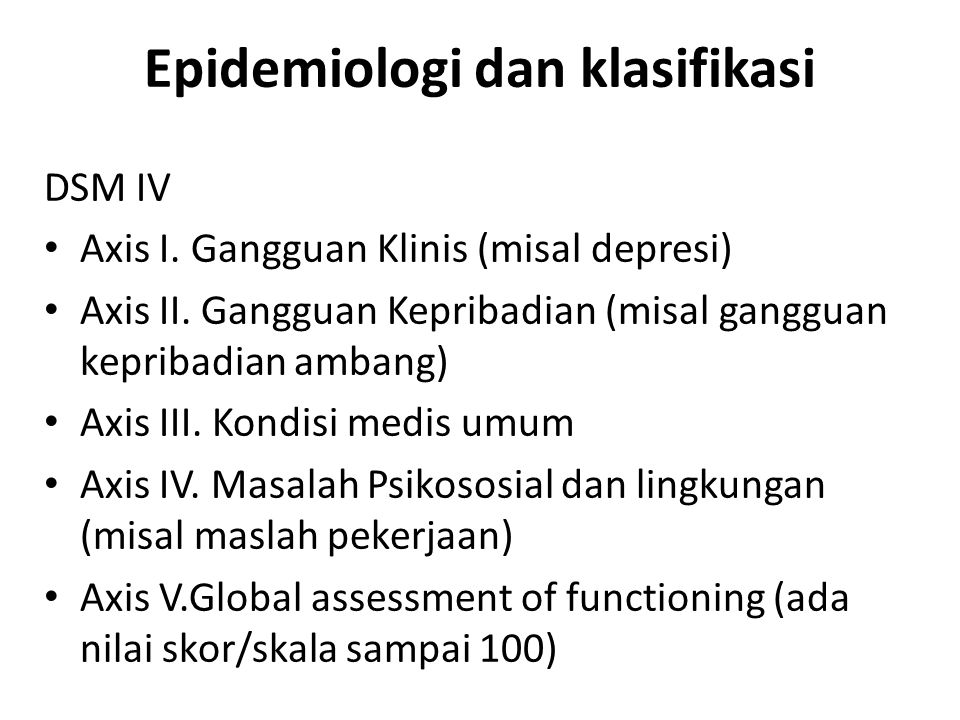

Grief reaction dsm iv code

Uncomplicated Bereavement & Prolonged Grief Disorder DSM-5

Grief is a normal human response to the pain of losing someone. It can be brutal, anguished, disorienting, maddening, enraging, and lonely.

But ultimately, people do emerge from grief. They may feel forever changed; however, they do find meaning in their lives again. Those difficult feelings eventually make way for positive emotions and experiences again. This is uncomplicated bereavement.

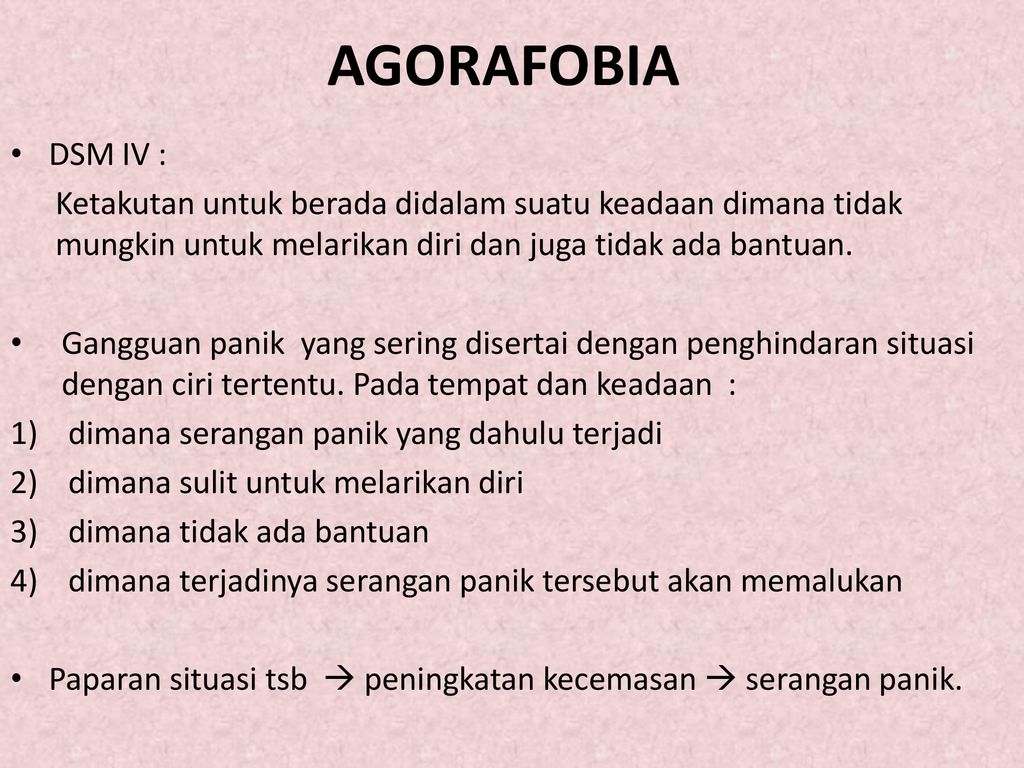

For others, the loss of a loved one can make life feel meaningless — even unsurvivable. They struggle to experience anything but those debilitating feelings, long after the death of their loved one. This is (or could be) prolonged grief disorder.

Let’s take a closer look at both uncomplicated bereavement and prolonged grief disorder as well as how individuals can effectively grieve the loss of a loved one and heal.

Definition of Uncomplicated Bereavement DSM-5Uncomplicated bereavement is normal grief. One might experience difficult feelings following the loss of a loved one, but within weeks to months, they are able to return to normal life again. The symptoms of uncomplicated grief may resemble those of a major depressive episode or even a physical disease.

If someone’s disabling grief persists for longer than 6 months to a year, as it does in about 10% of cases, it might instead be considered an adjustment disorder or prolonged grief disorder (PGD), also known as complicated grief.

Uncomplicated Bereavement vs. Prolonged Grief DisorderMost people can effectively deal with the loss of a loved one with the help of family, friends, and their personal belief systems. Their grieving process may include feelings of sadness, anger, and guilt, as well as insomnia and lack of appetite. However, others have a more difficult time processing this degree of loss in the long term and find it impossible to continue life as they knew it — these individuals might have prolonged grief disorder.

In addition to the above risk factors, the circumstances surrounding the death of a loved one as well as the grieving person’s relationship with the lost individual can both have a major effect on how one handles the loss. For example, it may be particularly hard for an individual to process an unexpected or sudden death, or a suicide, just as it is extraordinarily difficult for a child to grieve the loss of a parent, a spouse to grieve the loss of their partner, and a parent to grieve the loss of a child, including through miscarriage.

Symptoms of Prolonged Grief Disorder DSM-5To receive a diagnosis of prolonged grief disorder as an adult, the loss must have occurred at least a year ago — and for children and adolescents, at least 6 months ago. Additionally, the individual must have experienced at least three of the following symptoms nearly every day for the last month or longer:

