Lamictal and prozac for bipolar

Lamictal and Prozac Interactions Checker

This report displays the potential drug interactions for the following 2 drugs:

- Lamictal (lamotrigine)

- Prozac (fluoxetine)

Edit list (add/remove drugs)

- Consumer

- Professional

Interactions between your drugs

Treatment with FLUoxetine may occasionally cause blood sodium levels to get too low, a condition known as hyponatremia, and using it with some anticonvulsants can increase that risk. In addition, FLUoxetine can cause seizures in susceptible patients, which may reduce the effectiveness of medications that are used to control seizures such as lamoTRIgine. Talk to your doctor if you have any questions or concerns. Your doctor may be able to prescribe alternatives that do not interact, or you may need a dose adjustment or more frequent monitoring to safely use both medications. You should seek medical attention if you experience nausea, vomiting, headache, lethargy, irritability, difficulty concentrating, memory impairment, confusion, muscle spasm, weakness or unsteadiness, as these may be symptoms of hyponatremia.

More severe cases may lead to hallucination, fainting, seizure, coma, and even death. Also let your doctor know if you develop seizures or experience an increase in seizures during treatment with FLUoxetine. Additionally, because these medications may cause dizziness, drowsiness, and impairment in judgment, reaction speed and motor coordination, you should avoid driving or operating hazardous machinery until you know how they affect you. It is important to tell your doctor about all other medications you use, including vitamins and herbs. Do not stop using any medications without first talking to your doctor.

Switch to professional interaction data

Drug and food interactions

Alcohol can increase the nervous system side effects of FLUoxetine such as dizziness, drowsiness, and difficulty concentrating. Some people may also experience impairment in thinking and judgment. You should avoid or limit the use of alcohol while being treated with FLUoxetine. Do not use more than the recommended dose of FLUoxetine, and avoid activities requiring mental alertness such as driving or operating hazardous machinery until you know how the medication affects you. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist if you have any questions or concerns.

Talk to your doctor or pharmacist if you have any questions or concerns.

Switch to professional interaction data

Alcohol can increase the nervous system side effects of lamoTRIgine such as dizziness, drowsiness, and difficulty concentrating. Some people may also experience impairment in thinking and judgment. You should avoid or limit the use of alcohol while being treated with lamoTRIgine. Do not use more than the recommended dose of lamoTRIgine, and avoid activities requiring mental alertness such as driving or operating hazardous machinery until you know how the medication affects you. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist if you have any questions or concerns.

Switch to professional interaction data

Therapeutic duplication warnings

No warnings were found for your selected drugs.

Therapeutic duplication warnings are only returned when drugs within the same group exceed the recommended therapeutic duplication maximum.

See also

- Lamictal drug interactions

- Lamictal uses and side effects

- Prozac drug interactions

- Prozac uses and side effects

- Drug Interactions Checker

Report options

Share by QR CodeQR code containing a link to this page

Drug Interaction Classification

| Major | Highly clinically significant. Avoid combinations; the risk of the interaction outweighs the benefit. |

|---|---|

| Moderate | Moderately clinically significant. Usually avoid combinations; use it only under special circumstances. |

| Minor | Minimally clinically significant. Minimize risk; assess risk and consider an alternative drug, take steps to circumvent the interaction risk and/or institute a monitoring plan. |

| Unknown | No interaction information available. |

Further information

Always consult your healthcare provider to ensure the information displayed on this page applies to your personal circumstances.

Medical Disclaimer

A 7-week, randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination versus lamotrigine in the treatment of bipolar I depression

Save citation to file

Format: Summary (text)PubMedPMIDAbstract (text)CSV

Add to Collections

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Name your collection:

Name must be less than 100 characters

Choose a collection:

Unable to load your collection due to an error

Please try again

Add to My Bibliography

- My Bibliography

Unable to load your delegates due to an error

Please try again

Your saved search

Name of saved search:

Search terms:

Test search terms

Email: (change)

Which day? The first SundayThe first MondayThe first TuesdayThe first WednesdayThe first ThursdayThe first FridayThe first SaturdayThe first dayThe first weekday

Which day? SundayMondayTuesdayWednesdayThursdayFridaySaturday

Report format: SummarySummary (text)AbstractAbstract (text)PubMed

Send at most: 1 item5 items10 items20 items50 items100 items200 items

Send even when there aren't any new results

Optional text in email:

Create a file for external citation management software

Randomized Controlled Trial

. 2006 Jul;67(7):1025-33.

2006 Jul;67(7):1025-33.

doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0703.

Eileen B Brown 1 , Susan L McElroy, Paul E Keck Jr, Ahmed Deldar, David H Adams, Mauricio Tohen, Douglas J Williamson

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 Lilly Research Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 16889444

- DOI: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0703

Randomized Controlled Trial

Eileen B Brown et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006 Jul.

. 2006 Jul;67(7):1025-33.

2006 Jul;67(7):1025-33.

doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0703.

Authors

Eileen B Brown 1 , Susan L McElroy, Paul E Keck Jr, Ahmed Deldar, David H Adams, Mauricio Tohen, Douglas J Williamson

Affiliation

- 1 Lilly Research Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 16889444

- DOI: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0703

Abstract

Objective: Determine the efficacy and tolerability of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC) for treatment of acute bipolar I depression compared with lamotrigine.

Method: The 7-week, acute phase of a randomized, double-blind study compared OFC (6/25, 6/50, 12/25, or 12/50 mg/day; N = 205) with lamotrigine ([LMG] titrated to 200 mg/day; N = 205) in patients with DSM-IV-diagnosed bipolar I disorder, depressed. The study was conducted from November 2003 to August 2004.

Results: Completion rates were similar between treatments (OFC, 66.8% vs. LMG, 65.4%; p = .835). OFC-treated patients had significantly greater improvement than lamotrigine-treated patients in change from baseline across the 7-week treatment period on the Clinical Global Impressions-Severity of Illness scale (primary outcome) (p = .002, effect size = 0.26), Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (p = .002, effect size = 0.24), and Young Mania Rating Scale total scores (p = .001, effect size = 0.24). Response rates did not significantly differ between groups when defined as > or = 50% reduction in MADRS score (OFC, 68. 8% vs. LMG, 59.7%; p = .073). Time to response was significantly shorter for OFC-treated patients (median days [95% CI] = OFC, 17 [14 to 22] vs. LMG, 23 [21 to 34]; p = .010). There was a significant difference in incidence of "suicidal and self-injurious behavior" adverse events (OFC, 0.5% vs. LMG, 3.4%; p = .037). Somnolence, increased appetite, dry mouth, sedation, weight gain, and tremor occurred more frequently (p < .05) in OFC-treated patients than lamotrigine-treated patients. Weight, total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels were significantly elevated in OFC-treated patients compared with lamotrigine-treated patients (all p < or = .001).

8% vs. LMG, 59.7%; p = .073). Time to response was significantly shorter for OFC-treated patients (median days [95% CI] = OFC, 17 [14 to 22] vs. LMG, 23 [21 to 34]; p = .010). There was a significant difference in incidence of "suicidal and self-injurious behavior" adverse events (OFC, 0.5% vs. LMG, 3.4%; p = .037). Somnolence, increased appetite, dry mouth, sedation, weight gain, and tremor occurred more frequently (p < .05) in OFC-treated patients than lamotrigine-treated patients. Weight, total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels were significantly elevated in OFC-treated patients compared with lamotrigine-treated patients (all p < or = .001).

Conclusions: Patients with acute bipolar I depression had statistically significantly greater improvement in depressive and manic symptoms, more treatment-emergent adverse events, greater weight gain, and some elevated metabolic factors with OFC than lamotrigine. Treatment differences were of modest size.

Treatment differences were of modest size.

Similar articles

-

Olanzapine/fluoxetine combination vs. lamotrigine in the 6-month treatment of bipolar I depression.

Brown E, Dunner DL, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Adams DH, Degenhardt E, Tohen M, Houston JP. Brown E, et al. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009 Jul;12(6):773-82. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009735. Epub 2008 Dec 11. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009. PMID: 19079815 Clinical Trial.

-

A 24-week open-label extension study of olanzapine-fluoxetine combination and olanzapine monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar depression.

Corya SA, Perlis RH, Keck PE Jr, Lin DY, Case MG, Williamson DJ, Tohen MF. Corya SA, et al.

J Clin Psychiatry. 2006 May;67(5):798-806. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0514. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006. PMID: 16841630 Clinical Trial.

