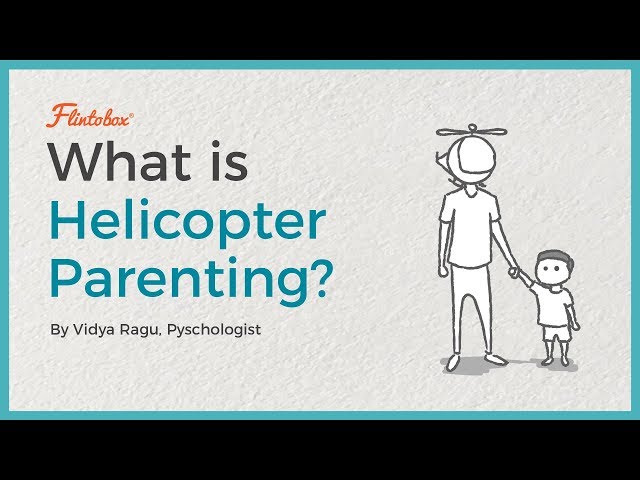

Helicopter parent effects

From Good Intentions to Poor Outcomes

We live in a competitive world and want to give our kids every advantage. But with helicopter parenting, it can backfire big time.

We live in a competitive world and want to give our kids every advantage. But with helicopter parenting, it can backfire big time.

We live in a competitive world and want to give our kids every advantage. But with helicopter parenting, it can backfire big time.

Do you stand over your child’s shoulder when they do their homework? Do you find yourself directing your kids’ every move? “Pick up this, clean up that, sit up straight, finish your homework, study hard, say thank you.” Do you spend a good chunk of your day obsessing about your children’s success, like will they make the sports team or school play, and will they get into the top-notch college you (yes, you!) always dreamed of?

I hate to break it to you, but you may be a helicopter parent—a term which is commonly used but also has a basis in research on specific parenting behaviors and their effects on children.

Most parents want the very best for their children, and so they’ll go to great lengths to be wonderful providers and protectors. The deep love and care that parents have for their children can even push parents to, well, be a bit over-the-top. And helicopter parents are known to be overly protective and involved in their children’s lives.

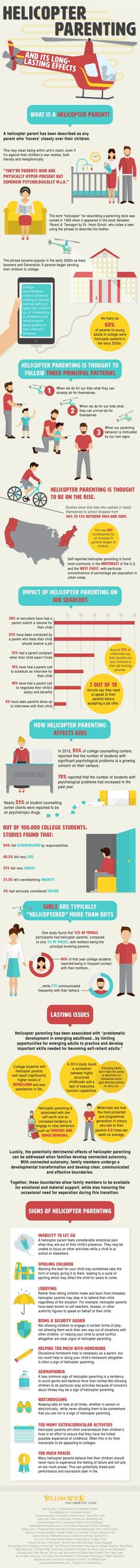

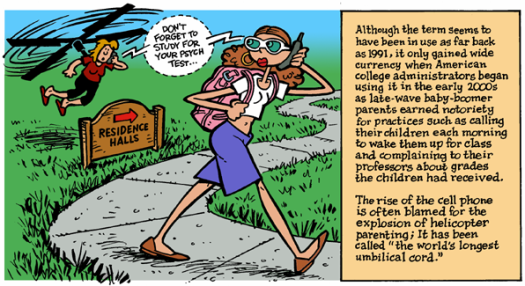

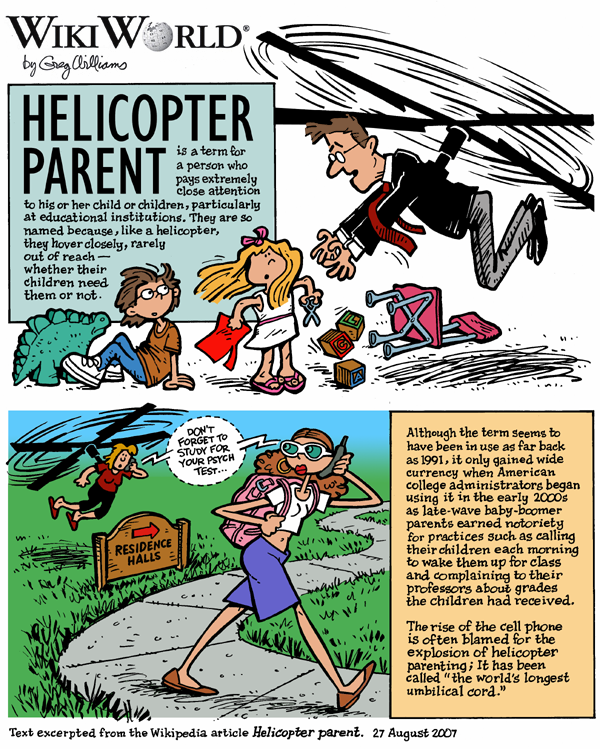

The term paints a picture of a parent who hovers over their children, always on alert, and who swoops in to rescue them at the first sign of trouble or disappointment. The term was first coined in 1990 by Foster Cline and Jim Fay in their book, Parenting with Love and Logic, and it gained relevance with college admissions staff who noticed how parents of prospective students were inserting themselves in the admissions process.

Helicopter parenting can be defined by three types of behaviors that parents exemplify:

- First, information seeking behaviors include knowing your children’s daily schedule and where they are at all times, helping them make decisions, and being informed about grades and other accomplishments.

- Second, direct intervention means jumping into conflicts with kids’ roommates, friends, romantic partners, and even bosses.

- Third, autonomy limiting is when students think their parents are preventing them from making their own mistakes, controlling their lives for them, and failing to support their decisions.

We all want to love our children as much as possible and protect them from the dangers in our society. We live in an increasingly competitive world and want to give our kids every advantage possible. But if we over-parent and smother them, it can backfire big time. A collection of research in recent years shows a connection between helicopter parenting and mental health issues like anxiety and depression as children get older and try to make it on their own.

