Is autism the same as aspergers

Asperger’s Syndrome - Autism Society.

History

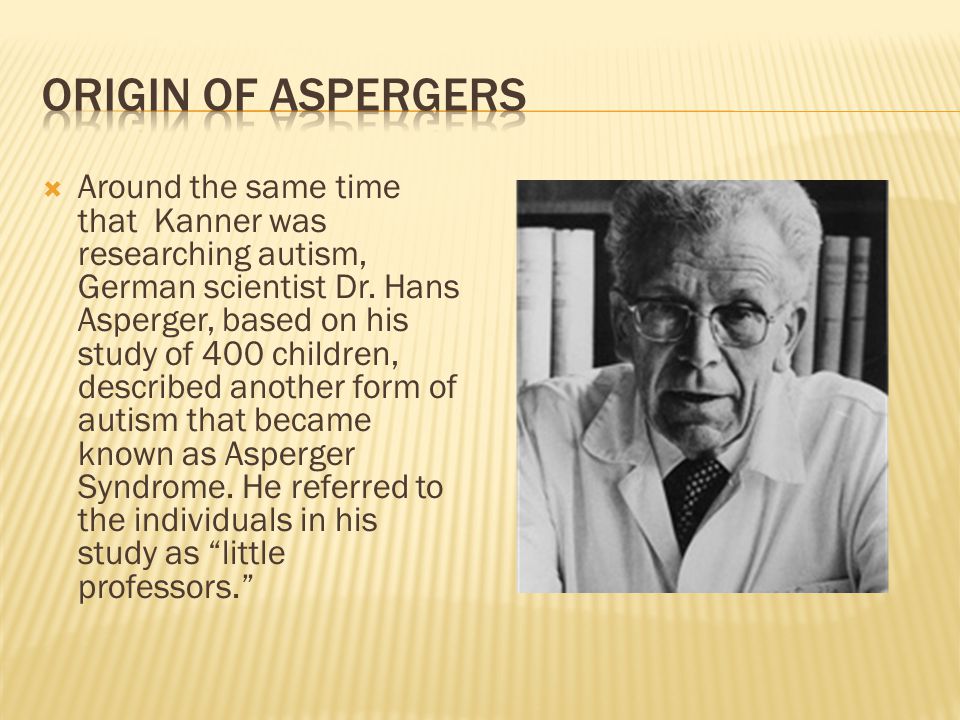

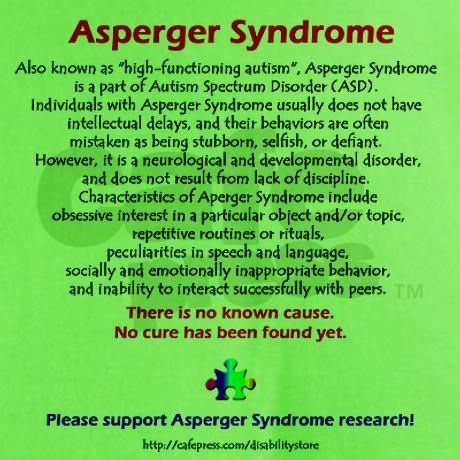

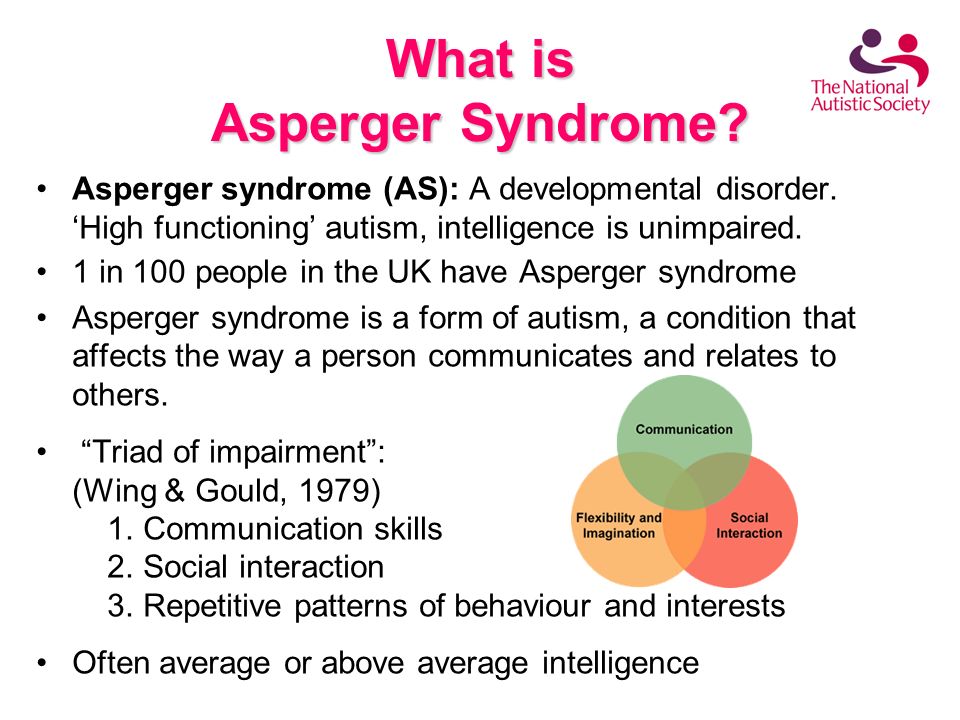

Asperger’s syndrome (also known as Asperger’s Disorder) was first described in the 1940s by Viennese pediatrician Hans Asperger, who observed autism-like behaviors and difficulties with social and communication skills in boys who had normal intelligence and language development. Many professionals felt Asperger’s syndrome was simply a milder form of autism and used the term “high-functioning autism” to describe these individuals. Uta Frith, a professor at the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience of University College London and editor of Autism and Asperger Syndrome, describes individuals with Asperger’s as “having a dash of autism.”

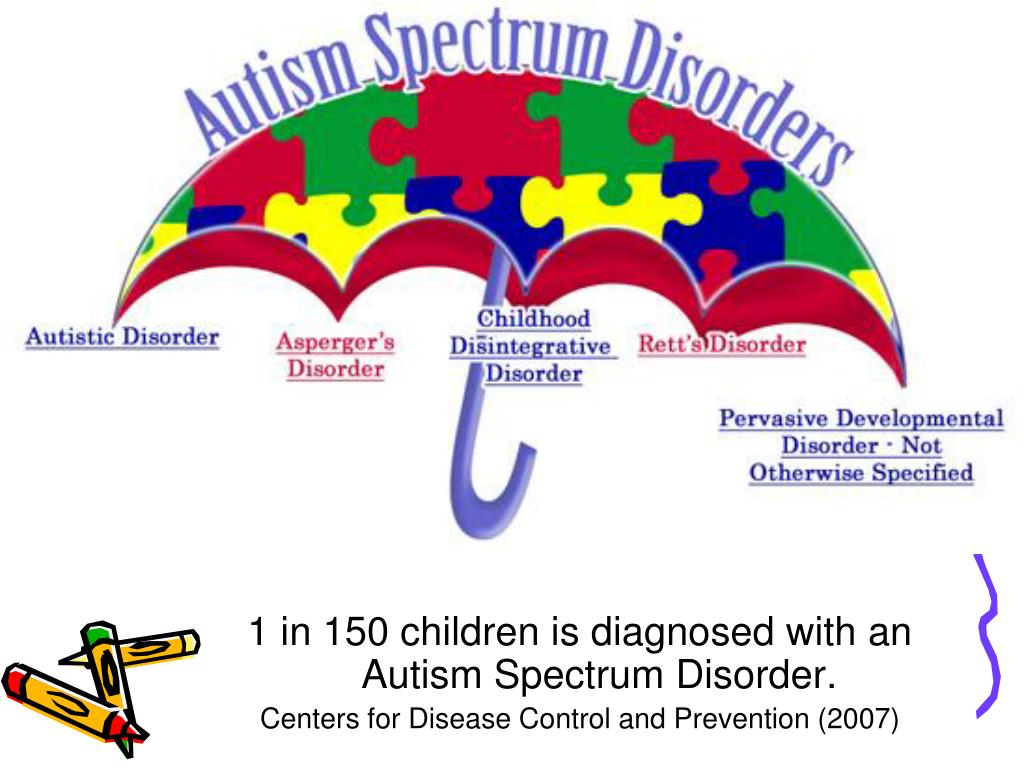

Asperger’s Disorder was added to the American Psychiatric Association’s

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) in 1994 as a separate disorder from autism. However, there are still many professionals who consider Asperger’s Disorder a less severe form of autism. In 2013, the DSM-5 replaced Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders with the umbrella diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.

