Hearing voices with bipolar

Do people with bipolar disorder hear voices?

Do people with bipolar disorder hear voices? - AmwellDo people with bipolar disorder hear voices?

Yes, some people who have bipolar disorders may have hallucinations and see or hear things that are not present. This can occur during an episode of mania or depression.

Other questions related to Bipolar Disorder

- What is the difference between bipolar I and bipolar II disorder?

Related Content

-

How Virtual Primary Care Can Help Manage Diabetes

A lot of questions can come with receiving a diabetes diagnosis at any age.

But remember, there are many resources available to help you manage your condition. Thanks to the increasing popularity of digital healthcare, it is now easier than ever to book an appointment that works with your schedule, allowing you to stay on top of your health with continuous care. Set up a virtual visit for online diabetes treatment today.

-

There is Hope: Supporting Suicide Prevention Month

September is Suicide Prevention Month – which aims to create hope through action by creating safe spaces for those struggling with the goal of preventing suicide all together. The issue is far reaching. Nearly 46,000 individuals died by suicide in 2020, and 46% of those people had a known mental health condition. Although mental health issues and illnesses, like depression, can lead to suicide, there are many reasons someone may decide to take their own life.

However, most people believe that suicide can be prevented.

However, most people believe that suicide can be prevented. -

Bipolar Disorder

Get the help you need with an online diagnosis, treatment plan, and electronically filed prescriptions from board certified psychiatrists 24/7

-

Eating Disorders: Signs and Symptoms to Look Out For

Eating disorders affect many people. If you have an eating disorder or know someone who does, it’s important to remember that you are not alone. Support is available.

-

Hear from a Psychiatrist: What’s Online Psychiatry Like?

If you've never had an online psychiatry visit before, you might have some questions about how the process works.

Dr. Churi, Amwell’s staff psychiatrist, shares answers and helpful information about telepsychiatry.

Dr. Churi, Amwell’s staff psychiatrist, shares answers and helpful information about telepsychiatry. -

Hear from a Therapist: How to Honor Grief and Find Joy

How do we find a way to carry our grief for our loved one and find joy in the present? This question is one that I often get asked. I am very open about the fact that I lost a son to cancer 20 years ago, and that loss has shaped me into the person and clinician I am today.

Now is the time to try telemedicine!

Amwell® can help you feel better faster. Register now for access to our online doctors 24 hours a day.

ContinuePlease select your insurance provider to continue.

Insurances Select insuranceMy insurance isn't listedAdvantekAetnaAffinityAllegiance Benefit Plan ManagementAlohaCareAmerigroupAmeriHealth CaritasAnthem Blue CrossAnthem Blue Cross and Blue ShieldAPWU Health PlanASR Health BenefitsAvera Health PlansBASDBayCarePlusBCBSM Medicare AdvantageBillings ClinicBlue Care Network of IllinoisBlue Care Network of MichiganBlue Care Network of TexasBlue Cross Blue Shield of AlabamaBlue Cross Blue Shield of ArizonaBlue Cross Blue Shield of ColoradoBlue Cross Blue Shield of ConnecticutBlue Cross Blue Shield of GeorgiaBlue Cross Blue Shield of IndianaBlue Cross Blue Shield of KansasBlue Cross Blue Shield of KentuckyBlue Cross Blue Shield of LouisianaBlue Cross Blue Shield of MaineBlue Cross Blue Shield of MassachusettsBlue Cross Blue Shield of MichiganBlue Cross Blue Shield of MississippiBlue Cross Blue Shield of MissouriBlue Cross Blue Shield of NebraskaBlue Cross Blue Shield of New YorkBlue Cross Blue Shield of North CarolinaBlue Cross Blue Shield of North DakotaBlue Cross Blue Shield of OhioBlue Cross Blue Shield of Rhode IslandBlue Cross Blue Shield of South CarolinaBlue Cross Blue Shield of VermontBlue Cross Blue Shield of VirginiaBlue Cross Blue Shield of WisconsinBlue Cross CaliforniaBlue Cross of IdahoBlue KCBraven HealthCapital Blue CrossCapital Health PlanCarefirst BlueCross BlueShieldColumbia Custom NetworkCook Children's Health PlanCoreSourceDAKOTACAREDeseret Mutual Benefit AdministratorsDuke Health PlansEmpire BCBS New YorkEmpire BlueCrossEnhancedCareMDFidelisFirst Priority HealthFlorida BlueGenesis Health PlansHawaii Medical Service Association (HMSA)Health Alliance Plan (HAP)HealthFirstHealth Plan of NevadaHealth TraditionHealthy BlueHighmark Benefits GroupHighmark Blue Cross Blue ShieldHighmark Blue ShieldHighmark Choice CompanyHighmark Coverage AdvantageHighmark DelawareHighmark Health Insurance CompanyHighmark West VirginiaHorizon Blue Cross Blue Shield of New JerseyHorizon New Jersey HealthHumanaIBC PlanIndependence Blue CrossIU Health PlanMedicaMedical Mutual (MMO)MedStarMemorial Health PlansMeritainMissionary MedicalMVP Health CareMybenefitshomeNorman Health PlansOptum Medical NetworkOscar HealthParamount Health CarePEHP (Public Employees Health Plan)Pekin Life InsurancePeoples HealthPhysicians Health PlanPiedmontPiedmont Community Health PlansPublix BCBS PPOQuestRWJ Barnabas Health PlansSecurity Health PlanSelectHealthSierra Health and LifeSimplySmarthealthStaywellTelehealth OptionsTexas Children's Health PlanTricareTriple-S SaludUMRUnitedHealthcareUnitedHealthcare NevadaUnitedHealthcare OxfordUniversity of Utah Health PlansUPMC Health PlanUW Medicine PlansVibra Health PlanVirginia PremierWEA TrustWebTPAWellcare

