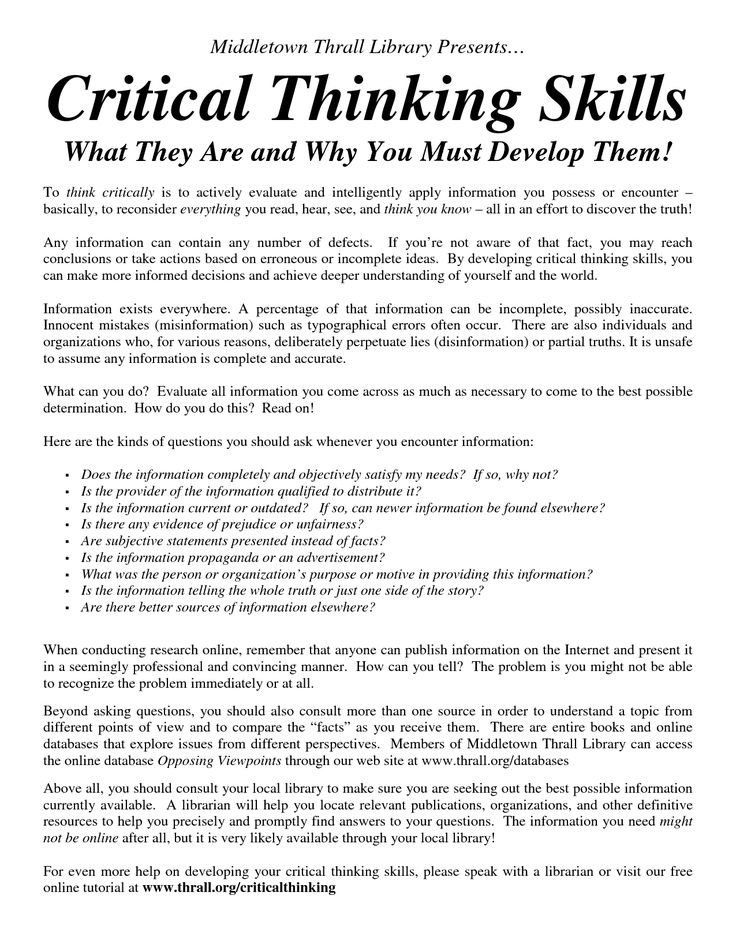

Feeling good cognitive distortions definitions

The website of David D. Burns, MD | Secrets of Self-Esteem #2

Negative Vs.Positive Distortions

*By David D. Burns, M.D.

* Copyright © 2010 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2014. Do not reproduce without permission. Do not quote or reproduce without express written permission.

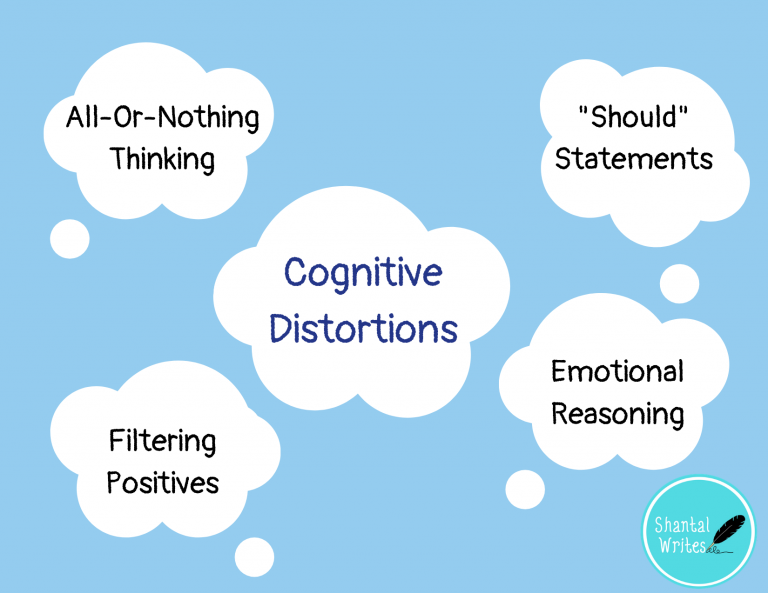

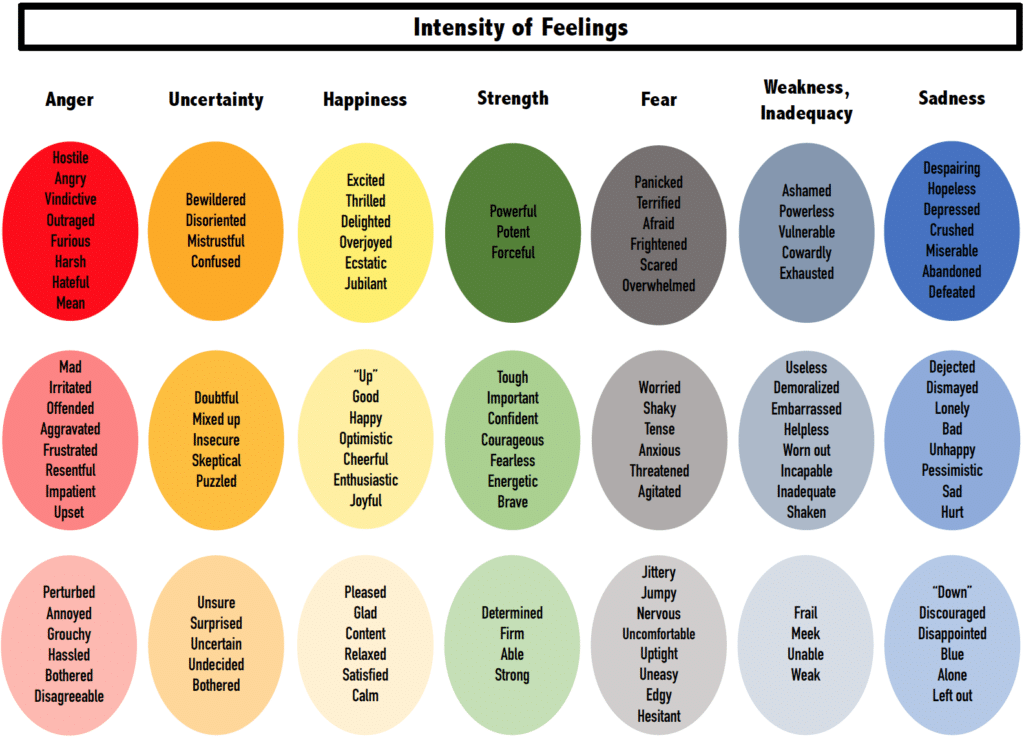

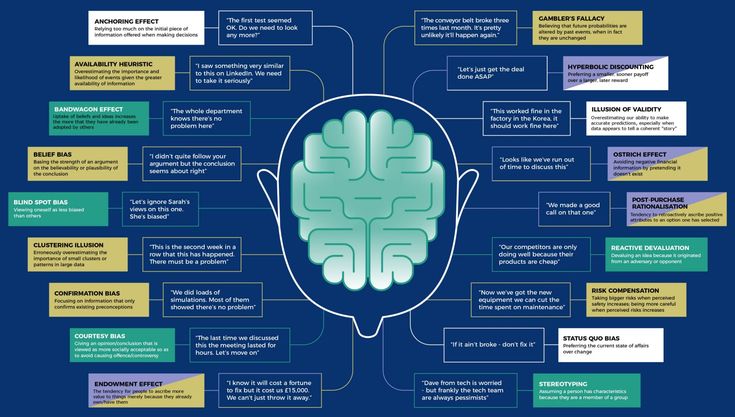

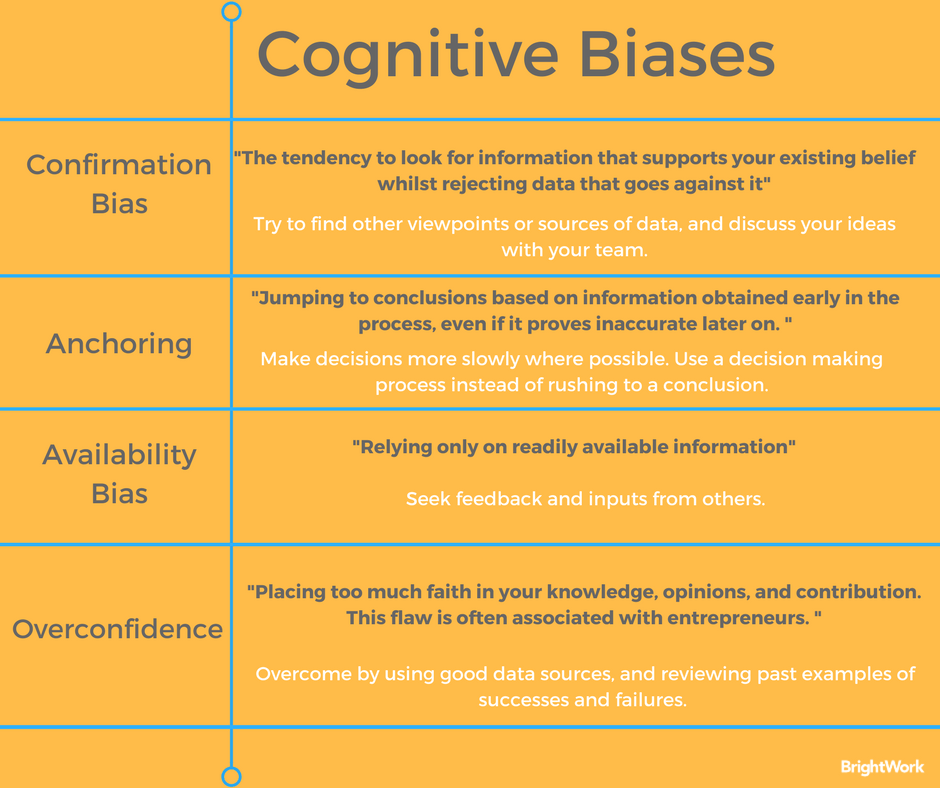

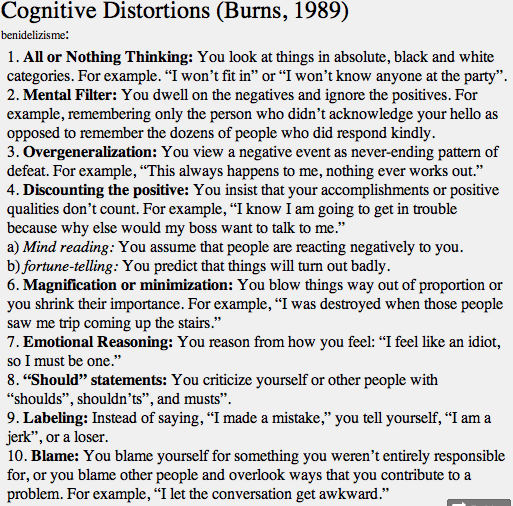

In my book, Feeling Good, I listed ten cognitive distortions, or thinking errors, such as All-or-Nothing Thinking, Jumping to Conclusions, Should Statements, Emotional Reasoning, and Self-Blame. These negative distortions trigger negative feelings such as:

- Depression

- Feelings of worthlessness, inferiority, and low self-esteem

- Hopelessness

- Anxiety, shyness, and panic

- Shame and guilty

- Anger and frustration

The list of negative distortions has been reproduced in hundreds of magazines and books and has been helpful to many individuals suffering from mood problems. The idea is that when you’re feeling upset, you’re often involved in a mental con, but you don’t realize it. You’re telling yourself things about yourself and the world that aren’t really true. And when you change the way you think you can change the way you feel.

Most people are not aware that positive distortions can also play an important role in emotional and relationship problems, as well as habits and addictions. There are ten positive distortions that are the exact mirror images of the ten negative distortions. For example, Positive All-or-Nothing Thinking is the opposite of Negative All-or-Nothing Thinking. In both instances, you look at things in opposite, black-or-white categories, and shades of gray do not exist. In the negative version, you might think of yourself as a “loser” because your marriage broke up, or because you failed to achieve an important personal or professional goal. In the positive version, you might think of yourself as a “winner” because of some positive event or personal success.

Positive distortions can be as destructive as negative distortions. When left unchecked, they can trigger mania (abnormal mood elevations), habits and addictions such as gambling and alcohol and drug abuse, and relationship problems, as well as feelings of rage, violence, and even war. For example, Hitler’s messages to the German people involved a skillful blend of positive and negative distortions. He tried to sell the German people on the idea that they were a superior race with the right or duty to exterminate Jews, mental patients, gypsies and others who were labeled as “bad” or “inferior.” Unlike the negative distortions, the positive distortions typically lead to intoxicating mood elevations so you may not be motivated to challenge them or to change the way you’re thinking.

Here are brief definitions, along with some examples, of the ten positive and negative distortions.

Checklist of Negative and Positive Distortions*

| Distortion |

Negative Distortion Example | Positive Distortion Example |

1. All-or-Nothing Thinking. You think about yourself or the world in black-or-white, all-or-nothing categories. Shades of gray do not exist. All-or-Nothing Thinking. You think about yourself or the world in black-or-white, all-or-nothing categories. Shades of gray do not exist. | When you fail, you may tell yourself that you’re a complete failure. | When you succeed, you may tell yourself that you’re a winner and feel superior. |

| 2. Overgeneralization. You think about a negative event as a never-ending pattern of defeat or a positive event as a never-ending pattern of success. | When you’re rejected by someone you care about, you may tell yourself that you’re an unlovable loser who will be alone and miserable forever. | When you overcome an episode of depression or self-doubt, and you’re suddenly feeling happy again, you may tell yourself that all your problems are solved and that you’ll always feel happy. |

3. Mental Filter. You think exclusively about your shortcomings and ignore your positive qualities and accomplishments. Or, you dwell on the positives and overlook the negatives. Or, you dwell on the positives and overlook the negatives. | A TV talk show host told me that he typically received hundreds of enthusiastic emails from fans every day, but there was nearly always one critical email from a disgruntled viewer. He explained that he’d obsess for hours about the negative email and completely overlook the hundreds of glowing ones. As a result, he constantly struggled with feelings of anxiety and low self-esteem in spite of his tremendous ratings and popularity. | You may fantasize about how good that desert will taste, and ignore the negatives, like gaining weight and feeling guilty or bloated afterwards. Or, you may tell yourself how great you’ll feel if you have a drink, and ignore the fact you nearly always drink too much and end up with a hangover. |

4. Discounting the Facts. You tell yourself that negative or positive facts don’t count, so as to maintain a universally negative or positive self-image.

| Discounting the Positive: When someone genuinely compliments you, you may tell yourself they’re only saying that to make you feel good. | Discounting the Negative: When you’re trying to diet and feeling tempted by something tasty, you may tell yourself, “I’ll only have one little bite.” But you’ve probably given yourself this message on hundreds of occasions, and it has never once been accurate!During an argument, you may get defensive and insist that the other person is “wrong.” Then the conflict escalates. |

| 5. Jumping to Conclusions. You jump to conclusions that aren’t warranted by the facts. There are two common forms that are called Mind-Reading and Fortune-Telling. | ||

| Mind-Reading, you make assumptions about how other people are thinking and feeling. | If you’re feeling shy at a party, you may tell yourself that other people don’t have to struggle with shyness or that they’d look down on you if they knew you were shy. | You tell yourself that a relationship is going really. well when the other person is actually feeling annoyed or unhappy with you. |

| Fortune-Telling, you make dogmatic negative or positive predictions about the future. | When you’re depressed, you may tell yourself that you’ll never recover. When you’re feeling anxious, you may tell yourself that something terrible is about to happen—“When I give my talk, my mind will go blank. I’ll look like an idiot.” | You tell yourself, “I’ll just have one drink” or “one bite,” when, in fact, you never stop at just one drink or bite. |

6. Magnification and Minimization. You blow things out of proportion or shrink their importance inappropriately. This is also called the “binocular trick” because it’s like looking through the ends of a pair of binoculars, so things either look much bigger, or much smaller, than they are in reality. | When you’re procrastinating, you may think about everything that you’ve been putting off and tell yourself how overwhelming all those tasks will be. (Magnification) You may also tell yourself that you’re efforts today wouldn’t amount to anything anyway, so you might as well put it off. (Minimization) | When you’re trying to diet and you’re feeling tempted, you may tell yourself: “This ice cream will taste so good!” (Magnification). Will it really be that good? Will it be worth the way you’ll feel about yourself after you give in to the urge to binge? |

| 7. Emotional Reasoning. You reason from how you feel. In point of fact, your feelings result from your thoughts, and not from what’s actually happening. If your thoughts are distorted, your feelings will be as misleading as the grotesque images you see in curved fun-house mirrors. | When you procrastinate, you may tell yourself, “I’ll clean my desk (or start my diet) when I’m more in the mood. I just don’t feel like it right now.” Of course, the feeling never comes! When you’re depressed, you may tell yourself, “I feel like a loser, so I must really be one.” Or “I feel hopeless, so I must be hopeless.” I just don’t feel like it right now.” Of course, the feeling never comes! When you’re depressed, you may tell yourself, “I feel like a loser, so I must really be one.” Or “I feel hopeless, so I must be hopeless.” | When you’re gambling, you may say, “I feel lucky! I just know I’m about to hit the jackpot.”This distortion also triggers romantic intoxication. When you meet someone attractive, you may feel so happy and excited that you think that he or she must be wonderful—the man (or woman) of your dreams. |

| 8. Should Statements. You make yourself (or others) miserable with “shoulds,” “musts” or”ought to’s.” Hidden Shoulds are sometimes implied by negative thoughts. | ||

| Self-Directed Shoulds cause feelings of guilt, shame, depression, and worthlessness. | You tell yourself that you shouldn’t have screwed up and made such a stupid mistake. | When you’re feeling tempted, you may tell yourself, “I’ve had a hard day. I deserve a drink (or a nice dish of ice cream).” |

| Other-Directed Shoulds trigger feelings of anger and relationship problems. | You may tell yourself, “That fellow shouldn’t cut in front of me in traffic like that. I’ll show him that he can’t get away with it!” | You may tell yourself that your values are the best values and that other people should think and feel the same way. |

| World-Directed Shoulds cause feelings of frustration and entitlement. | “The train shouldn’t be late when I’m in such a hurry!” | You may tell yourself that the world should be the way you expect it to be. |

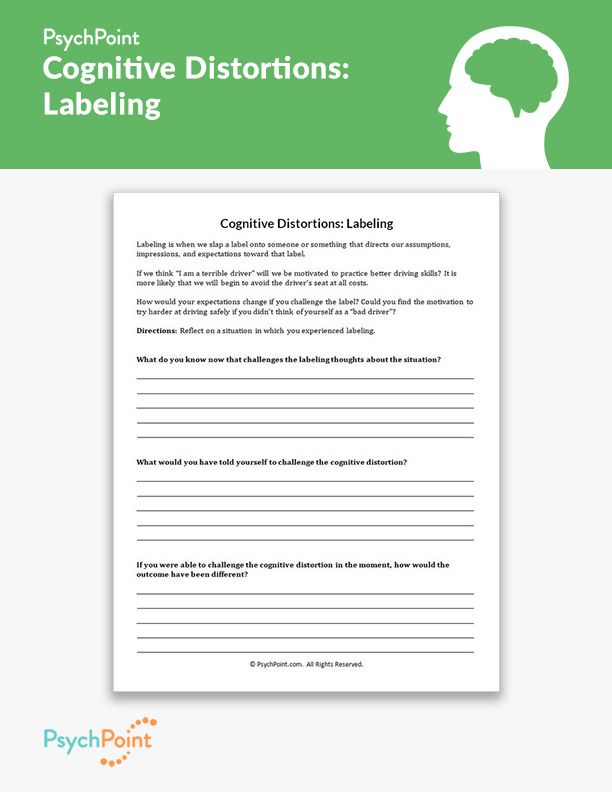

9. Labeling. You label yourself or others instead. Labeling is actually an extreme form of overgeneralization, because you see your entire self or essence as defective and globally bad, or superior. | You may label yourself or someone you’re not getting along with as “a loser” or “a jerk.” A physician slipped up on her diet and gave in to the temptation to eat a donut Then she told herself that she was “a fat pig with no will power.” This thought was so upsetting that she ate six more donuts. | When you do well, you may think of yourself as special or as “a winner.” Motivational speakers, politicians, and athletic coaches often use this strategy to motivate people. But in reality, there’s no such thing as a “winner” or a “loser.” We’re all human beings, and no one can win or lose all the time. |

| 10. Blame. You find fault with yourself (Self-Blame) or others (Other Blame). | Self-blame. If you’re depressed, you may beat up on yourself constantly and mercilessly, blaming yourself for every error and shortcoming instead of using your energy to find creative solutions to your problems. | Other-blame. During an argument, you may tell yourself that the other person is to blame for the conflict. Then you feel like an innocent victim and overlook your own role in the problem. |

