual essence of the world and return it to it again? nine0005

But at the same time, if there is no divine predestination, there is divine providence. God foresees in advance which person will remain in mortal sin, and which one will be filled with grace. This church dogma has spread. The crux of the matter, however, did not lie at all in some kind of divine providence, but in the distinct formulation of the following question and in a justified answer to it: can an individual individual man find such forces in his individual mental life and bind himself to them in such a way that they can lead him out of the accomplished separation of it from the divine-spiritual essence of the world and return it to it again? nine0005

This was one of the cardinal problems that the thinkers of high scholasticism approached fully armed with the logical power of judgment, a logical technique that reached, one might say, the highest flowering among them. Abstracting now from the very content of the teachings of these thinkers, we can rightfully say that never before or since have people thought so precisely, so internally logical, as during the heyday of high scholasticism. It was at that time that pure thinking emerged, passing with mathematical precision from one idea to another, from one judgment to another, from one conclusion to the next, while being fully aware of its every step, its every smallest movement. It is necessary to imagine in what environment, in what conditions this thinking proceeded at that time. In reality, it was actually always a quiet monastery cell, far from the noise of worldly events. And this was one of those circumstances that allowed in the XII-XIII centuries. to develop mental activity, on the one hand, amazingly plastic, and on the other, possessing the finest and most precise contours. And such activities were consciously sought to be carried out by such people as Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. However, it is also necessary to remember the following. nine0005

It was at that time that pure thinking emerged, passing with mathematical precision from one idea to another, from one judgment to another, from one conclusion to the next, while being fully aware of its every step, its every smallest movement. It is necessary to imagine in what environment, in what conditions this thinking proceeded at that time. In reality, it was actually always a quiet monastery cell, far from the noise of worldly events. And this was one of those circumstances that allowed in the XII-XIII centuries. to develop mental activity, on the one hand, amazingly plastic, and on the other, possessing the finest and most precise contours. And such activities were consciously sought to be carried out by such people as Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. However, it is also necessary to remember the following. nine0005

These thinkers felt compelled to use all their sharp thinking to logically prove the dogmas already accepted by the church. On the other hand, they sought to bring clarity to them, to reach more definite answers than, for example, the one that was given by half-hearted ecclesiastical Pelagianism. This is what distinguishes the works of thinkers of high scholasticism from the writings of the Fathers of the Church, from patristics. In the thinking of Albert and Thomas, semi-conscious impulses also acted, emanating from the figure of Dionysius the Areopagite, whose teaching in some mysterious way poured into European spiritual life from the 6th century, and then through the thinkers of the 7th and 8th centuries reached Thomas Aquinas. The writings of Dionysius the Areopagite contain the Neoplatonism of Plotinus, but in a special form and in a completely Christian interpretation. According to Dionysius the Areopagite, two paths of knowledge lead to the Divine. On one of them, one must extract from the things of the external world the essential, perfect contained in them, in order to approach Superperfection itself in this way. For it once poured out into world existence, differentiated and individualized in its accomplishments and in its things. Thus, one can approach a certain idea of the Divine.

This is what distinguishes the works of thinkers of high scholasticism from the writings of the Fathers of the Church, from patristics. In the thinking of Albert and Thomas, semi-conscious impulses also acted, emanating from the figure of Dionysius the Areopagite, whose teaching in some mysterious way poured into European spiritual life from the 6th century, and then through the thinkers of the 7th and 8th centuries reached Thomas Aquinas. The writings of Dionysius the Areopagite contain the Neoplatonism of Plotinus, but in a special form and in a completely Christian interpretation. According to Dionysius the Areopagite, two paths of knowledge lead to the Divine. On one of them, one must extract from the things of the external world the essential, perfect contained in them, in order to approach Superperfection itself in this way. For it once poured out into world existence, differentiated and individualized in its accomplishments and in its things. Thus, one can approach a certain idea of the Divine. nine0005

nine0005

The other path is the path of denial, when a person rejects everything that relates to the things of the external world, erases from his consciousness all their usual names (concepts) and, thus, enters into a special state of mind in which he is more knows nothing about the world of external senses. And if in this state of mind a person retains the ability to have conscious experiences, then he will find himself in front of the Inexpressible, which cannot be designated by any name, by any concept. Then he will know God, the Superdeity (übergott) in his highest beauty (überschönheit). But these sublime names themselves are misleading, being only allusions to the experience of such a person of the Inexpressible. So, Dionysius the Areopagite gives, one might say, simultaneously two theologies - firstly, a rationalistic, positive and, secondly, a mystical theology of negation. If one follows only the first path of cognition, it turns out that it can be said to be lost in the divine space. They don't come to God. But, nevertheless, it is necessary to follow this path, because without passing it one cannot come to God. The second path of cognition, striving towards the Inexpressible, does not by itself lead to the Divine. But if you go through both of these paths of knowledge, then at the point of their intersection you find God. Both of these ways of knowing are true, but only in their totality. nine0005

They don't come to God. But, nevertheless, it is necessary to follow this path, because without passing it one cannot come to God. The second path of cognition, striving towards the Inexpressible, does not by itself lead to the Divine. But if you go through both of these paths of knowledge, then at the point of their intersection you find God. Both of these ways of knowing are true, but only in their totality. nine0005