Continue ›

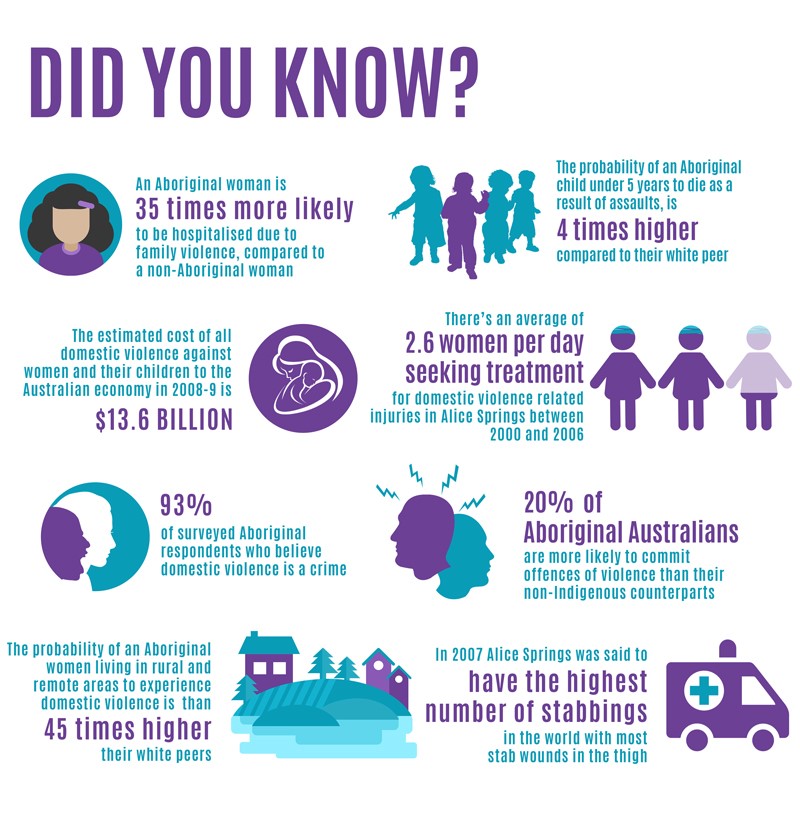

Why They Happen and How to Cope

You can experience visual and auditory hallucinations with bipolar disorder. They can occur during mania or depressive episodes. Treatment and avoiding triggers may help.

They can occur during mania or depressive episodes. Treatment and avoiding triggers may help.

If you have any familiarity with bipolar disorder, you likely know it as a mental health condition defined by “high” and “low” mood states — episodes of mania, hypomania, or depression, to be precise.

How you experience these mood episodes can depend on different factors. Episodes might vary in length and severity, and you could even notice changes in mood symptoms over time.

Yet many people don’t realize one important fact about mood episodes: They can also involve hallucinations.

Hallucinations tend to happen more frequently with the manic episodes that characterize bipolar I, though they can also appear during depressive episodes.

Hallucinations also separate hypomania from mania. If you hallucinate during what otherwise feels like hypomania, the episode automatically meets criteria for mania, notes the new edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).

Hallucinations can feel confusing, even terrifying — especially when you don’t know what causes them. But they’re more common than you think.

Below, we’ll explore bipolar hallucinations in depth, plus offer some guidance on getting support.

Hallucinations do often happen as a symptom of psychosis, or a disconnect from reality. Other main symptoms of psychosis include:

- delusions

- self-isolation or withdrawal

- disorganized speech and thoughts

- feelings of suspiciousness and confusion

Psychosis is a symptom, not a mental health condition in and of itself, and it’s somewhat common with bipolar disorder.

In fact, older research from 2005 suggests that anywhere from 50 to 75 percent of people living with bipolar disorder will experience symptoms of psychosis during some mood episodes. These symptoms can lead to a diagnosis of bipolar disorder with psychotic features.

Two different types of psychosis can happen with bipolar disorder:

- Mood congruent psychosis.

