Insomnia in bipolar

Bipolar Disorder: Sleep Problems and Treatments

Written by Annie Stuart

In this Article

- How Bipolar Disorder Affects Sleep: Get Better Sleep With Bipolar Disorder

- How Bipolar Disorder Affects Sleep

- Get Better Sleep With Bipolar Disorder

How Bipolar Disorder Affects Sleep: Get Better Sleep With Bipolar Disorder

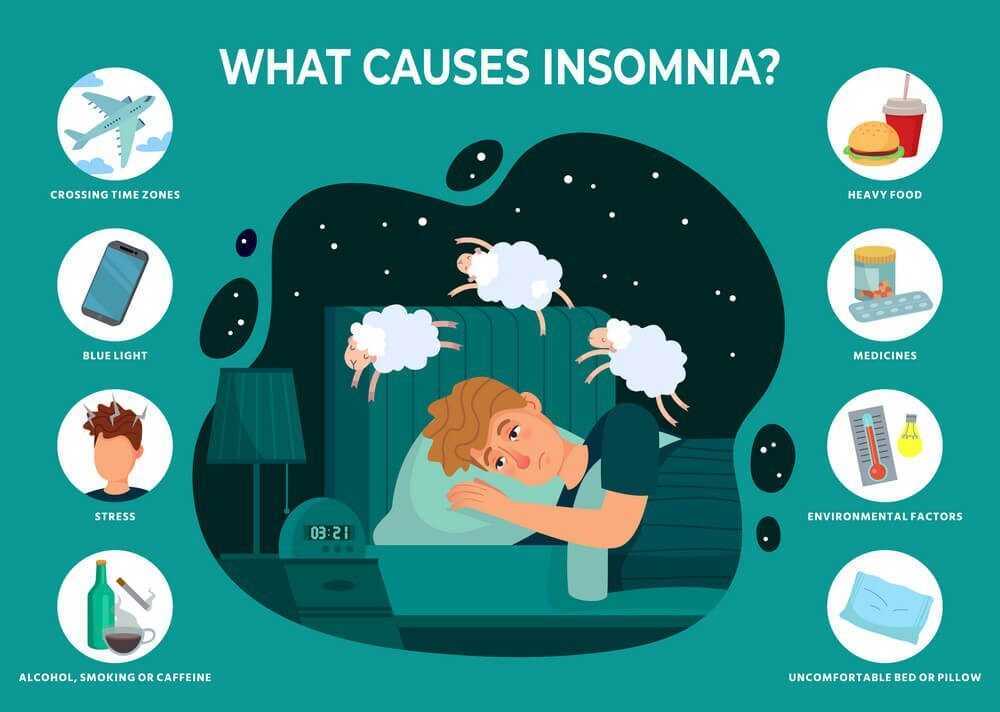

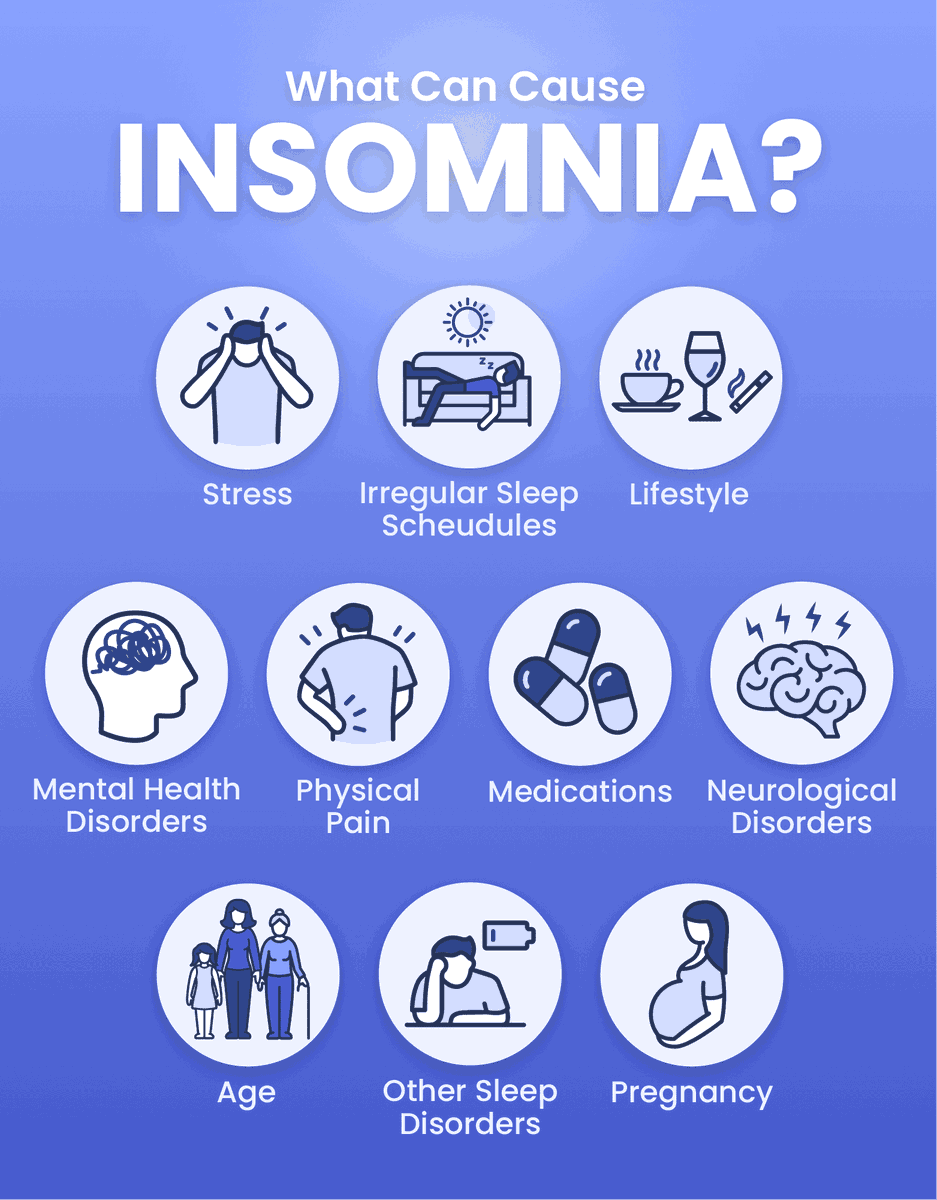

Changes in sleep that last for more than two weeks or interfere with your life can point to an underlying condition. Of course, many things may contribute to sleep problems. Here's what you need to know about the many connections between bipolar disorder and sleep and what you can do to improve your sleep.

How Bipolar Disorder Affects Sleep

Bipolar disorder may affect sleep in many ways. For example, it can lead to:

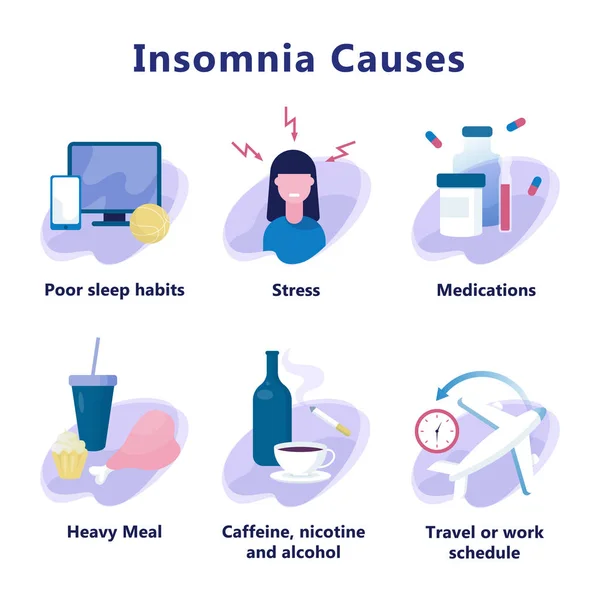

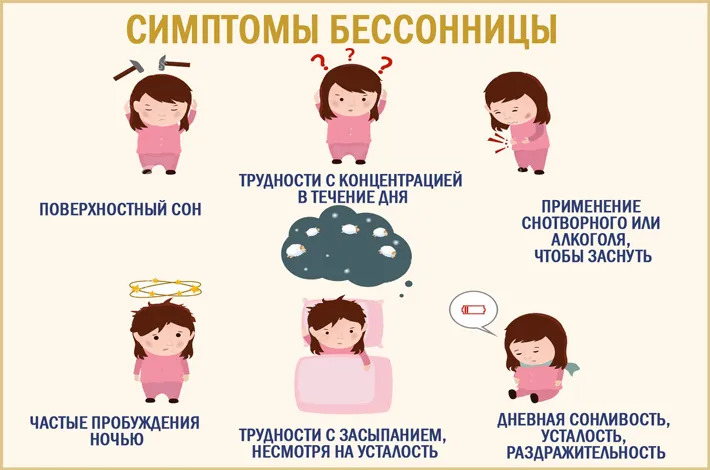

- Insomnia, the inability to fall asleep or remain asleep long enough to feel rested (resulting in feeling tired the next day).

- Hypersomnia, or over-sleeping, which is sometimes even more common than insomnia during periods of depression in bipolar disorder.

- Decreased need for sleep, in which (unlike insomnia) someone can get by with little or no sleep and not feel tired as a result the next day.

- Delayed sleep phase syndrome, a circadian-rhythm sleep disorder resulting in insomnia and daytime sleepiness.

- REM (rapid eye movement) sleep abnormalities, which may make dreams very vivid or bizarre.

- Irregular sleep-wake schedules, which sometimes result from a lifestyle that involves excessive activity at night.

