Gender dysphoria dsm 6

(In)validating transgender identities: Progress and trouble in the DSM-5

By Kayley Whalen, Task Force board liaison

Last week, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) approved the final text for the fifth version of its manual that provides criteria for mental health disorders. The manual, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, hereinafter DSM-5, will be released officially in 2013. Earlier this year, the APA also released a position statement affirming their support of transgender rights, and the language of the DSM-5 reflects an increased sensitivity to and respect for the transgender community.

The fifth version of DSM is important for several reasons. The DSM-5 contains two diagnoses relevant to transgender and gender-variant individuals. First, the previous and disliked “Gender Identity Disorder” (GID) will be replaced with the diagnosis “Gender Dysphoria”. The second change will replace “Transvestic Fetishism” with “Transvestic Disorder,” which is a disturbing development because the phrase “Transvestic Disorder” is stigmatizing and problematic for a number of reasons.

The Task Force hails the APA’s revision and renaming of GID to “Gender Dysphoria” as a step in the right direction, and applauds the APA continuing to take a positive stance on transgender civil rights. However, it is our firm stance that both “Gender Dysphoria” and “Transvestic Disorder” should be removed from the DSM entirely. While we support retaining “Gender Dysphoria” for the time being, the “Transvestic Disorder” diagnosis should be removed immediately. (Note: The renaming GID has been confusingly called “removal” by some community members yet our analysis is that it is better understood as a renaming and/or revision.)

Gender variance is not a psychiatric disease; it is a human variation that in some cases requires medical attention. For this edition of the DSM, because there is no other medical diagnosis available for transgender people to seek reimbursement of medical expenses under, we recommended that some version of gender dysphoria appear in DSM-5 as a stop-gap measure. There is a continuing need for the medical and insurance industries to update their procedures for reimbursement so that gender dysphoria can be removed entirely in the future.

There is a continuing need for the medical and insurance industries to update their procedures for reimbursement so that gender dysphoria can be removed entirely in the future.

Yet, we must understand that as long as transgender identities are understood through a “disease” framework, transgender people will suffer from unnecessary abuse and discrimination from both inside and outside the medical profession. As long as gender variance is characterized by the medical field as a mental condition, transgender people will find their identities invalidated by claims that they are “mentally ill,” and therefore not able to speak objectively about their own identities and lived experiences. This has even been used to justify discrimination against transgender people, such as in child custody cases, discrimination in hiring/workplace practices, or justifying them to be mentally unfit to serve in the military.

Even more alarming is the high rate of children—and adults—who will continue to be forcibly subjected to abusive“reparative” therapies designed to “cure” them of gender variance. While the “Gender Identity Disorder” framework of the DSM-IV did have some usefulness for accessing care, there is significant evidence that it has been gravely abused since its creation as a way to subject gender-variant children and adults to damaging “reparative” treatments against their will.

While the “Gender Identity Disorder” framework of the DSM-IV did have some usefulness for accessing care, there is significant evidence that it has been gravely abused since its creation as a way to subject gender-variant children and adults to damaging “reparative” treatments against their will.

The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force is also strongly opposed to the inclusion of the diagnosis of “Transvestic Disorder” in the DSM-5 for many reasons. First, many of the paraphillias should not exist as diagnoses overall, given that many are simply diverse expressions of sexuality that harm no one. Second, “Transvestic Disorder” pathologizes and invalidates the identities of individuals who do not conform to stereotypical gender roles. This includes all transgender people who are regularly dismissed as transvestites or fetishists. Third, the definition of “Transvestic Disorder,” unlike its predecessor “Transvestic Fetishism” in the DSM-IV, for the first time includes “autogynephilia,” a supposed condition created by Dr. Ray Blanchard, whose controversial theory has garnered widespread criticism from both the medical community and the transgender community. Blanchard’s theory of autogynephelia falsely argues that someone who is assigned male-at-birth and expresses femininity can only be either a gay male or a “gender dysphoric male…sexually oriented toward the thought or image of themselves as a woman.[1]” Thus, transgender women who identify as heterosexual women are told that they are actually gay men. If they are attracted to women, they are told they have a fetish. This denies the reality that many transgender women live happy, healthy lives as lesbians or other various sexual orientations. Finally, the “Transvestic Disorder” is also blatantly sexist in enforcing binary gender roles because it makes what would otherwise be a non-specified fetish into a special type of fetish (one that gets its own Disorder category) because it involves cross gender behavior when those assigned male-at-birth wear clothes associated with women.

Ray Blanchard, whose controversial theory has garnered widespread criticism from both the medical community and the transgender community. Blanchard’s theory of autogynephelia falsely argues that someone who is assigned male-at-birth and expresses femininity can only be either a gay male or a “gender dysphoric male…sexually oriented toward the thought or image of themselves as a woman.[1]” Thus, transgender women who identify as heterosexual women are told that they are actually gay men. If they are attracted to women, they are told they have a fetish. This denies the reality that many transgender women live happy, healthy lives as lesbians or other various sexual orientations. Finally, the “Transvestic Disorder” is also blatantly sexist in enforcing binary gender roles because it makes what would otherwise be a non-specified fetish into a special type of fetish (one that gets its own Disorder category) because it involves cross gender behavior when those assigned male-at-birth wear clothes associated with women. (What is a woman who wears men’s clothing called? A woman.)

(What is a woman who wears men’s clothing called? A woman.)

Presumably to mask the inherent sexism of Transvestic Disorder, the APA, in the second draft of the DSM-5, added the “autoandrophilia” specifier to the “Transvestic Disorder” diagnosis, creating a paraphilia specifier for female-assigned-at-birth individuals who expresses masculinity. There is even less evidence that autoandrophilia exists that there is for autogynephilia. Ultimately, the inclusion of “Transvestic Disorder,” “autogynephelia” and “autoandrophilia” in the DSM-5 demonstrates a kind of sexism that is astonishing for psychiatry in the twenty-first century, and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force strongly advocates for their removal from the DSM.

The Task Force has long maintained that an identity framework — not a disease framework — is the most ethical and appropriate approach for mental health providers serving transgender and gender nonconforming children and adults. At the Task Force, we are working toward a day when the psychiatric profession, and our larger society, embraces a vibrant spectrum of gender expression among infinite human possibilities. To ensure that transgender people are able to get the care that they need, there should be some type of medical diagnosis, such as an endocrinology-based one, for health insurance purposes. But ultimately, as science and our movement advances, we fully expect both “Gender Dysphoria” and “Transvestic Disorder” to be removed from the DSM-6 and will continue to work for that future.

To ensure that transgender people are able to get the care that they need, there should be some type of medical diagnosis, such as an endocrinology-based one, for health insurance purposes. But ultimately, as science and our movement advances, we fully expect both “Gender Dysphoria” and “Transvestic Disorder” to be removed from the DSM-6 and will continue to work for that future.

1. R. Blanchard, “The Classification and Labeling of Nonhomosexual Gender Dysphoria,” Archives of Sexual Behavior, v. 18 n. 4, 1989, p. 322-323.

Share:

Gender Incongruence is No Longer a Mental Disorder

Gender Incongruence is No Longer a Mental Disorder

M. Fernández Rodríguez1,2*, M. Menéndez Granda3, Villaverde González4

1Mental Health Center I “La Magdalena” University Hospital San Agustín de Avilés. Health Area III, Asturias, Spain

2Gender Identity Treatment Unit of Principality of Asturias (UTIGPA), Spain

3Master of General Health Psychology, University of Oviedo, Asturias, Spain

4Intern Resident Psychologist, University Hospital San Agustín Avilés.

Health Area III Asturias, Spain

Abstract

The aim of this article is to highlight the historical path of transsexualism diagnosis since its inclusion to its elimination from the catalogue of mental disorders. We analyse the terminological changes that may account for this phenomenon in order to depathologise and just as the controversies raised by its location in the new Manual of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems ICD-11.

ICD-11 drives out the term "Transsexualism" and replaces it with the term "Gender Incongruence" (GI). This new terminology will no longer be part of the chapter on mental disorders (Chapter 6) but a new chapter (Chapter 17) entitled "Conditions relating to sexual health" is created. These changes of ICD-11 represent a breakthrough and a great sense of freedom for trans people, since WHO has included the different variants of gender in normality by not being considered a mental disorder.

The aim of this paper is to highlight the historical development of the diagnosis of transsexualism from its inclusion to the elimination of the chapter of mental disorders. Terminological changes that can best reflect this phenomenon to depathologize and the controversies raised by its location in the new manual of ICD-11 are analyzed.