Characteristics

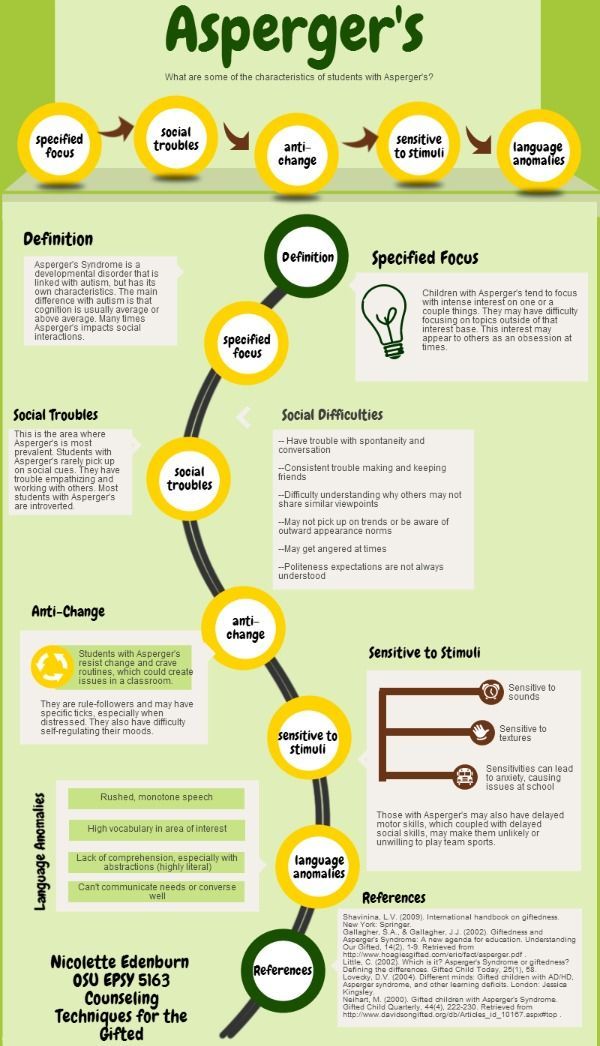

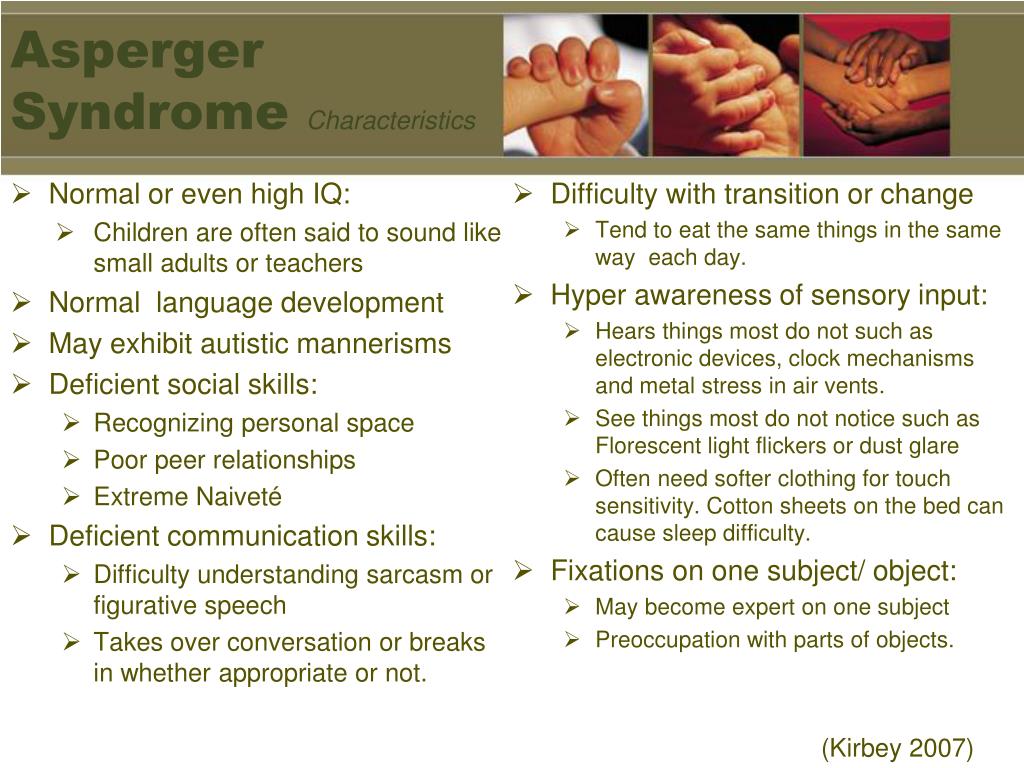

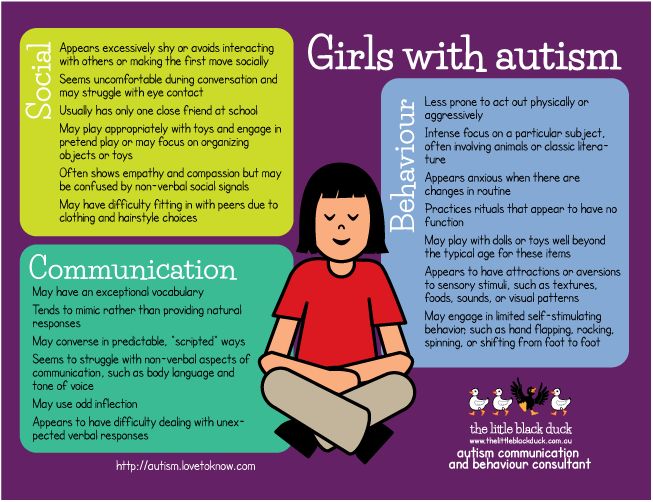

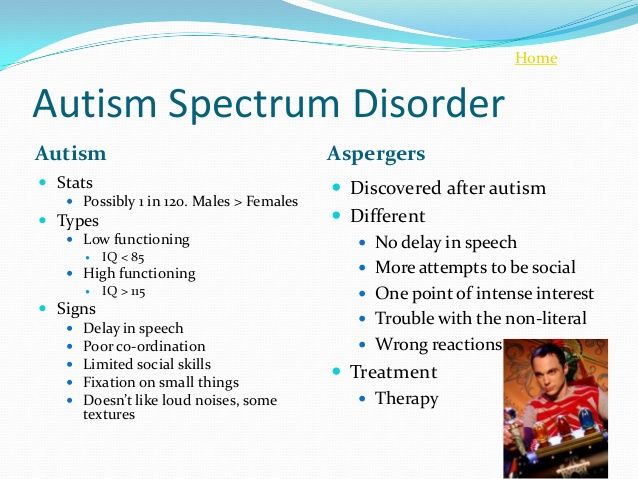

What distinguishes Asperger’s Disorder from classic autism are its less severe symptoms and the absence of language delays. Children with Asperger’s Disorder may be only mildly affected, and they frequently have good language and cognitive skills. To the untrained observer, a child with Asperger’s Disorder may just seem like a neurotypical child behaving differently.

