Grieving the death of a mother

10 Tips for Handling the Grief

The finality of death can feel almost unbelievable, particularly when it strikes a parent, someone whose presence in your life may have never wavered.

You finished growing up and successfully reached adulthood, but you still needed (and expected to have) your parents for years to come.

The loss of their support, guidance, and love can leave a vast emptiness and pain that might seem impossible to heal, even if their death was expected.

Or, maybe you and your parent were estranged or had a complicated relationship, resulting in a roller coaster of conflicting emotions.

Yet the world at large may expect you to recover from your grief fairly quickly — after the prescribed 3 days of bereavement leave, perhaps padded with a few extra days of personal time — and get back to business.

There’s no right or wrong way to grieve the loss of a parent, but these strategies can offer a starting place as you begin to acknowledge your loss.

Sadness is common after the loss of a parent, but it’s also normal for other feelings to take over. You may not feel sad, and that’s OK, too. Perhaps you only feel numb, or relieved they’re no longer in pain.

Grief opens the gate to a flood of complicated, often conflicting emotions. Your relationship with your parent might have had plenty of challenges, but it still represented an important key to your identity.

They created you, or adopted and chose to raise you, and became your first anchor in the world.

After such a significant loss, it’s only natural to struggle or experience difficulties coming to terms with your distress.

You might experience:

- anger or frustration

- guilt, perhaps for not contacting them frequently or not being present for their death

- shock and emotional numbness

- confusion, disbelief, or a sense of unreality

- hopelessness or despair

- physical pain

- mental health symptoms, including depression or thoughts of suicide

- relief that they’re no longer in pain

No matter how the loss hits you, remember this: Your feelings are valid, even if they don’t line up with what others think you “should” feel.

People react to grief in different ways, but it’s important to let yourself feel all of your feelings.

There’s no single right way to grieve, no set amount of time after which you can automatically expect to feel better, no stages or steps to check off a list. This in itself can be difficult to accept.

Denying your feelings may seem like a route toward faster healing. You might also get the message that others expect you to bury your grief and move on before you’ve come to terms with your loss.

Remind yourself grief is a difficult process as well as a painful one. Try to not let the opinions of others sway you.

Some people work through grief in a short time and move forward with the remnants of their sadness safely tucked away. Others need more time and support, no matter how expected the death was.

If your parent passed after a long illness, you may have had more time to prepare, but no amount of preparation makes your grief any less significant when it hits. You might still feel stunned and disbelieving, especially if you held out hope for their recovery to the very end.

You might still feel stunned and disbelieving, especially if you held out hope for their recovery to the very end.

The unexpected death of a parent still in middle age, on the other hand, may force you to confront your own mortality, a battle that can also complicate grief.

As you navigate the days, weeks and months following the loss of a parent, you may experience a variety of emotions and feelings. These may also change over time.

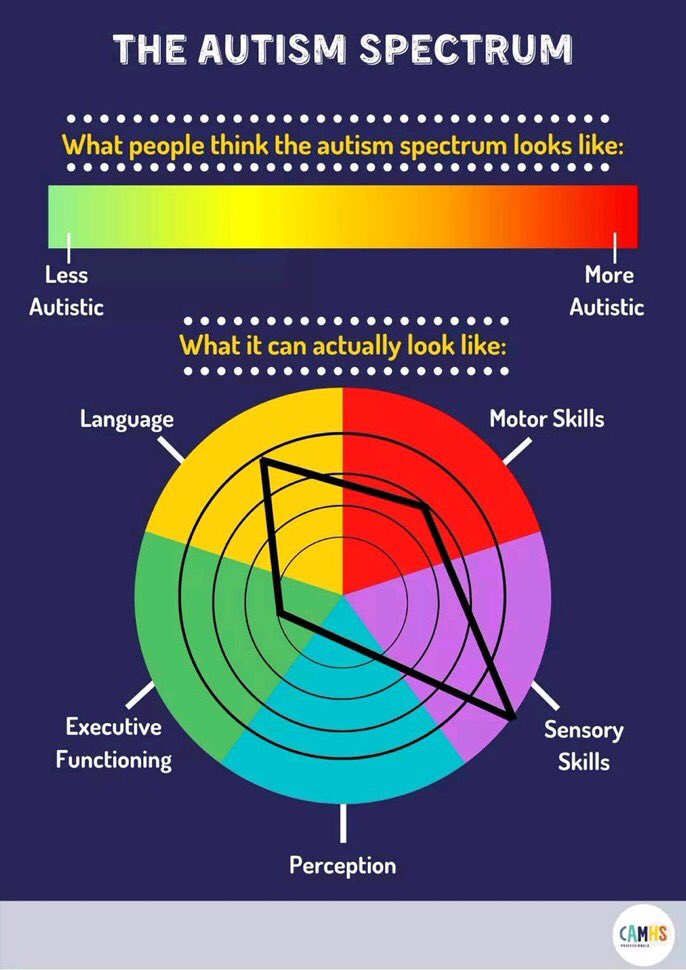

Some people may go through what is referred to as the five stages of grief. These include:

- Stage one: denial. This can feel like being in a state of shock or confusion surrounding the death of a parent. A person in this stage may feel the need to keep busy all the time, or do what they can to avoid dealing with the issue.

- Stage two: anger. A person in this stage may feel frustration, rage or even resentment. They may display behaviors that are irritable, sarcastic or pessimistic. They may also get into arguments or turn to alcohol or drugs.

