Reactive attachment disorder history

Reactive Attachment Disorder - StatPearls

Continuing Education Activity

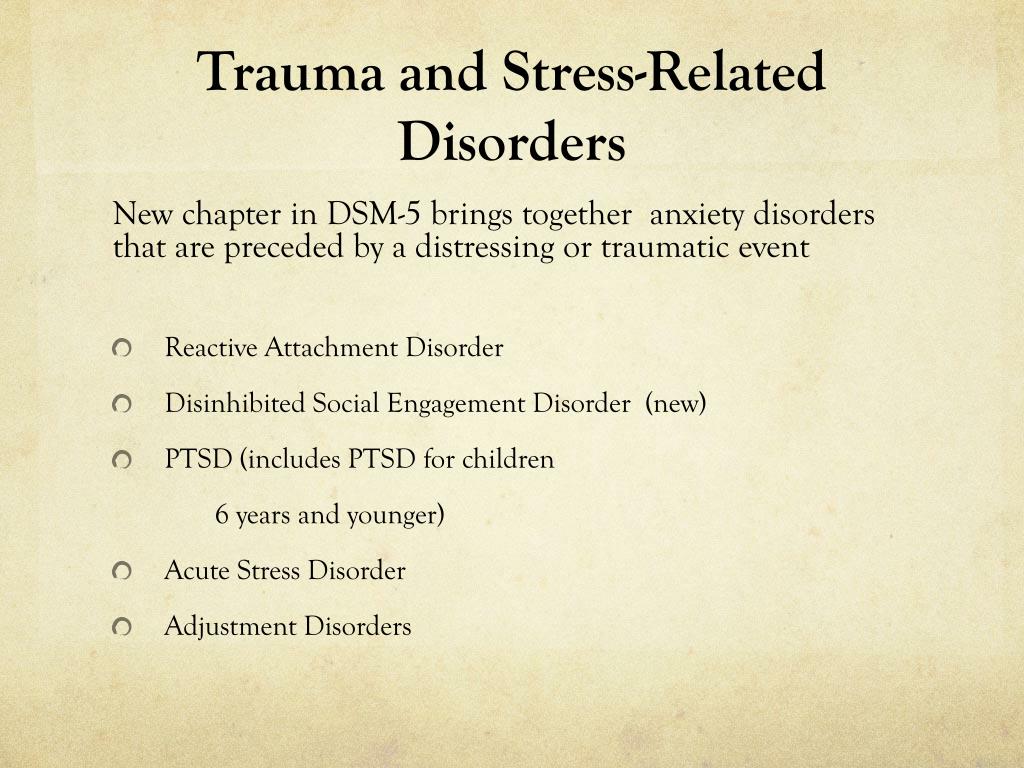

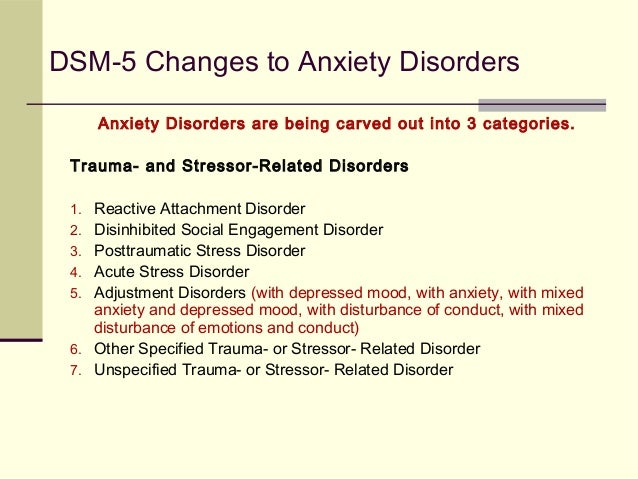

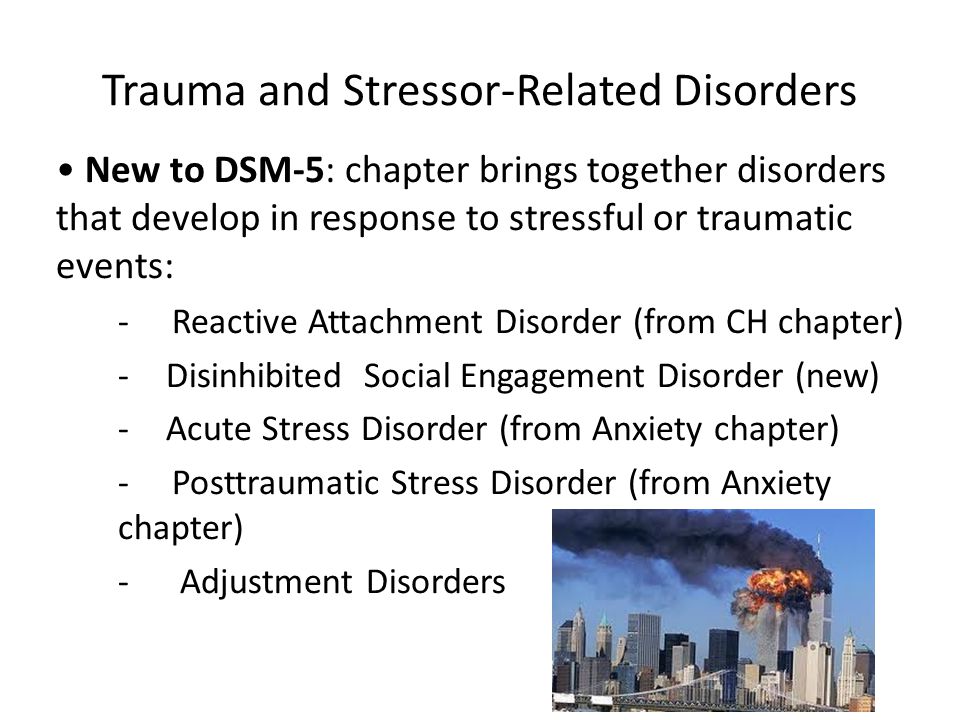

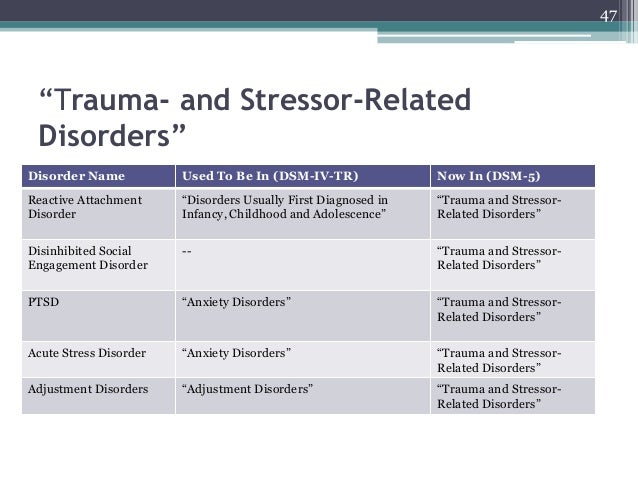

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition (DSM-5) classifies reactive attachment disorder as a trauma- and stressor-related condition of early childhood caused by social neglect and maltreatment. Affected children have difficulty forming emotional attachments to others, show a decreased ability to experience positive emotion, cannot seek or accept physical or emotional closeness, and may react violently when held, cuddled, or comforted. Behaviorally, affected children are unpredictable, difficult to console, and difficult to discipline. Moods fluctuate erratically, and children may seem to live in a fight, flight, or freeze mode. Most have a strong desire to control their environment and make their own decisions. This activity describes the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of reactive attachment disorder and stresses the role of team-based interprofessional care for affected patients.

Objectives:

Review the presentation of reactive attachment disorder.

Describe the evaluation of reactive attachment disorder.

Outline management strategies for reactive attachment disorder.

Explain how the interprofessional team can work collaboratively to prevent the potentially profound complications of reactive attachment disorder by applying knowledge regarding its presentation, evaluation, and management.

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Introduction

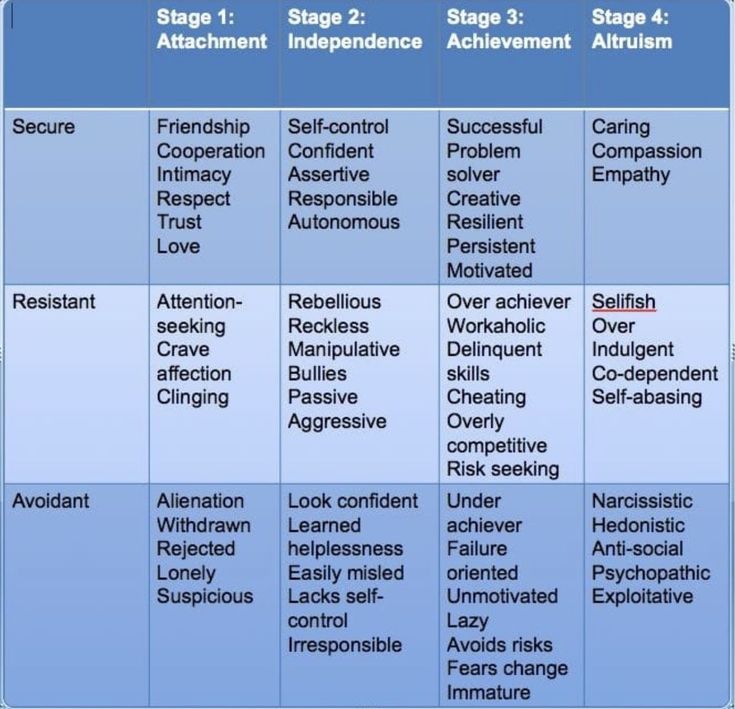

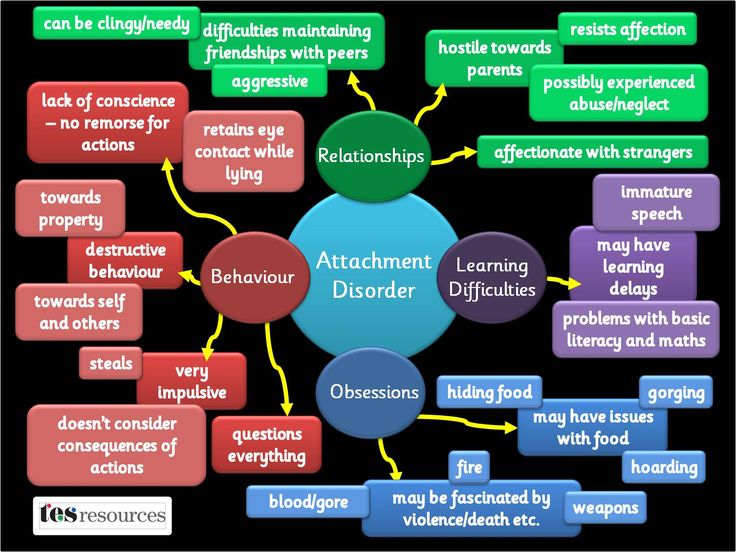

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition (DSM-5) classifies reactive attachment disorder as a trauma- and stressor-related condition of early childhood caused by social neglect or maltreatment. Affected children have difficulty forming emotional attachments to others, show a decreased ability to experience positive emotion, cannot seek or accept physical or emotional closeness, and may react violently when held, cuddled, or comforted. Behaviorally, affected children are unpredictable, difficult to console, and difficult to discipline. Moods fluctuate erratically, and children may seem to live in a “flight, fight, or freeze” mode. Most have a strong desire to control their environment and make their own decisions. Spontaneous changes in the child's routine, attempts to discipline the child, or even unsolicited invitations of comfort may elicit rage, violence, or self-injurious behavior. In the classroom, these challenges inhibit the acquisition of core academic skills and lead to rejection from teachers and peers alike. As they approach adolescence and adulthood, socially neglected children are more likely than their neuro-typical peers to engage in high-risk sexual behavior, substance abuse, involvement with the legal system, and experience incarceration.[1][2][3]

Behaviorally, affected children are unpredictable, difficult to console, and difficult to discipline. Moods fluctuate erratically, and children may seem to live in a “flight, fight, or freeze” mode. Most have a strong desire to control their environment and make their own decisions. Spontaneous changes in the child's routine, attempts to discipline the child, or even unsolicited invitations of comfort may elicit rage, violence, or self-injurious behavior. In the classroom, these challenges inhibit the acquisition of core academic skills and lead to rejection from teachers and peers alike. As they approach adolescence and adulthood, socially neglected children are more likely than their neuro-typical peers to engage in high-risk sexual behavior, substance abuse, involvement with the legal system, and experience incarceration.[1][2][3]