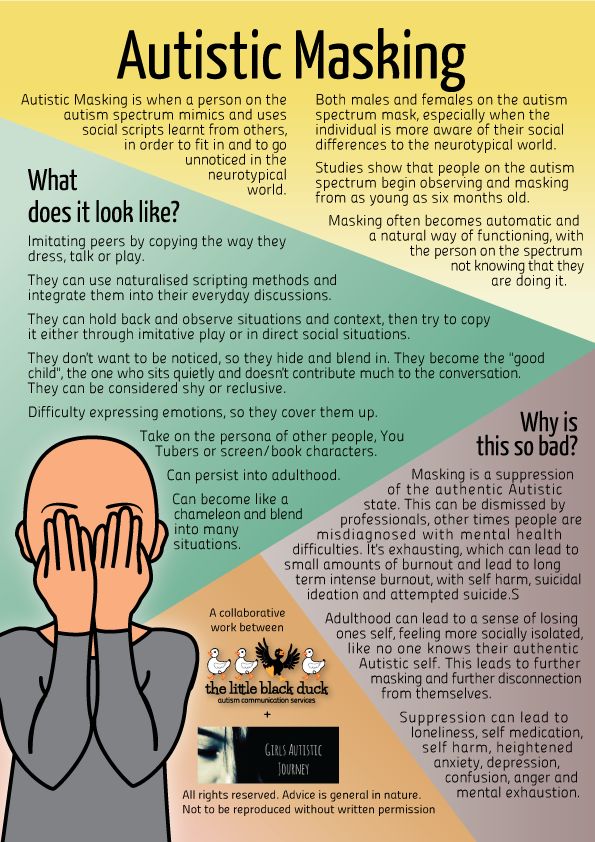

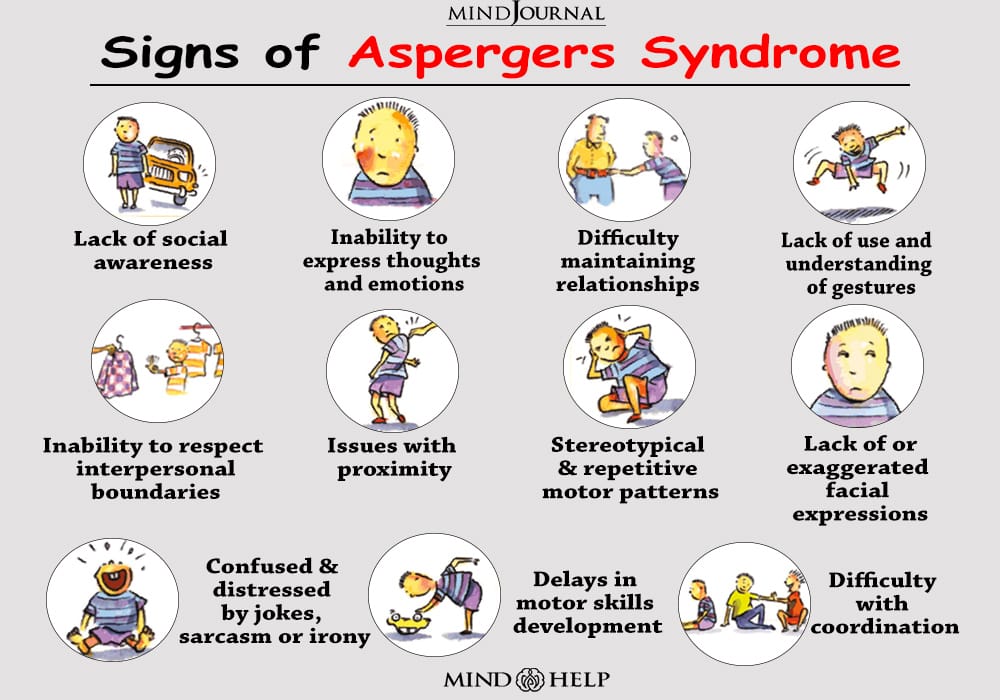

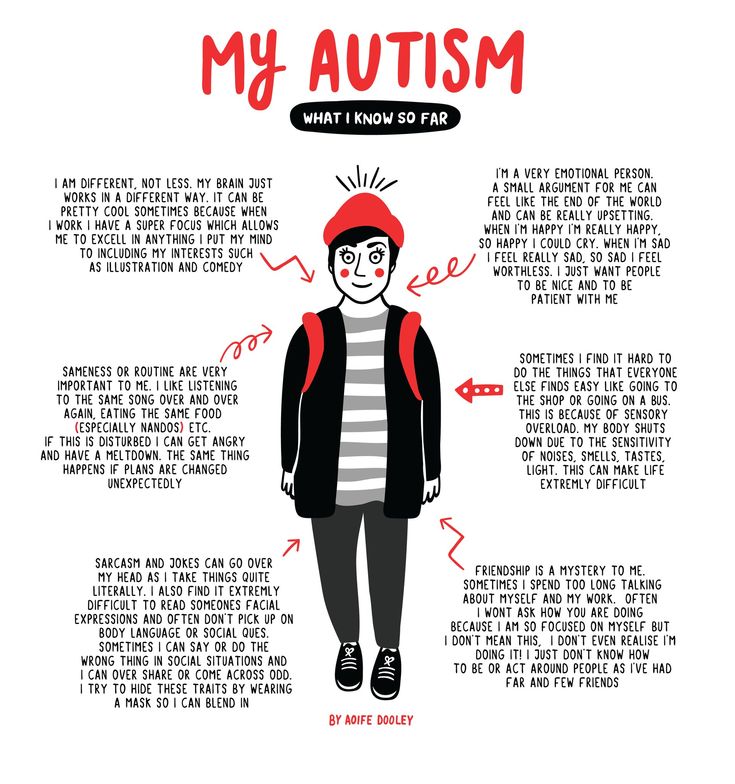

Children with autism are frequently viewed as aloof and uninterested in others. This is not the case with Asperger’s Disorder. Individuals with Asperger’s Disorder usually want to fit in and have interaction with others, but often they don’t know how to do it. They may be socially awkward, not understand conventional social rules or show a lack of empathy. They may have limited eye contact, seem unengaged in a conversation and not understand the use of gestures or sarcasm.

Their interests in a particular subject may border on the obsessive. Children with Asperger’s Disorder often like to collect categories of things, such as rocks or bottle caps. They may be proficient in knowledge categories of information, such as baseball statistics or Latin names of flowers. They may have good rote memory skills but struggle with abstract concepts.

One of the major differences between Asperger’s Disorder and autism is that, by definition, there is no speech delay in Asperger’s. In fact, children with Asperger’s Disorder frequently have good language skills; they simply use language in different ways. Speech patterns may be unusual, lack inflection or have a rhythmic nature, or may be formal, but too loud or high-pitched. Children with Asperger’s Disorder may not understand the subtleties of language, such as irony and humor, or they may not understand the give-and-take nature of a conversation.

Another distinction between Asperger’s Disorder and autism concerns cognitive ability. While some individuals with autism have intellectual disabilities, by definition, a person with Asperger’s Disorder cannot have a “clinically significant” cognitive delay, and most possess average to above-average intelligence.

While some individuals with autism have intellectual disabilities, by definition, a person with Asperger’s Disorder cannot have a “clinically significant” cognitive delay, and most possess average to above-average intelligence.

While motor difficulties are not a specific criterion for Asperger’s, children with Asperger’s Disorder frequently have motor skill delays and may appear clumsy or awkward.

