Is social communication disorder autism

The Difference Between Autism & Social Communication Disorder (SCD)

Posted on June 5, 2018 by SDCAadmin

Has your child been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), or does he or she exhibit symptoms of autism? Before seeking autism-specific assistance, make sure the diagnosis is correct.

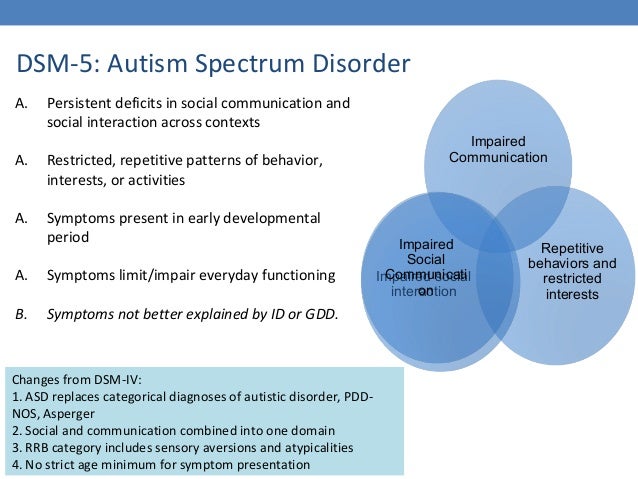

You may learn that your child has Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder (SCD). Recently added to the most current, fifth-edition of the DSM (Diagnosis and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), the signs and symptoms of ASD are very similar – and even overlap – with those of social pragmatic communication disorder, even though the two conditions are different.

Since the newest edition of the DSM-5, field tests show that some children who were diagnosed with ASD via the parameters of the older-edition of DSM-4 would now be diagnosed with SCD as a result of the new criteria.

If your child does not have a diagnosis yet or was diagnosed with ASD based on the 4th-edition of the DSM, it may be worthwhile to schedule a consultation with a licensed speech-language pathologist who is trained to identify the difference.

Speech-language pathologists are available at most medical centers or your physician can refer you to a reputable center or clinic for an accurate diagnosis.

