Feelings of hope

Hope Psychology: What Are The Benefits of Hope?

Hope Psychology: What Are The Benefits of Hope? | Psych Central- Conditions

- Featured

- Addictions

- Anxiety Disorder

- ADHD

- Bipolar Disorder

- Depression

- PTSD

- Schizophrenia

- Articles

- Adjustment Disorder

- Agoraphobia

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Childhood ADHD

- Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder

- Narcolepsy

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- Panic Attack

- Postpartum Depression

- Schizoaffective Disorder

- Seasonal Affective Disorder

- Sex Addiction

- Specific Phobias

- Teenage Depression

- Trauma

- Featured

- Discover

- Wellness Topics

- Black Mental Health

- Grief

- Emotional Health

- Sex & Relationships

- Trauma

- Understanding Therapy

- Workplace Mental Health

- Original Series

- My Life with OCD

- Caregivers Chronicles

- Empathy at Work

- Sex, Love & All of the Above

- Parent Central

- Mindful Moment

- News & Events

- Mental Health News

- COVID-19

- Live Town Hall: Mental Health in Focus

- Podcasts

- Inside Mental Health

- Inside Schizophrenia

- Inside Bipolar

- Wellness Topics

- Quizzes

- Conditions

- ADHD Symptoms Quiz

- Anxiety Symptoms Quiz

- Autism Quiz: Family & Friends

- Autism Symptoms Quiz

- Bipolar Disorder Quiz

- Borderline Personality Test

- Childhood ADHD Quiz

- Depression Symptoms Quiz

- Eating Disorder Quiz

- Narcissim Symptoms Test

- OCD Symptoms Quiz

- Psychopathy Test

- PTSD Symptoms Quiz

- Schizophrenia Quiz

- Lifestyle

- Attachment Style Quiz

- Career Test

- Do I Need Therapy Quiz?

- Domestic Violence Screening Quiz

- Emotional Type Quiz

- Loneliness Quiz

- Parenting Style Quiz

- Personality Test

- Relationship Quiz

- Stress Test

- What's Your Sleep Like?

- Conditions

- Resources

- Treatment & Support

- Find Support

- Suicide Prevention

- Drugs & Medications

- Find a Therapist

- Treatment & Support

Medically reviewed by Kendra Kubala, PsyD, Psychology — By Traci Pedersen — Updated on Sep 26, 2022

Hope is more than wishful thinking. It’s a blend of optimism and willpower.

You have $1.79 in your bank account, your rent is due today, and you don’t get paid for a week. Is it still possible to have hope that your finances will improve?

Absolutely. Hope can exist even alongside the most difficult situations and emotions. Hope is much more than wishful thinking, as it requires optimism and willpower.

Hope is a state of mind that can be learned.

Hope is the belief that your future will be better than the present and that you have the ability to make it happen. It involves both optimism and a can-do attitude.

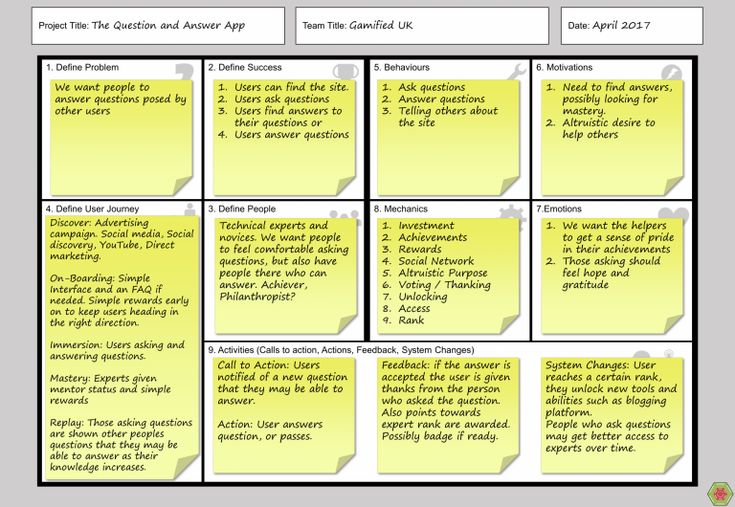

This definition of hope is based on “Hope Theory,” a positive psychology concept developed by American psychologist Charles Snyder.

Positive psychology is the scientific study of what makes life worth living. This branch of psychology focuses on developing strengths and positive traits rather than healing weaknesses or disease.

According to hope theory, hope has three distinct parts:

- Goals.

Having a goal is the cornerstone of hope. Goals can be big or small. You can have a goal to go to college or to begin practicing yoga.

Having a goal is the cornerstone of hope. Goals can be big or small. You can have a goal to go to college or to begin practicing yoga. - Agency (willpower). Agency is the ability to stay motivated to meet your goal. It involves believing that good things will come from your actions.

- Pathways. These are the specific routes you develop to meet your goals. If your first pathway doesn’t work, you problem-solve to find a new pathway. High-hope people understand that roadblocks are inevitable and that it might take several tries to reach your goals.

While hope certainly involves our emotions, hope itself is not an emotion. Hope is a way of thinking or a state of being. This means that hope can be taught.

Hope is also distinct from a wish. Hope involves taking action toward a goal, while a wish is out of your control. For instance, if you’re at a restaurant and say, “I hope my food comes out hot,” that’s actually a wish because you have no control over it.

There are two types of goal outcomes in hope theory: positive (the presence of something) and negative (the absence of something).

Type 1: Positive goal outcome

- Reaching a goal for the first time. You want to buy a new car.

- Sustaining a present goal. You want to continue making payments on your car so you can keep it.

- Increasing something that’s already begun. You want to become a better driver.

Type 2: Negative goal outcome

- Deterring something so that it never happens. You eat fruits and vegetables every day to avoid getting sick.

- Deterring something so that it is delayed. You ask for a payment extension, so you don’t have to pay your bill yet.

Hope theory trains you to unlock hope in all life areas, including exceptional and mundane situations.

Example 1. John is severely depressed and has been in bed for three days. He knows he’ll feel better if he can get more active today.

Goal. John makes a goal to be a little more active today.

Agency. It’s hard to have willpower with depression, but John motivates himself with the fact that he’ll feel better if he gets out of bed.

Pathways. John makes a plan to take a hot shower, cook a small breakfast, and take a walk around the block. If one of these pathways fails, perhaps he’ll write in his journal or call a friend.

Example 2. Jenny just found out she has diabetes. While the news is sudden and unnerving, she’s determined to stay hopeful.

Goal. Jenny makes a goal to get as healthy as possible.

Agency. She takes inventory of her motivation. She knows her goal is achievable if she perseveres. She knows she wants to get well for her loved ones and herself.

Pathways. Jenny develops several different strategies to meet her goal of getting healthy. She develops a healthy eating plan, a daily exercise regimen, and decides to learn all she can about diabetes.

High-hope people fare better in several areas of life.

According to Snyder’s hope theory, higher levels of hope are consistently linked to better outcomes regarding mental health, physical health, academics, athletics, physical health, and psychotherapy.

Psychological benefits of hopeHigh-hope people tend to have higher levels of overall well-being.

In one study, researchers looked at hope and well-being in a sample of nearly 13,000 participants. The team discovered that high-hope participants reported the following:

- more positive emotions

- stronger sense of purpose and meaning

- lower levels of depression

- less loneliness

In the same study of nearly 13,000 participants, researchers found that high levels of hope also made an impact on physical health.

According to the findings, high-hope people experienced the following:

- better physical health

- reduced risk of all-cause mortality

- fewer number of chronic illnesses

- lower risk of cancer

- fewer sleep problems

As mentioned above, having high levels of hope is linked to less loneliness. Having more positive emotions can also help you develop stronger relationships with others.