J Clin Psychiatry. 2006 May;67(5):798-806. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0514. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006. PMID: 16841630 Clinical Trial. -

Analyses of treatment-emergent mania with olanzapine/fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar depression.

Keck PE Jr, Corya SA, Altshuler LL, Ketter TA, McElroy SL, Case M, Briggs SD, Tohen M. Keck PE Jr, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005 May;66(5):611-6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0511. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005. PMID: 15889948 Clinical Trial.

-

[Antipsychotics in bipolar disorders].

Vacheron-Trystram MN, Braitman A, Cheref S, Auffray L. Vacheron-Trystram MN, et al. Encephale. 2004 Sep-Oct;30(5):417-24. doi: 10.1016/s0013-7006(04)95456-5.

Encephale. 2004. PMID: 15627046 Review. French.

Encephale. 2004. PMID: 15627046 Review. French. -

Olanzapine plus fluoxetine for bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Silva MT, Zimmermann IR, Galvao TF, Pereira MG. Silva MT, et al. J Affect Disord. 2013 Apr 25;146(3):310-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.001. Epub 2012 Dec 4. J Affect Disord. 2013. PMID: 23218251 Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Efficacy and safety of lamotrigine in the treatment of bipolar disorder across the lifespan: a systematic review.

Besag FMC, Vasey MJ, Sharma AN, Lam ICH. Besag FMC, et al. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2021 Oct 8;11:20451253211045870.

doi: 10.1177/20451253211045870. eCollection 2021. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2021. PMID: 34646439 Free PMC article. Review.

doi: 10.1177/20451253211045870. eCollection 2021. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2021. PMID: 34646439 Free PMC article. Review. -

Bipolar depression: a major unsolved challenge.

Baldessarini RJ, Vázquez GH, Tondo L. Baldessarini RJ, et al. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2020 Jan 6;8(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s40345-019-0160-1. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2020. PMID: 31903509 Free PMC article. Review.

-

Pharmacological treatment of adult bipolar disorder.

Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Vázquez GH. Baldessarini RJ, et al. Mol Psychiatry. 2019 Feb;24(2):198-217. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0044-2. Epub 2018 Apr 20. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. PMID: 29679069 Review.

-

Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder.

Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Bond DJ, Frey BN, Sharma V, Goldstein BI, Rej S, Beaulieu S, Alda M, MacQueen G, Milev RV, Ravindran A, O'Donovan C, McIntosh D, Lam RW, Vazquez G, Kapczinski F, McIntyre RS, Kozicky J, Kanba S, Lafer B, Suppes T, Calabrese JR, Vieta E, Malhi G, Post RM, Berk M. Yatham LN, et al. Bipolar Disord. 2018 Mar;20(2):97-170. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12609. Epub 2018 Mar 14. Bipolar Disord. 2018. PMID: 29536616 Free PMC article.

-

The Black Book of Psychotropic Dosing and Monitoring.

Schatzberg AF, Charles D. Schatzberg AF, et al. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2018 Jan 15;48(1):64-153. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2018. PMID: 29382960 Free PMC article. Review. No abstract available.

See all "Cited by" articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

Substances

Full text links

Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Cite

Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Send To

Modern therapy of the depressive phase in bipolar affective disorder (review)

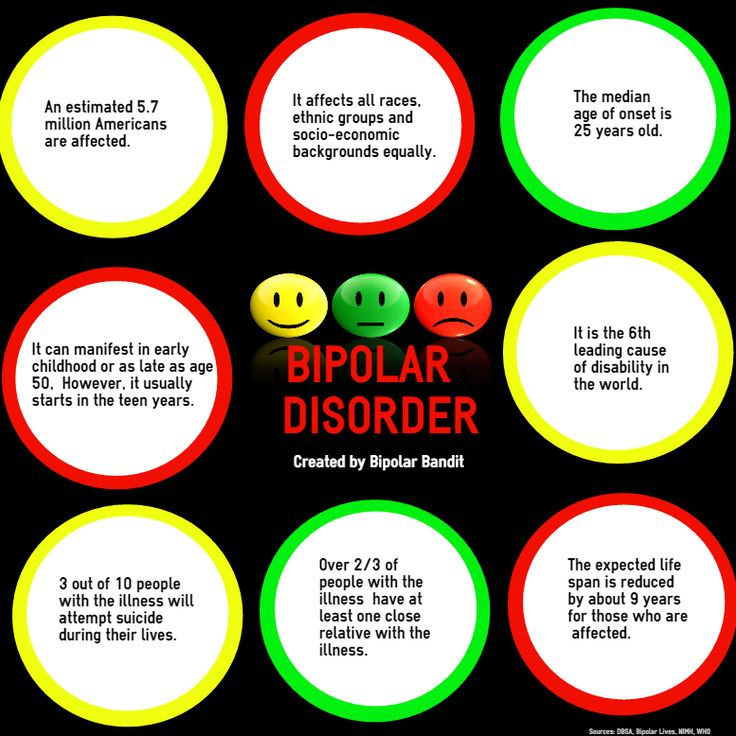

Diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder (BAD) in general and the depression that develops in this case - bipolar depression (BD) in particular is a complex problem. The differential diagnosis of bipolar disorder should be made with recurrent depression, schizophrenia, personality disorders, substance abuse, and affective disorders with somatic or neurological causes.

Based on a study by R. Hirschfeld et al. [59], 69% of patients before the diagnosis of bipolar disorder was observed with other diagnoses: unipolar depression (60%), anxiety disorder (26%), schizophrenia (18%), borderline or antisocial personality disorder (17%), alcohol abuse or other substances (16%) and schizoaffective disorder (11%). The greatest difficulty is the differential diagnosis of BAD type II and recurrent depressive disorder [74]. In 50% of cases, BAD manifests precisely with manifestations of depression. Despite the descriptions by P. Mitchel et al. [70], the clinical features of bipolar depression (high level of psychomotor retardation, heaviness in the body, lability of emotions, hyperphagia with weight gain, hypersomnia), the absence of verified episodes of elevated mood in the anamnesis leads to frequent diagnostic errors. In this case, hypomania, as a rule, does not fall into the field of view of the doctor and most often remains undiagnosed [9].5].

The greatest difficulty is the differential diagnosis of BAD type II and recurrent depressive disorder [74]. In 50% of cases, BAD manifests precisely with manifestations of depression. Despite the descriptions by P. Mitchel et al. [70], the clinical features of bipolar depression (high level of psychomotor retardation, heaviness in the body, lability of emotions, hyperphagia with weight gain, hypersomnia), the absence of verified episodes of elevated mood in the anamnesis leads to frequent diagnostic errors. In this case, hypomania, as a rule, does not fall into the field of view of the doctor and most often remains undiagnosed [9].5].

Several independent diagnostic studies have shown that up to 50% of young patients diagnosed with recurrent depression subsequently develop a bipolar course, i.e. they endure at least one episode of hypomania or mania [53]. The correct diagnosis of BAD, on average, is established only 10 years after the onset of the disease [8]. As a result, a significant proportion of patients with bipolar disorder are observed for a long time with an erroneous diagnosis, and they do not receive adequate therapy [25].

According to G. Sachs [86], such errors are associated primarily with the imperfection of the diagnostic system. When diagnosing an affective episode, the features of clinical symptoms are not taken into account, and such important factors as the age of manifestation, heredity and the course of the disease are not included in the criteria for affective disorders.

Meanwhile, timely diagnosis of bipolar disorder, detection of signs of this disease at the time of the development of depression in a patient, and administration of mood stabilizer therapy reduces the risk of complications and increases the chances of establishing a stable remission [8]. Features of the course of the disease, allowing to differentiate BD with recurrent (unipolar) depression, are given in tab. 1 .

There are other clinical signs that are more characteristic of BD compared to unipolar depression: a high level of psychomotor retardation, a feeling of heaviness in the body (“lead paralysis”), psychotic inclusions. The database often has features of confusion, i.e. in the structure of the symptom complex there are elements of manic symptoms. G. Parker et al. [75] showed that DSM-IV atypical features (high levels of anxiety, emotional lability, sensitivity to frustration situations, hyperphagia with weight gain, hypersomnia) are also associated with the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. One of the characteristic symptoms, especially in adolescents and the elderly, is irritability [70]. In addition, BD patients are characterized by a higher frequency and shorter duration of affective episodes [16].

The database often has features of confusion, i.e. in the structure of the symptom complex there are elements of manic symptoms. G. Parker et al. [75] showed that DSM-IV atypical features (high levels of anxiety, emotional lability, sensitivity to frustration situations, hyperphagia with weight gain, hypersomnia) are also associated with the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. One of the characteristic symptoms, especially in adolescents and the elderly, is irritability [70]. In addition, BD patients are characterized by a higher frequency and shorter duration of affective episodes [16].

