Post traumatic stress disorder cases

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Patients After Severe COVID-19 Infection | Infectious Diseases | JAMA Psychiatry

Research Letter

February 18, 2021

Delfina Janiri, MD1; Angelo Carfì, MD2; Georgios D. Kotzalidis, MD, PhD1; et al Roberto Bernabei, MD2; Francesco Landi, MD, PhD2; Gabriele Sani, MD1; for the Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group

Author AffiliationsArticle Information

-

1Department of Psychiatry, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy

-

2Department of Geriatrics, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy

JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):567-569. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0109

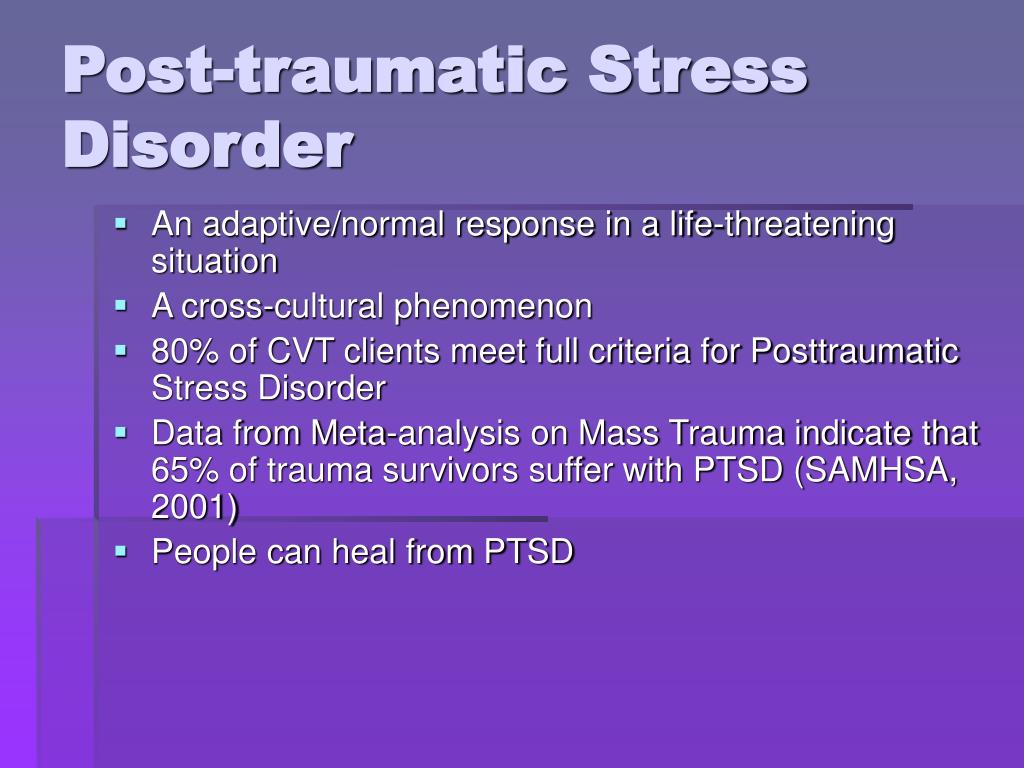

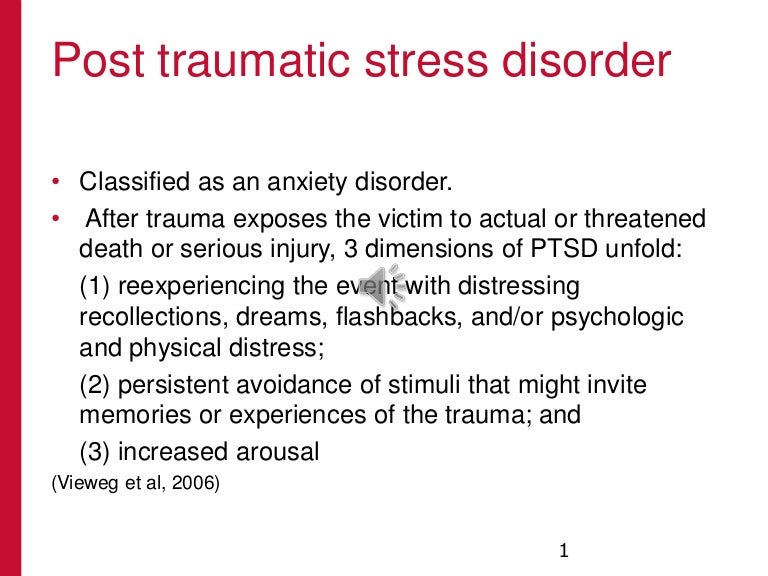

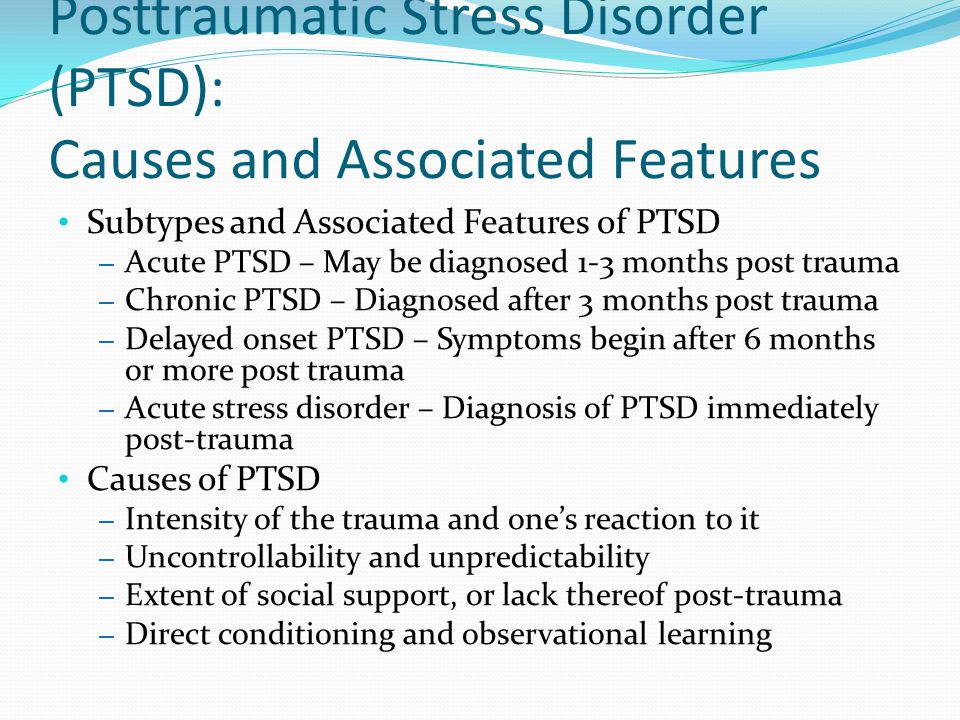

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may occur in individuals who have experienced a traumatic event. Previous coronavirus epidemics were associated with PTSD diagnoses in postillness stages, with meta-analytic findings indicating a prevalence of 32.2% (95% CI, 23.7-42.0).1 However, information after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is piecemeal. We aimed at filling this gap by studying a group of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) who sought treatment at the emergency department, most of whom required hospitalization, eventually recovered, and were subsequently referred to a postacute care service for multidisciplinary assessment.

