How to make yourself sleepwalk

Sleepwalking - NHS

Sleepwalking is when someone walks or carries out complex activities while not fully awake.

It usually happens during a period of deep sleep. This peaks during the early part of the night, so sleepwalking tends to happen in the first few hours after falling asleep.

Sleepwalking can start at any age but is more common in children. It's thought 1 in 5 children will sleepwalk at least once. Most grow out of it by the time they reach puberty, but it can sometimes persist into adulthood.

Why some people sleepwalk

The exact cause of sleepwalking is unknown, but it seems to run in families. You're more likely to sleepwalk if other members of your close family have or had sleepwalking behaviours or night terrors.

The following things can trigger sleepwalking or make it worse:

- not getting enough sleep

- stress and anxiety

- infection with a high temperature, especially in children

- drinking too much alcohol

- taking drugs

- certain types of medicine, such as some sedatives

- being startled by a sudden noise or touch, causing abrupt waking from deep sleep

- waking up suddenly from deep sleep because you need to go to the toilet

Other sleep disorders that can cause you to frequently wake up suddenly during the night, such as obstructive sleep apnoea and restless legs syndrome, can also trigger a sleepwalking episode.

Taking steps to prevent some of these triggers – such as making sure you get enough sleep, and working on strategies to deal with and reduce stress – will often help.

What happens when a person sleepwalks

In some episodes of sleepwalking, a person may just sit up in bed and look around, briefly appearing confused. Others may get out of bed and walk about, open cupboards, get dressed or eat, and they may appear agitated.

In extreme cases, the person may walk out of the house and carry out complex activities, such as driving a car.

The eyes are usually open while someone is sleepwalking, although the person will look straight through people and not recognise them. They can often move well around familiar objects.

If you talk to a person who is sleepwalking, they may partially respond or say things that do not make sense.

Most sleepwalking episodes last less than 10 minutes, but they can be longer. At the end of each episode, the person may wake up, or return to bed and go to sleep.

They will not normally have any memory of it in the morning or may have patchy memory. If woken while sleepwalking, the person may feel confused and not remember what happened.

What to do if you find someone sleepwalking

The best thing to do if you see someone sleepwalking is to make sure they're safe. If undisturbed, they will often go back to sleep again. Gently guide them back to bed by reassuring them.

Do not shout or startle the person and do not try to physically restrain them unless they're in danger, as they may lash out.

When to get medical advice

Occasional sleepwalking episodes do not usually need medical attention. Sleepwalking is rarely a sign of anything serious and may get better with time, particularly in children.

Sleepwalking is rarely a sign of anything serious and may get better with time, particularly in children.

But, you should consider seeing a GP if sleepwalking happens frequently, you're concerned a person may be at risk of injuring themselves or others, or the episodes continue or start in adult life.

The GP may refer you to a specialist sleep centre, where your or your child's sleep history can be discussed in more detail. If appropriate, sleep studies can be arranged to exclude other conditions that could be triggering the sleepwalking, such as obstructive sleep apnoea or restless legs syndrome.

Treatments for sleepwalking

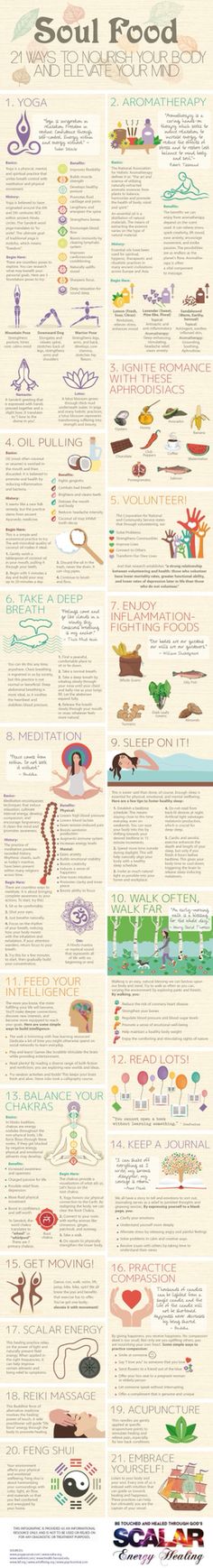

There's no specific treatment for sleepwalking, but it generally helps to try to get enough sleep and have a regular and relaxing routine before bedtime.

