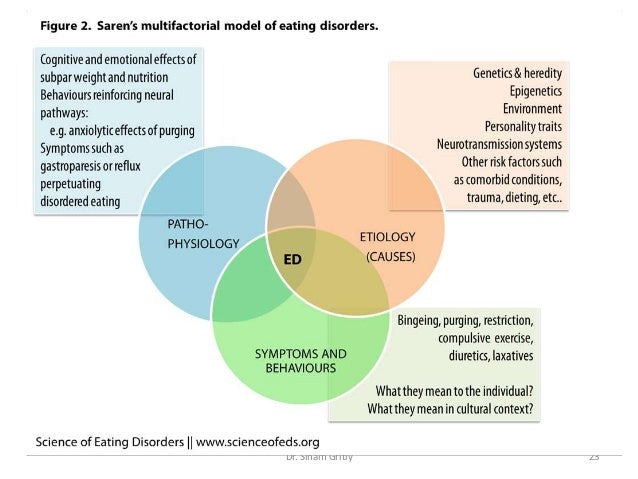

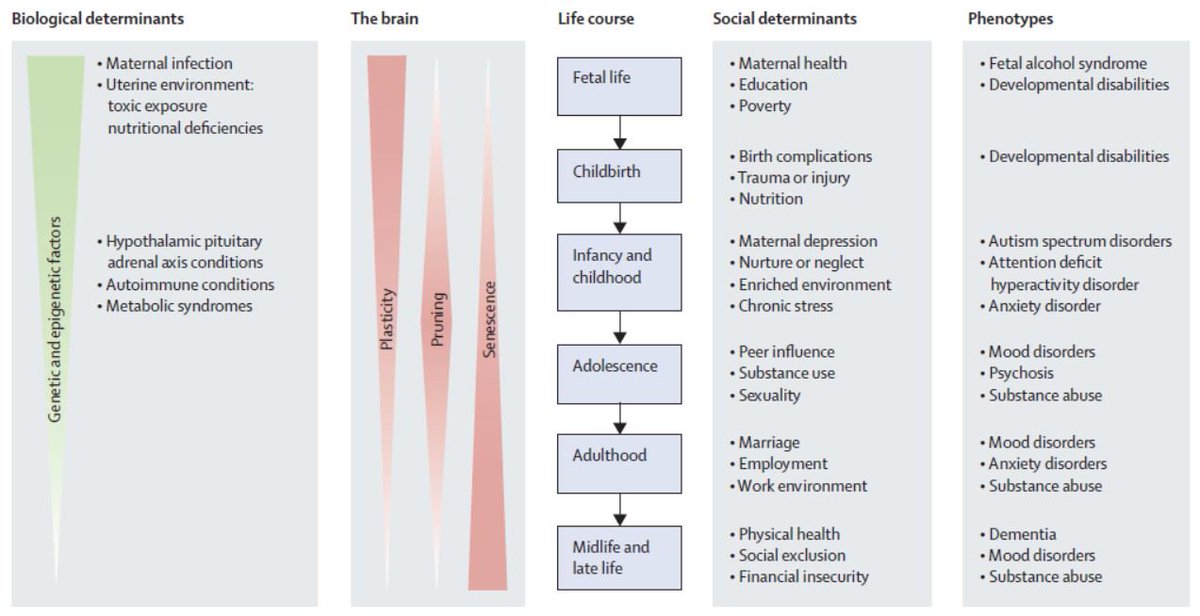

Genetic influences on eating disorders most likely involve

The Genetics of Eating Disorders

1. Bulik C, Sullivan P, Carter F, Joyce P. Initial manifestation of disordered eating behavior: dieting versus binging. Int J Eating Disord. 1997;22:195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Mussell M, Mitchell J, Fenna C, et al. A comparison of onset of binge eating versus dieting in the development of bulimia nervosa. Int J Eating Disord. 1997;21:353–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Bulik C, Sullivan PF, Fear J, Pickering A. Predictors of the development of bulimia nervosa in women with anorexia nervosa. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:704–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Eckert ED, Halmi KA, Marchi P, et al. Ten-year follow-up of anorexia nervosa: Clinical course and outcome. Psychol Med. 1995;25(1):143–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Garfinkel PE, Moldofsky H, Garner DM. The heterogeneity of anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37:1036–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W. The long-term course of severe anorexia nervosa in adolescents: Survival analysis of recovery, relapse, and outcome predictors over 10 to 15 years in a prospective study. Int J Eating Disord. 1997;22(4):339–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Fear JL, Pickering A. The outcome of anorexia nervosa: Eating attitudes, personality, and parental bonding. Int J Eating Disord. 2000;28(2):139–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Fornari V, Kaplan M, Sandberg DE, et al. Depressive and anxiety disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Int J Eating Disord. 1992;12:21–9. [Google Scholar]

9. Mitchell JE, Hatsukami D, Pyle RL, Eckert ED. The bulimia syndrome: Course of illness and associated problems. Compr Psychiatry. 1986;27:165–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Keck PE, Pope, HG, Hudson JL, et al. A controlled study of phenomenology and family history in outpatients with bulimia nervosa. Compr Psychiatry. 1990;31:275–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Garner DM. Pathogenesis of anorexia nervosa. Lancet. 1993;341:1631–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Treasure J, Campbell I. The case for biology in the aetiology of anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med. 1994;24:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychol Med. 1994;24:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

14. Becker A. Eating disorders in Fiji. Presented at the American Psychiatric Association meeting. Washington, DC: 1999.

15. Biederman J, Rivinus T, Kemper K, et al. Depressive disorders in relatives of anorexia nervosa patients with and without a current episode of nonbipolar major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:1495–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Lilenfeld LR, Kaye WH, Greeno CG, et al. A controlled family study of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: Psychiatric disorders in first-degree relatives and effects of proband comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:603–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Strober M, Freeman R, Lampert C, et al. Controlled family study of anorexia and bulimia nervosa: Evidence of shared liability and transmission of partial syndromes. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(3):393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(3):393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Strober M, Lampert C, Morrell W, et al. A controlled family study of anorexia nervosa: Evidence of familial aggregation and lack of shared transmission with affective disorders. Int J Eating Disord. 1990;9:239–53. [Google Scholar]

19. Fichter MM, Noegel R. Concordance for bulimia nervosa in twins. Int J Eating Disord. 1990;9:255–63. [Google Scholar]

20. Holland AJ, Hall A, Murray R, et al. Anorexia nervosa: A study of 34 twin pairs. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;145:414–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Holland AJ, Sicotte N, Treasure J. Anorexia nervosa: Evidence for a genetic basis. J Psychosom Res. 1988;32:561–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Treasure J, Holland A. Genetic vulnerability to eating disorders: Evidence from twin and family studies. In: Remschmidt H, Schmidt MH, editors. Child and Youth Psychiatry: European Perspectives. Lewiston, NY: Hogrefe & Huber; 1990. [Google Scholar]

23. Klump KL, Miller KB, Keel PK, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on anorexia nervosa syndromes in a population-based twin sample. Psychol Med. 2001;31(4):737–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Klump KL, Miller KB, Keel PK, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on anorexia nervosa syndromes in a population-based twin sample. Psychol Med. 2001;31(4):737–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Wade TD, Bulik CM, Neale M, Kendler KS. Anorexia nervosa and major depression: An examination of shared genetic and environmental risk factors. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:469–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Kendler KS. Heritability of binge-eating and broadly-defined bulimia nervosa. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:1210–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Kendler KS, MacLean C, Neale MC, et al. The genetic epidemiology of bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1627–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Bulik C, Sullivan P, Wade T, Kendler K. Twin studies of eating disorders: A review. Int J Eating Disord. 2000;27:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Klump KL, Bulik CM, Pollice C, et al. Temperament and character in women with anorexia nervosa. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188(9):559–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2000;188(9):559–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Sullivan PF, Bulik CM, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of binging and vomiting. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:75–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Rutherford J, McGuffin P, Katz RJ, Murray RM. Genetic influences on eating attitudes in a normal female twin pair population. Psychol Med. 1993;23:425–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Wade T, Martin NG, Tiggeman M. Genetic and environmental risk factors for the weight and shape concerns characteristic of bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med. 1998;28:761–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Wade T, Martin NG, Neale MC, et al. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for three measures of disordered eating. Psychol Med. 1999;29(4):925–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Age differences in genetic and environmental influences on eating attitudes and behaviors in preadolescent and adolescent twins. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109(2):239–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Genetic relationships between personality and disordered eating. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(2):380–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Genetic relationships between personality and disordered eating. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(2):380–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Differential heritability of eating attitudes and behaviors in pre-pubertal and pubertal twins. (Submitted) [PubMed]

36. Neale M, Kendler K. Models of comorbidity for multifactorial disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:935–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Holderness CC, Brooks-Gunn J, Warren WP. Co-morbidity of eating disorders and substance abuse: Review of the literature. Int J Eating Disord. 1994;16:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Kaye WH, Lilenfeld LR, Plotnikov K, et al. Bulimia nervosa and substance dependence: association and family transmission. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:878–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Miller KB, Klump KL, Keel PK, et al. A population-based twin study of anorexia and bulimia nervosa: Heritability and shared transmission with anxiety disorders. Paper presented at the Eating Disorder Research Society Meeting. Boston, MA, 1998.

Paper presented at the Eating Disorder Research Society Meeting. Boston, MA, 1998.

40. Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Anthenall RM, et al. Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in alcohol-dependent men and women and their relatives. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:74–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Kendler KS, Walters EE, Neale MC, et al. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for six major psychiatric disorders in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:374–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Walters EE, Neale MC, Eaves LJ, et al. Bulimia nervosa and major depression: a study of common genetic and environmental factors. Psychol Med. 1992;22:617–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Brewerton TD, Hand LD, Bishop ER. The Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire in eating disorder patients. Int J Eating Disord. 1993;14(2):213–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Weltzin TE, Kaye WH. Temperament in eating disorders. Int J Eating Disord. 1995;17(3):251–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Casper RC. Personality features of women with good outcome from restricting anorexia nervosa. Psychosom Med. 1990;52(2):156–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Kleifield EI, Sunday S, Hurt S, Halmi KA. The tridimensional personality questionnaire: An exploration of personality traits in eating disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28(5):413–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Kleifield EI, Sunday S, Hurt S, Halmi KA. The effects of depression and treatment on the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire. Biolog Psychiatry. 1994;36:68–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Klump KL, Kaye WH, Plotnicov K, et al. Familial transmission of personality traits in women with anorexia nervosa and their first-degree relatives. Poster presented at the Academy for Eating Disorders Annual Meeting. San Diego, California, 1999.

49. O'Dwyer AM, Lucey JV, Russell GFM. Serotonin activity in anorexia nervosa after long-term weight restoration: Response to d-fenfluramine challenge. Psychol Med. 1996;26(2):353–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychol Med. 1996;26(2):353–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Tellegen A, Lykken DT, Bouchard TJ, et al. Personality similarity in twins reared apart and together. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1031–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Lilenfeld LRR, Stein D, Bulik CM, et al. Personality traits among currently eating disordered, recovered and never ill first-degree female of bulimic and control women. Psychol Med. 2000;30:1399–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Carney CP, Yates WR, Cizadlo B. A controlled family study of personality in normal-weight bulimia nervosa. Int J Eating Disord. 1990;9(6):659–65. [Google Scholar]

53. Fairburn CG, Welch SL, Doll HA, et al. Risk factors for bulimia nervosa: A community-based case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:509–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Stunkard AJ, Harris JR, Pedersen NL, McClearn GE. The body-mass index of twins who have been reared apart. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1483–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Walters EE, Kendler KS. Anorexia nervosa and anorexic-like syndromes in a population-based female twin sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:64–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Walters EE, Kendler KS. Anorexia nervosa and anorexic-like syndromes in a population-based female twin sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:64–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Lander ES, Schork NJ. Genetic dissection of complex traits. Science. 1994;265(5181):2037–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Martin N, Boomsma D, Machin G. A twin-pronged attack on complex traits. Nat Genet. 1997;17:387–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Risch N, Merikangas K. The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science. 1996;273:1516–17. Erratum 1997;1275:1329–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Sham P. Statistics in Human Genetics. London, England: Arnold; 1998. [Google Scholar]