Transsexualism, gender identity disorder or gender dysphoria, since was included in the international diagnostic classifications was (ICD-91, ICD-102) and is part of the chapter on mental disorders (DSM-53).

The diagnosis of transsexualism debuts in the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems in 1978 (ICD-9)1. It was included in the section named “Sexual deviations and disorders”, within neurotic disorders, personality disorders and other non-psychotic mental disorders. Therefore, it was at the same level as paraphilias and sexual deviations. In 1992, the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)2 entered into force. Unlike the ICD-91, gender identity disorders are an independent group of disorders of sexual inclination and sexual dysfunctions, although they continue to be included in adult personality and behaviour disorders (F60-F69)4.

Unlike the ICD-91, gender identity disorders are an independent group of disorders of sexual inclination and sexual dysfunctions, although they continue to be included in adult personality and behaviour disorders (F60-F69)4.

On June 18, 2018 the World Health Organization (WHO)5 establish itself as a pioneer in the process of depathologization of transsexuality. This struggle, in order to stop transsexuality from being considered a mental disorder and to eliminate the gender identity disorder of the international manuals of mental disorders, had been represented in the last decade by the powerful movements of depathologization (Stop Trans Pathologization, depsychopathologisation statement released, etc)6,7,8.

The Manual of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) eliminates the term “transsexualism” and replaces it with the term “Gender Incongruence ” (GI)9. This new terminology will no longer be part of the chapter on mental disorders (chapter 6) but a new chapter is created (chapter 17) called “conditions related to sexual health”. These ICD-11 changes implied an advance and a great liberation for trans people who were doubly stigmatized since transsexuality has always been located around paraphilias and within personality disorders. Even so, the “gender incongruence” continues to be part of this manual that encompasses all diseases.

These ICD-11 changes implied an advance and a great liberation for trans people who were doubly stigmatized since transsexuality has always been located around paraphilias and within personality disorders. Even so, the “gender incongruence” continues to be part of this manual that encompasses all diseases.

The name itself “Conditions related to sexual health” again creates confusion between the two realities sex/gender. Sex refers to the biological characteristics of a person (male or female of the human being) while gender is a sociocultural construction that involves psychological aspects (identity)10. In the general heading, ICD-11 refers exclusively to sex and not to gender. This ambiguity may be due to the fact that this chapter, in addition to including gender incongruence, also contemplates sexual dysfunctions, which until now have also been considered mental disorders.

The terminology “Gender incongruence” is not something new, it was previously contemplated by the American Psychiatric Association when on February 10th, 2010 presented the draft of the fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)4. In an attempt to depathologize, it proposed the replacement of “Gender Identity Disorder” with “GI” (Gender Incongruence). This first draft didn’t meet the expectations of the trans people that harbored the hope that transsexuality would disappear from the international diagnostic classifications just like it happened with homosexuality11. The DSM-53 concludes with the substitution of the term “Gender Identity Disorder” by “Gender Dysphoria” that continues to belong to the chapter on mental disorders.

In an attempt to depathologize, it proposed the replacement of “Gender Identity Disorder” with “GI” (Gender Incongruence). This first draft didn’t meet the expectations of the trans people that harbored the hope that transsexuality would disappear from the international diagnostic classifications just like it happened with homosexuality11. The DSM-53 concludes with the substitution of the term “Gender Identity Disorder” by “Gender Dysphoria” that continues to belong to the chapter on mental disorders.

Although the term GI didn’t crystallize as a diagnosis, the DSM-5 puts emphasis on gender dysphoria both for defining gender dysphoria: “distress that may accompany the incongruence between felt or expressed gender and the gender assigned” and for describe the diagnostic criteria: “a marked incongruence between the felt gender and the primary and/or secondary sexual characteristics (or in young adolescents, the anticipation of secondary sexual characteristics)”.

For its part, the ICD 11 continues defining the GI as “a marked and persistent incongruence between the gender felt or experienced and the gender assigned to birth”12. This incongruity is manifested in at least two of the following criteria:

- Strong dislike or disagreement with primary or secondary sexual characteristics due to incongruence with the experienced gender.

- Strong desire to get rid of some of those sexual characteristics due to the incongruence with the experienced gender.

- Strong desire to have the primary or secondary sexual characteristics of the experienced gender.

- Strong desire to be treated and accepted as a person of the felt gender.

Compare to the DSM-5, the ICD-11 replaces the state of distress associated with that incongruence by the terms dislike or discomfort with less psychopathological connotations. In addition, only two diagnostic criteria must be met. This diagnosis could, therefore, be fulfilled without wanting to get rid of the primary and secondary sexual characteristics of the felt gender. Feeling dislike with the primary or secondary sexual characteristics, along with the desire to be treated and accepted as a person of the felt gender, would be sufficient to make the diagnosis of GI and would not imply the desire to undergo medical-surgical interventions to achieve a gender confirmation.

Feeling dislike with the primary or secondary sexual characteristics, along with the desire to be treated and accepted as a person of the felt gender, would be sufficient to make the diagnosis of GI and would not imply the desire to undergo medical-surgical interventions to achieve a gender confirmation.

In the ICD-11 we find two specifiers: changes in the anatomy of the female genitals and changes in the anatomy of the male genitals. In the former , it includes eliminating the breasts (QF01.0) and eliminating the female genitals (QF01.10) and in the latter eliminating the male genitals (QF01.11). These changes would be codified in chapter 24, which refers to “Factors that influence health status or contact with health services”, an existing chapter in ICD-10 (chapter 21). ICD-11 includes in this chapter the demands made by a person who may or may not be ill and who goes to health services for a specific purpose, such as receiving attention or limited service due to a current condition or when there is a circumstance or problem that influences a person’s health status but is not in itself a current illness or injury.

The ICD-11, however, has not carried out the same process as homosexuality to completely depathologize transsexuality. GI continues to be part of a chapter of the manual and therefore of a diagnosis within sexual health13. On May 17, 1990 the WHO eliminated homosexuality from the chapter on mental disorders14 totally depathologizing the orientation of people without eliminating the right to health coverage through its inclusion in the section “other ICD-10 processes frequently associated with mental and behavioral alterations”. Chapter XXI “factors influencing health status and contact with health services” include the Z codes “counseling related to sexual attitude, behaviour and orientation” (Z70) where some demands of homosexuals could be included2. The WHO justifies have taken gender incongruence out from mental illness, first of all, because at present there is greater normalization and knowledge about the diversity and gender variants that separate them from mental illness. Secondly, by eliminating this condition from the mental disorders chapter, the stigma which in our culture is more associated with mental disorders decreases12,15. Finally, WHO intend s to justify the maintenance of this diagnosis by referring to the fact that, otherwise they would not be recipients of medical assistance interventions (harmonization and surgery) when they are demanded by these users. According to our point of view, this last argument, is possibly the least solid one since it could be questioned if we contemplate the possibility of including GI in other non-pathologizing processes that require medical-surgical interventions such as the assistance to pregnant women is considered16.

Secondly, by eliminating this condition from the mental disorders chapter, the stigma which in our culture is more associated with mental disorders decreases12,15. Finally, WHO intend s to justify the maintenance of this diagnosis by referring to the fact that, otherwise they would not be recipients of medical assistance interventions (harmonization and surgery) when they are demanded by these users. According to our point of view, this last argument, is possibly the least solid one since it could be questioned if we contemplate the possibility of including GI in other non-pathologizing processes that require medical-surgical interventions such as the assistance to pregnant women is considered16.

Although there are some issues that still need to be clarified regarding the GO in the ICD new version, we must not lose sight of the most relevant fact. The WHO has included the different variants of gender in normality as they are not considered a mental illness.

To depathologize transsexuality and reach the same destination as homosexuality, the ICD-11 takes a broader journey. First of all, it replaces the diagnosis of “transsexualism” by “GI”. Secondly, it no longer considers GI a mental disorder by eliminating it from the chapter on mental disorders. However, it makes an intermediate step by including GI in the chapter on sexual health.

After these reflections we will have to wait until 2019 when the ICD-11 will be presented in the World Health Assembly for adoption by the member states. This presentation will allow the different countries to plan how to use the new version, prepare the translations and train the health professionals until it comes into force in 20225.

References

- World Health Organization – WHO. Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades. 9ª ed. Ginebra: WHO, 1978. (trad. cast. Madrid: Meditor)

- World Health Organization – WHO Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades 10ª ed.