You may find the following advice helpful:

- try to go to bed at a similar time each night

- make sure your bedroom is dark and quiet when you go to sleep

- limit drinks before bedtime, particularly ones containing caffeine, and go to the toilet before going to sleep

- find ways to relax before going to bed, such as having a warm bath, reading or deep breathing

- if your child sleepwalks at the same time most nights, try gently waking them for a short time 15 to 30 minutes before they would normally sleepwalk – this may stop them sleepwalking by altering their normal sleep cycle

Read about how to establish a regular bedtime routine and healthy sleep tips for children.

Medicine is not usually used to treat sleepwalking. However, medicines such as benzodiazepines or antidepressants are sometimes used if you sleepwalk often or there's a risk you could seriously injure yourself or others. These medicines can help you sleep and may reduce the frequency of sleepwalking episodes.

Therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or hypnotherapy may sometimes be helpful.

Preventing accidents

It's important to keep the areas of your home where a person may sleepwalk free of breakable or potentially harmful objects and to remove any items they could trip over. It's also a good idea to keep windows and doors locked.

If your child sleepwalks, do not let them sleep on the top bed of a bunk bed. You may want to fit safety gates at the top of the stairs.

It's also important to tell babysitters, relatives or friends who look after your child at night that your child may sleepwalk and what they should do if it happens.

Page last reviewed: 05 October 2021

Next review due: 05 October 2024

Surprising Habits That Lead to Sleepwalking

Millions of children and adults sleepwalk, putting their sleep and their safety at risk. Dr. Michael J. Breus, PhD, aka The Sleep Doctor, takes a look at some of the unexpected reasons why.

Ellica/Shutterstock

Up at night, still asleep

Have you ever awakened to find yourself bumping around the house, or flipping through a magazine at your kitchen table, with no memory of getting out of bed? You’re not alone. Sleepwalking—the medical term is somnambulism—is more common than many people think. The National Sleep Foundation estimates between 1 to 15 percent of the general population sleepwalks—and a 2016 study put its prevalence right in the middle of that range, at just under 7 percent.

Check out some funny stories of sleepwalkers’ activity.

Romrodphoto/Shutterstock

Sleepwalking can be scary

Most people have no memory of what they do during episodes of somnambulism. Still, it’s highly disconcerting to wake and find yourself not in bed where you expect to be. It can be especially disorienting for kids—and the parents who find their glassy-eyed children up but unresponsive during in the middle of the night. Children are more likely to sleepwalk than adults: Between the ages of 4-12, it’s estimated that 15 percent of children will have episodes of somnambulism. This may be because younger children spend greater amounts of time in the deepest stages of non-REM sleep. If you encounter a member of your household sleepwalking, whether child or adult, the best thing to do is to guide them gently back to bed.

Mita Stock Images/Shutterstock

Why do people sleepwalk?

Scientists are still figuring this one out. One of the primary reasons appears to be genetic. Somnambulism is an inherited trait—a 2015 study found children have three to seven times the risk of walking in sleep if one, or both, parents have a history of the sleep disorder. (Learn about how your mother’s health can affect your own.) But genes aren’t the only factor: There are many everyday habits and common conditions that increase the chances you’ll rise from bed to sleepwalk starting with the following.

One of the primary reasons appears to be genetic. Somnambulism is an inherited trait—a 2015 study found children have three to seven times the risk of walking in sleep if one, or both, parents have a history of the sleep disorder. (Learn about how your mother’s health can affect your own.) But genes aren’t the only factor: There are many everyday habits and common conditions that increase the chances you’ll rise from bed to sleepwalk starting with the following.