The wisdom of Dionysius the Areopagite found its last revelation in the personality of Scotus Erigena. According to legend, in the last years of his life he was the prior of a Benedictine monastery and was killed by his own monks, outraged by the teaching he preached. In 1225, his writings were declared heretical by the decision of Pope Honorius and publicly burned at the stake in Paris. His translations of the writings of Dionysius the Areopagite from Greek into Latin were first printed several times at the end of the 16th century, and his own works were published only at the end of the 17th century. However, both Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas were deeply influenced by the ideas of Scotus Erigena, and indirectly through them by Dionysius the Areopagite and Plotinus. The true meaning and meaning of the writings of Plotinus are revealed to modern man only if he considers them in the light of the data of today's spiritual science. On the unprepared reader, his works, as well as their presentation by other authors, give the impression of chaos and ornateness (kraus). nine0005

However, both Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas were deeply influenced by the ideas of Scotus Erigena, and indirectly through them by Dionysius the Areopagite and Plotinus. The true meaning and meaning of the writings of Plotinus are revealed to modern man only if he considers them in the light of the data of today's spiritual science. On the unprepared reader, his works, as well as their presentation by other authors, give the impression of chaos and ornateness (kraus). nine0005

Meanwhile, Aristotle's teaching on the composition of the human being seems to be somehow rationalized, rather even a translation into physical concepts of those ancient views of a supersensible origin that were still in Plato, and subsequently surfaced again in Plotinus. In Aristotle we find, in fact, a systematic description of the supersensible mysteries of the composition of the human being. So, for example, Aristotle distinguished between the active mind (Nous poietikos), the human mind and his suffering mind (Nous pathetikos). Subsequently, Plotinus will speak about the same thing, but in his own way. At the time when Platonism was alive, or at least its rationalistic filtrate - Aristotelianism, individual self-awareness did not yet reach the degree of development in a person that later entailed the formulation of cardinal problems put forward by thinkers of high scholasticism. What we now call reason, human intellect, dates back (even terminologically) to the period of high scholasticism. Intelligence is a manifestation of the individual man. Or, in other words, logical and dialectical thinking is a manifestation of a universally human, but individually differentiated organization. When a person already feels himself an individual, he says to himself: thoughts arise in a person, they represent the outside world inside him; in their totality they give a reflection of the external world. On the one hand, representations associated with individual, specific beings and things appear and work inside a person, and on the other hand, general concepts: “man in general”, “wolf in general”, etc.

Subsequently, Plotinus will speak about the same thing, but in his own way. At the time when Platonism was alive, or at least its rationalistic filtrate - Aristotelianism, individual self-awareness did not yet reach the degree of development in a person that later entailed the formulation of cardinal problems put forward by thinkers of high scholasticism. What we now call reason, human intellect, dates back (even terminologically) to the period of high scholasticism. Intelligence is a manifestation of the individual man. Or, in other words, logical and dialectical thinking is a manifestation of a universally human, but individually differentiated organization. When a person already feels himself an individual, he says to himself: thoughts arise in a person, they represent the outside world inside him; in their totality they give a reflection of the external world. On the one hand, representations associated with individual, specific beings and things appear and work inside a person, and on the other hand, general concepts: “man in general”, “wolf in general”, etc. nine0005

nine0005

Thinkers of high scholasticism called them, following the ancient word usage, "universals". They clearly realized that these latter are primarily concepts, collective concepts formed by man within his individual being. Indeed, if we look at the world around us, we will find there not “a person in general”, not a “type of wolf nature”, but individual people, individual wolves, etc. But, on the other hand, if you put a wolf in a cage and feed him only lambs, then despite the fact that, as you know, after a certain time, as a result of metabolism, all the matter from which the wolf’s flesh is formed will be replaced by matter belonging to lambs, - despite this, the wolf, nevertheless, will not become a lamb, but will remain as before a wolf. From this it follows that "wolf nature" as a type cannot be reduced to the material composition, to the physical corporality of the wolf. nine0005

This problem of the connection of "universals" with individual things, with the beings of the world of external senses, was exceptionally acute precisely in the heyday of scholasticism. For it directly affected the interests of the church. The fact is that back in the 11th-12th centuries, such thinkers as, for example, Roscelinus, came forward, who argued the following. These general concepts, these "universals" are nothing more than words, names, by means of which we designate, distinguish things in the world around us that have some common features. This is how the doctrine of "nominalism" arose. Roscelin, with dogmatic seriousness, applied the philosophy of nominalism to the Christian doctrine of the Divine Trinity: if - what he considered true - generalization, unification in one (Zusammenfassung), is only a word, a name, then the Trinity is also only a word, and the only real are Individuals: Father , Son and Holy Spirit. But the human mind comprehends them only through their names. - Medieval thinkers then brought these things to the final conclusions. The church, at the synod in Soissons, declared this doctrine heretical as partial polytheism. nine0005

