Fear of consciousness

Extremely Conscious and Incredibly Scared of It

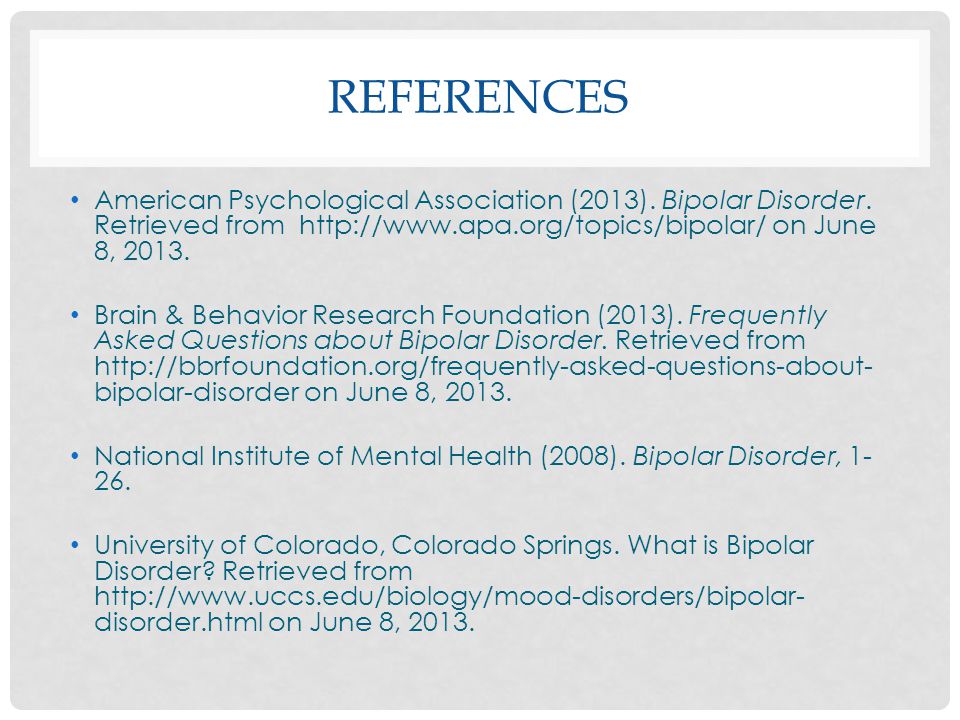

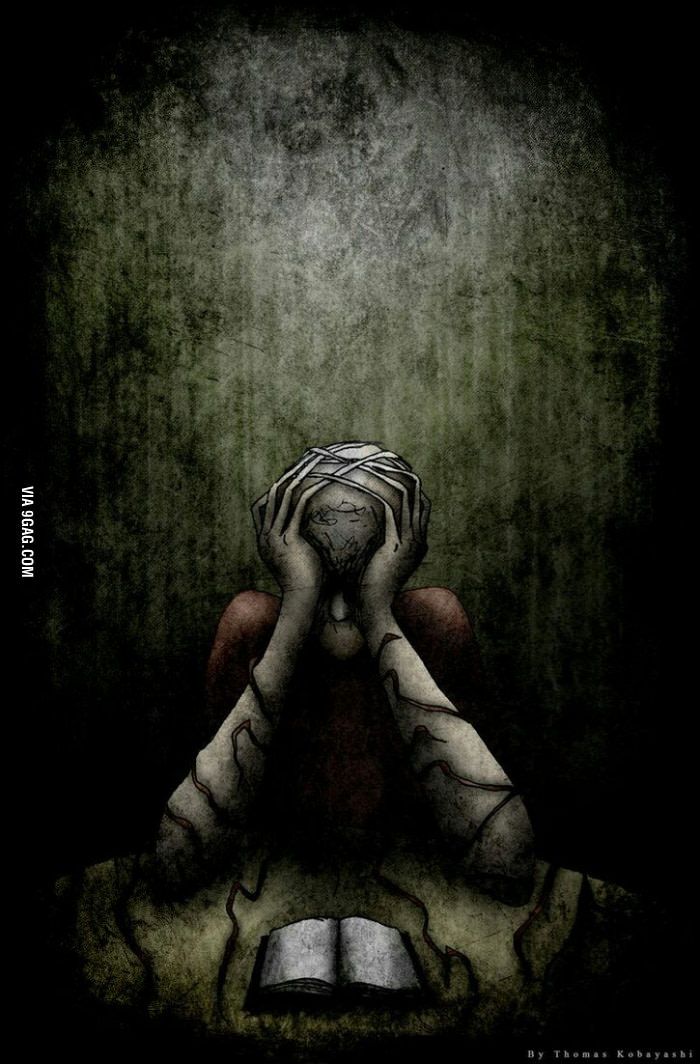

According to the DSM-V, my official diagnosis is panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and underlying depression. Yet sometimes I wonder if my conditions, which fluctuate on a continuum from the height of terror to a vague sense of unease, could instead be called seeing too much, feeling too much, or thinking too much.

I was always a hypersensitive, frightened child. Then, at later points in life—sometimes sober, and sometimes under the influence of psychedelics like psilocybin, peyote, or acid—I saw, felt, and thought things that were perhaps beyond the realm of what I could absorb that quickly. Like, I saw the world as a game or a play. I saw humans as players or actors, and the identities we'd constructed (and those that were constructed for us) as just a farce. Everyone was walking around in a body, engaged in the drama of the world, but no one seemed to be asking

What is going on here? It felt painful that no one was asking. It also hurt, and made no sense, that people were cruel to one another based on those seemingly arbitrary layers of self. Once you see these things, it's hard to shut the door on that awareness. It's hard to just go on pretending it's normal that we exist.

Advertisement

In the seminal 1960s text The Psychedelic Experience: a Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, authors Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert (later known as Ram Dass) and Ralph Metzner define "games" as "behavioral sequences defined by roles, rules, rituals, goals, strategies, values, language, characteristic space−time locations and characteristic patterns of movement." They define heavy game players as "those who cling to their egos" and convey that it is the mind that renders the psychedelic experience, and all life experiences, as "heaven or hell."

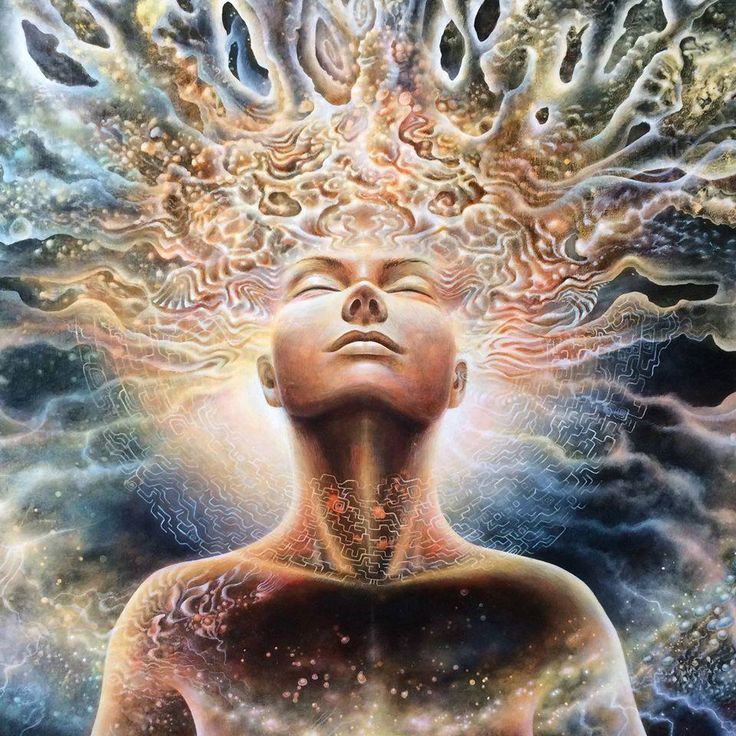

I don't think my use of psychedelics was the cause, or primary catalyst, of my mental illness. I would not consider panic attacks an acid flashback, as I was having panic attacks prior to experimenting with drugs. But I do think that my psychedelic experiences called attention to the frightening dichotomy between the flimsy construction of self and a more fluid, unified consciousness. My experiences with psychedelics, as well as with mental illness, have presented similarities in the ways that they strip away various game identities. In that sense, the experience of depersonalization on psychedelic drugs is an apt metaphor for the feeling of decontextualization in the throws of a panic attack, and vice versa.