60. Allison DB, Heo M, Schork NJ, et al. Extreme selection strategies in gene mapping studies of oligogenic quantitative traits do not always increase power. Hum Hered. 1998;48(2):97–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Risch N, Zhang H. Mapping quantitative trait loci with extreme discordant sib pairs: sampling considerations. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:836–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:836–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Roberts SB, MacLean CJ, Neale MC, et al. Replication of linkage studies of complex traits: an examination of variation in location estimates. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65(3):876–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Kidd KK. Associations of disease with genetic markers: Deja vu all over again. Am J Med Genet. 1993;48(2):71–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Gorwood P, Bouvard M, Mouren-Simeoni MC, et al. Genetics and anorexia nervosa: a review of candidate genes. Psychiatr Genet. 1998;8:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Collier DA, Arranz MJ, Li T, et al. Association between 5-HT2A gene promoter polymorphism and anorexia nervosa. Lancet. 1997;350:412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Enoch MA, Kaye WH, Rotondo A, et al. 5-HT2A promoter polymorphism -1438G/A, anorexia nervosa, an obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet. 1998;351:1785–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Nacmias B, Ricca V, Tedde A, et al. 5-HT2A receptor gene polymorphisms in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Neurosci Lett. 1999;277(2):134–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nacmias B, Ricca V, Tedde A, et al. 5-HT2A receptor gene polymorphisms in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Neurosci Lett. 1999;277(2):134–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Sorbi S, Nacmias B, Tedde A, et al. 5-HT2A promoter polymorphis in anorexia nervosa. Lancet. 1998;351:1785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Campbell DA, Sundaramurthy D, Gordon D, et al. Lack of association between 5-HT2A gene promoter polymorphism and susceptibility to anorexia nervosa. Lancet. 1998;351:499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Han L, Nielson DA, Rosenthal NE, et al. No coding variant of the tryptophan hydroxylase gene detected in seasonal affective disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anorexia nervosa, and alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45(5):615–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Hinney A, Barth N, Ziegler A, et al. Serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphic region: allele distributions in relationship to body weight and in anorexia nervosa. Life Sci. 1997;61(21):295–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Hinney A, Herrmann H, Lohr T, et al. No evidence for involvement of alleles of polymorphisms in the serotonin 1Dbeta and 7 receptor genes in obesity, underweight or anorexia nervosa. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(7):760–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hinney A, Herrmann H, Lohr T, et al. No evidence for involvement of alleles of polymorphisms in the serotonin 1Dbeta and 7 receptor genes in obesity, underweight or anorexia nervosa. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(7):760–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Hinney A, Ziegler A, Nothen MM, et al. 5-HT2A receptor gene polymorphisms, anorexia nervosa, and obesity. Lancet. 1997;350:1324–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Ziegler A, Hebebrand J, Gorg T, et al. Futher lack of association between the 5-HT2A gene promoter polymorphism and susceptibility to eating disorders and a meta-analysis pertaining to anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4(5):410–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Burnet PW, Smith KA, Cowen PJ. eet al. Allelic variation of the 5-HT2C receptor (HTR2C) in bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. Psychiatr Genet. 1999;9(2):101–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Bruins-Slot L, Gorwood P, Bouvard M, et al. Lack of association between anorexia nervosa and D3 dopamine receptor gene. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43(1):76–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43(1):76–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Rosenkranz K, Hinney A, Ziegler A, et al. Systematic mutation screening of the estrogen receptor beta gene in probands of different weight extremes: identification of several genetic variants. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 1998;83(12):4524–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Hinney A, Lentes KU, Rosenkranz K, et al. Beta 3-adrenergic-receptor allele distributions in children, adolescents and young adults with obesity, underweight or anorexia nervosa. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21(3):224–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Hinney A, Schmidt A, Nottebom K, et al. Several mutations in the melanocorton-4 receptor gene including a nonsense and a frameshift mutation associated with dominantly inherited obesity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 1999;84(4):1483–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Hinney A, Bornscheuer A, Depenbusch M, et al. No evidence for involvement of the leptin gene in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, underweight or early onset extreme obesity: Identification of two novel mutations in the coding sequence and a novel polymorphism in the leptin gene linked upstream region. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3(6):539–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3(6):539–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Campbell DA, Sundaramurthy D, Gordon D, et al. Association between a marker in the UCP-2/UCP-3 gene cluster and genetic susceptibility to anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4(1):68–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Rosenkranz K, Hinney A, Ziegler A, von-Prittwitz S, et al. Screening for mutations in the neuropeptide Y Y5 receptor gene in cohorts belonging to different weight extremes. Int J Obes Rel Metabol Disord. 1998;22(2):157–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Kaye WH, Lilenfeld LRR, Berrettini WH, et al. A search for susceptibility loci for anorexia nervosa: methods and sample description. Biolog Psychiatry. 2000;47:794–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Grice DE, Berrettini WH, Halmi KA, et al. Genome-wide affected relative pair analysis of anorexia nervosa. 2004; in preparation.

Are Eating Disorders Genetic? How Genes Play a Role

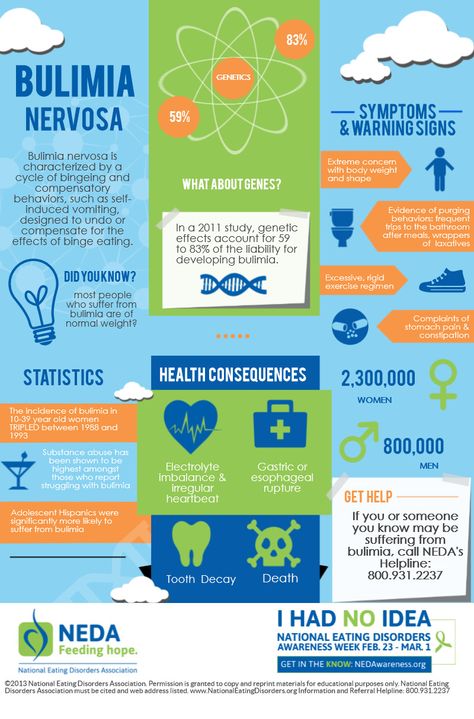

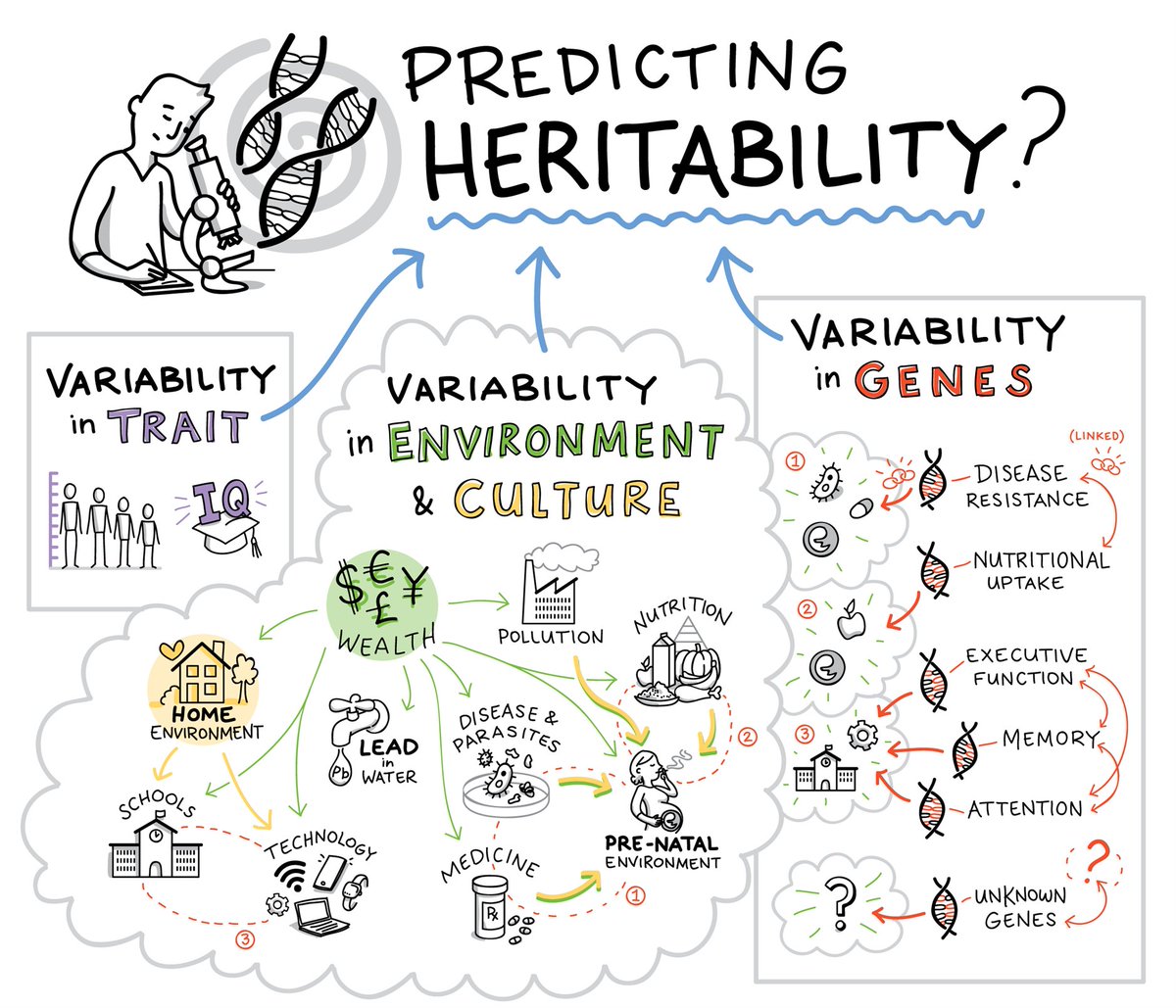

Are eating disorders genetic? Researchers think so—eating disorders can be a result of both genetic and environmental influences.

Several studies suggest that people with anorexia share genetic abnormalities. While similar studies haven’t been conducted on bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, researchers still believe these eating disorders have a genetic component.