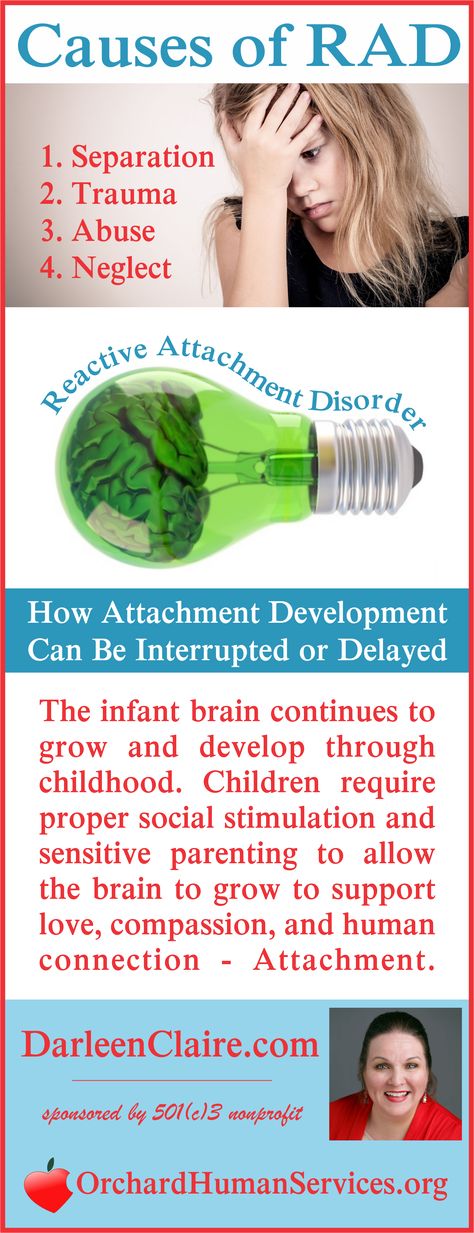

Etiology

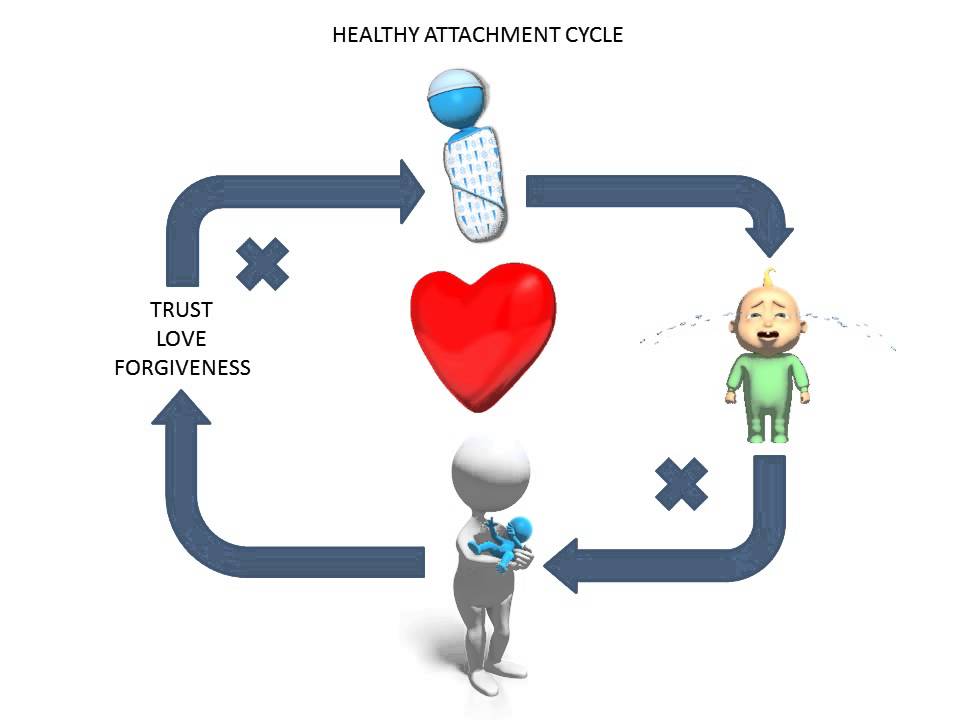

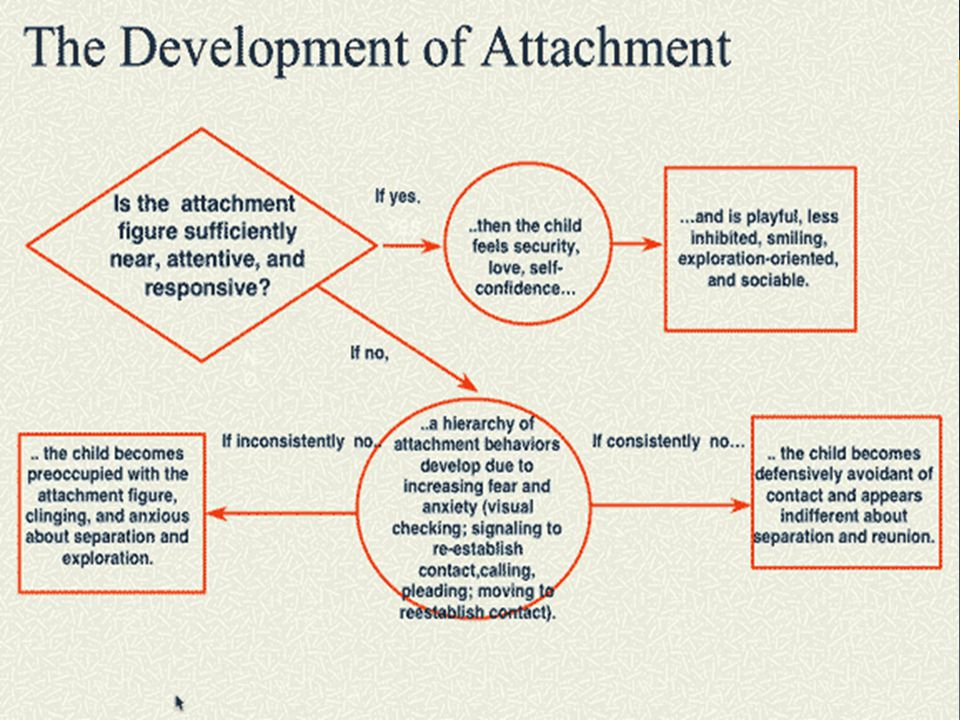

The genesis of reactive attachment disorder is encompassed under the designation of traumatic experience; specifically, the severe emotional neglect commonly found in institutional settings, such as overcrowded orphanages, foster care, or in homes with mentally or physically ill parents. Over time, infants who do not develop a predictable, nurturing bond with a trusted caregiver, do not receive adequate emotional interaction and mental stimulation halt their attempts to engage others and turn inward, ceasing to seek comfort when hurt, avoiding physical and emotional closeness, and eventually become emotionally bereft.[4][3] The absence of adequate nurturing results in poor language acquisition, impaired cognitive development, and contributes to behavioral dysfunction.[5]

Over time, infants who do not develop a predictable, nurturing bond with a trusted caregiver, do not receive adequate emotional interaction and mental stimulation halt their attempts to engage others and turn inward, ceasing to seek comfort when hurt, avoiding physical and emotional closeness, and eventually become emotionally bereft.[4][3] The absence of adequate nurturing results in poor language acquisition, impaired cognitive development, and contributes to behavioral dysfunction.[5]

Epidemiology

Although difficult to accurately assess, recent data suggest a prevalence rate between 1-2%.[6] A data analysis report published by the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) indicated that 42% of children removed from their home and placed in an alternate setting met DSM–IV (1994) criteria for a behavioral health disorder. Additional research completed by Landsverk and Garland and cited in Mental Health Treatment of Child Abuse and Neglect: The Promise of Evidence-Based Practice (Shipman, Kimberly, and Taussig, Heather 2009) found that "between one-half and two-thirds of children entering foster care exhibit behavior or social competency problems warranting mental health services. "

"

Research suggests that concordance rates among siblings raised in the same home to be between 67% and 75%.[7] Neither gender nor ethnicity alone appears to be risk factors for developing the disorder; however, African American and multi-racial children experience higher rates of child maltreatment than do their non-minority counterparts which likely translates to a higher incidence of reactive attachment disorder in minority populations.

The National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being, No. 18 (Instability and Early Life Changes Among Children in the Child Welfare System) shows that 79% of children who died because of abuse or neglect in 2010 were younger than the age of 4. During that same year, 48% of children entering the foster care system were also younger than age 5.[7]

Pathophysiology

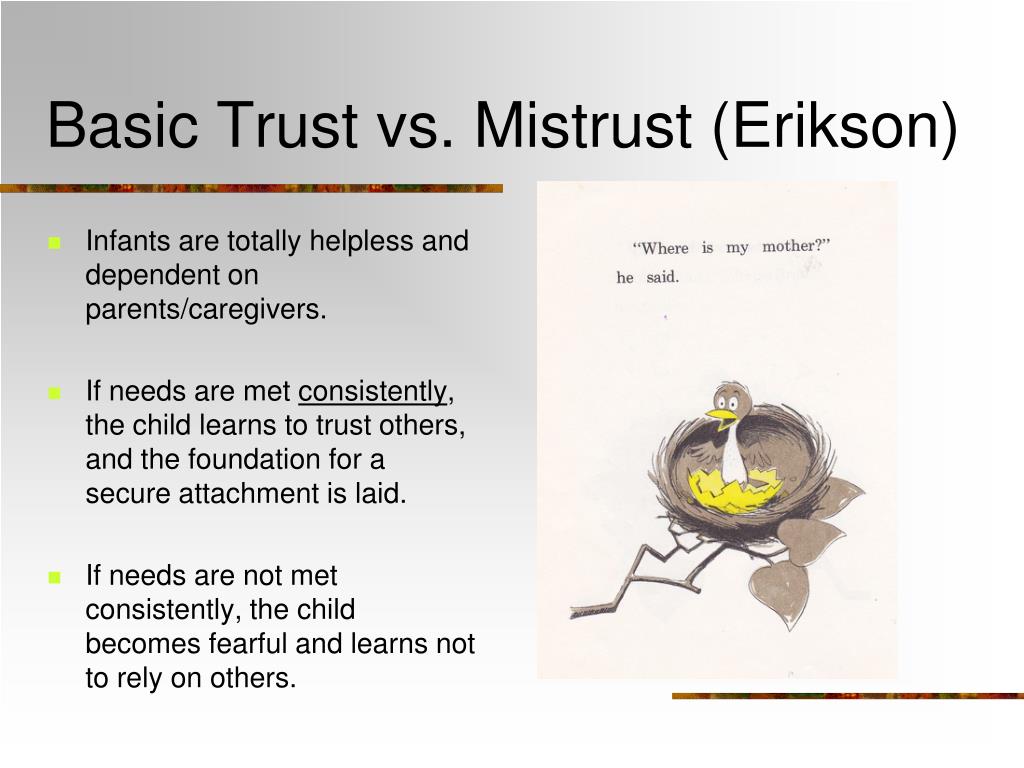

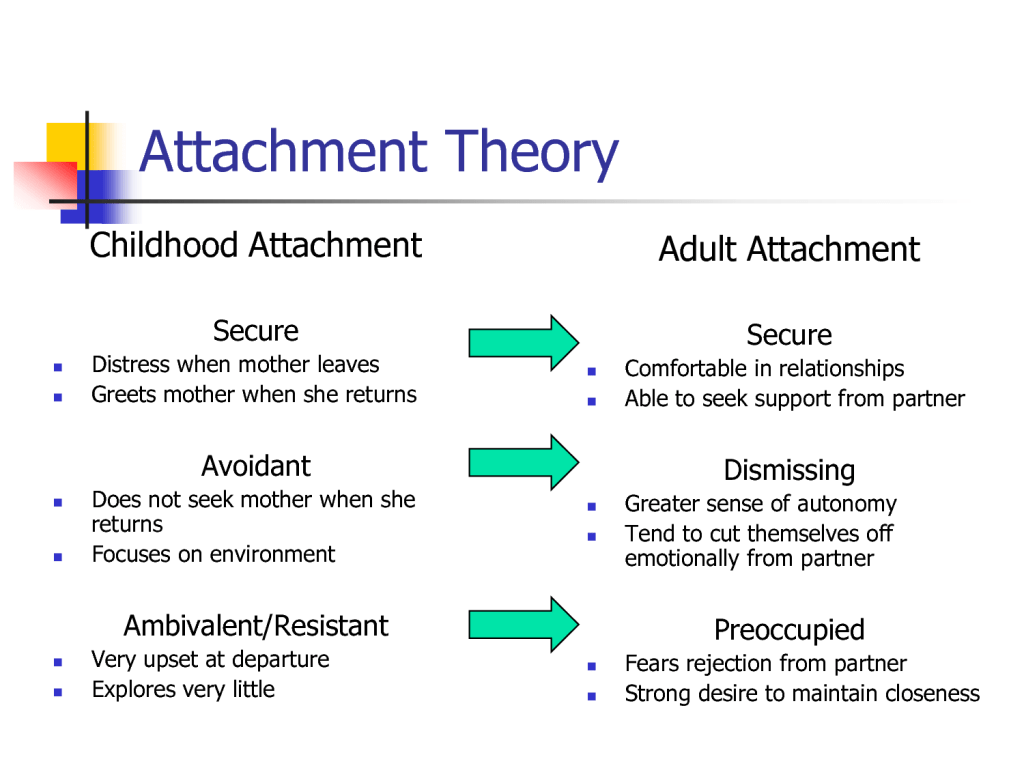

Since WWII, physicians, psychologists, and attachment theorists have documented the impact of social neglect on physical and emotional development. Experiments completed in the 1940s and 1950s found that maternal deprivation had a profound effect on infant growth, motor development, social interaction, and behavior. In the film Psychogenic Diseases in Infancy (Spitz, 1952), infants deviated from the normal, expected course of development and became “unapproachable, weepy and screaming” within the first 2 months of maternal deprivation. As the deprivation continued, facial expressions became rigid and then flat; motor development regressed, and by the fifth month, infants were “lethargic,” unable to “sit, stand, walk, or talk,” suffered from growth abnormalities, developed “atypical, bizarre finger movements,” and no longer sought or responded to social interaction; 37.3% of the infants died within 2 years. These early experiments became the foundation for Attachment Theory and outlined the constellation of symptoms of what the DSM, Third Edition (DSM–III) would later call reactive attachment disorder.

