Intervention for adhd students

School Interventions - CHADD

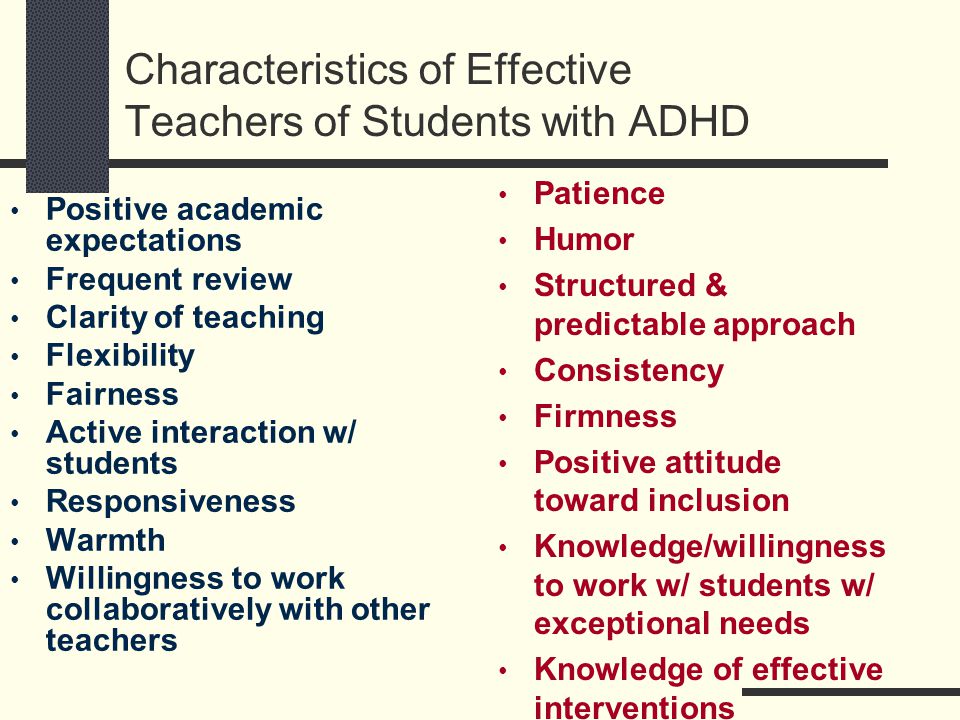

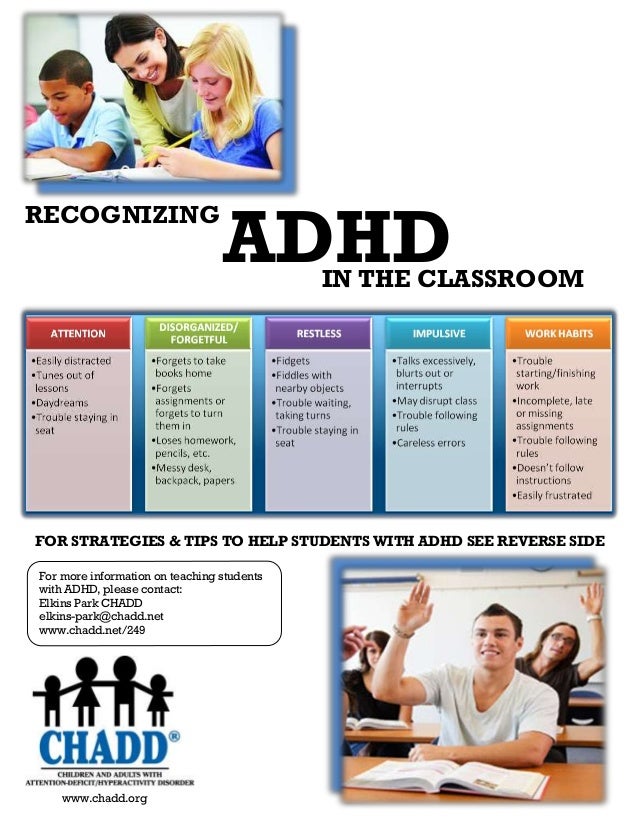

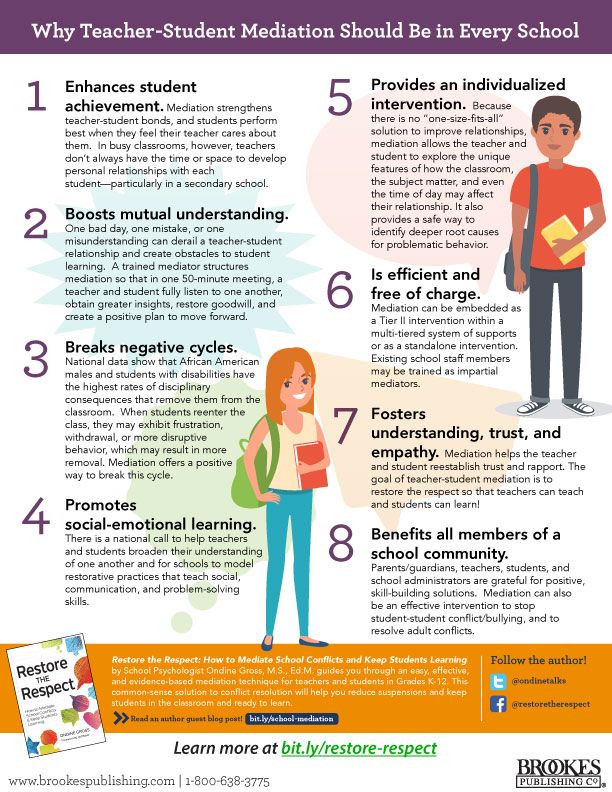

As is the case with parent training, the techniques used to manage ADHD in the classroom have been used for some time and are considered effective. Many teachers who have had training in classroom management are quite expert in developing and implementing programs for students with ADHD. However, because the majority of children with ADHD are not enrolled in special education services, their teachers will most often be regular education teachers who may know little about ADHD or behavior modification and will need assistance in learning and implementing the necessary programs.

There are many widely available handbooks, texts and training programs that teach classroom behavior management skills to teachers. Most of these programs are designed for regular or special education classroom teachers who also receive training and guidance from school support staff or outside consultants. Parents of children with ADHD should work closely with the teacher to support efforts in implementing classroom programs.

Managing teenagers with ADHD in school is different from managing children with ADHD. Teenagers need to be more involved in goal planning and implementation of interventions than do children. For example, teachers expect teenagers to be more responsible for belongings and assignments. They may expect students to write assignments in weekly planners rather than receive a daily report card. Organizational strategies and study skills, therefore, need to be taught to the adolescent with ADHD. Parent involvement with the school, however, is as important at the middle and high school levels as it is in elementary school. Parents will often work with guidance counselors rather than individual teachers so that the guidance counselor can coordinate intervention among the teachers.