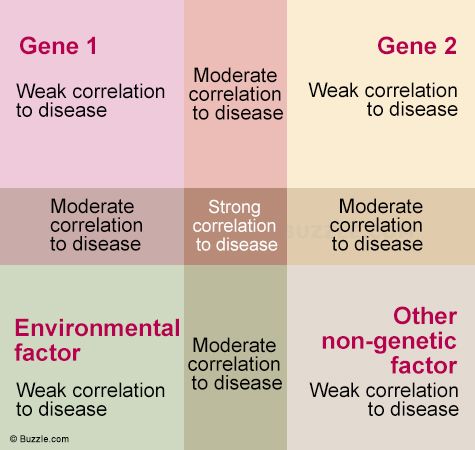

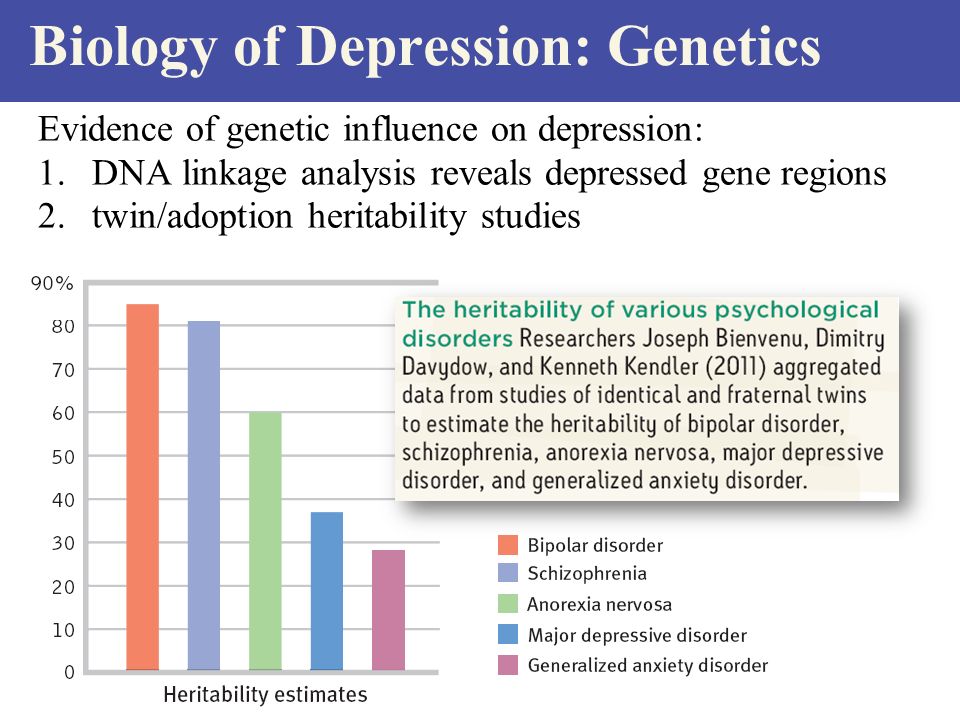

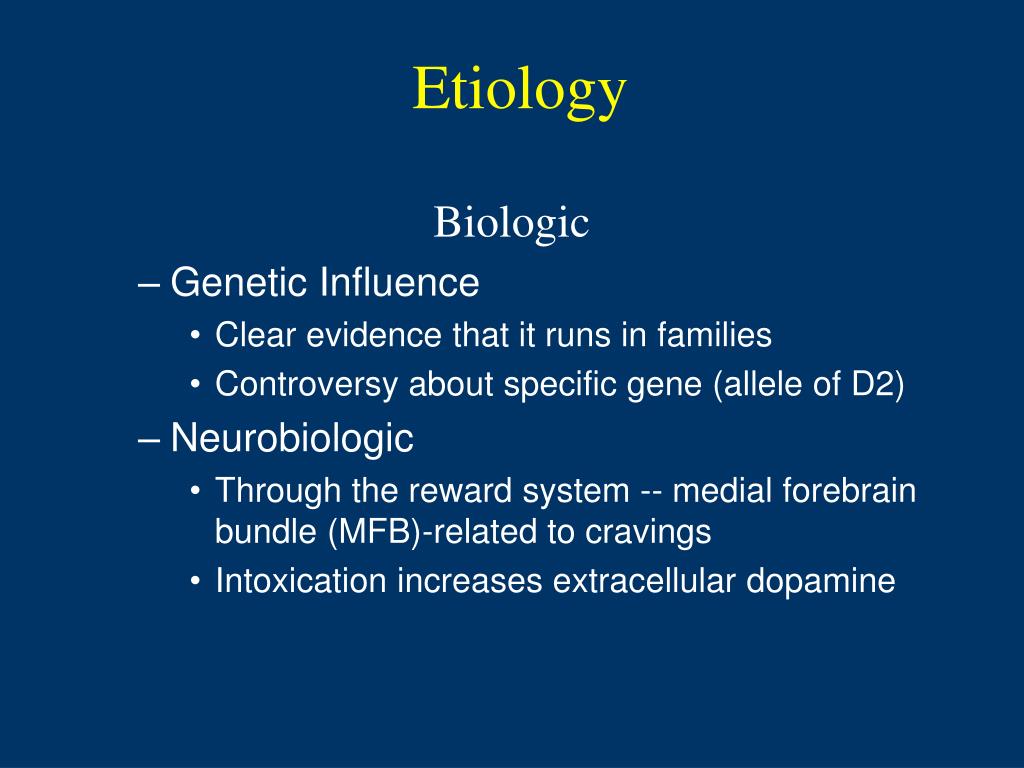

Researchers say that between 40% and 60% of the vulnerability to eating disorders comes from genetic factors. [1] Understanding what those genes are could lead to better treatment options. But conducting all of the necessary research will take time.

In the interim, know that eating disorders can be successfully treated. If you’re struggling with unhealthy eating, talk with your doctor about treatment programs that could help.

Anorexia Nervosa and Genetics

Genetic studies suggest that people with anorexia share a set of genetic abnormalities. Of all the eating disorders, anorexia has been studied most by geneticists. The lessons these researchers have learned could help us understand other eating disorders better.

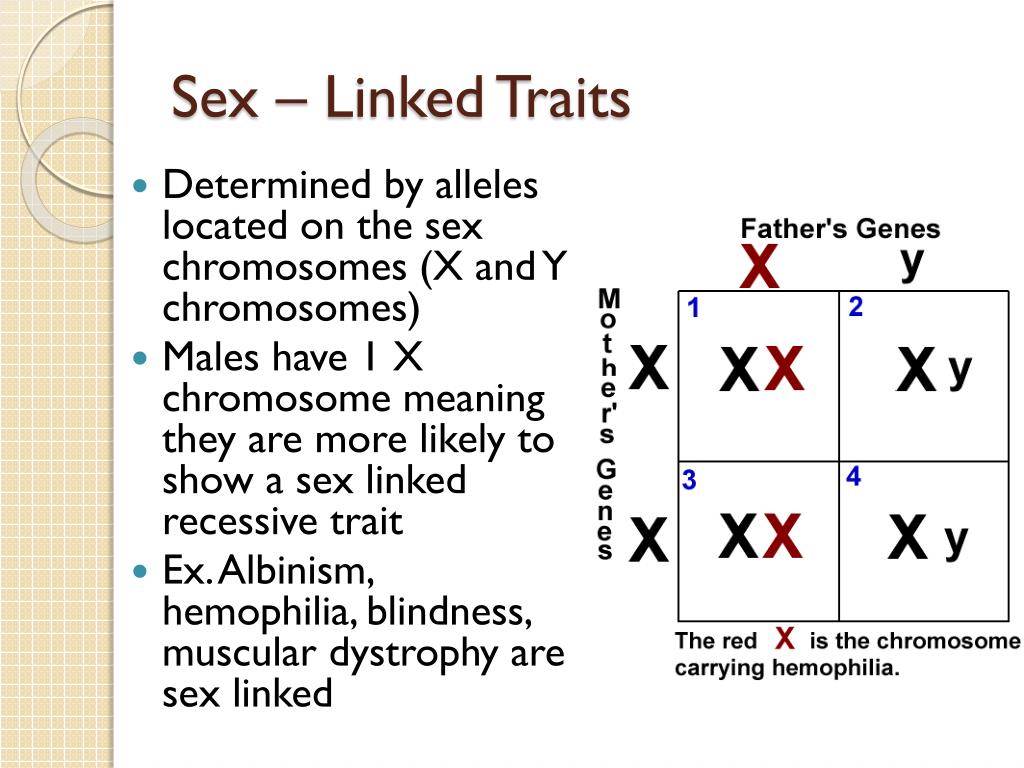

Researchers say anorexia runs in families. People born into a family touched by anorexia are 11 times more likely to develop the condition when compared to others. [2]

People born into a family touched by anorexia are 11 times more likely to develop the condition when compared to others. [2]

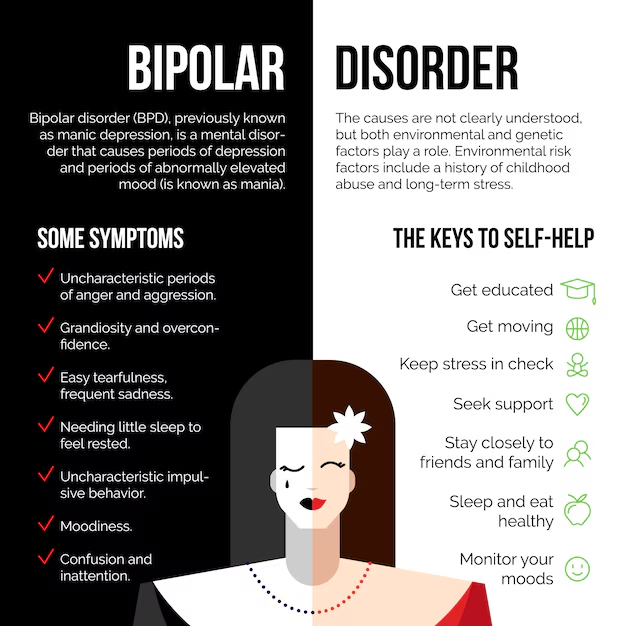

People with anorexia may have abnormalities in genetic factors that regulate the following:

- Cholesterol production

- Body mass index and obesity

- Fasting insulin

- Fasting glucose

As a result, researchers say they consider anorexia a disease with roots in mental health and metabolism. [2]

The genetic roots of anorexia were first discovered in groundbreaking research published in 2003. Here, researchers found three candidate genes involving appetite, anxiety, and depression that were all unusual in people with anorexia. [3] Researchers have built on this study over time, deepening our understanding of how this eating disorder works.

Can Other Eating Disorders Be Genetic?

Genetic studies involving people with bulimia and binge eating disorders are relatively rare. [4] While it’s clear that many people struggle with these forms of disordered eating, researchers just haven’t dug deep into the genetic roots yet. That may change in the future.

That may change in the future.

In a small study, researchers found a shared genetic risk factor in people with binge eating disorder. [5] A study like this suggests that genetic factors contribute to the development of this eating disorder. Still, more work must be done to make the relationship clear and easy to understand.

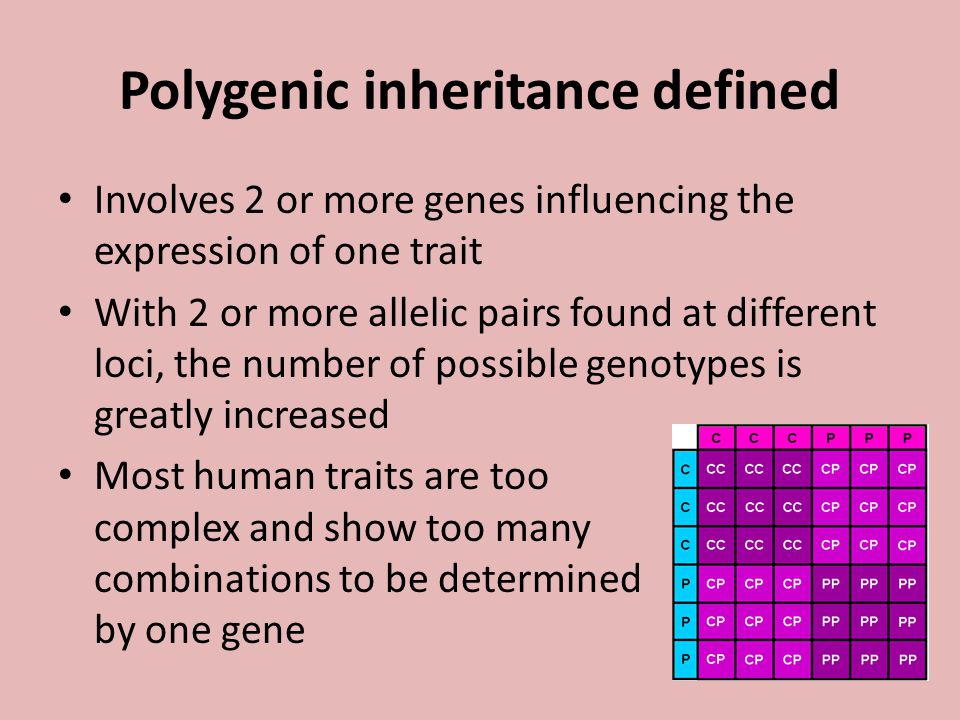

How Genetics Influence Eating Disorders

Some researchers argue that we don’t need to conduct new studies on people with binge eating disorder and bulimia. Instead, they say we can think of all eating disorders as interrelated.

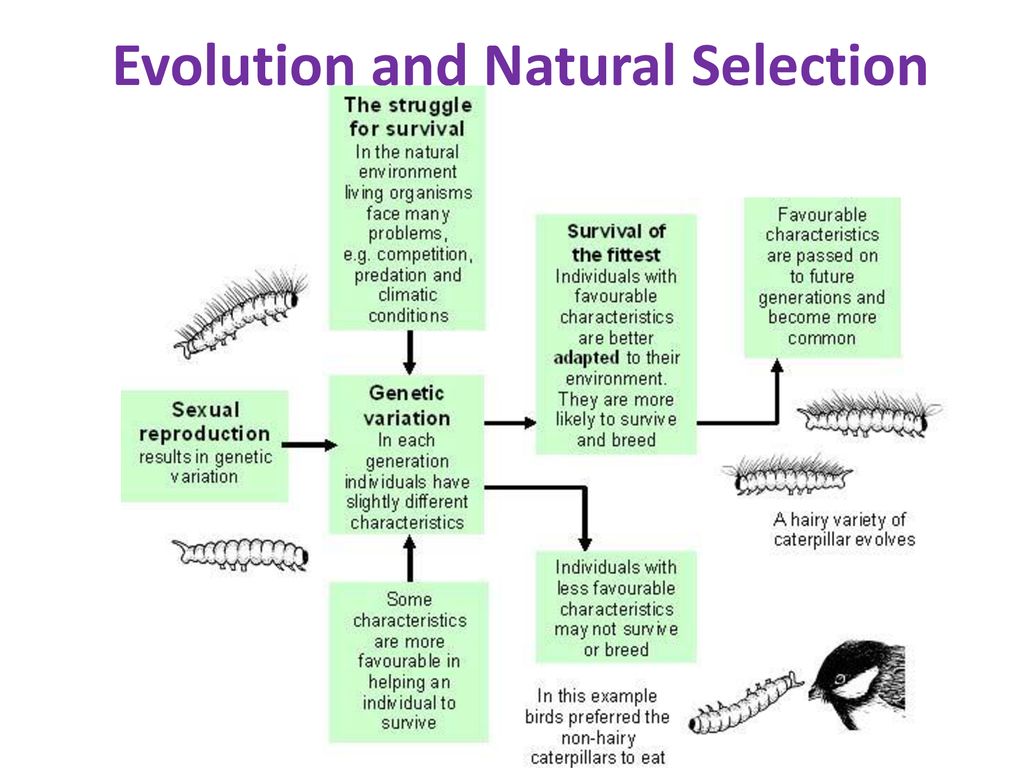

In this model, people with all eating disorders share the same genetic vulnerabilities. But how those genes are expressed accounts for the differences in behavior.