Methods

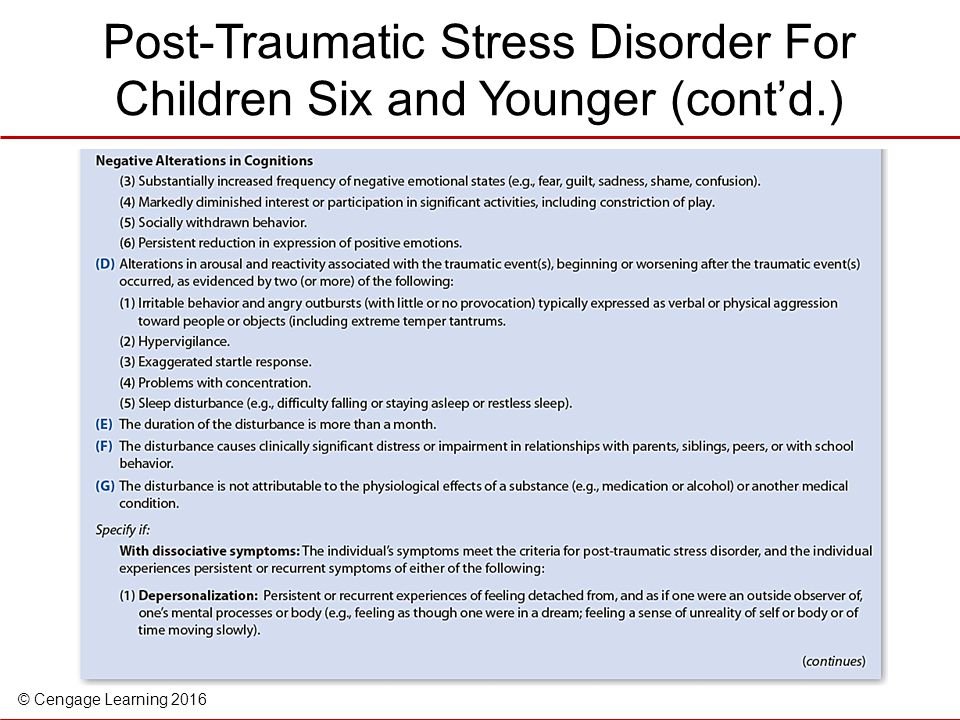

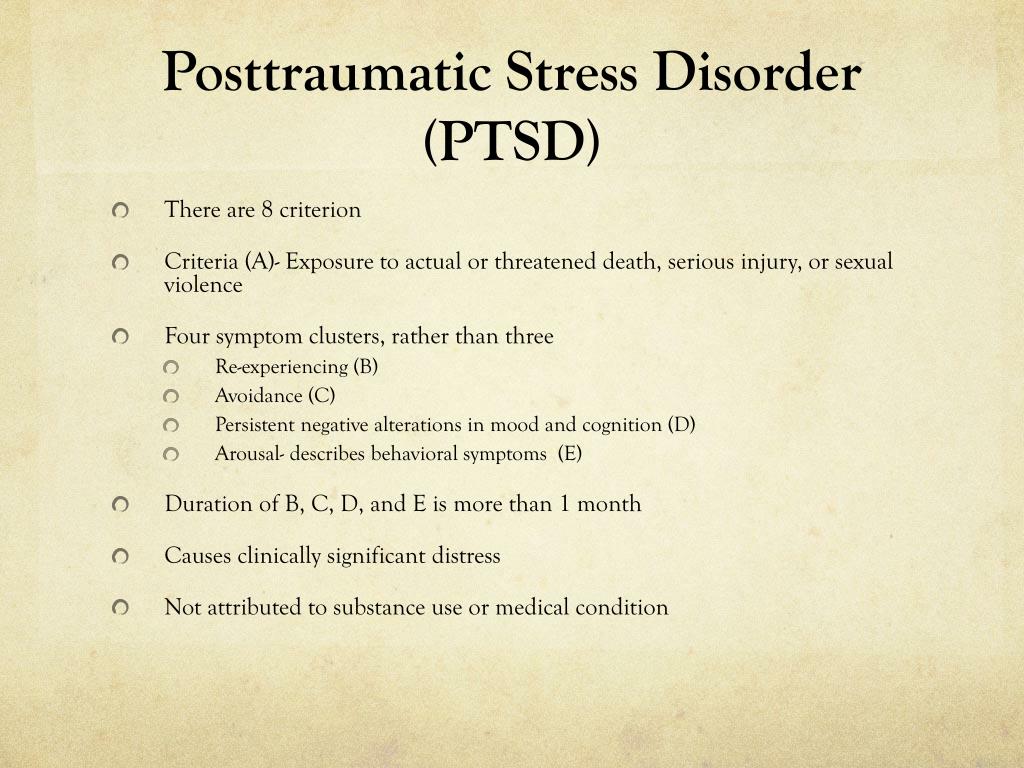

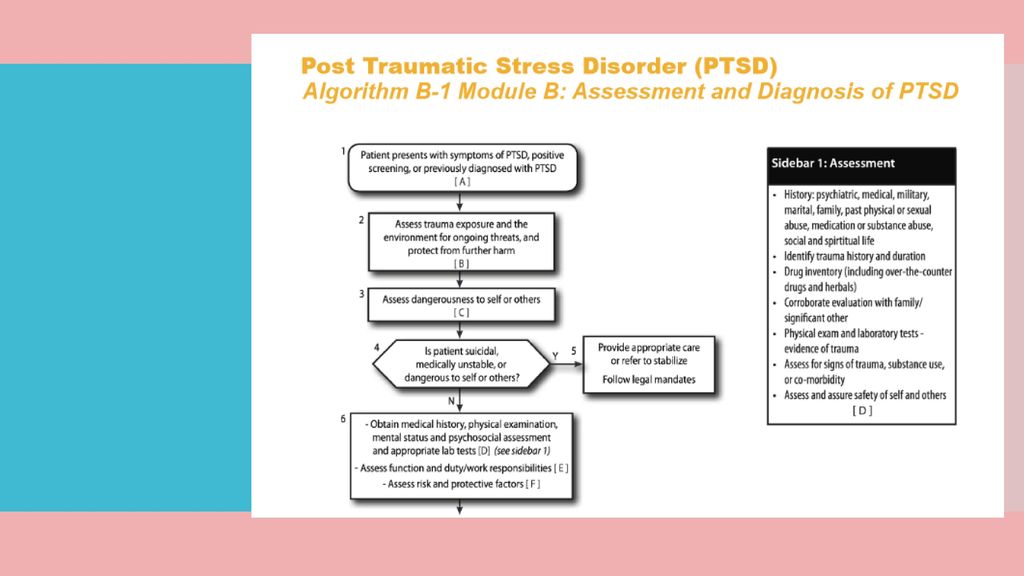

A total of 381 consecutive patients who presented to the emergency department with SARS-CoV-2 and recovered from COVID-19 infection were referred for a postrecovery health check to a postacute care service established April 21, 2020, at the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS in Rome, Italy. Patients were offered a comprehensive and interdisciplinary medical and psychiatric assessment, detailed elsewhere,2 which included data on demographic, clinical, psychopathological, and COVID-19 characteristics. Trained psychiatrists diagnosed PTSD using the criterion-standard Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), reaching a Cohen κ interrater reliability of 0.82. To meet PTSD criteria, in addition to traumatic event exposure (criterion A), patients must have had at least 1 DSM-5 criterion B and C symptom and at least 2 criterion D and E symptoms. Criteria F and G must have been met as well. Additional diagnoses were made through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5. Participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Università Cattolica and Fondazione Policlinico Gemelli IRCCS Institutional Ethics Committee.

Patients were offered a comprehensive and interdisciplinary medical and psychiatric assessment, detailed elsewhere,2 which included data on demographic, clinical, psychopathological, and COVID-19 characteristics. Trained psychiatrists diagnosed PTSD using the criterion-standard Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), reaching a Cohen κ interrater reliability of 0.82. To meet PTSD criteria, in addition to traumatic event exposure (criterion A), patients must have had at least 1 DSM-5 criterion B and C symptom and at least 2 criterion D and E symptoms. Criteria F and G must have been met as well. Additional diagnoses were made through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5. Participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Università Cattolica and Fondazione Policlinico Gemelli IRCCS Institutional Ethics Committee.

Data for patients with and without PTSD were compared with the χ2 test for nominal variables and one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. Factors significantly associated with PTSD were subjected to a binary logistic regression. P values were 2-tailed, and significance was set at a P value less than .05. Analyses were performed using R version 4 0.0 (The R Foundation).

Factors significantly associated with PTSD were subjected to a binary logistic regression. P values were 2-tailed, and significance was set at a P value less than .05. Analyses were performed using R version 4 0.0 (The R Foundation).

Results

From April 21 to October 15, 2020, the postacute care service assessed 381 White patients who had recovered from COVID-19 infection within 30 to 120 days, 166 (43.6%) of whom were women. The mean (SD; range) age was 55.26 (14.86; 18-89). During acute COVID-19 illness, most patients were hospitalized (309 of 381 [81.1%]), with a mean (SD) length of hospital stay of 18.41 (17.27) days.

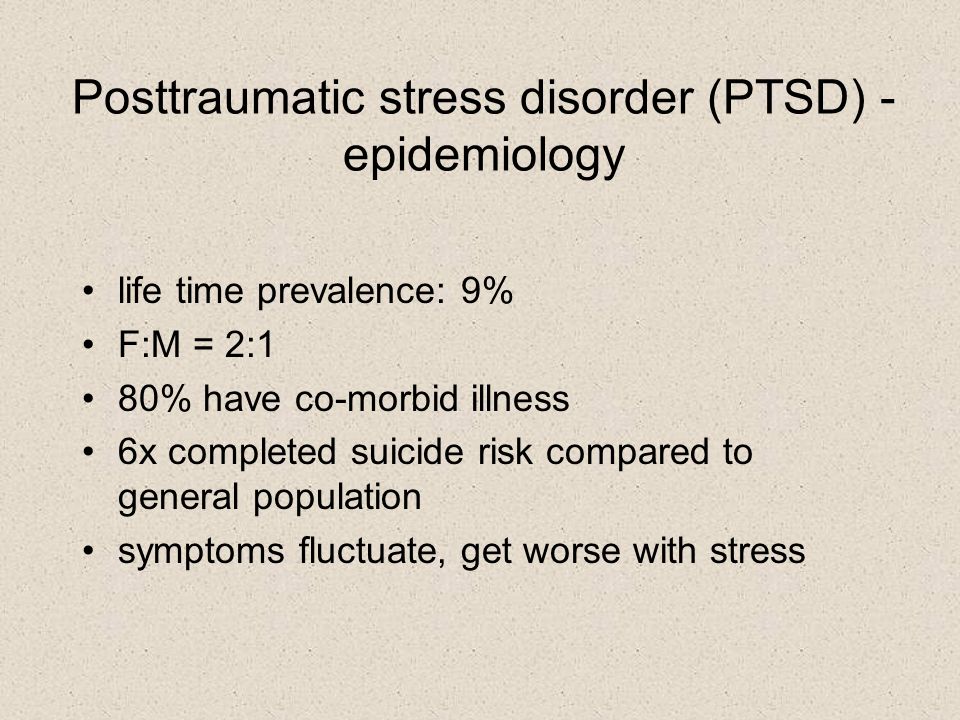

PTSD was found in 115 participants (30.2%). In the total sample, additional diagnoses were depressive episode (66 [17.3%]), hypomanic episode (3 [0.7%]), generalized anxiety disorder (27 [7.0%]), and psychotic disorders (1 [0.2%]). Patients with PTSD were more frequently women (64 [55.7%]), reported higher rates of history of psychiatric disorders (40 [34. 8%]) and delirium or agitation during acute illness (19 [16.5%]), and presented with more persistent medical symptoms in the postillness stage (more than 3 symptoms, 72 [62.6%]) (Table). Logistic regression specifically identified sex (Wald1 = 4.79; P = .02), delirium or agitation (Wald1 = 5.14; P = .02), and persistent medical symptoms (Wald2 = 12.46; P = .002) as factors associated with PTSD.

8%]) and delirium or agitation during acute illness (19 [16.5%]), and presented with more persistent medical symptoms in the postillness stage (more than 3 symptoms, 72 [62.6%]) (Table). Logistic regression specifically identified sex (Wald1 = 4.79; P = .02), delirium or agitation (Wald1 = 5.14; P = .02), and persistent medical symptoms (Wald2 = 12.46; P = .002) as factors associated with PTSD.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study found a PTSD prevalence of 30.2% after acute COVID-19 infection, which is in line with findings in survivors of previous coronavirus illnesses1 compared with findings reported after other types of collective traumatic events (Figure).3-5 Associated characteristics were female sex, which has been extensively described as a risk factor for PTSD,1,3,5 history of psychiatric disorders, and delirium or agitation during acute illness. In the PTSD group, we also found more persistent medical symptoms, often reported by patients after recovery from severe COVID-19.

6

In the PTSD group, we also found more persistent medical symptoms, often reported by patients after recovery from severe COVID-19.

6

This study had limitations, including the relatively small sample size and cross-sectional design, as PTSD symptom rates may vary over time. Furthermore, this was a single-center study that lacked a control group of patients attending the emergency department for other reasons. Further longitudinal studies are needed to tailor therapeutic interventions and prevention strategies.

Back to top

Article Information

Accepted for Publication: January 26, 2021.

Published Online: February 18, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0109

Corresponding Author: Delfina Janiri, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Largo Francesco Vito 1, 00168 Rome, Italy (delfina. [email protected]).

[email protected]).

Author Contributions: Dr Janiri had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Janiri, Carfì, Sani.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Janiri, Kotzalidis, Sani.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Carfì, Kotzalidis, Bernabei, Landi, Sani.

Statistical analysis: Janiri, Sani.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Carfì.

Supervision: Kotzalidis, Bernabei, Landi, Sani.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Sani reports personal fees from Janssen, Angelini Spa, and Lundbeck outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Additional Contributions: We thank the Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group and the patients who contributed their time and effort to participate in this study.