Ginebra: WHO, 1992. (trad. cast. Madrid: Meditor)

Ginebra: WHO, 1992. (trad. cast. Madrid: Meditor) - American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5ª ed. Development, 2010. Recuperado en junio de 2012 de: http://dsm5.org

- Fernández Rodríguez M. y Garcia-Vega E.” Surgimiento, evolución y dificultades del diagnóstico de transexualismo” (Emergente, evolution and dificultéis of the transsexualism diagnosis). Rev.Asoc. Esp. de Neuropsiq., 2012; 32(113): 103-119. D.L. M. 17149-1981 ISSN: 0211-5735.

- Christian Lindmeier (OMS) [Internet]. 18 Junio 2018. Centro de prensa Organización Mundial de la Salud. Available in: http://www.who.int/es/news-room/detail/17-06-2018-who-releases-new-international-classification-of-diseases-(icd-11)

- Suess A. La despatologización trans desde una perspectiva de derechos humanos. Ponencia presentada en Jornadas Feministas Estatales. Granada: Jornadas Feministas Estatales. 2009. Available in www.feministas.org/jornadas.

html.

html. - WPATH Board of Directors (2010). De-psychopathologisation statement released. (Citado en enero de 2012). Available in: https://www.wpath.org/policies

- Campaña Internacional Stop Trans Pathologization STP. (2013). Reflexiones de STP sobre el proceso de revisión de la CIE y la publicación del DSM-5. Available in: https://www.stp2012.info/Comunicado_STP_agosto2013.pdf

- World Health Organization-WHO Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades 11 draft, 2018. Available in: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

- Fernández Rodríguez M. “Sexo y género dos conceptos interdependientes”. Mosaico Nº 49. Septiembre. 2011; ISSN: 1887-0600: 53-58. DL: B-16180-2005

- Drescher J. Queer diagnoses: Parallels and contrasts in the history of homosexuality, gender variance, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010; 39: 427–460.

- Questions and answers WHO: changes in the classification of gender incongruence (transgender) in the new ICD-11.

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. - Reed GM, Drescher J, Krueger RB, et al. Revising the ICD-10 Mental and Behavioural Disorders classification of sexuality and gender identity based on current scientific evidence, best clinical practices, and human rights considerations. World Psychiatry. 2016; 15: 205–221.

- World Health Organization [Internet]. 15 May 2015. LGBT health sees progress and challenges 15 years after homosexuality ceased being considered a disease. Available in: https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=10964%3A2015-lgbt-health-sees-progress-and-challenges&catid=740%3Apress-releases&Itemid=1926&lang=es

- Drescher J, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Winter S. Minding the body: Situating gender diagnoses in the ICD-11. International Review of Psychiatry. 2012; 24(6): 568–577.

- Cochran SD, Drescher J, Kismodi E, et al. Proposed declassification of disease categories related to sexual orientation in ICD-11: Rationale and evidence from the Working Group on Sexual Disorders and Sexual Health.

Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2014; 92: 672–679.

Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2014; 92: 672–679.

Methodological problems of standards of medical care for persons with sexual identification disorders The text of the scientific article in the specialty “Other Medical Sciences”

UDC 159.922.77+616.89 (616.8-07)

Methodological problems of medical care standards with sexual identification disorders

G.E. Vvedensky, S.N. Matevosyan

Federal State Budgetary Institution “Federal Medical Research Center for Psychiatry and Narcology named after N.N. V.P. Serbsky" of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, City Psychoendocrinological Center - branch of the Federal State Budgetary Healthcare Institution "Psychiatric Clinical Hospital No. N.A. Alekseeva Department

health care of the city of Moscow

At the present time in Russia, of the legal documents regulating medical care for people with gender identity disorders, only the “Standard of primary health care for gender identity disorders in an outpatient setting of a neuropsychiatric dispensary (dispensary department, office )”, approved by order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation of December 20, 2012 N 1221 n. This document regulates the initial examination with the participation of various specialists: a psychiatrist, a sexologist, a psychotherapist, an endocrinologist, a medical psychologist, and also provides a list of drugs for hormone therapy for transsexualism. However, this document does not address a number of significant methodological problems of diagnosing and treating such conditions, and therefore the task of creating federal guidelines for providing medical care to such individuals seems to be highly relevant. This problem cannot be solved without the analysis of foreign experience. Of the documents concerning the consideration of this issue, the most significant are the international classifications of mental and behavioral disorders, as well as the Standards for Health Care for Transsexual, Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Individuals (JOS-7), published by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (2013).

This document regulates the initial examination with the participation of various specialists: a psychiatrist, a sexologist, a psychotherapist, an endocrinologist, a medical psychologist, and also provides a list of drugs for hormone therapy for transsexualism. However, this document does not address a number of significant methodological problems of diagnosing and treating such conditions, and therefore the task of creating federal guidelines for providing medical care to such individuals seems to be highly relevant. This problem cannot be solved without the analysis of foreign experience. Of the documents concerning the consideration of this issue, the most significant are the international classifications of mental and behavioral disorders, as well as the Standards for Health Care for Transsexual, Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Individuals (JOS-7), published by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (2013).

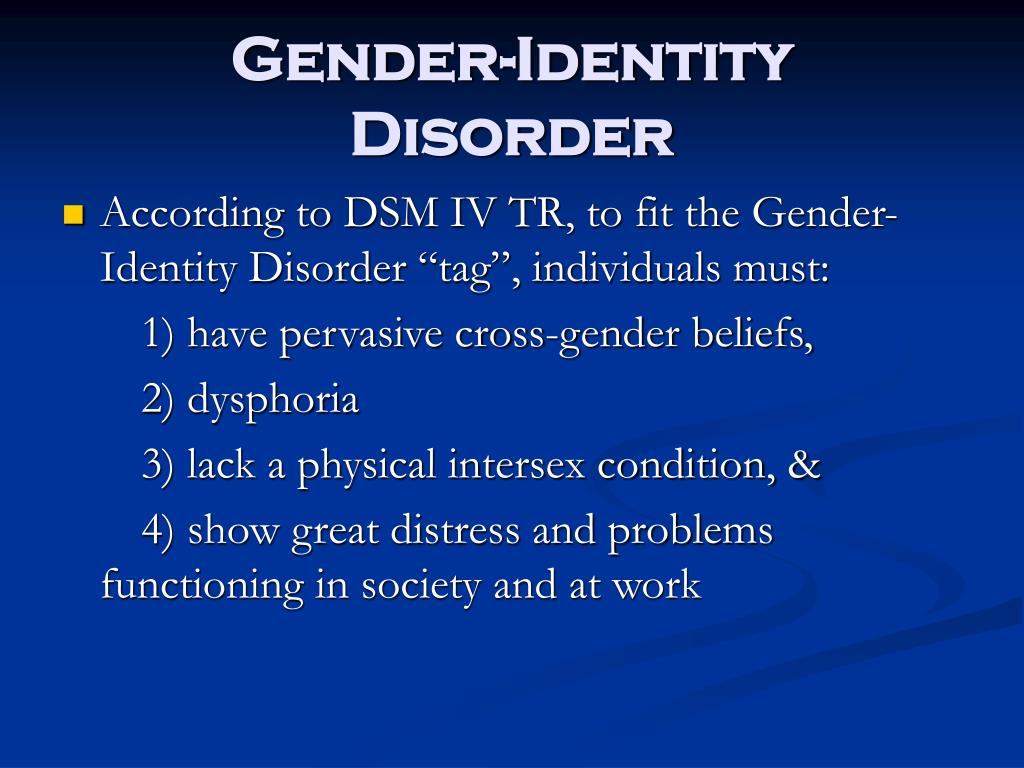

Analysis of ideas about gender identity disorders in the classifications of mental and behavioral disorders allows us to trace the main trends in their evolution. A new subclass of psychosexual disorders, "Gender Identity Disorders" (transsexualism in adults and gender identity disorder in children - CSO) first appeared in B$M-Sh. Gender identity disorders, including transsexualism, have been moved from the class of sexual disorders to the class of "disorders usually first manifesting in children and adolescents" in BSMSH-Z. In preparing the DSM-IV, gender identity disorders were first thought to be a distinct subclass following sexual disorders. As a result, they were returned to the group of psychosexual disorders, but their division into transsexualism and childhood identity disorder disappeared. In this classification, the same criteria are given for both conditions, and only subsequently is it recommended to code them as “gender identity disorder in children” (302.6) and “gender identity disorder in adolescents and adults” (302.85). In mature individuals, these disorders are also specified by the direction of sexual desire (for men, women, both, neither).

