How to cope with dissociation

How Do I Cope with ‘Checking Out’ from Reality?

How do you stay mentally-healthy when you’re alone and dissociating?

Share on PinterestDesign by Alexis Lira | Illustration by Ruth BasagoitiaHi Sam, I’ve been working with a new therapist to deal with some traumatic events that happened when I was a teenager. We talked a little about dissociation, and how I tend to “check out” emotionally when I’m triggered.

I guess what I’m struggling with most is how to stay present when I’m alone. It’s so much easier to disconnect when I’m by myself and in my own little world. How do you stay present when there’s no one there to snap you out of it?

Wait a minute!

You said that there’s no one to help you “snap out of” dissociating, but I want to remind you (gently!) that that’s not true. You have yourself! And I know that doesn’t always seem like enough, but with practice, you might find that you have more coping tools at your disposal than you realize.

Before we get into what that looks like, though, I want to establish what “dissociation” means so we’re on the same page. I’m not sure how much your therapist filled you in, but since it’s a tricky concept, let’s break it down in simple terms.

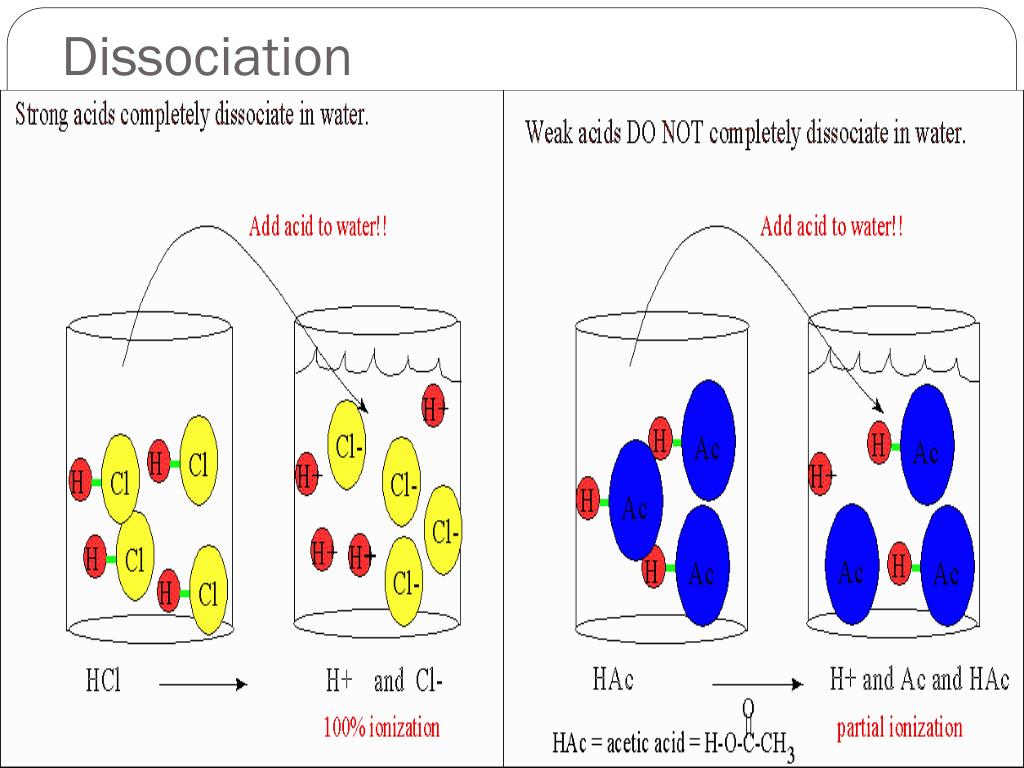

Dissociation describes a type of psychological disconnect — so you were right on the money when you described it as “checking out”

But it’s more than just daydreaming! Dissociation can impact your experience of identity, memory, and consciousness, as well as affect your awareness of yourself and your surroundings.

Interestingly, it shows up in different ways for different people. Not knowing about your particular symptoms, I’m going to list out a few different “flavors” of dissociation.

Maybe you’ll recognize yourself in some of the following:

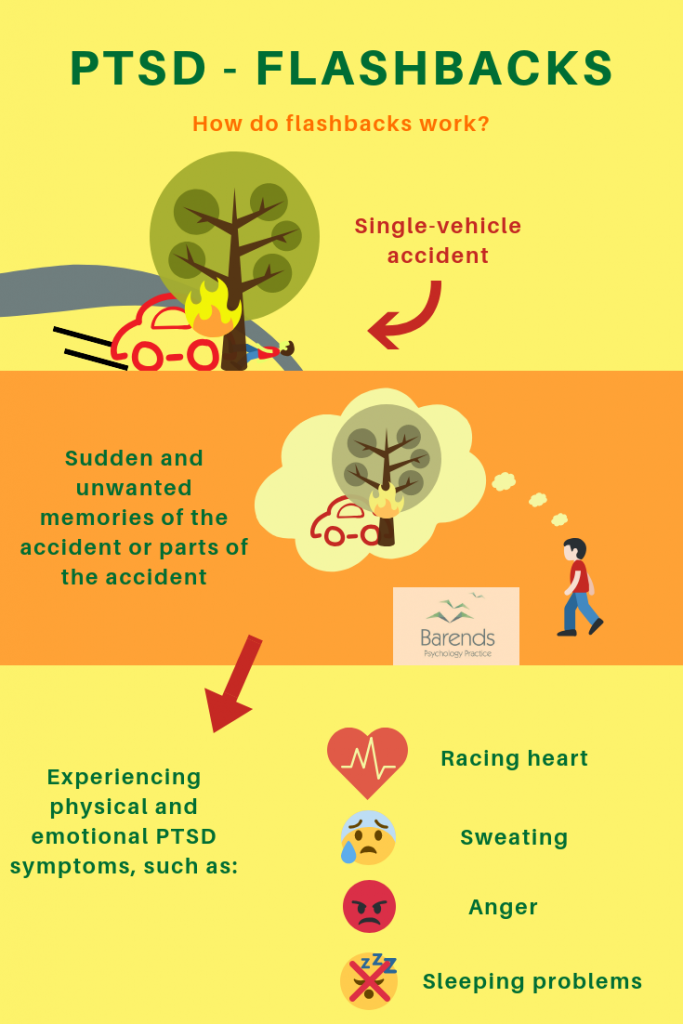

- flashbacks (re-experiencing a past moment,

particularly a traumatic one) - losing touch with what’s going on around you

(like spacing out) - being unable to remember things (or your mind

“going blank”) - depersonalization (an out-of-body experience, as

though you’re watching yourself from a distance) - derealization (where things feel unreal, like

you’re in a dream or a movie)