Additional Information: The members of the Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group are listed in reference 2.

References

1.

Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):611-627. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

2.

Landi

F, Gremese

E, Bernabei

R,

et al; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Post-COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32(8):1613-1620. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01616-xPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

2020;32(8):1613-1620. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01616-xPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

3.

Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, et al. Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(12):1427-1434. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

4.

Li X, Aida J, Hikichi H, Kondo K, Kawachi I. Association of postdisaster depression and posttraumatic stress disorder with mortality among older disaster survivors of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1917550. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17550PubMedGoogle Scholar

5.

Galea

S, Ahern

J, Resnick

H,

et al. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(13):982-987. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa013404PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(13):982-987. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa013404PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

6.

Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-605. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12603PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

Aftermath of the Parkland Shooting: A Case Report of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in an Adolescent Survivor

Aftermath of the Parkland Shooting: A Case Report of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in an Adolescent Survivor

Katy McLaughlin, Jeena A. Kar

- Article

- Authors etc.

- Metrics

- Figures etc.

Katy McLaughlin, Jeena A. Kar

Published: November 13, 2019 (see history)

DOI: 10.7759/cureus.6146

Cite this article as: Mclaughlin K, Kar J A (November 13, 2019) Aftermath of the Parkland Shooting: A Case Report of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in an Adolescent Survivor. Cureus 11(11): e6146. doi:10.7759/cureus.6146

Abstract

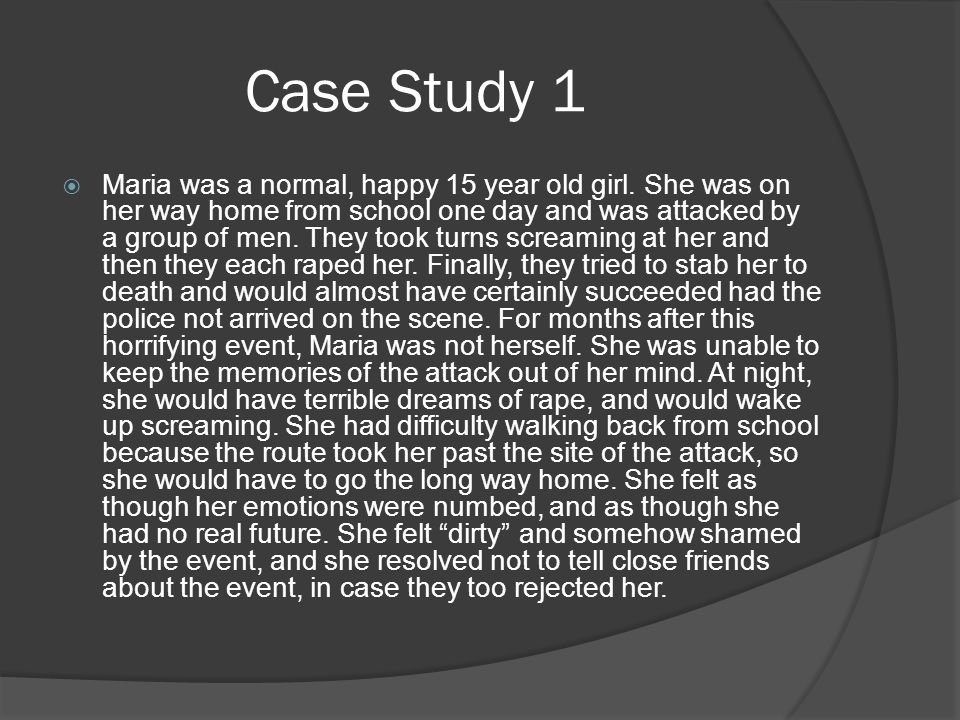

The Journal of Child and Family Studies states that there have been more mass shootings within the last 18 years than in the entire 20th century combined, with 77% carried out by adolescents. This case study aims to evaluate the clinical presentation of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in an adolescent by highlighting the clinical course of a school shooting survivor. Here, we present the case of a 15-year-old female who presented to the emergency department (ED) of the University Hospital Medical Center (UHMC) under the Baker Act by the police for self-injury and self-harm. She had been admitted three times to the psychiatric hospital, all following the trauma of surviving the shooting. She met the criteria for PTSD and was triggered by graphics in the news outlets and social media.

She had been admitted three times to the psychiatric hospital, all following the trauma of surviving the shooting. She met the criteria for PTSD and was triggered by graphics in the news outlets and social media.

As clinicians working with PTSD adolescents, we must be cognizant of these factors as we think about prognosis and create a comprehensive treatment plan. This case study brings to our attention how complex and multifaceted PTSD patients can be in this day and age where social media, news outlets, and television are so pervasive. Three clinical pearls to take home from this patient encounter are: understanding the importance of news and media in modern-day PTSD diagnosis, how certain avoidance behaviors can delay remission, and how uncontrolled re-exposure can lead to poorer outcomes in children and adolescents specifically. It is no longer a rare occurrence to have a patient who has survived a mass school shooting. As a result of this unfortunate reality, clinicians need to be able to recognize and treat symptoms of PTSD in adolescent patients. We must be equipped to expect the interplay of modern triggers such as social media and news media and how it may affect adolescent patients.

We must be equipped to expect the interplay of modern triggers such as social media and news media and how it may affect adolescent patients.

Introduction

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were 39,773 deaths by gun violence in 2017 with only 486 classified as unintentional [1]. Furthermore, the Journal of Child and Family Studies states that there have been more mass shootings within the last 18 years than in the entire 20th century with 77% carried out by adolescents [2]. This care report aims to evaluate the clinical presentation of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adolescents. Research suggests that mass shooting survivors may be at greater risk for mental health difficulties compared with people who experience other types of trauma [3-4]. The National Center for PTSD estimates that 28% of people who have witnessed a mass shooting develop PTSD and 1/3 develop acute stress disorder [5].

Furthermore, this report illustrates an important correlation between media coverage on increasing incidents of shootings as well as other triggers found within various types of media and negative effects on long term prognosis among victims with PTSD. In the discussion, emphasis is placed on awareness and prevention of such violence within communities. The cornerstone for change must begin at the front lines - mental health professionals, parents, and importantly survivors within communities. In order to foster a necessary change, there must be a change in how future perpetrators within adolescent populations are identified through proper screening and interventions through resources within the community.

In the discussion, emphasis is placed on awareness and prevention of such violence within communities. The cornerstone for change must begin at the front lines - mental health professionals, parents, and importantly survivors within communities. In order to foster a necessary change, there must be a change in how future perpetrators within adolescent populations are identified through proper screening and interventions through resources within the community.

Case Presentation

The patient is a 15-year-old female who presented to the emergency department (ED) of the University Hospital Medical Center (UHMC) (Tamarac, FL) under the Baker Act by the police for suicidal ideation and self-harm. This is the patient’s third hospitalization within the past three months with a similar presentation. Upon admission, she reported excessive worry and anxiety associated with intrusive thoughts related to the shooting at her high school approximately nine months prior. She reported frequent nightmares of the shooter entering a building and killing multiple people. She also reported that these nightmares are now causing her to avoid familiar places (such as her school or her father's workplace) as well as other public places as they induce flashbacks and panic attacks; she has now been having thoughts and urges to self harm by cutting as well as frequent suicidal ideations due to the severity of these symptoms.

She also reported that these nightmares are now causing her to avoid familiar places (such as her school or her father's workplace) as well as other public places as they induce flashbacks and panic attacks; she has now been having thoughts and urges to self harm by cutting as well as frequent suicidal ideations due to the severity of these symptoms.

She was admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit where she was seen and assessed daily by the psychiatry team. She received individual therapy by a mental health counselor while on the unit. The therapy was centered around building coping skills. Her parents were counseled on her symptoms and family sessions were conducted by the psychiatry team to educate both the patient and her parents on diagnosis and treatment options. During family sessions, the parents expressed that they were against using medications in children. Techniques such as motivational interviewing (MI) were utilized by multiple providers such as the attending physician and resident. Her parents declined pharmacologic treatment despite MI interventions and she was discharged home with follow up in a youth Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) the following week post discharge. Youth IOP consists of therapy sessions three days a week, addressing non-pharmacological ways to address her PTSD.

Her parents declined pharmacologic treatment despite MI interventions and she was discharged home with follow up in a youth Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) the following week post discharge. Youth IOP consists of therapy sessions three days a week, addressing non-pharmacological ways to address her PTSD.

Discussion

Case-based clinical discussions: three important takeaway points

1) Media Exposure and the Effects on PTSD Related to Mass Shootings

A study conducted by the National Institute of Mental Health found that media exposure interacted with sympathetic reactivity to predict PTSD symptom onset, such that adolescents with lower levels of sympathetic reactivity developed PTSD symptoms only following high exposure to media coverage of the attack. Although this particular study is in regards to the Boston Marathon bombing, it illustrates the point that media exposure may be particularly likely to trigger PTSD symptoms in youths with exposure to violence [6].

Additional studies in the context of 9/11 terrorist attack support the notion that media exposure can trigger extreme PTSD symptomology. The study conducted by University of Toronto found that exposure to graphic media images may result in physical and psychological effects previously assumed to require direct trauma exposure [7].

A study by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) followed 66 children after a school shooting and found that the media played a role in perpetuating high levels of emotional tension in children. They found that consistent exposure to graphic content led to the formation of “malignant memories" [8].

2) Avoidance Behavior

Data collected from survivors of the Virginia Tech shooting was collected using the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II), a 7-item self-report measure of experiential avoidance. Avoidance behaviors are any action or behavior taken to prevent difficult or painful feelings. The study found that avoidance behaviors are implicated in the etiology and prolongment of post-traumatic stress symptomatology [9].

The study found that avoidance behaviors are implicated in the etiology and prolongment of post-traumatic stress symptomatology [9].

3) Delay of Disease Remission

It may be more difficult to overcome the symptoms of illness (PTSD) due to more frequent and intense triggers within the environment causing further delay of disease remission. According to the Journal of Urban Health, only about one-half of the PTSD cases identified at any time over three years were in remission at the three-year follow-up [10].

As clinicians working with PTSD adolescents, we must be cognizant of these factors as we think about prognosis and create a comprehensive treatment plan. In the figure below, we see that gun violence has been increasing, and we must be equipped to deal with the long-term sequelae of these events, given how unfortunately common they have become (Figure 1) [11].

Figure 1: Washington Post Infographic

This figure is a graphic representation/schematic by the Washington Post, designed to illustrate the occurrence of shootings and their respective scale on a timeline [11].