But I do think that my psychedelic experiences called attention to the frightening dichotomy between the flimsy construction of self and a more fluid, unified consciousness. My experiences with psychedelics, as well as with mental illness, have presented similarities in the ways that they strip away various game identities. In that sense, the experience of depersonalization on psychedelic drugs is an apt metaphor for the feeling of decontextualization in the throws of a panic attack, and vice versa.

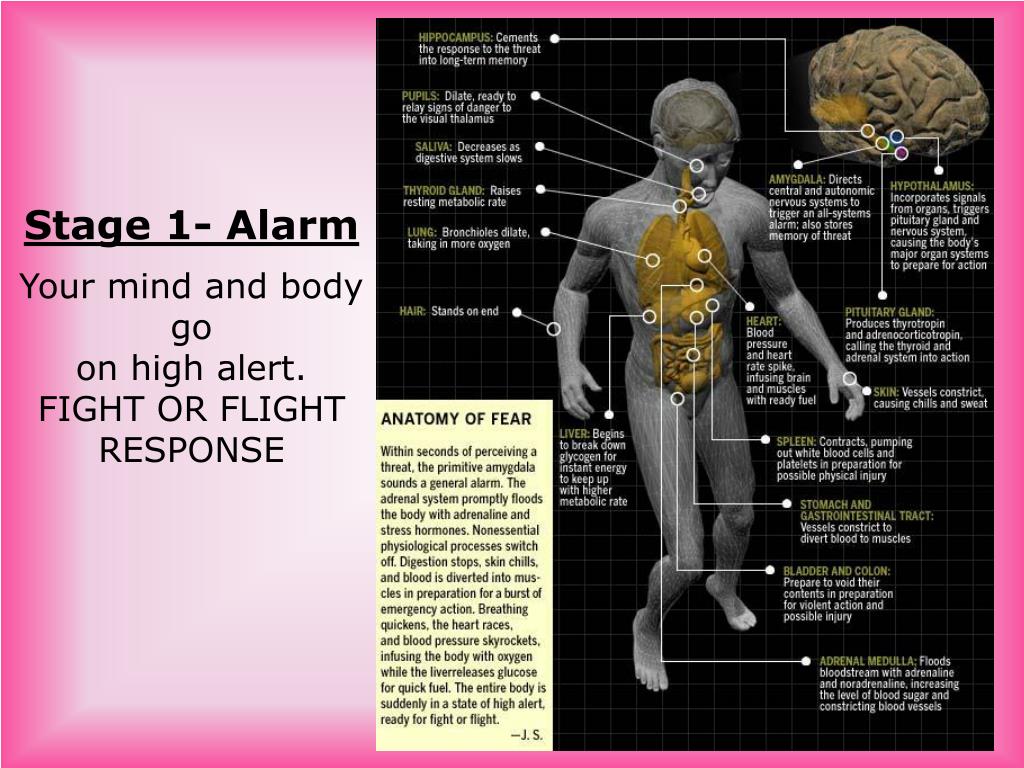

In fact, many of the physical symptoms of a panic attack mirror the ways in which Leary, Alpert, and Metzner describe the sensations of ego loss on psychedelics. In psychedelic ego loss there is "bodily pressure…body disintegrating or blown to atoms…sinking…pressure on head and ears…tingling in extremities…feelings of body flowing as if wax…nausea." Likewise, in the throws of a panic attack I feel suffocating sensations and a tightness in the chest, the experience that I am disintegrating, dissolving, or about to explode, and tingling in my hands and feet. During depressive episodes, often difficult to parse from periods of extreme anxiety (the sludge of mental illness, in my experience, doesn't lend itself easily to organization, clarity, or categorization), I feel caught in a sinking sensation as though all gravity resides in my chest.

During depressive episodes, often difficult to parse from periods of extreme anxiety (the sludge of mental illness, in my experience, doesn't lend itself easily to organization, clarity, or categorization), I feel caught in a sinking sensation as though all gravity resides in my chest.

Advertisement

As for the image of bodies made of wax, this is one of the scariest symptoms of panic attacks that I have experienced. In the throws of a panic attack, there is often a visceral shift in reality where the world suddenly looks like a movie: surreal or hyper-real. If I am with other people, they look plastic, melty, as though they are made of rubber or wearing masks. It's as though I am watching my self, the identity I have constructed, interact with other constructed identities. Not only is it scary—it's also very sad to feel like we are all wearing masks.

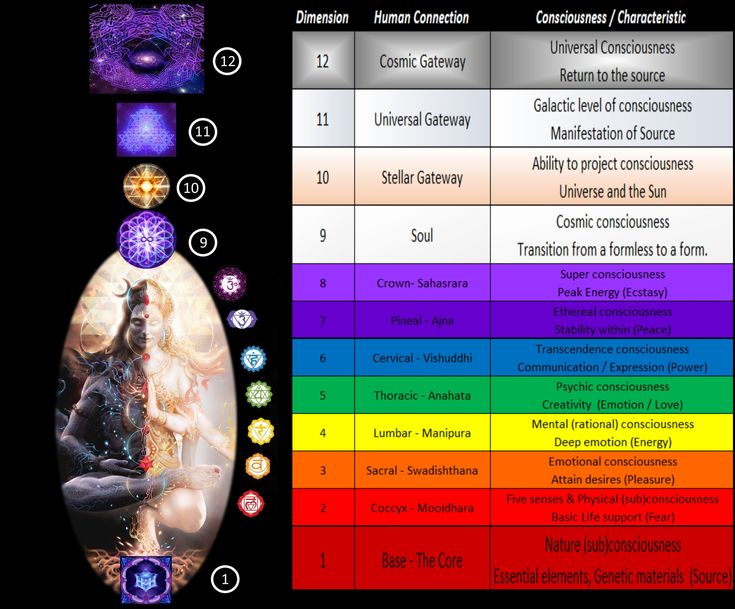

All of these similarities between an acute panic attack, or depressive episode, and the experience of psychedelic drugs make me wonder if mental illness is not, in some ways, a heightened state of consciousness, or intelligence. During these periods, I often find myself asking What am I really? and What's the point? While these aren't comforting questions, I wouldn't call them stupid questions. Rather, they are questions that point to an awareness that we make our own meaning, and that some of the activities, identity components, and life structures we utilize to provide this meaning, "role…status, sex…power, size, beauty," may not be particularly healthy, spiritual, or even real.

During these periods, I often find myself asking What am I really? and What's the point? While these aren't comforting questions, I wouldn't call them stupid questions. Rather, they are questions that point to an awareness that we make our own meaning, and that some of the activities, identity components, and life structures we utilize to provide this meaning, "role…status, sex…power, size, beauty," may not be particularly healthy, spiritual, or even real.

One might even see the questions of What am I? and What's the point? as beneficial questions, if we are willing to face the answers. Often the answers might necessitate a life overhaul—a restructuring of values to align with what we know deep down to be true—and this is terrifying. It can be a massive undertaking. When everyone is wearing masks, I don't know which is more uncomfortable: to wear a mask you know is false or to try and live in a more "naked" way among the masked.

Advertisement

As Leary, Alpert, and Metzner describe it, "Your ego, that one tiny remaining strand of self, screams STOP!. You wrench yourself out of the life-flow, drawn by your intense attachment to your old desires…if there is game distraction around you, you will find yourself dropping back."

You wrench yourself out of the life-flow, drawn by your intense attachment to your old desires…if there is game distraction around you, you will find yourself dropping back."