The symptoms you experience align with the mood episode. You might hear people laughing and talking or cheering you on during an episode of mania, for example. This type is more common.

The symptoms you experience align with the mood episode. You might hear people laughing and talking or cheering you on during an episode of mania, for example. This type is more common. - Mood incongruent psychosis. These symptoms conflict with your mood state. In a state of depression, for example, you might believe you’re actually someone famous, or hear a voice telling you that you’re invincible.

Learn more about bipolar psychosis.

Although some people living with bipolar disorder do experience psychosis, it’s possible to hallucinate with bipolar disorder without ever having any other symptoms of psychosis.

In short, hallucinating doesn’t always mean you’re dealing with psychosis.

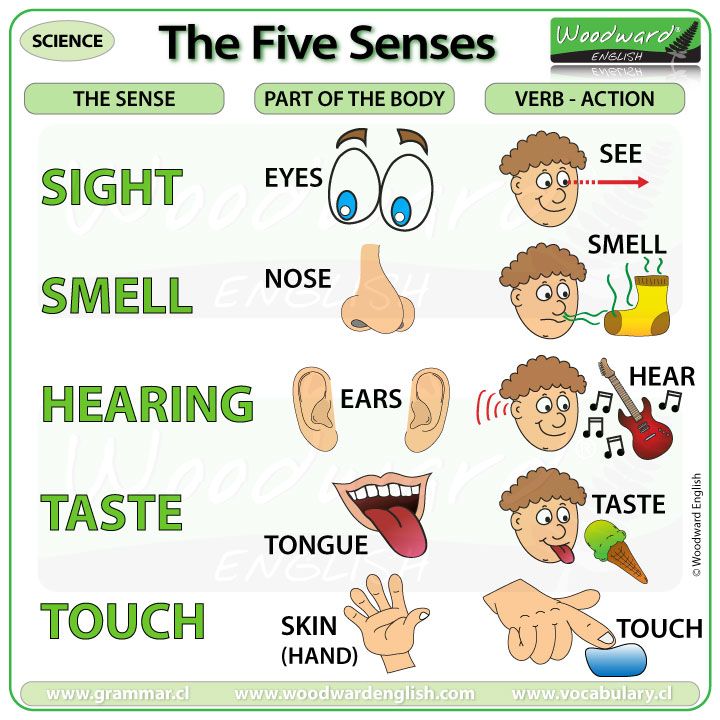

Hallucinations can involve any of your senses, though usually just one at a time.

Three types of hallucinations appear most commonly with bipolar disorder:

- auditory, or hearing things no one else can hear

- somatic, or feeling something you can’t see or hear

- visual, or seeing something no one else can see

It’s also possible to hallucinate tastes or smells, but older research suggests these hallucinations usually happen alongside delusions.

Often, hallucinations are fleeting: You might briefly see flashing lights, feel someone touch your hand, or hear music playing.

They can also be longer and more detailed: You could hear voices having a conversation, or see a long-departed loved one walking past your house.

Experts don’t fully understand why some people with bipolar disorder experience hallucinations and others don’t.

They do know hallucinations can happen for plenty of different reasons, including chronic medical conditions, head injuries, and seizures, just to name a few.

As for hallucinations that happen with bipolar disorder? Well, potential causes can still vary pretty widely. A few recognized triggers include:

Stress

Any kind of stress can have an impact on mental and physical well-being. This includes both ordinary life stress and the added strain that can happen as a result of living with a mental health condition.

Common sources of stress include:

- grief

- traumatic experiences

- relationship conflict or breakup

- family problems

- health concerns

- workplace or financial issues

You might be more likely to hallucinate when under a lot of daily stress, or feeling overwhelmed and anxious about something in particular.

In some cases, stress can also serve as a trigger for mood episodes.

Lack of sleep

During manic episodes, you might feel as if you need less sleep — after just 2 or 3 hours, you wake up feeling rested and ready to go. Of course, you still actually need that sleep you’re missing out on.

Sleep deprivation is a key cause of hallucinations, so regularly getting fewer than 6 or 7 hours of sleep each night could increase your chances of hallucinating and make some mood symptoms worse.

Not getting enough rest can also prompt manic episodes, not to mention contribute to anxiety, depression, and plenty of other health concerns. Most adults need between 7 and 9 hours of sleep each night for optimal health.

Medication side effects

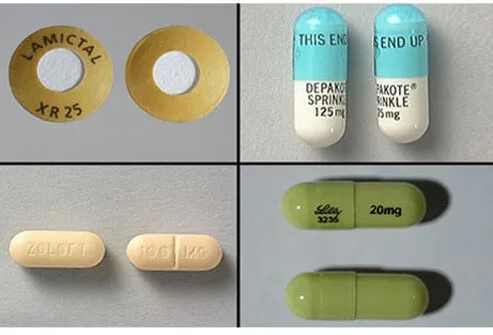

Hallucinations may happen as a side effect of certain medications, including some antidepressants and antipsychotics used to treat bipolar disorder:

- bupropion

- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- tricyclic antidepressants

- olanzapine (Zyprexa)

If you hallucinate while taking antidepressants or any other medication that lists hallucinations as a potential side effect, let your prescriber know right away. They can help you monitor your symptoms and switch your medication or adjust the dose, if needed.