- Disrupted identity

- A feeling of disbelief about the death

- Avoiding reminders that the individual has passed

- Intense emotional pain directly related to the loss

- Trouble getting back to normal life

- Numbness

- Feeling that life is meaningless

- Loneliness and detachment from others

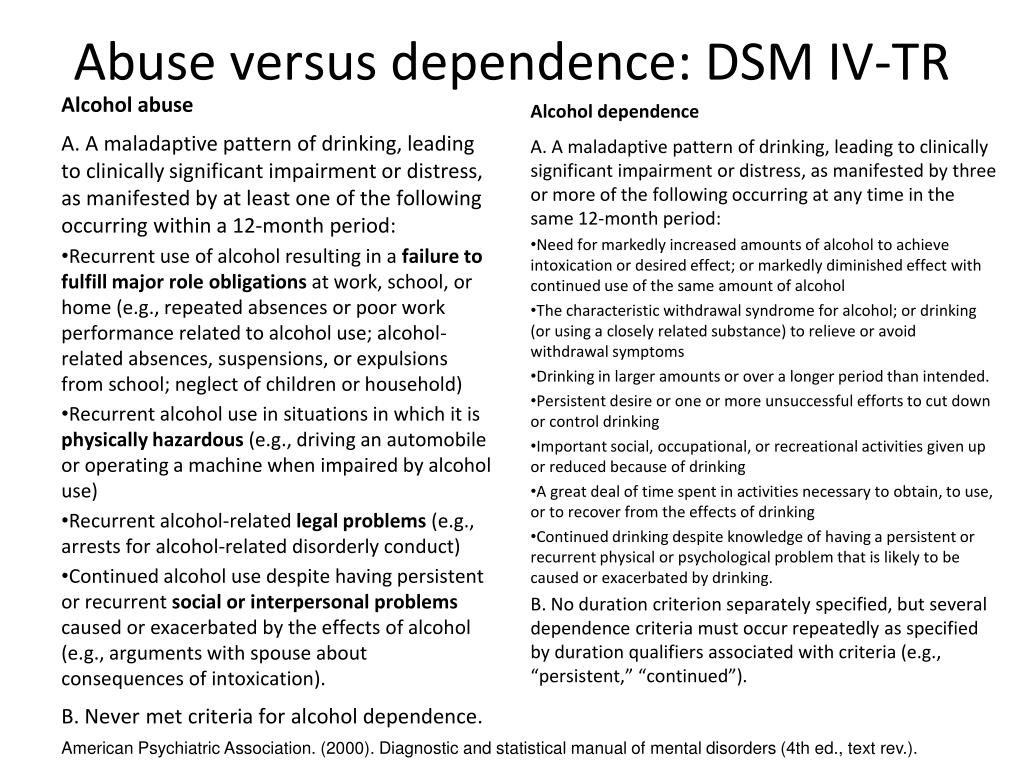

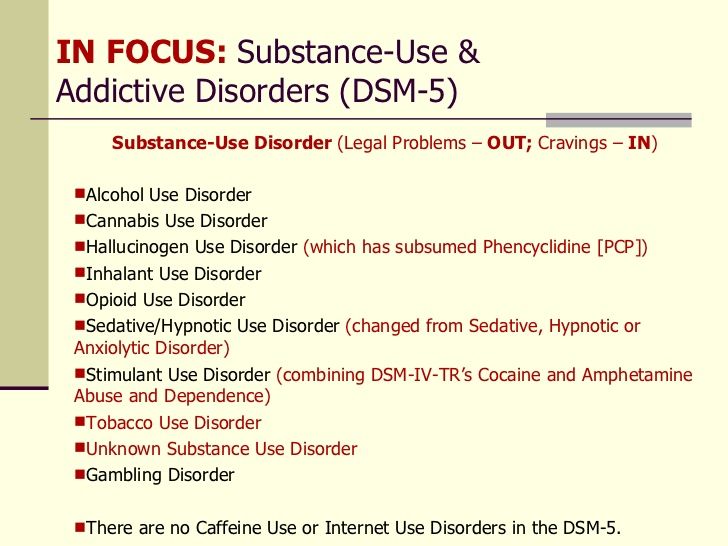

Those at a greater risk of developing prolonged grief disorder (PGD) include those who have a history of mental health issues. And for those who have suffered from a substance use disorder, bereavement may be a trigger—this loss could potentially increase their risk of relapsing.

And for those who have suffered from a substance use disorder, bereavement may be a trigger—this loss could potentially increase their risk of relapsing.

Grief is a difficult, yet necessary and unavoidable part of life. When we grieve, we illustrate the degree of our love for the person lost. We can also learn to continue on with our lives while preserving the memories and legacy of our loved ones. Grief work can look different for everyone but might include: separating oneself from the person who died, learning how to readjust to a world without the individual, and working to create new relationships.

Unfortunately, some of us are left more broken than others and need some extra care and guidance to heal from the pain of losing a loved one. In such cases, individuals can seek professional help through grief counseling or therapy. Grief counseling helps the bereaved manage their reactions to the loss, without letting go of their loved one. This type of therapy can do the following:

This type of therapy can do the following:

- Psychoeducate about the normal stages of grieving

- Encourage the individual to talk about the loss and express their emotions

- Identify coping issues and recommend more productive pathways

- Help the bereaved shift focus from the deceased individual to their own life

- Provide regular emotional support

Targeted grief treatment is different from depression treatment, and evidence suggests that the former is more effective in helping bereaved individuals. Depression tends to be more of a “free-floating,” nonspecific sadness, whereas grief is characterized by preoccupation with a particular person.

3 Popular Movies That Tackle the Difficult Subject of Loss and Grief“P.S. I Love You”: In this film, the main character Holly loses her husband and has an extremely difficult time dealing with his death. The movie follows her as she searches for and discovers 10 messages that her late husband left behind. These messages, along with the undying love of her friends and family, help Holly come to terms with the loss.

The movie follows her as she searches for and discovers 10 messages that her late husband left behind. These messages, along with the undying love of her friends and family, help Holly come to terms with the loss.

“Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close”: This movie, which is based on a renowned novel of the same name, follows a young boy as he journeys through New York City to find a lock—a lock for a key left behind by his dad, who died in the attack on the World Trade Center on September 11. Unsure how to deal with his grief and loss, Oskar obsesses over finding this lock but finally learns to confront his feelings with the help of all the New York City residents he meets.

“Marley and Me”: The movie that made even the toughest people tear up—this film is based on an autobiography of the same name, which follows a family as they maneuver through life with a crazy Labrador Retriever, Marley. By the end of it, the family has experienced significant ups and downs, but they have to face the hardest part yet in the closing scene: the loss of Marley. The kids draw pictures and write letters to Marley, which they bury with him in the backyard, and the parents reflect on the memories that began 13 years ago. This reminiscing ultimately helps the family come to terms with Marley’s death and their enormous loss.

The kids draw pictures and write letters to Marley, which they bury with him in the backyard, and the parents reflect on the memories that began 13 years ago. This reminiscing ultimately helps the family come to terms with Marley’s death and their enormous loss.