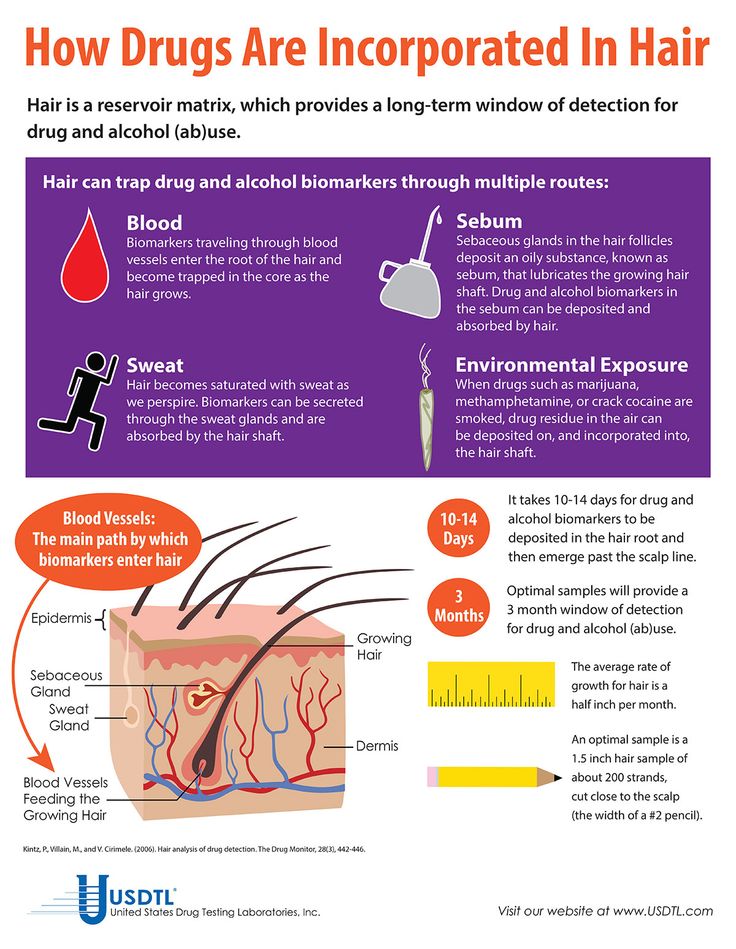

- Co-occurring drug addictions, which may disrupt sleep and intensify pre-existing symptoms of bipolar disorder.

- Co-occurring sleep apnea, which may affect up to a third of people with bipolar disorder, which can cause excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue.

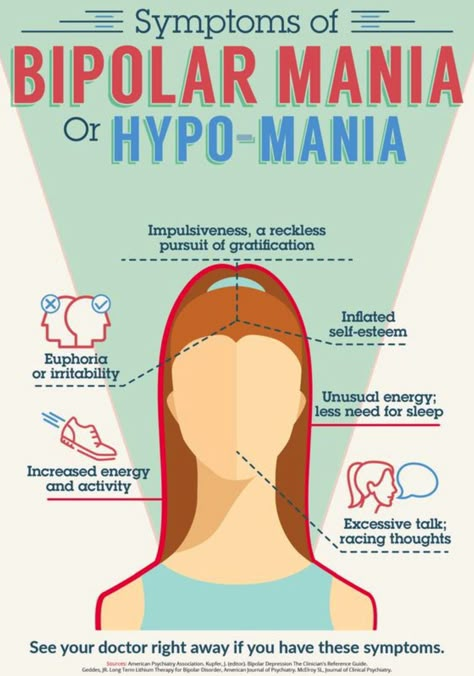

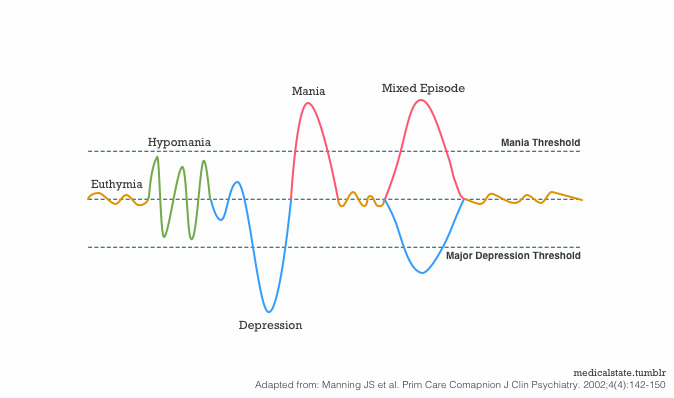

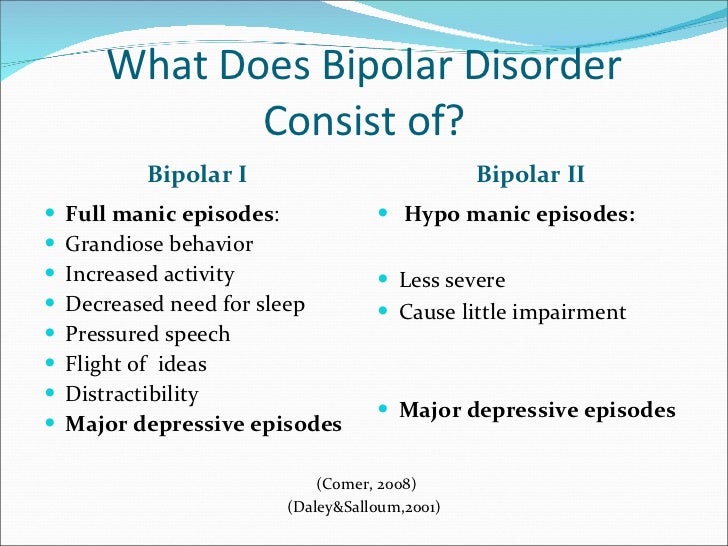

During the highs of bipolar disorder (periods of mania), you may be so aroused that you can go for days without sleep without feeling tired the next day. For three out of four people with bipolar disorder, sleep problems are the most common signal that a period of mania is about to occur. Sleep deprivation, as well as jet lag, can also trigger manic or hypomanic episodes for some people with bipolar disorder.

Sleep deprivation, as well as jet lag, can also trigger manic or hypomanic episodes for some people with bipolar disorder.

When sleep is in short supply, someone with bipolar disorder may not miss it the way other people would. But even though you seem to get by on so little sleep, lack of sleep can take quite a toll. For example, you may:

- Be extremely moody

- Feel sick, tired, depressed, or worried

- Have trouble concentrating or making decisions

- Be at higher risk for an accidental death

You may already know the ups and downs of how bipolar disorder affects sleep. But even between acute episodes of bipolar disorder, sleep may still be affected. You may have:

- Heightened anxiety

- Worries about not sleeping well

- Sluggishness during the day

- A tendency to have misperceptions about sleep

Get Better Sleep With Bipolar Disorder

Disrupted sleep can really aggravate a mood disorder. A first step may be figuring out all the factors that may be affecting sleep and discussing them with your doctor. Keeping a sleep diary may help. Include information about:

A first step may be figuring out all the factors that may be affecting sleep and discussing them with your doctor. Keeping a sleep diary may help. Include information about:

- How long it takes to go to sleep

- How many times you wake up during the night

- How long you sleep all night

- When you take medication or use caffeine, alcohol, or nicotine

- When you exercise and for how long

Certain bipolar medications may also affect sleep as a side effect. For example, they may disrupt the sleep-wake cycle. One way to address this is to move bedtime and waking time later and later each day until you reach your desired goal. Two other ways to handle this situation are bright light therapy in the morning and use of the hormone melatonin at bedtime, as well as to avoid bright light or over-stimulating activity near bedtime. This can include exercise and TV, phone, and computer screens.

Of course, your doctor may recommend a change in medication if needed. Be sure to discuss any other drugs or medical conditions that may be affecting your sleep, such as arthritis, migraines, or a back injury.

Be sure to discuss any other drugs or medical conditions that may be affecting your sleep, such as arthritis, migraines, or a back injury.

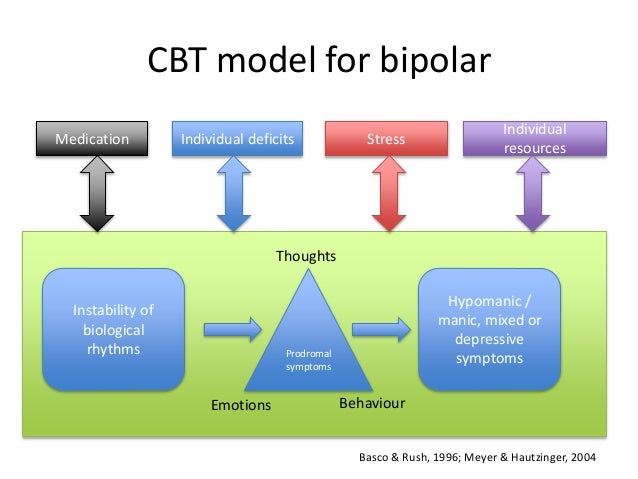

Restoring a regular schedule of daily activities and sleep -- perhaps with the help of cognitive behavioral therapy -- can go a long way toward helping restore more even moods.

Steps like these may also help restore sleep:

- Eliminate alcohol and caffeine late in the day.

- Keep the bedroom as dark and quiet as possible and maintain a temperature that is not too hot or cold. Use fans, heaters, blinds, earplugs, or sleep masks, as needed.

- Talk with your partner about ways to minimize snoring or other sleep habits that may be affecting your sleep.

- Exercise, but not too late in the day.

- Try visualization and other relaxation techniques.

- Try to unplug from the TV, laptop or your phone earlier.

- You may want to try a device that will give you white noise in the background.