Diana Rui/Shutterstock

You don’t stick to a regular sleep schedule

Sleepwalking is an arousal disorder that takes place most commonly in the first third of the night when you’re in the deepest stages of non-REM sleep. When you sleepwalk, you’re in a mixed state of consciousness, experiencing an incomplete awakening that occurs as you move through non-REM sleep. A regular sleep schedule reinforces circadian rhythms, which regulate the body’s sleep-wake cycle. Irregular sleeping patterns undermine your circadian sleep rhythms and can change the flow of sleep among the different stages. You can reduce your risk for this parasomnia—and improve your health and performance—by sticking to a regular sleep routine. Check out these tips for sleeping better on a regular basis.

Irregular sleeping patterns undermine your circadian sleep rhythms and can change the flow of sleep among the different stages. You can reduce your risk for this parasomnia—and improve your health and performance—by sticking to a regular sleep routine. Check out these tips for sleeping better on a regular basis.

tommaso79/Shutterstock

You’re sleep deprived

Cutting your snooze-time short also raises your risks. Sleep deprivation also can lead to more complex behaviors during an episode: People may eat, drive a car, or attempt to undertake all sorts of activities. I’ve had patients report they’ve done laundry, re-arranged living room furniture, and cooked food on the stove. The most significant danger from walking in your sleep? Injury to yourself, or to your bed partner. On relatively rare occasions, sleepwalkers can be violent. Learn how your sleep problems might be interfering with your good health.

Dalaifood/Shutterstock

You have a magnesium deficiency

Lots of my patients are unaware of the importance of magnesium to health—and its connection to better sleep. This essential macro-mineral supports physical relaxation and deep, restorative sleep. A lack of magnesium can lead to insomnia and is also associated with somnambulism. Magnesium deficiency is all-too-common, unfortunately: Research shows nearly half of U.S. adults don’t get enough magnesium in their diets. Here are some other natural supplements that can boost sleep.

This essential macro-mineral supports physical relaxation and deep, restorative sleep. A lack of magnesium can lead to insomnia and is also associated with somnambulism. Magnesium deficiency is all-too-common, unfortunately: Research shows nearly half of U.S. adults don’t get enough magnesium in their diets. Here are some other natural supplements that can boost sleep.

pathdoc/Shutterstock

You get stressed out

That nagging anxiety you carry with you during the day? It undermines healthy sleep in general—and it also can increase your risk of walking in your sleep. Research shows psychological stress alters the physiological characteristics of non-REM sleep, including raising your heart rate. If you’re falling asleep agitated by stress, it can affect how your body moves through the different stages of sleep. Stress and sleep have a complex relationship—stress disrupts sound sleep, and poor quality or insufficient amounts of sleep make you more prone to stress. Read about how stress negatively affects the brain.

Read about how stress negatively affects the brain.

VAKSMAN VOLODYMYR/Shutterstock

You’re drinking at night

Alcohol is the most common sleep aid—research suggests 20 percent of American adults use alcohol to help them sleep. Drinking at night might make you nod off more quickly, but the truth is alcohol is a potent sleep disrupter. Alcohol interferes with your circadian rhythms and nightly sleep architecture—the natural flow of sleep through different stages. Drinking moderately—and occasionally—is the all-around wisest choice for sound sleep. Find out how alcohol can mess with your hormones.

Olena Yakobchuk/Shutterstock

You’re snoozing in a noisy environment

A loud sleep environment doesn’t just make it harder to fall asleep, it also makes you more likely to sleepwalk. We’re highly sensitive to noise, even after we’ve fallen asleep. Think about how quickly new parents wake to the sound of their babies crying, or how fast your eyes pop open at the sound of the bedroom door creaking open. Maintaining strong sleep hygiene habits will help you fall asleep more easily and stay both asleep and in bed throughout the night. Keep in mind, not all noise is disruptive to sleep. The key is to eliminate disruptive sounds and introduce soothing ones to your sleep environment. Check out these eight sounds that can help you snooze better.

Maintaining strong sleep hygiene habits will help you fall asleep more easily and stay both asleep and in bed throughout the night. Keep in mind, not all noise is disruptive to sleep. The key is to eliminate disruptive sounds and introduce soothing ones to your sleep environment. Check out these eight sounds that can help you snooze better.