Given the limited amount of research conducted on gun violence [12], it is paramount for cases such as these to be documented and added to medical literature so that the rippling effects of mass shootings can be understood on a clinical level. This case study brings to our attention how complex and multifaceted treating mass shooting survivors can be. PTSD patients are exposed to their trauma differently in this day and age where social media, news outlets, and television are so pervasive. As news outlets sensationalize the reported tragedies, we must focus our attention on our patients and providing the best care and support in dealing with these factors.

Conclusions

This case study and discussion show that it is no longer a rare occurrence to have a patient who has survived a mass school shooting. As a result of this unfortunate reality, clinicians need to be able to recognize and treat symptoms of PTSD in adolescent patients. In addition to appropriate medications and psychotherapy, the clinician needs to be prepared to face barriers to remission such as re-exposure through media content. This case study also prompts physicians to recognize avoidance behaviors of such social media and news content as a manifestation of PTSD in adolescents. This case serves as an example of the long term sequelae of PTSD, and could be the springboard for further advocacy and awareness about the aftermath of school shootings.

This case study also prompts physicians to recognize avoidance behaviors of such social media and news content as a manifestation of PTSD in adolescents. This case serves as an example of the long term sequelae of PTSD, and could be the springboard for further advocacy and awareness about the aftermath of school shootings.

References

- Underlying cause of death 1999-2017. (2018). Accessed: Oct 10, 2019: https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/ucd.html.

- Katsiyannis A, Whitford DK, Ennis RP: Historical examination of united states intentional mass school shootings in the 20th and 21st centuries: implications for students, schools, and society. J Child Fam Stud. 2018, 27:2562-73. 10.1007/s10826-018-1096-2

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al.: Youth risk behavior surveillance — United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018, 67:1-114. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1

- Miron LR, Orcutt HK, Kumpula MJ: Differential predictors of transient stress versus posttraumatic stress disorder: evaluating risk following targeted mass violence.

Behav Ther. 2014, 45:791-805. 10.1016/j.beth.2014.07.005

Behav Ther. 2014, 45:791-805. 10.1016/j.beth.2014.07.005 - Novotney A: What happens to the survivors: long-term outcomes for survivors of mass shootings are improved with the help of community connections and continuing access to mental health support. APA. 2018, 49:36.

- Busso DS, McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA: Media exposure and sympathetic nervous system reactivity predict PTSD symptoms after the Boston Marathon bombings. Depress Anxiety. 2014, 31:551-558. 10.1002/da.22282

- Silver RC, Holman E, Andersen JP, Poulin M, McIntosh DN, Gil-Rivas V: Mental-and physical-health effects of acute exposure to media images of the September 11, 2001, attacks and the Iraq War. Psychol Sci. 2013, 24:1623-34. 10.1177/0956797612460406

- Schwarz ED, Kowalski JM: Malignant memories: PTSD in children and adults after a school shooting. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991, 30:936-944. 10.1097/00004583-199111000-00011

- Kumpula MJ, Orcutt HK, Bardeen JR, Varkovitzky RL: Peritraumatic dissociation and experiential avoidance as prospective predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms.

J Abnorm Psychol. 2011, 120:617-627. 10.1037/a0023927

J Abnorm Psychol. 2011, 120:617-627. 10.1037/a0023927 - North CS, McCutcheon V, Spitznagel EL, Smith EM: Three-year follow-up of survivors of a mass shooting episode. J Urban Health. 2002, 79:383-391. 10.1093/jurban/79.3.383

- Explore the Washington Post's database of school shootings. (2018). Accessed: Oct 10, 2019: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/local/school-shootings-database/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.d1b8c6eacdee.

- Kellermann AL, Rivara FP: Silencing the science on gun research. JAMA. 2013, 309:549-550. 10.1001/jama.2012.208207

Aftermath of the Parkland Shooting: A Case Report of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in an Adolescent Survivor

Author Information

Katy McLaughlin

Psychiatry, HCA East University Hospital/Nova Southeastern University, Tamarac, USA

Jeena A. Kar Corresponding Author

Medical Education and Simulation, Nova Southeastern University School of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, USA

Ethics Statement and Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following: Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work. Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work. Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following: Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work. Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work. Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Article Information

DOI

10.7759/cureus.6146

Cite this article as:

Mclaughlin K, Kar J A (November 13, 2019) Aftermath of the Parkland Shooting: A Case Report of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in an Adolescent Survivor. Cureus 11(11): e6146. doi:10.7759/cureus.6146

Publication history

Received by Cureus: November 11, 2019

Peer review began: November 11, 2019

Peer review concluded: November 11, 2019

Published: November 13, 2019

Copyright

© Copyright 2019

McLaughlin et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 3.0., which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 3.0., which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

License

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Aftermath of the Parkland Shooting: A Case Report of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in an Adolescent Survivor

Figures etc.

Figure 1: Washington Post Infographic

This figure is a graphic representation/schematic by the Washington Post, designed to illustrate the occurrence of shootings and their respective scale on a timeline [11].

Download full-size

7.3

RATED BY 3 READERS

CONTRIBUTE RATING

Scholarly Impact Quotient™ (SIQ™) is our unique post-publication peer review rating process. Learn more here.

Learn more here.

What's SIQ™?

Scholarly Impact Quotient™ (SIQ™) is our unique post-publication peer review rating process. SIQ™ assesses article importance and quality by embracing the collective intelligence of the Cureus community-at-large. All registered users are invited to contribute to the SIQ™ of any published article. (Authors cannot rate their own articles.)

High ratings should be reserved for work that is truly groundbreaking in its respective field. Anything above 5 should be considered above average. While all registered Cureus users can rate any published article, the opinion of domain experts is weighted appreciably more than that of non-specialists. An article’s SIQ™ will appear alongside the article after being rated twice and is recalculated with each additional rating.

Visit our SIQ™ page to find out more.

Close

Scholarly Impact Quotient™ (SIQ™)

Scholarly Impact Quotient™ (SIQ™) is our unique post-publication peer review rating process. SIQ™ assesses article importance and quality by embracing the collective intelligence of the Cureus community-at-large. All registered users are invited to contribute to the SIQ™ of any published article. (Authors cannot rate their own articles.)

SIQ™ assesses article importance and quality by embracing the collective intelligence of the Cureus community-at-large. All registered users are invited to contribute to the SIQ™ of any published article. (Authors cannot rate their own articles.)

Already have an account? Sign in.

Enter your email address to receive your free PDF download.

Please note that by doing so you agree to be added to our monthly email newsletter distribution list.

PTSD

") end if %>

Variant of Acrobat Samana Gaze | Acrobat Reader Samana Download

PTSD is a normal response

for severe traumatic events.

This booklet deals with signs,

symptoms and treatments for PTSD.

New York State

Department of Mental Health

Have you experienced a terrible and dangerous event? Note please, those cases in which you recognize yourself.

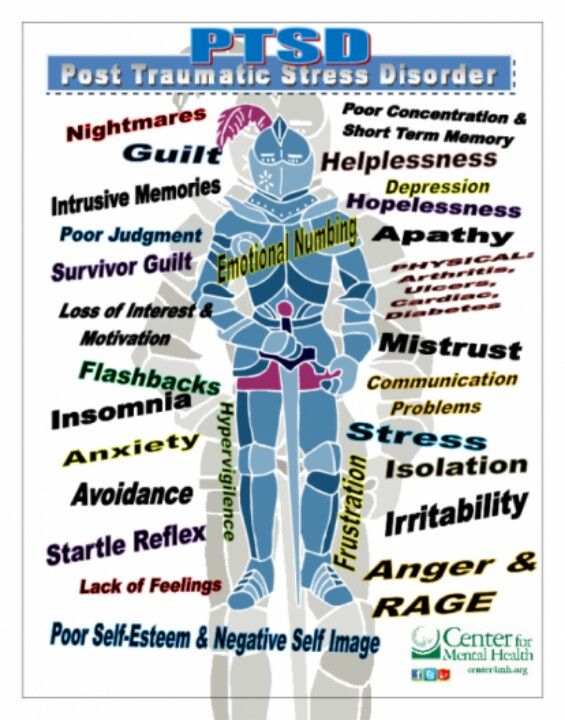

- Sometimes, out of the blue, everything that happened to me is happening again. I never know when to expect it again.

- I have nightmares and memories of the terrible incident which I have experienced.

- I avoid places that remind me of that incident.

- I jump on the spot and feel uneasy at any sudden movement or surprise. I feel alert all the time.

- It's hard for me to trust someone and get close to someone.

- Sometimes I just feel emotionally drained and deaf.

- I get angry very easily.

- I am tormented by guilt that others died, but I survived.

- I sleep poorly and experience muscle tension.

PTSD is a very serious condition that needs to be treated.

Many people who have experienced terrible events suffer from this disease.

It is not your fault that you fell ill, and you should not suffer from it.

Read this booklet to find out how you can be helped.

You can get well and enjoy life again!

What is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD/PTSD)?

PTSD is a very serious condition. PTSD symptoms may occur in a person who has experienced a terrible traumatic event. This disease is susceptible medical and therapeutic treatment.

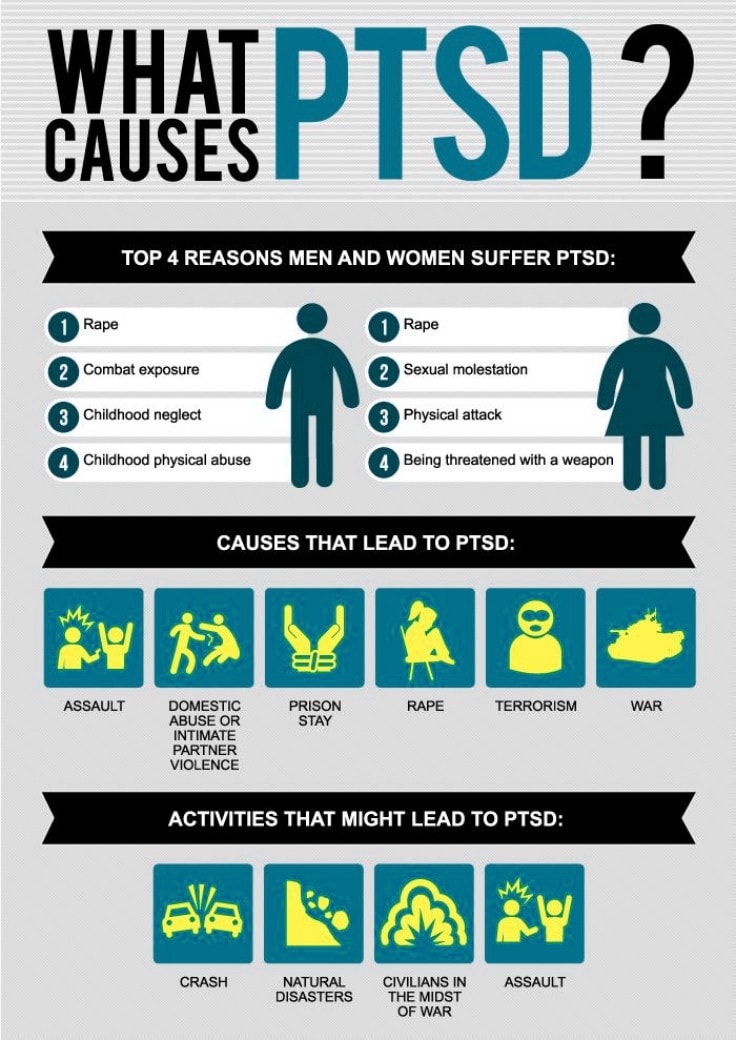

PTSD can occur after you:

- Have been a victim of sexual abuse

- Have been a victim of physical or emotional domestic violence

- Victim of a violent crime

- Been in a car accident or plane crash

- Survived a hurricane, tornado, or fire

- Were at war

- Survived a life-threatening event

- Witnessed any of the above events

If you have post-traumatic stress disorder, you often have nightmares or memories associated with the event. you try to hold on away from anything that might remind you of the experience.