Diagnosis

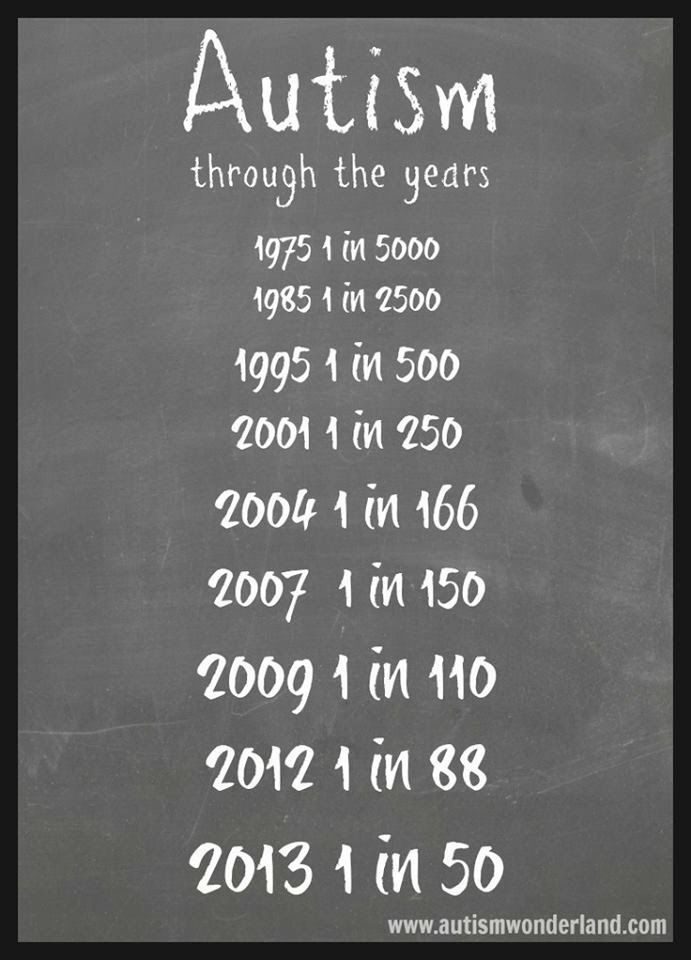

Diagnosis of Asperger’s Disorder has increased in recent years, although it is unclear whether it is more prevalent or more professionals are detecting it. When Asperger’s and autism were considered separate disorders under the DSM-IV, the symptoms for Asperger’s Disorder were the same as those listed for autism; however, children with Asperger’s do not have delays in the area of communication and language. In fact, to be diagnosed with Asperger’s, a child must have normal language development as well as normal intelligence. The DSM-IV criteria for Asperger’s specified that the individual must have “severe and sustained impairment in social interaction, and the development of restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests and activities that must cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning. ”

”

The first step to diagnosis is an assessment, including a developmental history and observation. This should be done by medical professionals experienced with autism and other PDDs. Early diagnosis is also important as children with Asperger’s Disorder who are diagnosed and treated early in life have an increased chance of being successful in school and eventually living independently.

Contact us for information on Asperger’s resources, including support groups and websites.

What is the difference between autism and Asperger’s?

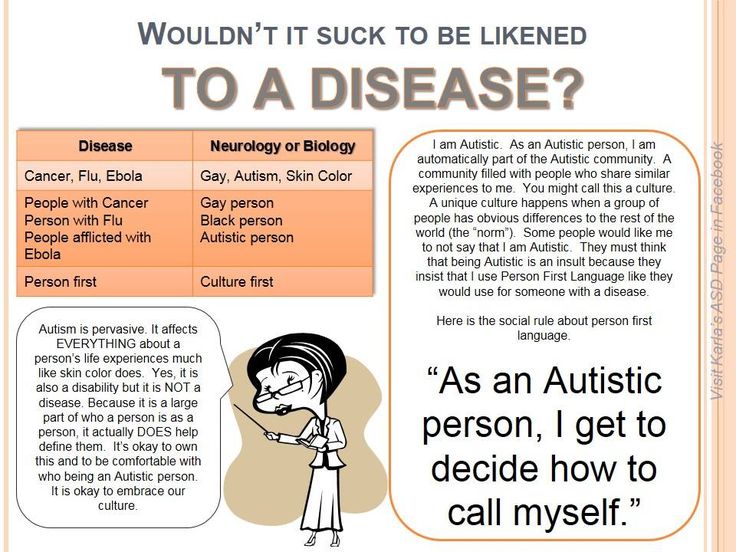

Asperger’s is no longer a standalone diagnosis, but it’s important to understand the difference between an autism diagnosis and an historical Asperger’s diagnosis. Learning the difference between autism and Asperger’s can impact how families approach treatment.

For over 70 years, doctors treated Asperger’s as its own diagnosis. Many professionals believed Asperger’s was a more mild form of autism, leading to the origin of the phrase “high-functioning”.

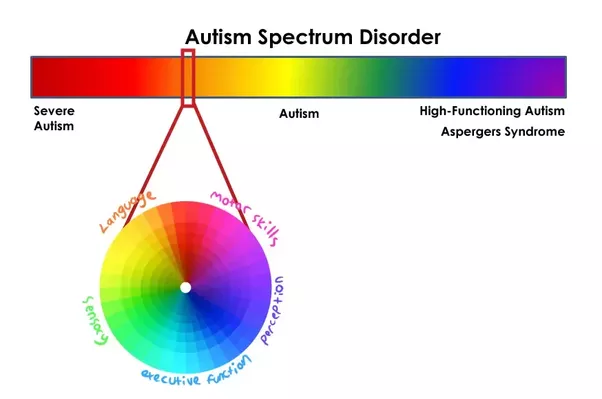

Now, children with Asperger’s symptoms are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Their symptoms are typically on the milder side, but every child experiences symptoms differently. Hence the word “spectrum” – ASD features a wide range of symptoms and experiences.

For example, some children with ASD are non-verbal or may have low IQs. Others have superior IQs and only minor social deficits.

No matter the symptoms, it’s important to get treatment for your child with ASD as soon as possible. Early intervention is one of the surest ways that your child will develop necessary life skills and become independent. At Therapeutic Pathways, we offer applied behavior analysis (ABA) treatment to help children develop those skills and live satisfying lives.

Keep reading to learn the history of Asperger’s. Then call Therapeutic Pathways at (209) 422-3280 for more information on treatment options.

History of Autism Diagnoses

Doctors used to think of Asperger’s Syndrome as a separate condition from autism. Because Asperger’s is associated with less severe symptoms and good language and cognitive skills, doctors issued this diagnosis to “high-functioning” children for decades.

Because Asperger’s is associated with less severe symptoms and good language and cognitive skills, doctors issued this diagnosis to “high-functioning” children for decades.

Asperger’s was identified by Austrian pediatrician Hans Asperger in 1944. He noticed that some children with autism had better-developed social and motor skills and fewer speech problems than their peers. He identified these children as having a condition similar to but undoubtedly unique from autism.

This disorder came to be known as Asperger’s, and it first appeared in the 1994 edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV).

Today, children experiencing developmental delays and symptoms of autism are instead more likely to be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). ASD is a broad category of developmental disorders that share some symptoms.

Many people believe this change is beneficial. An ASD diagnosis is more inclusive and reflects the fact that autism develops with a range of symptoms.

Range of Symptoms in ASD

Speech and Language

The principal difference between autism and what was once diagnosed as Asperger’s is that the latter features milder symptoms and an absence of language delays. Most children who were previously diagnosed with Asperger’s have good language skills but may have difficulty “fitting in” with their peers. They might feel uncomfortable or awkward, but their language skills were present.