Alexander Chaikin/Shutterstock

You travel a lot

Traveling can wreak havoc with your normal rhythms, increasing your risk of somnambulism. The irregular sleep schedule, the unfamiliar sleep environments, and the unusual noises all contribute. Travelers are also more likely to be sleep deprived than stay-at-home types who have a regular bedtime. If you’re logging massive numbers of frequent flier miles, you could find yourself more likely to be a sleepwalker. Be on the lookout for these uncomfortable effects that flying can have on your body.

fizkes/Shutterstock

You take medication

You’ve probably heard stories of people on sleeping pills doing bizarre things. Sedatives are one type of drug that can trigger somnambulism—but there are others. Antihistamines, stimulants, medications with tranquilizing and antipsychotic effects all can increase the risks of walking in your sleep. Any changes to your sleep patterns are important to discuss with your doctor, especially if you’re taking over-the-counter or prescription pills. Read up on the mistakes people make with their medications that you might not know about.

Sedatives are one type of drug that can trigger somnambulism—but there are others. Antihistamines, stimulants, medications with tranquilizing and antipsychotic effects all can increase the risks of walking in your sleep. Any changes to your sleep patterns are important to discuss with your doctor, especially if you’re taking over-the-counter or prescription pills. Read up on the mistakes people make with their medications that you might not know about.

SThanaphat/Shutterstock

You go to bed with a full bladder

My patients are often surprised to hear this habit can increase the chances they’ll sleepwalk during the night. The physical urge to relieve yourself while in a state of deep, non-REM sleep may lead to the mixed state of consciousness—active, but not awake—that characterizes somnambulism. Don’t load up on beverages near to bedtime, and don’t skip the final trip to the bathroom before lights out. It just might keep you safely in bed, sleeping soundly, for the duration of the night. Find out what other common nighttime habits might be ruining your sleep.

Find out what other common nighttime habits might be ruining your sleep.

fizkes/Shutterstock

You’re sick with a fever

As if being ill weren’t enough, your fever can lead to strolling while snoozing. Other medical conditions can contribute as well, such as arrhythmia, nighttime asthma, and disorders that involve nighttime seizures, such as epilepsy. Find out what doctors really recommend you do when you think you’re coming down with the flu.