- Stage three: bargaining. A person in the bargaining phase of grief may have feelings of shame, guilt, blame or insecurity. They may ruminate on matters of the past or worry about the future. They may judge themselves or others, overthink and worry.

- Stage four: depression. During this stage, people may feel hopeless, sad, disappointed and overwhelmed. They may experience changes to their sleep or appetite, have a lack of interest in social activities and have reduced energy.

- Stage five: acceptance. People in the final stage of grief may feel a sense of self-compassion, courage, pride and even wisdom. They may accept reality for what it is, be present in the moment as it happens and be able to adapt and cope with the situation.

Grief often has a significant impact on daily life:

- Your state of mind might change rapidly, without warning.

- You might notice sleep problems, more or less of an appetite, irritability, poor concentration, or increased alcohol or substance use.

- You might find it tough to work, take care of household tasks, or see to your own basic needs.

- The need to wrap up your parent’s affairs may leave you overwhelmed, particularly if you have to handle this task alone.

Some people find comfort in the distraction of work, but try to avoid forcing yourself to return before you feel ready, if possible. People often throw themselves into work, taking on more than they can comfortably handle to avoid scaling the ever-present wall of painful emotions.

Finding a balance is key. Some distraction can be healthy, provided you still make time to address your feelings.

It might seem difficult, even inconsiderate, to dedicate time to self-care, but prioritizing your health becomes even more important as you recover from your loss.

Keep these tips in mind:

- Get enough sleep. Set aside 7 to 9 hours each night for sleep.

- Avoid skipping meals.

If you don’t feel hungry, choose nutritious snacks and small meals of mood-boosting foods.

If you don’t feel hungry, choose nutritious snacks and small meals of mood-boosting foods. - Hydrate. Drink plenty of water.

- Keep moving. Stay active to energize yourself and help raise your spirits. Even a daily walk can help.

- Aim for moderation. If you drink alcohol, try to stay within recommended guidelines. It’s understandable to want to numb your pain, but increased alcohol use can have health consequences.

- Reset. Rest and recharge with fulfilling hobbies, such as gardening, reading, art, or music.

- Be mindful. Meditating or keeping a grief journal can help you process emotions.

- Speak up. Talk to your healthcare provider about any new physical or mental health symptoms. Reach out to friends and other loved ones for support.

Talking to family members and other loved ones about what your parent meant to you and sharing stories can help keep their memory alive.

If you have children, you might tell stories about their grandparent or carry on family traditions that were important in your childhood.

It might feel painful at first to reminisce, but you may find that your grief begins to ease as the stories start flowing.

If you feel unable to openly talk about your parent for the moment, it can also help to collect photographs of special times or write them a letter expressing your grief about their passing.

Not everyone has positive memories of their parents, of course. And people often avoid sharing negative memories about people who’ve passed. If they abused, neglected, or hurt you in any way, you may wonder whether there’s any point to dredging up that old pain.

If you’ve never discussed or processed what happened, however, you might find it even harder to heal and move forward after their death. Opening up to a therapist or someone else you trust can help lighten the load.

Many people find that specific actions can help honor a deceased parent and offer a measure of comfort.

You might consider:

- creating a small home memorial with photos and mementos

- planting their favorite tree or flower in your backyard

- adopting their pet or plants

- continuing work they found meaningful, like volunteering or other community service

- donating to their preferred charity or organization

Upon hearing the news that an estranged parent has passed away, you might feel lost, numb, angry, or surprised by your grief. You might even feel cheated of the opportunity to address past trauma or unresolved hurt.

Life doesn’t always give us the answers we seek or the solutions we crave. Sometimes you just have to accept inadequate conclusions, however unfinished or painful they feel.

Knowing you can no longer address the past might leave you feeling as if you’re doomed to carry that hurt forever.

Instead of clutching tight to any lingering bitterness, try viewing this as an opportunity to let go of the past and move forward — for your sake.

Some things are truly difficult to forgive, but harboring resentment only harms you, since there’s no one left to receive it.

A letter can help you express things previously left unsaid and take the first steps toward processing the painful and complex feelings left after their death. Working with a therapist can also help you begin to heal the pain of the past.

Friends and loved ones may not know exactly what to say if they haven’t faced the same type of loss, but their presence can still help you feel less alone.

It’s normal to need time to mourn privately, but at the same time, completely isolating yourself generally doesn’t help. The companionship and support of those closest to you can help keep you from being overwhelmed by your loss.

Beyond providing a supportive presence, friends can also help out with meals, child care, or handling errands.

Just be sure to let others know what you need.

If you want to talk about your parent, you might ask if they’re able to listen. If you’d like a break from thinking about their death, you might ask them to join you in a distracting activity, whether that’s playing a game, watching a movie, or working on a project around the house.

If you’d like a break from thinking about their death, you might ask them to join you in a distracting activity, whether that’s playing a game, watching a movie, or working on a project around the house.

You might notice family relationships begin to change after your parent’s death.

Your remaining parent, if still living, may now look to you and your siblings for support. Your siblings, if you have any, are facing the same loss. Their unique relationship with your parent can mean they experience the loss differently than you do, too.

It’s not unusual for siblings to experience conflict or slowly drift apart, particularly if you disagreed over your parent’s end-of-life care.

Yet family bonds can provide comfort during grief. You’ve experienced the same loss, even though that person meant something different to each of you.

If you cherish your family relationships, make an effort to strengthen those bonds and draw closer together.

This might mean reaching out more often than in the past or inviting them more regularly to visit and participate in family gatherings.

It can also mean listening with empathy when a sibling who had a difficult relationship with your parent now finds it hard to come to terms with their conflicting emotions.