For example, researchers say that mutations in the same gene could cause people to do the following: [6]

- Restrict: Someone with this variant would develop anorexia and limit food intake.

- Indulge: Someone with this variant would binge and develop bulimia or a binge eating disorder.

Genes also don’t work independently, and it’s common for a person’s cells to interact and overlap. As a result, some genetic information is expressed, and other information is suppressed. Researchers say this action could be responsible for the different presentations of eating disorders.

Some people have a genetic predisposition to put on weight, and others are genetically inclined to stay slim. If these genes interact with those involving eating disorders, they could influence whether someone binges or restricts food. [7]

Genes Connected to Personality Traits

Some genes that contribute to eating disorders are associated with specific personality traits. They are believed to be highly heritable and often exist before the onset of the eating disorder. These traits are:

- Obsessive thinking

- Perfectionistic tendencies

- Sensitivity to reward and punishment

- Emotional instability

- Hypersensitivity

- Impulsivity

- Rigidity

Family studies of anorexia and bulimia have found a higher lifetime prevalence of eating disorders among relatives of eating disorders. [8]

[8]

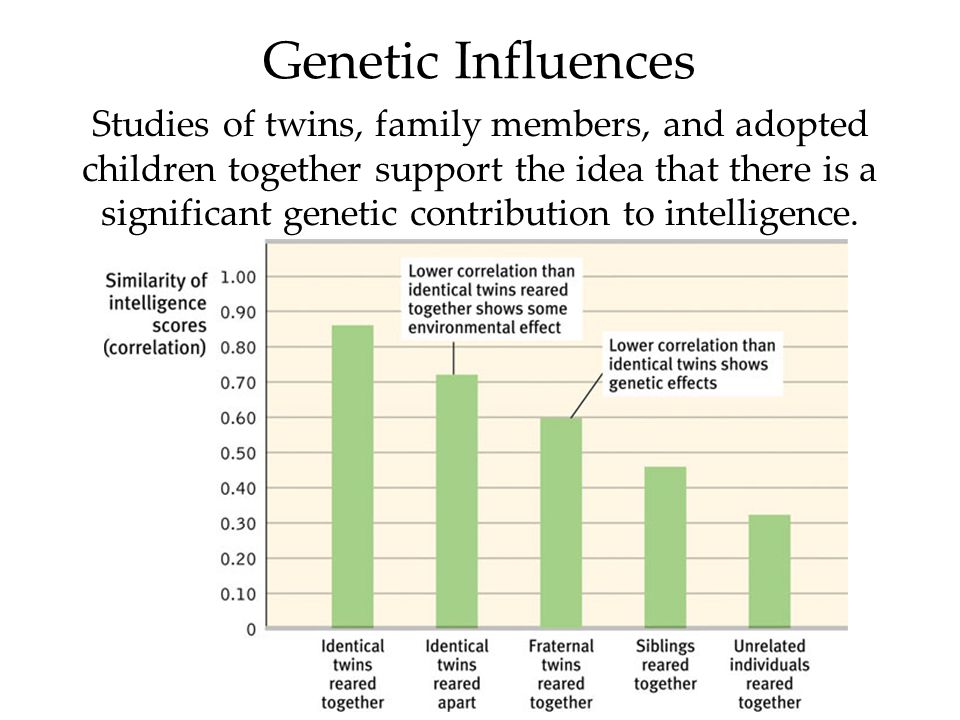

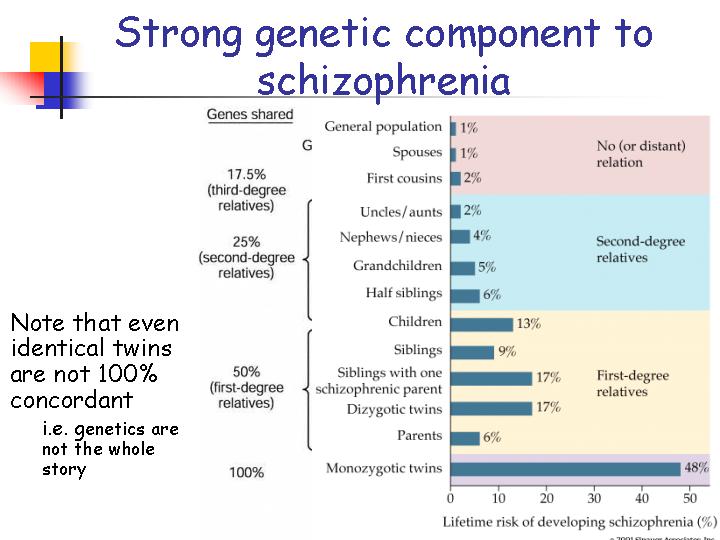

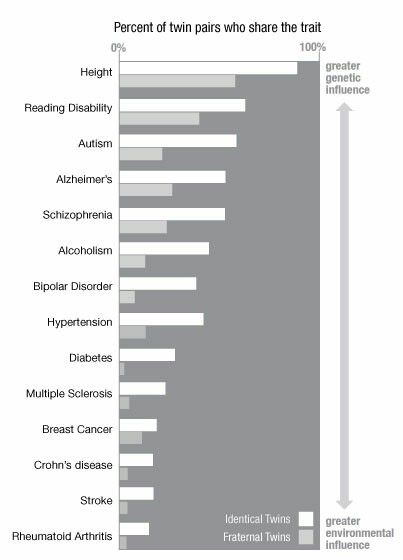

Twin studies also suggest that genetic factors significantly influence both anorexia and bulimia. When looking at the differences between identical and fraternal twins, correlations are two times greater in identical twins with eating disorders.

The Future of Genetic Research

Studies involving eating disorders may seem simply academic. But how important is it to understand the genes underpinning eating disorders? Researchers say their work could have real-time benefits but need more time.

Researchers identified eight specific genetic loci linked to eating disorders in one study. They suggest there are hundreds more. [9] It will take time to tease out connections and determine how genes are expressed in different people.

But when the research is complete, doctors may have more treatment options to help their patients. Molecules targeting specific genetic pathways could help curb harmful eating impulses. [10]

Drugs like this could help people develop healthier eating patterns quickly. But those drugs will take years to develop and test.

But those drugs will take years to develop and test.

Eating Disorders as a Biological Illness

Genetic findings can help researchers, medical providers, therapists, and treatment teams to see eating disorders as biological illnesses where individuals share temperament predispositions. Still, researchers say 30% to 50% of eating disorder risk is due to environmental factors.

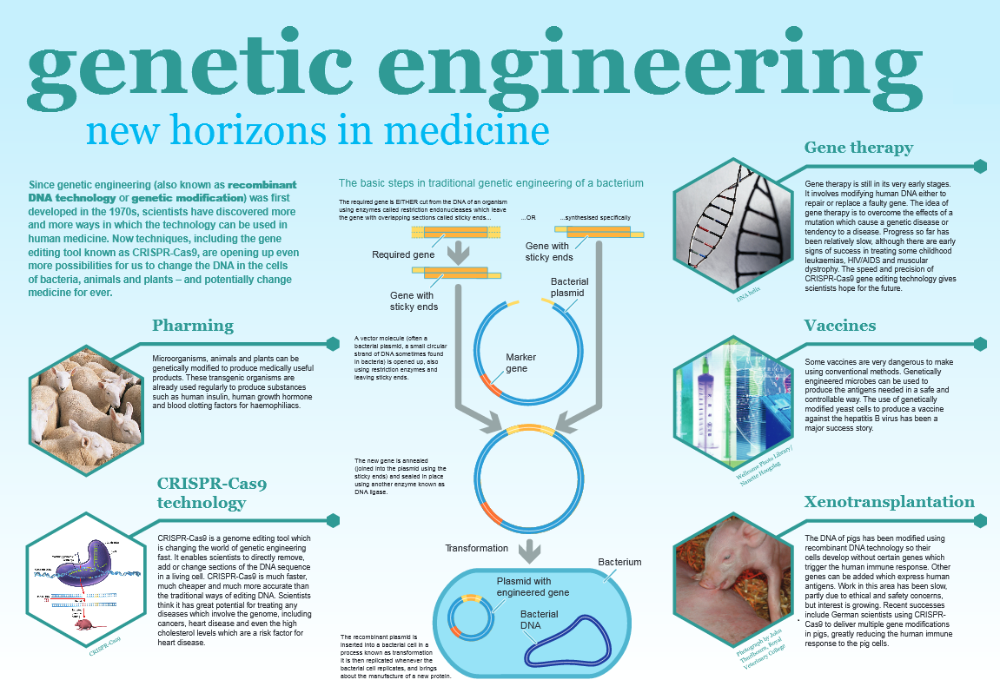

Study 1: Anorexia Nervosa Changing Genes

A Canadian study on anorexia found that those who struggle with anorexia over a long period develop changes in how genes are expressed, otherwise known as epigenetics. It works by a process called methylation, where the level of methylation of a gene determines whether the gene is turned off. [11]

A researcher in the study states that eating disorders tend to become more entrenched over time. These findings point to physical mechanisms acting on physiological and nervous system functions throughout the body.

Study 2: Eating Disorders and Alcohol Dependence

In a further study by the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, researchers found that eating disorders and alcohol dependence may share some of the same genes. [12] Data gathered from 6,000 adult twins in Australia suggests that common genetic factors underlie alcoholism and specific eating disorder symptoms, such as binge eating and purging habits that include self-induced vomiting and the abuse of laxatives.

Louis, researchers found that eating disorders and alcohol dependence may share some of the same genes. [12] Data gathered from 6,000 adult twins in Australia suggests that common genetic factors underlie alcoholism and specific eating disorder symptoms, such as binge eating and purging habits that include self-induced vomiting and the abuse of laxatives.

These findings show that identical twins share 100% of their genetic makeup, while fraternal twins share about half. When comparing identical to fraternal, researchers can develop estimates of how much is due to genes versus environmental factors.

Ultimately, genetic factors behind eating disorders are complex and need further study and advancement. Genetic factors can play a role in the development and onset of eating disorders but do not fully define the causality of an eating disorder.

What Else Causes Eating Disorders?

People are more than a collection of genetic materials. We’re all shaped by our families, cultures, and relationships. So while genes could influence your risk of developing an eating disorder, many other risk factors exist.

So while genes could influence your risk of developing an eating disorder, many other risk factors exist.

