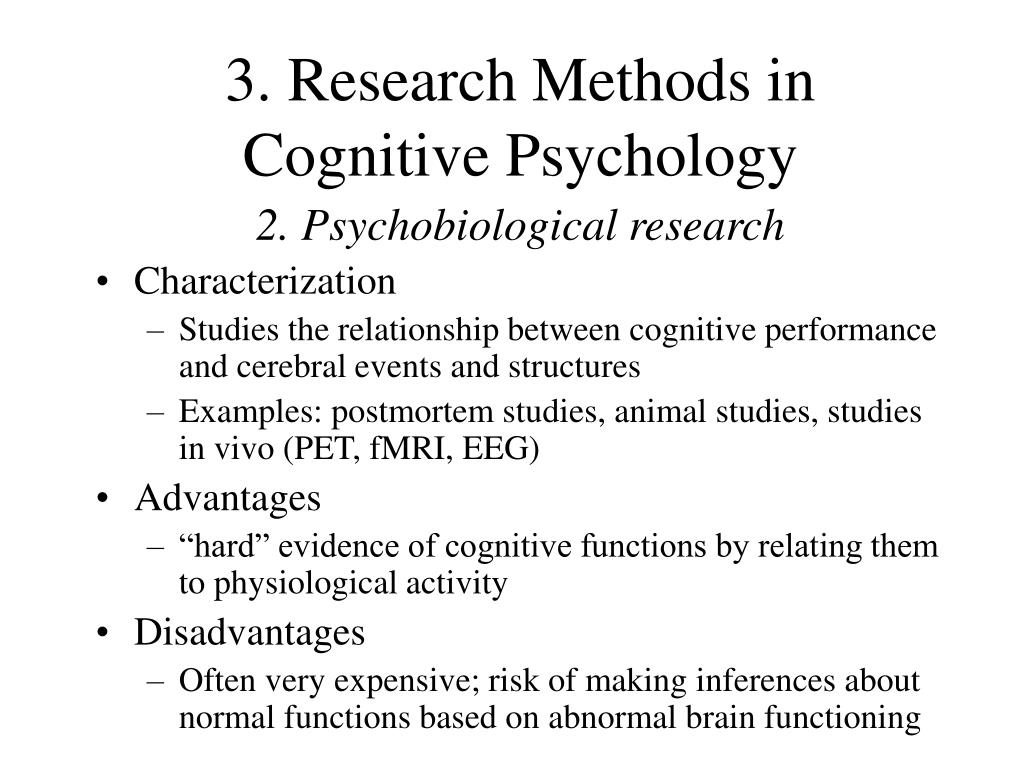

Methods of brain research

4.3 Psychologists Study the Brain Using Many Different Methods – Introduction to Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition

Chapter 4. Brains, Bodies, and Behaviour

Learning Objective

- Compare and contrast the techniques that scientists use to view and understand brain structures and functions.