Children with autism, on the other hand, typically exhibit problems with speech and communication. They may have difficulty understanding what someone is saying to them, or they may be unable to pick up on nonverbal cues like hand gestures and facial expressions.

Children with autism also frequently exhibit repetitive or “rigid” language as well as narrow topics of interest. For example, a child with autism may be interested in basketball and only talk about that sport.

Cognitive Functioning

Another difference between autism and what was diagnosed as Asperger’s was in cognitive functioning. By definition, a person with Asperger’s cannot have a “clinically significant” cognitive delay as is usually seen among children with autism. Children on the “lower end” of the spectrum (what was once diagnosed as Asperger’s) have average to above-average intelligence, while other children on the spectrum usually had significant cognitive delays.

By definition, a person with Asperger’s cannot have a “clinically significant” cognitive delay as is usually seen among children with autism. Children on the “lower end” of the spectrum (what was once diagnosed as Asperger’s) have average to above-average intelligence, while other children on the spectrum usually had significant cognitive delays.

For example, a child with autism may have difficulty recognizing and responding appropriately to others’ thoughts and feelings.

Age of Onset

One more difference between autism and Asperger’s is the age of onset, or the age at which a child receives a diagnosis. The average age of diagnosis for a child with autism is four, while a person with Asperger’s may not receive a diagnosis until they are a teenager or adult.

This may be because children with Asperger’s do not exhibit language delays or have lower IQs. Many parents may not realize their child has a developmental delay until they begin school and engage in more social interactions.

Treatment for Children with Autism

Learning about the difference between autism and Asperger’s is helpful, but taking action is even more important. At Therapeutic Pathways, we encourage parents to seek treatment for their child as early as possible. Research suggests that early intervention provides the best opportunity for children to learn valuable independent life skills.

For more information about treatment options, contact Therapeutic Pathways at (209) 422-3280.

How is Asperger's syndrome different from autism?

Asperger's syndrome is one of the autism spectrum disorders. Its symptoms appear in a milder form than the symptoms of autism. The causes of Asperger's Syndrome are not exactly known, but, as with autism, it is believed that they lie in the genetic predisposition and the influence of external factors on a person's prenatal development. In both disorders, there are changes in the brain, but exactly how they appear and develop is not completely known. Correction of the symptoms of this disorder occurs using the same methods as in the treatment of childhood autism.

Correction of the symptoms of this disorder occurs using the same methods as in the treatment of childhood autism.

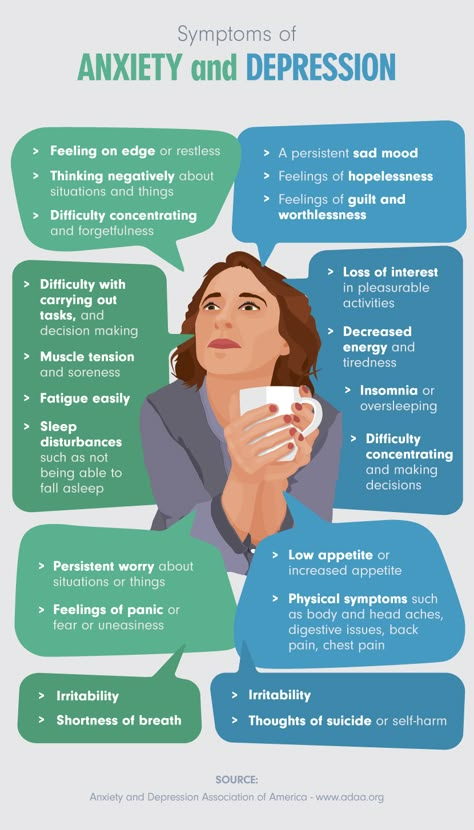

The main symptoms of autism spectrum disorders are problems in social interaction with others, unwillingness to make contact, lack of empathy and inadequate perception of generally accepted norms and concepts. However, people with Asperger's syndrome function much better in society than those with autism. Problems with speech and learning in such a person are less pronounced. People with Asperger's Syndrome may react inappropriately to social interactions and often come across as insensitive. They are able to theoretically understand the emotions of other people and learn empathy, but they usually find it difficult to put their knowledge into practice.

A child with Asperger's may excel in activities that require attention to detail, such as math, music, or art.

Often people with Asperger's syndrome show limited interests in very specific areas, not seeing or understanding the larger context. To a large extent, this is also true for autistic people. They can also focus mainly on some narrow topics. For example, watch only a certain TV show or play only one toy. This feature can also have a positive side. A child with Asperger's may excel in activities that require attention to detail, such as math, music, or art.

To a large extent, this is also true for autistic people. They can also focus mainly on some narrow topics. For example, watch only a certain TV show or play only one toy. This feature can also have a positive side. A child with Asperger's may excel in activities that require attention to detail, such as math, music, or art.

See also

Myths about autism

Famous people of the past are believed to have suffered from autism spectrum disorders such as musician Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and physicist Albert Einstein. Among our contemporaries, one can single out environmentalist Greta Thunberg, who considers her diagnosis of Asperger's Syndrome a gift that defines her vision of the world "in very black and white." Another striking example of a person with such a disease is the writer, mathematician and computer scientist Daniel Tammet. He set himself the task of explaining to healthy people how the inner world of a person suffering from an autism spectrum disorder works.

For both autism and Asperger's syndrome, treatment is aimed at improving symptoms and functioning in society.

Asperger's syndrome and autism are usually diagnosed in children aged 1.5-2 years. Sometimes you can immediately see that the child has some problems in socialization, but in general, he communicates with others adequately. However, it is more likely that Asperger's syndrome can be detected precisely in dynamics, after several years of treatment, after diagnosing autism in a child. The diagnosis of autism and Asperger's syndrome usually occurs after a meeting of a psychiatrist, child psychologist, occupational therapist and speech therapist with the child and his parents.

Autism is treated exclusively with behavioral therapy. In the case of Asperger's syndrome, starting from the late teens, the patient is prescribed treatment with cognitive behavioral therapy. For both autism and Asperger's syndrome, treatment is aimed at improving symptoms and functioning in society. Specialists try to teach the child those social skills that correspond to his age, and which he did not manage to acquire on his own. Patients with autism spectrum disorders are often prescribed medication to reduce symptoms. However, in the case of Asperger's syndrome, the effective drugs are less obvious than in autism.

Specialists try to teach the child those social skills that correspond to his age, and which he did not manage to acquire on his own. Patients with autism spectrum disorders are often prescribed medication to reduce symptoms. However, in the case of Asperger's syndrome, the effective drugs are less obvious than in autism.

Symptoms generally improve with age in children with Asperger's syndrome, although difficulties in social interaction with others may persist. It is understanding how the disease develops and how treatment works that helps determine what the future holds for a child with autism spectrum disorder, and what his symptoms may develop into.