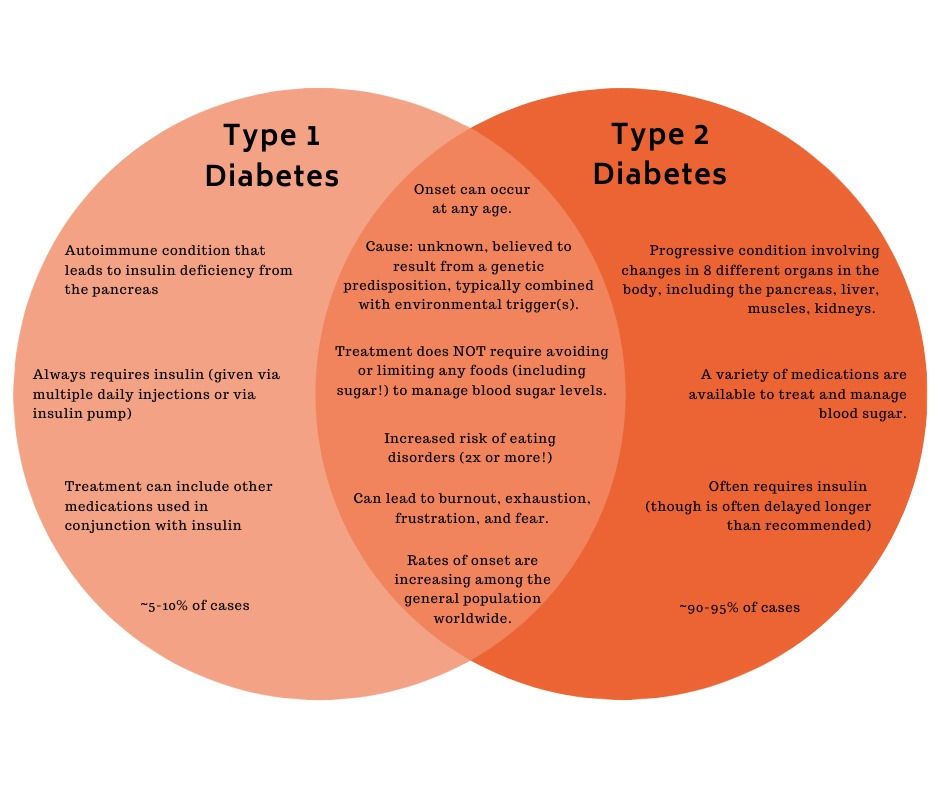

Common risk factors for eating disorders include: [13]

- Psychiatric disorders: Inflexibility, perfectionism, and body image dissatisfaction could influence the development of an eating disorder. In addition, other mental health issues, such as obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), can put you at a greater risk of developing eating disorders.

- Social environment: Weight-based teasing, cultural influences, limited social networks, and historical trauma are all part of eating disorder development.

- Biological: A history of dieting and some medical issues (including diabetes) could raise your risk.

When treating eating disorders, any co-occurring issues must be considered and treated simultaneously, especially any major psychiatric disorders or physical symptoms that may be present.

No matter what causes your eating disorder, you can get better. Current treatments may not be based on genetics, but they have helped thousands of people overcome harmful eating patterns and eating disorders and develop healthier lives.

If you’re struggling with your eating or are concerned about someone else, get help today.

References

- Bulik C. (2021). A Better Understanding of Eating Disorders and Genetics. UNC Health. Accessed September 2022.

- Bulik CM, Blake L, Austin Jehannine. (2019). Genetics of Eating Disorders. Psychiatric Clinics; 42(1):59-73.

- Beckman M. (2003). How Eating Disorders Are Inherited. Science. Accessed September 2022.

- Himmerich H, Bently J, Kan C, Treasure J. (2019). Genetic Risk Factors for Eating Disorders: An Update and Insights into Pathophysiology. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology; 9.

- Genetic Risk Factor for Binge Eating Discovered.

(2016). Boston University School of Medicine. Accessed September 2022.

(2016). Boston University School of Medicine. Accessed September 2022. - Mayhew AJ, Pigeyre M, Couturier J, Meyre D. (2018). An Evolutionary Genetic Perspective of Eating Disorders. Neuroendocrinology; 106:292-306.

- Deciphering the Genetics Behind Eating Disorders. (2021). Science Daily. Accessed September 2022.

- Berrettini W. (2004). The Genetics of Eating Disorders. Psychiatry; 1(3):18-25.

- Lewis T. (2019). Anorexia May Be Linked to Metabolism, a Genetic Analysis Suggests. Scientific American. Accessed September 2022.

- Paolacci S, Kiani AK, Manara E, Beccari T, Ceccarini MR, Stuppia L, Chiurazzi P, Ragione LD, Bertelli M. (2020). Genetic Contributions to the Etiology of Anorexia Nervosa: New Perspectives in Molecular Diagnosis and Treatment. Molecular Genetics and Genomic Medicine; 8(7):e1244.

- Warmflash D. (2015). You Are What You Don’t Eat: Genetics of Anorexia and Bulimia.

Genetic Literacy Project. Accessed September 2022.

Genetic Literacy Project. Accessed September 2022. - Dryden. (2013). Alcohol Abuse, Eating Disorders Share Genetic Link. Washington University in St. Louis. Accessed September 2022.

- Risk Factors. (n.d.). National Eating Disorders Association. Accessed September 2022.

The opinions and views of our guest contributors are shared to provide a broad perspective of eating disorders. These are not necessarily the views of Eating Disorder Hope, but an effort to offer discussion of various issues by different concerned individuals.

We at Eating Disorder Hope understand that eating disorders result from a combination of environmental and genetic factors. If you or a loved one are suffering from an eating disorder, please know that there is hope for you, and seek immediate professional help.

Reviewed By: Jacquelyn Ekern, MS, LPC on January 30, 2023

Published on EatingDisorderHope.com

© Copyright 2023 Eating Disorder Hope. All Rights Reserved. Sitemap.Privacy Policy.Terms of Use.

All Rights Reserved. Sitemap.Privacy Policy.Terms of Use.

MEDICAL ADVICE DISCLAIMER: The service, and any information contained on the website or provided through the service, is provided for informational purposes only. The information contained on or provided through this service is intended for general consumer understanding and education and not as a substitute for medical or psychological advice, diagnosis, or treatment. All information provided on the website is presented as is without any warranty of any kind, and expressly excludes any warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose.

Call a specialist at Timberline Knolls for help (advertisement)

(888) 206-1175

Eating disorders | Tervisliku toitumise informatsioon

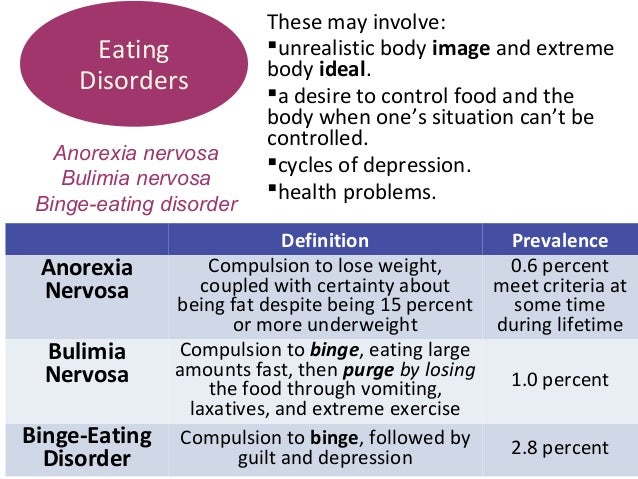

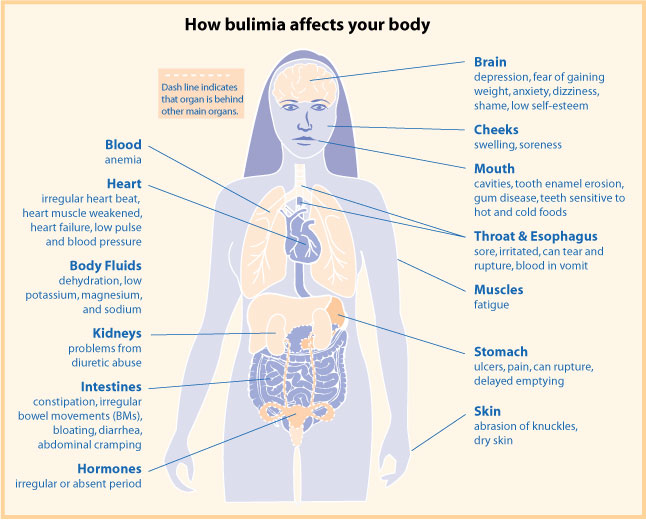

Eating disorders are psychiatric illnesses that damage a person's physical and mental health and impair their overall quality of life - relationships, work and personal development suffer.

Eating disorders disrupt the connection with one's own body, resulting in highly problematic eating behavior. Weight and body shape are overemphasized, underweight is idealized, and various methods are used to lose weight or prevent weight gain.

Weight and body shape are overemphasized, underweight is idealized, and various methods are used to lose weight or prevent weight gain.

Approximately 8% of women and 2% of men will develop an eating disorder during their lifetime. Eating disorders occur in any population, regardless of gender, age, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. However, they are most common in girls and young women.

Eating disorders are a group of diseases that are distributed differently in different classifications. The most common eating disorders are anorexia ( anorexia nervosa ), bulimia ( bulimia nervosa ) and compulsive overeating ( binge-eating disorder ).

The term "eating disorder" is often erroneously used as a synonym for selective eating disorder, as both are associated with eating disorders. However, the reasons for them are different: an eating disorder is caused by a desire to control weight, while in a selective eating disorder, eating certain foods causes anxiety or fear.

Other eating disorders

Anorexia, bulimia and binge eating disorders are the three most common and well-known eating disorders. However, often not all of the symptoms of a person with an eating disorder correspond to one specific disorder. In such cases, these disorders are referred to as "atypical" or "other eating disorders". A common myth is that in such cases the course of the disease is milder and treatment is treated more lightly. However, this is erroneous, since the name of the disease indicates only its diagnostic criteria, and not the severity or course.

All eating disorders, no matter how they are called or classified, are dangerous conditions that impair quality of life and require treatment.

Causes of Eating Disorders

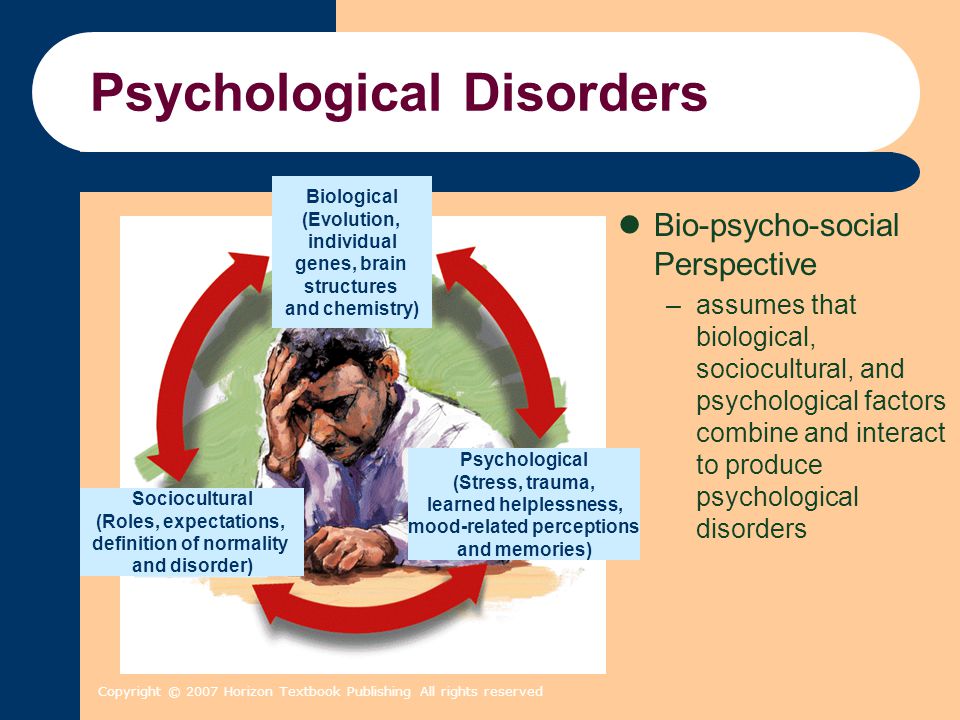

There is never one single cause of an eating disorder. These are complex diseases, in the development of which a combination of many factors plays an important role. Genetic, biological and environmental factors always play a role. Modern social representations, including the culture of diets and the cult of slimness, contribute to the development of psychological vulnerability, which can become a fertile environment for the formation of eating disorders. Probably for the same reasons, a higher incidence of eating disorders is observed in sports in which weight is of great importance, and among representatives of professions focused on appearance. However, it should be emphasized that browsing social networks or playing a certain sport does not contribute to the development of the disease. There are many factors involved in the development of the disease that are usually beyond the control of the individual. However, it is often more practical and even more important to identify the factors that support the disease, since changing them is associated with better treatment outcomes.

Modern social representations, including the culture of diets and the cult of slimness, contribute to the development of psychological vulnerability, which can become a fertile environment for the formation of eating disorders. Probably for the same reasons, a higher incidence of eating disorders is observed in sports in which weight is of great importance, and among representatives of professions focused on appearance. However, it should be emphasized that browsing social networks or playing a certain sport does not contribute to the development of the disease. There are many factors involved in the development of the disease that are usually beyond the control of the individual. However, it is often more practical and even more important to identify the factors that support the disease, since changing them is associated with better treatment outcomes.