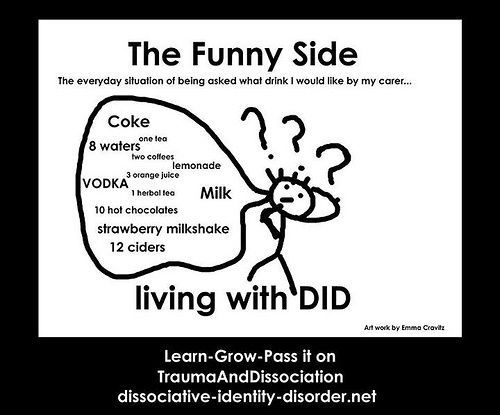

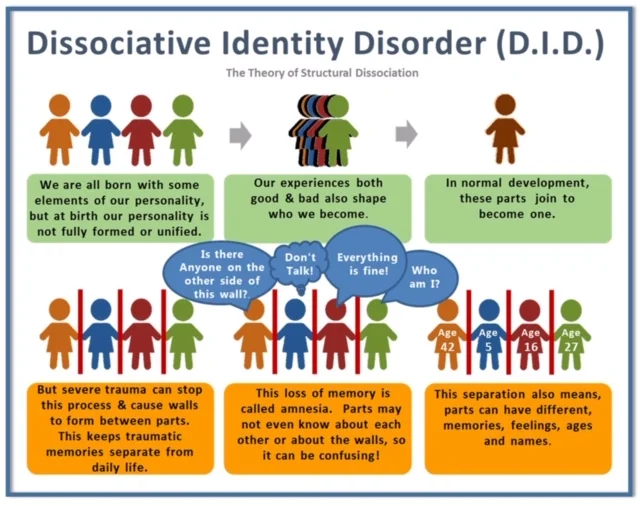

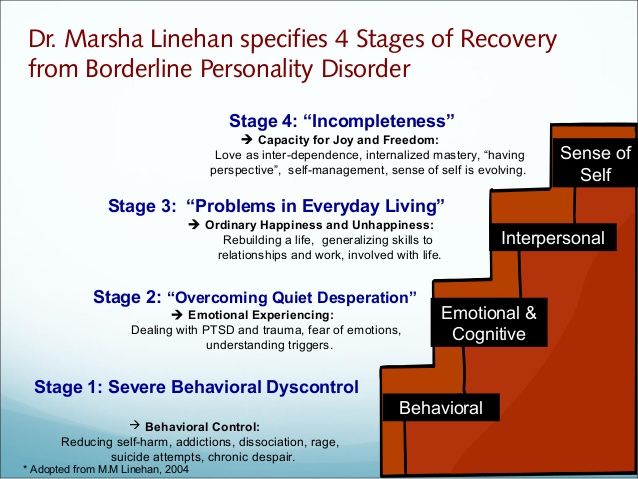

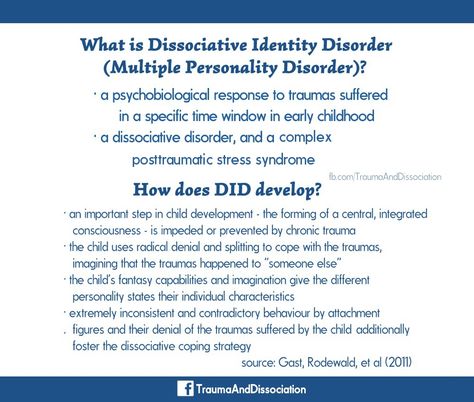

This is different from dissociative identity disorder (DID), which describes a particular set of symptoms that include dissociation but also results in a fragmenting of your identity (put another way, your identity “splits” into what most people refer to as “multiple personalities”).

Most people think dissociation is specific to people with DID, but that isn’t the case! As a symptom, it can show up in a number of mental health conditions, including depression and complex PTSD.

Of course, you’ll want to talk to a healthcare provider to pinpoint exactly why you’re experiencing this (but it sounds like your therapist is on the case, so good on you!).

I’m glad you asked — here are some of my tried and true recommendations:

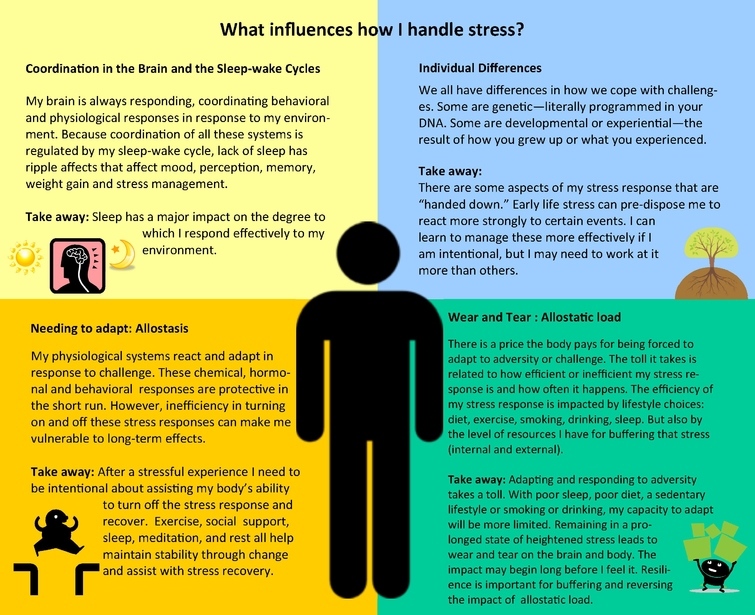

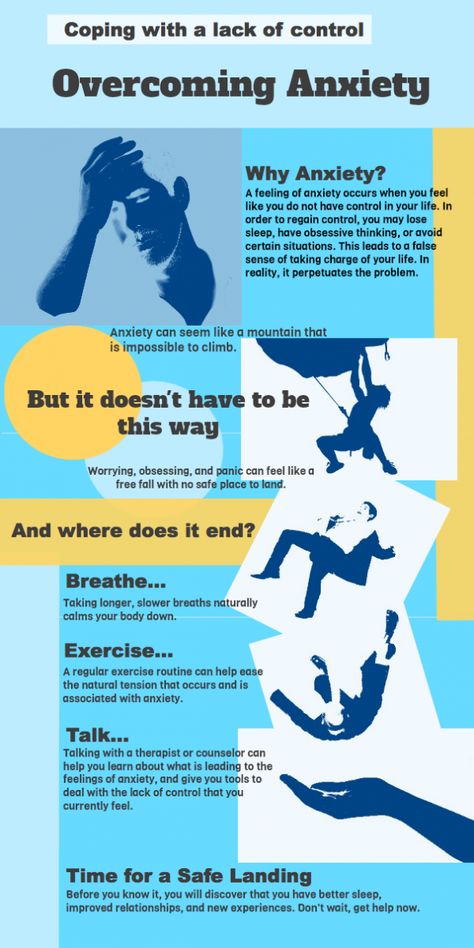

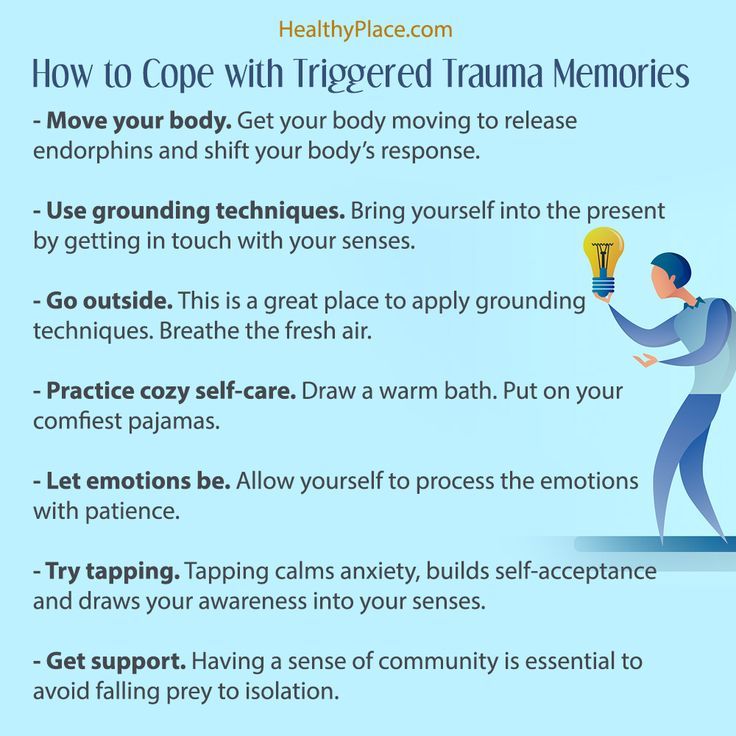

1. Learn to breathe

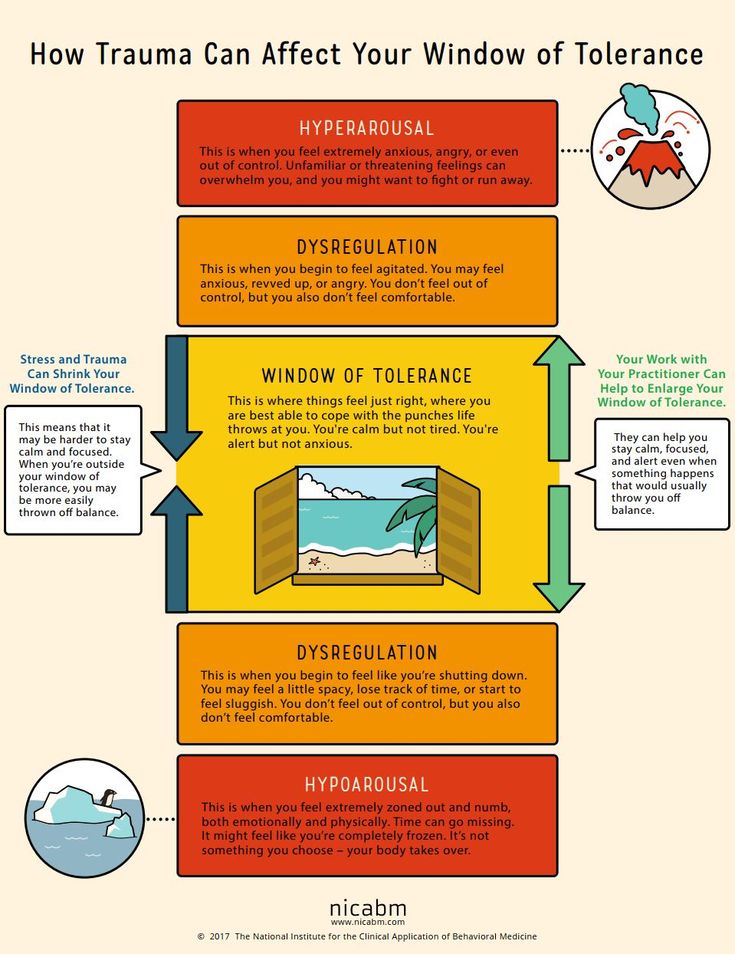

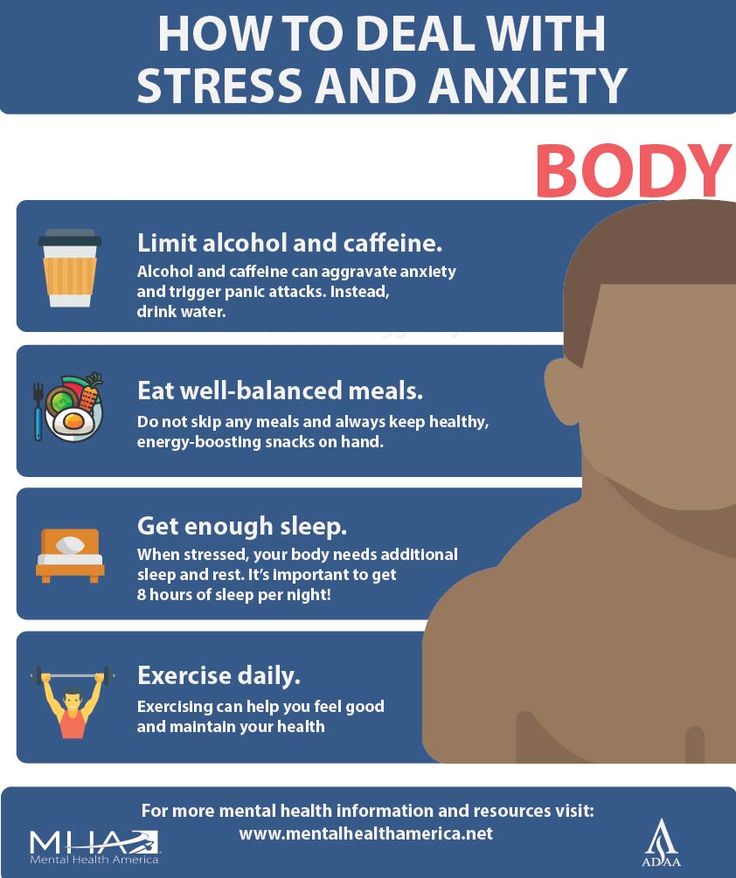

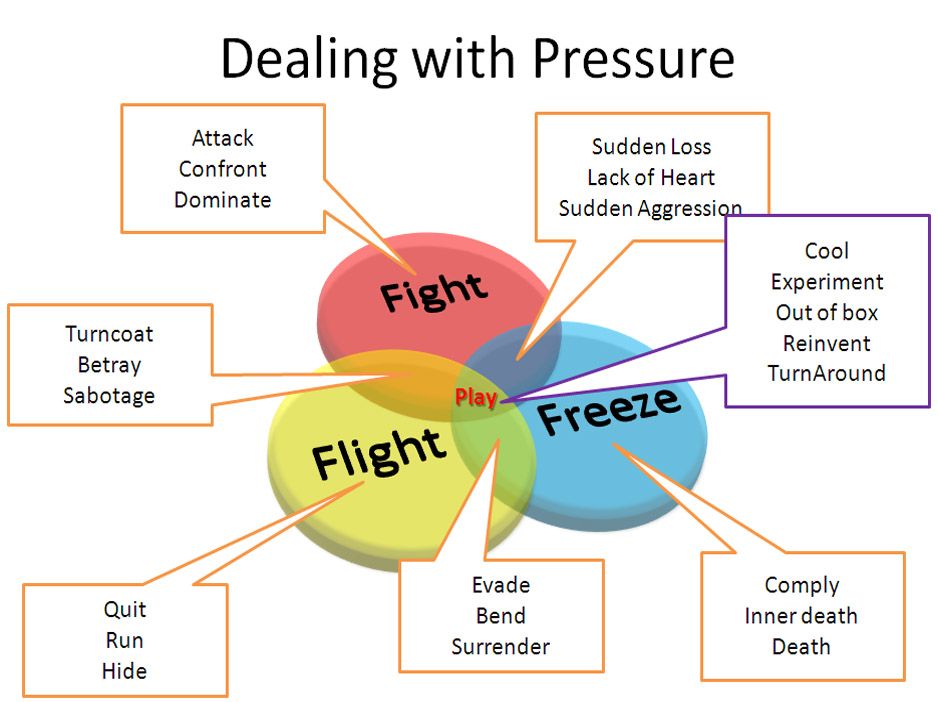

Dissociation is often triggered by the fight-or-flight response. In order to counteract that, it’s important to know how to self-soothe through breathing.

I recommend learning the box breathing technique, which has been shown to regulate and calm your autonomic nervous system (ANS). This is a way to signal to your body and brain that you’re safe!

2. Try some grounding movements

I hate recommending yoga for people because it can come across as trivializing.

But in this particular instance, body work is so important when we’re talking about dissociation! In order to stay grounded we need to be present in our bodies.

Restorative yoga is my favorite way to get back into my body. It’s a form of gentler, slower-paced yoga that allows me to stretch out, focus on my breathing, and untense my muscles.

The app Down Dog is great if you’re looking to try it out. I take classes in Yin Yoga and they’ve helped immensely, too.

If you’re looking for some simple yoga poses to self-soothe, this article breaks down different poses and shows you how to do them!

3. Find safer ways to check out

Sometimes you do need to turn off your brain for a while. Is there a safer way to do so, though? Is there a television show you can watch, for example? I like to make a cup of tea or hot cocoa and watch Bob Ross paint his “happy trees” on Netflix.

Treat yourself like you would a very freaked out friend. I always tell folks to treat dissociative episodes like you would a panic attack, because they stem from a lot of the same “fight or flight” mechanisms.

The weird thing about dissociation is that you might not feel much of anything at all — but that’s your brain doing its best to protect you.

If it helps to think about it this way, pretend it’s an anxiety attack (except someone took the remote and pressed “mute”), and create a safe space accordingly.

4. Hack your house

I have complex PTSD and having sensory items around my apartment has been a lifesaver.

For example, by my nightstand, I keep lavender essential oils to spray on my pillow for when I lay down to do deep breathing.

I keep soft blankets on every couch, an ice tray in the freezer (squeezing ice cubes helps snap me out of my episodes), lollipops to focus on tasting something, citrus body wash to wake me up a little in the shower, and more.

You can keep all these items in a “rescue box” for safe keeping, or keep them within reach in different areas of your home. The key is to make sure they engage the senses!