Friends and loved ones may offer comfort, but a grief support group can fulfill a different kind of social need by connecting you to others who have experienced similar losses.

It’s not uncommon to feel irritated or frustrated when people in your life who haven’t experienced loss attempt to console you or express messages of concern.

No matter how kind or well intentioned their words are, they simply don’t understand what you’re going through.

In a support group, you can find a shared understanding, along with validation of the emotions you feel unable to express to anyone else.

There’s no shame in needing extra support as you begin processing your parent’s death. In fact, many counselors specialize in providing grief support.

A therapist can offer validation and guidance as you begin working through the complex emotions that tend to accompany grief. Grief counselors can also teach coping strategies you can use as you begin adjusting to life without your parent.

Grief counselors can also teach coping strategies you can use as you begin adjusting to life without your parent.

Therapy also offers a safe space to unpack any guilt, anger, resentment, or other lingering emotions around a deceased parent’s toxic or hurtful behavior, and to achieve some level of closure.

If you want to forgive your parent but feel unsure how to begin, a therapist can provide compassionate support.

Our guide to finding affordable therapy can help you get started.

Grief is a complex process that can take time.

Everyone will experience their own journey of grief differently. Some people may take longer than others to fully grieve the loss of a person.

Feelings of grief may come and go, with the intensity of grief going up and down at various times. This can sometimes may it hard to feel you have made any progress with your grief.

It is possible you may feel better for a period of time, only to have feelings of grief return. This is normal.

This is normal.

Some people may find grief is worse around the holidays or other significant dates.

The pain associated with grief may lessen over time, but it is still possible to feel emotionally connected to a person who has died for years.

Grief after a parent’s death can drain you and leave you reeling, no matter what kind of relationship you had.

Remember, grieving is a normal, healthy process, one that looks different for everyone. Treat yourself with kindness and compassion, embracing patience as you take the time you need to work through your loss.

Crystal Raypole has previously worked as a writer and editor for GoodTherapy. Her fields of interest include Asian languages and literature, Japanese translation, cooking, natural sciences, sex positivity, and mental health. In particular, she’s committed to helping decrease stigma around mental health issues.

10 Tips for Handling the Grief

The finality of death can feel almost unbelievable, particularly when it strikes a parent, someone whose presence in your life may have never wavered.

You finished growing up and successfully reached adulthood, but you still needed (and expected to have) your parents for years to come.

The loss of their support, guidance, and love can leave a vast emptiness and pain that might seem impossible to heal, even if their death was expected.

Or, maybe you and your parent were estranged or had a complicated relationship, resulting in a roller coaster of conflicting emotions.

Yet the world at large may expect you to recover from your grief fairly quickly — after the prescribed 3 days of bereavement leave, perhaps padded with a few extra days of personal time — and get back to business.

There’s no right or wrong way to grieve the loss of a parent, but these strategies can offer a starting place as you begin to acknowledge your loss.

Sadness is common after the loss of a parent, but it’s also normal for other feelings to take over. You may not feel sad, and that’s OK, too. Perhaps you only feel numb, or relieved they’re no longer in pain.

Grief opens the gate to a flood of complicated, often conflicting emotions. Your relationship with your parent might have had plenty of challenges, but it still represented an important key to your identity.

They created you, or adopted and chose to raise you, and became your first anchor in the world.

After such a significant loss, it’s only natural to struggle or experience difficulties coming to terms with your distress.

You might experience:

- anger or frustration

- guilt, perhaps for not contacting them frequently or not being present for their death

- shock and emotional numbness

- confusion, disbelief, or a sense of unreality

- hopelessness or despair

- physical pain

- mental health symptoms, including depression or thoughts of suicide

- relief that they’re no longer in pain

No matter how the loss hits you, remember this: Your feelings are valid, even if they don’t line up with what others think you “should” feel.

People react to grief in different ways, but it’s important to let yourself feel all of your feelings.

There’s no single right way to grieve, no set amount of time after which you can automatically expect to feel better, no stages or steps to check off a list. This in itself can be difficult to accept.

Denying your feelings may seem like a route toward faster healing. You might also get the message that others expect you to bury your grief and move on before you’ve come to terms with your loss.

Remind yourself grief is a difficult process as well as a painful one. Try to not let the opinions of others sway you.

Some people work through grief in a short time and move forward with the remnants of their sadness safely tucked away. Others need more time and support, no matter how expected the death was.

If your parent passed after a long illness, you may have had more time to prepare, but no amount of preparation makes your grief any less significant when it hits. You might still feel stunned and disbelieving, especially if you held out hope for their recovery to the very end.

You might still feel stunned and disbelieving, especially if you held out hope for their recovery to the very end.

The unexpected death of a parent still in middle age, on the other hand, may force you to confront your own mortality, a battle that can also complicate grief.

As you navigate the days, weeks and months following the loss of a parent, you may experience a variety of emotions and feelings. These may also change over time.

Some people may go through what is referred to as the five stages of grief. These include:

- Stage one: denial. This can feel like being in a state of shock or confusion surrounding the death of a parent. A person in this stage may feel the need to keep busy all the time, or do what they can to avoid dealing with the issue.

- Stage two: anger. A person in this stage may feel frustration, rage or even resentment. They may display behaviors that are irritable, sarcastic or pessimistic. They may also get into arguments or turn to alcohol or drugs.

- Stage three: bargaining. A person in the bargaining phase of grief may have feelings of shame, guilt, blame or insecurity. They may ruminate on matters of the past or worry about the future. They may judge themselves or others, overthink and worry.