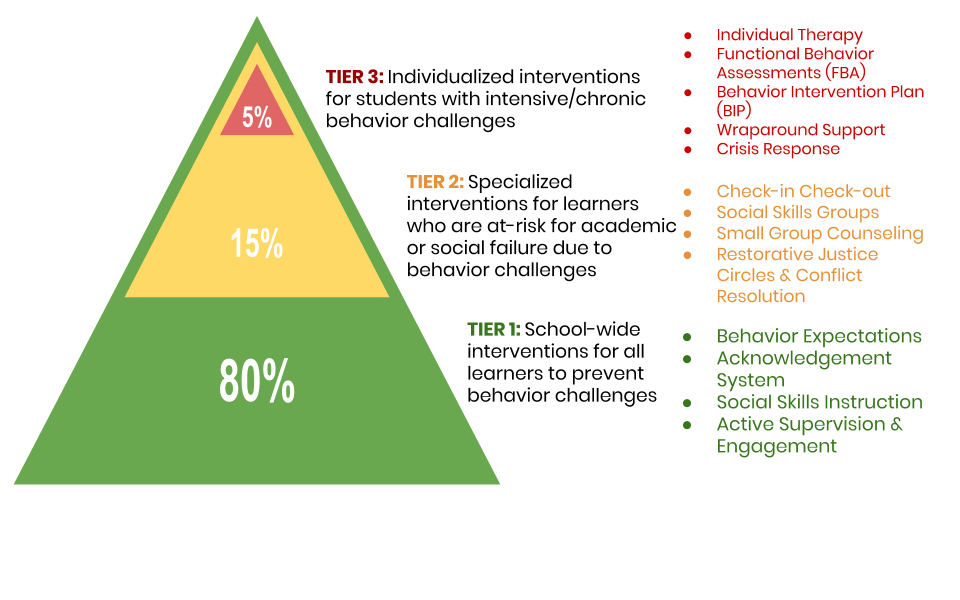

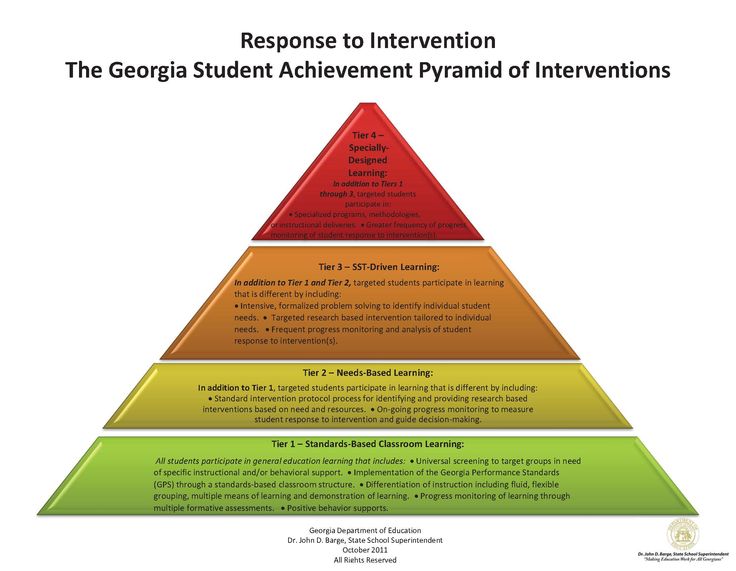

The following list includes typical classroom behavioral management procedures. They are arranged in order from mildest and least restrictive to more intensive and most restrictive procedures. Some of these programs may be included in 504 plans or Individualized Educational Programs for children with ADHD. Typically, an intervention is individualized and consists of several components based on the child’s needs, classroom resources, and the teacher’s skills and preferences.

Typically, an intervention is individualized and consists of several components based on the child’s needs, classroom resources, and the teacher’s skills and preferences.

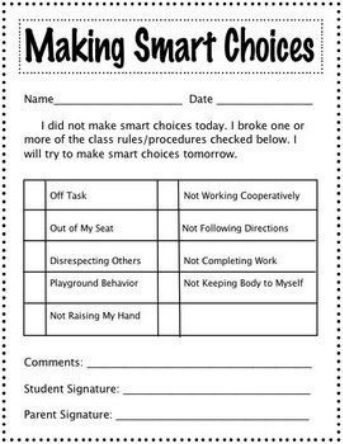

- Classroom rules and structure

- Use classroom rules such as:

- Be respectful of others

- Obey adults

- Work quietly

- Stay in assigned seat/area

- Use materials appropriately

- Raise hand to speak or ask for help

- Stay on task and complete assignments

- Post the rules and review them before each class until learned

- Make rules objective and measurable

- Tailor the number of rules to developmental level

- Establish a predictable environment

- Enhance children’s organization (folders/charts for work)

- Evaluate rule-following and give feedback/consequences consistently

- Tailor the frequency of feedback to developmental level

- Use classroom rules such as:

- Praise for appropriate behaviors and choosing battles carefully

- Ignore mild inappropriate behaviors that are not reinforced by peer attention

- Use at least five times as many praises as negative comments

- Use commands/reprimands to cue positive comments for children who are behaving appropriately—that is, find children who can be praised each time a reprimand or command is given to a child who is misbehaving

- Appropriate commands and reprimands

- Use clear, specific commands

- Give private reprimands at the child’s desk as much as possible

- Reprimands should be brief, clear, neutral in tone and as immediate as possible

- Individual accommodations and structure for the child

- Structure the classroom to maximize the child’s success

- Place the student’s desk near the teacher to facilitate monitoring

- Enlist a peer to help the student copy assignments from the board

- Break assignments into small chunks

- Give frequent and immediate feedback

- Require corrections before new work is given

- Proactive interventions to increase academic performance

Such interventions can prevent problematic behavior from occurring and can be implemented by individuals other than the classroom teacher, such as peers or a classroom aide. When disruptive behavior is not the primary problem, these academic interventions can improve behavior significantly.

When disruptive behavior is not the primary problem, these academic interventions can improve behavior significantly. - Focus on increasing completion and accuracy of work

- Offer task choices

- Provide peer tutoring

- Consider computer-assisted instruction

- “When…then” contingencies (withdrawing rewards or privileges in response to inappropriate behavior)

Examples include recess time contingent upon completion of work, staying after school to complete work, assigning less desirable work prior to more desirable assignments, and requiring assignment completion in study hall before allowing free time. - Daily school-home report card

This tool allows parents and teacher to communicate regularly, identifying, monitoring and changing classroom problems. It is inexpensive and minimal teacher time is required.- Teachers determine the individualized target behaviors

- Teachers evaluate targets at school and send the report card home with the child

- Parents provide home-based rewards; more rewards for better performance and fewer for lesser performance

- Teachers continually monitor and make adjustments to targets and criteria as behavior improves or new problems develop

- Use the report card with other behavioral components such as commands, praise, rules, and academic programs

- Behavior chart and/or reward and consequence program (point or token system)

- Establish target behaviors and ensure that the child knows the behaviors and goals (e.

g., list on index card taped to desk)

g., list on index card taped to desk) - Establish rewards for exhibiting target behaviors

- Monitor the child and give feedback

- Reward young children immediately

- Use points, tokens or stars that can later be exchanged for rewards

- Establish target behaviors and ensure that the child knows the behaviors and goals (e.

- Class wide interventions and group contingencies

Such interventions encourage children to help one another because everyone can be rewarded. There is also potential for improvement in the behavior of the entire class.- Establish goals for the class as well as the individual

- Establish rewards for appropriate behavior that any student can earn (e.g., class lottery, jelly bean jar, wacky bucks)

- Establish a class reward system in which the entire class (or subset of the class) earns rewards based on class functioning as a whole (e.g, Good Behavior Game) or the functioning of the student with ADHD

- Tailor frequency of rewards and consequences to developmental level

- Time out

The child is removed, either in the classroom or to the office, from the ongoing activity for a few minutes (less for younger children and more for older) when he or she misbehaves.

- Schoolwide programs

Such programs, which include schoolwide discipline plans, can be structured to minimize the problems experienced by children with ADHD, while at the same time help manage the behavior of all students in a school.

School-Based Intervention Strategies for Children with ADHD – ADD Resource Center

Image: Pebel BabySol Koemhong

International Christian UniversityTokyo, Japan

December 01, 2020

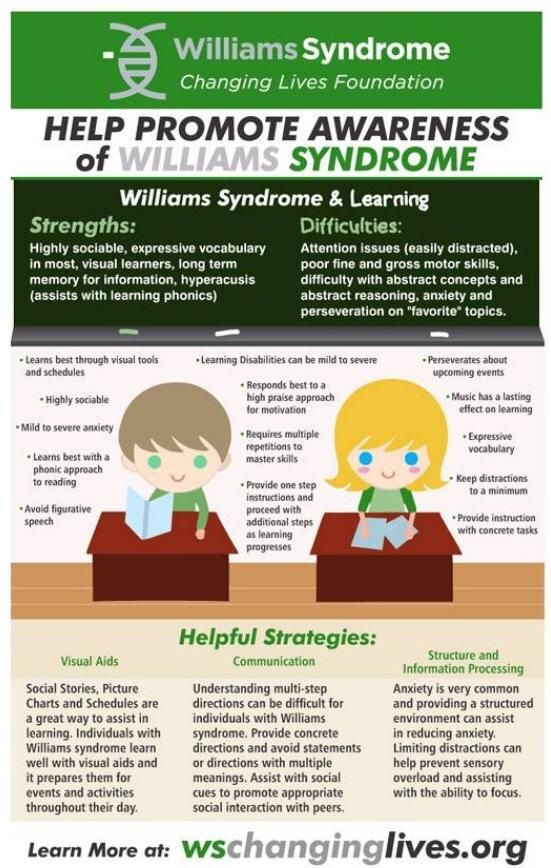

ADHD can significantly affect children’s physical and emotional well-being, academic achievements, and interactions with others.