A new subclass of psychosexual disorders, "Gender Identity Disorders" (transsexualism in adults and gender identity disorder in children - CSO) first appeared in B$M-Sh. Gender identity disorders, including transsexualism, have been moved from the class of sexual disorders to the class of "disorders usually first manifesting in children and adolescents" in BSMSH-Z. In preparing the DSM-IV, gender identity disorders were first thought to be a distinct subclass following sexual disorders. As a result, they were returned to the group of psychosexual disorders, but their division into transsexualism and childhood identity disorder disappeared. In this classification, the same criteria are given for both conditions, and only subsequently is it recommended to code them as “gender identity disorder in children” (302.6) and “gender identity disorder in adolescents and adults” (302.85). In mature individuals, these disorders are also specified by the direction of sexual desire (for men, women, both, neither). Disappeared from DSM-IV was such a classification unit that existed in DSM-III-R as “gender identity disorder in adolescents and adults of a non-transgender type”, which described states of discomfort from experiencing the undesirability of one’s gender, accompanied by dressing and appropriate behavior, but without the requirements of surgical and hormonal correction. The DSM-IV, however, included a subheading of "unspecified gender identity disorders", which describes intersex conditions (eg, androgen insensitivity syndrome or congenital adrenal hyperplasia) associated with gender dysphoria; transient, stress-related dressing; persistent preoccupation with thoughts of castration or penectomy without desire to acquire the sexual characteristics of the other sex. Special mention

Disappeared from DSM-IV was such a classification unit that existed in DSM-III-R as “gender identity disorder in adolescents and adults of a non-transgender type”, which described states of discomfort from experiencing the undesirability of one’s gender, accompanied by dressing and appropriate behavior, but without the requirements of surgical and hormonal correction. The DSM-IV, however, included a subheading of "unspecified gender identity disorders", which describes intersex conditions (eg, androgen insensitivity syndrome or congenital adrenal hyperplasia) associated with gender dysphoria; transient, stress-related dressing; persistent preoccupation with thoughts of castration or penectomy without desire to acquire the sexual characteristics of the other sex. Special mention

a marked sense of inadequacy regarding sexual activities or other characteristics associated with the presented standards of masculinity or femininity.

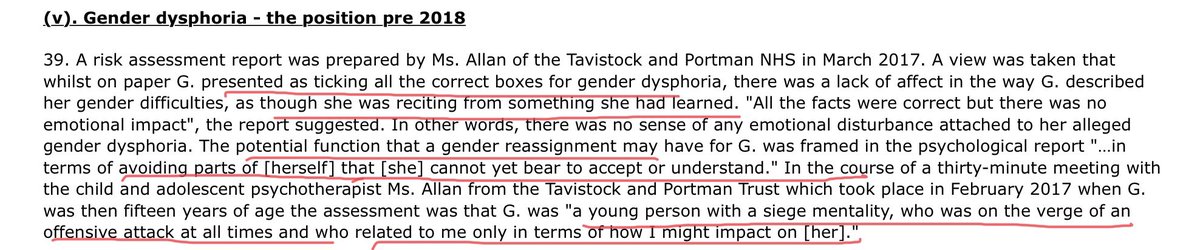

In the ICD-10, under the heading "gender identity disorders", transsexualism was singled out, criteria for gender identity disorders in children and dual role transvestism are specified separately. Zucker et al. [3] indicate that in developing this classification, the Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders Sub-Working Group provided an opinion on whether to retain the diagnosis in the DSM-5 at all. Some transgender activists and some clinicians wanted the diagnosis to be removed entirely, explaining that gender identity disorder is not a mental disorder. Their arguments for removal cited the same reasons that led to the removal of homosexuality at 1973 of the DSM-II. Transsexualism or gender identity disorder is presented to them as nothing more than a variant of the norm of cisgender identity, and its presence in the DSM contributes to stigmatization, and, in fact, there is nothing "wrong" in the mismatch of gender identity with birth sex. The subworking group's recommendations to retain the diagnosis were based on at least two key considerations: access to care and a new perspective on diagnosis. If there is no psychiatric diagnosis, access to care, including insurance coverage for gender reassignment surgery, will be at risk.

Zucker et al. [3] indicate that in developing this classification, the Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders Sub-Working Group provided an opinion on whether to retain the diagnosis in the DSM-5 at all. Some transgender activists and some clinicians wanted the diagnosis to be removed entirely, explaining that gender identity disorder is not a mental disorder. Their arguments for removal cited the same reasons that led to the removal of homosexuality at 1973 of the DSM-II. Transsexualism or gender identity disorder is presented to them as nothing more than a variant of the norm of cisgender identity, and its presence in the DSM contributes to stigmatization, and, in fact, there is nothing "wrong" in the mismatch of gender identity with birth sex. The subworking group's recommendations to retain the diagnosis were based on at least two key considerations: access to care and a new perspective on diagnosis. If there is no psychiatric diagnosis, access to care, including insurance coverage for gender reassignment surgery, will be at risk. In order to preserve the diagnosis, the DSM-5 introduced a new way of looking at the problem, in which "identity" itself was not seen as a sign of a mental disorder. Rather, it was a discrepancy between the perceived sex and the officially established one (usually at birth), which led to distress and/or deterioration, which was the main manifestation.0003

In order to preserve the diagnosis, the DSM-5 introduced a new way of looking at the problem, in which "identity" itself was not seen as a sign of a mental disorder. Rather, it was a discrepancy between the perceived sex and the officially established one (usually at birth), which led to distress and/or deterioration, which was the main manifestation.0003

diagnosis. Attention is also drawn to the mention in the PD criteria of “a strong conviction that one has typical feelings and reactions of the opposite sex (or any other sex that is different from the documented one). Assigning oneself as an individual to some other gender other than male or female may not be an expression of the autonomy of the individual and his freedom of expression, as emphasized by SOC-7, but also a symptom of a mental disorder.

In preparing the ICD-11, one of the proposals was to move the PD-related diagnoses from the ICD-10, sexual dysfunctions and paraphilias, from the section “mental and behavioral disorders” to a new section, temporarily called “conditions related to sexual health”, with a change in the label DSM-5 "gender dysphoria" to "gender mismatch". Such a suggestion seems partly based on the argument that such a section would be indifferent to how one way or another gender inconsistency would be better positioned as a psychiatric or non-psychiatric condition. K.Zucker et al. [3] note that retaining this section in ICD-11 would, in theory, allow public health systems or private insurers to continue to provide coverage and thus not threaten access to care for clients unable to pay out of pocket.

Such a suggestion seems partly based on the argument that such a section would be indifferent to how one way or another gender inconsistency would be better positioned as a psychiatric or non-psychiatric condition. K.Zucker et al. [3] note that retaining this section in ICD-11 would, in theory, allow public health systems or private insurers to continue to provide coverage and thus not threaten access to care for clients unable to pay out of pocket.

SOC-7 postulates that “a disorder is a description of something a person may be struggling with, not a description of the person or their identity. Thus, transsexuals, transgenders, and gender non-conforming individuals are not inherently sick. Rather, the distress of gender dysphoria, when present, is a problem that can be diagnosed and for which many treatment options are available. The existence of a diagnosis for such dysphoria often facilitates access to medical care.”

Such an approach to the definition of the disease leads to the exclusion of all variants from mental disorders with no criticism of the disease, which is already expressed in relation to syntonic forms of paraphilia.

SOC-7 removed the previous requirement that the diagnosis of PD and any associated psychopathology be made by mental health professionals. According to this document, any health care professional, properly trained in the field of mental health, and competent in the assessment of gender dysphoria can make these diagnoses and make any recommendations for treatment that depend on it. As pointed out by Kicker et al. [3], this change, intended to reduce barriers to care, may inadvertently lead to underdiagnosis of comorbid psychopathology.

Summing up, we can state two trends in the changes in classifications. The first one is expressed in the avoidance of the pathogenetic unity of various variants of gender dysphoria and gender identity disorders, the second - in fact, in the refusal to classify it as a mental disorder, while its preservation in the classification of the latter is due to considerations that have no clinical grounds.

The state of the issue of comorbidity of gender dysphoria and other mental disorders also follows from the latest trend. KZucker et al.[3] in their review article, citing data from various researchers, they conclude that psychopathological comorbidity is much more common in adults with PD than in the general population, affective and anxiety disorders are especially likely. SOC-7 mentions that, "as in children, the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder is higher in clinic referred adolescents with gender dysphoria than in other adolescents." Some studies have shown an increased incidence of personality disorders in individuals with PD. Finally, there is a group of studies that revealed a low, compared with the general population, occurrence of comorbid pathology. Many studies have significant limitations on the evidential strength of their findings. These include the use of small and potentially unrepresentative samples and the frequent use of short, self-administered questionnaires rather than structured clinical interviews. Summing up, the authors note that the use of a structured psychiatric interview during the examination significantly increases the frequency of detected mental disorders.