- Stage four: depression. During this stage, people may feel hopeless, sad, disappointed and overwhelmed. They may experience changes to their sleep or appetite, have a lack of interest in social activities and have reduced energy.

- Stage five: acceptance. People in the final stage of grief may feel a sense of self-compassion, courage, pride and even wisdom. They may accept reality for what it is, be present in the moment as it happens and be able to adapt and cope with the situation.

Grief often has a significant impact on daily life:

- Your state of mind might change rapidly, without warning.

- You might notice sleep problems, more or less of an appetite, irritability, poor concentration, or increased alcohol or substance use.

- You might find it tough to work, take care of household tasks, or see to your own basic needs.

- The need to wrap up your parent’s affairs may leave you overwhelmed, particularly if you have to handle this task alone.

Some people find comfort in the distraction of work, but try to avoid forcing yourself to return before you feel ready, if possible. People often throw themselves into work, taking on more than they can comfortably handle to avoid scaling the ever-present wall of painful emotions.

Finding a balance is key. Some distraction can be healthy, provided you still make time to address your feelings.

It might seem difficult, even inconsiderate, to dedicate time to self-care, but prioritizing your health becomes even more important as you recover from your loss.

Keep these tips in mind:

- Get enough sleep. Set aside 7 to 9 hours each night for sleep.

- Avoid skipping meals.

If you don’t feel hungry, choose nutritious snacks and small meals of mood-boosting foods.

If you don’t feel hungry, choose nutritious snacks and small meals of mood-boosting foods. - Hydrate. Drink plenty of water.

- Keep moving. Stay active to energize yourself and help raise your spirits. Even a daily walk can help.

- Aim for moderation. If you drink alcohol, try to stay within recommended guidelines. It’s understandable to want to numb your pain, but increased alcohol use can have health consequences.

- Reset. Rest and recharge with fulfilling hobbies, such as gardening, reading, art, or music.

- Be mindful. Meditating or keeping a grief journal can help you process emotions.

- Speak up. Talk to your healthcare provider about any new physical or mental health symptoms. Reach out to friends and other loved ones for support.

Talking to family members and other loved ones about what your parent meant to you and sharing stories can help keep their memory alive.

If you have children, you might tell stories about their grandparent or carry on family traditions that were important in your childhood.

It might feel painful at first to reminisce, but you may find that your grief begins to ease as the stories start flowing.

If you feel unable to openly talk about your parent for the moment, it can also help to collect photographs of special times or write them a letter expressing your grief about their passing.

Not everyone has positive memories of their parents, of course. And people often avoid sharing negative memories about people who’ve passed. If they abused, neglected, or hurt you in any way, you may wonder whether there’s any point to dredging up that old pain.

If you’ve never discussed or processed what happened, however, you might find it even harder to heal and move forward after their death. Opening up to a therapist or someone else you trust can help lighten the load.

Many people find that specific actions can help honor a deceased parent and offer a measure of comfort.

You might consider:

- creating a small home memorial with photos and mementos

- planting their favorite tree or flower in your backyard

- adopting their pet or plants

- continuing work they found meaningful, like volunteering or other community service

- donating to their preferred charity or organization

Upon hearing the news that an estranged parent has passed away, you might feel lost, numb, angry, or surprised by your grief. You might even feel cheated of the opportunity to address past trauma or unresolved hurt.

Life doesn’t always give us the answers we seek or the solutions we crave. Sometimes you just have to accept inadequate conclusions, however unfinished or painful they feel.

Knowing you can no longer address the past might leave you feeling as if you’re doomed to carry that hurt forever.

Instead of clutching tight to any lingering bitterness, try viewing this as an opportunity to let go of the past and move forward — for your sake.

Some things are truly difficult to forgive, but harboring resentment only harms you, since there’s no one left to receive it.

A letter can help you express things previously left unsaid and take the first steps toward processing the painful and complex feelings left after their death. Working with a therapist can also help you begin to heal the pain of the past.

Friends and loved ones may not know exactly what to say if they haven’t faced the same type of loss, but their presence can still help you feel less alone.

It’s normal to need time to mourn privately, but at the same time, completely isolating yourself generally doesn’t help. The companionship and support of those closest to you can help keep you from being overwhelmed by your loss.

Beyond providing a supportive presence, friends can also help out with meals, child care, or handling errands.

Just be sure to let others know what you need.

If you want to talk about your parent, you might ask if they’re able to listen. If you’d like a break from thinking about their death, you might ask them to join you in a distracting activity, whether that’s playing a game, watching a movie, or working on a project around the house.

If you’d like a break from thinking about their death, you might ask them to join you in a distracting activity, whether that’s playing a game, watching a movie, or working on a project around the house.

You might notice family relationships begin to change after your parent’s death.

Your remaining parent, if still living, may now look to you and your siblings for support. Your siblings, if you have any, are facing the same loss. Their unique relationship with your parent can mean they experience the loss differently than you do, too.

It’s not unusual for siblings to experience conflict or slowly drift apart, particularly if you disagreed over your parent’s end-of-life care.

Yet family bonds can provide comfort during grief. You’ve experienced the same loss, even though that person meant something different to each of you.

If you cherish your family relationships, make an effort to strengthen those bonds and draw closer together.

This might mean reaching out more often than in the past or inviting them more regularly to visit and participate in family gatherings.

It can also mean listening with empathy when a sibling who had a difficult relationship with your parent now finds it hard to come to terms with their conflicting emotions.

