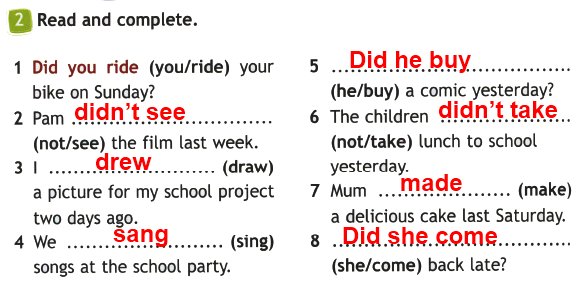

Does seroquel help anxiety

Seroquel May Help Depression, Anxiety

Antipsychotic Drug Already Used to Treat Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

Written by Charlene Laino

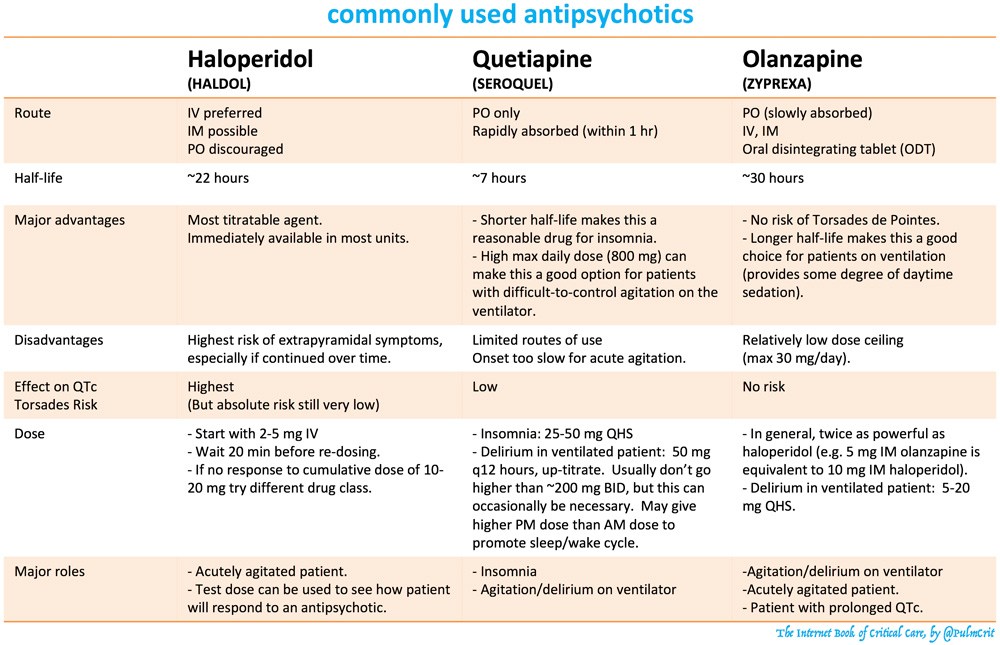

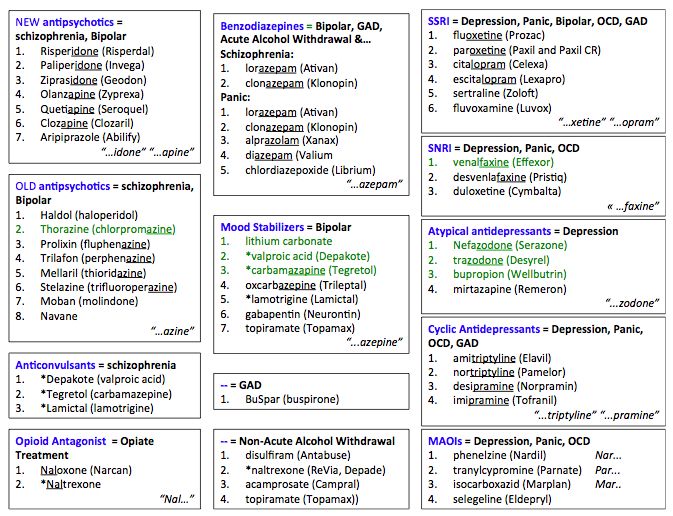

May 6, 2008 (Washington) -- The antipsychotic drug Seroquel may help battle major depression and generalized anxiety disorder, two new studies suggest.

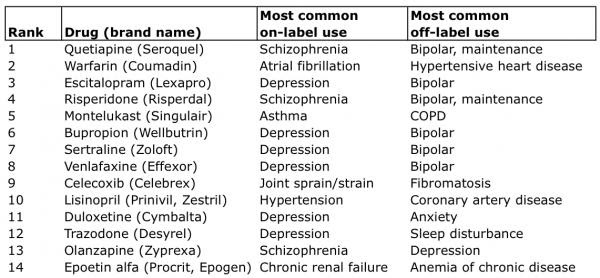

Seroquel is already approved to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (formerly called manic-depressive illness).

The new studies were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Major depression, which affects 15 to 19 million Americans, "is not just your typical blues. This is depression that lasts for a few weeks, even months," says researcher Richard Weisler, MD, of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and Duke University Medical Center.

One study involved more than 700 people who had suffered from depression for at least one month but less than one year.

Patients were randomly assigned to take one of three doses of Seroquel or a placebo once a day for six weeks.

Those taking Seroquel showed greater improvement in depression symptoms than those on placebo.

"There was improvement in all the things that are impaired when you're depressed -- sleep, appetite, suicidal thoughts," Weisler tells WebMD.

After six weeks of treatment, 25% were in remission, he says.

Importantly, patients on Seroquel experienced a significant improvement in depressive symptoms as early as the fourth day of treatment, Weisler says.

"Typically, patients don't respond until they have had at least two weeks of antidepressant therapy. And often it can take up to a month," he says.

Weisler says that in other studies looking at Seroquel for bipolar depression, "we noticed that patients' anxiety levels frequently dropped."

The observation led to a two-month study pitting Seroquel against placebo in nearly 1,000 patients with generalized anxiety disorder.

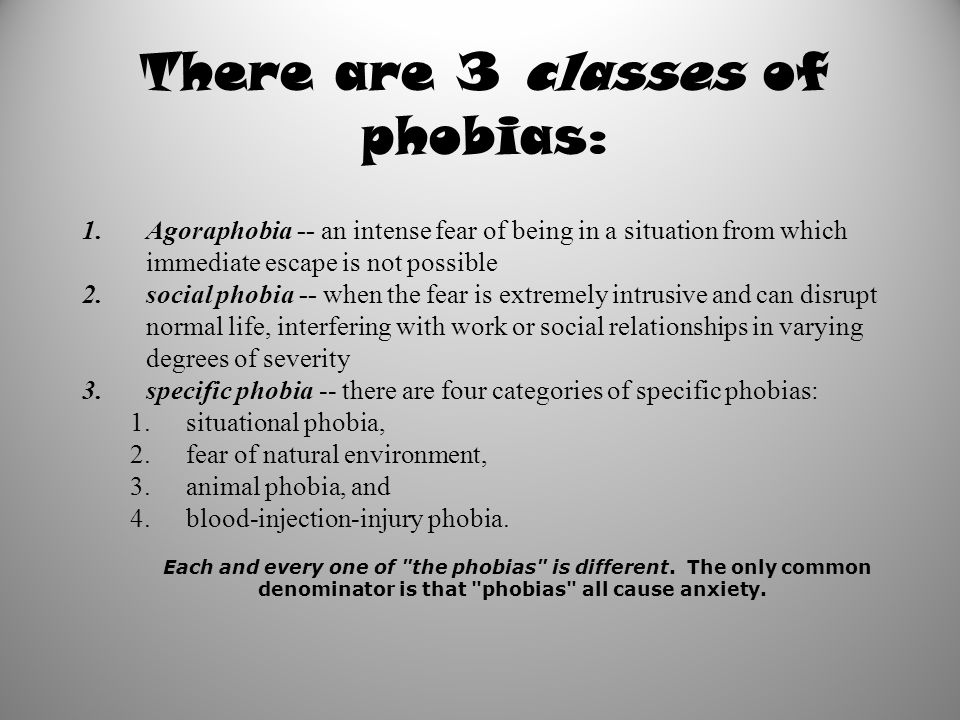

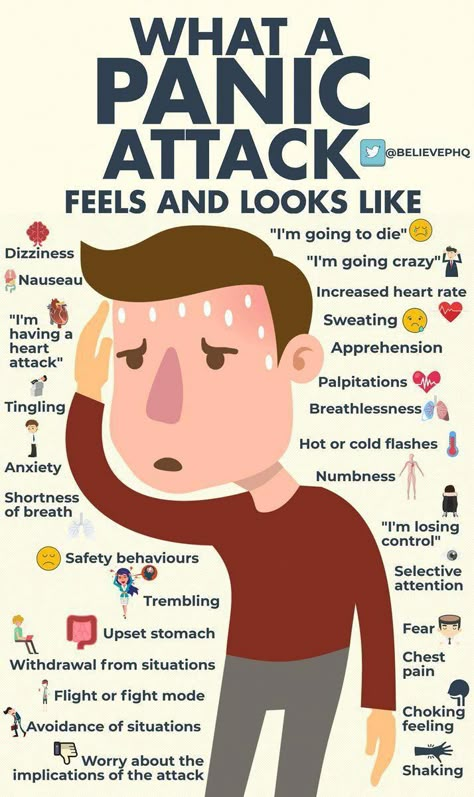

It's estimated that generalized anxiety disorder affects about 6.8 million Americans, with women twice as likely to be affected as men, according to the researchers.