Although it is a matter of controversy, I believe that it is possible to feel joyous and enlightened without positive distortions. I’m also convinced that healthy negative emotions (such as sadness or healthy fear) can be distinguished from unhealthy negative emotions (such as clinical depression or a panic attack) by the presence or absence of negative distortions in the thoughts that trigger the feelings.

In the third chapter of Feeling Good I described an experience during my medical school when I was on call for the inpatient surgical service one evening at the Stanford Hospital. One of our patients was an elderly man with a kidney tumor. We operated and successfully removed his kidney, and the prognosis seemed positive. Unfortunately, he suddenly developed an aggressive metastasis to his liver and was placed on the critical list. The metastasis was not treatable.

The metastasis was not treatable.

His elderly wife stayed by his bed night and day, and wouldn’t leave the hospital. At times, she would just let her head slump next to him on the bed and fall asleep. She often stroked his head and said, “You’re still my man and I have always loved you.”

One night he began to slip into a coma, so the family was notified. Nearly a dozen of them soon arrived in his room, including his children and grandchildren. One of his sons asked if I could remove the catheter from his penis, because it had been uncomfortable for him. I was pretty unsure of myself, and didn’t even know how to remove a catheter, so I checked at the nursing station, but they said it was okay and explained how to do it. I asked if this meant that he was dying, and they said he was.

I went back to the room, pulled the curtain around the bed, and removed the catheter from his penis. Then I opened the curtain again. His son looked at me and asked, “Does that mean he’s going to die tonight?”

I had grown attached to him because he was a very kind man who had reminded me of my grandfather. Tears were rolling down my cheeks as I said, “He’s slipping into a coma, but he can still hear you, so it’s time to say goodbye. I loved him, too.” They all gathered around his bed to comfort him. I went to the room where the residents did their charting work and began to sob. He died within an hour.

Tears were rolling down my cheeks as I said, “He’s slipping into a coma, but he can still hear you, so it’s time to say goodbye. I loved him, too.” They all gathered around his bed to comfort him. I went to the room where the residents did their charting work and began to sob. He died within an hour.

To my way of thinking, the experience of profound sadness and loss, without distortions, is not depression, but rather a celebration of life. Sadness reflects our capacity for love. Healthy negative and positive emotions don’t need treatment, but are part of the richness of the human experience.

Sometimes healthy negative emotions (such as grief) are complicated by negative distortions, so healthy and unhealthy feelings coexist. In this case, you can use the “Mood Journal” to pinpoint and challenge your distorted negative thoughts. In Feeling Good I also described a severely depressed, suicidal physician whose brother had committed suicide. She was telling herself: 1. His depression was my fault because our parents loved me more when we were growing up. 2. I should have known he was suicidal the night he killed himself. 3. Because I failed him, I too, deserve to die.

2. I should have known he was suicidal the night he killed himself. 3. Because I failed him, I too, deserve to die.

These thoughts contained many distortions, such as Self-Blame, Should Statements, and Emotional Reasoning, as well as Mind-Reading and Fortune-Telling, since she expected herself to know how he was thinking and feeling the night he took his life. Fortunately, we were able to find a way to challenge and defeat those thoughts during her seventh therapy session. Her depression and suicidal urges vanished, and she was finally able to grieve his loss. Paradoxically, the intense depression, shame, and guilt she was feeling had prevented her from grieving his loss in a healthy way.

Take Our Poll

22 Examples & Worksheets (& PDF)

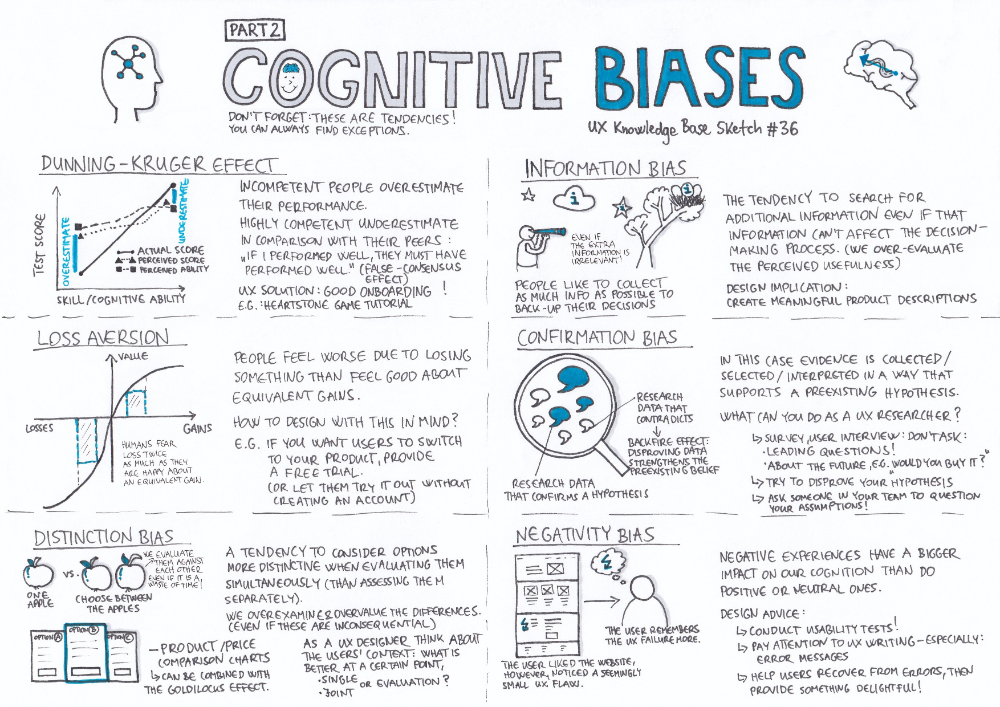

We tend to trust what goes on in our brains. After all, if you can’t trust your own brain, what can you trust?

Generally, this is a good thing—our brain has been wired to alert us to danger, attract us to potential mates, and find solutions to the problems we encounter every day.

However, there are some occasions when you may want to second guess what your brain is telling you. It’s not that your brain is purposely lying to you, it’s just that it may have developed some faulty or non-helpful connections over time.

It can be surprisingly easy to create faulty connections in the brain. Our brains are predisposed to making connections between thoughts, ideas, actions, and consequences, whether they are truly connected or not.

This tendency to make connections where there is no true relationship is the basis of a common problem when it comes to interpreting research: the assumption that because two variables are correlated, one causes or leads to the other. The refrain “correlation does not equal causation!” is a familiar one to any student of psychology or the social sciences.

It is all too easy to view a coincidence or a complicated relationship and make false or overly simplistic assumptions in research—just as it is easy to connect two events or thoughts that occur around the same time when there are no real ties between them.