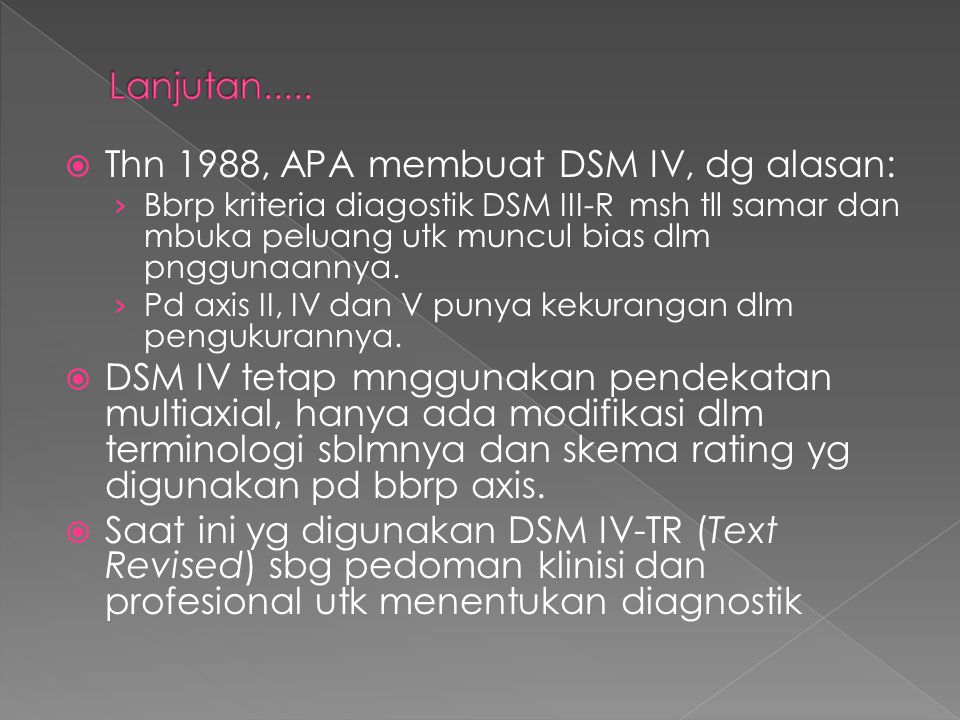

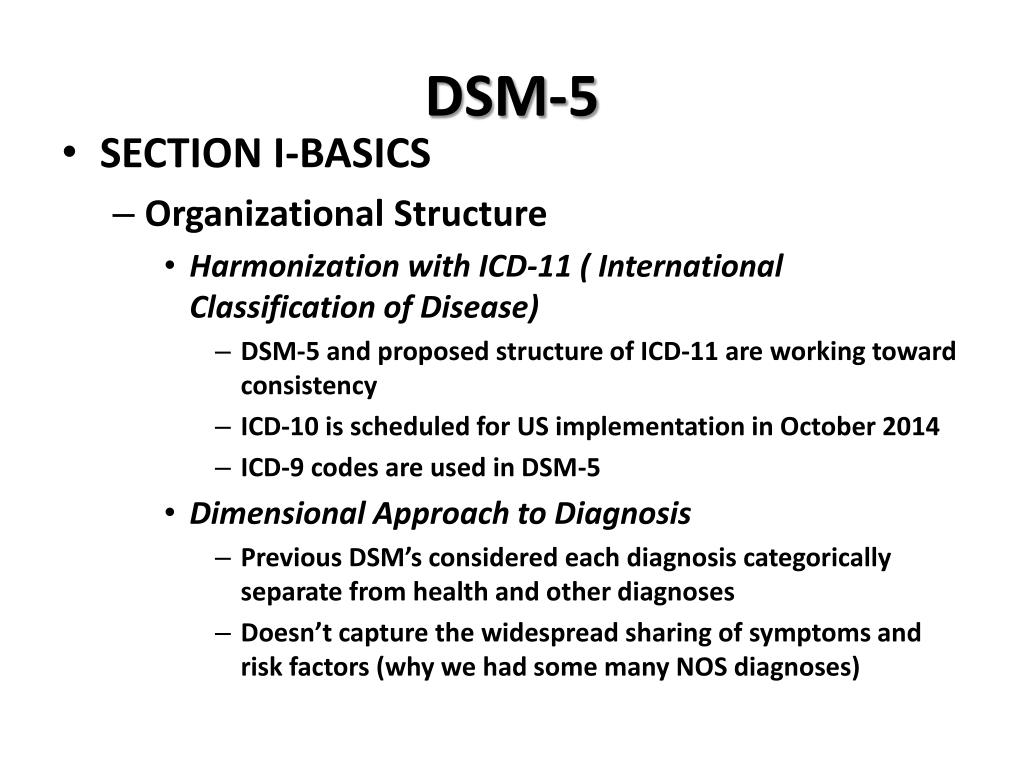

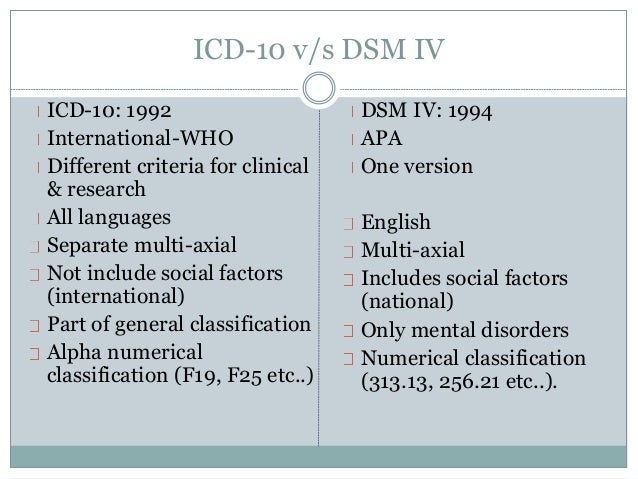

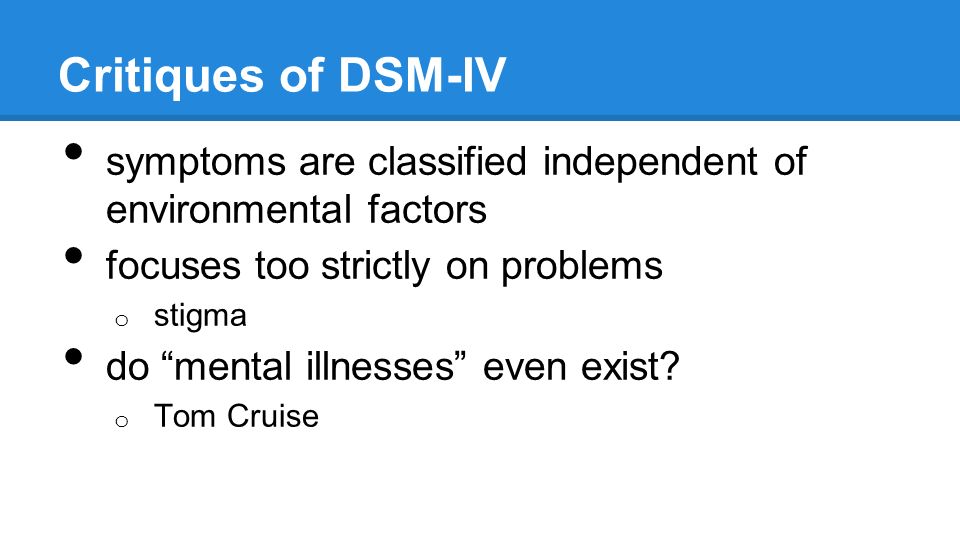

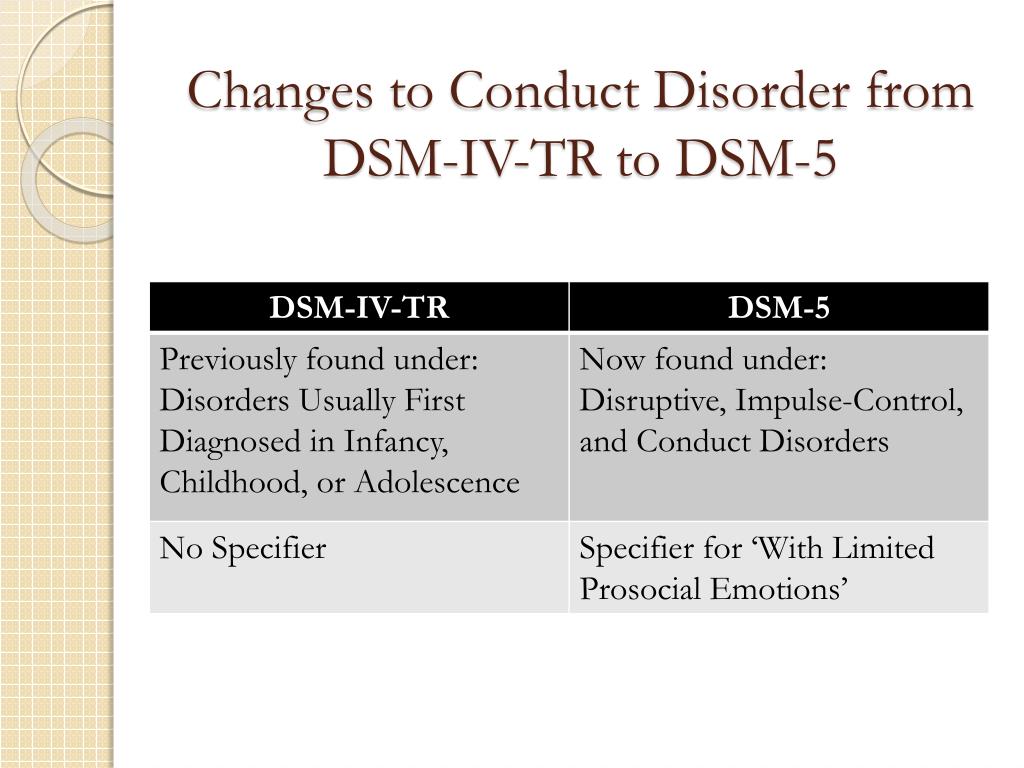

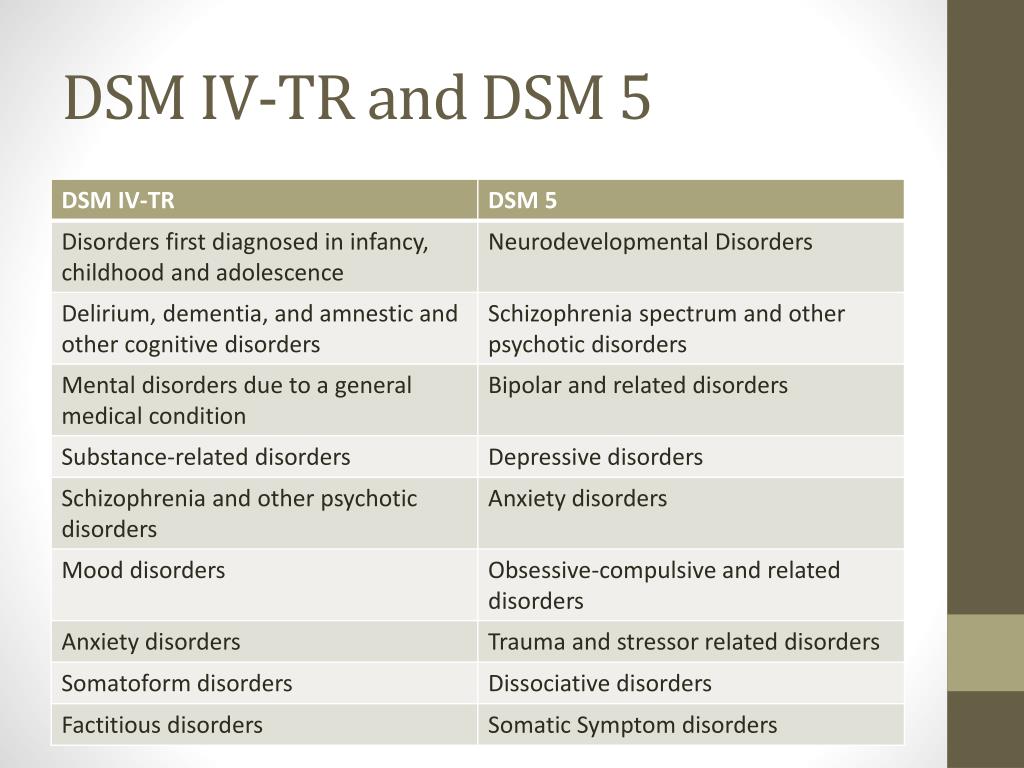

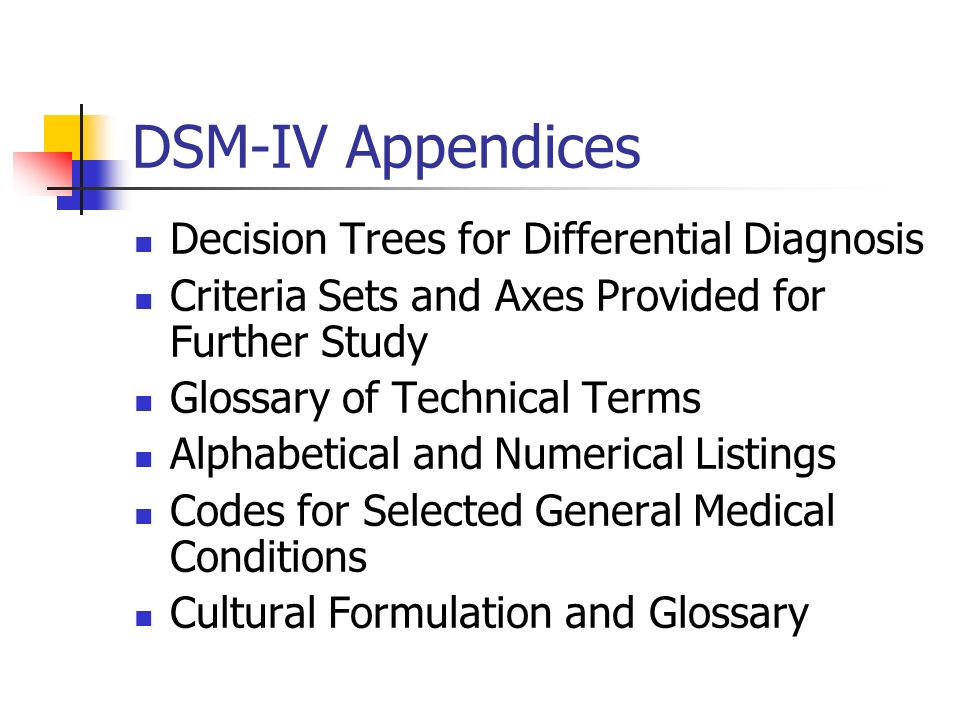

How the DSM-5 Got Grief, Bereavement Right

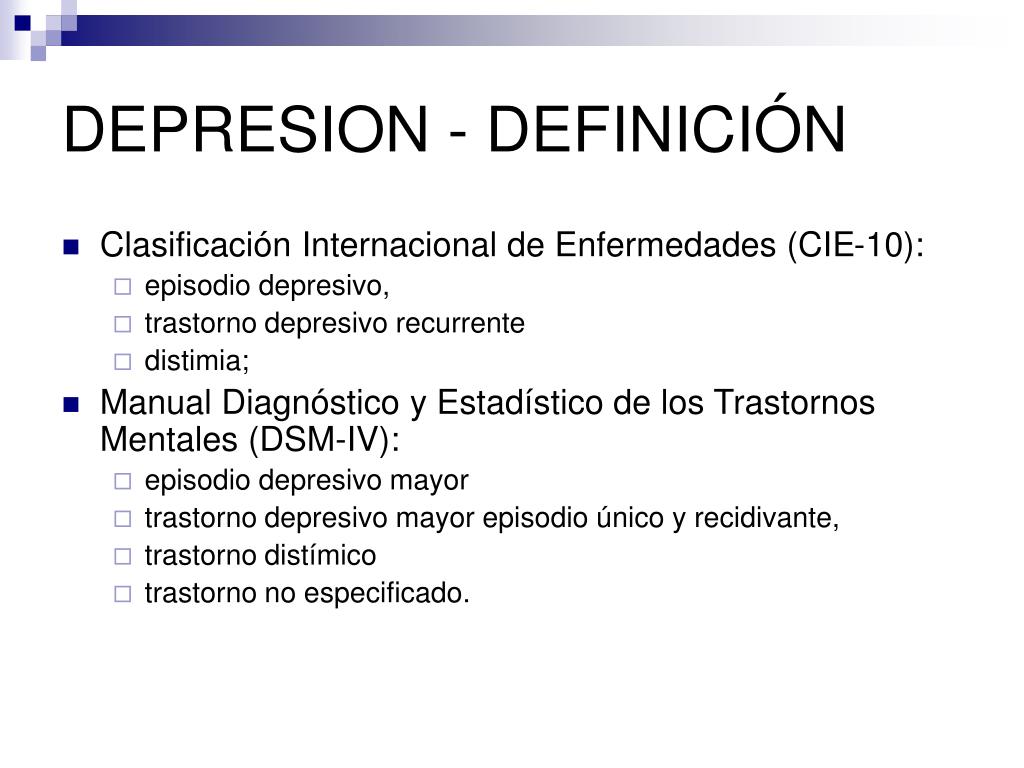

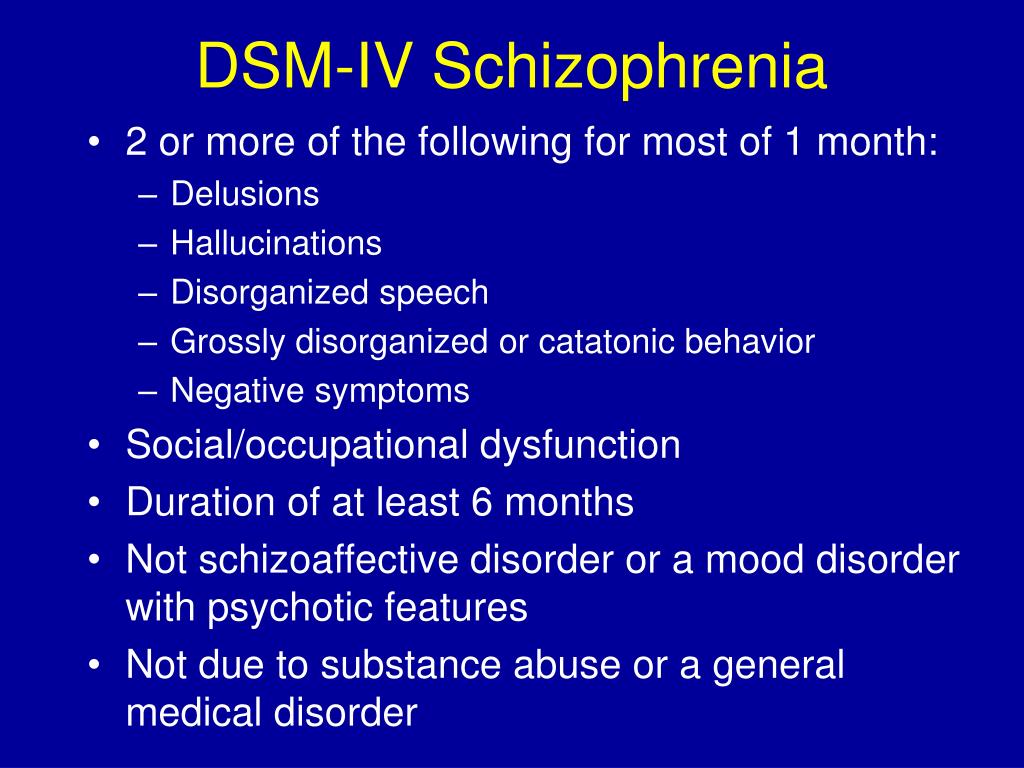

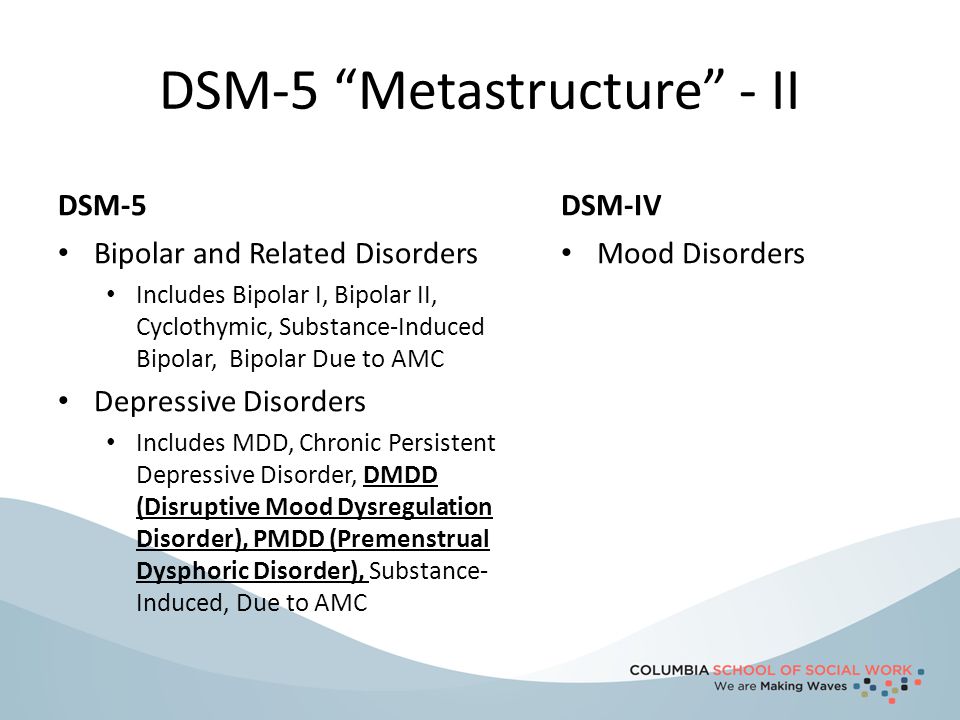

One of the charges leveled against psychiatry’s diagnostic categories is that they are often “politically motivated.” If that were true, the framers of the DSM-5 probably would have retained the so-called “bereavement exclusion” — a DSM-IV rule that instructed clinicians not to diagnose major depressive disorder (MDD) after the recent death of a loved one (bereavement) — even when the patient met the usual MDD criteria. An exception could be made only in certain cases; for example, if the patient were psychotic, suicidal, or severely impaired.

And yet, in the face of fierce criticism from many groups and organizations, the DSM-5 mood disorder experts stuck to the best available science and eliminated this exclusion rule.

The main reason is straightforward: most studies in the past 30 years have shown that depressive syndromes in the context of bereavement aren’t fundamentally different from depressive syndromes after other major losses — or from depression appearing “out of the blue.” (see Zisook et al, 2012, below). At the same time, the DSM-5 takes pains to parse the substantial differences between ordinary grief and major depressive disorder.

Unfortunately, the DSM-5’s decision continues to be misrepresented in the popular media.

Consider, for example, this statement in a recent (5/15/13) Reuters press release:

“Now [with DSM-5], if a father grieves for a murdered child for more than a couple of weeks, he is mentally ill.”

This statement is patently false and misleading. There is nothing in the elimination of the bereavement exclusion that would label bereaved persons “mentally ill” simply because they are “grieving” for their lost loved ones. Nor does the DSM-5 place any arbitrary time limit on ordinary grief, in the context of bereavement — another issue widely misrepresented in the general media, and even by some clinicians.

Nor does the DSM-5 place any arbitrary time limit on ordinary grief, in the context of bereavement — another issue widely misrepresented in the general media, and even by some clinicians.