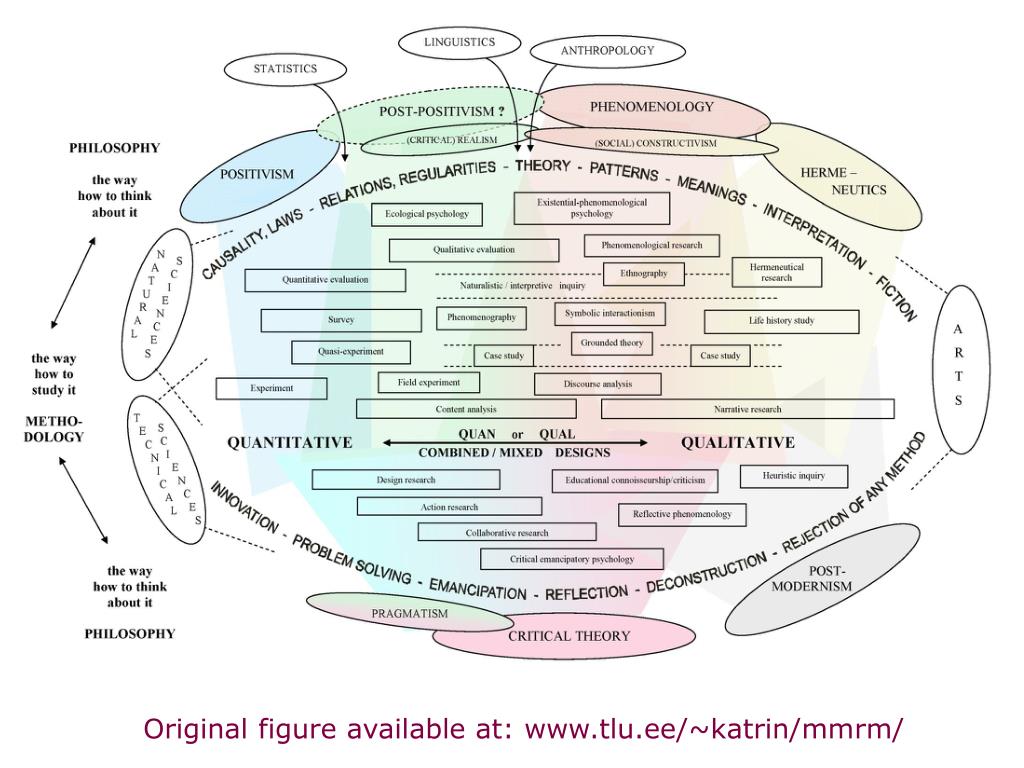

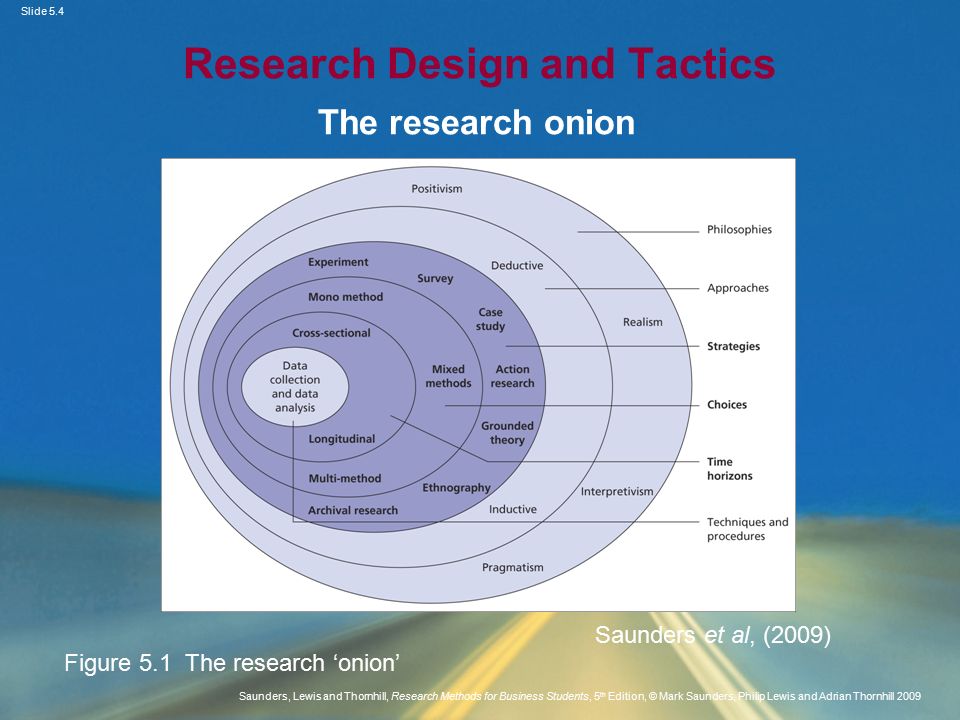

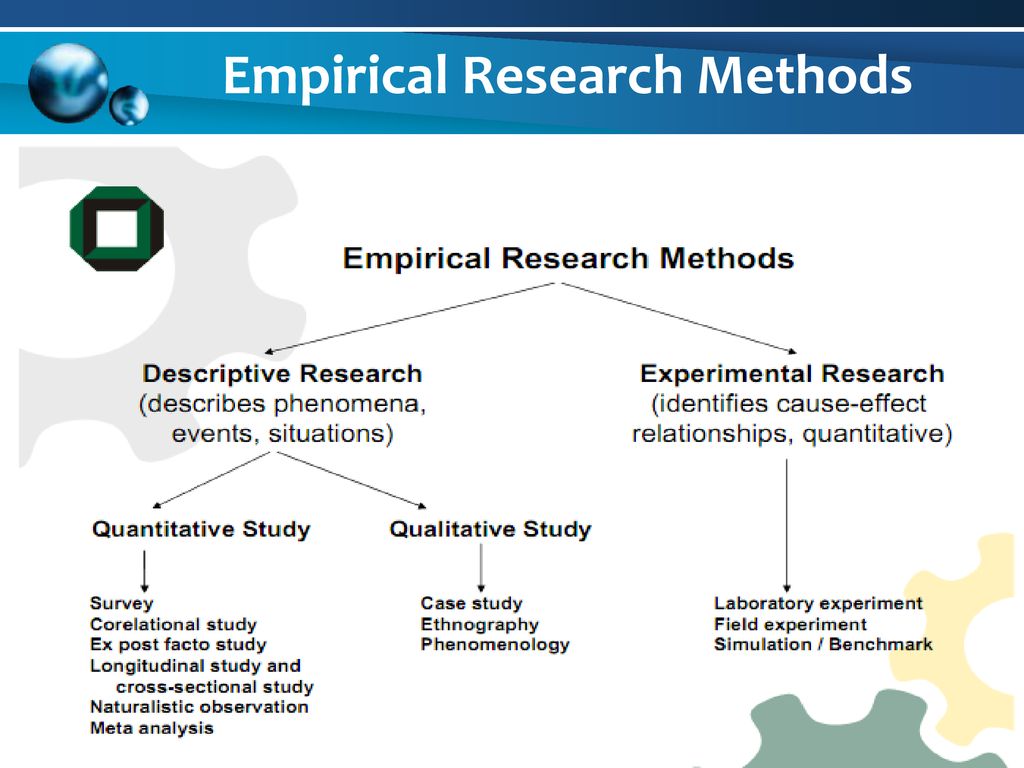

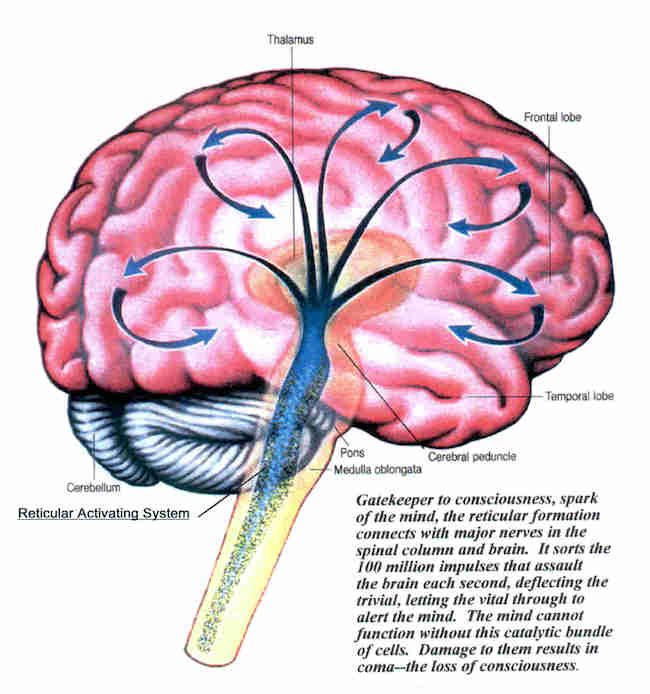

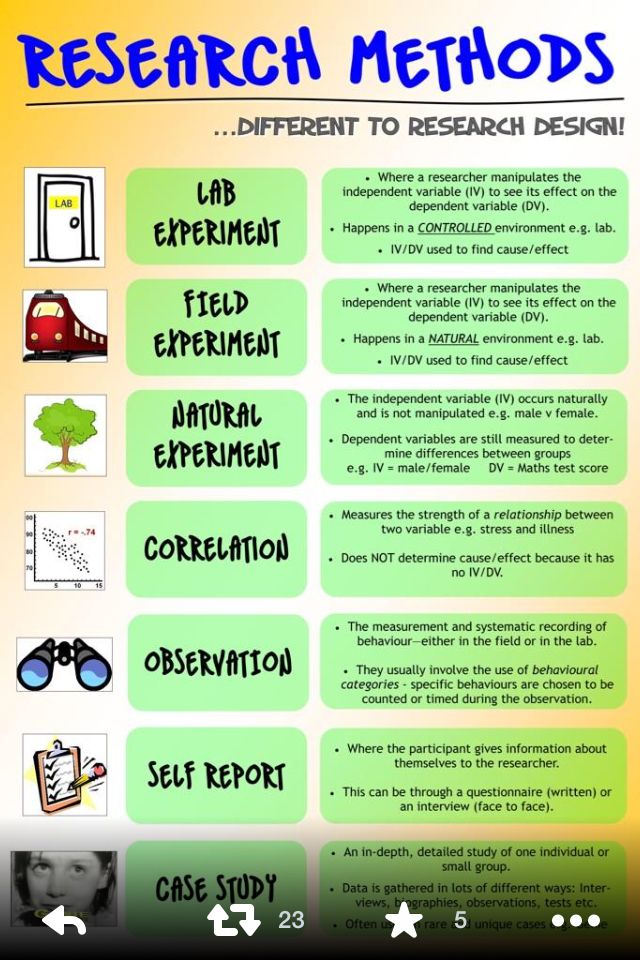

One problem in understanding the brain is that it is difficult to get a good picture of what is going on inside it. But there are a variety of empirical methods that allow scientists to look at brains in action, and the number of possibilities has increased dramatically in recent years with the introduction of new neuroimaging techniques. In this section we will consider the various techniques that psychologists use to learn about the brain. Each of the different techniques has some advantages, and when we put them together, we begin to get a relatively good picture of how the brain functions and which brain structures control which activities.

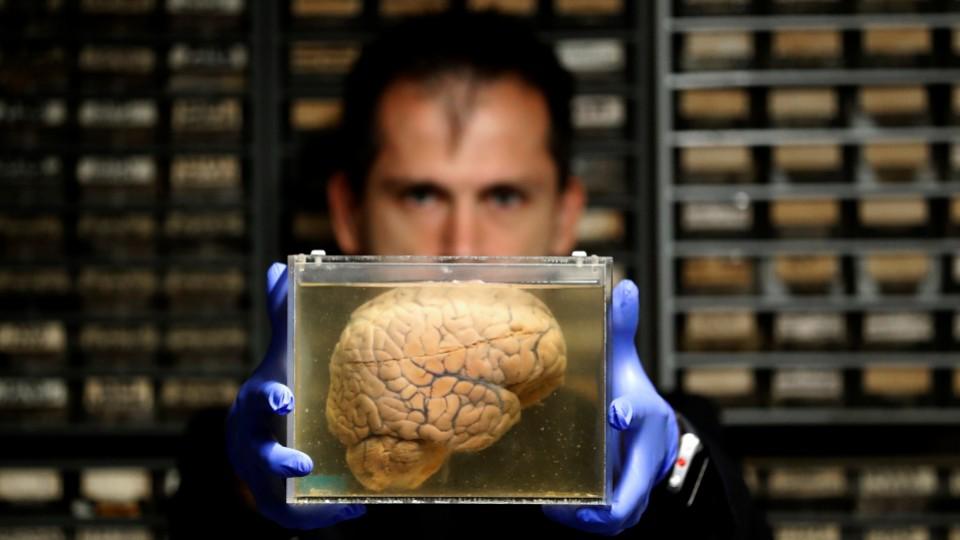

Perhaps the most immediate approach to visualizing and understanding the structure of the brain is to directly analyze the brains of human cadavers. When Albert Einstein died in 1955, his brain was removed and stored for later analysis. Researcher Marian Diamond (1999) later analyzed a section of Einstein’s cortex to investigate its characteristics. Diamond was interested in the role of glia, and she hypothesized that the ratio of glial cells to neurons was an important determinant of intelligence. To test this hypothesis, she compared the ratio of glia to neurons in Einstein’s brain with the ratio in the preserved brains of 11 other more “ordinary” men. However, Diamond was able to find support for only part of her research hypothesis. Although she found that Einstein’s brain had relatively more glia in all the areas that she studied than did the control group, the difference was only statistically significant in one of the areas she tested. Diamond admits a limitation in her study is that she had only one Einstein to compare with 11 ordinary men.