In the film Psychogenic Diseases in Infancy (Spitz, 1952), infants deviated from the normal, expected course of development and became “unapproachable, weepy and screaming” within the first 2 months of maternal deprivation. As the deprivation continued, facial expressions became rigid and then flat; motor development regressed, and by the fifth month, infants were “lethargic,” unable to “sit, stand, walk, or talk,” suffered from growth abnormalities, developed “atypical, bizarre finger movements,” and no longer sought or responded to social interaction; 37.3% of the infants died within 2 years. These early experiments became the foundation for Attachment Theory and outlined the constellation of symptoms of what the DSM, Third Edition (DSM–III) would later call reactive attachment disorder.

History and Physical

The DSM-5 gives the following criteria for reactive attachment disorder:

The patient demonstrates a chronic pattern of being emotionally withdrawn and inhibited, which is demonstrated by rarely seeking or responsive to comfort when distressed.

There is evidence of a chronic social and/or emotional perturbation characterized by at least two of the proceeding: social withdrawal and minimal responsiveness to others, negative affect, unfounded or inexplicable episodes of irritability, fearfulness, or sadness--or out of proportion reactions to normative stress.

The patient presents with a history of extremely insufficient care, entailing of one of the following: deprivation or social neglect of basic emotional needs for stimulation, comfort, and affection by caring caregivers; the constant flux of caregivers, resulting in a destabilized home environment; growing up in an unusual setting which limits the ability to form selective attachments

The child cannot also meet the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder as the two diagnoses (autism spectrum disorder and reactive attachment disorder) are mutually exclusive

The behavioral perturbation should manifest prior to the age of 5 years of age

The child must have a developmental age of at least nine months in order to qualify for the diagnosis

These diagnostic criteria provide an outline of symptoms; however, providers must also recognize the global impact on cognition, behavior, and affective functioning.

Cognition

Abuse in childhood has been correlated with difficulties in working memory and executive functioning, while severe neglect is associated with underdevelopment of the left cerebral hemisphere and the hippocampus.[8][3]

Behavioral

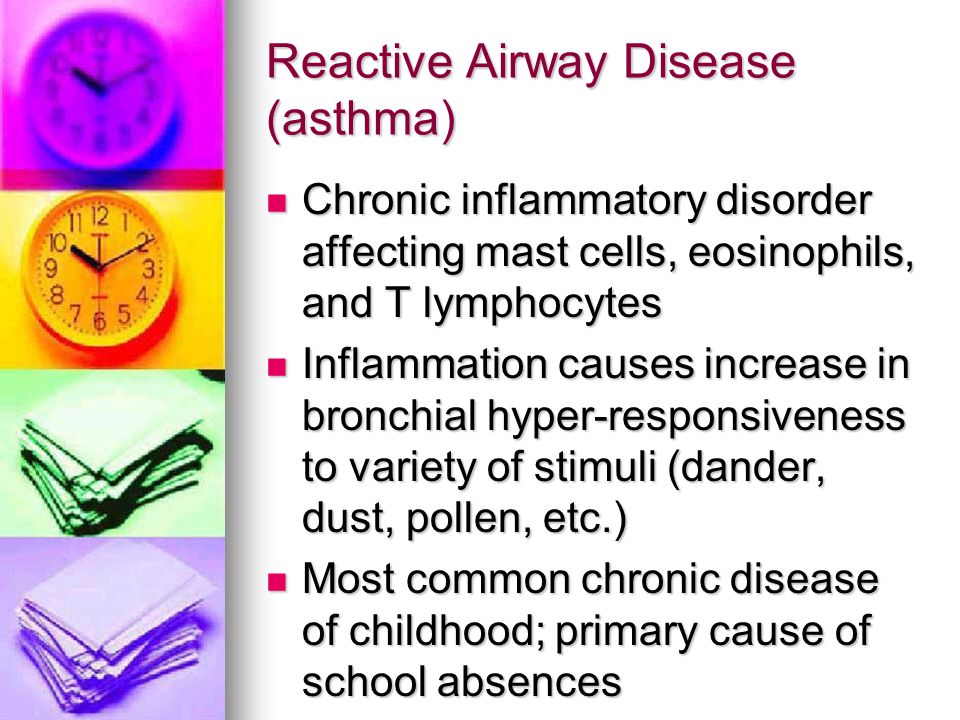

Social skills are below what would be expected of either their chronological age or developmental level. Children with RAD may respond to ordinary interactions with aggression, fear, defiance, or rage. Affected children are more likely to face rejection by adults and peers, develop a negative self-schema, and experience somatic symptoms of distress. Psychomotor restlessness is common, as is hyperactivity and stereotypic movements, such as hand flapping or rocking.[1][4]

Affective

RAD increases the risk of anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, and reduces frustration tolerance. Ailing children are likely to be highly reactive, even in non-threatening situations.[8]

Evaluation

Clinicians should have a low threshold for referring children with a known history of adoption, abuse, foster, or institutional care to a child psychologist or psychiatrist for a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment detailing the child’s history, description of the symptoms over time, and direct observation of the parent-child interaction. Attachment behaviors and signs of secure attachment (e.g., comfort-seeking, good eye contact, child-initiated interaction) should be assessed at every visit. Clinicians should maintain a low threshold for referral to a child development specialist, a child psychiatrist, or a child psychologist.[9]

Attachment behaviors and signs of secure attachment (e.g., comfort-seeking, good eye contact, child-initiated interaction) should be assessed at every visit. Clinicians should maintain a low threshold for referral to a child development specialist, a child psychiatrist, or a child psychologist.[9]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of RAD requires a multi-pronged approach incorporating parent education and trauma-focused therapy. Parent education focused on developing positive, non-punitive behavior management strategies, ways of responding to nonverbal communication, anticipation and coping strategies for when triggers arise and parent-child psychotherapy can facilitate bonding and healthy attachment. Empathy and compassion are key elements to building trust. Developing a nurturing parent-child relationship is the cornerstone to overcoming the damage caused by severe neglect and abuse.

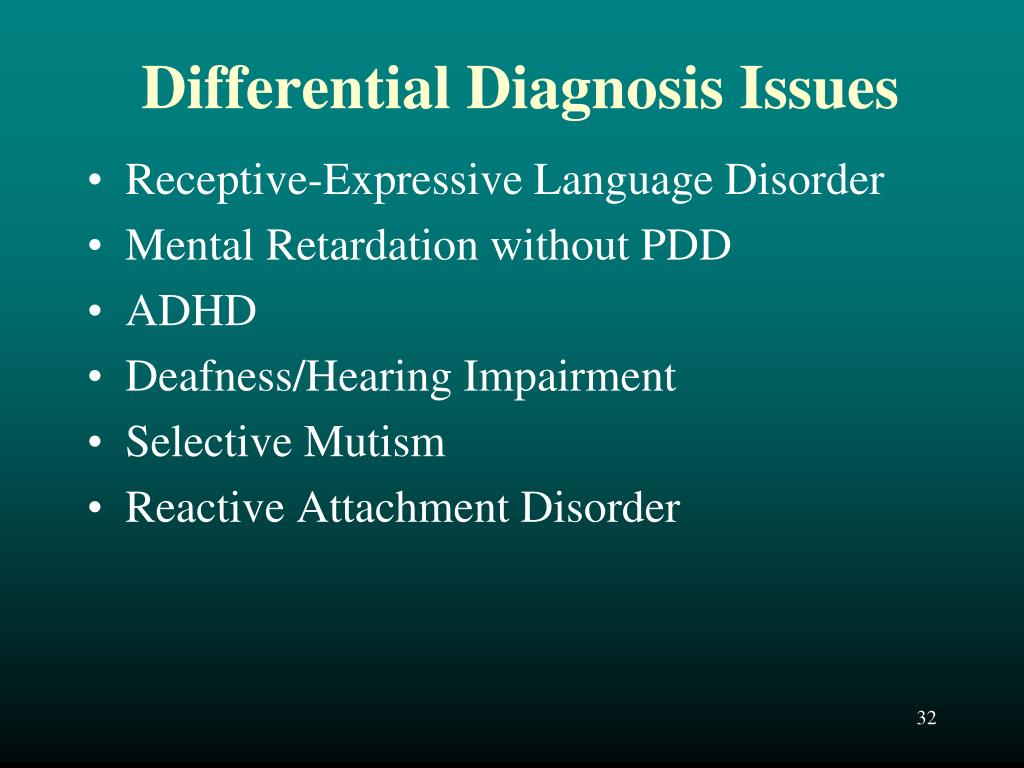

Differential Diagnosis

According to the DSM-5, the following differential diagnoses should be ruled out before a diagnosis of reactive attachment disorder:

Autism Spectrum Disorders

Children on the autism spectrum often exhibit many of the same features as those with reactive attachment disorder; however, restricted range of interest, sensory processing difficulties, and rigid adherence to rituals or routines are specific to autism spectrum disorder.

Intellectual Impairment

For a diagnosis of RAD to be made, the child must have attained a developmental age of at least 9 months, and another medical or mental health disorder must not cause social impairments. Impairments in social relatedness commensurate with developmental age should be viewed as an overall feature of the developmental delay and not solely a response to severe neglect.

Depressive Disorders

Symptoms of anhedonia may mirror many of the withdrawal symptoms of RAD; however, children suffering from depression maintain the ability to attach and to seek and receive comfort from preferred caregivers.