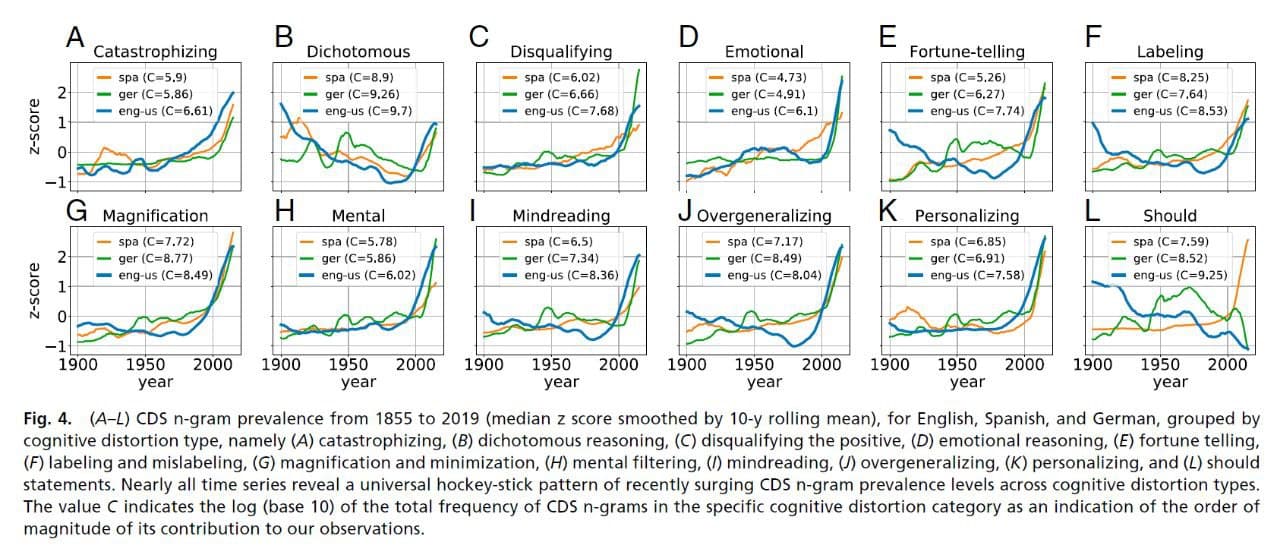

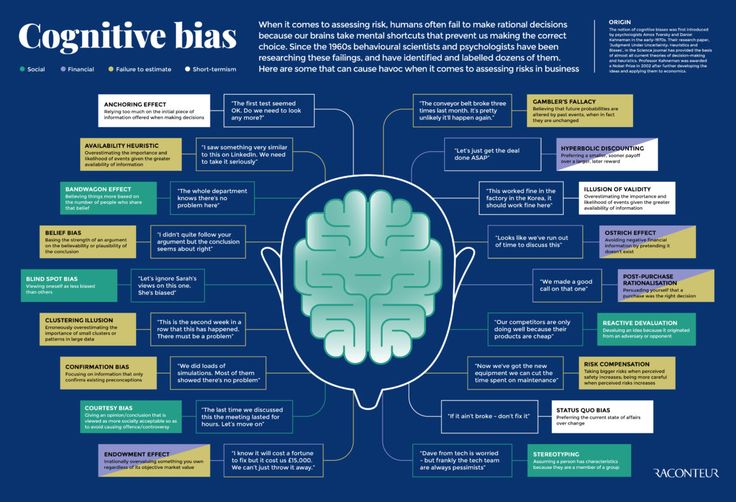

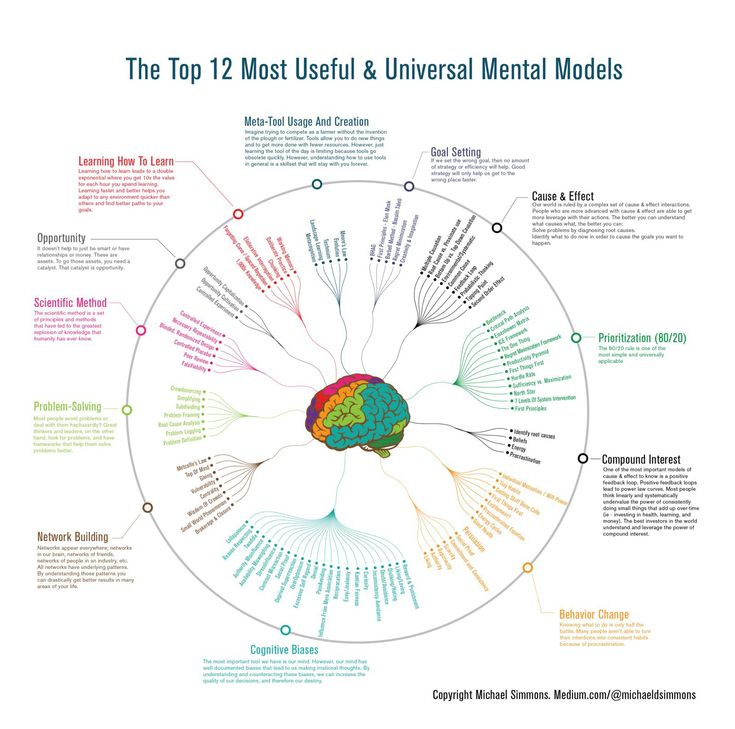

There are many terms for this kind of mistake in social science research, complete with academic jargon and overly complicated phrasing. In the context of our thoughts and beliefs, these mistakes are referred to as “cognitive distortions.”

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will provide you with a detailed insight into Positive CBT and will give you additional tools to address cognitive distortions in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains:

- What are Cognitive Distortions?

- Experts in Cognitive Distortions: Aaron Beck and David Burns

- A List of the Most Common Cognitive Distortions

- Changing Your Thinking: Examples of Techniques to Combat Cognitive Distortions

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What are Cognitive Distortions?

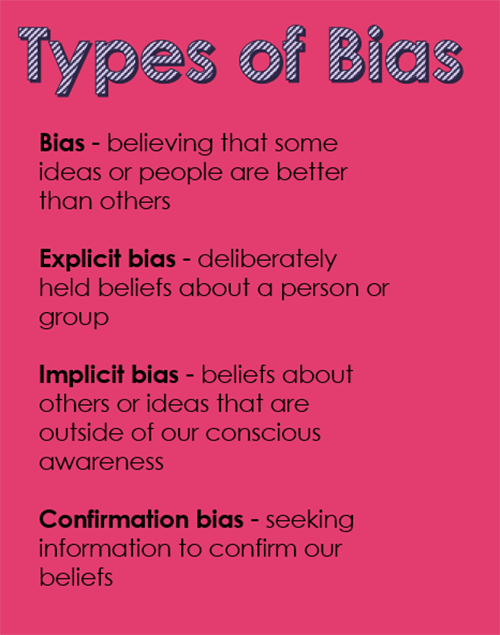

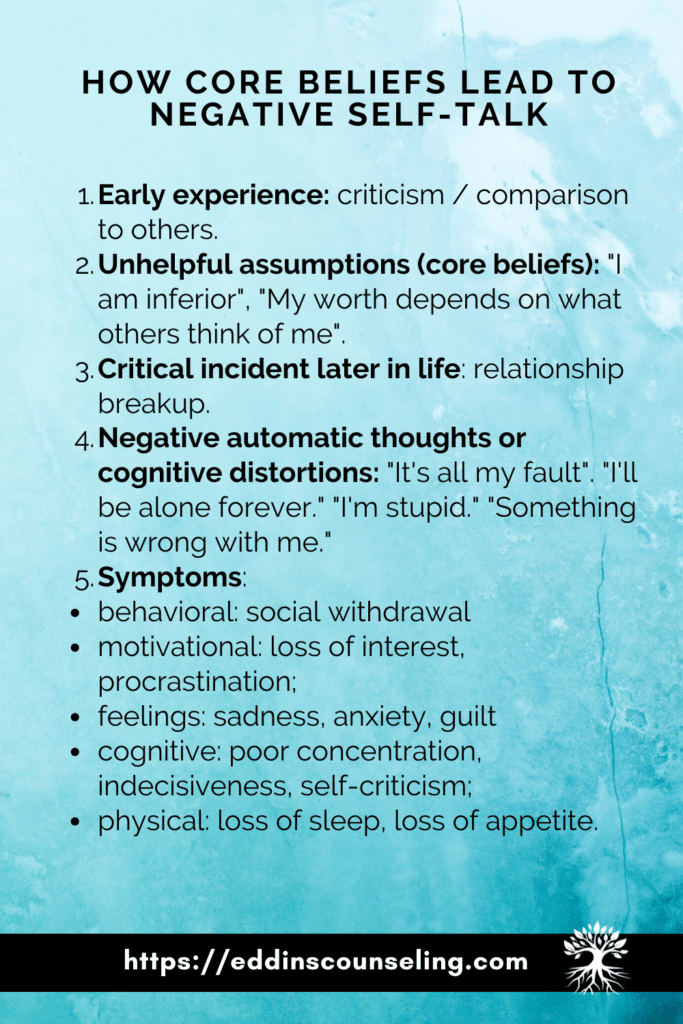

Cognitive distortions are biased perspectives we take on ourselves and the world around us. They are irrational thoughts and beliefs that we unknowingly reinforce over time.

They are irrational thoughts and beliefs that we unknowingly reinforce over time.

These patterns and systems of thought are often subtle–it’s difficult to recognize them when they are a regular feature of your day-to-day thoughts. That is why they can be so damaging since it’s hard to change what you don’t recognize as something that needs to change!

Cognitive distortions come in many forms (which we’ll cover later in this piece), but they all have some things in common.

All cognitive distortions are:

- Tendencies or patterns of thinking or believing;

- That are false or inaccurate;

- And have the potential to cause psychological damage.

It can be scary to admit that you may fall prey to distorted thinking. You might be thinking, “There’s no way I am holding on to any blatantly false beliefs!” While most people don’t suffer in their daily lives from these kinds of cognitive distortions, it seems that no one can completely escape these distortions.

If you’re human, you have likely fallen for a few of the numerous cognitive distortions at one time or another. The difference between those who occasionally stumble into a cognitive distortion and those who struggle with them on a more long-term basis is the ability to identify and modify or correct these faulty patterns of thinking.

As with many skills and abilities in life, some are far better at this than others–but with practice, you can improve your ability to recognize and respond to these distortions.

These distortions have been shown to relate positively to symptoms of depression, meaning that where cognitive distortions abound, symptoms of depression are likely to occur as well (Burns, Shaw, & Croker, 1987).

In the words of the renowned psychiatrist and researcher David Burns:

“I suspect you will find that a great many of your negative feelings are in fact based on such thinking errors.”

Errors in thinking, or cognitive distortions, are particularly effective at provoking or exacerbating symptoms of depression. It is still a bit ambiguous as to whether these distortions cause depression or depression brings out these distortions (after all, correlation does not equal causation!) but it is clear that they frequently go hand-in-hand.

It is still a bit ambiguous as to whether these distortions cause depression or depression brings out these distortions (after all, correlation does not equal causation!) but it is clear that they frequently go hand-in-hand.