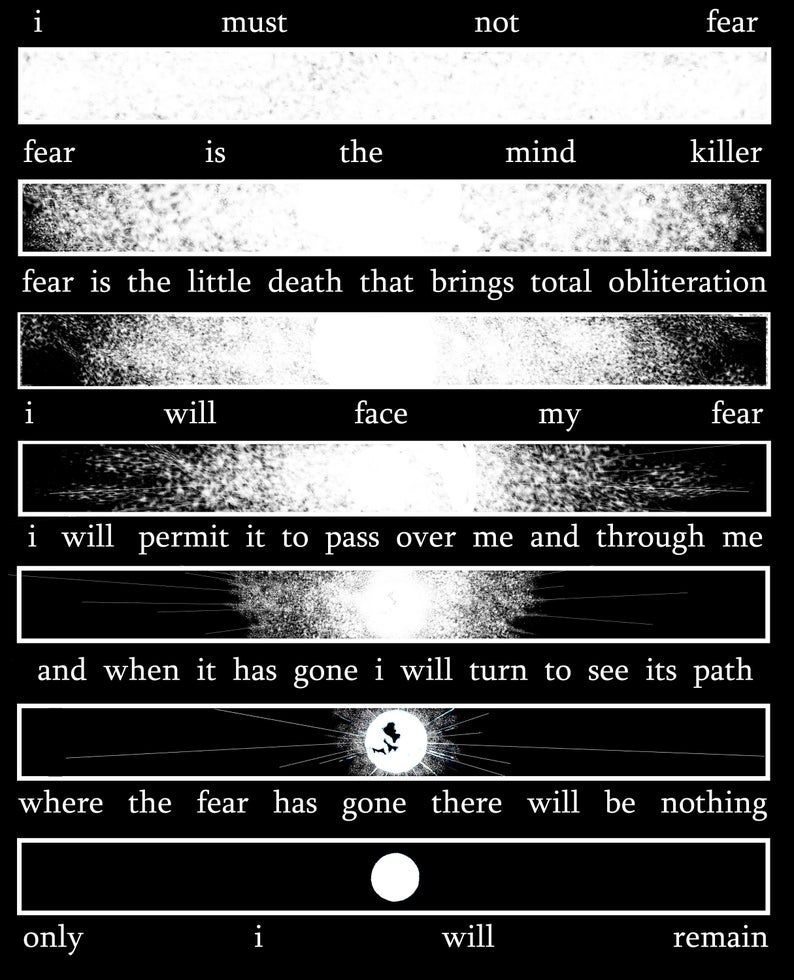

It makes sense then that most people, if given the choice, would prefer not to access that questioning part of the brain. I know that in my deepest periods of mental "unwellness" I have felt like a curtain had been opened in my perception. All I wanted was for the curtain to be closed—to never see anything too clearly again. Similarly, in my psychedelic experiences I had many a trip wherein I felt that I had "gone out" too far and longed to return to a safer, more cloistered mind. Ego death is scary.

Having been clean and sober for many years, I haven't taken psychedelic drugs in a very long time. But even if I wasn't committed to sobriety, I don't think I would be able to handle tripping anymore. Perhaps that's because it was easier to live closer to the deeper "truth"—not so married to the external trappings of a false identity—when I was younger. It's not that I no longer see and feel the friction between a false identity and who I really am anymore. I feel it every time I have a panic attack. But just because you see and feel doesn't mean you change.

It's not that I no longer see and feel the friction between a false identity and who I really am anymore. I feel it every time I have a panic attack. But just because you see and feel doesn't mean you change.

Leary, Alpert, and Metzner say, "Whenever in doubt, turn off your mind, relax, float downstream… physical reactions should be recognized as signs heralding transcendence. Avoid treating them as symptoms of illness, accept them, merge with them, enjoy them."

I have heard the exact same advice given for panic attacks: to ride the anxiety, float with it, bend as a blade of grass bends with the wind, experience it with gratitude as a sign that I am alive. But sometimes I don't want that much aliveness. Sometimes I feel so alive that it might just kill me.

If you are concerned about your mental health or that of someone you know, visit the Mental Health America website.

So Sad Today: Personal Essays will be released next March. Pre-order it here.

Follow So Sad Today on Twitter.

Fear of Black Consciousness

Author: Lewis R. Gordon

$28.00

Available in Digital Audio!

HardcoverDigital Audioe-BookTrade PaperbackFormat

About This Book

Lewis R. Gordon's Fear of Black Consciousness is a groundbreaking account of Black consciousness by a leading philosopher

In this original and penetrating work,...

Book Details

Lewis R. Gordon's Fear of Black Consciousness is a groundbreaking account of Black consciousness by a leading philosopher

In this original and penetrating work, Lewis R. Gordon, one of the leading scholars of Black existentialism and anti-Blackness, takes the reader on a journey through the historical development of racialized Blackness, the problems this kind of consciousness produces, and the many creative responses from Black and non-Black communities in contemporary struggles for dignity and freedom. Skillfully navigating a difficult and traumatic terrain, Gordon cuts through the mist of white narcissism and the versions of consciousness it perpetuates. He exposes the bad faith at the heart of many discussions about race and racism not only in America but across the globe, including those who think of themselves as "color blind." As Gordon reveals, these lies offer many white people an inherited sense of being extraordinary, a license to do as they please. But for many if not most Blacks, to live an ordinary life in a white-dominated society is an extraordinary achievement.

Skillfully navigating a difficult and traumatic terrain, Gordon cuts through the mist of white narcissism and the versions of consciousness it perpetuates. He exposes the bad faith at the heart of many discussions about race and racism not only in America but across the globe, including those who think of themselves as "color blind." As Gordon reveals, these lies offer many white people an inherited sense of being extraordinary, a license to do as they please. But for many if not most Blacks, to live an ordinary life in a white-dominated society is an extraordinary achievement.

Informed by Gordon's life growing up in Jamaica and the Bronx, and taking as a touchstone the pandemic and the uprisings against police violence, Fear of Black Consciousness is a groundbreaking work that positions Black consciousness as a political commitment and creative practice, richly layered through art, love, and revolutionary action.

Imprint Publisher

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

ISBN

9780374159023

In The News

“Lewis Gordon’s expansive philosophical engagement with the current moment—its histories and globalities, its politics and protests, its visual and sonic cultures—reminds us that the ultimate aim of Black freedom quests is, indeed, universal liberation. ”

”

—Angela Y. Davis, Distinguished Professor Emerita, History of Consciousness and Feminist Studies at University of California, Santa Cruz

“Reading Fear of Black Consciousness had me nodding so often and so vigorously, I got a mild case of whiplash. With surgical precision, laser-sharp wit, and the eye of an artist, Lewis R. Gordon doesn’t just dissect race, racism, and racial thinking; he also offers a clarion call to embrace Black consciousness, to take political responsibility for decolonizing and transforming the world as it is.”

—Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original

“Lewis R. Gordon is a thinker whose reflections on race have produced singular illuminations on our times. In Fear of Black Consciousness, he refines our conceptual understanding of how race consciousness is made and lived, and shows how reflection and survival are intertwined for all those who suffer from antiblack racism. Drawing on the history of philosophy and on a wide range of colonial histories, African popular culture, aboriginal histories, contemporary films, and stories, he shows the critical powers of creativity in dismantling racism and the making of a world where breath and love and existence become possible.”

Drawing on the history of philosophy and on a wide range of colonial histories, African popular culture, aboriginal histories, contemporary films, and stories, he shows the critical powers of creativity in dismantling racism and the making of a world where breath and love and existence become possible.”

—Judith Butler, author of The Force of Nonviolence

“This striking text offers the first systematic examination that I’ve seen of the epistemic dimensions of the universal illness that encompasses neoconservatism and neoliberalism. We learn the differences between a first-level, naive black consciousness and a revised and refined ‘Black consciousness,’ which critically reflects on this world and is capable of radically transforming it. You will want this book among your primary intellectual road supplies for the future.”

—Hortense J. Spillers, Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Professor of English Emerita at Vanderbilt University

"In Fear of Black Consciousness, we are invited to think through the deep racial contours of philosophical thought and notice how black ways of being animate new modes of living together. As atrocity, injury, white supremacy, and racial violence loom, Gordon holds steady a Fanonian outlook, theorizing black consciousness as the realization of possibility—that is, a sustained political commitment that recalculates the stakes of freedom."

As atrocity, injury, white supremacy, and racial violence loom, Gordon holds steady a Fanonian outlook, theorizing black consciousness as the realization of possibility—that is, a sustained political commitment that recalculates the stakes of freedom."