It should be noted that there are significant shortcomings of the ICD-10 clinical classification adopted in Russia, which make it difficult to diagnose bipolar disorder in cases where manic symptoms are limited to episodes of hypomania. In accordance with the ICD-10, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder is established in the presence of at least one manic or mixed and depressive episode during the course of the disease. Unlike the American DSM-IV classification, in ICD-10 type II BAD is included only in the subsection "Other bipolar affective disorders" (F31.8) along with recurrent manic episodes. The DSM-IV defines the division into type I and type II bipolar disorder. BAD type II implies the presence of at least one full-blown depressive and at least one hypomanic episode (but not full-blown mania or a mixed state). Studies of the phenomenology, heredity, and course of this type of BAD define it as an independent disease with an extremely low probability of transformation into type I BAD [35].

Unlike the American DSM-IV classification, in ICD-10 type II BAD is included only in the subsection "Other bipolar affective disorders" (F31.8) along with recurrent manic episodes. The DSM-IV defines the division into type I and type II bipolar disorder. BAD type II implies the presence of at least one full-blown depressive and at least one hypomanic episode (but not full-blown mania or a mixed state). Studies of the phenomenology, heredity, and course of this type of BAD define it as an independent disease with an extremely low probability of transformation into type I BAD [35].

Modern large-scale studies consistently confirm the high prevalence of bipolar disorder, as well as the existence of a wide range of bipolar disorders. According to this concept, bipolar spectrum disorders account for up to 50% of all mood disorders [7, 15, 22, 30, 56], which contradicts existing ideas that at least 80% of these diseases belong to recurrent depression and dysthymia. .

Some authors consider resistance to antidepressants in depressed patients as a predictor of BAD [82, 111]. Recently, this opinion was confirmed by the results of a large cohort study [64]. At the same time, the results of a meta-analysis of 10 studies, including 863 patients with BD and 2226 with unipolar depression, did not reveal a significant difference in the therapeutic effect of antidepressants depending on the diagnosis [103].

Recently, this opinion was confirmed by the results of a large cohort study [64]. At the same time, the results of a meta-analysis of 10 studies, including 863 patients with BD and 2226 with unipolar depression, did not reveal a significant difference in the therapeutic effect of antidepressants depending on the diagnosis [103].

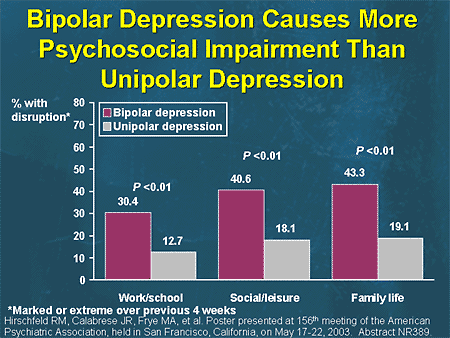

Pharmacotherapy BD

It is known that patients with bipolar disorder spend about half of their lives in a painful state, with depression occupying the largest share [60]. Depressive phases prevail in the picture of the disease in terms of frequency and duration. The damage from BD exceeds the damage from manias, since depression causes more disruption in the professional and social life of patients and increases the risk of suicide during and after an episode of depression [92, 107]. The frequency of parasuicides in mixed and depressive episodes reaches 25-50%, so the relief of depressive phases is one of the main goals of therapy for bipolar disorder.

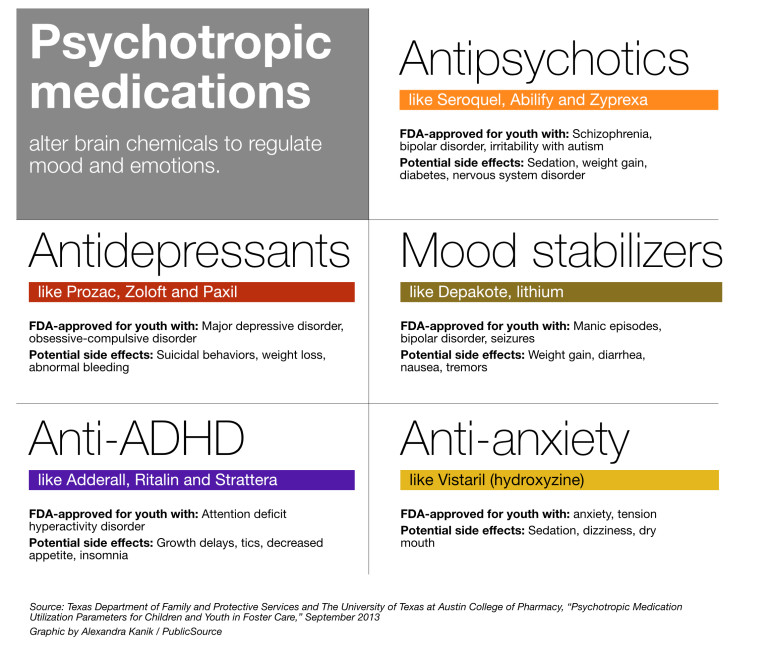

Depression is only one of the manifestations of BD, and the disease itself requires complex therapy, so the treatment strategy for BD should be based on its impact on the course of the underlying disease. For the treatment of BD, drugs of various pharmacological groups are used, the characteristics of which are presented below.

Antidepressants

In recent years, clinical guidelines for the treatment of BD have been published in various countries, but there is no complete consensus. In particular, there is no consensus among researchers regarding the use of antidepressants, since their use is associated with the risk of developing phase inversion, which is considered an unfavorable factor that aggravates the overall course of bipolar disorder and increases the risk of subsequent exacerbations [2, 38, 76]. Moreover, in approximately 25% of patients with bipolar disorder, uncontrolled use of antidepressants can lead to an increase in phase formation and the formation of a fast-cyclic and continual course [49, 97, 105].

In real psychiatric practice, antidepressants are often prescribed for BD, including as monotherapy [39], while the risk of phase inversion and the effect of such inversion on the prognosis of the further course of the disease are practically not taken into account [20].

Despite the widespread practical use of antidepressants in the treatment of AD, the number of studies of their efficacy and safety that meet the requirements of evidence-based medicine is very limited (Table 2) .

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have been used to treat bipolar disorder since their introduction into medical practice in the 1950s. In a retrospective analysis that included 1755 patients with recurrent and 277 with bipolar depression who received TCAs at the Psychiatric Clinic of the University of Munich in 1980-1992. [71], there were no significant differences between the groups in terms of the length of stay in the clinic and the dynamics of psychometric scales, which is an indirect confirmation of the effectiveness of TCA in BD. Another analysis of hospitalizations since 1920 to 1982, conducted in Switzerland [14], did not reveal an increase in the number of phase changes after the start of the use of TCAs. This conclusion, however, was refuted by controlled studies conducted in subsequent years to evaluate the effectiveness of TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine and four studies using imipramine) with BD (see Table 2) .

Another analysis of hospitalizations since 1920 to 1982, conducted in Switzerland [14], did not reveal an increase in the number of phase changes after the start of the use of TCAs. This conclusion, however, was refuted by controlled studies conducted in subsequent years to evaluate the effectiveness of TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine and four studies using imipramine) with BD (see Table 2) .

Meta-analysis of 12 randomized clinical trials by H. Gijsman et al. [47], included 1089 patients. It was based on both placebo-controlled and comparative studies with another antidepressant or drugs from other groups (normotimics, atypical antipsychotics). A meta-analysis showed that the risk of phase inversion with TCAs is significantly higher than with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or MAO inhibitors (10% vs 3.2%). In addition, TCAs were slightly less effective than other antidepressants in AD, but the differences were not statistically significant.

Similar results were obtained in a meta-analysis conducted by S. Montgomery [72], which showed that the frequency of affect inversions with SSRIs was 2-3% compared with 11% with TCAs. According to another analysis of antidepressant studies, TCAs provoke phase inversion in bipolar disorder in 11-38% of cases [79]. The results of several open studies indicate even higher rates of phase inversion - 31-74% with BD TCA monotherapy [48]. The frequency of inversions is dose-dependent and the higher the higher the doses used [50].

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of paroxetine adjunct to lithium therapy, no efficacy advantage of paroxetine over either lithium alone or lithium/imipramine combination was found, although the incidence of phase reversal in the paroxetine group was significantly lower than in the imipramine group [62].

