How to get help for mentally ill person

I'm looking for mental health help for someone else

I'm looking for mental health help for someone else

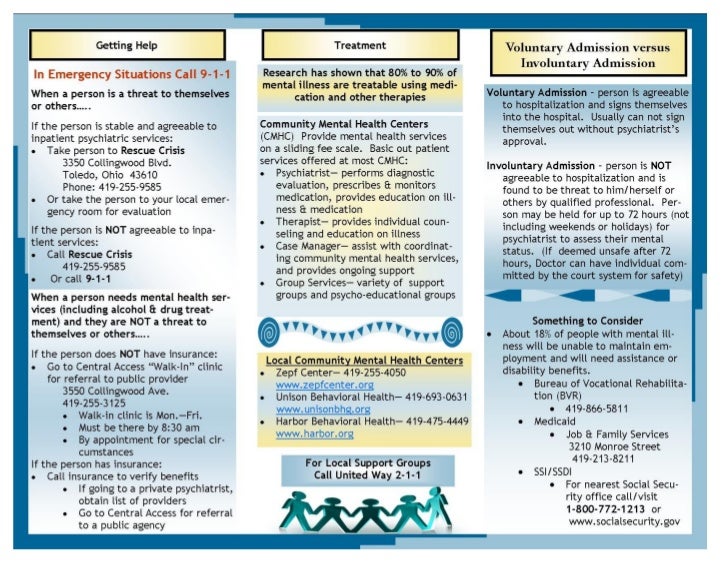

If you or someone you know is in crisis, please seek help immediately.

Below are some options for immediate support.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org.

Text MHA to 741741 to connect with a trained Crisis Counselor from Crisis Text Line.

Call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room.

If you are in need of support, but not in crisis, consider reaching out to a warmline. Warmlines offer a place to call when you just need to talk to someone. Speaking to someone on these calls is typically free, confidential, and run by people who understand what it’s like to struggle with mental health problems.

Find a warmline at mhanational.org/warmlines.

Mental health is a critical part of overall health. If you're feeling distressed, there is hope.

If the person you care about is still in school, our Back To School or Life On Campus materials may better fit your needs.

Which best describes the person you care about?

The person I care about doesn't have any concerns right now, but they would like to stay mentally healthy.

- Encourage them to monitor their mental health regularly by taking one of our Nine Validated Screens.

- Learn about ways to live well and stay well. Follow these tips yourself, or share with the person you care about.

- Read up on risk factors and early warning signs.

- Get tips for boosting mental health.

The person I care about is showing symptoms of a mental health condition. They are doing okay at home, work, or school, but not as easy as before. Something is “not right.”

- Encourage them to take a mental health screen, print the results out, and bring them to a doctor or a mental health provider.

- Suggest our interactive "where to get help” feature.

- Find an affiliate in your community. You can contact an affiliate as a concerned party or encourage the person you care about to do so. There may be limits to what someone else can share.

- Learn more about mental health conditions. Get informed so you can be a good caretaker.

- Read up about the different treatments.

- Find a therapist.

- Use this worksheet with a friend or loved one to think ahead and map out steps they can take to get help and feel better.

- If you are the parent of a child or teen who is showing signs of a mental health problem:

- Get tips for starting a conversation

- Learn more about what to do and where to go

The person I care about is starting to have trouble with family, friends, work, school or other areas of his or her life. Things are getting worse, and sometimes multiple problems are developing.

- Take a mental health screen, print the results out, and bring them to a doctor.

Or discuss the results with a family member or close friend.

Or discuss the results with a family member or close friend. - Try out our interactive “where to get help” feature.

- Look up your local MHA affiliate.

- Find a therapist.

- Find a support group.

- Learn more about mental health conditions.

- Find strategies to support a friend or loved one who is dealing with a mental illness.

Things are getting bad for the person I care about. He or she appears to be losing control of his or her life and ability to work, go to school, or be there for friends and family.

- Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org or text MHA to 741741 if you are in crisis.

- Look up your local MHA affiliate for services in your area.

- Find a therapist.

- Find a support group.

- Plan for crisis by setting up a Psychiatric Advance Directive.

- Is hospitalization necessary?

- Read more about inpatient options.

- Learn about how you can support a friend or loved one who is dealing with a mental illness.

- Tips for being an effective caregiver

The person I care about is in crisis.

- Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org to reach a 24-hour crisis center, text MHA to 741741, call 911, or go to the nearest emergency room.

- Find a local MHA affiliate who can provide services.

- Find a therapist.

- Find support groups.

- Find a hospital.

- Learn about rights and resources as a caregiver of a person with a mental illness

B4Stage4 -- Where to get help

Skip to main contentSearch

When you’ve decided to seek help, knowing what resources are available and where to start can be tricky. Answer the questions below to help you figure out your options for getting help.

Are you in a mental health crisis? (thinking about hurting yourself or someone else)?If you are in need of immediate assistance, please call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or chat 988lifeline. org. You can also text MHA to 741741 to talk to a trained counselor from the Crisis Text Line. Warmlines are also an excellent place for support.

org. You can also text MHA to 741741 to talk to a trained counselor from the Crisis Text Line. Warmlines are also an excellent place for support.

If you are in junior high school or high school:

Your guidance counselor or school nurse can help you find resources or additional assistance, and can also help you talk to your parents about the difficulties you’re having.

Teens can also text “MHA” to 741741 for 24/7 confidential crisis text services.

If you are a college student:

Your college or university’s Campus Health Center is a good place to start. Typically they offer counseling services for little or no cost or can connect you with providers who work with the campus. You may also be able to find additional resources through the Office of Student Life.

Many campuses have an Active Minds chapter, which can be a good place to find support from other students on campus who may be having difficulties with mental health. See if your school has an Active Minds chapter by using the interactive map at https://www.activeminds.org/programs/chapter-network/.

See if your school has an Active Minds chapter by using the interactive map at https://www.activeminds.org/programs/chapter-network/.

ULifeline.org can also connect students with resources.

If you are covered by your parents’ health insurance:

Your family doctor can provide referrals to mental health specialists or prescribe medication to help with your symptoms. They will likely suggest that you see a specialist if this is the first time that you are seeking help for a mental health issue and don’t have a diagnosis.

Your insurance company may require that you have treatment by a mental health specialist like a psychiatrist, psychologist or therapist authorized (usually for multiple sessions) before a visit. You will be able to find specifics by visiting your health insurance company’s website or calling their customer service number (typically on the back of your insurance card). Ask your parents to help you with the details.

Want more information about how insurance works? How Insurance Works

If you would like some help figuring out the differences between types of mental health professionals, treatment options, and more, visit /finding-right-care and /conditions/b4stage4-get-help .

If you would like to try some other options, here are some additional places to go for help:

Local MH Centers - Finding Therapy

MHA affiliates Find an Affiliate

Do you have health insurance? Do you have insurance through a government program, like Medicaid or Medicare? Do you work for an employer who offers an Employee Assistance Program (EAP)?PCP/Insurance Company

Primary Care Provider (PCP)

Your family doctor can provide referrals to mental health specialists or prescribe medication to help with your symptoms. They will likely suggest that you to see a specialist if this is the first time that you are seeking help for a mental health issue and don’t have a diagnosis.

Your insurance company may require that you have treatment by a mental health specialist like a psychiatrist, psychologist or therapist authorized (usually for multiple sessions) before a visit. You will be able to find specifics by visiting your health insurance company’s website or calling their customer service number (typically on the back of your insurance card). You can also ask your employer’s HR person to help you understand your plan’s behavioral health benefits.

You can also ask your employer’s HR person to help you understand your plan’s behavioral health benefits.

Want more information about how insurance works? /how-insurance-works

If you would like some help figuring out the differences between types of mental health professionals, treatment options, and more, visit Finding The Right Care and /conditions/b4stage4-get-help .