For it directly affected the interests of the church. The fact is that back in the 11th-12th centuries, such thinkers as, for example, Roscelinus, came forward, who argued the following. These general concepts, these "universals" are nothing more than words, names, by means of which we designate, distinguish things in the world around us that have some common features. This is how the doctrine of "nominalism" arose. Roscelin, with dogmatic seriousness, applied the philosophy of nominalism to the Christian doctrine of the Divine Trinity: if - what he considered true - generalization, unification in one (Zusammenfassung), is only a word, a name, then the Trinity is also only a word, and the only real are Individuals: Father , Son and Holy Spirit. But the human mind comprehends them only through their names. - Medieval thinkers then brought these things to the final conclusions. The church, at the synod in Soissons, declared this doctrine heretical as partial polytheism. nine0005

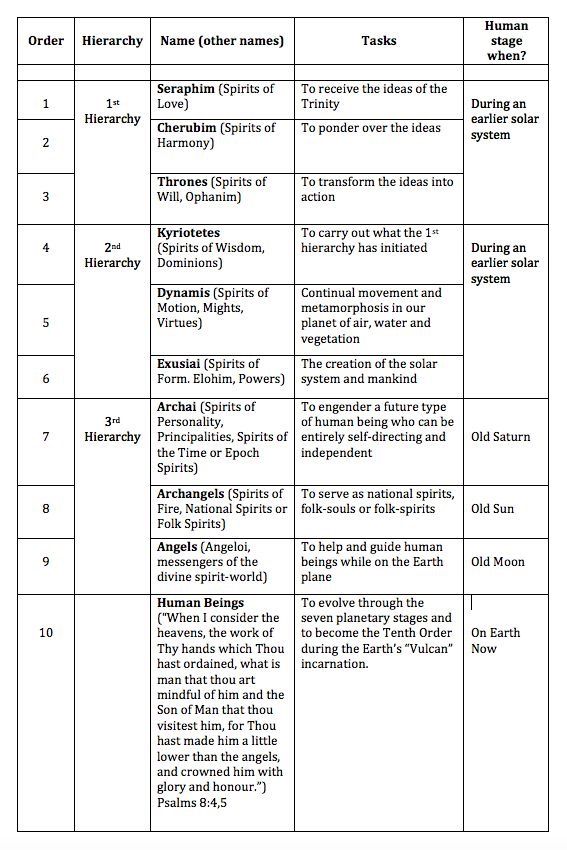

Nominalism was opposed, being church leaders, first Albert the Great, then Thomas Aquinas - mainly as a philosopher. The spiritual tradition was still active in them, ascending through Scot Erigen to Dionysius the Areopagite, to Plotinus. They still knew that there were people who could rise above concepts and really see the spiritual world. Thomas Aquinas also spoke of him as a kind of reality. There, he said, there are not just abstractions, there are real spiritual beings, free from material bodies; he calls them Angels and places them in a region he calls the Tenth World Sphere. For Albertus Magnus and for Thomas Aquinas, it was the object of a kind of belief that there is something Higher above abstract concepts, of which these abstract concepts are the revelation. And for them the question arose: what kind of reality do these abstract concepts have? They proceeded from the idea that the surrounding world of external senses is a kind of revelation of higher spiritual worlds. nine0005

The spiritual tradition was still active in them, ascending through Scot Erigen to Dionysius the Areopagite, to Plotinus. They still knew that there were people who could rise above concepts and really see the spiritual world. Thomas Aquinas also spoke of him as a kind of reality. There, he said, there are not just abstractions, there are real spiritual beings, free from material bodies; he calls them Angels and places them in a region he calls the Tenth World Sphere. For Albertus Magnus and for Thomas Aquinas, it was the object of a kind of belief that there is something Higher above abstract concepts, of which these abstract concepts are the revelation. And for them the question arose: what kind of reality do these abstract concepts have? They proceeded from the idea that the surrounding world of external senses is a kind of revelation of higher spiritual worlds. nine0005

And when we study the surrounding world, individual minerals, plants and animals, we somehow foresee that they contain something that goes back to the higher spiritual worlds. Observing, studying the world of the kingdoms of nature, resorting to our ability of thinking, logical reason, we must understand the following. We turn our eyes, other organs of our external senses to the world around us and enter into a relationship with this world. Then we turn away (weg gehen) from him. And in a certain way we preserve - as a memory - what we have received from this external world. But here we are again looking inside ourselves at this memory. And then, for the first time, the universal appears before us, that general, which is “man in general”, “wolf in general”, etc.; it appears for the first time in an internal, conceptual form. And this is what Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas say here: “When you turn to what your soul reflects to you from what it experienced in the outside world, you are dealing with universals living in your soul. From the memory of all the people you have met, you form the concept of "man in general." You have here universals that live in the soul after it has perceived the things of the external world.