They can help you monitor your symptoms and switch your medication or adjust the dose, if needed.

Alcohol and other substances

Hallucinations can happen as a result of:

- drinking heavily

- going through withdrawal

- taking ecstasy, amphetamines, cocaine, or hallucinogenics

Some people also experience hallucinations, along with paranoia and other symptoms of psychosis, when using cannabis.

It’s not uncommon to use alcohol and substances to cope with emotional turmoil and distress, especially when living with a lifelong condition like bipolar disorder. Mood episodes can feel overwhelming, even unbearable, and it’s not always easy to manage them without wanting to numb that pain.

Keep in mind, though, that these substances only provide temporary relief and may even worsen mental health symptoms. Working with a therapist can help you explore more long-lasting methods of relief.

Postpartum psychosis

Some people experience hallucinations and other symptoms of psychosis after childbirth.

Postpartum psychosis is rare, but it’s more common in people with a history of bipolar disorder — and it always represents a medical emergency.

Connect with your care team right away if you’ve recently given birth and experience hallucinations, along with:

- a general sense of confusion or disorientation

- sudden shifts in mood

- thoughts of violence or self-harm

- fears that someone wants to hurt your baby, or you do

It’s always safest to let your doctor know about hallucinations after childbirth, even if you don’t notice other signs of psychosis. They can help you watch for other symptoms and offer support with getting the right treatment.

Other potential causes

Medical causes of hallucinations include:

- seizures

- epilepsy

- head injuries

- neurological conditions

- migraine

- high fevers

- hearing or vision problems

It’s also possible to hallucinate:

- during periods of isolation

- as part of a spiritual or religious experience

Since hallucinations can happen for so many reasons, it may take some time to narrow down what’s causing yours.

Telling your therapist or other healthcare professional everything you can about not just the hallucination, but how you felt beforehand and any other symptoms you noticed, can make it easier for them to arrive at the right diagnosis:

- Maybe you only notice hallucinations when you haven’t slept well for several days, or when your mood is very low.

- If you also report head pain or other physical symptoms, your therapist may encourage you to connect with a healthcare provider to rule out underlying health conditions.

You know your symptoms best, so if the suggested diagnosis doesn’t feel right, it’s important to let them know.

Distinct mood episodes nearly always suggest bipolar disorder, especially when you don’t experience any other symptoms of psychosis or experience any “break” from reality. The specific pattern, type, and length of your mood episodes will help your healthcare professional determine the most likely subtype.

Keep in mind it’s entirely possible to have more than one mental health condition at the same time. Anxiety, for example, commonly occurs with bipolar disorder — and many people living with anxiety do report hearing voices.

Anxiety, for example, commonly occurs with bipolar disorder — and many people living with anxiety do report hearing voices.

When you have other symptoms of psychosis

Your symptoms could meet criteria for bipolar disorder with psychotic features, but they could better fit a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder.

This mental health condition involves mixed symptoms of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. But with schizoaffective disorder, you’ll also experience psychosis when you aren’t having a mood episode.

To diagnose this condition, a mental health professional will help you track when psychosis appears and note whether it’s present during just your mood episodes, or at other times, too.

Typically, bipolar disorder requires professional treatment, though treatment may require different approaches:

- during mood episodes

- during a manic episode versus a depressive episode

- once mood symptoms start to improve

- when you aren’t experiencing any symptoms

During a mood episode, treatment generally focuses on improving severe symptoms with medications, including:

- mood stabilizers

- antipsychotics

- benzodiazepines

After a mood episode, treatment generally aims to reduce future mood episodes and help you maintain a euthymic (symptom-free) mood state.

To achieve this goal, you might work with your treatment team to:

- find medication dosages that work well, with few side effects

- learn helpful ways to manage stress

- address hallucinations, and any other concerning symptoms, in therapy

- explore lifestyle changes and self-care habits to improve sleep, physical health, and emotional well-being

- discuss complementary treatments, like light therapy, acupuncture, or mindfulness practices like meditation and yoga

These strategies can go a long way toward improving all symptoms of bipolar disorder — including hallucinations that happen with psychosis and those that relate to sleep loss or stress.

Without treatment, though, symptoms often get worse. You could have more frequent mood episodes, and you might also notice more hallucinations.

If you live with bipolar disorder, it’s always a good idea to work with a therapist who has experience treating the condition.![]() Therapists trained to recognize the often complex presentation of mood episodes can identify the correct diagnosis and help you find the most effective treatment.