KZucker et al.[3] in their review article, citing data from various researchers, they conclude that psychopathological comorbidity is much more common in adults with PD than in the general population, affective and anxiety disorders are especially likely. SOC-7 mentions that, "as in children, the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder is higher in clinic referred adolescents with gender dysphoria than in other adolescents." Some studies have shown an increased incidence of personality disorders in individuals with PD. Finally, there is a group of studies that revealed a low, compared with the general population, occurrence of comorbid pathology. Many studies have significant limitations on the evidential strength of their findings. These include the use of small and potentially unrepresentative samples and the frequent use of short, self-administered questionnaires rather than structured clinical interviews. Summing up, the authors note that the use of a structured psychiatric interview during the examination significantly increases the frequency of detected mental disorders.

KZucker et al. [3] note that the widespread view that prejudice and discrimination are the main cause of mental disorders in people with gender dysphoria remains unproven; it is not clear which comes first: either prejudice and discrimination lead to a greater likelihood of developing mental disorders, or mental disorders lead to a greater likelihood of experiencing or perceiving prejudice and discrimination. According to the authors of this article, the second option is also possible.

Related to this situation is the SOC-7 statement about the unethical and useless

conduct of psychotherapy aimed at trying to adapt the patient to his biological field. KZucker et al. [3] express doubts about the correctness of this point of view, emphasizing the possibility of such tactics being optimal in a number of cases.

Noteworthy is the surprising absence of patients with schizophrenia and schizotypal disorder among persons with PD according to the results of foreign researchers. According to Russian researchers [1], the share of such persons is about 32%. Among the possible reasons for this discrepancy may be the implicit attitude of mental health professionals to work with patients' complaints and insufficient attention to the peculiarities of their non-verbal and verbal behavior, which hinders the diagnosis of these disorders. Such an attitude seems to be related to the above understanding of a mental disorder, formulated in SOC-7, and ultimately leads to the lack of an adequate approach to assessing the role of gender dysphoria (gender role conflict) in the patient's maladaptation. This situation can suit both sides: patients who in most cases are convinced of the determining role of the problem of gender inconsistency in their life difficulties in the absence of criticism of the disease, and doctors for whom the diagnosis of an endogenous disorder poses difficult problems of relating gender dysphoria to it, as well as doubts. in the patient's ability to adequately assess his condition and predict the consequences of his behavior and treatment and rehabilitation measures.

According to Russian researchers [1], the share of such persons is about 32%. Among the possible reasons for this discrepancy may be the implicit attitude of mental health professionals to work with patients' complaints and insufficient attention to the peculiarities of their non-verbal and verbal behavior, which hinders the diagnosis of these disorders. Such an attitude seems to be related to the above understanding of a mental disorder, formulated in SOC-7, and ultimately leads to the lack of an adequate approach to assessing the role of gender dysphoria (gender role conflict) in the patient's maladaptation. This situation can suit both sides: patients who in most cases are convinced of the determining role of the problem of gender inconsistency in their life difficulties in the absence of criticism of the disease, and doctors for whom the diagnosis of an endogenous disorder poses difficult problems of relating gender dysphoria to it, as well as doubts. in the patient's ability to adequately assess his condition and predict the consequences of his behavior and treatment and rehabilitation measures.

In view of the problem under discussion, it is not surprising that about 20% of patients do not experience significant benefit from sex reassignment, and even after surgical correction for 10 years and beyond, patients showed a much higher prevalence of psychopathology and suicidality than age-sex-matched patients. parameters of control groups [3].

Summing up the above, we have to state that a pronounced tendency to depathologize gender dysphoria leads to a deterioration in the quality of medical care for such people, both in the diagnostic and in the treatment and rehabilitation plan, which should be taken into account when developing federal recommendations on sexual disorders. identification.

LITERATURE

Matevosyan S.N., Vvedensky G.E. Gender dysphoria (clinical and phenomenological features and therapeutic and rehabilitation aspects of the syndrome of "rejection" of sex. M .: MIA, 2012. Standards of care for transsexuals, transgenders and gender non-conforming individuals, version 7. World

World

Professional Association for the Health of Transsexuals, 2013.

Zucker K., Lawrence A., Kreukels B. Gender Dysphoria in Adults // Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2016 Vol. 12 P.20.1-20.31.

94

G.E. Vvedensky, S.N. Matevosyan

METHODOLOGICAL PROBLEMS OF CARE STANDARDS FOR PERSONS WITH GENDER ID DISORDERS

G.E. Vvedensky, S.N. Matevosyan

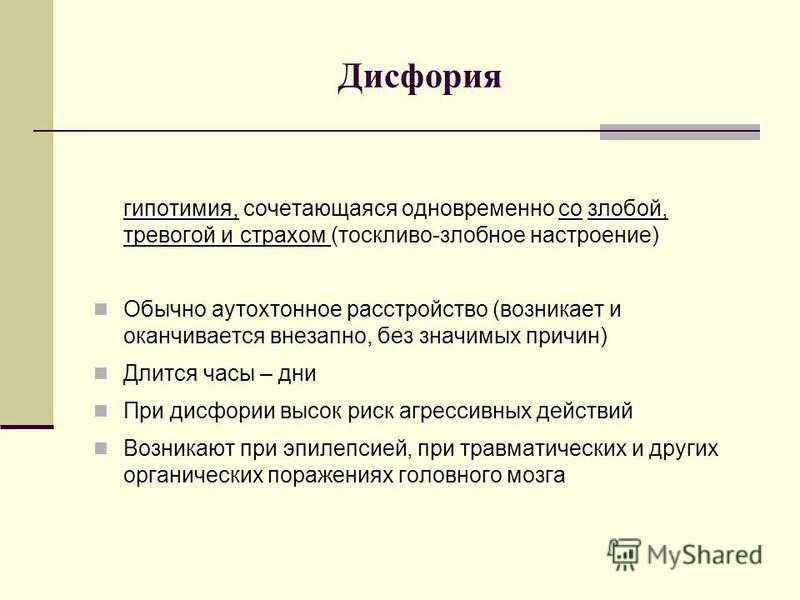

The main tendencies of ideas about gender identity disorders in the classifications of mental and behavioral disorders are analyzed. There are two trends in classification changes: in moving away from the pathogenetic unity of various variants of gender dysphoria (defined in DSM-5 as “affective/cognitive dissatisfaction of a person with their prescribed gender”) and gender identity disorders; in refusing to classify it as a mental disorder.

It is concluded that a pronounced tendency to depathologize gender dysphoria leads to a deterioration in the quality of medical care for such persons, both in terms of diagnostics and treatment and rehabilitation, which should be taken into account when developing federal recommendations on gender identity disorders.

Key words: gender identity disorders, gender dysphoria, standards of medical care.

METHODOLOGICAL CHALLENGES FOR STANDARDS OF CARE FOR PERSONS WITH GENDER

IDENTIFICATION DISORDERS

G.E. Vvedensky, S.N. Matevosyan

The authors analyze the tendencies in changing attitudes towards gender identification disorders in classifications of mental and behavioral disorders. They point to two trends in modern classifications: different variants of gender dysphoria (defined in DSM-5 as 'individual's affective/cognitive discontent with the assigned gender') and gender identification disorders are no longer uniformly associated with or predicted from the classical biological indicators ; gender dysphoria is not considered as a mental

disorder. The authors conclude that a strong tendency to demedicalization of gender dysphoria would result in a deterioration of health care for these persons, including both diagnosis and treatment, and it should be taken into account in the course of development of Federal guidelines on gender identification disorders.

Key words: gender identification disorders, gender dysphoria, standards of medical care V.P. Serbsky” of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation; e-mail: [email protected]

Matevosyan Stepan Narbeevich - Doctor of Medical Sciences, Head of the Psychoendocrinological Department (City Psychoendocrinological Center) N.A. Alekseev of the Department of Health of the City of Moscow "" Psychoneurological dispensary No. 2 "; e-mail: [email protected]

Modern approaches to the management of gender dysphoria from the position of an endocrinologist: a clinical observation | Volkova

Introduction

Currently, the world community pays more and more attention to the problem of discomfort and suffering for men and women in connection with forced compliance with sexual dimorphism. Back at 1979, when the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) was founded, the first Standards of Care for Persons with Gender Dysphoria/Gender Mismatch were published [1]. In subsequent years, the terminology and its application changed regularly, and today the classification system of the American Psychiatric Association has fixed the term "gender dysphoria" in the diagnosis of individuals who are dissatisfied with their assigned sex. Moreover, in the ICD-11, which entered into force in 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed the use of the term “gender mismatch” [2]. Thus, in the modern medical community, when describing the problem of gender dysphoria, the following terms are used:

In subsequent years, the terminology and its application changed regularly, and today the classification system of the American Psychiatric Association has fixed the term "gender dysphoria" in the diagnosis of individuals who are dissatisfied with their assigned sex. Moreover, in the ICD-11, which entered into force in 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed the use of the term “gender mismatch” [2]. Thus, in the modern medical community, when describing the problem of gender dysphoria, the following terms are used:

- “transgender” is an umbrella term for people whose behavior or expression does not match their birth sex;

- "gender dysphoria" (GD) - discomfort due to the discrepancy between the sex at birth and the gender identity of the individual;

- "transgender man" (FtM) - a biologically female person who identifies with the male sex and wants to be a man;

- "transgender woman" (MtF) - a biologically male person who identifies with the female sex and wants to be a woman;

- "sex reassignment" - medical and / or surgical treatment to adapt one's body to one's gender identity;

- "transition" - the period of time required to change the physical appearance, social role and documents to the opposite with respect to the biological sex [3].