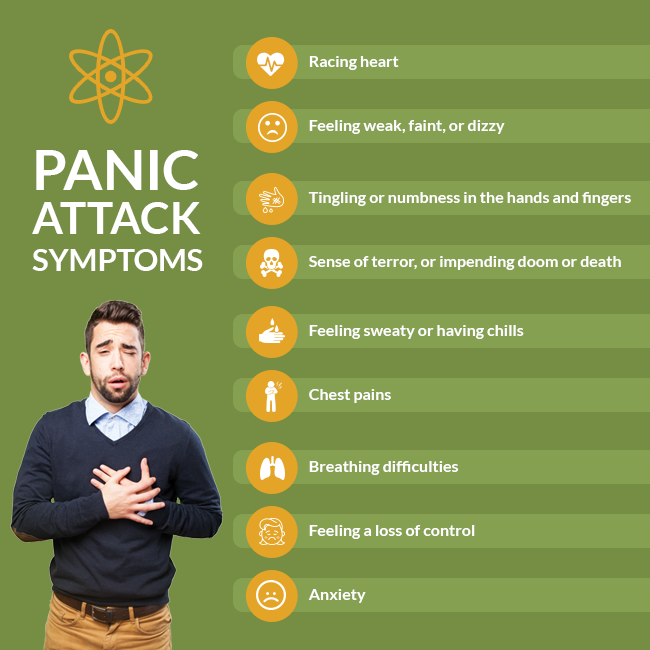

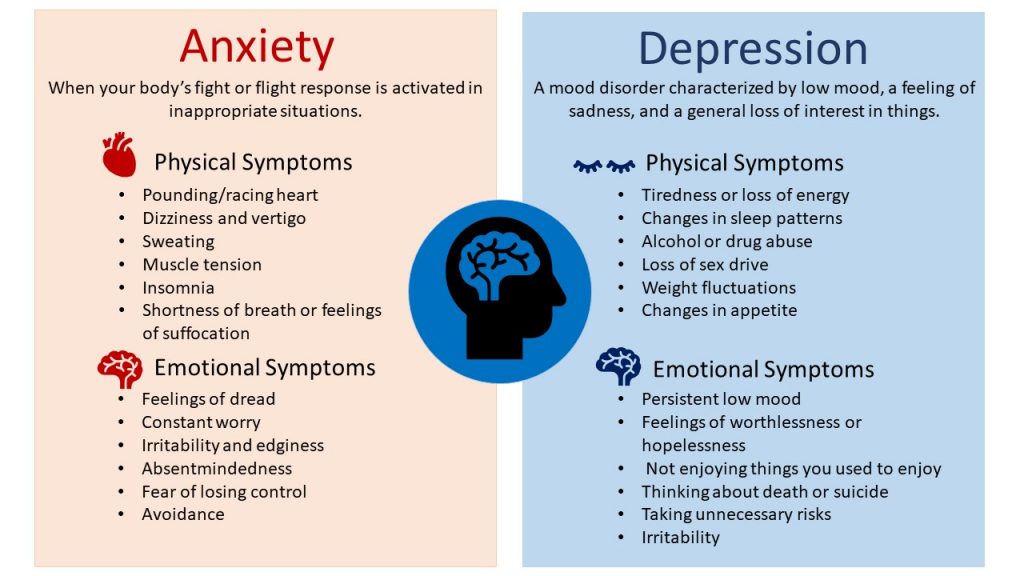

Symptoms, which can linger for six months or longer, include constant worry and anxiety about things most people take in stride. Sufferers often can't get rid of their concerns even though they realize their level of anxiety is out of proportion with the situation at hand.

By one week after the study started, anxiety symptoms, such as trouble sleeping and relaxing, began to improve in patients given Seroquel compared with those given placebo. That improvement continued over the course of the trial, Weisler says.

Seroquel was generally well tolerated in both studies, he says. The most common side effects included dry mouth, sedation, sleepiness, headaches, and dizziness.

Temple University's David Baron, DO, chairman of the committee that chose which studies to highlight at the meeting, says that new treatment choices for patients with major depression and anxiety are needed.

"A substantial proportion of patients don't respond to existing agents. Often patients who aren't helped by one drug will respond to another, even if it's in the same class," he tells WebMD.

AstraZeneca, the makers of Seroquel, funded the studies.

Quetiapine monotherapy in acute treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

1. Tyrer P, Baldwin D. Generalised anxiety disorder. Lancet. 2006;368(9553):2156–2166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole S, Huibers M, Berking M, Andersson G. Psychological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(2):130–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Szkodny LE, Newman MG, Goldfried MR. Clinical experiences in conducting empirically supported treatments for generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther. 2014;45(1):7–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Schmitt R, Gazalle FK, Lima MS, Cunha A, Souza J, Kapczinski F. The efficacy of antidepressants for generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2005;27(1):18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Kapczinski F, Lima MS, Souza JS, Schmitt R. Antidepressants for generalized anxiety disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD003592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kapczinski F, Lima MS, Souza JS, Schmitt R. Antidepressants for generalized anxiety disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD003592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Pollack MH, Zaninelli R, Goddard A, et al. Paroxetine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: results of a placebo-controlled, flexible-dosage trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(5):350–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Liebowitz MR, Stein MB, Tancer M, Carpenter D, Oakes R, Pitts CD. A randomized, double-blind, fixed-dose comparison of paroxetine and placebo in the treatment of generalized social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(1):66–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Rickels K, Zaninelli R, McCafferty J, Bellew K, Iyengar M, Sheehan D. Paroxetine treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(4):749–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Stocchi F, Nordera G, Jokinen RH, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of paroxetine for the long-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(3):250–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(3):250–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Allgulander C, Dahl AA, Austin C, et al. Efficacy of sertraline in a 12-week trial for generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(9):1642–1649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Brawman-Mintzer O, Knapp RG, Rynn M, Carter RE, Rickels K. Sertraline treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(6):874–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Varia I, Rauscher F. Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder with citalopram. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;17(3):103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Davidson JR, Bose A, Korotzer A, Zheng H. Escitalopram in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: double-blind, placebo controlled, flexible-dose study. Depress Anxiety. 2004;19(4):234–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Davidson JR, Bose A, Wang Q. Safety and efficacy of escitalopram in the long-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(11):1441–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(11):1441–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Katz IR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Alexopoulos GS, Hackett D. Venlafaxine ER as a treatment for generalized anxiety disorder in older adults: pooled analysis of five randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(1):18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Wright A, Vandenberg C. Duloxetine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Int J Gen Med. 2009;2:153–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Bystritsky A, Kerwin L, Feusner JD, Vapnik T. A pilot controlled trial of bupropion XL versus escitalopram in generalized anxiety disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2008;41(1):46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Stein MB, Pollack MH, Bystritsky A, Kelsey JE, Mangano RM. Efficacy of low and higher dose extended-release venlafaxine in generalized social anxiety disorder: a 6-month randomized controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;177(3):280–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Koponen H, Allgulander C, Erickson J, et al. Efficacy of duloxetine for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: implications for primary care physicians. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(2):100–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koponen H, Allgulander C, Erickson J, et al. Efficacy of duloxetine for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: implications for primary care physicians. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(2):100–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Bose A, Korotzer A, Gommoll C, Li D. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of escitalopram and venlafaxine XR in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(10):854–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Allgulander C, Hackett D, Salinas E. Venlafaxine extended release (ER) in the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder: twenty-four-week placebo-controlled dose-ranging study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Rynn M, Russell J, Erickson J, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a flexible-dose, progressive-titration, placebo-controlled trial. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(3):182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Feighner JP. Overview of antidepressants currently used to treat anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 22):18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Feighner JP. Overview of antidepressants currently used to treat anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 22):18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Rickels K, Rynn M. Pharmacotherapy of generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(Suppl 14):9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Montgomery SA. Tolerability of serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(7 Suppl 11):27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

27. Monti JM, Monti D. Sleep disturbance in generalized anxiety disorder and its treatment. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4(3):263–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Belleville G, Cousineau H, Levrier K, St-Pierre-Delorme ME, Marchand A. The impact of cognitive-behavior therapy for anxiety disorders on concomitant sleep disturbances: a meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(4):379–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(4):379–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Tsypes A, Aldao A, Mennin DS. Emotion dysregulation and sleep difficulties in generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(2):197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Roerig JL. Diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety disorder. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 1999;39(6):811–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health . Short- and Long-Term Use of Benzodiazepines in Patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Review of Guidelines. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

32. Wilson S, Argyropoulos S. Antidepressants and sleep: a qualitative review of the literature. Drugs. 2005;65(7):927–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. DeVane CL, Nemeroff CB. Clinical pharmacokinetics of quetiapine: an atypical antipsychotic. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40(7):509–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Figueroa C, Brecher M, Hamer-Maansson JE, Winter H. Pharmacokinetic profiles of extended release quetiapine fumarate compared with quetiapine immediate release. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(2):199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Figueroa C, Brecher M, Hamer-Maansson JE, Winter H. Pharmacokinetic profiles of extended release quetiapine fumarate compared with quetiapine immediate release. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(2):199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Bandelow B, Chouinard G, Bobes J, et al. Extended-release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR): a once-daily monotherapy effective in generalized anxiety disorder. Data from a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13(3):305–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Khan A, Joyce M, Atkinson S, Eggens I, Baldytcheva I, Eriksson H. A randomized, double-blind study of once-daily extended release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR) monotherapy in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(4):418–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Katzman MA, Brawman-Mintzer O, Reyes EB, Olausson B, Liu S, Eriksson H. Extended release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR) monotherapy as maintenance treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a long-term, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Int Clin Psychop-harmacol. 2011;26(1):11–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Int Clin Psychop-harmacol. 2011;26(1):11–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Horacek J, Bubenikova-Valesova V, Kopecek M, et al. Mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotic drugs and the neurobiology of schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2006;20(5):389–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Jensen NH, Rodriguiz RM, Caron MG, Wetsel WC, Rothman RB, Roth BL. N-desalkylquetiapine, a potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and partial 5-HT1A agonist, as a putative mediator of quetiapine’s antidepressant activity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(10):2303–2312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Bakken GV, Rudberg I, Molden E, Refsum H, Hermann M. Pharmacokinetic variability of quetiapine and the active metabolite N-desalkylquetiapine in psychiatric patients. Ther Drug Monit. 2011;33(2):222–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Goldstein JM, Nyberg S, Brecher M. Preclinical mechanisms for the broad spectrum of antipsychotic, antidepressant and mood stabilizing properties of Seroquel. European Psychiatry. 2008;23(Suppl 2):S202. [Google Scholar]