Friends and loved ones may offer comfort, but a grief support group can fulfill a different kind of social need by connecting you to others who have experienced similar losses.

It’s not uncommon to feel irritated or frustrated when people in your life who haven’t experienced loss attempt to console you or express messages of concern.

No matter how kind or well intentioned their words are, they simply don’t understand what you’re going through.

In a support group, you can find a shared understanding, along with validation of the emotions you feel unable to express to anyone else.

There’s no shame in needing extra support as you begin processing your parent’s death. In fact, many counselors specialize in providing grief support.

A therapist can offer validation and guidance as you begin working through the complex emotions that tend to accompany grief. Grief counselors can also teach coping strategies you can use as you begin adjusting to life without your parent.

Grief counselors can also teach coping strategies you can use as you begin adjusting to life without your parent.

Therapy also offers a safe space to unpack any guilt, anger, resentment, or other lingering emotions around a deceased parent’s toxic or hurtful behavior, and to achieve some level of closure.

If you want to forgive your parent but feel unsure how to begin, a therapist can provide compassionate support.

Our guide to finding affordable therapy can help you get started.

Grief is a complex process that can take time.

Everyone will experience their own journey of grief differently. Some people may take longer than others to fully grieve the loss of a person.

Feelings of grief may come and go, with the intensity of grief going up and down at various times. This can sometimes may it hard to feel you have made any progress with your grief.

It is possible you may feel better for a period of time, only to have feelings of grief return. This is normal.

This is normal.

Some people may find grief is worse around the holidays or other significant dates.

The pain associated with grief may lessen over time, but it is still possible to feel emotionally connected to a person who has died for years.

Grief after a parent’s death can drain you and leave you reeling, no matter what kind of relationship you had.

Remember, grieving is a normal, healthy process, one that looks different for everyone. Treat yourself with kindness and compassion, embracing patience as you take the time you need to work through your loss.

Crystal Raypole has previously worked as a writer and editor for GoodTherapy. Her fields of interest include Asian languages and literature, Japanese translation, cooking, natural sciences, sex positivity, and mental health. In particular, she’s committed to helping decrease stigma around mental health issues.

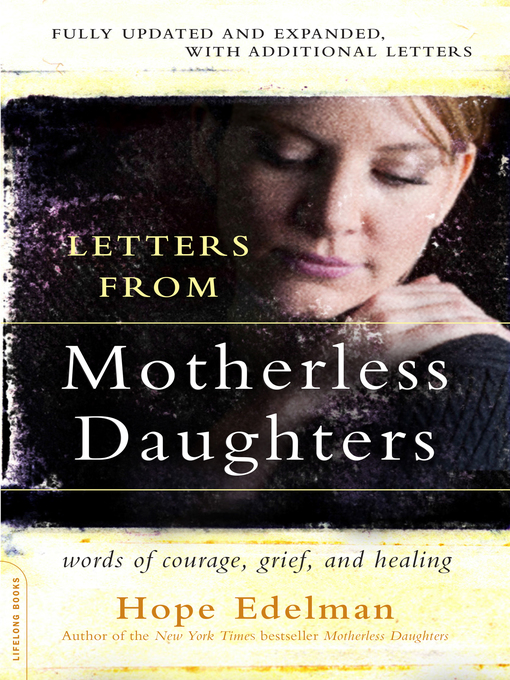

"My world collapsed." How a girl experiences the loss of her mother

The book “Daughters without mothers. Coping with Loss” is based on interviews with hundreds of women who have lost a parent, contemporary research, and the author's own experience. Writer Hope Edelman tries to figure out how to deal with the death of a loved one

Coping with Loss” is based on interviews with hundreds of women who have lost a parent, contemporary research, and the author's own experience. Writer Hope Edelman tries to figure out how to deal with the death of a loved one

The loss of a mother is inevitable, but it is this event in every woman's life that divides her life into before and after, leaving an indelible imprint on her personality. Hope Edelman's Motherless Daughters. How to survive the loss" was translated into 20 languages, the Russian version is published in early April by the publishing house "Peter". Forbes Woman publishes an excerpt about how children and adolescents experience the loss of a parent.

[[{"fid":"330819","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":"","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0] [value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false,"external_url":""},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format ":"default","alignment":"","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false,"external_url":""} },"attributes":{"style":"height: 650px; width: 650px;","class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"1"}}]]

Psychologists have debated for decades whether children and adolescents can mourn the death of a loved one. Adults take out their emotions on different people - spouses, lovers, children, close friends and themselves. And children usually direct them to one or both parents. When a girl says, “My mother died when I was 12 and my world collapsed,” she is not exaggerating.

Adults take out their emotions on different people - spouses, lovers, children, close friends and themselves. And children usually direct them to one or both parents. When a girl says, “My mother died when I was 12 and my world collapsed,” she is not exaggerating.

Many grief professionals today agree that fully adjusting to the loss of a parent requires elements that children often do not have. This is a mature understanding of death, speech development and the courage to talk about your feelings. It is the realization that the intense pain is not eternal, and the ability to shift the emotional dependency from the deceased parent onto oneself before becoming attached to someone else. These qualities develop as they grow older: the child, like a train, picks up new passengers - skills - at each stage. At the time of the death of a parent, such qualities are usually few in a child.

This doesn't mean children can't grieve, they just do it their own way. The process of experiencing childhood grief is longer and occurs as cognitive and emotional abilities develop. A five-year-old child who thinks that death is a long dream may realize in six years that his mother will not return. He will have to endure the sadness and anger that will arise with a new awareness, even though six years have passed since the moment of death.