In a 6-year study of 975 adolescents (grades 7-12), hope predicted future well-being, particularly in important transition years (starting high school). The researchers determined that hope is an important attribute that encourages positive youth development.

The good news is that hope is a learned skill, and just about anyone can learn to be more hopeful.

- Think of your goals as exciting challenges. Consistently imagine how you’ll feel when you get there.

- Be flexible and creative.

When brainstorming your pathways, develop a Plan A, B, C, D, etc.

When brainstorming your pathways, develop a Plan A, B, C, D, etc. - Increase your motivation. What strengths can you draw on to achieve your goals? What is currently working for you? When were you successful in similar situations and why?

- Expect roadblocks. Remember that most things of value don’t come easily.

- Persist, even under stressful conditions. This will help develop your coping skills which will continue to help you reach your goals under pressure.

- Take it one step at a time. If you’re struggling to reach your goals, think of one small step you can take each day.

- Keep your goals high but realistic. False hope is actually a result of low hope.

- Turn to humor. When you’re feeling hopeless, watch a funny movie. A 2003 study found that laughter can increase our levels of hope.

- Gain strength from others. When you feel discouraged, listen to an inspiring podcast or read the memoir of someone who’s overcome overwhelming obstacles.

Hope is the belief that your future will be better than today and that you’re able to make it happen. It involves optimism, motivation, and strategy.

The best part about hope is that it’s a learned skill. With practice, you can develop a hopeful attitude which will improve your mental and physical health and even reduce your risk of death.

If you start to lose hope, remember that you are not alone. You can always reach out to loved ones for help or speak with a therapist to develop strategies to regain your hope.

Last medically reviewed on September 25, 2022

4 sourcescollapsed

- Ciarrochi J, et al. (2015). Hope and emotional well-being: A six-year study to distinguish antecedents, correlates, and consequences.

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17439760.2015.1015154?journalCode=rpos20 - Long K NG, et al. (2020). The role of Hope in subsequent health and well-being for older adults: An outcome-wide longitudinal approach.

sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S259011332030002X?via%3Dihub - Snyder CR. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind.

jstor.org/stable/1448867 - Vilaythong AP, et al. (2003). Humor and hope: Can humor increase hope?

degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/humr.2003.006/html

FEEDBACK:

Medically reviewed by Kendra Kubala, PsyD, Psychology — By Traci Pedersen — Updated on Sep 26, 2022

Read this next

Mindful Moment: Awakening to the Power of Hope

Medically reviewed by Karin Gepp, PsyD

Hope is about being in the present moment. Mindfulness teacher La Sarmiento offers tips on finding hope within yourself.

READ MORE

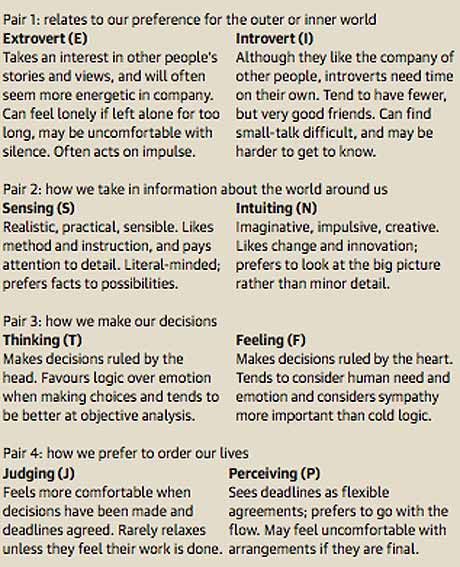

Emotional Personality Type Test

Medically reviewed by Vara Saripalli, PsyD

What is your emotional type? Take our quiz and find out how you might likely react to different situations and how to best navigate your current one.

READ MORE

12 Journal Prompts for Emotional Health and Awareness

Using journal prompts can help you explore and understand your feelings and emotions. It can also help you heal.

READ MORE

How to Listen Without Giving Advice

If you're conversing with someone, empathizing with their story and listening without judgment can help them feel safe to be vulnerable with you.

READ MORE

8 Ways to Cope If You Feel Like Giving Up

Medically reviewed by Kendra Kubala, PsyD

If you experience thoughts or feelings about suicide or self-harm, support, like the 988 helpline, is available. You're not alone.

READ MORE

8 Ways to Avoid Codependency in Your Relationships

In codependent relationships, one person sacrifices more than the other.

But assertive communication and creating boundaries can reduce codependency…

But assertive communication and creating boundaries can reduce codependency…READ MORE

How to Stop "Obsessing" Over a Lost Friendship

Friendships may end due to a lack of trust and frequent misunderstandings. Tips, like prioritizing self-care and expressing how you feel may help you…

READ MORE

How Long Does It Take to Form a Habit?

Building or breaking a new habit in 21 days is a myth. But recent research suggests that it can take about 59 to 70 days for someone to form a new…

READ MORE

The Psychology of Oppositional Conversational Styles

Medically reviewed by Matthew Boland, PhD

Oppositional conversation style is a term used to describe a type of communication where a person contradicts everything you say. Here's how to deal…

READ MORE

How Does Social Media Affect Body Image?

Medically reviewed by Karin Gepp, PsyD

Social media can negatively and positively impact on body image.

Being aware of how social media content can affect you may help improve your…

Being aware of how social media content can affect you may help improve your…READ MORE

The Power of Hope, and Recognizing When It's Hopeless

Hope structures your life in anticipation of the future and influences how you feel in the present. Similar to optimism, hope creates a positive mood about an expectation, a goal, or a future situation. Such mental time travel influences your state of mind and alters your behavior in the present. The positive feelings you experience as you look ahead, imagining hopefully what might happen, what you will attain, or who you are going to be, can alter how you currently view yourself. Along with hope comes your prediction that you will be happy, and this can have behavioral consequences.

Hope shapes your methods of traversing your current situation. The cognitions associated with hope—how you think when you are hopeful—are pathways to desired goals and reflect a motivation to pursue goals (Snyder, Harris, Anderson, & Holleran, 1991). Better problem-solving abilities have been found in people who are hopeful when compared with low-hope peers (Change, 1998), and those who are hopeful have a tendency to be cognitively flexible and are able to mentally explore novel situations (Breznitz, 1986).

Better problem-solving abilities have been found in people who are hopeful when compared with low-hope peers (Change, 1998), and those who are hopeful have a tendency to be cognitively flexible and are able to mentally explore novel situations (Breznitz, 1986).

Technically, hope does not fit the criteria as an emotion. These criteria include the concept that emotions are automatic and reflexive, they cause physical and behavioral changes as a result of nervous system responses, and that they provide you with immediate information about a situation that can lead you to take action.

Although the concept of hope does not meet these criteria, papers on the subject that have been published in reputable psychological journals have referred to it as an emotional state. Lazarus (1999), for example, has explored the role of hope as an emotion and as a coping resource against despair. Perhaps hope is better understood as a cognition that creates a certain mood—a prolonged affective state—lacking the immediacy and intensity of reflexive emotions, yet capable of determining one's outlook on life.

Having hope is to imagine a positive outcome. The directive of many motivational principles is to visualize what you want and imagine positive outcomes so that your behavior is unconsciously structured to create them. However, one does not need to turn to quantum explanations in order to account for the positive effects of hope.

Unconscious thought theory postulates that we are able to process information--to get your brain to work on a problem--in a non-conscious way that can lead to bursts of insight (Dijksterhuis & Nordgren, 2006). Most of the things we do are unconsciously processed. Thus, considering your endeavors before bedtime, or even going over your to-do list, is worthwhile since your brain is sensitive to your conscious perception of future events and will unconsciously work toward your goals.