The negative impacts of helicopter parenting

In 2010, a study by researcher Neil Montgomery, a psychologist at Keene State College in New Hampshire, found that overprotective parents might have a lasting impact on their child’s personality by prolonging childhood and adolescence. Approximately 300 college freshmen were surveyed about their level of agreement with statements regarding their parents’ involvement in their lives. The results showed that 10 percent of the participants had helicopter parents. The research also revealed that students with helicopter parents tended to be less open to new ideas and actions, and were more vulnerable, anxious, dependent, and self-conscious.

Approximately 300 college freshmen were surveyed about their level of agreement with statements regarding their parents’ involvement in their lives. The results showed that 10 percent of the participants had helicopter parents. The research also revealed that students with helicopter parents tended to be less open to new ideas and actions, and were more vulnerable, anxious, dependent, and self-conscious.

A 2016 study from the National University of Singapore published in the Journal of Personality indicated that children with intrusive parents who had high expectations for academic performance, or who overreacted when they made a mistake, tend to be more self-critical, anxious, or depressed. The researchers termed this as “maladaptive perfectionism,” or a tendency in children of helicopter parents to be afraid of making mistakes and to blame themselves for not being perfect. This happens because the parents are essentially—whether by their words or actions—indicating to their kids that what they do is never good enough.

Another 2016 study evaluated questionnaires about parenting completed by 377 students from a Midwestern university. Students responded to statements about the type of parents they have, how often they communicate with their parents, and how much their parents intrude in their lives. The students also completed a number of tests to discern their decision-making skills, academic performance, and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Results showed that higher overall helicopter parenting scores were associated with stronger symptoms of anxiety and depression.

According to that study, helicopter parenting “was also associated with poorer functioning in emotional functioning, decision making, and academic functioning. Parents’ information-seeking behaviors, when done in absences of other [helicopter parenting] behaviors, were associated with better decision making and academic functioning.”

In addition, the journal Cognitive Therapy and Research published research in 2017 suggesting that helicopter parenting can trigger anxiety in kids who already struggle with some social issues. A group of children and their parents were asked to complete as many puzzles as possible in a 10-minute time period. Parents were allowed to help their children, but not encouraged to do so.

A group of children and their parents were asked to complete as many puzzles as possible in a 10-minute time period. Parents were allowed to help their children, but not encouraged to do so.

Researchers noted that the parents of children with social issues touched the puzzles more often than the other parents did. Though they were not critical or negative, they stepped in even when their children did not ask for help. Researchers think this indicates that parents of socially anxious children may perceive challenges to be more threatening than the child thinks they are. Over time, this can diminish a child’s ability to succeed on their own and potentially increase anxiety.

So how does all this hovering cause mental health problems in our children?

First of all, helicopter parents are communicating to their children in subtle (or not-so-subtle) ways that they won’t be safe unless mom or dad is there looking out for them. When these children have to go off on their own, they are not prepared to meet daily challenges. This inability to find creative solutions and make decisions on their own can cause a great deal of worry since their protector is no longer around to help them.

This inability to find creative solutions and make decisions on their own can cause a great deal of worry since their protector is no longer around to help them.

Because these children were never taught the skills to function independently, and because they may have been held to unattainable or even “perfectionist” standards, children of helicopter parents can experience anxiety, depression, a lack of confidence, and low self-esteem. Another issue is that if these kids have never experienced failure, they can develop an overwhelming fear of failure and of disappointing others. Finally, if we don’t let our children have the freedom to learn about the world and discover their purpose and what makes them happy, they will struggle to find happiness and live a balanced life—all impacting their mental health.

What we can do to break the helicopter habit

All parents know that parenting is not easy. Having children and raising them presents innumerable challenges and surprises, but also immense joy and connection. Now that we know that overparenting only leads to more problems for our kids, we can make the following adjustments in our parenting approach:

Now that we know that overparenting only leads to more problems for our kids, we can make the following adjustments in our parenting approach:

- Support your children’s growth and independence by listening to them, and not always pushing your desires on them.

- Refrain from doing everything for your children (this includes homework!). Take steps to gradually teach them how to accomplish tasks on their own.

- Don’t try to help your children escape consequences for their actions unless you believe those consequences are unfair or life-altering.

- Don’t raise your child to expect to be treated differently than other children.

- Encourage your children to solve their own problems by asking them to come up with creative solutions.

- Teach your children to speak up for themselves in a respectful manner.

- Understand and accept your children’s weaknesses and strengths, and help them to use their strengths to achieve their own goals.

Parents should, of course, do the best they can for their kids. Impulses to involve ourselves in our children’s’ lives often come from a sense of duty, and of unconditional love. We can harness those desires to give the most we can to our kids by resisting helicopter parenting, which can lead to poor outcomes in adulthood.

Impulses to involve ourselves in our children’s’ lives often come from a sense of duty, and of unconditional love. We can harness those desires to give the most we can to our kids by resisting helicopter parenting, which can lead to poor outcomes in adulthood.

Instead, try letting your children discover themselves—their weaknesses, strengths, their goals and dreams. You can help them succeed, but you should also let them fail. Teach them how to try again. Learning what failure means, how it feels, and how to bounce back is an important part of becoming independent in our world.

The Marriage Minute is an email newsletter from The Gottman Institute that will improve your marriage in 60 seconds or less. Over 40 years of research with thousands of couples has proven a simple fact: small things often can create big changes over time. Got a minute? Sign up below.

Sandi Schwartz

Sandi Schwartz is a freelance writer/blogger and mother of two. ="wpforms-"]

="wpforms-"]

Helicopter Parenting: The Consequences - International School Parent

Subscribe to our newsletter

and be the first to get the newest updates

Email Address

“How to begin to educate a child. First rule: leave him alone. Second rule: leave him alone. Third rule: leave him alone. That is the whole beginning.”