Local MHA Affiliate

Mental Health America has hundreds of affiliates across the country whose primary purpose it is to help members of the community find and access help for mental health concerns, conditions and illnesses. Services provided by MHAs vary, so you will need to explore what is available by finding the MHA closest to you.

Your MHA affiliate will know the local community and many of them can put you in touch with peer support from other people who have experienced similar difficulties with mental health, and help you find additional information and resources for mental health treatment.

Find your local affiliate by going to Find Affiliate.

If you would like some help figuring out the differences between types of mental health professionals, treatment options, and more, visit /finding-right-care and /conditions/b4stage4-get-help .

If you would like to try some other options, here are some additional places to go for help:

Local MH Centers - Finding Therapy

Download/View PDF

Help for a loved one with a mental disorder

Basic concepts

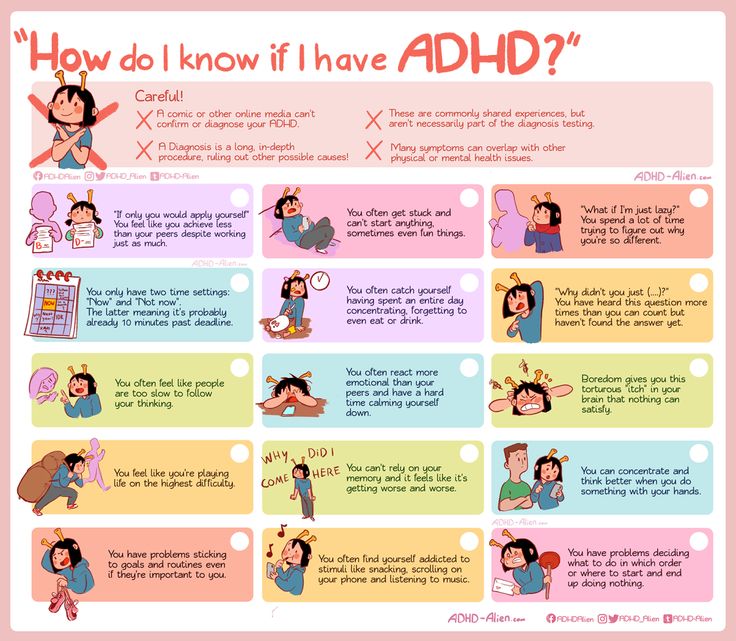

There is a lot of talk these days about the rise in the number of mental disorders in society, but many people have very vague ideas about this very vague concept. Despite the fact that now psychiatrists are doing everything possible to inform the population as best as possible about stress, depression, anxiety, neuroses, more severe mental disorders, there is very little literature written by experts for the average layman, and on the Internet there is an abundance of information written either difficult language, or simply illiterate. All this ultimately leads to the fact that such information is not only contrary to reality, but also harmful.

All this ultimately leads to the fact that such information is not only contrary to reality, but also harmful.

It is impossible to sort everything out in one article and give clear instructions on the relationship between the patient and his relatives, but it is possible to bring to a holistic picture the idea of this complex group of diseases (the terms "disease" and "disorder" from a medical point of view are largely close, but not identical*). Therefore, my task is to acquaint the reader with this complex problem, primarily related to relationships and assistance to those suffering from severe mental illnesses.

* It is desirable to know the most basic terms, then it will be easier for the doctor to help both the patient himself and his relatives. In addition, you should not use terms that are not well known to you, it is better to describe the situation or condition as you understand it.

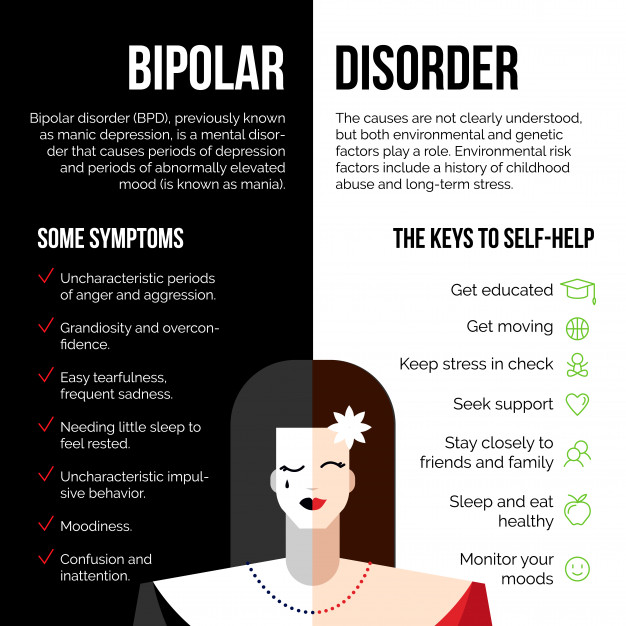

So, mental (or mental, because psyche - translated from Greek means the soul ) disorders - are painful conditions of a person with psychopathological (i. e., with mental disorders) and behavioral (i.e., they do not always appear, for example, in case of neurosis, when a person by willpower keeps himself within the limits of cultural society up to a certain point) manifestations due to the influence of biological, psychological, social and other factors.

e., with mental disorders) and behavioral (i.e., they do not always appear, for example, in case of neurosis, when a person by willpower keeps himself within the limits of cultural society up to a certain point) manifestations due to the influence of biological, psychological, social and other factors.