Since 2018, a regulation has been in force in the Russian Federation, according to which a person wishing to undergo a sex reassignment procedure must obtain an opinion from a commission consisting of a psychiatrist, a medical psychologist and a sexologist, confirming the diagnosis of "gender dysphoria", as a result of which it is possible to change documents and conduct medical gender reassignment (Order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation of October 23, 2017 No. 850n “On approval of the form and procedure for issuing a document on gender reassignment by a medical organization”, registered 19.01.2018 No. 49695). It should be noted that all medical sex reassignment procedures are paid exclusively from the patients' own funds, which, in our opinion, is not entirely fair.

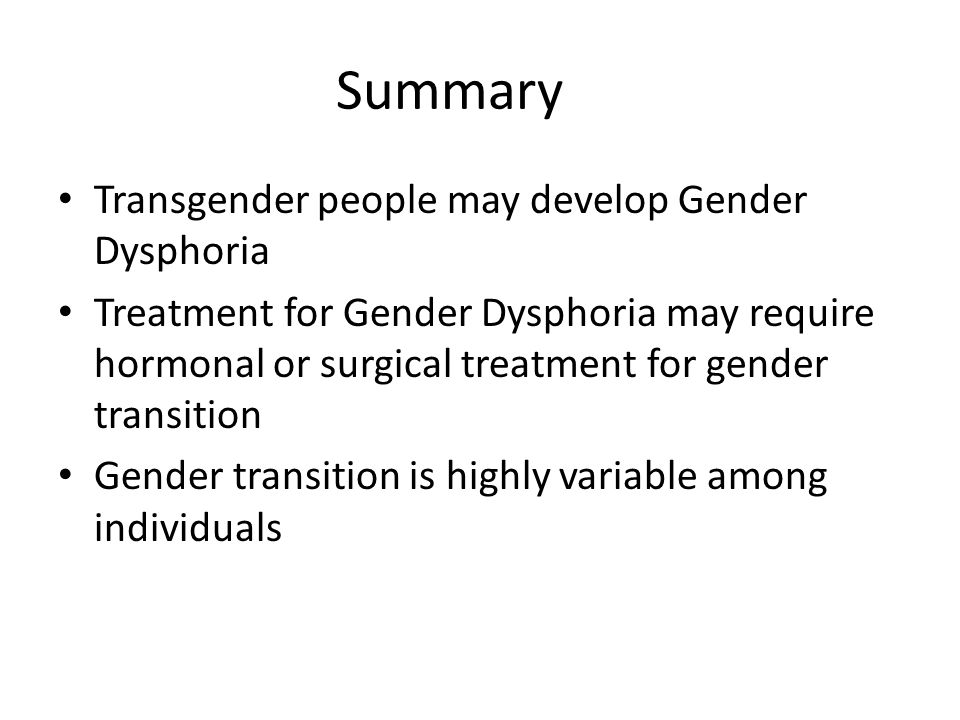

One of the most difficult tasks in helping people with gender dysphoria is gender reassignment, which, of course, is a multidisciplinary one, and the success of its solution depends on the effective cooperation of specialists qualified in helping these patients, such as a psychiatrist, an endocrinologist and surgeon. So, in addition to a direct diagnostic examination, patients will need psychotherapy or psychological counseling, hormone replacement therapy, and in some cases, surgical sex change. Given that gender dysphoria may hide other conditions that are similar in symptomatology, most of the clinical recommendations of professional communities, including WPATH and the Endocrinological Society (ES), indicate the need for diagnosis only by a mental health professional with a high level of competence in using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5 and ICD), and insist on differential diagnosis of gender dysphoria/gender nonconformity with other conditions that have similar clinical manifestations [1][3].

So, in addition to a direct diagnostic examination, patients will need psychotherapy or psychological counseling, hormone replacement therapy, and in some cases, surgical sex change. Given that gender dysphoria may hide other conditions that are similar in symptomatology, most of the clinical recommendations of professional communities, including WPATH and the Endocrinological Society (ES), indicate the need for diagnosis only by a mental health professional with a high level of competence in using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5 and ICD), and insist on differential diagnosis of gender dysphoria/gender nonconformity with other conditions that have similar clinical manifestations [1][3].

If we talk about the stages of gender reassignment, then the first and most significant is the confirmation of the diagnosis of gender dysphoria by a psychiatrist. The success of the entire sex reassignment process largely depends on the correctness of this stage. And only at the second stage, the patient can be referred to an endocrinologist for hormonal therapy, the purpose of which is to reduce the level of endogenous hormones to reduce the clinical manifestations of secondary sexual characteristics of the current biological sex, as well as to replace the desired sex with exogenous hormones [3].

And only at the second stage, the patient can be referred to an endocrinologist for hormonal therapy, the purpose of which is to reduce the level of endogenous hormones to reduce the clinical manifestations of secondary sexual characteristics of the current biological sex, as well as to replace the desired sex with exogenous hormones [3].

FtM transgender regimens to stimulate masculinization are based on the principles of hormonal treatment of hypogonadal men and may include the use of parenteral and transdermal testosterone preparations [4]. At the same time, the expected clinical changes appear after some time. So, in the first 6 months of therapy, there may be a cessation of menstruation, increased hair growth in androgen-dependent areas, an increase in libido, the appearance of acne and an increase in muscle mass. While a change in the timbre of the voice, clitoromegaly, and in some cases, baldness of the scalp may appear towards the end of the first year of therapy [4].

The treatment regimen for MtF transgenders is more complex, since progestins, GnRH agonists, and spironolactone may be required to suppress testosterone levels along with physiological doses of estrogens, which are taken orally or transdermally, due to their pronounced antiandrogenic activity [5]. Clinical changes occurring in the first year of therapy include reduced body and facial hair growth, decreased libido, decreased spontaneous erections, and redistribution of fat mass [5]. During the second year after the start of hormone therapy, the growth and development of the mammary glands begins, however, it should be borne in mind that these changes are individual in nature [6][7].

Clinical changes occurring in the first year of therapy include reduced body and facial hair growth, decreased libido, decreased spontaneous erections, and redistribution of fat mass [5]. During the second year after the start of hormone therapy, the growth and development of the mammary glands begins, however, it should be borne in mind that these changes are individual in nature [6][7].

It is important to remember that in the process of hormone therapy, transgender people often have high expectations regarding clinical changes and the speed of their development, as a result of which they seek to enhance them by disrupting the regimen of hormonal drugs. This approach can lead to the development of serious adverse effects, the prevention of which is also an important task for the endocrinologist. Among the possible risks of hormone therapy are thromboembolic disease, macroprolactinoma, breast cancer, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and gallstone disease during estrogen therapy. At the same time, erythrocytosis, severe liver dysfunction, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, arterial hypertension, breast or uterine cancer may occur during testosterone treatment.

At the same time, erythrocytosis, severe liver dysfunction, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, arterial hypertension, breast or uterine cancer may occur during testosterone treatment.

To prevent adverse effects, regular monitoring of weight and blood pressure, clinical changes and potential adverse effects in response to treatment, as well as laboratory monitoring of sex steroid hormone levels every 3 months during the first year of therapy, and then once or twice per year [3].

The standard monitoring plan for FtM transgender people includes follow-up every 3 months during the first year of therapy and then 1-2 times a year to assess virilization and prevent adverse events. The main laboratory parameters to be monitored include total testosterone, which should be measured every 3 months until the male norm (400-700 ng / dl) is reached, hematocrit and hemoglobin, which are determined before starting therapy, and then every 3 months for a year. Blood pressure, weight and lipid profile should also be assessed at each visit. In other words, the main monitoring issues are maintaining the level of total testosterone in the physiological range for men and preventing adverse events such as erythrocytosis, sleep apnea syndrome, excessive weight gain, arterial hypertension, and lipid metabolism disorders [3].