—Katherine McKittrick, author of Demonic Grounds and Dear Science

"Fear of Black Consciousness deserves to be carefully studied . . . deeply engaging and captivating . . . [Lewis Gordon] is an ally of the revolutionary struggle for human freedom."

—Joel Wendland-Liu, People's World

About the Creators

$28.00

Available in Digital Audio!

HardcoverDigital Audioe-BookTrade PaperbackFormat

Fear of Black Consciousness

00:00

/

00:00

MEMO Advice for those who are afraid of the sight of blood

Fear of the sight of blood in medicine is called hemophobia (from the words hemo - blood and phobia - fear, fear). Hemophobes are mostly impressionable, suspicious people with a fine nervous organization, able to sympathize and empathize with others, owners of an artistic mindset.

Hemophobes are mostly impressionable, suspicious people with a fine nervous organization, able to sympathize and empathize with others, owners of an artistic mindset.

The fantasy of an individual with this disorder will draw a huge pool of blood from a small speck of tomato juice. These persons, as a rule, avoid visiting medical institutions, refuse treatment and preventive procedures. They are "driven" by the strongest anxiety that in hospitals they can see blood, and God forbid - it will be their own blood!

A miracle cure in such cases is communication with close friends, for whom procedures related to blood sampling, blood transfusion are a common thing. Having mastered the knowledge that all manipulations carried out in medical institutions are safe and painless, a person suffering from a mild degree of hemophobia significantly reduces the level of anxiety, and by the end of his studies, this fear completely disappears.

Here are some more practical tips.

- Try to tighten the muscles as much as possible, starting with the muscles of the arms, gradually involving all the muscles of the body. Having reached the peak of tension and keeping the muscles in good shape, try to make movements with the limbs. Practice these movements as often as possible to fix the exercise in your mind. The secret of this exercise is simple: during an attack of hemophobia, as a rule, blood pressure decreases, as a result of which the patient loses consciousness. When a fear attack approaches, your brain will remind you of the workouts you have done, and you will automatically tense your muscles and “wave” your arms. At a critical moment, this will help improve blood circulation, thereby avoiding fainting.

- Vigorous exercise helps restore normal blood flow. As soon as you feel the approach of a critical moment, start doing squats or jumps.

- An excellent method to prevent blackouts is to learn to control your breathing. Practice a way to achieve hyperventilation.

Take a deep breath, using the abdominal muscles, hold your breath for a few seconds and exhale vigorously. Without a break - take the next breath. Master the cycle of 10, bringing it up to 20 inhales and exhales. Breathing exercises help to mobilize forces at the right time and take control of the emotional state.

Take a deep breath, using the abdominal muscles, hold your breath for a few seconds and exhale vigorously. Without a break - take the next breath. Master the cycle of 10, bringing it up to 20 inhales and exhales. Breathing exercises help to mobilize forces at the right time and take control of the emotional state. - If you are tormented by the conscience that you want to become a donor, but because of your aversion to blood, you simply cannot do it, we advise you to contact a specialist. In the end, blood is something quite natural and it is simply stupid to be afraid of it.

e-mail: [email protected]

Phones for appointment:

blood donors +37517-239-59-13, +375 29 190-97-48 (from 12:00 to 15:45)

donors of blood components +37517-239-59-12, +375 29 190-97-48 (from 12:00 to 15:45)

transfusion hemocorrection rooms (treatment room) +37517-239-59-23

department of obstetric immunohematology (registration) +37517-239 -59-45

Telephones of paid services

"Hot line" "6th City Clinical Hospital" +37517-392-54-68

Information line of the Health Committee of the Minsk City Executive Committee

on topical and problematic issues of medical care

phone: +37517-284-41-39

on weekdays from 09. 00-17.30, a break from 13.00-14.00, the call is free.

00-17.30, a break from 13.00-14.00, the call is free.

Psychological help

National children's helpline for children who have been abused: 8-801-100-1611 24 hours a day (toll free from landlines)

Emergency psychological help for adults +375 (17) 352 -4-444

telephone for emergency psychological assistance for children and adolescents +375 (17) 263-03-03

telephone of the City Center for Border Conditions +375 (17) 351-6-174

Information line of the Health Committee of the Minsk City Executive Committee on topical and problematic issues of medical care phone: +375 (17) 350-41-39 on weekdays from 09.00-17.30, break from 13.00-14.00, the call is free.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

A prominent role among mental illnesses is played by syndromes (complexes of symptoms), united in the group of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), which received its name from the Latin terms obsessio and compulsio.

Obsession (lat. obsessio - taxation, siege, blockade).

Compulsions (lat. compello - I force). 1. Obsessive drives, a kind of obsessive phenomena (obsessions). Characterized by irresistible attraction that arises contrary to the mind, will, feelings. Often they are unacceptable to the patient, contrary to his moral and ethical properties. Unlike impulsive drives, compulsions are not realized. These drives are recognized by the patient as wrong and painfully experienced by them, especially since their very appearance, due to its incomprehensibility, often gives rise to a feeling of fear in the patient 2. The term compulsions is also used in a broader sense to refer to any obsessions in the motor sphere, including obsessive rituals.

In domestic psychiatry, obsessive states were understood as psychopathological phenomena, characterized by the fact that phenomena of a certain content repeatedly appear in the mind of the patient, accompanied by a painful feeling of coercion [Zinoviev PM, 193I]. For N.s. characteristic involuntary, even against the will, the emergence of obsessions with clear consciousness. Although the obsessions are alien, extraneous in relation to the patient's psyche, the patient is not able to get rid of them. They are closely related to the emotional sphere, accompanied by depressive reactions, anxiety. Being symptomatic, according to S.L. Sukhanov [1912], "parasitic", they do not affect the course of intellectual activity in general, remain alien to thinking, do not lead to a decrease in its level, although they worsen the efficiency and productivity of the patient's mental activity. Throughout the course of the disease, a critical attitude is maintained towards obsessions. N.s. conditionally divided into obsessions in the intellectual-affective (phobia) and motor (compulsions) spheres, but most often several of their types are combined in the structure of the disease of obsessions. The isolation of obsessions that are abstract, affectively indifferent, indifferent in their content, for example, arrhythmomania, is rarely justified; An analysis of the psychogenesis of a neurosis often makes it possible to see a pronounced affective (depressive) background at the basis of the obsessive account.

For N.s. characteristic involuntary, even against the will, the emergence of obsessions with clear consciousness. Although the obsessions are alien, extraneous in relation to the patient's psyche, the patient is not able to get rid of them. They are closely related to the emotional sphere, accompanied by depressive reactions, anxiety. Being symptomatic, according to S.L. Sukhanov [1912], "parasitic", they do not affect the course of intellectual activity in general, remain alien to thinking, do not lead to a decrease in its level, although they worsen the efficiency and productivity of the patient's mental activity. Throughout the course of the disease, a critical attitude is maintained towards obsessions. N.s. conditionally divided into obsessions in the intellectual-affective (phobia) and motor (compulsions) spheres, but most often several of their types are combined in the structure of the disease of obsessions. The isolation of obsessions that are abstract, affectively indifferent, indifferent in their content, for example, arrhythmomania, is rarely justified; An analysis of the psychogenesis of a neurosis often makes it possible to see a pronounced affective (depressive) background at the basis of the obsessive account. Along with elementary obsessions, the connection of which with psychogeny is obvious, there are “cryptogenic” ones, when the cause of painful experiences is hidden [Svyadoshch L.M., 1959]. N.s. are observed mainly in individuals with a psychasthenic character. This is where apprehensions are especially characteristic. In addition, N.S. occur within the framework of neurosis-like states with sluggish schizophrenia, endogenous depressions, epilepsy, the consequences of a traumatic brain injury, somatic diseases, mainly hypochondria-phobic or nosophobic syndrome. Some researchers distinguish the so-called. "Neurosis of obsessive states", which is characterized by the predominance of obsessive states in the clinical picture - memories that reproduce a psychogenic traumatic situation, thoughts, fears, actions. In genesis play a role: mental trauma; conditioned reflex stimuli that have become pathogenic due to their coincidence with others that previously caused a feeling of fear; situations that have become psychogenic due to the confrontation of opposing tendencies [Svyadoshch A.