Observing, studying the world of the kingdoms of nature, resorting to our ability of thinking, logical reason, we must understand the following. We turn our eyes, other organs of our external senses to the world around us and enter into a relationship with this world. Then we turn away (weg gehen) from him. And in a certain way we preserve - as a memory - what we have received from this external world. But here we are again looking inside ourselves at this memory. And then, for the first time, the universal appears before us, that general, which is “man in general”, “wolf in general”, etc.; it appears for the first time in an internal, conceptual form. And this is what Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas say here: “When you turn to what your soul reflects to you from what it experienced in the outside world, you are dealing with universals living in your soul. From the memory of all the people you have met, you form the concept of "man in general." You have here universals that live in the soul after it has perceived the things of the external world. A person then experiences in these things [their]* the spiritual principle; but only he translates it into the form of "universal post rem" (Universalien post rem). nine0005

A person then experiences in these things [their]* the spiritual principle; but only he translates it into the form of "universal post rem" (Universalien post rem). nine0005

So, Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas believe that at the moment when a person cognizes the surrounding world through his ability to think, he cognizes something real. Due to the fact that a person does not remain only with what his eyes see, his ears hear, and so on, for example, in a wolf, but can still think about him, form in himself the concept of “wolf in general”, about “the type of wolf nature ”, - thanks to this, he experiences something in things that is not exhausted by the perceptions of external senses, but can be comprehended in them mentally. He experiences "universals in rebus" (in rebus). According to Aquinas, a clear distinction must be made between "universalia post rem" and "universalia in rebus". What a person experiences in his soul as an idea, operating with his reason, is that through which he experiences the real in the things of the world. Thus, as regards the form [manifestation], the "universals in rebus" are different from the "universals post rhem", which then remain in the soul; but inwardly they are the same. In addition, one should also distinguish between "universals ante pec" (Universalia ante res), which preceded the things of the world of external senses. nine0005

Thus, as regards the form [manifestation], the "universals in rebus" are different from the "universals post rhem", which then remain in the soul; but inwardly they are the same. In addition, one should also distinguish between "universals ante pec" (Universalia ante res), which preceded the things of the world of external senses. nine0005

They differ in form from the "universals in rebus", but in content they are, again, the same. These are universals residing in the Divine mind, as well as in the mind of angelic spiritual beings serving God. That which for the people of antiquity, as well as for Plotinus and then for Dionysius the Areopagite, was a direct spiritual-sensory-supersensory perception of the realities of the spiritual world and which, according to Dionysius the Areopagite, could not be designated by any name, concept without distorting its true image , - this has now become the subject of the most subtle logical reasoning, reflections among the thinkers of scholasticism. The problem, which was previously solved by clairvoyance, by means of supersensible perceptions, now descended into the sphere of thinking, into the sphere of the activity of reason. This is the essence of the philosophy of Albert the Great and the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas - the essence of high scholasticism in general, which became the product of that era when a person's inner experience of his individuality reached its culmination. nine0005

The problem, which was previously solved by clairvoyance, by means of supersensible perceptions, now descended into the sphere of thinking, into the sphere of the activity of reason. This is the essence of the philosophy of Albert the Great and the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas - the essence of high scholasticism in general, which became the product of that era when a person's inner experience of his individuality reached its culmination. nine0005

The development of scholasticism was inextricably linked with the church life of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. For the thinkers of that time, it was true, on the one hand, that which can be obtained through thinking, through the most accurately thought out logic, and on the other hand, that which was the content of faith, which was preserved and transmitted as church dogmas.

Let us consider what position such a thinker as Thomas Aquinas took with respect to both. He wondered: "Can the existence of God be proved by logic?" And he answered: “Yes, you can!”. Thomas Aquinas gave a number of logical proofs for the existence of God. In one of them, he - and before him already Albert the Great - adjoins Aristotle's logical conclusion about God as the immovable Mover of the world. God is the Necessarily Existing First Essence, the necessary immovable Primal Mover: this is how God appears to logical thinking. nine0005

Thomas Aquinas gave a number of logical proofs for the existence of God. In one of them, he - and before him already Albert the Great - adjoins Aristotle's logical conclusion about God as the immovable Mover of the world. God is the Necessarily Existing First Essence, the necessary immovable Primal Mover: this is how God appears to logical thinking. nine0005

No logical train of thought can lead to the Divine Trinity. But the idea of the Divine Trinity has been handed down to us by religious tradition. And with regard to this idea, human thinking can only go so far as to subject it to a logical test - isn't this idea nonsense? And then they logically find that the idea of the Divine Trinity is not meaningless, but at the same time it is logically and unprovable; one can and should only believe in it. Thus stood the thinkers of scholasticism before the question of great significance for them: how far can one advance with human reason left to itself? At that time there were church thinkers who said that some propositions can be true theologically and, at the same time, false philosophically. They considered it quite acceptable that the human mind could come to quite different conclusions than those conveyed by the content of faith: for example, it could consider the idea of the Divine Trinity meaningless. This was the doctrine of double truth (doppelte Wahrheit). nine0005

They considered it quite acceptable that the human mind could come to quite different conclusions than those conveyed by the content of faith: for example, it could consider the idea of the Divine Trinity meaningless. This was the doctrine of double truth (doppelte Wahrheit). nine0005

And this is what Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas emphasized in their teachings: there is no contradiction between the content of faith and the knowledge obtained by human reason; full agreement can be established between them. True, human reason can only reach a certain limit, beyond which the content of faith already exists, but there is no contradiction between them. At the time, this represented a radical position. For most of the leading church authorities then firmly adhered to the doctrine of twofold truth. Echoes of all this are alive today. So, the main problem for Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas was the relationship between rational knowledge and the content of faith. How can one achieve, firstly, to understand intellectually what the church believes in and, secondly, to defend it against its opponents? - In this regard, Albert and Foma have done a lot. At that time, not only church dogmas were in circulation in Europe, but also views related to the spread of Islam; something also remained of Manichaean ideas. nine0005