– D.H. Lawrence

WHAT IS A “HELICOPTER PARENT”?

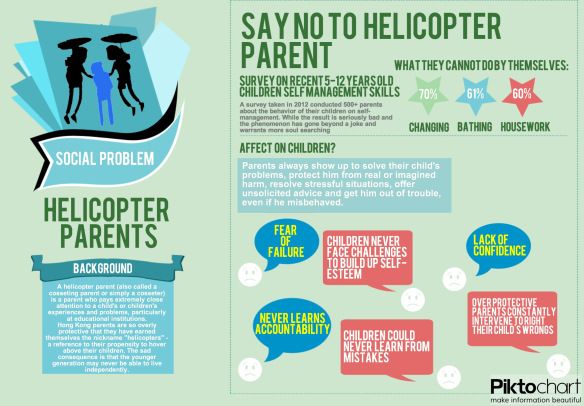

Helicopter parenting means being involved in a child’s life in a way that is overcontrolling, overprotecting, and overperfecting. It means staying very close, rarely out of reach, paying extremely close attention to your child and rushing over to prevent any harm, physically and psychologically, to the point of enmeshment. This is where personal boundaries are diffused, sub-systems undifferentiated and over-concern leads to a loss of autonomous development.

If you thought helicopter parents were too much, wait till you learn about Lawnmower Parents. These are the new generation of helicopter parents, who take overparenting to the next level. Rather than hovering, these parents actively prepare the way for their children to succeed, they mow down all obstacles they see in their child’s path; make sure their kids always look perfect and if they don’t, they’ll intervene and make it better right away. This does not sound good!

These are the new generation of helicopter parents, who take overparenting to the next level. Rather than hovering, these parents actively prepare the way for their children to succeed, they mow down all obstacles they see in their child’s path; make sure their kids always look perfect and if they don’t, they’ll intervene and make it better right away. This does not sound good!

However, if most parents read this they will likely say, phew that is not me. So, let’s look at a few examples:

- You prevent your child from exploring and stretching his abilities (e.g. your child climbs a tree (or anything), you run over and tell them to not do that).

- In toddlerhood, you might constantly shadow your child, always playing with and directing his behavior, allowing them no alone time.

- In elementary school, you ensure your child has a certain teacher or coach, selecting the child’s friends and activities.

- You monitor and control their homework, providing disproportionate assistance for homework and school projects.

- You shield them from failure, if they fail then you pull your weight to change that.

- You do for your child what he/she can actually do for herself.

- You influence your child to work as per your ambitions.

- You negotiate your child’s conflicts.

- You do their academic works or get overly involved.

- You train your child’s trainers, telling them how to do things differently for your child.

- You hold the responsibility for all your child’s house chores.

- You don’t allow them to tackle their problems.

- You don’t allow them to make age appropriate choices.

When we look at this list of actions we can see that the difficulty with this often is the degree to which they get exercised. If, for instance, your child is stuck with homework and he/she comes to you for help it is normal to offer assistance. However, if your child is doing their homework and you consistently check the homework or monitor what they are doing, this is a step further. If your child climbs a tree that is truly a danger then asking them not to is responsible. However, if they approach any tree and they are told not to climb, well then you restrict the growth of their neurological limitations. As such it is easy to see where a parent might not have the awareness of their own helicopter parenting.

If your child climbs a tree that is truly a danger then asking them not to is responsible. However, if they approach any tree and they are told not to climb, well then you restrict the growth of their neurological limitations. As such it is easy to see where a parent might not have the awareness of their own helicopter parenting.

LONG TERM CONSEQUENCES

This type of excessive parenting, even though done with genuine intention, has some serious kickbacks and severe long-term consequences that most are not aware of. Here is a list of these side-effects:

1. Underdevelopment of the brain.

Helicopter parenting implicitly involves parents taking decisions for their children, reducing their need to problem solve and make their own decisions. The area of the brain that deals with these components is housed in the prefrontal part of the brain. This part of the brain is found to only have fully developed at 25 years of age. However, it is like a muscle and if not given the chance to exercise it will not grow substantially, meaning that these skills will stay underdeveloped.

The brain is exercised by “doing”, this means by doing it yourself, failing and falling, and learning how to better do it next time. This is what increases the connectivity and effectiveness of this part of the brain. Having helicopter parents could be hindering a child’s ability to develop problem-solving and decision-making skills; skills that we want our children to have copious amounts of when they leave the nest, so they can make the most well-informed decisions in all aspects of their life and get through it as unscathed as possible. As such by not letting them fall and learn and do better next time, we hinder the development of brain and with it the copious capacities needed to thrive socially, personally and academically.

2. Emotional backlash.

Additionally, if parents exert too much control over situations and step in before children try to handle the challenge on their own, or physically keep children from challenging contexts altogether, they may hinder the development of self-regulatory abilities. Again, this is related to the control of the prefrontal cortex, the more developed it is the more of a lid it can hold down on emotions. This is a well-researched area, for instance a research study published in the journal of Developmental Psychology determined that 2-year-olds exposed to this kind of parenting ended up less able to regulate their own emotions and behavior by age 5. That upped the risk for emotional problems at age 10.

Again, this is related to the control of the prefrontal cortex, the more developed it is the more of a lid it can hold down on emotions. This is a well-researched area, for instance a research study published in the journal of Developmental Psychology determined that 2-year-olds exposed to this kind of parenting ended up less able to regulate their own emotions and behavior by age 5. That upped the risk for emotional problems at age 10.