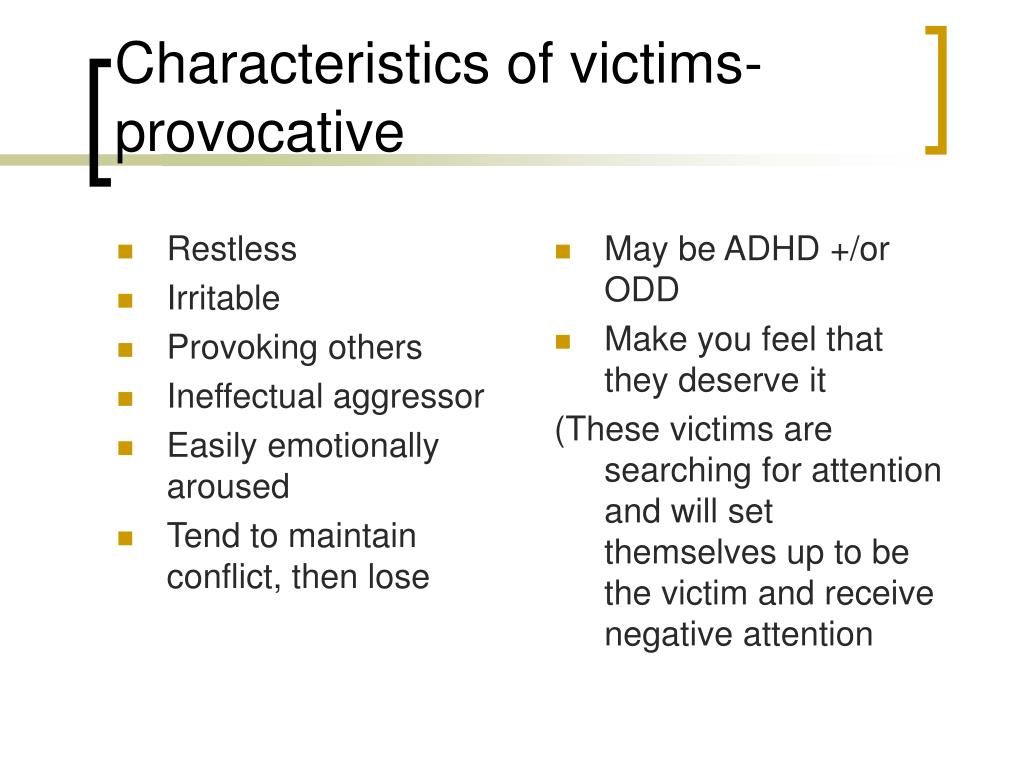

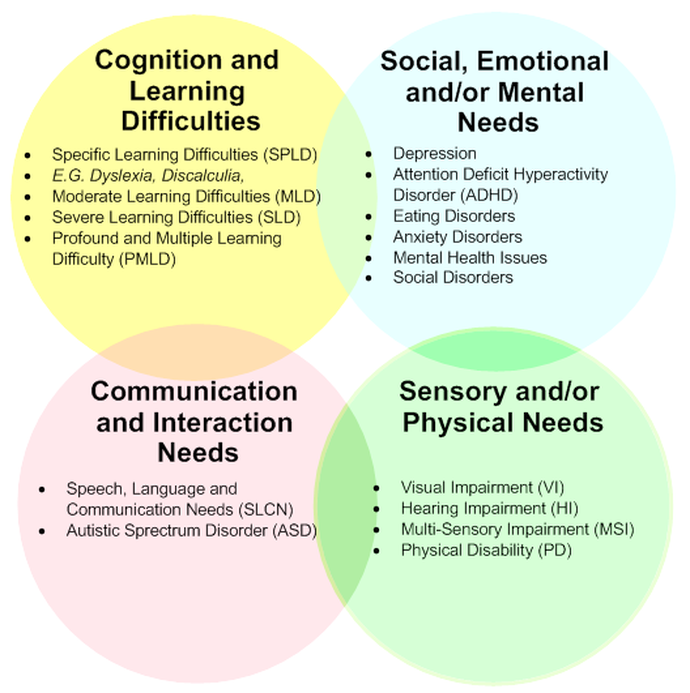

IntroductionADHD stands for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. It is known as one of the most common neurobehavioral disorders in children. Fox (2001) points out that ADHD is a term used to present people with behavioral impulsivity and low self-control and attention levels. There can be many reasons why a child becomes inattentive and disruptive in class; however, those presented with these behavioral problems can be regarded as possessing a form of ADHD (Meyer & Lasky, 2017). ADHD can significantly affect children’s physical and emotional well-being, academic achievements, and interactions with others. Children with ADHD appear to experience significant difficulties in a range of functions. Even though impulsivity, inattention, and overactivity are common, they can serve as an attraction of other difficulties (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003). DuPaul and Stoner emphasize that children with ADHD frequently experience low academic achievement, a high level of non-compliance and aggression, and poor relationships. This social and emotional impairment dramatically affects the quality of their life (Wehmeier et al., 2010).

ADHD can significantly affect children’s physical and emotional well-being, academic achievements, and interactions with others. Children with ADHD appear to experience significant difficulties in a range of functions. Even though impulsivity, inattention, and overactivity are common, they can serve as an attraction of other difficulties (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003). DuPaul and Stoner emphasize that children with ADHD frequently experience low academic achievement, a high level of non-compliance and aggression, and poor relationships. This social and emotional impairment dramatically affects the quality of their life (Wehmeier et al., 2010).

Therefore, understanding children with ADHD and taking appropriate interventions to support them are crucial to their future success. This article offers some suggested school-based intervention strategies to support children with ADHD.

There is no single exact cause of ADHD that can be fully understood. According to the National Health Service (NHS) of the United Kingdom, a combination of causes/factors is believed to contribute to ADHD, including genetics, brain function and structure, and other possible causes (NHS, 2018). The genes inherited from parents are an undeniable factor that explains the condition. Research indicates that both parents and siblings of children with ADHD are four to five times more likely to have ADHD themselves (NHS, 2018). However, it is difficult to understand how ADHD is inherited. Some differences in brain function and structure are also found in children with ADHD compared to those without ADHD (NHS, 2018). Other possible causes of ADHD include premature birth, low birth weight, brain damage, smoking and misuse of drugs during pregnancy, and exposure to high toxic levels (NHS, 2018).

The genes inherited from parents are an undeniable factor that explains the condition. Research indicates that both parents and siblings of children with ADHD are four to five times more likely to have ADHD themselves (NHS, 2018). However, it is difficult to understand how ADHD is inherited. Some differences in brain function and structure are also found in children with ADHD compared to those without ADHD (NHS, 2018). Other possible causes of ADHD include premature birth, low birth weight, brain damage, smoking and misuse of drugs during pregnancy, and exposure to high toxic levels (NHS, 2018).

Even though we can identify some characteristics of ADHD, it is not easy to be diagnosed because it is a highly hereditary neurobiological problem characterized by behavioral difficulties that may vary in intensity. Environment, attitude, and internal motivation can influence behaviors (Meyer & Lasky, 2017). Therefore, a child must be rigorously assessed. The American Psychiatric Association (2013) provides a comprehensive list of criteria that can be used to diagnose ADHD (see Appendix).