Clinical drug trials are a good example of the power of hope. In clinical drug trials, a medication is compared with an inactive substance, commonly referred to as a placebo. Recent studies of antidepressants doubt their efficacy when compared to a placebo in double-blind, randomized clinical trials. What's most notable is that in clinical trials where the placebo is engineered to produced side-effects, causing those who take it to believe that they are on the actual medication, the efficacy of the placebo is similar to that of the medication (Angell, 2011). In a discussion of these studies a friend suggested that, rather than referring to such inactive substances as a placebo, they should instead be called "hope."

Recent studies of antidepressants doubt their efficacy when compared to a placebo in double-blind, randomized clinical trials. What's most notable is that in clinical trials where the placebo is engineered to produced side-effects, causing those who take it to believe that they are on the actual medication, the efficacy of the placebo is similar to that of the medication (Angell, 2011). In a discussion of these studies a friend suggested that, rather than referring to such inactive substances as a placebo, they should instead be called "hope."

The way in which a hopeful person handles disappointment differs from those who are not. Even if the present is unpleasant, the thought of a positive future can be stress-buffering and can reduce the impact of negative events or disappointment. Being unrelentingly optimistic about the future helps you to recognize that you are adaptable and capable, enabling you to reassure yourself that you will get through a tough time. Having a powerful hope that you will adapt also provides a limitlessly positive version of the future. Those who are hopeful and optimistic can make excuses for negative outcomes, while the pessimist may become resentful or negatively preoccupied.

Those who are hopeful and optimistic can make excuses for negative outcomes, while the pessimist may become resentful or negatively preoccupied.

In relationships, there are times when abandoning hope is psychologically healthier than holding onto it. My co-author and I wrote about such situations in our book, The White Knight Syndrome: Rescuing Yourself From Your Need to Rescue Others (Lamia & Krieger, 2009).

In ending a relationship, relinquishing hope means coming to terms with your failure. In a rescuing relationship, hope may have led you to assume that you could help your partner achieve his expressed goal: be it financial success, sobriety, security, or happiness. Yet despite your efforts, you could not control whether or not he would be inclined to pursue your perception of a desirable path. Perhaps your hope was that your partner would become the one you wanted or wished him to be, and he would then need, love, and appreciate you. Relinquishing hope is hard to do because it means that you have failed to get what you expected from your relationship.

The feelings associated with giving up hope in a relationship are often the very same emotions you sought to avoid in the first place, including helplessness, despair, depression, or yearning that are the negative counterparts of hope (Lazarus 1999). Yet giving up hope can also be very constructive and positive, depending on your attitude.

Giving up hope is sometimes prudent in situations where turning your attention elsewhere is necessary in order to actually reach your goal. Continuing to pursue a particular direction where you invariably encounter roadblocks, whether in a relationship, career, or business venture, can obscure other avenues that may lead to achieving an objective.

In our culture, there is a particular glamour attributed to those who persist and win, in spite of limited hope for success. At the same time, having the strength to recognize when hope should be relinquished, and the courage to acknowledge your helplessness, can point you in an unsullied direction that is accompanied by new hope.

For more information regarding my books about emotions, see my website.

This blog post is in no way intended as a substitute for medical or psychological counseling. If expert assistance or counseling is needed, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

What is hope and why is it so important?

Well, that's all, the end. Cold and hopeless. Sometimes it seems that this news will never end - and there is no hope that it will get better in the new year. And if so, let's talk about hope?

And here it is worth rewinding. For two years now, we have been trying to survive the pandemic, and this is what a paradoxical thing is happening: on the one hand, we are the first to throw out masks and have parties at the next peak of the sick, and on the other hand, the anxious sprint “wish all this would end soon” of 2020 turned into an endless and exhausting marathon of 2021. “Will it end? And when? What if it's never? - as if in 2020 hope glimmered and helped to live, and in 2021 it turned out to be overshadowed by fatigue and some new frightening hopelessness. And then there are the regular questions that pop up every December like a devil out of a box: “A year has passed again, and what have you achieved?” - and outside the window is the darkest time of the year. In response, we reflexively run outside, into the team, light the lights, take pictures of each other against the backdrop of New Year's decorations. Like the ancient northern peoples, we do not let darkness win and we are waiting for the return of the sun, but this is not enough for a very long time. And what to do when you either ran away on New Year's Eve, having come up with predictable ritual actions (friends-dacha-party-vacation-bar-club-karaoke-relatives), or stayed at home alone, but the New Year's mood still won't come, but instead of him, something inside shrinks from anxiety before the future? What to do with it? What to hope for? How to survive until spring? How does hope work? Oh, it's full of surprises - let's figure it out together.

And then there are the regular questions that pop up every December like a devil out of a box: “A year has passed again, and what have you achieved?” - and outside the window is the darkest time of the year. In response, we reflexively run outside, into the team, light the lights, take pictures of each other against the backdrop of New Year's decorations. Like the ancient northern peoples, we do not let darkness win and we are waiting for the return of the sun, but this is not enough for a very long time. And what to do when you either ran away on New Year's Eve, having come up with predictable ritual actions (friends-dacha-party-vacation-bar-club-karaoke-relatives), or stayed at home alone, but the New Year's mood still won't come, but instead of him, something inside shrinks from anxiety before the future? What to do with it? What to hope for? How to survive until spring? How does hope work? Oh, it's full of surprises - let's figure it out together.

What is learned helplessness and how to get rid of it

Advertising on RBC www. adv.rbc.ru

adv.rbc.ru

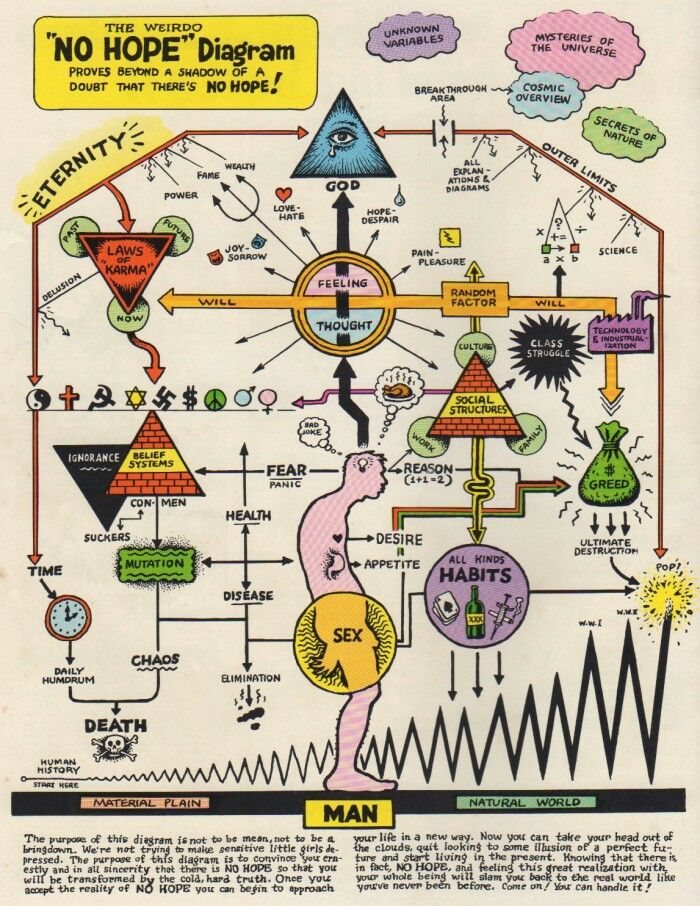

Let's start with the fact that hope is not something that is given so much attention in psychology. Russian-speaking authors mainly refer to foreign sources, and this is not popular literature. But it is easy to find a lot of memes about decay.