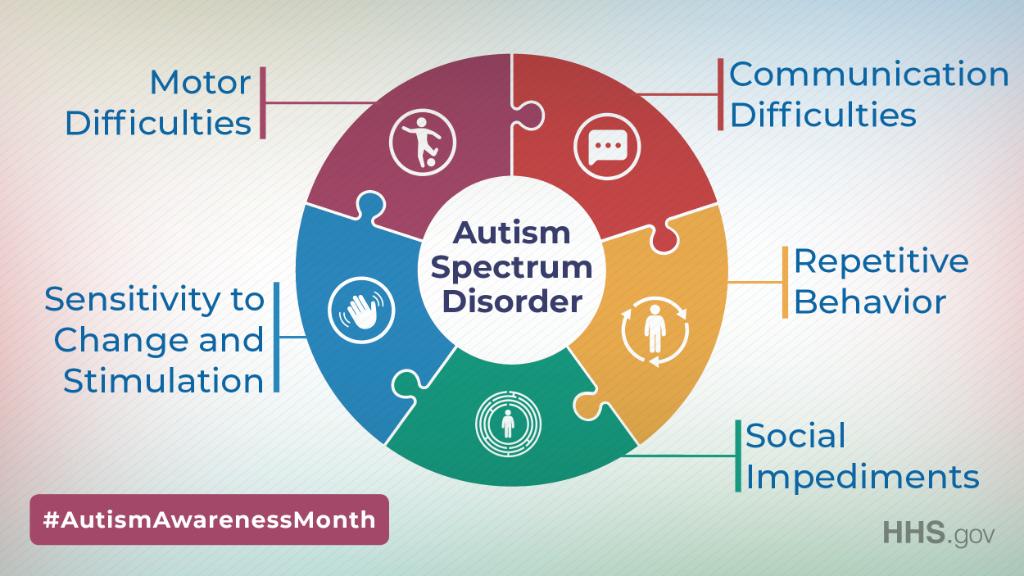

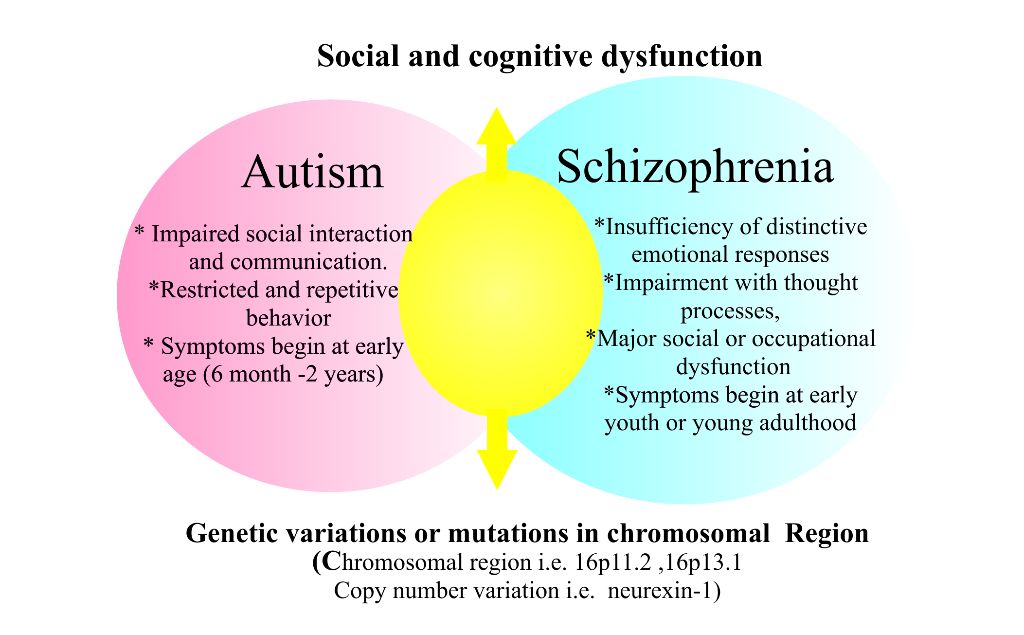

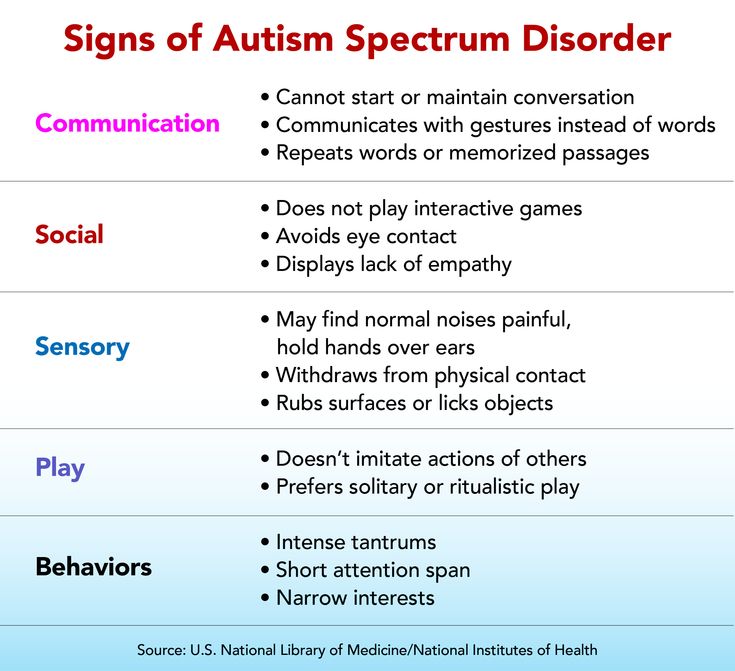

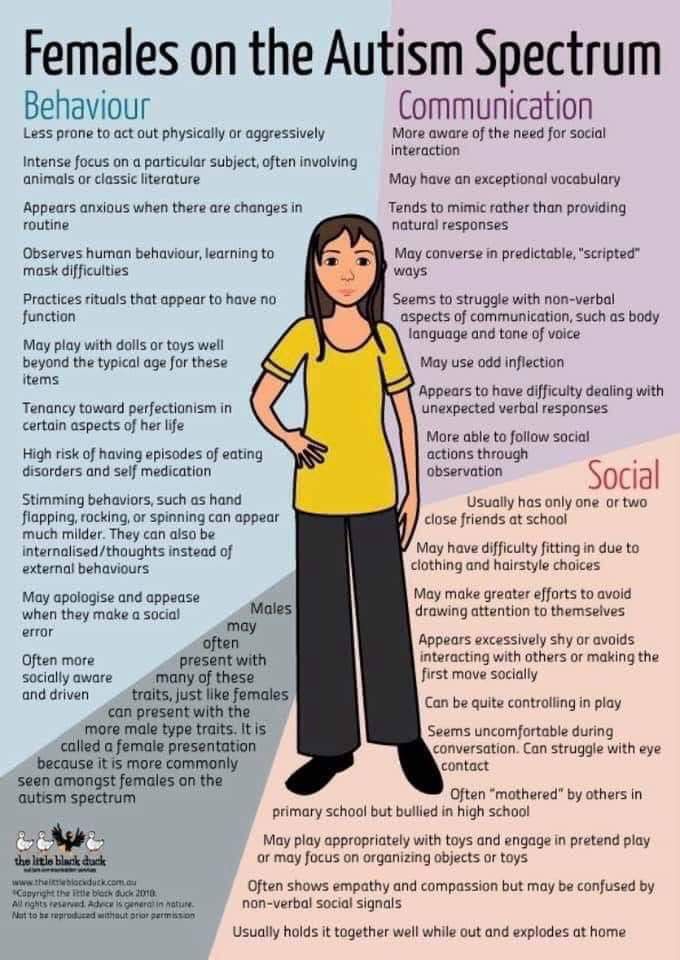

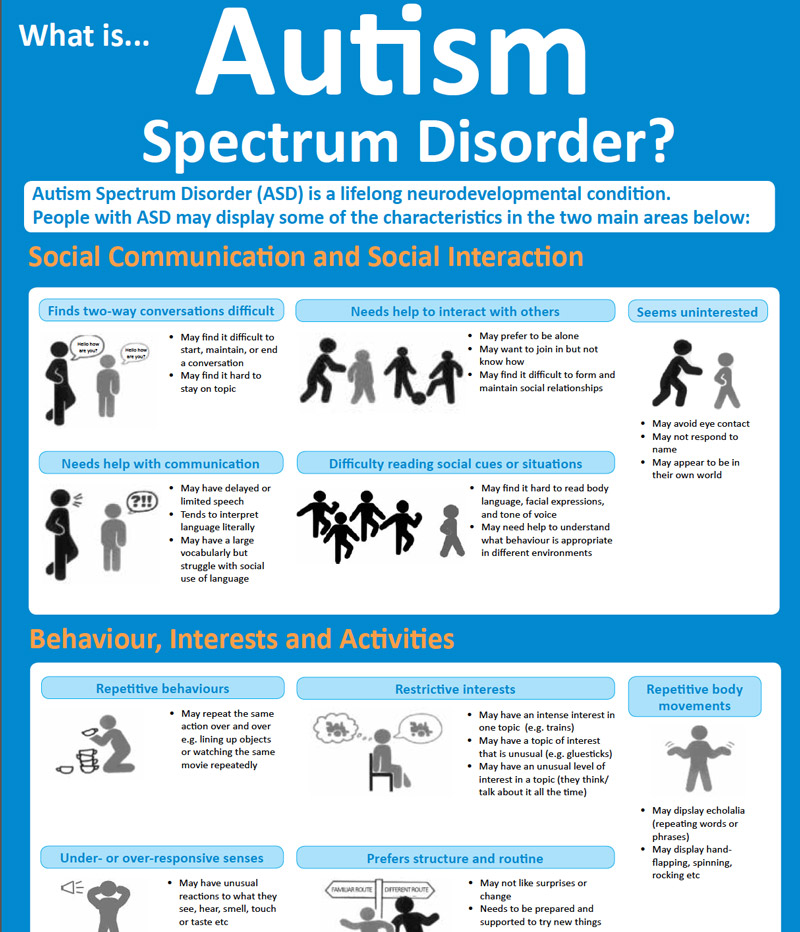

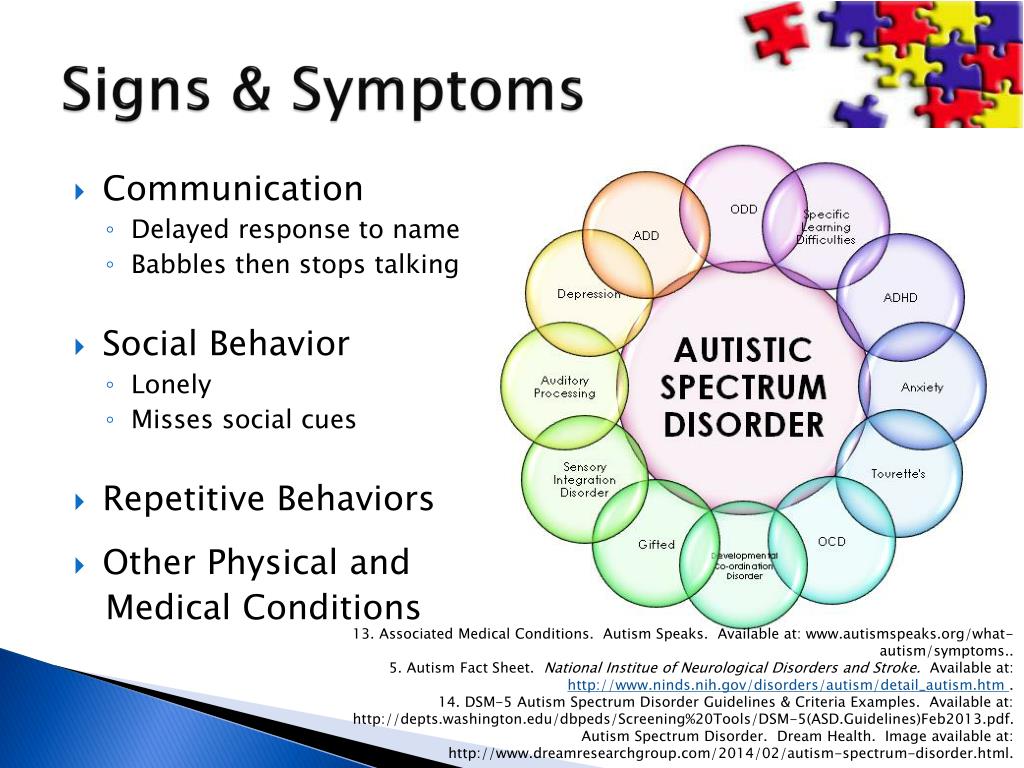

One of the main differences between ASD and SCD – and a red-flag for parents who suspect their child was misdiagnosed with ASD – is that children with autism have difficulties with social communication AND they exhibit repetitive and/or disruptive behaviors.

Repetitive or disruptive behaviors include things like:

- Repeated body movements, such as rocking, flapping, jumping, twirling

- Obsessive fixation on routines and rituals

- Putting things in order and in order again and/or a preoccupation with things being in a very specific order or placement

- Excessive repeating of sounds, syllables, words and/or phrases

- Intense and obsessive preoccupation with specific objects or subjects

- Extreme sensory sensitivity, particularly to sound and/or chaos

Any disruption to routine, order and their schedule or an affront to their sensitivities can result in loud, sometimes violent, outbursts with aggression being self-inflicted or inflicted upon others (or objects) in their immediate environment.