Lesions Provide a Picture of What Is Missing

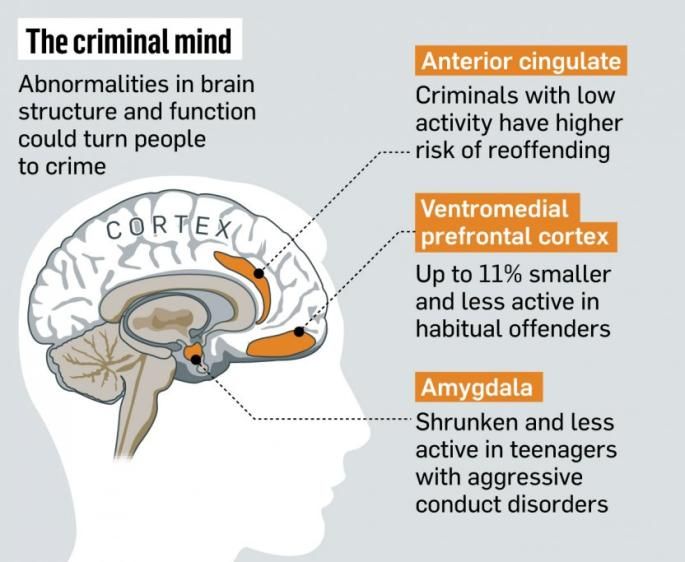

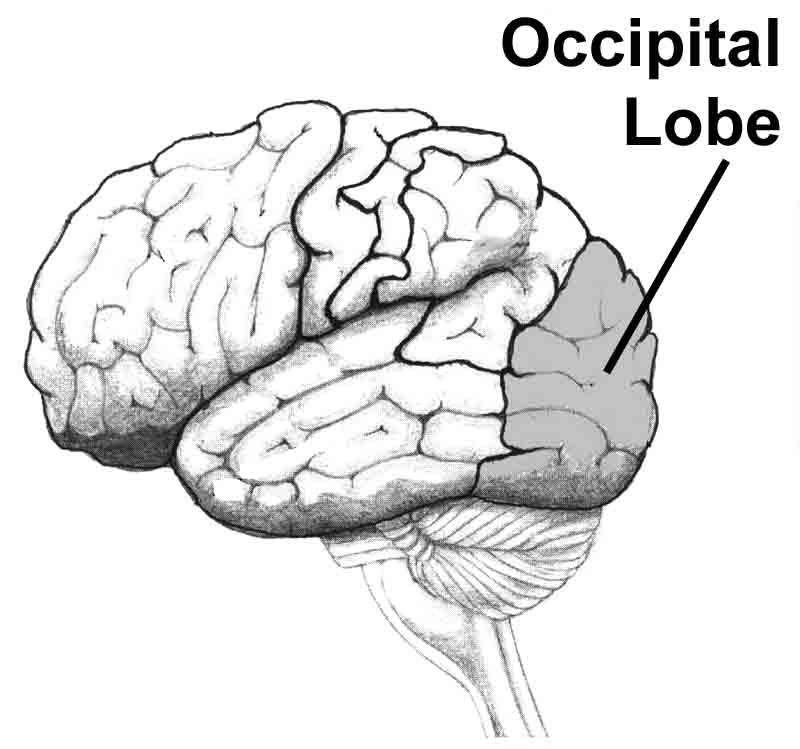

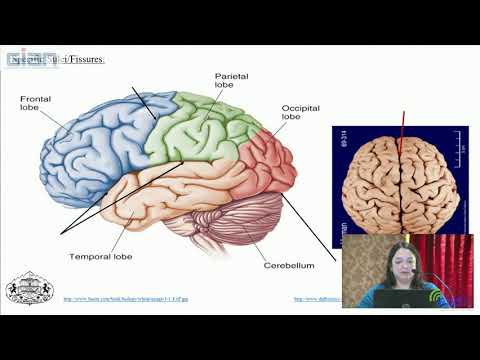

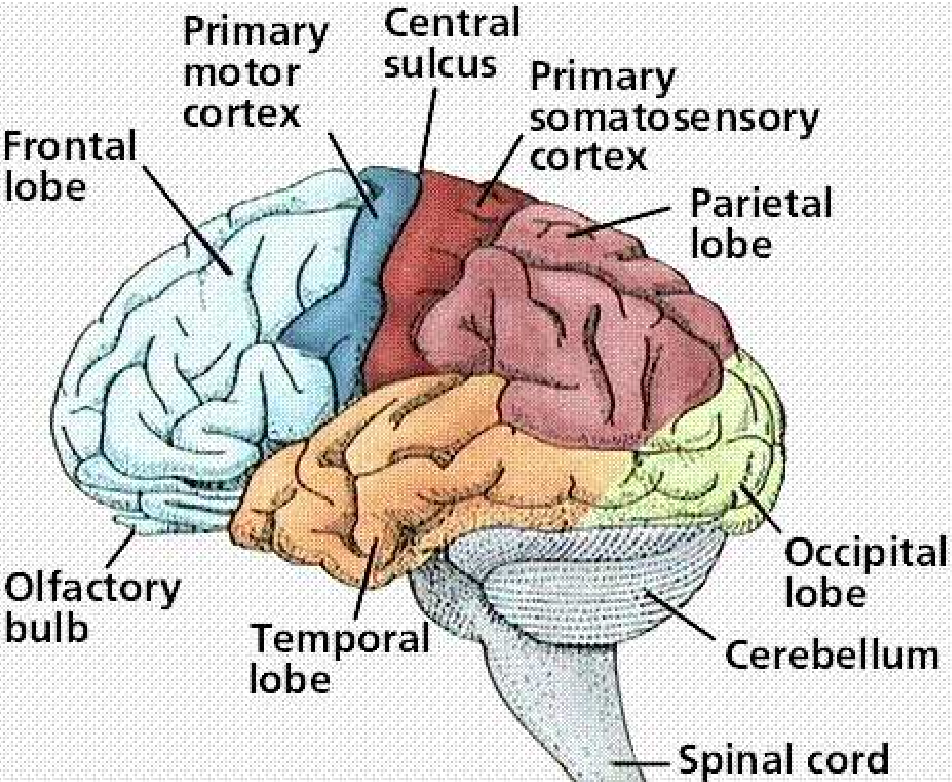

An advantage of the cadaver approach is that the brains can be fully studied, but an obvious disadvantage is that the brains are no longer active. In other cases, however, we can study living brains. The brains of living human beings may be damaged — as a result of strokes, falls, automobile accidents, gunshots, or tumours, for instance. These damages are called lesions. In rare occasions, brain lesions may be created intentionally through surgery, such as that designed to remove brain tumours or (as in split-brain patients) reduce the effects of epilepsy. Psychologists also sometimes intentionally create lesions in animals to study the effects on their behaviour. In so doing, they hope to be able to draw inferences about the likely functions of human brains from the effects of the lesions in animals. Lesions allow the scientist to observe any loss of brain function that may occur. For instance, when an individual suffers a stroke, a blood clot deprives part of the brain of oxygen, killing the neurons in the area and rendering that area unable to process information. In some cases, the result of the stroke is a specific lack of ability. For instance, if the stroke influences the occipital lobe, then vision may suffer, and if the stroke influences the areas associated with language or speech, these functions will suffer. In fact, our earliest understanding of the specific areas involved in speech and language were gained by studying patients who had experienced strokes.

In some cases, the result of the stroke is a specific lack of ability. For instance, if the stroke influences the occipital lobe, then vision may suffer, and if the stroke influences the areas associated with language or speech, these functions will suffer. In fact, our earliest understanding of the specific areas involved in speech and language were gained by studying patients who had experienced strokes.

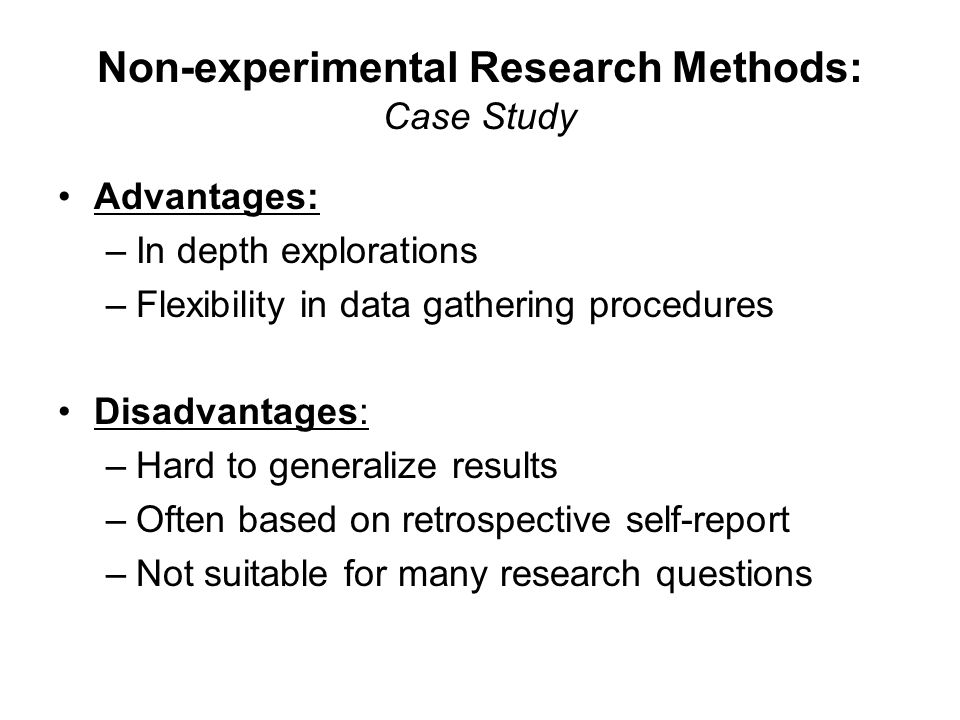

It is now known that a good part of our moral reasoning abilities is located in the frontal lobe, and at least some of this understanding comes from lesion studies. For instance, consider the well-known case of Phineas Gage (Figure 4.12) , a 25-year-old railroad worker who, as a result of an explosion, had an iron rod driven into his cheek and out through the top of his skull, causing major damage to his frontal lobe (Macmillan, 2000). Although, remarkably, Gage was able to return to work after the wounds healed, he no longer seemed to be the same person to those who knew him. The amiable, soft-spoken Gage had become irritable, rude, irresponsible, and dishonest. Although there are questions about the interpretation of this case study (Kotowicz, 2007), it did provide early evidence that the frontal lobe is involved in emotion and morality (Damasio et al., 2005). More recent and more controlled research has also used patients with lesions to investigate the source of moral reasoning. Michael Koenigs and his colleagues (Koenigs et al., 2007) asked groups of normal persons, individuals with lesions in the frontal lobes, and individuals with lesions in other places in the brain to respond to scenarios that involved doing harm to a person, even though the harm ultimately saved the lives of other people (Miller, 2008). In one of the scenarios the participants were asked if they would be willing to kill one person in order to prevent five other people from being killed. As you can see in Figure 4.13, “The Frontal Lobe and Moral Judgment,” they found that the individuals with lesions in the frontal lobe were significantly more likely to agree to do the harm than were individuals from the two other groups.