The process of experiencing childhood grief is longer and occurs as cognitive and emotional abilities develop. A five-year-old child who thinks that death is a long dream may realize in six years that his mother will not return. He will have to endure the sadness and anger that will arise with a new awareness, even though six years have passed since the moment of death.

In my opinion, the best example of this process is the story of 20-year-old Jennifer. She was four years old when her mother committed suicide. As a child, Jennifer only knew the basic facts about her mother's death. However, she was able to understand the truth only when her cognitive and emotional abilities were formed.

“My mother got carbon monoxide poisoning in the garage,” she explains. “For a long time I thought the fuel tank cap fell off the car and she died from it. It sounds ridiculous, but I was sure of it. Many years later, in the eleventh grade of school, I finally realized that my mother did everything on purpose. I was telling someone about this and suddenly I thought, “This is stupid. How can you die from a fuel tank cap?” Years after her mother's death, Jennifer began a new cycle of grief. She is still trying to accept the truth.

I was telling someone about this and suddenly I thought, “This is stupid. How can you die from a fuel tank cap?” Years after her mother's death, Jennifer began a new cycle of grief. She is still trying to accept the truth.

Adults usually begin the process of grief immediately after a loss, but children do it in fits and starts. They grieve throughout their lives, sinking in and out of their grief, experiencing intense outbursts of anger and sadness that alternate with long periods of neglect. “Children know how much pain they can take at any given moment, and when they reach the limit, they just shut themselves off from it, switch to something else,” explain Mary Ann and James Emsweiler, authors of Help Your Child Grieve (Guiding Your Child rough Grief).

Adults often confuse this process with grief blocking, thinking that their child does not understand what has happened or is in denial about the loss. In fact, he understands well that his mother is no more. But instead of openly grieving, the child often speaks to adults through play. For example, a girl who lost her mother in the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, could return from a funeral and go to her toy box, which she did not pay attention to before the funeral. The game reflects her feelings. If a girl builds a tall tower of blocks several times and destroys it, this is probably how she expresses her sense of loss.

But instead of openly grieving, the child often speaks to adults through play. For example, a girl who lost her mother in the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, could return from a funeral and go to her toy box, which she did not pay attention to before the funeral. The game reflects her feelings. If a girl builds a tall tower of blocks several times and destroys it, this is probably how she expresses her sense of loss.

Psychologists at the Barr-Harris Center for Childhood Grief in Chicago have long observed that a child's reaction to the death of a parent is directly related to the behavior of the remaining parent. “Loss is felt harder when the surviving parent recovers more slowly, becomes seriously depressed, acts like nothing happened, or is so exhausted that the situation is out of control,” says Nan Bernbaum, who worked at the Center in the 1990s. .

- We have noticed that children feel the loss six or nine months after the death of a parent, when the remaining parent recovers a little. Children need psychological support to survive intense stress. Parents left behind are forced to piece together the pieces of their lives and return to their normal activities before the children feel safe and able to express their grief. Sometimes the remaining parent comes to his senses after a year. In this case, the child will begin to grieve and show intense reactions a year and a half after the loss. Children cannot get past the stage of grief where the remaining parent left off. If he is stuck at a particular stage, most likely, the child will also be stuck there.

Children need psychological support to survive intense stress. Parents left behind are forced to piece together the pieces of their lives and return to their normal activities before the children feel safe and able to express their grief. Sometimes the remaining parent comes to his senses after a year. In this case, the child will begin to grieve and show intense reactions a year and a half after the loss. Children cannot get past the stage of grief where the remaining parent left off. If he is stuck at a particular stage, most likely, the child will also be stuck there.

Researchers have found that children who have lost a parent need two conditions to recover - a balanced surviving parent who meets their physical and emotional needs, and an open and honest discussion of death and its impact on the family. Physical care is not enough. A child who can share sadness and feel safe at home is more likely to cope with pain and avoid major long-term stress. But if he encounters constant difficulties - for example, his father cannot recover from a loss, his stepmother rejects him, the situation at home is unstable - he has a long way to go.

Adolescents are very attached to peer groups and have the ability to think abstractly, which allows them to jump from the thought “My mother is no more” to the thought “My life will never be the same”. Their process of experiencing grief is close to that of adults, but the sensations are still limited by the level of development. Some psychologists consider adolescence to be a form of mourning for a bygone childhood and the dissipated image of all-powerful caring parents. In their opinion, until we complete this process of experiencing grief in adolescence, we will not be able to grieve for a departed loved one. A period as unstable and fickle as adolescence can prepare us for the need to let people go.

Women who lost their mothers during their teenage years often report that they were unable to cry at the time of the loss, or even months and years later. Having matured, they often blame and reproach themselves for this, ask questions: what is wrong with me? why couldn't I cry? what is my problem?

34-year-old Sandy, whose mother died of cancer 20 years ago, still remembers her confusion. “I never cried at a funeral,” she admits. “I didn’t want anyone to know how a 14-year-old girl feels. I remember sitting in the funeral parlour, chatting merrily with my friends because I didn't know how to behave. You know, I didn't want to act like the loss upset me. I didn't know how to behave. But my family owned a large area planted with forests. I went there, sat on a fallen tree and cried a lot, although I didn’t shed a tear at the funeral.