At that time, not only church dogmas were in circulation in Europe, but also views related to the spread of Islam; something also remained of Manichaean ideas. nine0005

The 12th century Arab thinker Averroes taught the following. What a man thinks by means of his pure intellect does not belong exclusively to him personally, but belongs to all mankind as a whole. Person "A" has his own body, but his mind is common to both person "B" and person "C" and so on. We can say that for Averroes, humanity as a whole has one single mind, in which all individuals are immersed and from which they draw their thoughts. In it they live in some way with their heads. When they die, their bodies are removed from this universal mind. Therefore, there is no immortality in the sense of the continuation of the individual consciousness of a person after death. Only the universal reason inherent in humanity as a whole always continues to exist. nine0005

For Thomas Aquinas the situation was as follows. He recognized the universality of reason; however, at the same time, he stood on the point of view that the universal mind is internally connected not only with what is an individual memory in an individual person, but that during the life of this person it is also connected with the active forces of the human bodily organization. Forming in this way a kind of unity, it unites with itself everything that acts in man as formative vegetative forces, as forces of animal nature, as forces of memory; all this during the earthly life of a person turns out to be to some extent permeated and transformed not only by the universal mind, but also by the moral system. According to Thomas Aquinas, a person transforms his individuality thanks to the universal spiritual principle and then brings this after his death into the spiritual supersensible world. Thus, in Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas there was no question of the pre-existence (Praexistenz) of the human "I"; however, his posthumous existence (Postexistenz) was recognized.

He recognized the universality of reason; however, at the same time, he stood on the point of view that the universal mind is internally connected not only with what is an individual memory in an individual person, but that during the life of this person it is also connected with the active forces of the human bodily organization. Forming in this way a kind of unity, it unites with itself everything that acts in man as formative vegetative forces, as forces of animal nature, as forces of memory; all this during the earthly life of a person turns out to be to some extent permeated and transformed not only by the universal mind, but also by the moral system. According to Thomas Aquinas, a person transforms his individuality thanks to the universal spiritual principle and then brings this after his death into the spiritual supersensible world. Thus, in Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas there was no question of the pre-existence (Praexistenz) of the human "I"; however, his posthumous existence (Postexistenz) was recognized. In this they followed Aristotle, developed Aristotelianism. So, the great logical questions about universals connected with the problem of the cosmic fate of an individual person. nine0005

In this they followed Aristotle, developed Aristotelianism. So, the great logical questions about universals connected with the problem of the cosmic fate of an individual person. nine0005

For Thomas Aquinas, it was very characteristic and important that, while working hard in search of proofs of the existence of God, he simultaneously came to the following conclusion: by the rational way, which is accessible to the human soul, one can only come to the idea of the Deity, which in the Old Testament according to rightly called Yahweh. If, however, they want to come to Christ, then it is necessary to move on to the content of faith, for they do not experience Him within the limits of their own spiritual content; in this way, for example, one cannot come to the comprehension of the incarnation of Christ, and so on. In this connection, it must be said that those church leaders who spoke of twofold truth did not at all adhere to the view that truth is ultimately twofold. No, they believed that theological revelations and the achievements of rational knowledge only temporarily turn out to be contradictory; and man has to deal with two opposite truths only because he once fell into original sin, down to the innermost core of his soul. nine0005

nine0005

This question flickers in a certain way in the underlying foundations of the soul of both Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas: yes, are we not involved in our thinking - what we experience in ourselves as mind - in original sin? Is it not because our reason has fallen away from the spiritual principle that it conjures up for us as truths that which differs from genuine truths? And so, if we accept Christ into our mind, if we accept into our mind something that transforms this mind and lifts it forward, upward, only then will its knowledge be in agreement with the truth that constitutes the content of faith. Just the fall of reason was in a certain sense the justification for the fact that the thinkers who preceded Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas spoke of two truths. They believed that our reason fell under original sin and therefore may conflict with the pure truth of faith. nine0005

Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas spoke. According to their ideas, it would be wrong to think that when we delve into “universals in rebus” in a purely logical way, that is, when we perceive into ourselves what is really contained in the things of the surrounding world, then we supposedly sin against the truth. This is what stood as the main question in the period of high scholasticism and what remained unresolved by it: what images does Christ enter into human thinking? How does the human mind become permeated with the Christ Impulse? In what way does Christ lead the proper human thinking upward - to that sphere where it can unite with that which is the spiritual content of faith? nine0005

This is what stood as the main question in the period of high scholasticism and what remained unresolved by it: what images does Christ enter into human thinking? How does the human mind become permeated with the Christ Impulse? In what way does Christ lead the proper human thinking upward - to that sphere where it can unite with that which is the spiritual content of faith? nine0005

Therefore, Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas were forced to deny the human mind the right to step over those steps that can lead the mind itself into the spiritual world. For high scholasticism, the question remained unresolved: in what way can human thinking develop in order to achieve the perception of this spiritual world?