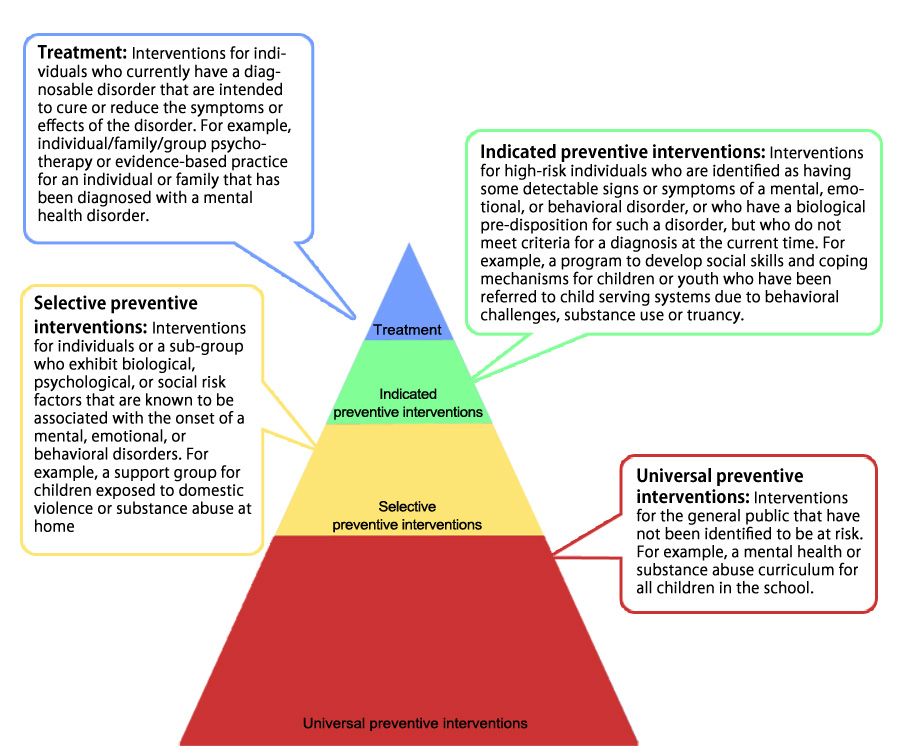

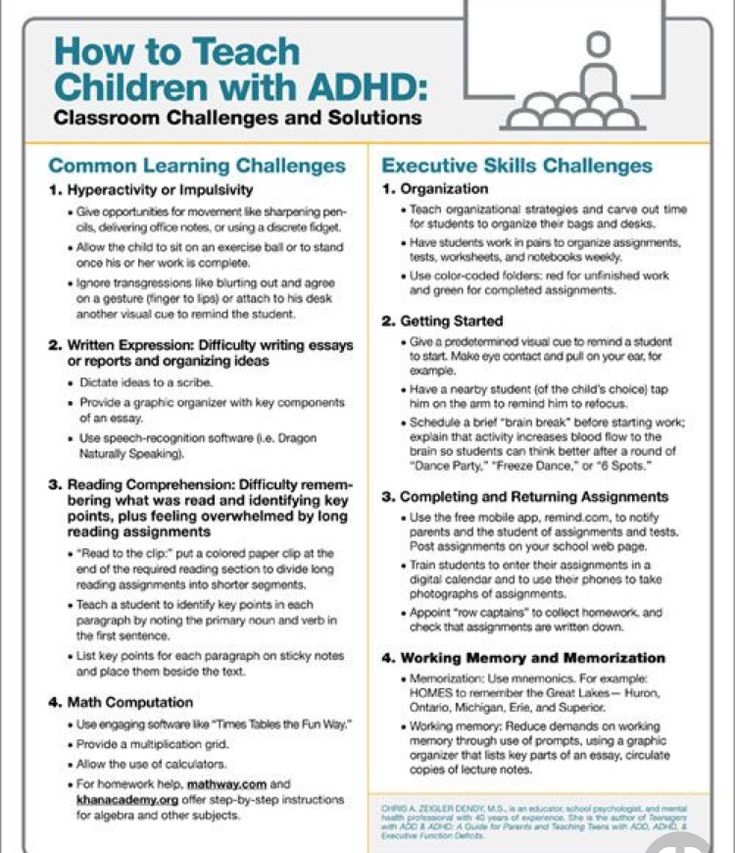

Suggested School-Based Intervention Strategies

Many studies reported that children diagnosed with ADHD experience considerable challenges with their academic life. They are at significant risk for poor academic achievement, behavior, and social interaction; therefore, a systematic and ongoing school-based approach is necessary to help them succeed in school (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003). From here onwards, some suggested school-based intervention strategies to support children with ADHD will be discussed. The discussion will be based mainly on the work of DuPaul and Stoner, who are leading researchers in the field of special education.