Therapists trained to recognize the often complex presentation of mood episodes can identify the correct diagnosis and help you find the most effective treatment.

Get tips to find the right therapist.

When treatment doesn’t seem to help

Perhaps your current medication hasn’t done much for your symptoms. Or maybe you think it’s causing your hallucinations.

You’ll want to mention this to your psychiatrist or doctor right away, but it’s best to keep taking the medication unless they tell you otherwise. Abruptly stopping a medication can lead to serious side effects.

It’s also important to continue taking any prescribed medications, even when you have no mood symptoms at all. Stopping the medication could trigger a mood episode.

Concerned about side effects? Ask your care team about reducing your dose or trying another medication.

Mood episodes remain the defining feature of bipolar disorder, but the condition can involve hallucinations, too.

Sure, they might feel less frightening when you recognize them as hallucinations and never lose touch with reality. But it’s entirely natural to feel unsettled, confused, or even stressed, which could make bipolar symptoms worse.

A therapist can offer more insight on potential causes and help you take steps to find the most effective treatment.

Crystal Raypole writes for Healthline and Psych Central. Her fields of interest include Japanese translation, cooking, natural sciences, sex positivity, and mental health, along with books, books, and more books. In particular, she’s committed to helping decrease stigma around mental health issues. She lives in Washington with her son and a lovably recalcitrant cat.

neuroscientist talks about the nature of auditory hallucinations - T&P

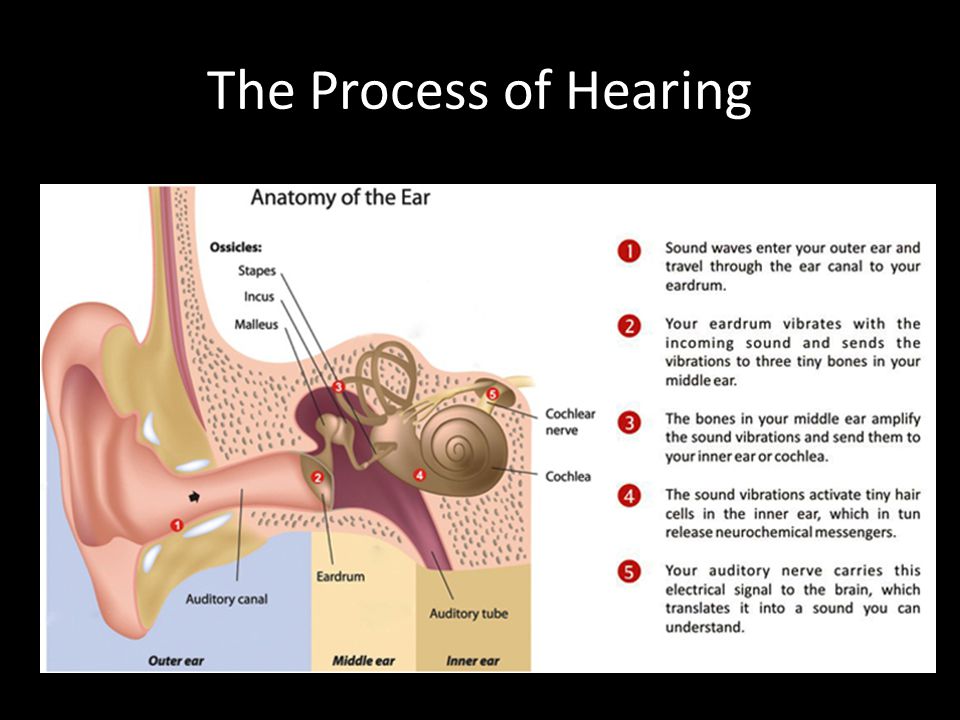

Hallucinations are what occur in the absence of an external stimulus, but are perceived as real. They can be associated with all the senses, that is, they can be visual, tactile and even olfactory.

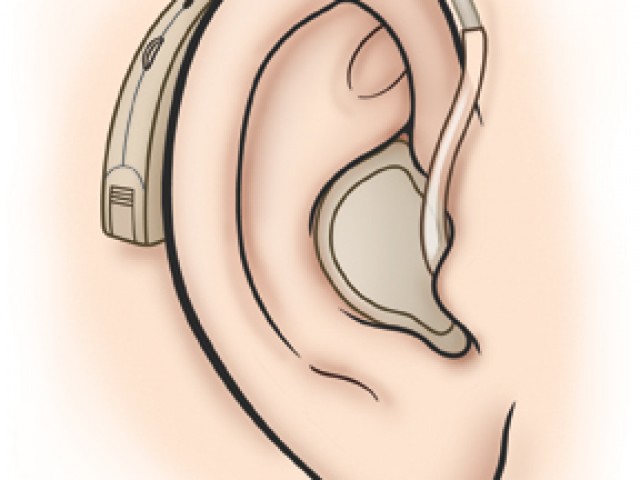

Probably the most common type of hallucination is when a person "hears voices". They are called auditory verbal hallucinations. T&P continues a special project with New with the translation of an article by neuroscientist Paul Allen, published on the Serious Science website, about auditory hallucinations and the nature of their occurrence.