Fluoxetine, compared with other SSRIs, caused a phase inversion somewhat more often, which may be due to its long half-life (T ½ of the active metabolite of norfluoxetine - 7-10 days), so it is undesirable to use it in patients with a history of mania induced by antidepressants [9].

In a prospective, double-blind study, when bupropion or desipramine was added to baseline mood stabilizer therapy, both drugs were equally effective. However, phase inversion was observed in 5 of 10 patients in the desipramine group and only in 1 of 9 patients treated with bupropion [83]. In a comparative study of bupropion, sertraline, and venlafaxine, used on the background of mood stabilizer therapy in 174 patients with type I and type II BD, in all groups there was an approximately equal number of responders (49-53%) and the number of patients who achieved remission (34-41%) [77]. At the same time, phase inversion was significantly more common in patients treated with venlafaxine.

In an open-label study of 83 patients with type II BD, venlafaxine monotherapy was superior to lithium monotherapy (responder rates 58.1% vs. 20.0%, patients in remission 44.2 vs. 7.5 %, respectively) [12]. In this study, there was no increase in phase inversion with venlafaxine.

Another study showed that the risk of phase inversion depends on the type of disease - in patients with BAD type II, inversion was significantly less common than in patients with BAD type I (12 and 2%, respectively) [10]. According to A.A. Aleksandrova [1], in the treatment of patients with BAD type I TCA, the frequency of phase inversion reaches 70%, and in patients with BAD type II - only 5-10%.

According to A.A. Aleksandrova [1], in the treatment of patients with BAD type I TCA, the frequency of phase inversion reaches 70%, and in patients with BAD type II - only 5-10%.

There are data on the development of tachyphylaxis to the effect of antidepressants during long-term therapy and during their repeated prescriptions to patients with bipolar disorder [13, 89]. According to L. Altshuler et al. [9], with BD monotherapy with antidepressants, a complete remission (total score when assessed on the Hamilton scale no more than 7) was observed only in 15-20% of patients. Moreover, relapse within 4 months was observed in 20-25% of patients, even with a good outcome, regardless of whether the antidepressant was continued or stopped [11].

There is evidence of insufficient efficacy of antidepressants in the treatment of BD [88]. In the STEP-BD study [87], the addition of paroxetine and bupropion to mood stabilizer therapy was not superior to placebo. In another double-blind, placebo-controlled comparative study, paroxetine was not superior to placebo in efficacy and was significantly inferior to the atypical antipsychotic quetiapine in reducing depressive symptoms on the MADRS scale [66]. In a recent meta-analysis by M. Sidor and G. Macqueen [90] showed no superiority of antidepressants compared to placebo. At the same time, there was also no significant increase in the risk of phase inversion under their influence.

Thus, the available results of studies on the effectiveness of antidepressants in AD are highly controversial. In part, this may be due to the well-known fact that in patients with BD on the background of the appointment of an antidepressant, an improvement in the condition can be observed, which neither clinicians nor researchers can confidently explain by the action of the drug, and not by the spontaneous end of the depressive phase. In addition, an analysis conducted in the United States by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) [101] showed the bias in the publication of clinical studies on the effectiveness of antidepressants: most of the studies with negative results were not published or were presented as studies with positive results (for example, phase inversion was regarded as an effective treatment). With an adequate assessment, only 51% (instead of 93%) of clinical studies on the effectiveness of antidepressants could be assessed as positive, and 49% as studies with a negative result. In general, antidepressants in BD are recommended to be used for the shortest possible time and, already at the first stage, to be combined with normothymic drugs that prevent phase inversion.

In a meta-analysis by S. Ghaemi et al. [46] with long-term use of antidepressants for the prevention of BD, the risk of phase inversion was 72% higher than with monotherapy with mood stabilizers, although the former showed greater effectiveness in preventing depressive phases. During the period of antidepressant withdrawal, in order to identify both depressive and manic symptoms, careful monitoring of the patient's condition is necessary [41, 42].

The question of the use of antidepressants in BD remains debatable. In most clinical guidelines, antidepressants retain their role in the treatment of OD, but they are recommended to be prescribed in combination with mood stabilizers [49, 108].

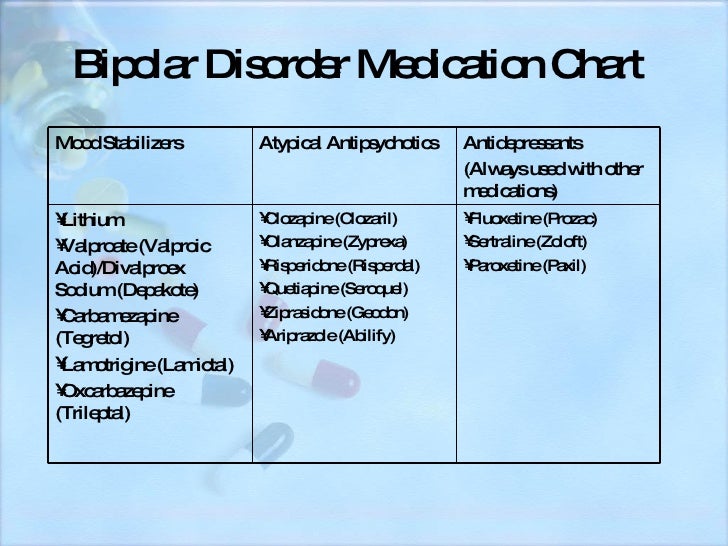

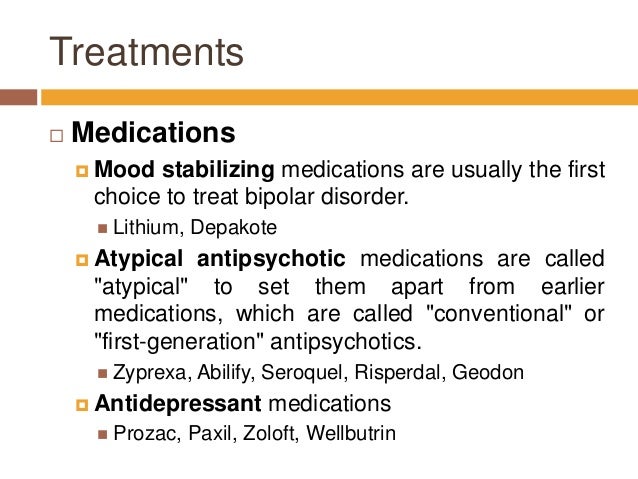

Normotimics

According to modern concepts, mood stabilizers are the drugs of first choice in the treatment of both mania and OD. This group includes 4 main drugs with a proven normothymic effect: lithium carbonate, sodium valproate, carbamazepine and lamotrigine. All drugs in this group have a more or less pronounced antidepressant effect. The main advantage of normotimics is a preventive effect, which allows prolonging the euthymic period. They also prevent the development of phase inversion caused by the additional prescription of antidepressants, often inevitable during periods of depressive states. Normotimics should be prescribed from the moment the disease is diagnosed, followed by continuous use throughout life [2].

Lithium salts have occupied leading positions among mood stabilizers for many years. The use of lithium in bipolar disorder was based on almost half a century of empirical experience and only later supported by the results of randomized clinical trials [104]. Some current guidelines for the treatment of BD recommend lithium as the first drug to start treatment of the bipolar phase of any polarity [17, 49, 108]. It is assumed that lithium has specific anti-suicidal properties [6, 33]. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study [48], lithium monotherapy was found to be effective in 79% of patients with BD and 36% with recurrent depression. In a review [106] of 9 different placebo-controlled studies of lithium in BD, including a total of 149 patients, the drug showed a clear antidepressant effect in 36% of cases, and positive dynamics was noted in another 79% of patients.

The dependence of the antidepressant activity of lithium on its blood concentration was shown in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled comparative study, which studied the effectiveness of adding imipramine and paroxetine to lithium in patients with BD [73]. Although the purpose of this study was not to study the effectiveness of lithium itself, patients in the control group received only lithium. When prescribing paroxetine or imipramine to patients with high serum lithium concentrations (0.8 mmol/l), the same therapeutic effect was observed as with lithium monotherapy, which allowed the authors to conclude that lithium monotherapy in BD is a fairly effective method. treatment, and the drug has its own thymoanaleptic effect. However, in a recent study of lithium versus quetiapine [110], lithium was not superior to placebo in reducing depressive symptoms.

The disadvantage of the antidepressant effect of lithium is its slow development. When prescribing lithium salts during the depressive phase, it takes an average of 6-8 weeks to achieve a clear clinical effect, so monotherapy in the acute period of the depressive phase is in most cases insufficient.