The amiable, soft-spoken Gage had become irritable, rude, irresponsible, and dishonest. Although there are questions about the interpretation of this case study (Kotowicz, 2007), it did provide early evidence that the frontal lobe is involved in emotion and morality (Damasio et al., 2005). More recent and more controlled research has also used patients with lesions to investigate the source of moral reasoning. Michael Koenigs and his colleagues (Koenigs et al., 2007) asked groups of normal persons, individuals with lesions in the frontal lobes, and individuals with lesions in other places in the brain to respond to scenarios that involved doing harm to a person, even though the harm ultimately saved the lives of other people (Miller, 2008). In one of the scenarios the participants were asked if they would be willing to kill one person in order to prevent five other people from being killed. As you can see in Figure 4.13, “The Frontal Lobe and Moral Judgment,” they found that the individuals with lesions in the frontal lobe were significantly more likely to agree to do the harm than were individuals from the two other groups.

Recording Electrical Activity in the Brain

In addition to lesion approaches, it is also possible to learn about the brain by studying the electrical activity created by the firing of its neurons. One approach, primarily used with animals, is to place detectors in the brain to study the responses of specific neurons. Research using these techniques has found, for instance, that there are specific neurons, known as feature detectors, in the visual cortex that detect movement, lines and edges, and even faces (Kanwisher, 2000).

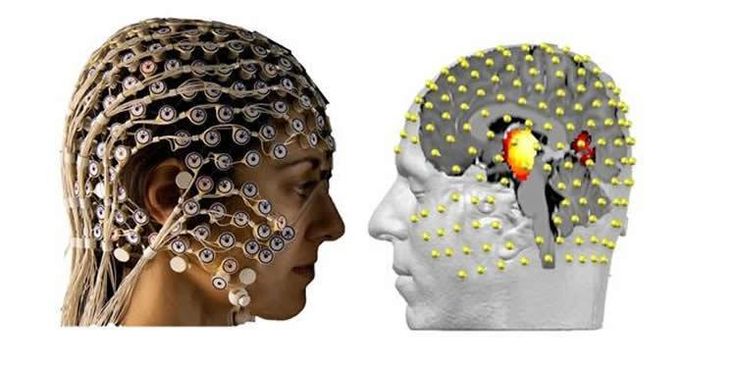

Figure 4.14 EEG Study. A participant in an EEG study with a number of electrodes placed around his head.

A less invasive approach, and one that can be used on living humans, is electroencephalography (EEG), as shown in Figure 4.14. The EEG is a technique that records the electrical activity produced by the brain’s neurons through the use of electrodes that are placed around the research participant’s head. An EEG can show if a person is asleep, awake, or anesthetized because the brainwave patterns are known to differ during each state. EEGs can also track the waves that are produced when a person is reading, writing, and speaking, and are useful for understanding brain abnormalities, such as epilepsy. A particular advantage of EEG is that the participant can move around while the recordings are being taken, which is useful when measuring brain activity in children, who often have difficulty keeping still. Furthermore, by following electrical impulses across the surface of the brain, researchers can observe changes over very fast time periods.

Peeking inside the Brain: Neuroimaging

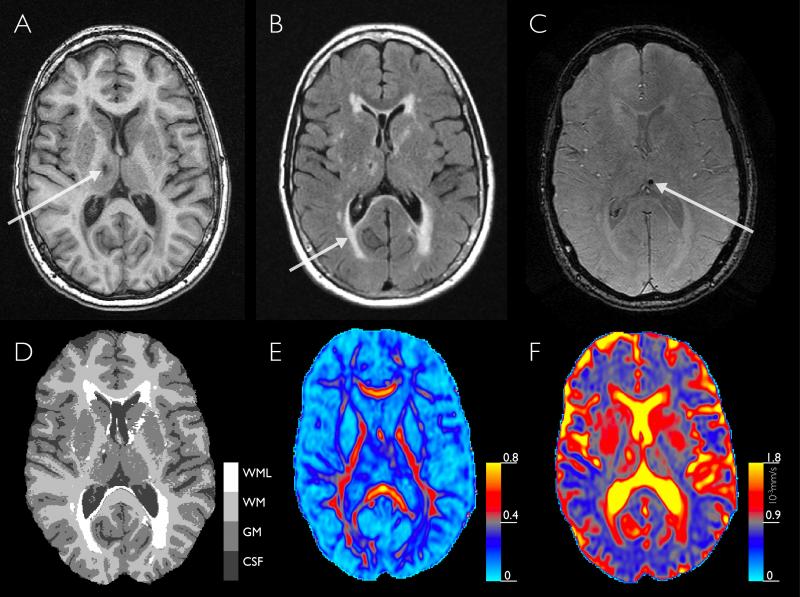

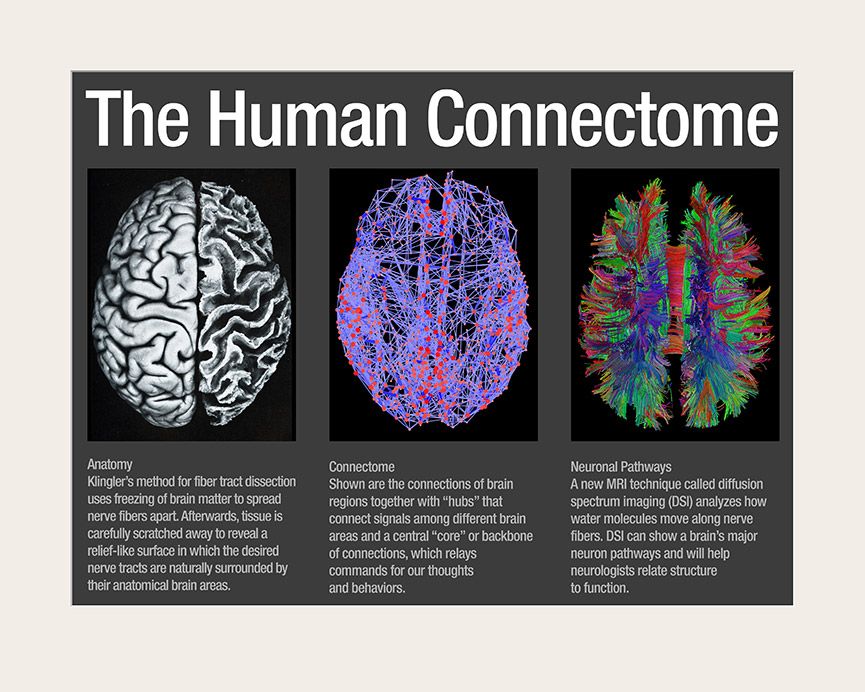

Although the EEG can provide information about the general patterns of electrical activity within the brain, and although the EEG allows the researcher to see these changes quickly as they occur in real time, the electrodes must be placed on the surface of the skull, and each electrode measures brainwaves from large areas of the brain. As a result, EEGs do not provide a very clear picture of the structure of the brain. But techniques exist to provide more specific brain images. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a type of brain scan that uses a magnetic field to create images of brain activity in each brain area. The patient lies on a bed within a large cylindrical structure containing a very strong magnet. Neurons that are firing use more oxygen, and the need for oxygen increases blood flow to the area. The fMRI detects the amount of blood flow in each brain region, and thus is an indicator of neural activity. Very clear and detailed pictures of brain structures can be produced via fMRI (see Figure 4.15, “fMRI Image”). Often, the images take the form of cross-sectional “slices” that are obtained as the magnetic field is passed across the brain. The images of these slices are taken repeatedly and are superimposed on images of the brain structure itself to show how activity changes in different brain structures over time.

As a result, EEGs do not provide a very clear picture of the structure of the brain. But techniques exist to provide more specific brain images. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a type of brain scan that uses a magnetic field to create images of brain activity in each brain area. The patient lies on a bed within a large cylindrical structure containing a very strong magnet. Neurons that are firing use more oxygen, and the need for oxygen increases blood flow to the area. The fMRI detects the amount of blood flow in each brain region, and thus is an indicator of neural activity. Very clear and detailed pictures of brain structures can be produced via fMRI (see Figure 4.15, “fMRI Image”). Often, the images take the form of cross-sectional “slices” that are obtained as the magnetic field is passed across the brain. The images of these slices are taken repeatedly and are superimposed on images of the brain structure itself to show how activity changes in different brain structures over time. When the research participant is asked to engage in tasks while in the scanner (e.g., by playing a game with another person), the images can show which parts of the brain are associated with which types of tasks. Another advantage of the fMRI is that it is noninvasive. The research participant simply enters the machine and the scans begin. Although the scanners themselves are expensive, the advantages of fMRIs are substantial, and they are now available in many university and hospital settings. The fMRI is now the most commonly used method of learning about brain structure.

When the research participant is asked to engage in tasks while in the scanner (e.g., by playing a game with another person), the images can show which parts of the brain are associated with which types of tasks. Another advantage of the fMRI is that it is noninvasive. The research participant simply enters the machine and the scans begin. Although the scanners themselves are expensive, the advantages of fMRIs are substantial, and they are now available in many university and hospital settings. The fMRI is now the most commonly used method of learning about brain structure.