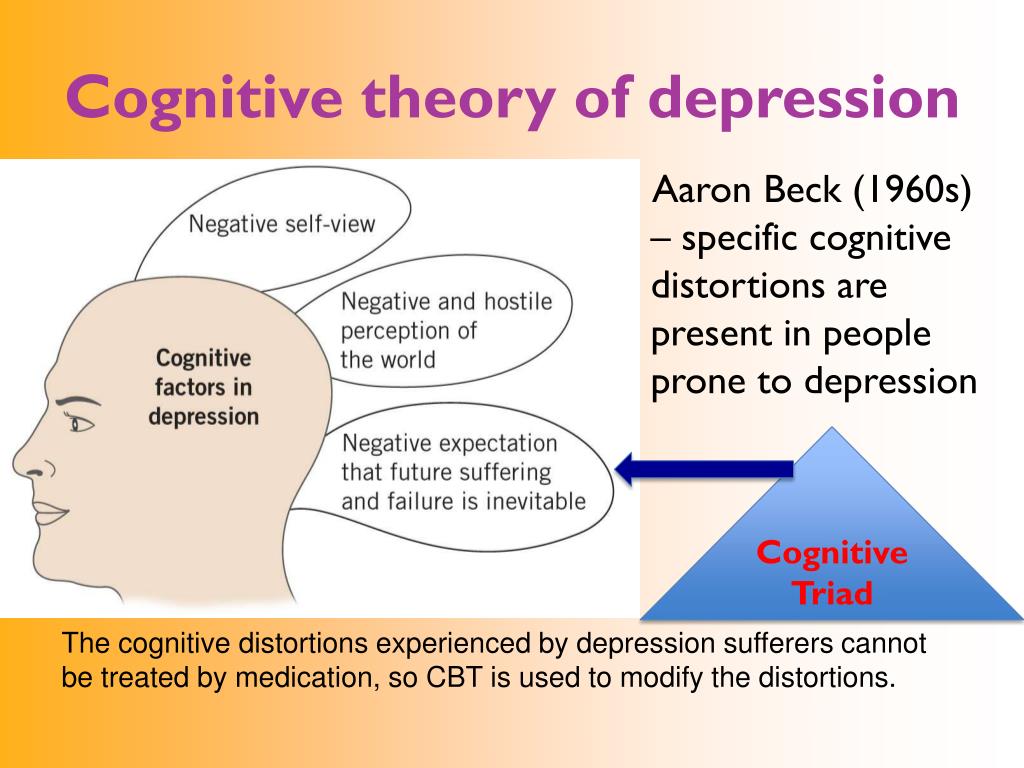

Much of the knowledge around cognitive distortions come from research by two experts: Aaron Beck and David Burns. Both are prominent in the fields of psychiatry and psychotherapy.

Experts in Cognitive Distortions: Aaron Beck and David Burns

If you dig any deeper into cognitive distortions and their role in depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues, you will find two names over and over again: Aaron Beck and David Burns.

These two psychologists literally wrote the book(s) on depression, cognitive distortions, and the treatment of these problems.

Aaron Beck

Aaron Beck. Image Retrieved by URL.Aaron Beck began his career at Yale Medical School, where he graduated in 1946 (GoodTherapy, 2015). His required rotations in psychiatry during his residency ignited his passion for research on depression, suicide, and effective treatment.

In 1954, he joined the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Psychiatry, where he still holds the position of Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry.

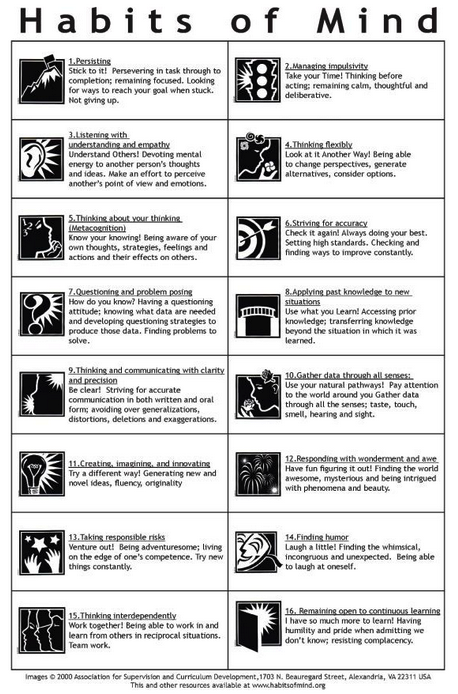

In addition to his prodigious catalog of publications, Beck founded the Beck Initiative to teach therapists how to conduct cognitive therapy with their patients–an endeavor that has helped cognitive therapy grow into the therapy juggernaut that it is today.

Beck also applied his knowledge as a member or consultant for the National Institute of Mental Health, an editor for several peer-reviewed journals, and lectures and visiting professorships at various academic institutions throughout the world (GoodTherapy, 2015).

While there are clearly many honors, awards, and achievements Beck may be known for, perhaps his greatest contribution to the field of psychology is his role in the development of cognitive therapy.

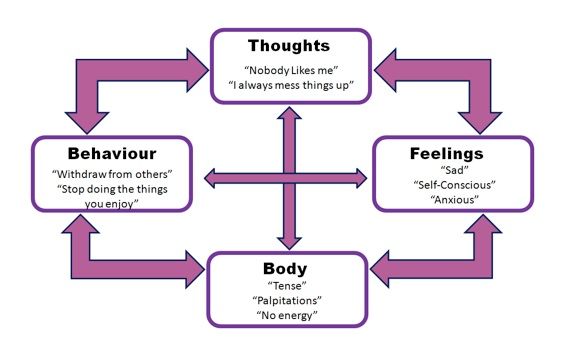

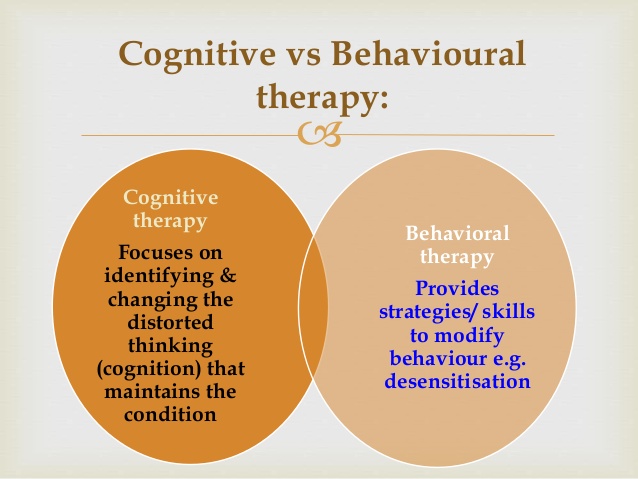

Beck developed the basis for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, or CBT, when he noticed that many of his patients struggling with depression were operating on false assumptions and distorted thinking (GoodTherapy, 2015). He connected these distorted thinking patterns with his patients’ symptoms and hypothesized that changing their thinking could change their symptoms.

He connected these distorted thinking patterns with his patients’ symptoms and hypothesized that changing their thinking could change their symptoms.

This is the foundation of CBT – the idea that our thought patterns and deeply held beliefs about ourselves and the world around us drive our experiences. This can lead to mental health disorders when they are distorted but can be modified or changed to eliminate troublesome symptoms.

In line with his general research focus, Beck also developed two important scales that are among some of the most used scales in psychology: the Beck Depression Inventory and the Beck Hopelessness Scale. These scales are used to evaluate symptoms of depression and risk of suicide and are still applied decades after their original development (GoodTherapy, 2015).

David Burns

Another big name in depression and treatment research, Dr. David Burns, also spent some time learning and developing his skills at the University of Pennsylvania – it seems that UPenn is particularly good at producing future leaders in psychology!

Burns graduated from Stanford University School of Medicine and moved on to the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, where he completed his psychiatry residency and cemented his interest in the treatment of mental health disorders (Feeling Good, n. d.).

d.).

He is currently serving as a Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Stanford University School of Medicine, in addition to continuing his research on treating depression and training therapists to conduct effective psychotherapy sessions (Feeling Good, n.d.). Much of his work is based on Beck’s research revealing the potential impacts of distorted thinking and suggesting ways to correct this thinking.

He is perhaps most well known outside of strictly academic circles for his worldwide best-selling book Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. This book has sold more than 4 million copies within the United States alone and is often recommended by therapists to their patients struggling with depression (Summit for Clinical Excellence, n.d.).

This book outlines Burns’ approach to treating depression, which mostly focuses on identifying, correcting, and replacing distorted systems and patterns of thinking. If you are interested in learning more about this book, you can find it on Amazon with over 1,400 reviews to help you evaluate its effectiveness.

To hear more about Burns’ work in the treatment of depression, check out his TED talk on the subject below.

As Burns discusses in the above video, his studies of depression have also influenced the studies around joy and self-esteem. The most researched form of psychotherapy right now is covered by his book, Feeling Good, aimed at providing tools to the general public.