Probably the most common type of hallucination is when a person "hears voices". They are called auditory verbal hallucinations. T&P continues a special project with New with the translation of an article by neuroscientist Paul Allen, published on the Serious Science website, about auditory hallucinations and the nature of their occurrence.

Definition

Although auditory hallucinations are commonly associated with mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder, they are not always a sign of illness. In some cases, they can be caused by lack of sleep; Marijuana and stimulant drugs can also cause perceptual disturbances in some people. It has been experimentally proven that hallucinations can occur due to a prolonged absence of sensory stimuli: in the 1960s, experiments were conducted (which would now be impossible for ethical reasons), during which people were kept in dark rooms without sound. In the end, people began to see and hear things that were not there in reality. So hallucinations can occur both in patients and in mentally healthy people.

So hallucinations can occur both in patients and in mentally healthy people.

Research on the nature of this phenomenon has been going on for quite some time: psychiatrists and psychologists have been trying to understand the causes and phenomenology of auditory hallucinations for about a hundred years (and maybe longer). In the last three decades, it became possible to use encephalograms, which helped researchers of that time to understand what was happening in the brain during moments of auditory hallucinations. And now we can look at its different areas involved in these periods using functional magnetic resonance scanning or positron tomography. These technologies have helped psychologists and psychiatrists develop models of auditory hallucinations in the brain, mostly related to the function of language and speech.

Proposed theories for the mechanisms of auditory hallucinations

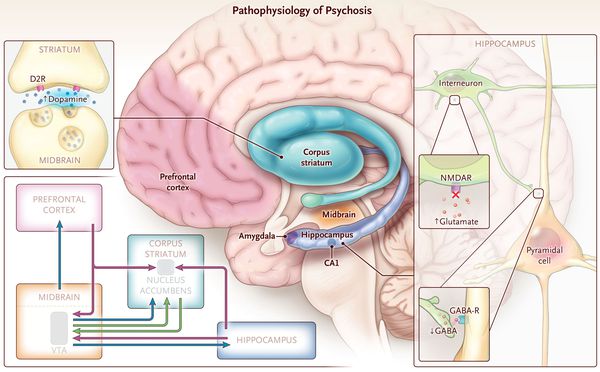

Some studies have shown that when patients experience auditory hallucinations, that is, they hear voices, activity in a part of their brain called Broca's area increases. This area is located in the small frontal lobe of the brain and is responsible for speech production: when you speak, it is Broca's area that works. One of the first to investigate this phenomenon were professors Philip McGuire and Suchy Shergill from King's College London. They noticed that their patients' Broca's area was more active during auditory hallucinations compared to when the voices were silent. This suggests that auditory hallucinations are produced by the speech and language centers of our brain. The results of these studies led to the creation of internal speech models of auditory hallucinations.

This area is located in the small frontal lobe of the brain and is responsible for speech production: when you speak, it is Broca's area that works. One of the first to investigate this phenomenon were professors Philip McGuire and Suchy Shergill from King's College London. They noticed that their patients' Broca's area was more active during auditory hallucinations compared to when the voices were silent. This suggests that auditory hallucinations are produced by the speech and language centers of our brain. The results of these studies led to the creation of internal speech models of auditory hallucinations.

When we think about something, we generate inner speech - an inner voice that voices our thinking. For example, when we ask the question "What am I going to eat for lunch?" or “What will the weather be like tomorrow?”, we generate inner speech and are believed to activate Broca’s area. But how does this inner speech begin to be perceived by the brain as external, not coming from itself? According to internal speech models of auditory verbal hallucinations, such voices are thoughts generated inside the consciousness or internal speech, somehow incorrectly defined as external, alien. More complex models of the process of how we track our own inner speech follow from this.

More complex models of the process of how we track our own inner speech follow from this.

© Kate MacDowell

English neuroscientist and neuropsychologist Chris Frith and others have suggested that when we engage in thinking and internal speech, Broca's area sends a signal to an area of our auditory cortex called Wernicke's area. This signal contains information that the speech we perceive is generated by us. This is because the transmitted signal is supposed to dampen the neuronal activity of the sensory cortex, so it is not activated as much as it is from external stimuli, such as someone talking to you. This model is known as the self-monitoring model, and it suggests that people with auditory hallucinations are deficient in this process, causing them to be unable to distinguish between internal and external speech. Although the evidence for this theory is rather weak at the moment, it is certainly one of the most influential models of auditory hallucinations that have emerged over the past 20 to 30 years.

Consequences of hallucinations

About 70% of patients with schizophrenia hear voices to some extent. They are treatable, but not always. Usually (though not in all cases) votes have a negative impact on the quality of life and health. For example, patients who hear voices and do not respond to treatment have an increased risk of suicide (sometimes voices call for self-harm). One can imagine how hard it is for people even in everyday situations, when they constantly hear humiliating and insulting words addressed to them.