5. Build out a support team

This includes clinicians (like a therapist and psychiatrist), but also loved ones that you can call if you need someone to talk to. I like to keep a list of three to five people I can call on an index card and I “favorite” them in my phone contacts for easy access.

I like to keep a list of three to five people I can call on an index card and I “favorite” them in my phone contacts for easy access.

If you don’t have folks around you who “get it,” I’ve connected with a lot of lovely and supportive people in PTSD support groups. Are there resources in your community that can help you build up that safety net?

6. Keep a journal and start identifying your triggers

Dissociation happens for a reason. You may not know what that reason is right now, and that’s okay! But if it’s having an impact on your life, it’s crucial to make sure you’re working with a mental health professional to learn better coping tools and identify your triggers.

Keeping a journal can be helpful for illuminating what some of your triggers might be.

When you have a dissociative episode, take some time to retrace your steps and look at the moments leading up to it. This can be crucial to better understanding how to manage dissociation.

Because dissociation can impact your memory, writing it down also ensures that when you meet with your therapist you’ll have reference points that you can go back to, to build a clearer picture of what’s been going on for you.

If you aren’t sure where to start, this No BS Guide to Organizing Your Feelings can give you a template to work with!

7. Get an emotional support animal

I’m not saying run to the nearest animal shelter and bring home a puppy — because bringing a furry friend home can be a trigger in itself (potty training a pup is a nightmare that will likely have the opposite effect on your mental health).

I can tell you from experience, though, that my cat Pancake has completely changed my life. He’s an older cat that’s incredibly cuddly, intuitive, and loves being hugged — and he’s my registered ESA for a reason.

Any time I’m having a mental health issue, you’ll find him perched on my chest, purring away until my breathing slows down.

So when I tell you to get a support animal, it should be something you put a lot of thought into. Consider how much responsibility you can take on, the personality of the critter, the space you have available, and contact a shelter to see if you can get some help finding your perfect match.

You might be thinking, “Okay, Sam, but WHY would our brains do this dissociation thing when it’s so unhelpful in the first place?”

That’s a valid question. The answer? It probably was helpful at one time. It just isn’t anymore.

That’s because dissociation, at its core, is a protective response to trauma.

It allows our brains to take a break from something it perceives as threatening. It’s probably a safe bet that, at some point or another, dissociation helped you deal with some very tough stuff in life.

But it’s not helping you now, hence the predicament you’re in. That’s because it’s not a coping mechanism with a whole lot of usefulness in the long-term.

While it can (and often does) serve us when we’re in immediate danger, it can begin to interfere with our lives when we’re no longer in a threatening situation.

If it’s helpful, just picture your brain as an overcautious lifeguard who blows their whistle literally anytime you’re close to water — even if the pool is empty, or it’s just a kiddie pool in someone’s backyard… or it’s your kitchen sink.

Those traumatic events have (hopefully) passed, but your body is still reacting as though they haven’t! The dissociation, in that way, has sort of overstayed its welcome.

So our goal here is to get that neurotic lifeguard to chill the eff out, and to retrain them to recognize what situations are and aren’t unsafe.

Just try to remember this: Your brain is doing the very best it can to keep you safe.

Dissociation is not something to be ashamed of, and it doesn’t mean that you’re “broken.” In fact, it indicates that your brain is working really, really hard to take good care of you!

Now you have the opportunity to learn some new coping methods, and with time, your brain won’t need to rely on the old mechanisms that aren’t serving you now.

I know it can be scary to experience dissociation. But the good news is, you aren’t powerless. The brain is an amazingly adaptable organ — and each time you discover a new way of creating a sense of safety for yourself, your brain is taking notes.

Pass along my thanks to that amazing brain of yours, by the way! I’m really glad you’re still here.

Sam

Strategies to Reduce Dissociation - Staying Present

Back to Blog

Ever unintentionally ‘tuned out’ in the middle of a conversation? Or perhaps feel that sometimes your mind has been on autopilot? As strange, and sometimes annoying, these kinds of ‘spacing out’ moments are, they are considered common, everyday levels of absent mindedness.

But what if you couldn’t recall anything you said or did in the last three hours? Or found yourself wandering in a new place with no idea how you got there? What if your waking life felt surreal, like you are watching it play out in front of you? These, sometimes frightening disturbances to time and reality, are the concerns of a person with a potential dissociative disorder.

Dissociation generally means that you are disconnected from the present moment. ‘Dissociation’ in psychological literature is characterized by a disruption in the usually integrated functions of consciousness, memory, identity, or perception of the environment.

‘Dissociation’ in psychological literature is characterized by a disruption in the usually integrated functions of consciousness, memory, identity, or perception of the environment.

For people with a dissociative condition, their experiences include:

- Inability to remember what they did in a period of time (from minutes to days)

- Unusual emotional and physical numbness

- Told by others that you go into a ‘trance-like’ state

- Out of body experiences like watching self from the outside

- Disconnection from physical surroundings

- A sense that the world does not feel ‘real’ (i.e. like a dream or being in a movie)

- Confused sense of self (i.e. identity)

- Potential safety concerns; i.e. unintentional dissociation while driving a car or cooking

- Not recognising yourself in the mirror

Many people who dissociate may not know when they are doing it, it is often brought to their attention from others who see them do it. Dissociative symptoms can be distressing and debilitating to the sufferer, and can all significantly impact on an individual’s wellbeing and ability to cope and function throughout daily life.

Dissociative symptoms can be distressing and debilitating to the sufferer, and can all significantly impact on an individual’s wellbeing and ability to cope and function throughout daily life.

There are 6 known different types of dissociation classified in the psychological manual of disorders. The most extreme dissociative disorder case is known as ‘dissociative identity disorder’ (formerly multiple personality disorder), with symptoms including the presence of two or more distinct personality states or ‘alters’, as portrayed in Hollywood movies ‘Split’ and Fight club’.

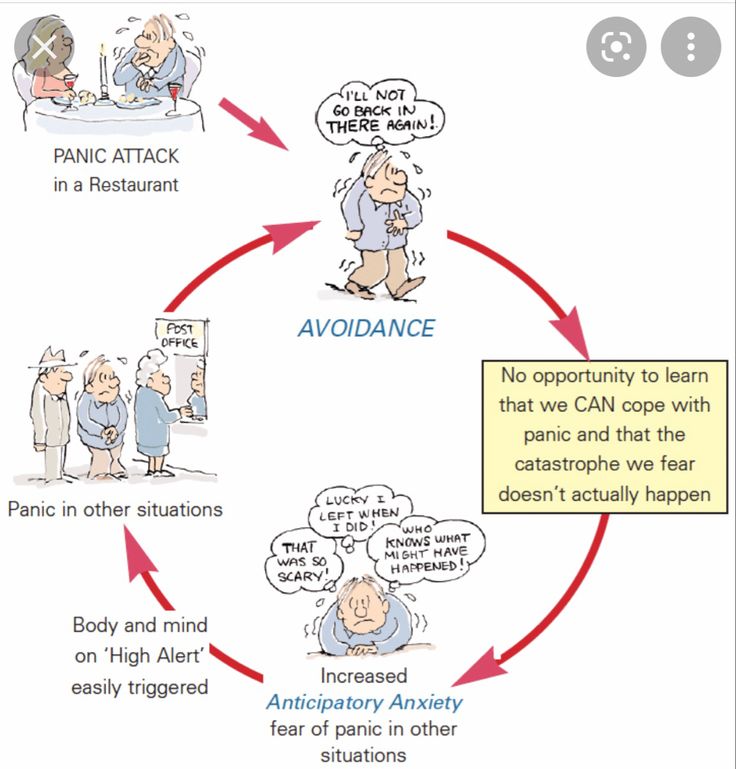

Dissociation is generally linked back to a particular traumatic cause or life event i.e. sexual abuse and/or violence. Dissociation can also be triggered by external stress factors (i.e. a break-up or losing your job.) and internal stressors such as an intrusive traumatic memory. When dissociation is connected to trauma memories or reminders, it is considered an avoidance coping mechanism. For example, a child may have been a regular victim of abuse where they used ‘spacing out’ as a necessity to cope with daily life. The purpose of dissociation as a coping strategy, is to avoid feelings of intense guilt, shame, helplessness, fear or pain. Avoidance of these feelings and adequate processing of traumatic experiences (especially ones that involve coercion and emotional and physical abuse) may cause an individual to question their self-perception and self-esteem.

