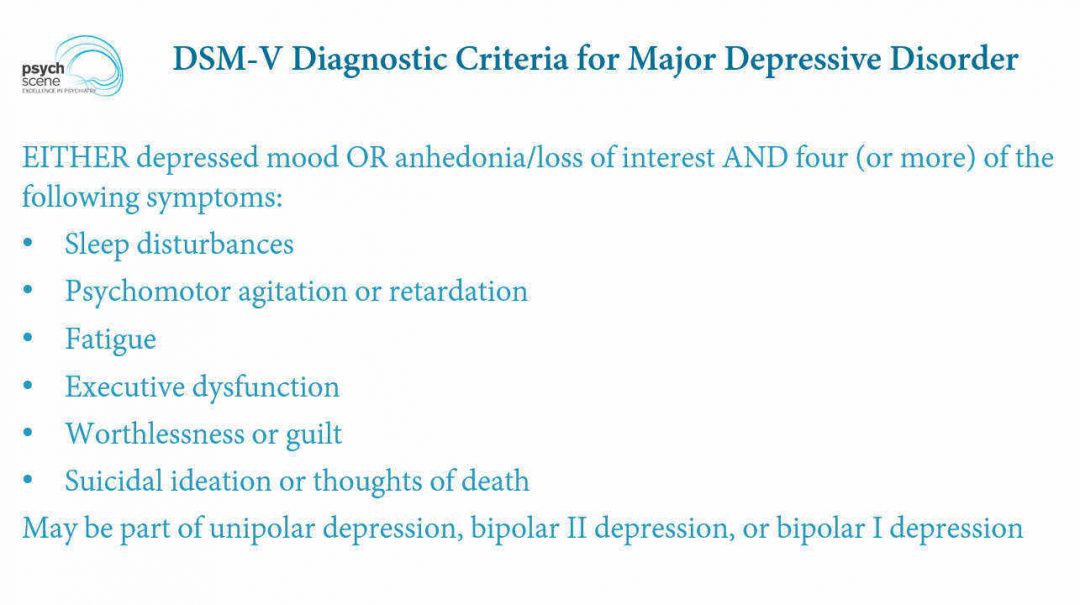

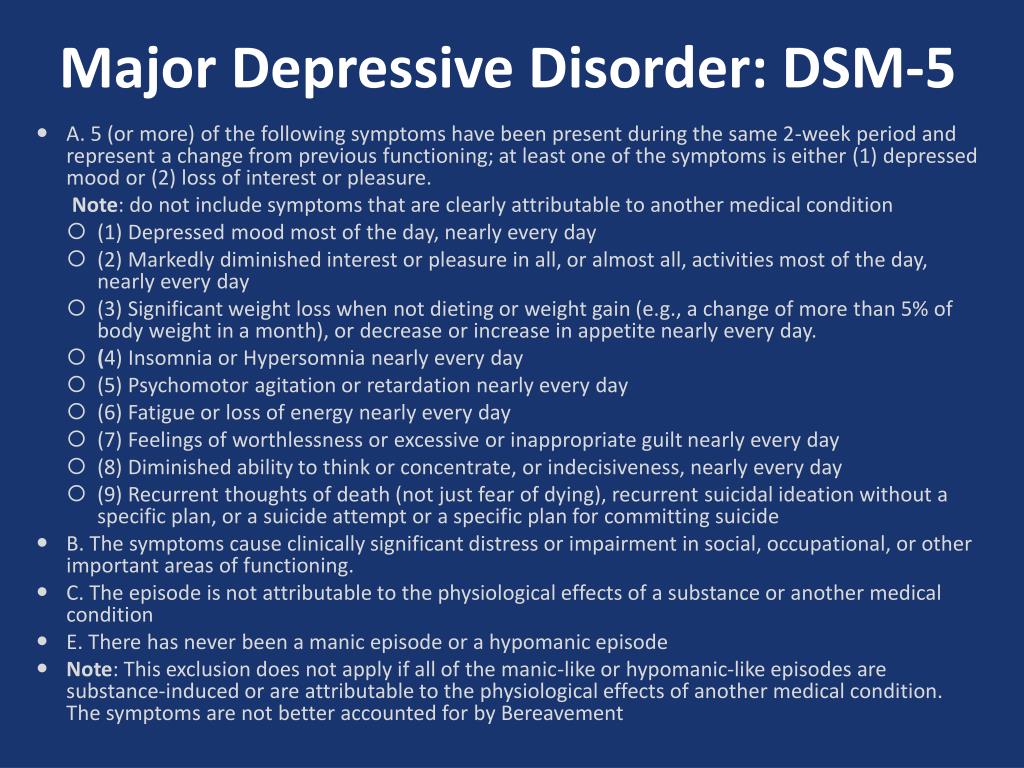

Major depression diagnosis dsm 5

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

HomeWelcome to the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator, a confidential and anonymous source of information for persons seeking treatment facilities in the United States or U.S. Territories for substance use/addiction and/or mental health problems.

PLEASE NOTE: Your personal information and the search criteria you enter into the Locator is secure and anonymous. SAMHSA does not collect or maintain any information you provide.

Please enter a valid location.

please type your address

-

FindTreatment.

gov

gov Millions of Americans have a substance use disorder. Find a treatment facility near you.

-

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

Call or text 988

Free and confidential support for people in distress, 24/7.

-

National Helpline

1-800-662-HELP (4357)

Treatment referral and information, 24/7.

-

Disaster Distress Helpline

1-800-985-5990

Immediate crisis counseling related to disasters, 24/7.

- Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Finding Treatment

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Facility Directors

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Other Locator Functionalities

- Download Search ResultsDownload Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Print Search ResultsPrint Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). - Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). Find programs providing methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

The Locator is authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act (Public Law 114-255, Section 9006; 42 U.S.C. 290bb-36d). SAMHSA endeavors to keep the Locator current. All information in the Locator is updated annually from facility responses to SAMHSA’s National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N-SUMHSS). New facilities that have completed an abbreviated survey and met all the qualifications are added monthly. Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Comorbidity of depression and disorders of the non-affective schizophrenia spectrum: a clinical and epidemiological study EDIP

The problem of the relationship between depression and disorders of the non-affective range has attracted the attention of researchers since the construction of the first detailed systematics of mental illness; At the same time, not only the delimitation of affective pathology was initially assumed, but also an analysis of its connection with other mental disorders.

The beginning of the discussion on this problem, associated with the development of the doctrine of a "single psychosis", dates back to the middle of the 19th century. So, W. Griesinger [1], developing the teachings of C. Jacobi [2] about primary and secondary forms of psychosis, being an adherent of the concept of "single psychosis", singled out gradations (or steps according to H. Schüle [3]) of the development of mental illness, placing depression into the "primary" group of psychoses, determined by the dominance of "mental disturbances" (affects). The latter, according to the author, “for the most part precede the states of the second group” (intellectual or volitional disorders, often determined by the predominance of mental weakness), which “usually constitute the consequence and outcome of the former in all cases where the brain disease has not been cured.” Accordingly, according to Yu.V. Cannabih [4], while we are talking about periods or phases of one disease process, the first stage of which are various forms of affective disorders.

So, W. Griesinger [1], developing the teachings of C. Jacobi [2] about primary and secondary forms of psychosis, being an adherent of the concept of "single psychosis", singled out gradations (or steps according to H. Schüle [3]) of the development of mental illness, placing depression into the "primary" group of psychoses, determined by the dominance of "mental disturbances" (affects). The latter, according to the author, “for the most part precede the states of the second group” (intellectual or volitional disorders, often determined by the predominance of mental weakness), which “usually constitute the consequence and outcome of the former in all cases where the brain disease has not been cured.” Accordingly, according to Yu.V. Cannabih [4], while we are talking about periods or phases of one disease process, the first stage of which are various forms of affective disorders.

Following W. Griesinger [1] and H. Schüle [3], a systematic system consisting of three groups of psychopathological syndromes, reflecting the limitation of depression from pathological conditions with a greater depth of damage to mental activity (schizophreniform, hallucinatory, organic, dementia, etc. ), developed by E. Kraepelin [5] 1 .

), developed by E. Kraepelin [5] 1 .

The idea of a consistent gradation of the severity of mental disorders was further developed in the works of A.V. Snezhnevsky [6, 7] about registers, which are a scale of positive psychopathological syndromes ranging from emotional-hyperesthetic disorders (neurasthenia) to psycho-organic ones. Actually affective pathology (depression, mania) occupies register II after the most mild neurotic disorders (register I). At the same time, A.V. Snezhnevsky, following E. Kraepelin, connects this or that distribution of syndromes and the sequence of their change with the nosological nature of suffering 2 .

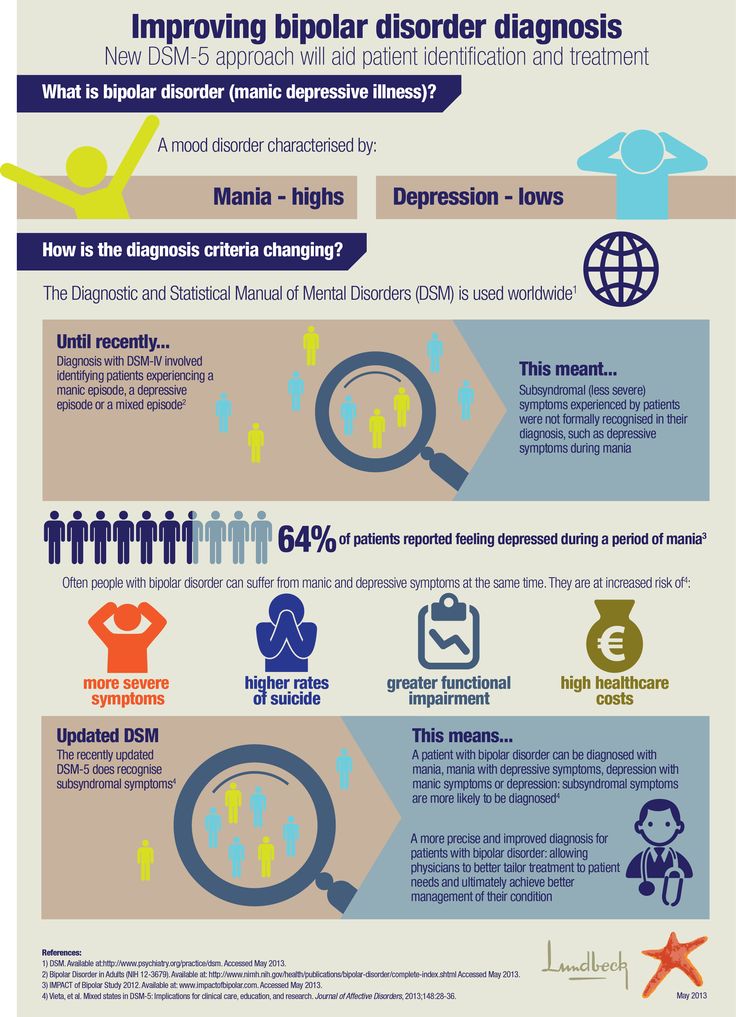

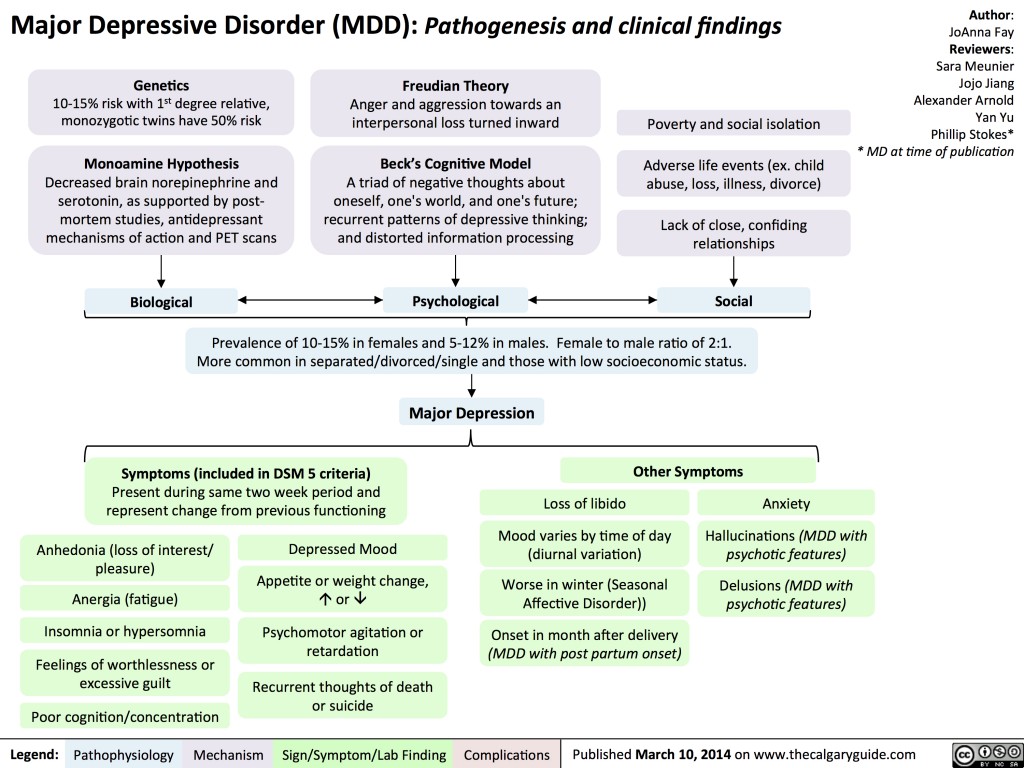

However, at the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries. in connection with the revision of the paradigm of E. Kraepelin, who divided endogenous diseases into affective and schizophrenic psychoses, the results of a number of studies are published, which in a number of positions are not comparable with the regularities of the ratio of depressive and non-affective syndromes established by E. Kraepelin and his followers. At the same time, depressive syndromes, which, within the system of registers E. Kraepelin—A.V. Snezhnevsky act as manifestations of the lightest psychopathological registers, along with this, in accordance with such an alternative conceptualization, they reveal a second property - a tendency to integrate with syndromes that reflect a severe lesion of mental activity - psychopathological manifestations of a progredient endogenous process. So, in accordance with the data of publications by M. Birchwood et al. [8-10], which found support in the studies of D. Freeman et al. [11], G.E. Mazo and N.G. Neznanov [12], affective (depressive) symptom complexes determine not only the clinical picture of affective diseases, but represent basic disorders that participate as contiguous hallucinatory-delusional syndromes in the formation of the psychopathological space of both prodromes and manifest psychoses within schizophrenia

. At the same time, if at the initial stages of the disease, affective and procedural disorders coexist, as it were, in parallel, then as the severity of psychosis increases, they acquire features of clinical unity.