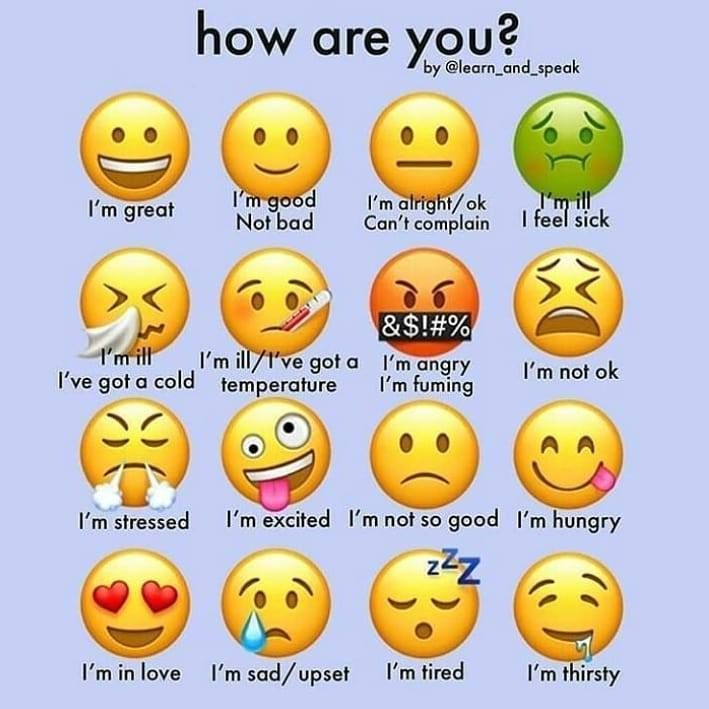

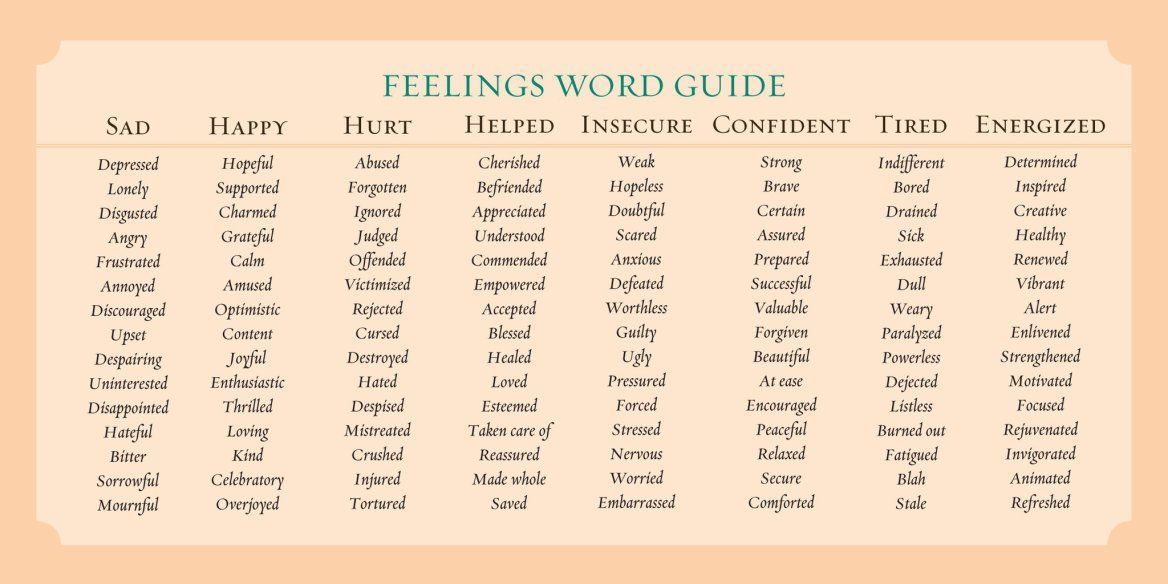

Nevertheless, hope is a complex abstract concept, philosophical and psychological. If we consider it as a psychological experience, there are different feelings inside: excitement, expectation (of something or someone desired), excitement from this expectation, anticipation - and an imaginary result in the head at that moment, joy of various shades, fear that the plan will not come true, sometimes anger - at the circumstances that are now, and at what may be.

Perhaps the most important component of hope is faith. Hope is an expectation, and within it is necessarily faith, something that is expected is possible. The authors beat their hands so as not to turn this text into a quote book, but Erich Fromm spoke beautifully about this: “Hope is the frame of mind that accompanies faith. Faith could not endure without a spirit of hope. Hope has no other basis than faith." When faith leaves, the hope wrapped around it darkens and begins to die, like the bark of a tree that has rotted at the core. But if faith remains, hope will also survive. We hope that our possibilities will be the best, and we believe and hope where our possibilities end. And here is the first life hack about hope.

Faith could not endure without a spirit of hope. Hope has no other basis than faith." When faith leaves, the hope wrapped around it darkens and begins to die, like the bark of a tree that has rotted at the core. But if faith remains, hope will also survive. We hope that our possibilities will be the best, and we believe and hope where our possibilities end. And here is the first life hack about hope.

1. The main thing is to survive the dark time, and then a new hope will appear

Morning will come after the night, spring will come after the winter, dawn will also dawn after the dark streak, the main thing here is to hold out and endure. The most striking examples of the hope that the dark time will end are the very cyclical nature, and also examples from the bright and wise books of those who survived the darkest moments of human history: life in a concentration camp. “If I survive today, tomorrow I will be free,” writes Auschwitz survivor Edith Eva Eger in The Choice, and it is hard to disagree with her. She did it, and so can we. But how?

She did it, and so can we. But how?

In general, hope is an integral part of a person who is given imagination. At the opposite pole from hope lies hopelessness, despair and the coldness of nothingness, and one cannot do without imagination.

2. Concentration camp survivors turned to the inner world - it cannot be taken away! This is what supported them

Even when everything outside is taken away, there always remains an inner world that no one will take away from you. You have a lot left - reason, imagination, intellect - and hope along with faith. A person survives in the most hopeless situations if he turns to his inner world.

3. Humor comes to the rescue here too. After all, humor is our protection from death

This is how Viktor Frankl, the creator of logotherapy, one of the branches of existential psychology, recalls life in the camp: “...So illusions collapsed, one after another. And then something unexpected appeared: black humor. After all, we realized that we had nothing to lose, except for this ridiculously naked body. Even under the shower, we began to exchange humorous (or pretending to be) remarks to cheer each other up and, above all, ourselves. There was some reason for this - after all, water really comes out of the taps!

Even under the shower, we began to exchange humorous (or pretending to be) remarks to cheer each other up and, above all, ourselves. There was some reason for this - after all, water really comes out of the taps!

Well, there is inner peace and humor, what to do next?

4. Changes need to be arranged by yourself

Holidays with holidays and rituals are wonderful, but if they remain empty for us, we risk being disappointed - the case when the New Year's table is set, but the salad does not warm the soul, and Christmas decorations like would be beautiful, but they do not bring joy. It is bitter to admit that you are marking time and taking comfort in ritual, socially accepted actions - and then it is worth gaining courage and thinking about change. Well, in order for change to really begin, sometimes you need to face reality.

How to fix a bad New Year and what to do about a bad mood

5. Sometimes hope can and should be lost

There are times when hope turns out to be a kind of escape into an illusion: that our partner will stop drinking after the New Year, dad will stop let go of caustic comments about success at work, the girl will return . .. in general, things will happen that have not depended on you for a long time. In this place, it is time to face the reality of life, in which the loss of hope is inevitable, and with it the loss of the image of the future that could happen. The loss of hope is also a loss that we grieve in earnest. Yes, the partner will continue to drink, the father with caustic comments can no longer be changed (until he himself wants to change), and the girl has long continued to live her life. It is bittersweet, but the truth is that saying goodbye and mourning are complex but finite processes, as opposed to endless hope. And the border of the year - new or personal - is a good reason to say goodbye to something or someone, first of all - to your own illusions. And go further.