3. Low self-esteem and confidence.

Helicopter parenting backfires! The over involvement of the parent makes the child believe that their parents will not trust them if they do something independently. It, therefore, leads to lack of self-esteem and confidence. When we parent this way, we deprive our kids of the opportunity to be creative, to problem solve, to develop coping skills, to build resilience, to figure out what makes them happy, to figure out who they are. Although we over involve ourselves to protect our kids and this may in fact lead to short-term gains, our behavior actually delivers the rather implicit soul-crushing news: Kid, you can’t actually do any of this without me. It is that which we as parents need to keep at the forefront, “What am I implicitly telling my child?” This is what our kids take away, not the physical words but the underlying message.

It is that which we as parents need to keep at the forefront, “What am I implicitly telling my child?” This is what our kids take away, not the physical words but the underlying message.

4. Immature coping skills, low frustration tolerance = disadvantage in the work force.

When the parent is always there to prevent the problem at first sight or clean up the mess, the child can never learn through failure, disappointment or loss – inevitable aspects of everyone’s life. They deprive the kids of any meaningful consequences for their actions. As a result, the kids miss out on the opportunity to learn valuable life lessons from the mistakes they make; life-lessons that would contribute to their emotional intelligence.

When seemingly perfectly healthy but overparented kids get to college and have trouble coping with the various new situations they might encounter—a roommate who has a different sense of “clean,” a professor who wants a revision to the paper but won’t say specifically what is “wrong,” a friend who isn’t being so friendly anymore, making choices—they can have real difficulty knowing how to handle the disagreement, the uncertainty, the hurt feelings, or the decision-making process.

This inability to cope—to sit with some discomfort, think about options, talk it through with someone, make a decision—can become a problem unto itself. When these kids grow up, they don’t know how to resolve difficulties. Hence the fallout is that over-protection makes it nearly impossible for these young people to develop problem solving skills and frustration tolerance and without these important psychological attributes, young people enter the workforce at a great disadvantage.

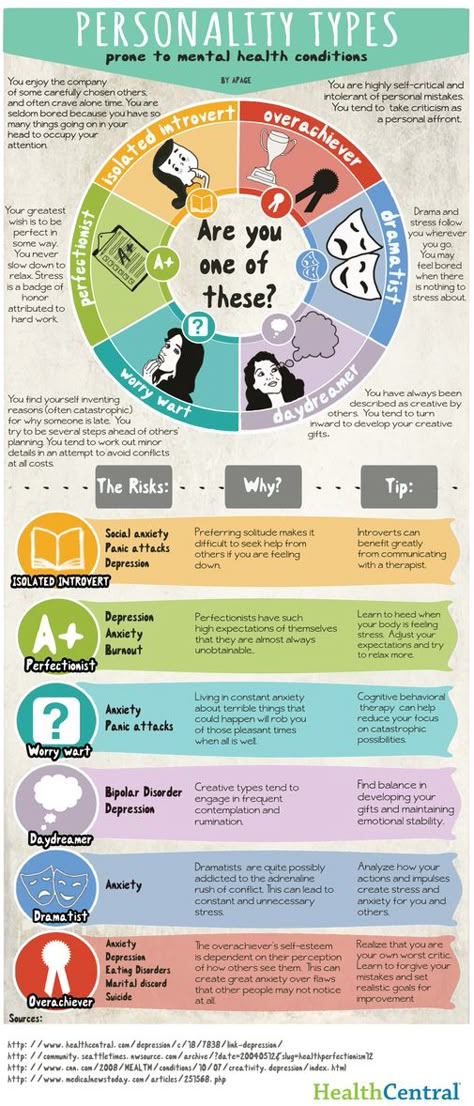

5. Mental Health Problems.

Helicopter parenting increases a child’s depression and anxiety levels. They are always in look out for guidance, and when left alone, they become too nervous to take a decision. Multiple studies over the past decade summarize the social and psychological risks of being a helicopter parent’s child. These kids are less open to new ideas and activities and more vulnerable, anxious and self-conscious.

The other problem with never having to struggle is that you never experience failure and can develop an overwhelming fear of failure and of disappointing others. Both the low self-confidence and the fear of failure can lead to depression or anxiety. Studies show that when they reach college, children of overbearing parents are found to be more likely to be medicated for anxiety or depression. The data emerging about the mental health of our kids only confirms the harm done. At the end of the day we want our kids to be happy. However, driving them does the opposite, it robs them of the ability to discover who they are and what internally drives them. Without this understanding of oneself, happiness hardly ever happens.

Both the low self-confidence and the fear of failure can lead to depression or anxiety. Studies show that when they reach college, children of overbearing parents are found to be more likely to be medicated for anxiety or depression. The data emerging about the mental health of our kids only confirms the harm done. At the end of the day we want our kids to be happy. However, driving them does the opposite, it robs them of the ability to discover who they are and what internally drives them. Without this understanding of oneself, happiness hardly ever happens.

6. Sense of entitlement complex.

When parents involve themselves in their child’s academic, social and athletic lives, children get accustomed to always having their parents to fulfill their needs. This makes them demanding as they feel that it is their right to have what they want.

7. Meanness and aggression

Research shows that kids raised by intrusive helicopter parents tend to be meaner or more hostile towards other kids. This is believed to be a response of extreme parental control. Kids act out and assert their dominance as a way to regain a sense of agency over their lives. As such, they tend to become irritable and less patient when faced with having to relate well with peers.

This is believed to be a response of extreme parental control. Kids act out and assert their dominance as a way to regain a sense of agency over their lives. As such, they tend to become irritable and less patient when faced with having to relate well with peers.

HOW DOES THIS STYLE OF PARENTING COME ABOUT?

Fear for our children.