Along with elementary obsessions, the connection of which with psychogeny is obvious, there are “cryptogenic” ones, when the cause of painful experiences is hidden [Svyadoshch L.M., 1959]. N.s. are observed mainly in individuals with a psychasthenic character. This is where apprehensions are especially characteristic. In addition, N.S. occur within the framework of neurosis-like states with sluggish schizophrenia, endogenous depressions, epilepsy, the consequences of a traumatic brain injury, somatic diseases, mainly hypochondria-phobic or nosophobic syndrome. Some researchers distinguish the so-called. "Neurosis of obsessive states", which is characterized by the predominance of obsessive states in the clinical picture - memories that reproduce a psychogenic traumatic situation, thoughts, fears, actions. In genesis play a role: mental trauma; conditioned reflex stimuli that have become pathogenic due to their coincidence with others that previously caused a feeling of fear; situations that have become psychogenic due to the confrontation of opposing tendencies [Svyadoshch A. M., 1982]. It should be noted that these same authors emphasize that N.s.c. occurs with various character traits, but most often in psychasthenic personalities.

M., 1982]. It should be noted that these same authors emphasize that N.s.c. occurs with various character traits, but most often in psychasthenic personalities.

Currently, almost all obsessive-compulsive disorders are united in the International Classification of Diseases under the concept of "obsessive-compulsive disorder".

OKR concepts have undergone a fundamental reassessment over the past 15 years. During this time, the clinical and epidemiological significance of OCD has been completely revised. If it was previously thought that this is a rare condition observed in a small number of people, now it is known that OCD is common and causes a high percentage of morbidity, which requires the urgent attention of psychiatrists around the world. Parallel to this, our understanding of the etiology of OCD has broadened: the vaguely formulated psychoanalytic definition of the past two decades has been replaced by a neurochemical paradigm that explores the neurotransmitter disorders that underlie OCD. And most importantly, pharmacological interventions specifically targeting serotonergic neurotransmission have revolutionized the prospects for recovery for millions of OCD patients worldwide.

And most importantly, pharmacological interventions specifically targeting serotonergic neurotransmission have revolutionized the prospects for recovery for millions of OCD patients worldwide.

The discovery that intense serotonin reuptake inhibition (SSRI) was the key to effective treatment for OCD was the first step in a revolution and spurred clinical research that showed the efficacy of such selective inhibitors.

As described in ICD-10, the main features of OCD are repetitive intrusive (obsessive) thoughts and compulsive actions (rituals).

In a broad sense, the core of OCD is the syndrome of obsession, which is a condition with a predominance in the clinical picture of feelings, thoughts, fears, memories that arise in addition to the desire of patients, but with awareness of their pain and a critical attitude towards them. Despite the understanding of the unnaturalness, illogicality of obsessions and states, patients are powerless in their attempts to overcome them. Obsessional impulses or ideas are recognized as alien to the personality, but as if coming from within. Obsessions can be the performance of rituals designed to alleviate anxiety, such as washing hands to combat "pollution" and to prevent "infection". Attempts to drive away unwelcome thoughts or urges can lead to severe internal struggle, accompanied by intense anxiety.

Obsessional impulses or ideas are recognized as alien to the personality, but as if coming from within. Obsessions can be the performance of rituals designed to alleviate anxiety, such as washing hands to combat "pollution" and to prevent "infection". Attempts to drive away unwelcome thoughts or urges can lead to severe internal struggle, accompanied by intense anxiety.

Obsessions in the ICD-10 are included in the group of neurotic disorders.

The prevalence of OCD in the population is quite high. According to some data, it is determined by an indicator of 1.5% (meaning "fresh" cases of diseases) or 2-3%, if episodes of exacerbations observed throughout life are taken into account. Those suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder make up 1% of all patients receiving treatment in psychiatric institutions. It is believed that men and women are affected approximately equally.

CLINICAL PICTURE

The problem of obsessive-compulsive disorders attracted the attention of clinicians already at the beginning of the 17th century. They were first described by Platter in 1617. In 1621 E. Barton described an obsessive fear of death. Mentions of obsessions are found in the writings of F. Pinel (1829). I. Balinsky proposed the term "obsessive ideas", which took root in Russian psychiatric literature. In 1871, Westphal coined the term "agoraphobia" to refer to the fear of being in public places. M. Legrand de Sol [1875], analyzing the features of the dynamics of OCD in the form of "insanity of doubt with delusions of touch, points to a gradually becoming more complicated clinical picture - obsessive doubts are replaced by ridiculous fears of" touch "to surrounding objects, motor rituals join, the fulfillment of which is subject to the whole life sick. However, only at the turn of the XIX-XX centuries. researchers were able to more or less clearly describe the clinical picture and give syndromic characteristics of obsessive-compulsive disorders. The onset of the disease usually occurs in adolescence and adolescence. The maximum of clinically defined manifestations of obsessive-compulsive disorder is observed in the age range of 10-25 years.

They were first described by Platter in 1617. In 1621 E. Barton described an obsessive fear of death. Mentions of obsessions are found in the writings of F. Pinel (1829). I. Balinsky proposed the term "obsessive ideas", which took root in Russian psychiatric literature. In 1871, Westphal coined the term "agoraphobia" to refer to the fear of being in public places. M. Legrand de Sol [1875], analyzing the features of the dynamics of OCD in the form of "insanity of doubt with delusions of touch, points to a gradually becoming more complicated clinical picture - obsessive doubts are replaced by ridiculous fears of" touch "to surrounding objects, motor rituals join, the fulfillment of which is subject to the whole life sick. However, only at the turn of the XIX-XX centuries. researchers were able to more or less clearly describe the clinical picture and give syndromic characteristics of obsessive-compulsive disorders. The onset of the disease usually occurs in adolescence and adolescence. The maximum of clinically defined manifestations of obsessive-compulsive disorder is observed in the age range of 10-25 years.

Main clinical manifestations of OCD:

Obsessional thoughts - painful, arising against the will, but recognized by the patient as their own, ideas, beliefs, images, which in a stereotyped form forcibly invade the patient's consciousness and which he tries to resist in some way. It is this combination of an inner sense of compulsive urge and efforts to resist it that characterizes obsessional symptoms, but of the two, the degree of effort exerted is the more variable. Obsessive thoughts may take the form of single words, phrases, or lines of poetry; they are usually unpleasant to the patient and may be obscene, blasphemous, or even shocking.

Obsessional imagery is vivid scenes, often violent or disgusting, including, for example, sexual perversion.

Obsessional impulses are urges to do things that are usually destructive, dangerous or shameful; for example, jumping into the road in front of a moving car, injuring a child, or shouting obscene words while in society.

Obsessional rituals include both mental activities (eg, counting repeatedly in a particular way, or repeating certain words) and repetitive but meaningless acts (eg, washing hands twenty or more times a day). Some of them have an understandable connection with the obsessive thoughts that preceded them, for example, repeated washing of hands - with thoughts of infection. Other rituals (for example, regularly laying out clothes in some complex system before putting them on) do not have such a connection. Some patients feel an irresistible urge to repeat such actions a certain number of times; if that fails, they are forced to start all over again. Patients are invariably aware that their rituals are illogical and usually try to hide them. Some fear that such symptoms are a sign of the onset of insanity. Both obsessive thoughts and rituals inevitably lead to problems in daily activities.

Obsessive rumination (“mental chewing gum”) is an internal debate in which the arguments for and against even the simplest everyday actions are endlessly revised. Some obsessive doubts relate to actions that may have been incorrectly performed or not completed, such as turning off the gas stove faucet or locking the door; others concern actions that could harm other people (for example, the possibility of driving past a cyclist in a car, knocking him down). Sometimes doubts are associated with a possible violation of religious prescriptions and rituals - “remorse of conscience”.

Some obsessive doubts relate to actions that may have been incorrectly performed or not completed, such as turning off the gas stove faucet or locking the door; others concern actions that could harm other people (for example, the possibility of driving past a cyclist in a car, knocking him down). Sometimes doubts are associated with a possible violation of religious prescriptions and rituals - “remorse of conscience”.

Compulsive actions - repetitive stereotypical actions, sometimes acquiring the character of protective rituals. The latter are aimed at preventing any objectively unlikely events that are dangerous for the patient or his relatives.