tommaso79/Shutterstock

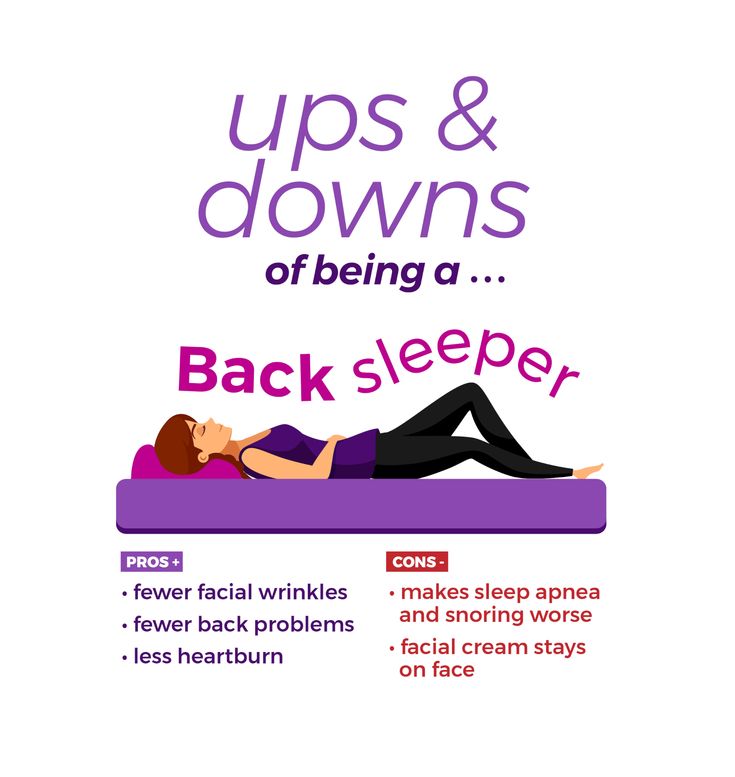

You have sleep apnea

A 2009 study found 1 in 10 people with obstructive sleep apnea may experience somnambulism or other parasomnias, including acting out in response to their dreams. Sleep apnea is characterized by repeated interruptions to normal breathing, which can lead to micro-arousals from sleep. This is a serious sleep disorder that requires treatment through your physician. The most common symptom is snoring—particularly if it’s loud and accompanied by gasping or choking. Want to know what kind of snoring problem you might have? Take this quiz. Read about the symptoms of sleep apnea and what they might be saying about your health.

The most common symptom is snoring—particularly if it’s loud and accompanied by gasping or choking. Want to know what kind of snoring problem you might have? Take this quiz. Read about the symptoms of sleep apnea and what they might be saying about your health.

wavebreakmedia/Shutterstock

You have acid reflux

This one catches lots of people by surprise, but it’s true. If you suffer from regular heartburn—a.k.a gastroesophageal reflux disorder (GERD)—you’re at greater risk for being a sleepwalker. (Learn about the diet that’s more effective than medication in relieving acid reflux.) I see a lot of patients with sleep problems stemming from GERD—it’s one of the most common causes of poor sleep in adults. GERD isn’t only linked to somnambulism. People with GERD are also more likely to experience insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea, and restless leg syndrome. The symptoms of GERD tend to worsen at night when you’re lying down. If you have nighttime GERD symptoms, it’s important to talk with your doctor—and ask specifically to be screened for sleep apnea.

If you have nighttime GERD symptoms, it’s important to talk with your doctor—and ask specifically to be screened for sleep apnea.

Fergus Coyle/Shutterstock

You have a psychological condition

Emotional stress and trauma can disrupt healthy sleep patterns and the circadian rhythms that support them, making sleepwalking more likely. Post-traumatic stress disorder and panic attacks are two psychological conditions associated with more frequent occurrence of somnambulism. Depression and anxiety are also linked to this parasomnia. Sleep can play a critical role in helping to treat and improve psychological distress. If you’re experiencing emotional strain or upheaval, don’t try to “tough” your way through it. Reach out to your physician or to a counselor to get the help you deserve.

Don’t miss these tips for sleeping better directly from sleep doctors.

Originally Published: March 21, 2018

Michael J. Breus, PhD, DABSM

Breus, PhD, DABSM

Michael J. Breus, Ph.D., is a Clinical Psychologist and both a Diplomate of the American Board of Sleep Medicine and a Fellow of The American Academy of Sleep Medicine. He was one of the youngest people to have passed the Board at age 31 and, with a specialty in Sleep Disorders, is one of only 168 psychologists in the world with his credentials and distinction. Dr. Breus is on the clinical advisory board of The Dr. Oz Show and is a regular contributor on the show (35+ times).

Dr. Breus is the author of the new book The Power of When, (September 2016) his third book ( #1 at Amazon for Time Management and #1 in Happiness, #28 overall) which is a ground breaking bio-hacking book proving that there is a perfect time to do everything, based on your hidden biological chronotype. Dr. Breus gives the reader the exact perfect time to have sex, run, a mile, eat a cheeseburger, ask your boss for a raise and much more.

His second book The Sleep Doctor’s Diet Plan: Lose Weight Through Better Sleep (Rodale Books; May 2011), discusses the science and relationship between quality sleep and metabolism. His first book, GOOD NIGHT: The Sleep Doctor’s 4-WeekProgram to Better Sleep and Better Health (Dutton/Penguin), an Amazon Top 100 Best Seller, has been met with rave reviews and continues to change the lives of readers.

Dr. Breus has supplied his expertise with both consulting and as a sleep educator (spokesperson) to brands such as Princess Cruise lines, Six Senses Hotel and Spa, Lighting Science Group, Advil PM, Breathe Rite, Crowne Plaza Hotels, Dong Energy (Denmark), Merck (Belsomra), and many more.