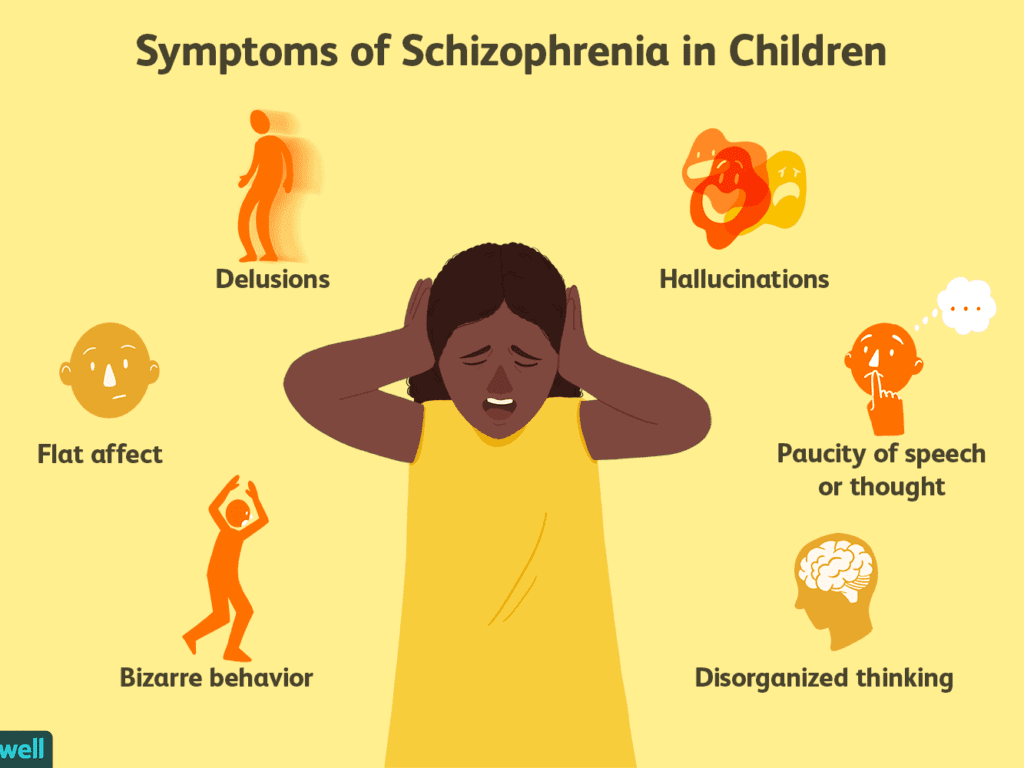

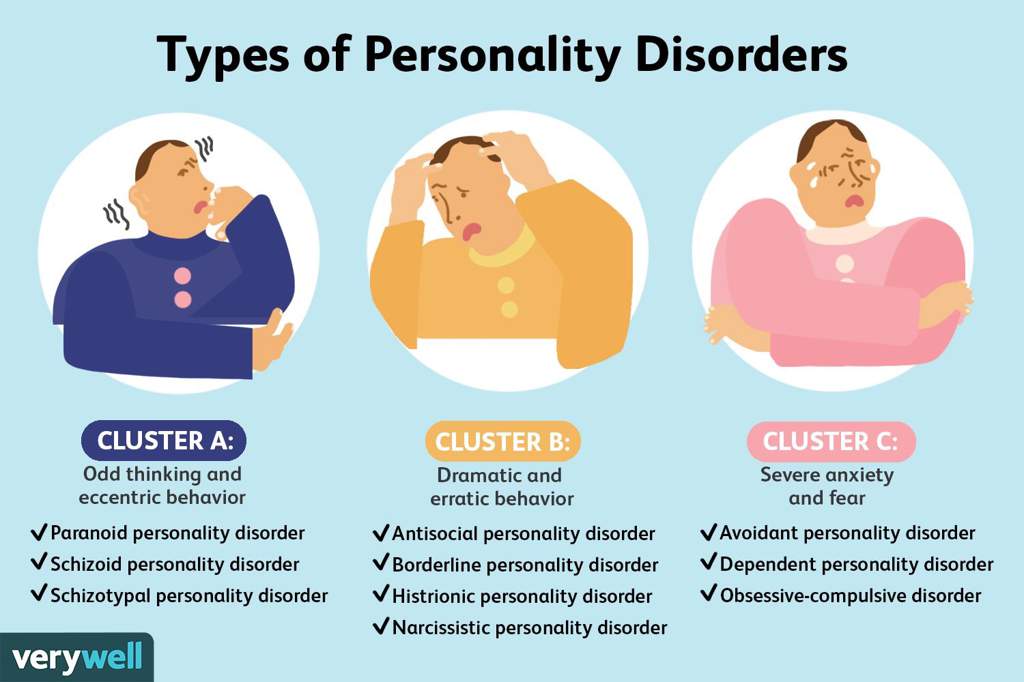

Let's not confuse with psychosis (or psychotic) disorders, which are characterized by gross and contradictory environmental disorders of thinking, perception and behavior (delusions, in a medical, not philistine view; hallucinations; psychomotor agitation; suicidal behavior, etc.).

It is important to note that the problem of mental disorders is interdisciplinary and even interdepartmental, social. Rehabilitation is needed, not just treatment.

As for the diagnosis. Diagnosis - definition and recognition, an indication of the disease. In medicine, and especially in psychiatry, diagnosis does not always mean treatment in strict accordance with the diagnosis. Diagnosis is often a statistical category needed to understand, roughly speaking, how the condition of one patient is similar to another.

Diagnosis is often a statistical category needed to understand, roughly speaking, how the condition of one patient is similar to another.

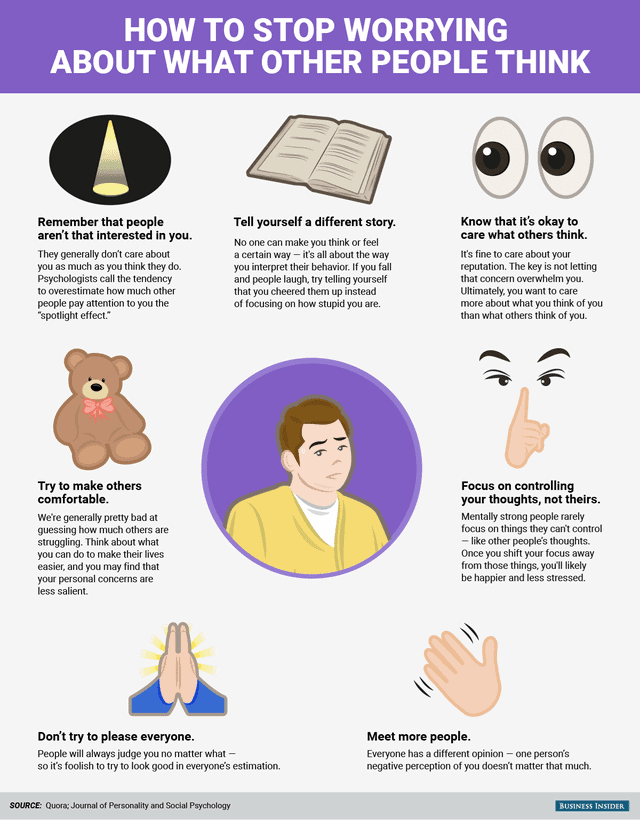

I am sometimes puzzled by the desire of a person to look at the records of a doctor. After all, a special interpretation, justification of the diagnosis, terminology can not only frighten and offend an unprepared person, but cause unreasonable distrust of a specialist and, even worse, aggravate disturbed mental balance, upset not only the patient, but also relatives.

It is much more important to trust each other (the doctor, the patient, his relatives), to ask questions of interest. It is on trust that the desired result is achieved - a cure or a stable remission, if the disorder is chronic.

I will not decipher concepts and terms much in this article. Let's talk about the topic corresponding to the title. We will talk about such diseases as schizophrenia, dementia, severe depression, drug addiction (alcoholism, drug addiction), etc. I will try to give basic, a kind of "universal" recommendations.

I will try to give basic, a kind of "universal" recommendations.

Recommendations

1 situation: a relative (both a 16-year-old child and an old grandfather, a researcher in the past or present) became “somehow not like that”, began to withdraw, get annoyed for no apparent reason, although “he had never been aggressive before ', to talk, to talk to oneself.