Kraepelin and his followers. At the same time, depressive syndromes, which, within the system of registers E. Kraepelin—A.V. Snezhnevsky act as manifestations of the lightest psychopathological registers, along with this, in accordance with such an alternative conceptualization, they reveal a second property - a tendency to integrate with syndromes that reflect a severe lesion of mental activity - psychopathological manifestations of a progredient endogenous process. So, in accordance with the data of publications by M. Birchwood et al. [8-10], which found support in the studies of D. Freeman et al. [11], G.E. Mazo and N.G. Neznanov [12], affective (depressive) symptom complexes determine not only the clinical picture of affective diseases, but represent basic disorders that participate as contiguous hallucinatory-delusional syndromes in the formation of the psychopathological space of both prodromes and manifest psychoses within schizophrenia

. At the same time, if at the initial stages of the disease, affective and procedural disorders coexist, as it were, in parallel, then as the severity of psychosis increases, they acquire features of clinical unity. According to M. Birchwood [10], a common space of "affect-symptoms" is being formed, within which the proportion of affective disorders increases in proportion to the severity and duration of schizophrenia.

According to M. Birchwood [10], a common space of "affect-symptoms" is being formed, within which the proportion of affective disorders increases in proportion to the severity and duration of schizophrenia.

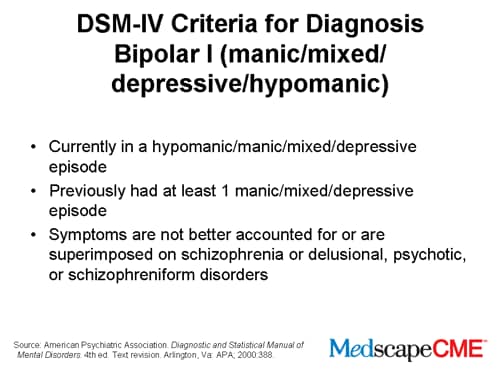

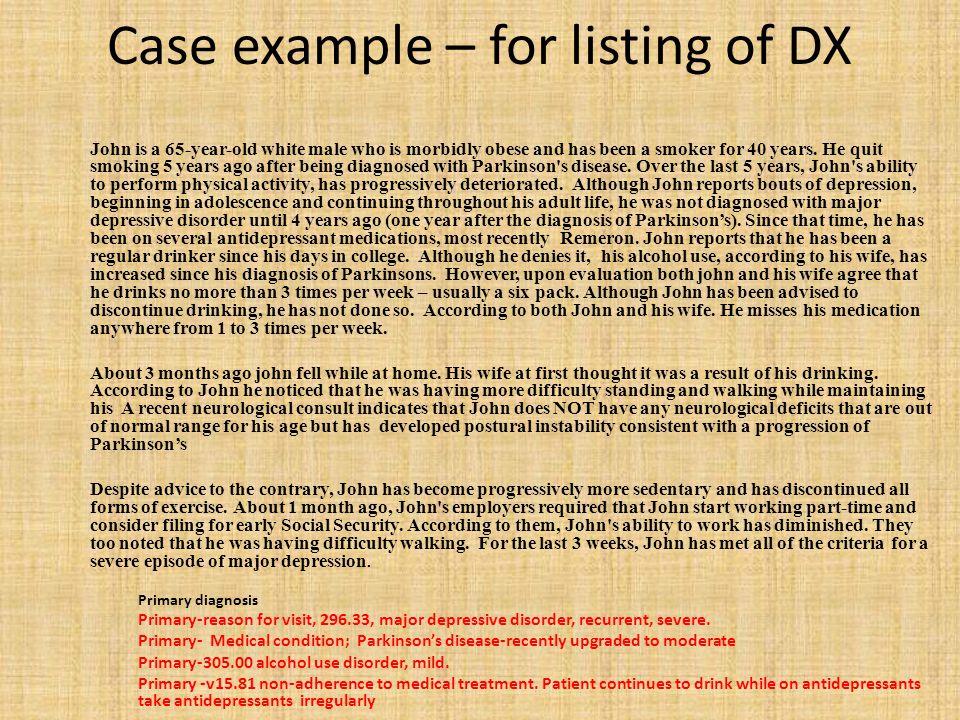

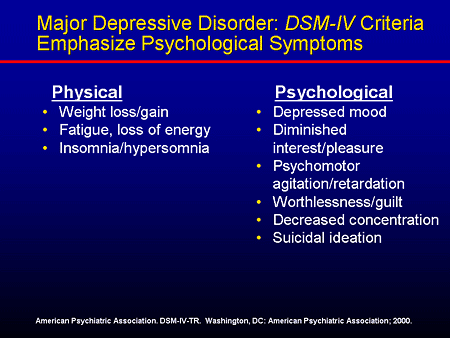

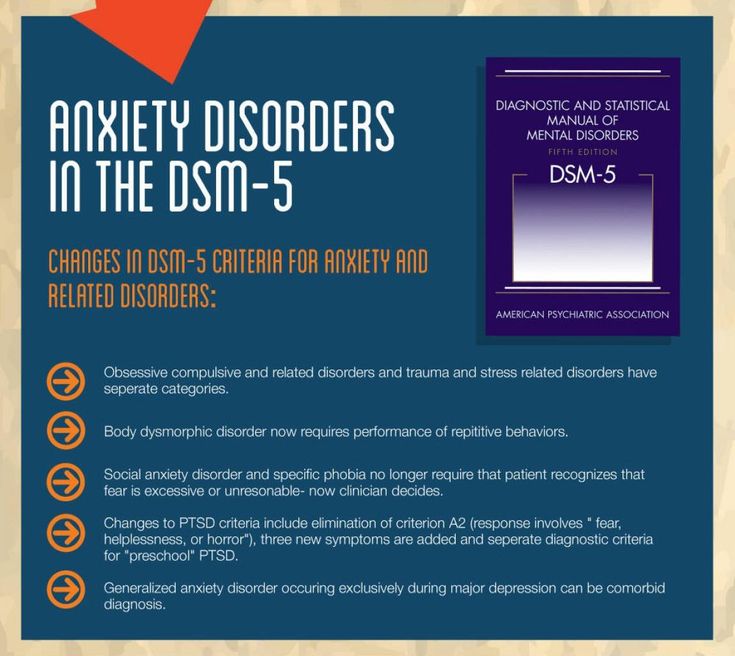

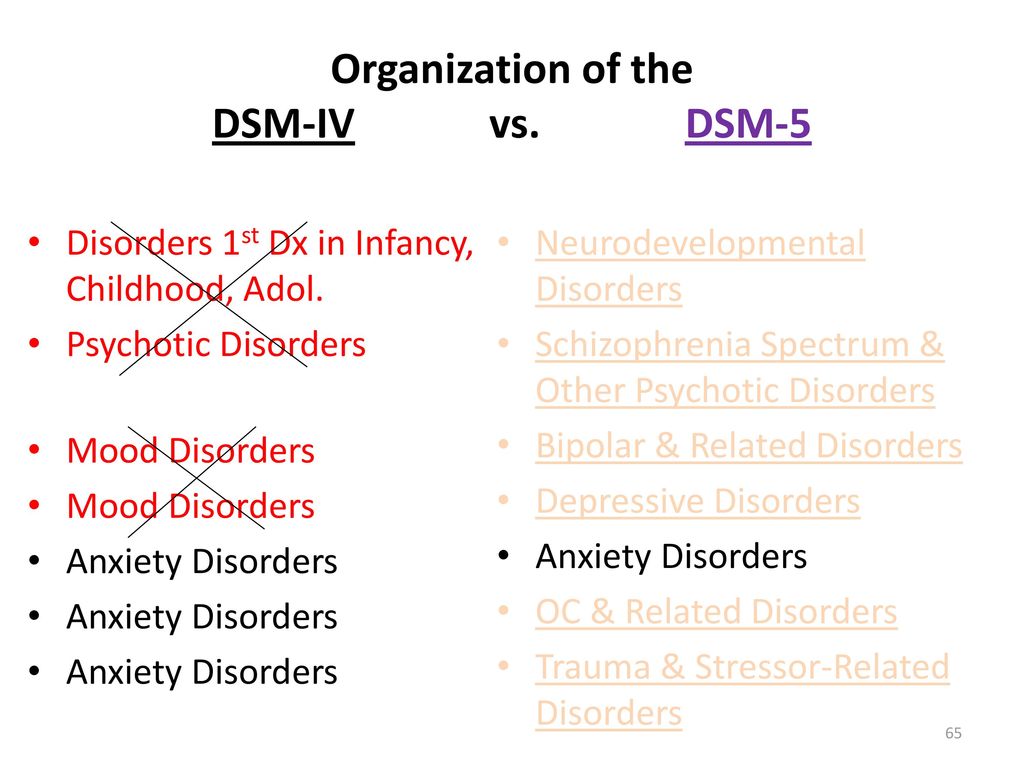

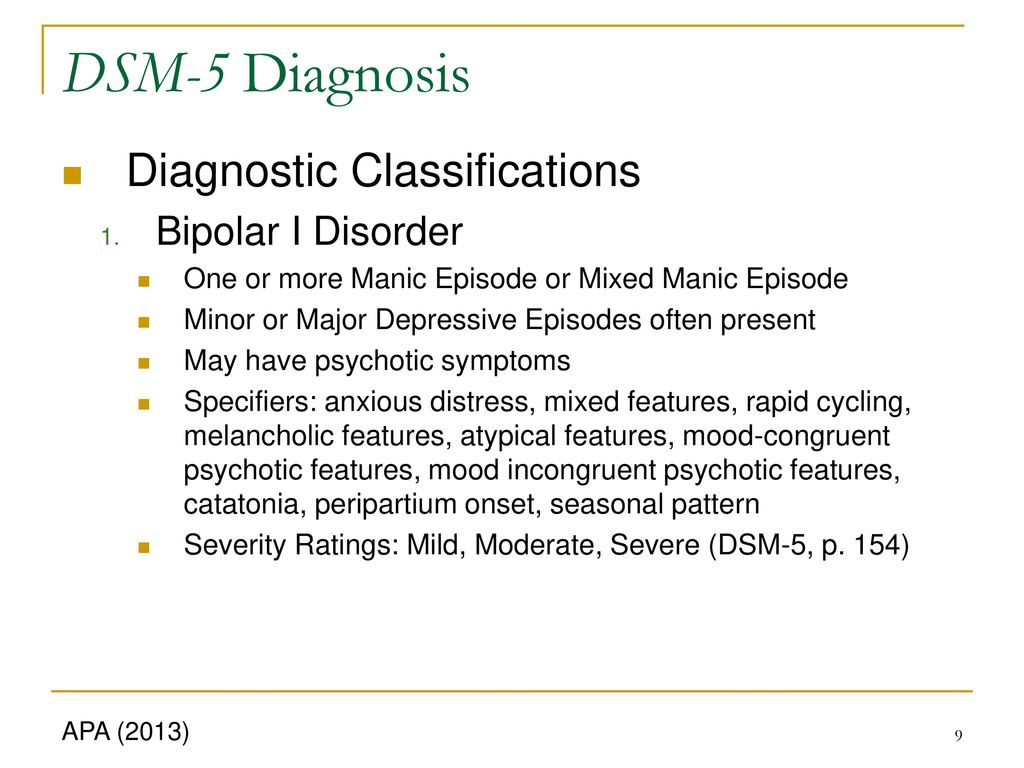

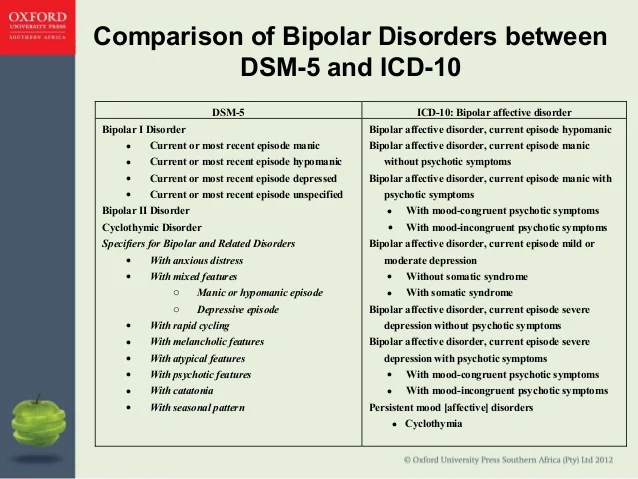

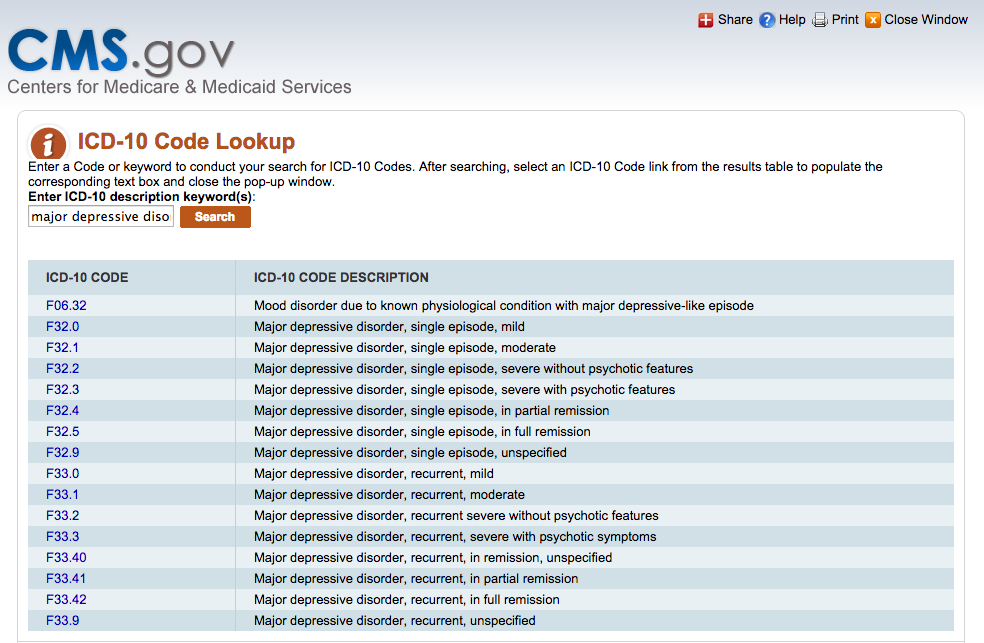

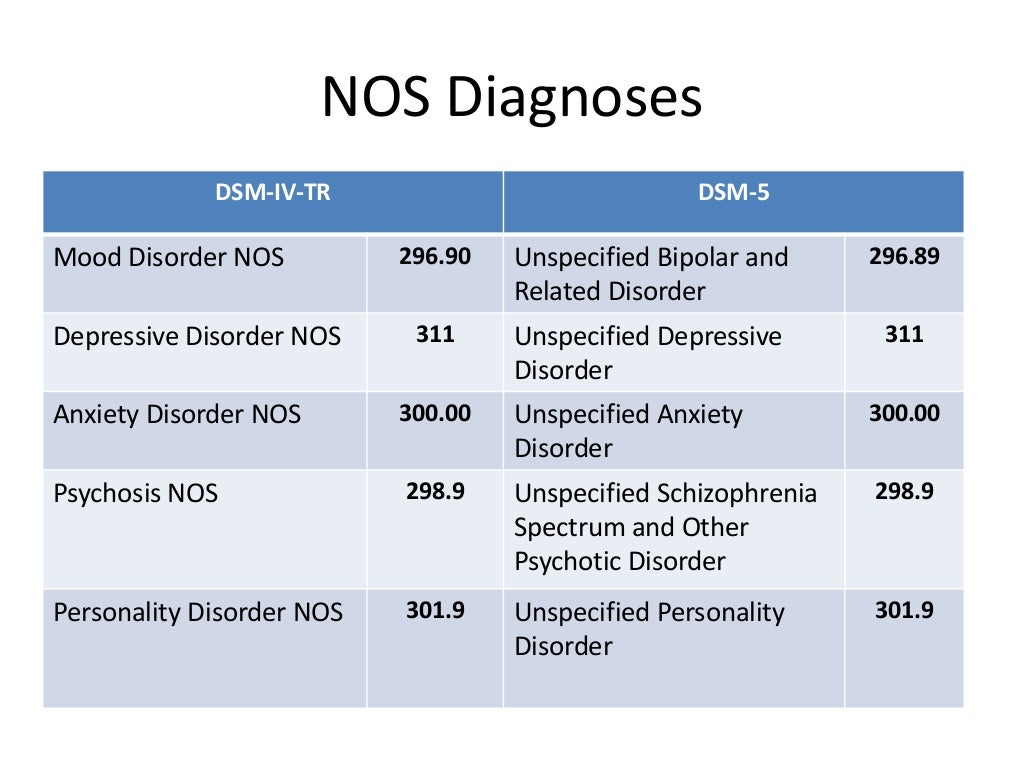

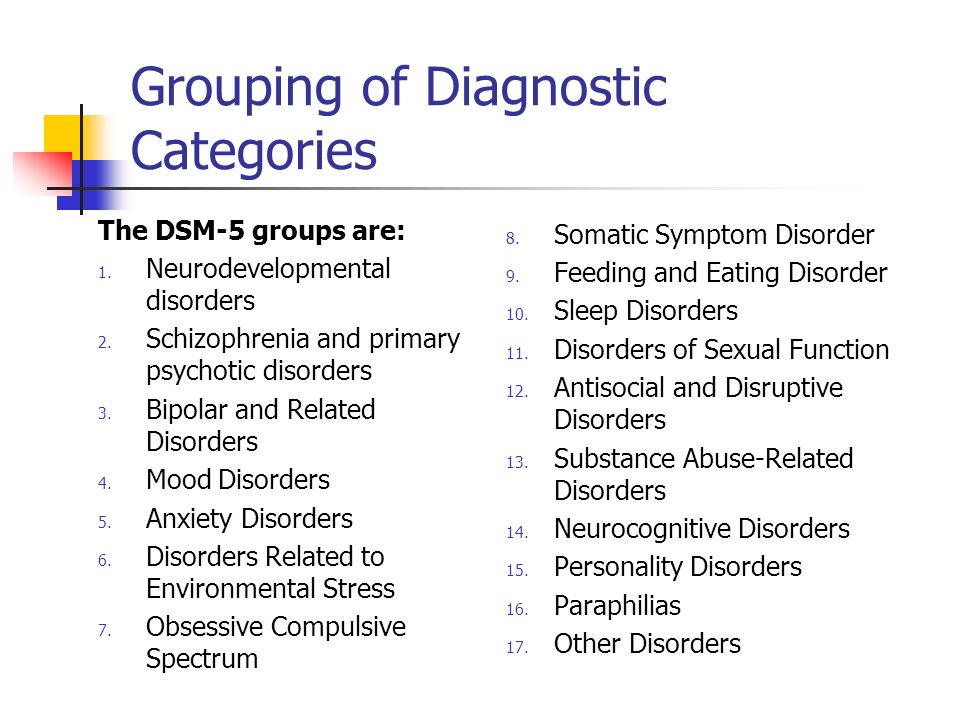

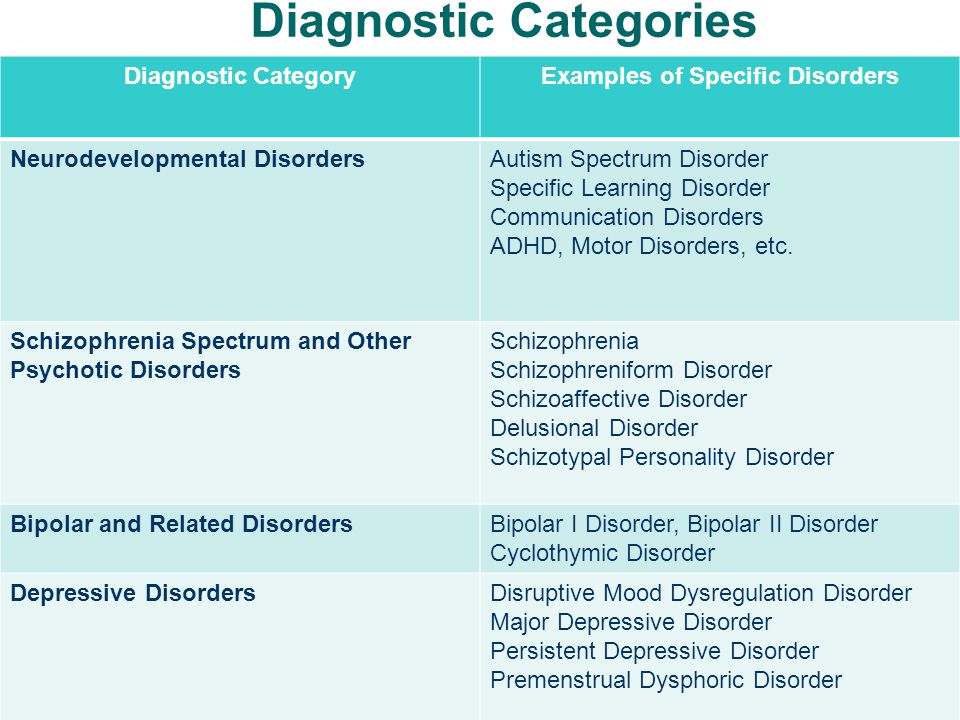

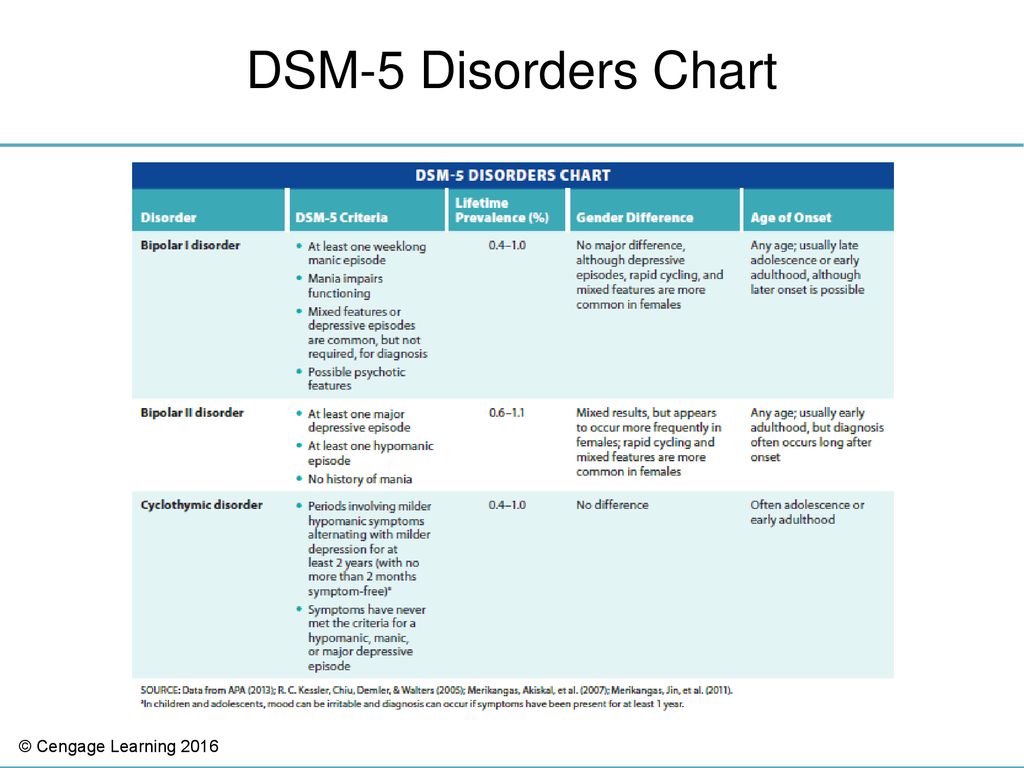

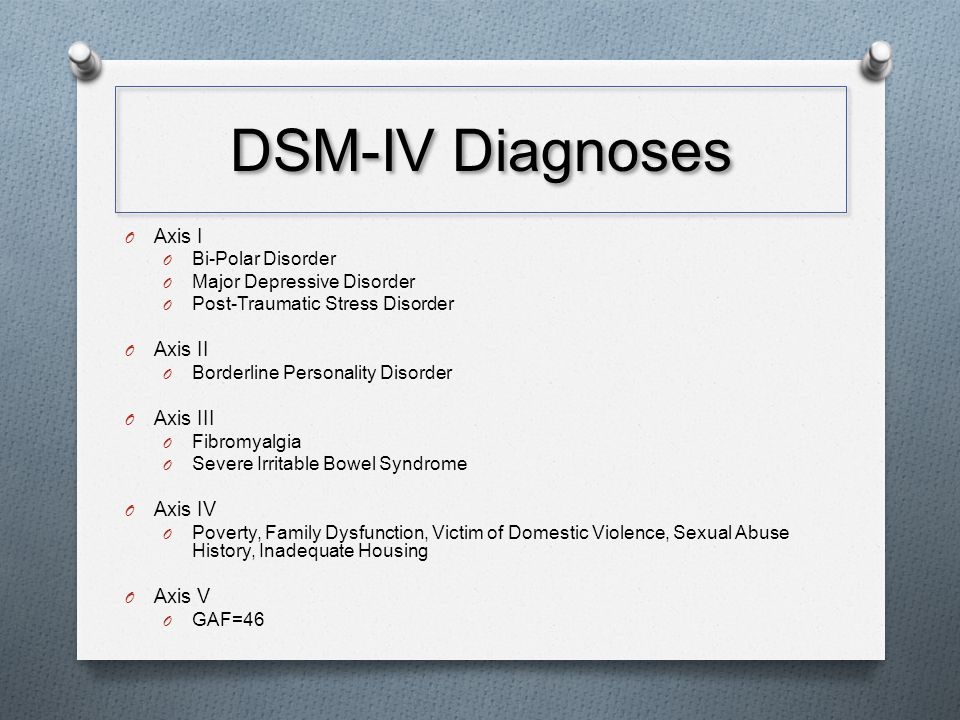

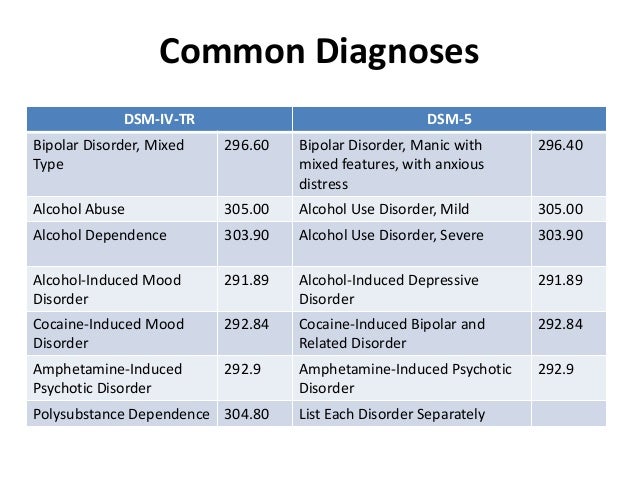

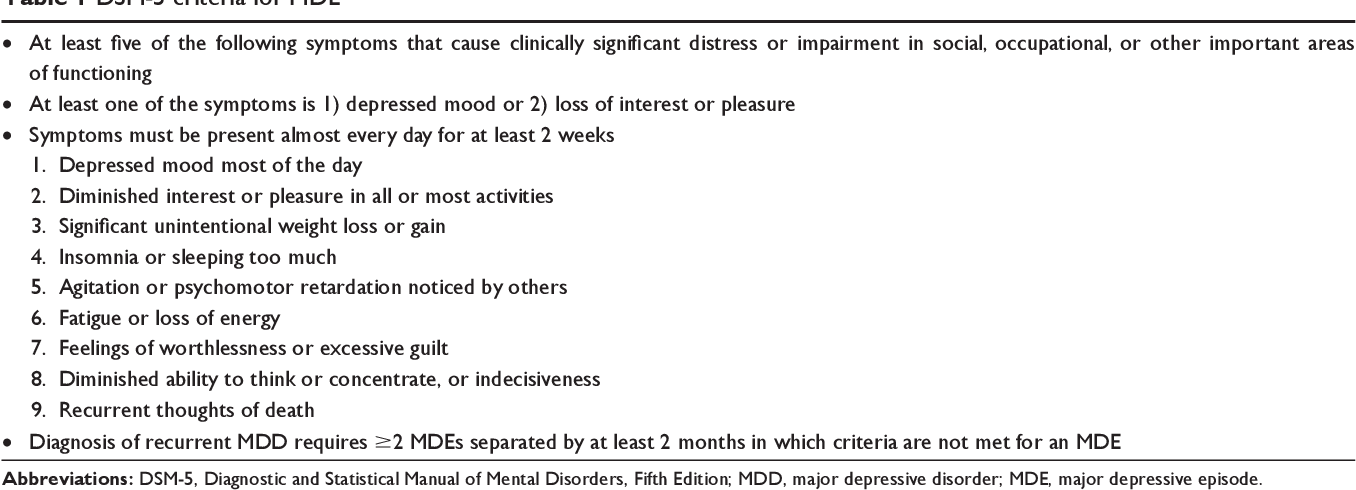

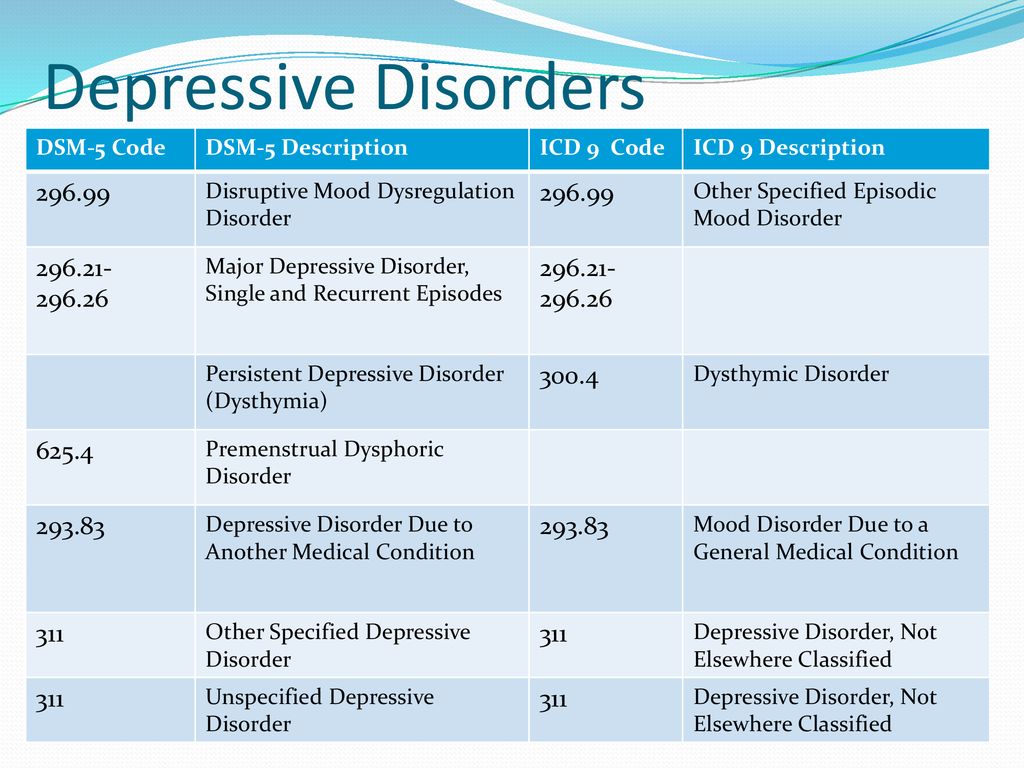

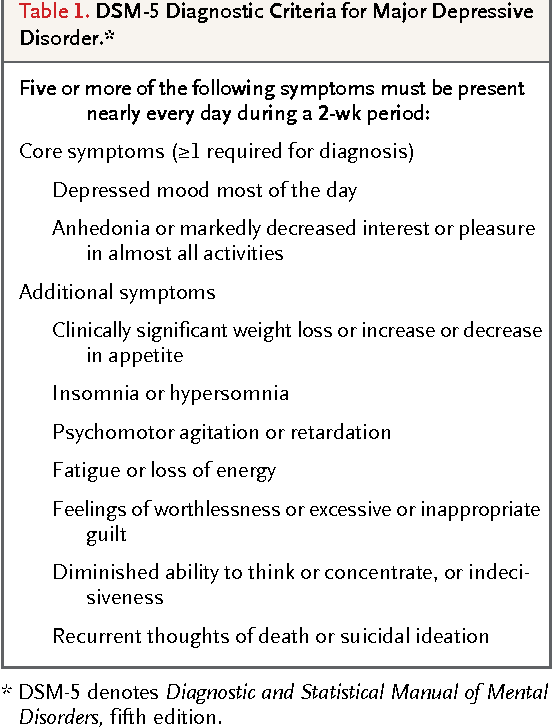

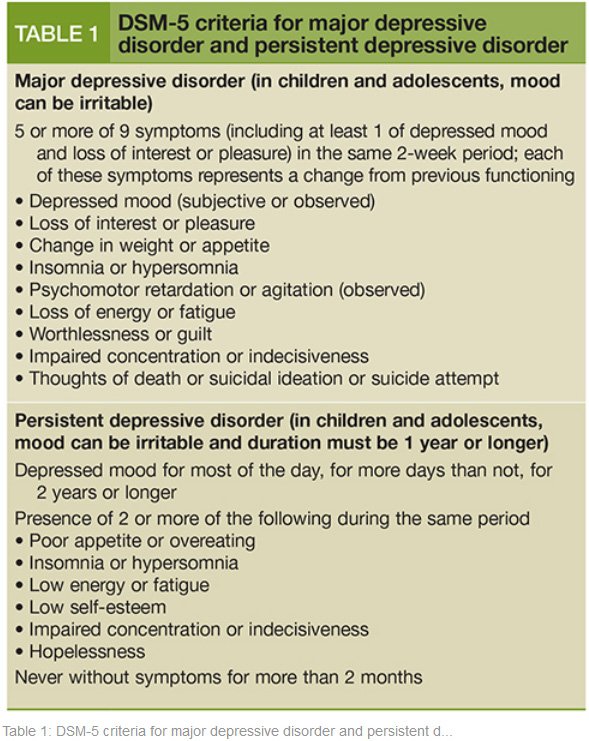

Accordingly, in a number of currently existing concepts of the relationship between depression and other psychopathological disorders, one has to state contradictions. The latter are primarily associated with differences in the assessment of the nosological nature of endogenous mental disorders. On the one hand, the analysis of the problem under consideration is carried out from the standpoint of a clear nosological distinction between affective syndromes that act within the framework of manic-depressive psychosis (and, accordingly, recurrent affective and bipolar disorders) and syndromes related to schizophrenia registers [5-7, 13, 14], and on the other hand, in the light of criticism of the nosological dichotomy of endogenous diseases, from the standpoint of leveling the division proposed by E. Kraepelin between affective and progressive schizocaric disorders [8-10, 15-17]. Opponents of the dichotomy (along with others) cite the results of numerous modern clinical and epidemiological studies as appropriate arguments. Such works were carried out from the standpoint of the concept of comorbidity - the qualification of individual clinical categories is carried out outside the nosological paradigm as relatively independent psychopathological formations (disorders / syndromes), delimited on a clinical and statistical basis (as formations with the most frequent constellation of individual symptoms). At the same time, extensive information has been published on the association of depression and a wide range of non-affective disorders identified according to the ICD-10 and / or DSM criteria (DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR, DSM-5), i.e. outside the concept of registries ranked by severity. In such studies, as a rule, one of two methodological approaches is implemented: either the authors, when studying certain aspects of non-affective pathology (asthenia, somatoform disorder, anxiety-phobic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, psychosis, schizophrenia), give the frequency / prevalence of comorbid depression , or vice versa - in samples of patients with depression, the frequency of comorbid non-affective disorders is determined.