And the most important result of high scholasticism is not even what exists as its entire content, but what confronts it as a central question. And that question was: How can Christology be introduced into thinking? How can thinking be permeated with the Christ principle? nine0005

This question is world-historically at the moment when Thomas Aquinas dies in 1274. By this time, he could only break through to the point of posing the question. And this question, with all heartfelt sincerity, then stood in the European spiritual culture. What he is to become could at first be outlined only in such a way that it was said that man, to a certain extent, penetrates into the essence, into the spiritual essence of things. But then the content of faith must follow. Both should not only contradict each other, they should be in mutual agreement (Konkordanz). However, the ordinary human mind cannot comprehend the content of higher objects - say, the Trinity, the incarnation of Christ in the man Jesus, and so on, relying only on itself. The understanding can advance in knowledge only so far as to say, for example: the world could have arisen (etntstanden) in time, but it could also have endured from eternity. However, Revelation says that it originated in time. And if you [having recognized this in Revelation] again ask your mind, you will now find the basis why the arising in time is reasonable, wise.

By this time, he could only break through to the point of posing the question. And this question, with all heartfelt sincerity, then stood in the European spiritual culture. What he is to become could at first be outlined only in such a way that it was said that man, to a certain extent, penetrates into the essence, into the spiritual essence of things. But then the content of faith must follow. Both should not only contradict each other, they should be in mutual agreement (Konkordanz). However, the ordinary human mind cannot comprehend the content of higher objects - say, the Trinity, the incarnation of Christ in the man Jesus, and so on, relying only on itself. The understanding can advance in knowledge only so far as to say, for example: the world could have arisen (etntstanden) in time, but it could also have endured from eternity. However, Revelation says that it originated in time. And if you [having recognized this in Revelation] again ask your mind, you will now find the basis why the arising in time is reasonable, wise. nine0005

nine0005

This is how a great scholastic appears as belonging to an entire era. And much more than people think, in all of today's science, in all the social life of modernity, that which has been preserved from scholasticism still lives - however, of course, in a peculiar way. How alive, in essence, scholasticism is in our souls and what position, in fact, modern man should take in relation to what still lives today from scholasticism - we will talk about this tomorrow.

Rudolf Steiner. Psychosophy. Lecture 3, part 1: philologist — LiveJournal

Lecture Three AT THE GATES OF THE SENSES, SENSE, AESTHETIC JUDGMENTNovember 3, 1910, Berlin

This lecture we will again begin with a recitation of a poetic work, which will serve us to illustrate some of the things that I will be expounding today and tomorrow. This time we are talking about the poem of one "non-poet", because in relation to the other spiritual activity of this person, this poem is a side occasion for his spiritual activity. This is thus the case when we are dealing with some soul revelation which does not flow directly from the intimate impulses of that soul. Just this fact makes it possible to consider especially well everything related to our topic. The poem belongs to the philosopher Hegel and deals with questions of the initiation of mankind. nine0005

This is thus the case when we are dealing with some soul revelation which does not flow directly from the intimate impulses of that soul. Just this fact makes it possible to consider especially well everything related to our topic. The poem belongs to the philosopher Hegel and deals with questions of the initiation of mankind. nine0005

ELEVSIN

Around me, peace lives in me. Busy people

Tired care never sleeps. She gives freedom

And due to me. Thank you, my liberator,

Oh night! With a white veil of mist

The moon surrounds the vague boundaries of the distant hill.

The light watch of the sea gleams friendly.

The boring anxieties of the day are fading into memory,

As if they lay between then and now.

Your image, beloved, passes before me,

And the weight of the day flies away. And yet she soon muffles

Goodbye sweet hopes.

The scene of mutual gaze is already drawn to me,

Complete enigmatic questioning,

What has changed there in the posture, expression, feeling of a friend.

Confidence of bliss, fidelity of the old union

Find a more solid, mature,

Union, not marked by an oath.

Live only free truth

And never try to regulate

Peacefulness, opinions and feelings by no charter!

After all, from all reality, over mountains, rivers

Easily carries me to you feeling.

A groan heralds about his strife, and with it

A dream of sweet fantasies flies away.

My gaze ascends to the eternal sky,

To you, O shining luminary of the night!

And all desires, all hopes

Oblivion flows from your eternity.

The feeling is lost in contemplation,

What I called mine disappears.

I commit myself to infinity.

I am in it, everything is there, only this is.

The mind shuns recurring thoughts,

He is frightened by infinity and is surprised

Does not comprehend the depth of contemplation.

Fantasy brings him closer to the eternal,

Taking shape. — Please, you,

Exalted spirits, lofty shadows,

Whose forehead radiates perfection,

Do not be afraid. I feel this is also my Fatherland,

I feel this is also my Fatherland,

Shine, seriousness, enveloping you.

Aha, the gates of your sanctuary are thrown open,

O Ceres, crowned in Eleusis!

I feel intoxicated with inspiration,

Contemplating your closeness

And listening to your revelations.

I comprehend the high meaning of images, I perceive

Hymns at the table of the Gods,

High sayings of your advice.

And yet your halls are empty, O Goddess!