In recent years, a lot of data has been accumulated on the significant disadvantages of lithium salts in terms of safety and tolerability, especially when used in high doses. Common side effects of lithium preparations include weight gain, tremors, gastrointestinal disturbances, and drowsiness. The concentration of lithium in the blood plasma to achieve an antidepressant effect should be maintained at a level of 0.6-0.8 mmol/l, however, this increases the risk of side effects [45, 78]. Antidepressants, valproate or lamotrigine may be used to increase the effectiveness of lithium therapy [102, 109].

In connection with the above disadvantages of lithium, a number of modern guidelines favor valproate among mood stabilizers [55], which has moderate antidepressant properties [65], has a more favorable side effect profile compared to lithium salts, and is better tolerated by patients [104]. Some experts believe that valproate can be considered as a drug with anti-suicidal properties, since it can improve cognition and mood [61, 67]. The efficacy of valproate in BD has been studied in a number of studies. Thus, in an open study [106], the effectiveness of valproate in the treatment of depression in patients with BAD type II was 63% in general, and 82% in the subgroup of patients who had not previously received antidepressants. However, in a double-blind, randomized study [63] including patients with type I and type II bipolar disorder, by the end of week 8, there was no significant difference between the proportions of patients meeting the criteria for recovery in the valproate (43%) and placebo (27%) groups. . At the end of the study, valproate did not outperform placebo when assessed on the Hamilton scale, although at 2, 4 and 5 weeks this indicator was significantly better in the group receiving the active drug. It is believed that statistical differences between the effects of valproate and placebo were not obtained in this study due to undersampling [84].

In an 8-week, double-blind, randomized study [36], 25 outpatients reported positive results with valproate in patients with type I bipolar disorder. It was significantly superior to placebo in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety. In a meta-analysis by L. Smith et al. [94], valproate was also significantly superior to placebo in reducing depressive symptoms. There is evidence that valproate is more effective in treating depression in patients with rapid cycling or type II bipolar disorder compared to type I bipolar disorder [62].

The number of studies on the use of carbamazepine in BD is limited, and they cover a small number of patients. According to the results of a meta-analysis [76] of studies with different design, including patients with recurrent depression and BD, the response to carbamazepine therapy was observed in 56 and 44% of patients in open-label and controlled studies, respectively. Moderate efficacy of carbamazepine in BD was shown in one placebo-controlled study [21], but these results were not confirmed in other studies [93]. In total, 8 open-label and 4 small-scale controlled studies of the use of carbamazepine in BD were found in the literature, including 244 patients, of which 55% responded to therapy. At the same time, ⅓ of these, a pronounced effect or an effect that determines clinical recovery was observed [4]. Obviously, to confirm the antidepressant effect of carbamazepine in BD, additional placebo-controlled studies are needed. Current guidelines consider this drug as a second/third line therapy for OBD [54, 108].

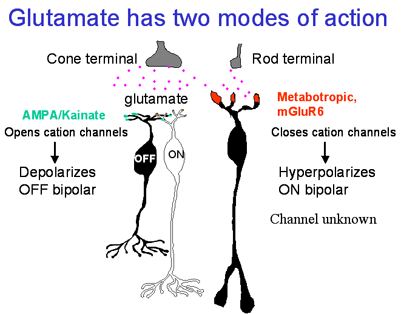

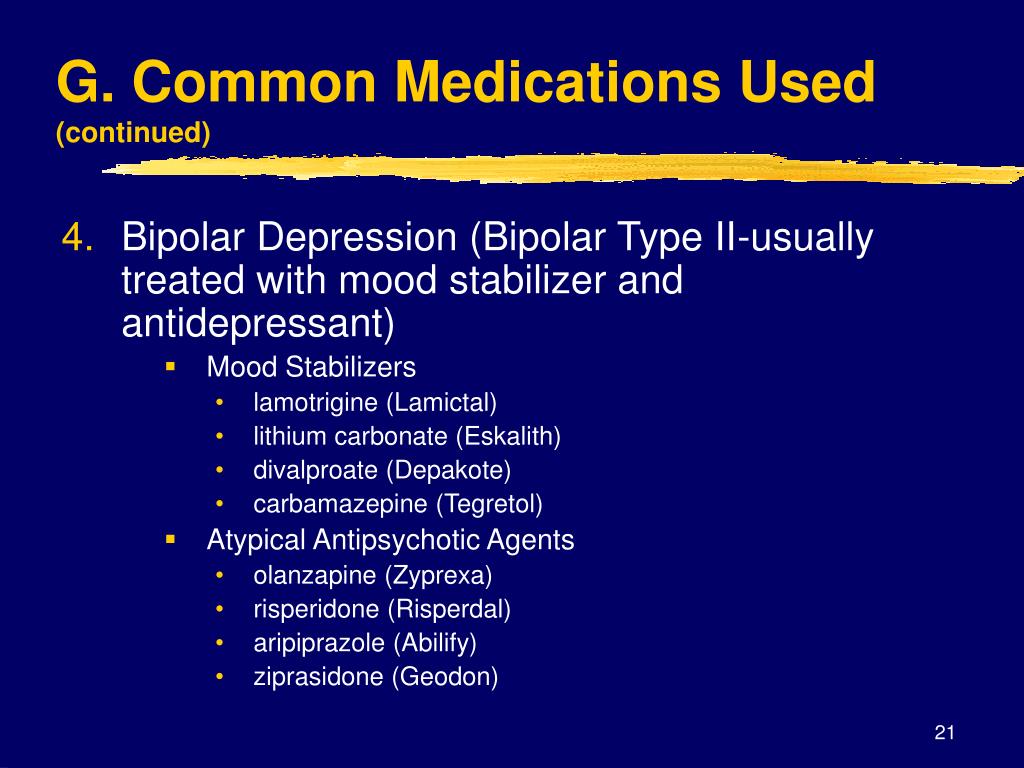

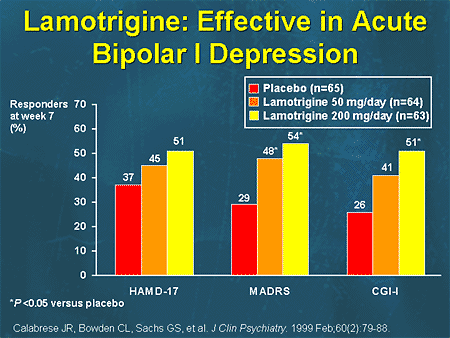

Lamotrigine occupies a special place among anticonvulsants in the treatment of BD. This drug showed significant antidepressant activity when used alone in a multicentre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study [27], which included 195 patients with moderate depression in type I bipolar disorder. Two groups of patients received fixed doses of lamotrigine 200 and 50 mg per day for 7 weeks, and patients in the third group received placebo. Patients in the lamotrigine groups experienced a significant reduction in depressive symptoms compared with the placebo group. The most significant antidepressant effect of lamotrigine was at a dose of 200 mg per day. A "significant improvement" score on the overall clinical impression scale was achieved in 51% and 41% of patients treated with lamotrigine 200 and 50 mg, respectively, compared with 26% in the placebo group.

Data on the efficacy of lamotrigine were confirmed by the results of a large multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that included 200 patients with BD in bipolar I and type II [24]. Lamotrigine at all doses (100–400 mg daily) was superior to placebo, with a greater response to lamotrigine in patients with type I BD. However, in other controlled trials [29], lamotrigine in BD did not show any benefit compared to placebo. However, one meta-analysis [44] showed superiority of lamotrigine over placebo, especially in patients with severe depression.

Lamotrigine is safe and well tolerated by patients. Its most common side effect is headache, and the frequency of affect reversal is comparable to that of placebo. With a rapid increase in doses of the drug, a rash developed in 0.3% of patients, with a slow titration of doses, its frequency decreased to 0.01%. In most guidelines, lamotrigine, like lithium and valproate, are considered first-line drugs for AD.

At the same time, analysis of data from large double-blind randomized controlled trials [96] showed that lamotrigine was inferior in efficacy to two FDA-approved drugs for the treatment of OBD (quetiapine and olanzapine plus fluoxetine), but superior to them in tolerability. This led the authors to suggest that lamotrigine is more likely to be indicated in patients with mild episodes of AD who are prone to sedation and weight gain.