Kraepelin between affective and progressive schizocaric disorders [8-10, 15-17]. Opponents of the dichotomy (along with others) cite the results of numerous modern clinical and epidemiological studies as appropriate arguments. Such works were carried out from the standpoint of the concept of comorbidity - the qualification of individual clinical categories is carried out outside the nosological paradigm as relatively independent psychopathological formations (disorders / syndromes), delimited on a clinical and statistical basis (as formations with the most frequent constellation of individual symptoms). At the same time, extensive information has been published on the association of depression and a wide range of non-affective disorders identified according to the ICD-10 and / or DSM criteria (DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR, DSM-5), i.e. outside the concept of registries ranked by severity. In such studies, as a rule, one of two methodological approaches is implemented: either the authors, when studying certain aspects of non-affective pathology (asthenia, somatoform disorder, anxiety-phobic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, psychosis, schizophrenia), give the frequency / prevalence of comorbid depression , or vice versa - in samples of patients with depression, the frequency of comorbid non-affective disorders is determined. According to available information, the incidence of comorbidity, regardless of the approach chosen by the authors, is quite high, although it is characterized by a significant scatter of indicators. In a number of modern publications, along with (or instead of) the frequencies of comorbidity, the odds ratio indicator (OR, OR) is given, reflecting the ratio of the probability (chance) of developing a non-affective disease in the case of a history of depression to the chances in favor of developing the disease in its absence.

According to available information, the incidence of comorbidity, regardless of the approach chosen by the authors, is quite high, although it is characterized by a significant scatter of indicators. In a number of modern publications, along with (or instead of) the frequencies of comorbidity, the odds ratio indicator (OR, OR) is given, reflecting the ratio of the probability (chance) of developing a non-affective disease in the case of a history of depression to the chances in favor of developing the disease in its absence.

In emotional-hyperesthetic disorders (asthenia, neurasthenia) the frequency of comorbid depression is estimated at 53-79% [18, 19]. At the same time, in patients with depression, neurasthenia is recorded in 22.9% of cases [19]. In turn, according to large cohort and twin studies, life-long depression increases the chance of developing neurasthenia by 4.5 times (OR = 4.5, 95% CI 2.5–7.9) [19], and the presence at least one depressive episode in history is significantly associated with indicators of asthenia - "abnormal fatigue" (OR = 3. 19, 95% CI 2.64–3.84) and “prolonged fatigue” (OR=6.47, 95% CI 3.36–12.47) at the time of the examination [20].

19, 95% CI 2.64–3.84) and “prolonged fatigue” (OR=6.47, 95% CI 3.36–12.47) at the time of the examination [20].

Studies of comorbidity depression and somatoform disorders are mainly represented by projects carried out in general medical practice [21]. Thus, 45.2% of patients diagnosed with major depression are also diagnosed with an undifferentiated somatoform disorder [21], and the frequency of all somatoform disorders in depression is 3.3 times higher than statistically expected [22]. At the same time, more than half of patients (54%) with disorders of the anxiety or depressive spectrum also meet the criteria for a somatoform disorder [22]. On the contrary, among patients with various somatoform disorders (somatoform pain disorder, undifferentiated somatoform disorder, hypochondriacal disorder, somatization disorder and somatoform dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system), the prevalence of moderate depression is 27%, and severe depression is 15% [23].