Prognosis

Even with intervention, injured children encounter difficulties in every aspect of their lives; from classroom learning to developing a secure sense of self. The traumatic situations which lead to the attachment disorder create a persistent state of stress; diminishing their capacity for resilience. Early identification and treatment have been shown to improve outcomes; however, parent education and support are key. Parents adopting children from state custody or from overseas orphanages should receive education on the impact of social deprivation and connected with service agencies or providers specializing in attachment disorders.[9]

Parents adopting children from state custody or from overseas orphanages should receive education on the impact of social deprivation and connected with service agencies or providers specializing in attachment disorders.[9]

Complications

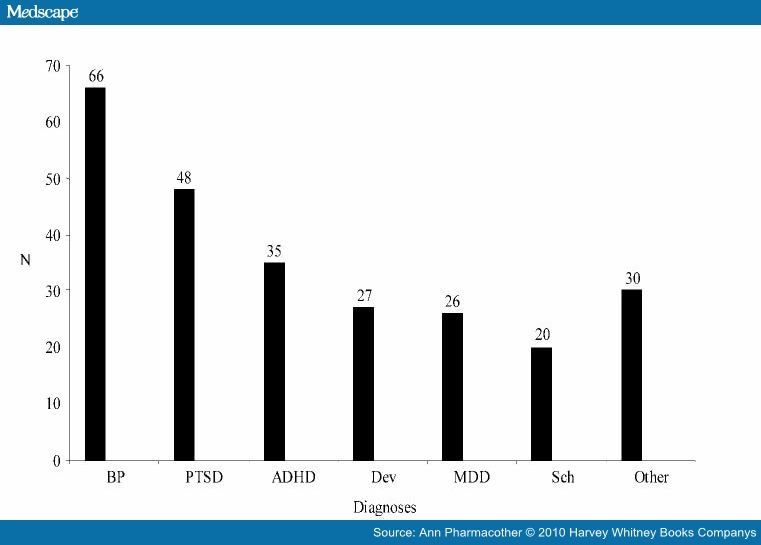

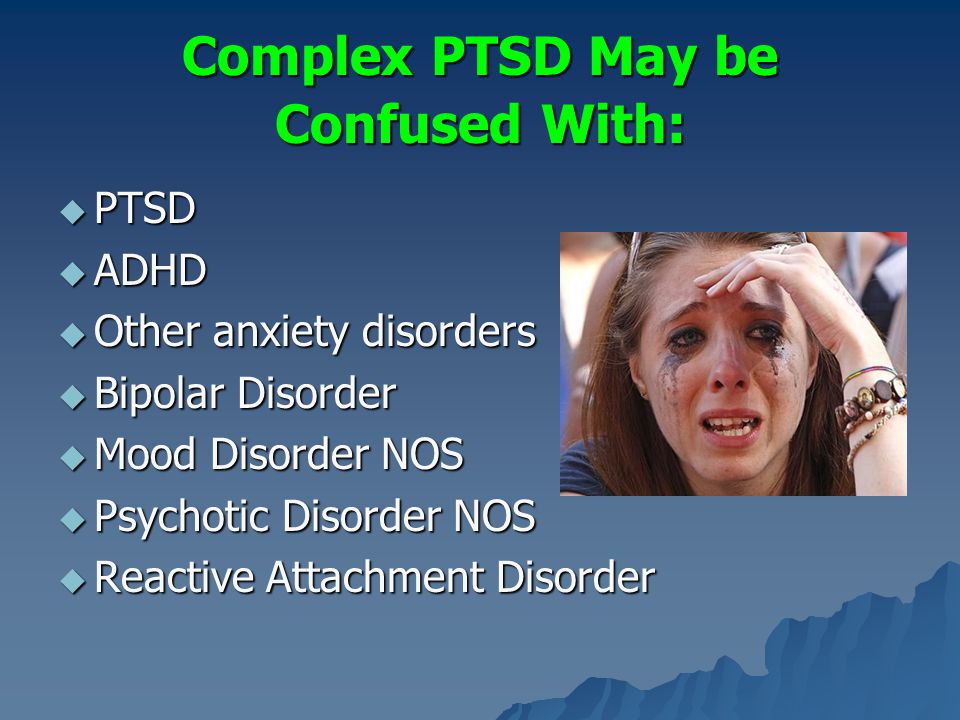

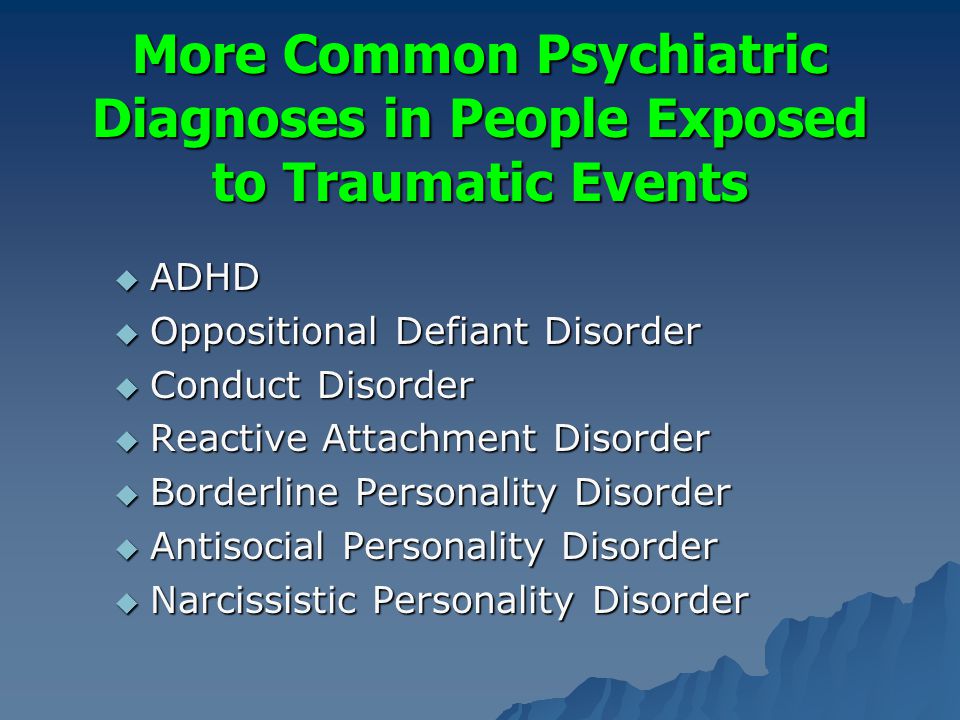

Signs and symptoms of RAD may be missed by providers who are unfamiliar with the child’s history or when the history is unknown. Symptoms may be attributed to common behavioral health disorders such as depression, anxiety, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, genetic or neurological disorders, or autism spectrum disorder. Although there is a significant symptom overlap and co-occurrence, treatment for each varies and some treatment methods may exacerbate RAD.

Consultations

Consultation and evaluation by a developmental pediatrician, a child psychiatrist, or a child psychologist should be completed before assigning the diagnosis of reactive attachment disorder. Neuropsychological assessments or other psychometric evaluations are useful in identifying discrepancies between chronological age and age-approximate functioning across multiple domains.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Much research has been done on the effects of severe social isolation and neglect on children removed from abusive homes or raised in institutions; however, there is still much work to be done to determine the impact of inadequate caregiving in the home. Psychosocial stressors such as poverty, lack of suitable childcare, parental substance abuse, incarceration, or severe mental illness increase the risk of all forms of abuse, particularly neglect. Parents facing extreme psychosocial stressors may find themselves unable to provide more than very necessities and may lack the healthcare literacy to understand the importance of their infant’s emotional development. Clinicians working with parents and children should be cognizant of the psychosocial factors which may impede a parents’ ability to provide consistent emotional feedback and intervene or refer for additional support when indicated. Healthcare providers should assess for maternal depression and evaluate parent-child interactions during routine appointments. [3]

[3]

Pearls and Other Issues

Before 2013, the diagnosis of reactive attachment disorder incorporated inhibited and dis-inhibited subtypes; however; the advent of the DSM-5 heralded the separation of each subtype into separate and distinct diagnoses. DSED represents a second clinical course for children exposed to neglect and abuse. While the clinical picture of RAD is of emotionally withdrawn, unemotional, or even callous children; disinhibited social engagement disorder presents with indiscriminate, overly friendly behavior. Typical fear behaviors such as crying, turning away, or seeking comfort from a preferred adult are absent and are instead replaced with a lack of age-appropriate restraint with acquaintances or strangers. The disinhibited nature of the disorder results in children seeking comfort or care indiscriminately, giving and receiving affection, and seeking attention from any available adult without regard for their safety.[9]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

To improve outcomes and provide clinically sound treatment, those tasked with assessing and evaluating children with RAD must be acquainted with the underpinnings of attachment theory, understand the profound impact of maltreatment on behavior, cognition, and communication. Assessment of social interaction and developmental milestones should be completed following Centers for Disease Control (CDC) or World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines to ensure delays in meeting expected milestones are addressed as early as possible. Developmental pediatricians, child psychologists, or child psychiatrists can complete comprehensive assessments to narrow the differential diagnosis. Caring for children with RAD requires an interprofessional "wrap around" approach incorporating behavioral health providers to address behavioral challenges, social workers and case managers to assist with resources and referral, speech and language pathologists to address social communication deficits, and rehabilitative services to address motor skill delays caused by severe neglect or abuse. Working together, school personnel and parents can develop an Individualized Education Plan which creates a safe, nurturing environment where affected students can rise to their full potential.

Assessment of social interaction and developmental milestones should be completed following Centers for Disease Control (CDC) or World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines to ensure delays in meeting expected milestones are addressed as early as possible. Developmental pediatricians, child psychologists, or child psychiatrists can complete comprehensive assessments to narrow the differential diagnosis. Caring for children with RAD requires an interprofessional "wrap around" approach incorporating behavioral health providers to address behavioral challenges, social workers and case managers to assist with resources and referral, speech and language pathologists to address social communication deficits, and rehabilitative services to address motor skill delays caused by severe neglect or abuse. Working together, school personnel and parents can develop an Individualized Education Plan which creates a safe, nurturing environment where affected students can rise to their full potential.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry developed clinical standards (CS), clinical guidelines (CG), clinical options (OP), or not endorsed (NE). The following guide assessment and treatment of children with reactive attachment disorder.[9]

The following guide assessment and treatment of children with reactive attachment disorder.[9]

Recommendation 1. "For young children with a history of foster care, adoption, or institutional rearing, clinicians should inquire routinely about a) whether the child demonstrates attachment behaviors and b) whether the child is reticent with strangers." (CS)

Recommendation 2. The Clinician conducting a diagnostic assessment of RAD and DSED should obtain direct evidence from both a history of the child's patterns of attachment behavior with his or her primary caregivers and observations of the child interacting with these caregivers. (CS)

Recommendation 3. The clinician may be aided in making the diagnosis of RAD or DSED by a structured observational paradigm that compares the child's behavior with familiar and unfamiliar adults. (OP)

Recommendation 4. Clinicians should perform a comprehensive psychiatric assessment of children with RAD or DSED to determine the presence of comorbid disorders (CS)

Recommendation 5. The Clinician should assess the safety of the current placement for previously maltreated children with negative behaviors who are at high risk of being re-traumatized. (CS)

The Clinician should assess the safety of the current placement for previously maltreated children with negative behaviors who are at high risk of being re-traumatized. (CS)

Recommendation 6. The most important intervention for young children diagnosed with RAD or DSED is ensuring that they are provided with an emotionally available attachment figure. (CS)

Recommendation 7. For young children diagnosed with DSED, limiting contacts with non-caregiving adults may reduce signs of the disorder. (OP)

Recommendation 8. Clinicians should recommend adjunctive interventions for children who display aggressive and/or oppositional behavior that is comorbid with DSED. (CS)

Recommendation 9. Psychopharmacological interventions are not indicated for the core features or RAD or DSED. (NE)

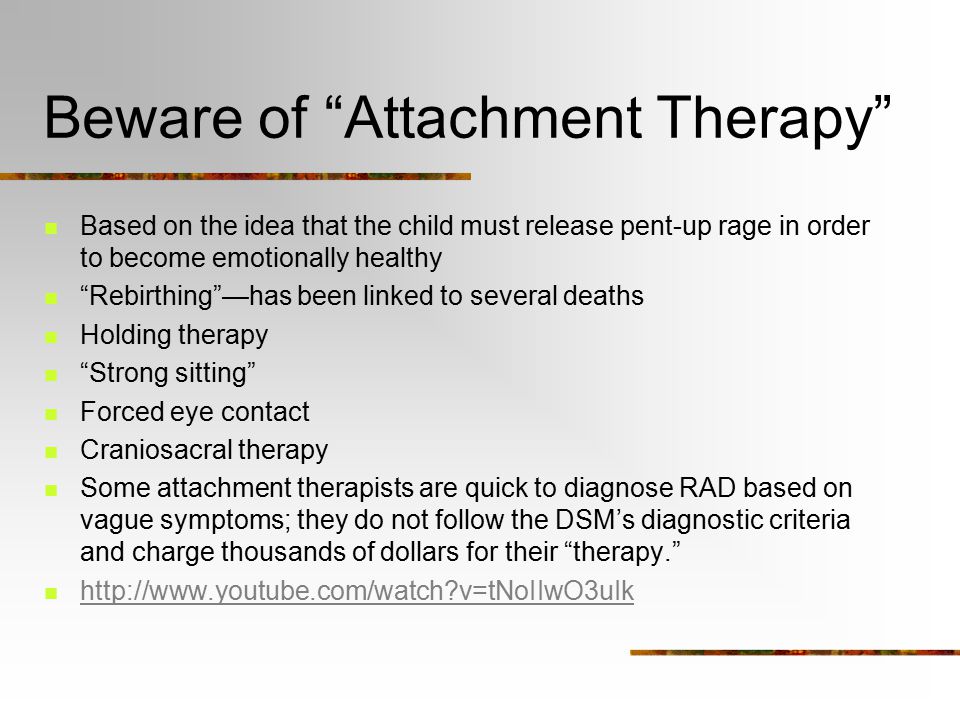

Recommendation 10. Clinicians should not administer interventions designed to enhance attachment that involves noncontingent physical restraint or coercion (e.g., "therapeutic holding" or "compression holding"), ''reworking'' of trauma (e. g., "rebirthing therapy), or promotion of regression for "reattachment'' because they have no empirical support and have been associated with serious harm, including death. (NE)[9]

g., "rebirthing therapy), or promotion of regression for "reattachment'' because they have no empirical support and have been associated with serious harm, including death. (NE)[9]

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

References

- 1.