- Autism

Share:

What is autism? Definition and symptoms

16.03.14

Information and messages about autism are so contradictory that it can be difficult for people who are "out of touch" to understand: what is the difference between an autistic person and a "normal" person? This material briefly describes the main approaches to the definition of autism

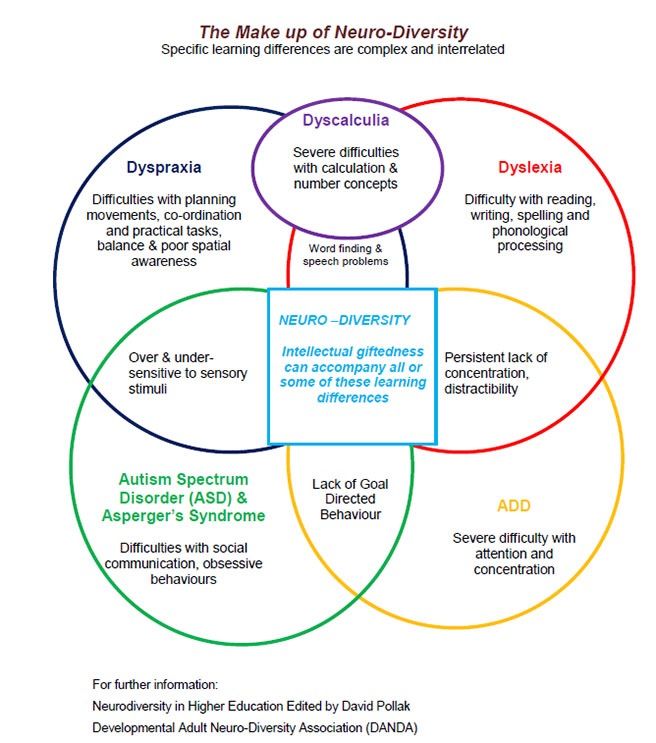

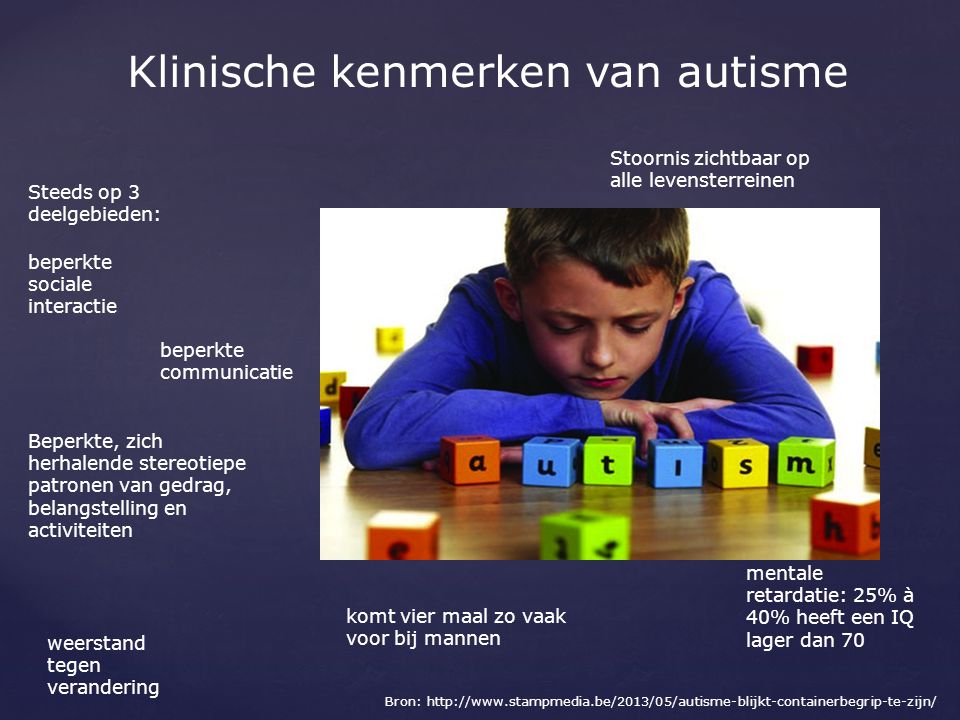

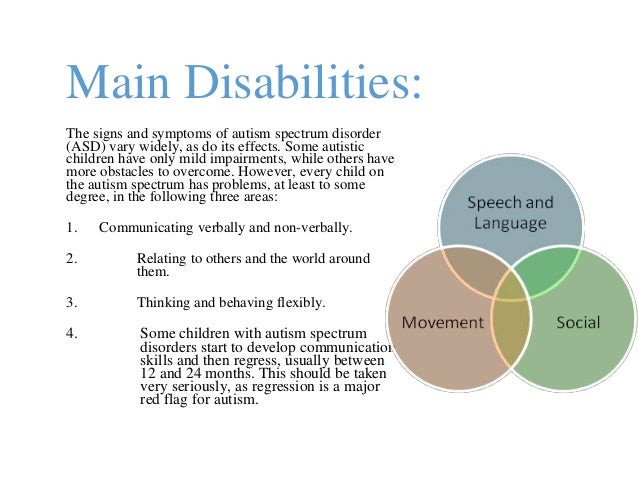

0003 Describing autism is quite a challenge. As a result, it is impossible to give a universal definition of autism. For example, one person with autism may have many sensory issues, including hypersensitivity to volume and high-pitched sounds, while another person may have no sensory sensitivity at all. One has to be satisfied with a very general definition, for example: Autism is a developmental disorder, neurological in nature, that affects the person's thinking, perception, attention, social skills and behavior . Of course, such a definition will tell you very little concrete information. Another problem is that the vast majority of studies and descriptions of autism are devoted to the diagnosis of children and the impact of autism on the tasks of child development - games with peers, learning skills, family relationships and so on. Most descriptions of what autism is begin with citations of diagnostic criteria from the International Classification of Diseases or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR), but this may be misleading, as these manuals are tools for diagnosis, not for description and understanding. In fact, these lists of criteria do not tell us what autism is, they only tell us how to decide whether a patient has autism or not. As mentioned earlier, one of the features of autism is the incredible number of possible signs that accompany it, and this leads to HUGE diversity among people with autism. In order to make a correct diagnosis despite this variety of manifestations, compilers of diagnostic guidelines must discard all variable features. They are trying to describe only the key, basic symptoms of autism, which are expressed in all patients with this disorder. Although there is no official confirmation of this, it seems that the compilers of the DSM were guided by the so-called "triad of disorders", which was proposed in their groundbreaking 1979 paper by Dr. Lorna Wing and Dr. Judith Gould from England (Wing & Gould, 1979). This is sometimes referred to as the "Camberwell Study". These researchers attempted for the first time to isolate the basic features of autism that were found in all children with autism from a large sample. They identified three key areas of impairment that seemed to be present in all of these children: 1. 2. Craving for stereotypical or repetitive behavior instead of imaginative activities. 3. Absence or delay in speech, or characteristic differences in speech. The DSM classification uses a slightly more complicated formula (at least two symptoms from category 1 and at least one of the symptoms from categories 2 and 3) based on the following three categories: 1. Qualitative disorders of social interaction (the ability to share, maintain friendships, carry on a conversation, and so on). 2. Qualitative communication disorders. 3. Restricted repetitive or stereotyped behavior patterns, interests and activities. Wing and Gould's article also pioneered the term "autism spectrum". Wing and Gould subsequently abandoned a separate category for stereotypical behavior and referred it to violations of the "social imagination". The triad of disorders or diagnostic model of autism is our first and main description of autism. The autism diagnostic model is closely related to diagnostic terms. There are several "kinds" of autism, or rather several terms for autism, that you may come across: Autism The word "autism" is both a specific diagnosis and a general term for all disorders associated with autism. In this text, the word "autism" is used in a second, general sense, and not as a diagnostic term. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) The term autism spectrum disorder covers all conditions associated with autism and reflects the great diversity among people with autism. Wing and Gould noted that there was an impression of a continuum or spectrum of autism symptoms. At that time, there was no formal definition for ASD (although it was added in the fifth edition of the DSM). However, until recently it was an informal term widely accepted in the autism community. People with autism are often said to be "on the autism spectrum" or "have ASD". Pervasive developmental disorder, unspecified Pervasive developmental disorder is a general term that includes autism, Asperger's syndrome, and several other disorders. When a patient appears to have some type of autism but does not quite fit the diagnostic formula, the patient is diagnosed with pervasive developmental disorder unspecified or atypical autism. High functioning autism This is another commonly used term, although it does not have a diagnostic definition. It is used in relation to people who have pronounced symptoms of autism, but at the same time they have well-developed speech skills, and the level of intelligence is relatively "normal". The opposite of high-functioning autism is not "low-functioning autism" at all, as some people think. This is "classic autism" or "Kanner's autism" (named after Leo Kanner, who first described autism). Asperger's Syndrome This diagnostic term is used for people with autism who also have very good language skills (plus they may have other less noticeable differences). There is debate about whether Asperger's syndrome is different from high-functioning autism or from the general diagnosis of autism, or whether it should be treated as a completely separate disorder. People with Asperger's face unique challenges in life. Since their speech abilities are very high, the people around them (including professionals) assume that their social and life skills are as developed as their speech. This assumption is erroneous, since without exception, people with autism have significant problems with social skills, and this affects their educational and employment opportunities. Most professionals use the terms Asperger's Syndrome and High Functioning Autism interchangeably. Most experts agree that people with Asperger's are people with autism. However, the opposite is not true: not all people with autism have Asperger's. We can say that Asperger's syndrome is a subtype of autism. Sensory processing disorder is a concept developed by occupational therapist A. Jean Ayres in the 1960s. Based on this model, behavioral problems and learning disabilities in autism are related to how a person receives, processes and responds to information from the senses. The sensory signals that the brain receives are "typical" in themselves, but it is difficult for the brain to "make sense" of these signals. Sensory information includes sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste, sense of balance and proprioception (joint-muscular sense). A person with autism may perceive these sensory cues as being uncomfortably strong (lights are too bright, sounds are too loud or harsh, and so on), or too weak or simply incomprehensible. In the context of autism, it is very interesting to compare this idea with an article by Marjorie Olney (Olney, 2000), in which she analyzed the autobiographical accounts of people with autism and identified common features of their experience. Among the data of her research were the following: Sensations. People with autism frequently reported having "altered" sensitivity to sounds, touch, sights, tastes, smells and movements. One of the authors recalled that as a child, when she looked at other people, she saw only scattered parts of the body, and not people as a whole. Many people with autism have reported that sounds or visual information in the background is too distracting for them to filter out. On the other hand, altered sensations are often a source of great enjoyment for many people with autism. Attention. Many people with autism report difficulty paying attention to more than one sensation at a time. For example, if they are listening to something, they may not be able to simultaneously perceive what they see. Perception of time and space. Some people with autism have reported severe problems with orientation in time and space that prevent them from understanding what will happen next. As with sensory issues, their perception of time and space may have been reduced or fragmented. As a result, they may not understand “what is happening” in the most ordinary situation, and also experience extreme anxiety in case of waiting, changing plans, or moving to another activity. In situations like this, people with autism seem to be very helped by familiar activities and objects, as well as a rigid routine. Self-regulation strategies. Some people with autism say that repetitive movement calms them and helps them cope with hypersensitivity. Others say that such movements help them think or focus. For some people with autism, self-regulation strategies include rigid daily routines and daily routines. For example, it can be sorting things and storing them in a strictly defined place. This obsession with routine and order seems to help people with autism cope with severe anxiety, including difficulty orienting