According to clinical and epidemiological data, the frequency of comorbidity depression and anxiety-phobic disorders is also high. For example, among elderly patients (over 60 years of age) with depression, 38.6% have comorbid anxiety spectrum disorders [24], among which social phobia (17.7%) and panic disorder with / without agoraphobia (14.9%) dominate ) with lower comorbidity rates for agoraphobia without panic disorder (10.3%) and generalized anxiety disorder (9,four%). In large epidemiological studies of the prevalence of anxiety disorders in depression [25], performed in a population regardless of age (1970 patients), their lifetime prevalence was even higher and amounted to 60.2%. At the same time, the frequency of individual anxiety spectrum disorders was at the level of 26.4% for generalized anxiety disorder, 15.0% for agoraphobia, 14.3% for social phobia, and 10.1% for panic disorder. In turn, in studies with "inverse design" (determination of the frequency of comorbid depression among patients with panic disorder ) the lifetime prevalence of depression is estimated at 50-60%. When assessed at the time of the survey, about 20% of patients with panic disorder also meet the criteria for depression [26]. In about 2/3 of cases, panic disorder manifests before depression, and in 1/3 of cases, on the contrary, depression develops earlier [27]. In patients with generalized anxiety disorder , depression is recorded in 12.1-62%, dysthymia - in 40% of cases [26, 28, 29]. The prevalence of major depression in patients with social phobia is also estimated in a wide range - 12-74.5% [26, 30-34] 3 . The presence of social phobia in history is considered by some authors as a predictor of the subsequent development of major depression [35, 39].

When assessed at the time of the survey, about 20% of patients with panic disorder also meet the criteria for depression [26]. In about 2/3 of cases, panic disorder manifests before depression, and in 1/3 of cases, on the contrary, depression develops earlier [27]. In patients with generalized anxiety disorder , depression is recorded in 12.1-62%, dysthymia - in 40% of cases [26, 28, 29]. The prevalence of major depression in patients with social phobia is also estimated in a wide range - 12-74.5% [26, 30-34] 3 . The presence of social phobia in history is considered by some authors as a predictor of the subsequent development of major depression [35, 39].

Current data on the prevalence of depression in obsessive-compulsive disorders are in the range of 38-70% [40-46].

Evidence for the comorbidity of depression with non-affective disorders is most clearly presented in large-scale population-based studies specifically designed to determine appropriate rates and risk values (ORs) or correlation coefficients ( - ). In particular, the analysis of data on the comorbidity of depression [47] showed that the closest relationship at the time of the survey was the relationship between major depression and anxiety disorders (OR = 2.5–8.6). At the same time, the risk of major depression is assessed as high if the patient has had dysthymia (OR=4.7), panic disorder (OR=1.9), social phobia (OR=2.0), or specific phobia in the last 12 months. (OR=2.0) and generalized anxiety disorder (OR=2.2). The disadvantage of this and similar population-based studies is that, as a rule, associations of depression with psychotic disorders are not taken into account.

In particular, the analysis of data on the comorbidity of depression [47] showed that the closest relationship at the time of the survey was the relationship between major depression and anxiety disorders (OR = 2.5–8.6). At the same time, the risk of major depression is assessed as high if the patient has had dysthymia (OR=4.7), panic disorder (OR=1.9), social phobia (OR=2.0), or specific phobia in the last 12 months. (OR=2.0) and generalized anxiety disorder (OR=2.2). The disadvantage of this and similar population-based studies is that, as a rule, associations of depression with psychotic disorders are not taken into account.

In a large epidemiological population-based study of comorbidity conducted in the United States under the supervision of R. Kessler for many years [48, 49] - "National comorbidity survey" (National comorbidity survey) NCS-R 4 , the relevance of studying the relationship depression and non-affective disorders. According to the results of the NCS-R, in 72. 1% of patients with depression during their life, comorbidity with non-affective disorders is recorded: in 59.2% - with anxiety, in 24.0% - with dependence on psychoactive substances, in 30.0% - with impulse control disorders. Prevalence of non-affective comorbid disorders in the previous year was also registered quite often - in 64.0% of observations: 57.5% - anxiety disorders, 8.5% - dependence on psychoactive substances, 16.6% - impulse control disorders 5 . Along with the determination of frequency indicators 6 , the authors carried out a correlation analysis: statistically significant correlations were obtained between depression and panic disorder ( r = 0.48), agoraphobia ( r = 0.52), isolated phobia ( r =0.43), social phobia ( r =0.52), generalized anxiety disorder ( r =0.62), post-traumatic stress disorder ( r =0.50), obsessive-compulsive disorder ( r = 0.42), separation anxiety ( r = 0.