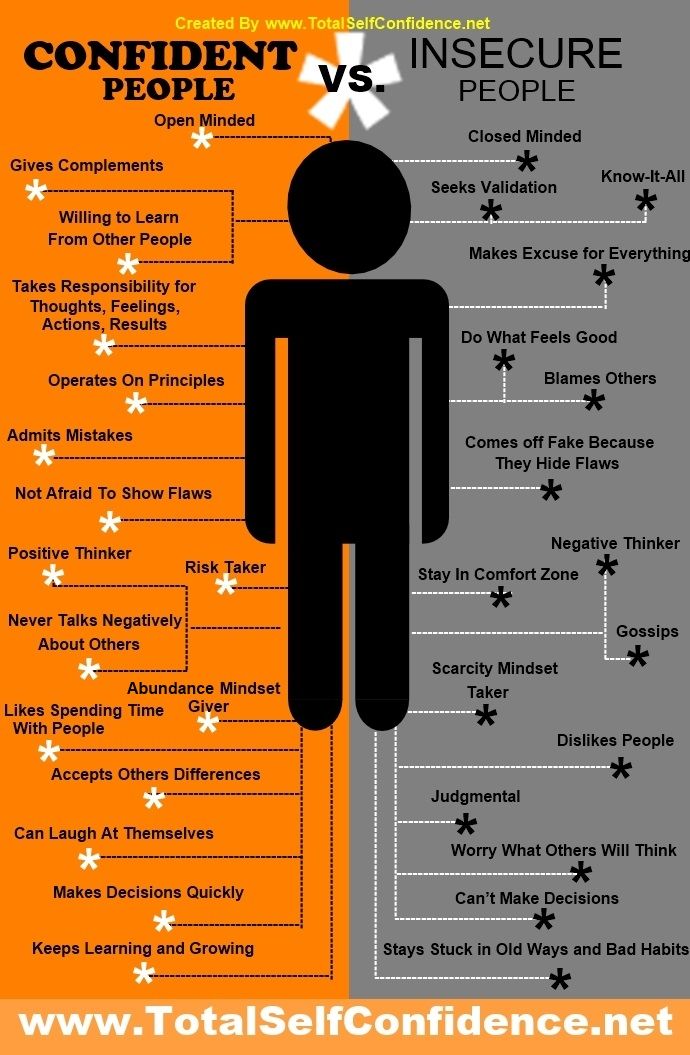

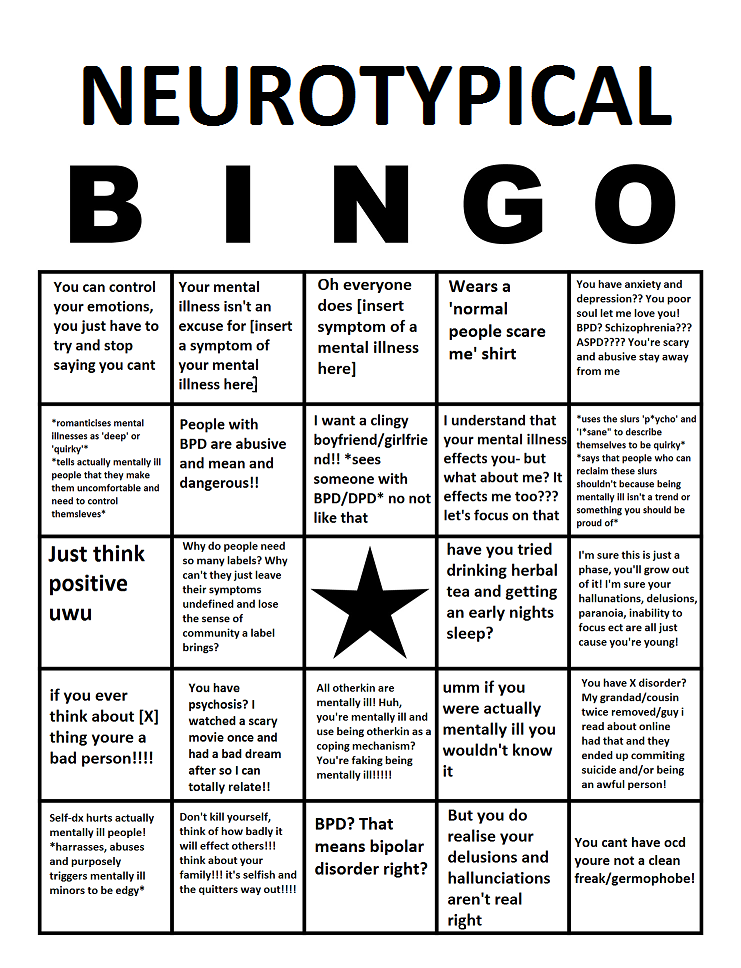

Usually, such behavior is first perceived as a joke, then surprise, then a discussion with a sick person begins, which can lead to serious conflicts and distrust. If you suspect that a person close to you has a mental disorder (we do not take emergency situations, for example, in case of severe aggression, the police and medical workers are already intervening here), you cannot argue.

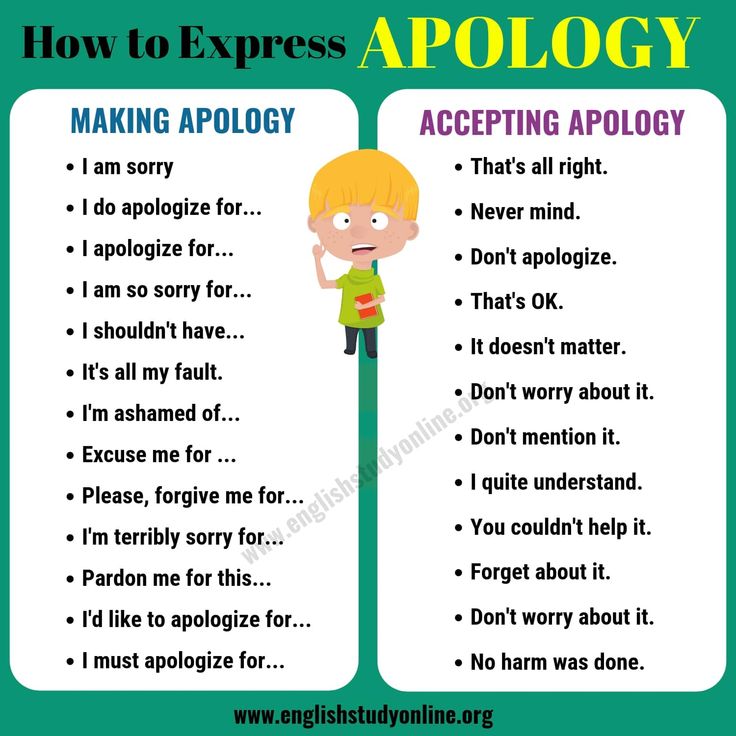

It is also desirable not to support the painful delusions of a person, to try to be patient and caring, to persuade a loved one to seek medical help. Unfortunately, in our society, when it comes to psychiatry, in most cases it causes a smile, fear, surprise, but not sympathy and a desire to help a sick person, especially if it refers to a relative. Only later, when a sick person can feel and even understand that the help of a psychiatrist is for his benefit, will he himself reach out to her.

Only later, when a sick person can feel and even understand that the help of a psychiatrist is for his benefit, will he himself reach out to her.

At the initial stage, it is worth trying to persuade a person to calm down, assess his degree of adequacy (if he used to trust you, but now he doesn’t groundlessly, whether he understands you or is completely in his experiences, etc.), to understand whether there are threats to him and surrounding.

It is impossible to forcibly help a person (involuntary hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital is carried out only by a court decision), but everything possible must be done: to involve relatives who will correctly understand and support people who are authoritative for the patient, consult a doctor.

Situation 2: patients were brought to a psychiatrist. There can be 2 ways here. The doctor will help to understand the situation, make a diagnosis, prescribe treatment, give recommendations. Everything here is very individual. But it may also be that the doctor gives a recommendation, but not only the patient (due to inadequacy), but also a relative does not want to follow it.

But it may also be that the doctor gives a recommendation, but not only the patient (due to inadequacy), but also a relative does not want to follow it.

I can give an example. A mother brings her 20-year-old daughter to a psychotherapist. The daughter has painful sensations in her body: the bones, according to her, “go back and forth, fall through and hurt.” All specialists were examined, all studies were carried out, including MRI, no diseases were found, the symptoms do not correspond to the alleged physical pathology.

A mental illness was diagnosed, drugs were prescribed, and after a couple of months there was a significant improvement. The patient stops taking the medicine, after a while she comes to the doctor with her mother, complains about the deterioration, assures that the medicines do not help, refuses help, runs out of the office, rushes about, says that she does not want to live. Hospitalization is proposed, since adequate dosages of drugs can only be prescribed in a hospital, in response - a categorical refusal.

With difficulty he manages to calm down, persuade him to give an injection, agrees to resume taking medications. The doctor suggests that the mother call a psychiatric team to resolve the issue of hospitalization, in connection with the suicidal risk, to which he receives the answer: “Well, she will kill herself, then this is her fate, I will not put her in a psychiatric hospital.” On receipt released home. The mother calls the next day, the daughter gets a little better, then disappears for six months. Another call to the doctor's personal phone: the daughter lies in bed, does not want to get up, complains about "movements in the body of some creatures" that cause severe pain.

Recommendations were given, the patient was finally hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital with schizophrenia. She was discharged with improvement, criticism of her condition appeared, adequate therapy was selected.

Bottom line: fortunately, this story ended happily, but the patient suffered for several months, while the mother believed in the need for hospitalization; I had to prescribe heavier drugs, the treatment was delayed.