.. in general, things will happen that have not depended on you for a long time. In this place, it is time to face the reality of life, in which the loss of hope is inevitable, and with it the loss of the image of the future that could happen. The loss of hope is also a loss that we grieve in earnest. Yes, the partner will continue to drink, the father with caustic comments can no longer be changed (until he himself wants to change), and the girl has long continued to live her life. It is bittersweet, but the truth is that saying goodbye and mourning are complex but finite processes, as opposed to endless hope. And the border of the year - new or personal - is a good reason to say goodbye to something or someone, first of all - to your own illusions. And go further.

6. The main thing is to go slowly

There is a risk of promising yourself from the first of January to start going to the gym, go on a diet, update your resume - well, before the new year, buy advent calendars and sign up for several online marathons, so that the test will definitely happen in the head, but is it necessary to say that in this case you are likely to be disappointed?

We change slowly and reluctantly - that's the way we are. I want everything and quickly, but here it’s better not to succumb to the New Year’s hysteria, be patient, exhale and carefully plan everything a little bit. Then what you want will work for sure. And what to do in the remaining time?

I want everything and quickly, but here it’s better not to succumb to the New Year’s hysteria, be patient, exhale and carefully plan everything a little bit. Then what you want will work for sure. And what to do in the remaining time?

I solemnly swear: Hailey Bieber and other stars about New Year's resolutions

7. Celebrate together

In addition to the understandable idea that adults arrange a holiday only for themselves, ancient traditions have always been about togetherness. Sometimes it can be difficult to get out of the cocoon of your own complex feelings - and it is especially difficult at the turn of the year - but together it will definitely be easier to light fires and share what is on your heart. If you understand that on New Year's Eve you risk being alone, write to the same lonely people and celebrate together.

The main thing about hope in questions and answers

- How to come to terms with the fact that again not everything came true?

- But what about the fact that I have really high demands?

- But you really want everything at once!

- But you want something very, very much! I want unbearably!

- Why this hope at all? Isn't it easier to just take and do

- What if I lose hope?

- What to do if loved ones lose hope?

Even if you do not sum up the results of the year, no, no, and you will think - what did I do during the year, and what was important? And if the hopes did not come true, something important did not happen, usually we are faced with disappointment, which we really want to avoid. What to do with it?

What to do with it?

How to come to terms with the fact that again not everything came true?

The main thing is not to compare yourself with anyone. Someone bought an apartment, grew up at work, made a cool project, gave birth to two children - and all in one year.

Firstly, we never know exactly how this lord of life spent his last years - perhaps he tried, struggled, changed, did something, despaired, faced disappointment and hoped for the best for several years in a row - it just wasn't that noticeable.

Secondly, to compare yourself with someone is to be better or worse all the time, and it's hard, but to deny your own changes, your own progress, even a little, it means never to recognize any progress, because there will always be someone who is faster and better. In this case, there is a risk that satisfaction will not come, even if you move mountains.

It could be different. Try to look back: you will see that somewhere you were good, and somewhere you did something good. Appreciating what is, and at the same time continue to desire, is a great ability, on which our quality of life and satisfaction with it ultimately depends.

Appreciating what is, and at the same time continue to desire, is a great ability, on which our quality of life and satisfaction with it ultimately depends.

But what about the fact that I have really high demands?

To come to terms with the fact that the more expectations we have from ourselves and from the world, the higher the requirements and the more they diverge from our real capabilities, from reality in general, the more likely disappointment comes, and the more painful it can be.

But you really want everything at once!

Let's talk more about unrealistic expectations. The reality of human life is that change doesn't happen on calendar dates, and we don't change that quickly. This fact is often ignored - and in vain.

When we envy someone else's and very noticeable success, we often do not notice how much it actually took to achieve it. And it could have been years of quiet, hard and invisible work.

Some goals and changes need to be given more time, and here it is important not to hang everything that has not come true on one next date. Otherwise, there is a risk that it will again not be about reality and will most likely lead to even greater disappointment next time.

Otherwise, there is a risk that it will again not be about reality and will most likely lead to even greater disappointment next time.

But you really, really want to! I want unbearably!

Behind any goal and desire, there are actually some needs. And if your goal is not achieved, especially for several years in a row, take a closer look at it: in fact, why do you want this?

Understanding one's needs does not cancel goals, but helps to better see opportunities and use them.

For example, behind the goal of buying a car there may be a need for comfort, independence, security, sometimes time savings, and sometimes even love. Or, behind the goal, there may be an old picture in your head, some obsolete plan - once this car gave the feeling “everything is ok with me”, but is it relevant now?

And one more question that you should ask yourself: what would everything that didn't come true cost you if it came true? What would you pay to win? Money, strength, concentration?

Sometimes it's hard to honestly admit to yourself that you really wanted a new apartment, but all you could do this year was save up for a down payment, and not now, but in five years. The question about your own resources and limitations is very important: it can be difficult and bitter to admit honestly what exactly you spent your time and energy and attention and resources on in the past year. But sometimes it's necessary.

The question about your own resources and limitations is very important: it can be difficult and bitter to admit honestly what exactly you spent your time and energy and attention and resources on in the past year. But sometimes it's necessary.

Give way to disappointment, followed by sadness. Let go of the unfulfilled - when, if not in the New Year? Leave the past in the past and move on.

Why this hope at all? Isn't it easier to just take it and do it?

Hope as a component of an optimistic view of the world is rather a useful function of our imagination, which provides an image of the future and motivation. In difficult life situations, hope is not called upon to put rose-colored glasses on a person, but allows for any possibilities, allows for probability. This, for example, is the hope to survive the war, to go through a really dark period of life - and here his inner mood, composure depend on a person, but in external circumstances he is not able to change anything.

There is another kind of hope — dreamy, passive, denying reality and making a person wait for everything to happen or pass by itself. She's just bad. This is the hope of a person who is waiting for the partner to stop cheating, and at work someday they will stop delaying their salary for two months. In this situation, the choice remains: you can leave the relationship and quit your job. Hope in such situations is almost always present, and it becomes a defense against that part of reality that is difficult to bear. And it is based on no longer relevant memories and rare happy moments. The main thing here is this: miracles happen, but if you stay in a situation where you can actually change something, there is a risk of staying in it forever, defending yourself with an illusion.

What if I lose hope?

The loss of hope is the loss of the image of a future in which everything will be fine. And this hope is never lost alone, by itself - the feeling of support is lost, faith is lost.

In such a situation, many things can help you move on and not lose hope: support from loved ones, humor, desires, faith, inner peace, meanings, past experience and specific actions. The more such supports a person has, the easier it is to cope and hope. In difficult times, it always helps to remember that there have already been trials in life that you have passed. If you believe in something - whether in God, in progress, in science, in human strength, reason - and find meaning in it every time, all this gives hope.

Do not underestimate humor - it helps in both simple and difficult life situations: and as a result, the same story, told and perceived in different ways, can be both a drama and a comedy. Losing hope, just like losing and finding anything at all, is normal, it's part of life.

What to do if loved ones lose hope?

When loved ones lose hope, it's hard, especially when it's hard to keep it yourself. Often you have to experience powerlessness, sometimes despair and even anger, and it takes courage and courage to endure this and stay close.

If you believe that everything will be fine, and difficulties and loss of hope are temporary, this confidence is easier to convey to a person nearby. And sometimes, courage and courage are needed to recognize what is now and the likelihood that it may not be good. And to continue to be near, to share with his loved ones his experiences.

It is very important if you yourself believe in something, if there is a sense in your picture of the world — this can be very supportive of your loved ones in itself. And don't forget that support can also be important to you in such a situation.

“Are you offended?” Where do resentments come from and how to deal with them

Tags: psychology

is activity”: how does it differ from optimism and why is it so important not to lose it?