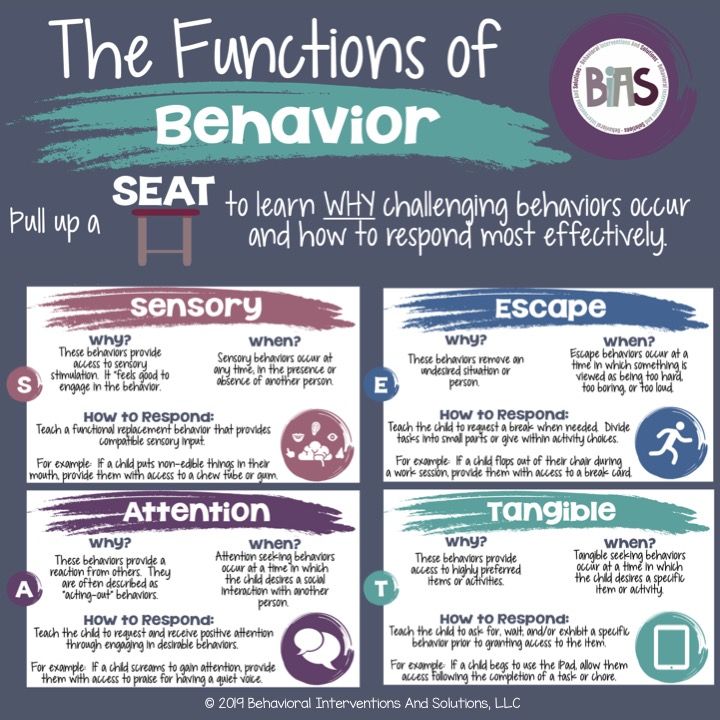

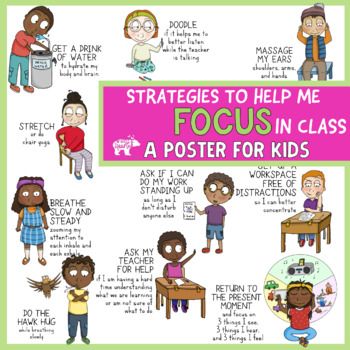

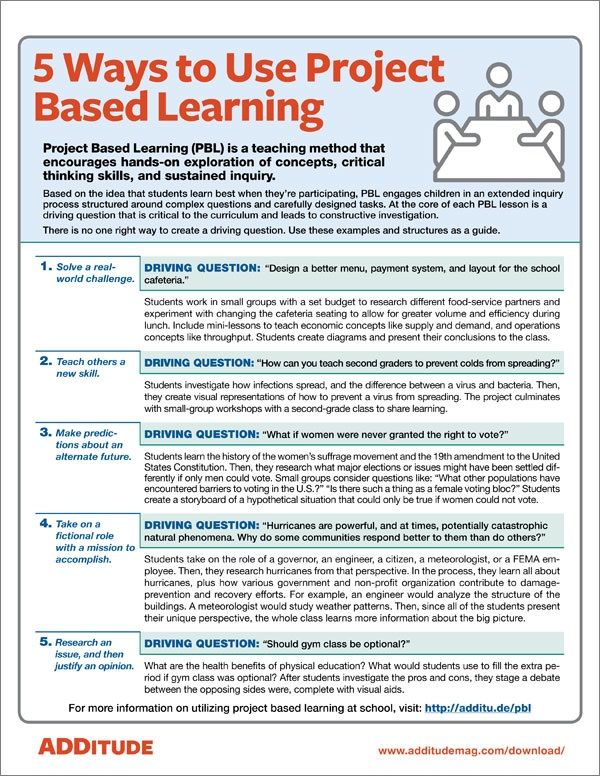

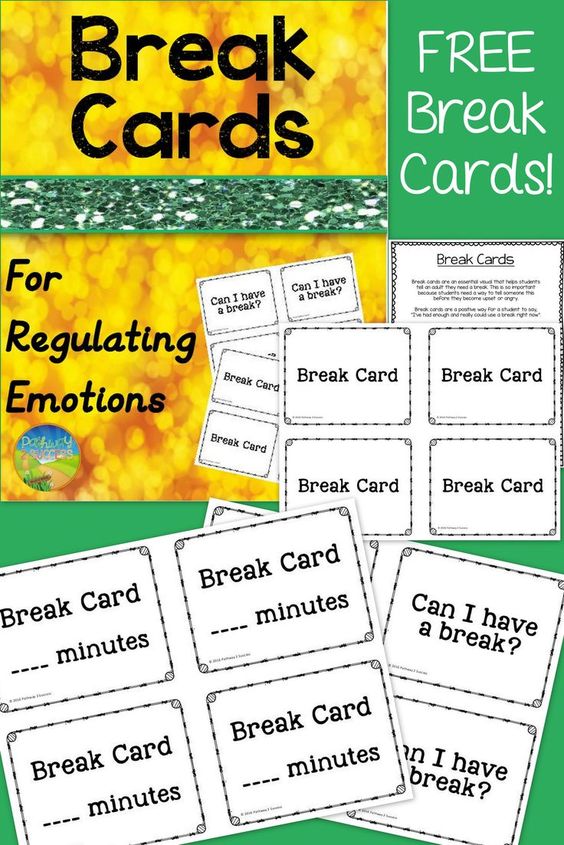

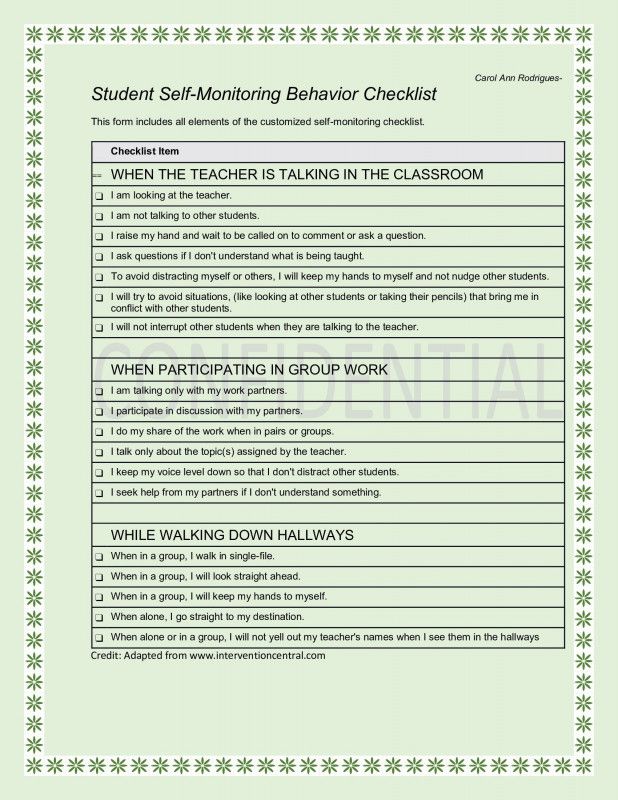

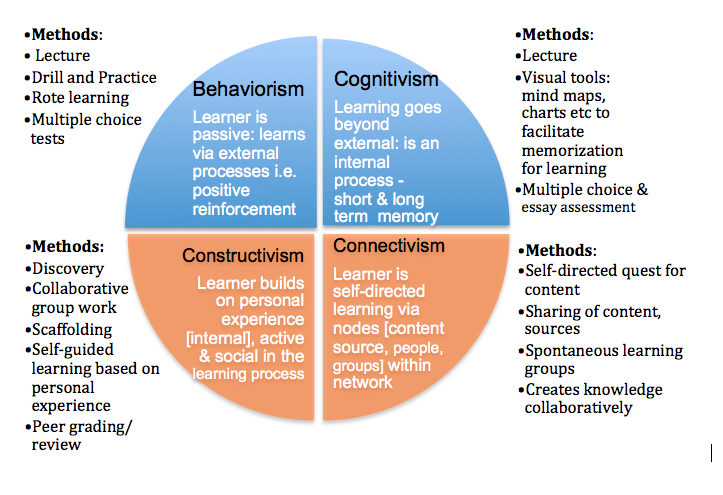

Self-management strategiesSelf-management is one of the effective school-based intervention strategies used to help ADHD children develop appropriate self-control levels. It is expected that this strategy will be able to equip ADHD children with age-appropriate behaviors, both socially and academically. DuPaul and Stoner (2003) discuss two approaches associated with self-management strategies. They are self-monitoring and self-reinforcement. Many children diagnosed with ADHD are capable of performing desired behaviors; however, they cannot perform stably for a certain period of time because of personal issues with self-control (Brock et al., 2010). DuPaul and Stoner (2003, p. 166) claim that ADHD children “can be taught to observe and record the occurrence of their own behaviors†during academic work. For example, teachers can use auditory or visual stimuli periodically throughout a certain period of time to remind the children to observe their current behavior. Then children can be asked to record their instances of on-task behavior using a grid or chart. With regard to self-reinforcement, it requires that children set their goals, self-assess, and evaluate their own performance. This approach may be appropriate for ADHD children at the secondary level (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003). For example, token reinforcement programs and teachers’ feedback are often used for the self-reinforcement.

They are self-monitoring and self-reinforcement. Many children diagnosed with ADHD are capable of performing desired behaviors; however, they cannot perform stably for a certain period of time because of personal issues with self-control (Brock et al., 2010). DuPaul and Stoner (2003, p. 166) claim that ADHD children “can be taught to observe and record the occurrence of their own behaviors†during academic work. For example, teachers can use auditory or visual stimuli periodically throughout a certain period of time to remind the children to observe their current behavior. Then children can be asked to record their instances of on-task behavior using a grid or chart. With regard to self-reinforcement, it requires that children set their goals, self-assess, and evaluate their own performance. This approach may be appropriate for ADHD children at the secondary level (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003). For example, token reinforcement programs and teachers’ feedback are often used for the self-reinforcement. However, designers of the self-management strategies must be aware that ADHD children may lack the skill to judge and evaluate their own behavior; hence, they need to know how to use the system and be aware of the behaviors expected of them (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003).

However, designers of the self-management strategies must be aware that ADHD children may lack the skill to judge and evaluate their own behavior; hence, they need to know how to use the system and be aware of the behaviors expected of them (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003).

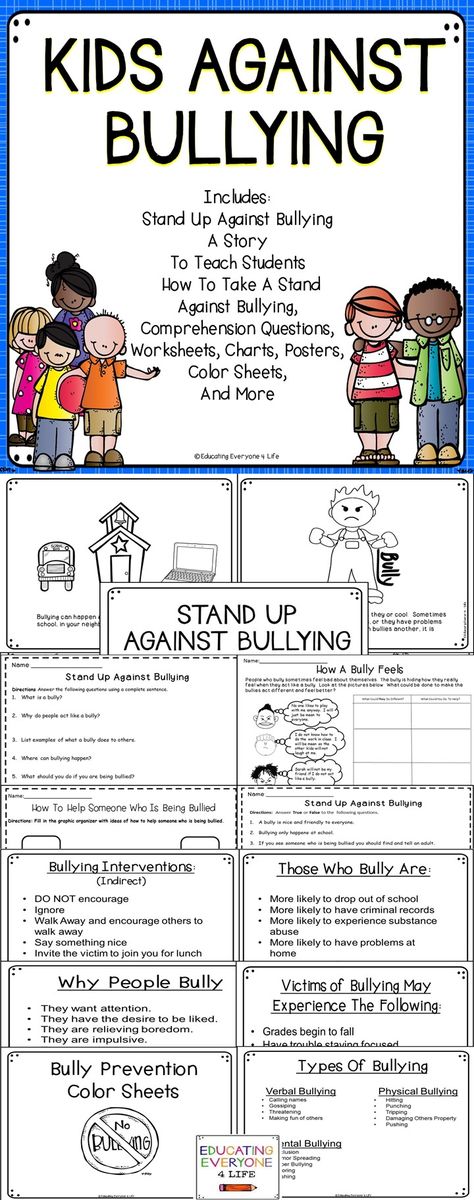

Children with ADHD will learn best when clear classroom expectations are fully communicated (Henderson, 2008). For better management of behaviors, the teaching of classroom rules and expectations is imperative. Because ADHD children can quickly become disruptive, teachers must keep reminding them about the rules and expectations so that they can stay on the right track and get engaged in the classroom. For example, teachers can (1) prompt students of expected behaviors before commencing classroom activities, (2) assure that every academic and nonacademic activity and classroom routine are clearly communicated with and understood by students, (3) use nonverbal signals to redirect a student while working with other students, and (4) regularly communicate their expectations about the use of time blocks (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003).

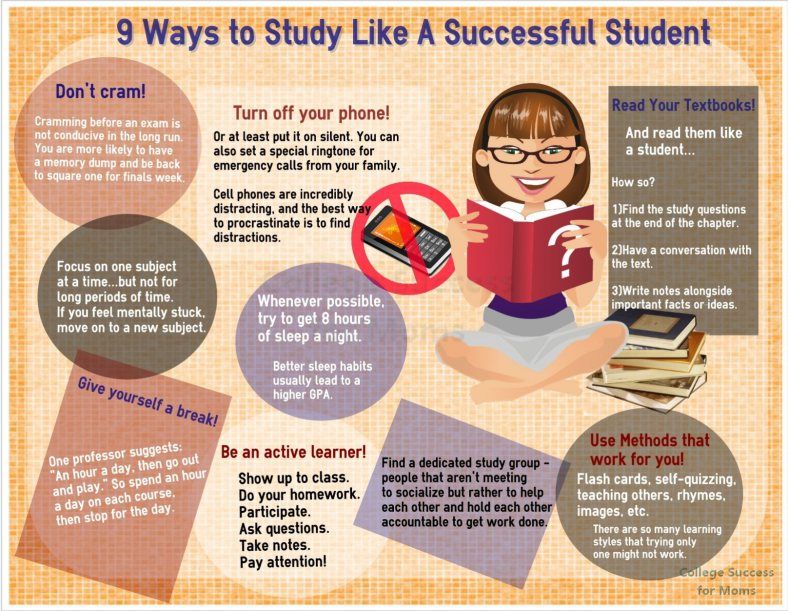

Several studies reported that ADHD children usually experience difficulties in fulfilling tasks, organizing learning materials, following instructions, and studying for exams (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003). Therefore, teaching them study and organizational skills will benefit them. Henderson (2008) recommends some necessary study skills for ADHD children to be taught. They include using Venn diagrams to demonstrate and arrange main concepts or information, taking notes of key concepts, creating an academic checklist for frequently made mistakes and homework supplies, and so on. For organizational skills, Henderson (2008) suggests that teachers teach the children to use assignment notebooks to organize schoolwork and homework and use color-coded folders for different academic subjects and other purposes. Even though many strategies have been suggested and proved to be effective, teachers should select appropriate strategies that are workable in their own classroom contexts.