The gods hastily returned to Olympus

Away from the desecrated altars.

Away from humanity's desecrated grave

Innocence of the Genius enchanted there.

The wisdom of your priests is silent,

And no church service will help us.

In vain for curiosity want to see

Love of wisdom. Seekers have it and despise you. nine0009 To master it, they hide it in words,

In which your high mind was imprinted!

In vain! They seize only ashes and ashes,

Where your life never returns.

Among the ashes of soullessness you can find

Eternally dead, self-sufficient. In vain abide

In vain abide

Deprived of signs of your solidity, traces of your image.

The fullness of the teaching of the son of initiation,

The depth of inexpressible feeling is much more healing than

Dry signs and expressions.

The thought no longer captures the soul,

Which is beyond space and time, in anticipation of the Infinite

Immersed, forgets itself and awakens again

To consciousness. Who would like to talk about this with another,

Should have spoken in angelic language, feeling

The poverty of words. He is afraid to think the sacred

So modest, to belittle it with words, so that speech

Plunges him into sin. And he tremblingly

Closes his mouth. What the initiate forbids

to himself, the wise law

forbids to the poor in spirit, which informs that

What he saw, heard, felt on a sacred night.

He does not allow verbal rubbish

To harm his piety and to disturb him

The noise of wickedness...

Thus, it might seem that mental life was characterized by something that is not characteristic of it, that is, without any attention to what, agitating here and there, rising and falling, gives mental life a character corresponding to it: the life of feelings. nine0005

Thus, it might seem that mental life was characterized by something that is not characteristic of it, that is, without any attention to what, agitating here and there, rising and falling, gives mental life a character corresponding to it: the life of feelings. nine0005 We will see later that it is precisely the dramatic content of psychic life that we will be able to understand if we approach feeling from both of the above-considered elements of psychic life. We must again begin with the simple facts of psychic life. These are sensory experiences received through the gates of our sense organs, which penetrate into our soul life and lead their own existence there. Compare the fact that our soul life rushes its waves to the gates of the senses and then from these gates of the senses receives into itself the results of sensory perceptions, which then lead an independent life in the soul - compare this fact with another, that also everything that is contained in the experience of love and hate, which springs from desire, rises, as it were, from the inner life of the soul itself. Desires arise, as it were, from the concentration of spiritual life for superficial observation, which to a superficial observer appear to be the cause of love and hatred. nine0005

Desires arise, as it were, from the concentration of spiritual life for superficial observation, which to a superficial observer appear to be the cause of love and hatred. nine0005

But desires themselves are not to be sought first in the soul. You can't find them there. They ascend to the gates of the senses! Pay attention to this first. Look at your daily spiritual life and you will soon notice how the manifestation of desire for the outer world rises in you! So, you can say: a much larger volume of our spiritual life is formed on the border of the sensible, in the gates of the senses. At the same time, we can understand ourselves more thoroughly if we graphically depict what we know as a fact. We can well characterize psychic life in its interior if we consider it located within a circle (see figure). nine0005

So, let's think about the fact that the interior of a certain circle represents the content of our spiritual life. Let us think further that the sense organs are some kind of gate, an opening to the outside, as you may have learned from the lectures on Anthroposophy. Let us consider the very thing that is observed only in our soul, if we want to depict it internally graphically: then from the center and into all aspects of spiritual life we let the stream flow, which is outlived in love and hatred. We see how the soul is overflowing with desires and how this stream falls into the gates of the senses. Now we can ask ourselves: what is experienced where sensory experience intervenes? What happens when sound is experienced through the ear? What happens when smelling through the nose? nine0005

Let us consider the very thing that is observed only in our soul, if we want to depict it internally graphically: then from the center and into all aspects of spiritual life we let the stream flow, which is outlived in love and hatred. We see how the soul is overflowing with desires and how this stream falls into the gates of the senses. Now we can ask ourselves: what is experienced where sensory experience intervenes? What happens when sound is experienced through the ear? What happens when smelling through the nose? nine0005

At first, we will leave the outside world in relation to the content. Grab once again, on the one hand, the moment in which sensory perception takes place, that is, take this relationship with the external world. Be transported vividly to that moment in which, so to speak, the soul experiences itself inwardly, through the gates of the senses in the external world has the experience of color or sound. On the other hand, think about the fact that the soul lives further in time and, as representations in memory, retains for itself what it, as it were, captured in sensory experience. nine0005

nine0005

Thus, we must strictly distinguish between what the soul carries on, in the representation of memory as an ongoing experience, and the experience of the activity of sensory experience; otherwise we will fall into the channel of Schopenhauer's thinking. Now let us ask ourselves: what happened at the moment when the soul was temporarily left to the outer world through the gates of the senses? If you think about the fact that our soul is indeed, as direct experience testifies, flooded with a flood of desires, and ask: what then, in fact, strikes at the gates of the senses, while the soul allows its inner to reach the gates of the senses? are desires themselves. This desire is announced, and physically it comes into contact with the outside world at this moment. And this desire keeps an imprint on the other side, as it were! If I make an impression of the seal with the name Müller in the wax mass, then what will remain of the seal in the sealing wax? Nothing but the surname Muller. nine0005