In addition to the above, in a number of obsessive-compulsive disorders, a number of well-defined symptom complexes stand out, and among them are obsessive doubts, contrasting obsessions, obsessive fears - phobias (from the Greek. phobos).

Obsessive thoughts and compulsive rituals may intensify in certain situations; for example, obsessive thoughts about harming other people often become more persistent in the kitchen or some other place where knives are kept. Since patients often avoid such situations, there may be a superficial resemblance to the characteristic avoidance pattern found in phobic anxiety disorder. Anxiety is an important component of obsessive-compulsive disorders. Some rituals reduce anxiety, while after others it increases. Obsessions often develop as part of depression. In some patients, this appears to be a psychologically understandable reaction to obsessive-compulsive symptoms, but in other patients, recurrent episodes of depressive mood occur independently.

Since patients often avoid such situations, there may be a superficial resemblance to the characteristic avoidance pattern found in phobic anxiety disorder. Anxiety is an important component of obsessive-compulsive disorders. Some rituals reduce anxiety, while after others it increases. Obsessions often develop as part of depression. In some patients, this appears to be a psychologically understandable reaction to obsessive-compulsive symptoms, but in other patients, recurrent episodes of depressive mood occur independently.

Obsessions (obsessions) are divided into figurative or sensual, accompanied by the development of affect (often painful) and obsessions of affectively neutral content.

Sensual obsessions include obsessive doubts, memories, ideas, drives, actions, fears, an obsessive feeling of antipathy, an obsessive fear of habitual actions.

Obsessive doubts - intrusively arising contrary to logic and reason, uncertainty about the correctness of committed and committed actions. The content of doubts is different: obsessive everyday fears (whether the door is locked, whether windows or water taps are closed tightly enough, whether gas and electricity are turned off), doubts related to official activities (whether this or that document is written correctly, whether the addresses on business papers are mixed up , whether inaccurate figures are indicated, whether orders are correctly formulated or executed), etc. Despite repeated verification of the committed action, doubts, as a rule, do not disappear, causing psychological discomfort in the person suffering from this kind of obsession.

The content of doubts is different: obsessive everyday fears (whether the door is locked, whether windows or water taps are closed tightly enough, whether gas and electricity are turned off), doubts related to official activities (whether this or that document is written correctly, whether the addresses on business papers are mixed up , whether inaccurate figures are indicated, whether orders are correctly formulated or executed), etc. Despite repeated verification of the committed action, doubts, as a rule, do not disappear, causing psychological discomfort in the person suffering from this kind of obsession.

Obsessive memories include persistent, irresistible painful memories of any sad, unpleasant or shameful events for the patient, accompanied by a sense of shame, remorse. They dominate the mind of the patient, despite the efforts and efforts not to think about them.

Obsessive impulses - urges to commit one or another tough or extremely dangerous action, accompanied by a feeling of horror, fear, confusion with the inability to get rid of it. The patient is seized, for example, by the desire to throw himself under a passing train or push a loved one under it, to kill his wife or child in an extremely cruel way. At the same time, patients are painfully afraid that this or that action will be implemented.

The patient is seized, for example, by the desire to throw himself under a passing train or push a loved one under it, to kill his wife or child in an extremely cruel way. At the same time, patients are painfully afraid that this or that action will be implemented.

Manifestations of obsessive ideas can be different. In some cases, this is a vivid "vision" of the results of obsessive drives, when patients imagine the result of a cruel act committed. In other cases, obsessive ideas, often referred to as mastering, appear in the form of implausible, sometimes absurd situations that patients take for real. An example of obsessive ideas is the patient's conviction that the buried relative was alive, and the patient painfully imagines and experiences the suffering of the deceased in the grave. At the height of obsessive ideas, the consciousness of their absurdity, implausibility disappears and, on the contrary, confidence in their reality appears. As a result, obsessions acquire the character of overvalued formations (dominant ideas that do not correspond to their true meaning), and sometimes delusions.

An obsessive feeling of antipathy (as well as obsessive blasphemous and blasphemous thoughts) - unjustified, driven away by the patient from himself antipathy towards a certain, often close person, cynical, unworthy thoughts and ideas in relation to respected people, in religious persons - in relation to saints or ministers churches.

Obsessive acts are acts done against the wishes of the sick, despite efforts made to restrain them. Some of the obsessive actions burden the patients until they are realized, others are not noticed by the patients themselves. Obsessive actions are painful for patients, especially in those cases when they become the object of attention of others.

Obsessive fears, or phobias, include an obsessive and senseless fear of heights, large streets, open or confined spaces, large crowds of people, the fear of sudden death, the fear of falling ill with one or another incurable disease. Some patients may develop a wide variety of phobias, sometimes acquiring the character of fear of everything (panphobia). And finally, an obsessive fear of the emergence of fears (phobophobia) is possible.

And finally, an obsessive fear of the emergence of fears (phobophobia) is possible.

Hypochondriacal phobias (nosophobia) - an obsessive fear of some serious illness. Most often, cardio-, stroke-, syphilo- and AIDS phobias are observed, as well as the fear of the development of malignant tumors. At the peak of anxiety, patients sometimes lose their critical attitude to their condition - they turn to doctors of the appropriate profile, require examination and treatment. The implementation of hypochondriacal phobias occurs both in connection with psycho- and somatogenic (general non-mental illnesses) provocations, and spontaneously. As a rule, hypochondriacal neurosis develops as a result, accompanied by frequent visits to doctors and unreasonable medication.

Specific (isolated) phobias - obsessive fears limited to a strictly defined situation - fear of heights, nausea, thunderstorms, pets, treatment at the dentist, etc. Since contact with situations that cause fear is accompanied by intense anxiety, the patients tend to avoid them.

Obsessive fears are often accompanied by the development of rituals - actions that have the meaning of "magic" spells that are performed, despite the critical attitude of the patient to obsession, in order to protect against one or another imaginary misfortune: before starting any important business, the patient must perform some that specific action to eliminate the possibility of failure. Rituals can, for example, be expressed in snapping fingers, playing a melody to the patient or repeating certain phrases, etc. In these cases, even relatives are not aware of the existence of such disorders. Rituals, combined with obsessions, are a fairly stable system that usually exists for many years and even decades.

Obsessions of affectively neutral content - obsessive sophistication, obsessive counting, recalling neutral events, terms, formulations, etc. Despite their neutral content, they burden the patient, interfere with his intellectual activity.

Contrasting obsessions ("aggressive obsessions") - blasphemous, blasphemous thoughts, fear of harming oneself and others. Psychopathological formations of this group refer mainly to figurative obsessions with pronounced affective saturation and ideas that take possession of the consciousness of patients. They are distinguished by a sense of alienation, the absolute lack of motivation of the content, as well as a close combination with obsessive drives and actions. Patients with contrasting obsessions and complain of an irresistible desire to add endings to the replicas they have just heard, giving an unpleasant or threatening meaning to what has been said, to repeat after those around them, but with a touch of irony or malice, phrases of religious content, to shout out cynical words that contradict their own attitudes and generally accepted morality. , they may experience fear of losing control of themselves and possibly committing dangerous or ridiculous actions, injuring themselves or their loved ones. In the latter cases, obsessions are often combined with object phobias (fear of sharp objects - knives, forks, axes, etc.

Psychopathological formations of this group refer mainly to figurative obsessions with pronounced affective saturation and ideas that take possession of the consciousness of patients. They are distinguished by a sense of alienation, the absolute lack of motivation of the content, as well as a close combination with obsessive drives and actions. Patients with contrasting obsessions and complain of an irresistible desire to add endings to the replicas they have just heard, giving an unpleasant or threatening meaning to what has been said, to repeat after those around them, but with a touch of irony or malice, phrases of religious content, to shout out cynical words that contradict their own attitudes and generally accepted morality. , they may experience fear of losing control of themselves and possibly committing dangerous or ridiculous actions, injuring themselves or their loved ones. In the latter cases, obsessions are often combined with object phobias (fear of sharp objects - knives, forks, axes, etc. ). The contrasting group also partially includes obsessions of sexual content (obsessions of the type of forbidden ideas about perverted sexual acts, the objects of which are children, representatives of the same sex, animals).