- Technologies such as Apollo wearable can also deliver light vibrations to the skin at different frequencies and intensities, which may help improve sleep.

Bipolar Disorder Guide

- Overview

- Symptoms & Types

- Treatment & Prevention

- Living & Support

New Directions for Insomnia and Bipolar Disorder

The average patient with bipolar disorder struggles with sleep disorders. Here's how you can help.

panchanok/AdobeStock

SPECIAL REPORT: COMORBIDITIES

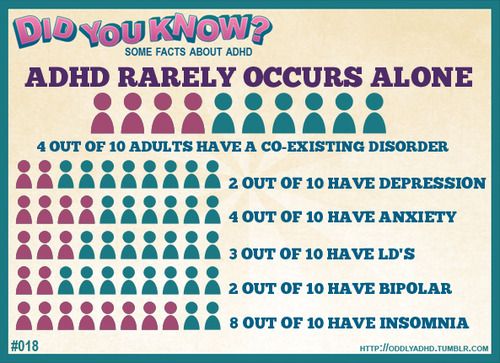

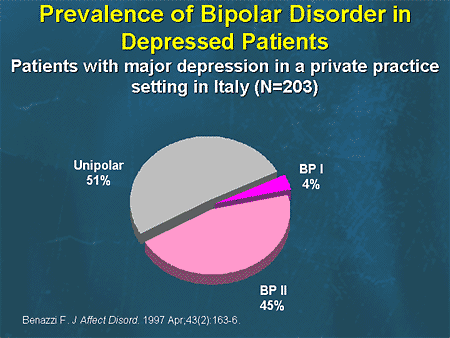

The average patient with bipolar disorder (BD) spends half their life struggling with mood symptoms and the other half struggling with sleep.1,2 Insomnia persists in 70% of patients even when their mood is stable, and these sleep problems put them at risk for more episodes of mania and depression (Table 1).2 Some clinicians are liberal with hypnotics, while others prefer the lower abuse potential of sedating antidepressants like trazodone. Both these approaches have problems. Fortunately, there are also new therapies that improve mood and sleep by entraining the circadian rhythm (Table 2).

Fortunately, there are also new therapies that improve mood and sleep by entraining the circadian rhythm (Table 2).

Table 1. Sleep Problems in BD27

Benzodiazepines and Z-Hypnotics

It seems intuitive that a benzodiazepine or z-hypnotic (eg, eszopiclone, zaleplon, zolpidem) could halt the progression of insomnia into mania, but the idea has never been adequately tested. These GABAergic hypnotics lack controlled trials in BD, and the few observational studies paint a mixed picture. A chart review of 278 z-hypnotic trials in adolescents with BD concluded that the drugs improved sleep in 40% to 60% of patients and did not lead to abuse with long-term use.3 On the other hand, reports document 30 cases of high doses of zolpidem and regular doses of alprazolam and triazolam inducing mania.4-6

Table 2. Potential Treatments

In contrast, clonazepam and lorazepam appear safer, with small controlled trials suggesting that these agents do not worsen, and may improve, manic symptoms (the benzodiazepines were not used as hypnotics in these trials). 7 However, over the long term, benzodiazepines carry risks of tolerance and dependence, and long-term use may worsen cognition and mood in BD, according to nonrandomized studies that attempted to control for the confounding tendency to prescribe benzodiazepines in more severe cases.8,9

7 However, over the long term, benzodiazepines carry risks of tolerance and dependence, and long-term use may worsen cognition and mood in BD, according to nonrandomized studies that attempted to control for the confounding tendency to prescribe benzodiazepines in more severe cases.8,9

Sedating Mood Medications

Another approach to insomnia in BD is to choose mood stabilizers with sedative effects. Many antipsychotics are sedating, but some have more meaningful benefits in sleep quality; these include quetiapine in particular, and possibly lumateperone, olanzapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone.10 Lithium is rarely sedating, but it does have positive effects on the circadian system, such as dampening the phase-advance (“night owl”) tendency that is associated with poorer health and greater risk of depression.11

Sedating antidepressants are more problematic, particularly in bipolar I disorder, in which the risk of manic induction is high. Most, including trazodone and mirtazapine, are associated with case reports of triggering mania. In a retrospective study, patients with BD who used sedating antidepressants for sleep were significantly more likely to develop mania and episode acceleration than those who took traditional hypnotics.12

Most, including trazodone and mirtazapine, are associated with case reports of triggering mania. In a retrospective study, patients with BD who used sedating antidepressants for sleep were significantly more likely to develop mania and episode acceleration than those who took traditional hypnotics.12

Melatonin Agonists

Melatonin agonists have captured the interest of investigators because of their potential to realign the circadian system, which is often disrupted in BD. Pure melatonin failed to improve sleep, mania, or rapid cycling in 2 small controlled trials,13 but the melatonin agonist ramelteon has intriguing results from 3 industry-sponsored, randomized, placebo-controlled trials in BD. Although ramelteon failed to improve sleep or mania, it did prevent depression in patients who struggled with insomnia.

The first study tested ramelteon in 21 patients with acute mania and found a reduction in depressive symptoms but no benefit in mania or sleep. 14 Next, ramelteon was tested in 83 patients with BD who had active insomnia but stable mood. For 6 months, they took either placebo or a nightly dose of ramelteon 8 mg. As in the first trial, ramelteon did little to improve sleep (there was only a nonsignificant trend), but it did lower the risk of depression, more than doubling the time to a new episode from 84 to 188 days (P = .02).15 A larger study attempted to replicate that finding, but the results were negative across all outcomes.16

14 Next, ramelteon was tested in 83 patients with BD who had active insomnia but stable mood. For 6 months, they took either placebo or a nightly dose of ramelteon 8 mg. As in the first trial, ramelteon did little to improve sleep (there was only a nonsignificant trend), but it did lower the risk of depression, more than doubling the time to a new episode from 84 to 188 days (P = .02).15 A larger study attempted to replicate that finding, but the results were negative across all outcomes.16

One explanation for these intriguing results is that the positive trials enrolled patients with active insomnia, while the negative trial did not, suggesting that ramelteon might have preferential effects in patients with disturbed circadian rhythms. But then why didn’t the drug improve their sleep? These studies relied on subjective measures of sleep, and ramelteon has a poor track record on subjective outcomes. In primary insomnia, it improved subjective sleep onset by only 4 minutes over placebo and objective sleep onset by 9 minutes. Benzodiazepines showed the reverse pattern, improving subjective onset by 14 minutes but objective onset by only 4 minutes (placebo, by the way, is no dud, and improved sleep onset by 8 to 20 minutes).17

Benzodiazepines showed the reverse pattern, improving subjective onset by 14 minutes but objective onset by only 4 minutes (placebo, by the way, is no dud, and improved sleep onset by 8 to 20 minutes).17

One thing to take away from this is the importance of setting realistic expectations when starting patients on ramelteon. This hypnotic is not like the others: It is relatively nonsedating and has no anxiolytic, amnestic, or rewarding effects. On the one hand, those qualities improve on its safety, but they are unlikely to endear it to patients with BD, who often want a hypnotic to quiet the anxious, racing thoughts that rev up as they try to fall asleep. Ramelteon will do none of that, but nor will it cause patients to fall, overuse their medication, or engage in complex sleep behaviors like cooking or driving in the middle of the night. One positive aspect that most patients appreciate is the lack of tolerance and withdrawal with ramelteon. Rather than wearing off, ramelteon’s sleep benefits built up over weeks to months in some studies. 18

18

Dark Therapy

While ramelteon is a melatonin agonist, dark therapy is a behavioral treatment that enhances endogenous melatonin by keeping patients in a pitch-dark room overnight. Dark therapy was developed by Thomas Wehr, MD, who speculated that evening darkness might improve sleep and mania in the same way that morning light improves depression and circadian rhythms. In the 1990s, he recruited normal participants with mild sleep problems to the National Institute of Mental Health, where they stayed in a pitch-dark room overnight from 6:00 pm to 8:00 am. After a few weeks of this dark therapy, their sleep improved.19 Next, he turned his attention to BD, and found that the same protocol stabilized refractory rapid cycling.20

Further studies supported Wehr’s observation, but it was not until the discovery of blue light–blocking glasses that dark therapy became practical for everyday use. In theory, the physiologic changes associated with total darkness might be achieved by blocking blue light, because the receptor that regulates melatonin secretion—melanopsin—responds only to the blue spectrum. The hope in that theory is that patients might be able to practice dark therapy while still being able to see in the evening.

The hope in that theory is that patients might be able to practice dark therapy while still being able to see in the evening.

Psychiatrist James Phelps, MD, first tested that hope in private practice, and his results were later confirmed in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Norway. For the entire evening from 6:00 pm to 8:00 am, patients hospitalized with acute mania wore blue light–blocking glasses or, if sleeping or trying to sleep, stayed in a pitch-dark room without the glasses. Within a week, their mania improved with a large effect size (1.86) compared with a placebo group that wore gray glasses.21

The dark therapy protocol can be gradually relaxed after recovery, allowing patients to put the glasses on a few hours before bed to prevent future episodes. That relaxed protocol also improves the sleep, according to 3 randomized controlled trials in primary insomnia. Wearing blue light–blockers 1.5 to 3 hours before bed helped patients fall asleep earlier and stay asleep longer, and improved sleep quality as well as mood and cognition on the following days. 22-24 However, blue light blockers do not have a strong sedative effect. In line with their circadian mechanism, they improve the regularity of sleep more than they improve subjective measures of insomnia.21

22-24 However, blue light blockers do not have a strong sedative effect. In line with their circadian mechanism, they improve the regularity of sleep more than they improve subjective measures of insomnia.21

A critical step in dark therapy is finding glasses that filter close to 100% of blue light. Lenses that were tested in clinical trials include Uvex Skyper S1933X, Uvex Ultra-spec 2000 ($10 to $15) and, for more comfort at a higher price, glasses at lowbluelights.com ($50). More information on the nuts and bolts of dark therapy is available in the Psych Pearls podcasts from August and October 2021.25

CBT-Insomnia

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-i) is thought to work by stabilizing the circadian system, making it a natural fit for mood disorders. In unipolar depression, CBT-i improves mood and sleep, but the therapy is often avoided in BD because it requires patients to limit their time in bed, raising concerns that this sleep deprivation could trigger mania. In 2015, Allison Harvey, PhD, and colleagues at the University of California – Berkeley modified the CBT-i protocol to include a built-in safety valve for BD (CBT-iBD). The newer therapy limits bed restriction to no fewer than 6.5 hours.