themselves in time and space. Olney's list of features from autobiographical descriptions of autism demonstrates similarities with the concept of sensory processing disorder. All together they can be considered as the third model of autism. This experiential/sensory processing model does not tell us anything about the causes of autism, but it does allow us to begin to understand how the different elements of the triad of disorders relate to each other. The Functional Model of autism does not explain its causes or attempt to link its features together. This is simply a listing of the various features of autism that a person may have. Such a list is useful for professionals, as it allows you to identify specific features that affect a specific life task, and then proceed to plan support methods and possible services. Measured level of intelligence. "Intelligence" in people with autism can vary widely, from very low to very high. Concrete thinking. People with autism often think very concretely rather than abstractly. Their perception of the world can be extremely limited, intense and detailed. This can lead to difficulty understanding complex speech. People with autism learn more easily from demonstrations, visual examples, or diagrams than from verbal instructions. When it comes to language, people with autism often interpret speech expressions literally. Phrases such as "Keep your mouth shut", "We'll meet later", "Cheap words" can confuse them. A literal understanding or ignorance of the hidden meaning can cause negative feelings towards other people, since a person with autism may perceive a non-binding agreement as a firm promise or consider life advice to be a hard and fast rule. Attention to detail. Some people with autism have a developed ability to focus on details and notice patterns. Fixation. Very often, people with autism have a fixation on a favorite topic or activity (this feature is part of the diagnostic criteria). Such people have a very strong motivation to experience, study and think about their favorite topic, and if they have developed the ability to speak, often such people constantly talk about their favorite topic, because of which they can monopolize the conversation. Some people are attracted to ordered systems such as computers, lists of information, or special kinds of machinery (such as light bulbs or vending machines). Also, a person with autism may have a fixation on the rhythm of words, counting, or lists of objects. Non-speaking people may have fixations on feeling certain surfaces, repeating complex rituals, or rocking back and forth. A person with autism's knowledge of a favorite topic or activity can be surprisingly deep, but perhaps also very narrow. Also, a person with autism may not understand that other people are not interested in this topic. However, if a person's instructions, responsibilities, or job tasks are consistent with their personal fixations, then those fixations can become highly functional. Expressive language (oral speech, communication with other people). Some people with autism have advanced language skills and an extensive vocabulary. Others have very limited speech skills. Many people with autism, even those with advanced language skills, express emotions through behavior rather than words, but the meaning of a particular behavior varies from person to person. It is very important that the people around each person with autism understand the meaning of their behavioral language. Receptive language (listening to speech, understanding other people). A person with autism may also need extra time to answer a question or make a decision. Visual information (diagrams, color coding, symbolic images, written information, and so on) can help a person with autism to better understand other people's speech. Social interaction. The social skills of people with autism can be very different, but they all have some difficulty in perceiving social cues. Some people with autism seem to be immersed in their inner world (although in reality they may be acutely aware of everything that is going on around them). Other people with autism may be very outgoing and people-oriented, but still find it difficult to correctly understand social situations and choose appropriate responses. Almost all people with autism can benefit from some form of social skills training. Eye contact. Lack of eye contact is one of the most noticeable features of people with autism, especially when talking to other people. Others may mistakenly perceive the lack of eye contact as inattention, shyness, rudeness, or some kind of negative emotion. People with autism do not perceive eye contact as important, and for some, eye contact causes discomfort. Some people with autism find that making eye contact requires so much concentration that they cannot simultaneously focus on what the other person is saying. Routine adherence. People with autism often value established routines highly, and in any new environment quickly develop new routines. Changes in the usual order can be very frustrating for them, so it is always advisable to describe in advance in detail the upcoming changes to them. In some cases, the routines of a person with autism can become so rigid that they resemble obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dependence on hints and difficulty generalizing. Routines are highly valued by people with autism and are often tied to specific elements of the environment. When such clue elements disappear from the familiar situation, the routine falls apart completely, which can lead to confusion, anxiety and dissatisfaction. Also remember not to teach a person with autism a skill in one setting and then ask them to repeat that skill in a completely different setting. Generalizing a skill to different situations is difficult for people with autism, and one should, whenever possible, teach the person in a close environment, using the same cues as in the natural environment. Gross motor problems. Such difficulties may be expressed in general clumsiness, strange posture and gait, difficulty walking or other movements. Fine motor problems. Difficulty grasping small objects, writing by hand, etc. The term "theory of mind" does not describe this model very well, but it is often used. Some experts believe that understanding the theory of mind is one of the most important facts that everyone who works with people with autism needs to know. Theory of mind is the innate ability to predict/imagine/understand what other people might think, or how a situation looks from another person's point of view. For example, having written the previous sentence, the author might think that it is not very clear, and readers may not understand what exactly is meant, perhaps another sentence is needed to clarify this. This is the model of the mind - the ability to imagine that people reading this sentence do not know the same as the author about the theory of the mind. Another example is if you are going to comment on someone's behavior, and you think that your comment might upset the other person, then you are using the theory of the mind. However, it is often difficult for people with autism to understand what other people think, feel or know. As Emmett puts it, “What if I don’t know that your experience is different from mine? What if some sound is REALLY bothering me, but I'm sure it bothers everyone equally, so I just have to bite the bullet and endure? What if today my leg hurts a lot when walking, but I don’t realize that you can’t know about it? When people are unable to predict/understand what other people think about the same situation differently from themselves, then they are "not based on the theory of mind". British researcher Simon Baron-Cohen has written extensively about this aspect of autism. In papers since the original Camberwell study, Wing and Gould replaced "interest in stereotyped or repetitive behavior" with "lack of social imagination" (essentially their version of the theory of the mind) as one of the autism triads. (And this is also not the first mention of the theory of mind, it is much older). Like autism itself, the theory of the mind is a whole continuum, so it cannot be said that it is either present or completely absent. People with autism often understand that others think differently than they do, but it can still be difficult for them to figure out exactly what other people think. The theory of mind explains one of the features of autism that the other models mentioned here cannot explain. However, it is by no means a complete model of autism—it does not explain many of the other symptoms of autism, nor does it say anything about its cause. None of these models can fully explain or describe autism. In addition, there are other models (neurological, biomedical, and so on) that look at other aspects of autism. It is very important to remember that when you are dealing with a person with a disability, the most important thing is to get to know that particular person, his or her characteristics and needs. These models simply give us general patterns from which we can better understand this or that person with autism. This is partly due to the fact that medical researchers do not yet know what exactly causes it, and what processes in the body and brain lead to this disability. Another reason is that the huge variety of symptoms and manifestations is itself a feature of autism spectrum disorders.