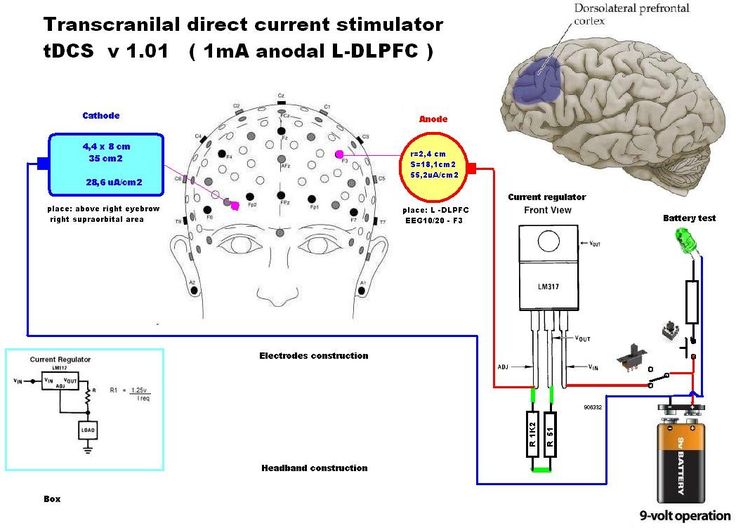

There is still one more approach that is being more frequently implemented to understand brain function, and although it is new, it may turn out to be the most useful of all. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a procedure in which magnetic pulses are applied to the brain of a living person with the goal of temporarily and safely deactivating a small brain region. In TMS studies the research participant is first scanned in an fMRI machine to determine the exact location of the brain area to be tested. Then the electrical stimulation is provided to the brain before or while the participant is working on a cognitive task, and the effects of the stimulation on performance are assessed. If the participant’s ability to perform the task is influenced by the presence of the stimulation, the researchers can conclude that this particular area of the brain is important to carrying out the task. The primary advantage of TMS is that it allows the researcher to draw causal conclusions about the influence of brain structures on thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. When the TMS pulses are applied, the brain region becomes less active, and this deactivation is expected to influence the research participant’s responses. Current research has used TMS to study the brain areas responsible for emotion and cognition and their roles in how people perceive intention and approach moral reasoning (Kalbe et al.

In TMS studies the research participant is first scanned in an fMRI machine to determine the exact location of the brain area to be tested. Then the electrical stimulation is provided to the brain before or while the participant is working on a cognitive task, and the effects of the stimulation on performance are assessed. If the participant’s ability to perform the task is influenced by the presence of the stimulation, the researchers can conclude that this particular area of the brain is important to carrying out the task. The primary advantage of TMS is that it allows the researcher to draw causal conclusions about the influence of brain structures on thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. When the TMS pulses are applied, the brain region becomes less active, and this deactivation is expected to influence the research participant’s responses. Current research has used TMS to study the brain areas responsible for emotion and cognition and their roles in how people perceive intention and approach moral reasoning (Kalbe et al. , 2010; Van den Eynde et al., 2010; Young, Camprodon, Hauser, Pascual-Leone, & Saxe, 2010). TMS is also used as a treatment for a variety of psychological conditions, including migraine, Parkinson’s disease, and major depressive disorder.

, 2010; Van den Eynde et al., 2010; Young, Camprodon, Hauser, Pascual-Leone, & Saxe, 2010). TMS is also used as a treatment for a variety of psychological conditions, including migraine, Parkinson’s disease, and major depressive disorder.

Research Focus: Cyberostracism

Neuroimaging techniques have important implications for understanding our behaviour, including our responses to those around us. Naomi Eisenberger and her colleagues (2003) tested the hypothesis that people who were excluded by others would report emotional distress and that images of their brains would show that they experienced pain in the same part of the brain where physical pain is normally experienced. In the experiment, 13 participants were each placed into an fMRI brain-imaging machine. The participants were told that they would be playing a computer “Cyberball” game with two other players who were also in fMRI machines (the two opponents did not actually exist, and their responses were controlled by the computer). Each of the participants was measured under three different conditions. In the first part of the experiment, the participants were told that as a result of technical difficulties, the link to the other two scanners could not yet be made, and thus at first they could not engage in, but only watch, the game play. This allowed the researchers to take a baseline fMRI reading. Then, during a second, inclusion, scan, the participants played the game, supposedly with the two other players. During this time, the other players threw the ball to the participants. In the third, exclusion, scan, however, the participants initially received seven throws from the other two players but were then excluded from the game because the two players stopped throwing the ball to the participants for the remainder of the scan (45 throws). The results of the analyses showed that activity in two areas of the frontal lobe was significantly greater during the exclusion scan than during the inclusion scan. Because these brain regions are known from prior research to be active for individuals who are experiencing physical pain, the authors concluded that these results show that the physiological brain responses associated with being socially excluded by others are similar to brain responses experienced upon physical injury.

Each of the participants was measured under three different conditions. In the first part of the experiment, the participants were told that as a result of technical difficulties, the link to the other two scanners could not yet be made, and thus at first they could not engage in, but only watch, the game play. This allowed the researchers to take a baseline fMRI reading. Then, during a second, inclusion, scan, the participants played the game, supposedly with the two other players. During this time, the other players threw the ball to the participants. In the third, exclusion, scan, however, the participants initially received seven throws from the other two players but were then excluded from the game because the two players stopped throwing the ball to the participants for the remainder of the scan (45 throws). The results of the analyses showed that activity in two areas of the frontal lobe was significantly greater during the exclusion scan than during the inclusion scan. Because these brain regions are known from prior research to be active for individuals who are experiencing physical pain, the authors concluded that these results show that the physiological brain responses associated with being socially excluded by others are similar to brain responses experienced upon physical injury. Further research (Chen, Williams, Fitness, & Newton, 2008; Wesselmann, Bagg, & Williams, 2009) has documented that people react to being excluded in a variety of situations with a variety of emotions and behaviours. People who feel that they are excluded, or even those who observe other people being excluded, not only experience pain, but feel worse about themselves and their relationships with people more generally, and they may work harder to try to restore their connections with others.

Further research (Chen, Williams, Fitness, & Newton, 2008; Wesselmann, Bagg, & Williams, 2009) has documented that people react to being excluded in a variety of situations with a variety of emotions and behaviours. People who feel that they are excluded, or even those who observe other people being excluded, not only experience pain, but feel worse about themselves and their relationships with people more generally, and they may work harder to try to restore their connections with others.

Key Takeaways

- Studying the brains of cadavers can lead to discoveries about brain structure, but these studies are limited because the brain is no longer active.

- Lesion studies are informative about the effects of lesions on different brain regions.

- Electrophysiological recording may be used in animals to directly measure brain activity.

- Measures of electrical activity in the brain, such as electroencephalography (EEG), are used to assess brainwave patterns and activity.

- Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) measures blood flow in the brain during different activities, providing information about the activity of neurons and thus the functions of brain regions.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is used to temporarily and safely deactivate a small brain region, with the goal of testing the causal effects of the deactivation on behaviour.

References

Chen, Z., Williams, K. D., Fitness, J., & Newton, N. C. (2008). When hurt will not heal: Exploring the capacity to relive social and physical pain. Psychological Science, 19(8), 789–795.

Damasio, H., Grabowski, T., Frank, R., Galaburda, A. M., Damasio, A. R., Cacioppo, J. T., & Berntson, G. G. (2005). The return of Phineas Gage: Clues about the brain from the skull of a famous patient. In Social neuroscience: Key readings (pp. 21–28). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Diamond, M. C. (1999). Why Einstein’s brain? New Horizons for Learning. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20111007191916/http://education.jhu.edu/newhorizons/Neurosciences/articles/einstein/

Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20111007191916/http://education.jhu.edu/newhorizons/Neurosciences/articles/einstein/

Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302(5643), 290–292.

Kalbe, E., Schlegel, M., Sack, A. T., Nowak, D. A., Dafotakis, M., Bangard, C., & Kessler, J. (2010). Dissociating cognitive from affective theory of mind: A TMS study. Cortex: A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior, 46(6), 769–780.

Kanwisher, N. (2000). Domain specificity in face perception. Nature Neuroscience, 3(8), 759–763.

Koenigs, M., Young, L., Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., Cushman, F., Hauser, M., & Damasio, A. (2007). Damage to the prefontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgments. Nature, 446(7138), 908–911.

Kotowicz, Z. (2007). The strange case of Phineas Gage. History of the Human Sciences, 20(1), 115–131.

Macmillan, M. (2000). An odd kind of fame: Stories of Phineas Gage. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Miller, G. (2008). The roots of morality. Science, 320, 734–737.

Van den Eynde, F., Claudino, A. M., Mogg, A., Horrell, L., Stahl, D., & Schmidt, U. (2010). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces cue-induced food craving in bulimic disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 67(8), 793–795.

Wesselmann, E. D., Bagg, D., & Williams, K. D. (2009). “I feel your pain”: The effects of observing ostracism on the ostracism detection system. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(6), 1308–1311.

Young, L., Camprodon, J. A., Hauser, M., Pascual-Leone, A., & Saxe, R. (2010). Disruption of the right temporoparietal junction with transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces the role of beliefs in moral judgments. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(15), 6753–6758.

Image Attributions

Figure 4. 12: “Phineas gage – 1868 skull diagram” by John M. Harlow, M.D. (http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Phineas_gage_-_1868_skull_diagram.jpg) is in the public domain.

12: “Phineas gage – 1868 skull diagram” by John M. Harlow, M.D. (http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Phineas_gage_-_1868_skull_diagram.jpg) is in the public domain.

Figure 4.14: “EEG cap” by Thuglas (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EEG_cap.jpg) is in the public domain.

Figure 4.15: Face recognition by National Institutes of Health (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Face_recognition.jpg) is in public domain.

Long Descriptions

| Control Participants | Participants with lesions in areas other than the frontal lobes | Participants with lesions in the frontal lobes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of participants who engaged in harm | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.46 |

[Return to Figure 4.13]

3.3 Psychologists Study the Brain Using Many Different Methods – Introduction to Psychology

Learning Objective

- Compare and contrast the techniques that scientists use to view and understand brain structures and functions.