The standard of overparenting (helicopter parenting) is a few decades in the making and is largely derived from a cocktail of dread: fear that our children might be injured or kidnapped, anxiety that they might not be academically or socially successful in the absence of constant supervision, and worry that not tending to a child’s every need will somehow lead to irreparable psychological damage. As a remedy, some parents have embraced intensive parenting styles that are endlessly caricatured, but have nonetheless shifted the collective expectation of what it means to be a responsible, devoted parent and it seems like the situation is getting worse.

Comfortable financial situation.

A variety of factors shape the ability to provide such an involved and attached level of parenting, and finances are among the most important. Helicopter parenting is more readily adopted by parents in the socioeconomic stratosphere. Money may not buy happiness, but it creates space and time —including, in some cases, the option for one parent to stay home.

Research reveals an interesting self-perpetuating cycle: professional women who left work to prioritize parenthood often justified that decision by making child-rearing a full-time, all-encompassing job, which in turn raised the stakes of what ideal parenting looks like. This shifted goalposts, creating a new, hard-to-achieve standard for others to live up to. In our current times of social media, visibility and connection through digital means offers a new level of support, but also a new level of judgment. Parents—mothers, particularly—aren’t just living up to standards set by moms on the playground or the PTA, but the ones they encounter online.

Social media has upped the ante and parents are desperate to make their kids look as successful as possible in the eyes of online viewers. Parenting is a race to gain the greatest number of awards and experiences on behalf of their child in the shortest amount of time, and posting these successes on Facebook. In addition, due to the competitive nature of social media, parents fear their children will fail and can’t meet these requirements, and this leads them to take charge of their kids’ problems. For the same reason they fill their kids’ agendas from early age with dozens of extracurricular activities which, they indicate, are aimed to help them prepare for adult life.

Only child.

There are many other reasons for this particular parenting style. For instance, children being seen as material property of great value. The fact that couples have children in more advanced age, often after undertaking various fertility treatments, means that these children are considered a very valuable asset that must be protected at all costs. So children end up being considered gods, metaphorically speaking. Equally parents do not want to be seen as “emotionally distant parents” so they overcompensate by being excessively present.

So children end up being considered gods, metaphorically speaking. Equally parents do not want to be seen as “emotionally distant parents” so they overcompensate by being excessively present.

And more…

Another reason is what parents “think” is expected of them, if a child loses their ball in the water, rather than letting the kid figure it out they think to themselves: “If I don’t run to get the ball others will think I am negligent as my kid might wade out to get it themselves”. Other reasons that parents overparent is a validation of how they did themselves as parents. And so especially senior year is the witching hour, where this parenting style becomes over prevalent. One principal said, “ I think for a lot of parents, college admissions is like their grade report on how they did as a parent.”

Each one of us will innately know what our reasons are if we sit down with this question for long enough. Regardless of the reasons behind this we must, for the health and wellbeing of our children and in turn their children, move away from this pattern.

HOW TO PREVENT HELICOPTER PARENTING

Always, always, think of the long-term goal, not the now. What is it I want my child to achieve? Can he achieve it with my interference?

- A child is stuck on a homework problem and you help them by giving them the solution. The long-term goal is that they become their own problem solvers. So, this is an example of what not to do. What you can do is suggest ways of thinking about the problem or nudge them to research the answer to the problem.

- A child comes home after having a fight with a friend. The long-term goal is for them to learn to be flexible in their thinking and come up with potential solutions. Telling them what to tell their friend would not be the answer. However, offering a listening ear and hearing them out as they track through the possible solutions, is the right thing to do to achieve the long-term goal.

Remember to think “What am I implicitly telling my child”. Our children take away the underlying message, not the actual words.

- Remember their brains grow by letting them do. If we always pick up what is on the floor, what they drop, then the physicality of checking and reaching to pick up does not wire and they will be hard pressed to become neat as they grow. If I pick up my child’s jumper when we leave the waiting room, what am I implicitly teaching my child? Well, that others will do the work for him (and again they are not creating those neurological connections for themselves). If I keep checking my child’s work each time he does his homework, what am I implicitly telling my child? Well, “you need to rely on others to do a good job because on your own you might not do it well enough”.

- Ask “Whose problem is this?” If these really are kid problems, then our job is not to solve them. It’s to help the kid solve them. Research on rats shows that when you shock them, it’s extremely stressful. But if you give them a wheel to turn after, it gives the rat a sense of control and the prefrontal cortex activates.

Then in similar stressful situations, the rat can leap into a coping mode, even in situations that are uncontrollable.What we want to do is condition kids when they have a problem to leap into coping mode as opposed to waiting for their parent (or someone else later in life) to solve the problem. The latter can again also lead to learned helplessness, anxiety and depression. There are some problems a kid can’t solve themselves. If they’re being mercilessly bullied at school, an adult needs to step in. But we want as much as possible for kids to develop that coping impulse. It almost inoculates kids from stress by experiencing that. There’s a big difference between coaching a kid and trying to solve problems for them.

Then in similar stressful situations, the rat can leap into a coping mode, even in situations that are uncontrollable.What we want to do is condition kids when they have a problem to leap into coping mode as opposed to waiting for their parent (or someone else later in life) to solve the problem. The latter can again also lead to learned helplessness, anxiety and depression. There are some problems a kid can’t solve themselves. If they’re being mercilessly bullied at school, an adult needs to step in. But we want as much as possible for kids to develop that coping impulse. It almost inoculates kids from stress by experiencing that. There’s a big difference between coaching a kid and trying to solve problems for them.

HOW CAN PARENTS GIVE UP CONTROL WITHOUT CHECKING OUT COMPLETELY?

When kids feel securely attached to a parent or caregiver they feel safe, and when they feel safe, they explore and take risks appropriately. They’re more adventurous. Having the internal sense of safety, or a “safe base,” is simply good for human beings. In one study, researchers separated baby rats from their mothers every day for a couple of weeks, which was extremely stressful for the rats, and then bring them back to their mothers. When mothers licked and groom them for a long time after and let them know they were okay, these rats became almost impossible to stress as adults. But you have to have that den, that environment to let your guard down.