Did you find something useful here? Help us stay free, independent, and free by making any donation or purchasing some of our literary merchandise.

Hope is a feeling that many are losing today, because there are fewer and fewer reasons for optimism. However, according to psychologist David B. Feldman and oncologist Benjamin V. Cornis, hope is not equal to blind optimism and has completely different sources and potential: it is not a passive feeling, but a psychological basis for activity and the ability to transform one's life, no matter how gloomy it may be. reality. We translated material from Aeon, where experts talk about research and leading theories of hope, as well as what components it consists of and what it can give us.

Melanie, a 47-year-old employee of a leading engineering and construction firm in Boston, couldn't stand looking at a tasteless painting in a doctor's waiting room. Sitting there, she thought back to her college counselor, who had warned her that it would not be easy to succeed in a male-dominated field. But she was a fighter and was not going to stop. The authorities quickly saw this desire, and she was constantly celebrated and given her greater powers. Indeed, her personal and professional lives have been textbook descriptions of how to use ingenuity and wit to overcome inexorable obstacles. But now everything was different. She faced the betrayal of her own body. She was able to cope with unexplained weight loss and a yellow tint that changed the color of her eyes. But then the pain came. Deep, boring, twisting pain. The agony made her seek medical attention, and a week later the examination was completed. Pancreas cancer.

Indeed, her personal and professional lives have been textbook descriptions of how to use ingenuity and wit to overcome inexorable obstacles. But now everything was different. She faced the betrayal of her own body. She was able to cope with unexplained weight loss and a yellow tint that changed the color of her eyes. But then the pain came. Deep, boring, twisting pain. The agony made her seek medical attention, and a week later the examination was completed. Pancreas cancer.

In her office, Dr. Tamika was reviewing the results of the PET scan and contemplating what to say to Melanie. After 20 years of practice, it seemed like it was becoming increasingly difficult to have such conversations. No doubt someone as smart as Melanie Googled the query "pancreatic cancer" and saw the adjectives (deadly, destructive) and clichés ("the tumor that gives oncology its reputation") associated with this malignant tumor. Undoubtedly, she had already learned that a long life with such a diagnosis is possible only in a relatively small percentage of cases. Dr. Tamika wanted to give the patient some hope. But wouldn't it not be entirely true to speak of hope under these circumstances? Perhaps, Dr. Tamika mused, she should talk to Melanie about her goals for the remaining time, preparing her for the likely scenario where death was only a matter of months. It will be more honest, but will Melanie's hope be shattered?

Dr. Tamika wanted to give the patient some hope. But wouldn't it not be entirely true to speak of hope under these circumstances? Perhaps, Dr. Tamika mused, she should talk to Melanie about her goals for the remaining time, preparing her for the likely scenario where death was only a matter of months. It will be more honest, but will Melanie's hope be shattered?

Dr. Tamika's thoughts reflect what we call 'the double-bind of hope'. Oncologists and other doctors who support patients as seriously ill as Melanie often find themselves in this predicament. On the one hand, they worry that telling the whole truth about a medical situation could rob their patients of hope and lead to despair. But they also worry about the opposite strategy: that inaccurate provision of essential medical information, or overly rosy coverage of that information, could give patients false hopes, depriving them of the time and opportunity to emotionally prepare themselves and their families for what lies ahead.

When faced with such situations, doctors often give up and conclude that working with hope is not part of their job. But such a conclusion also does not stand up to scrutiny. Ignoring people's need for hope does not lead to its disappearance.

This dilemma arises from the too narrow view of the problem, which is widespread in the world of medicine, which equates "hope" with "cure". If we agree with this equation, it would mean that hope is simply not available to patients for whom there is no cure, unless, of course, they deny medical truth.

But this dilemma can be overcome if clinicians are willing to take into account new research in psychology and accept a broader understanding of hope that includes the recognition of bitter truths. And since unpleasant realities permeate our lives beyond health issues, this new understanding can have positives no matter what difficulties we face.

Hope is not wishful thinking, optimism, or "the power of positive thinking. " Of course, there is nothing wrong with being optimistic. Research shows that many positive effects are associated with optimism. However, this is not the same as hope. The Cambridge Dictionary defines optimism as "the feeling that good things are more likely to happen in the future than bad things." The influential psychologists Charles Carver and Michael Scheier, who have long studied optimism, describe optimism as the tendency to believe that the outcomes of life in general will be positive, favorable, or desirable. In other words, optimists simply believe that everything will turn out for the best, and the future will definitely be good. That's why it's often said that optimists wear rose-colored glasses or think the glass is half full—sometimes with cherry soda.

" Of course, there is nothing wrong with being optimistic. Research shows that many positive effects are associated with optimism. However, this is not the same as hope. The Cambridge Dictionary defines optimism as "the feeling that good things are more likely to happen in the future than bad things." The influential psychologists Charles Carver and Michael Scheier, who have long studied optimism, describe optimism as the tendency to believe that the outcomes of life in general will be positive, favorable, or desirable. In other words, optimists simply believe that everything will turn out for the best, and the future will definitely be good. That's why it's often said that optimists wear rose-colored glasses or think the glass is half full—sometimes with cherry soda.

However, hope is not the same as "the glass is half full." Hope appears even when the glass is only a third full or there is nothing in it at all. Because true hope is not living in a fantasy world, but living in this world. For example, she does not deny suffering and pain.

For example, she does not deny suffering and pain.

Super Survivors (2014), written by one of us, David B. Feldman, and co-authored by Lee Daniel Kravetz, tells the story of 16 survivors of trauma and tragedy who went on to make the world a better place. The red line in their stories was what is called "reasonable hope." While all of these survivors showed hope for the future, they were also aware of the reality of their situations. When James Cameron, sole survivor of the lynching of 1930 years old, founded the first chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Anderson, Indiana, worked on housing desegregation in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and eventually founded the American Museum of the Black Holocaust, he had no illusions that the world is a beautiful place where everything can be easily fixed. On the contrary, he understood what incredible resistance he would have to face, but he believed that his efforts would still help build a better life for black Americans. As he noted in his autobiography, The Time of Terror (1982): "With faith and prayer on my lips, I was determined to keep my hands on the gas and keep my eyes on the road."

As he noted in his autobiography, The Time of Terror (1982): "With faith and prayer on my lips, I was determined to keep my hands on the gas and keep my eyes on the road."

People who, like Cameron, fight for important goals do not do so because they see the world in rose-colored glasses. Likewise, scientists who courageously fight to end the COVID-19 pandemic, or cancer patients who enter treatment with painful side effects, know that the path will be difficult, but they are moving forward because they have found goals worth holding on to. "Hands on the gas" This is the source of their hope.

Hope, at its core, is perception. However, unlike most other perceptions, this perception has the ability to create reality. Most often, we think that our perception is created by reality. Look around you and pay attention to the objects around you. They all exist in reality before you perceive them. But hope is a special kind of perception: it is the perception of something that does not yet exist. It is the perception of what is possible.

It is the perception of what is possible.

And research shows that when people have hope, their goals are more likely to become a reality. In a study published in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology in 2009year, Feldman and his colleagues asked college students to name seven goals they would like to achieve over the next few months. The students then took a brief psychological test, known as the Goal Hope Scale, for each of these goals. After three months, they were asked to look back at a list of goals and evaluate how far they had progressed towards each of them. The results were simple: Those who were more hopeful of achieving their goal at the beginning of the study were more likely to report having achieved it by the end of the study.

It's not because hope has magical powers. Because when people believe that the goal they care about is achievable, they are more likely to take steps to achieve it.

This understanding of hope contrasts with the saying you may have heard: "Hope is not a strategy. " Of course, it's true that hope itself is not a strategy: while this feeling can cheer us up when we're down, it can't solve our problems.