1% of patients with depression during their life, comorbidity with non-affective disorders is recorded: in 59.2% - with anxiety, in 24.0% - with dependence on psychoactive substances, in 30.0% - with impulse control disorders. Prevalence of non-affective comorbid disorders in the previous year was also registered quite often - in 64.0% of observations: 57.5% - anxiety disorders, 8.5% - dependence on psychoactive substances, 16.6% - impulse control disorders 5 . Along with the determination of frequency indicators 6 , the authors carried out a correlation analysis: statistically significant correlations were obtained between depression and panic disorder ( r = 0.48), agoraphobia ( r = 0.52), isolated phobia ( r =0.43), social phobia ( r =0.52), generalized anxiety disorder ( r =0.62), post-traumatic stress disorder ( r =0.50), obsessive-compulsive disorder ( r = 0.42), separation anxiety ( r = 0. 37), dysthymia ( r = 0.88), mania ( r = 0.63), oppositional disorder ( r = 0.48), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ( r =0.50), transient explosiveness ( r = 0.39). As in the above-mentioned work by D. Hasin et al. [47], in the NCS-R study, the set of comorbid depression of non-affective disorders was limited to the pathology of the neurotic and pathocharacterological circle, while comorbidity with disorders of more severe psychopathological registers was not analyzed 7 .

37), dysthymia ( r = 0.88), mania ( r = 0.63), oppositional disorder ( r = 0.48), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ( r =0.50), transient explosiveness ( r = 0.39). As in the above-mentioned work by D. Hasin et al. [47], in the NCS-R study, the set of comorbid depression of non-affective disorders was limited to the pathology of the neurotic and pathocharacterological circle, while comorbidity with disorders of more severe psychopathological registers was not analyzed 7 .

Indicators of comorbidity depression with psychotic level disorders , as a rule, can be judged only thanks to the data of some authors who analyzed the ratio of manifestations of independent affective and hallucinatory-delusional series at the symptomatic level [52], or indirectly - according to information obtained during study of patients with schizophrenia. Thus, M. Ohayon and A. Schatzberg [52] in a population study 18 9In 80 residents of the UK, Germany, Spain, Italy, Portugal, at least one of the three basic symptoms of depression was found in 16. 5% of the surveyed (95% CI = 16.0-17.1%). In turn, among them, 12.5% were also diagnosed with psychotic symptoms - delusions (4.1%) or hallucinations (7.6%), or both delusions and hallucinations at the same time (0.8%).

5% of the surveyed (95% CI = 16.0-17.1%). In turn, among them, 12.5% were also diagnosed with psychotic symptoms - delusions (4.1%) or hallucinations (7.6%), or both delusions and hallucinations at the same time (0.8%).

According to clinical and epidemiological studies in schizophrenia depression is diagnosed with a frequency of 19.5 to 83.0% [53-58]. Based on such high rates of association of depression with endogenous process pathology, some modern authors [8-10, 15, 16], as mentioned above, interpret depression as an integral part of the schizophrenic process, which can be qualified as a schizophrenic spectrum disorder [16 ]. Thus, according to A. Deister and H. Möller [15], in a number of psychopathological disorders, comorbid schizophrenia, and depression in terms of prevalence, they are second only to hallucinatory-paranoid and apathetic (negative changes) symptom complexes. At the same time, no targeted large clinical and epidemiological comparative studies of the comorbidity of depression and non-affective symptom complexes characteristic of schizophrenia, which would confirm the position on the selective accumulation of depression in this disease, have been conducted so far.

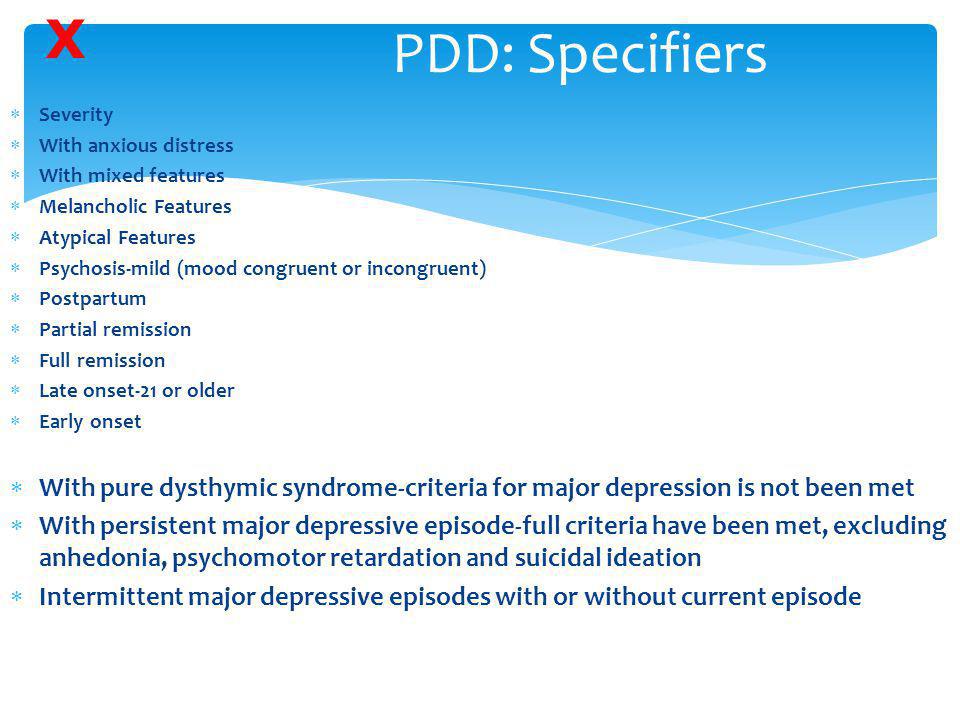

Concluding the discussion of literature data, it should be emphasized that the listed modern studies of depression comorbidity are usually carried out using the ICD-10 or DSM diagnostic criteria (DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR, DSM-5) . At the same time, the headings of these systematics, which are actually qualified at the syndromic level, are naturally used as clinical categories, comorbid depression. In some cases, this approach makes it difficult to compare the results with the data of clinical and epidemiological studies performed using the methodology traditional for domestic psychiatry. Accordingly, the task of analyzing the association of depression not only with disorders of the neurotic level, but also with the pathology of more severe registers, that is, combining in one study a wide range of comorbid disorders: as clinical categories of ICD-10 (anxiety-phobic somatoform, obsessive- compulsive disorder), as well as psychopathological syndromes, traditional for Russian taxonomists ("paranoid", "hallucinatory-paranoid", "paraphrenic"), and qualified, first of all, in the light of their nosological preference within the schizophrenic process. Given the nature of the syndromic-nosological paradigm in domestic psychiatry, such clinical categories, which are actually correlated with the registers of A.V. Snezhnevsky, it seems appropriate to analyze their relationship with depressive disorders at the modern methodological level. This approach allows comparing data with the results of modern foreign and domestic clinical and epidemiological studies.

Given the nature of the syndromic-nosological paradigm in domestic psychiatry, such clinical categories, which are actually correlated with the registers of A.V. Snezhnevsky, it seems appropriate to analyze their relationship with depressive disorders at the modern methodological level. This approach allows comparing data with the results of modern foreign and domestic clinical and epidemiological studies.

The purpose of this clinical and epidemiological study is to refute the null hypothesis formulated taking into account the contradictions discussed above in assessing the problem of the relationship between depression and non-affective mental disorders (we are talking about the assumption put forward by some modern researchers about the affinity of depressive disorders not only to the broad circle of neurotic, but also psychotic, acting in the process of progressive development of an endogenous disease, disorders) and checking the article 9 put forward by the authors0015 hypothesis about the heterogeneity of the structure of the relationship between depression and non-affective mental disorders, which interprets the role of depression not only as an agonist, but also as an antagonist to mental disorders of other psychopathological registers; the possibility of a third variant of correlations is assumed, determined by the lack of selectivity (“inertness”) of depressions to heteronomous in relation to affective syndromes.

The authors believe that testing the proposed hypothesis will make it possible to establish a different direction (positive or negative) of the relationship between depression and non-affective disorders and, accordingly, to explain the non-random nature of both close, but with different strength of association, relationships of depression with some syndromes, and the mechanism of "repulsion" of depression from another, belonging to more severe psychopathological registers, a group of mental disorders.

Material and methods

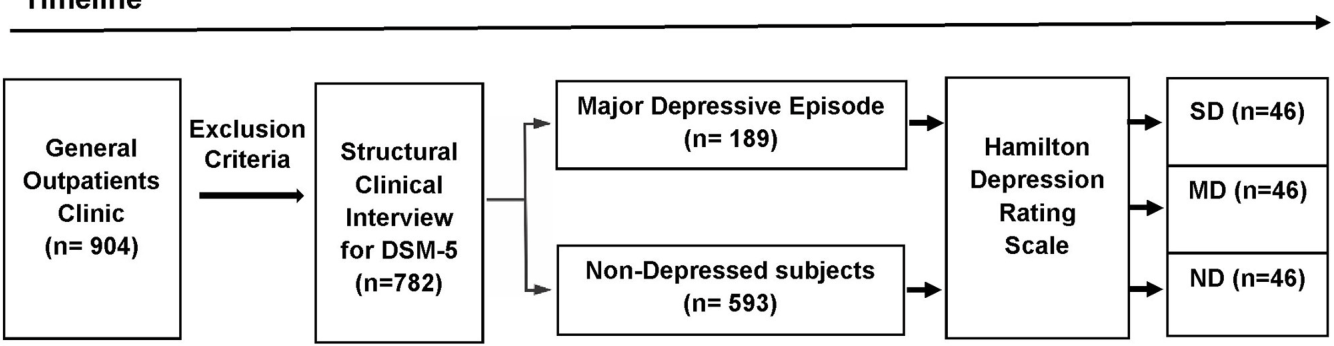

The study was planned in two stages and performed on a clinical base, the characteristics of patients of which are representative in terms of mental pathology of the maximum possible number of psychopathological registers - a large city psychiatric clinical hospital (Moscow Psychiatric Clinical Hospital No. 1 named after N.A. Alekseev). To form a sample that assumes, in terms of the tasks set, a wide coverage of patients (in terms of nosology and syndromic psychopathology), patients from 5 departments of this hospital (2 male, 2 female, 1 mixed) were included and the time interval for recruiting hospitalized patients was limited - from February 1 June 30, 2014

At the first (pilot) stage of the study, a clinical sample was recruited - 91 patients (51 men and 40 women). The need for this stage was determined by the desire to check the adequacy of the choice of departments, including the probability of falling into the sample of patients who show signs of not only depression, but also comorbid non-affective pathology, as well as to make preliminary calculations of the minimum required volume of the total (epidemiological) sample of the study. A selective clinical examination was carried out by expert psychiatrists in the form of a personal interview 8 . Broad inclusion criteria for affective pathology were used: patients with signs of depressive disorders, regardless of nosological affiliation and concomitant syndromic disorders. At the same time, comorbid depression and non-affective mental pathology were recorded using a specially designed modular data entry system 9 . The latter, along with sociodemographic and formalized clinical data, suggested the possibility of taking into account such non-affective disorders qualifying at the syndromic level as asthenic, anxiety-phobic, obsessive-compulsive, somatoform, paranoid, hallucinatory-paranoid, paraphrenic, catatonic, pseudopsychopathic, apathoabolic.

The need for this stage was determined by the desire to check the adequacy of the choice of departments, including the probability of falling into the sample of patients who show signs of not only depression, but also comorbid non-affective pathology, as well as to make preliminary calculations of the minimum required volume of the total (epidemiological) sample of the study. A selective clinical examination was carried out by expert psychiatrists in the form of a personal interview 8 . Broad inclusion criteria for affective pathology were used: patients with signs of depressive disorders, regardless of nosological affiliation and concomitant syndromic disorders. At the same time, comorbid depression and non-affective mental pathology were recorded using a specially designed modular data entry system 9 . The latter, along with sociodemographic and formalized clinical data, suggested the possibility of taking into account such non-affective disorders qualifying at the syndromic level as asthenic, anxiety-phobic, obsessive-compulsive, somatoform, paranoid, hallucinatory-paranoid, paraphrenic, catatonic, pseudopsychopathic, apathoabolic. At this stage, not only was the set of diagnostic categories comorbid with depression refined for their further use at the second stage of the study, but the probability of manifestation in patients along with depression of comorbid non-affective disorders was also determined, provided that only patients with depression at the time of examination were included in the clinical sample.

At this stage, not only was the set of diagnostic categories comorbid with depression refined for their further use at the second stage of the study, but the probability of manifestation in patients along with depression of comorbid non-affective disorders was also determined, provided that only patients with depression at the time of examination were included in the clinical sample.

The second phase of study was designed in such a way as to minimize pilot sample distortions (selection bias) associated with the exclusion of patients hospitalized for non-affective pathology without comorbid depression. To this end, to form the main epidemiological sample of 705 patients (494 men and 211 women) 10 , a continuous method and a retrospective approach developed taking into account the need for content analysis of archival data were used. Data for statistical analysis were obtained as a result of studying the medical records (case histories) of all patients admitted to the above 5 hospital departments for the same time interval. In contrast to the first stage, psychopathological disorders (syndromes) were taken into account not only at the time of hospitalization, but also throughout life, both in patients suffering from depressive disorders and without them.

In contrast to the first stage, psychopathological disorders (syndromes) were taken into account not only at the time of hospitalization, but also throughout life, both in patients suffering from depressive disorders and without them.

An analysis of conjugation tables (2x2) was used to assess the relationship between depression and non-affective mental disorders. Statistical significance (significance) of differences was assessed using Fisher's exact test. The OR and its 95% CI were also determined. In order to eliminate the possible influence of gender differences, partial correlations were calculated with a sex correction. Statistical processing was carried out using the licensed statistical package SPSS 20 11 .

The study design made it possible to minimize the error that occurs when studying the comorbidity of non-affective disorders and depression with strict sampling criteria, since the entire nosological and syndromic repertoire from psychiatric practice was included 12 . Thanks to this design, it was possible to clarify the prevalence of depression, taking into account various nosological groups of diseases, and most importantly, to analyze the relationship between depression and non-affective disorders, taking into account the OR indicators and correlation coefficients.

Thanks to this design, it was possible to clarify the prevalence of depression, taking into account various nosological groups of diseases, and most importantly, to analyze the relationship between depression and non-affective disorders, taking into account the OR indicators and correlation coefficients.