There is nothing wrong if the patient refuses this doctor (for example, the patient has included the doctor in his delusional system) or the doctor himself understands that he will not be able to provide adequate assistance. Then it is necessary to attract colleagues, send them to a hospital, together with relatives, think over options for assistance and choose the best one. It happens that the patient returns after treatment, apologizes for his behavior, because he did not understand the pain and inadequacy at that time.

You should not change specialists (sometimes people come to me with dozens of recommendations from different doctors of the same specialty, which is puzzling). Well, 2-3 opinions is understandable, but more than 10!? The most common reason is that medications do not immediately help, side effects.

Some patients soon stop taking their medications, and many diseases are chronic and require many months or even years of maintenance therapy. A natural deterioration sets in, the new doctor does not yet know the specifics of the course of the disorder in this patient, experiments with treatment begin, a new selection of medicines begins, resistance to treatment is formed, and previously effective drugs cease to work.

A natural deterioration sets in, the new doctor does not yet know the specifics of the course of the disorder in this patient, experiments with treatment begin, a new selection of medicines begins, resistance to treatment is formed, and previously effective drugs cease to work.

And one more thing: it is desirable, at the initial visit to the doctor, to bring, if not all, then the main examinations, extracts, and tests. A psychiatrist is a doctor like everyone else, and the more information about the patient, the easier it is to understand the diagnosis. For example, if a person has a pathology of the thyroid gland, it is advisable to bring the last tests for hormones, since when the hormonal background changes, the state of mind also changes (irritability, sleep disturbances, mood swings, etc.).

In some cases, antidepressants are not only not needed, but can be harmful, it may be worth limiting yourself to the appointments of an endocrinologist and psychotherapy. Elderly people with diabetes can confuse events and even behave inappropriately with an increase in blood glucose, here prescribed antipsychotics are also not always necessary.

Elderly people with diabetes can confuse events and even behave inappropriately with an increase in blood glucose, here prescribed antipsychotics are also not always necessary.

3 situation: the patient has been examined for a long time, the diagnosis is known, but the disease is progressing. Relatives begin to "look for a miracle": consult the patient with leading specialists, go to the main scientific centers, someone is looking for help abroad.

I have had a number of cases where patients have returned from the US, Europe, Israel, etc. with complaints that the prescription of drugs selected in Russia was refused, or that the treatment was simply ineffective, worsened. Here I would advise you to find a specialist you trust and coordinate your actions with him. Only together can we help sick people provide adequate assistance and, if not cured, then improve the quality of life as much as possible.

4 situation: terminally ill patient in the final stage. There is an opinion, or rather another myth, that one does not die from mental illness, however, mental illness is the same as somatic (i.e. body diseases), only the brain is sick, regardless there is a visible focus there (for example, as a result of a craniocerebral injury to the damaged part of the brain) or not. For example, severe progressive dementia, the final stage of alcoholism with multiple organ disorders, the terminal stage in malignant forms of schizophrenia, and others. Here it is necessary to decide individually, depending on the specific case.

There is an opinion, or rather another myth, that one does not die from mental illness, however, mental illness is the same as somatic (i.e. body diseases), only the brain is sick, regardless there is a visible focus there (for example, as a result of a craniocerebral injury to the damaged part of the brain) or not. For example, severe progressive dementia, the final stage of alcoholism with multiple organ disorders, the terminal stage in malignant forms of schizophrenia, and others. Here it is necessary to decide individually, depending on the specific case.

“If a person cannot be cured, this does not mean that he cannot be helped.”

If you are destined to die, it is easier to do this among loving relatives on your bed, even if a person does not understand anything and does not recognize anyone. But he FEELS the attitude towards him. How a small child feels the caress of his mother, smiles or cries when his mother is gone. You will say - there is no comparison, children are our future, and here is a dying person who does not understand anything. Yes, this is true, but we must understand that any of us can, God forbid, be in the place of this person ...

Yes, this is true, but we must understand that any of us can, God forbid, be in the place of this person ...

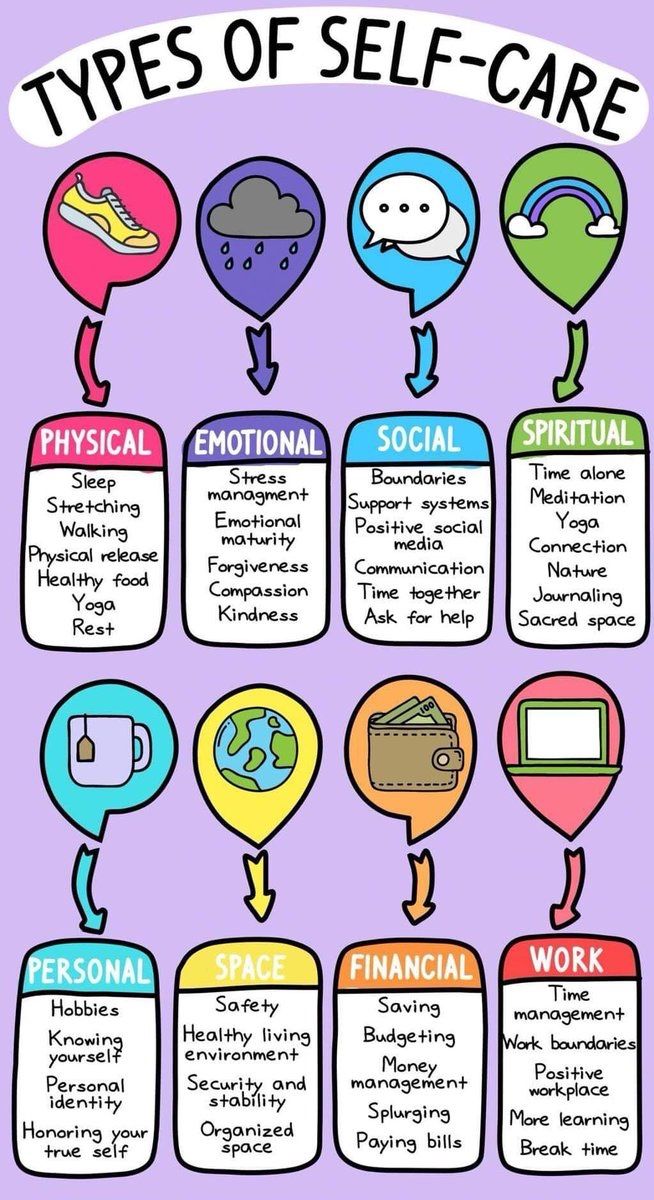

Nursing staff

Well, a few words about help for those who care for the sick. It is difficult to give specific recommendations here, only one thing is clear: you cannot take the position of either a rescuer or a victim, you just need to fulfill your human duty to the best of your ability and ability. Don't forget yourself.

Any person who lives with a sick person, and even more so caring for him, experiences enormous personal and emotional stress. Therefore, you should think about how you will cope with the disease in the future. By understanding your own emotions properly, you will be able to deal more effectively with both the patient's problems and your own problems. You may have to experience emotions such as grief, shame, anger, embarrassment, loneliness and others.

For some people who care for the sick, the family is the best helper, for others it brings only grief. It is important not to reject the help of other family members if they have enough time, and not to try to bear the sometimes difficult burden of caring for the sick alone.

It is important not to reject the help of other family members if they have enough time, and not to try to bear the sometimes difficult burden of caring for the sick alone.

If family members upset you with their unwillingness to help, or criticize your work because of the lack of information about this disorder, you can form a family council to discuss care problems. In particular, make a decision to involve an employee, at least for the period of time necessary for your rest and recuperation, and, if necessary, treatment.