In 2015, Allison Harvey, PhD, and colleagues at the University of California – Berkeley modified the CBT-i protocol to include a built-in safety valve for BD (CBT-iBD). The newer therapy limits bed restriction to no fewer than 6.5 hours.

CBT-iBD also includes techniques to address common circadian rhythm abnormalities in BD, such sleep inertia (a prolonged sense of grogginess in the morning) and nocturnal hyperactivity. To counter these sleep-disrupting tendencies, patients develop a wake-up routine encompassing bright light and energizing activity, and an evening wind-down routine in which the lights are dimmed and screen time ceases.

To test the therapy, Harvey recruited 58 patients with stable BD but active insomnia and randomized them to CBT-iBD or a psychoeducational therapy. At the end of the 8-week therapy, patients in the CBT-iBD group were sleeping better compared with controls, but more profound changes came later. After 6 months, those who learned CBT-iBD had an 8-fold reduction in mood problems, spending an average of 3. 3 days in a mood episode vs 25.5 days for controls.2

3 days in a mood episode vs 25.5 days for controls.2

Later, Bryony Sheaves, DClinPsy, BSc, CPsychol, and colleagues adapted CBT-iBD for patients with schizophrenia, major depression, and BD in an inpatient crisis unit. The 2-week program improved sleep and well-being, and it hastened discharge by 8.5 days compared to treatment as usual.26

It can be difficult to find therapists who practice CBT-insomnia, but the core program is available through a prescription app (Somryst) or a free, VA-sponsored app (CBT-i Coach). These programs can be adjusted for BD with the modifications described above.

The Young and Old

Dark therapy and CBT-i are safe in the young and old, and a few tips can help adapt these treatments for different ages. Adolescents often have severe night-owl tendencies, which can be corrected by having the patient wake up 15 to 30 minutes earlier each day and wearing blue light–blockers in the early evening (eg, 5:00 pm to 8:00 pm). Napping is common in older adults but is discouraged in the CBT-i protocol. One compromise is to have the patient eliminate naps during the therapy, and then gradually add them back in once regular sleep is restored. Then they can continue the naps as long as they do not cause a relapse into insomnia. Finally, for patients of all ages who are afraid of the dark, there are nightlights that emit zero blue light (at lowbluelights.com and Amazon).

Napping is common in older adults but is discouraged in the CBT-i protocol. One compromise is to have the patient eliminate naps during the therapy, and then gradually add them back in once regular sleep is restored. Then they can continue the naps as long as they do not cause a relapse into insomnia. Finally, for patients of all ages who are afraid of the dark, there are nightlights that emit zero blue light (at lowbluelights.com and Amazon).

Although no hypnotics are FDA approved in children and adolescents, lithium and several antipsychotics (eg, quetiapine) are approved for them. In the elderly, the risks of falls and cognitive impairment have placed most hypnotics on the “inappropriate” list of the Beers criteria, although ramelteon is well studied in older adults and approved by the Beers.17

The Bottom Line

Treating insomnia in BD is both an art and a science, requiring practitioners to balance the patient’s goal of rapid sedation with the more therapeutic approach of retraining the circadian rhythm. Circadian therapies like ramelteon, dark therapy, and CBT-insomnia have a slow build, but they promise more lasting and substantial benefits for mood and sleep than fast-acting hypnotics.

Circadian therapies like ramelteon, dark therapy, and CBT-insomnia have a slow build, but they promise more lasting and substantial benefits for mood and sleep than fast-acting hypnotics.

Dr Aiken is the Mood Disorders Section Editor for Psychiatric TimesTM, Editor in Chief of The Carlat Psychiatry Report, and director of the Mood Treatment Center. The author does not accept honoraria from pharmaceutical companies but receives royalties from PESI for The Depression and Bipolar Workbook and from W.W. Norton & Co for Bipolar, Not So Much: Understanding Your Mood Swings and Depression.

References

1. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, et al. Long-term symptomatic status of bipolar I vs bipolar II disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6(2):127-137.

2. Harvey AG, Soehner AM, Kaplan KA, et al. Treating insomnia improves mood state, sleep, and functioning in bipolar disorder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(3):564-577.

J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(3):564-577.

3. Schaffer CB, Schaffer LC, Miller AR, et al. Efficacy and safety of nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics for chronic insomnia in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2011;128(3):305-308.

4. Sabe M, Kashef H, Gironi C, Sentissi O. Zolpidem stimulant effect: induced mania case report and systematic review of cases. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;94:109643.

5. Goodman WK, Charney DS. A case of alprazolam, but not lorazepam, inducing manic symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(3):117-118.

6. Singh J, Skrzypcak B, Yasaei R, Mangat N. Triazolam-induced mania in a patient with bipolar I disorder following a dental procedure. Cureus. 2020;12(2):e7119.

7. Curtin F, Schulz P. Clonazepam and lorazepam in acute mania: a Bayesian meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2004;78(3):201-208.

8. Cañada Y, Sabater A, Sierra P, et al. The effect of concomitant benzodiazepine use on neurocognition in stable, long-term patients with bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2021;55(10):1005-1016.

Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2021;55(10):1005-1016.

9. Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Miklowitz DJ, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of recurrence in bipolar disorder: a STEP-BD report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(2):194-200.

10. Monti JM. The effect of second-generation antipsychotic drugs on sleep parameters in patients with unipolar or bipolar disorder. Sleep Med. 2016;23:89-96.

11. Xu N, Shinohara K, Saunders KEA, et al. Effect of lithium on circadian rhythm in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2021;23(5):445-453.

12. Saiz-Ruiz J, Cebollada A, Ibañez A. Sleep disorders in bipolar depression: hypnotics vs sedative antidepressants. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38 Suppl 1:55-60.

13. Quested DJ, Gibson JC, Sharpley AL, et al. Melatonin in acute mania investigation (MIAMI-UK). A randomized controlled trial of add-on melatonin in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2021;23(2):176-185.

14. McElroy SL, Winstanley EL, Martens B, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive ramelteon in ambulatory bipolar I disorder with manic symptoms and sleep disturbance. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(1):48-53.

McElroy SL, Winstanley EL, Martens B, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive ramelteon in ambulatory bipolar I disorder with manic symptoms and sleep disturbance. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(1):48-53.

15. Norris ER, Burke K, Correll JR, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive ramelteon for the treatment of insomnia and mood stability in patients with euthymic bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;144(1-2):141-147.

16. Mahableshwarkar AR, Calabrese JR, Macek TA, et al. Efficacy and safety of sublingual ramelteon as an adjunctive therapy in the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder in adults: a phase 3, randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:275-282.

17. Moore R, Aiken C. Is ramelteon an effective hypnotic? Carlat Psychiatry Report. 2020;18(11-12):1-3.

18. Neubauer DN. A review of ramelteon in the treatment of sleep disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4(1):69-79.

2008;4(1):69-79.

19. Barbato G, Barker C, Bender C, et al. Extended sleep in humans in 14 hour nights (LD 10:14): relationship between REM density and spontaneous awakening. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;90(4):291-297.

20. Wehr TA, Turner EH, Shimada JM, et al. Treatment of rapidly cycling bipolar patient by using extended bed rest and darkness to stabilize the timing and duration of sleep. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43(11):822-828.

21. Henriksen TE, Skrede S, Fasmer OB, et al. Blue-blocking glasses as additive treatment for mania: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(3):221-232.

22. Burkhart K, Phelps JR. Amber lenses to block blue light and improve sleep: a randomized trial. Chronobiol Int. 2009;26(8):1602-1612.

23. Shechter A, Kim EW, St-Onge MP, Westwood AJ. Blocking nocturnal blue light for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;96:196-202.

24. Zimmerman ME, Kim MB, Hale C, et al. Neuropsychological function response to nocturnal blue light blockage in individuals with symptoms of insomnia: a pilot randomized controlled study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2019;25(7):668-677.

Zimmerman ME, Kim MB, Hale C, et al. Neuropsychological function response to nocturnal blue light blockage in individuals with symptoms of insomnia: a pilot randomized controlled study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2019;25(7):668-677.

25. Aiken C, Newsome K. Blue light blockers: a behavior therapy for mania. Psychiatric Times. October 7, 2021. Accessed December 23, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/blue-light-blockers-behavior-therapy-for-mania

26. Janků K, Šmotek M, Fárková E, Kopřivová J. Block the light and sleep well: evening blue light filtration as a part of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Chronobiol Int. 2020;37(2):248-259.

27. Harvey AG, Kaplan, KA, Soehner A. Interventions for sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder. Sleep Med Clin. 2015;10(1):101-105. ❒

Dark night

The causal relationship between lack of sleep and affective disorders is still full of mysteries. But one thing is clear as day: improved sleep can have psychological benefits.