2008;23(Suppl 2):S202. [Google Scholar]

42. Maneeton N, Maneeton B, Srisurapanont M, Martin SD. Quetiapine monotherapy in acute phase for major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Merideth C, Cutler AJ, She F, Eriksson H. Efficacy and tolerability of extended release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy in the acute treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized, placebo controlled and active-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(1):40–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Srisurapanont M, Maneeton B, Maneeton N. Quetiapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD000967. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Maneeton B, Maneeton N, Srisurapanont M, Chittawatanarat K. Quetiapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of delirium: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7:657–667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Suttajit S, Srisurapanont M, Maneeton N, Maneeton B. Quetiapine for acute bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:827–838. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32(1):50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] [Google Scholar]

49. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):746–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Papakostas GI. Tolerability of modern antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(Suppl E1):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] [Google Scholar]

Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] [Google Scholar]

52. Wiebe N, Vandermeer B, Platt RW, Klassen TP, Moher D, Barrowman NJ. A systematic review identifies a lack of standardization in methods for handling missing variance data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(4):342–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D. Addressing Reporting Biases. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] [Google Scholar]

54. Endicott J, Svedsater H, Locklear JC. Effects of once-daily extended release quetiapine fumarate on patient-reported outcomes in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2012;8:301–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Montgomery SA, Locklear JC, Svedsater H, Eriksson H. Efficacy of once-daily extended release quetiapine fumarate in patients with different levels of severity of generalized anxiety disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(5):252–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Montgomery SA, Locklear JC, Svedsater H, Eriksson H. Efficacy of once-daily extended release quetiapine fumarate in patients with different levels of severity of generalized anxiety disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(5):252–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Sheehan DV, Svedsater H, Locklear JC, Eriksson H. Effects of extended-release quetiapine fumarate on long-term functioning and sleep quality in patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): data from a randomized-withdrawal, placebo-controlled maintenance study. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(3):906–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. AstraZeneca Safety & Efficacy Study of Quetiapine Fumarate (SEROQUEL®) vs Placebo in Generalized Anxiety Disorder (TITANIUM) [Accessed October 18, 2015]. Available fom: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/{"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT00329264","term_id":"NCT00329264"}}NCT00329264. NLM identifier: NCT00329264.

58. AstraZeneca Efficacy and Safety Study of Seroquel SR in the Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (SILVER) [Accessed October 18, 2015]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/{"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT00322595","term_id":"NCT00322595"}}NCT00322595. NLM identifier: NCT00322595.

Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/{"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT00322595","term_id":"NCT00322595"}}NCT00322595. NLM identifier: NCT00322595.

59. AstraZeneca Safety & Efficacy Study of Quetiapine Fumarate (SEROQUEL®) vs Placebo & Active Control in Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GOLD) [Accessed October 18, 2015]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/{"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT00329446","term_id":"NCT00329446"}}NCT00329446. NLM identifier: NCT00329446.

60. Merideth C, Cutler A, Neijber A, She F, Eriksson H. Extended release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder (gad): a randomized, placebo and escitalopram-controlled study. World Psychiatry. 2009;8(Suppl 1):215. meeting: April 1–4, 2009; Florence, Italy. [Google Scholar]

61. Brawman-Mintzer O, Nietert PJ, Rynn M, Rickels K. Quetiapine monotherapy in patients with generalized anxiety disorder; Paper presented at: 46th Annual NCDEU (New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit) meeting; June 12–15, 2006; Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

62. Sheehan DV, Svedsater H, Locklear J, Eriksson H. Effects of extended release quetiapine fumarate on long-term functioning and sleep quality in patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) [conference abstract]; Paper presented at: 163rd Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 22–26, 2010; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

63. Wu WY, Wang G, Ball SG, Desaiah D, Ang QQ. Duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of patients with generalized anxiety disorder in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011;124(20):3260–3268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Goodman WK, Bose A, Wang Q. Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder with escitalopram: pooled results from double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2–3):161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Papadimitriou GN, Linkowski P. Sleep disturbance in anxiety disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005;17(4):229–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Stein DJ, Lopez AG. Effects of escitalopram on sleep problems in patients with major depression or generalized anxiety disorder. Adv Ther. 2011;28(11):1021–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Adv Ther. 2011;28(11):1021–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Dolder CR, Nelson MH, Iler CA. The effects of mirtazapine on sleep in patients with major depressive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24(3):215–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Lenze EJ, Rollman BL, Shear MK, et al. Escitalopram for older adults with generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(3):295–303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seroquel in the treatment of psychotic and behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer's disease - Psychiatry and Psychopharmacotherapy. P.B. Gannushkina Annex No. 2

Subscribe to new numbers

Author: IV Kolykhalov, Ya.

The need for drug treatment of psychotic and behavioral symptoms of dementia is determined by their severity, the presence of anxiety or aggression, as well as the security threat associated with these violations for the patient or his immediate environment. Most cases of aggression, psychomotor agitation, as well as the actual psychotic symptoms of dementia, require the appointment of psychopharmacological agents. Until now, various groups of psychotropic drugs have been used to treat psychotic and behavioral disorders in patients with dementia: antipsychotics, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants. nine0003

Most cases of aggression, psychomotor agitation, as well as the actual psychotic symptoms of dementia, require the appointment of psychopharmacological agents. Until now, various groups of psychotropic drugs have been used to treat psychotic and behavioral disorders in patients with dementia: antipsychotics, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants. nine0003

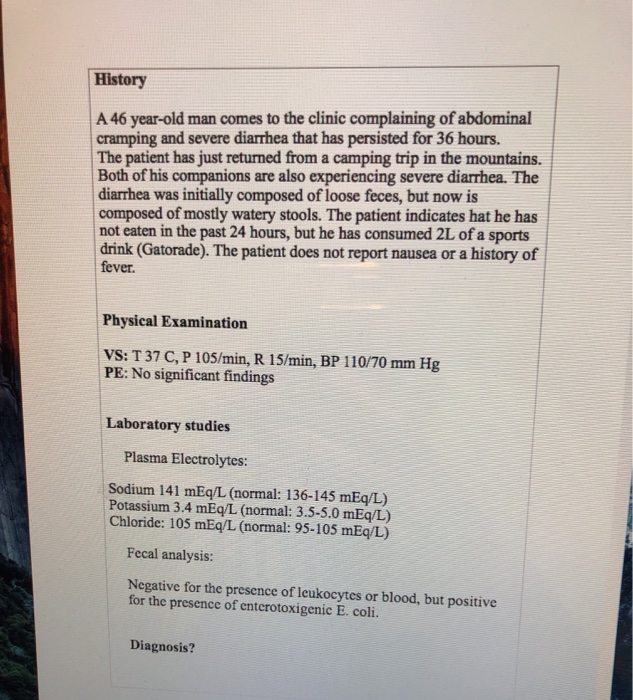

Behavioral and psychopathological disorders that accompany the development of dementia at different stages of its formation occur in more than 80% of patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) (R.Sweet B.Pollock, 1998). Approximately half of the patients observed in the outpatient departments of specialized clinics, and three-quarters of patients in nursing homes, have various psychotic and behavioral disorders (P.Tariot, L.Blazina, 1994; S.Finkel, 1998).

Depending on the nature of behavioral and psychopathological disorders in dementia, the following groups of disorders are distinguished: psychotic (delusional, hallucinatory and hallucinatory-delusional) and depressive (depressed mood, apathy, lack of motivation) symptoms, as well as behavioral disorders proper (aggression, wandering, motor restlessness). , violent screaming, inappropriate sexual behavior, etc.). nine0012 The need for drug treatment of psychotic and behavioral symptoms of dementia is determined by their severity, the presence of anxiety or aggression, as well as the security threat associated with these violations for the patient or his immediate environment. Most cases of aggression, psychomotor agitation, as well as the actual psychotic symptoms of dementia, require the appointment of psychopharmacological agents.

, violent screaming, inappropriate sexual behavior, etc.). nine0012 The need for drug treatment of psychotic and behavioral symptoms of dementia is determined by their severity, the presence of anxiety or aggression, as well as the security threat associated with these violations for the patient or his immediate environment. Most cases of aggression, psychomotor agitation, as well as the actual psychotic symptoms of dementia, require the appointment of psychopharmacological agents.