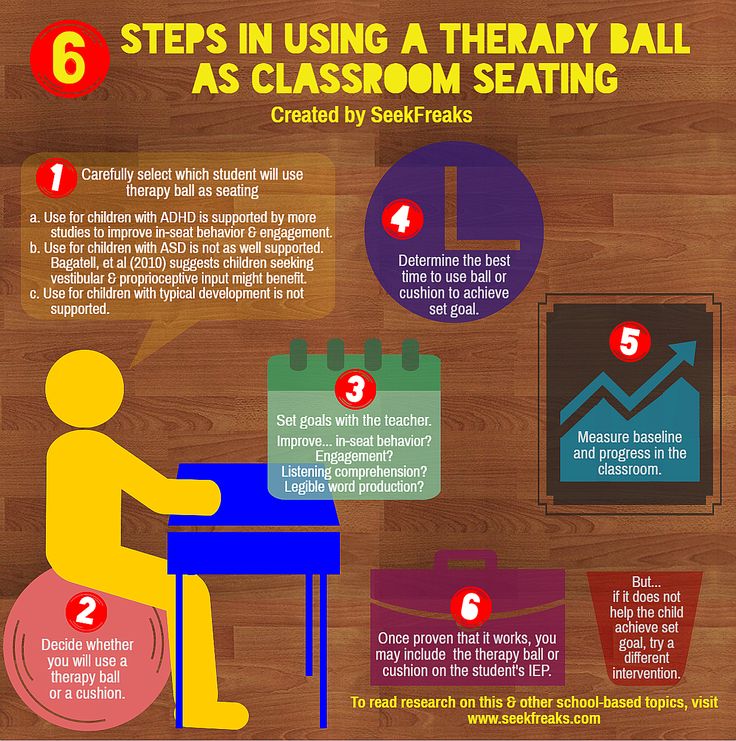

Peer tutoring is one of the most effective school-based intervention strategies to assist ADHD children and even children without this disorder with their academic progress. Peer tutoring is a flexible, peer-mediated strategy that involves students serving as academic tutors and tutees (Hott et al., 2012). Peer tutoring allows ADHD children to receive necessary one-to-one assistance, gain more opportunities to respond in small groups, obtain more time to engage in tasks, and develop personal self-esteem. Peer tutoring will be most effective when participating children are guided appropriately (Greenwood & Delquadri, 1995; Piffner, 2011).

Computer-assisted instructionComputer-assisted instruction (CAI) is an intervention strategy that is believed to be useful for teaching ADHD children. CAI involves the use of computer programs or software to support classroom instruction. CAI has been used to develop students’ knowledge and skills and enhance their academic performance (Miller, 2002). Alontaga et al. (2012) advocate that CAI provides ADHD children with a highly stimulating instructional environment where children gain immediate feedback on their performance, reinforcement, and ongoing opportunities to respond to academic stimuli. A study that investigated the effects of using math software called “Math Blaster†with three primary male students identified with ADHD indicated some significant decreases in off-task behaviors because the three students appeared to engage more with the software (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003).

Alontaga et al. (2012) advocate that CAI provides ADHD children with a highly stimulating instructional environment where children gain immediate feedback on their performance, reinforcement, and ongoing opportunities to respond to academic stimuli. A study that investigated the effects of using math software called “Math Blaster†with three primary male students identified with ADHD indicated some significant decreases in off-task behaviors because the three students appeared to engage more with the software (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003).

Task modification (TM) is used to enhance the academic performance of children identified with ADHD. TM involves reviewing aspects of learning (curriculum) to lessen inappropriate behaviors and increase proper classroom behaviors. However, Meyer and Evans (1989) argue that TM responds more positively only to the personal needs of individual students. Choice-making is one form of TM. It requires students to select activities from two or more choices. Studies investigating the effects of choice-making on students with developmental disabilities have shown rises in social behaviors and reductions in excessively active behaviors (Dyer et al., 1990; Koegel et al., 1987 as cited in DuPaul & Stoner, 2003). Another study conducted by Dunlap et al. (1994) examined the effects of choice-making on three students; one of them was a 12-year-old male ADHD student. The outcomes indicated that choice-making led to increased trustworthy task engagement and decreased overactive behaviors.

Studies investigating the effects of choice-making on students with developmental disabilities have shown rises in social behaviors and reductions in excessively active behaviors (Dyer et al., 1990; Koegel et al., 1987 as cited in DuPaul & Stoner, 2003). Another study conducted by Dunlap et al. (1994) examined the effects of choice-making on three students; one of them was a 12-year-old male ADHD student. The outcomes indicated that choice-making led to increased trustworthy task engagement and decreased overactive behaviors.

Instructional modification (IM) is a necessary intervention strategy for teaching ADHD children. Modifications in instruction can be carried out to improve the academic environment, especially for children with ADHD. A study conducted by Skinner and his colleagues (1995), as cited in DuPaul & Stoner (2003), examined the effects of two taped-words, fast-taped words (FTW) and slow-taped words (STW) intervention on word-reading performance based on accuracy rates. The study results indicated that there were relatively greater accuracy rates in STW intervention, suggesting that this intervention strategy be effective in promoting reading accuracy rate for ADHD students.

The study results indicated that there were relatively greater accuracy rates in STW intervention, suggesting that this intervention strategy be effective in promoting reading accuracy rate for ADHD students.

Strategy training involves teaching students to use a particular set of strategies to complete academic work in demanding academic situations (DuPaul & Stoner 2003). This strategy seems suitable for adolescents with ADHD, as they are likely to present poor organizational and study skills. For example, students with ADHD may face difficulties in note-taking for future review. Spires & Stone (1989) developed a note-taking strategy widely known as Directed Note-taking Activity. Students can learn this note-taking skill through teacher-directed presentation/speech and prompts. It is believed that this note-taking strategy can level up on-task behaviors and academic performance of ADHD adolescents.

Contingency contractingContingency contracting, sometimes known as classroom behavior agreement, is another school-based strategy for behavior management. It involves negotiating a contractual behavior agreement between a student and a teacher. Agreed behaviors are typically set along with positive and negative consequences when the desired behaviors are met and not met, respectively. However, this strategy is relatively straightforward and might not be suitable for ADHD children aged under six due to some factors such as inadequate rule-following skills and an inability to delay reinforcement for a longer time (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003).

It involves negotiating a contractual behavior agreement between a student and a teacher. Agreed behaviors are typically set along with positive and negative consequences when the desired behaviors are met and not met, respectively. However, this strategy is relatively straightforward and might not be suitable for ADHD children aged under six due to some factors such as inadequate rule-following skills and an inability to delay reinforcement for a longer time (DuPaul & Stoner, 2003).

Conclusion

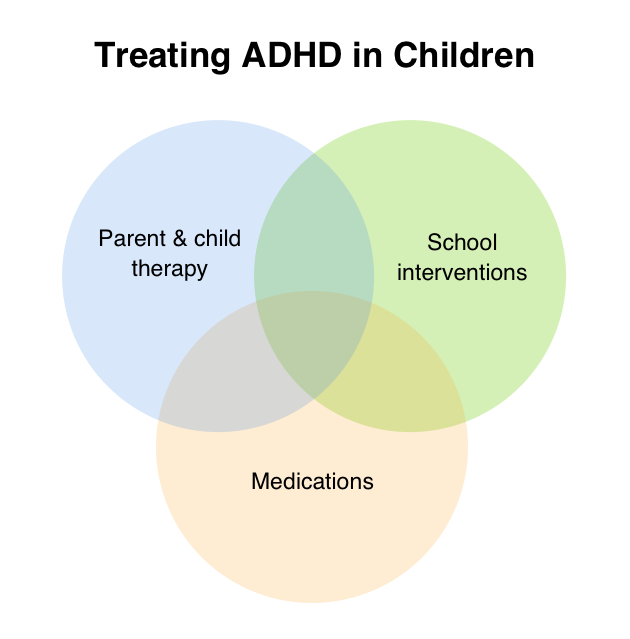

Children diagnosed with ADHD face plenty of difficulties in their classroom behavior and academic performance, resulting in low academic achievement, complicated social interactions, and other behavior-related consequences. Regardless of any disorder labeling, each child has different needs and learning styles; they respond differently to different strategies and learning environments. Therefore, well-established school-based intervention strategies, including behavioral and instructional strategies, are required to ensure that every ADHD child’s chances for academic success are maximized. It is crucial that all stakeholders, including schools, parents, and the community, work together to support ADHD children in their pursuit of academic and social success. Moreover, other interventions, such as medical interventions, behavior-related therapy, good parenting program, etc., should be used along with school-based interventions.