One of the few features of the small, windowless office owned by psychiatrist Murray Raskind is a yellowed photograph of a young man in military uniform. The soldier, sitting on the ground, keeps his balance, leaning on his rifle, and looks into the camera with empty eyes. This is a portrait of a soldier suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from combat. nine0003

Source: Nature

The man in the photo is Don Hall, a participant in the brutal Tet offensive that took place in 1968 in Vietnam. When Raskind met with him in the mid-1990s, Hall was plagued by recurring nightmares replaying his combat experiences as if on videotape, night after night, for nearly 30 years. "It's a hallmark of combat-induced PTSD," says Raskind, director of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Northwest Mental Health Research Center, Educational and Clinical Center in Seattle, Washington - the man who discovered that normalizing blood pressure can relieve nightmares. nine0003

Symptoms of PTSD include: rage and irritability, feeling numb and disconnected from reality, difficulty concentrating. “When it comes to veterans, it turns out that their main problem is the inability to sleep,” says Raskind, “if they have nightmares at night, then the next day they will have a gloomy mood.”

“When it comes to veterans, it turns out that their main problem is the inability to sleep,” says Raskind, “if they have nightmares at night, then the next day they will have a gloomy mood.”

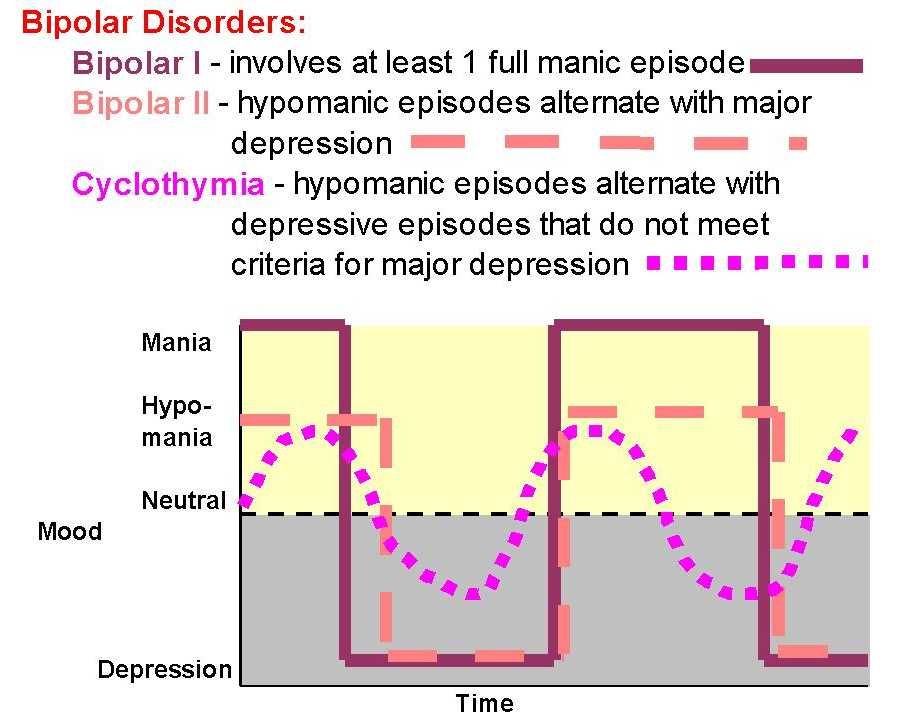

The role of nightmares in PTSD among combatants is particularly significant, but sleep disturbances are also associated with affective and anxiety disorders. Depression is often the cause of insomnia, but sometimes leads to a pathological increase in the duration of sleep or difficulty getting out of bed. During manic episodes, many people with bipolar disorder — a condition in which manic episodes alternate with depressive episodes — seem to need only a small amount of sleep to stay awake all day. nine0003

Sleep disturbance is such a common problem that it is included in the diagnostic criteria for these disorders. "Mood and sleep disorders seem to go hand in hand," says Matthew Walker, a sleep researcher at the University of California, Berkeley.

Distress signals

There is a correlation between insomnia and mental disorder, but the causal relationship is not so clear. Do sleep disturbances trigger these disorders, or do mood and anxiety disorders trigger sleep difficulties? Either one or the other may be right. “It's like a two-way street,” Walker says. It is also likely that some other brain-related problem may be affecting sleep and mood. nine0003

Do sleep disturbances trigger these disorders, or do mood and anxiety disorders trigger sleep difficulties? Either one or the other may be right. “It's like a two-way street,” Walker says. It is also likely that some other brain-related problem may be affecting sleep and mood. nine0003

This allows us to conclude that these two disorders are fundamentally intertwined. For example, people who sleep poorly are more prone to depression than others. Insomnia is often the first symptom of a depressive episode and does not go away until the episode ends. And a treatment regimen that includes antidepressants and psychotherapy is less effective for people who suffer from depression and insomnia than for patients who suffer from depression alone.

Loss of sleep in patients with bipolar affective disorder precedes episodes of mania. From this it follows that sleep is quite strongly associated with depressive episodes. There was a study that found that sleep deprivation causes mania in people with bipolar disorder or, in 10% of patients, hypomania, a less severe episode that often precedes mania. nine0003

nine0003

People with bipolar disorder and other related illnesses will also be night owls, developing a disorder called “delayed sleep-wake syndrome”. Such observations suggest that affective disorders may develop due to sleep disturbances resulting from problems with circadian rhythms.

“Supporting the association with circadian rhythm disturbances is the seasonality of bipolar disorder symptoms that some patients experience,” says Ruf Benka, a psychiatrist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In spring and autumn, when the length of the day changes most rapidly, they are characterized by the maximum manifestations of suicidal behavior. nine0003

“However, despite extremely erratic sleep phases, individual patients with bipolar disorder can have normal circadian rhythms,” says psychologist Ellen Frank of the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Sleep problems associated with affective disorders go beyond just “tossing and turning” in your sleep. Electroencephalogram (EEG) studies have shown deviations not only in how many hours and what time of day these patients sleep, but also in how their brain functions during sleep. Compared with healthy people, patients with bipolar disorder are more likely to develop abnormalities such as long periods of light sleep and frequent awakenings. As a result, they spend less time in deep sleep, known as slow-wave or delta-wave sleep. “It is not known why the brains of these patients are unable to reproduce the delta waves, which we think are associated with the restorative component of sleep,” says Frank. nine0003

Electroencephalogram (EEG) studies have shown deviations not only in how many hours and what time of day these patients sleep, but also in how their brain functions during sleep. Compared with healthy people, patients with bipolar disorder are more likely to develop abnormalities such as long periods of light sleep and frequent awakenings. As a result, they spend less time in deep sleep, known as slow-wave or delta-wave sleep. “It is not known why the brains of these patients are unable to reproduce the delta waves, which we think are associated with the restorative component of sleep,” says Frank. nine0003

In another EEG study, Benka and colleagues found that people with depression do not show the expected pre- and post-sleep changes in brain function associated with non-REM sleep. The brain's electrical response to sound, known as the "auditory evoked potential," is normally higher before sleep than upon awakening, but depressed patients did not show this decrease. “The minds of people with depression don't “reset” between night and morning as they do in the control group,” says Benka. nine0003

nine0003

It's a startling finding, she notes, because the study participants didn't have severe insomnia. However, Benka warns that the disruption may not be related to the day-to-day symptoms that people with affective disorder experience. It is possible that sleep simply eliminates daytime temporalities and distractions and shows how the brain of a person suffering from this disease functions differently in the aggregate.

Images that evoke negative emotions

To unravel this relationship, scientists are examining the neural basis of the connection between sleep and emotional state. In one of the first such studies, Walker and colleagues performed brain scans of healthy adults. Some of them were awake, while others were awake for 35 hours, all of them were shown a series of images ranging from neutral to violent and unpleasant, such as disfigured bodies or children with tumors.

In this study, scientists found that viewing images that evoke negative emotions activates the amygdala, which is responsible for the formation of memory associated with emotional experiences. When non-emotional images were shown, the responses of the two groups were approximately the same, however, the amygdala response to negative emotional images was 60% greater in people with sleep deprivation. nine0003

When non-emotional images were shown, the responses of the two groups were approximately the same, however, the amygdala response to negative emotional images was 60% greater in people with sleep deprivation. nine0003

“When we take a healthy brain and deprive it of sleep, we can see altered brain activity similar to that seen in some mental disorders,” Walker says. Similar hyperactivity in the amygdala has also been seen in mood disorders, and unpublished data from Walker's lab suggests that sleep deprivation may mimic some of the brain processes found in anxiety disorder.

Paradoxical as it may sound, some depressed patients who were deprived of sleep for one night had symptoms of the disease subside the next day. Sleep deprivation is thought to suppress the overactivity of the anterior cingulate cortex, an overactivity that is typical of depression. However, after patients are able to sleep again, the symptoms return, so sleep deprivation is not an effective treatment for depression. This discovery contributed to the emergence of studies looking for the types of sleep involved in this effect. Some facts point to REM sleep (REM). For example, tricyclic antidepressants are thought to work by disrupting PBS. “In some cases, the effectiveness of an antidepressant is related to how well it suppresses FBS,” says Benka. But this is hardly the full picture of what is happening. Benki's group demonstrated that disruption of slow wave production during deep sleep has an antidepressant effect, suggesting that some manipulation of slow wave activity may be effective. Researchers in the Walker lab have suggested a possible mechanism for this effect. They found that when healthy but sleep-deprived people view a series of neutral or positive images, they categorize most of the images as positive, in contrast to sleepy people. They also have increased neuronal activity in the mesolimbic system, which is thought to be responsible for "reward", suggesting that sleep deprivation increases pleasure center activity.