By removing the bereavement exclusion, the DSM-5 says this: a person who meets the full symptom, severity, duration and impairment criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) will no longer be denied that diagnosis, solely because the person recently lost a loved one. Importantly, the death may or may not be the main, underlying cause of the person’s depression. There are, for example, many medical causes for depression that may happen to coincide with a recent death.

True: the two-week minimum duration for diagnosing MDD has been carried over from DSM-IV to DSM-5, and this remains problematic. My colleagues and I would have preferred a longer minimum period — say, three to four weeks — for diagnosing milder cases of depression, regardless of the presumed cause or “trigger.” Two weeks is sometimes not enough to permit a confident diagnosis, but this is true whether depression occurs after the death of a loved one; after the loss of house and home; after a divorce — or when depression appears “out of the blue. ” Why single out bereavement? Retaining the bereavement exclusion would not have solved the DSM-5’s “two-week problem.”

” Why single out bereavement? Retaining the bereavement exclusion would not have solved the DSM-5’s “two-week problem.”

And yet, nothing in the DSM-5 will compel psychiatrists or other clinicians to diagnose MDD after just two weeks of post-bereavement depressive symptoms. (Practically speaking, it would be rare for a bereaved person to seek professional help only two weeks after the death, unless suicidal ideation, psychosis, or extreme impairment was present — in which case, the bereavement exclusion would not have applied anyway).

Clinical judgment may warrant deferring the diagnosis for a few weeks, in order to see whether the bereaved patient “bounces back” or worsens. Some patients will improve spontaneously, while others will need only a brief period of supportive counseling — not medication. And, contrary to the claims of some critics, receiving the diagnosis of major depression will not prevent bereaved patients from enjoying the love and support of family, friends, or clergy.

Most people grieving the death of a loved one do not develop a major depressive episode. Nevertheless, DSM-5 makes it clear that grief and major depression may exist “side by side.” Indeed, the death of a loved one is a common “trigger” for a major depressive episode — even as the bereaved person continues to grieve.

The DSM-5 provides the clinician with some important guidelines that help distinguish ordinary grief — which is usually healthy and adaptive — from major depression. For example, the new manual notes that bereaved persons with normal grief often experience a mixture of sadness and more pleasant emotions, as they remember the deceased. Their very understandable anguish and pain are usually experienced in “waves” or “pangs,” rather than continuously, as is usually the case in major depression.