If your child was diagnosed with autism but doesn’t tend to display the restrictive, repetitive or disruptive behaviors associated with autism spectrum disorder, he or she should be reassessed for an accurate diagnosis. You may find out the real issue is social pragmatic communication disorder.

Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder (SCD) encompasses problems related to your child’s communication. She may pronounce words properly and speak in full sentences but struggle to hold a two-way conversation, frequently misunderstand what others are communicating or not recognize pragmatics, the use of language in its proper context.

For a child to receive an SCD diagnosis, the following four key criteria must be present.

1. Persistent difficulties using verbal and nonverbal communication cues across several contexts

- Social purposes, including greeting others and sharing information in a way that’s appropriate for the situation

- Matching the listener’s needs, such as using an indoor versus outdoor voice, implementing every day rather than formal language and talking in different ways and with different language when addressing kids and adults

- Following conversation and storytelling rules, including taking turns during a conversation, rephrasing information when the listener misunderstands him and recognizing and using verbal and nonverbal signals to regulate what’s happening during interactions

- Understanding information that’s not explicitly stated or is nonliteral, ambiguous or open to interpretation, such as making inferences and recognizing idioms, metaphors, humor, and words or phrases with multiple meanings depending on the context

2.

Communication difficulties

Communication difficultiesThe inability to effectively communicate with family, friends and their community in a home, school or other setting.

3. Delayed milestones at an early age

The difficulties emerge in the early years, even if they aren’t diagnosed until later childhood or the teen years. Examples include delays in reaching speech or language milestones and disinterest in talking.

4. Challenges unrelated to other medical or language difficulty

Communication issues are not linked to another general or neurological medical or specific language difficulty, such as intellectual disability, global developmental delay or autism spectrum disorder.

Children who are screened for social pragmatic communication disorder are evaluated on their ability to do the following:

- Respond to others

- Talk about their feelings and emotions

- Take turns speaking and responding to others

- Stay on topic

- Use gestures and hand movements to express themselves (waving hello/goodbye, pointing, expressive gesturing, etc.

)

) - Adjust their speech according to the situation or environment (speaking quietly in a library or learning to speak differently to toddlers as opposed to adults)

- Ask questions or make comments that relate to the conversation topic

- Make and keep friends

- Use words for a variety of purposes, from greetings and requests to conversations and expressing emotions

If you have a young child, under 5-years of age, you may be thinking right now, “My child doesn’t do any of those things. He must have SCD.”

Do not automatically assume anything. Different children develop social communication skills at various stages, and your child may simply be less communicative right now.

Alternatively, you may feel that your teen could not have SCD. Maybe you think, “Sure, sometimes he can’t hold a conversation, but that’s because of normal teenage moodiness.”

Actually, your child could have SCD. Sometimes, it’s not diagnosed until adolescence when social interactions become more complicated, uncertain and challenging.

Due to the differences in ASD and SCD, professional assessment is critical.

You certainly don’t want to project anything onto your child that isn’t there or spend precious time and resources treating something that doesn’t exist.

However, if your child has a need, a diagnosis allows you to get her the help to learn important communication skills to succeed in school, at home, and in life.

To obtain an accurate diagnosis so you can get the proper treatment, therapy and help for your child, here are a few tips.

- Rule out ASD with an assessment performed by your child’s doctor and other professionals.

- Gain a referral to a speech pathologist who understands how to diagnose and treat social pragmatic communication disorder.

- Ensure the speech therapist observes and evaluates your child in numerous settings, including home, the classroom and community interactions.

- Remind your child’s teacher and caregivers to complete any questionnaires the therapist provides.

- Schedule formal one-on-one testing when the therapist assesses your child’s specific communication and language capabilities, skills, and challenges.

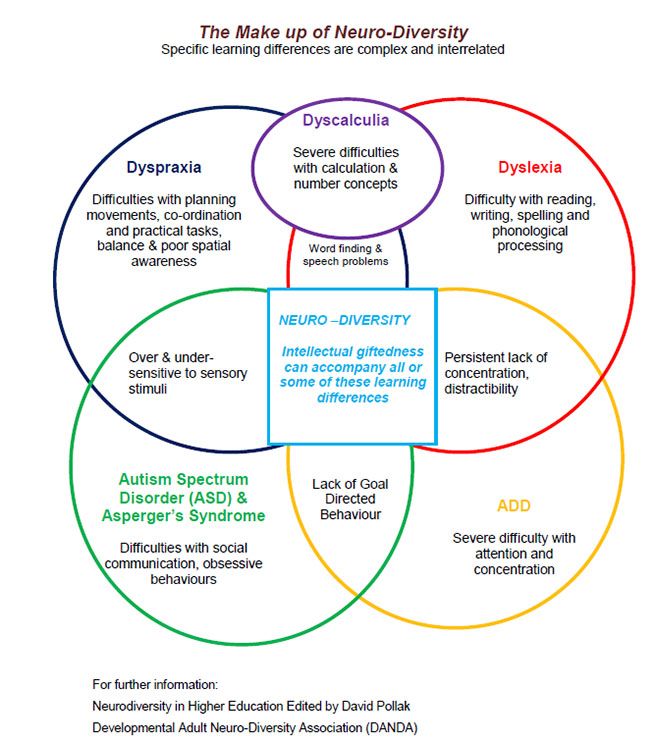

- Remember that an accurate diagnosis is complicated further if a child also has a speech disorder, ADD/ADHD, other behavioral disorders or a learning disability, so ensure the therapist addresses these concerns, too.

After you receive a formal diagnosis, you can begin beneficial therapy. It could change your child’s life.

Regardless of whether or not your child has ASD or SCD, it’s important that he or she works with professionals who specialize in the specific condition.

For example, if your child has SCD, a speech-language pathologist who specializes in SCD may be available via your child’s school. If not, speak with your healthcare provider or reach out to ASD resources who may be able to offer referrals.

Speech-language pathologists are trained to work with individuals who have non-verbal communications as well as social interactions.

In addition to providing individuals and their families with practice and training, they also offer interactive visual tools – such as picture boards or tablets – which can help to bridge the gap as the individual makes progress through therapy.

How to Treat Social Pragmatic Communication Disorder

Treatment for social pragmatic communication disorder typically includes several stages which can be guided by a professional. These stages require the involvement of your entire family along with other adults in your child’s life. They most importantly necessitate the need for practice and patience.

Professional therapy

Professional, one-on-one or small-group therapy with a licensed speech-language pathologist specializing in SCD works wonders for your child. This therapy can occur in a center, in your home or at your child’s school.

Family support & involvement

Your family is your child’s microcosm of society. Since communication doesn’t happen in a vacuum, the therapist will train the whole family in techniques, strategies, games, tools, etc. , to help you communicate with your child. This practice will pay off in your child’s interactions with other social groups and communities, too.

, to help you communicate with your child. This practice will pay off in your child’s interactions with other social groups and communities, too.

Education & tools for teachers, coaches, and other elders

Just as your family will need to practice, the child will gain more support if teachers, coaches, and other close friends and family members possess the information and tools with which to engage your child more fully.

Practice, practice, practice

Your child needs practice in real-life scenarios. You can make this easy by providing communication partners for your child, including family members, other therapists, teachers, and peers.

Practice can occur naturally in a number of ways, including:

- conversations and gentle reminders

- using stories as a chance to discuss facial expression and ask/answer questions about characters’ interactions

- talking and asking about feelings and body language in particular situations

After you have a diagnosis and treatment plan, help your child succeed by remaining an active participant in his therapy.

In addition to providing transportation to therapy appointments, work closely with the therapist. You can reinforce skills learned during sessions when you’re at home or in the community, and you can learn beneficial skills that help you support your child at home.

You can also practice several therapeutic activities with your child, including:

- Use visual supports for your child’s daily schedule, expectations, chore chart, etc., which is a benefit for kids with SCD who process information visually.

- Take turns and imitate the flow that’s typical of social interactions. Together, you can roll a ball back and forth, repeat words your child says or mimic a pet.