This discovery contributed to the emergence of studies looking for the types of sleep involved in this effect. Some facts point to REM sleep (REM). For example, tricyclic antidepressants are thought to work by disrupting PBS. “In some cases, the effectiveness of an antidepressant is related to how well it suppresses FBS,” says Benka. But this is hardly the full picture of what is happening. Benki's group demonstrated that disruption of slow wave production during deep sleep has an antidepressant effect, suggesting that some manipulation of slow wave activity may be effective. Researchers in the Walker lab have suggested a possible mechanism for this effect. They found that when healthy but sleep-deprived people view a series of neutral or positive images, they categorize most of the images as positive, in contrast to sleepy people. They also have increased neuronal activity in the mesolimbic system, which is thought to be responsible for "reward", suggesting that sleep deprivation increases pleasure center activity. These results are a kind of reference to the violent reaction previously discovered by Walker to images that cause negative emotions in very tired volunteers - sleep deprivation, according to the researchers, increases emotional reactivity in general. nine0003

These results are a kind of reference to the violent reaction previously discovered by Walker to images that cause negative emotions in very tired volunteers - sleep deprivation, according to the researchers, increases emotional reactivity in general. nine0003

Night improvement

The causal relationship between sleep and affectivity is not yet clear, but the value of treatment is to get people to sleep better. “Such sleep disturbances are quite manageable,” says Alison Harvey, a clinical psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley. “Simple but powerful behavioral changes can lead to marked improvements in sleep and anxiety.”

For example, Frank and her colleagues have developed an approach to treating bipolar disorder that encourages patients to adhere to a daily schedule of waking up, eating, socializing, and sleeping. This method, according to Frank, prevents the occurrence of new attacks in bipolar disorder, and also helps people get rid of depression much faster. This is especially important, because although drugs can control mania, a depressive episode of bipolar disorder is not so well controlled. nine0003

This is especially important, because although drugs can control mania, a depressive episode of bipolar disorder is not so well controlled. nine0003

Harvey and her colleagues began to apply similar principles to unipolar depression. She has unpublished data suggesting that if patients manage their sleep disturbances, they are less likely to relapse into depression. Another group found that treatment with cognitive-behavioral therapy, which is used for insomnia, helps to improve the condition of a patient with depression.

Walker refers to sleep as a therapy that lasts throughout the night. During PBS, the phase during which we dream, the brain's production of norepinephrine (also known as norepinephrine) is reduced. Norepinephrine is the brain's form of the stress hormone adrenaline, so its absence during FBS creates a calming neurochemical environment in which the brain can process turbulent events. “It essentially smooths out the sharp edges of the emotional experience,” Walker says. nine0003

nine0003

This process is disrupted in PTSD because too much norepinephrine is present in patients with this disorder, coupled with insufficient duration of FBS. It is interesting to note that Raskind has discovered that it is possible to treat traumatic nightmares with the blood pressure drug prazosin, which also blocks norepinephrine receptors in the brain.

A week after using prazosin, Hall told Raskind that for the first time since his military service in Vietnam, he slept through the night without waking. “I didn't know I was such a good psychotherapist,” Raskind recalls, “I was sure it was a placebo effect.” But after Raskind gave the medication to another Vietnam War veteran suffering from PTSD, he noticed that his condition also improved. Randomized trials have shown that prazosin improves sleep, reduces nightmares and other symptoms of combat-induced PTSD. Today, about 70,000 US Army veterans take this drug. Raskind reports that during the entire time of taking prazosin, Hall "keeps at bay" his nightmares. And it's noticeable. nine0003

And it's noticeable. nine0003

Raskind keeps another photograph in his office, from Hall's recent wedding, of an older-looking but more peaceful man: a portrait that reflects the role of a good night's sleep in healing the mind. “He looks a lot better here than in the photo with his wrinkled forehead,” Raskind says. “Notice the difference in his facial expression - it's the prazosin effect.”

Sleep disorders in anxiety and anxiety-depressive disorders | Kovrov G.V., Lebedev M.A., Palatov S.Yu., Merkulova T.B., Posokhov S.I. nine0001

In clinical practice, sleep disorders are usually associated with anxiety and depression. Existing studies show a close relationship between sleep disorders and anxiety and depressive disorders [1, 2]. A clear dependence of the severity of the course of both groups of diseases on concomitant sleep disorders was shown [1]. In general somatic practice, the prevalence of insomnia reaches 73% [3], in borderline psychiatry, clinically defined insomnia occurs in 65%, and changes in nocturnal sleep according to polysomnography are noted in 100% of cases [4]. nine0003

nine0003

Combination of sleep disorders and anxiety disorders

It is known that the relationship between sleep disorders and anxiety disorders is noted, on the one hand, when sleep disorders can provoke the development of anxiety disorders [5], and on the other hand, when the onset of an anxiety disorder precedes the onset of sleep disorders. Complaints about problems associated with sleep are typical for patients with all diseases included in the group of anxiety disorders. In the case of major generalized disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sleep disturbances are one of the criteria required for a diagnosis. There are objective reasons for the development of sleep disorders within anxiety disorders, namely: anxiety is manifested by increased cortical activation, which entails the difficulty of falling asleep and maintaining sleep. nine0003

In the clinic, anxiety is manifested by anxiety, irritability, motor excitation, decreased concentration of attention, increased fatigue [6].

The most striking manifestation of anxiety disorders is generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), which is diagnosed on the basis of the presence of at least 3 of the following symptoms: restlessness, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, sleep disturbances. The duration of the disease should be at least 6 months, the symptoms should cause psychosomatic discomfort and / or social disadaptation. nine0003

Sleep disorders in this situation are one of the 6 diagnostic criteria for GAD. The main symptom of GAD, excessive, persistent anxiety, is a major predisposing factor in the development of insomnia. Insomnia and GAD are closely related, usually comorbid disorders. The difference between insomnia in anxiety disorder and primary insomnia, not associated with other diseases, is the nature of the experiences in the process of falling asleep. In the case of GAD, the patient is concerned about current problems [7] (work, study, relationships), which hinders the process of falling asleep. In the case of primary insomnia, the anxiety itself is caused by the disease itself. nine0003

In the case of primary insomnia, the anxiety itself is caused by the disease itself. nine0003

A polysomnographic study can reveal changes characteristic of insomnia: increased time to fall asleep, frequent awakenings, reduced sleep efficiency, and a decrease in its total duration.

Another striking example of anxiety disorders is panic disorder, which is manifested by recurrent states of severe anxiety (panic). Attacks are accompanied by phenomena of depersonalization and derealization, as well as severe autonomic disorders. In the behavior of the patient, avoidance of situations in which the attack occurred for the first time is noted. There may be a fear of loneliness, a repetition of the attack. A panic attack occurs spontaneously, outside of formal situations of danger or threat. nine0003

Panic disorder is more common in women and typically begins around the age of 20. A hallmark of panic disorder are spontaneous episodes of panic attacks, characterized by bouts of fear, anxiety, and other autonomic manifestations. About 2/3 of patients with this disorder experience some form of sleep disturbance. Patients complain of difficulty falling asleep, non-restorative sleep, and characteristic nocturnal panic attacks. It should be noted that the presence of certain problems associated with sleep can lead to aggravation of anxiety disorders, including panic disorder. nine0003

About 2/3 of patients with this disorder experience some form of sleep disturbance. Patients complain of difficulty falling asleep, non-restorative sleep, and characteristic nocturnal panic attacks. It should be noted that the presence of certain problems associated with sleep can lead to aggravation of anxiety disorders, including panic disorder. nine0003

Polysomnographic examination can detect frequent awakenings, reduced sleep efficiency and a reduction in its total duration [8]. It is not uncommon to see depression coexisting with anxiety disorders, and it is possible that the presence of other changes in sleep patterns in patients with panic disorder is associated with comorbid depression, and therefore the diagnosis of depression should be ruled out in patients with similar sleep disorders.

The sleep paralysis characteristic of narcolepsy can also occur with panic disorder. It is a movement paralysis that occurs during falling asleep or waking up, during which patients experience fear, a feeling of pressure in the chest, and other somatic manifestations of anxiety. This symptom also occurs in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder.

This symptom also occurs in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Nighttime panic attacks are a common occurrence in this disease [9]. They are manifested by a sudden awakening and all the symptoms characteristic of panic attacks. Awakening occurs during the phase of non-REM sleep, which most likely excludes their connection with dreams. It was also found that nocturnal attacks are an indicator of a more severe course of the disease. It must be remembered that patients, fearing the recurrence of such episodes, deprive themselves of sleep, which leads to more serious disorders and, in general, reduces the quality of life of these patients.