Milot T, Ethier LS, St-Laurent D, Provost MA. The role of trauma symptoms in the development of behavioral problems in maltreated preschoolers. Child Abuse Negl. 2010 Apr;34(4):225-34. [PubMed: 20303174]

- 2.

Moran K, McDonald J, Jackson A, Turnbull S, Minnis H. A study of Attachment Disorders in young offenders attending specialist services. Child Abuse Negl. 2017 Mar;65:77-87. [PubMed: 28126657]

- 3.

Winston R, Chicot R. The importance of early bonding on the long-term mental health and resilience of children. London J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2016;8(1):12-14. [PMC free article: PMC5330336] [PubMed: 28250823]

- 4.

Lionetti F, Pastore M, Barone L. Attachment in institutionalized children: a review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2015 Apr;42:135-45. [PubMed: 25747874]

- 5.

Spratt EG, Friedenberg SL, Swenson CC, Larosa A, De Bellis MD, Macias MM, Summer AP, Hulsey TC, Runyan DK, Brady KT. The Effects of Early Neglect on Cognitive, Language, and Behavioral Functioning in Childhood. Psychology (Irvine). 2012 Feb 01;3(2):175-182. [PMC free article: PMC3652241] [PubMed: 23678396]

- 6.

Pritchett R, Pritchett J, Marshall E, Davidson C, Minnis H. Reactive attachment disorder in the general population: a hidden ESSENCE disorder. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:818157. [PMC free article: PMC3654285] [PubMed: 23710150]

- 7.

Shipman K, Taussig H. Mental health treatment of child abuse and neglect: the promise of evidence-based practice. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009 Apr;56(2):417-28. [PubMed: 19358925]

- 8.

Braun K, Bock J.

The experience-dependent maturation of prefronto-limbic circuits and the origin of developmental psychopathology: implications for the pathogenesis and therapy of behavioural disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011 Sep;53 Suppl 4:14-8. [PubMed: 21950388]

The experience-dependent maturation of prefronto-limbic circuits and the origin of developmental psychopathology: implications for the pathogenesis and therapy of behavioural disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011 Sep;53 Suppl 4:14-8. [PubMed: 21950388]- 9.

Zeanah CH, Chesher T, Boris NW., American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI). Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Nov;55(11):990-1003. [PubMed: 27806867]

Reactive Attachment Disorder - StatPearls

Continuing Education Activity

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition (DSM-5) classifies reactive attachment disorder as a trauma- and stressor-related condition of early childhood caused by social neglect and maltreatment. Affected children have difficulty forming emotional attachments to others, show a decreased ability to experience positive emotion, cannot seek or accept physical or emotional closeness, and may react violently when held, cuddled, or comforted. Behaviorally, affected children are unpredictable, difficult to console, and difficult to discipline. Moods fluctuate erratically, and children may seem to live in a fight, flight, or freeze mode. Most have a strong desire to control their environment and make their own decisions. This activity describes the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of reactive attachment disorder and stresses the role of team-based interprofessional care for affected patients.

Behaviorally, affected children are unpredictable, difficult to console, and difficult to discipline. Moods fluctuate erratically, and children may seem to live in a fight, flight, or freeze mode. Most have a strong desire to control their environment and make their own decisions. This activity describes the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of reactive attachment disorder and stresses the role of team-based interprofessional care for affected patients.

Objectives:

Review the presentation of reactive attachment disorder.

Describe the evaluation of reactive attachment disorder.

Outline management strategies for reactive attachment disorder.

Explain how the interprofessional team can work collaboratively to prevent the potentially profound complications of reactive attachment disorder by applying knowledge regarding its presentation, evaluation, and management.

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Introduction

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition (DSM-5) classifies reactive attachment disorder as a trauma- and stressor-related condition of early childhood caused by social neglect or maltreatment. Affected children have difficulty forming emotional attachments to others, show a decreased ability to experience positive emotion, cannot seek or accept physical or emotional closeness, and may react violently when held, cuddled, or comforted. Behaviorally, affected children are unpredictable, difficult to console, and difficult to discipline. Moods fluctuate erratically, and children may seem to live in a “flight, fight, or freeze” mode. Most have a strong desire to control their environment and make their own decisions. Spontaneous changes in the child's routine, attempts to discipline the child, or even unsolicited invitations of comfort may elicit rage, violence, or self-injurious behavior. In the classroom, these challenges inhibit the acquisition of core academic skills and lead to rejection from teachers and peers alike. As they approach adolescence and adulthood, socially neglected children are more likely than their neuro-typical peers to engage in high-risk sexual behavior, substance abuse, involvement with the legal system, and experience incarceration.[1][2][3]

As they approach adolescence and adulthood, socially neglected children are more likely than their neuro-typical peers to engage in high-risk sexual behavior, substance abuse, involvement with the legal system, and experience incarceration.[1][2][3]

Etiology

The genesis of reactive attachment disorder is encompassed under the designation of traumatic experience; specifically, the severe emotional neglect commonly found in institutional settings, such as overcrowded orphanages, foster care, or in homes with mentally or physically ill parents. Over time, infants who do not develop a predictable, nurturing bond with a trusted caregiver, do not receive adequate emotional interaction and mental stimulation halt their attempts to engage others and turn inward, ceasing to seek comfort when hurt, avoiding physical and emotional closeness, and eventually become emotionally bereft.[4][3] The absence of adequate nurturing results in poor language acquisition, impaired cognitive development, and contributes to behavioral dysfunction. [5]

[5]

Epidemiology

Although difficult to accurately assess, recent data suggest a prevalence rate between 1-2%.[6] A data analysis report published by the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) indicated that 42% of children removed from their home and placed in an alternate setting met DSM–IV (1994) criteria for a behavioral health disorder. Additional research completed by Landsverk and Garland and cited in Mental Health Treatment of Child Abuse and Neglect: The Promise of Evidence-Based Practice (Shipman, Kimberly, and Taussig, Heather 2009) found that "between one-half and two-thirds of children entering foster care exhibit behavior or social competency problems warranting mental health services."

Research suggests that concordance rates among siblings raised in the same home to be between 67% and 75%.[7] Neither gender nor ethnicity alone appears to be risk factors for developing the disorder; however, African American and multi-racial children experience higher rates of child maltreatment than do their non-minority counterparts which likely translates to a higher incidence of reactive attachment disorder in minority populations.

The National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being, No. 18 (Instability and Early Life Changes Among Children in the Child Welfare System) shows that 79% of children who died because of abuse or neglect in 2010 were younger than the age of 4. During that same year, 48% of children entering the foster care system were also younger than age 5.[7]

Pathophysiology

Since WWII, physicians, psychologists, and attachment theorists have documented the impact of social neglect on physical and emotional development. Experiments completed in the 1940s and 1950s found that maternal deprivation had a profound effect on infant growth, motor development, social interaction, and behavior. In the film Psychogenic Diseases in Infancy (Spitz, 1952), infants deviated from the normal, expected course of development and became “unapproachable, weepy and screaming” within the first 2 months of maternal deprivation. As the deprivation continued, facial expressions became rigid and then flat; motor development regressed, and by the fifth month, infants were “lethargic,” unable to “sit, stand, walk, or talk,” suffered from growth abnormalities, developed “atypical, bizarre finger movements,” and no longer sought or responded to social interaction; 37. 3% of the infants died within 2 years. These early experiments became the foundation for Attachment Theory and outlined the constellation of symptoms of what the DSM, Third Edition (DSM–III) would later call reactive attachment disorder.

History and Physical

The DSM-5 gives the following criteria for reactive attachment disorder:

The patient demonstrates a chronic pattern of being emotionally withdrawn and inhibited, which is demonstrated by rarely seeking or responsive to comfort when distressed.

There is evidence of a chronic social and/or emotional perturbation characterized by at least two of the proceeding: social withdrawal and minimal responsiveness to others, negative affect, unfounded or inexplicable episodes of irritability, fearfulness, or sadness--or out of proportion reactions to normative stress.

The patient presents with a history of extremely insufficient care, entailing of one of the following: deprivation or social neglect of basic emotional needs for stimulation, comfort, and affection by caring caregivers; the constant flux of caregivers, resulting in a destabilized home environment; growing up in an unusual setting which limits the ability to form selective attachments

The child cannot also meet the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder as the two diagnoses (autism spectrum disorder and reactive attachment disorder) are mutually exclusive

The behavioral perturbation should manifest prior to the age of 5 years of age

The child must have a developmental age of at least nine months in order to qualify for the diagnosis

These diagnostic criteria provide an outline of symptoms; however, providers must also recognize the global impact on cognition, behavior, and affective functioning.

Cognition

Abuse in childhood has been correlated with difficulties in working memory and executive functioning, while severe neglect is associated with underdevelopment of the left cerebral hemisphere and the hippocampus.[8][3]

Behavioral

Social skills are below what would be expected of either their chronological age or developmental level. Children with RAD may respond to ordinary interactions with aggression, fear, defiance, or rage. Affected children are more likely to face rejection by adults and peers, develop a negative self-schema, and experience somatic symptoms of distress. Psychomotor restlessness is common, as is hyperactivity and stereotypic movements, such as hand flapping or rocking.[1][4]

Affective

RAD increases the risk of anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, and reduces frustration tolerance. Ailing children are likely to be highly reactive, even in non-threatening situations.[8]

Evaluation

Clinicians should have a low threshold for referring children with a known history of adoption, abuse, foster, or institutional care to a child psychologist or psychiatrist for a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment detailing the child’s history, description of the symptoms over time, and direct observation of the parent-child interaction. Attachment behaviors and signs of secure attachment (e.g., comfort-seeking, good eye contact, child-initiated interaction) should be assessed at every visit. Clinicians should maintain a low threshold for referral to a child development specialist, a child psychiatrist, or a child psychologist.[9]

Attachment behaviors and signs of secure attachment (e.g., comfort-seeking, good eye contact, child-initiated interaction) should be assessed at every visit. Clinicians should maintain a low threshold for referral to a child development specialist, a child psychiatrist, or a child psychologist.[9]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of RAD requires a multi-pronged approach incorporating parent education and trauma-focused therapy. Parent education focused on developing positive, non-punitive behavior management strategies, ways of responding to nonverbal communication, anticipation and coping strategies for when triggers arise and parent-child psychotherapy can facilitate bonding and healthy attachment. Empathy and compassion are key elements to building trust. Developing a nurturing parent-child relationship is the cornerstone to overcoming the damage caused by severe neglect and abuse.

Differential Diagnosis

According to the DSM-5, the following differential diagnoses should be ruled out before a diagnosis of reactive attachment disorder:

Autism Spectrum Disorders

Children on the autism spectrum often exhibit many of the same features as those with reactive attachment disorder; however, restricted range of interest, sensory processing difficulties, and rigid adherence to rituals or routines are specific to autism spectrum disorder.

Intellectual Impairment

For a diagnosis of RAD to be made, the child must have attained a developmental age of at least 9 months, and another medical or mental health disorder must not cause social impairments. Impairments in social relatedness commensurate with developmental age should be viewed as an overall feature of the developmental delay and not solely a response to severe neglect.

Depressive Disorders

Symptoms of anhedonia may mirror many of the withdrawal symptoms of RAD; however, children suffering from depression maintain the ability to attach and to seek and receive comfort from preferred caregivers.

Prognosis

Even with intervention, injured children encounter difficulties in every aspect of their lives; from classroom learning to developing a secure sense of self. The traumatic situations which lead to the attachment disorder create a persistent state of stress; diminishing their capacity for resilience. Early identification and treatment have been shown to improve outcomes; however, parent education and support are key. Parents adopting children from state custody or from overseas orphanages should receive education on the impact of social deprivation and connected with service agencies or providers specializing in attachment disorders.[9]

Parents adopting children from state custody or from overseas orphanages should receive education on the impact of social deprivation and connected with service agencies or providers specializing in attachment disorders.[9]

Complications

Signs and symptoms of RAD may be missed by providers who are unfamiliar with the child’s history or when the history is unknown. Symptoms may be attributed to common behavioral health disorders such as depression, anxiety, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, genetic or neurological disorders, or autism spectrum disorder. Although there is a significant symptom overlap and co-occurrence, treatment for each varies and some treatment methods may exacerbate RAD.