- Talk about the feelings. Use stories, books, and puppets to explore a character’s feelings and emotions. You can also review real-life scenarios that may occur with family members or peers.

- Read and discuss a book, and ask open-ended questions like, “What was your favorite part of the story?” Or “What did you think about what the boy did in chapter two?”

- Predict the next action in a story.

Explore clues that lead you to the conclusion or work backward to discover clues.

Explore clues that lead you to the conclusion or work backward to discover clues. - Introduce your child to developmentally appropriate pop culture so that she can relate to peers and have something to discuss.

- Plan structured play dates. Begin with one friend, and limit the time until your child’s skills develop enough to support more friends or a longer play time.

Finally, bridge the gap between home and school. Contact the special education department and ask for an Individualized Education Program (IEP) that includes speech therapy, social skills training, and other supports, including possibly a teacher’s aide.

An alternative to the IEP is a 504 plan. It also provides accommodations that help your child, including extra time to process information or reading support.

Parenting a child with SCD or ASD can be a challenge, and unanswered questions and concerns simply breed more unnecessary worry. Trust your instincts and seek the professional, qualified assistance needed to screen your child and obtain an accurate diagnosis.

The sooner you have a concrete diagnosis, the better able you and the experts will be at providing the essential tools and support your child needs to be successful.

To learn more about social pragmatic communication disorder and autism, contact Sarah Dooley Center online or at 804-521-5571.

« Oldest

Newest »

Social Communication Disorder: Symptoms Similar to Autism

What is Social Communication Disorder?

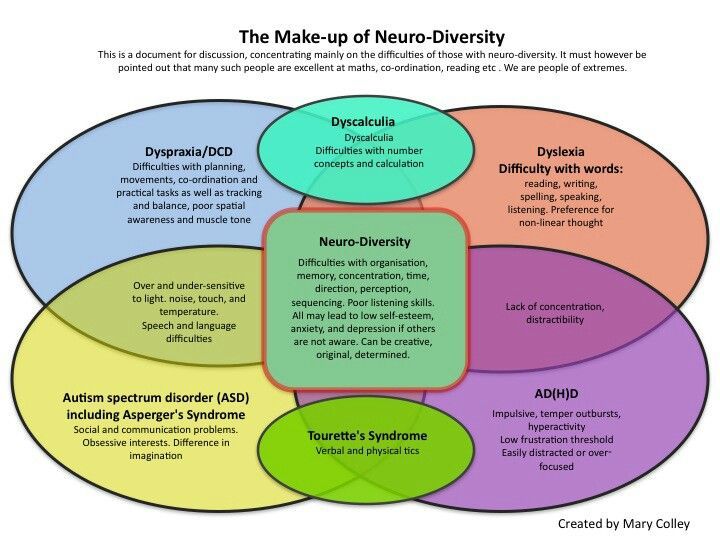

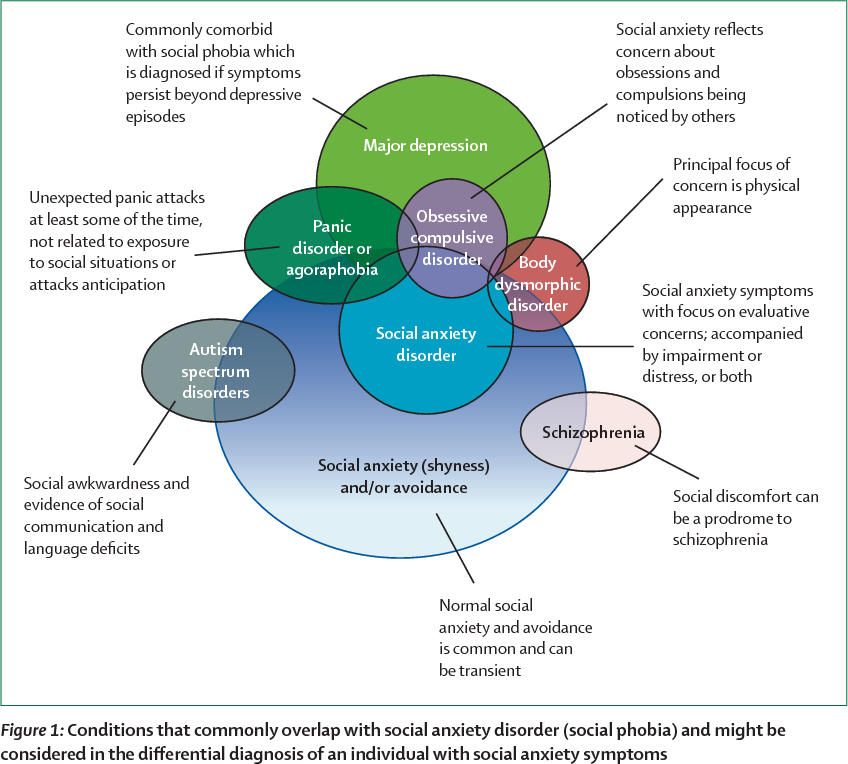

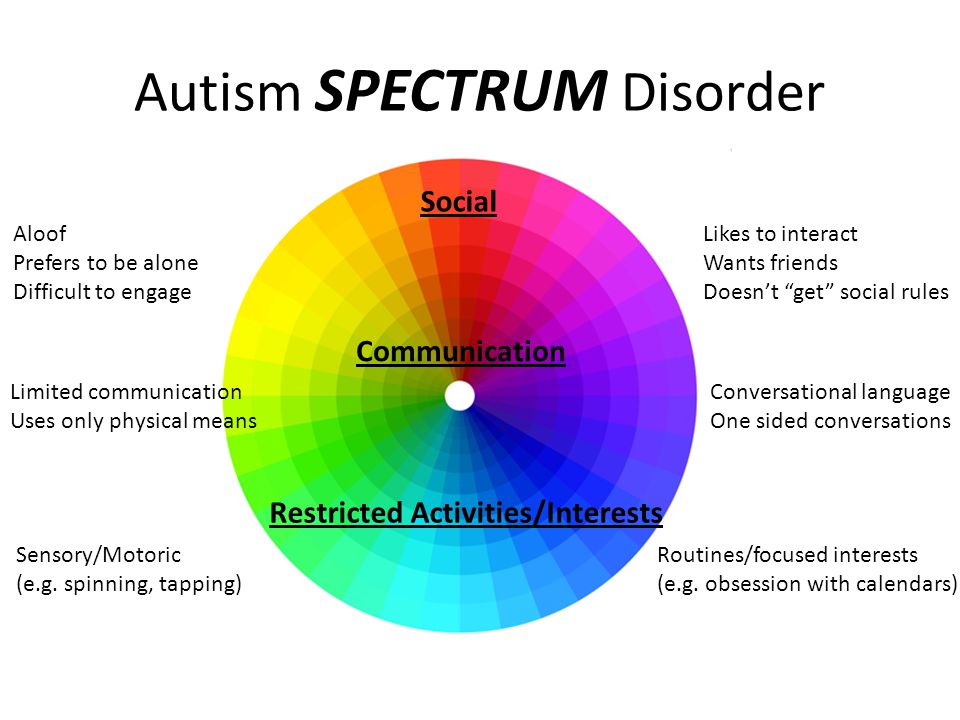

Social communication disorder (SCD) makes it difficult to communicate with other people in social situations. The condition first appeared in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-V) in 2013; prior to that, people exhibiting its symptoms were commonly diagnosed on the autism spectrum, according to Autism Speaks.