PTSD is a disease from the group of anxiety disorders, in which sleep disturbances are a diagnostic criterion. Sleep disorders in this disease include 2 main symptoms: nightmares and insomnia. Other phenomena inherent in PTSD and associated with sleep are: somnambulism, sleep-talking, hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations. The changes detected by polysomnography are not specific and in some cases may be absent. Possible changes include: an increase in the representation of the 1st stage of sleep, a decrease in the representation of the 4th stage of sleep. Also, with PTSD, breathing disorders during sleep are often found. nine0003

The changes detected by polysomnography are not specific and in some cases may be absent. Possible changes include: an increase in the representation of the 1st stage of sleep, a decrease in the representation of the 4th stage of sleep. Also, with PTSD, breathing disorders during sleep are often found. nine0003

Agoraphobia can also be a manifestation of anxiety disorders, which is defined as anxiety that occurs in response to situations, the way out of which, according to the patient, is difficult. In the clinical picture, as a rule, there is a persistent fear of the patient to be in a crowded place, public places (shops, open squares and streets, theaters, cinemas, concert halls, workplaces), fear of independent long trips (by various modes of transport). The situational component of the agoraphobia syndrome is expressed in the confinement of phobic experiences to certain situations and in the fear of getting into situations in which, according to patients, a repetition of painful sensations is likely. Often, agoraphobic symptoms cover many fears of various situations, forming panagoraphobia - the fear of leaving the house with the development of deep social maladaptation. There are attempts by the patient to overcome their own experiences, in adverse cases, there is a restriction of social activity. nine0003

Often, agoraphobic symptoms cover many fears of various situations, forming panagoraphobia - the fear of leaving the house with the development of deep social maladaptation. There are attempts by the patient to overcome their own experiences, in adverse cases, there is a restriction of social activity. nine0003

Specific phobias are characterized by an association of anxiety with certain situations (air travel, contact with animals, the sight of blood, etc.), also accompanied by an avoidance reaction. Patients are critical of their experiences, however, phobias have a significant impact on various areas of activity of patients. There are the following forms: cardiophobia, cancerophobia, claustrophobia, etc. Sleep disturbances in these patients are non-specific, and from the point of view of the patient, they are a minor manifestation of the disease. nine0003

In general, the most common manifestations of sleep disturbances in anxiety states are presomnic disorders. The initial phase of sleep consists of 2 components: drowsiness, a kind of craving for sleep, and actually falling asleep. Often, patients have no desire to sleep, no desire to sleep, muscle relaxation does not occur, they have to perform various actions aimed at falling asleep. In other cases, there is an inclination to sleep, but its intensity is reduced, drowsiness becomes intermittent, undulating. Drowsiness occurs, the muscles relax, the perception of the environment decreases, the patient takes a comfortable position for falling asleep, and a slight drowsiness appears, but soon it is interrupted, disturbing thoughts and ideas arise in the mind. In the future, the state of wakefulness is again replaced by mild drowsiness and superficial drowsiness. Such changes in states can be repeated several times, leading to emotional discomfort that prevents the onset of sleep. nine0003

Often, patients have no desire to sleep, no desire to sleep, muscle relaxation does not occur, they have to perform various actions aimed at falling asleep. In other cases, there is an inclination to sleep, but its intensity is reduced, drowsiness becomes intermittent, undulating. Drowsiness occurs, the muscles relax, the perception of the environment decreases, the patient takes a comfortable position for falling asleep, and a slight drowsiness appears, but soon it is interrupted, disturbing thoughts and ideas arise in the mind. In the future, the state of wakefulness is again replaced by mild drowsiness and superficial drowsiness. Such changes in states can be repeated several times, leading to emotional discomfort that prevents the onset of sleep. nine0003

In a number of patients, experiences about disturbed sleep can acquire an overvalued hypochondriacal coloration and come to the fore according to the mechanisms of actualization, often there is an obsessive fear of insomnia - agripnophobia. It is usually combined with an anxious and painful expectation of sleep, certain requirements for others and the creation of the above-mentioned special conditions for sleep.

It is usually combined with an anxious and painful expectation of sleep, certain requirements for others and the creation of the above-mentioned special conditions for sleep.

Anxiety depression is characterized by the patient's constant experience of anxiety, a sense of impending danger and insecurity. Anxious experiences change: anxiety about their loved ones, fears about their condition, their actions. The structure of anxious depression, as a rule, includes anxiety, feelings of guilt, motor restlessness, fussiness, fluctuations in affect with worsening in the evening, and somatovegetative symptoms. Anxious and melancholy affects often occur simultaneously, in many cases it is impossible to determine which of them is leading in the patient. Anxiety depression is most often found in people of involutionary age and proceeds according to the type of protracted phases. In addition, it is actually the leading type of neurotic depression [10]. nine0003

The patient exhibits a variety of symptoms of anxiety and depression. Initially, one or more physical symptoms (eg, fatigue, pain, sleep disturbances) may be present. Further questioning allows us to state a depressive mood and/or anxiety.

Initially, one or more physical symptoms (eg, fatigue, pain, sleep disturbances) may be present. Further questioning allows us to state a depressive mood and/or anxiety.

Signs of anxiety depression:

- depressed mood;

- loss of interest;

- severe anxiety.

The following symptoms are also often seen: nine0003

- sleep disorders;

- physical weakness and loss of energy;

- fatigue or decreased activity;

- difficulty concentrating, fidgeting;

- impaired concentration;

- excitation or retardation of movements or speech;

- appetite disorders;

- dry mouth;

- tension and anxiety;

- irritability; nine0114

- tremor;

- heartbeat;

- dizziness;

- suicidal thoughts.

Often with anxiety depression, variants of presomnic disorders are observed, in which the desire to sleep is pronounced, drowsiness increases rapidly, and the patient falls asleep relatively easily, but wakes up suddenly after 5-10 minutes, drowsiness completely disappears, and then within 1-2 hours he does not can fall asleep. This period without sleep is characterized by unpleasant ideas, thoughts, fears, reflecting to a greater or lesser extent the experienced conflict situation and the reaction to the inability to sleep. There is also hyperesthesia to sensory stimuli. Those suffering from this form of sleep disorder react extremely painfully to the slightest sensory stimuli, up to flashes of affect. nine0003

This period without sleep is characterized by unpleasant ideas, thoughts, fears, reflecting to a greater or lesser extent the experienced conflict situation and the reaction to the inability to sleep. There is also hyperesthesia to sensory stimuli. Those suffering from this form of sleep disorder react extremely painfully to the slightest sensory stimuli, up to flashes of affect. nine0003

For disturbed falling asleep, lengthening of the drowsy period is characteristic. This drowsy state is often accompanied by motor, sensory and visceral automatisms, sharp shudders, vivid perceptions of sounds and visual images, palpitations, sensations of muscle spasms. Often these phenomena, awakening the patient, cause various painful ideas and fears, sometimes acquiring an obsessive character.

Sleep disorders and their polysomnographic manifestations among mental illnesses are the most studied for depressive disorder. Among the sleep disorders in depressive disorder, insomnia is the most common. The severity and duration of insomnia are manifestations of a more severe depressive disorder, and the appearance of insomnia during remission indicates the imminent occurrence of a recurrent depressive episode [1]. In addition, sleep disorders in this disease are the most persistent symptom. The close relationship of this disorder with sleep disorders is explained by the biochemical processes characteristic of depression. In particular, in depressive disorder, there is a decrease in the level of serotonin, which plays a role in the initiation of REM sleep and the organization of delta sleep [11]. Depressive disorder is characterized by the following manifestations of sleep disturbances: difficulty falling asleep [10], non-restorative sleep, as a rule, reduced total sleep time. The most specific symptoms for depression are frequent nocturnal awakenings and early terminal awakenings. Complaints about difficulty falling asleep are more often observed in young patients, and frequent awakenings are more characteristic of the elderly [12].

The severity and duration of insomnia are manifestations of a more severe depressive disorder, and the appearance of insomnia during remission indicates the imminent occurrence of a recurrent depressive episode [1]. In addition, sleep disorders in this disease are the most persistent symptom. The close relationship of this disorder with sleep disorders is explained by the biochemical processes characteristic of depression. In particular, in depressive disorder, there is a decrease in the level of serotonin, which plays a role in the initiation of REM sleep and the organization of delta sleep [11]. Depressive disorder is characterized by the following manifestations of sleep disturbances: difficulty falling asleep [10], non-restorative sleep, as a rule, reduced total sleep time. The most specific symptoms for depression are frequent nocturnal awakenings and early terminal awakenings. Complaints about difficulty falling asleep are more often observed in young patients, and frequent awakenings are more characteristic of the elderly [12]. nine0003

nine0003

With masked depression, complaints of sleep disturbances may be the only manifestation of the disease. In depression, in contrast to primary insomnia, there are complaints of sleep disturbances typical of this disease: frequent awakenings, early morning awakening, etc. [12].

In polysomnographic study, the following changes are observed: an increase in the time to fall asleep, a decrease in sleep efficiency. The most common and depressive disorder-specific symptoms are shortened REM sleep latency and reduced delta sleep. It has been found that patients with a higher proportion of delta sleep stay in remission longer than those with a decrease in the proportion of delta sleep [13]. nine0003

Attempts have been made to explore the possibility of using depression-specific sleep disturbances as markers of depressive disorder. Due to the heterogeneity of the manifestations of sleep disorders, this issue remains not fully resolved.