But auditory hallucinations do not only occur in people with mental disorders. Moreover, these voices are not always evil. Thus, Marius Romm and Sandra Escher lead a very active "Society of Hearing Voices" - a movement that speaks about their positive aspects and fights against their stigmatization. Many people who hear voices live active and happy lives, so we cannot assume that voices are inherently bad. Yes, they are often associated with aggressive, paranoid and anxious behavior of patients, but it may be due to emotional distress, and not the presence of voices. Not surprisingly, the anxiety and paranoia that are often at the core of mental illness show up in what these voices say. But, as already mentioned, many people without a psychiatric diagnosis state that they hear voices, and for them this can be a positive experience, since voices can calm or even suggest the direction in which to move in life. Professor Iris Sommer from the Netherlands has carefully studied this phenomenon: the healthy people she studied, hearing voices, described them as something positive, useful and giving self-confidence.

Not surprisingly, the anxiety and paranoia that are often at the core of mental illness show up in what these voices say. But, as already mentioned, many people without a psychiatric diagnosis state that they hear voices, and for them this can be a positive experience, since voices can calm or even suggest the direction in which to move in life. Professor Iris Sommer from the Netherlands has carefully studied this phenomenon: the healthy people she studied, hearing voices, described them as something positive, useful and giving self-confidence.

Treating hallucinations

People diagnosed with schizophrenia are usually treated with antipsychotic medications that block postsynaptic dopamine receptors in the striatum, the brain's striatum. Antipsychotics are effective in many cases: as a result of treatment, psychotic symptoms subside, especially auditory hallucinations and mania. Some patients, however, do not respond well to antipsychotics. Approximately 25-30% of patients who hear voices are almost unaffected by drugs. Antipsychotics also have serious side effects, so these medications are not suitable for all patients.

Antipsychotics also have serious side effects, so these medications are not suitable for all patients.

For other methods, there are many options for non-pharmacological treatment. Their degree of effectiveness also varies. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Its use for the treatment of psychosis is somewhat controversial, as many researchers believe that it has little effect on the symptoms and overall outcome of the disease. But there are types of CBT designed specifically for patients who hear voices. This therapy is usually aimed at changing the patient's attitude towards the voice so that the latter is perceived as less negative and unpleasant. The effectiveness of this treatment remains in question.

I am currently leading a study at King's College London to see if we can teach patients to self-regulate neural activity in the auditory cortex. This is achieved with the help of neural feedback, which is sent in real time using MRI. An MRI scanner is used to measure the signal coming from the auditory cortex. This signal is then sent back to the patient via a visual interface, which the patient must learn to control (that is, move the lever up and down). It is expected that we will be able to teach voice-hearing patients to control the activity of their auditory cortex, which in turn may allow them to better control their voices. Researchers are not yet sure whether this method will be clinically effective, but some preliminary data will be available in the next few months.

This is achieved with the help of neural feedback, which is sent in real time using MRI. An MRI scanner is used to measure the signal coming from the auditory cortex. This signal is then sent back to the patient via a visual interface, which the patient must learn to control (that is, move the lever up and down). It is expected that we will be able to teach voice-hearing patients to control the activity of their auditory cortex, which in turn may allow them to better control their voices. Researchers are not yet sure whether this method will be clinically effective, but some preliminary data will be available in the next few months.

Population prevalence

About 24 million people worldwide are living with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and about 60% or 70% of them have heard voices. There is evidence that from 5% to 10% of the population without a psychiatric diagnosis at some point in their lives also heard them. Some of us sometimes thought that someone was calling us by name, and then it turned out that there was no one around. So there is evidence that auditory hallucinations are more common than we think, although accurate epidemiological statistics are hard to come by.

So there is evidence that auditory hallucinations are more common than we think, although accurate epidemiological statistics are hard to come by.

The most famous person who heard voices was probably Joan of Arc. From modern history, one can recall Syd Barrett, the founder of the Pink Floyd group, who suffered from schizophrenia and auditory hallucinations. But, again, someone can draw inspiration for art from voices, and some even experience musical hallucinations - something like vivid auditory images - but scientists still doubt whether they can be equated with hallucinations.

Unanswered questions

Science currently does not have a clear answer to the question of what happens in the brain when a person hears voices. Another problem is that researchers do not yet know why people perceive them as aliens coming from an external source. It is important to try to understand the phenomenological aspect of what exactly people experience when they hear a voice. For example, when tired or on stimulants, they may experience hallucinations, but not necessarily perceive them as coming from outside. The question is why do people lose the sense of their own activity when they hear voices. Even if we believe that the cause of auditory hallucinations is an excessive activity of the auditory cortex, why do people still think that God, a secret agent or an alien is talking to them? It is also important to study the belief systems that people build around their voices.