One problem in understanding the brain is that it is difficult to get a good picture of what is going on inside it. But there are a variety of empirical methods that allow scientists to look at brains in action, and the number of possibilities has increased dramatically in recent years with the introduction of new neuroimaging techniques. In this section we will consider the various techniques that psychologists use to learn about the brain. Each of the different techniques has some advantages, and when we put them together, we begin to get a relatively good picture of how the brain functions and which brain structures control which activities.

Perhaps the most immediate approach to visualizing and understanding the structure of the brain is to directly analyze the brains of human cadavers. When Albert Einstein died in 1955, his brain was removed and stored for later analysis. Researcher Marian Diamond (1999) later analyzed a section of the Einstein’s cortex to investigate its characteristics. Diamond was interested in the role of glia, and she hypothesized that the ratio of glial cells to neurons was an important determinant of intelligence. To test this hypothesis, she compared the ratio of glia to neurons in Einstein’s brain with the ratio in the preserved brains of 11 other more “ordinary” men. However, Diamond was able to find support for only part of her research hypothesis. Although she found that Einstein’s brain had relatively more glia in all the areas that she studied than did the control group, the difference was only statistically significant in one of the areas she tested. Diamond admits a limitation in her study is that she had only one Einstein to compare with 11 ordinary men.

Diamond was interested in the role of glia, and she hypothesized that the ratio of glial cells to neurons was an important determinant of intelligence. To test this hypothesis, she compared the ratio of glia to neurons in Einstein’s brain with the ratio in the preserved brains of 11 other more “ordinary” men. However, Diamond was able to find support for only part of her research hypothesis. Although she found that Einstein’s brain had relatively more glia in all the areas that she studied than did the control group, the difference was only statistically significant in one of the areas she tested. Diamond admits a limitation in her study is that she had only one Einstein to compare with 11 ordinary men.

Lesions Provide a Picture of What Is Missing

An advantage of the cadaver approach is that the brains can be fully studied, but an obvious disadvantage is that the brains are no longer active. In other cases, however, we can study living brains. The brains of living human beings may be damaged, for instance, as a result of strokes, falls, automobile accidents, gunshots, or tumors. These damages are called lesions. In rare occasions, brain lesions may be created intentionally through surgery, such as that designed to remove brain tumors or (as in split-brain patients) to reduce the effects of epilepsy. Psychologists also sometimes intentionally create lesions in animals to study the effects on their behavior. In so doing, they hope to be able to draw inferences about the likely functions of human brains from the effects of the lesions in animals.

These damages are called lesions. In rare occasions, brain lesions may be created intentionally through surgery, such as that designed to remove brain tumors or (as in split-brain patients) to reduce the effects of epilepsy. Psychologists also sometimes intentionally create lesions in animals to study the effects on their behavior. In so doing, they hope to be able to draw inferences about the likely functions of human brains from the effects of the lesions in animals.

Lesions allow the scientist to observe any loss of brain function that may occur. For instance, when an individual suffers a stroke, a blood clot deprives part of the brain of oxygen, killing the neurons in the area and rendering that area unable to process information. In some cases, the result of the stroke is a specific lack of ability. For instance, if the stroke influences the occipital lobe, then vision may suffer, and if the stroke influences the areas associated with language or speech, these functions will suffer. In fact, our earliest understanding of the specific areas involved in speech and language were gained by studying patients who had experienced strokes.

In fact, our earliest understanding of the specific areas involved in speech and language were gained by studying patients who had experienced strokes.

Figure 3.13

John M. Harlow – Phineas Gage – public domain.

Areas in the frontal lobe of Phineas Gage were damaged when a metal rod blasted through it. Although Gage lived through the accident, his personality, emotions, and moral reasoning were influenced. The accident helped scientists understand the role of the frontal lobe in these processes.

It is now known that a good part of our moral reasoning abilities are located in the frontal lobe, and at least some of this understanding comes from lesion studies. For instance, consider the well-known case of Phineas Gage, a 25-year-old railroad worker who, as a result of an explosion, had an iron rod driven into his cheek and out through the top of his skull, causing major damage to his frontal lobe (Macmillan, 2000). Although remarkably Gage was able to return to work after the wounds healed, he no longer seemed to be the same person to those who knew him. The amiable, soft-spoken Gage had become irritable, rude, irresponsible, and dishonest. Although there are questions about the interpretation of this case study (Kotowicz, 2007), it did provide early evidence that the frontal lobe is involved in emotion and morality (Damasio et al., 2005).

The amiable, soft-spoken Gage had become irritable, rude, irresponsible, and dishonest. Although there are questions about the interpretation of this case study (Kotowicz, 2007), it did provide early evidence that the frontal lobe is involved in emotion and morality (Damasio et al., 2005).

More recent and more controlled research has also used patients with lesions to investigate the source of moral reasoning. Michael Koenigs and his colleagues (Koenigs et al., 2007) asked groups of normal persons, individuals with lesions in the frontal lobes, and individuals with lesions in other places in the brain to respond to scenarios that involved doing harm to a person, even though the harm ultimately saved the lives of other people (Miller, 2008).

In one of the scenarios the participants were asked if they would be willing to kill one person in order to prevent five other people from being killed. As you can see in Figure 3.14 “The Frontal Lobe and Moral Judgment”, they found that the individuals with lesions in the frontal lobe were significantly more likely to agree to do the harm than were individuals from the two other groups.

Figure 3.14 The Frontal Lobe and Moral Judgment

Koenigs and his colleagues (2007) found that the frontal lobe is important in moral judgment. Persons with lesions in the frontal lobe were more likely to be willing to harm one person in order to save the lives of five others than were control participants or those with lesions in other parts of the brain.

Recording Electrical Activity in the Brain

In addition to lesion approaches, it is also possible to learn about the brain by studying the electrical activity created by the firing of its neurons. One approach, primarily used with animals, is to place detectors in the brain to study the responses of specific neurons. Research using these techniques has found, for instance, that there are specific neurons, known as feature detectors, in the visual cortex that detect movement, lines and edges, and even faces (Kanwisher, 2000).

Figure 3.15

Festive Colors – CC BY-SA 2. 0.

0.

A participant in an EEG study has a number of electrodes placed around the head, which allows the researcher to study the activity of the person’s brain. The patterns of electrical activity vary depending on the participant’s current state (e.g., whether he or she is sleeping or awake) and on the tasks the person is engaging in.

A less invasive approach, and one that can be used on living humans, is electroencephalography (EEG). The EEG is a technique that records the electrical activity produced by the brain’s neurons through the use of electrodes that are placed around the research participant’s head. An EEG can show if a person is asleep, awake, or anesthetized because the brain wave patterns are known to differ during each state. EEGs can also track the waves that are produced when a person is reading, writing, and speaking, and are useful for understanding brain abnormalities, such as epilepsy. A particular advantage of EEG is that the participant can move around while the recordings are being taken, which is useful when measuring brain activity in children who often have difficulty keeping still. Furthermore, by following electrical impulses across the surface of the brain, researchers can observe changes over very fast time periods.

Furthermore, by following electrical impulses across the surface of the brain, researchers can observe changes over very fast time periods.

Peeking Inside the Brain: Neuroimaging

Although the EEG can provide information about the general patterns of electrical activity within the brain, and although the EEG allows the researcher to see these changes quickly as they occur in real time, the electrodes must be placed on the surface of the skull and each electrode measures brain waves from large areas of the brain. As a result, EEGs do not provide a very clear picture of the structure of the brain.

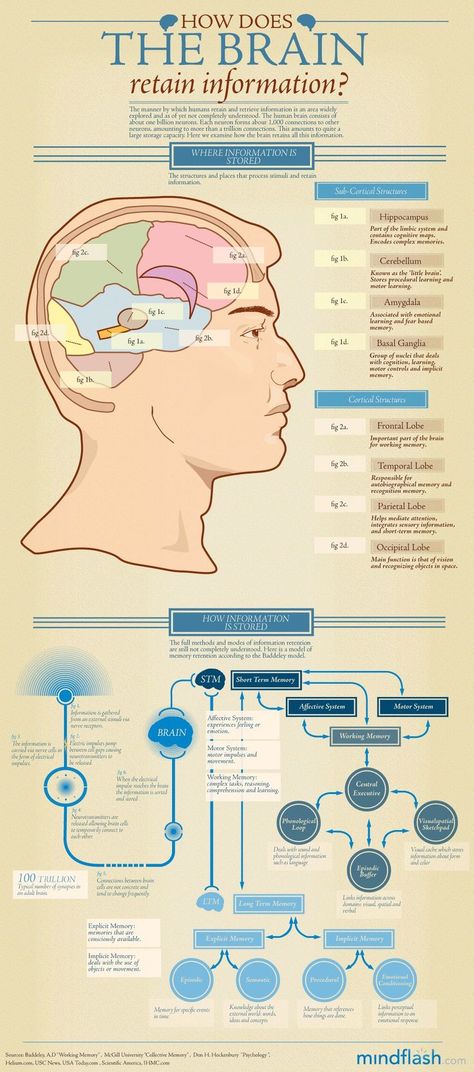

But techniques exist to provide more specific brain images. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a type of brain scan that uses a magnetic field to create images of brain activity in each brain area. The patient lies on a bed within a large cylindrical structure containing a very strong magnet. Neurons that are firing use more oxygen, and the need for oxygen increases blood flow to the area. The fMRI detects the amount of blood flow in each brain region, and thus is an indicator of neural activity.