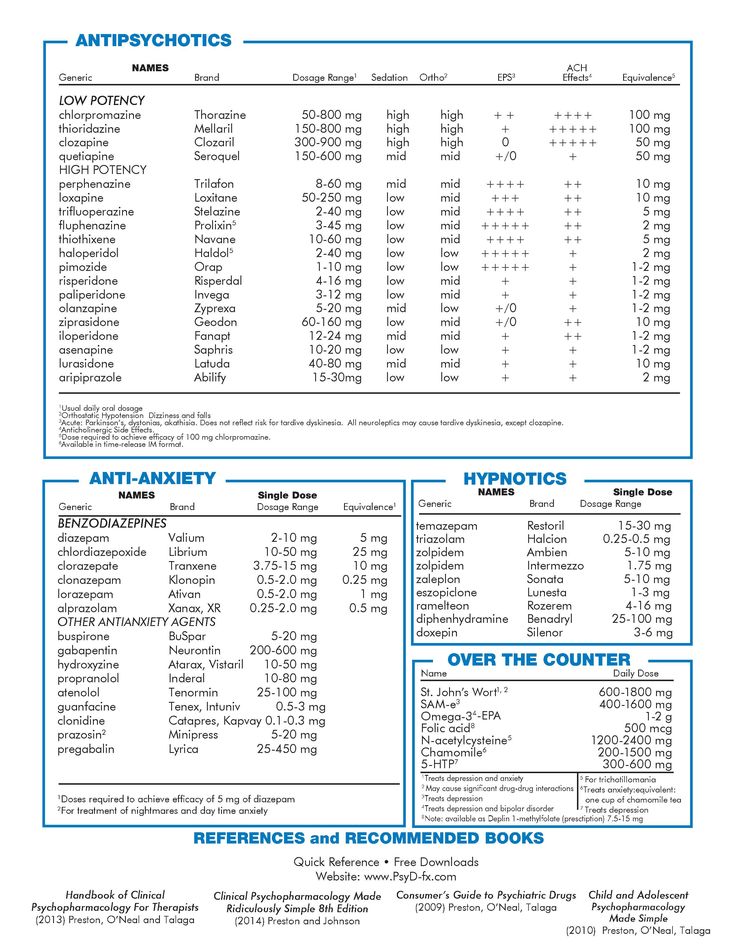

Until now, various groups of psychotropic drugs have been used to treat psychotic and behavioral disorders in patients with dementia: antipsychotics, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants. nine0012 Undesirable effects are inherent in all of the listed groups of drugs. Thus, the use of antidepressants (especially tricyclics) in elderly patients with dementia is associated with the risk of hypotension and serious anticholinergic effects. Anxiolytics (especially benzodiazepines) can cause excessive sedation and cognitive depression, or, conversely, increase aggression and anxiety. But the greatest risk of adverse effects on elderly patients with dementia is associated with the use of antipsychotics. According to W.Petrie et al. (nineteen82), the use of antipsychotics was accompanied by adverse events in 90% of these patients. R. Barnes et al. (1982), who studied the effectiveness of treatment with loxapine and thioridazine (sonapax) in comparison with placebo for behavioral disorders in 56 patients with asthma and dementia of a different etiology, noted side effects in 45% of patients treated with loxapine and in 33% of those receiving thioridazine.

But the greatest risk of adverse effects on elderly patients with dementia is associated with the use of antipsychotics. According to W.Petrie et al. (nineteen82), the use of antipsychotics was accompanied by adverse events in 90% of these patients. R. Barnes et al. (1982), who studied the effectiveness of treatment with loxapine and thioridazine (sonapax) in comparison with placebo for behavioral disorders in 56 patients with asthma and dementia of a different etiology, noted side effects in 45% of patients treated with loxapine and in 33% of those receiving thioridazine.

The search for psychotropic drugs with minimal anticholinergic effects seems to be a particularly urgent task in relation to the treatment of behavioral and psychotic disorders in patients with AD. nine0012 The emergence of a new generation of atypical antipsychotics is making a significant contribution to the improvement of modern antipsychotic therapy for dementia. Atypical neuroleptics have a significant advantage over traditional antipsychotics because they affect a wider range of psychopathological disorders, including affective disorders, agitation, hostility, and the actual psychotic symptoms that develop in various forms of dementia. It is especially important that in therapeutic doses they practically do not cause extrapyramidal and neuroendocrine side effects. nine0012 Seroquel (quetiapine) is the latest atypical antipsychotic drug introduced into practice. Seroquel is a dibenzothiazepine derivative with a wide range of affinity for various central nervous system receptor subtypes. Seroquel has the highest affinity for 5-HT 2 - serotonergic receptors with relatively low interaction with dopamine D 1 - and D 2 - receptors (J.Goldstein, 1996). Along with this, compared with classical antipsychotics, seroquel exhibits low tropism for muscarinic and a 1 -adrenergic receptors (C.Sailer, A.Salama, 1993). Seroquel shows selectivity for mesolimbic and mesocortical dopamine receptors, which are considered responsible for the development of the actual antipsychotic effect. Unlike most classic and some atypical neuroleptics, seroquel has minimal effect on the nigrostrial dopamine system, which is associated with the development of neurological extrapyramidal side symptoms.

It is especially important that in therapeutic doses they practically do not cause extrapyramidal and neuroendocrine side effects. nine0012 Seroquel (quetiapine) is the latest atypical antipsychotic drug introduced into practice. Seroquel is a dibenzothiazepine derivative with a wide range of affinity for various central nervous system receptor subtypes. Seroquel has the highest affinity for 5-HT 2 - serotonergic receptors with relatively low interaction with dopamine D 1 - and D 2 - receptors (J.Goldstein, 1996). Along with this, compared with classical antipsychotics, seroquel exhibits low tropism for muscarinic and a 1 -adrenergic receptors (C.Sailer, A.Salama, 1993). Seroquel shows selectivity for mesolimbic and mesocortical dopamine receptors, which are considered responsible for the development of the actual antipsychotic effect. Unlike most classic and some atypical neuroleptics, seroquel has minimal effect on the nigrostrial dopamine system, which is associated with the development of neurological extrapyramidal side symptoms. All of these properties make Seroquel an effective antipsychotic with a favorable side effect profile. nine0012 The possibility of using Seroquel in geriatric psychiatry was studied in a large multicenter open study. Seroquel was used in elderly patients (n=151) with various psychotic disorders. The study lasted 12 weeks. The average daily dose of the drug was 100 mg/day. According to D.McManus et al. (1999), the most common side effects during the study period were drowsiness (in 32% of patients), dizziness (in 14%), orthostatic hypotension (in 13%) and agitation (in 11%). A significant improvement in the condition of patients on the BPRS and CGI scales by the end of the study was established. Separately, the results of a study in a subgroup of patients (n=40) with Parkinson's disease were analyzed (J. Juncos et al., 1998). The results of this analysis showed that seroquel significantly reduced the severity of psychotic symptoms and did not cause worsening of the motor symptoms of parkinsonism.

All of these properties make Seroquel an effective antipsychotic with a favorable side effect profile. nine0012 The possibility of using Seroquel in geriatric psychiatry was studied in a large multicenter open study. Seroquel was used in elderly patients (n=151) with various psychotic disorders. The study lasted 12 weeks. The average daily dose of the drug was 100 mg/day. According to D.McManus et al. (1999), the most common side effects during the study period were drowsiness (in 32% of patients), dizziness (in 14%), orthostatic hypotension (in 13%) and agitation (in 11%). A significant improvement in the condition of patients on the BPRS and CGI scales by the end of the study was established. Separately, the results of a study in a subgroup of patients (n=40) with Parkinson's disease were analyzed (J. Juncos et al., 1998). The results of this analysis showed that seroquel significantly reduced the severity of psychotic symptoms and did not cause worsening of the motor symptoms of parkinsonism. Moreover, during the period of treatment with seroquel, the severity of the latter gradually decreased. An analysis of the effectiveness of Seroquel in patients with Alzheimer's disease who exhibit symptoms of hostility (n=78) (L. Schneider et al., 1999) showed that the drug significantly significantly reduced hostile behavior.

Moreover, during the period of treatment with seroquel, the severity of the latter gradually decreased. An analysis of the effectiveness of Seroquel in patients with Alzheimer's disease who exhibit symptoms of hostility (n=78) (L. Schneider et al., 1999) showed that the drug significantly significantly reduced hostile behavior.

The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy and safety of seroquel in the treatment of psychotic and behavioral disorders in patients with asthma. The study was conducted at the Scientific and Methodological Center for the Study of Alzheimer's Disease and Associated Disorders of the National Center for Health Care of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences. nine0012 The clinical study was performed as a simple open study on a non-selective group of patients (n=31, 5 men and 26 women) aged 49 to 84 years with various clinical forms of asthma. The mean age of the patients was 68.5±8.2 years. The duration of the disease ranged from 2 to 20 years and averaged 5. 5±3.8 years. Five patients were treated in stationary conditions, 26 - on an outpatient basis.

5±3.8 years. Five patients were treated in stationary conditions, 26 - on an outpatient basis.

The distribution of patients by clinical forms of asthma in accordance with the ICD-10 diagnostic headings is presented in tab. 1.

The condition of 7 patients corresponded to the stage of mild dementia, 16 - moderate and 8 patients - severe dementia (according to the criteria of the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale).

The clinical study was carried out according to a specially developed protocol using unified individual patient records. Patients' condition was assessed before the start of treatment and during the course of therapy (on days 28 and 56) using the Global Clinical Impression (CGI) scale, MMSE, ADAS-cog. -AD). nine0003

The majority of patients (38.7%) were included in the study due to the lack of effect from previous treatment with antipsychotic drugs. In 25.8%, the reason for switching to Seroquel was the presence of side effects from previous therapy, and 35. 5% were prescribed antipsychotic therapy for the first time.

5% were prescribed antipsychotic therapy for the first time.

The drug was prescribed at a dose of 50 mg/day (25 mg 2 times a day). Over the next 7 days, the dose was increased to 100 mg / day (50 mg 2 times a day). A further increase in the dose of Seroquel was carried out individually by no more than 50 mg/day (maximum dose 300 mg/day). The duration of course therapy was 8 weeks. nine0012 Prior to the start of therapy, the majority (67.7%) of patients had psychotic and behavioral symptoms so severe that they presented significant difficulties for their caregivers and/or were dangerous for the patient himself. In 10 patients (32.3%), behavioral disorders and psychotic disorders created some difficulties for those caring for them and/or could be dangerous for the patient himself, therefore, they were rated as moderate.

By the end of therapy, the severity of psychotic and behavioral disorders was assessed as follows: moderately severe disorders - in 9(29.0%) patients, slightly pronounced - in 17 (54. 8%) patients. In 5 patients (16.2%), the mentioned symptoms were completely reduced.

8%) patients. In 5 patients (16.2%), the mentioned symptoms were completely reduced.