The normally grieving person typically maintains the hope that things will get better. In contrast, the clinically depressed person’s mood is almost uniformly one of gloom, despair, and hopelessness — nearly all day, nearly every day. And, unlike the typical bereaved person, the individual with major depression is usually quite impaired in terms of daily functioning.

And, unlike the typical bereaved person, the individual with major depression is usually quite impaired in terms of daily functioning.

Furthermore, in ordinary grief, the person’s self-esteem usually remains intact. In major depression, feelings of worthlessness and self-loathing are very common. In ambiguous cases, a patient’s history of previous depressive bouts, or a strong family history of mood disorders, may help clinch the diagnosis.

Finally, the DSM-5 acknowledges that the diagnosis of major depression requires the exercise of sound clinical judgment, based on the individual’s history and “cultural norms” — thus recognizing that different cultures and religions express grief in different ways and to varying degrees.

The monk Thomas a Kempis wisely noted that human beings must sometimes endure “proper sorrows of the soul,” which do not belong in the realm of disease. Neither do these sorrows require “treatment” or medication. However, the DSM-5 rightly recognizes that grief does not immunize the bereaved person against the ravages of major depression—a potentially lethal yet highly treatable disorder.

Acknowledgment: Thanks to my colleague, Dr. Sidney Zisook, for helpful comments on this piece.

Further Reading

Pies R. Bereavement does not immunize the grieving person against major depression.

Zisook S, Corruble E, Duan N, et al: The bereavement exclusion and DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:425-443.

Pies R. The Two Worlds of Grief and Depression.

Pies R. The anatomy of sorrow: a spiritual, phenomenological, and neurological perspective. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2008; 3: 17. Accessed at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2442112/

Begley S. Psychiatrists unveil their long-awaited diagnostic ‘bible’

Grief

An example of the clinical dynamics of an adaptive disorder is the grief following the death of a significant person. According to statistics, after the death of a person, morbidity and mortality among his close relatives sharply increase (from 40% and above). The reaction to this event is either uncomplicated grief or grief within adjustment disorders.