Results

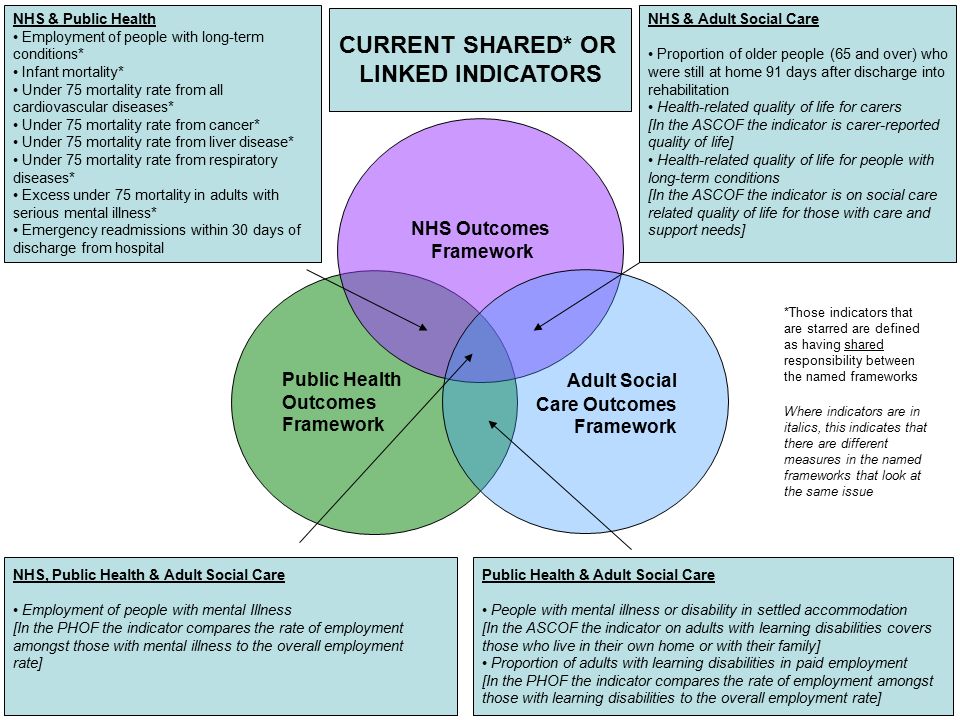

The frequency of depression in the general sample at the time of the examination was 40.3%, and the rate of its presence during life was naturally higher - 56.0%. Mania was also noted in 14.5% of patients during their lifetime. The distribution of patients in the general sample, taking into account the nosological affiliation, is presented in Table. 1. It indicates the representativeness of the sample, taking into account the need to study the association of depression with a wide range of disorders, with special attention to severe registries. In table. Table 2 shows summary data regarding the analysis of the relationship between depression and other disorders using nosological categories, which confirms the idea that studying the problem from these positions is not informative.

Table 1. Distribution of patients in the general sample according to nosological diagnoses * - in 7 cases, the data of medical records was not enough for an unambiguous nosological interpretation of mental disorders diagnosed at the syndromic level and coded by ICD-10 rubrics.

Table 2. Association of diagnosis and depression during life with distribution by gender

The study of the prevalence of depressive pathology throughout life in patients, taking into account the manifestations of other psychopathological syndromes, gave a high percentage of various combinations (Fig. 1). In almost all non-affective disorders (with the exception of paraphrenia and dementia), more than 50% of patients had depression during their lifetime.

Rice. 1. The proportion of patients with depression, taking into account the presence / absence of mental disorders (during life). Light column - there is a mental disorder, dark - no. Here and in Fig. 2:1 - apathetic dementia; 2 - pseudopsychopathic disorders; 3 - catatonia; 4 - paraphrenic syndrome; 5 - hallucinatory-paranoid syndrome; 6 - paranoid syndrome; 7 - somatoform disorders; 8 - obsessive-compulsive disorders; 9 - anxiety-phobic disorder; 10 - asthenia.

Comparison of the corresponding frequency pairs - non-affective disorder with depression and non-affective disorder without depression - for the studied symptom complexes is shown in Fig. 2.

Rice. 2. Comparative prevalence at the time of the survey of non-affective disorders with and without comorbid depression. * — differences are statistically significant at p<0.05. The light column is a mental disorder without depression, the dark column is with depression.

According to the results obtained, the frequency of asthenia, anxiety-phobic, obsessive-compulsive and somatoform disorders in depression is statistically significantly higher than the frequency of these non-affective disorders among patients without depression in the same cohort of patients: 20.8% vs. 8.1%; 9.9% vs. 1.9%; 1.8% vs. 0.7%; 20.1% versus 5.5% respectively. This may indicate the affinity of depression to the listed disorders, which occur in depression with a frequency exceeding the indicator that characterizes the studied contingent as a whole, i. e. more often than by chance.

e. more often than by chance.

In turn, the frequency of paranoid syndrome with depression and without it showed no statistically significant differences (4.6% versus 5.2%), which may indicate the "random" nature of the combination of these disorders in the studied population.

On the contrary, the frequency of hallucinatory-paranoid, paraphrenic syndromes, catatonia, pseudopsychopathic, abulic symptom complexes in depression was statistically significantly lower than the frequency of these non-affective disorders among patients without depression in the same cohort of patients: 30.3% vs. 50.6%; 1.4% vs 5.7%; 1.4% vs 4.5%; 38.0% vs 49%; 7.0% versus 16.6% respectively. This may indicate an inverse relationship and a "repulsion" mechanism between depressive pathology and the listed non-affective symptom complexes, which, although they occur in combination with depression, are at the same time their frequency is lower than the indicator characterizing the studied contingent as a whole, i. e., lower than expected.

e., lower than expected.

The obtained pairs of frequencies allowed for each combination of "non-affective disorder - depression" to calculate the OR and study the strength of the connection. An analysis of O.S. calculated for men and women separately (Fig. 3) showed that the associations with depression found for the studied non-affective disorders in the main (epidemiological) sample should be considered taking into account the contribution of the gender factor. The patterns obtained in the general sample are fully preserved among men, while in women a different (taking into account the lower threshold) strength of depression associations is revealed: in most cases (with the exception of somatoform disorder) it is insufficient, i.e. less than 1. These data First of all, they indicate the need for a further increase in the number of women in the total sample in order to obtain more correct data.

Rice. 3. OR of comorbid non-affective pathology in depression. It should be taken into account that there were more men in the epidemiological sample than women.

In this analysis, a sex-adjusted correlation analysis was performed to assess the association of non-affective disorders with depression and account for gender disparity (male predominance). The calculation was carried out differentially for indicators of the prevalence of depression during life and at the time of the survey. Data for comorbid depression of non-affective disorders are presented in Fig. 4 and 5, respectively.

Rice. 4. Correlation of depression (throughout life) with non-affective mental disorders. * — significant correlations at the p<0.05 level. Here and in Fig. 5: 1 - asthenia; 2 - anxiety-phobic disorder; 3 - obsessive-compulsive disorder; 4 - somatoform disorder; 5 - paranoid syndrome; 6 - hallucinatory-paranoid syndrome; 7 - paraphrenic syndrome; 8 - catatonia; 9 - pseudopsychopathic disorders; 10 - apathetic dementia.

Rice. 5. Correlation of depression (at the time of the survey) with non-affective mental disorders. For the designation of disorders and the significance of correlations, see Fig. 4.

4.

In accordance with the data of correlation analysis, it was confirmed that asthenia, phobic anxiety and somatoform disorders statistically significantly positively correlated with depression both during life and at the time of the survey. This correlates both with the above data from foreign literature on comorbidity, and with the results of previous psychopathological studies in the Department for the Study of Borderline Mental Pathology and Psychosomatic Disorders of the Scientific Center for Mental Health [60-64], according to which the association of asthenic, anxiety-phobic and somatoform symptom complexes with affective disorders are characteristic throughout the affective and neurotic pathology, regardless of the stage of the disease (debut, exacerbation, remission, outcome).

Pathology that meets the criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder, showing a statistically significant positive correlation with depression throughout life, loses statistical significance when calculating the correlation coefficient at the time of the survey, but retains the direction of the relationship - the trend towards positive correlation persists. Perhaps this change is associated with a small number of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder in our sample or with the peculiarities of the course of the disease (more pronounced affective disorders at the initial stage of the pathology, which proceeds with the identification of obsessions, with their subsequent leveling as clinically completed disorders develop).

Perhaps this change is associated with a small number of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder in our sample or with the peculiarities of the course of the disease (more pronounced affective disorders at the initial stage of the pathology, which proceeds with the identification of obsessions, with their subsequent leveling as clinically completed disorders develop).

Paranoid syndrome both during life and at the time of the survey shows a statistically insignificant minimal negative correlation with depression, which makes it possible to assume that these disorders are relatively independent.

Hallucinatory-paranoid and paraphrenic syndromes, both during life and at the time of the survey, show a negative correlation with depression. However, if, when calculated by lifetime prevalence, the correlation does not reach the level of statistical significance (-0.049and -0.032, respectively), then at the time of the survey, the trend is increasing - the negative correlation is statistically significant (-0. 227 and -0.124, respectively). The clinical interpretation of such statistical patterns can be based on the assumption of a more significant impact of affective disorders in the early stages of a progressive mental pathology that occurs with hallucinatory-paranoid and paraphrenic symptom complexes. The latter, when assessed at the time of the survey, on the contrary, show a negative correlation (“repulsion”) with depressive disorders, leveled at earlier stages of the disease, which is reflected in the absence of a statistically significant correlation when assessing the lifetime prevalence of depression.

227 and -0.124, respectively). The clinical interpretation of such statistical patterns can be based on the assumption of a more significant impact of affective disorders in the early stages of a progressive mental pathology that occurs with hallucinatory-paranoid and paraphrenic symptom complexes. The latter, when assessed at the time of the survey, on the contrary, show a negative correlation (“repulsion”) with depressive disorders, leveled at earlier stages of the disease, which is reflected in the absence of a statistically significant correlation when assessing the lifetime prevalence of depression.

Apathetic dementia (apato-abulic disorders) is also characterized by a negative correlation with depression. At the same time, the statistical significance of the connection is maintained both throughout life and at the time of the survey.

With regard to the catatonic syndrome and pseudopsychopathic disorders, if during life both syndromes show a positive, although statistically insignificant, correlation with depression, then at the time of the survey, the direction of the relationship changes to the opposite (negative correlation), and for catatonia, this relationship becomes more statistically significant . This allows, on the one hand, to state the inconsistency of the trend that makes it necessary to conduct further research, on the other hand, this feature brings these disorders closer to obsessive-compulsive disorder, hallucinatory-paranoid and paraphrenic syndromes. This, presumably, can be about leveling the role of depressive disorders (significant at the initial stages of progressive pathology) as the disease progresses.

This allows, on the one hand, to state the inconsistency of the trend that makes it necessary to conduct further research, on the other hand, this feature brings these disorders closer to obsessive-compulsive disorder, hallucinatory-paranoid and paraphrenic syndromes. This, presumably, can be about leveling the role of depressive disorders (significant at the initial stages of progressive pathology) as the disease progresses.

The limitation of the results obtained is that the strength of the correlation in the presence of statistical significance remains small (less than 0.6). This may be due to an insufficient sample size (a sample that is 2-4 times larger in terms of the number of patients seems to be more adequate for such an analysis).

Talk

Thus, the results of this study confirm the working hypothesis underlying it. As evidenced by the above data, depression, positively correlated with disorders of the non-affective spectrum of the lightest psychopathological registers (asthenia, anxiety-phobic, obsessive-compulsive, somatoform disorders), with delusional syndromes (paranoid, paraphrenic), correlates inversely or does not detect a correlation (paranoid syndrome). The data obtained are consistent with the results of previous epidemiological studies that assessed the comorbidity of depression and its correlation with non-affective pathology [48, 49, 51], reflecting the close relationship between depression and disorders of the neurotic circle. As for the comorbidity of depression with psychotic disorders belonging to more severe psychopathological registers, the obtained negative values of the correlation coefficients or the absence of a connection reflect a more complex clinical and epidemiological picture.

The data obtained are consistent with the results of previous epidemiological studies that assessed the comorbidity of depression and its correlation with non-affective pathology [48, 49, 51], reflecting the close relationship between depression and disorders of the neurotic circle. As for the comorbidity of depression with psychotic disorders belonging to more severe psychopathological registers, the obtained negative values of the correlation coefficients or the absence of a connection reflect a more complex clinical and epidemiological picture.

In this regard, it is necessary to return to the problem formulated in the first part of this publication and try, on the basis of the data presented, to find an answer to the question posed in the light of the formulated alternative: is depression, in accordance with the concept of E. Kraepelin—A.V. Snezhnevsky as a representative of one of the lightest psychopathological registers, or depression is a unique psychopathological phenomenon, referring, on the one hand, to pathology adjacent to the most mild neurotic disorders in psychopathology, on the other hand, being adjacent (in accordance with the data of M. Birchwood et al. . [8-10]) major schizocar syndromes (hallucinatory-paranoid, pa