The purpose of dissociation as a coping strategy, is to avoid feelings of intense guilt, shame, helplessness, fear or pain. Avoidance of these feelings and adequate processing of traumatic experiences (especially ones that involve coercion and emotional and physical abuse) may cause an individual to question their self-perception and self-esteem.

Dissociation becomes a significant challenge to a person when there is no longer a real threat present making it uncertain as to when another dissociative episode may occur.

The good news is that people with dissociative conditions at many different levels can live a full safe and happy life. Psychological support is essential for effective guidance on how to reduce dissociative symptoms and regain a stronger sense of self awareness.

There are also ways to reduce spacing out and help yourself to be more mindful in general, to allow yourself live more in the present moment.

Steps to reduce dissociation and increase self-awareness.

Mindfulness Practice.

- Use your Five Senses. Name 5 things you see, 4 things you feel, 3 things you hear, 2 things you smell and 1 thing you taste. This can be done anywhere.

- Mindfulness walk. Notice how your body feels with each step, take your time paying close attention to physical sensations throughout your body.

- Slow breathing. Close your eyes and breathe in and out, slowly counting up and down from 10. This will help you to relax and aids clearer processing of thoughts and emotions.

- Write in a daily journal. Recall your day in detail. Make a point of noticing any dissociations that may have occurred and try to recall any thoughts or emotions before, during, or after it.

The goal is not to clear your mind or stop thinking, but to be more aware of your thoughts and feelings rather than getting lost in them.

Think that you have dissociation symptoms, and want to talk to someone about it? New View Psychology are available for support on 1300 830 687.

Written by Sarah Van Der Pluym.

References:

Image source; https://i.ytimg.com/vi/Ya2_WNkA_0o/maxresdefault.jpg

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC.

Dell, P. F., & O’Neil, J. A. (2009). Dissociation and the dissociative disorders: DSM-V and beyond. New York, NY: Routledge.

Posted in Counselling← Previous Post Next Post →

Sign up below for regular emails with information, advice and support for you and your loved ones.

After Trauma: 5 Exercises to Get Back to Yourself

23,425

Know YourselfListen to Your BodyPractices how to

Trauma specialist Peter Levine has been researching PTSD for over 30 years. He is convinced that psychological trauma is the result of an incomplete instinctive reaction of the body to a traumatic event. The completion of this reaction will lead the affected person to complete healing. Therefore, the main emphasis in the therapy of psychological trauma, Peter Levin makes what happens to the body. nine0003

1. Pulsating shower

Take a light, 10-minute pulsating shower every day: run cool or lukewarm water and expose your entire body to its jets. Concentrate your mind completely on the part of the body where the water is falling rhythmically at the moment. Turn around, prompting your consciousness to move from one part of your body to another. Press the back of your hands against the shower head; then the palms and wrists; then - the face on both sides, shoulders, armpits and so on. Try to include all parts of the body in this process. nine0003

Pay attention to the sensations in each area, even if you don't feel anything or if you feel numbness or pain. At the same time, say: “This is my head, neck”, “I am glad that you are back.” A quick and light slap on various parts of the body will evoke a similar feeling of awakening. This simple exercise will help restore the connection between the body, mind and spirit, which is often broken after psychological trauma.

2. Feeling through touch

Wherever you are, while reading these lines, make yourself as comfortable as possible. Feel how your body is in contact with the surface that supports you. Feel your skin, note the sensations in contact with clothing. Feel what is under the skin - what reactions of the body do you notice? nine0003

Memorize them and think calmly: how exactly do you determine that you feel comfortable? What physical sensations make up the feeling of comfort that is born in your mind? What thoughts help you become more aware of the physical sensation - are you more comfortable or vice versa? Do they change over time? Sit down for a moment and enjoy the comfort that bodily sensations give you.

3. Feel the dissociation

A traumatized person is usually dissociated. Dissociation is a kind of psychological defense. In a moment of strong negative experience, we begin to perceive what is happening to us from the outside, as if we are leaving our own body. This mechanism protects against unbearable, too heavy emotions. A dissociative episode after a trauma is usually referred to as, "Like it wasn't me." nine0003

This mechanism protects against unbearable, too heavy emotions. A dissociative episode after a trauma is usually referred to as, "Like it wasn't me." nine0003

To understand what dissociation is and how it feels, sit back in your chair and imagine yourself lying on a raft floating on a lake. Feel yourself floating and then allow yourself to gently float out of your body. Rise up to the sky, slowly, like a balloon taking off, and look at yourself sitting below.

What is this experience like? What happens when you try to feel your body? Go from your own body to this feeling of flying a few more times to get a better feel for the dissociation. nine0003

4. Dissociation test

Sit comfortably in a chair that supports your body. Think of a place where you would really like to go on vacation - a long, leisurely and carefree vacation. Go through the memory of wonderful places and try to choose the best. Now mentally go there and do whatever your heart desires.

Right before you are ready to go home, answer the question: where are you?

Most likely you will name your favorite vacation spot. It is unlikely that you will answer that you are now in your own body. When you are not in your body, you are dissociated. nine0003

It is unlikely that you will answer that you are now in your own body. When you are not in your body, you are dissociated. nine0003

5. Working with photos

Open your family photo album and select 2-3 photos from your travels or your childhood. They should be well-known to you people or familiar places.

Look at the first photo. What emotions does it awaken in you? Whatever your reaction is, just note it. Is she strong or moderate? How do you know what she is? If you can answer this question based on your bodily sensations, then you are already learning to use the hidden physiological basis of your emotions. nine0003

Now ask yourself: “How do I understand that my emotional reaction to this image is exactly this?” Do you feel tense or energized? If so, how strong are they and where are they located? Pay attention to your breathing, your heartbeat, and how tension is distributed throughout your body. How does your skin feel? Body as a whole? Does your feeling get stronger? Where exactly does it start growing? Be as precise as possible. How do you know that this is your reaction? nine0003

How do you know that this is your reaction? nine0003

Constantly remind yourself to come from the body and not from the mind - perceive everything as sensations of the body, not as thoughts or emotions. You just need to describe your feelings. Take the next photo and repeat the exercise.

About the author: Peter Levine is an American psychotherapist and author of Waking the Tiger. Healing trauma."

Text:Silva StepanyanPhoto Source:Getty Images

New on the site0003

“During quarrels, my husband sends me obscenities in front of the children and says that it will always be like this”

“Girl does not want to do with me what she did with her ex”

Laws of arousal: is it possible to tame sexuality - the answer of a psychoanalyst

5 books about cheating: a literary critic's choice

Happy marriage: how to improve relationships in a couple

Quiz: What do you consider true love?

“I didn’t have time to confess my feelings to the guy - he passed away a month ago”

Psychological counseling and psychotherapy - "Perception"

In this article I want to talk about dissociation, its frequency and intensity of use as a protective mechanism in human life, about the facets of healthy and pathological, and how speech can tell about it.