Consultations

Consultation and evaluation by a developmental pediatrician, a child psychiatrist, or a child psychologist should be completed before assigning the diagnosis of reactive attachment disorder. Neuropsychological assessments or other psychometric evaluations are useful in identifying discrepancies between chronological age and age-approximate functioning across multiple domains.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Much research has been done on the effects of severe social isolation and neglect on children removed from abusive homes or raised in institutions; however, there is still much work to be done to determine the impact of inadequate caregiving in the home. Psychosocial stressors such as poverty, lack of suitable childcare, parental substance abuse, incarceration, or severe mental illness increase the risk of all forms of abuse, particularly neglect. Parents facing extreme psychosocial stressors may find themselves unable to provide more than very necessities and may lack the healthcare literacy to understand the importance of their infant’s emotional development. Clinicians working with parents and children should be cognizant of the psychosocial factors which may impede a parents’ ability to provide consistent emotional feedback and intervene or refer for additional support when indicated. Healthcare providers should assess for maternal depression and evaluate parent-child interactions during routine appointments. [3]

[3]

Pearls and Other Issues

Before 2013, the diagnosis of reactive attachment disorder incorporated inhibited and dis-inhibited subtypes; however; the advent of the DSM-5 heralded the separation of each subtype into separate and distinct diagnoses. DSED represents a second clinical course for children exposed to neglect and abuse. While the clinical picture of RAD is of emotionally withdrawn, unemotional, or even callous children; disinhibited social engagement disorder presents with indiscriminate, overly friendly behavior. Typical fear behaviors such as crying, turning away, or seeking comfort from a preferred adult are absent and are instead replaced with a lack of age-appropriate restraint with acquaintances or strangers. The disinhibited nature of the disorder results in children seeking comfort or care indiscriminately, giving and receiving affection, and seeking attention from any available adult without regard for their safety.[9]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

To improve outcomes and provide clinically sound treatment, those tasked with assessing and evaluating children with RAD must be acquainted with the underpinnings of attachment theory, understand the profound impact of maltreatment on behavior, cognition, and communication. Assessment of social interaction and developmental milestones should be completed following Centers for Disease Control (CDC) or World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines to ensure delays in meeting expected milestones are addressed as early as possible. Developmental pediatricians, child psychologists, or child psychiatrists can complete comprehensive assessments to narrow the differential diagnosis. Caring for children with RAD requires an interprofessional "wrap around" approach incorporating behavioral health providers to address behavioral challenges, social workers and case managers to assist with resources and referral, speech and language pathologists to address social communication deficits, and rehabilitative services to address motor skill delays caused by severe neglect or abuse. Working together, school personnel and parents can develop an Individualized Education Plan which creates a safe, nurturing environment where affected students can rise to their full potential.

Assessment of social interaction and developmental milestones should be completed following Centers for Disease Control (CDC) or World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines to ensure delays in meeting expected milestones are addressed as early as possible. Developmental pediatricians, child psychologists, or child psychiatrists can complete comprehensive assessments to narrow the differential diagnosis. Caring for children with RAD requires an interprofessional "wrap around" approach incorporating behavioral health providers to address behavioral challenges, social workers and case managers to assist with resources and referral, speech and language pathologists to address social communication deficits, and rehabilitative services to address motor skill delays caused by severe neglect or abuse. Working together, school personnel and parents can develop an Individualized Education Plan which creates a safe, nurturing environment where affected students can rise to their full potential.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry developed clinical standards (CS), clinical guidelines (CG), clinical options (OP), or not endorsed (NE). The following guide assessment and treatment of children with reactive attachment disorder.[9]

The following guide assessment and treatment of children with reactive attachment disorder.[9]

Recommendation 1. "For young children with a history of foster care, adoption, or institutional rearing, clinicians should inquire routinely about a) whether the child demonstrates attachment behaviors and b) whether the child is reticent with strangers." (CS)

Recommendation 2. The Clinician conducting a diagnostic assessment of RAD and DSED should obtain direct evidence from both a history of the child's patterns of attachment behavior with his or her primary caregivers and observations of the child interacting with these caregivers. (CS)

Recommendation 3. The clinician may be aided in making the diagnosis of RAD or DSED by a structured observational paradigm that compares the child's behavior with familiar and unfamiliar adults. (OP)

Recommendation 4. Clinicians should perform a comprehensive psychiatric assessment of children with RAD or DSED to determine the presence of comorbid disorders (CS)

Recommendation 5. The Clinician should assess the safety of the current placement for previously maltreated children with negative behaviors who are at high risk of being re-traumatized. (CS)

The Clinician should assess the safety of the current placement for previously maltreated children with negative behaviors who are at high risk of being re-traumatized. (CS)

Recommendation 6. The most important intervention for young children diagnosed with RAD or DSED is ensuring that they are provided with an emotionally available attachment figure. (CS)

Recommendation 7. For young children diagnosed with DSED, limiting contacts with non-caregiving adults may reduce signs of the disorder. (OP)

Recommendation 8. Clinicians should recommend adjunctive interventions for children who display aggressive and/or oppositional behavior that is comorbid with DSED. (CS)

Recommendation 9. Psychopharmacological interventions are not indicated for the core features or RAD or DSED. (NE)

Recommendation 10. Clinicians should not administer interventions designed to enhance attachment that involves noncontingent physical restraint or coercion (e.g., "therapeutic holding" or "compression holding"), ''reworking'' of trauma (e. g., "rebirthing therapy), or promotion of regression for "reattachment'' because they have no empirical support and have been associated with serious harm, including death. (NE)[9]

g., "rebirthing therapy), or promotion of regression for "reattachment'' because they have no empirical support and have been associated with serious harm, including death. (NE)[9]

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

References

- 1.

Milot T, Ethier LS, St-Laurent D, Provost MA. The role of trauma symptoms in the development of behavioral problems in maltreated preschoolers. Child Abuse Negl. 2010 Apr;34(4):225-34. [PubMed: 20303174]

- 2.

Moran K, McDonald J, Jackson A, Turnbull S, Minnis H. A study of Attachment Disorders in young offenders attending specialist services. Child Abuse Negl. 2017 Mar;65:77-87. [PubMed: 28126657]

- 3.

Winston R, Chicot R. The importance of early bonding on the long-term mental health and resilience of children. London J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2016;8(1):12-14. [PMC free article: PMC5330336] [PubMed: 28250823]

- 4.

Lionetti F, Pastore M, Barone L. Attachment in institutionalized children: a review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2015 Apr;42:135-45. [PubMed: 25747874]

- 5.

Spratt EG, Friedenberg SL, Swenson CC, Larosa A, De Bellis MD, Macias MM, Summer AP, Hulsey TC, Runyan DK, Brady KT. The Effects of Early Neglect on Cognitive, Language, and Behavioral Functioning in Childhood. Psychology (Irvine). 2012 Feb 01;3(2):175-182. [PMC free article: PMC3652241] [PubMed: 23678396]

- 6.

Pritchett R, Pritchett J, Marshall E, Davidson C, Minnis H. Reactive attachment disorder in the general population: a hidden ESSENCE disorder. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:818157. [PMC free article: PMC3654285] [PubMed: 23710150]

- 7.

Shipman K, Taussig H. Mental health treatment of child abuse and neglect: the promise of evidence-based practice. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009 Apr;56(2):417-28. [PubMed: 19358925]

- 8.

Braun K, Bock J.

The experience-dependent maturation of prefronto-limbic circuits and the origin of developmental psychopathology: implications for the pathogenesis and therapy of behavioural disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011 Sep;53 Suppl 4:14-8. [PubMed: 21950388]

The experience-dependent maturation of prefronto-limbic circuits and the origin of developmental psychopathology: implications for the pathogenesis and therapy of behavioural disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011 Sep;53 Suppl 4:14-8. [PubMed: 21950388]- 9.

Zeanah CH, Chesher T, Boris NW., American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI). Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Reactive Attachment Disorder and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Nov;55(11):990-1003. [PubMed: 27806867]

Attachment disorders in children - causes, symptoms, diagnosis and treatment

Attachment disorder in children - a complex of mental disorders that develops in the absence of emotional contact with caregivers: parents, guardians. It is manifested by timidity, alertness, difficulties in adapting and establishing relationships, behavioral disorders (aggression, auto-aggression), and intellectual retardation. The main diagnostic methods are anamnesis, clinical conversation, observation of the child's behavior, child-parent relationships. Psychodiagnostics is performed, which reveals emotional and volitional disorders, deviations of the cognitive sphere. Treatment is carried out by methods of individual, family psychotherapy, supplemented by medication correction, psychological counseling for parents and teachers.

The main diagnostic methods are anamnesis, clinical conversation, observation of the child's behavior, child-parent relationships. Psychodiagnostics is performed, which reveals emotional and volitional disorders, deviations of the cognitive sphere. Treatment is carried out by methods of individual, family psychotherapy, supplemented by medication correction, psychological counseling for parents and teachers.

General information

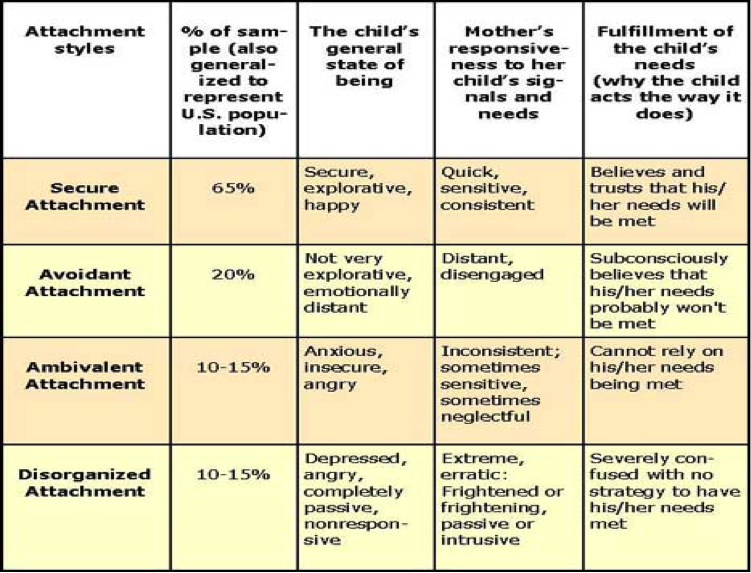

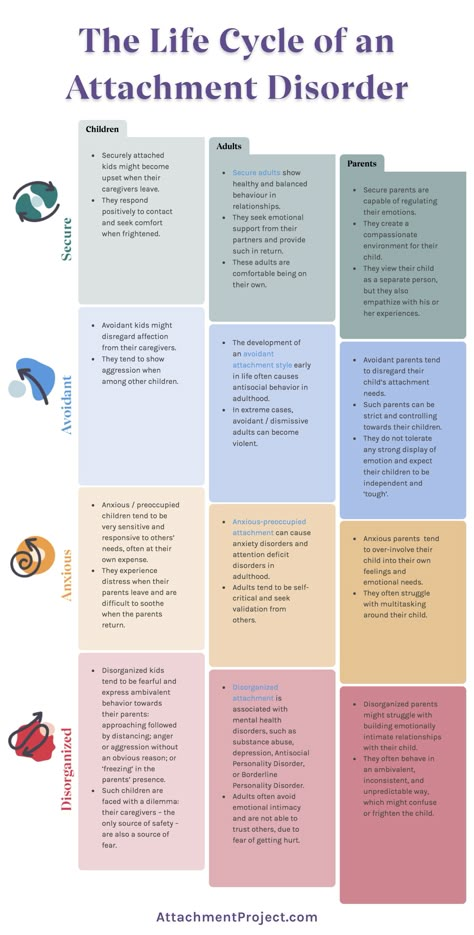

Attachment is a feeling of emotional intimacy formed on the basis of sympathy, love, devotion. Attachment disorders (AD) in children are understood as a group of behavioral and emotional disorders. Psychiatrists refer to them as Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD). Its peculiarity is the lack of trusting relationships with guardians, parents as a result of pathological upbringing. Everyday understanding of RP includes unstable, “cold” relationships with one of the parents, grandparents, orphanage teachers. Such cases are more appropriately called insecure attachment. They are a variant of normal development and are not associated with social maladjustment. The prevalence of reactive attachment disorder is less than 1%, insecure attachment is 40%.

They are a variant of normal development and are not associated with social maladjustment. The prevalence of reactive attachment disorder is less than 1%, insecure attachment is 40%.

Attachment disorders in children

Causes of attachment disorders in children

There are physiological features that are considered as risk factors for RAD. Instability of the autonomic nervous system, imbalance of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reduce stress resistance. The probability of pathological emotional, behavioral reactions increases. The immediate causes of the development of attachment disorders are situations where the child is not able to establish, maintain a stable relationship with parents:

- Defective maternal contact. RRP develops in children whose mothers abuse alcohol, drugs, suffer from postpartum depression, mental disorders, do not accept a child (unwanted pregnancy), use violence, humiliation.

- Absence of parents (guardians).

The early separation from the mother, the placement of the child in a hospital, a baby home, a boarding school becomes a provoking factor. The functions of adults are limited to the performance of hygienic, medical procedures. Established emotional ties are quickly destroyed due to a change in the place of residence of the child, the work schedule of staff, staff turnover, and refusal to guardianship of foster parents.