It is crucial that all stakeholders, including schools, parents, and the community, work together to support ADHD children in their pursuit of academic and social success. Moreover, other interventions, such as medical interventions, behavior-related therapy, good parenting program, etc., should be used along with school-based interventions.

The Author

SOL Koemhong is currently a Japanese Government (MEXT) scholar pursuing a Doctor of Philosophy in Education at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of the International Christian University in Tokyo, Japan. He is also an Associate Editor for the Cambodian Education Forum. In 2016, he was awarded a Chevening scholarship to undertake his Master of Arts in Education Management and Leadership at the University of South Wales in the United Kingdom. Prior to leaving for Japan, he was a lecturer at the Faculty of Education of the PaññÄsÄstra University of Cambodia. His research interests center on teacher education and policy, continuous professional development (CPD) for EFL teachers, school leadership, special education, and learning and teaching assessment.

References

Alontaga, J. V. Q., Lim, E., Balaji, S., Murugaiyan, M.S., Holly Deviarti, S. E., Heny Kurniawati, S.E., Yen Sun, S.E., & Heri Sukendar, W.D. (2012). A computer-assisted instruction module on enhancing numeracy skills of preschoolers with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, International Journal of Information Technology and Business Management, 2(1), 1-15.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Virginia: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Brock, S.E., Glove, B., & Searls, M. (2010). ADHD: Classroom interventions. Maryland: National Association of School Psychologists.

Dunlap, G., DePerczel, M., Clarke, S., Wilson, D., Wright, S., White, R., & Gomez, A. (1994). Choice making to promote adaptive behavior for students with emotional and behavioral challenges, Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(3), 505-518.

DuPaul, G. J., & Stoner, G. (2003). ADHD in the schools: Assessment and intervention strategies (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Publications.

J., & Stoner, G. (2003). ADHD in the schools: Assessment and intervention strategies (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Publications.

Fox, G. (2001). Supporting children with behaviour difficulties: A guide for assistants in schools. London: David Fulton Publishers.

Greenwood, C. R., & Delquardri, J. (1995). Classwide peer tutoring and the prevention of school failure, Preventing School Failure, 39(4), 21-25.

Henderson, K. (2008). Teaching children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Instructional strategies and practices. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Office of Special Education.

Hott, B., Walker, J., & Sahni, J. (2012). Peer tutoring. Retrieved from http://council-for-learning-disabilities.org/peer-tutoring-flexible-peer-mediated-strategy-that-involves-students-serving-as-academic-tutors

Meyer, L. H., & Evans, I. M. (1989). Nonaversive intervention for behavior problems: A manual for home and community. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

M. (1989). Nonaversive intervention for behavior problems: A manual for home and community. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Meyer, H., & Lasky, S. (2017) School-based management of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: 105 tips for teachers. Retrieved from https://www.addrc.org/disorder-105-tips-for-teachers/

Miller, S. P. (2002). Validated practices for teaching students with diverse needs and abilities. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

National Health Service. (2018). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Retrieved from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/

Piffner, L. J. (2011). All about ADHD: The complete practical guide for classroom teachers (2nd ed.). New York: Scholastic.

Spires, H. A., & Stone, P. D. (1989). The directed note-taking activity: A self-questioning approach, Journal of Reading, 33(1), 36-39.

Wehmeier, P. M. , Schacht, A., & Barkley, R. A. (2010). Social and emotional impairment in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact on quality of life, Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(3), 209-217.

, Schacht, A., & Barkley, R. A. (2010). Social and emotional impairment in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact on quality of life, Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(3), 209-217.

Appendix: Diagnostic Criteria for ADHD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, pp. 59-60)

People with ADHD show a persistent pattern of inattention and/ or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development:

A. Inattention: Six or more symptoms of inattention for children up to age 16, or five or more for adolescents 17 and older and adults; symptoms of inattention have been present for at least 6 months, and they are inappropriate for developmental level:

- Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or with other activities

- Often has trouble holding attention on tasks or play activities

- Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly

- Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (e.

g., loses focus, side-tracked)

g., loses focus, side-tracked) - Often has trouble organizing tasks and activities

- Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to do tasks that require mental effort over a long period of time (such as schoolwork or homework)

- Often loses things necessary for tasks and activities (e.g., school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones)

- Is often easily distracted

- Is often forgetful in daily activities

B. Hyperactivity and Impulsivity: Six or more symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity for children up to age 16, or five or more for adolescents 17 and older and adults; symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity have been present for at least 6 months to an extent that is disruptive and inappropriate for the person’s developmental level:

- Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat

- Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected

- Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is not appropriate (adolescents or adults may be limited to feeling restless)

- Often unable to play or take part in leisure activities quietly

- Is often “on the go†acting as if “driven by a motorâ€

- Often talks excessively

- Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed

- Often has trouble waiting his/her turn

- Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.

g., butts into conversations or games)

g., butts into conversations or games)

In addition, the following conditions must be met:

- Several inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were present before age 12 years

- Several symptoms are present in two or more setting, (such as at home, school or work; with friends or relatives; in other activities)

- There is clear evidence that the symptoms interfere with, or reduce the quality of, social, school, or work functioning

- The symptoms are not better explained by another mental disorder (such as a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder). The symptoms do not happen only during the course of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder.

| Cambodian Education Forum (CEF) CEF accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility rests solely with the individual authors. |

Published by CambodianEducationForum

CEF aims to provide a platform for Cambodian researchers, educators, teachers, students and administrators, especially novice and emerging writers, to express their views and share their perspectives and understanding on topics relevant to education in Cambodia and beyond.

What is Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

What is Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder - Timmi.clubSkip to content

Distinguishing between a child's restlessness and Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder requires an understanding of the underlying causes of ADHD and its symptoms. When identifying a neurological-behavioral disorder, it is important to seek the help of specialists as soon as possible, who will diagnose the child's health status and develop effective corrective measures. The TimmiClub Children's Center team supports parents for the harmonious development of children with ADHD. nine0003

What is ADHD in children?

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is a disease associated with a neurological disorder. The phenomenon is quite common: approximately 10% of schoolchildren aged 11–12 years have signs of ADHD. The deviation is more common in children, and its persistence in adulthood is quite high: 80% of all cases. ADHD is difficult to prevent or treat completely, but early detection and a behavioral intervention plan with a professional can help the child and adult manage the disorder. nine0003

ADHD is difficult to prevent or treat completely, but early detection and a behavioral intervention plan with a professional can help the child and adult manage the disorder. nine0003

Causes of ADHD

The exact source that stimulates the development of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder has not been identified by medical experts. But on the basis of the collected statistics, the most common prerequisites were identified:

- Heredity, which contributes to the transmission of the gene.

- Injury or features of the brain responsible for activity.

- Chemicals and toxins that alter brain activity.

- Maternal malnutrition, infections and smoking during pregnancy. nine0016

Contrary to myths, a lot of TV watching, food allergies or school problems do not cause ADHD in a child.