For over 14 years Dr. Breus has served as the Sleep Expert for WebMD. Dr. Breus also writes The Insomnia Blog and can be found regularly on, The Huffington Post, Psychology Today, Sharecare, and The Oz Blog.

Dr. Breus has provided editorial services for numerous medical and psychology peer-reviewed journals and has given hundreds of presentations to professionals and the general public. He has published original research and worked on grant funded projects and clinical trials.

His first book, GOOD NIGHT: The Sleep Doctor’s 4-WeekProgram to Better Sleep and Better Health (Dutton/Penguin), an Amazon Top 100 Best Seller, has been met with rave reviews and continues to change the lives of readers.

Dr. Breus has supplied his expertise with both consulting and as a sleep educator (spokesperson) to brands such as Princess Cruise lines, Six Senses Hotel and Spa, Lighting Science Group, Advil PM, Breathe Rite, Crowne Plaza Hotels, Dong Energy (Denmark), Merck (Belsomra), and many more.

For over 14 years Dr. Breus has served as the Sleep Expert for WebMD. Dr. Breus also writes The Insomnia Blog and can be found regularly on, The Huffington Post, Psychology Today, Sharecare, and The Oz Blog.

Dr. Breus has provided editorial services for numerous medical and psychology peer-reviewed journals and has given hundreds of presentations to professionals and the general public. He has published original research and worked on grant funded projects and clinical trials. Among his numerous national media appearances, Dr. Breus has been interviewed on CNN, Oprah, The View, Anderson Cooper, Rachel Ray, Fox and Friends, The Doctors, Joy Behar, The CBS Early Show, The Today Show, and Kelly and Michael. He is an expert resource for most major publications doing more than 100 interviews per year (WSJ, NYT, Wash Post, and most popular magazines). He also appears regularly on Dr. OZ and Sirius XM Radio.

Dr. Breus has been in private practice for 16 years and recently relocated his practice to Los Angles. And can be reached on the web at www.thesleepdoctor.com

Among his numerous national media appearances, Dr. Breus has been interviewed on CNN, Oprah, The View, Anderson Cooper, Rachel Ray, Fox and Friends, The Doctors, Joy Behar, The CBS Early Show, The Today Show, and Kelly and Michael. He is an expert resource for most major publications doing more than 100 interviews per year (WSJ, NYT, Wash Post, and most popular magazines). He also appears regularly on Dr. OZ and Sirius XM Radio.

Dr. Breus has been in private practice for 16 years and recently relocated his practice to Los Angles. And can be reached on the web at www.thesleepdoctor.com

Healthy sleep during the coronavirus pandemic: five tips to sleep like an Olympian

Sign up for our Context newsletter: it will help you understand the events.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,The constant stress of living in lockdown can take a toll on your sleep quality

A British Olympic team consultant offers five tips to help you get back to restful sleep, even in these turbulent times. And finally start sleeping like an Olympian.

And finally start sleeping like an Olympian.

Indeed, in these days full of anxious expectations and uncertainty, few people are able to fall asleep carelessly as soon as they put their head on the pillow.

Sleep specialist Luke Gupta, who works as a Senior Psychologist at the English Institute of Sport, Sheffield, helps top British Olympians fall asleep and stay asleep before important international competitions.

He offers his answers to five important questions to ask yourself before going to bed.

1. How calm are you before going to bed?

Nights like this are unavoidable: you go to bed, but you still feel unsatisfied after all that you have seen and heard during the day.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,When your sleep hours keep breaking, shifting, shifting, there's nothing good to look forward to

Or maybe you just had a nervous phone call or looked at the latest coronavirus reports.

Skip Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

Of course, we want to know what is happening in the world, we want to understand in which direction events are developing. And the problem, most likely, is in the time interval when we do this.

If our encounter with disturbing news happens right before going to sleep, then the brain goes into a state of high alert. And this means that then we will not be able to fall asleep for a long time.

In such cases, it is better not to even try to force yourself to sleep: you are unlikely to succeed quickly.