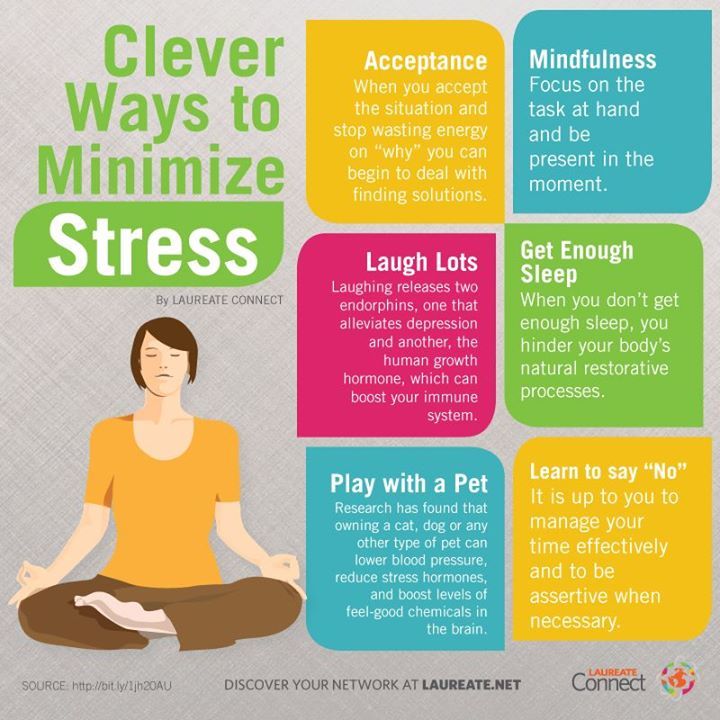

And the last. Don't keep problems to yourself. Feeling that your emotions are a natural reaction in your position, it will be easier for you to cope with your problems. Don't reject the help and support of others, even if you feel like you're making it difficult. Even psychotherapists themselves (seemingly knowing how to minimize stress as much as possible) often have their own psychotherapist, and it is bad for the doctor who neglects the help of his colleagues.

Principles for the protection of mentally ill persons and the improvement of mental health care - Conventions and agreements - Declarations, conventions, agreements and other legal materials

Adopted by General Assembly resolution 46/119 of 17 December 1991

Application

These Principles shall apply without discrimination of any kind on the basis of disability, race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nationality, ethnicity or social origin, legal or social status, age, property or estate status.

Definitions

In these Principles:

a ) the term "lawyer" means a legal or other qualified representative;

b ) the term "independent authority" means a competent and independent body established in accordance with domestic law;

c ) the term "psychiatric care" includes the analysis or diagnosis of a person's mental state, as well as treatment, care and rehabilitation in connection with a mental illness or suspected mental illness;

d ) the term "psychiatric institution" means any institution or any department of an institution whose primary function is the provision of mental health care;

e ) the term "psychiatric professional" means a physician, clinical psychologist, nurse, social worker, or other person who has been appropriately trained and has the necessary qualifications and specific skills to provide mental health care;

f ) the term "patient" means a person receiving mental health care, including persons admitted to a mental health facility;

g ) the term "personal representative" means a person who is required by law to represent the patient in any specified area or to exercise the specified rights on behalf of the patient, and includes the parent or legal guardian of a minor, unless national law provides otherwise.

;

h ) the term "supervisory authority" means the authority established in accordance with principle 17 to oversee the involuntary admission or detention of a patient in a psychiatric institution.

General limitation provision

The exercise of the rights set forth in these Principles may be subject only to such restrictions as are provided by law and are necessary to protect the health or safety of the person or others concerned, or to protect public safety, order, health or morals or fundamental rights and freedoms of others.

Principle 1

Fundamental freedoms and rights

1. All persons have the right to the best available mental health care, which is part of the health and welfare system.

2. All persons who are or are considered to be mentally ill shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person.

3. All persons who are or are considered to be mentally ill have the right to be protected from economic, sexual and other forms of exploitation, physical or other abuse and degrading treatment.

4. No discrimination is allowed on the basis of mental illness. "Discrimination" means any difference, exclusion or preference which has the effect of canceling or hindering the equal enjoyment of rights. Special measures taken solely for the purpose of protecting the rights or improving the situation of mentally ill eggs are not considered discriminatory. Discrimination does not include any distinction, exclusion or preference exercised in accordance with the provisions of these Principles and necessary to protect the human rights of a mentally ill person or other individuals.

5. Every person with a mental illness has the right to enjoy all civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights recognized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1 , the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 2 , the International civil and political rights 2 and other relevant documents such as the Declaration on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 3 and the Code of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment 4 .

6. Any decision that, by reason of his mental illness, a person is incompetent, and any decision that, as a result of such incapacity, a personal representative should be appointed, shall be taken only after a fair hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal established in accordance with with domestic law. The person whose legal capacity is the subject of the proceedings shall have the right to be represented by a lawyer. If the person whose legal capacity is the subject of the proceedings is unable to provide himself with such representation, the latter must be provided to that person free of charge if he does not have sufficient means to do so. Counsel must not, in the same proceedings, represent a psychiatric institution or its staff, and also must not represent a family member of the person whose legal capacity is the subject of the proceedings, unless the judicial authority is satisfied that there is no conflict of interest. Decisions relating to legal capacity and the need for a personal representative are subject to review at reasonable intervals in accordance with domestic law.![]() The person whose legal capacity is the subject of the proceedings, his personal representative, if any, and any other interested person shall have the right to appeal any such decision to a higher court.

The person whose legal capacity is the subject of the proceedings, his personal representative, if any, and any other interested person shall have the right to appeal any such decision to a higher court.

7. If a court or other competent judicial authority determines that a mentally ill person is unable to manage his affairs, measures shall be taken, to the extent necessary and taking into account the state of such a person, in order to ensure that his interests are protected.

Principle 2

Protection of minors

For the purposes of these Principles, and in the context of domestic law relating to the protection of minors, particular attention should be paid to the protection of the rights of minors, including, if necessary, the appointment of a personal representative who is not a family member.

Principle 3

Living in the community

Every person with a mental illness has the right, as far as possible, to live and work in the community.

Principle 4

Diagnosis of mental illness

1. A person is diagnosed as having a mental illness in accordance with internationally recognized medical standards.

2. A diagnosis of mental illness is never made on the basis of political, economic, social status, or membership of any cultural, racial, or religious group, or for any other reason not directly related to a mental health condition.

3. Family or work conflict, or inconsistency with the moral, social, cultural or political values or religious beliefs prevailing in the society in which the person lives, can never be a determining factor in the diagnosis of mental illness.

4. Information about past treatment or hospitalization as a patient cannot by itself justify a diagnosis of present or future mental illness.

5. No person or authority may declare or otherwise indicate that a person is suffering from a mental illness except for purposes directly related to the mental illness or the consequences of the mental illness.

Principle 5

Medical examination

No person may be compelled to undergo a medical examination to determine whether he or she suffers from a mental illness, except in accordance with a procedure provided for by national law.

Principle 6

Confidentiality

Information relating to all persons to whom these Principles apply shall be kept confidential.

Principle 7

Role of community and culture

1. Every patient has the right, to the extent possible, to treatment and care in the community in which he lives.

2. When treated in a psychiatric institution, the patient has the right, whenever possible, to be treated near his home or the home of his relatives or friends, and has the right to return to his community as soon as possible.

3. Every patient has the right to culturally appropriate treatment.

Principle 8

Standards of Care

1. Every patient has the right to such medical and social care as is necessary for the maintenance of his health and is entitled to care and treatment in accordance with the same standards as other patients.

2. Every patient shall be protected from harm to his health, including the unreasonable use of medicines, abuse by other patients, staff or others, and other acts that cause mental suffering or physical discomfort.

Principle 9

Treatment

1. Every patient has the right to be treated in the least restrictive setting and by the least restrictive or invasive methods appropriate to maintain his health and protect the physical safety of others.

2. Each patient's care and treatment is based on an individually developed plan that is discussed with the patient, regularly reviewed, modified as necessary, and provided by qualified medical personnel.