In one study, researchers separated baby rats from their mothers every day for a couple of weeks, which was extremely stressful for the rats, and then bring them back to their mothers. When mothers licked and groom them for a long time after and let them know they were okay, these rats became almost impossible to stress as adults. But you have to have that den, that environment to let your guard down.

- Stop saying “we”! I catch parents saying this a lot “we need to go home to do homework”. Huh, no, it should be “we need to go home so you can do homework”. I hear “we didn’t do so well on that test”. Hum? Who’s test is it?

- Stop arguing with adults in your kids life. Let them do the problem solving, but you can guide them.

- Stop doing their homework! Stop checking their homework! Parents seem to find this the hardest. When this is stopped from a young age, kids will learn to self-monitor. Don’t worry the negative consequence of looking bad before their teacher and peers will mostly motivate them to do their homework.

When they are coached through their homework and suddenly at 12 years they are expected to do it on their own, this becomes a terrifying chore with no internal self-regulation.

When they are coached through their homework and suddenly at 12 years they are expected to do it on their own, this becomes a terrifying chore with no internal self-regulation. - Stop solving your kids problems!! Ask them, “ well what do you think you should do”. Ok, go try it out and then tell me how it went. Do not give them the answers! Let them trial and fail and trial and succeed. Do you know how much effort and energy parents put into trying to find solutions or giving the answers? I am sure you know!

- We need to stop over-scheduling our kids and let them play outdoors on their own, without adult supervision or control. We need to trust our kids and recognize that they’re smart, resourceful young people, better able to care for themselves than we might imagine. When our kids can spend time just playing and hanging out with one-another, they’ll learn essential life skills including leadership, cooperation, problem-solving, flexibility and compassion.

Keep in mind a good motto: “ Our job as parents is to put ourselves out of job!!”

LET THEM FALL!

The main message here is clear and bears overwhelming importance: LET THEM FALL. Oh I can hear it already “What! that is totally irresponsible and dangerous”. Hear me out….. Yes let them fall……but…this is the image you need to keep in your mind: Your child is a tight rope walker in a circus (life), his aim is to walk that tight rope as safely as possible and get through the walk with his head held high, a sense of accomplishment, joy and unscathed as much as possible.

Oh I can hear it already “What! that is totally irresponsible and dangerous”. Hear me out….. Yes let them fall……but…this is the image you need to keep in your mind: Your child is a tight rope walker in a circus (life), his aim is to walk that tight rope as safely as possible and get through the walk with his head held high, a sense of accomplishment, joy and unscathed as much as possible.

So, if you hold your child’s hand as they try and walk that rope, what happens? Well, they will do quite well, they might wobble a little, they will get through it….but….will they learn it for themselves? What happens in this situation? Well, they won’t have made the neurological pathways to be able to sustain themselves on that rope, their brain will not have grown in those areas and they will fall, hard on to the ground.

BUT BE THE NET.

Now, if you are not the hand holder but are the net, what happens? Your child will get up there with fear in their hearts, sweating profusely, knees like jelly but at some point they will get the courage to start that walk as they know that if they fall the net is there, you are there to catch them. And they WILL fall, no doubt about that, many times. But what happens?? Well, they gain the confidence in themselves that bit by bit they can maneuver this challenge better, they gain the confidence that they can do it themselves but have someone there to not make the fall too hard when it goes wrong.

And they WILL fall, no doubt about that, many times. But what happens?? Well, they gain the confidence in themselves that bit by bit they can maneuver this challenge better, they gain the confidence that they can do it themselves but have someone there to not make the fall too hard when it goes wrong.

Slowly slow, the fear subsides, the sweating subsides, the wobbly knees dissipate and they start walking straighter, they start walking with confidence, they start smiling, they are sturdy, they are happy and they know in their gut and in their heart beyond a shadow of a doubt that I CAN DO IT on my own. Now when they leave your nest at whatever age it may be YOU too will know in your heart of hearts that YOUR child can make it in this world with or without you and that my dear parent is something worth striving for!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR.

Laurence van Hanswijck de Jonge is a Developmental Neuropsychologist who provides developmental and psychological assessments as well as parental coaching and resilience training for English speaking children between the ages of 3 and 18 in Geneva and neighbouring Vaud, Switzerland. Her practice is rooted in Positive Psychology and her belief in the importance of letting our children flourish through building on their innate strengths.

Her practice is rooted in Positive Psychology and her belief in the importance of letting our children flourish through building on their innate strengths.

www.Laurencevanhanswijck.com

Read more articles here.

Share now

Subscribe to our newsletter

and be the first to get the newest updates

Email Address

Ancestral helicopter. The real reason for the discontent of British teenagers / Habr

English society is interested not only in the problems of the survival of horses and zebras, but also in the future of their own younger generation.

Below is a translation of an article about the problems of children and their upbringing in England. Although, it seems to me that these same questions apply not only to children growing up on the other side of the western borders ...

It is said that children growing up in the UK are among the most unhappy in the industrialized world. The UK currently has the highest rates of self-harm in Europe. And the NSPCC's annual review of Child Protective Services lists this as one of the top reasons children turn to charities.

The UK currently has the highest rates of self-harm in Europe. And the NSPCC's annual review of Child Protective Services lists this as one of the top reasons children turn to charities.

Fig_1. Children are under every minute control and management, it is not surprising that this affects their mental health.

Children's mental health is becoming one of the most pressing issues in British society. A recent report from The Prince's Foundation highlights that a growing number of children and young people are dissatisfied with their lives, sometimes with tragic consequences.

This is a generation of young people who are called snowflakes - unable to cope with stress and more prone to resentment. They are also said to have less psychological resilience than previous generations and are too emotionally vulnerable to deal with the problem on their own.