Treatment Options for Eating Disorders

Eating disorders can be life-threatening illnesses with a long and chronic course; they have one of the highest mortality rates of any psychiatric illness. Treating eating disorders is often a lengthy and complex process. However, early intervention is paramount to achieve a good treatment outcome.

Treating eating disorders is often a lengthy and complex process. However, early intervention is paramount to achieve a good treatment outcome.

Diagnosis and treatment of an eating disorder usually begins with the family physician. Family sisters can provide advice on healthy eating. Psychiatrists are specialists in the diagnosis and treatment of eating disorders as a psychiatric illness. The participation of a clinical psychologist or psychotherapist is also important.

There are two centers in Estonia that specialize in the treatment of eating disorders: the Department of Eating Disorders of the Mental Health Center of the Tallinn Children's Hospital treats children and adolescents, and the Department of Eating Disorders of the Psychiatric Clinic of the Tartu University Hospital treats adolescents and adults.

For more information about eating disorders and advice on what to do if you suspect a loved one has an eating disorder, visit peaasi.ee.

90,000 genes or jeans4

Genes or jeans [1] :

What causes food disorder?

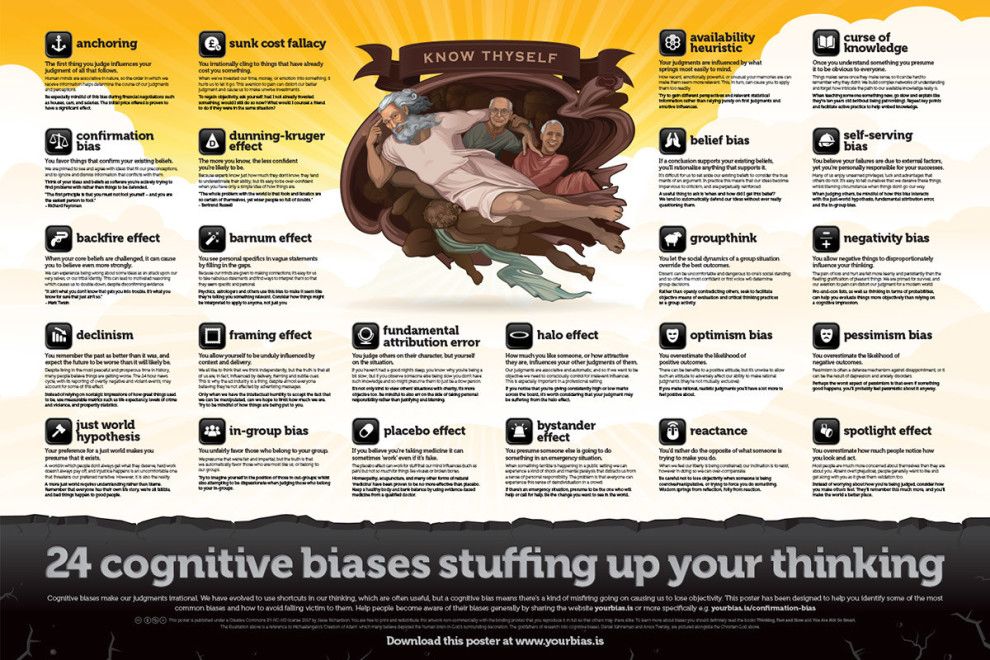

When I tell people about what I do for a living, they usually ask me, "What causes eating disorders?" To be honest, I never know where to start answering them. There are many variables, risk factors, different ways people develop an eating disorder, and so many variations of the disease.

There are many variables, risk factors, different ways people develop an eating disorder, and so many variations of the disease.

A growing body of research has led many in the field to conclude that genetics play a role in the etymology of eating disorders. It has been scientifically proven that a person whose relative suffers from this disorder has a higher risk of developing it, compared to other people, especially if this is a relative of the first stage. However, when it comes to real cases, it is very difficult to separate out genetic and environmental factors as they always interact with each other. Evidence that genetic differences explain the presence or absence of an eating disorder does not mean that all eating disorders are genetic or environmentally independent. According to a number of researchers in the field, the accumulation of different genes, each with a slight additive effect, together with certain environmental factors, increases the risk of developing an eating disorder. Prominent geneticist Cynthia Bulik once said: "Genes load the gun, the environment pulls the trigger."0003

Prominent geneticist Cynthia Bulik once said: "Genes load the gun, the environment pulls the trigger."0003

We know that diets are associated with eating disorders (Keel 2005). Studies have shown that dieting girls are seven to eight times more likely to develop an eating disorder than non-dieting girls (Keel 2005 and Gordon 2000). Most clients with anorexia, bulimia, binge eating admit that they were on a diet before the onset of their disease, this is also confirmed by several studies. Moreover, cross-sectional studies have shown that the number of people with an eating disorder has increased with increasing urbanization. In Fiji, before television, there were no diets and no eating disorders; after television was introduced to the country's population, Fiji girls went on diets for the first time in their lives, supposedly to improve their status, three years later 11 percent even vomited to reduce their own weight. This kind of evidence has led Richard Gordon and others to argue that "if there were no current cultural preoccupation with diets, there would be no epidemics of eating disorders" (Gordon 2000, 158). So the question is, are people with eating disorders trying to fit into their jeans, their genes, or both?

So the question is, are people with eating disorders trying to fit into their jeans, their genes, or both?

Genes: loading a gun

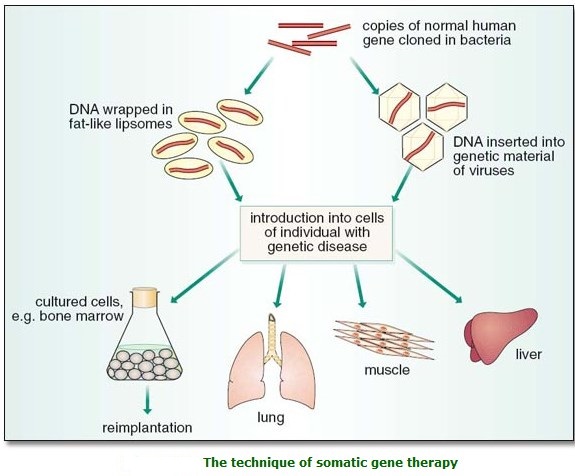

Serious questions remain about the relationship between people with severe eating disorders and those who are only at the stage of concern about their weight and body shape. Are some people more likely to develop an eating disorder and/or problems with eating and body image due to a genetic predisposition? If it has to do with genetics, can we find genes that will eventually help develop new treatments, such as drugs that help prevent or cure disorders? It is in this direction that research is currently being carried out.

Despite varying methodologies, studies consistently show a "significant family element". This is due to the higher levels of anorexia and bulimia in the families of people with these disorders compared to the general population. However, there is a difference between "hereditary" and genetic heritability. First-line relatives share common genes and are in similar environments, so in the absence of adoption-related research, figuring out how one contributes to the other is a difficult task. The research done on twins is very important and interesting. Studies have shown that if one of the identical twins has anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, the other twin is at greater risk of having the same disease than if they were fraternal twins. But the question often arises, could this be due to the fact that identical twins are most often treated similarly and are exposed to identical environmental influences, unlike fraternal twins?

First-line relatives share common genes and are in similar environments, so in the absence of adoption-related research, figuring out how one contributes to the other is a difficult task. The research done on twins is very important and interesting. Studies have shown that if one of the identical twins has anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, the other twin is at greater risk of having the same disease than if they were fraternal twins. But the question often arises, could this be due to the fact that identical twins are most often treated similarly and are exposed to identical environmental influences, unlike fraternal twins?

Research tells us that these factors are not the explanation. They call this "similar environment assumption", which means that they assume that identical twins live in the same or equal environment as fraternal twins. Many question this conclusion, in part because people often use similar parenting methods with identical twins as opposed to fraternal twins. In addition, it is believed that twins have more influence on each other than twins and brothers or sisters. For example, if identical twin sisters look alike and one of them goes on a diet, then this may be reason enough for the other to also go on a diet, which is not the case with twins. The assumption of a level playing field for eating disorders has not been confirmed. Adoption studies would be the most powerful means of determining genetic influence, especially when it comes to identical twins, but such studies have not been conducted. Studies on twins, in particular on anorexia nervosa, are very difficult to conduct due to the low prevalence of the disease in the general population, much less among adopted twins.

In addition, it is believed that twins have more influence on each other than twins and brothers or sisters. For example, if identical twin sisters look alike and one of them goes on a diet, then this may be reason enough for the other to also go on a diet, which is not the case with twins. The assumption of a level playing field for eating disorders has not been confirmed. Adoption studies would be the most powerful means of determining genetic influence, especially when it comes to identical twins, but such studies have not been conducted. Studies on twins, in particular on anorexia nervosa, are very difficult to conduct due to the low prevalence of the disease in the general population, much less among adopted twins.

For more information on the role of genetics in eating disorders, see Cynthia Bulik Clinical Guide to Eating Disorders (Brewerton 2004). A summary of her findings is presented below.

Summary of research on families

- Eating disorders are hereditary

- Primary and female relatives of a patient with an eating disorder are at significantly greater risk of developing eating disorders than other relatives.

Relatives of patients with anorexia nervosa are 11.3 times more likely to develop anorexia nervosa. Relatives of patients with bulimia nervosa are 4.4 times more likely to develop bulimia nervosa.

Relatives of patients with anorexia nervosa are 11.3 times more likely to develop anorexia nervosa. Relatives of patients with bulimia nervosa are 4.4 times more likely to develop bulimia nervosa. - There is a general association between anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and EDNOS ("eating disorder not otherwise specified"). Several studies have shown an increase in the number of people with anorexia, bulimia, EDNOS among relatives of patients with these diseases, in contrast to the average population.

- Preliminary results show that eating disorder is more common in family members whose relative suffers from BED ("binge eating disorders" - psychogenic overeating) than in the average population.

act with caution

as reported earlier, studies about twins in relation to nervous anorexia suggest that the effect of additive genetic effects in capabilities, among large groups of people, is somewhere between the 58th and 88th percent. For bulimia nervosa, heritability estimates vary between 28 and 83 percent (huge variation), with conditions unique to one twin compared to the other contributing to the rest of the variance. These interpretations are based on formulas and statistics. Researchers have to extrapolate the numbers, or "play with the numbers" as some call it, in order to come up with these numbers. I've read the actual research and still can't figure out how these percentages are calculated, or what they mean, so I guess the average reader probably won't fully understand it either. However, many people have taken to the vogue to claim that anorexia and bulimia are "genetic diseases." We must be careful about such conclusions. First, even if genes play a role, there must still be an external trigger[2]. In fact, twin studies have shown a higher level of agreement for the occurrence of anorexia nervosa in fraternal twins than in identical twins.

For bulimia nervosa, heritability estimates vary between 28 and 83 percent (huge variation), with conditions unique to one twin compared to the other contributing to the rest of the variance. These interpretations are based on formulas and statistics. Researchers have to extrapolate the numbers, or "play with the numbers" as some call it, in order to come up with these numbers. I've read the actual research and still can't figure out how these percentages are calculated, or what they mean, so I guess the average reader probably won't fully understand it either. However, many people have taken to the vogue to claim that anorexia and bulimia are "genetic diseases." We must be careful about such conclusions. First, even if genes play a role, there must still be an external trigger[2]. In fact, twin studies have shown a higher level of agreement for the occurrence of anorexia nervosa in fraternal twins than in identical twins.

What can we understand from all this? Non-professionals see the numbers reported to them by the media and mistakenly believe that eating disorders are genetic diseases, and if you have the anorexia genes, your chance of getting it is about 88 percent. In fact, these numbers only mean that genes play a role in determining the extent to which some people develop an eating disorder.

In fact, these numbers only mean that genes play a role in determining the extent to which some people develop an eating disorder.