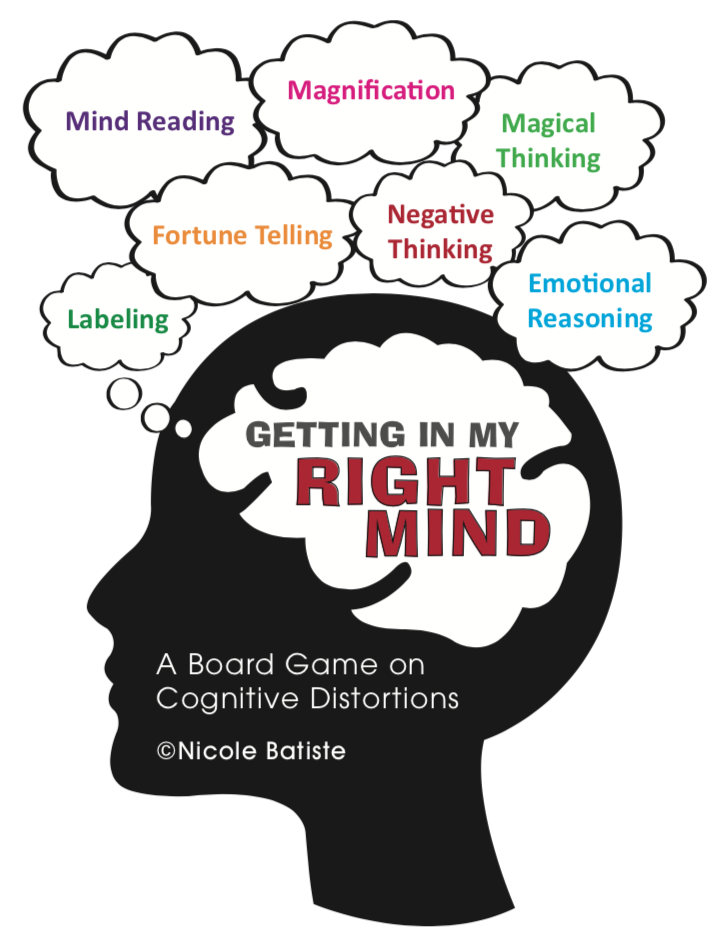

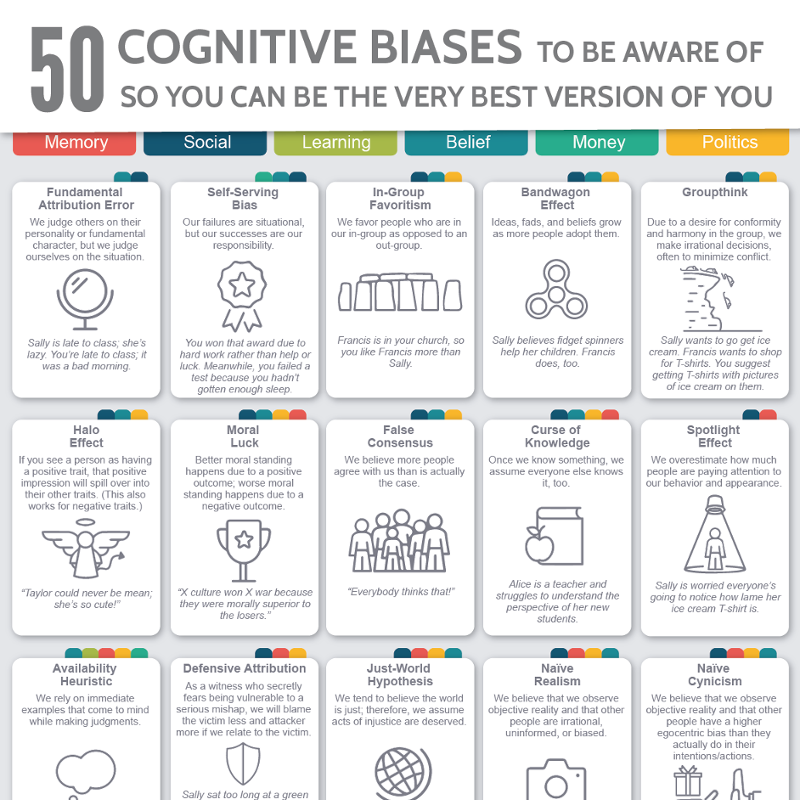

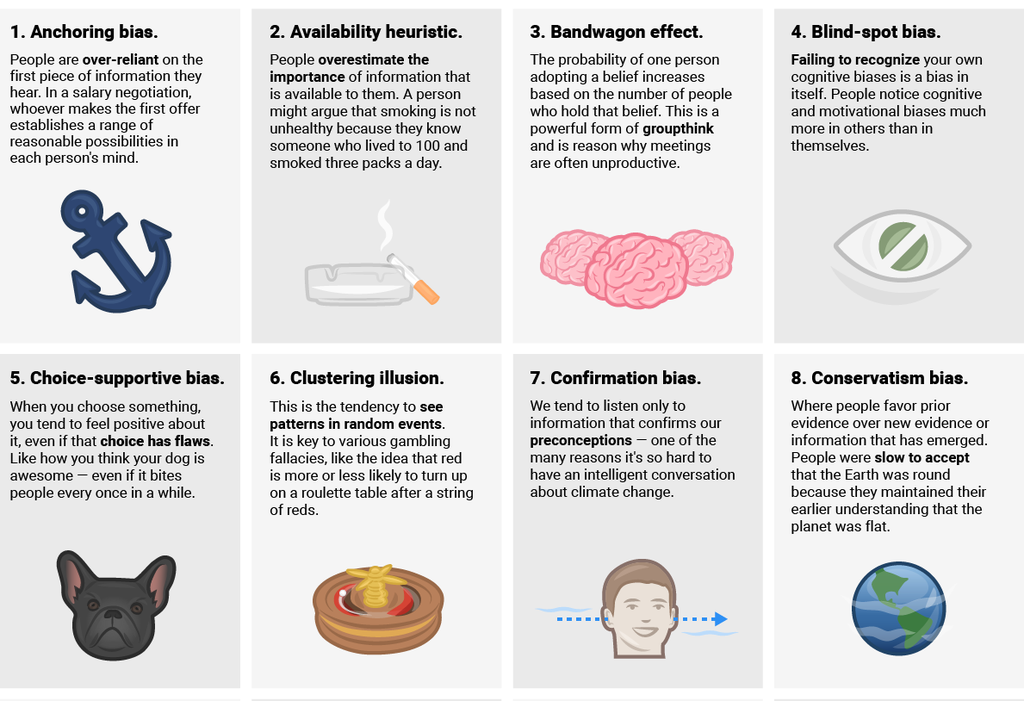

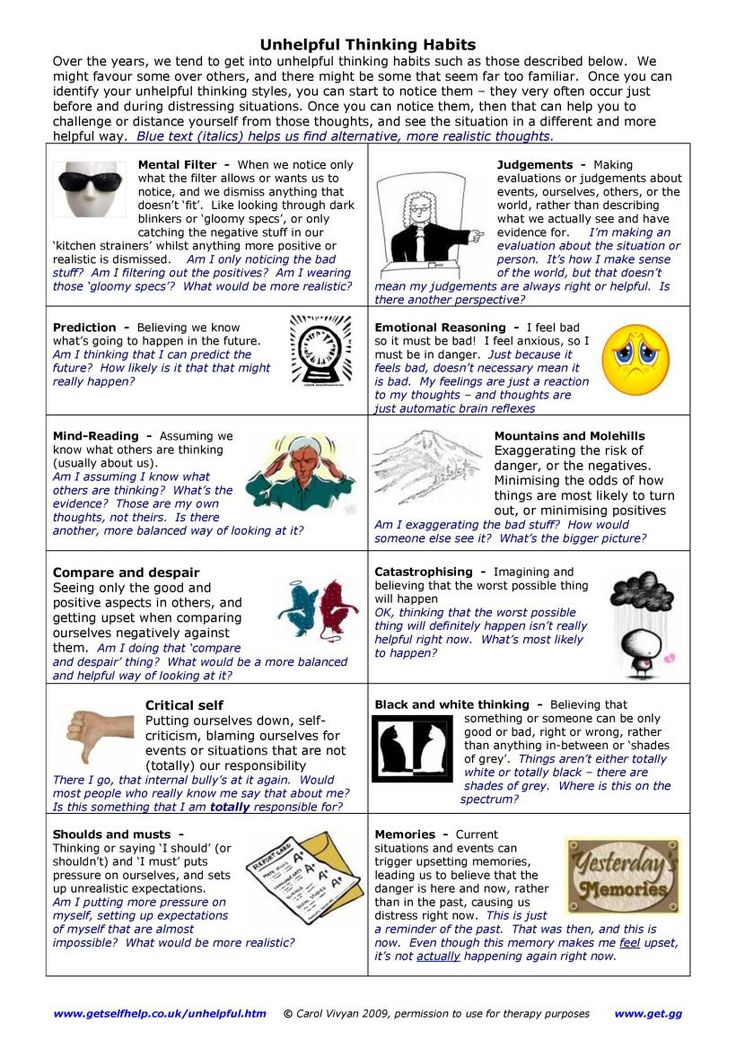

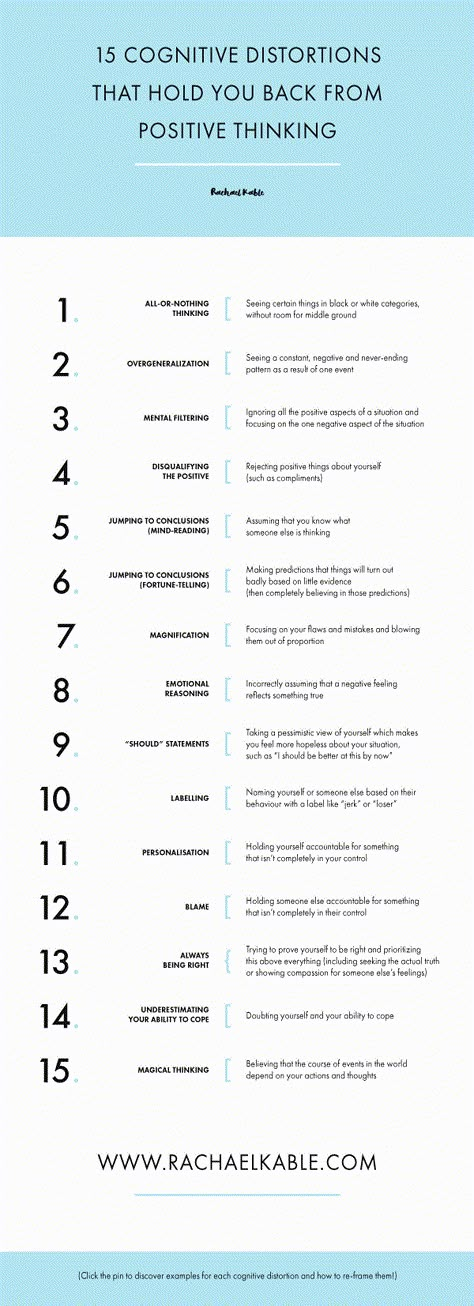

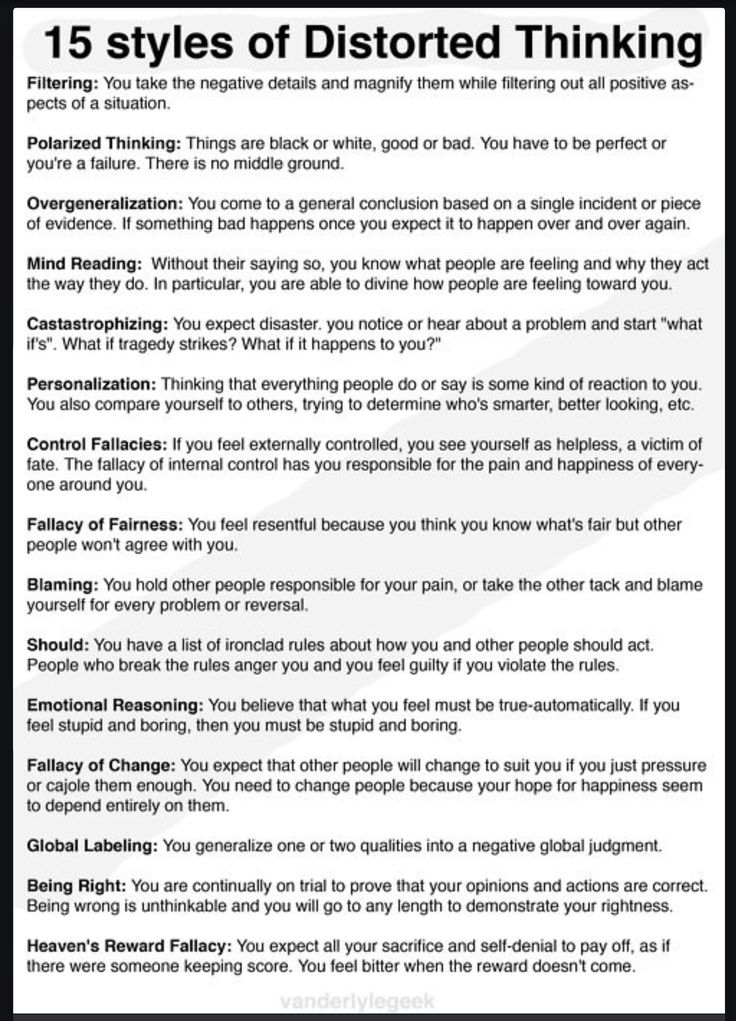

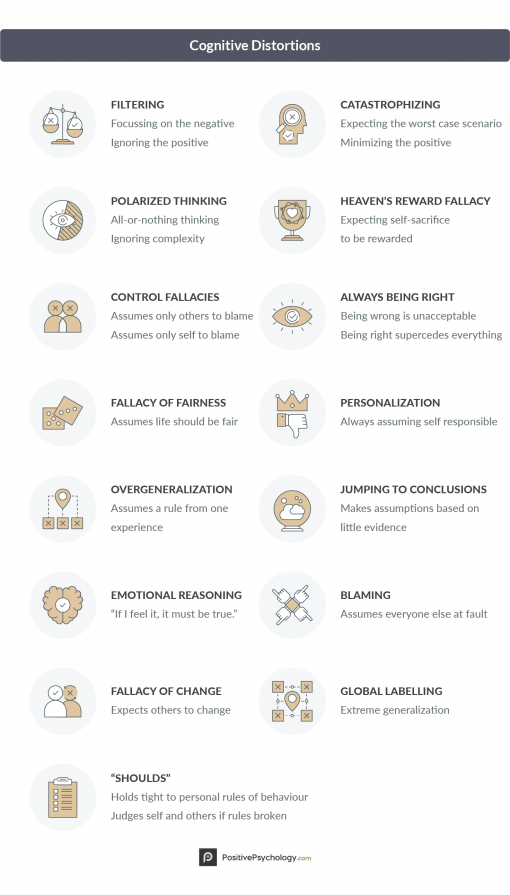

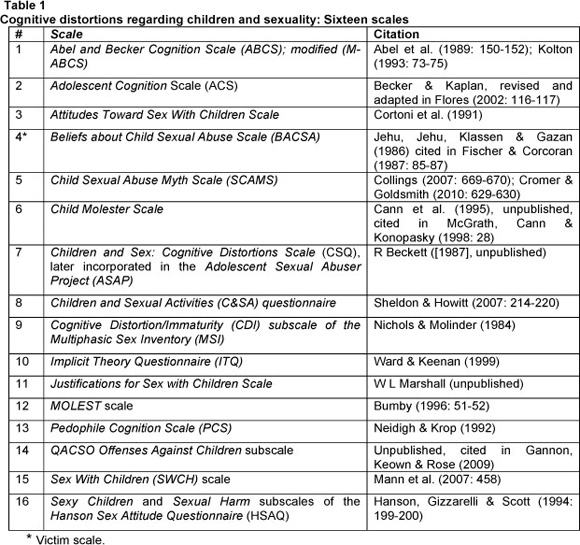

A List of the Most Common Cognitive Distortions

Beck and Burns are not the only two researchers who have dedicated their careers to learn more about depression, cognitive distortions, and treatment for these conditions.