This is partly due to the fact that medical researchers do not yet know what exactly causes it, and what processes in the body and brain lead to this disability. Another reason is that the huge variety of symptoms and manifestations is itself a feature of autism spectrum disorders.  Although the symptoms of autism do not change after a person with autism becomes an adult, the various manifestations of autism become less or more important as a result of changes in life requirements. Thus, it is not always easy to understand exactly how such a complex disorder affects the lives of adults. Several models of understanding autism are described below, each of which partially answers these questions.

Although the symptoms of autism do not change after a person with autism becomes an adult, the various manifestations of autism become less or more important as a result of changes in life requirements. Thus, it is not always easy to understand exactly how such a complex disorder affects the lives of adults. Several models of understanding autism are described below, each of which partially answers these questions. Diagnostic model

Many of these features are not universal. This means that although everyone has at least some of them, no one has them all, and each person experiences different symptoms. For doctors diagnosing autism, this is a big problem.

Many of these features are not universal. This means that although everyone has at least some of them, no one has them all, and each person experiences different symptoms. For doctors diagnosing autism, this is a big problem.  Communication disorders (reduced level or lack of age-appropriate social contacts with other people).

Communication disorders (reduced level or lack of age-appropriate social contacts with other people).  The problem is that it was designed to answer only one question: "Does this person have autism?" She can't answer questions like, "What's it like to have autism?" or “How does autism affect daily life?” This model also excluded a number of important features associated with autism, simply because not all people with this diagnosis have them. Moreover, it does not help us to understand how these three types of "violations" are related to each other.

The problem is that it was designed to answer only one question: "Does this person have autism?" She can't answer questions like, "What's it like to have autism?" or “How does autism affect daily life?” This model also excluded a number of important features associated with autism, simply because not all people with this diagnosis have them. Moreover, it does not help us to understand how these three types of "violations" are related to each other. Diagnostic terms

The terms ASD and autism in the general sense discussed above are synonymous. Wing and Gould noted in their study that although the current description of autism (the first description of autism published by psychiatrist Leo Kanner in 1943) fit many children well, there were an equal number of children who only partially fit the description.

The terms ASD and autism in the general sense discussed above are synonymous. Wing and Gould noted in their study that although the current description of autism (the first description of autism published by psychiatrist Leo Kanner in 1943) fit many children well, there were an equal number of children who only partially fit the description.  Often these are people with "lower" functioning than people with a formal diagnosis of autism, but not necessarily.

Often these are people with "lower" functioning than people with a formal diagnosis of autism, but not necessarily.  The term "Asperger's Syndrome" was coined by Lorna Wing, the author of the term "Autism Spectrum Disorder".

The term "Asperger's Syndrome" was coined by Lorna Wing, the author of the term "Autism Spectrum Disorder". Sensory Experience/Processing Model

Such a disorder is not included in official diagnostic guidelines, and opinions differ regarding it - some believe that it is a separate disorder, and others that it is just a collection of similar symptoms that occur in various developmental disorders. However, issues of sensory perception are very often discussed when it comes to autism spectrum disorders, and this is a very interesting approach to understanding autism (Flanagan, 2009).

Such a disorder is not included in official diagnostic guidelines, and opinions differ regarding it - some believe that it is a separate disorder, and others that it is just a collection of similar symptoms that occur in various developmental disorders. However, issues of sensory perception are very often discussed when it comes to autism spectrum disorders, and this is a very interesting approach to understanding autism (Flanagan, 2009).  It is hypothesized that sensory processing in autism requires such enormous concentration that the person becomes less aware of the environment, is constantly distracted or unable to concentrate, and often experiences irritation.

It is hypothesized that sensory processing in autism requires such enormous concentration that the person becomes less aware of the environment, is constantly distracted or unable to concentrate, and often experiences irritation.  They often enjoy situations and objects that other people don't even notice.

They often enjoy situations and objects that other people don't even notice.  Most people with autism reported having ways to calm down or manage their autism symptoms. Such strategies are often met with rituals, rhythmic activities, or repetitive behaviors. Interestingly, these self-soothing activities fit the diagnostic criteria for autism and the triad of Wing and Gould disorders. They seem almost universal to people with autism and can include rhythmic, repetitive movements such as rocking the torso, shaking the hands, bellowing under the nose, pacing back and forth, and other motions without a specific purpose.

Most people with autism reported having ways to calm down or manage their autism symptoms. Such strategies are often met with rituals, rhythmic activities, or repetitive behaviors. Interestingly, these self-soothing activities fit the diagnostic criteria for autism and the triad of Wing and Gould disorders. They seem almost universal to people with autism and can include rhythmic, repetitive movements such as rocking the torso, shaking the hands, bellowing under the nose, pacing back and forth, and other motions without a specific purpose.

Functional Model of Autism

Cognitive sphere

The level of intelligence does not depend on the severity of autism symptoms.

The level of intelligence does not depend on the severity of autism symptoms.  They can easily notice that the books on the shelf are out of order, that the items on the table are stacked differently, or that not all of the data in the table fits together. This feature makes some people with autism very capable of detail-oriented work.

They can easily notice that the books on the shelf are out of order, that the items on the table are stacked differently, or that not all of the data in the table fits together. This feature makes some people with autism very capable of detail-oriented work.

Communication and two-way communication

Most (but not all) people with autism process information better visually than aurally. During a conversation, a person with autism needs long pauses to process verbal information.

Most (but not all) people with autism process information better visually than aurally. During a conversation, a person with autism needs long pauses to process verbal information.

Behavioral features

Similarly, some people with autism prefer a very orderly environment, they can arrange things in rows, align things, and so on. A person with autism may experience intense anxiety if things have been moved or if the room is in a lot of disorder.

Similarly, some people with autism prefer a very orderly environment, they can arrange things in rows, align things, and so on. A person with autism may experience intense anxiety if things have been moved or if the room is in a lot of disorder.

Model of the theory of mind

Conclusion on autism models