Another anticonvulsant, topiramate, is also attracting attention for its potential efficacy in OBD. In a small randomized blind study in 36 outpatients with BD, when the anticonvulsant topiramate or the antidepressant bupropion was added to normothymic therapy with valproate or lithium, an equal efficacy of therapy with a significant reduction in depressive symptoms after 2 weeks of treatment was found [67]. Topiramate is safe and well tolerated; its most common side effect is weight loss (average 5.8 kg over 8 weeks). However, further studies are required to confirm its effectiveness in AD.

Another anticonvulsant, gabapentin, has been studied in only one double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study compared with lamotrigine [41]. At the same time, the effectiveness of therapy in the gabapentin group did not significantly differ from placebo and was lower than that of lamotrigine (26%, 19% and 45%, respectively).

Antipsychotics

In the last decade, the appearance of atypical antipsychotics in the arsenal of drugs has significantly expanded the possibilities of treating bipolar disorder, including its depressive phase. Considering that 50% of patients with bipolar disorder have psychotic symptoms at different stages of the disease, the appointment of antipsychotics becomes almost inevitable. Meanwhile, the use of classical antipsychotics in patients with bipolar disorder is limited by a number of factors. It has been shown that patients with bipolar disorder are more at risk of developing extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia compared with patients of other diagnostic groups [5, 51]. In addition, the depressogenic effect of classical antipsychotics is well known [3].

A meta-analysis that included 21 randomized and 13 non-randomized trials demonstrated a significant superiority of atypical antipsychotics over classical antipsychotics in BD [43].

Studies of olanzapine and quetiapine have demonstrated an antidepressant effect in addition to the reduction of psychotic symptoms and good tolerability. Thus, in a randomized 8-week study [100], which included 833 patients with moderate depression in type I bipolar disorder, both olanzapine monotherapy (10 mg per day) and its combination with fluoxetine were significantly superior to placebo in terms of antidepressant effect (response rate - 56, 1, 390 and 30.4%, remission rate - 48.8, 32.8 and 24.5%, respectively). Olanzapine was well tolerated by BD patients, with the most common side effects being drowsiness, increased appetite, weight gain, and dry mouth [100]. The combination of olanzapine with fluoxetine has been shown to be superior to lamotrigine in reducing depressive symptoms and the risk of self-injurious behavior. However, metabolic side effects were more frequently observed with its use [26].

The effectiveness of quetiapine in BD was also confirmed by the results of a meta-analysis of 7 randomized controlled trials [32]. In an 8-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study [28] of quetiapine (300 and 600 mg daily) in the treatment of 542 patients with depression in BAD types I and II, the drug at both doses was significantly superior to placebo in the ability to reduce the main symptoms of depression, including suicidality. thoughts. In another study, quetiapine was also significantly superior to placebo and lithium in reducing depressive symptoms on the Montgomery-Asberg scale [110]. These data were confirmed in subsequent studies. Thus, in the EMBOLDEN II study [66], quetiapine demonstrated superiority in reducing depressive symptoms over both placebo and active therapy with paroxetine. The antidepressant/quetiapine combination was also statistically significantly more effective than the antidepressant/lithium combination both in terms of the number of patients who responded to treatment (88 and 50%, respectively) and the number of patients who achieved remission (88 and 38%) [54]. Quetiapine and the combination of olanzapine with fluoxetine are officially registered for the relief of BD.

The antidepressant effect of risperidone has not been demonstrated in small, double-blind studies [69], although in an open study in patients with resistant recurrent depression, its addition to citalopram led to an increase in the effect of the antidepressant [81]. In double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, amisulpride has also been shown to have an antidepressant effect when used at low doses. However, these studies included patients with depressive states in diagnostic categories other than bipolar disorder [31]. The effectiveness of amisulpride as a treatment for BD requires further study.

Aripiprazole, according to the results of a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials, is effective in patients with both mania and depression, but its use may be limited by side effects - akathisia, insomnia, anxiety and nausea [18]. Another meta-analysis [40] showed that a significant difference from placebo in the treatment of patients with an acute episode of BD was noted only after 8 weeks of aripiprazole use, while the effect of the drug did not differ significantly from placebo. In addition, long-term outcomes of BD treatment with aripiprazole remain unexplored.

Therapeutic tactics for the relief of BD

Treatment for mild, moderate and severe depression without psychotic symptoms in type I and type II bipolar disorder is identical.

In patients not receiving normotimic, BD therapy should be started with a drug of this group. If the patient is already receiving a mood stabilizer, an attempt to increase its dose, the addition of quetiapine or the use of combination therapy with olanzapine and fluoxetine, or the addition of a second mood stabilizer and the addition of psychotherapy, is recommended. If these therapeutic measures are ineffective, it is possible to use combined therapy with a mood stabilizer and an antidepressant (mainly SSRIs), which is prescribed for the shortest possible time. When using combination therapy, it is necessary to take into account possible drug interactions of drugs.

If the second course of therapy is ineffective, it is possible to change the normotimic and / or antidepressant, or, in the case of protracted conditions, increasing social disadaptation, the issue of using electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) [80]. When ECT fails, anti-resistance measures are taken, similar to those used for resistant depression in recurrent depressive disorder.

In severe OD, as well as in the presence of suicidal thoughts, already at the first stage of treatment, combined therapy with a mood stabilizer and an antidepressant is recommended [99] or the use of quetiapine, or a combination of olanzapine with fluoxetine. If the first course is ineffective, an attempt to change the antidepressant is first recommended, then a mood stabilizer, or the use of ECT.

Thus, at present, there is no drug that, in monotherapy, could provide all the effects necessary for BD, namely, the rapid relief of depressive and psychotic symptoms, the prevention of suicide and the prevention of phases of both poles. Some drugs appear to be very promising, but the number of well-designed studies in this area remains very limited. There has not been a single consensus among experts regarding the stages of BD therapy. Approaches to diagnosing BD also require improvement. The solution of these problems will significantly alleviate the symptoms of the disease, reduce the frequency of its exacerbations and significantly improve the quality of life of patients with BD.

Antidepressant therapy with antidepressants. Lamictal and the problem of drug resistance | Yastrebov D.V.

Introduction The initial prescription of antidepressants, the effectiveness of which has been proven in clinical studies, involves achieving a drug response rate of 50-75% within 3-4 weeks of therapy. From this it follows that from 25 to 50% of patients fall into a group of heterogeneous conditions, defined as "treatment-resistant depression" [I.M. Anderson et al., 2000; Schatzberg A.F., 2003]. Today there is no generally accepted definition of the phenomenon of drug resistance. For the most part, the use of this term implies the absence of a satisfactory response to treatment. However, the criteria used in clinical trials, which involve a rating system-based assessment of symptom dynamics as a result of therapy (eg, a 50% reduction in the total score of the HAMD1 scale), are of little use in everyday practice. As one of the reasons for this, one can mention that an improvement of this level is often not recognized by the patient as a positive outcome, which is confirmed by the discrepancy between subjective and objective ratings that is often found in clinical studies [A.J. Rush et al., 2006].

The initial prescription of antidepressants, the effectiveness of which has been proven in clinical studies, involves achieving a drug response rate of 50-75% within 3-4 weeks of therapy. From this it follows that from 25 to 50% of patients fall into a group of heterogeneous conditions, defined as "treatment-resistant depression" [I.M. Anderson et al., 2000; Schatzberg A.F., 2003]. Today there is no generally accepted definition of the phenomenon of drug resistance. For the most part, the use of this term implies the absence of a satisfactory response to treatment. However, the criteria used in clinical trials, which involve a rating system-based assessment of symptom dynamics as a result of therapy (eg, a 50% reduction in the total score of the HAMD1 scale), are of little use in everyday practice. As one of the reasons for this, one can mention that an improvement of this level is often not recognized by the patient as a positive outcome, which is confirmed by the discrepancy between subjective and objective ratings that is often found in clinical studies [A.J. Rush et al., 2006].

Other definitions based on the clinical assessment of the condition suggest an estimate of the number of unsuccessful treatments (2 or more). And finally, the third version of the definitions involves the persistence of depressive symptoms in the absence of success in achieving a state of remission as a result of the therapy (it should be noted that in this case the concepts of remission and drug response are combined) - M.R. Nelsen, D.L. Dunner, 1993; M.E. Thase, P.T. Ninan, 2002.

Any of the listed approaches for determining drug resistance is justified only for patients for whom there were no diagnostic inconsistencies and for whom adequate therapy was initially prescribed. In these cases, one speaks of the so-called "true" resistance. However, there are other options in which the achieved drug response against the doctor's expectations can be assessed as insufficient. Among them can be named: an error in the choice of an antidepressant or its dosage; poor tolerance, which makes it impossible to use a specific drug in the appropriate dose, violations of compliance, and a number of others (Fig. 1). It is obvious that in these cases, sometimes defined as "pseudo-resistance" or "relative resistance", medical tactics are fundamentally different and should be aimed at overcoming or eliminating factors that interfere with the achievement of a drug response [H.E. Lehmann, 1974].