Evaluation of the effectiveness of therapy on the CGI scale ( Fig. 1 ) showed that in the examined patients, a significant and very significant positive effect of seroquel therapy was observed in 51.5% of cases already by the 28th day of therapy, and by the time the course was completed - in 64 .5% of patients. Only 1 patient showed no positive dynamics during treatment with seroquel. nine0003

During therapy with Seroquel, a significant improvement in psychotic and behavioral symptoms on the BEHAVE-AD scale was found, starting from the 28th day of therapy ( fig. 2 , tab. 2 ).

At the end of therapy, a decrease in the severity of behavioral and psychotic symptoms by 73.5% was noted.

Analysis of the severity of individual groups of symptoms presented in the BEHAVE-AD scale showed that by the end of therapy, significant positive dynamics was noted across the entire spectrum of psychotic and behavioral symptoms. According to the sub-items of the scale "hallucinatory disorders", "impaired activity", "aggressiveness", the reduction of symptoms was more than 70% ( fig. 3 ).

According to the sub-items of the scale "hallucinatory disorders", "impaired activity", "aggressiveness", the reduction of symptoms was more than 70% ( fig. 3 ).

It should be emphasized that in the course of treatment with seroquel, patients did not show any negative dynamics of cognitive indicators. On the contrary, by the end of therapy, there was a significant improvement in cognitive functions both on the MMSE scale and on the ADAS-cog scale. ( fig. 4 ).

Adverse events were observed in 5 (16.1%) of 31 patients treated, but no severe side effects were noted in any case. nine0012 4 patients (12.9%) had complaints of muscle weakness, which stopped after a dose reduction. In 2 patients, increased daytime sleepiness was noted. One patient was diagnosed with orthostatic hypotension.

The study showed that seroquel is an effective and safe agent in the treatment of behavioral and psychotic disorders in AD. During therapy with Seroquel, no significant adverse events were noted. Of particular note is the absence of extrapyramidal side symptoms, which are not uncommon in neuroleptic therapy of patients with dementia. In the process of treatment with Seroquel in patients with asthma, both psychotic and behavioral pathology are equally successfully reduced. The severity of psychopathological symptoms significantly decreased with the use of relatively small (50–300 mg/day) doses of Seroquel (average 100 mg/day). The highest doses of Seroquel had to be used to relieve delusional and hallucinatory disorders (100–300 mg/day) and relatively smaller doses to reduce the symptoms of aggression (50–200 mg/day) and treat depressive and anxiety-phobic disorders (50–200 mg/day). ). nine0012 Seroquel therapy in patients with AD not only does not increase cognitive impairment, as occurs with the use of typical antipsychotics, but as psychotic and behavioral symptoms decrease, even a significant improvement in the cognitive functioning of patients is observed.

Of particular note is the absence of extrapyramidal side symptoms, which are not uncommon in neuroleptic therapy of patients with dementia. In the process of treatment with Seroquel in patients with asthma, both psychotic and behavioral pathology are equally successfully reduced. The severity of psychopathological symptoms significantly decreased with the use of relatively small (50–300 mg/day) doses of Seroquel (average 100 mg/day). The highest doses of Seroquel had to be used to relieve delusional and hallucinatory disorders (100–300 mg/day) and relatively smaller doses to reduce the symptoms of aggression (50–200 mg/day) and treat depressive and anxiety-phobic disorders (50–200 mg/day). ). nine0012 Seroquel therapy in patients with AD not only does not increase cognitive impairment, as occurs with the use of typical antipsychotics, but as psychotic and behavioral symptoms decrease, even a significant improvement in the cognitive functioning of patients is observed.

Thus, seroquel can be recommended to patients with AD as an effective and safe drug for the treatment of psychotic and non-psychotic psychopathological disorders, as well as behavioral disorders associated with dementia. nine0012

nine0012

List of used literature Hide list

1. Burns A, Jacoby R, Levy R. Br J Psychiat 1990; 157:72–94.

2. Finkel S.I. Clinician 1998; 16:33–42.

3. Goldstein J. Safety and tolerability of switching from conventional antipsychotic therapy to quetiapine fumarate followed by abrupt withdrawal from quetiapine fumarate (poster). Presented at the 38th Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit Program, Boca Raton, FL, June 10–13, 1998.

4 Juncos J, Yeung P, Sweitzer D et al. Quetiapine improves psychotic symptoms associated with Parkinson's disease (poster). Presented at the 37th Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; Las Croabas, P. R.; December 14–18, 1998.

5. McManus DQ, Arvanitis LA, Kowalcyk BB et al. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:292–8.

6. Petrie WM, Ban TA, Berney S et al. J Clin Psychophamacol 1982; 2:122–6.

7 Sailer CF, Salama AL. Psychopharmacology 1993; 112:285–92.

8. Schneider L, Yeung P, Sweitzer D, Arvanitis LA. "SEROQUEL" (quetiapine fumarate) reduces aggression and hostility in patients with psychoses related to Alzheimer's disease (poster). Presented at the 152th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC, May 15–20th, 1999.

9. Sweet RA, Pollock BG. Drugs & Aging 1998; 12(2): 115–27.

10. Tariot PN, Blazina L. The psychopathology of dementia. In: Morris JC, editor. Handbook of dementing illnesses. N.Y.: Marcel Dekker lnc, 1994; 461–75.

November 15, 2003

Views: 9401

Use of atypical antipsychotics for anxiety in a borderline psychiatry clinic | Chakhava V.O., Less Yu.E., Avedisova A.S. nine0001

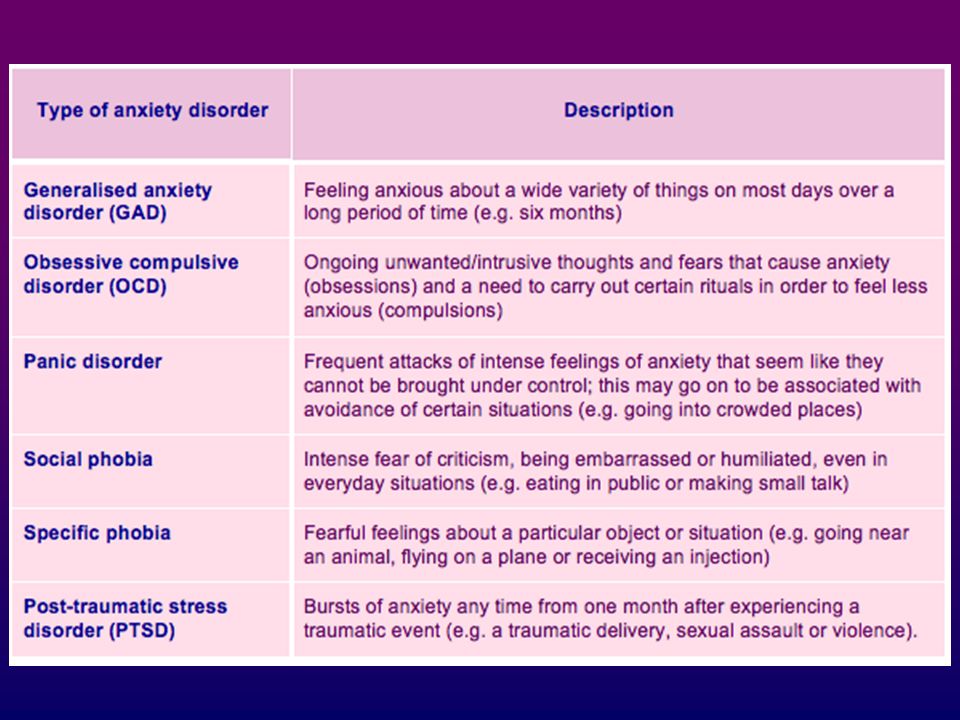

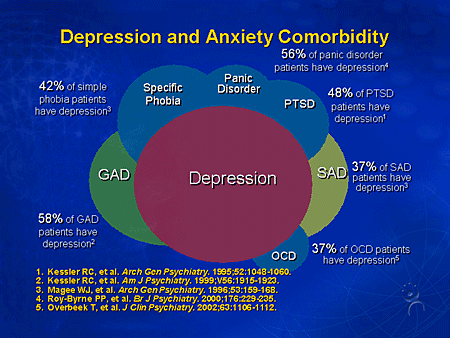

Anxiety, fear, restlessness are perhaps the most common symptoms from the circle of so-called borderline mental disorders (BPD), entering the structure of not only anxiety proper, but also largely complementing the picture of depression and somatoform disorders. Despite the relatively shallow level of damage to the psyche, these disorders are often prone to a long course. Thus, according to some authors [10], during the 12-year follow-up period, 50% of patients with panic disorder (PD) recovered, 60% with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), 72% with major depressive disorder (MDD) and only 40% with social phobia (SF). There is also a high tendency of these disorders to recurrence: over the same period, 75% of patients with MDD, 60% of patients with AF, 55% with PR, 45% with GAD relapses were recorded. nine0003

Despite the relatively shallow level of damage to the psyche, these disorders are often prone to a long course. Thus, according to some authors [10], during the 12-year follow-up period, 50% of patients with panic disorder (PD) recovered, 60% with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), 72% with major depressive disorder (MDD) and only 40% with social phobia (SF). There is also a high tendency of these disorders to recurrence: over the same period, 75% of patients with MDD, 60% of patients with AF, 55% with PR, 45% with GAD relapses were recorded. nine0003

Insufficient knowledge of the mechanisms of anxiety-phobic disorders (TFR) predetermines mainly an empirical approach to the choice of a particular drug for the treatment of these conditions. It is not surprising that drugs with completely different mechanisms of action are used: most often tranquilizers and antidepressants.