Birchwood et al. . [8-10]) major schizocar syndromes (hallucinatory-paranoid, pa

Subscribe to new numbers

Author: Mario Maj

Department of Psychiatry, University of Naples SUN, Naples, Italy

Issue page numbers: 85-87

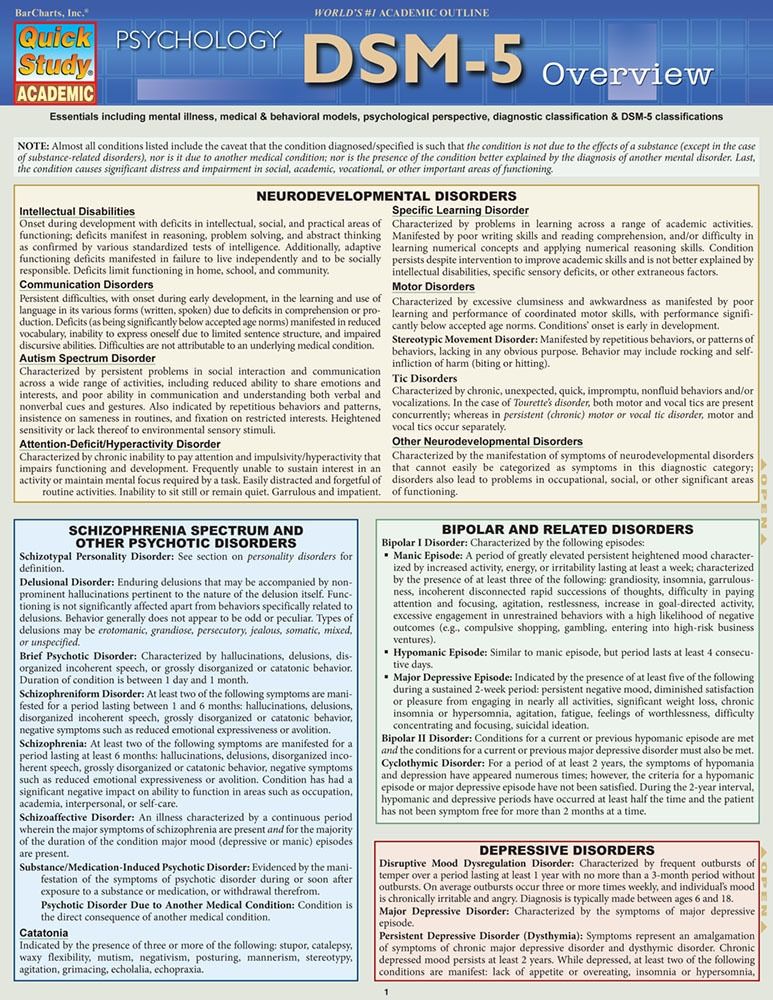

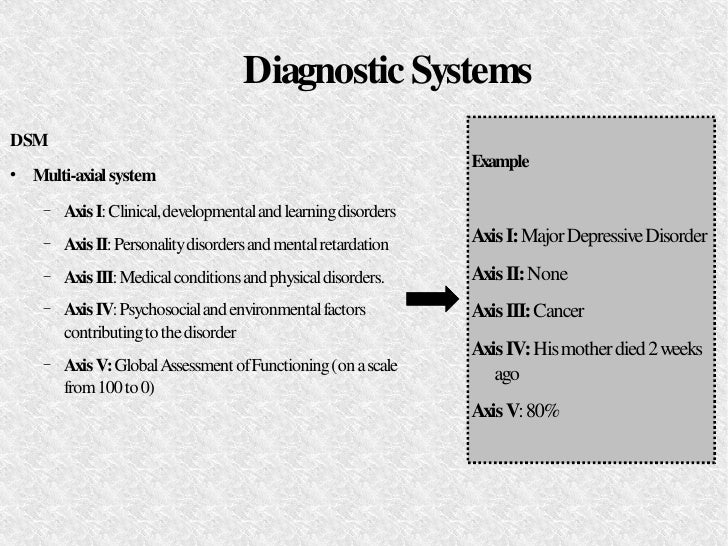

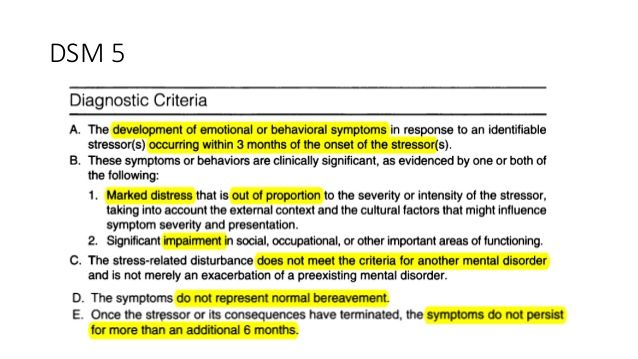

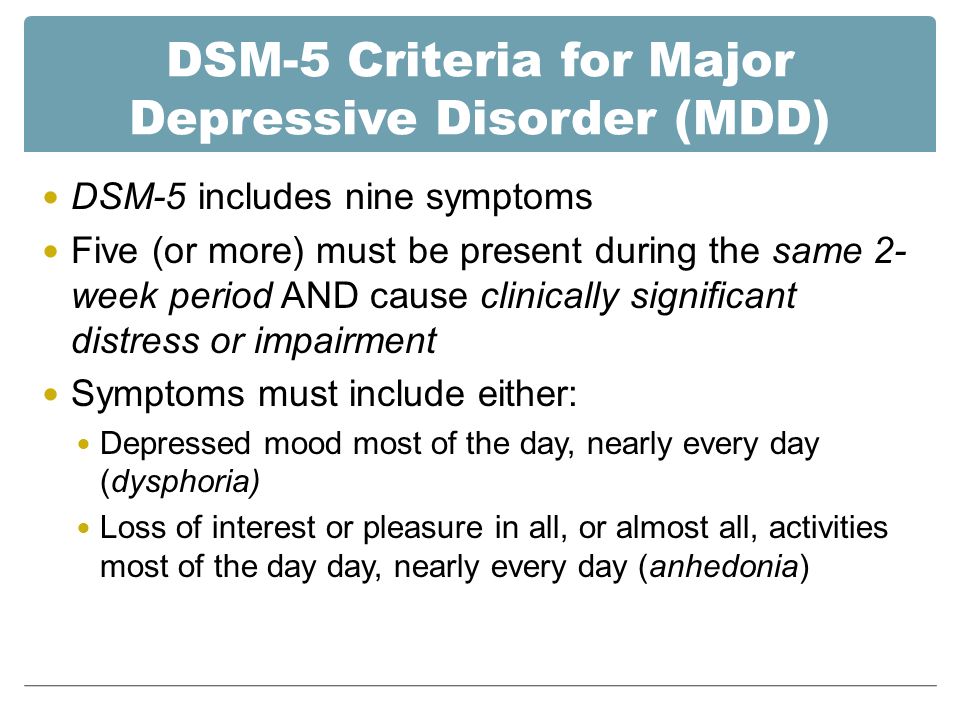

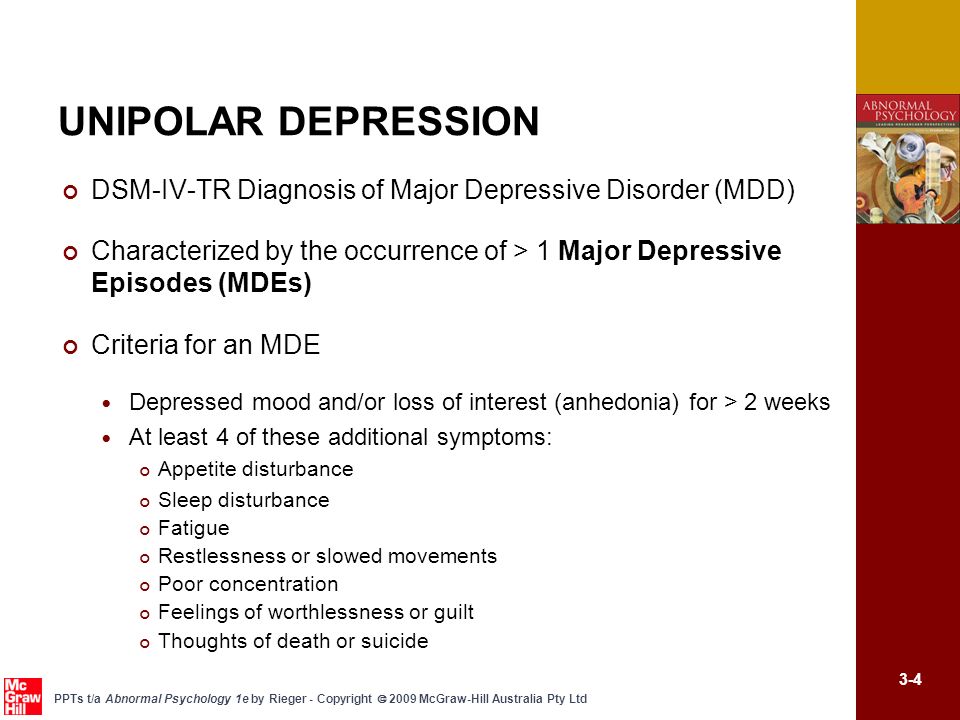

The introduction of "accurate diagnostic criteria" into psychiatry - initially only for research purposes and, subsequently, with the advent of DSM-III, also for everyday clinical practice - had the main goal of overcoming "the uncertainty and subjectivism inherited from the traditional diagnostic process". This was especially true of the variability in the inclusion and exclusion criteria used by clinicians in making a diagnosis (“criterion variance”), which was cited as the main reason for the poor reliability of the diagnosis.

The introduction of "precise diagnostic criteria" into psychiatry - initially only for research purposes and, subsequently, with the advent of DSM-III, also for everyday clinical practice - had the main goal of overcoming "the uncertainty and subjectivism inherited from the traditional diagnostic process" (1, p 85). This was especially true of the variability in the inclusion and exclusion criteria used by clinicians in making a diagnosis (“criterion variance”), which has been cited as the main reason for the poor reliability of the diagnosis (2).

Initially, there were conflicting opinions in the mainstream of American psychiatry about the limitations that the practice of clinical judgment would face when accurate diagnostic criteria emerged. Spitzer et al (3) reported in an early publication on the development of the DSM-III that "the application of precise criteria does not, of course, preclude clinical judgment", adding that "the proper application of such criteria requires a great deal of clinical experience and knowledge of psychopathology" thus giving the impression that clinical judgment is only a way of properly applying precise diagnostic criteria. However, they also argued that "in any case, the DSM-III criteria will only be recommended, and any clinician is free to apply or override these criteria at their discretion" (3, p. 119one).

However, they also argued that "in any case, the DSM-III criteria will only be recommended, and any clinician is free to apply or override these criteria at their discretion" (3, p. 119one).

Spitzer et al's suggestion that operational criteria would appear in the DSM-III "under the heading 'recommended criteria'" (3, p. 1190) has not materialized. However, the introduction to DSM-III emphasized that these criteria are "guidelines for each diagnosis" so as not to leave the clinician "alone to determine the content and boundaries of diagnostic categories" (4, p. 8). According to a later commentary by Spitzer (5, p. 403), the DSM-III diagnostic criteria were created "as guidelines, not strict rules."

This was further clarified in the introduction to the DSM-IV, which states that the precise diagnostic criteria “are intended to be used as a guide in clinical judgment and should not be used in the manner of strictly following cookbook recipes” (6, p. xxiii ). An example is given in which the diagnosis is made by clinical judgment, although the clinical manifestations fall slightly short of full criteria. Thus, clinical judgment is not only a means of using precise criteria; it allows the psychiatrist, at his discretion, to "pull up" these criteria to a certain extent.

Thus, clinical judgment is not only a means of using precise criteria; it allows the psychiatrist, at his discretion, to "pull up" these criteria to a certain extent.

Clinical judgment is also mentioned in the text of the DSM-IV when it comes to assessing the clinical severity required to diagnose certain disorders: “Determining whether a criterion is being met, especially when evaluating role functioning, is an inherently complex clinical task” (6, p .7). The leader of the DSM-IV Working Group, A. Frances, emphasized that “this appeal to clinical judgment is a reminder that it is necessary to evaluate not only the presence of symptoms that meet the criteria, but also whether these symptoms are so severe as to speak about mental disorder", although he acknowledged that the assessment of clinical severity using clinical judgment "contains elements of a tautology" (7, p. 119).