nine0005

You cannot say that what is imprinted in sealing wax does not agree with what is acting in the outside world. Otherwise it would not be an unbiased observation, but Kantianism. If you do not want to look (only) at the outwardly material, then you cannot say (should not say) that the seal itself is not included in the sealing wax, but you must look at what is important here, namely, what is in the sealing wax the surname Müller is present. The important thing is that in this way the name Müller resists on the seal and in which the word Müller is imprinted, just as the press does not lose anything from itself, only the name (except the name) Müller, so the outside world does not give anything else, as soon as imprint. But for imprinting to take place, something is needed to resist. So, you can say: in that which is opposed to sensory experience, an impression is formed from the outside and then that which, as an imprint, has arisen in one's own soul life, is grasped. It is not the color or sound itself that is grasped, but what is there as an experience of love or hate, of desire itself. nine0005

nine0005

Is this also correct? Is there anything in direct sensory experience that, as a kind of desire, must strive outward? Yes, if this were not the case, then you could not (would) take the sensory experience into a further psychic life, and then the idea could never arise in memory. There is precisely a fact of the soul, which is a direct proof that desire from the soul always knocks outward through the gates of the senses when color, sound, smell, etc. are perceived. nine0009 This is a fact of mindfulness. The difference that exists between such a sensory impression, when we barely touch a thing with a distracted glance, and such an impression, when we turn to a thing with all attention, shows us that the impression from a superficial glance does not carry over into later spiritual life. It is necessary from within to direct the power of attention towards the thing, and the greater this attention, the more easily the soul carries the recollected idea into later life.

Thus, through the gates of the senses, the soul enters into such a relationship with the external world, in which the soul allows its substantial content to fall on the outer boundaries, and this manifests itself in the fact of attention. Another element of mental life, judgment, is excluded precisely at the moment of direct sensory experience. Sense impression is characterized by the fact that the faculty of judgment is excluded as such. Then desire makes itself the only actor, the sense impression of red is not the same as the sense perception of red. In sound, in the perception of color, in smell, there is only the desire witnessed by attention: the judgment in this case is suppressed. It is only necessary to be clear that between sensory perception and what happens next in the soul, there is an absolutely precise boundary. nine0005

Another element of mental life, judgment, is excluded precisely at the moment of direct sensory experience. Sense impression is characterized by the fact that the faculty of judgment is excluded as such. Then desire makes itself the only actor, the sense impression of red is not the same as the sense perception of red. In sound, in the perception of color, in smell, there is only the desire witnessed by attention: the judgment in this case is suppressed. It is only necessary to be clear that between sensory perception and what happens next in the soul, there is an absolutely precise boundary. nine0005

If you stop at a color impression, then you will be dealing only with a simple color impression, which is not yet accompanied by a judgment. Sense impression is characterized by the fact that the very disposition of attention excludes the possibility of judgment as such, so that desire becomes the only agent. If you surrender to the influence of color or sound, then only desire remains in this influence, while judgment is suppressed. The sense impression of red is not the same as the sense perception of red. In the sound, in the impression of a certain color, in the smell, there is only desire, witnessed by attention. Attention is a special form of desire. But the moment you say, "(This) is red," you have already made an act of judgment, the judgment in your soul has already entered into force. It is only necessary to be clearly aware of the need to draw an absolutely precise boundary between sensory perception and sensory sensation. Only if you stop at the color impression are you dealing with a simple correspondence of the desire of the soul with the outer world. nine0005

The sense impression of red is not the same as the sense perception of red. In the sound, in the impression of a certain color, in the smell, there is only desire, witnessed by attention. Attention is a special form of desire. But the moment you say, "(This) is red," you have already made an act of judgment, the judgment in your soul has already entered into force. It is only necessary to be clearly aware of the need to draw an absolutely precise boundary between sensory perception and sensory sensation. Only if you stop at the color impression are you dealing with a simple correspondence of the desire of the soul with the outer world. nine0005

What happens then at this meeting of desire in the soul with the external world? We distinguish between the sense of perception and the sense of sensation. We have called one the experience that occurs under direct influence, and the other is what remains. What do we thus have in sense-perception? With a sense of sensation, we bring in that which splashes and rages as a modification of desire, namely, the desired. Where does sensation arise? As we have already seen, it arises at the border of soul life with the external world, at the gates of the senses. nine0005

Where does sensation arise? As we have already seen, it arises at the border of soul life with the external world, at the gates of the senses. nine0005

(If judgment and desire within the soul want to come to rest on their own, then feeling arises.)

In fact, it is so that in sensual experience we say: the force of desire penetrates to the surface. However, suppose that the force of desire does not reach the boundary of the external world, that desire remains within the soul, it is, as it were, blunted by itself within the life of the soul, remains internal, does not strive to the threshold of the senses—what then arises? If the force of desire is attacked and forced to retreat into itself, then there is a sensation, a feeling. A sensory sensation, an external sensation, arises when this withdrawal into oneself is caused from the outside by means of a counterattack upon contact with the external world. An inner sensation arises when the desire is not pushed back directly by contact with the external world, but if it is thrown back somewhere within the soul without reaching the boundary. nine0005

nine0005