). The contrasting group also partially includes obsessions of sexual content (obsessions of the type of forbidden ideas about perverted sexual acts, the objects of which are children, representatives of the same sex, animals).

Obsessions of pollution (mysophobia). This group of obsessions includes both the fear of pollution (earth, dust, urine, feces and other impurities), as well as the fear of penetration into the body of harmful and toxic substances (cement, fertilizers, toxic waste), small objects (glass fragments, needles, specific types of dust), microorganisms. In some cases, the fear of contamination can be limited, remain at the preclinical level for many years, manifesting itself only in some features of personal hygiene (frequent change of linen, repeated washing of hands) or in housekeeping (thorough handling of food, daily washing of floors). , "taboo" on pets). This kind of monophobia does not significantly affect the quality of life and is evaluated by others as habits (exaggerated cleanliness, excessive disgust). Clinically manifested variants of mysophobia belong to the group of severe obsessions. In these cases, gradually becoming more complex protective rituals come to the fore: avoiding sources of pollution and touching "unclean" objects, processing things that could get dirty, a certain sequence in the use of detergents and towels, which allows you to maintain "sterility" in the bathroom. Stay outside the apartment is also furnished with a series of protective measures: going out into the street in special clothing that covers the body as much as possible, special processing of wearable items upon returning home. In the later stages of the disease, patients, avoiding pollution, not only do not go out, but do not even leave their own room. In order to avoid contacts and contacts that are dangerous in terms of contamination, patients do not allow even their closest relatives to come near them. Mysophobia is also related to the fear of contracting a disease, which does not belong to the categories of hypochondriacal phobias, since it is not determined by fears that a person suffering from OCD has a particular disease.

Clinically manifested variants of mysophobia belong to the group of severe obsessions. In these cases, gradually becoming more complex protective rituals come to the fore: avoiding sources of pollution and touching "unclean" objects, processing things that could get dirty, a certain sequence in the use of detergents and towels, which allows you to maintain "sterility" in the bathroom. Stay outside the apartment is also furnished with a series of protective measures: going out into the street in special clothing that covers the body as much as possible, special processing of wearable items upon returning home. In the later stages of the disease, patients, avoiding pollution, not only do not go out, but do not even leave their own room. In order to avoid contacts and contacts that are dangerous in terms of contamination, patients do not allow even their closest relatives to come near them. Mysophobia is also related to the fear of contracting a disease, which does not belong to the categories of hypochondriacal phobias, since it is not determined by fears that a person suffering from OCD has a particular disease. In the foreground is the fear of a threat from the outside: the fear of pathogenic bacteria entering the body. Hence the development of appropriate protective actions.

In the foreground is the fear of a threat from the outside: the fear of pathogenic bacteria entering the body. Hence the development of appropriate protective actions.

A special place in the series of obsessions is occupied by obsessive actions in the form of isolated, monosymptomatic movement disorders. Among them, especially in childhood, tics predominate, which, unlike organically conditioned involuntary movements, are much more complex motor acts that have lost their original meaning. Tics sometimes give the impression of exaggerated physiological movements. This is a kind of caricature of certain motor acts, natural gestures. Patients suffering from tics can shake their heads (as if checking whether the hat fits well), make hand movements (as if discarding interfering hair), blink their eyes (as if getting rid of a mote). Along with obsessive tics, pathological habitual actions (lip biting, gnashing of teeth, spitting, etc.) are often observed, which differ from obsessive actions proper in the absence of a subjectively painful sense of persistence and experience them as alien, painful. Neurotic states characterized only by obsessive tics usually have a favorable prognosis. Appearing most often in preschool and primary school age, tics usually subside by the end of puberty. However, such disorders can also be more persistent, persist for many years and only partially change in manifestations.

Neurotic states characterized only by obsessive tics usually have a favorable prognosis. Appearing most often in preschool and primary school age, tics usually subside by the end of puberty. However, such disorders can also be more persistent, persist for many years and only partially change in manifestations.

The course of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Unfortunately, chronization must be indicated as the most characteristic trend in the OCD dynamics. Cases of episodic manifestations of the disease and complete recovery are relatively rare. However, in many patients, especially with the development and preservation of one type of manifestation (agoraphobia, obsessive counting, ritual handwashing, etc.), a long-term stabilization of the condition is possible. In these cases, there is a gradual (usually in the second half of life) mitigation of psychopathological symptoms and social readaptation. For example, patients who experienced fear of traveling on certain types of transport, or public speaking, cease to feel flawed and work along with healthy people. In mild forms of OCD, the disease usually proceeds favorably (on an outpatient basis). The reverse development of symptoms occurs after 1 year - 5 years from the moment of manifestation.

In mild forms of OCD, the disease usually proceeds favorably (on an outpatient basis). The reverse development of symptoms occurs after 1 year - 5 years from the moment of manifestation.

More severe and complex OCDs such as phobias of infection, pollution, sharp objects, contrasting performances, multiple rituals, on the other hand, may become persistent, resistant to treatment, or show a tendency to recur with disorders that persist despite active therapy. Further negative dynamics of these conditions indicates a gradual complication of the clinical picture of the disease as a whole.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

It is important to distinguish OCD from other disorders that involve compulsions and rituals. In some cases, obsessive-compulsive disorder must be differentiated from schizophrenia, especially when the obsessive thoughts are unusual in content (eg, mixed sexual and blasphemous themes) or the rituals are exceptionally eccentric. The development of a sluggish schizophrenic process cannot be ruled out with the growth of ritual formations, their persistence, the emergence of antagonistic tendencies in mental activity (inconsistency of thinking and actions), and the uniformity of emotional manifestations. Prolonged obsessional states of a complex structure must be distinguished from the manifestations of paroxysmal schizophrenia. Unlike neurotic obsessive states, they are usually accompanied by a sharply increasing anxiety, a significant expansion and systematization of the circle of obsessive associations, which acquire the character of obsessions of "special significance": previously indifferent objects, events, random remarks of others remind patients of the content of phobias, offensive thoughts and thereby acquire in their view a special, menacing significance. In such cases, it is necessary to consult a psychiatrist in order to exclude schizophrenia. It can also be difficult to differentiate between OCD and conditions with a predominance of generalized disorders, known as Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome. Tics in such cases are localized in the face, neck, upper and lower extremities and are accompanied by grimaces, opening the mouth, sticking out the tongue, and intense gesticulation.

Prolonged obsessional states of a complex structure must be distinguished from the manifestations of paroxysmal schizophrenia. Unlike neurotic obsessive states, they are usually accompanied by a sharply increasing anxiety, a significant expansion and systematization of the circle of obsessive associations, which acquire the character of obsessions of "special significance": previously indifferent objects, events, random remarks of others remind patients of the content of phobias, offensive thoughts and thereby acquire in their view a special, menacing significance. In such cases, it is necessary to consult a psychiatrist in order to exclude schizophrenia. It can also be difficult to differentiate between OCD and conditions with a predominance of generalized disorders, known as Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome. Tics in such cases are localized in the face, neck, upper and lower extremities and are accompanied by grimaces, opening the mouth, sticking out the tongue, and intense gesticulation. In these cases, this syndrome can be excluded by the coarseness of movement disorders characteristic of it and more complex in structure and more severe mental disorders.

In these cases, this syndrome can be excluded by the coarseness of movement disorders characteristic of it and more complex in structure and more severe mental disorders.

Genetic factors

Speaking about hereditary predisposition to OCD, it should be noted that obsessive-compulsive disorders are found in approximately 5-7% of parents of patients with such disorders. Although this figure is low, it is higher than in the general population. While the evidence for a hereditary predisposition to OCD is still uncertain, psychasthenic personality traits can be largely explained by genetic factors.

FORECAST

Approximately two-thirds of OCD patients improve within a year, more often by the end of this period. If the disease lasts more than a year, fluctuations are observed during its course - periods of exacerbations are interspersed with periods of improvement in health, lasting from several months to several years. The prognosis is worse if we are talking about a psychasthenic personality with severe symptoms of the disease, or if there are continuous stressful events in the patient's life. Severe cases can be extremely persistent; for example, a study of hospitalized patients with OCD found that three-quarters of them remained symptom-free 13 to 20 years later.