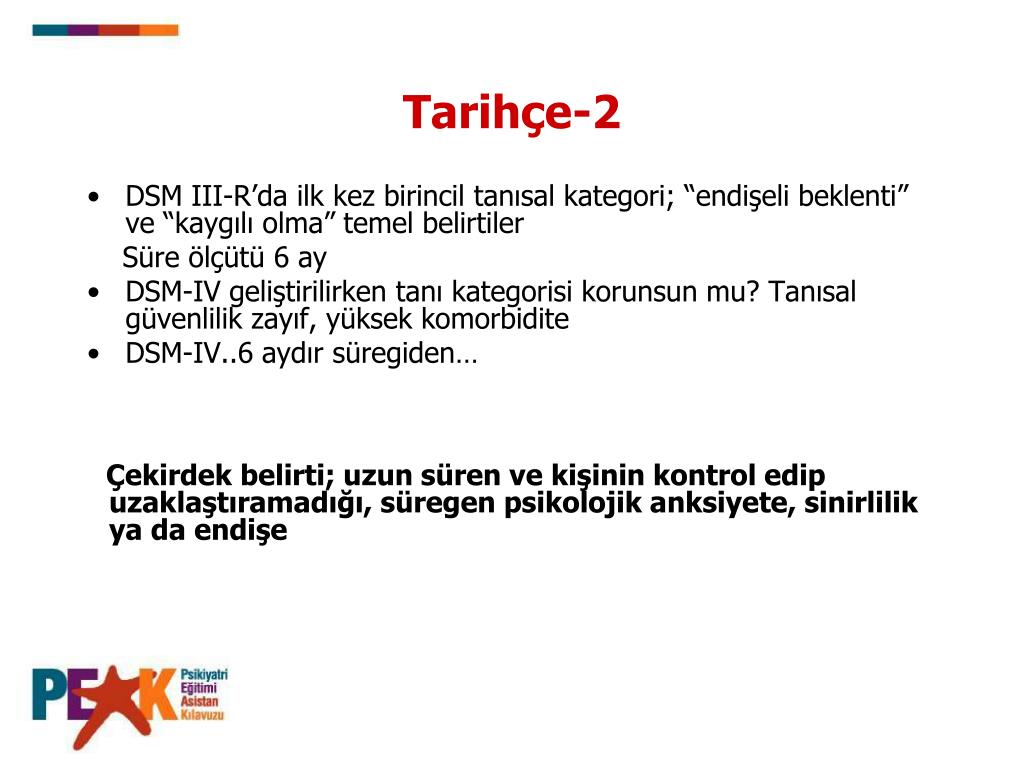

In the DSM-3-R classification, V-codes are specifically allocated for conditions that are not related to mental disorders, but may be the subject of attention and treatment of psychiatrists, psychotherapists and psychologists. This group of disorders includes the uncomplicated bereavement reaction (V–62.82), which is a normal reaction to the death of a loved one. Clinically, it is characterized by depressive experiences, which are accompanied by anorexia, insomnia, weight loss. In an uncomplicated bereavement reaction, guilt may also be present. As a rule, such a reaction to loss corresponds to cultural ideas about the experience of grief. Patients rarely seek professional help, and when they come for a consultation, it is mainly for insomnia and anorexia.

An uncomplicated bereavement reaction may occur acutely or be prolonged (after two to three months). Some authors also describe “ sadness of foresight ” - the development of a grief reaction already at the stage of receiving news of a fatal illness of a loved one. The duration of an uncomplicated bereavement reaction is largely determined by the patient's personal characteristics, his environment, and sociocultural traditions. It is very important to take into account the ethnocultural specificity of response to stressful situations. Thus, the death of a loved one is accompanied by autistic and depressive reactions in the population of the Slavic peoples and Armenians and defiantly expressive in the Tajiks (A.I. Kuchinov, 1995).

The duration of an uncomplicated bereavement reaction is largely determined by the patient's personal characteristics, his environment, and sociocultural traditions. It is very important to take into account the ethnocultural specificity of response to stressful situations. Thus, the death of a loved one is accompanied by autistic and depressive reactions in the population of the Slavic peoples and Armenians and defiantly expressive in the Tajiks (A.I. Kuchinov, 1995).

The reaction of grief within adjustment disorders is a clinically manifested mental disorder leading to maladaptation. There are 8 stages of grief reaction , which were isolated and described by A.G. Ambrumova, (1983) and G.V. Starshenbaum (1994). The model was the most typical situation of grief - the death of a loved one.

Stage 1 — with dominant emotional disorganization. As a rule, it lasts from several minutes to several hours and is accompanied by an outbreak of negative feelings - panic, anger, despair. Behavior is dominated by affective disorganization with a temporary weakening of volitional control.

Behavior is dominated by affective disorganization with a temporary weakening of volitional control.

stage 2 - hyperactivity. Duration 2-3 days. During this period, a person is overly active, active, prone to constant talk about the personality and deeds of the deceased. His mental status is dominated by emotional lability with mood swings from dysthymic with a predominance of an anxious component to euphoric. Emotional dullness without fixation on the experience of grief is much less common. At this stage, inadequate actions may take place (leaving home, negative attitude towards relatives, etc.). P. Janet described an example of non-standard behavior of a girl whose mother died: she continued to care for her and behaved as if her mother were alive.

At this stage, it is expedient to have someone close, who knows the deceased, constantly present, who can talk about his virtue and remember his positive deeds and deeds. The bereaved must be encouraged to discuss his feelings and thoughts, and allowed to express his emotions.

Stage 3 - voltages. Its duration is about a week. Mental status is dominated by psychophysical stress, anxiety. Outwardly, patients are constrained, their face is amimic, they are silent. Their condition is periodically interrupted by fussy activity, spasms in the throat or convulsive sighs. Often they get annoyed when trying to distract them or switch their attention to everyday topics.

Psychodynamically oriented psychotherapists interpret the behavior of these persons at stages 2 and 3 as a rejection of the outside world, identification with the deceased and unwillingness to live.

At this stage, crisis counseling is already needed, the purpose of which is to assist in the processing and expression of the affect of grief. The issue of loss is central at this stage. If necessary, the patient is prescribed tranquilizers and sleeping pills.

Stage 4 - stage of the search, which usually takes place in the second week after the loss of a loved one. The mental status is dominated by a dysthymic background of mood, loss of perspective and life meaning. The deceased is perceived by the patient as living: he speaks about him in the present tense, mentally talks with him, sometimes he perceives random passers-by as the deceased. During this period, illusions, hypnogagic and hypnopompic hallucinations are possible. There are two variants of the course of the fourth stage: anxious and oppositional.

The mental status is dominated by a dysthymic background of mood, loss of perspective and life meaning. The deceased is perceived by the patient as living: he speaks about him in the present tense, mentally talks with him, sometimes he perceives random passers-by as the deceased. During this period, illusions, hypnogagic and hypnopompic hallucinations are possible. There are two variants of the course of the fourth stage: anxious and oppositional.

Alarm variant . In these persons, the mental status is dominated by anxiety, tension, concern and exaggeration of the problems that have arisen in connection with the death of a loved one. Many patients are fixated on their health and often find manifestations of the disease from which the deceased died.

Opposition variant . Patients are dominated by irritability, resentment, a sense of hostility and tension towards the attending physicians and relatives. As a rule, such a reaction is noted in persons who are psychologically dependent on the deceased, with a pronounced ambivalent reaction to him during his lifetime: from love to suppressed feelings of hostility and aggressiveness.

GV Starshenbaum (1994) explains the personal meaning of the alarming response option by the search for a lost person as a protector; the oppositional variant is the search for an object of identification with a significant other in order to respond to previously suppressed hostile emotions.

As a rule, it is at this stage that there is a need for a psychiatric consultation and, if necessary, hospitalization. Depending on the dominant psychopathological syndrome in the clinical picture, it is advisable to prescribe benzodiazepine tranquilizers, tricyclic antidepressants, hypnotics. However, psychopharmacotherapy is only a springboard to further long and painstaking psychotherapy. It should not be prescribed for a long time in order to avoid the development of dependence. Already at the first stages of the patient's stay in the hospital, it is necessary to conduct crisis counseling and implement the necessary measures of intensive care. To do this, it is advisable to take the following steps (S. Bloch, 1997):

Bloch, 1997):

- Transfer of responsibility. The patient is offered to temporarily shift the solution of all problems and responsibilities to loved ones.

- Organization of solving urgent problems (care for children, resolving issues of temporary disability of the patient, etc.).

- Removing a patient from a stressful environment. In itself, hospitalization is already a kind of removal, but it justifies itself only if the patient is placed in a specialized crisis hospital, where professional crisis psychotherapy is carried out.

- Decreased levels of arousal and distress. Psychotherapeutic intervention and pharmacotherapy are applied.

- Establishment of trusting relationships.

- The manifestation of care and warmth, the revival of hope.

Stage 5 - despair. This is the period of maximum mental anguish, which develops, as a rule, at 3-6 weeks after the loss of a significant loved one. The mental status of patients is dominated by complaints of insomnia, anxiety and fear, and ideas of self-blame, own low value and guilt are expressed. Patients experience loneliness, helplessness, note the loss of the meaning of life and future prospects. During this period, they are irritable, refuse to communicate with loved ones, often subjecting them to criticism. At the height of the experience, retrosternal pain often occurs, accompanied by severe anxiety and restlessness. Patients tend to hurt themselves, self-harm. In some cases, they ask to give them painful injections, they are ready to participate in various psychological experiments, and they are ready for psycho-correctional work. At this stage, it is necessary to continue psychopharmacological therapy, adequate to the mental status of the patient. Measures of intensive guardianship must be carried out constantly. Psychotherapeutic intervention is paramount at this stage and should be aimed at helping to experience, express and process the affect of grief and address the problem of changes in the patient's life.