Social media is likely to play a role in all of this. Research shows that almost three-quarters of teens aged 12 to 15 in the UK have a social media profile and spend an average of 19 hours a week online. This is the Facebook generation, after all, and never before have children grown up with such a daily bombardment of photos, products, and messages.

This is the Facebook generation, after all, and never before have children grown up with such a daily bombardment of photos, products, and messages.

But there are other reasons that are much closer to home. In our new book The Taming of Childhood? we make the argument that children and young people may indeed have less resilience than previous generations, but this is because they have less opportunity to develop it. The reason for this is that childhood turns into training.

"Dangers" of childhood

Childhood today is often perceived by parents as fraught with dangers. Not only are there issues with where kids can play, who they can talk to and what they should and shouldn't do, but the internet has opened up a whole new set of issues that parents and police need to experience.

The lives of children literally suffocate them. Kids can no longer hang out with friends unsupervised, explore their community, or hang out in groups without arousing suspicion. Very few unsupervised games and activities take place for children in public places or even in homes, and their free time is often eaten up by housework or organized activities.

Very few unsupervised games and activities take place for children in public places or even in homes, and their free time is often eaten up by housework or organized activities.

It also depends on how children are taught in schools, and how the pursuit of success has led to the taming of education. But if children never have difficulties, if they never experience adversity or personal risks, then it is not surprising that they will lack resilience.

Taking control

This is not the result of any particular change or development, nor is it intentional. Much of the suppression of children's experiences is often wrapped around the idea of what's best for the children, or thoughts of being a good parent.

This can be seen in the safety approaches that aim to eliminate all risks to children's lives. Or in approaches to education, when adults make decisions and limit the possibilities of children. Ultimately, this means that children have fewer opportunities to intervene, explore and experience their world.

Concepts of good parenting that emphasize knowing where children are and keeping them safe, combined with cutting-edge ideas that view children as naturally vulnerable, also fail to recognize their ability to cope with situations that we, as adults, find difficult.

All of this is happening against a backdrop of growing concerns about the welfare of children. But what adults consider important for a child's well-being and what children themselves consider important may not be the same.

Competitive parenting

Children are very often viewed in terms of who they will become, not who they are. This has led to the rise of an intensive type of parenting, often referred to as helicopter parenting. Research has shown that well-being is reduced in children who experience helicopter parenting.

It is possible that the competitive nature of modern society encourages parents to dominate their children's lives for reasons that are expedient to them. But in doing so, they act contrary to the long-term interests of their children.

But in doing so, they act contrary to the long-term interests of their children.

The idea that children should not face risk and be protected from everyday adversity means that parents limit where children can go and what they can do, especially when unsupervised. This leads to a childhood that for many children is characterized by supervision, surveillance and the absence of any real problems.

Thus, this is not a problem of youth, but a problem of society and parents. Clearly, in this case, parents need to be supported, not judged, so that they can feel confident that their children will receive a certain level of decision-making and freedom. Children also need to be seen as more valuable to society so that the play area for unsupervised children is once again a popular place. Education also needs to be rethought so that children are not under constant pressure, but can become independent and cheerful people again.

Russia: how children from the Tundra fly to school by helicopter.

.. I will see my parents just before the New Year. This is the most common model of school education for children of nomadic reindeer herding communities. You and I take children to school by car, we pick them up after school… In the north, school education among indigenous peoples has completely different rules. This is my article today, I will talk about the wonderful teachers I met in Naryan-Mar, as well as the experience of Yakutia, which even Canada and the USA adopt.

.. I will see my parents just before the New Year. This is the most common model of school education for children of nomadic reindeer herding communities. You and I take children to school by car, we pick them up after school… In the north, school education among indigenous peoples has completely different rules. This is my article today, I will talk about the wonderful teachers I met in Naryan-Mar, as well as the experience of Yakutia, which even Canada and the USA adopt. This is a report from the series "Happy People" - stories, people, real life in the North of Russia.

1.

Meet Lyudmila Viktorovna Pashkina A. P. Pyrerki of the city of Naryan-Mar.

2.

Elena Vasilievna Smetanina , social teacher of the school:

3.

Amazing people… we talked for more than two hours and only late in the evening made me stop talking. Each material from my school series is unusual in its own way, but it is in this school that there are so many features not so much of learning and process as of psychology and relationships. Only true professionals and fans of their craft can move life forward with such devotion and enthusiasm. I will write more about the school itself in one of the following reports, but today I want to talk about how the process of teaching children who live in nomadic reindeer farms is organized.

Only true professionals and fans of their craft can move life forward with such devotion and enthusiasm. I will write more about the school itself in one of the following reports, but today I want to talk about how the process of teaching children who live in nomadic reindeer farms is organized.

4.

To school straight from the chum...

201 children aged 8 to 18 from the settlements of the Nenets Autonomous Okrug study at the boarding school, of which:

- children who are on full state support (orphans, when parents are deprived of parental rights, partially deprived, etc.) - 111

- children in a difficult life situation, i.e. whose parents, for various reasons, cannot temporarily fulfill parental obligations - 3

- as well as "home" children from settlements where there are no schools. This educational institution trains children from 13 localities of the district, where there are no educational institutions, or there is only an elementary school. The most remote settlement from this school is Ust-Kara, 4 hours by helicopter.

The most remote settlement from this school is Ust-Kara, 4 hours by helicopter.

The indigenous population of the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, who work in reindeer farms in the tundra, leads a nomadic lifestyle. In Soviet times, there were attempts to create stationary reindeer-breeding "collective farms", but this is impossible and inapplicable in practice. The life of reindeer herders is a constant movement across the tundra from one camp to another all year round, they stay in one place for no longer than 1-2 months, as the reindeer eat reindeer moss within the camp.