The fMRI detects the amount of blood flow in each brain region, and thus is an indicator of neural activity.

Very clear and detailed pictures of brain structures (see, e.g., Figure 3.16 “fMRI Image”) can be produced via fMRI. Often, the images take the form of cross-sectional “slices” that are obtained as the magnetic field is passed across the brain. The images of these slices are taken repeatedly and are superimposed on images of the brain structure itself to show how activity changes in different brain structures over time. When the research participant is asked to engage in tasks while in the scanner (e.g., by playing a game with another person), the images can show which parts of the brain are associated with which types of tasks. Another advantage of the fMRI is that is it noninvasive. The research participant simply enters the machine and the scans begin.

Although the scanners themselves are expensive, the advantages of fMRIs are substantial, and they are now available in many university and hospital settings. fMRI is now the most commonly used method of learning about brain structure.

fMRI is now the most commonly used method of learning about brain structure.

Figure 3.16 fMRI Image

The fMRI creates brain images of brain structure and activity. In this image the red and yellow areas represent increased blood flow and thus increased activity. From your knowledge of brain structure, can you guess what this person is doing?

Photo courtesy of the National Institutes of Health, Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

There is still one more approach that is being more frequently implemented to understand brain function, and although it is new, it may turn out to be the most useful of all. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a procedure in which magnetic pulses are applied to the brain of living persons with the goal of temporarily and safely deactivating a small brain region. In TMS studies the research participant is first scanned in an fMRI machine to determine the exact location of the brain area to be tested. Then the electrical stimulation is provided to the brain before or while the participant is working on a cognitive task, and the effects of the stimulation on performance are assessed. If the participant’s ability to perform the task is influenced by the presence of the stimulation, then the researchers can conclude that this particular area of the brain is important to carrying out the task.

If the participant’s ability to perform the task is influenced by the presence of the stimulation, then the researchers can conclude that this particular area of the brain is important to carrying out the task.

The primary advantage of TMS is that it allows the researcher to draw causal conclusions about the influence of brain structures on thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. When the TMS pulses are applied, the brain region becomes less active, and this deactivation is expected to influence the research participant’s responses. Current research has used TMS to study the brain areas responsible for emotion and cognition and their roles in how people perceive intention and approach moral reasoning (Kalbe et al., 2010; Van den Eynde et al., 2010; Young, Camprodon, Hauser, Pascual-Leone, & Saxe, 2010). TMS is also used as a treatment for a variety of psychological conditions, including migraine, Parkinson’s disease, and major depressive disorder.

Research Focus: Cyberostracism

Neuroimaging techniques have important implications for understanding our behavior, including our responses to those around us. Naomi Eisenberger and her colleagues (2003) tested the hypothesis that people who were excluded by others would report emotional distress and that images of their brains would show that they experienced pain in the same part of the brain where physical pain is normally experienced. In the experiment, 13 participants were each placed into an fMRI brain-imaging machine. The participants were told that they would be playing a computer “Cyberball” game with two other players who were also in fMRI machines (the two opponents did not actually exist, and their responses were controlled by the computer).

Naomi Eisenberger and her colleagues (2003) tested the hypothesis that people who were excluded by others would report emotional distress and that images of their brains would show that they experienced pain in the same part of the brain where physical pain is normally experienced. In the experiment, 13 participants were each placed into an fMRI brain-imaging machine. The participants were told that they would be playing a computer “Cyberball” game with two other players who were also in fMRI machines (the two opponents did not actually exist, and their responses were controlled by the computer).

Each of the participants was measured under three different conditions. In the first part of the experiment, the participants were told that as a result of technical difficulties, the link to the other two scanners could not yet be made, and thus at first they could not engage in, but only watch, the game play. This allowed the researchers to take a baseline fMRI reading. Then, during a second inclusion scan, the participants played the game, supposedly with the two other players. During this time, the other players threw the ball to the participants. In the third, exclusion, scan, however, the participants initially received seven throws from the other two players but were then excluded from the game because the two players stopped throwing the ball to the participants for the remainder of the scan (45 throws).

During this time, the other players threw the ball to the participants. In the third, exclusion, scan, however, the participants initially received seven throws from the other two players but were then excluded from the game because the two players stopped throwing the ball to the participants for the remainder of the scan (45 throws).

The results of the analyses showed that activity in two areas of the frontal lobe was significantly greater during the exclusion scan than during the inclusion scan. Because these brain regions are known from prior research to be active for individuals who are experiencing physical pain, the authors concluded that these results show that the physiological brain responses associated with being socially excluded by others are similar to brain responses experienced upon physical injury.

Further research (Chen, Williams, Fitness, & Newton, 2008; Wesselmann, Bagg, & Williams, 2009) has documented that people react to being excluded in a variety of situations with a variety of emotions and behaviors. People who feel that they are excluded, or even those who observe other people being excluded, not only experience pain, but feel worse about themselves and their relationships with people more generally, and they may work harder to try to restore their connections with others.

People who feel that they are excluded, or even those who observe other people being excluded, not only experience pain, but feel worse about themselves and their relationships with people more generally, and they may work harder to try to restore their connections with others.

Key Takeaways

- Studying the brains of cadavers can lead to discoveries about brain structure, but these studies are limited due to the fact that the brain is no longer active.

- Lesion studies are informative about the effects of lesions on different brain regions.

- Electrophysiological recording may be used in animals to directly measure brain activity.

- Measures of electrical activity in the brain, such as electroencephalography (EEG), are used to assess brain-wave patterns and activity.

- Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) measures blood flow in the brain during different activities, providing information about the activity of neurons and thus the functions of brain regions.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is used to temporarily and safely deactivate a small brain region, with the goal of testing the causal effects of the deactivation on behavior.

References

Chen, Z., Williams, K. D., Fitness, J., & Newton, N. C. (2008). When hurt will not heal: Exploring the capacity to relive social and physical pain. Psychological Science, 19(8), 789–795.

Damasio, H., Grabowski, T., Frank, R., Galaburda, A. M., Damasio, A. R., Cacioppo, J. T., & Berntson, G. G. (2005). The return of Phineas Gage: Clues about the brain from the skull of a famous patient. In Social neuroscience: Key readings (pp. 21–28). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Diamond, M. C. (1999). Why Einstein’s brain? New Horizons for Learning.

Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302(5643), 290–292.

Kalbe, E., Schlegel, M. , Sack, A. T., Nowak, D. A., Dafotakis, M., Bangard, C.,…Kessler, J. (2010). Dissociating cognitive from affective theory of mind: A TMS study. Cortex: A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior, 46(6), 769–780.

, Sack, A. T., Nowak, D. A., Dafotakis, M., Bangard, C.,…Kessler, J. (2010). Dissociating cognitive from affective theory of mind: A TMS study. Cortex: A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior, 46(6), 769–780.

Kanwisher, N. (2000). Domain specificity in face perception. Nature Neuroscience, 3(8), 759–763.

Koenigs, M., Young, L., Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., Cushman, F., Hauser, M., & Damasio, A. (2007). Damage to the prefontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgments. Nature, 446(7138), 908–911.

Kotowicz, Z. (2007). The strange case of Phineas Gage. History of the Human Sciences, 20(1), 115–131.

Macmillan, M. (2000). An odd kind of fame: Stories of Phineas Gage. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Miller, G. (2008). The roots of morality. Science, 320, 734–737.

Van den Eynde, F., Claudino, A. M., Mogg, A., Horrell, L., Stahl, D.,…Schmidt, U. (2010). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces cue-induced food craving in bulimic disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 67(8), 793–795.

Biological Psychiatry, 67(8), 793–795.

Wesselmann, E. D., Bagg, D., & Williams, K. D. (2009). “I feel your pain”: The effects of observing ostracism on the ostracism detection system. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(6), 1308–1311.

Young, L., Camprodon, J. A., Hauser, M., Pascual-Leone, A., & Saxe, R. (2010). Disruption of the right temporoparietal junction with transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces the role of beliefs in moral judgments. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(15), 6753–6758.

How is the study of the brain?

The information in this section should not be used for self-diagnosis or self-treatment. In case of pain or other exacerbation of the disease, only the attending physician should prescribe diagnostic tests. For diagnosis and proper treatment, you should contact your doctor.

The brain is the most complex organ of the human body, because it connects all body systems. That is why the study of the brain is carried out using the most high-tech diagnostic devices.

That is why the study of the brain is carried out using the most high-tech diagnostic devices.

When to examine the brain

With the help of high-precision brain diagnostics, the doctor can diagnose or track the development of the disease. A neurologist, phlebologist and traumatologist can prescribe examinations of the brain or blood vessels due to the following complaints:

- headaches of unclear nature;

- head injuries;

- loss of sensation in the limbs, decreased vision, hearing and smell;

- lack of coordination, constant general weakness;

- convulsions.

If you suspect a stroke and diagnose tumors and epilepsy, tests are simply necessary - with their help, you can detect neoplasms, blockages and ruptures of blood vessels, hematomas, foreign bodies and non-functioning areas of the brain. Since pathologies in different parts of the head can cause completely different symptoms, doctors very often prescribe brain tests.