“I never cried at a funeral,” she admits. “I didn’t want anyone to know how a 14-year-old girl feels. I remember sitting in the funeral parlour, chatting merrily with my friends because I didn't know how to behave. You know, I didn't want to act like the loss upset me. I didn't know how to behave. But my family owned a large area planted with forests. I went there, sat on a fallen tree and cried a lot, although I didn’t shed a tear at the funeral.

After a serious loss, older children and adolescents do not cry as freely as adults. Adolescents are often afraid of their deepest emotions. If a small child can burst into tears without thinking of a tantrum, a teenager who feels that he can “fall apart” in front of everyone is afraid to show his grief.

If a parent dies while a girl is trying to prove her independence from the family, she may associate tears and other emotional outbursts with a regression to childhood. She equates crying with being childish and avoids public tantrums. The loneliness experienced by a girl after the death of her mother is exacerbated by the distance that is a normal part of adolescence. As a result, she feels doubly alone, afraid to express grief.

The loneliness experienced by a girl after the death of her mother is exacerbated by the distance that is a normal part of adolescence. As a result, she feels doubly alone, afraid to express grief.

I would like to write that everyone in my family was able to publicly express feelings, that we discussed the death of my mother and her life, and that all children received important emotional support from their father. But it's not. My father could not simultaneously carry the burden of his own grief and the unexpected responsibility for three children that fell on his shoulders. Plus, he's not used to asking for help. It is unlikely that at that time he discussed with someone the death of his wife. Father never talked about it with us. When at dinner someone accidentally said the name of my mother, tears appeared in his eyes. He went to his room, leaving me, my sister and brother to silently look at the plates of food. When a single parent is on the verge of a breakdown, it's very scary. We tried to prevent a catastrophe as far as possible. We had no one except for our father, we could not lose him either. When we realized what words pissed off my father, silence fell over us like a thick fog. Two months after my mother died, we stopped talking about her altogether.

We tried to prevent a catastrophe as far as possible. We had no one except for our father, we could not lose him either. When we realized what words pissed off my father, silence fell over us like a thick fog. Two months after my mother died, we stopped talking about her altogether.

Silence and suppression of feelings turned me into an emotional doll, artificial and numb, with ideal proportions that do not exist in life. The night my mother died, I moved into a zone of false emotions: no tears, no grief, no reaction other than restraint and a great desire to maintain the status quo. If I could not control the external chaos, at least I tried to balance it with internal restraint. How to succumb to the intense emotions churning inside me? At and after the funeral, my father told his relatives that I was the backbone of the family. “Without Hope, our family would fall apart,” he said, and everyone nodded in unison.

Of course, such praise convinced me of the need to maintain an insensitive mask. In the early years, I never broke down. My mother always allowed children to cry, but my father was more of an advocate for suppression of emotions. Someone should have told me that there was nothing wrong with anger and despair, but I was only praised for my pseudo-mature responsibility. Perhaps it sounds silly to a 17-year-old girl that she needed permission to show her emotions openly. I would have thought the same if I hadn't experienced it personally.

In the early years, I never broke down. My mother always allowed children to cry, but my father was more of an advocate for suppression of emotions. Someone should have told me that there was nothing wrong with anger and despair, but I was only praised for my pseudo-mature responsibility. Perhaps it sounds silly to a 17-year-old girl that she needed permission to show her emotions openly. I would have thought the same if I hadn't experienced it personally.

Families like mine are not uncommon. Many consider even a harmless display of grief to be a reminder of loss and do not allow themselves to acknowledge the pain of the family. Girls who have lost their mothers and are left to live with their fathers are particularly disadvantaged. It is still accepted in our society that women express emotions and men suppress them. Fathers can feel grief just as intensely as the rest of the family, but men who are used to suppressing their feelings, keeping everything under control and solving problems, often do not know how to show emotions in public and cannot stand it. Leslie, 20, lost her mother at 17. “My father sent me a clear signal: “Don’t start crying, otherwise we will fall apart,” she recalls. He really thought so. In my home, grief, mourning and crying were considered something dangerous. We were not allowed to cry and grieve. I regret that I didn’t tell my father then: “It’s not true, dad.” I regret not crying. Then I would say to him, “See? Nothing happened. We didn't get hit by lightning." He would cry too, so what? What is dangerous about this? I cried a lot when I was in therapy. Then I got angry at the psychologist. Nothing bad happened. I think everyone in my family believed that my emotions were fraught with a huge negative force. Then I considered myself omnipotent. Of course it wasn't."

Leslie, 20, lost her mother at 17. “My father sent me a clear signal: “Don’t start crying, otherwise we will fall apart,” she recalls. He really thought so. In my home, grief, mourning and crying were considered something dangerous. We were not allowed to cry and grieve. I regret that I didn’t tell my father then: “It’s not true, dad.” I regret not crying. Then I would say to him, “See? Nothing happened. We didn't get hit by lightning." He would cry too, so what? What is dangerous about this? I cried a lot when I was in therapy. Then I got angry at the psychologist. Nothing bad happened. I think everyone in my family believed that my emotions were fraught with a huge negative force. Then I considered myself omnipotent. Of course it wasn't."

Grief doesn't go away when we try to lock it up in a remote place, but that's what many of us are advised to do: don't talk about the pain and it will go away. Anyone who has tried this approach knows how wrong it is. “In the end, it’s not the death of your mother that pisses you off,” says 29-year-old Rachel, who lost her mother at 14, “but the fact that you can’t talk and think about it.” Sometimes silence, in which there is no place for a sound, is more intrusive than words. If you keep your mouth shut, sooner or later grief will come out - through the eyes, ears and pores.