The features of sleep disorders in various types of depression were also highlighted. For patients with a predominance of the anxious component, difficulty falling asleep and early awakenings are more characteristic. With this type of depression, dream plots are associated with persecution, threats, etc. In addition, in these patients, in general, there was a high level of wakefulness before falling asleep. For depressions with the leading affect of melancholy, early morning awakenings and dreams of static types of gloomy content are most characteristic. Depression with the affect of apathy is characterized by early awakenings and rare, unsaturated dreams. Also typical of depression with apathetic affect is the loss of a sense of boundaries between sleep and wakefulness. Patients with bipolar disorder have a similar polysomnographic pattern [14]. nine0003

For patients with a predominance of the anxious component, difficulty falling asleep and early awakenings are more characteristic. With this type of depression, dream plots are associated with persecution, threats, etc. In addition, in these patients, in general, there was a high level of wakefulness before falling asleep. For depressions with the leading affect of melancholy, early morning awakenings and dreams of static types of gloomy content are most characteristic. Depression with the affect of apathy is characterized by early awakenings and rare, unsaturated dreams. Also typical of depression with apathetic affect is the loss of a sense of boundaries between sleep and wakefulness. Patients with bipolar disorder have a similar polysomnographic pattern [14]. nine0003

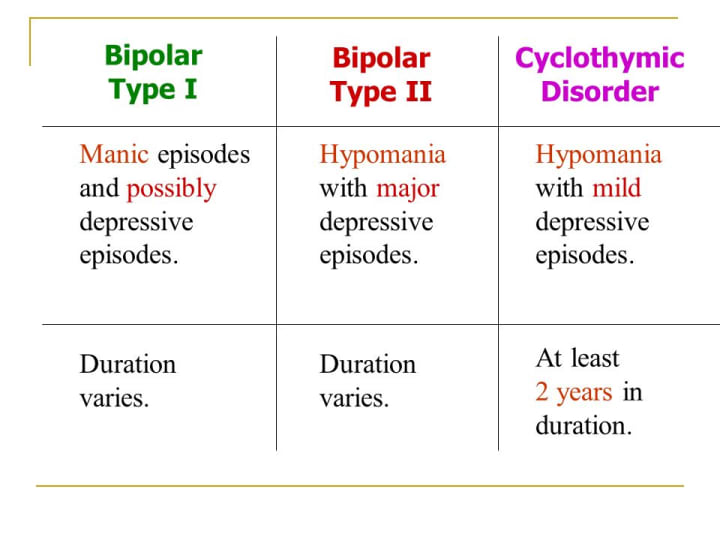

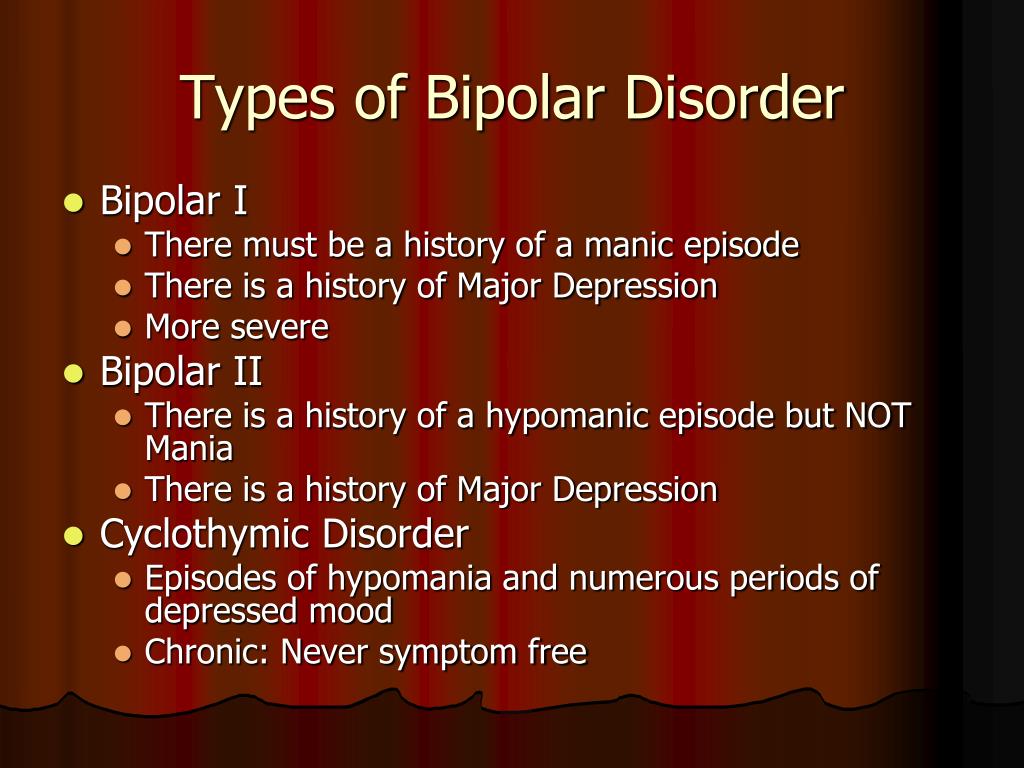

Features of sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder are a significant decrease in the duration of sleep during a manic episode and a greater tendency of patients to hypersomnia during depressive episodes compared with the unipolar course of the disorder. Complaints of sleep disturbances during manic episodes are usually absent.

Complaints of sleep disturbances during manic episodes are usually absent.

Treatment

For the treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders, drugs of various pharmacological groups are used: tranquilizers (mainly long-acting or short-acting benzodiazepine drugs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake stimulants, tricyclic antidepressants. All these drugs, to one degree or another, affect a person’s sleep, making it easier to fall asleep, reducing the number and duration of nocturnal awakenings, thereby affecting the recovery processes that occur during a night’s sleep. When constructing tactics for the treatment of sleep disorders associated with anxiety and depressive manifestations, it is important to remember that insomnia itself can increase anxiety, worsen well-being, mood, as a rule, in the morning hours after poor sleep [15]. In this regard, the use of hypnotics in the treatment may be promising in the presence of a predominance of insomnia symptoms in the clinical picture in order to prevent exacerbation of anxiety and depressive disorders. In this regard, the most effective helpers can be sleeping pills that affect the GABAergic (GABA - γ-aminobutyric acid) system - histamine receptor blockers (Valocordin®-Doxylamine) and melatonin preparation. The most convenient to use in the treatment of insomnia is Valocordin®-Doxylamine, which is available in drops, which allows you to select an individual dose of the drug. nine0003

In this regard, the most effective helpers can be sleeping pills that affect the GABAergic (GABA - γ-aminobutyric acid) system - histamine receptor blockers (Valocordin®-Doxylamine) and melatonin preparation. The most convenient to use in the treatment of insomnia is Valocordin®-Doxylamine, which is available in drops, which allows you to select an individual dose of the drug. nine0003

Valocordin®-Doxylamine is a unique drug used as a hypnotic. Most known hypnotic drugs (benzodiazepines, cyclopyrrolones, imidazopyridines, etc.) act on the GABAergic complex, activating the activity of somnogenic systems, while histamine receptor blockers act on wakefulness systems, not sleep ones, reducing their activation. A fundamentally different mechanism of hypnotic action makes it possible to use Valocordin®-Doxylamine more widely: when changing one drug to another, reducing the dosages of "habitual hypnotics", and also, if necessary, canceling hypnotics. nine0003

A drug study conducted on healthy subjects showed that doxylamine succinate leads to a decrease in the duration of nocturnal awakenings and stage 1 sleep and an increase in stage 2 without a significant effect on the duration of stages 3 and 4 sleep and REM sleep. There was no significant subjective effect on the reports of healthy volunteers, however, compared with placebo, doxylamine increased the depth of sleep and improved its quality [16].

There was no significant subjective effect on the reports of healthy volunteers, however, compared with placebo, doxylamine increased the depth of sleep and improved its quality [16].

In Russia, one of the first studies was carried out under the supervision of A.M. Wayne [17]. It has been shown that under the influence of doxylamine such subjective characteristics of sleep as the duration of falling asleep, the duration and quality of sleep, the number of night awakenings and the quality of morning awakenings improve. An analysis of the objective characteristics of sleep showed that while taking doxylamine, there was a reduction in the time of wakefulness during sleep, a decrease in the duration of falling asleep, an increase in the duration of sleep, the time of the REM sleep phase, and the sleep quality index. It was also shown that doxylamine did not reduce the effectiveness of other drugs in patients, such as antihypertensive, vasoactive, etc. The results of a study of the effect of doxylamine on patients with insomnia indicate the effectiveness of this drug in these patients. Subjective feelings of a positive effect are confirmed by objective studies of the structure of sleep, which undergoes positive shifts, which affect such indicators as sleep duration, falling asleep duration, REM sleep phase. Of great importance is also the absence of any changes in the results of personal data regarding drowsiness and sleep apnea syndrome, which indicates the absence of an aftereffect of the drug in relation to the worsening of the course of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. However, if obstructive sleep apnea is suspected, doxylamine should be used with caution. nine0003

Subjective feelings of a positive effect are confirmed by objective studies of the structure of sleep, which undergoes positive shifts, which affect such indicators as sleep duration, falling asleep duration, REM sleep phase. Of great importance is also the absence of any changes in the results of personal data regarding drowsiness and sleep apnea syndrome, which indicates the absence of an aftereffect of the drug in relation to the worsening of the course of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. However, if obstructive sleep apnea is suspected, doxylamine should be used with caution. nine0003

Modern clinical studies do not reveal serious side effects in the treatment of therapeutic doses of the drug, but it is always necessary to remember the possible appearance of symptoms that arise due to the individual characteristics of the body, and contraindications (glaucoma; difficulty urinating due to benign prostatic hyperplasia; age up to 15 years; increased drug sensitivity).

Simultaneous administration of the drug Valocordin®-Doxylamine and sedative drugs that affect the central nervous system (CNS): neuroleptics, tranquilizers, antidepressants, hypnotics, analgesics, anesthetics, antiepileptic drugs, may enhance their effect. Procarbazines and antihistamines should be combined with caution to minimize CNS depression and potential drug potentiation. During treatment with Valocordin®-Doxylamine, alcohol should be avoided as it may unpredictably affect the effects of doxylamine succinate. nine0003

Procarbazines and antihistamines should be combined with caution to minimize CNS depression and potential drug potentiation. During treatment with Valocordin®-Doxylamine, alcohol should be avoided as it may unpredictably affect the effects of doxylamine succinate. nine0003

During the use of this drug, it is recommended to exclude driving a car and working with mechanisms, as well as other activities accompanied by an increased risk, at least at the first stage of treatment. The attending physician is advised to evaluate the individual reaction rate when choosing a dose. It is important to consider these features of the effect of the drug in the treatment of patients with insomnia in order to increase the effectiveness of Valocordin®-Doxylamine and exclude possible undesirable effects. nine0003

Conclusion

When diagnosing a disease, it is important to remember that, as a rule, problems falling asleep indicate the presence of severe anxiety, early awakenings are a manifestation of depression.