The term "dissociation" was proposed at the end of the 19th century by the French psychologist and physician P. Janet, who noticed that a complex of ideas can split off from the main personality and exist independently and outside consciousness, but can be returned to consciousness with the help of hypnosis. nine0048

Foreword

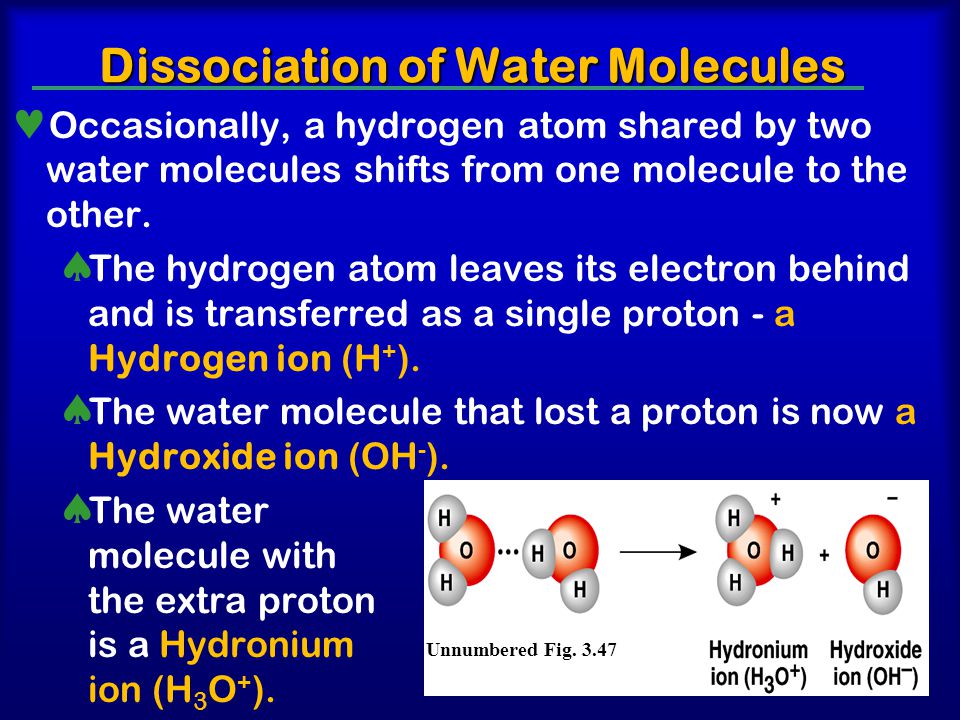

In psychiatry there is a group of diseases called "dissociative disorders". Compared to paranoia or schizophrenia, it probably doesn’t sound very scary, but this is a fairly serious diagnosis. What is it? Dissociation in Latin means "disintegration". With this disease, there is a violation of mental functions, such as memory, consciousness, a sense of personal identity. These mental functions separate from the integral stream of consciousness and become independent. Thus, the integrity of the individual is violated. nine0003

Dissociation in life

After I deliberately scared you, I want to talk about the dissociations that are present in the lives of mentally healthy people, or, in the language of psychology, neurotics, which are the majority of people on the planet. I must say that dissociation is a protective mechanism of the psyche, which turns on when a person cannot cope with the situation in which he is. This may be a long-term traumatic situation or a shock trauma that a person cannot accept and integrate into his own psyche. The most traumatic and having a strong impact on human development Situations , certainly occur in early childhood, when a child cannot cope with severe stress on his own and he does not have proper support from his parents, but such situations can also arise in adulthood. These are local stressful situations or long-term traumatic situations from which a person more often does not want than cannot get out because of secondary benefits.

I must say that dissociation is a protective mechanism of the psyche, which turns on when a person cannot cope with the situation in which he is. This may be a long-term traumatic situation or a shock trauma that a person cannot accept and integrate into his own psyche. The most traumatic and having a strong impact on human development Situations , certainly occur in early childhood, when a child cannot cope with severe stress on his own and he does not have proper support from his parents, but such situations can also arise in adulthood. These are local stressful situations or long-term traumatic situations from which a person more often does not want than cannot get out because of secondary benefits.

If the human psyche cannot cope, then the dissociation mechanism is activated. A person can fall into a trance state, can create in his head another alternative situation that is more acceptable to him, put his ideas, thoughts, emotions there, and experience them instead of reality. Naturally, this process occurs unconsciously. In very strong stressful situations (such as various disasters, the death of loved ones, etc.), psychogenic amnesia may occur - in simple terms, a person does not want to realize or admit what happened and may not remember an event or a whole part of life. nine0089 There are many variants of manifestation of dissociation, and even in the most difficult cases, its manifestation cannot always be unambiguously called a mental illness. Most people are mentally healthy. But I am interested in the process from the point of view of psychology. What happens to the psyche and personality in reality from the point of view of psychology?

Naturally, this process occurs unconsciously. In very strong stressful situations (such as various disasters, the death of loved ones, etc.), psychogenic amnesia may occur - in simple terms, a person does not want to realize or admit what happened and may not remember an event or a whole part of life. nine0089 There are many variants of manifestation of dissociation, and even in the most difficult cases, its manifestation cannot always be unambiguously called a mental illness. Most people are mentally healthy. But I am interested in the process from the point of view of psychology. What happens to the psyche and personality in reality from the point of view of psychology?

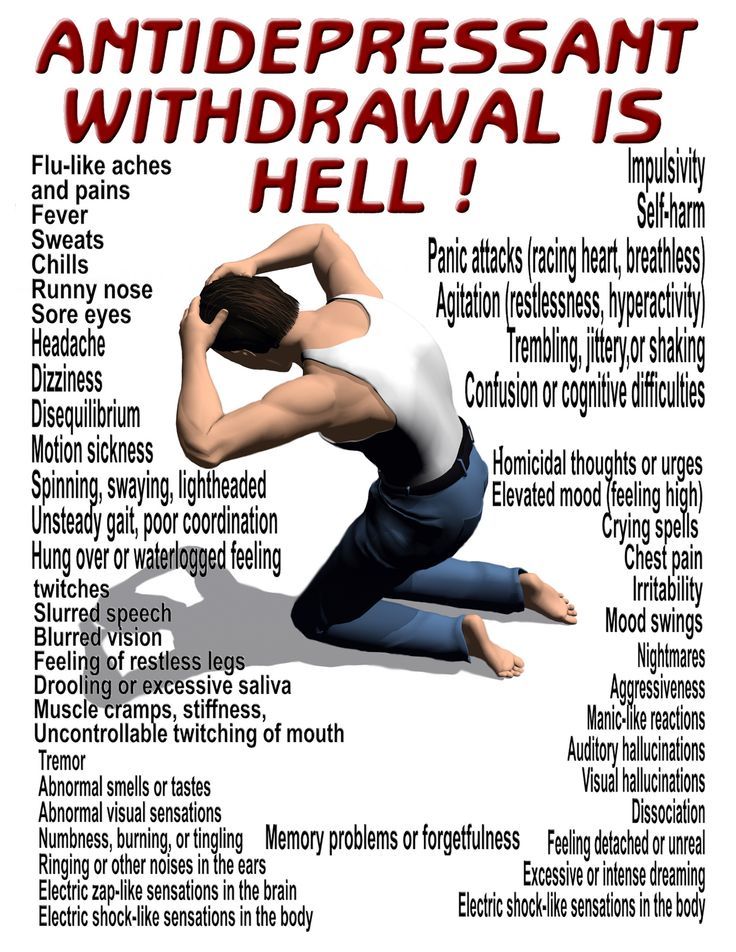

Contrary to some everyday opinions (“maybe it’s easier for him”, “it’s better not to worry”, “let it be”) there is nothing good in dissociation, since this process does not stand still and can aggravate a person’s mental state, further moving away him from reality. In this case, a person unconsciously suffers. In conscious life, this can manifest itself in nightmares, somatic diseases, antisocial behavior, and the use of various psychoactive substances. Often this is justified by the person himself and society: “he had a difficult childhood”, “this happened to him”, etc. The worst thing in this situation is that a person does not live at this time, but exists, since he cannot fully experience his current, real life due to the traumas of the past that have not been experienced. nine0003

Often this is justified by the person himself and society: “he had a difficult childhood”, “this happened to him”, etc. The worst thing in this situation is that a person does not live at this time, but exists, since he cannot fully experience his current, real life due to the traumas of the past that have not been experienced. nine0003

Dissociation is a natural process of the psyche that helps to survive in a stressful situation when a person does not have enough resources for emotional involvement, and I want you to have an understanding of this. Dissociation turns into pathology if this defense process is used constantly as a behavioral pattern.