For example, when tired or on stimulants, they may experience hallucinations, but not necessarily perceive them as coming from outside. The question is why do people lose the sense of their own activity when they hear voices. Even if we believe that the cause of auditory hallucinations is an excessive activity of the auditory cortex, why do people still think that God, a secret agent or an alien is talking to them? It is also important to study the belief systems that people build around their voices.

The content of auditory hallucinations and their source is another problem: do these voices come from inner speech or are they stored memories? What can be said with certainty is that this sensory experience involves the activation of the auditory cortex in the speech and language areas. This does not tell us anything about the emotional content of these messages, which are often negative, which, in turn, implies that the reason may also be in problems in processing emotional information that arise in the brain. In addition, two people can experience hallucinations very differently, which means that the brain mechanisms involved can also be very different.

In addition, two people can experience hallucinations very differently, which means that the brain mechanisms involved can also be very different.

What people with schizophrenia, psychosis and other illnesses think and feel

Mental illnesses are more common than people think. According to statistics compiled by experts from the World Health Organization, in Europe alone, every fourth person faced some kind of mental health problem.

Tags:

mental health

Mental disorders

Talking about mental problems and diagnoses is not accepted - this topic is highly stigmatized. People with psychiatric diagnoses rarely discuss their feelings and their feelings, even with close friends, and among those around it, the opinion is quite popular that any psychiatric diagnosis is necessarily associated with inappropriate behavior, aggression, and cruelty.

In an attempt to understand what people with different psychiatric diagnoses really think and feel, we studied their own opinions.

Psychopathy

- My emotional stability and ability to remain calm in stressful situations has repeatedly surprised others. The media broadcasts that every psychopath is just some kind of killer. Everything is relative. I'm definitely not a murderer, although, of course, murder is one of the possible ways to solve any problem. But even a psychopath knows that this is an extreme solution.

- Actually, I live just like everyone else. I think that psychopaths are more conscious than many because they think before they say something. I adapt to people, I say what they want to hear, not what they should. I think that many behave like psychopaths, but in fact they do not yet know about their diagnosis. It is widely believed that psychopaths lack empathy and do not know how to interact with others. Maybe this is so, I can’t speak for others, but personally I am able to give out the expected reactions.

Social interaction is very simple because people are so predictable.

Social interaction is very simple because people are so predictable. - We are able to love. I have those whom I love. It is possible that I feel this somehow differently than healthy people, but this is not a reason to belittle people like me. We are not robots, we are people.

- The life of most people is no different from my life. Without empathy, it is easier for me to work, although it may be a little more difficult for me than for healthy people. I am emotionally stable and mood swings are minimal and very rare. I sharpened my pencil, I charged my phone, my grandfather died, I discovered milk, I swept the floor, I won $1,000 in the lottery - it's about the same thing emotionally for me.

ADVERTISING - CONTINUED BELOW

Bipolar disorder

- I think that anyone with bipolar disorder feels differently at different times. When I am depressed, it seems to me that I have died, but my body lives on.

Perhaps even dying would be better than feeling dead. In the period of mania, everything changes: it seems to me that I become much smarter and prettier, and the energy is in full swing.

Perhaps even dying would be better than feeling dead. In the period of mania, everything changes: it seems to me that I become much smarter and prettier, and the energy is in full swing. - Feelings are difficult to describe, those who have not experienced it will not be able to understand. You have to constantly go through cycles of changing moods. I have a rare case - I have been suffering from bipolar disorder all my life and I don’t know what happens otherwise. For most people, bipolar disorder appears at puberty or at a young age, they know that a normal life exists. During periods of depression, doing any household chores is very difficult. It was difficult for me to sleep, I hardly ate. It seems that no one loves you, and at the same time you are absolutely helpless, because no one needs you.

Depression

- I lay in bed until lunch without any food, didn't get up, but didn't sleep either. This was not due to laziness, I just physically and mentally could not get up.

I mentally shouted to myself: “Get up already!”, But the body continued to lie, and in my head it sounded: “Shut up!”

I mentally shouted to myself: “Get up already!”, But the body continued to lie, and in my head it sounded: “Shut up!” - I felt a lot of things. Once upon a time, I just acted mechanically - getting out of bed, brushing my teeth, getting dressed, going where I had to go. The number of emotions that accompanied this whole process could be compared to the number of emotions that the droid experiences. On bad days, I just lay in my room, minimizing interaction with the outside world. The world seemed awfully big. Everything was huge. The size of the room was intimidating. I was afraid to breathe. A bad day is a mixture of anxiety and depression.

- Depression for me was a period when I hoped every day that I would fall ill with some kind of fatal disease and die, and die with dignity, and my loved ones who love me would not know how worthless I was. I did not hope for a better future, where there was happiness and joy, all my thoughts were only about death.

- Depression amplifies my negative emotions, making them seem even more terrible.