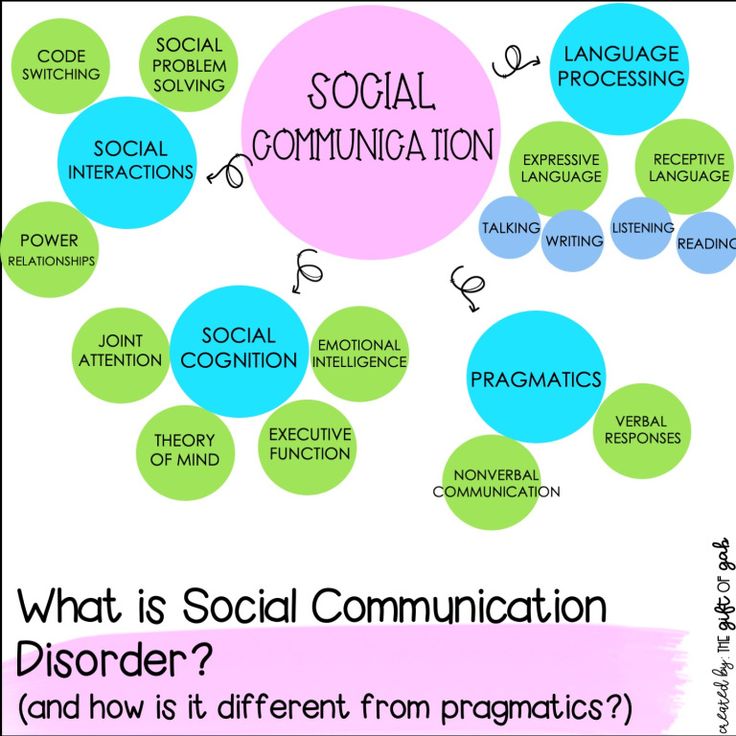

“Social communication” encompasses more than the spoken word. It also includes social cognition, pragmatics, non-verbal communication, and language processing. Individuals with SCD may struggle to vary speech style; use different components of language like vocabulary, syntax and phonology; understand the rules of communication; and share perspectives, according to the American Speech-Language-hearing Association (ASHA. )

)

What Are the Symptoms of Social Communication Disorder?

Poor pragmatics — or changing speech and communication to fit the circumstances — is one of the hallmark characteristics of SCD. People with SCD have trouble modifying their communication — including tone of voice, pitch, and volume — based on the specific situation.

According to Autism Speaks, people with SCD may also struggle with:

- Responding to others

- Using gestures such as waving and pointing

- Taking turns when talking

- Talking about emotions and feelings

- Staying on topic

- Adjusting speech to fit different people and different circumstances

- Asking relevant questions

- Responding with related ideas

- Using words for different purposes, such as greeting people, asking questions, responding to questions, making comments

- Making and keeping friends

[Self-Test: Could You Have Autism Spectrum Disorder?]

Early signs in young children, according to the Child Mind Institute, might include:

- A delay in reaching language milestones

- A low interest in social interactions

Young children with SCD may rarely initiate social interactions or respond minimally when social overtures are made, according to the Child Mind Institute.

How Is Social Communication Disorder Diagnosed?

Many symptoms of SCD overlap with those of other conditions and learning disabilities, which often complicates diagnosis, according to a study completed in 2013. Sometimes it is necessary to rule out other potential problems first. For example, a doctor might recommend a comprehensive hearing assessment to rule out hearing loss first. A speech and language pathologist with a thorough understanding of comorbid conditions and learning disabilities should complete the hearing and other assessments, taking into consideration age, cultural norms, and expected stage of development.

Screening for SCD often includes interviews, observations, self-reported questionnaires, and information completed by parents, teachers or significant others, according to ASHA. It should also take into consideration your family medical and educational history. ASD symptoms are more likely if a family member has been diagnosed with ASD, communication disorders, or specific learning disorders, according to Child Mind Institute.

Following the assessment, the speech and language pathologist may provide a diagnosis, a description of the characteristics and severity of the condition, recommendations for interventions, and referrals to other specialists, as needed.

[Self-Test: Is My Child On the Autism Spectrum?]

How Is Social Communication Disorder Treated?

SCD is a relatively new condition. There is no specific treatment for SCD, according to the Child Mind Institute, but it is thought that speech and language therapy with emphasis on pragmatics, along with social skills training, will help.

Treatment should be specific to the individual with a focus on functional improvements in communication skills, especially within social situations. Other goals of treatment may include:

- Address weaknesses related to social communication

- Work to build strengths

- Facilitate activities involving social interactions to build new skills and strategies

- Look for and address barriers that may be making social communication more difficult

- Build independence in natural communication environments

Treatment for SCD often includes parents and other family members. The therapist working with your child may also reach out school personnel, including teachers, special educators, psychologists, and vocational counselors to ensure that your child receives consistent practice and feedback in a variety of social situations, according to ASHA.

The therapist working with your child may also reach out school personnel, including teachers, special educators, psychologists, and vocational counselors to ensure that your child receives consistent practice and feedback in a variety of social situations, according to ASHA.

Tools used during treatment might include:

- Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC), which includes supplementing speech with pictures, line drawings or objects, gestures, and finger spelling.

- Computer-based instruction for teaching language skills including vocabulary, social skills, social understanding, and social problem solving.

- Video-based instruction that uses video recording to provide a model of target behavior.

- Comic book conversations, which depict conversations between two or more people illustrated in comic-book style.

- Social skills groups that incorporate instruction, role playing, and feedback with two to eight peers and a facilitator, who may be a teacher or counselor.

In addition, the therapist might help your child develop scripted responses to help him or her get past the initial moments of a conversation.

How Is Social Communication Disorder Different Than Autism?