There are 42,000 inhabitants and 180,000 reindeer in the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, which are on natural grazing in the vast expanses of the tundra. This traditional way of life is difficult to imagine for us living in the city, but these families live like this from generation to generation. Yes, the plague now has a TV, a satellite dish and other attributes of technological progress, but only the way of life itself does not change and will not change in the future. Deer are not bred otherwise.

Deer are not bred otherwise.

In the summer, the whole family of reindeer herders spends in the tundra, including women and children. In late August-early September, children are collected across the tundra by helicopters, and in December, before the new year, they are returned back to their families. In winter, only men stay in the tundra, women usually spend the winter in the village, where they are sometimes taken by helicopter along the way in September with their child ...

A child spends in the plague from infancy, already at the age of 4-5 children run the household almost on a par with adults, and then, suddenly, school age begins. For example, Karataika - in this region, the largest percentage of families lead a traditional way of life, the children of which study at this school in Naryan-Mar. For education in grades 1-4, there is an elementary school in Karatayk, and from grades 5 to 11, children are already flying to a boarding school here. And in some settlements there is no elementary school!

The most serious problem is the return of children to a traditional way of life. During the time spent in the city, the child loses the skills that were acquired in the tundra. According to the statistics of the boarding school, up to 80% of children still return to the tundra to their villages or to reindeer herding farms. This is a very high and good indicator.

During the time spent in the city, the child loses the skills that were acquired in the tundra. According to the statistics of the boarding school, up to 80% of children still return to the tundra to their villages or to reindeer herding farms. This is a very high and good indicator.

Elena Vasilievna remembers a girl who studied well, but after the 9th grade her parents did not let her go to school and she remained in the tundra. It's a very thin line of assessment of such a situation. From the position of us, Internet readers, such an act of parents is unequivocally assessed negatively, but there is another side - traditions. Parents often believe that if a child can count and write, they will not let their children go. This is where the conflict arises, there is a family code and no one can forcefully take a child from a family. But there is a constitution guaranteeing the child's right to education. Often it is Elena Vasilievna who takes children from families with conversations, persuasions, promises to take them under personal care!

Children are collected from tents across the tundra using a Mi-8 helicopter. In case there are flights over the sea - then the Mi-8 MTV.

In case there are flights over the sea - then the Mi-8 MTV.

22 seats, if the helicopter is ordinary, if it is a shift helicopter (with a barrel in the cabin), then there are 14-16 seats.

In addition to two pilots, the crew includes a school teacher, as well as a guide from the indigenous population who knows the routes of reindeer herders in the Tundra. The main problem is to find the chum of the reindeer herding brigade, most of them do not give their coordinates and the search is carried out visually. Often it takes 2-3 hours…

5.

6.

Photos for this report were provided by Lyudmila Viktorovna and Elena Vasilievna from the personal archive.

This is winter, the period when children are taken to the boarding school after the New Year holidays from remote villages of the district: helicopter:

13.

14.

15.

16.

You need to take things with you for six months ... there is no luggage compartment in the helicopter, everything is in the central part of the cabin:

17.

18.

19.

How beautiful!

20.

The experience of Yakutia: what are nomadic schools?

Is it possible to try to create a system of school education without separation from reindeer herders? It turns out yes! Distance education is a joint initiative of tribal communities and the Government of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). It consists in the introduction of a "wandering" teacher into a tribal nomadic community and the creation of nomadic schools. At the legislative level, initiatives were formalized back in 2008. Today in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) there are 13 nomadic schools in 11 uluses (districts) with a contingent of students of 251 children. Nomadic schools are part of tribal communities, in winter they have a room adapted for classes along the nomadic route, and in summer classes are held in tents. In accordance with the law "On nomadic schools of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia)", these educational institutions are organized according to the following basic models: nomadic kindergarten school (4), stationary nomadic school (6), seasonal (summer) nomadic school (3). A feature of the organization of the educational process is the small number of classes, the composition of different ages, the variability of the educational schedule, taking into account the specifics of traditional management, the rotational method of teaching, the increased need for the use of distance learning.

A feature of the organization of the educational process is the small number of classes, the composition of different ages, the variability of the educational schedule, taking into account the specifics of traditional management, the rotational method of teaching, the increased need for the use of distance learning.

I was told about this program by a representative of the Ministry of Education in February, when I was in Yakutia during the traditional annual report of the government to the population of the republic. Representatives of the authorities come to each ulus and report on the work done. It is a most interesting event when there is direct contact between people and the authorities with dialogue, disputes, ideas that are put into practice, and do not remain election promises.

The distance education project and the creation of nomadic schools at pivotal schools (ordinary boarding schools in villages) - initially this was precisely the idea of tribal communities and nomadic tribes themselves, because they are interested in the child spending his childhood in a family and at the same time having the opportunity to get an education. All pivotal schools, even the most remote ones, have satellite internet. As an idea that is under development, the possibility of training the adult members of the community or parents themselves in pedagogy skills and the possibility of quality learning in nomadic conditions is being considered. And now the developments of Yakut teachers in this direction are being adopted by colleagues from across the ocean - from the USA and Canada.

All pivotal schools, even the most remote ones, have satellite internet. As an idea that is under development, the possibility of training the adult members of the community or parents themselves in pedagogy skills and the possibility of quality learning in nomadic conditions is being considered. And now the developments of Yakut teachers in this direction are being adopted by colleagues from across the ocean - from the USA and Canada.

But back to the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, this is what the last days of summer look like when children are taken straight from the reindeer herders' tents:

21.

22.

Parting words to a crying baby before a long separation:

24.

25.

By the way, I was told that the sledge rides perfectly in the summer on moss, even better than in winter.

26.

The boy is 5-6 years old, he manages the nomadic economy very well! And what can city children do at 5-6 years old?! :)

27.

28.