If you really need to read the latest news before going to bed, then it is better not to go to bed immediately after that, but to do something else - more soothing.

Do not rush to turn off the light, do not try to force yourself to sleep. Watch TV or read fiction, then go to bed. It is better to lie down later, but in a more relaxed mood.

2. Do you feel sleepy enough?

The state of drowsiness is like a rubber band. While we are awake, it stretches, and the more it stretches during the day, the faster we fall asleep when we go to bed (releasing the "rubber band").

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,In quarantine, some of us can afford to go to bed and wake up at our convenience

If you've been awake for a long time, there's a good chance you'll fall asleep quickly when the time comes go to bed.

Physical exercise and daily physical activity in general also increase your desire for sleep in the evening.

Athletes on the eve of important competitions usually want to go to bed early and get a good night's sleep - they believe that this will positively affect their performance.

But it doesn't work quite like that. If you go to bed earlier than usual, you are not yet ready for bed - that very rubber band has not been stretched enough yet.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Don't go to the fridge if you're not hungry, and force yourself to sleep if you're not sleepy.

Also, if you go to bed too early, you'll have extra time to worry before tomorrow's races. You will toss and turn in bed, thinking about the upcoming competitions.

So don't go to bed if you don't feel like sleeping for real. You don't go into the fridge if you're not hungry. But for some reason, we believe that we "need" to go to bed, even if we have no sleep in one eye.

You will get much better sleep if you go to bed when you really want to sleep.

3. Have you chosen the right time to sleep?

Even before we were in self-isolation, we went to bed at a certain time, guided by the fact that we had to get up early in the morning for work.

Now things are a bit different - some of us can afford to go to bed and get up when it's convenient for ourselves, and not when "necessary".

Image copyright Getty Images

Image caption,Exercise and general daytime physical activity increase your desire for sleep in the evening

Even though we can now manage our time more flexibly, it's important to stick to a regular daily schedule.

- You won't be able to sleep off! Long naps on weekends don't make up for the overall lack of sleep

Sleep is good for us when it's regular, and once we've figured out what time in bed is best for us, it's worth sticking with it. When the hours of sleep are constantly broken, transferred, shifted, do not expect anything good.

You don't have to go to bed and get up exactly at the same time, but it's better to have a certain buffer - a window of one hour - in the evening and in the morning, within which you can slightly shift the time of sleep. For example, lie in bed an extra hour in the morning or go to bed an hour later.

For example, lie in bed an extra hour in the morning or go to bed an hour later.

4. How familiar and calmly is the place where you sleep?

Most of us sleep in the bedroom. But when we talk about the place of sleep as familiar to us, we mean this: this place is used only for night sleep.

Or do you do something else in bed, like lying down to watch your Facebook feed during the day? Or sit on the sofa to watch TV? So is this place familiar to your dream?

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,The bedroom should be a place for sleeping only, not night-time with a laptop or phone

Try to avoid using the bed or sofa you sleep on at night for anything else . Agree with yourself: this place is only for sleeping.

If you still have to work sitting on this sofa, at least put a blanket on it during the day so that it looks different at night. It will also help that during the day you sit on it, and do not lie - after all, there is some kind of difference.

5. Did you have enough light during the day?

Our body is used to staying awake during daylight hours and sleeping at night.

- Why is daylight so important for good sleep? Scientist explains

- BBC presenter: how night shifts are killing me

- Night shifts can promote cancer

Now that we mostly stay at home and go out only when absolutely necessary, it is very difficult to get enough daylight. And then the difference between day and night becomes insignificant for our body.

In this case, you have to be more inventive: if you have your own house, then exercise in the yard; if you work at a computer - try to sit closer to the window. Then your body will distinguish day from night.

Medical myths: is it dangerous to wake sleepwalkers?

- Claudia Hammond

- BBC Future

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter to help you understand what's going on.

Image copyright Thinkstock

Everyone says you shouldn't wake sleepwalkers, that it might end badly for them. But is it? Correspondent BBC Future decided to figure out where the myth is and where the truth is.