3. Psychiatric care is always provided in accordance with applicable ethical standards for professionals working in the field of psychiatry, including internationally recognized standards such as the Principles of Medical Ethics relating to the role of health professionals, especially physicians, in protecting prisoners or detainees from torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations 5 . Abuse of knowledge and skills in the field of psychiatry is not allowed

Abuse of knowledge and skills in the field of psychiatry is not allowed

4. The treatment of each patient should be aimed at maintaining and developing the autonomy of the individual.

Principle 10

Medications

1. Medications must best suit the need to maintain the patient's health, should only be administered to the patient for therapeutic or diagnostic purposes, and should never be used as a punishment or for the convenience of others. Except as provided in paragraph 15 of principle 11 below, mental health professionals will only use medications that are known or proven to be effective.

2. All medications are prescribed by legally authorized psychiatrists and recorded in the patient's medical records.

Principle 11

Consent to treatment

1. No treatment may be administered to a patient without their informed consent, except as provided in paragraphs 6,7,8,13 and 15 of this principle.

2. Informed consent is consent obtained freely, without threat or undue coercion, after adequate and clear information has been provided to the patient, in a form and language that the patient understands, about:

a ) provisional diagnosis,

b ) the purpose, methods, likely duration and expected results of the proposed treatment;

c ) alternative therapies, including less invasive ones;

d ) possible pain and discomfort, possible risks and side effects of the proposed treatment.

3. During the consent process, the patient may request the presence of a person or persons of their choice.

4. The patient has the right to refuse or stop treatment, except as provided in paragraphs 6, 7, 8, 13 and 15 of this principle. The consequences of refusing or stopping treatment should be explained to the patient.

5. The patient must not be asked or encouraged to waive the right to informed consent. If the patient expresses a desire to waive this right, it must be made clear to him that the treatment cannot be carried out without his informed consent.

6. Except as provided in paragraphs 7, 8, 12, 13, 14 and 15 of this principle, the proposed course of treatment may be administered to a patient without his informed consent, subject to the following conditions:

a ) the patient is currently involuntarily hospitalized;

b ) an independent authority, in possession of all relevant information, including the information referred to in paragraph 2 of this principle, is satisfied that the patient is not currently in a position to give or withhold informed consent to the proposed course of treatment or, if provided for by domestic law, that, having regard to the patient's own safety or the safety of others, the patient has unreasonably refused to give such consent;

c ) an independent authority has determined that the proposed course of treatment is in the best interest of the patient's health.

7. The provisions of paragraph 6 above do not apply to a patient who has a personal representative authorized by law to consent to treatment for the patient; however, except as provided in paragraphs 12, 13, 14 and 15 of this principle, treatment may be administered to such a patient without his informed consent if the personal representative, having received the information specified in paragraph 2 of this principle, consents on behalf of the patient.

8. Except as provided in paragraphs 12, 13, 14 and 15 of this principle, treatment may also be administered to any patient without their informed consent, if a qualified mental health professional authorized by law determines that administer this treatment urgently to prevent immediate or imminent harm to the patient or others. Such treatment shall not be extended beyond the period strictly necessary for that purpose.

9. Where any treatment is administered to a patient without the patient's informed consent, every effort should nevertheless be made to inform the patient of the nature of the treatment and of any possible alternative methods and, to the extent possible, involve the patient in the development of a course of treatment.

10. Any treatment is immediately recorded in the patient's medical record, indicating whether the treatment is compulsory or voluntary.

11. Physical restraint or involuntary isolation of a patient shall be used only in accordance with the official procedures of the psychiatric facility and only when it is the only means available to prevent immediate or imminent harm to the patient or others. They shall not be extended beyond the period strictly necessary for that purpose. All cases of physical restraint or involuntary isolation, the reasons for their application, their nature and duration should be recorded in the patient's medical history. A patient subjected to restraint or isolation must be kept in humane conditions, cared for, and carefully and constantly monitored by qualified medical personnel. The personal representative, if any and if appropriate, shall be promptly informed of any physical restraint or involuntary isolation of the patient.

12. Sterilization is never used as a treatment for mental illness.

13. A mentally ill person may be subjected to serious medical or surgical intervention only in cases where this is permitted by national law, when it is considered in the best interests of the patient's health, and when the patient gives informed consent, but in cases where the patient is not able to give informed consent, this intervention is prescribed only after an independent assessment.

14. Psychosurgery and other types of invasive and irreversible treatment of mental illness shall not, under any circumstances, be applied to a patient who has been involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric institution, and may be applied, within the limits permitted by domestic law, to any other patient only where the patient has given informed consent and an independent external body is satisfied that the patient's consent is indeed informed and that the treatment is in the best interests of the patient's health.

15. Clinical trials and experimental treatments shall not, under any circumstances, be used on any patient without their informed consent, unless clinical trials and experimental treatments may be used on a patient who is unable to give informed consent, only with the permission of a competent independent supervisory authority specially established for this purpose.

16. In the cases specified in paragraphs 6, 7, 8, 13, 14 and 15 of this principle, the patient or his personal representative, or any interested person has the right to appeal to a judicial or other independent authority regarding the application to the patient any treatment.

Principle 12

Notice of rights

1. The patient in a psychiatric facility shall, as soon as possible after admission, be informed, in a form and in a language that he understands, of all his rights under these Principles and under national law, and such information includes an explanation of these rights and how they can be exercised.

2. If and until the patient is unable to understand such information, the patient's rights will be communicated to the patient's personal representative, if any and as appropriate, and to the person or persons best able to represent the patient and willing to do so.

3. A patient with the necessary legal capacity has the right to appoint any person to be informed on his behalf, as well as a person to represent his interests before the administration of the institution.

Principle 13

Rights and conditions of detention in psychiatric institutions

1. Any patient held in a psychiatric institution has the right, in particular, to be fully respected:

a ) universal recognition as a subject of law;

b ) privacy rights;

c ) freedom of communication, which includes the freedom to communicate with others within the institution; the freedom to send and receive private communications that are not subject to censorship; freedom to receive in private a lawyer or personal representative and, at any reasonable time, other visitors; and freedom of access to postal and telephone services, as well as to newspapers, radio and television;

d ) freedom of religion or belief.

2. The environment and conditions of life in a psychiatric institution should, as far as possible, approximate those of the normal life of persons of the same age and, in particular, include:

a ) opportunities for leisure and recreation;

b ) educational opportunities;

s ) opportunities to buy or receive items necessary for daily life, leisure activities and communication;

d ) opportunities - and encouragement to use such opportunities - to involve the patient in activities appropriate to his social position and cultural characteristics, and to carry out appropriate vocational rehabilitation measures for his social reintegration.

These measures should include vocational guidance, vocational training and placement services so that patients can get or keep jobs in the community.

3. Under no circumstances may a patient be subjected to forced labor. To the extent compatible with the needs of the patient and with the requirements of the institution's administration, the patient should be able to choose the kind of work he wishes to do.

4. The work of a patient held in a psychiatric institution must not be exploited. Any such patient shall be entitled to receive for the work performed by him the same remuneration as, in accordance with national laws or customs, a person who is not a patient would receive for similar work. Any such patient shall in all cases be entitled to receive a fair share of any remuneration paid to a psychiatric institution for its work.

Principle 14

Resources for psychiatric institutions

1. A psychiatric institution must have access to the same resources as any other hospital, including but not limited to:

a ) a sufficient number of qualified medical personnel and other relevant professionals and adequate facilities to provide each patient with conditions of privacy and to carry out the necessary and active course of treatment;

b ) diagnostic and therapeutic equipment for the patient;

with ) proper maintenance by specialists;

d ) adequate, regular and comprehensive treatment, including the supply of medicines.

2. Every psychiatric facility should be inspected with sufficient regularity by the competent authorities to ensure that the conditions of patient care, treatment and care comply with these Principles.

Principle 15

Principles of hospitalization

1. When a person needs treatment in a psychiatric institution, every effort should be made to avoid involuntary hospitalization.