In other words, the main monitoring issues are maintaining the level of total testosterone in the physiological range for men and preventing adverse events such as erythrocytosis, sleep apnea syndrome, excessive weight gain, arterial hypertension, and lipid metabolism disorders [3].

MtF transgender patients are followed up every 3 months during the first year of hormone therapy, and then 1-2 times a year to assess feminization and prevent adverse events. Since an overdose of estrogens due to their significant increase in blood plasma can lead to a sharp increase in the risk of thromboembolism, liver dysfunction and the development of arterial hypertension, the level of estradiol should not exceed the values typical for young women (100-200 pg / ml). Among other indicators, special attention should be paid to total testosterone, the values of which should not exceed 50 ng / dl, and serum electrolytes, in particular potassium when taking spironolactone, which must be assessed once every 3 months during the first year of therapy [3]. For timely detection of possible complications, a study of bone mineral density at a high risk of osteoporotic fractures, screening for oncological diseases and thrombophilia in patients with a aggravated anamnesis or heredity is carried out [8].

For timely detection of possible complications, a study of bone mineral density at a high risk of osteoporotic fractures, screening for oncological diseases and thrombophilia in patients with a aggravated anamnesis or heredity is carried out [8].

It should be noted that up to 20% of cases of MtF transgenders may have elevated prolactin levels, which is probably associated with the growth of lactotrophic pituitary cells and, as a result, an increase in the anterior lobe [9]. At the same time, some patients may take psychotropic drugs, which in turn can also affect the level of prolactin [10].

The last and most important step in the treatment is surgery. It should be noted that transgender people do not always choose this treatment, and in some cases they can successfully live in their preferred gender role without genital surgery. To date, there are three categories of gender confirmation surgeries for MtF transgenders: facial feminization for more feminine features, breast augmentation, and genital reconstruction, which include bilateral orchiectomy, penectomy, and vaginoplasty. For FtM patients, surgical treatment options include breast reduction surgery, oophorectomy, hysterectomy, and/or vaginectomy. phalloplasty and metoidioplasty. Due to its high invasiveness and irreversibility, genital surgery should be performed only after hormone therapy and living in the patient's preferred gender role for at least one year. It is also important to make sure that gender dysphoria is persistent, that the patient is able to make informed decisions, and that all associated medical and mental problems are compensated [1]. According to the literature, cases of postoperative disappointment in patients are most often provoked by the presence of concomitant psychiatric pathology, as well as the lack of support from others. Therefore, it is very important to try to avoid high patient expectations and to assess in a timely manner the potential psychological and social risks from an unsuccessful medical intervention by providing full information about the possibilities and limitations of various treatment options [3].

For FtM patients, surgical treatment options include breast reduction surgery, oophorectomy, hysterectomy, and/or vaginectomy. phalloplasty and metoidioplasty. Due to its high invasiveness and irreversibility, genital surgery should be performed only after hormone therapy and living in the patient's preferred gender role for at least one year. It is also important to make sure that gender dysphoria is persistent, that the patient is able to make informed decisions, and that all associated medical and mental problems are compensated [1]. According to the literature, cases of postoperative disappointment in patients are most often provoked by the presence of concomitant psychiatric pathology, as well as the lack of support from others. Therefore, it is very important to try to avoid high patient expectations and to assess in a timely manner the potential psychological and social risks from an unsuccessful medical intervention by providing full information about the possibilities and limitations of various treatment options [3].

Thus, the currently developed algorithms of medical care for people with gender dysphoria describe in detail the mechanism of gender reassignment, the contribution of various specialists to this process, as well as possible risks and methods for their prevention. Only careful observance of them without violating the phasing can lead to the successful achievement of the final result. While any deviations from these algorithms due to objective and subjective reasons entail serious life-threatening consequences.

Description of clinical cases

Case 1. Patient MtF P., aged 25, applied for hormonal therapy for gender reassignment. It should be noted that the consultation was attended by the patient's mother, who actively supported him and participated in the discussion of the anamnesis, as well as the treatment plan.

Patient history. Mental illness in the family denies. Patient MtF is the only child in the family, he was unsociable, calm, and obedient by nature. After puberty, libido was reduced, he did not show much interest in girls. At the age of 15, there was discomfort from wearing men's clothing. Sexual life appeared from 19years. Discomfort from not accepting one's gender began to grow. At the age of 21, he began to search for information about this topic on the Internet. There was a strong desire to change their gender to female. At the age of 23, he turned to a psychiatrist, who for a year carried out a differential diagnosis of gender dysphoria with other conditions that have similar clinical manifestations. As a result, the decision of the medical commission issued a conclusion: “Based on the anamnesis, dynamic observation, and objective mental status, a violation of gender identification in the form of Transsexualism (F64.0) is detected, no data for the endogenous process were found. There are no mental status contraindications to surgical gender reassignment and passport sex change.” Patient MtF was also referred to an endocrinologist for hormonal therapy.

After puberty, libido was reduced, he did not show much interest in girls. At the age of 15, there was discomfort from wearing men's clothing. Sexual life appeared from 19years. Discomfort from not accepting one's gender began to grow. At the age of 21, he began to search for information about this topic on the Internet. There was a strong desire to change their gender to female. At the age of 23, he turned to a psychiatrist, who for a year carried out a differential diagnosis of gender dysphoria with other conditions that have similar clinical manifestations. As a result, the decision of the medical commission issued a conclusion: “Based on the anamnesis, dynamic observation, and objective mental status, a violation of gender identification in the form of Transsexualism (F64.0) is detected, no data for the endogenous process were found. There are no mental status contraindications to surgical gender reassignment and passport sex change.” Patient MtF was also referred to an endocrinologist for hormonal therapy. At the age of 24, Androkur 25 mg per day and Estrogel 0.6 mg/g per day were prescribed, which the patient received for 6 months. Against the background of the therapy, the desired effect was not obtained, and the levels of total testosterone (33 nmol / l) and estradiol (16.8 pg / ml), characteristic of the male sex, were also maintained, in connection with which the patient began to search the Internet for alternative methods of sex correction. Due to the lack of expected results, the patient again turned to the endocrinologist.

At the age of 24, Androkur 25 mg per day and Estrogel 0.6 mg/g per day were prescribed, which the patient received for 6 months. Against the background of the therapy, the desired effect was not obtained, and the levels of total testosterone (33 nmol / l) and estradiol (16.8 pg / ml), characteristic of the male sex, were also maintained, in connection with which the patient began to search the Internet for alternative methods of sex correction. Due to the lack of expected results, the patient again turned to the endocrinologist.

An objective examination revealed a male-type physique, overweight (height - 172 cm, weight - 84 kg, body mass index - 28 kg/m2). Vesicular breathing in the lungs, no wheezing. Heart sounds are clear, rhythmic. Blood pressure - 120/75 mm Hg. Art., heart rate - 74 beats / min. Testicular volume was less than 10 ml. The patient also reported a decrease in libido and a decrease in spontaneous erections. Taking into account the absence of pronounced specific effects of gender reassignment, the ongoing hormonal therapy was adjusted. So, the dose of Androcur was increased to 50 mg per day, and Estrogel was replaced by Proginova 4 mg per day. It should be noted that before the correction of hormone therapy in the MtF patient, the risks of developing complications of this treatment were assessed for the first time. Risk factors for thromboembolic disease were identified, among which only elevated BMI was identified. In addition, the target level of prolactin was revealed, as well as normal ALT and AST levels. According to the care algorithms for individuals with gender dysphoria, a follow-up plan for the MtF patient was developed, which included visits every 3 months for 1 year to assess the effectiveness and safety of hormone therapy.

So, the dose of Androcur was increased to 50 mg per day, and Estrogel was replaced by Proginova 4 mg per day. It should be noted that before the correction of hormone therapy in the MtF patient, the risks of developing complications of this treatment were assessed for the first time. Risk factors for thromboembolic disease were identified, among which only elevated BMI was identified. In addition, the target level of prolactin was revealed, as well as normal ALT and AST levels. According to the care algorithms for individuals with gender dysphoria, a follow-up plan for the MtF patient was developed, which included visits every 3 months for 1 year to assess the effectiveness and safety of hormone therapy.