“In the end, it’s not the death of your mother that pisses you off,” says 29-year-old Rachel, who lost her mother at 14, “but the fact that you can’t talk and think about it.” Sometimes silence, in which there is no place for a sound, is more intrusive than words. If you keep your mouth shut, sooner or later grief will come out - through the eyes, ears and pores.

Psychological assistance for those who have lost loved ones as a result of COVID-19

Psychological assistance for those who have lost loved ones as a result of COVID-19

- Home

The death of a loved one is always a great sorrow. Death from coronavirus adds additional pain to completely normal, but no less difficult experiences.

It is very important to understand that this is an event that cannot be experienced instantly, it takes time to believe in it, to accept it, to rebuild life taking it into account.

The very collision with the fact of the finiteness of the life of a loved one is very difficult to accept. This causes a strong feeling of helplessness and powerlessness. At the same time, it is known that in order to make plans and not live one day at a time, it is important for a person to feel his ability to control the situation, to believe that the future is predictable and can be influenced. Unfortunately, when faced with the death of a loved one, it is precisely these beliefs that must be partially revised. Otherwise, continuing to consider life completely controlled, a person begins to look for those responsible for what happened, sorting out what exactly those around him and himself could do. And then, instead of supporting each other in common pain, people disperse, severely injuring themselves and those around them.

This causes a strong feeling of helplessness and powerlessness. At the same time, it is known that in order to make plans and not live one day at a time, it is important for a person to feel his ability to control the situation, to believe that the future is predictable and can be influenced. Unfortunately, when faced with the death of a loved one, it is precisely these beliefs that must be partially revised. Otherwise, continuing to consider life completely controlled, a person begins to look for those responsible for what happened, sorting out what exactly those around him and himself could do. And then, instead of supporting each other in common pain, people disperse, severely injuring themselves and those around them.

In addition, the more difficult the relationship with the deceased, the more, oddly enough, one has to mourn. Indeed, in addition to the loss of real relationships in this case, a person loses and mourns the hope that these relationships will improve, conflicts will be resolved, there will be understanding and spiritual intimacy. It is important to remember this, not to beat yourself up and give yourself a time and place to mourn. At the same time, it is important to understand that, while experiencing this loss, you think about relationships with the deceased, remember, grieve. And that's completely normal. After all, to say goodbye to dreams, you need to understand what exactly you dreamed about.

It is important to remember this, not to beat yourself up and give yourself a time and place to mourn. At the same time, it is important to understand that, while experiencing this loss, you think about relationships with the deceased, remember, grieve. And that's completely normal. After all, to say goodbye to dreams, you need to understand what exactly you dreamed about.

At any death of a loved one, those around us face the reality of the finiteness of life for each of us. Which enhances our own feelings about ourselves, and raises important questions that are usually referred to as existential: what makes life meaningful, what is important for you, what you want to have time to do and what is scary not to do it, what you dreamed about and what can be done from it to translate into reality what kind of relationship you want, with whom the relationship is important.

Why can the death of a loved one from the coronavirus be especially difficult?

First, it shows the general danger of the situation. And since each of us hopes that neither he nor his loved ones fall into this percentage, this tragedy reinforces the general sense of danger and vulnerability.

And since each of us hopes that neither he nor his loved ones fall into this percentage, this tragedy reinforces the general sense of danger and vulnerability.

Secondly, when dying in a hospital, relatives do not always have the opportunity to care for him in the last days of his life and say goodbye to the deceased during his lifetime. This can generate feelings of guilt and regret, which increase grief and may prolong mourning.

Thirdly, death from coronavirus is also more difficult to experience due to the fact that, often, there is no opportunity to say goodbye to the deceased and hold funerals and other farewell events accepted in culture in the usual way, and share grief with all loved ones from - because of the rules related to the epidemic situation or because of the inability to take part in them because of their own poor health.

In addition, pain in experiencing the loss of a loved one from coronavirus can be added by the suddenness of death, which occurred against the background of positive dynamics and confidence in a favorable outcome.

At the same time, if a person died precisely in a pandemic and from covid, the grief of his loved ones is not relieved by the knowledge that there is a pandemic around and many are dying. On the contrary, it can interfere with mourning and prolong it. Therefore, it is important to remember that the loss of a loved one, regardless of the period when it occurred, is bitter and significant.

It is important to remember that the loss of several loved ones from the coronavirus greatly aggravates the experience of grief.

How can you help yourself get through this period?

Feeling of depression, grief, regular mental return to a deceased loved one, sadness, tears are completely normal in the course of mourning and help to gradually accept the loss, come to terms with it and move on.

But there is something that can ease this difficult period:

- If it is not possible to personally meet at the funeral and commemoration with other people to whom the deceased was also dear, then arrange a meeting of memory in Skype, Zoom, google meet or WhatsApp.

This will provide an opportunity to remember the deceased together and make it easier for everyone to experience grief.

This will provide an opportunity to remember the deceased together and make it easier for everyone to experience grief. - Allow yourself to cry and grieve. Ask your friends what time to contact if you feel you need to talk about the deceased, your relationship with him, his death.

- Allow yourself to think about your relationship with the deceased, about what was important to you, what you liked and what you didn't.

- Take special time to take care of your physical well-being: make sure that you eat on time, drink enough fluids, go to bed on time to keep you warm and comfortable.

- Art helps some people in experiencing grief: both to create themselves and to get acquainted with the work of other people dedicated to grief. It can be, for example, poetry, prose, music, painting.

- Think about what you could do in memory of a loved one who has died.

When to seek professional help:

- If you have persistent sleep problems.