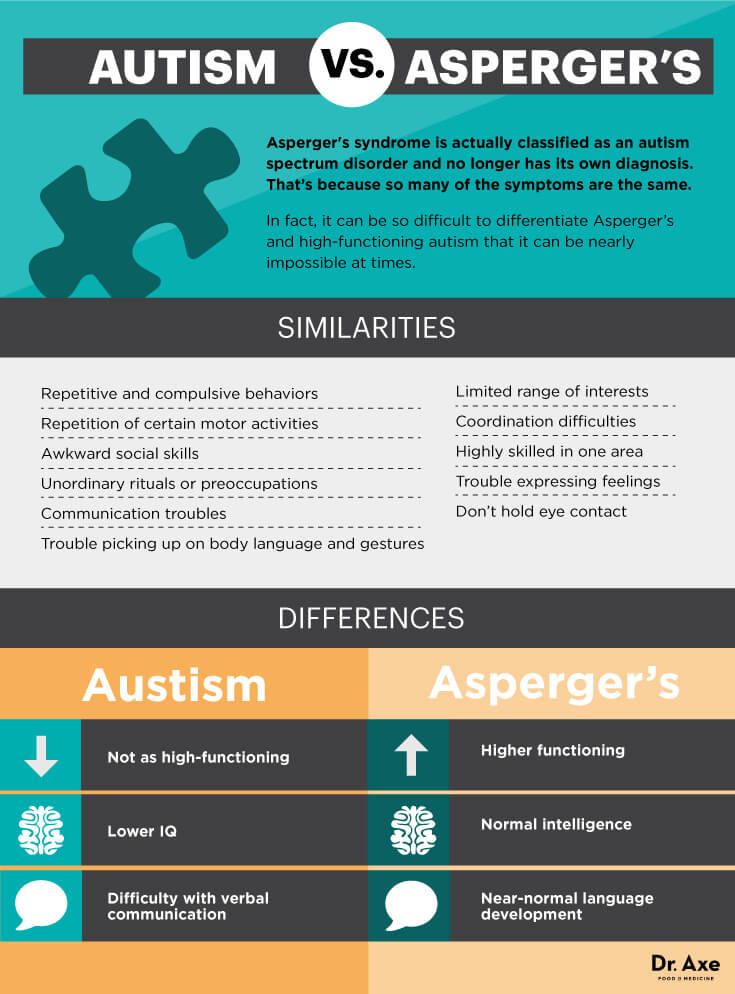

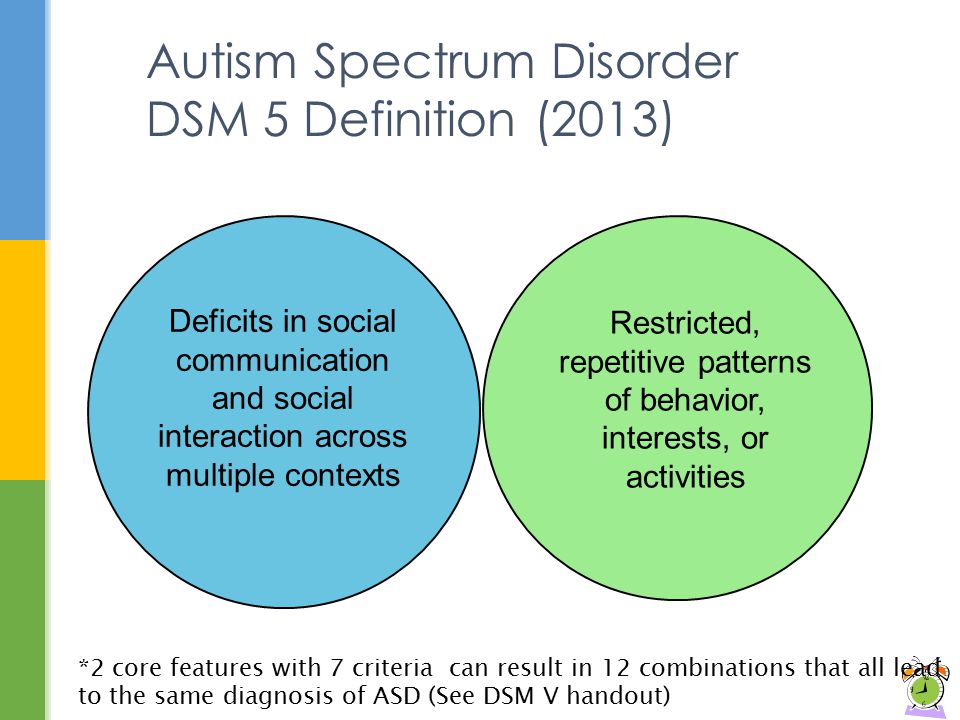

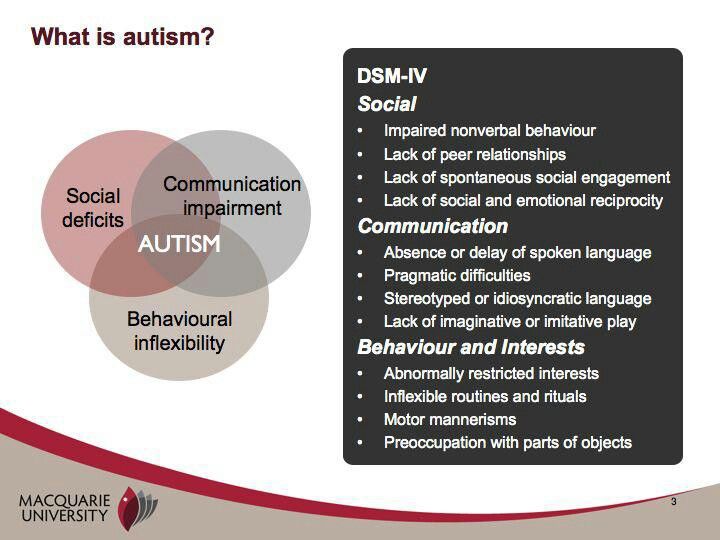

Social communication problems are a hallmark symptom of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), however SCD can occur in individuals who do not meet the diagnostic criteria for ASD. People with both SCD and ASD have more than social communication difficulties; ASD also includes restricted or repetitive behaviors. Because it is considered part of an autism diagnosis, SCD cannot be diagnosed alongside ASD. However, it is important to rule out ASD before diagnosing SCD.

Prior to 2013, when SCD was added to the DSM-V as a stand-alone diagnosis, individuals with the symptoms above may have been diagnosed with ASD, most often pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) or Asperger’s syndrome, both subtypes of ASD. After the introduction of SCD, one study found that 22 percent of those with SCD would previously have met the criteria for PDD-NOS and six percent would have met the criteria for Asperger’s syndrome.

How Can I Help My Child with SCD?

If your child has a diagnosis of SCD, Autism Speaks recommends taking this steps at home:

- Practice taking turns by rolling or throwing a ball back and forth. Take turns repeating words.

- Read a book with your child and ask open-ended questions to encourage discussion.

- Talk about what characters in books might be thinking and why. Take turns offering your ideas. Talk about how other people – siblings, friends, classmates – might feel during certain situations.

- Play “What’s next” when reading. Stop at a point and have your child predict what is going to happen next. Look for clues in the story that can help you guess.

- Plan structured play dates. Start small, with one friend. Have a planned, structured activity and a start and stop time.

- Use visual supports to aid in conversations.

[Free Download: 14 Ways to Help Your Child Make Friends]