In addition, we sometimes need dissociation, and to some extent we encounter it in everyday life. Dissociation can occur in a trance state, when a person does something mechanically - for example, he goes half asleep to work, falls asleep, or, on the contrary, tries to keep himself awake to watch an interesting movie, thinks or meditates. nine0003

nine0003

Speech as an indicator

Next, I want to talk about our everyday life: how much we are involved in the process of dissociation, how often we separate ourselves from the current situation, place ourselves in another, or associate ourselves with someone else, separating ourselves from our life why we are doing this, and what it can lead to. And I will analyze it through speech.

Listen to the speech of your interlocutor or to your own speech. What pronoun do you or your interlocutor use when talking about yourself? In many cases, people, speaking about themselves, pronounce “you”, “you”, that is, speaking about themselves, a person does not associate with himself what he is talking about. The reasons for this in each case are individual, but, one way or another, for some reason, unconsciously, a person does not want to associate himself with what he did, does or tells. That is, he unconsciously does not want to, but consciously is or was in a situation and, perhaps, did not even feel that it was harmful or unpleasant to him. This already speaks of the loss of connection between feelings and consciousness, between the body and consciousness, that is, there is already dissociation. Sometimes the feeling of such situations can be called intuition, and intuition is trust in yourself, your feelings, but far from thoughts. After all, thoughts are often ideas that may belong to someone else, but, after thinking about them for a long time, a person gradually begins to take them for his own. But our feelings are definitely our own, they cannot be introduced or borrowed, they are always real. We can say that a person with a well-developed intuition, or rather, a person who hears himself, his feelings, is more healthy, as he is less dissociated. Usually, in the speech of such a person, the pronouns “you”, “you” are less likely to sound when he talks about himself. nine0089 Sometimes, in order to unconsciously get rid of responsibility or add weight to their decision, as well as in a state of uncertainty, people say "we", although in 90% of cases it is an individual action or decision.

This already speaks of the loss of connection between feelings and consciousness, between the body and consciousness, that is, there is already dissociation. Sometimes the feeling of such situations can be called intuition, and intuition is trust in yourself, your feelings, but far from thoughts. After all, thoughts are often ideas that may belong to someone else, but, after thinking about them for a long time, a person gradually begins to take them for his own. But our feelings are definitely our own, they cannot be introduced or borrowed, they are always real. We can say that a person with a well-developed intuition, or rather, a person who hears himself, his feelings, is more healthy, as he is less dissociated. Usually, in the speech of such a person, the pronouns “you”, “you” are less likely to sound when he talks about himself. nine0089 Sometimes, in order to unconsciously get rid of responsibility or add weight to their decision, as well as in a state of uncertainty, people say "we", although in 90% of cases it is an individual action or decision. If the action was joint, then it would be healthier to say "me and someone else." Less dissociated people are less likely to use the pronoun "we" because they feel more individual and more whole.

If the action was joint, then it would be healthier to say "me and someone else." Less dissociated people are less likely to use the pronoun "we" because they feel more individual and more whole.

The next example of speech patterns used in society, indicating dissociation, is statements about ourselves (after all, we can only dissociate ourselves). Such expressions as “my body”, “my body”, with their various continuations (“fat”, “thin”, “wants something”, “hurts”, etc.) are very familiar and natural in our speeches, but what do they do? They separate us from the body. That is, there is a certain “I” sitting in the body. The question arises, who is this “I”? Certainly not the brain, because we hardly think about the brain when talking about ourselves. Also, the brain is part of the body. So, “I” is, most likely, thoughts, consciousness. This is how we quietly separate our consciousness from the body. By the way, in many spiritual practices it is even encouraged. But “I” is a whole: both the body and the spirit taken together, and we are healthy in body and spirit only when there is a connection between them, and we do not break this connection. By no means do I want to say that spiritual practices are harmful, but they need to be approached in a more conscious state - otherwise they will not be beneficial, but, on the contrary, a deeper process of dissociation will begin. nine0089 I want to remind you that I analyze speech and use it as an indicator of mental state. In all the examples I have given, the person already has a dissociation. A person dissociates himself with his thoughts, actions, behavior, lifestyle, attitude towards himself and others.

By no means do I want to say that spiritual practices are harmful, but they need to be approached in a more conscious state - otherwise they will not be beneficial, but, on the contrary, a deeper process of dissociation will begin. nine0089 I want to remind you that I analyze speech and use it as an indicator of mental state. In all the examples I have given, the person already has a dissociation. A person dissociates himself with his thoughts, actions, behavior, lifestyle, attitude towards himself and others.

But I think if you start to become aware of your speech, this will be a serious step towards changing yourself.

I can't help but mention feelings. If you observe, it is quite difficult for people to say "my body feels", yet more often people say "I feel". This is due to the fact that the feelings are in the body, and it is quite difficult to separate them from it. However, I have also come across such cases. What is very interesting, these people were engaged in spiritual practices. Working with such people is very difficult because their level of dissociation is very high. A similar example is phrases like “my psyche can’t stand it”, “... doesn’t accept it”, etc. That is, again, not "I". Everything is fine with me - something is wrong with the psyche, but she is not quite me. The psyche is not me, but it is definitely mine, which means that I manage and control it (no matter how). How to recognize that the psyche controls in an uncontrolled way those who themselves do not know where they are? We recall one of the previous examples about where we “sit”, and we get that it is neither in the psyche nor in the head. Where do we go then? (A question for readers to think about). All these frills happen because saying “I” is much more difficult - different stereotypes can turn on, causing unpleasant questions. For example: “How can I not stand it, am I weak?”, “How can I not control myself and my psyche?”. nine0089 The following examples of dissociation are, oddly enough, the association of oneself with one's profession, with one's place of residence, with things.

Working with such people is very difficult because their level of dissociation is very high. A similar example is phrases like “my psyche can’t stand it”, “... doesn’t accept it”, etc. That is, again, not "I". Everything is fine with me - something is wrong with the psyche, but she is not quite me. The psyche is not me, but it is definitely mine, which means that I manage and control it (no matter how). How to recognize that the psyche controls in an uncontrolled way those who themselves do not know where they are? We recall one of the previous examples about where we “sit”, and we get that it is neither in the psyche nor in the head. Where do we go then? (A question for readers to think about). All these frills happen because saying “I” is much more difficult - different stereotypes can turn on, causing unpleasant questions. For example: “How can I not stand it, am I weak?”, “How can I not control myself and my psyche?”. nine0089 The following examples of dissociation are, oddly enough, the association of oneself with one's profession, with one's place of residence, with things. To give a few obvious examples: “I am a military man” (meaning I cannot feel), “I am a lawyer / manager / official” (meaning I cannot afford to fool around, sincerely have fun), etc. When a person begins to associate himself with his profession, he, as it were, dissolves in it and loses himself. When there is no self-confidence inside, there is no self, you need to cling to something, for example, to a profession - all the more so, some of them have a very high status in society. The profession "sticks", and a person always remains a doctor, military man or lawyer, even among friends or in the family. A profession is a very important area of life, it is self-realization, but there are other areas and we should not forget about them. nine0089 When a person has no "I", or it is very small, he often associates himself with what he wears, what he rides and where he lives - this adds weight, raising the status. But what happens to the psyche? And in the psyche, dissociation occurs, because a person is both a body and consciousness, but not a put on brand and not a “put on” profession.

To give a few obvious examples: “I am a military man” (meaning I cannot feel), “I am a lawyer / manager / official” (meaning I cannot afford to fool around, sincerely have fun), etc. When a person begins to associate himself with his profession, he, as it were, dissolves in it and loses himself. When there is no self-confidence inside, there is no self, you need to cling to something, for example, to a profession - all the more so, some of them have a very high status in society. The profession "sticks", and a person always remains a doctor, military man or lawyer, even among friends or in the family. A profession is a very important area of life, it is self-realization, but there are other areas and we should not forget about them. nine0089 When a person has no "I", or it is very small, he often associates himself with what he wears, what he rides and where he lives - this adds weight, raising the status. But what happens to the psyche? And in the psyche, dissociation occurs, because a person is both a body and consciousness, but not a put on brand and not a “put on” profession. There are people who associate themselves so strongly with their clothes that they cannot put on another, that is, they are not their body and mind, but their clothes. But clothes, cars and other attributes are just aids for life and self-development. Of course, with such an attitude to things, there is no question of personal development. Personality in this case jumps in a circle, like a squirrel in a wheel, dependent on external factors. Unfortunately, in our age of consumption, related products for life are put above who they are made for, and in advertising we hear: “you will be better / more successful / more beautiful if you buy ...” (followed by the name of the corresponding product of this or that brand). nine0089 I gave only a few examples of dissociation that are constantly present in society and "help" to split the already poorly formed personality. Weak, because the industrial society does not promote individualization.