After eliminating the signs that allow attributing the lack of a drug response to the account of "pseudo-resistance", the question arises of determining the "true" (absolute) resistance [D. Bird et al., 2002]. In contrast to the previously existing ideas about drug resistance, as a phenomenon of the atomic order, M. Thase and A. Rush (1997) proposed a dynamic multi-stage system for assessing therapy-resistant depression, which is currently widely used. This typology reflects the authors' idea of drug resistance as a stage concept that requires comparison of the entire set of previous therapeutic measures that did not lead to an improvement in the condition (Table 1).

More complex is the taxonomically organized European staged method for assessing drug resistance, partially echoing the approach of M. Thase and A. Rush. Each of the stages of resistance, instead of a serial number, has its own definition with the designation of groups of drugs and the terms of their therapy that did not lead to an improvement in the condition (Table 2).

Depression variants,

therapy resistant

The issue of determining the clinical subtype of depression (psychotic, atypical, seasonal) is an important component in the management of this group of patients, since such differences may determine sensitivity to a particular therapy option. In addition, resistance to therapy may be due to an erroneous diagnosis with the definition of a unipolar variant of a depressive disorder in a patient with an undiagnosed bipolar course. Due to the fact that depressive phases in patients with bipolar disorder are clinically detected more often (including due to the greater attendance of patients with depressive symptoms), it is expected that up to half of patients with bipolar disorder can receive treatment according to therapeutic algorithms developed for unipolar depression. [S.N. Ghaemi et al., 1999]. As will be shown below, the question of the correct diagnosis of bipolar disorder is key in the appointment of therapy.

Coping methods

drug resistance

Identification of a case of drug resistance dictates to the doctor the need to change the tactics of managing the patient. At the first stage, the choice is made between two main options: changing the antidepressant or prescribing an additional drug to "enhance" the antidepressant effect of the main drug. Let's take a closer look at each of them.

Changing Therapy

Changing the drug is preferable in the event of a complete lack of response to therapy or in the presence of side effects requiring the withdrawal of the originally prescribed antidepressant. Despite the apparent obviousness of the fact that the change of an antidepressant that turned out to be ineffective should imply the choice of a “second-line” drug with a fundamentally different mechanism of action, there are separate data arguing the expediency of switching to a more potent drug of the same group. In particular, for the most commonly prescribed antidepressants - selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), it has been shown that the change of less potent drugs (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram) that did not improve the symptoms of depression to more potent ones (paroxetine, sertraline) gives a percentage of improvements similar to selective ones. serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine) and selective norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (bupropion) up to 30% of cases. At the same time, the number of cases of early discontinuation of therapy due to developed side effects for "double-acting" drugs is 25% higher than for drugs of the SSRI group.

Thus, the assumption that the lack of sensitivity of depressive symptoms to the initially prescribed antidepressant indicates the ineffectiveness of the entire class of drugs with a similar mechanism of action has not been confirmed to date [A.J. Rush et al., 2006]. These data, presented in the form of practical recommendations, show that when changing therapy, it is justified to choose a drug not with the largest number of cumulative mechanisms of action, but with the maximum potential in relation to the leading neurotransmitter system (for SSRIs, this is paroxetine (Paxil) and sertraline). At the same time, certain arguments can be given that do not allow defining this tactic as the main one. In particular, an increase in drug potential automatically means a decrease in tolerability. Thus, in patients who notice the occurrence of certain side effects even during first-line therapy, tactics aimed at enhancing the potential of the drug can lead to worse tolerability and a decrease in the level of drug compliance [Thase M.

E., Rush A.J., 1997].

Antidepressant withdrawal policy

Discontinuation of drug antidepressant therapy (AD-therapy) may be accompanied by the occurrence of certain disorders, which are currently accepted to be classified as part of the "anti-adhesion discontinuation syndrome" (AD-AD cessation syndrome).

In earlier studies, the terms “AD withdrawal reaction” and “AD withdrawal syndrome” were more often used to denote pathological symptoms associated with antidepressant (AD) withdrawal [Rotschild, 1995; Dilsaver, 1984; Garner, 1993], which were later changed to emphasize the difference between these disorders and classical withdrawal, which already “reserved” these concepts for itself. However, until now, uncertainty remains in the terminological attribution of the same clinical manifestations, reflecting the opinion of a particular author about the advisability of considering them as withdrawal symptoms [Haddad, 2005].

Early descriptions of SPP AD appeared already in the course of clinical trials of the first ADs (imipramine) [Mann, 1959]. Subsequently, reports of similar disorders were given for almost all groups of AD: other tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), MAO inhibitors (MAOIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and other modern antidepressants [ Hadad, 2004]. It was revealed that the features and severity of SPP BP vary both in relation to different groups of drugs, and for representatives within the same class.

Despite the fact that usually SPP AD manifests itself within a few days after stopping the use of AD or reducing the dosage of the drug and is characterized by a short duration and relative mildness of manifestations, correct recognition if they occur is important, because. these conditions are associated with certain disturbances in daily activities, causing a marked decrease in performance, and their occurrence in a patient unaware of this possibility can lead to serious violations of drug compliance. Also, in some cases, SPP BP can take on a rather pronounced character, requiring hospitalization of the patient [Warner, 2006].

As the main measure to prevent the occurrence of SPP AD or minimize its manifestations, most authors declare the need to follow the prescribed regimen of taking the drug with the elimination of possible interruptions. If it is necessary to cancel blood pressure, it is advisable to follow the method of gradual dose reduction, taking into account the pharmacokinetic properties of a particular drug. The therapeutic value of the last recommendation, in our opinion, however, needs additional verification. According to the data of comparative studies, the gradual abolition of blood pressure allows to achieve an approximately two-fold decrease in the severity of SPP AD compared with one-stage [Van Geffen, 2005]. However, there are other data that show that the gradual withdrawal of the drug rather "blurs" the "rebound" symptoms throughout the entire period of withdrawal. If the manifestations of SPP BP are mild, this technique really makes it possible to additionally “smooth out” them, however, with a greater severity of violations, such tactics of “delaying” may be inappropriate [Yastrebov, 2007]. In addition, the result of gradual withdrawal does not guarantee an asymptomatic outcome of AD withdrawal.

According to various sources, up to 50% of patients diagnosed with SPP AD discontinued the drug gradually [Barr, 1994; Pacheco, 169]. Among the factors associated with an increased risk of developing SPP AD, we can name episodes of reactions to the abolition of AD that have already been noted in the anamnesis. In this case, the risk of developing SPP BP increases to 75% [Black, 2000]. For such patients, when canceling AD, gradual withdrawal over 4–8 weeks is desirable, possibly under the “cover” of a short course of replacement therapy, which can be tranquilizers or AD with a different mechanism of action than the drug being withdrawn. These drugs, on the one hand, stop SPP BP, and on the other hand, allow the corresponding receptor subsystems (but not the concentration of the corresponding neurotransmitter) to return to the “pre-therapeutic” state (for example, when paroxetine is canceled - mirtazapine), which in most cases allows you to “cover up” the manifestations reactive symptomatology throughout its course up to complete regression [Warner, 2006].

Combination therapy

In the event that a certain positive shift in the clinical picture of depression is recorded, which, however, indicates only a partial response to therapy, and at the same time the tolerability of the initially prescribed antidepressant is assessed as satisfactory, it is proposed to use combination therapy with the addition of either another antidepressant ("dual therapy"). ”), or a drug of another class that enhances the effect of the main antidepressant (enhanced therapy). There are some differences between these two combination therapy options.

"Dual" therapy involves the addition of a second antidepressant to an existing monotherapy. At the same time, unlike the procedure for changing an antidepressant, its mechanism of action, if possible, should not overlap with that of the “primary” drug. An example is the combination of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram) or a selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor with a drug such as mirtazapine. However, this tactic has not been widely adopted for a variety of reasons. The main one is that this approach, despite the simplicity of its definition, is largely based on empirical experience and is difficult to rationally evaluate the effectiveness and formalize the assignment algorithm. To date, there are no comparable data on the effectiveness of various combinations of antidepressants; at the same time, the number of side effects, due to which patients stop treatment, increases significantly. Separately, it is necessary to specify the special care required in these cases in the choice of drugs to exclude undesirable drug interactions.