Sensory integration classesTypes of ADHD and their signs

Pronounced features of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder appear before the age of 12, and in some children are noticeable as early as 3 years. Symptoms are of the following severity:

Symptoms are of the following severity:

- mild;

- moderate;

- heavy. nine0016

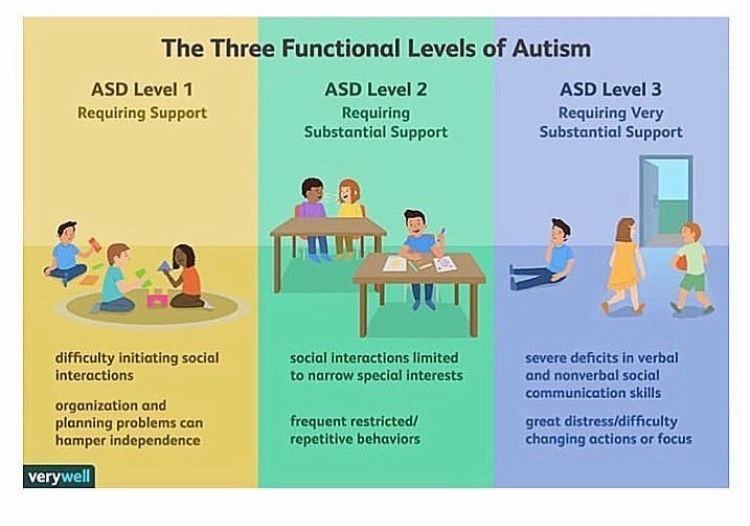

Three subtypes of ADHD have been identified, characterized by certain behavioral features.

To determine the real level of a child's development, experts recommend neuropsychological diagnostics. Read more about this in the article.

Inattentive

In this group, symptoms are associated with inattention. The child often demonstrates:

- constant distraction;

- failure to follow instructions and requests; nine0016

- forgetfulness in daily activities;

- problems with self-organization;

- dislike of sitting still;

- frequent loss of school subjects;

- tendency to daydream during lessons.

Hyperactive and impulsive

Children with this type of syndrome are characterized by:

Combined

In practice, there is a combined attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Among its symptoms, signs of types I and II are diagnosed. A child with this type of ADHD is the most restless and mobile. Identifying the first symptoms is not difficult, and behavior modification requires more effort. TimmiClub specialists work with children in need of additional development and develop a program for parents to communicate and work with the child. nine0003

Among its symptoms, signs of types I and II are diagnosed. A child with this type of ADHD is the most restless and mobile. Identifying the first symptoms is not difficult, and behavior modification requires more effort. TimmiClub specialists work with children in need of additional development and develop a program for parents to communicate and work with the child. nine0003

Symptoms in adults

If the disorder is diagnosed in childhood, some symptoms may change with age. An adult with ADHD is characterized by a number of symptoms:

- frequent lateness to work and forgetfulness;

- alarm;

- low self-esteem;

- anger control problems;

- impulsiveness;

- procrastination;

- quick disappointment;

- boredom and mild depression;

- poor concentration when reading;

- mood swings;

- difficulties in building relationships;

- substance abuse;

- different kinds of dependencies.

Diagnosis of ADHD

If suspicion arises, parents turn to a pediatrician who redirects them to a child's examination by a pediatric neuropathologist or psychiatrist. As necessary, the development specialist conducts diagnostics in conjunction with other physicians. At this stage, the presence of ADHD in a child, the possible causes of its occurrence and the severity of the disorder are clarified. As a result, a program of classes and methods for correcting behavior is developed. nine0003 A boy sorts glass marbles by color

A child's ADHD treatment program

A comprehensive examination aimed at identifying certain attention disorders allows you to understand what exactly the child finds difficult to focus on. Based on the definition of a distraction, an individual treatment program is developed. It consists of several blocks:

- Drug treatment. As drugs, stimulants of the areas of the brain responsible for concentration are more often used.

The task of the specialist is to correctly select the appropriate medication and its dosage. nine0016

The task of the specialist is to correctly select the appropriate medication and its dosage. nine0016 - Behavioral therapy. Classes with the child of a specialist and reinforcement of positive behavior. For example, he is praised for focusing on the material for longer than the previous meeting. A relaxing approach is effective and indispensable in combination with drug treatment.

- Family consultation. A child suffering from Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is often naughty and aggressive. This complicates family relationships. The specialist communicates with parents, answers their questions and teaches how to properly respond to the active manifestation of symptoms in order to avoid aggravating the disorder. nine0118

One of the most important activities for children with ADHD is adaptive physical education (APC). In this article, you will learn all the details about AFK and what benefits it brings.

Complications

Untimely detection of signs of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and irresponsible attitude to the disease will seriously complicate the life of the child, including with age. Common problems include:

Common problems include:

- restlessness in the classroom, leading to regular academic failure and condemnation from other children, their parents and teachers; nine0016

- tendency to frequent injuries of various kinds and accidents;

- high chances of future interaction problems, including those with the opposite sex;

- susceptibility to alcohol and drug addiction and delinquency.

To reduce the risk of your baby developing Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, it is recommended to avoid anything that could harm the fetus early in pregnancy. After birth, protection from negative influences is also required. nine0003

If you have symptoms of a disorder, contact the TimmiClub Children's Center, our professional team will diagnose and help you create a behavioral adjustment program according to your individual situation.

Request a consultation with a child psychologist

Please note: this content requires JavaScript.

Close menu

Request a call back

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content. nine0003

Find the right professional

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book a 50% discount consultation and trial

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Subscribe for 10 months. Natural sorbent Flumvita Constanta. Net weight per package is 100g.

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Share your experience with TimmiClub

Required field

Name

Phone

Star Rating

Title The title for your review.

Review

Book a TimmiClub Specialist

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book an appointment with a speech pathologist

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book a consultation with a child psychologist

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book a Sensory Integration Consultation and Trial

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book a consultation with a TimmiClub specialist

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Ask your question

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Subscribe for 3 months. Natural sorbent Flumvita Constanta. Net weight per package is 100g.

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Subscribe for 7 months.

Natural sorbent Flumvita Constanta. Net weight per package is 100g.

Natural sorbent Flumvita Constanta. Net weight per package is 100g. Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book an appointment with a neuropsychologist

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content. nine0003

Book an art therapy consultation and trial

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Sign up for neuropsychological comprehensive testing

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Sign up for an exercise therapy trial

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Sign up for a consultation and a trial lesson with a 50% discount

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book an appointment with a physical rehabilitation specialist

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book a TimmiClub Specialist

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book a speech/tube massage

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Sign up for speech therapy taping

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book an ABA Therapy Consultation and Trial

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Please select required facsimile

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book an appointment with a TimmiClub specialist

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Make a return call

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book an ABA Therapy Consultation and Trial

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Sign up for a speech therapy session

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book a speech/probe massage

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content. nine0003

Sign up before fahivtsya TimmiClub

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book an appointment with a physical rehabilitation specialist

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Sign up for a trial lesson in exercise therapy

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Sign up for a comprehensive test by a neuropsychologist

Please note: This content requires JavaScript.

Book a consultation and art therapy trial

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book an appointment with a neuropsychologist

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Submit your loan to TimmiClub

Required field

Name

Phone

Star rating

Title The title for your review.

Review

Enquire

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book a consultation before facilitation TimmiClub

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book a consultation and sensory integration trial

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book a consultation with a child psychologist

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Book an appointment with a speech pathologist

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Choose the right professional

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

Sign up before fahivtsya TimmiClub

Please note: JavaScript is required for this content.

TV and computer significantly dull attention

Video game and TV overindulgence can double attention problems in children and young people

Video game and TV overindulgence can double attention problems in children and young people, scientists say.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children should not spend more than 2 hours a day in front of the TV or computer.

A study by researchers at the University of Iowa found that school and university students are much more likely to have learning problems when screen time is exceeded, writes HealthDay. nine0003

nine0003

A team of specialists conducted a comparative analysis of more than 1300 students in grades 3-5, as well as 210 students. The subjects were divided into 2 groups - those who spent at the screen up to 2 hours a day, and those who spent more time on games and watching TV. It turned out that only 3 hours a day, spent at the monitor, reduce attention to 2.2 times compared to the norm. Moreover, on average, such violations are less pronounced among schoolchildren than among university students.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is a neurological-behavioral disorder that begins in childhood and is characterized by symptoms such as difficulty concentrating, poorly controlled impulsivity and hyperactivity. Both the syndrome itself and its treatment cause controversy among physicians and educators, starting from 1970s. Some believe that ADHD does not exist at all, others believe that there are genetic and physiological causes of this condition. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is now 10 times more common than it was 20 years ago, according to doctors.

"While it is clear that the syndrome has a genetic basis, given that our genes have not changed much over this time, there are probably environmental factors that contribute to this growth. And we must find a way to manage them accordingly way", - said professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Dr. Dmitry Christakis.

His own research has shown that watching TV shows and playing computer games increase the risk of attention problems. "Why? You have to admit that real life doesn't change at the same pace as computer or television reality. Not fast enough to keep the attention of a child," explained Dr. Christakis.

In addition, he noted that there is a difference between what a child watches or what computer games they play. For example, shooter games differ significantly from quests in their effect on the psyche. nine0003

ADHD is generally considered a major handicap, and the inattention it causes leads to family and professional problems.