Sometimes I get out of bed in the middle of the night and walk around my room or even my apartment without waking up.

And not only me: every fifth child regularly sleepwalks, and at least 40% have done so at least once.

The older we get, the less often this happens, but 1-2.5% of adults continue to wander in their sleep.

(More BBC Future articles in Russian)

Some sleepwalkers feel like they're running away from something scary. Some calmly and methodically rummage through drawers and cabinets, as if looking for something.

When I was little, I would go down to the living room without waking up and sit down with my parents to watch TV until they took me back to bed.

Everyone who has ever seen a sleepwalker will agree that this is a very strange state that combines the features of sleep and wakefulness.

As many have probably heard, in such cases it is usually advised not to wake the sleeper in any case: supposedly this is dangerous and will somehow harm him.

This is not entirely true, although, no doubt, it will be unpleasant for a sleepwalker to wake up at such a moment.

Sleep state

It is not known exactly why the brain gives the command to walk around in a dream, although we know a lot about what happens to a person after he falls asleep.

During the night, he goes through different phases of sleep, starting with light sleep, which becomes much deeper for about twenty minutes, and then again gives way to light sleep, then moving on to REM sleep.

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

This cycle repeats itself several times during the night, and each time the duration of REM sleep increases, so that by morning this phase takes the most time.

Most people dream during REM sleep. During this period, the body seems to be paralyzed so as not to accidentally start acting during sleep, but sleepwalking manifests itself in a phase of much deeper sleep.

This is a curious and paradoxical condition. The brain is active enough for a person to move, but not so active that he wakes up.

Recently, a study was conducted in the Milan Niguarda Hospital (Italy) of the brain waves of people prone to sleepwalking.

Scientists have found that while some areas of the brain were awake, the rest were in deep sleep. This indicates that the cause of sleepwalking is an imbalance between these two conditions.

Stories about sleepwalkers walking around with their arms outstretched like zombies are not true, but such people do have a fixed, as if unseeing look, and their attention is very difficult to attract.

Walking in a dream, people usually do not turn on the light and move around the house from memory.

Sleepwalkers in danger?

It is also not true that while walking in a dream, a person cannot do himself any harm - he can stumble, and if he finds himself in an unfamiliar place, he is really in danger: for example, having lost his way, a lunatic can open the front door and go out to street.

Professor Matthew Walker of the Sleep Pathology Clinic, a division of University College London Hospital, UK, once told me about a patient of his who left the house, got in his car and drove away - never waking up.

There was another case of a 15-year-old girl who was found in the cabin of a cargo crane at a height of forty meters - she climbed there in her sleep, curled up and continued to sleep.

Such cases are rare. Intermittent sleepwalking usually does not lead to any major problems, and most children outgrow the condition.

Image copyright, SPL

Image caption,Sleepwalkers walk around with arms outstretched like zombies, only in our fantasies

By this time their baby will usually begin to sleepwalk, and gently waking them up about 15 minutes before that time often helps to break the cycle.

So what should you do if one of your loved ones suffers from sleepwalking?

To begin with, the sleepwalker is so deeply asleep that he probably won't notice you at all even if you try to wake him up.

If he does wake up, you can disorientate him to such an extent that the person experiences stress.

We all know that feeling of complete confusion when the alarm goes off during deep sleep, and not during the light sleep phase that we usually find ourselves in by the time we wake up.

One day I had a real shock: I woke up from a roar and found myself standing barefoot in the kitchen in the middle of broken glass.

Walking in my sleep, I tried to pour myself some water, but, like most lunatics, I didn't turn on the light and broke the glass on the tap.

So waking up a sleepwalker won't give him a heart attack or put him in a coma, but the humane thing to do is not to wake him up at all, just take him back to bed so he doesn't hurt himself.

He will continue to sleep deeply, and in the morning, most likely, he will not remember his nightly walk.

Read the original of this article in English is available on the website BBC Future .

Disclaimer

All information contained in this article is provided for general information only and should not be taken as a substitute for advice from your physician or other healthcare professional.