2. Access to a mental health facility should be regulated in the same way as access to any other health facility for any other illness.

3. Every non-involuntary hospitalized patient has the right to leave a psychiatric facility at any time, unless the criteria for involuntary detention provided for in principle 16 below apply, and he must be informed of this right.

Principle 16

Involuntary hospitalization

1. Any person may be admitted to a psychiatric institution as an involuntary patient or already admitted as a voluntary patient may be involuntarily detained as a patient in a psychiatric institution if and only if an authorized person for this goals under the law a qualified mental health professional will determine, in accordance with principle 4 above, that the person is suffering from a mental illness and will determine:

a ) that there is a serious risk of imminent or imminent harm to that person or others as a result of this mental illness; or

b ) that in the case of a person whose mental illness is severe and whose mental capacity is impaired, refusal to hospitalize or keep the person in a psychiatric facility could result in a serious deterioration in his health or make it impossible to apply appropriate treatment that can be carried out subject to admission to a psychiatric institution in accordance with the principle of the least restrictive alternative.

In the case of subparagraph b), it is necessary, if possible, to consult with a second such specialist working in the field of psychiatry. In the case of such consultation, hospitalization in a psychiatric institution or involuntary detention may take place only with the consent of a second specialist working in the field of psychiatry.

2. Involuntary admission or detention in a psychiatric institution shall be carried out initially for a short period determined by national law for the purpose of observation and pre-treatment, pending consideration of the admission or detention of the patient in a psychiatric institution by a supervisory authority. The reasons for hospitalization or detention are immediately reported to the patient; the fact of hospitalization or detention and their reasons shall also be reported promptly and in detail to the supervisory authority, the patient's personal representative, if any, and, if the patient does not object, to the patient's family.

3. A psychiatric facility may only accept involuntary patients if the facility is designated for that purpose by a competent authority established by national law.

Principle 17

Supervisory Authority

1. The Supervisory Authority is a judicial or other independent and impartial body established under national law and functioning in accordance with procedures established by national law. In preparing his decisions, he shall be assisted by one or more qualified and independent professionals working in the field of psychiatry and take their advice into account.

2. Consistent with principle 16, paragraph 2, above, the initial review by a supervisory authority of a decision to admit or hold a patient in a psychiatric facility shall take place as soon as possible after such a decision is made and shall be carried out in accordance with simplified and expedited procedures, provided for in national law.

3. The oversight body reviews cases of involuntary hospitalization periodically at reasonable intervals determined by national law.

4. A compulsorily hospitalized patient may, at reasonable intervals as determined by national law, apply to a supervisory authority for discharge or to be granted the status of a voluntary hospitalized patient.

5. At each review, the supervisory authority should consider whether the criteria for involuntary admission set out in principle 16, paragraph 1, above are still satisfied and, if not, the patient should be discharged as an involuntary hospitalization.

6. If at any time the psychiatric specialist in charge of the case is satisfied that the conditions of the person's detention as an involuntary hospitalized patient are no longer satisfied, that specialist shall order the person's release as a patient, compulsorily hospitalized.

7. The patient, or his personal representative, or any interested person has the right to appeal to a higher court the decision to hospitalize the patient or keep him in a psychiatric institution.

Principle 18

Procedural safeguards

1. The patient has the right to choose and appoint an attorney to represent the patient as such, including representation in any complaint or appeal process. If the patient does not provide such services on his own, the lawyer is provided to the patient free of charge insofar as the patient does not have sufficient funds to pay for his services.

The patient has the right to choose and appoint an attorney to represent the patient as such, including representation in any complaint or appeal process. If the patient does not provide such services on his own, the lawyer is provided to the patient free of charge insofar as the patient does not have sufficient funds to pay for his services.

2. The patient also has the right, if necessary, to use the services of an interpreter. When such services are needed and the patient cannot provide them, they are provided free of charge to the patient insofar as the patient does not have sufficient funds to pay for these services.

3. The patient and the patient's advocate may request and present at any hearing an independent psychiatric report and any other opinions, as well as written and oral evidence, that is relevant and admissible.

4. Copies of the patient's medical records and any reports and documents that are required to be produced are served on the patient or the patient's advocate, except in exceptional cases where it is determined that disclosing specific information to the patient would cause serious harm to the patient's health or endanger the safety of others. In accordance with national law, any document not presented to the patient should, when possible in confidence, be served on the patient's personal representative and advocate. In the event that any part of any document is not presented to the patient, the patient or the patient's advocate, if any, is notified of the failure and the reasons for it, and the decision may be subject to judicial review.

In accordance with national law, any document not presented to the patient should, when possible in confidence, be served on the patient's personal representative and advocate. In the event that any part of any document is not presented to the patient, the patient or the patient's advocate, if any, is notified of the failure and the reasons for it, and the decision may be subject to judicial review.

5. The patient and the patient's personal representative and advocate have the right to attend, participate in, and be heard at any hearing.

6. If a patient, or a personal representative, or an attorney for a patient, requests that a certain person be present at the hearing, that person is admitted to the hearing, unless it is determined that his presence would cause serious harm to the patient's health or put him under threat to the safety of others.

7. Any decision as to whether a hearing, or part of it, will be open or closed and disclosed to the public must be made in the light of the wishes of the patient, the need to respect the right of the patient and others to privacy, and the need to prevent serious harm to the patient's health or risk to the safety of others.

8. The decision made at the end of the hearing and the reasons for it are set out in writing. Copies are issued to the patient and the patient's personal representative and advocate. In deciding whether the decision will be published in whole or in part, full consideration should be given to the wishes of the patient, the need to respect the privacy of the patient and the privacy of others, the public interest in the open administration of justice, and the need to prevent serious harm to the patient's health or safety risk. other persons.

Principle 19

Access to information

1. A patient (a term which in this principle also includes former patients) has the right to access information relating to him/her in the medical history maintained by a psychiatric institution. This right may be restricted in order to prevent serious harm to the health of the patient and risk to the safety of others. In accordance with national law, any such information not provided to the patient should, when possible in confidence, be communicated to the patient's personal representative and counsel. In the event that any such information is not disclosed to the patient, the patient or the patient's advocate, if any, is notified of the non-disclosure of this information and the reasons for it, and this decision is subject to judicial review.

In the event that any such information is not disclosed to the patient, the patient or the patient's advocate, if any, is notified of the non-disclosure of this information and the reasons for it, and this decision is subject to judicial review.

2. Any written comments by the patient or the patient's personal representative or advocate may be included in the patient's medical history upon request.

Principle 20

Criminal offenders

1. This principle applies to persons who are serving a term of imprisonment for criminal offenses or to persons who are otherwise detained in the course of proceedings or investigations brought against them for a criminal offense and who are found to be suffering from a mental illness or are suspected to be suffering from such an illness.

2. These persons should receive the best possible mental health care as provided for in principle 1 above. These Principles apply to them to the fullest extent possible, with only such limited modifications and exceptions as are necessary in the circumstances. No such modification or exclusion shall prejudice the rights of these persons under the instruments listed in paragraph 5 of principle 1 above.

No such modification or exclusion shall prejudice the rights of these persons under the instruments listed in paragraph 5 of principle 1 above.

3. Provisions of domestic law may authorize a court or other competent authority, on the basis of a competent and independent medical opinion, to decide on the placement of such persons in a psychiatric institution.

4. The treatment of persons diagnosed with mental illness must, in all circumstances, be consistent with principle 11 above.

Principle 21

Complaints

Every patient and former patient has the right to file a complaint in accordance with the procedures set out in national law.

Principle 22

Oversight and remedies

States shall ensure that appropriate mechanisms are in place to promote compliance with these Principles for the inspection of psychiatric facilities, for the presentation, investigation and resolution of complaints, and for the initiation of appropriate disciplinary or judicial proceedings in cases of breach of duty or patient rights.