An enhanced version of combination therapy involves the appointment of an antidepressant, coupled with one of the antipsychotics, or with drugs from the group of mood stabilizers. The latter include lithium salts, carbamazepine, salts of valproic acid and lamotrigine (Table 3).

Restrictions on the use of antidepressants

The choice of drugs for antidepressant therapy requires mandatory consideration of the characteristics of the clinical picture of an affective disease and its dynamics in general. So, R. El–Mallakh and A. Karippot (2006) indicate that the presence of a history of signs of a bipolar course makes the appointment of antidepressants alone undesirable due to the possibility of affect inversion, cycle acceleration and the appearance of prolonged irritable dysphoria.

Thus, it is suggested that antidepressant monotherapy is undesirable in patients with depression as part of bipolar disorder due to the possible worsening of the course of bipolar disorder [C.B. Nemeroff, 2001]. Official guidelines published by the American Psychiatric Association [APA Practice Guidelines, 2002] also recommend that antidepressants should not be used as monotherapy in these patients at all initially. Instead, a one-time appointment of at least combination therapy is proposed; it is recommended to use lithium salts or Lamictal (lamotrigine) along with antidepressants as first-line agents at the stage of active therapy. These recommendations are based on recent studies of depression in bipolar disorder defined as resistant to prior therapy (stage II resistance). It has been shown that the appointment of such patients with mood stabilizers (Lamictal (lamotrigine) at doses up to 150-250 mg per day) for combination with antidepressants can significantly increase the level of drug response in comparison with atypical antipsychotics (risperidone) and reduce the likelihood of relapse within a year (with 5% for risperidone to 24% for Lamictal (lamotrigine)) [A. A. Nierenberg et al., 2006].

Separate attention should be paid to the possibility of using drugs that do not belong to the class of antidepressants for monotherapy of depression in bipolar disorder. Existing data confirm the possibility of using some mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics in this capacity (Table 4) [K. Fountoulakis et al., 2007].

It must be noted that the appointment of some of the above drugs for long-term therapy (atypical antipsychotics, especially olanzapine), despite proven effectiveness, may be undesirable due to their inherent undesirable side effects, mainly manifested with long-term use (weight gain, metabolic disorders) .

Long-term prophylactic monotherapy with lamotrigine for bipolar depression

Experience with long-term use of Lamictal has shown that this drug is equally effective in bipolar I and II disorders [Geddes, 2009]. The advantages of Lamictal, which justify its use at the stage of long-term preventive therapy, are: the effect on the residual manifestations of depression, the absence of rebound symptoms upon withdrawal, and the minimal presence of side effects [Calabrese, 2008]. Of particular value to the drug is the absence of the ability to cause weight gain with long-term use, which may justify the need to transfer patients with a tendency to obesity from other drugs (including lithium) to it [Bowden, 2006].

Appendix

Article published

with financial support from GlaxoSmithKline

1 HAMD: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

Literature

1. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision).

2. Anderson I. M., Nutt D. J., Deakin J. F. W. Evidence–based guidelines for treating depressive illness with antidepressants: a revision of the 1993 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol (2000), 14, 3–20.

3. Barr L. C., Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H. Physical symptoms associated with paroxetine discontinuation. Am J Psychiatry (1994), 151, 289.

3. Bird D., Haddad P. M., Dursun S. M. An overview of the definition and management of treatment–resistant depression. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni 2002; 12:92–101.

4. Black K., Shea, C., Dursun, S., Kutcher, S. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J Psychiatry NeuroSci (2000), 25, 255–261.

5. Calabrese JR, Huffman RF, White RL, Edwards S, Thompson TR, Ascher JA, et al. Lamotrigine in the treatment of bipolar depression: results of five double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials.

6. Charles L. Bowden, M.D. Joseph R. Calabrese, M.D. Terence A. Ketter, M.D. Gary S. Sachs, M.D. Robin L. White, M.S. Thomas R. Thompson, M.D. Impact of Lamotrigine and Lithium on Weight in Obese and Nonobese Patients With Bipolar I Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1199–1201.

7. Dilsaver S. C., Greden, F. J. Antidepressant withdrawal phenomena. Biol Psychiatry (1984), 19, 237–256.

8. Ghaemi S. N., Sachs G. S., Chiou A. M., Pandurangi A. K., Goodwin K. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord 1999;52:135–44.

9. El–Mallakh R. S., Karippot A. Chronic depression in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Aug;163(8):1337–1341; quiz 1478.

10. Fountoulakis K. N., Vieta E., Siamouli M. et al. Treatment of bipolar disorder: a complex treatment for a multi-facet disorder. Annals of General Psychiatry 2007, 6:27 (http://www.annals-general-psychiatry.com/content/6/1/27).

11.

12. Haddad P.M. Do antidepressants cause dependence? Epidemiologie e Psychiatria Sociale (2005), 14, 58–62.

13. Haddad P. M., Anderson, I., Rosenbaum, J. (2004). Antidepressant discontinuation syndromes. In Haddad P., Dursun, P., Deakin, B. (Ed.), Adverse syndromes and psychiatric drugs: a clinical guide. (pp. 183–205). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

14. John R. Geddes, Joseph R. Calabrese and Guy M. Goodwin. Lamotrigine for treatment of bipolar depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry (2009) 194, 4–9.

15. Lehmann H. E. Therapy–resistant depressions–a clinical classification. Pharmakopsychiatr Neuropsychopharmakol 1974;7:156–63.

16. Mann A. M., MacPherson, A. Clinical experience with imipramine (G22355) in the treatment of depression. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal (1959), 4, 38–47.

17. Messenheimer J., Mullens E.

18. Nelsen M. R., Dunner D. L. Clinical and differential diagnostic aspects of treatment-resistant depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research. Vol. 29, 1, January–February 1995, 43–50.

19. Nemeroff C. B., Evans D. L., Gyulai L., Sachs G. S., Bowden C. L., Gergel I. P., Oakes R., Pitts C. D.: Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of imipramine and paroxetine in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:906–912

20. Nierenberg A. A., Ostacher M. J., Calabrese J. R., Ketter T. A., Marangell L. B., Miklowitz D. J., Miyahara S., Bauer M. S., Thase M. E., Wisniewski S. R., Sachs G. S. Treatment–resistant bipolar depression: a STEP–BD equipoise randomized effectiveness trial of antidepressant augmentation with lamotrigine, inositol, or risperidone. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Feb;163(2):210–6.

21. Pacheco L., Malo, P., Aragues, E., Etxebeste, M.

22. Rotschild A. J. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor–induced sexual dysfunction: efficacy of a drug holiday. Am J Psychiatry (1995), 152, 1514–1516.

23. Rush A. J., Kraemer H. C., Sackeim H. A., et al. Report by the ACNP Task Force on response and remission in major depressive disorder. neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1841–1853.

24. Rush A. J., Trivedi M. H., Wisniewski S. R., Stewart J. W., Nierenberg A. A., Thase M. E., Ritz L., Biggs M. M., Warden D., Luther J. F., Shores–Wilson K., Niederehe G., Fava M. Bupropion–SR , sertraline, or venlafaxine–XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006 Mar 23;354(12):1231–1242.

25. Santos M. A., Rocha F. L., Hara C. Efficacy and Safety of Antidepressant Augmentation With Lamotrigine in Patients With Treatment–Resistant Depression: A Randomized, Placebo–Controlled, Double–Blind Study. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry.

26. Schatzberg A. F., Cole J. O., DeBattista C. Manual of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2003:42.

27. Souery D., Amsterdam J., de Montigny C., Lecrubier Y., Montgomery S., Lipp O., Racagni G., Zohar J., Mendlewicz J. Treatment resistant depression: methodological overview and operational criteria. European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology 1999;9(1–2):83–91.

28. Thase M. E., Rush A. J. When at first you don’t succeed: sequential strategies for antidepressant nonresponders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:23–29.

29. Thase M. E., Ninan P. T. New goals in the treatment of depression: moving towards recovery. Psychopharma Bull. 2002;36(Suppl 2):24–35.

30. Van Geffen E.C., Hugtenburg, J.G., Heerdink, E.R., Van Hulten R.P., Egberts, A.C.G. Discontinuation symptoms in users of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in clinical practice: tapering versus abrupt discontinuation.

The relevance of a particular drug interaction to a specific individual is difficult to determine. Always consult your healthcare provider before starting or stopping any medication.

The relevance of a particular drug interaction to a specific individual is difficult to determine. Always consult your healthcare provider before starting or stopping any medication.