Previous Article Next Article

Autism New Jersey - About Autism

What is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

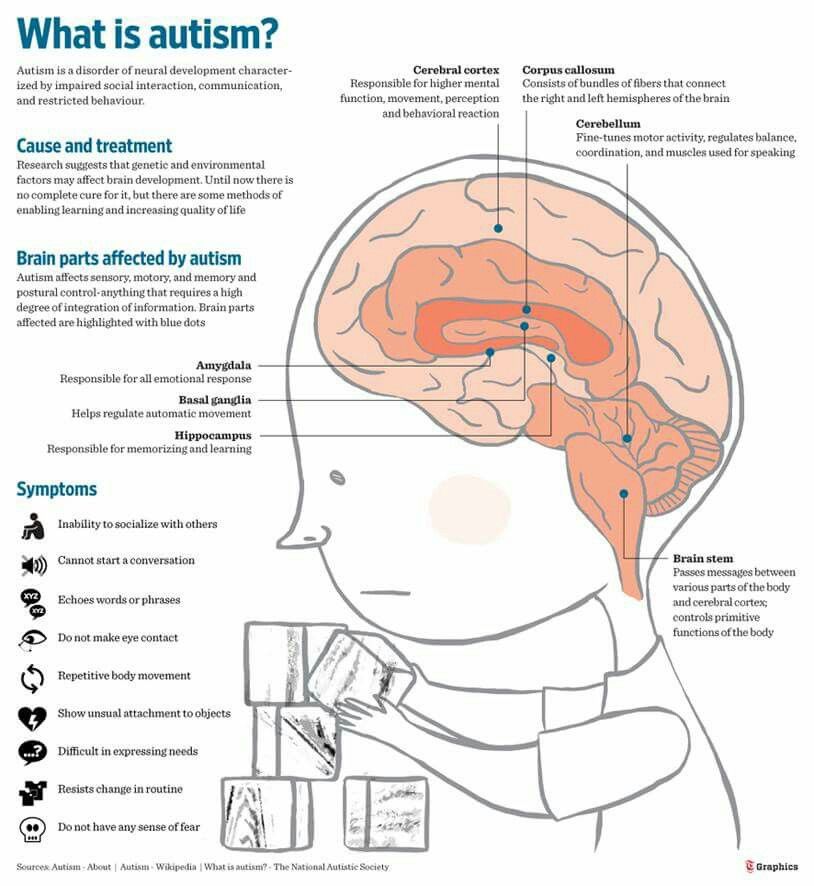

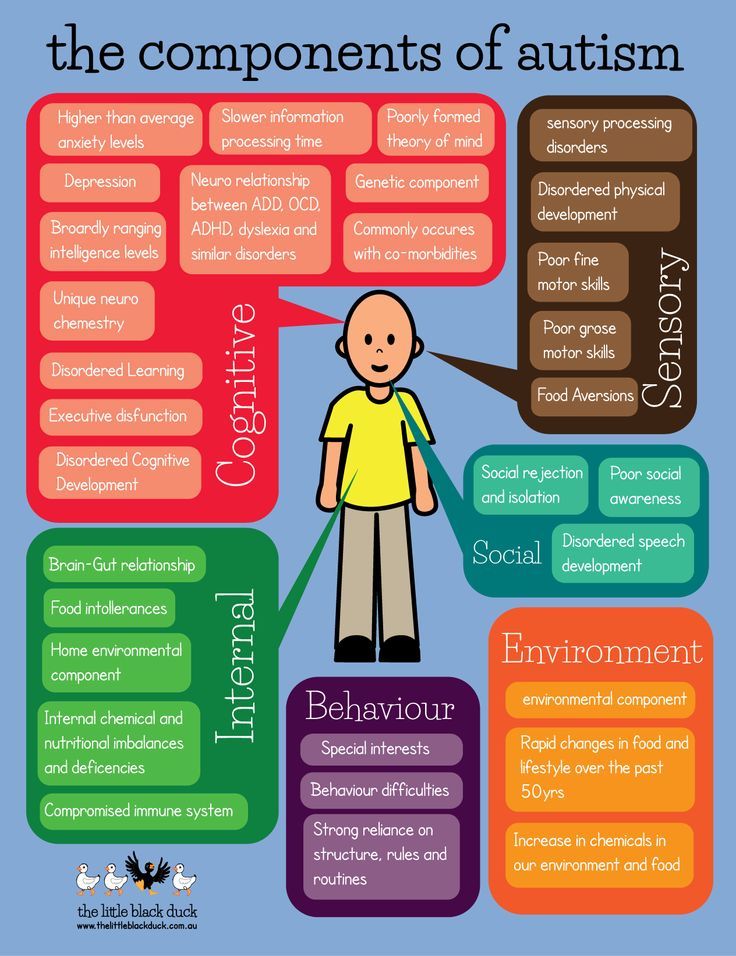

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), or autism, is a neurobiological disorder characterized by impaired social communication and interaction, and restricted and repetitive behaviors. People with autism find it difficult to interact with others: build relationships, use language, regulate their emotions, and understand the points of view of others.

People with autism find it difficult to interact with others: build relationships, use language, regulate their emotions, and understand the points of view of others.

Social communication/interaction deficits may include:

-

Comprehension of spoken language

-

Call for interaction or exchange of information

-

Echolalia (repetition of words or phrases)

-

Conversation

-

Understanding non-verbal cues (body language, facial expressions, etc.

-

Unusual tone, pitch and intonation

-

Pretend play

Restricted/repetitive behaviors may include:

-

Intense attention to a particular item, action or topic

-

Unusual play activities (repeatedly spinning the wheels of the toy instead of driving it)

-

Perseverance in following certain procedures

-

Difficult to adapt to change

-

Rocking, stepping, snapping fingers, waving arms or other repetitive movements

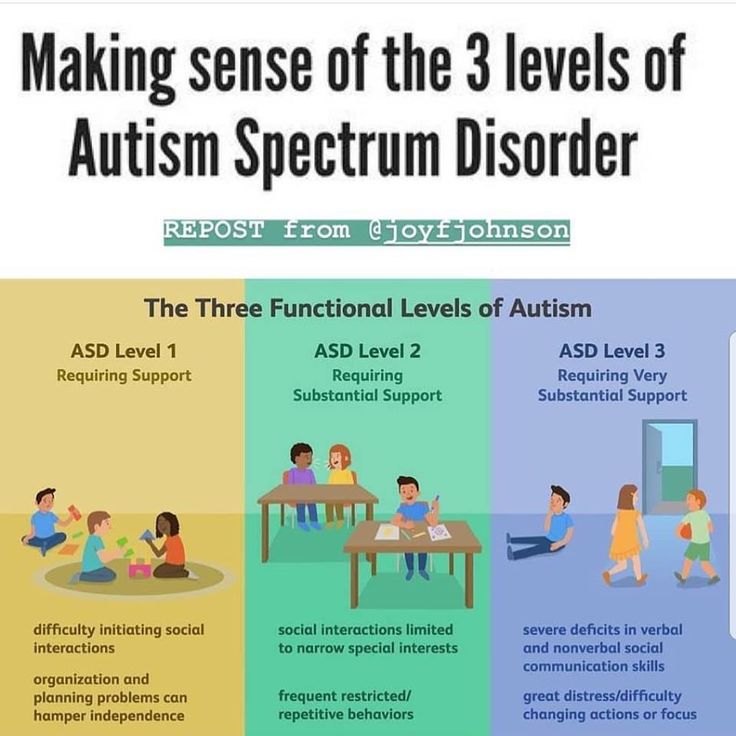

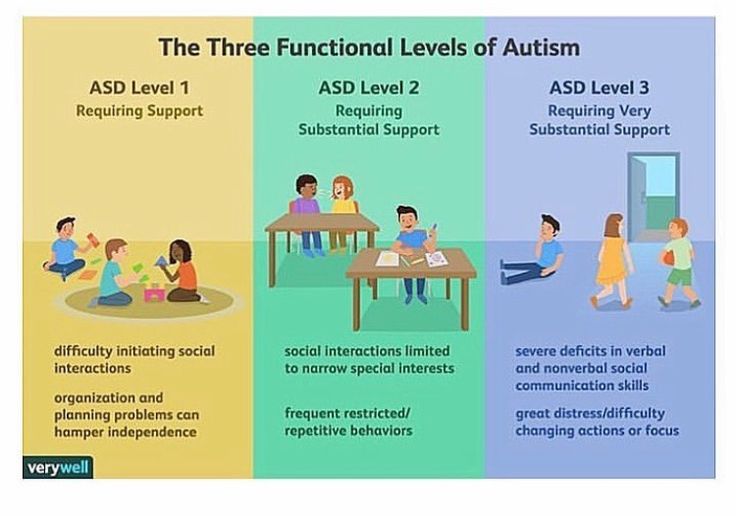

What does "in the spectrum" mean?

The term spectrum highlights how specific social and behavioral problems differ for each individual, and sometimes throughout each individual's life.

Some have problems that significantly interfere with their daily activities and require constant monitoring to stay safe; others have little noticeable impairment.

While people with other special needs often learn and behave at a level consistent with their IQ, people with autism can show many ups and downs in their abilities. For example, they may have a wonderful memory, but they cannot ask for help. A thorough assessment is essential to identify each person's strengths and support needs.

What are some of the associated features of autism?

-

Mental retardation (30%)

-

Epilepsy

-

Gastrointestinal problems

-

Unusual reactions to touch input

-

Poor awareness of major hazards (including wandering and self-harm)

-

Problems with eating, sleeping and toileting

What are the causes and risk factors for autism?

The causes of autism are currently unknown. Most researchers believe that there is no single reason. Current research strongly suggests: Autism is a genetic disorder that may be caused by environmental (non-genetic) factors that have yet to be determined.

Most researchers believe that there is no single reason. Current research strongly suggests: Autism is a genetic disorder that may be caused by environmental (non-genetic) factors that have yet to be determined.

Increased risk for:

-

Children with a sibling or parent with ASD

-

Children born prematurely, with low birth weight, with multiple pregnancies or elderly parents

Related links

Stay in touch!

Get news and announcements from Autism New Jersey straight to your inbox.

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) • Autism. Encyclopedia

Terms

diagnostics

Autism spectrum disorder, ASD

also, a group of neurological disorders characterized by impaired ability to establish social interaction and support social interaction interests and repetitive activities. ASD can be diagnosed at any age, but symptoms should appear in the first years of life.

ASD can be diagnosed at any age, but symptoms should appear in the first years of life.

Historical note

For the first time, Leo Kanner described autism as a separate disease using the example of 11 children in his famous work “Autistic disorders of affective contact”, published in 1943. In this work, the author proposed to call “early childhood autism” special conditions in children starting from the first years of life and determined by extreme self-isolation. Early infantile autism Kanner considered a special disorder of the schizophrenia spectrum, emphasizing its difference from schizophrenia. In the clinical description of early childhood autism, Kanner introduced not only self-isolation, but also disorders of speech, motor skills, behavior, stereotyping of activities, interests, which made it possible to single it out as a separate disorder.