There are many others who have picked up the torch for this research, often with their own take on cognitive distortions. As such, there are numerous cognitive distortions floating around in the literature, but we’ll limit this list to the most common sixteen.

As such, there are numerous cognitive distortions floating around in the literature, but we’ll limit this list to the most common sixteen.

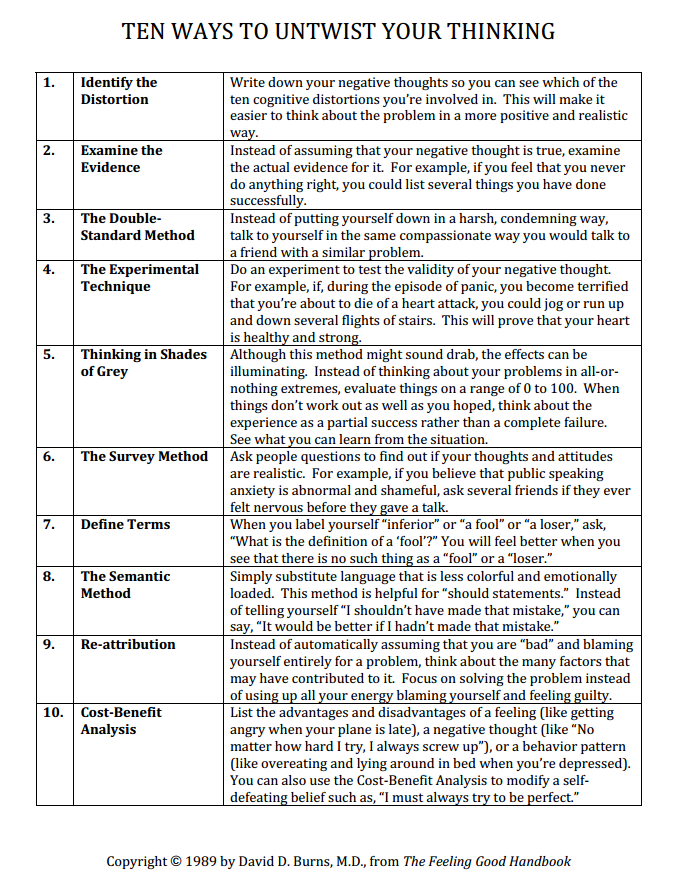

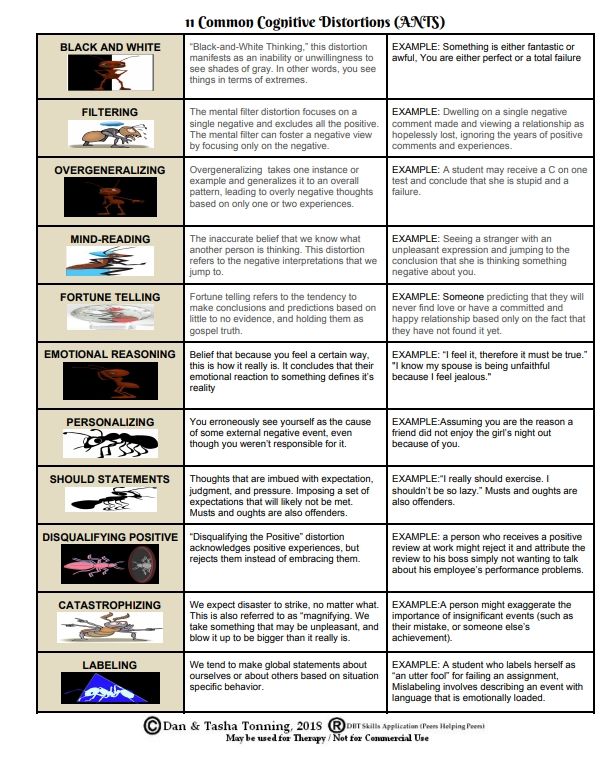

The first eleven distortions come straight from Burns’ Feeling Good Handbook (1989).