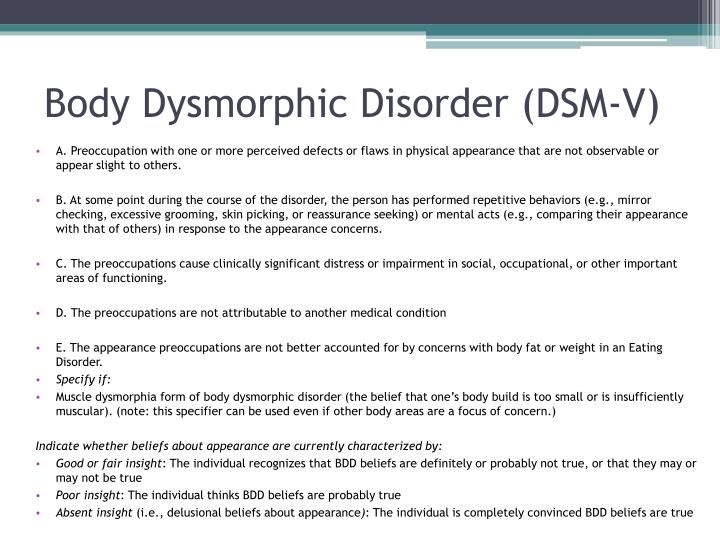

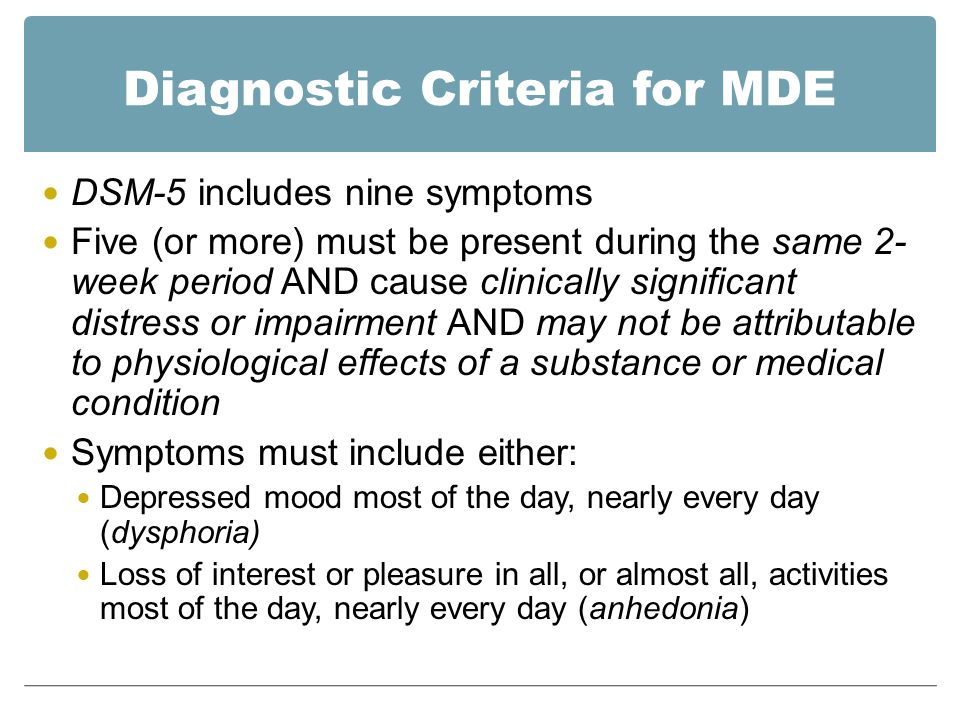

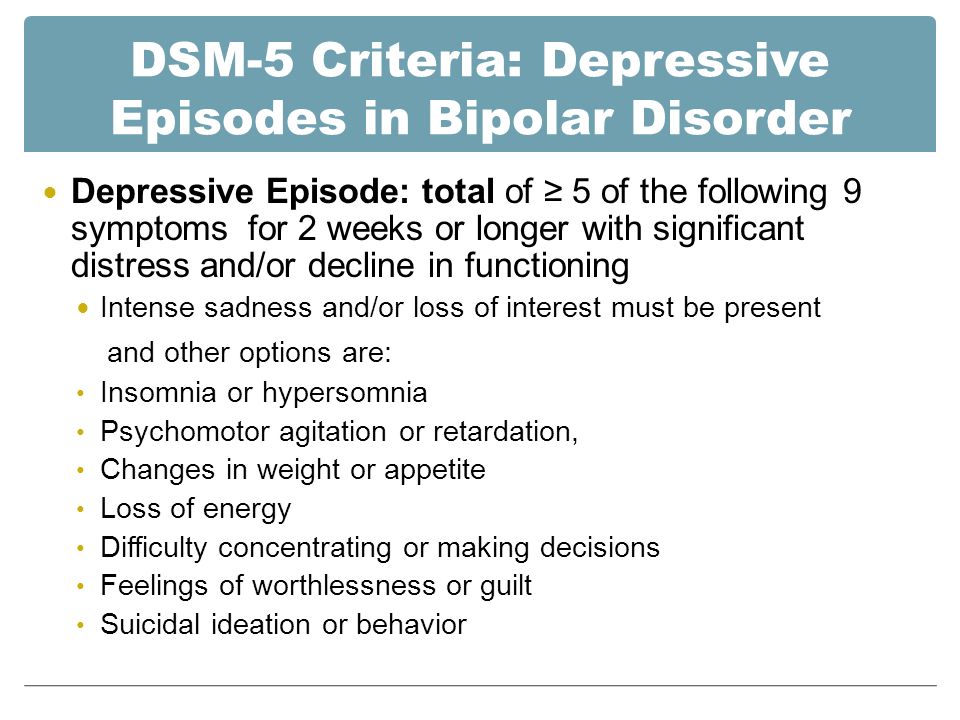

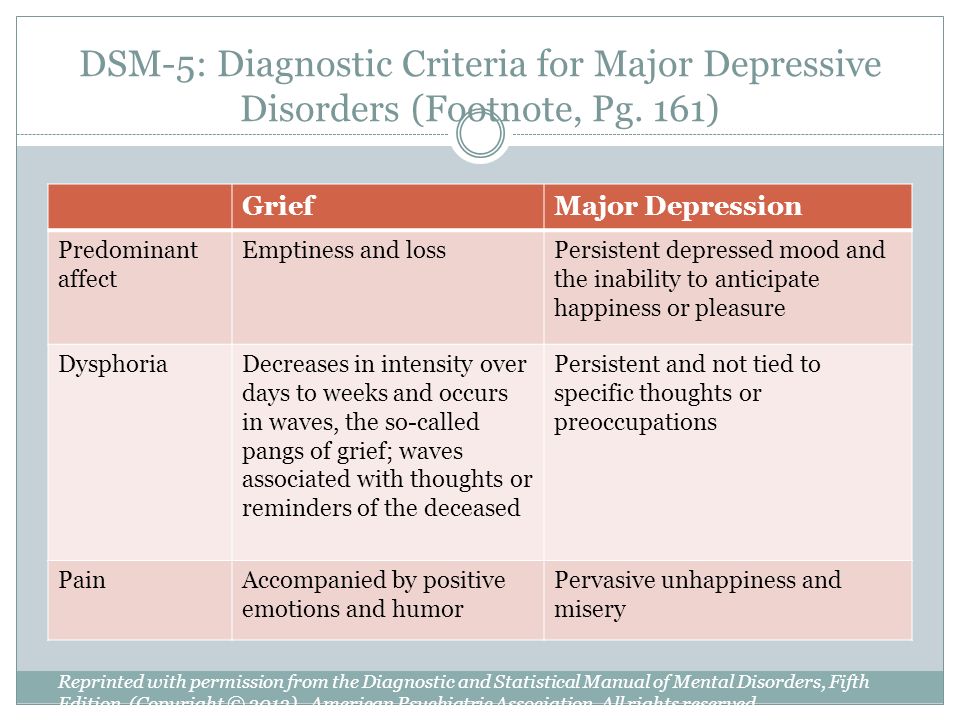

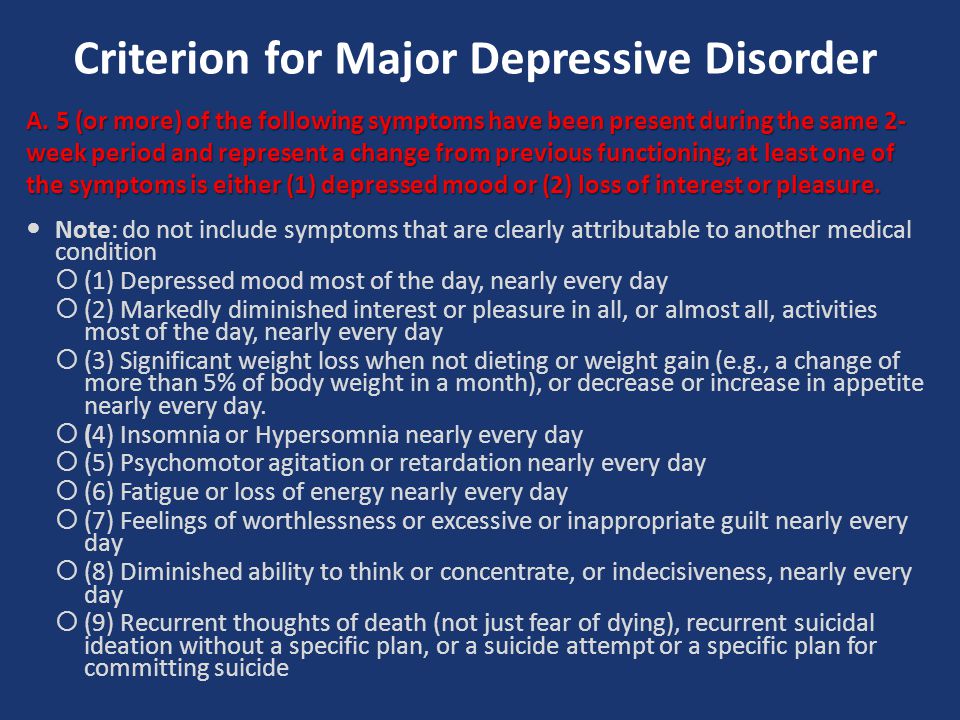

As noted by Spitzer and Wakefield (8), there is no indication in the DSM-IV for the use of clinical judgment in the differential diagnosis between depression and a "normal" response to significant loss. The text makes it clear that a diagnosis of major depression can be made if the criteria for severity, duration, and distress/functional impairment are met, even if the depressive state is a psychologically understandable response to a psychosocial stressor (6, p. 326). The only exception is bereavement: if the depression is due to the loss of a loved one, a diagnosis of major depression cannot be made even if the diagnostic criteria are met, except for the presence of additional features (symptoms persist for more than 2 months, or are marked by impaired functioning, painful workload). feelings of worthlessness, suicidal thoughts, psychotic symptoms, or psychomotor retardation). That is, in either case—whether depression is associated with bereavement or not—precise diagnostic criteria are given and no mention is made of the use of clinical judgment.

The text makes it clear that a diagnosis of major depression can be made if the criteria for severity, duration, and distress/functional impairment are met, even if the depressive state is a psychologically understandable response to a psychosocial stressor (6, p. 326). The only exception is bereavement: if the depression is due to the loss of a loved one, a diagnosis of major depression cannot be made even if the diagnostic criteria are met, except for the presence of additional features (symptoms persist for more than 2 months, or are marked by impaired functioning, painful workload). feelings of worthlessness, suicidal thoughts, psychotic symptoms, or psychomotor retardation). That is, in either case—whether depression is associated with bereavement or not—precise diagnostic criteria are given and no mention is made of the use of clinical judgment.

When J. Wakefield proposed to exclude "normal" reactions to psychosocial stressors from the diagnosis of major depression, leaving it up to the clinician to decide whether the depressive reaction was adequate to the previous stressor or not (8,9), a refutation by K. Kendler, a follower mainstream American psychiatry (as well as the development of the DSM-5) was unequivocal: this is a return to what "in essence will be the subjective criteria proposed by Jaspers in his old idea of \u200b\u200b" understandability "and represents" more a step back than forward for our specialties” (10, pp. 149-150).

Kendler, a follower mainstream American psychiatry (as well as the development of the DSM-5) was unequivocal: this is a return to what "in essence will be the subjective criteria proposed by Jaspers in his old idea of \u200b\u200b" understandability "and represents" more a step back than forward for our specialties” (10, pp. 149-150).

This "step back" was taken to a certain extent in DSM-5 (11). A note included in the DSM-5 Criteria for Major Depressive Disorder states that “reactions to significant loss (eg, bereavement, financial ruin, natural disaster, major illness, or disability) may include intense sadness, ruminations of loss, insomnia, decreased appetite, and weight loss as defined in Criterion A that may resemble a depressive episode" and that deciding whether this condition is a major depressive episode or just a normal response to loss "necessarily requires the use of clinical judgment, taking into account the history and norms expressions of experiences of loss within the framework of a particular culture” (11, p. 161).

161).

This decision by the DSM-5 working group should be seen in the context of the ongoing debate in both the scientific and lay press (eg12,13) to remove the bereavement exclusion criterion from the diagnosis of major depression. This innovation, announced on the DSM-5 website early in the development of this classification (14), raised concerns about a possible simplification of the concept of depression, and therefore mental illness, since expressing a depressive response to the death of a loved one is an accepted behavior in some cultures ( for example, 15). It has also been pointed out that, contrary to the DSM-5 website, the ICD-10 excludes “culturally-based bereavement reactions” from the diagnosis of depression, and this trend is likely to continue in the ICD-11 (16). The introduction of a note emphasizing the important role of clinical judgment in the differential diagnosis between depression and a “normal” response to significant loss may help mitigate the effects of removing the bereavement exclusion criterion and harmonizing between DSM-5 and ICD-11.

It is safe to say that this new emphasis on clinical judgment will be welcomed by many clinicians around the world as an important recognition of the limitations of the operational approach, which perhaps "does not reflect the complex thought process that underlies decision making in psychiatric practice" (17, p. 182). Indeed, in a large international survey of practicing psychiatrists conducted by the WPA in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) (18), more than two-thirds of respondents reported that, to be most effective in clinical practice, diagnostic guidelines should contain flexible recommendations that allow for clinical judgment, and no strict diagnostic criteria.

Thus, this DSM-5 footnote is not unexpected and can be seen as a further step in the articulated (and somewhat controversial) approach of mainstream American psychiatry to the issue of clinical judgment.

However, the note leaves some questions open. Can clinical judgment be considered to take precedence over operational criteria in determining whether a response to significant loss is normal or pathological? In other words, would it be possible not to make a diagnosis of major depression with full compliance with the criteria for severity, duration, and distress/impairment of functioning, if the depressive state, according to history and culture, is a “normal” response to bereavement? Or should we be guided by the fact that the diagnosis of major depression must necessarily be made when all criteria are met, and the use of clinical judgment is reserved for doubtful or subthreshold cases? This is not clear at this time, and such uncertainty may contribute to "divergences of interpretation" in the application of the DSM-5 criteria for major depression which, in addition to the divergences caused by the use of clinical judgment, may significantly reduce the reliability of this diagnosis, which has already been deemed "questionable". ” (Kappa coefficient = 0.20-0.35) in clinical testing of an early version of the DSM-5 criteria that did not include this note (19).

” (Kappa coefficient = 0.20-0.35) in clinical testing of an early version of the DSM-5 criteria that did not include this note (19).

In addition, what will happen to epidemiological studies with non-specialist researchers, who by definition are unable to apply clinical judgment when identifying (in the present or past) a period of “normal” sadness or a depressive episode in a respondent? Can we accept two different definitions of major depression, one for clinical purposes and the other for population epidemiological studies? Are we to assume that the available epidemiological studies on the prevalence of major depression are erroneous because no clinical judgment has been used in the diagnosis?

On the other hand, an emphasis on the role of clinical judgment in distinguishing between depression and a “normal” response to a psychosocial stressor may increase the burden of clinician responsibility in some circumstances (eg, in outpatient settings in regions suffering from severe economic crisis) in which borderline cases are frequent, and traditional diagnostic skills become insufficient (see 20). The second note added to the DSM-5 definition of major depression, which differentiates between "normal" grief and depression, can be seen as an attempt to support the use of clinical judgment in practice. However, no such guidelines are provided for distinguishing between a depressive episode and a "normal" response to other psychosocial stressors, so that the clinician may again be left to his own devices (4, p. 8), subject to some bias (see 21), in posing the crucial and often delicate differential diagnosis.

The second note added to the DSM-5 definition of major depression, which differentiates between "normal" grief and depression, can be seen as an attempt to support the use of clinical judgment in practice. However, no such guidelines are provided for distinguishing between a depressive episode and a "normal" response to other psychosocial stressors, so that the clinician may again be left to his own devices (4, p. 8), subject to some bias (see 21), in posing the crucial and often delicate differential diagnosis.

Clarifying those aspects of a mental disorder that are “currently left to clinical judgment” is a difficult task for psychiatry, because “reliance on clinical skills suggests that some manifestations of a mental disorder cannot always be definitively concluded” (22, p. 978 ). The term "clinimetrics" (23) was actually coined to designate "the field concerned with the measurement of clinical problems that have no place in the usual clinical system" (17, p. 177). It can be argued that the updated DSM-5 view of clinical judgment may be an incentive to consider and further develop this area, which may be especially relevant in the case of depression.

List of used literature Hide list

1. Blashfield R.K. The classification of psychopathology. New York: Plenum, 1984.

2. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Research diagnostic criteria. rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978;35:773-82.

3. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Clinical criteria for psychiatric diagnosis and DSM-III. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132:1187-92.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 1980.

5 Spitzer RL Psychiatric diagnosis: are clinicians still necessary? Compr Psychiatry 1983;24:399-411.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

7. Frances A. Problems in defining clinical significance in epidemiological studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:119.

8. Spitzer RL, Wakefield JC. DSM-IV diagnostic criterion for clinical significance: does it help solve the false positive problem? Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1856-64.

9. Horwitz AV, Wakefield JC. The loss of sadness: how psychiatry transformed normal sorrow into depressive disorder. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

10. Kendler K. Book review. The loss of sadness: how psychiatry transformed normal sorrow into depressive disorder, by Horwitz AV, Wakefield JC. Psychol Med 2008;38:148-50.

11. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

12. Wakefield JC, First MB. Validity of the bereavement exclusion to major depression: does the empirical evidence support the proposal to eliminate the exclusion in DSM-5? World Psychiatry 2012;11:3-10.

13. Carey B. Grief could join list of disorders. New York Times, January 24, 2012.

14. Kendler KS. A statement from Kenneth S.Kendler, M.D., on the proposal to eliminate the grief exclusion criterion from major depression. www.dsm5.org.

15. Kleinman A. Culture, bereavement, and psychiatry. Lancet 2012; 379:608-9.

16. MajM. Bereavement-related depression in the DSM-5 and ICD-11. World Psychiatry 2012,11:1-2.17. Fava GM, Rafanelli C, Tomba E. The clinical process in psychiatry: a clinimetric approach. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:177-84.

18. Reed GM, Mendonqa Correia J, Esparza P et al. The WPA-WHO global survey of psychiatrists' attitudes towards mental disorders classification. World Psychiatry 2011;10:

118-31.

19 Regier DA, Narrow WE, Clarke DE et al. DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part II: Test-retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:59-70.

20. MajM. From "madness" to "mental health problems": reflections on the evolving target of psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2012;11:137-8.

21. Garb HN. Cognitive and social factors influencing clinical judgment in psychiatric practice.