Severe cases can be extremely persistent; for example, a study of hospitalized patients with OCD found that three-quarters of them remained symptom-free 13 to 20 years later.

TREATMENT: BASIC METHODS AND APPROACHES

Despite the fact that OCD is a complex group of symptom complexes, the principles of treatment for them are the same. The most reliable and effective method of treating OCD is considered to be drug therapy, during which a strictly individual approach to each patient should be manifested, taking into account the characteristics of the manifestation of OCD, age, gender, and the presence of other diseases. In this regard, we must warn patients and their relatives against self-treatment. If any disorders similar to mental ones appear, it is necessary, first of all, to contact the specialists of the psycho-neurological dispensary at the place of residence or other psychiatric medical institutions to establish the correct diagnosis and prescribe competent adequate treatment. At the same time, it should be remembered that at present a visit to a psychiatrist does not threaten with any negative consequences - the infamous "accounting" was canceled more than 10 years ago and replaced by the concepts of consultative and medical care and dispensary observation.

At the same time, it should be remembered that at present a visit to a psychiatrist does not threaten with any negative consequences - the infamous "accounting" was canceled more than 10 years ago and replaced by the concepts of consultative and medical care and dispensary observation.

When treating, it must be borne in mind that obsessive-compulsive disorders often have a fluctuating course with long periods of remission (improvement). The apparent suffering of the patient often seems to call for vigorous effective treatment, but the natural course of the condition must be kept in mind in order to avoid the typical error of over-intensive therapy. It is also important to consider that OCD is often accompanied by depression, the effective treatment of which often leads to an alleviation of obsessional symptoms.

The treatment of OCD begins with an explanation of the symptoms to the patient and, if necessary, with reassurance that they are the initial manifestation of insanity (a common concern for patients with obsessions). Those suffering from certain obsessions often involve other family members in their rituals, so relatives need to treat the patient firmly, but sympathetically, mitigating the symptoms as much as possible, and not aggravating it by excessive indulgence in the sick fantasies of patients.

Those suffering from certain obsessions often involve other family members in their rituals, so relatives need to treat the patient firmly, but sympathetically, mitigating the symptoms as much as possible, and not aggravating it by excessive indulgence in the sick fantasies of patients.

Drug therapy

The following therapeutic approaches exist for the currently identified types of OCD. Of the pharmacological drugs for OCD, serotonergic antidepressants, anxiolytics (mainly benzodiazepine), beta-blockers (to stop autonomic manifestations), MAO inhibitors (reversible) and triazole benzodiazepines (alprazolam) are most often used. Anxiolytic drugs provide some short-term relief of symptoms, but should not be given for more than a few weeks at a time. If anxiolytic treatment is required for more than one to two months, small doses of tricyclic antidepressants or small antipsychotics sometimes help. The main link in the treatment regimen for OCD, overlapping with negative symptoms or ritualized obsessions, are atypical antipsychotics - risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, in combination with either SSRI antidepressants or other antidepressants - moclobemide, tianeptine, or with high-potency benzodiazepine derivatives ( alprazolam, clonazepam, bromazepam).

Any comorbid depressive disorder is treated with antidepressants at an adequate dose. There is evidence that one of the tricyclic antidepressants, clomipramine, has a specific effect on obsessive symptoms, but the results of a controlled clinical trial showed that the effect of this drug is insignificant and occurs only in patients with distinct depressive symptoms.

In cases where obsessive-phobic symptoms are observed within the framework of schizophrenia, intensive psychopharmacotherapy with proportional use of high doses of serotonergic antidepressants (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram) has the greatest effect. In some cases, it is advisable to connect traditional antipsychotics (small doses of haloperidol, trifluoperazine, fluanxol) and parenteral administration of benzodiazepine derivatives.

Psychotherapy

Behavioral psychotherapy

One of the main tasks of the specialist in the treatment of OCD is to establish fruitful cooperation with the patient. It is necessary to instill in the patient faith in the possibility of recovery, to overcome his prejudice against the "harm" caused by psychotropic drugs, to convey his conviction in the effectiveness of treatment, subject to the systematic observance of the prescribed prescriptions. The patient's faith in the possibility of healing must be supported in every possible way by the relatives of the OCD sufferer. If the patient has rituals, it must be remembered that improvement usually occurs when using a combination of the method of preventing a reaction with placing the patient in conditions that aggravate these rituals. Significant but not complete improvement can be expected in about two-thirds of patients with moderately heavy rituals. If, as a result of such treatment, the severity of rituals decreases, then, as a rule, the accompanying obsessive thoughts also recede. In panphobia, predominantly behavioral techniques are used to reduce sensitivity to phobic stimuli, supplemented by elements of emotionally supportive psychotherapy.

It is necessary to instill in the patient faith in the possibility of recovery, to overcome his prejudice against the "harm" caused by psychotropic drugs, to convey his conviction in the effectiveness of treatment, subject to the systematic observance of the prescribed prescriptions. The patient's faith in the possibility of healing must be supported in every possible way by the relatives of the OCD sufferer. If the patient has rituals, it must be remembered that improvement usually occurs when using a combination of the method of preventing a reaction with placing the patient in conditions that aggravate these rituals. Significant but not complete improvement can be expected in about two-thirds of patients with moderately heavy rituals. If, as a result of such treatment, the severity of rituals decreases, then, as a rule, the accompanying obsessive thoughts also recede. In panphobia, predominantly behavioral techniques are used to reduce sensitivity to phobic stimuli, supplemented by elements of emotionally supportive psychotherapy. In cases where ritualized phobias predominate, along with desensitization, behavioral training is actively used to help overcome avoidant behavior. Behavioral therapy is significantly less effective for obsessive thoughts that are not accompanied by rituals. Thought-stopping has been used by some experts for many years, but its specific effect has not been convincingly proven.

In cases where ritualized phobias predominate, along with desensitization, behavioral training is actively used to help overcome avoidant behavior. Behavioral therapy is significantly less effective for obsessive thoughts that are not accompanied by rituals. Thought-stopping has been used by some experts for many years, but its specific effect has not been convincingly proven.

Social rehabilitation

We have already noted that obsessive-compulsive disorder has a fluctuating (fluctuating) course and over time the patient's condition may improve regardless of which particular methods of treatment were used. Until recovery, patients can benefit from supportive conversations that provide continued hope for recovery. Psychotherapy in the complex of treatment and rehabilitation measures for patients with OCD is aimed at both correcting avoidant behavior and reducing sensitivity to phobic situations (behavioral therapy), as well as family psychotherapy to correct behavioral disorders and improve family relationships. If marital problems exacerbate symptoms, joint interviews with the spouse are indicated. Patients with panphobia (at the stage of the active course of the disease), due to the intensity and pathological persistence of symptoms, need both medical and social and labor rehabilitation. In this regard, it is important to determine adequate terms of treatment - long-term (at least 2 months) therapy in a hospital with subsequent continuation of the course on an outpatient basis, as well as taking measures to restore social ties, professional skills, family relationships. Social rehabilitation is a set of programs for teaching OCD patients how to behave rationally both at home and in a hospital setting. Rehabilitation is aimed at teaching social skills to properly interact with other people, vocational training, as well as skills necessary in everyday life. Psychotherapy helps patients, especially those who experience a sense of their own inferiority, treat themselves better and correctly, master ways to solve everyday problems, and gain confidence in their strength.

If marital problems exacerbate symptoms, joint interviews with the spouse are indicated. Patients with panphobia (at the stage of the active course of the disease), due to the intensity and pathological persistence of symptoms, need both medical and social and labor rehabilitation. In this regard, it is important to determine adequate terms of treatment - long-term (at least 2 months) therapy in a hospital with subsequent continuation of the course on an outpatient basis, as well as taking measures to restore social ties, professional skills, family relationships. Social rehabilitation is a set of programs for teaching OCD patients how to behave rationally both at home and in a hospital setting. Rehabilitation is aimed at teaching social skills to properly interact with other people, vocational training, as well as skills necessary in everyday life. Psychotherapy helps patients, especially those who experience a sense of their own inferiority, treat themselves better and correctly, master ways to solve everyday problems, and gain confidence in their strength.