Traditionally, tranquilizers are most often used, primarily benzodiazepine derivatives (BDZ). Sufficiently high efficiency, usually good tolerability, ease of use are well known to clinicians. The benzodiazepine drugs are effective both in relation to the ideational component of anxiety and in the case of the predominance of somatic manifestations [18]. Many researchers consider BDZ the most effective medication for generalized anxiety [2,4,18]. Nutt D. [19] even speaks of BDD as the "gold standard" in the treatment of GAD. At the same time, only alprozolam and clonazepam are proven to be effective in PR, while drugs in this group are ineffective in OCD.

The benzodiazepine drugs are effective both in relation to the ideational component of anxiety and in the case of the predominance of somatic manifestations [18]. Many researchers consider BDZ the most effective medication for generalized anxiety [2,4,18]. Nutt D. [19] even speaks of BDD as the "gold standard" in the treatment of GAD. At the same time, only alprozolam and clonazepam are proven to be effective in PR, while drugs in this group are ineffective in OCD.

However, the use of BDZ is associated with phenomena of the so-called behavioral toxicity, associated primarily with mnestic-sedative adverse events. Deterioration of psychophysiological indicators, often not subjectively noted, increases the risk of road accidents, industrial and domestic injuries. Along with these typical side effects for taking BDZ, some patients also experience paradoxical effects: psychomotor agitation, angry affect, aggressiveness, and behavioral disinhibition. nine0012 The most significant factor limiting the use of BDZ in clinical practice is their addictive potential [20]. Due to the risk of drug dependence, tranquilizers are usually recommended for short courses. However, this point of view is not shared by some reputable researchers who consider long-term therapy with BDZ to be acceptable, and the risk of drug dependence is relatively low [1,2,4,5,7,18].

Due to the risk of drug dependence, tranquilizers are usually recommended for short courses. However, this point of view is not shared by some reputable researchers who consider long-term therapy with BDZ to be acceptable, and the risk of drug dependence is relatively low [1,2,4,5,7,18].

Nevertheless, in most modern guidelines on psychiatry, it is recommended to prescribe BDZ mainly for acute stress reactions, sleep disorders of a psychogenic nature. Although GAD, SF are also indications for prescribing, in practice there is a contradiction between the need for long-term therapy and restrictions on the timing of taking BDZ. nine0012 The disadvantages of BDZ led to the search for alternative tranquilizers, and the creation of new drugs in this group has practically ceased (for 20 years, not a single new representative of this group of drugs has been registered in our country). Studies by Eison (1989) [13], Feighner et al. (1989) [15] showed that the so-called selective serotonin anxiolytics (selective 5-HT1A receptor agonists - buspirone, gepirone and ipsapirone) can also cause a positive effect in the treatment of anxiety. For this purpose, the drug buspirone has been studied in the most detail. Although controlled studies have established approximately equal efficacy of buspirone and BDS in GAD, the experience of clinical use of buspirone has not fully justified the hopes placed on this drug due to inefficiency in a significant proportion of patients [11,12]. In addition, compared with BDZ, the effect of buspirone turned out to be excessively delayed, developing only after a month of therapy and longer. At the same time, it was found that, compared with BDZ, side effects during therapy with buspirone are much less pronounced. nine0012 From tranquilizers of a different chemical structure, antihistamines with anxiolytic action (H1 blockers) are also discussed in the special literature. Thus, in the treatment with hydroxyzine, the therapeutic effect is observed in 60–85% of patients with GAD [9]. The features of hydroxyzine include a rapid onset of action, comparable to that of benzodiazepines, an increase in sleep duration and REM phase, a decrease in stress and associated anxiety [19].

For this purpose, the drug buspirone has been studied in the most detail. Although controlled studies have established approximately equal efficacy of buspirone and BDS in GAD, the experience of clinical use of buspirone has not fully justified the hopes placed on this drug due to inefficiency in a significant proportion of patients [11,12]. In addition, compared with BDZ, the effect of buspirone turned out to be excessively delayed, developing only after a month of therapy and longer. At the same time, it was found that, compared with BDZ, side effects during therapy with buspirone are much less pronounced. nine0012 From tranquilizers of a different chemical structure, antihistamines with anxiolytic action (H1 blockers) are also discussed in the special literature. Thus, in the treatment with hydroxyzine, the therapeutic effect is observed in 60–85% of patients with GAD [9]. The features of hydroxyzine include a rapid onset of action, comparable to that of benzodiazepines, an increase in sleep duration and REM phase, a decrease in stress and associated anxiety [19]. Limitations on the use of hydroxyzine are mainly due to its relatively low anxiolytic potential. nine0012 In recent years, antidepressants (ADs) have become more and more popular. The variety of their clinical effects, including thymoanaleptic, anxiolytic, antiphobic, sedative, psychostimulant, vegetostabilizing and anticholinergic effects [3] determine a wide range of applications of these drugs in mental disorders. It has been proven that new drugs from the groups of SSRIs, SNRIs, SNRIs * are highly effective not only in various depressions, but also in PR, agoraphobia (AF), GAD, SF, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Unlike BDZ, specialists have no doubt that AD (especially serotonergic ones), if effective, can be used for long-term maintenance therapy [Gorham J.M., 1987].

Limitations on the use of hydroxyzine are mainly due to its relatively low anxiolytic potential. nine0012 In recent years, antidepressants (ADs) have become more and more popular. The variety of their clinical effects, including thymoanaleptic, anxiolytic, antiphobic, sedative, psychostimulant, vegetostabilizing and anticholinergic effects [3] determine a wide range of applications of these drugs in mental disorders. It has been proven that new drugs from the groups of SSRIs, SNRIs, SNRIs * are highly effective not only in various depressions, but also in PR, agoraphobia (AF), GAD, SF, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Unlike BDZ, specialists have no doubt that AD (especially serotonergic ones), if effective, can be used for long-term maintenance therapy [Gorham J.M., 1987].

Most researchers agree that in case of anxiety, AD affect mainly ideational manifestations, while BDZ by its action covers both ideational and somatic anxiety. One of the significant disadvantages of AD therapy is the delayed effect, as a result of which the onset of therapeutic action has to wait 2-3 weeks.

Although indications for AD include a wide range of non-psychotic disorders, their effectiveness in different conditions may vary. Thus, according to some researchers [4], with a typical GAD, the use of AD cannot play a leading role and the possibilities of their use are limited. On the contrary, in mixed anxiety-depressive states, for which a special rubric is assigned in the ICD-10, their therapeutic value increases significantly. According to the author, the more closely fused anxiety and melancholic affects, the greater the specific gravity of the circadian-vital radical, the better the effect can be expected from the use of imipramine and other tricyclic AD [4]. nine0012 The possibility of using neuroleptics (antipsychotics) in PPR is discussed in the special literature. On the one hand, it can be stated that, in practice, neuroleptics are often prescribed for neurotic disorders, for example, for TFR. This is evidenced by the data of a pharmacoeconomic study conducted by Bandelow B. et al. (1995) [8], which showed that neuroleptics are prescribed to patients with PD and agoraphobia in 23% of cases. As an example, flupenthixol is used to treat GAD in the UK, and sulpiride is widely used in most European countries. On the other hand, the opinion about the inexpediency of using antipsychotics in TFR due to their high behavioral toxicity has become widespread [22]. In a number of modern guidelines, drugs of this group are not mentioned among the means of treating PPR. nine0012 Studies on the use of antipsychotics (flupentixol, chlorprothixene, sulpiride, levomepromazine, trifluoperazine) in PPR are few. There are separate data on the use of small doses of this group of drugs for GAD resistant to other drugs; while emphasizing the risk of developing extrapyramidal and endocrine disorders associated with their long-term use [14,23].

et al. (1995) [8], which showed that neuroleptics are prescribed to patients with PD and agoraphobia in 23% of cases. As an example, flupenthixol is used to treat GAD in the UK, and sulpiride is widely used in most European countries. On the other hand, the opinion about the inexpediency of using antipsychotics in TFR due to their high behavioral toxicity has become widespread [22]. In a number of modern guidelines, drugs of this group are not mentioned among the means of treating PPR. nine0012 Studies on the use of antipsychotics (flupentixol, chlorprothixene, sulpiride, levomepromazine, trifluoperazine) in PPR are few. There are separate data on the use of small doses of this group of drugs for GAD resistant to other drugs; while emphasizing the risk of developing extrapyramidal and endocrine disorders associated with their long-term use [14,23].

Some authors consider it expedient to use high-potential dopamine blockers: haloperidol, risperidone in OCD resistant to SSRI therapy [16,21]. At the same time, some authors say that such antipsychotics as clozapine and olanzapine worsen the course of OCD [17]. However, Weiss et al. (nineteen99) [23] found that olanzapine is effective in SSRI-resistant OCD as adjunctive therapy in an open study.

At the same time, some authors say that such antipsychotics as clozapine and olanzapine worsen the course of OCD [17]. However, Weiss et al. (nineteen99) [23] found that olanzapine is effective in SSRI-resistant OCD as adjunctive therapy in an open study.