Types of brain examinations

The most common and informative types of brain examinations are computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. They allow you to get high-quality images of the brain in several projections, which helps in the diagnosis of any disease.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain

An absolutely safe method of examination, which has practically no contraindications. It is dangerous only for patients with pacemakers and metal implants in the body - the magnetic field of the tomograph can displace or heat metal objects and disrupt the operation of mechanisms.

On the resulting image, you can see dense and soft tissues, blood vessels and neoplasms. An MRI image is taken in several projections at the required depth, so the doctor can assess the state of any part of the brain.

Remove all metal objects and accessories before the procedure. In order not to undress before the examination, you can simply put on clothes without zippers and metal buttons.

For an MRI, the patient lies down on a couch. The laboratory assistant can give you headphones that protect against very loud sounds during the procedure. The patient is then placed inside the tomograph. It is necessary to remain still, as changing the position of the body will distort the image. The brain examination usually takes no more than half an hour. At the request of the patient, if he feels uncomfortable, the procedure can be stopped or suspended without harm to the information content of the study.

Computed tomography of the brain

Works on the basis of X-rays, therefore it is not recommended for children, pregnant and lactating women. But for all other patients, it is absolutely safe.

After a CT scan, you can get a 3D image of the brain. It is of the same quality as an MRI: it shows all the structures of the brain and blood vessels. Therefore, the choice between two types of tomography is based only on the existing contraindications.

Metal objects will also need to be removed: they are not dangerous, as in MRI, but they interfere with the passage of radiation. If this is not done, part of the image will be lost.

If this is not done, part of the image will be lost.

A significant advantage of computed tomography is that small changes in body position will not affect the result. Otherwise, the procedure differs little from an MRI. The patient on the couch is placed in the tomograph and observed during the procedure. The study lasts no more than 15-20 minutes and can be stopped at any time at the request of the patient.

CT scans can be done with a contrast agent to get more detailed and clear pictures. To do this, first a routine examination is carried out, and then a dye is injected intravenously into the patient. After that, the procedure continues for several minutes.

Other types of research

In addition to tomography, several more types of diagnostics are used to examine the brain:

- Electroencephalography (EEG) registers fluctuations in electrical impulses in the brain. Electrodes are attached to the patient's head, through which the biocurrents of the brain are fixed and displayed on paper or screen.

This study can help with delayed mental and speech development, epilepsy and trauma: thanks to it, inactive areas of the brain can be identified.

This study can help with delayed mental and speech development, epilepsy and trauma: thanks to it, inactive areas of the brain can be identified. - Craniography is an x-ray of the skull in two projections. Very weak radiation is used so as not to harm the patient. Such images will help to identify congenital structural defects and injuries of the skull bones.

- Neurosonography is an ultrasound examination of the brain in children from birth to the moment of fontanel closure. It is not as informative as tomography and X-ray, but is one of the few safe ways to examine newborns.

- Electroneuromyography checks the transmission of impulses along the nerves. To do this, electrodes are applied to the skin in the area of nerve localization, through which an electrical impulse is launched. According to the intensity of muscle contraction, the doctor will determine the performance of the nerves.

How is the vascular examination performed?

Angiography and ultrasound are used to examine the veins and arteries of the brain. Both options are safe, informative and have a minimum of contraindications.

Both options are safe, informative and have a minimum of contraindications.

Magnetic resonance angiography

Gives the best result in the study of small vessels and nerve trunks. During the study, the doctor will receive a picture of all the vessels in your brain. This will help diagnose micro-strokes and thromboses that are not visible on a regular MRI image of the head. It is often prescribed by surgeons after operations to control the condition.

MRA is performed in the same way as conventional magnetic resonance imaging, and has the same features and contraindications. Before the procedure, all metal objects must be removed, and during the operation of the tomograph, you can not move your head. Often, for correct diagnosis, angiography should be combined with MRI of the brain - this will allow a more detailed examination of the area of the pathology.

Computed angiography

CA of cerebral vessels is similar to computed tomography. As a result of the procedure, the doctor will receive a three-dimensional model of the vessels of the head. On the resulting image, you can see anomalies in the structure of veins and arteries, atherosclerosis, narrowing of the lumen of blood vessels and neoplasms.

On the resulting image, you can see anomalies in the structure of veins and arteries, atherosclerosis, narrowing of the lumen of blood vessels and neoplasms.

The doctor may prescribe this examination both for preparation for surgery and for monitoring after treatment. In addition, this type of examination is an option for patients who, due to contraindications, cannot undergo MRA.

Computed angiography can use a contrast medium to better visualize damaged areas. Contraindications for the procedure are the same as for CT: pregnancy and childhood.

Doppler ultrasound

An ultrasound transducer is placed on the thinnest bones of the skull. With the help of ultrasound, you can find a narrowing or thrombosis in the vessels of the brain, measure the speed of blood movement, detect aneurysms and areas with a changed direction of blood flow. The image is displayed on the monitor screen, and, if necessary, you can print the desired frame.

With the help of ultrasound, it is possible to examine both the vessels inside the skull and in the neck if blood flow in the brain has been disturbed due to them. The method has no contraindications, it is absolutely safe for patients of any age. UD does not require additional preparation or examinations, however, before the procedure, it is better to refrain from taking products and drugs that affect vascular tone.

The method has no contraindications, it is absolutely safe for patients of any age. UD does not require additional preparation or examinations, however, before the procedure, it is better to refrain from taking products and drugs that affect vascular tone.

What determines the choice of study?

The most common methods of brain research: MRI, CT and ultrasound. They are quite informative for the vast majority of possible diseases. If you do not know your diagnosis and want to come to the doctor with ready-made tests, the best option would be an MRI or CT scan. They provide enough information on the state of both the brain itself and bone tissues; large vessels can be distinguished on them.

For head injuries, craniogra- phy should be performed first. It will provide sufficient information about the integrity of the skull, and if foreign bodies have not entered the brain, other types of diagnostics will not be needed. If the injury is more serious, with internal bleeding and brain damage, then you will definitely have a tomography.

If the doctor has prescribed you an examination of cerebral vessels, then you should focus on your own contraindications, as well as the availability of studies. Both tomography and ultrasound show equally good results.

The decision of the doctor remains the decisive factor in the selection of examinations. Serious diagnostics is carried out only in the direction of the doctor. It is quite possible that he will prescribe you several procedures at once for a more complete examination and accurate diagnosis.

It will also be interesting:

- What to do if your head hurts all the time

- Why does the back of the head hurt

- Signs of a brain tumor

References

- Zenkov L.R. Clinical electroencephalography (with elements of epileptology). A guide for doctors / L.R. Zenkov. – 5th ed. – M.: MEDpressinform, 2012. – 356 p.

- Kulaichev A.P. Computer electrophysiology. 3rd ed., revised. and additional M.

: Publishing House of Moscow State University, 2002. -380 p.

: Publishing House of Moscow State University, 2002. -380 p. - Sheftell, F.D. Post-traumatic headache: Emphasis on chronic types following mild closed head injury / F.D. Sheftell, S.J. Tepper, C.L. Lay [et al.] // Neurol. sci. - 2007. Vol. 28. – P. S203-S207

- Obermann, M. Post-traumatic headache // M. Obermann, D. Holle, Z. Katsarava // Expert Rev. neurother. - 2009. - Vol. 9. - P. 1361-1370.

- Guzhov V.I., Vinokurov A.A. METHODS FOR STUDYING THE STRUCTURE AND FUNCTIONAL STATE OF THE BRAIN // Automation and software engineering, 2014. link

- Zhumakova T.A., Ryspekova Sh.O., Zhunistaev D.D., Churukova N.M., Isaeva A.M., Alimkul I.O. SECRETS OF THE HUMAN BRAIN // International Journal of Applied and Fundamental Research. – 2017. link

All about brain examination methods

Examination of the brain is a difficult diagnostic task for any specialist. It is securely hidden under the cranial plates, so in most cases it is available only for non-invasive diagnostic methods. Physicians have the following ways to evaluate various aspects of brain anatomy and function:

Physicians have the following ways to evaluate various aspects of brain anatomy and function:

- Craniography

- Electroencephalography

- Echoencephalography

- Electroneuromyography

- Neurosonography

- MRI of the brain

- CT scan of the brain

- Positron emission tomography

Contents

Types of examination of the brain

MRI at night

This method of examining the brain is usually used only for newborns and infants up to a year old, until their fontanel closes.

This method of examining the brain is usually used only for newborns and infants up to a year old, until their fontanel closes.  The principle of operation of the CT machine is based on the ability of x-rays to pass through tissues of different density at different speeds. In the course of such a diagnosis, doctors can obtain data on the state of the cranial plates and the substance of the brain. CT of the brain visualizes bone structures very well, but is inferior to MRI of the head in informative value in the differential diagnosis of diseases of the brain itself. Most often, this examination of the brain is prescribed for traumatic brain injuries in order to quickly assess the consequences of a traumatic injury.

The principle of operation of the CT machine is based on the ability of x-rays to pass through tissues of different density at different speeds. In the course of such a diagnosis, doctors can obtain data on the state of the cranial plates and the substance of the brain. CT of the brain visualizes bone structures very well, but is inferior to MRI of the head in informative value in the differential diagnosis of diseases of the brain itself. Most often, this examination of the brain is prescribed for traumatic brain injuries in order to quickly assess the consequences of a traumatic injury.  This is a high-tech examination that lasts from half an hour to an hour. It should be done according to the doctor's prescription for oncological diagnoses.

This is a high-tech examination that lasts from half an hour to an hour. It should be done according to the doctor's prescription for oncological diagnoses.