" Of course, it's true that hope itself is not a strategy: while this feeling can cheer us up when we're down, it can't solve our problems.

But hope is more than a feeling. It is the way of thinking that pushes us to action. Actor Jane Fonda accurately expressed this point when she said, "Hope is activism."

Her statement is in good agreement with the most widely studied model of hope in psychology, known as the "Hope Theory". Although this model has been called a “theory,” it has been validated by hundreds of studies since it was first proposed by psychologist C. R. Snyder in 1989.

Snyder took a spontaneous approach. While at the University of Kansas, for a year he approached community leaders, including politicians, clergy, educators, and businessmen, and asked them to name the "most hopeful" people they know, using any definition of hope. He then interviewed as many people on their lists as he could. He discovered a surprisingly simple yet powerful feature of hope.

Namely, he realized that hopeful people have three things in common - goals, development paths, and agency (participation). Although Snyder named these three "components" of hope, it is more useful to think of them as the three conditions for the development of hope.

First, his interlocutors had a clear idea of their goals and felt committed to those goals. In other words, they had something they hoped for. Although the word "goal" is usually associated with formal goals, such as getting a promotion or graduating from school, Snyder observed that people's goals often spread across many areas of life, from career achievement to social or even spiritual aspirations. In fact, goals inspired by our deepest personal values tend to be more motivating and satisfying.

Second, Snyder's hopeful interlocutors had visions of paths—to put it simply, plans or strategies—that they believed would enable them to achieve their goals. In other words, they believed that they could do something to achieve their goals. According to hope theory, often people do nothing because they don't believe there is any way to achieve their goals, or if there is a way, it seems too long or difficult. But people who have hope tend to be able to break complex or difficult paths into many smaller steps that can be taken in turn. However, they have no illusions that all their methods will work. They understand that bad things can and do happen. Therefore, realizing that some of their plans may be blocked, they tend to try many different options.

According to hope theory, often people do nothing because they don't believe there is any way to achieve their goals, or if there is a way, it seems too long or difficult. But people who have hope tend to be able to break complex or difficult paths into many smaller steps that can be taken in turn. However, they have no illusions that all their methods will work. They understand that bad things can and do happen. Therefore, realizing that some of their plans may be blocked, they tend to try many different options.

Finally, those interviewed by Snyder had an unshakable belief in their abilities, which he called "the agency." Although they knew it would be difficult to work towards their goals, they still believed in their hearts that they could achieve them if they kept trying. As in Wattie Piper's popular children's book The Little Engine That Could (1930), beliefs such as "I think I can" fueled their hope and spurred them to action.

In other words, far from naive positive thinking, hope is a realistic yet far-sighted set of beliefs that drives our efforts to achieve a better future. As Barack Obama put it in the title of his book The Boldness of Hope (2006), hope is audacious. It offers a cold and hard view of reality, but nevertheless full of courage to believe that a better future is possible. Some may call it recklessness (synonymous with audacity), but many goals that people once considered impossible have turned out to be achievable. In the last century, humans have learned to fly, landed on the moon, networked the globe, and eradicated or greatly reduced once-widespread diseases such as polio and smallpox.

As Barack Obama put it in the title of his book The Boldness of Hope (2006), hope is audacious. It offers a cold and hard view of reality, but nevertheless full of courage to believe that a better future is possible. Some may call it recklessness (synonymous with audacity), but many goals that people once considered impossible have turned out to be achievable. In the last century, humans have learned to fly, landed on the moon, networked the globe, and eradicated or greatly reduced once-widespread diseases such as polio and smallpox.

Since the early 1990s, hundreds of studies have shown that this form of hope is strongly associated with psychological and physical well-being.

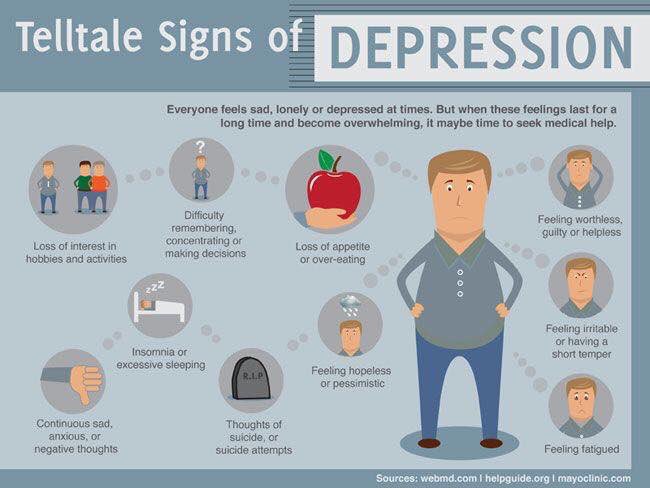

Scientists study the connection between hope and mental health relatively simply. Typically, studies involve measuring levels of well-being among large samples of people, as well as one of a small arsenal of psychological tests of hope, most commonly known as the Hope Scale. Perhaps unsurprisingly, such studies show that greater hope is associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety. In many ways, hope is the opposite of such feelings. While depression often makes people believe that there is nothing they can do to improve their lives, when people are hopeful, they tend to believe otherwise. If anxiety could speak, it could say something like this: "Bad things are coming, and there is no way to stop them." Hope, on the other hand, could answer, "Even if something bad happens, you can handle it and perhaps achieve your most important goals."

In many ways, hope is the opposite of such feelings. While depression often makes people believe that there is nothing they can do to improve their lives, when people are hopeful, they tend to believe otherwise. If anxiety could speak, it could say something like this: "Bad things are coming, and there is no way to stop them." Hope, on the other hand, could answer, "Even if something bad happens, you can handle it and perhaps achieve your most important goals."

A growing body of research links hope to improved physical health. High-hopeful people are more likely than their low-hope counterparts to not smoke, exercise regularly, and eat healthier foods. After a serious injury, they are more likely to devote themselves fully to rehabilitation and subsequently regain greater performance.

Hope is also associated with better adaptation to illness in people with serious illnesses, including those paralyzed by spinal cord injury and adolescents with severe burns. In one simple but illustrative study of the connection between hope and pain, scientists asked people to fill out a hope scale and then go through a so-called "cold press": immerse their non-dominant hand (usually the left) in a bath of ice water and keep it there for as long as possible. High hopeful people kept their hands submerged for almost 30 seconds longer than their low hopeful counterparts, averaging about 2 minutes. This is a very long time, given that after 3-4 minutes the hand usually becomes numb and tissue damage can occur.

High hopeful people kept their hands submerged for almost 30 seconds longer than their low hopeful counterparts, averaging about 2 minutes. This is a very long time, given that after 3-4 minutes the hand usually becomes numb and tissue damage can occur.

This greater tolerance for pain may be, at least in part, the result of a lower level of pain catastrophizing—a tendency to think about pain sensations. It's not that people with a high degree of hope don't notice pain. They notice her. It's just that they can focus more on the goals they are trying to achieve. Given that what we focus on increases our perception (and what we don't focus on becomes weaker), this can lead to a decrease in the level of perceived pain. This is a kind of psychological equivalent of looking away when we are given an injection in the arm.

In addition to these findings, there is new evidence that hope affects the life expectancy of people with cancer. Together with our colleagues Marie Bakitas, Jay Hull, and Mark O'Rourke, we recently reanalyzed a database of more than 500 patients with advanced cancer who received palliative care. We divided the sample into two large groups - patients with a high level of hope and patients with a low level of hope - and examined whether patients who have a higher level live longer. It is important to note that in this study we were unable to use the conventional hope scale (mentioned earlier) as we were limited to reanalyzing the data already collected. Instead, we determined who was high and who was low in hope based on their responses to three simple questions that asked them to rate how much they agreed with statements like "I feel hopeful." To our surprise, those who rated their level of hope higher tended to live longer than those who rated it lower.