The early separation from the mother, the placement of the child in a hospital, a baby home, a boarding school becomes a provoking factor. The functions of adults are limited to the performance of hygienic, medical procedures. Established emotional ties are quickly destroyed due to a change in the place of residence of the child, the work schedule of staff, staff turnover, and refusal to guardianship of foster parents.

Pathogenesis

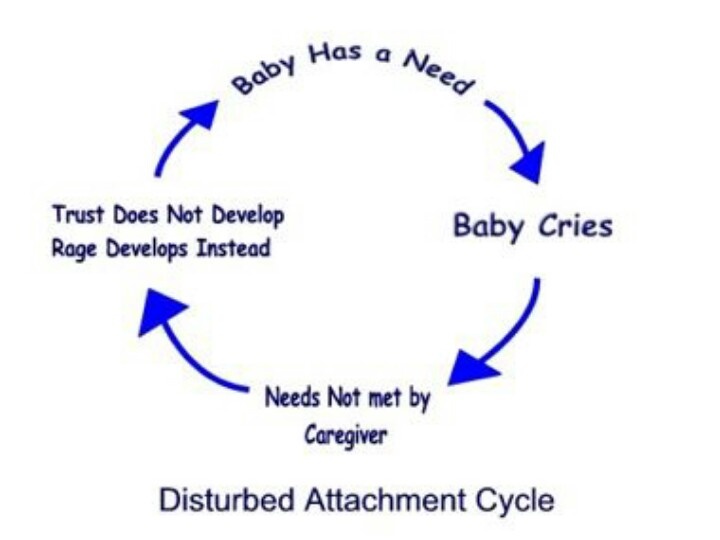

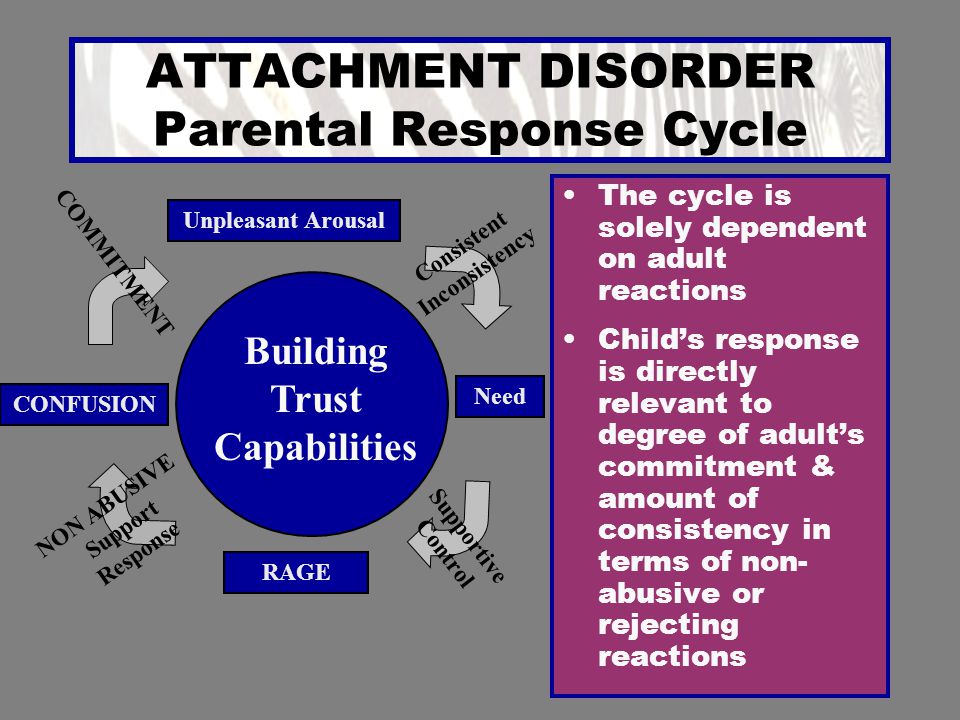

The basis for the formation of attachment disorders is the negative experience of establishing close, friendly relationships. The child cries, tries to attract attention, express his needs (hunger, discomfort, loneliness). If he does not receive help from an adult or receives an inadequate response - swearing, beatings - the situation becomes stressful. Failures occur at the physiological level: the concentration of hormones changes, excitation processes in the nervous system, muscle tension predominate. Gradually, the environment begins to be perceived as dangerous. There is a need to defend, to show aggression, to independently control the situation. Trust, affection are replaced by a hostile attitude, indifference to the mother, father, guardian.

There is a need to defend, to show aggression, to independently control the situation. Trust, affection are replaced by a hostile attitude, indifference to the mother, father, guardian.

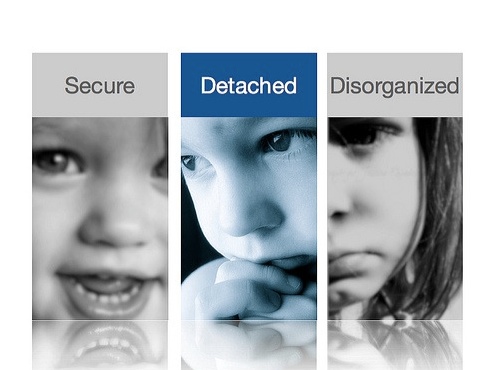

Classification

Attachment disorders are classified according to the characteristics of their clinical manifestations. With this in mind, two types of violations are distinguished:

- Disinhibited . It's called disinhibited. It is characterized by a detailed clinical picture. The child lacks selectivity in establishing contacts. Social relationships are not sufficiently modulated. Babies are not wary of strangers, older children are promiscuous in their choice of friends. This form is the result of a frequent change of an adult (parent, educator, guardian).

- Inhibited . Symptoms are mild. Social contacts are suppressed, inhibited, often have an ambivalent orientation - hatred-love, acceptance-rejection. Depression prevails, an aggressive reaction to suffering.

This type of disorder is formed as a result of abuse by an adult with an infant.

This type of disorder is formed as a result of abuse by an adult with an infant.

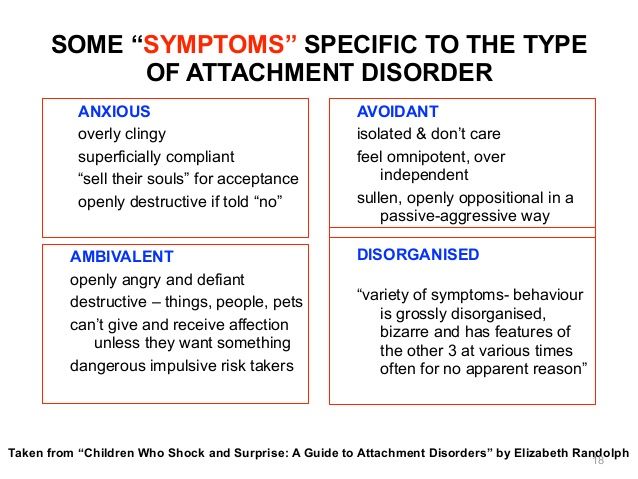

Another classification is more descriptive. The etiological factor, the direction of the child's behavior, the features of establishing contact are taken into account. There are four types of attachment:

- Negative . The reasons are neglect or overprotection. The behavior of the child is aimed at provoking negative attention, irritation, punishment.

- Ambivalent . The basis is hysterical reactions, the inconsistency of adults. It is manifested by categorical, duality (aggressiveness-kindness, affection-beating) of interaction with others.

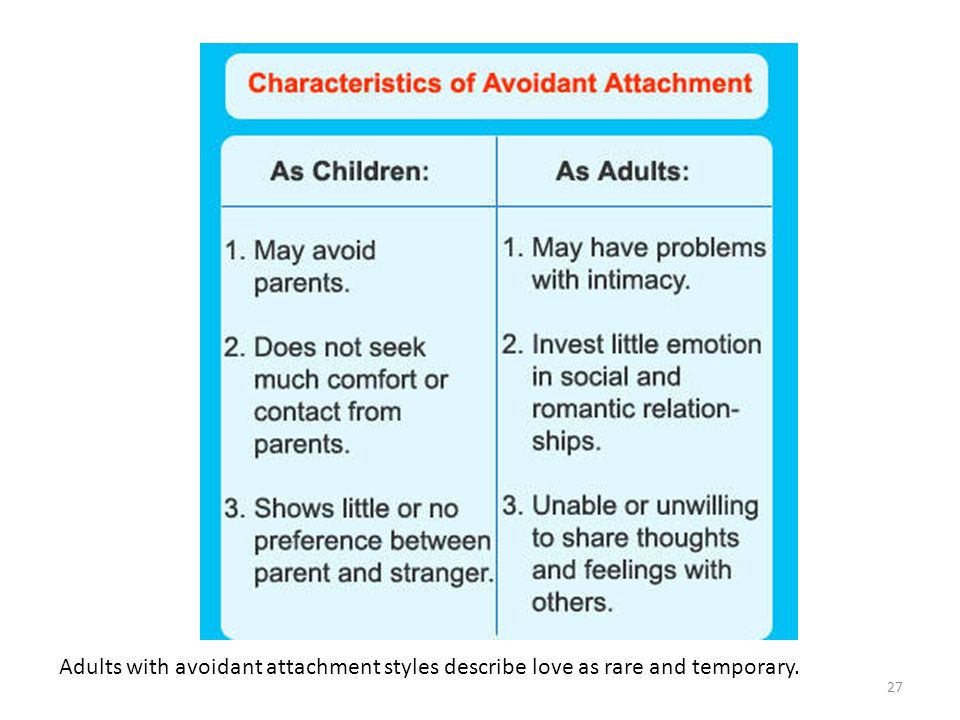

- Avoidant . It develops after a break in relationships with mom, dad, guardian. It is manifested by isolation, gloom, distrust.

- Disorganized . Occurs after a cruel relationship, violence. Manifestations of cruelty, resistance to attempts at interaction are characteristic.

Symptoms of attachment disorders in children

Attachment disorders are manifested by a spectrum of symptoms, the severity and completeness of which increases from single reactions to a formed reactive disorder. Infants, toddlers up to 5-6 years old avoid eye contact, rarely smile, do not rejoice at the approach of an adult. With an inhibited form of the disorder, they reject attempts to establish contact, get closer, and calm down. Do not reach for a toy offered by an adult. Left alone, remain calm. They are indifferent to the care of another person. Often there is inconsolable quiet crying for no reason. In the disinhibited form, children are extremely dependent, seek comfort, safety from strangers, seek to establish contacts with them, but reject their parents.

Lack of trusting emotional interaction with a significant adult contributes to mental retardation: infants are inactive, there is no babbling, cooing, speech development is delayed in children, and interest in play is weak. With age, mental retardation becomes more pronounced, the child hardly masters the curriculum. Children of preschool and school age develop an aversion to touching and hugging. Attempts to establish physical contact cause inadequate reactions of laughter, crying, anger, fear.

With age, mental retardation becomes more pronounced, the child hardly masters the curriculum. Children of preschool and school age develop an aversion to touching and hugging. Attempts to establish physical contact cause inadequate reactions of laughter, crying, anger, fear.

The need to maintain control, to protect oneself is manifested by the desire to maintain distance. With psychological rapprochement, children become naughty, impudent. Anger is expressed through tantrums, manipulation, aggressive behavior. Growing up, patients begin to understand the social unacceptability of anger, mask it with "random" actions - hitting the ball, shaking hands painfully or hugging. Difficulties in identifying one's own feelings, the feelings of others, misunderstanding the true purpose of affection, stroking, close relationships are manifested by a chaotic building of relationships: strangers arouse interest, kindness, and parents and relatives indifference. After making mistakes, unacceptable behavior, there is no feeling of guilt.

Complications

Mental retardation is a frequent complication of attachment disorders. The lack of close contact with an adult leads to a decrease in cognitive interest: the baby does not reach for bright objects, toys, slowly masters manipulative actions, there is no desire to establish verbal contact. Transfer and acceptance of experience are violated. The lag of thinking, active attention, speech develops. If RP is not diagnosed in time, social maladjustment increases. Volitional, emotional disturbances, behavioral deviations become stable character traits. Adolescents develop psychopathy, neurosis, deviant forms of behavior.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of attachment disorders in children is carried out by a psychiatrist, a clinical psychologist. The comprehensive examination procedure includes:

- Survey. The doctor specifies the symptoms, their duration, severity. He asks about the composition of the family, the occupation of the parents, the presence of mental illness, pathological addictions.

It finds out the features of the course of pregnancy, the relationship between the mother and the baby after birth, the involvement in the process of raising the father, grandparents, the presence of socialization problems in kindergarten, school (whether the child shows aggression, shyness, pugnacity, hysteria).