After 3 months at a routine examination, there was a slight redistribution of fat mass and breast growth. The rest of the objective data remained unchanged. According to the patient MtF, there was a decrease in libido and a decrease in spontaneous erections. According to the laboratory examination, a decrease in the level of total testosterone (0. 73 nmol / l) was revealed. There was also an increase in estradiol levels (87.4 pg / ml), however, the values \u200b\u200bwere not included in the target range for transgender women (100-200 pg / ml), and therefore the dose of Progynova was increased to 6 mg per day.

73 nmol / l) was revealed. There was also an increase in estradiol levels (87.4 pg / ml), however, the values \u200b\u200bwere not included in the target range for transgender women (100-200 pg / ml), and therefore the dose of Progynova was increased to 6 mg per day.

At the next examination after another 3 months, a pronounced redistribution of fat mass attracted attention, slight breast growth continued. There was also a slight decrease in muscle mass and oiliness of the skin. Patient MtF reported a lack of libido and spontaneous erections. According to the laboratory examination, the same reduced level of total testosterone (0.86 nmol / l) was detected. It was also noted that the target values of estradiol (103.2 pg / ml) were achieved. However, the patient was dissatisfied with the result, wanted a more rapid development of the effects of hormonal therapy and insisted on increasing the dosage of the drugs. It should be noted that the patient has already received Androkur and Proginova in the maximum allowable doses. This information was described in great detail to the MtF patient, as well as the possible risks of increasing the dosages of hormonal drugs.

This information was described in great detail to the MtF patient, as well as the possible risks of increasing the dosages of hormonal drugs.

Patient did not show up for the next follow-up after 3 months. Six months later, the mother of the MtF patient came to the appointment with her son's medical documentation. It turned out that due to dissatisfaction with the result, the MtF patient independently began to adjust hormone therapy, based on data obtained from the Internet. So, the medication was started without controlling the level of hormones. Patient MtF developed deep vein thrombosis 2 months later and discontinued treatment. According to the mother, the patient refuses further therapy due to fear for his condition after suffering deep vein thrombosis, despite the continuing discomfort from not accepting his gender.

Clinical case 2. Patient FtM P., 23 years old, applied for hormonal therapy for gender reassignment.

Patient history. Mental illness in the family denies. The FtM patient was the only child in the family, her character was calm, obedient, moderately sociable. Since childhood, she spent more time in the company of boys. At the time of puberty, she felt extremely uncomfortable, noted the rejection of the beginning of the menstrual cycle. From the age of 16 she began to wear men's clothes, put on a corset to hide her breasts. Does not live a sexual life. Discomfort from not accepting her gender began to grow, there was a strong desire to change her gender to male, and at the age of 21 she turned to a psychiatrist. After the differential diagnosis of gender dysphoria was carried out, a medical commission was held, which issued a conclusion: “Based on the anamnesis, dynamic observation, and objective mental status, a violation of gender identification in the form of Transsexualism (F64.0) is detected, data for the endogenous process were not found. There are no mental status contraindications to surgical gender reassignment and passport sex change.

Mental illness in the family denies. The FtM patient was the only child in the family, her character was calm, obedient, moderately sociable. Since childhood, she spent more time in the company of boys. At the time of puberty, she felt extremely uncomfortable, noted the rejection of the beginning of the menstrual cycle. From the age of 16 she began to wear men's clothes, put on a corset to hide her breasts. Does not live a sexual life. Discomfort from not accepting her gender began to grow, there was a strong desire to change her gender to male, and at the age of 21 she turned to a psychiatrist. After the differential diagnosis of gender dysphoria was carried out, a medical commission was held, which issued a conclusion: “Based on the anamnesis, dynamic observation, and objective mental status, a violation of gender identification in the form of Transsexualism (F64.0) is detected, data for the endogenous process were not found. There are no mental status contraindications to surgical gender reassignment and passport sex change. ” The FtM patient independently started hormone therapy with Nebido 1000 mg once every 3 months. After 3 months, at the age of 22, without evaluating the effectiveness of the therapy, neither an endocrinologist nor a psychiatrist performed a mastectomy with the formation of a male breast. Due to the peculiarities of the pharmacodynamic action of Nebido, in particular, the gradual decrease in the clinical effect of testosterone after injection, the FtM patient turned to an endocrinologist to correct hormone therapy.

” The FtM patient independently started hormone therapy with Nebido 1000 mg once every 3 months. After 3 months, at the age of 22, without evaluating the effectiveness of the therapy, neither an endocrinologist nor a psychiatrist performed a mastectomy with the formation of a male breast. Due to the peculiarities of the pharmacodynamic action of Nebido, in particular, the gradual decrease in the clinical effect of testosterone after injection, the FtM patient turned to an endocrinologist to correct hormone therapy.

An objective examination revealed a male-type physique, overweight (height - 173 cm, weight - 62 kg, body mass index - 20.7 kg/m2). Vesicular breathing in the lungs, no wheezing. Heart sounds are clear, rhythmic. Blood pressure - 105/70 mm Hg, heart rate - 68 bpm. Single acne and hair growth are noted on the face. There are scars on the chest from a mastectomy. According to the FtM patient, the menstrual cycle has been absent for 2 years. To assess the risks of ongoing therapy, ALT, AST and hematocrit were determined, which turned out to be within the normal range. The FtM patient was prescribed Androgel 1% 5g per day. In addition, a follow-up plan was developed for the patient, which included visits every 3 months for 1 year to evaluate the efficacy and safety of hormone therapy.

The FtM patient was prescribed Androgel 1% 5g per day. In addition, a follow-up plan was developed for the patient, which included visits every 3 months for 1 year to evaluate the efficacy and safety of hormone therapy.

After 3 months at the scheduled examination, the objective data remained unchanged. According to the laboratory examination, a low level of total testosterone (0.73 ng / ml) and an elevated level of estradiol (126 pg / ml) were detected for transgender men. Despite this, therapy at the previous dose was continued. At the same time, lipid metabolism, ALT, AST and hematocrit were within the target values.

At the next examination after another 3 months, coarsening of the voice appeared. At the same time, according to the results of laboratory examination, there was an increase in the level of total testosterone (4.13 ng / ml), while the level of estradiol (42 pg / ml) entered the target range for transgender men. Conducted hormonal therapy was continued without changes.

At the next examination after 3 months, the FtM patient noted a significant change in her condition. In particular, body hair growth and increased muscle mass appeared despite similar levels of total testosterone (4.43 ng/ml) and estradiol (47 pg/ml). Indicators of lipid metabolism, ALT, AST and hematocrit remained within the target values.

At the next examination 1 year after the start of Androgel therapy, redistribution of fat was added to the clinical effects. The FtM patient noted excellent health and reported that she had changed her gender in her passport. According to the laboratory examination, there was an increase in the level of total testosterone (6.77 ng / ml) and the same level of estradiol (43 pg / ml).

Taking into account the positive effect of the ongoing hormonal therapy, the comfort of staying in gender identity, gender reassignment surgery was recommended. Against the background of ongoing hormone therapy, a hysterectomy and oophorectomy were performed, and reconstruction of the fixed part of the urethra in conjunction with phalloplasty was also planned.

Discussion

Using these clinical cases as examples, we wanted to demonstrate what different results of hormone therapy can be achieved depending on compliance or non-compliance with the developed treatment algorithms for people with gender dysphoria. So, in clinical case No. 1, the patient received adequate hormonal therapy in the maximum allowable doses, against which a positive trend was noted. Moreover, before the start of treatment, the risks of complications were assessed, and the developed follow-up plan made it possible to control both the clinical effect of therapy and possible side effects, which were discussed at each examination. However, due to the characteristics of the patient, his formed opinion about the possible results of treatment obtained from the Internet, the patient decided to self-correct hormone therapy. As a result, the patient developed deep vein thrombosis, and therefore all drugs were discontinued, and, as a result, the achieved indicators were lost, despite the continued discomfort of not accepting one's gender. Thus, the deviation from the medical care algorithms for people with gender dysphoria, due to objective and subjective reasons, led to serious life-threatening consequences.

Thus, the deviation from the medical care algorithms for people with gender dysphoria, due to objective and subjective reasons, led to serious life-threatening consequences.

At the same time, in clinical case No. 2, despite the late mastectomy due to the lack of evaluation of the effectiveness of the treatment and the short period from the start of the drug administration, in general, the patient was prescribed adequate hormonal therapy and a follow-up plan was developed, which was fully observed. As a result, clinical and laboratory sex changes were achieved to the desired, comfort from staying in one's gender identity, and, as a result, hysterectomy and oophorectomy were successfully performed, further surgical sex correction was planned. Thus, compliance with the medical care algorithms for persons with gender dysphoria allowed the patient to obtain the desired treatment outcome without significant complications. However, such patients require mandatory dynamic monitoring.

Conclusion