We divided the sample into two large groups - patients with a high level of hope and patients with a low level of hope - and examined whether patients who have a higher level live longer. It is important to note that in this study we were unable to use the conventional hope scale (mentioned earlier) as we were limited to reanalyzing the data already collected. Instead, we determined who was high and who was low in hope based on their responses to three simple questions that asked them to rate how much they agreed with statements like "I feel hopeful." To our surprise, those who rated their level of hope higher tended to live longer than those who rated it lower.

It is worth bearing in mind that the people in this study were very ill. All of them had the last stage of cancer, which, according to doctors, could take their lives within a year or two. Presumably, most of them knew that there was no cure. Yet hope determined a longer life, even in this state. So what was their hope?

This question may seem meaningless if we assume that "hope" and "cure" mean the same thing. But Snyder's definition of hope shows why this is not necessarily the case. Hope can always exist when people have a goal that excites them, when they believe that there are paths that can lead to this goal, and when they feel capable of self-realization.

But Snyder's definition of hope shows why this is not necessarily the case. Hope can always exist when people have a goal that excites them, when they believe that there are paths that can lead to this goal, and when they feel capable of self-realization.

Of course, hope can be aimed at a cure, given the latest advances in cancer treatment. Moreover, people, of course, sometimes live longer than doctors expect. But when a cure is not possible despite the best efforts of doctors, patients, and families, that does not mean that hope is also impossible.

See also

- Depressive Mind: How to Deal with Negative Thinking

- "Yes, but suddenly? ..": how to cope with generalized anxiety

A few years ago, Feldman and his assistants visited the homes of dozens of people with terminal cancer who chose hospice care. Because getting hospice care usually means stopping treatment, they were interested to see if these patients were still hopeful. They conducted a survey on the hope scale and found that the level of hope in these patients was as high as in people who continue to receive treatment, although only a third of them said that they set a goal to be cured. What did they hope for? They talked about all sorts of wonderful hopes, including "resuming my hobby of digital photography", "flying in a helicopter", "writing a book about my life", "spending time with my grandchildren", "giving the world what I have" and "enjoying the rest of the days." For these patients, hope shone even in a situation that other people might consider hopeless.

They conducted a survey on the hope scale and found that the level of hope in these patients was as high as in people who continue to receive treatment, although only a third of them said that they set a goal to be cured. What did they hope for? They talked about all sorts of wonderful hopes, including "resuming my hobby of digital photography", "flying in a helicopter", "writing a book about my life", "spending time with my grandchildren", "giving the world what I have" and "enjoying the rest of the days." For these patients, hope shone even in a situation that other people might consider hopeless.

One of the patients, let's call him "Ned", perhaps best illustrates hope in this context. A man with a great sense of humor, he collected jokes all his life. In fact, Ned knew more than 1,000 of them. "And that's not counting the vulgar ones," he often said with a smirk. At the age of 84, when the heart failure with which he had lived for several years began to progress more rapidly and Ned could no longer take care of himself at home, he entered an inpatient hospice. Late one evening, one of the employees found him quietly crying in his room. When she cautiously asked Ned what he was thinking, he replied, “All my jokes will die with me. My grandchildren will never hear them.”

Late one evening, one of the employees found him quietly crying in his room. When she cautiously asked Ned what he was thinking, he replied, “All my jokes will die with me. My grandchildren will never hear them.”

In response, she suggested that Ned start writing them down and gave him a notebook and a pen. With joy and enthusiasm, he filled every page with jokes. However, by the time he was given the second notebook, he was too weak to write. So the hospice staff took turns sitting at his bedside and taking dictation. Then, about a week later, Ned made an unusual request. “I want to do a comedy act,” he said. The care team enthusiastically agreed. Over the next few days, his spirits lifted considerably as he prepared. Then, 72 hours later, the big moment came. Almost the entire staff gathered with other patients to listen to Ned speak. From his bed, which was rolled out on wheels into the corridor, he performed a stunning number. His audience was confused and his face beamed with joy. At that moment and in the days that followed, he had all the conditions to strengthen hope: a goal that was really meaningful to him, a way to achieve it, and the ability to bring it to life. Although Ned died just a week later, he knew he had given his listeners—and himself—the most meaningful gift imaginable.

At that moment and in the days that followed, he had all the conditions to strengthen hope: a goal that was really meaningful to him, a way to achieve it, and the ability to bring it to life. Although Ned died just a week later, he knew he had given his listeners—and himself—the most meaningful gift imaginable.

Most of us have a hard time imagining what it's like for Ned and other patients with terminal illnesses. But the fact that they can be hopeful shows us that the double bind we talked about at the beginning of this article is false. Knowing the truth, even if it is bleak, does not exclude the possibility of experiencing hope. Hope is possible even in difficult circumstances.

This understanding is perhaps more important now than ever before. Undoubtedly, the last two years have been one of the most traumatic for many people in recent times. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization announced COVID-19pandemic. Since then, millions of people have fallen victim to this terrible disease. Against this backdrop, our world is also suffering from ongoing racial injustice, political unrest, natural disasters, and many other disasters. Few use the word "hope" to describe the times we live in. Instead, words like "tragic" and "heartbreaking" come to mind. People are scared, sad, angry and heartbroken.

Against this backdrop, our world is also suffering from ongoing racial injustice, political unrest, natural disasters, and many other disasters. Few use the word "hope" to describe the times we live in. Instead, words like "tragic" and "heartbreaking" come to mind. People are scared, sad, angry and heartbroken.

It is clear that hope will not magically end racism, eradicate COVID-19, will not cure cancer and will not lead to instant achievement of any other important goals. But active hope is often the psychological driver that drives people to make efforts to achieve these goals. As essayist and activist Rebecca Solnit wrote in The Guardian in 2016:

“Your adversaries would like you to believe that everything is hopeless, that you have no strength, that there is no reason to act, that you cannot win. Hope is a gift that shouldn't be given up, it's a power that shouldn't be thrown away."

No matter who or what your opponents are in life, hope is not something you should give up, ever.

Whenever you feel hopeless, ask yourself what you can do to create the conditions for hope in your life and in the world around you. What goals matter to you? What steps – even small ones – can you move towards these goals? And what inspires you to take action, to keep moving forward, even when everything is unimaginably difficult?

When Melanie entered Dr. Tamika's office, she didn't recognize her own walk. Her hesitant steps were not like her usual confident steps. Dr. Tamika is one of those doctors who came into medicine not just to communicate with patients, but to communicate with them spiritually, so she caught Melanie's fear. But even in fear there might be room for hope, she thought.

“I know you're afraid, and I don't blame you for it,” Dr. Tamika said. What you are facing is one of the most severe cancers I know of. But we will try our best to beat cancer. And perhaps we will succeed. But whatever happens, I won't leave you alone with it.

What do you want from your life now?"

Dr. Tamika's words were not only reassuring, they were exactly what Melanie needed to hear.

“You have no idea how important it is for me to hear this from you,” she told Dr. Tamika. I want to do my best to beat cancer, but I also want to make sure that the pain is controlled and that whatever treatment we choose will leave me with the option to check off my wish list, just in case.”

At that moment, Melanie had hope. It was not a hope based on a rose-colored vision of the world or the assumption that everything would magically turn out well. She knew a cure would be unlikely. But her hope was based on something more solid than just positive thinking: there are goals worth striving for and someone who will come to the rescue. In the midst of life's uncertainties, sometimes that's the best we can ask for.

Read also Between Fear and Expectation: How Hope Protects the Brain

The article was first published in English in Aeon magazine under the title "Hope is not optimism" on January 20, 2022.

/nginx/o/2019/08/15/12467881t1he799.jpg)