Patients experience loneliness, helplessness, note the loss of the meaning of life and future prospects. During this period, they are irritable, refuse to communicate with loved ones, often subjecting them to criticism. At the height of the experience, retrosternal pain often occurs, accompanied by severe anxiety and restlessness. Patients tend to hurt themselves, self-harm. In some cases, they ask to give them painful injections, they are ready to participate in various psychological experiments, and they are ready for psycho-correctional work. At this stage, it is necessary to continue psychopharmacological therapy, adequate to the mental status of the patient. Measures of intensive guardianship must be carried out constantly. Psychotherapeutic intervention is paramount at this stage and should be aimed at helping to experience, express and process the affect of grief and address the problem of changes in the patient's life.

Stage 6 - with elements of demobilization. This stage occurs in case of failure to resolve the stage of despair. The clinical picture of these individuals is dominated by neurotic syndromes (most often neurasthenic and with a predominance of vegeto-somatic disorders), masked subdepressions and depressions. During this period, patients, as a rule, are uncommunicative, focused on inner experiences, they are overcome by a feeling of hopelessness, uselessness, and loneliness. They avoid contact with others, formally talk with medical personnel, and refuse psychotherapeutic assistance.

This stage occurs in case of failure to resolve the stage of despair. The clinical picture of these individuals is dominated by neurotic syndromes (most often neurasthenic and with a predominance of vegeto-somatic disorders), masked subdepressions and depressions. During this period, patients, as a rule, are uncommunicative, focused on inner experiences, they are overcome by a feeling of hopelessness, uselessness, and loneliness. They avoid contact with others, formally talk with medical personnel, and refuse psychotherapeutic assistance.

Stage 7 - permission. As a rule, its duration is limited to several weeks. The patient comes to terms with what happened, comes to terms with it and begins to return to the pre-crisis state. Thoughts of loss “ lives in the heart of ”. A.S. Pushkin described this state as “ My sadness is bright ”.

Tranquilizer therapy may be discontinued at this stage. With chronic anxiety disorders and unreduced depressive disorders, it is advisable to continue treatment with antidepressants.

Stage 8 - recurrent. Within 1 year, attacks of grief and despair are possible, accompanied by depressive disorders. Provoking factors, as a rule, are certain calendar dates that are significant for the individual (birthday of the deceased, New Year and other holidays celebrated for the first time without a loved one, etc.), non-standard situations (success or failure), when there is a need to share joy or grief with a loved one. Attacks of grief can occur acutely, against the background of a seeming stabilization of the state, and can end in suicidal attempts, which are regarded by others as inadequate.

In connection with the described patterns of the course of the grief reaction, it is advisable to carry out supportive psychotherapy during the year. The most promising at this stage is the conduct of supportive psychotherapy in post-crisis groups, working on the principle of a club for people who have survived a crisis situation. It is advisable to conduct family psychotherapy with the participation of family members and close people.

Concluding the article, it should be said that the clinically formed reactions and conditions that have arisen as a result of crisis situations are so multifaceted that sometimes they can hardly be classified and squeezed into the Procrustean bed of the classification of mental and behavioral disorders. The types of crisis coping behavior are also multivariate and range from regressive (most often alcohol-dependent) behavior to heroic.01-1980) - one of the outstanding psychotherapists of the outgoing century, whose students considered themselves to be the psychotherapists who created the "Ericksonian hypnosis school", and the authors of works on neurolinguistic programming.

DSM-5 protracted grief disorder. The Big Book of Psychological Crises [3-103 Years Assistance Program]

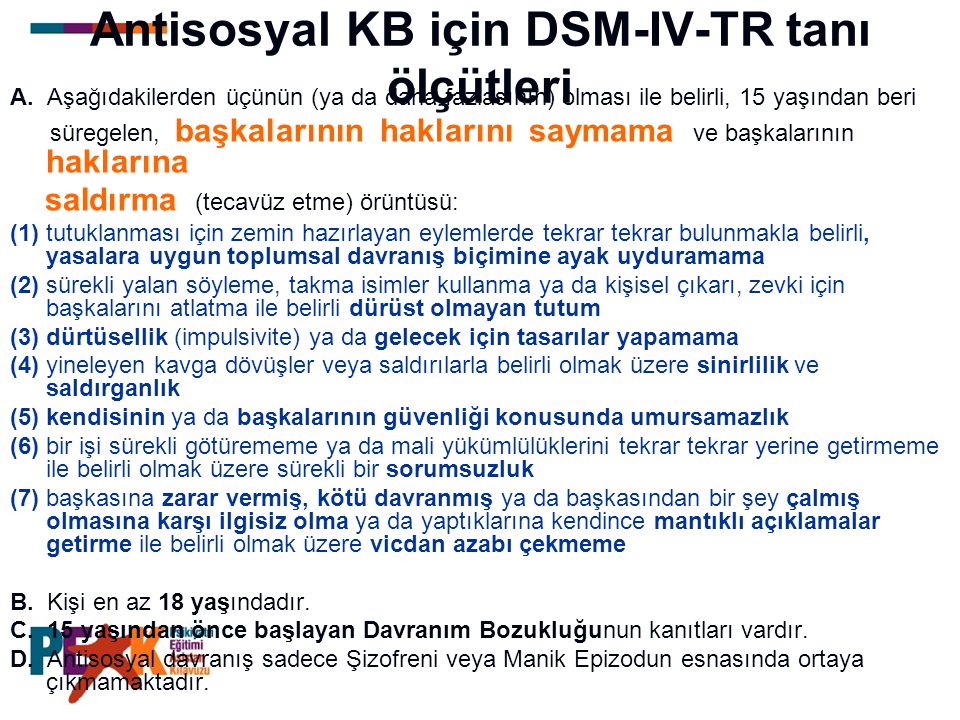

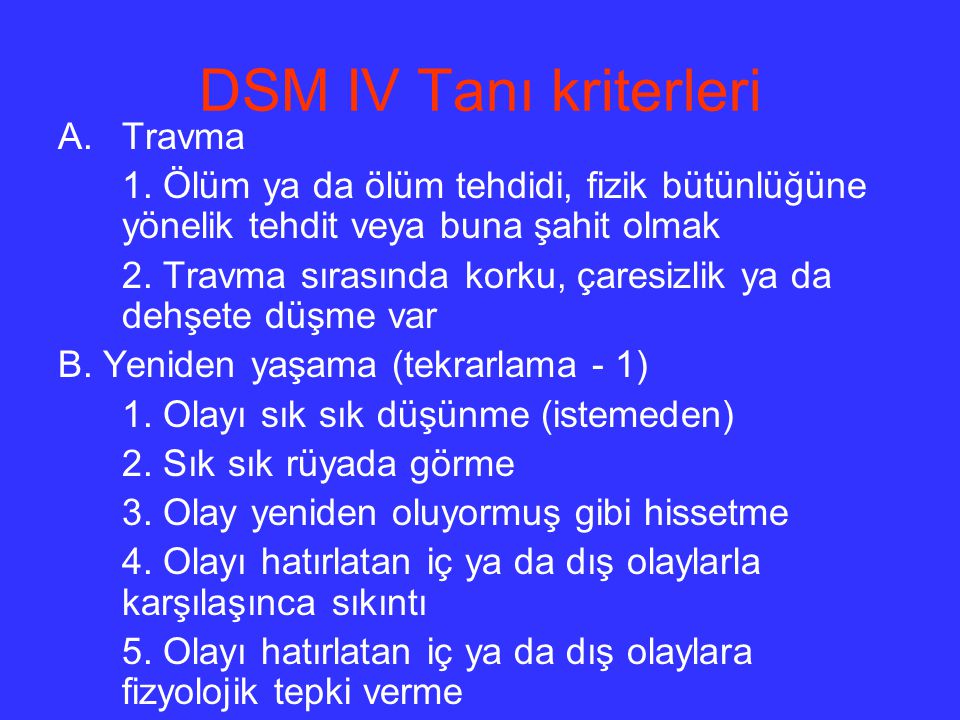

A. The person has experienced the death of someone with whom he had a close relationship.

B. From the time of death, at least one of the following symptoms occurs for several days, but not to a clinically significant extent, and persists for at least 12 months after death in case of mourning in adults, and 6 months for children who have lost loved ones:

1) persistent sadness or longing for the deceased. In young children, longing may be expressed in play and behavior, including behavior that reflects separation and reunion with a caregiver or other attachment figure;

In young children, longing may be expressed in play and behavior, including behavior that reflects separation and reunion with a caregiver or other attachment figure;

2) intense sadness and emotional pain in response to death;

3) coverage of the deceased;

4) covered by the circumstances of death. In children, this preoccupation with the deceased can be expressed through themes of play and behavior, and can extend to a concern about the possible death of those close to them.

B. At least six of the following symptoms have been present for several days since death, but not to a clinically significant extent, and persist for at least 12 months after death in bereaved adults and 6 months in children who have lost loved ones.