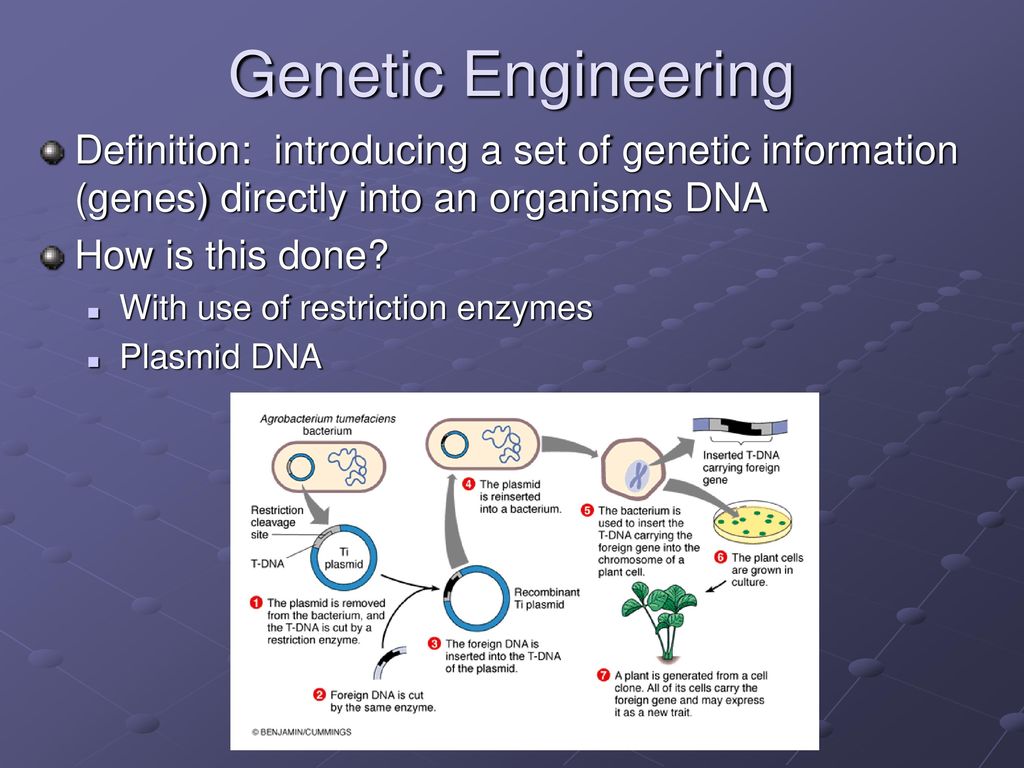

In order to actually prove a genetic etymology, molecular studies are needed in which scientists look for the actual genes (more correctly called gene alleles genes) that increase the risk of developing an eating disorder. Only a small number of these types of studies have been conducted, and the results have been mixed. In one of the most promising areas, called the 5HT2A receptor, five studies have shown an association with anorexia nervosa. However, six other studies showed no link! Those who are skeptical of the fact that, until now, no single gene has been the cause of any mental illness. For a more detailed study of genetic etymology, read Ty Colbert's book Blaming your genes for everything. [3]

We need more evidence regarding the scope and significance of genetic and biological responsibility for anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating. The study of the nature of these diseases suggests a number of possibilities of genetically transmitted "trends" or "vulnerabilities" that may influence the development of an eating disorder, for example, some kind of genetic tendency to anxiety, depression or obsessive-compulsive behavior. It becomes clear why the most anxious and impulsive among us are more susceptible to cultural influences and have the temperament to go on extreme diets. Naturally, the person among us most aspiring to perfectionism would be the best in fulfilling and attaining the role of the “thinness culture ideal.” This is a good explanation for the fact that when I was dieting in high school with a few of my friends, I was the only one who developed anorexia nervosa.

The study of the nature of these diseases suggests a number of possibilities of genetically transmitted "trends" or "vulnerabilities" that may influence the development of an eating disorder, for example, some kind of genetic tendency to anxiety, depression or obsessive-compulsive behavior. It becomes clear why the most anxious and impulsive among us are more susceptible to cultural influences and have the temperament to go on extreme diets. Naturally, the person among us most aspiring to perfectionism would be the best in fulfilling and attaining the role of the “thinness culture ideal.” This is a good explanation for the fact that when I was dieting in high school with a few of my friends, I was the only one who developed anorexia nervosa.

I believe there is a genetic predisposition that makes people like me more vulnerable to developing an eating disorder, especially anorexia nervosa. I am sure that I have exactly such genes. However, my genetic predisposition was not a problem when it helped me get straight A's, skip sixth grade, go to college at age sixteen, and get two master's degrees by age twenty-one. It's only when applied to diet that my genes become a problem. If I had lived in another culture where there was so much emphasis on thinness, where all my friends weren't on diets, I don't think I would have developed anorexia. However, given the cultural background in which I grew up (twiggy jeans were very popular then), combined with the psychological stressors in my life, the goal of fitting into twiggy jeans was a reasonable desire, and limiting oneself to food was a reasonable decision, at least for initial stage.

It's only when applied to diet that my genes become a problem. If I had lived in another culture where there was so much emphasis on thinness, where all my friends weren't on diets, I don't think I would have developed anorexia. However, given the cultural background in which I grew up (twiggy jeans were very popular then), combined with the psychological stressors in my life, the goal of fitting into twiggy jeans was a reasonable desire, and limiting oneself to food was a reasonable decision, at least for initial stage.

Basic personality traits, such as a desire to prevent harm or an obsession with perfection, sophistication, which predispose a person to an eating disorder, may be associated with some biological factors, such as an alteration in serotonin neurotransmission. Walter Kay (1998), an award-winning researcher in the field of eating disorders, reported on abnormal serotonin activity that persists during recovery in patients with an eating disorder. However, we do not know if these changes existed before the illness. In addition, pre-illness and post-recovery studies show an association between eating disorders and anxiety/harm avoidance traits, obsession with perfection, symmetry, and precision. Serotonin may contribute to the development of an eating disorder through its effect on traits such as satiety. In addition, newer research suggests that dopamine dysfunction appears to contribute to changes in weight, food intake, and motor activity in anorexia nervosa. We have yet to find out what all of this really means, but there is one important fact that cannot be ignored. For the most part, all of the biological abnormalities found during an eating disorder—be it neurotransmitters, hormone levels, temperature, even brain shrinkage—return to normal when weight and nutrition are restored. Recently, a new study has emerged that may indicate changes in certain neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, during recovery. But these changes may have existed before the eating disorder. We need more research. There are also some exceptions in the area of loss of bone density and amenorrhea, but this is the result of the disease, not its cause.

In addition, pre-illness and post-recovery studies show an association between eating disorders and anxiety/harm avoidance traits, obsession with perfection, symmetry, and precision. Serotonin may contribute to the development of an eating disorder through its effect on traits such as satiety. In addition, newer research suggests that dopamine dysfunction appears to contribute to changes in weight, food intake, and motor activity in anorexia nervosa. We have yet to find out what all of this really means, but there is one important fact that cannot be ignored. For the most part, all of the biological abnormalities found during an eating disorder—be it neurotransmitters, hormone levels, temperature, even brain shrinkage—return to normal when weight and nutrition are restored. Recently, a new study has emerged that may indicate changes in certain neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, during recovery. But these changes may have existed before the eating disorder. We need more research. There are also some exceptions in the area of loss of bone density and amenorrhea, but this is the result of the disease, not its cause.

Significance of studying possible genetic causes

Advances in genetics and neuroscience have had a huge impact on medicine in all sorts of ways. The results are important for the development of new drugs and specific psychological therapies in order to compensate for the genetic predisposition. This is one of the most promising discoveries that has come about through the study of genetic etiology. Moreover, it is hoped that biological information in the future will help convince insurance companies that eating disorders are real diseases and not a voluntary choice of a person.

However, while some hope that we will find genetic and/or biological risk markers, insurance companies do not require tests for these markers. Can a positive test disqualify those who seek insurance? Moreover, can people with an eating disorder get a negative test result because their cases of illness are "not enough"? Although I have asked a few of my colleagues to highlight these issues, as I believe they are very important, they need to be thought about, and for now we are trying to follow this path.

Other equally important aspects related to genetic etiology relate to the fact that over the past forty years there has been a tremendous increase in cases of anorexia and bulimia, even if (as some point out) this increase has slowed down or perhaps even stopped for anorexia nervosa in the 1990s. Our species has not developed new genes, so how can we explain this? The same applies to cross-sectional studies; what has changed in other cultures and countries that has made their inhabitants more vulnerable to eating disorders, certainly not genes. Since we know that causation must be a combination of genetics and environment in any case, it makes sense to look at the kinds of environments that will negate the predisposition. After all, we can change our environment, while changing a large number of "addictive genes", shall we say, is problematic. Moreover, despite decades of research showing that alcoholism and chemical dependency may be associated with genetic vulnerability, we have yet to find any genes or drugs that can cure/prevent the disease. Even one of the best researchers, Cynthia Bulik (Brewertom 2004), when discussing the implications of research on families and twins, said

Even one of the best researchers, Cynthia Bulik (Brewertom 2004), when discussing the implications of research on families and twins, said

emphasizing the fact that they have the ability to influence

to the environment and that the environment can be

, and also cause memories,

Parents begin to understand that although they are nothing

can do to change the DNA they pass on to their children, they

can change the environment that affects

gene expressions.

I am of the same mindset! We must work to change the environment. Bulik suggests, going forward, that preventive interventions focus on prenatal and postnatal care for women with eating disorders. But then the question becomes, shouldn't we be doing this right now? We know that eating disorders are inherited, do we need to know that the disease is genetic in order to intervene? Attempts to prevent disease must be made in such families, no, in general, in all families.

Bulik's latest recommendation concerns the children of women with anorexia and bulimia, who are at very high risk of developing the disease. She says, "Much like children of alcoholics are encouraged to delay drinking, children of people with an eating disorder could be helped to avoid dietary errors, develop non-body-oriented self-esteem, and other ways to prevent the onset of an eating disorder." This is sound advice that we can take right now, without researching random genes - and should help every girl and every boy, regardless of the history of eating disorders in their family. Genetically based or not, in order to prevent an eating disorder, we must change the environment that provokes and perpetuates it.

Environment: pulling the trigger

How can you avoid dieting traps or develop non-body-oriented self-esteem in a society where your weight is more important than who you really are? For more and more girls, being a woman means dieting. Studies show that the vast majority of American girls and women, perhaps more than 90 percent, say that they are disgusted with their bodies or are unhappy with them. One study suggests that 80 percent of fourth grade girls are on a diet, and 10 percent of them admit to vomiting to lose weight. A lot of teenage girls smoke cigarettes, and some snort cocaine - not for pleasure, but to lose weight. Some girls claim that they would rather die than be fat. Due to the large amount of evidence that desire for thinness, irrational fear of being overweight, impaired body image, intermittent diets, preoccupation with weight have been found in those with an eating disorder, we cannot downplay the impact cultural, social and psychological phenomenon as a significant risk factor in the development of this disease.

Studies show that the vast majority of American girls and women, perhaps more than 90 percent, say that they are disgusted with their bodies or are unhappy with them. One study suggests that 80 percent of fourth grade girls are on a diet, and 10 percent of them admit to vomiting to lose weight. A lot of teenage girls smoke cigarettes, and some snort cocaine - not for pleasure, but to lose weight. Some girls claim that they would rather die than be fat. Due to the large amount of evidence that desire for thinness, irrational fear of being overweight, impaired body image, intermittent diets, preoccupation with weight have been found in those with an eating disorder, we cannot downplay the impact cultural, social and psychological phenomenon as a significant risk factor in the development of this disease.

Fiji Island:

On how television changed the culture of the country

The study performed by Anna Becker and its colleagues (2002) on the island of Fidgei is an essential example environment. I first heard this story from Anna when I was at a conference, and she was talking about how shocked she was by the impact television had had on the people of Fiji. When she was younger, she spent time on the island and witnessed that "in many of the industrialized societies of traditional Fiji, the prevailing pressure to be slim, which was thought to be associated with diets and malnutrition, was absent on the island." In fact, traditional Fijian values encouraged a healthy appetite and a voluminous body. Trying to change your body through various diets or exercise was not part of the culture of the island; on the contrary, there was a culture-specific disease in Fiji known as "macake" which means "getting thin". When someone lost weight, acquaintances tried to fatten him up. Anna Becker and her Harvard colleague set out to study the impact of the introduction of television on the 2,000-year-old culture of Fiji. Has Western Television Influenced the Behavior and Eating Disorders of the People Television was first introduced to Nandrong residents [1] in 1995, only a month before the first dataset was collected.