You are bitter and unable to trust or care for others. You are always on your guard and see a hidden threat in everything. You become not by itself, when something happens suddenly and without warning.

You are always on your guard and see a hidden threat in everything. You become not by itself, when something happens suddenly and without warning.

When does PTSD start and how long does it last?

In most cases, post-traumatic stress manifests itself approximately three months after the traumatic event. In some cases, signs Post-traumatic stress symptoms only show up years later. Post-traumatic Stress affects people of all ages. Even children are not immune from it.

Some get better after six months, others may suffer from it illness for much longer.

Am I the only one with this disease?

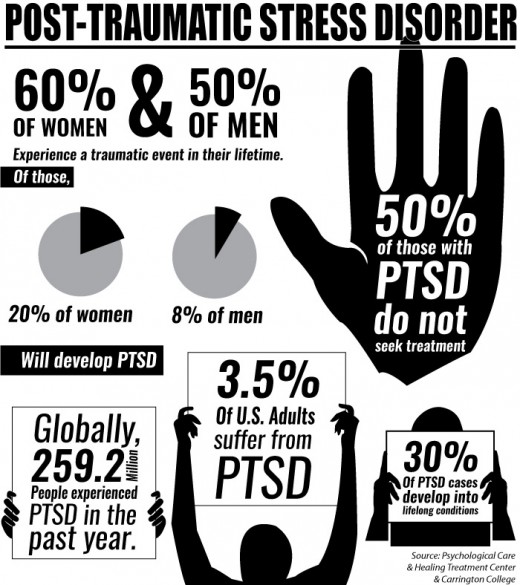

No, you are not alone. Every year, 5.2 million Americans suffer from PTSD.

Women suffer from this disease two and a half times more often than men. The most common traumatic events that cause PTSD in men are: rape, participation in hostilities, abandonment and abuse in childhood. The most traumatic events in women are rape, sexual molestation, physical assault, threat weapons and childhood abuse.

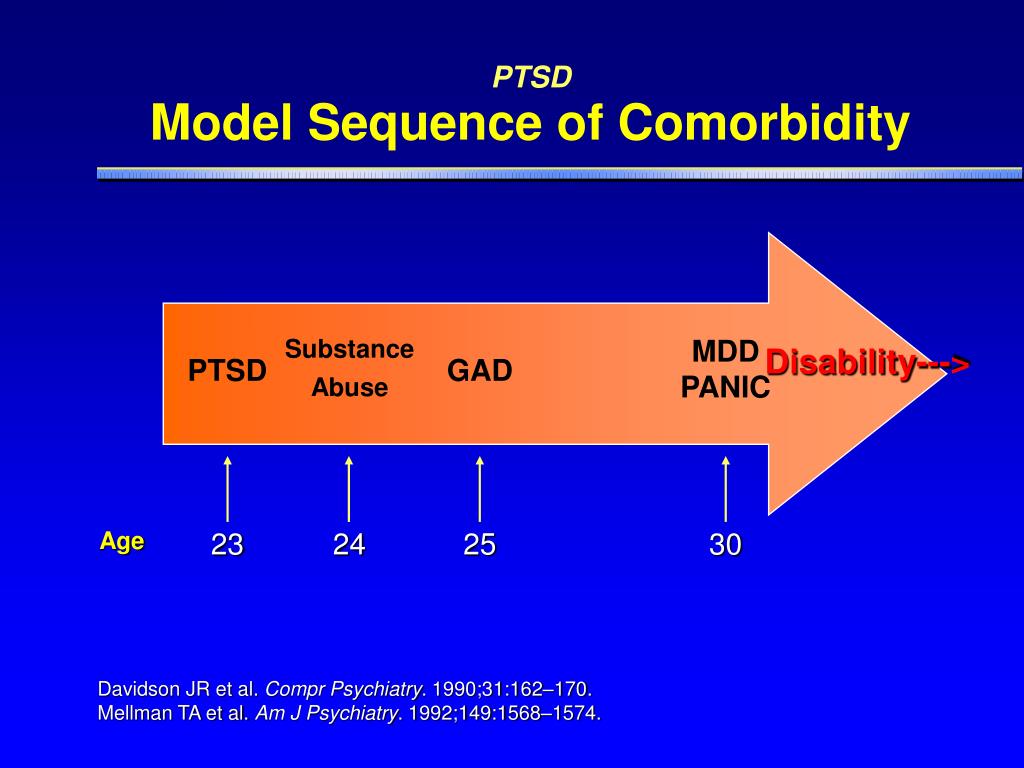

What other conditions can accompany PTSD?

Common depression, alcoholism and drug addiction, or other anxiety disorders. The likelihood of successful treatment increases if these comorbidities to identify and treat in time.

Frequent headaches, gastroenterological problems, problems with the immune system, dizziness, chest pain or discomfort in other parts of the body. It often happens that a doctor treats physical symptoms, unaware that their cause lies in PTSD.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) recommends therapists to learn from patients about experiences of violence, recent losses and traumatic events, especially when symptoms persist are returning. After diagnosing PTSD, it is recommended to refer patient to a mental health specialist who has experience in the treatment of patients with PTSD.

What should I do to help myself in this situation?

Talk to your doctor and tell him about your experience, and how you feel. If you are visited by terrible memories, overcomes depression and sadness if you have trouble sleeping and constantly embittered - you should tell your doctor about all this. Tell him Are any of these conditions preventing you from doing your daily activities? lead a normal life. You may want to show this booklet to your doctor. This may help explain to him how you feel. Ask your doctor examine you to make sure there are no physical illnesses.

If you are visited by terrible memories, overcomes depression and sadness if you have trouble sleeping and constantly embittered - you should tell your doctor about all this. Tell him Are any of these conditions preventing you from doing your daily activities? lead a normal life. You may want to show this booklet to your doctor. This may help explain to him how you feel. Ask your doctor examine you to make sure there are no physical illnesses.

Ask your doctor if he has had patients with post-traumatic stress. If your doctor does not have a special preparation, ask him for directions to doctor with relevant experience.

How can a doctor or psychotherapist help me?

Your doctor may prescribe medicine to help reduce your fear or tension. However, it should be borne in mind that usually several weeks before the medicine starts to work.

Many PTSD sufferers benefit from talking with a professional or other people who have experienced traumatic events. This is called "therapy". Therapy will help you get over your nightmare.

This is called "therapy". Therapy will help you get over your nightmare.

One man's story:

"After I was attacked, I He constantly felt fear and depression, became irritable. I couldn't sleep well and lost my appetite. Even when I tried not think about what happened, I was still tormented nightmares and terrible memories.

“I was completely at a loss and didn't know what to do. one buddy advised to see a doctor. My doctor helped me find a specialist in post-traumatic stress."

“I needed a lot of strength, but after medication and a course of therapy, I gradually come to my senses. It’s good that I called my doctor then.”

PTSD and the military

If you are in the military, you have probably been in combat. You, probably got into terrible and life-threatening situations. They shot at you you have seen your friend shot, you have seen death. experienced you events can cause PTSD.

Experts say that PTSD occurs:

- Nearly 30% of Vietnam War veterans

- Nearly 10% of Gulf War veterans (Operation Desert Storm)

- Almost 25% of veterans of the war in Afghanistan (operations "Introducing freedom") and veterans of the war in Iraq (operations "Iraqi Freedom")

Other factors of the military situation can serve as an additional stress to and so stressful situation and can contribute to the development of PTSD and other mental problems. Among these factors are the following: your military specialty, the political aspects of the war, where the battle takes place and who your enemy is.

Another reason that contributes to PTSD in military personnel can be Military Sexual Assault (MST) – any form of sexual harassment or sexual abuse while serving in the military. MST can happen with men and women, and can occur in peacetime, during war training or during the war.

Veterans Affairs (VA) health care approximately:

- 23 out of 100 women (23%) report sexual violence during military service

- 55 out of 100 women (55%) and 38 out of 100 men (38%) were exposed to sexual harassment while serving in the army

Although the trauma of sexual assault is more common in the military among women, more than half of veterans who have experienced sexual trauma violence in the army - it's men.

Remember, you can get the help you need right now:

Tell your doctor about your experience and how you feel. If your doctor does not have special training in the treatment of PTSD, ask him for a referral to a doctor who has relevant experience.

PTSD research

To help those suffering from PTSD, the National Institute of Conservation Mental Health (NIMH) supports research into the study of PTSD, as well as other thematically related to PTSD research on problems anxiety and fear. The challenge for research is to find new ways to help people cope with trauma, as well as find new treatment options and, The main thing is to prevent disease.

Research on possible risk factors for PTSD

Today, the attention of many scientists is focused on genes that play a role in having terrible memories. Understanding the mechanism of "creation" of scary memories can help improve or find new ways to alleviate symptoms of PTSD. For example, PTSD researchers have identified genes that are responsible for:

For example, PTSD researchers have identified genes that are responsible for:

Statmin is a protein involved in the formation of terrible memories. During one experiment, mice were placed in environment designed to instill fear in them. In this situation mice lacking the statmin gene, in contrast to normal mice were less likely to "freeze" - i.e. exercise natural defensive response to danger. Also in the environment designed to evoke innate fear in them, they demonstrated it to a lesser extent than normal mice, more willingly mastering the open "dangerous" space. 1

GRP (gastrin-releasing peptide/GRP) - signal substance brain released during emotional events. At in mice, GWP helps control the fear response, and lack of GWP can lead to a longer memory of fear. 2

Scientists have also discovered a variant of the 5-HTTLPR gene that controls serotonin (a brain substance associated with mood), which, as it turns out, feeds the fear response. 3 It seems that, like in the case of other mental disorders, in the development of PTSD different genes are involved, each of which contributes to the formation of the disease.