There are people who associate themselves so strongly with their clothes that they cannot put on another, that is, they are not their body and mind, but their clothes. But clothes, cars and other attributes are just aids for life and self-development. Of course, with such an attitude to things, there is no question of personal development. Personality in this case jumps in a circle, like a squirrel in a wheel, dependent on external factors. Unfortunately, in our age of consumption, related products for life are put above who they are made for, and in advertising we hear: “you will be better / more successful / more beautiful if you buy ...” (followed by the name of the corresponding product of this or that brand). nine0089 I gave only a few examples of dissociation that are constantly present in society and "help" to split the already poorly formed personality. Weak, because the industrial society does not promote individualization.

Where does it all begin?

When a child is born, he has no self-identification and does not separate himself from his mother. Gradually, he begins to look around, see himself, raise his head and see the environment, grab objects and walk. Studying the world in this way and comparing himself with it, the child eventually becomes aware of himself as something separate from the whole world. It was at this time that the first thoughts about death began to arise in him, because the former ligaments “I = mother” and “I = the world around” were destroyed, and he became a separate being. At this age, the mother, speaking about the child, often still uses the pronoun “we” (“we walked”, “we ate”, “we pooped”) and this is normal. But around the age of 5 comes the moment when the mother must begin to stimulate and support the process of separation, and this is first done through speech. Speaking of a child, one should now say “he” or “she” (naturally, in the presence of a child or addressing him, call him by name), thereby accustoming the little person to the understanding that he is a separate person. Then you need to gradually delegate to him the responsibility for his own actions and decision-making.

Gradually, he begins to look around, see himself, raise his head and see the environment, grab objects and walk. Studying the world in this way and comparing himself with it, the child eventually becomes aware of himself as something separate from the whole world. It was at this time that the first thoughts about death began to arise in him, because the former ligaments “I = mother” and “I = the world around” were destroyed, and he became a separate being. At this age, the mother, speaking about the child, often still uses the pronoun “we” (“we walked”, “we ate”, “we pooped”) and this is normal. But around the age of 5 comes the moment when the mother must begin to stimulate and support the process of separation, and this is first done through speech. Speaking of a child, one should now say “he” or “she” (naturally, in the presence of a child or addressing him, call him by name), thereby accustoming the little person to the understanding that he is a separate person. Then you need to gradually delegate to him the responsibility for his own actions and decision-making. You can start with the child learning basic self-service skills (dressing, etc.). It is important to encourage his independence - this means to praise, even if he did not succeed. nine0089 Your own example is also very important. Sometimes it seems that parents consider children to be idiots, deaf or blind, when they are much smarter than it might seem. The child's psyche is very flexible, it instantly absorbs and integrates everything that happens around, and this happens several times faster than in an adult. The child is more direct, open to the world and trusting. So if you promise something, do it. If not, explain to your child why. Take responsibility for your actions and decisions. Do not lie or manipulate: children understand perfectly when explained to them, and feel when they are being manipulated. Be honest yourself, and you will not have to reap the fruits of your deceit and manipulation when the child “doesn’t understand whom it behaves like that” or loses trust in parents in adolescence (in modern Soviet psychology, the latter is considered natural, but, nevertheless, nothing happens "suddenly").

You can start with the child learning basic self-service skills (dressing, etc.). It is important to encourage his independence - this means to praise, even if he did not succeed. nine0089 Your own example is also very important. Sometimes it seems that parents consider children to be idiots, deaf or blind, when they are much smarter than it might seem. The child's psyche is very flexible, it instantly absorbs and integrates everything that happens around, and this happens several times faster than in an adult. The child is more direct, open to the world and trusting. So if you promise something, do it. If not, explain to your child why. Take responsibility for your actions and decisions. Do not lie or manipulate: children understand perfectly when explained to them, and feel when they are being manipulated. Be honest yourself, and you will not have to reap the fruits of your deceit and manipulation when the child “doesn’t understand whom it behaves like that” or loses trust in parents in adolescence (in modern Soviet psychology, the latter is considered natural, but, nevertheless, nothing happens "suddenly"). Communicate more with your child, perceive him as a person. This is how a healthy upbringing will be built. nine0089 I think you have heard more than once how the mother of a child already of school age says to her friend: "And we went to school." While still funny, but extremely harmful to the child. However, it is not uncommon for a mother to say: “We went to college” - now this is no longer funny and not funny. Unfortunately, this can go on and on - it’s not for me to tell you what conflicts arise when an already adult person decides to create his own family, and separation from his parents has not occurred. The examples given serve only as a verbal indicator of the lack of separation and self-identification. Of course, there are many more situations themselves, and they are more diverse, and there are many verbal examples. I have given here only the most frequent and conspicuous of them. If the separation did not occur, then it turns out that the person seems to be physically an adult, but mentally he is still infantile.

Communicate more with your child, perceive him as a person. This is how a healthy upbringing will be built. nine0089 I think you have heard more than once how the mother of a child already of school age says to her friend: "And we went to school." While still funny, but extremely harmful to the child. However, it is not uncommon for a mother to say: “We went to college” - now this is no longer funny and not funny. Unfortunately, this can go on and on - it’s not for me to tell you what conflicts arise when an already adult person decides to create his own family, and separation from his parents has not occurred. The examples given serve only as a verbal indicator of the lack of separation and self-identification. Of course, there are many more situations themselves, and they are more diverse, and there are many verbal examples. I have given here only the most frequent and conspicuous of them. If the separation did not occur, then it turns out that the person seems to be physically an adult, but mentally he is still infantile. This is a consequence of the fact that in childhood the parents, due to the peculiarities of their development, could not properly separate the child, and he, in turn, did not learn to associate his decisions and actions with himself, which is reflected in his speech by the use of the pronouns “we” and “you”. ' instead of 'I'. nine0003

This is a consequence of the fact that in childhood the parents, due to the peculiarities of their development, could not properly separate the child, and he, in turn, did not learn to associate his decisions and actions with himself, which is reflected in his speech by the use of the pronouns “we” and “you”. ' instead of 'I'. nine0003

And how does it end?

I specifically began the article with a description of a mental illness in order to show the extreme variants of the development of the dissociation process. At one end are dissociative personality disorders, and at the other are ordinary people around, or so-called neurotics, dissociated to one degree or another. Unfortunately, with age, dissociation is often aggravated, because this process is supported by society and its system, which does not need integral individuals. In addition, the integration process requires a lot of effort from an adult. But I hope that this article will give a topic for reflection to current or future parents, all adults who have found in themselves the traits I described above. There is nothing in this world that cannot be changed, except for death - so while you are alive, go for it! But right now, not tomorrow. Just start with the pronoun "I". nine0003

There is nothing in this world that cannot be changed, except for death - so while you are alive, go for it! But right now, not tomorrow. Just start with the pronoun "I". nine0003

Additional examples

I remembered a few more examples that I think may speak of a neurotic personality.

"In my stairwell" - it's not clear exactly where. “I have a husband / wife” - well, if not silk / th, then it is not clear who exactly - you or .... “My mother’s” is similar to the previous example, but there is still a separation problem here. I also noticed that people began to say “Hello” often when they met. It's like stating the fact of my actions from the series "I'm pooping", "I'm going to the store", "I'm typing an article". In my experience, people who express themselves in this way have narcissistic problems bordering on psychopathy (according to Lowen). Or the familiar “I apologize” - a person speaks of himself in the third person, either because he has not grown up, or because “Napoleon”.