Reactive distress due to death

1. Noticeable difficulty in accepting death. In children, it depends on the child's ability to understand the meaning and irreversibility of death.

2. Disbelief in the death of a loved one or emotional numbness due to loss.

3. Difficulty with positive recollection of the deceased.

4. Bitterness or anger at loss.

5. Non-adaptive assessments of oneself in relation to the deceased or death (for example, self-blame).

6. Excessive avoidance of reminders of the loss (eg, avoidance of persons, places, or situations associated with the deceased; in children, this may include avoiding thoughts and feelings about the deceased).

Social and personality disorders

7. Desire to die in order to be with the deceased.

8. Difficulty trusting others after loss.

9. Feeling alone or withdrawn from other people after loss.

10. Feeling that life is meaningless or empty without the deceased, or the conviction that one cannot live without him.

11. Confusion about one's role in life or weakening of the sense of identity (for example, feeling that a part of oneself died with the deceased).

12. Difficulty or unwillingness to satisfy former interests after loss or to plan for the future (eg, friendship, activities).

D. The impairment causes a clinically significant impairment or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

E. Reaction to loss does not conform to cultural, religious or age norms.

Similar conditions. Protracted grief reaction other than normal grief having a severe grief reaction that interferes with the person's ability to function for at least 12 months (or 6 months in children) after the death of the deceased. It is often important to consider whether other people who share the cultural or religious perspective of the grieving person (eg, family, friends, communities) view the response to the loss or the duration of the response as abnormal.

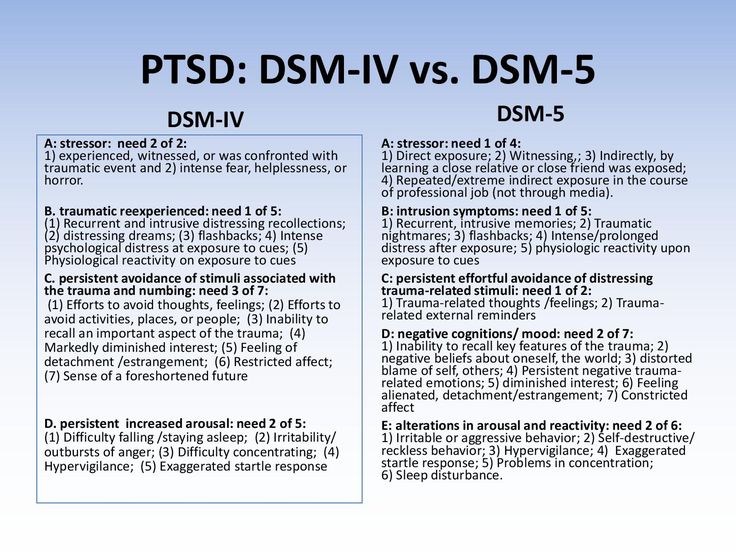

Unlike PTSD the grieving person does not experience the traumatic events over and over again as being here and now. Intrusive memories in lingering grief include not only the stress of the loss, but also the positive aspects of the relationship.

Intrusive memories in lingering grief include not only the stress of the loss, but also the positive aspects of the relationship.

separation anxiety disorder is characterized by anxiety about separation from living figures of attachment, while lingering grief is associated with stress due to separation from a deceased person.

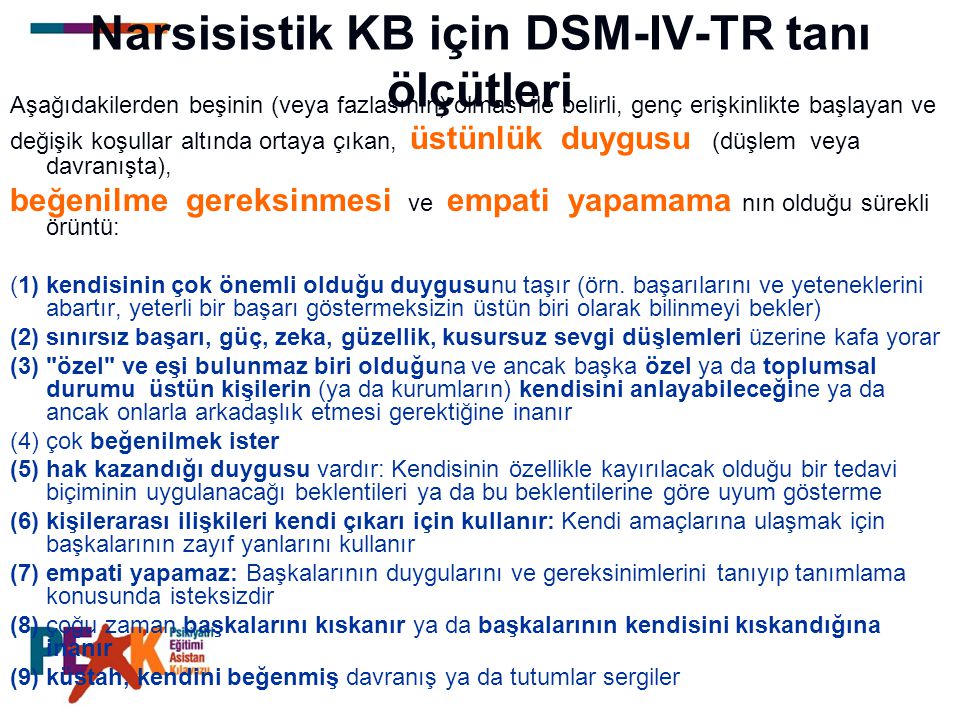

Protracted grief differs from depressive episode in that the symptoms specifically focus on the loss of a loved one, while depressive thoughts and emotional reactions usually cover many areas of life. In addition, other common symptoms of protracted grief disorder (eg, difficulty with the loss, feeling angry at the loss, feeling as if part of the individual has died) are not characteristic of a depressive episode.

In grief, in contrast to a major depressive episode, feelings of emptiness and loss are the dominant affect rather than a permanently depressed mood and inability to experience joy or pleasure. Negative affectivity in grief decreases in intensity over several days or weeks and occurs in waves, the so-called pangs of grief. These waves are usually associated with thoughts or reminders of the deceased. Depressed mood in depression is more persistent and not tied to specific thoughts or concerns.

Negative affectivity in grief decreases in intensity over several days or weeks and occurs in waves, the so-called pangs of grief. These waves are usually associated with thoughts or reminders of the deceased. Depressed mood in depression is more persistent and not tied to specific thoughts or concerns.

The pain of grief can be accompanied by positive emotions and humor, which are not characteristic of experiencing the total misery and suffering characteristic of depression. The thought content associated with sadness is generally characterized by a preoccupation with thoughts and memories of the deceased, rather than the self-critical or pessimistic ruminations seen in depression.

In grief, self-esteem is generally preserved, while in depression there are feelings of worthlessness and self-hatred. If self-deprecating ideas are present in grief, they usually include perceived shortcomings towards the deceased (eg, not visiting often enough, not telling the deceased how much you loved him). A person who has lost loved ones thinks about death, such thoughts are usually focused on the deceased and, possibly, about "reunion" with the deceased. In depression, such thoughts are focused on ending one's own life due to the idea of oneself as a worthless person, unworthy of life, or unable to cope with the pain of depression.

A person who has lost loved ones thinks about death, such thoughts are usually focused on the deceased and, possibly, about "reunion" with the deceased. In depression, such thoughts are focused on ending one's own life due to the idea of oneself as a worthless person, unworthy of life, or unable to cope with the pain of depression.

Relatives of suicidal people and doctors who treated them often develop suicidal post-traumatic stress disorder. The frequency of suicides among close suicides according to some data is three times higher than the average figures. The first wave of emotions in response to suicide includes shock, denial, helplessness, and blame. Then comes the feeling of anger at the suicide, accompanied by feelings of abandonment and guilt. There are also self-accusations about one's own responsibility for his act. There may be relief that the annoying urgent need for the care of a loved one has disappeared.

During the second wave of emotions, loved ones experience shame in front of others and fear of experiencing something similar again - for example, surviving the suicide of children in the future.

During the third wave of emotions, relatives of suicides often experience depression with a decrease in self-esteem.

The fourth wave of emotions includes a wide range of psychological and psychosomatic problems, including suicidal tendencies.

The doctor of a patient who has committed suicide often experiences the following feelings.

1. Intense sense of loss - experience of grief and grief.

2. Anger - because of the need to feel responsible for what happened.

3. Feeling of separation - due to the fact that the offered help was rejected.

4. Feelings of anxiety, guilt, shame or embarrassment.

5. Relief that the annoyingly urgent need to care for or control loved ones has disappeared.

6. Feeling abandoned.

7. Emergence of own self-destructive tendencies.

8. Anger generated by prevailing prejudices that what happened is a disregard for the norms of social and moral responsibility.