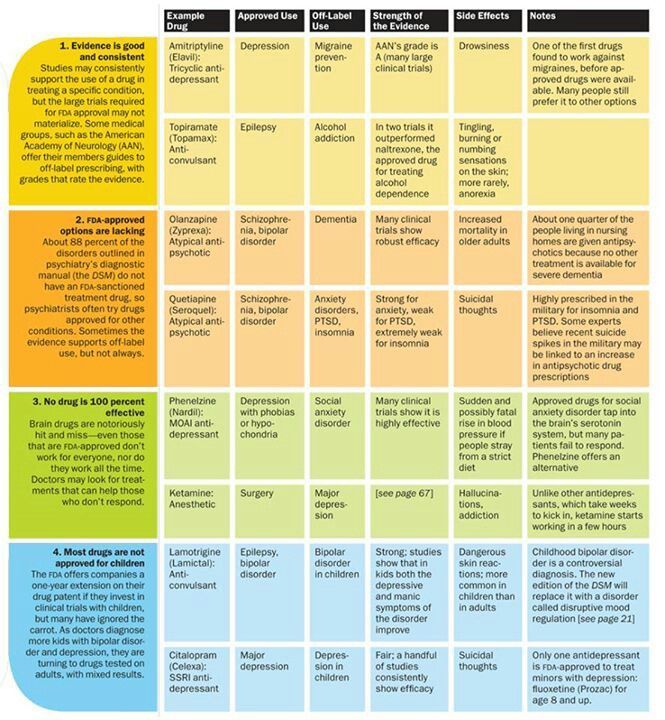

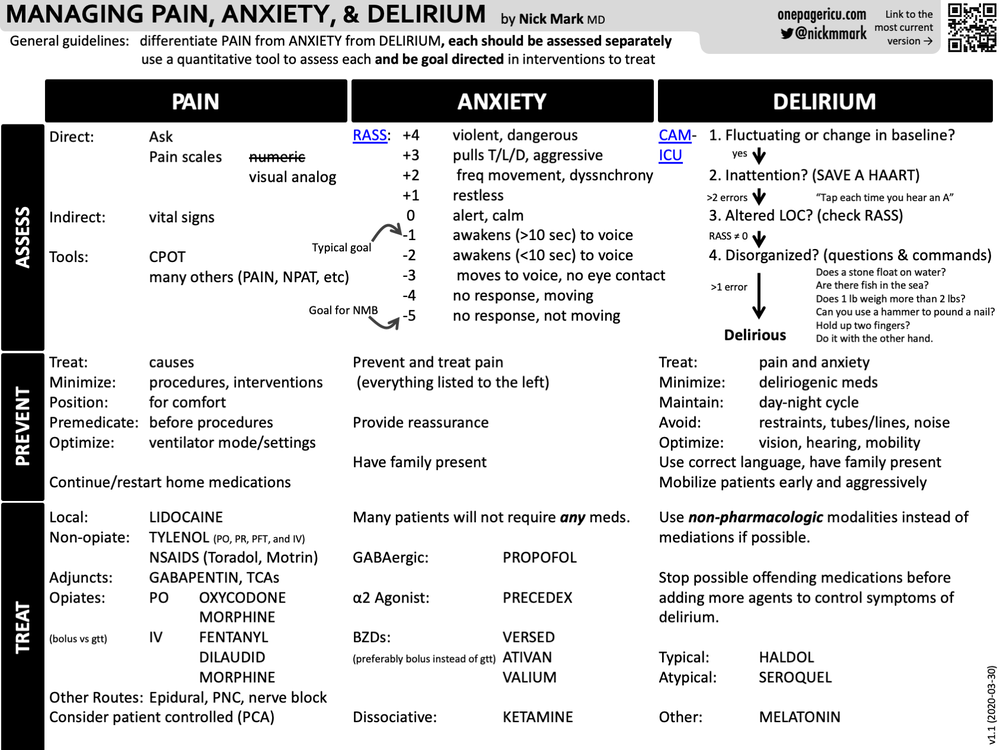

Quetiapine occupies a special place among the 2nd generation antipsychotics due to a peculiar mechanism of receptor interaction: high affinity for h2 and 5-HT2 receptors and moderate affinity for D2 receptors. The literature discusses a certain similarity of quetiapine with AD - serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which has already found its use in the treatment of anxiety and depression in bipolar disorder. There is reason to believe that quetiapine may be a promising drug for the treatment of conditions in the circle of "minor" psychiatry, covering superficial affective, anxiety-phobic and somatic disorders. This is favored, on the one hand, by the tranquilizing properties present in the spectrum of therapeutic activity of quetiapine, and, on the other hand, by a favorable profile of side effects with a minimal undesirable somatotropic effect. The last circumstance seems to be no less important, since patients with non-psychotic disorders in most cases are hypersensitive to adverse effects of psychotropic drugs. nine0012 Type of research: open naturalistic.

The last circumstance seems to be no less important, since patients with non-psychotic disorders in most cases are hypersensitive to adverse effects of psychotropic drugs. nine0012 Type of research: open naturalistic.

The aim of the study was to optimize the treatment of non-psychotic disorders with quetiapine.

The work was carried out in the Department of Borderline Psychiatry, State Scientific Center for Social and Forensic Psychiatry. Serbsky on the basis of the clinical department of PKB-12 in Moscow.

Inclusion Criteria:

1. Diagnosis from the heading "neurotic disorders" or "affective disorders" ICD-10.

2. Patients who had completed at least 1 course of adequate pharmacotherapy and were non-responders to this therapy were included. nine0012 3. Rating points on the Hamilton Anxiety Scale - at least 20 at the time of inclusion in the study.

4. Men and women aged 18-60.

5. Informed consent to participate in the study.

Exclusion Criteria:

1. Schizophrenia, organic disease of the central nervous system, drug addiction, alcoholism.

Schizophrenia, organic disease of the central nervous system, drug addiction, alcoholism.

2. Pregnancy or lactation.

3. Clinically expressed somatic diseases or deviations of laboratory parameters.

The condition of the patients was assessed weekly using the General Clinical Impression Scale (CVI), which includes 2 subscales (severity of the condition and general improvement). nine0012 In the studied sample, as a whole, women predominated somewhat, the average age of patients at the time of the study was 37.6 years. The sample consisted of hospitalized and outpatients, whose condition at the time of inclusion in the study corresponded to the following diagnoses (according to ICD-10): AF (9 cases), GAD (15 cases), Depr. (9 cases), SR (11 cases), OCD (11 cases). The distribution of patients according to sex and age is presented in Table 1.

It should be noted that the condition of the patients was not limited to the characteristics of one disorder, the diagnosis, in fact, reflected only the leading symptom complex. Along with the latter, comorbid psychopathological symptoms were revealed. The severity of comorbid disorders did not allow considering them as complete psychopathological formations (syndromes), however, to a certain extent, it complicated the clinical picture, which gave reason to take them into account when characterizing the material. The distribution of patients according to comorbid disorders is shown in Table 2.

Along with the latter, comorbid psychopathological symptoms were revealed. The severity of comorbid disorders did not allow considering them as complete psychopathological formations (syndromes), however, to a certain extent, it complicated the clinical picture, which gave reason to take them into account when characterizing the material. The distribution of patients according to comorbid disorders is shown in Table 2.

As can be seen from Table 2, the most common comorbid symptomatology was anxiety observed in AF and SR in 100%, in depression in 77.8%, and in OCD in 81.8% of patients. This is not about the anxiety of anticipation associated with the avoidance of a phobic situation, for example, in AF, which is an integral part of this disorder. Such manifestations of anxiety as vague anxiety, the inability to relax, and a feeling of constant tension were considered as comorbid, phenomenologically similar to generalized anxiety. Somatized comorbid symptoms included intermittent senestalgia, conversion symptoms, and autonomic dysfunction. Depressive symptoms were recorded in the presence, along with a decrease in mood and impulses, episodically manifested anhedonia. Comorbid obsessional symptoms were manifested by separate unstable contrast phobias, intrusive memories and doubts. nine0012 The distribution of previous therapy options is shown in Table 3. Of the tranquilizers, alprozolam (0.75-3 mg) was used - 4 cases, diazepam (10-20 mg) - 5 cases, clonazepam (1-3 mg) - 3 cases, phenazepam (1–3 mg) – 10 obs. From AD, venlafaxine (75–225 mg) – 7 cases, duloxetine (60 mg) – 3 cases, mirtazapine (30 mg) – 8 cases, paroxetine (20–60 mg) – 8 cases, citalopram (10 cases) -20 mg) - 11 obs., escitalopram (10-20 mg) - 12 obs. Typical antipsychotics were represented by the following drugs: haloperidol (1–10 mg) – 3 cases, thioridazine (20–40 mg) – 2 cases, trifluoperazine (5–10 mg) – 2 cases, sulpiride (100–400 mg) – 4 obs. Of the atypical neuroleptics, amisulpride (50-300 mg) - 2 cases, clozapine (25-100 mg) - 3 cases, olanzapine (5-10 mg) - 2 cases, risperidone (1 mg) - 1 case.

Depressive symptoms were recorded in the presence, along with a decrease in mood and impulses, episodically manifested anhedonia. Comorbid obsessional symptoms were manifested by separate unstable contrast phobias, intrusive memories and doubts. nine0012 The distribution of previous therapy options is shown in Table 3. Of the tranquilizers, alprozolam (0.75-3 mg) was used - 4 cases, diazepam (10-20 mg) - 5 cases, clonazepam (1-3 mg) - 3 cases, phenazepam (1–3 mg) – 10 obs. From AD, venlafaxine (75–225 mg) – 7 cases, duloxetine (60 mg) – 3 cases, mirtazapine (30 mg) – 8 cases, paroxetine (20–60 mg) – 8 cases, citalopram (10 cases) -20 mg) - 11 obs., escitalopram (10-20 mg) - 12 obs. Typical antipsychotics were represented by the following drugs: haloperidol (1–10 mg) – 3 cases, thioridazine (20–40 mg) – 2 cases, trifluoperazine (5–10 mg) – 2 cases, sulpiride (100–400 mg) – 4 obs. Of the atypical neuroleptics, amisulpride (50-300 mg) - 2 cases, clozapine (25-100 mg) - 3 cases, olanzapine (5-10 mg) - 2 cases, risperidone (1 mg) - 1 case. nine0012 After selecting patients and including them in the study, quetiapine was added to the current pharmacotherapy at a dose of 25–300 mg for 1.5 months. In cases where a neuroleptic was used in the previous treatment regimen, it was replaced by quetiapine. The dose was set individually depending on the patient's condition and taking into account the tolerability of the drug.

nine0012 After selecting patients and including them in the study, quetiapine was added to the current pharmacotherapy at a dose of 25–300 mg for 1.5 months. In cases where a neuroleptic was used in the previous treatment regimen, it was replaced by quetiapine. The dose was set individually depending on the patient's condition and taking into account the tolerability of the drug.