3 It seems that, like in the case of other mental disorders, in the development of PTSD different genes are involved, each of which contributes to the formation of the disease.

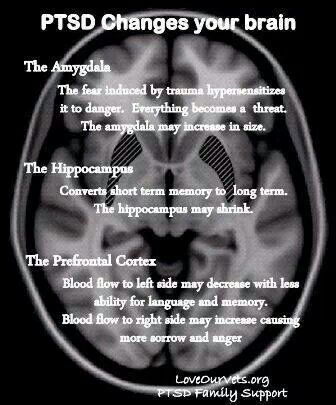

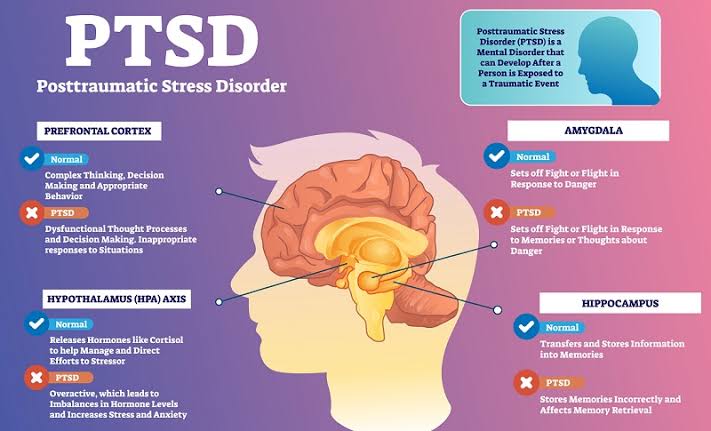

Understanding the causes of PTSD can also be helped by studying different areas brain responsible for fear and stress. One of these areas is cerebellar amygdala, responsible for emotions, learning and memory. It turned out that she plays an active role in the emergence of fear (or other words, "teaches" to be afraid of something, for example, to touch a hot stove), as well as in the early phases of fear repayment (or in other words, "teaches" Do not be scared). 4

The retention of faded memories and the weakening of the initial fear reaction are associated with the prefrontal cortex (PFC / PFC) of the brain, 4 responsible for decision making, problem solving and situation assessment. Each zone PFC has its own role. For example, when the PFC believes that a stressor is amenable to control, the medial prefrontal zone of the PFC suppresses the anxiety center deeply in the brainstem and controls the response to stress. 5 Ventromedial PFC helps maintain long-term fading of fearful memories, and her ability to perform this feature can be affected by its size. 6

For example, when the PFC believes that a stressor is amenable to control, the medial prefrontal zone of the PFC suppresses the anxiety center deeply in the brainstem and controls the response to stress. 5 Ventromedial PFC helps maintain long-term fading of fearful memories, and her ability to perform this feature can be affected by its size. 6

Individual differences in genes or characteristics of regions of the brain brain can only set the stage for PTSD, but by themselves do not cause no symptoms. environmental factors such as childhood trauma, head trauma or mental illness in family, favor the development of the disease and increase the risk of disease, affecting the brain in the early stages of its growth. 7 Except In addition, how people adapt to trauma is likely to be influenced by and characteristics of character and behavior, such as optimism and a tendency to consider problems in a positive or negative way, as well as social factors such as availability and use of social support. 8 Further research may show what combination of these factors or what other factors will allow ever predict who has a traumatic event cause PTSD, and who doesn't.

8 Further research may show what combination of these factors or what other factors will allow ever predict who has a traumatic event cause PTSD, and who doesn't.

PTSD research

Currently, psychotherapy is used in the treatment of PTSD ("talk" therapy), drugs or drug-therapeutic combination.

Psychotherapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) helps you learn differently think and react to frightening events that are the impetus for development PTSD, and can help bring the symptoms of the disease under control. There are several types cognitive behavioral therapy, including:

"Push" method - uses mental images, notes or visiting a place experienced trauma to help those affected face the overwhelming their fear and take control of it.

Behavior restructuring (cognitive restructuring) - encourages survivors of a traumatic event express depressing (often erroneous) thoughts about experienced trauma, challenge these thoughts and replace them with more balanced and appropriate.

Implementation in a stressful situation - teaches ways to reduce anxiety and the ability to cope with it, helping to reduce the symptoms of PTSD, and helps to correct the erroneous train of thought associated with the trauma experienced. NIMH is currently conducting research to study the reaction brain response to cognitive behavioral therapy versus response sertraline (Zoloft) - one of two drugs recommended and approved US Food and Drug Administration funds (FDA) for the treatment of post-traumatic stress. This research may help find out why some people respond better to medications, and others for psychotherapy

Drugs

Recently, in a small study, NIMH scientists found that if patients who are already taking a dose of prazosin (Minipress) at bedtime, add a daily dose, then this weakens the general symptoms of PTSD and stress reaction to reminders of the trauma experienced. 9

Another drug of interest is D-cycloserine (Seromycin), which increases the activity of a brain substance called N-methyl-D-aspartate, needed to pay off fear. During the study, which was attended by 28 people suffering from a fear of heights, scientists found that patients who received "push" therapy before a session D-cycloserine, showed lower levels of fear during the session compared to those who did not receive the drug. 10 Currently scientists study the effectiveness of the combined use of D-cycloserine and therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress.

During the study, which was attended by 28 people suffering from a fear of heights, scientists found that patients who received "push" therapy before a session D-cycloserine, showed lower levels of fear during the session compared to those who did not receive the drug. 10 Currently scientists study the effectiveness of the combined use of D-cycloserine and therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress.

Propranolol (Inderal), a beta-blocker drug, also under study whether it can be used to reduce post-traumatic stress and break the chain of scary memories. First experiments gave consoling results: it was possible to successfully weaken and, it seems, prevent PTSD in a small number of victims of traumatic events. 11

For example, in one preliminary study, scientists created a website self-help, based on the use of a psychotherapeutic method implementation in a stressful situation. First, patients with PTSD meet in person with doctor. After this meeting, participants can go to the site to find more information about PTSD and how to deal with the problem; their doctors may also visit the site to give advice or briefing. In general, scientists believe that therapy in this form - promising treatment for a large number of people suffering from PTSD. 12

First, patients with PTSD meet in person with doctor. After this meeting, participants can go to the site to find more information about PTSD and how to deal with the problem; their doctors may also visit the site to give advice or briefing. In general, scientists believe that therapy in this form - promising treatment for a large number of people suffering from PTSD. 12

Scientists are also working to improve methods for testing early treatment and monitoring of survivors of massive trauma, on developing ways to teach them self-assessment skills and introspection and referral mechanism to psychiatrists (if necessary).

Prospects for PTSD research

In the last decade, rapid progress in the study of mental and biological PTSD has led scientists to conclude that there is a need to focus on prevention, as the most realistic and important goal.

For example, in order to find ways to prevent PTSD, with funding NIMH conducts research to develop new and orphan drugs, aimed at combating the underlying causes of the disease. During another research scientists are looking for ways to enhance behavioral, personality and social protective factors and minimizing risk factors for prevent the development of PTSD after trauma. Another study is studying the question of what factors influence the difference in response to one or another method of treatment, which will help in the development of more individual, effective and productive methods of treatment.

During another research scientists are looking for ways to enhance behavioral, personality and social protective factors and minimizing risk factors for prevent the development of PTSD after trauma. Another study is studying the question of what factors influence the difference in response to one or another method of treatment, which will help in the development of more individual, effective and productive methods of treatment.

Where can I find more information?

MedlinePlus - resource from the American National Library of Medicine (U.S. National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health) - offers the latest information on many health issues. Information about You can find PTSD at: www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/posttraumaticstressdisorder.html.

National Institute of Mental Health

Office of Science Policy, Planning, and Communications

[National Institute of Mental Health

Science Policy Division research, planning and communications]

6001 Executive Boulevard

Room 8184, MSC 9663

Bethesda, MD 20892-9663

Phone: 301-443-4513; Fax: 301-443-4279

fax answering system Free answering machine: 1-866-615-NIMH (6464)

Text phone: 1-866-415-8051 toll-free

Email: nimhinfo@nih. gov

gov

National Center for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

[National PTSD Center]

VA Medical Center (116D)

215 North Main Street

White River Junction, VT 05009

802-296-6300

www.ncptsd.va.gov

NOTES

- Shumyatsky GP, Malleret G, Shin RM, et al. Stathmin, a Gene Enriched in the Amygdala, Controls Both Learned and Innate Fear. cell. Nov 18 2005;123(4):697-709.

- Shumyatsky GP, Tsvetkov E, Malleret G, et al. Identification of a signal network in lateral nucleus of amygdala important for inhibiting memory specifically related to learned fear. cell. Dec 13 2002;111(6):905-918.

- Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, et al. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala.Science. Jul 192002;297(5580):400-403.

- Milad MR, Quirk GJ. Neurons in medial prefrontal cortex signal memory for fear extinction.

Nature. Nov 7 2002;420(6911):70-74.

Nature. Nov 7 2002;420(6911):70-74. - 5 Amat J, Baratta MV, Paul E, Bland ST, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Medial prefrontal cortex determines how stressor controllability affects behavior and dorsal raphe nucleus. Nat Neurosci. Mar 2005;8(3):365-371.

- Milad MR, Quinn BT, Pitman RK, Orr SP, Fischl B, Rauch SL. Thickness of ventromedial prefrontal cortex in humans is correlated with extinction memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. Jul 26 2005;102(30):10706-10711.

- Gurvits TV, Gilbertson MW, Lasko NB, et al. Neurological soft signs in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder.Arch Gen Psychiatry. Feb 2000;57(2):181-186.

- Brewin CR. Risk factor effect sizes in PTSD: what this means for intervention. J Trauma Dissociation. 2005;6(2):123-130.

- Taylor FB, Lowe K, Thompson C, et al. Daytime Prazosin Reduces Psychological Distress toTrauma Specific Cues in Civilian Trauma Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Biol Psychiatry. Feb 3 2006.

Biol Psychiatry. Feb 3 2006. - Ressler KJ, Rothbaum BO, Tannenbaum L, et al. Cognitive enhancers as adjuncts to psychotherapy: use of D-cycloserine in phobic individuals to facilitate extinction of fear. Arch Gen Psychiatry. Nov 2004;61(11):1136-1144.