I first heard this story from Anna when I was at a conference, and she was talking about how shocked she was by the impact television had had on the people of Fiji. When she was younger, she spent time on the island and witnessed that "in many of the industrialized societies of traditional Fiji, the prevailing pressure to be slim, which was thought to be associated with diets and malnutrition, was absent on the island." In fact, traditional Fijian values encouraged a healthy appetite and a voluminous body. Trying to change your body through various diets or exercise was not part of the culture of the island; on the contrary, there was a culture-specific disease in Fiji known as "macake" which means "getting thin". When someone lost weight, acquaintances tried to fatten him up. Anna Becker and her Harvard colleague set out to study the impact of the introduction of television on the 2,000-year-old culture of Fiji. Has Western Television Influenced the Behavior and Eating Disorders of the People Television was first introduced to Nandrong residents [1] in 1995, only a month before the first dataset was collected. The second set of data was collected in 1998 after Fijian girls were exposed to television for just over three years. Anna Becker's group found that key indicators of disordered eating were significantly more common in 1998. A body of descriptive data showed that approximately 80 percent of Fijian girls at the time were interested in losing weight as a way to model themselves after Western TV characters. Many associated weight loss with improving their job prospects or improving their career progression. It is worrying that the percentage of subjects who reported that they vomited for weight loss, 1995 was 0 percent, while in 1998 it rose to 11.3 percent. The Fiji girls did not develop any new genes during the experiment. They created a goal for themselves - "fit into new jeans" and developed a strategy in order to achieve it.

The second set of data was collected in 1998 after Fijian girls were exposed to television for just over three years. Anna Becker's group found that key indicators of disordered eating were significantly more common in 1998. A body of descriptive data showed that approximately 80 percent of Fijian girls at the time were interested in losing weight as a way to model themselves after Western TV characters. Many associated weight loss with improving their job prospects or improving their career progression. It is worrying that the percentage of subjects who reported that they vomited for weight loss, 1995 was 0 percent, while in 1998 it rose to 11.3 percent. The Fiji girls did not develop any new genes during the experiment. They created a goal for themselves - "fit into new jeans" and developed a strategy in order to achieve it.

Media Influence

A study in Fiji is just one indication that in today's media-based world, thinness is increasingly reflecting not only self-sacrifice but also self-sacrifice , success, self-control, status. A common attitude is that the fatter a person is, the more unattractive, lazy, more self-indulgent and unable to control himself.

A common attitude is that the fatter a person is, the more unattractive, lazy, more self-indulgent and unable to control himself.

Culturally based prejudices about weight and body shape are also broadcast through media other than television in various ways. In print ads with a very thin model and the slogan "The same shape" the question arises: they are trying to sell us clothes or a body. Such media advertising reflects and shapes our perceptions and standards of beauty. Various advertisements on how to lose weight and not gain it back can be found in every magazine and newspaper, as well as on billboards, television commercials and car bumper stickers, which are emblazoned with such slogans as "Lose weight now, ask me about it now." Equally troubling, 10 years ago, when this book was written, magazines published women's stories with subtitles such as "In just 12 weeks, I was able to go from size 16 to 10" or "I lost 10 pounds in 4 weeks." The worst thing I ever saw was a magazine ad for a restaurant in New York. It featured a photograph of a set of forks against a black background, with the words “Supermodels love our pasta. She comes as easily as she leaves. If this pisses you off as much as it pisses me off, then you can join one or more eating disorder organizations that help fight back against such ads.

It featured a photograph of a set of forks against a black background, with the words “Supermodels love our pasta. She comes as easily as she leaves. If this pisses you off as much as it pisses me off, then you can join one or more eating disorder organizations that help fight back against such ads.

The number of weight loss programs, weight loss books and diet food advertisements is steadily growing, creating a multi-billion dollar industry. With the rise of diet-related advertising, the body shape of Playboy centerfolds, Miss America contestants and supermodels has shrunk to the point where many of them have experienced eating disorders. Not surprisingly, there has been a significant increase in the prevalence of eating disorders and malnutrition. Because the socially prescribed body weight is so low and the fear of being fat so high, body dissatisfaction is very widespread and there is a lot of evidence that diets don't work (approximately 98 percent of those who lose weight gain it back), it follows that some people will resort to extreme measures, such as fasting or "cleansing" the body, to cope with their dissatisfaction with the figure or size, striving to achieve "Toy". form itself."

form itself."

Most advertisements and dietary products are aimed at girls, but men are also not spared. Men are increasingly being portrayed as decorative objects in advertisements for cosmetics and weight loss products, just as women have been since the beginning of such advertisements. However, eating disorder is still a problem, predominantly common among women, from about 90 to 95 percent of all known cases are in women. In this case, do not forget: men are usually judged for what they do, and women for how they look. For all 50 years of existence of the magazine Life , there were only 19 women on the cover who were not models or actresses (or wives of other famous personalities), these were women who were not on the cover because of their attractiveness (Wolf 1991). Women in our society have been taught that their worth depends on their appearance and the shape of their body.

Women's concerns about their perceived weight and body shape are based on societal attitudes about what is considered acceptable and what is not. Current beauty standards contribute to body image disturbance, which is one of the diagnostic features of anorexia and bulimia. After all, it is the disturbed perception of one's own body that distinguishes these diseases from other psychological conditions, which include weight loss and malnutrition. There have been cases of these diseases in which people did not report disturbed body image or weight loss as motivators for their symptoms (for example, in other cultures such as China), but such cases require further study before criteria for body image can be changed. Body image disorder is defined in the eating disorders section of DSM-1V-TR [2] as follows:

Current beauty standards contribute to body image disturbance, which is one of the diagnostic features of anorexia and bulimia. After all, it is the disturbed perception of one's own body that distinguishes these diseases from other psychological conditions, which include weight loss and malnutrition. There have been cases of these diseases in which people did not report disturbed body image or weight loss as motivators for their symptoms (for example, in other cultures such as China), but such cases require further study before criteria for body image can be changed. Body image disorder is defined in the eating disorders section of DSM-1V-TR [2] as follows:

For anorexia nervosa. In patients with this disease, there is a violation in the perception of one's own weight and body, and an excessive influence of weight and body shape on a person's self-esteem, denial of the seriousness of the current low body weight.

For bulimia nervosa. Patient's self-esteem is unnecessarily affected by weight and body shape.

Patient's self-esteem is unnecessarily affected by weight and body shape.

After almost three decades of working with eating disorders, I am increasingly convinced that our society, and not any particular combination of genes, has led to an increase in the excessive influence of weight and body shape on self-esteem and self-confidence. Advances in technology have fueled the obsession with the female body and general appearance through inventions such as the compact mirror (so you can always know how you look) and cosmetics (so you can always improve your appearance. Technology has also given us the ability to display images on various gadgets. in our homes and on billboards when we're out and about, constantly reminding us of how we should look.Now, thanks to our amazing technology, it's possible to "cosmetically" remove fat from our thighs and add it to our breasts. reasons given to children as young as 12. It is no wonder that younger and younger children develop eating disorders. 0003

0003

The Fiji study found that while eating disorders are increasingly common in cultures around the world, Western women (women who are in contact with Western values and ideals) are at a much greater risk of getting sick than others and the degree of Westernization, appears to increase risk (Dolan 1991). An extensive historical cross-cultural review by Miller and Pumariega [3] (2001) indicates that "cultural change itself may be associated with increased vulnerability to eating disorders, especially when it comes to physical aesthetics" . The requirement to be thin is one of the latest versions of torture used to turn women's bodies into a certain standard of beauty that changes over time and culture to culture. In the United States of America, Canada, Europe, Australia and a growing number of countries, women have undergone fundamental changes in their position in society, both economically and politically, and thinness has become a symbol of status, control and virtue. A young woman, during a period of maturation and self-discovery, takes female role models from her culture. At the same time, she grows breasts and develops body fat in order to prepare for menstruation, pregnancy, and eventually childbirth and breastfeeding, while she is forced to be thin in order to be accepted by society. Eating disorders must be understood in the context of modern culture, where the idea that extreme thinness is attractive and desirable for women is so widely accepted that it is rarely questioned. Here is an example of what women say about these cultural dictates:

A young woman, during a period of maturation and self-discovery, takes female role models from her culture. At the same time, she grows breasts and develops body fat in order to prepare for menstruation, pregnancy, and eventually childbirth and breastfeeding, while she is forced to be thin in order to be accepted by society. Eating disorders must be understood in the context of modern culture, where the idea that extreme thinness is attractive and desirable for women is so widely accepted that it is rarely questioned. Here is an example of what women say about these cultural dictates:

- You cannot trust your own body. It challenges you and shows you all your shortcomings. I always thought I could do anything, but I can't look like a Madison Avenue model. But of course I can try.

- When there is no one around for you, there is always food nearby; food… exactly what I want when I want something. I don't need anyone's approval or involvement that might disappoint me.

Why do I choose food to satisfy my need? … Because I shouldn't have that need at all.

Why do I choose food to satisfy my need? … Because I shouldn't have that need at all. - I will never allow myself to be fat. I've seen what it has done to my mother and my sister, and if I have to die trying to be thin, I agree.

- Being thin, I was able to achieve something in my life. Everyone tells me about it. Even those who want me to put on weight reinforce their opinion that I have reached an extreme in weight that few can match.

All these women show a struggle much deeper than "fat versus thin". In essence, they also describe the struggle for success, power, control, distinction, and recognition. The question seems deceptively clear: the control of mind over matter. We tend to pay attention to those people who can lose weight without putting it back on, even if they are unhappy and unhealthy. The "major power" that people with anorexia experience is that they can go without food, punishing their bodies and forcing them into submission. The increased prevalence of anorexia and bulimia in certain subgroups, such as dancers, models, gymnasts, jockeys, further supports the influence of cultural factors as a cause of eating disorders.

The Situation as a Whole

While it would be easy to blame the current epidemic of eating disorders on a purely biased societal standard of thinness as a much more simplistic view of one's standards of beauty, it is. Eating disorders are a very complex combination of both our culture and various underlying relationship conflicts with others, with ourselves, and most likely the patient's biochemistry and genes. After all, not every woman in our conscious society develops an eating disorder. Not all fourth graders who diet develop an eating disorder. Two girls can grow up in the same house with the same parents and the same cultural influences, but one develops an eating disorder while the other has a perfectly normal relationship with food, body and weight for the entire life. As discussed in the first chapter, cases of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa have been documented even when public standards of beauty differed greatly from the current ones and were generally different. In his book Holy Anorexia [4] Rudolph Bell (1985) provides a compelling and suggestive analogy between some medieval Italian saints, whom he describes as those with "anorexia saints", and people who meet the diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa today. day. Bell describes how, in the service of purity and the quest for perfect holiness, the saints became starved, hyperactive, perfectionistic, and lost more than 2.5 percent of their normal body weight. Bell believes that today's cultural ideals are physical health, composure, and self-control; in medieval Christendom these were: spiritual health, fasting, and self-denial. In both cases, only some people in search of their ideal become champions of self-sacrifice and supporters of the superiority of mind over matter (perhaps those whose temperament is genetically suitable for this). For both the “medieval anorexia saint” (as Bell calls it) and the patient of today, their behavior and inveterate devotion, for which they initially receive rewards and praise from their elders and peers, eventually become self-destructive and turn into an uncontrolled threat to a life that requires outside intervention.

In his book Holy Anorexia [4] Rudolph Bell (1985) provides a compelling and suggestive analogy between some medieval Italian saints, whom he describes as those with "anorexia saints", and people who meet the diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa today. day. Bell describes how, in the service of purity and the quest for perfect holiness, the saints became starved, hyperactive, perfectionistic, and lost more than 2.5 percent of their normal body weight. Bell believes that today's cultural ideals are physical health, composure, and self-control; in medieval Christendom these were: spiritual health, fasting, and self-denial. In both cases, only some people in search of their ideal become champions of self-sacrifice and supporters of the superiority of mind over matter (perhaps those whose temperament is genetically suitable for this). For both the “medieval anorexia saint” (as Bell calls it) and the patient of today, their behavior and inveterate devotion, for which they initially receive rewards and praise from their elders and peers, eventually become self-destructive and turn into an uncontrolled threat to a life that requires outside intervention.

However, even today, people with anorexia often report hunger for goals other than thinness, such as feeling neat, clean, in control, and achieving something that is hard to give up. In other words, in the search for holiness and subtlety, aspiration becomes a goal. Self-sacrifice and control, independence from physical needs, and a sense of caring for others while limiting oneself are all characteristics demanded in our society.

Our real challenge and goal in the fight against eating disorders is to separate the cultural ideal of thinness from female beauty, from the recognition and respect of women in society, so that in the end the process of fasting becomes useless.

However, it is important to understand eating disorders as culturally determined, but we cannot solely blame them for the cultural desire for thinness. Current body shape standards and the fight against obesity, along with the vast abundance of food in the lives of many people, provides the ideal conditions for fighting for the will to fight, for creating insecurity in a sense of power and control, for a sense of desperation, in order to eventually gain control over people.