It finds out the features of the course of pregnancy, the relationship between the mother and the baby after birth, the involvement in the process of raising the father, grandparents, the presence of socialization problems in kindergarten, school (whether the child shows aggression, shyness, pugnacity, hysteria). - Observation. The specialist focuses on child-parent relationships. Marks benevolence, hostility, interest in contact, negativism, disobedience, acceptance of bodily contact, desire to communicate. Defines the parenting style.

- Collection of additional data. The results of the conversation are supplemented by the characteristics of teachers, educators of orphanages, extracts from the conclusions of narrow specialists: a neurologist, an endocrinologist, an otolaryngologist, an ophthalmologist.

- Psychodiagnostics. Personality questionnaires, projective methods reveal the characteristics of self-esteem, the emotional-volitional sphere of the child, his orientation towards the establishment of social interactions, attitude towards others.

It is important to differentiate attachment disorders from persistent intellectual disabilities, childhood autism, acute stress reaction, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The key role is played by the parent-child relationship (lack of attachment), normal learning.

Treatment of attachment disorders in children

Psychotherapeutic treatment is the basis that changes the relationship between the child and parents, close relatives. Drug therapy is necessary to correct concomitant emotional and cognitive impairments. An integrated approach includes the following types of treatment:

- Child psychotherapy. The purpose of the sessions is to reduce emotional tension, eliminate isolation, distrust, and fears. They are held in the form of a game, reading fairy tales, creative activities.

- Family psychotherapy. Psychotherapeutic exercises, tasks, conversations eliminate alienation, restore emotional, verbal contact, bodily acceptance by the child of parents.

- Parent counseling. Psychologist, psychotherapist tells parents about the features of the course of the disorder, causes, methods of correction. Gives recommendations on building intra-family relationships, examines in detail typical conflict, difficult situations of interaction.

Drug treatment can improve the emotional background, relieve acute reactions, which ensures a higher effectiveness of psychotherapy. Self-administration of drugs is not advisable.

Prognosis and prevention

The earlier the treatment of attachment pathologies is started, the better the prognosis. When loving, caring family relationships are restored, infants and young children are almost completely free of the disorder. Preschoolers and schoolchildren require specialized assistance, the outcome of treatment depends on the joint efforts of parents and a psychotherapist. Prevention of attachment disorders is the creation of psychological comfort, which forms a sense of security, basic trust. The attitude of the mother is important, it lays the foundation for attachment, mental health.

The attitude of the mother is important, it lays the foundation for attachment, mental health.

Question 4. Attachment disorders

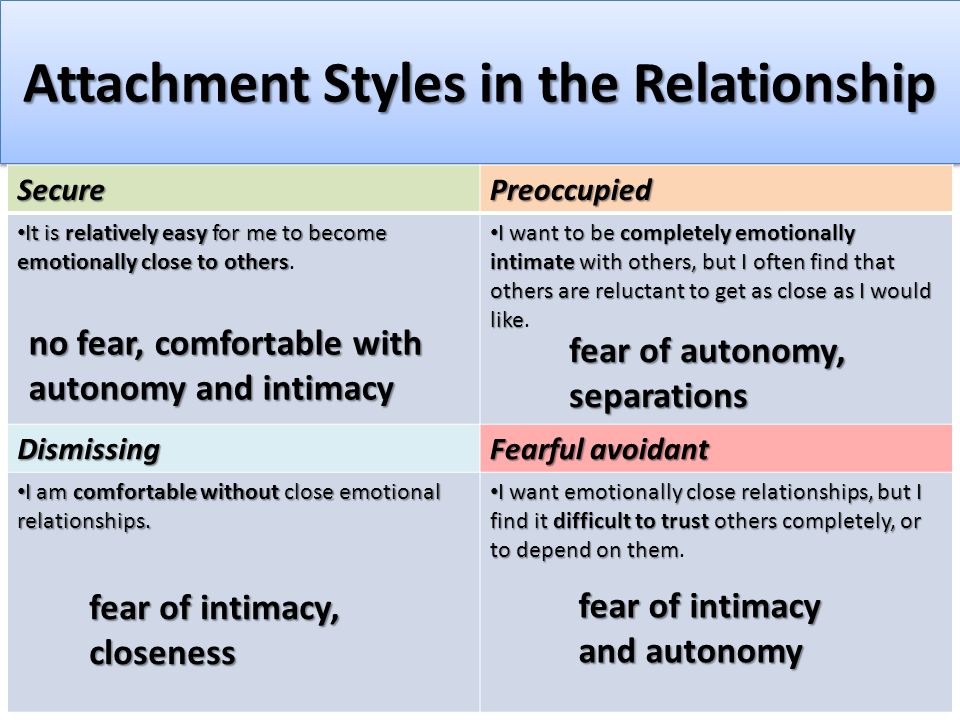

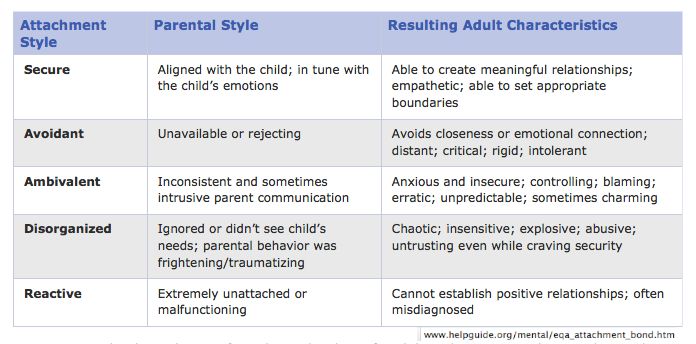

In the process of studying interaction disorders as a result attachment disorders have been highlighted the following attachment disorders. Specially developed object relations of the studied personalities served diagnostic criteria for distinguishing these three groups of disorders attachments.

Diffuse or reactive attachment. In this case it is difficult for the examinees to distinguish the object, the child being studied cannot distinguish specific person for affection. it disorder is characterized by the absence attachments, for example, in children in orphanages or other orphanages institutions. This can be considered as defensive reaction of adaptation. Similar the situation is developing in children in families alcoholics.

illegible attachment. Also observed in orphanage institutions. Children cling to to all people. The word mom does not have for them values.

The word mom does not have for them values.

Uncertain - tied. The specificity of this affection becomes lack feelings of shyness.

Aggressively tied. In individuals with this disorder attachments observed protective identification mechanisms with the aggressor. Identification with the aggressor provides a means calming and controlling aggressive impulses. It is likely that the projective identification is used by those individuals whose object of attachment is broken, who could soothe and restrain their excitement. Such individuals are rarely experiencing physical pain.

Adult attachment evaluated using linguistic analysis of memories of parents, received during interviews for adults about attachments M. Maine.

Described for adults three styles of non-protective attachment: rejecting, stuck unresolved. The last kind of attachment arises from the loss or psychotrauma.

The authors of the theory attachments claim that on mental development and functioning affect attachment to the persons who guarded person at an early age. Insufficient or pathological attachment to childhood determines the development of forms maladaptive attachment in adulthood life.

Insufficient or pathological attachment to childhood determines the development of forms maladaptive attachment in adulthood life.

non-protective attachment at an early age serve as a risk factor, predisposing or being cause of mental development disorders. Rutter (Gwen Adshead, 1988) claims that lack of affection at an early age can be a factor risk of developing a mental disorder adult in the future, through interaction with other factors that reduce or increasing mental resistance person, increasing or decreasing risk of developing a mental disorder in adulthood. Leads to this conclusion understanding mental disorder as problems encountered in the regulation mental homeostasis. Based it can be assumed that it is enough a large number of people with mental will have a history of disorders insufficient or pathological attachment. However, the disease will not develop in all these people. Although according to G. Adshead (1988) high the frequency of occurrence of the studied insufficient or unprotective affection is seen in psychiatric departments. They can attributed to individuals whose "internal models" are not able to cope with stress factors and which developed maladaptive forms behavior in response to external or internal conflicts.

They can attributed to individuals whose "internal models" are not able to cope with stress factors and which developed maladaptive forms behavior in response to external or internal conflicts.

Connection established depression in adulthood with loss object of affection in the early period life and hostility from parents. Attachment disorders found in patients with major psychosis disorders of pathological reactions bereavement. Some of maladaptive forms of behavior can be treated as a replay psychotraumatic situations.

Threat perception adults and the risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder can also depend on forms of attachment and reactions on psychotrauma in early life. Disturbed behavior can also be reaction to a specific object attachments. It is also likely that mental illness is powerful stimulant of behavior directed to create a relationship of affection, since the threat of loss is strong, both external, and internal security.

Most likely, that copying children's forms is unprotective attachments in adulthood takes place in the context of dependent relationships, including to your child, which is related to occurrence of ill-treatment child.

Adults deprived of worries in childhood, seek to care about others in their professional life. One of the manifestations of unprotective attachments in childhood, described by J. Bowlby, is the setting style connection, called compulsive rendering help when a person is attentive to the needs of others and ignores their own. J. Bowlby argued that in such children, who develop such attachment a false adult life is formed - a concept similar to the concept of a false self Winnicott.

As part of the clinical early childhood psychiatry time the criteria for the disorder are highlighted attachments (ICD-10). emergence attachment disorders possible from 8 months of age. To pathology carry a dual type of attachment – insecure attachment anxious - resistive type. unsafe avoidant attachment regarded as conditional pathological. There are 2 types of disorders attachments - reactive (avoidant) type) and disinhibited (negative, neurotic type). These distortions attachments lead to social - personality disorders, make it difficult school adaptation, interpersonal relationships, emotional connections in your family. Various researchers showed a negative impact, both short-term and long term separation from mother further development of the child (Anna Freud, Rutter, Fahlberg, Bowlby and others). With adequate fast replacing the mother with another loved one (another figure of affection) consequences can be smoothed while placement in a shelter and subsequent deprivation may exacerbate negative effects. for the child and influence the future mental development (Goldfarb, Dunn, Spitz). Rutter showed that separation from his mother Although it is a risk factor, it is not defines completely perspectives social and personal development. Overcoming attachment disorders especially in children who have never had attachment experience does not occur just by itselfby the premises child to a new family (Durkin, Frieberg). These data formed the basis of the idea of a replacement parenthood and compulsory further family accompaniment as a basis for adaptation.

Various researchers showed a negative impact, both short-term and long term separation from mother further development of the child (Anna Freud, Rutter, Fahlberg, Bowlby and others). With adequate fast replacing the mother with another loved one (another figure of affection) consequences can be smoothed while placement in a shelter and subsequent deprivation may exacerbate negative effects. for the child and influence the future mental development (Goldfarb, Dunn, Spitz). Rutter showed that separation from his mother Although it is a risk factor, it is not defines completely perspectives social and personal development. Overcoming attachment disorders especially in children who have never had attachment experience does not occur just by itselfby the premises child to a new family (Durkin, Frieberg). These data formed the basis of the idea of a replacement parenthood and compulsory further family accompaniment as a basis for adaptation.

Vera Fahlberg highlights 3 ways to "awaken" and form attachment in children who have lost or without affection:

-

cycle "excitation - relaxation" (need - expression of protest - satisfaction needs - comfort - new need - etc.

),

), -

"cycle positive interaction” (parent initiates a stimulating interaction with a child - the child responds positive - etc.)

-

"cycle actively seeking outside help” (parent apply to various organizations where he can get help in treatment, learning, in joint play, leisure and etc.).

First cycle initiated by the child himself declares his needs, the second requires initiative, both the child and adult. The last way combines child and adults in the process of their common interaction with the environment. In any case, the substitute parent is required constantly manifest and unconditional "perseverance" in trying to establish emotional contact with the child and his preserve, not only "care" for child, but also to support him, to show empathy when the child shows his feelings, physically soothe.

Substitute readiness parent to give emotional warmth and accept the child as he is — are decisive for achieving success in forming attachment child to a new family. Turning on a child into a new family means involving him into its rituals and customs, which may different from his own. Quality relationships with other family members and their willingness to accept a child and emotional openness is also essential bonding factor. But the most important factor is integration of attachments - former and newly emerging, relationship building child to his past and parents. A family with this problem may not cope and required organized assistance from service professionals.

Turning on a child into a new family means involving him into its rituals and customs, which may different from his own. Quality relationships with other family members and their willingness to accept a child and emotional openness is also essential bonding factor. But the most important factor is integration of attachments - former and newly emerging, relationship building child to his past and parents. A family with this problem may not cope and required organized assistance from service professionals.

In this way, adaptation and socialization will be be the placement of the child in a new family and educational organization space, allowing in the process interaction and mutual acceptance of the child and families compensate for the negative consequences of injuries, to form a new affection and create conditions for successful development of the child.

For understanding essence of adaptation and for the correct organization of the work of teachers and patronage educators need understanding dynamics of the states of a child who survived break with family.