- Pitman RK, Sanders KM, Zusman RM, et al. Pilot study of secondary prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder with propranolol.Biol Psychiatry. Jan 15 2002;51(2):189-192.

- Litz BTWL, Wang J, Bryant R, Engel CC.A therapist-assisted Internet self-help program for traumatic stress. Prof Psychol Res Pr. December 2004;35(6):628-634.

New York State Department of Mental Health expresses thanks to the National Institute of Mental Health for the information, used in this booklet.

Published by the State Department of Mental Health New York, June 2008.

New York State

Andrew M. Cuomo Governor

Mental Health

Head of Department Michael F. Hogan, PhD

Hogan, PhD

For more information about this edition contact:

New York State Office of Mental Health

Community Outreach and Public Education Office

[New York State Division of Mental Health

Public Relations and Community Education Department]

44 Holland Avenue

Albany, NY 12229

866-270-9857 (toll free)

www.omh.ny.gov

For questions and complaints about mental health services Health in New York contact:

New York State Office of Mental Health

Customer Relations

[New York State Division of Mental Health

Customer Service ]

44 Holland Avenue

Albany, NY 12229

800-597-8481 (toll-free)

For information about mental health services in your neighborhood, contact

nearest New York State Department of Mental Health (NYSOMH) regional office:

Western New York Field Office

[Western New York Regional Office]

737 Delaware Avenue, Suite 200

Buffalo, NY 14209

(716) 885-4219

Central New York Field Office

[Central New York Regional Office]

545 Cedar Street, 2nd Floor

Syracuse, NY 13210-2319

(315) 426-3930

Hudson River Field Office

[Hudson River Regional Office]

4 Jefferson Plaza, 3rd Floor

Poughkeepsie, NY 12601

(845) 454-8229

Long Island Field Office

[Long Island Regional Office]

998 Crooked Hill Road, Building #45-3

West Brentwood, NY 11717-1087

(631) 761-2508

New York City Field Office

[NYC Regional Office]

330 Fifth Avenue, 9th Floor

New York, NY 10001-3101

(212) 330-1671

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | English translation

However, most people realize what has happened after a few weeks, sometimes a little longer, and then their symptoms will begin to disappear.

Research shows that certain groups of people are at increased risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder. The risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder is reduced when a person has:

Any traumatic event can cause PTSD, although the more severe the shock, the more likely it is to develop PTSD. For example, PTSD is more likely to develop if the event:

- is sudden and unexpected

- lasts for a long time

- happens when you are caught in a trap that you cannot get out of

- was caused by people

- causes a lot of death

- causes injury

- includes children

If you are still stressed and in an uncertain state, it will be difficult to get rid of the symptoms of PTSD.

How do I know that I have overcome a traumatic experience?

You may have already gotten over the traumatic event if you can:

- think about it without worrying

- not feel like you are under constant threat

- not think about it all the time

Why is PTSD not always diagnosed?

There are a number of reasons why a person with PTSD may not be diagnosed.

Stigma and misunderstanding

People with PTSD often avoid talking about their feelings to avoid thinking about the traumatic event.

Some people believe that the symptoms they are experiencing (such as avoidance or emotional numbness) help them cope and do not realize that they are caused by PTSD.

When people are very ill, it is difficult for them to believe that they are able to feel the way they did before the traumatic event. This may discourage them from getting help.

There is also a common misconception that only military personnel suffer from PTSD. In fact, PTSD can happen to anyone, and any experience of PTSD is real.

Misdiagnosis

Some people with PTSD may be misdiagnosed with conditions such as anxiety or depression. Some people have other mental and physical health problems that make PTSD go unnoticed.

They may also experience medically unexplained symptoms such as:

- gastrointestinal disorders

- pain syndromes

- headaches

These symptoms may mean that their PTSD goes unnoticed.

Other difficulties

Some people with PTSD may also have other problems, such as difficulties in human relationships or addiction to alcohol and drugs. They may be caused by post-traumatic stress disorder, but these problems will manifest themselves more clearly than PTSD itself.

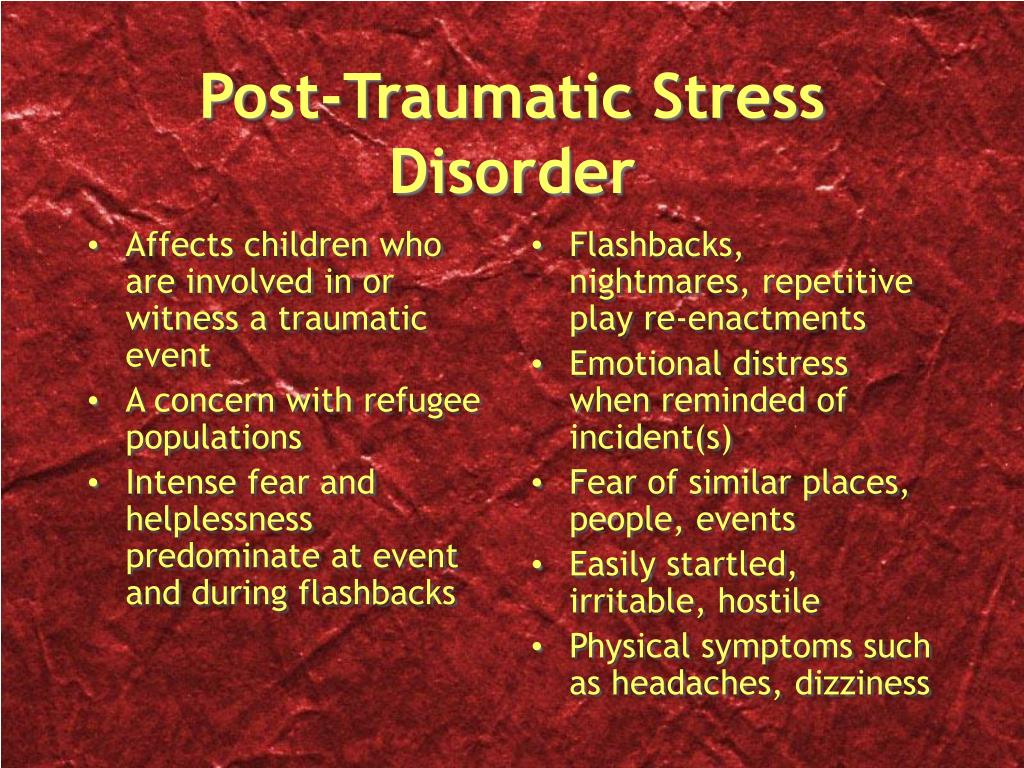

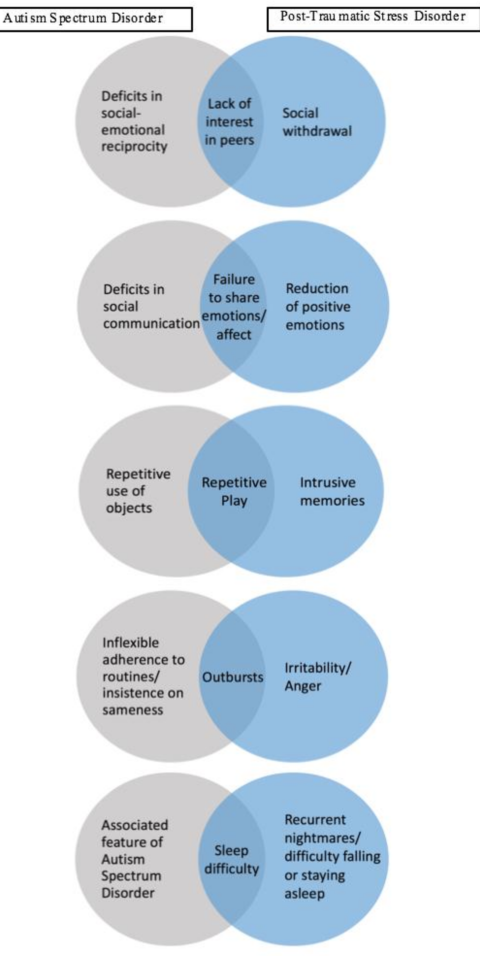

Can children develop PTSD?

PTSD can develop at any age. In addition to the symptoms of PTSD common to adults, children may also experience:

- Nightmares - In children, these dreams may or may not reflect an actual traumatic event.

- Repetitive play - some children act out a traumatic event during play. For example, a child who has been in a serious traffic accident may recreate the accident with toy cars.

- Physical symptoms - they may complain of abdominal pain and headaches.

- Fear of imminent death - they may find it hard to believe that they will live long enough to become adults.

What are the treatments for PTSD?

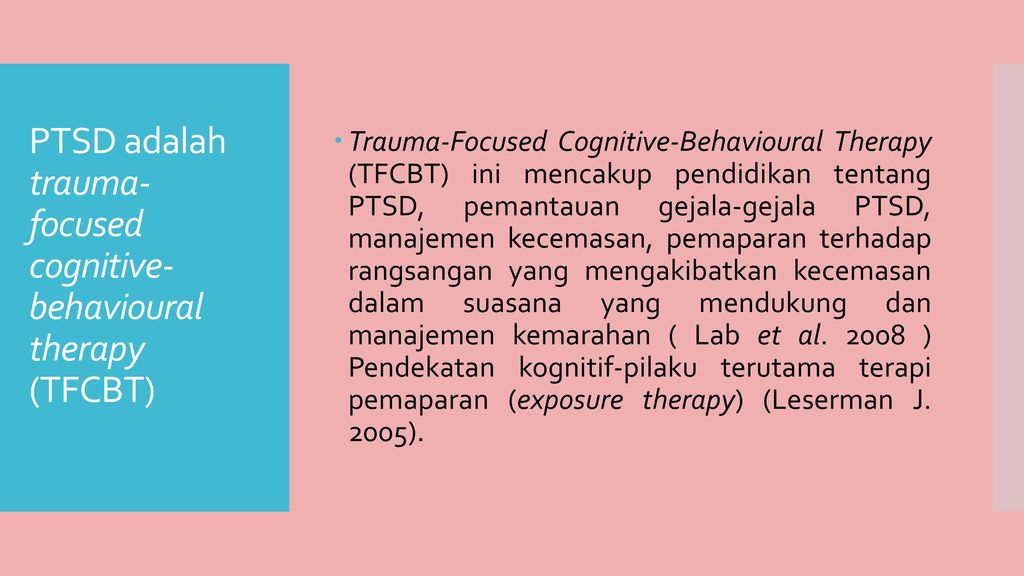

There are a number of different treatments for PTSD, including trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT), eye movement desensitization and processing (EMDR), and medications.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy for PTSD will focus on the traumatic experience, not your past life. They will help you with the following:

- Acceptance - learn to accept the fact that although you cannot change what happened, you can think differently about the event, the world around you and your life.