Around the same time, the Austrian psychotherapist Hans Asperger, in his dissertation on autistic psychopathy, described 4 children with similar symptoms. Like Kanner, Asperger believed that the primary in autism should be considered a violation of social interaction that persists throughout life. However, differences can be seen in the two authors' descriptions of language abilities and motor coordination in autism. If Kanner attributed the absence of the communicative function of speech in children to the key symptoms of autism, then Asperger, on the contrary, wrote about the “free and original” use of language by his patients. Kanner also noted the motor dexterity of children, especially in terms of fine motor skills, while Asperger, in turn, characterized his wards as clumsy, noting their difficulties in both fine and general motor skills. However, long before the publication of Asperger's work, in 1925 in Russian and in 1926 in German, the work of Grunya Efimovna Sukhareva was published, in which she described a behavioral syndrome characterized by high intellectual development and an inability to establish and maintain social contacts.

Like Kanner, Asperger believed that the primary in autism should be considered a violation of social interaction that persists throughout life. However, differences can be seen in the two authors' descriptions of language abilities and motor coordination in autism. If Kanner attributed the absence of the communicative function of speech in children to the key symptoms of autism, then Asperger, on the contrary, wrote about the “free and original” use of language by his patients. Kanner also noted the motor dexterity of children, especially in terms of fine motor skills, while Asperger, in turn, characterized his wards as clumsy, noting their difficulties in both fine and general motor skills. However, long before the publication of Asperger's work, in 1925 in Russian and in 1926 in German, the work of Grunya Efimovna Sukhareva was published, in which she described a behavioral syndrome characterized by high intellectual development and an inability to establish and maintain social contacts. Subsequently, the description given by G. E. Sukhareva almost completely coincided with the description of autistic psychopathy given by G. Asperger.

Subsequently, the description given by G. E. Sukhareva almost completely coincided with the description of autistic psychopathy given by G. Asperger.

Kanner and Asperger's description was further expanded to include other diagnoses that later became part of the autism spectrum disorders: childhood autism, atypical autism, Rett's syndrome, another disintegrative disorder of childhood, hyperactive disorder associated with mental retardation and stereotyped movements, syndrome Asperger's, other general developmental disorders, pervasive developmental disorder, unspecified [3].

General characteristics of symptoms that are found to varying degrees in autism spectrum disorders [1; 2]: manifestations of detachment, insufficient need for communication, striving for the immutability of the environment (“the phenomenon of identity”), peculiar fears, originality of motor skills (motor stereotypes; motor disinhibition or, conversely, lethargy), originality of speech and the process of its formation (frequent absence of babbling, cooing, difficulties in isolating the semantic structure of speech, difficulties in expressive speech, gestural speech, facial expressions and pantomime, echolalia), intellectual unevenness, stereotypes in behavior, play, speech, as well as the ability to relative compensation with early intervention.

Prevalence

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in 54 children is diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (according to the World Health Organization, 1 in 160 children). ASD is 4.5 times more common in boys (1 in 42 boys) than in girls (1 in 189 girls). Studies conducted in Asia, Europe and North America have shown that the prevalence of ASD in the population varies from 1 to 2%.

Etiology

Based on available scientific evidence, there are many factors that increase the likelihood of a child developing ASD, including genetic and environmental factors. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a child is more likely to be diagnosed with ASD if:

1) there are already children with ASD in the family (2-18%). In the case of a diagnosis of one of the monozygotic twins, the risk for the second, according to various studies, varies from 35 to 95% (in dizygotic - from 0 to 31%).

2) mother's age over 35 and/or father's age over 40 [7; 8].

3) the presence of certain genetic or chromosomal diseases: Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome (Martin-Bell syndrome), tuberous sclerosis, and others.

Some studies have demonstrated links between the development of ASD in a child and various factors in the course of pregnancy and childbirth: premature birth, low birth weight, infections in the mother, taking certain medications during pregnancy, diabetes or obesity in the mother, etc. [4; 5; 6]

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Revision 5, was developed and published in 2013. Several DSM-IV disorders were grouped into spectrums in the DSM-V, including autism spectrum disorders, which were treated in the DSM-IV under the headings autism, Asperger's syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder. Although the DSM-V classifies all manifestations of these conditions under one rubric, the specifiers define ASD variants according to severity, including the presence or absence of intellectual decline, speech impairment, comorbid medical conditions, or loss of acquired skills.

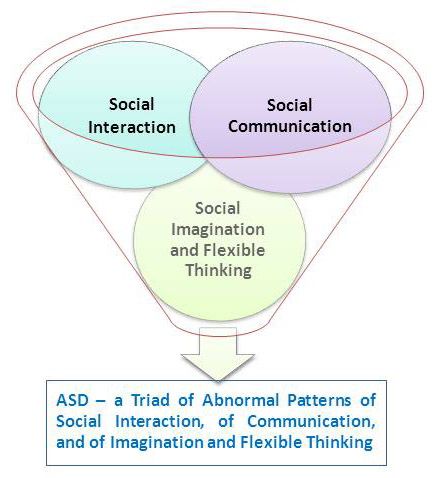

In 1979, Lorna Wing and her colleague Judith Gould published the results of a study of 173 Camberwell children with autism (often referred to as the "Camberwell Study") in which for the first time attempts were made to systematize the main symptoms of autism. The authors identified a triad of disorders in autism, which they later called the "Wing-Gould triad": disorders of social interaction, communication, and imagination. And although there is no official evidence that the compilers of the DSM focused on this triad, describing the signs of autism, nevertheless, a connection can be traced.

See also: Childhood Autism, Atypical Autism, Childhood Disintegrative Disorder, Asperger's Syndrome, Rett's Syndrome

Text: Evgenia Lebedeva , Candidate of Psychological Sciences, Senior Researcher, Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences

(1) Bashina V. M., Simashkova N. V. Autism in childhood //M. : Medicine. - 1999. - T. 1. (2) Oudshoorn D. N. Child and adolescent psychiatry / Ed. prof //Ya Gurovich. – 1993. (3) Churkin AA, Martyushov AN Brief guide to the use of ICD_10 in psychiatry and narcology. Moscow: Triada-X Publishing House, 2000. (4) Christensen J. et al. Prenatal valproate exposure and risk of autism spectrum disorders and childhood autism //Jama. - 2013. - T. 309. - No. 16. - S. 1696-1703. (5) Darcy-Mahoney A. et al. Probability of an autism diagnosis by gestational age // Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews. - 2016. - T. 16. - No. 4. - S. 322-326. (6) Fezer G. F. et al. Perinatal features of children with autism sPectrum disorder // Revista Paulista de Pediatria. - 2017. - T. 35. - No. 2. - S. 130-135. (7) Idring S. et al. Parental age and the risk of autism spectrum disorders: findings from a Swedish population-based cohort //International journal of epidemiology.

: Medicine. - 1999. - T. 1. (2) Oudshoorn D. N. Child and adolescent psychiatry / Ed. prof //Ya Gurovich. – 1993. (3) Churkin AA, Martyushov AN Brief guide to the use of ICD_10 in psychiatry and narcology. Moscow: Triada-X Publishing House, 2000. (4) Christensen J. et al. Prenatal valproate exposure and risk of autism spectrum disorders and childhood autism //Jama. - 2013. - T. 309. - No. 16. - S. 1696-1703. (5) Darcy-Mahoney A. et al. Probability of an autism diagnosis by gestational age // Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews. - 2016. - T. 16. - No. 4. - S. 322-326. (6) Fezer G. F. et al. Perinatal features of children with autism sPectrum disorder // Revista Paulista de Pediatria. - 2017. - T. 35. - No. 2. - S. 130-135. (7) Idring S. et al. Parental age and the risk of autism spectrum disorders: findings from a Swedish population-based cohort //International journal of epidemiology.