Initially, 55 patients were included. During the study, 2 patients (with AF and OCD) refused to continue taking the drug without explanation, 3 patients (2 with SR, 1 with DR) were excluded due to the escalation of doses of benzodiazepine tranquilizers they admitted. A full course of therapy was completed in 50 patients, who were included in the analysis of the results. nine0012 Results

After the addition of quetiapine, in most cases, the condition of patients gradually improved. If at the time of the appointment of quetiapine, the condition of 11 patients (22%) was assessed by severity according to SHOKV (Table 4) as moderate, 39 patients (78%) - as severe, then by the end of therapy, a serious condition was recorded only in 3 (6% ), and of moderate severity - in 18 patients (36%) of the entire group. In the majority - 31 patients (62%) - the condition was assessed in the range from mild to normal. nine0012 As the dose of the drug was increased depending on the severity of the condition, but taking into account individual tolerance, after a week, most future responders showed a decrease in emotional tension, the intensity of anxiety, fear, and the severity of pathological bodily sensations. Particularly noticeable positive changes in the condition of patients often occurred after the 3rd week of quetiapine therapy. The average dose of quetiapine at the end of therapy was 136.1 mg/day. (Table 5). At the same time, it turned out that the doses differed significantly in patients with various disorders. The highest doses were taken by patients with OCD (286.4 mg/day), the lowest doses were taken by patients with somatic disorder (38.9mg/day) and GAD (64.3 mg/day). Patients with agoraphobia and depression occupied an intermediate position in this respect.

In the majority - 31 patients (62%) - the condition was assessed in the range from mild to normal. nine0012 As the dose of the drug was increased depending on the severity of the condition, but taking into account individual tolerance, after a week, most future responders showed a decrease in emotional tension, the intensity of anxiety, fear, and the severity of pathological bodily sensations. Particularly noticeable positive changes in the condition of patients often occurred after the 3rd week of quetiapine therapy. The average dose of quetiapine at the end of therapy was 136.1 mg/day. (Table 5). At the same time, it turned out that the doses differed significantly in patients with various disorders. The highest doses were taken by patients with OCD (286.4 mg/day), the lowest doses were taken by patients with somatic disorder (38.9mg/day) and GAD (64.3 mg/day). Patients with agoraphobia and depression occupied an intermediate position in this respect.

Table 6 shows that in more than half (29 patients - 58%) therapy with the addition of quetiapine led to positive results (very large improvement, or remission, and marked improvement), and only in 11 patients (22%) positive changes did not occur. were recorded, and in 10 (20%) they were clinically insignificant. Taking into account the resistance to previous therapy, the fact that remission was achieved in 9 patients seems significant.(18%) patients. When comparing the results by groups, it turned out that the therapeutic response was unevenly distributed. In general, the best results were obtained in patients with GAD (80% of respondents), while the most resistant to therapy were patients with OCD (36.6% of respondents). In the remaining groups, the results were approximately the same (55.5% of respondents).

were recorded, and in 10 (20%) they were clinically insignificant. Taking into account the resistance to previous therapy, the fact that remission was achieved in 9 patients seems significant.(18%) patients. When comparing the results by groups, it turned out that the therapeutic response was unevenly distributed. In general, the best results were obtained in patients with GAD (80% of respondents), while the most resistant to therapy were patients with OCD (36.6% of respondents). In the remaining groups, the results were approximately the same (55.5% of respondents).

Asking the question about the reasons for the success of combination therapy with the addition of quetiapine for seemingly such heterogeneous psychopathological formations, I would like to note the following. The studied cases were characterized by a high "cross" comorbidity, when a particular condition included individual signs of other disorders represented in this spectrum sample. Thus, the presence of comorbidity in a certain sense brought together the clinical picture in patients of the studied sample. If we move from a formally statistical assessment, which is the diagnosis according to ICD-10, to an essentially psychopathological one, then it is natural to assume that there are signs in the condition of patients that would be common to all the cases studied and which could presumably be a target for quetiapine therapy. . An analysis of the clinical material made it possible to establish that such a common symptom was pathological anxiety, anxiety, observed in all the studied patients. Varying from predominantly ideational in OCD to somato-vegetative in SR, anxiety was most sensitive to quetiapine therapy. In cases where the addition of quetiapine led to the formation of remission, success was achieved precisely due to the anti-anxiety effect of the drug. Patients' self-reports were also characterized by an emphasis on calming down, reducing unreasonable anxiety, and being overwhelmed by painful forebodings. nine0012 Thus, quetiapine makes it possible to optimize the therapy of psychopathological symptom complexes resistant to traditional treatment from the range of non-psychotic disorders, including severe anxiety, and can be used in combined pharmacotherapy.

If we move from a formally statistical assessment, which is the diagnosis according to ICD-10, to an essentially psychopathological one, then it is natural to assume that there are signs in the condition of patients that would be common to all the cases studied and which could presumably be a target for quetiapine therapy. . An analysis of the clinical material made it possible to establish that such a common symptom was pathological anxiety, anxiety, observed in all the studied patients. Varying from predominantly ideational in OCD to somato-vegetative in SR, anxiety was most sensitive to quetiapine therapy. In cases where the addition of quetiapine led to the formation of remission, success was achieved precisely due to the anti-anxiety effect of the drug. Patients' self-reports were also characterized by an emphasis on calming down, reducing unreasonable anxiety, and being overwhelmed by painful forebodings. nine0012 Thus, quetiapine makes it possible to optimize the therapy of psychopathological symptom complexes resistant to traditional treatment from the range of non-psychotic disorders, including severe anxiety, and can be used in combined pharmacotherapy.

Literature

1. Avedisova A. S. On the issue of dependence on benzodiazepines.

Psychiatry and psychopharmacology. 1999; 1

2. Krasnov V.N., Gurovich I.Ya. Clinical guide: models of diagnosis and treatment of mental and behavioral disorders. Moscow, 2000; 104–5. nine0012 3. Mosolov S.N. Fundamentals of psychopharmacotherapy. M., 1996.

4. Mosolov S.N. Clinical use of modern antidepressants. SPb., 1995; 565 p.

5. Smulevich A.B., Drobizhev M.Yu., Ivanov S.V. Clinical effects of benzodiazepine tranquilizers in psychiatry and general medicine. Moscow: Media Sphere, 2005.

6. D. S. Baldwin, I. M. Anderson, D. J. Nutt, B. Bandelow, A. Bond, J. R. T. Davidson, J. A. den Boer, N. A. Fineberg, M. Knapp, J. Scott, and H.–U. Wittchen Evidence–based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology J Psychopharmacol, November 1, 2005; nineteen(6): 567 - 596.

7. Ballenger JC (2001), Overview of different pharmacotherapies for attaining remission in generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 62(suppl 19):11–19.

8. Bandelow B, Hajak G, Holzrichter S, Kunert HJ, Ruther E. Assessing the efficacy of treatments for panic disorder and agoraphobia. I. Methodological problems. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995 Jun;10(2):83–93

9. Barranco SF, Thrash ML, Hackett E, Frey J, Ward J, Norris E. Early onset of response to doxepin treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. nineteen79 Jun;40(6):265–9.

10. Bruce S. E., Ruce, Yonkers, Otto, et. al. Influence of Psychiatric Comorbidity on Recovery and Recurrence in Generalized Anxiety Disorder,Social Phobia, and Panic Disorder: A 12–Year Prospective Study J Psychiatry 162:6, June 2005. 1181

11. Deakin JFW. The Role of Serotonin in Depression and Anxiety. Eur Psychiat 1998; 13.

12. DeMartinis NA, Rynn M, Rickels KR, Mandos LR. Prior Benzodiazepine Use and Buspirone Response in the Triatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:91–4.

J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:91–4.

13. Eison (1989), The new generation of serotonergic anxiolytics: possible clinical roles.

Psychopathology. 1989;22 Suppl 1:13–20. review.

14. El-Khayat R., Baldwin D., 1998, Antipsychotic drugs for non-psychotic patients: assessment of the benefit/risk ratio in generalized anxiety disorder Journal of Psychopharmacology, Vol. 12, no. 4, 323–329 (1998)

15. Feighner JP, Cohn JB. Analysis of individual symptoms in generalized anxiety––a pooled, multistudy, double–blind evaluation of buspirone. neuropsychobiology. nineteen89;21(3):124–30

16 McDougle CJ, Goodman WK, Leckman JF et al. (1994), Haloperidol addition in fluvoxamine–refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with and without tics. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 51(4):302–308.

17. Mottard JP, de la Sablonniere JF (1999), Olanzapine-induced obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am. J Psychiatry 156(5):799–800 [letter].

18. Nagy A: Long-term treatment with benzodiazepines: theoretical, ideological, and practical aspects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1987; 335:47–5

Nagy A: Long-term treatment with benzodiazepines: theoretical, ideological, and practical aspects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1987; 335:47–5

19. Nutt D., Argyropoulos S., Forshall S. Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Diagnosis, Treatment and Relationship to Other Anxiety Disorders. – Martin Dunitz, London, 1998, 97 p.

20. Nutt D, Rickels K, Stein D. Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Martin Dunitz Ltd., 2002.

21. Stein DJ, Bouwer C, Hawkridge S, Emsley RA (1997), Risperidone augmentation of

serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive–compulsive and related disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 58(3):119–122 [see comment p134].

22. Tiller JW. The new and newer antianxiety agents. Med J Aust. 1989 Dec 4-18;151(11-12):697-701.

23. Weiss EL, Potenza MN, McDougle CJ, et al. Olanzapine addition in obsessive–compulsive disorder refractory to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: an open–label case series. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999; 60:524–527.

24. Wurthmann, C., Klieser, E.