- Remembrance of the event - remembering what happened, you will not feel fear or anxiety. You will be able to think about what happened when you yourself want it, and not through obsessive thoughts or memories.

- Explaining your experiences in words - by saying out loud what happened, your mind will be able to push the memories away and do other things.

- Finding a sense of security - helps you better control your feelings. This will make you feel more secure and eliminate the need to avoid memories.

All psychotherapy must be administered by a properly trained and accredited professional. Sessions are usually conducted by the same therapist at least once a week, with a total duration of at least 8-12 weeks.

Sessions usually last about an hour, sometimes they can last up to 90 minutes.

Therapy for PTSD includes:

Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

A form of talking therapy that can help you change the way you think. Over time, this can help you feel better and behave differently. It is usually done individually, although there is evidence that CBT for trauma can also be done in groups.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

A technique that uses eye movements to help the brain process traumatic memories.

You will be asked to remember the traumatic event and what it made you think and feel. While you do this, you will be prompted to move your eyes or receive other "two-way stimulation" such as tapping your hand. It turns out that this reduces the emotional burden experienced in connection with the traumatic memory and helps to cope with the trauma.

GERD must be carried out by a qualified person. EPDH usually requires 8-12 sessions, lasting from 60 to 90 minutes.

Some other forms of talking therapy may be useful for treating certain symptoms (eg, poor sleep) in people for whom EMRT or CBT have not been effective for trauma.

Medications

If you have tried various treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder and find that they do not work for you, your doctor may prescribe antidepressants.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are antidepressants that can help reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. They can also help you if you are suffering from depression.

If SSRIs are not working for you, you may be offered other drugs, but this should usually be done on the advice of a mental health professional.

Which treatment is more effective?

There is evidence that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Trauma and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing are the best first line treatments. Medication can help those who refuse talking therapy or cannot easily access it.

Which treatment should I take first?

Trauma-focused psychological therapy (TF-CBT or EMBT) should be offered prior to medication, to the extent possible. This is in line with the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines.

How can I help myself?

There are some things you can do to help you get better if you develop PTSD. Your therapist will help with this and make sure you apply them in a timely manner:

Stick to your daily routine - As far as possible, try to return to or maintain your normal daily routine. By continuing to lead a life as normal as possible, you can gain a sense of support.

By continuing to lead a life as normal as possible, you can gain a sense of support.

Talk to someone you trust - Although you shouldn't feel like you need to talk to everyone about what happened, talking to someone you trust can help you sort out your feelings in a safe environment. It can also help to talk to someone who has gone through the same thing as you, or someone who has gone through something similar before, as long as it doesn't hurt you.

Try relaxation exercises - Try self meditation and other relaxation exercises. Relaxing with PTSD can be challenging, so talk to your therapist about exercises or activities that can help you.

Return to work or school - if you feel empowered, it can help you return to work, school or university by giving you a sense of routine. However, you should try to avoid situations in which you may be subjected to further injury or severe stress. It is usually best to work in a supportive, low-stress environment before starting treatment.

It is usually best to work in a supportive, low-stress environment before starting treatment.

Eat and exercise regularly - Try to eat at regular times, even if you don't feel hungry. If you feel fit, try to exercise regularly. It can also help you feel tired before bed.

Spend time with others - Spending time with the people you care about will help you feel supported.

Expect to get better - Concentrating on thoughts that you will feel better over time will be useful for your recovery. Remember that you should not strain yourself in an attempt to recover faster.

Go back to where the traumatic event happened - If you feel you can do it, you may want to go back to where the traumatic event happened. Talk to your therapist or doctor if you are considering this so they can support you through this step.

There are also some things you should avoid while recovering. However, doing the "right things" can be very difficult, and you shouldn't feel guilty if you find yourself doing any of the following:

However, doing the "right things" can be very difficult, and you shouldn't feel guilty if you find yourself doing any of the following:

Self-criticism - PTSD symptoms are not a sign of weakness. This is a normal reaction to violent experiences.

Keep your feelings to yourself. If you have PTSD, don't feel guilty about sharing your thoughts and feelings with others. Talking about how you are feeling can help your recovery.

Expect everything to go back to normal quickly - PTSD may take some time to heal. Try not to demand too much of yourself in a short amount of time.

Stay away from other people. Spending a lot of time alone can increase your sense of isolation and make you feel less well.

Drink alcohol or smoke. Although alcohol can help you relax, and coffee and nicotine can act as stimulants, they can make you feel worse over time if you experience symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Overwork. Post-traumatic stress disorder can make it difficult to sleep, but as much as possible, try to stick to your normal sleep patterns and stay up late, as this can make you feel worse. You can learn more about good sleep in our resource.

Finally, you should be careful while driving. After a traumatic episode, people may have more accidents.

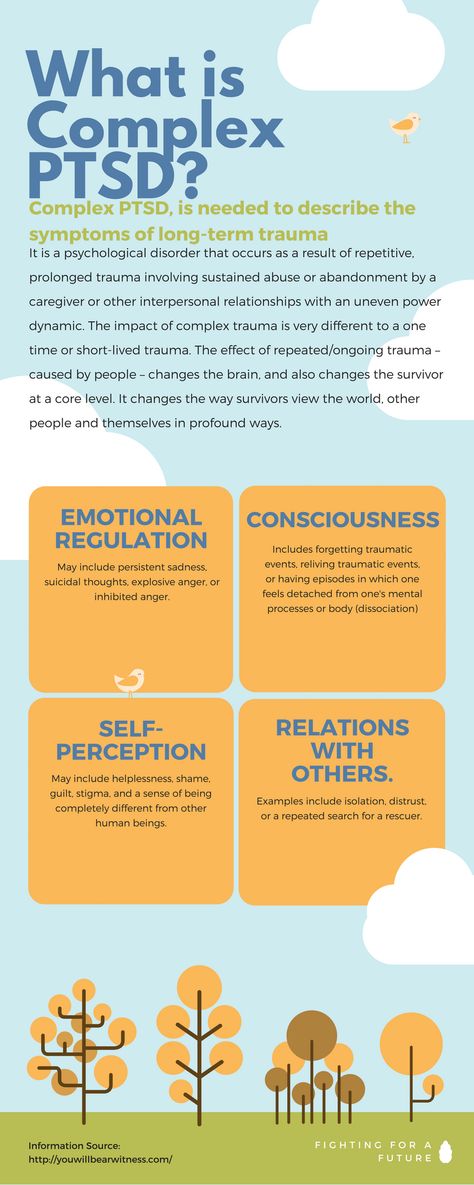

What is complex PTSD?

Some people develop complex post-traumatic stress disorder, caused by an experience or series of events that is extremely threatening or terrifying. These events can occur in childhood or adulthood.

Often such events are difficult or impossible to avoid. For example:

- torture

- slavery

- genocide

- living in war zones

- continuous domestic violence

- repeated sexual and physical abuse

In addition to PTSD symptoms, people with complex PTSD may also:

- emotions and emotional reactions

- have difficulty maintaining relationships and feelings of closeness with other people

How do I recover from complex PTSD?

People with complex post-traumatic stress disorder are characterized by a lack of trust in other people and in the world at large.

Emotional stabilization

During the stabilization phase, you will learn to trust your therapist and to understand and manage feelings of distress and alienation.

As part of stabilization, you can familiarize yourself with the work with supports - "grounding techniques". This can help you focus on familiar physical sensations and remind you that you are living in the present, not the past.

Stabilization can help you "disconnect" your feelings of fear and anxiety from the memories and the emotions they evoke, helping to make those memories less frightening.

The goal of stabilization is so that you can eventually live your life free from anxiety or memories.

Sometimes stabilization may be the only help needed.

Trauma-focused therapy

Trauma-focused therapy, including EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Processing) or trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, can help you deal with traumatic experiences. Other types of psychotherapy, including psychodynamic psychotherapy, may also be helpful. For complex post-traumatic stress disorder, care must be taken as these treatments can make things worse if not used properly.

Other types of psychotherapy, including psychodynamic psychotherapy, may also be helpful. For complex post-traumatic stress disorder, care must be taken as these treatments can make things worse if not used properly.

Reintegration and recovery

Reintegration into your normal life can help you adjust to the real world at a time when you have emerged from the dangerous situation you were in before. This can help you begin to see yourself as a person with a choice.

Reintegration can help you:

- be compassionate towards yourself and others

- restore trust in yourself and others

- renew friendships, intimate relationships, and activities that promote your health and well-being

Medications

As with PTSD, antidepressants or other medications may be used along with psychotherapy. Medication may also be used if psychotherapy does not help or is not available to you. It would also be helpful to have a mental health professional help you oversee your medication.

Self Help

If you develop complex PTSD, it may be helpful to try to do ordinary things that have nothing to do with your past traumatic experience.

They can include:

- To make friends

- get a job

- to engage regular physical exercises

- Learn to relax

- Find the hobby

- To start homemade

These things can help you allerately start the world around you . However, this can take time, and there is no need to be ashamed that at first these things will seem difficult to you or you will not be able to do them right away.

How do you know if someone has PTSD?

If you know someone who has just experienced a traumatic event, there are a few things you should be aware of. These moments may be signs that a person is not coping:

- Changes in behavior - low productivity at work, lateness, sick leave, minor accidents.

- Changes in emotions - anger, irritability, depression, lack of interest and lack of concentration.

- Changes in thought - preoccupation with threats or fears, negative outlook on the future

- Unexpected physical symptoms such as shortness of breath, nervousness or abdominal pain.

If you think a person may be showing signs of PTSD, you can suggest that they talk to their doctor. If you don't feel close enough to him for such a recommendation, talk to someone in his family or friends who could do it for you.

They may also find it helpful to refer to information about PTSD, such as this resource, to help identify the difficulties they face.

How can I help someone who has experienced a traumatic event?

For those who have experienced a traumatic event, the following may help:

- Be there - invite people to be with them. If they refuse, you can reassure them that you will be with them if they change their mind. Should not be imposed, but try to convince them to accept your help.

- Listen - try not to pressure people if they don't want something. If they want to talk, try to listen without interrupting or trying to share your own experience with them.

- Ask general questions - When you ask questions, try to keep them general and non-judgmental. For example, you might ask, "Have you talked about this with anyone else?" or “Can I help you find more help?”

- Offer real (practical) help - Some people may have difficulty taking care of themselves or doing daily activities. Offer help, such as cleaning the house or preparing meals;

Try not to tell people:

- That you know how they feel - even if you have experienced something like this, people experience situations differently. Comparing your experience with that of others is not always helpful;

- How lucky they are to be alive - people who have experienced traumatic events often don't think they are "lucky".