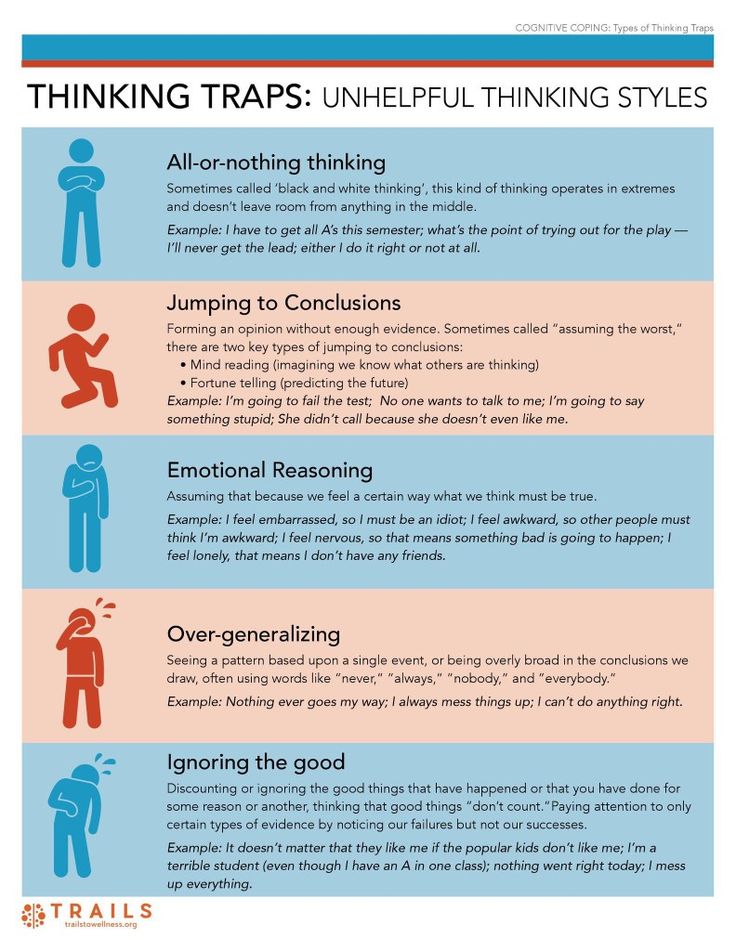

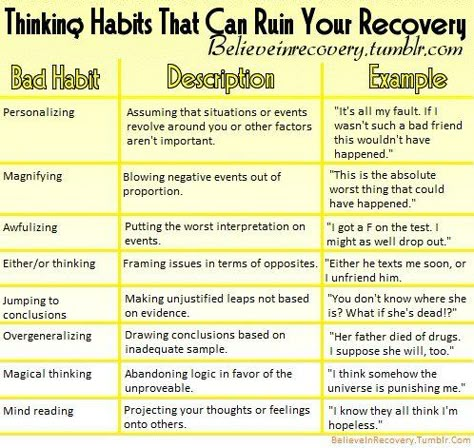

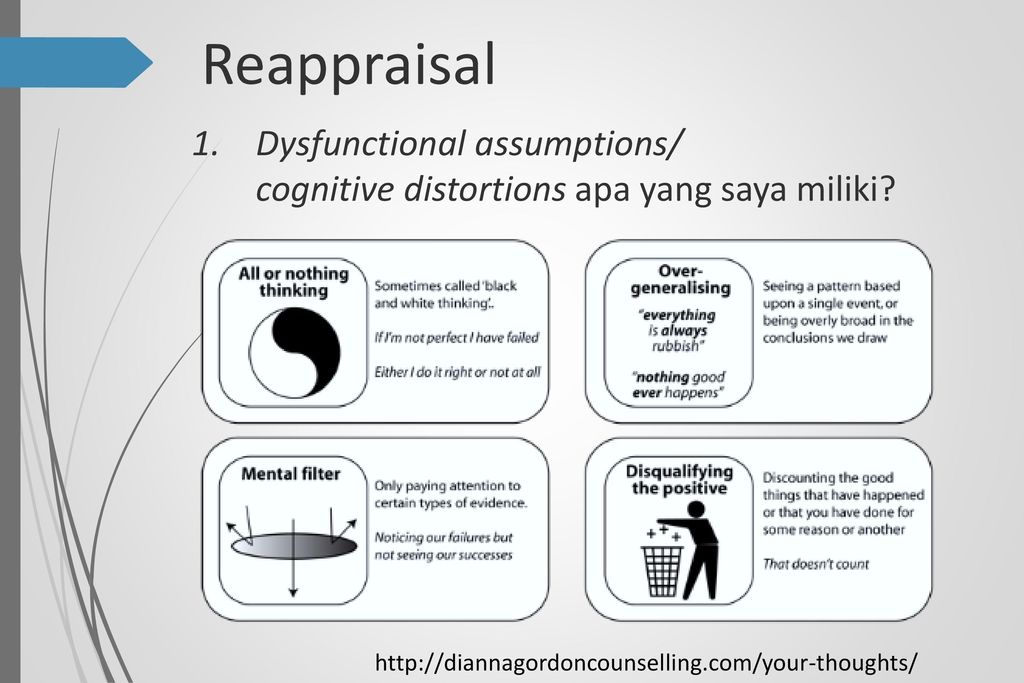

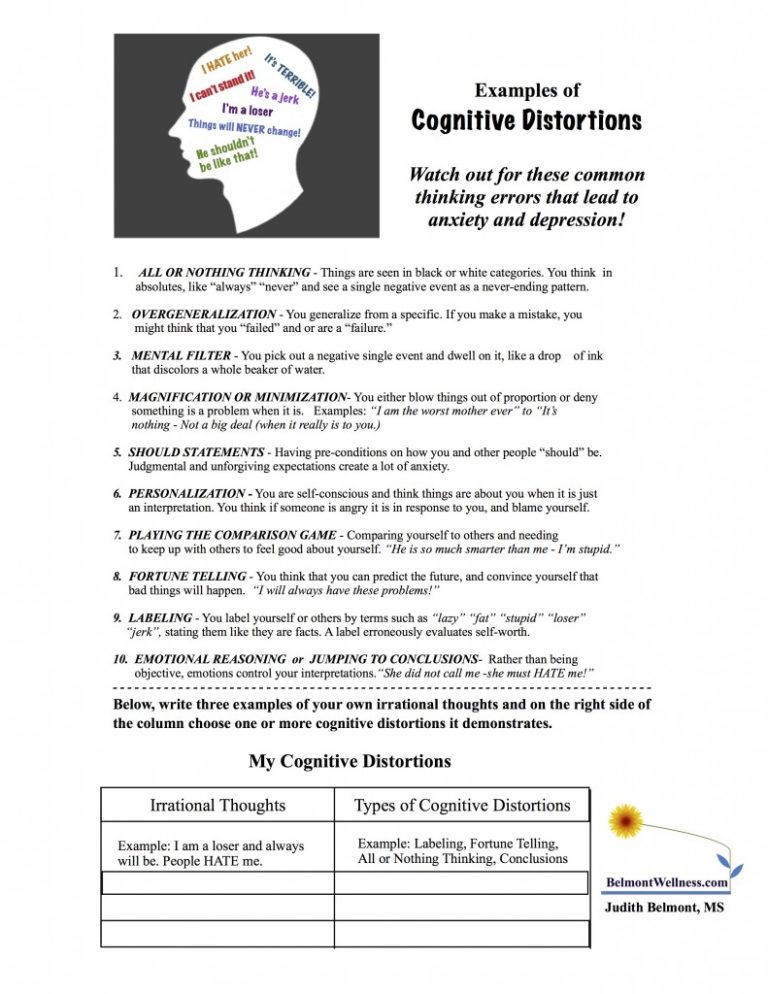

1. All-or-Nothing Thinking / Polarized Thinking

Also known as “Black-and-White Thinking,” this distortion manifests as an inability or unwillingness to see shades of gray. In other words, you see things in terms of extremes – something is either fantastic or awful, you believe you are either perfect or a total failure.

2. Overgeneralization

This sneaky distortion takes one instance or example and generalizes it to an overall pattern. For example, a student may receive a C on one test and conclude that she is stupid and a failure. Overgeneralizing can lead to overly negative thoughts about yourself and your environment based on only one or two experiences.

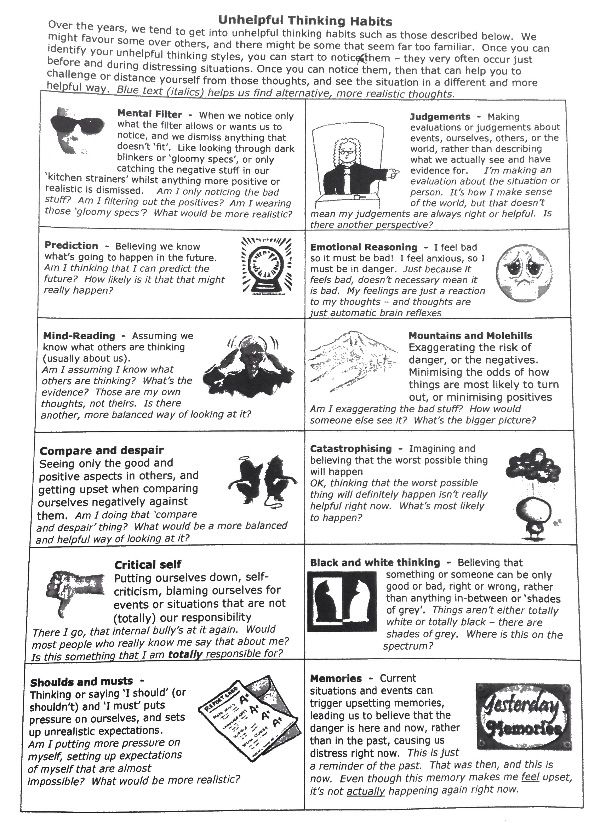

3. Mental Filter

Similar to overgeneralization, the mental filter distortion focuses on a single negative piece of information and excludes all the positive ones. An example of this distortion is one partner in a romantic relationship dwelling on a single negative comment made by the other partner and viewing the relationship as hopelessly lost, while ignoring the years of positive comments and experiences.

The mental filter can foster a decidedly pessimistic view of everything around you by focusing only on the negative.

4. Disqualifying the Positive

On the flip side, the “Disqualifying the Positive” distortion acknowledges positive experiences but rejects them instead of embracing them.

For example, a person who receives a positive review at work might reject the idea that they are a competent employee and attribute the positive review to political correctness, or to their boss simply not wanting to talk about their employee’s performance problems.

This is an especially malignant distortion since it can facilitate the continuation of negative thought patterns even in the face of strong evidence to the contrary.

5.

Jumping to Conclusions – Mind Reading

Jumping to Conclusions – Mind ReadingThis “Jumping to Conclusions” distortion manifests as the inaccurate belief that we know what another person is thinking. Of course, it is possible to have an idea of what other people are thinking, but this distortion refers to the negative interpretations that we jump to.

Seeing a stranger with an unpleasant expression and jumping to the conclusion that they are thinking something negative about you is an example of this distortion.

6. Jumping to Conclusions – Fortune Telling

A sister distortion to mind reading, fortune telling refers to the tendency to make conclusions and predictions based on little to no evidence and holding them as gospel truth.

One example of fortune-telling is a young, single woman predicting that she will never find love or have a committed and happy relationship based only on the fact that she has not found it yet. There is simply no way for her to know how her life will turn out, but she sees this prediction as fact rather than one of several possible outcomes.

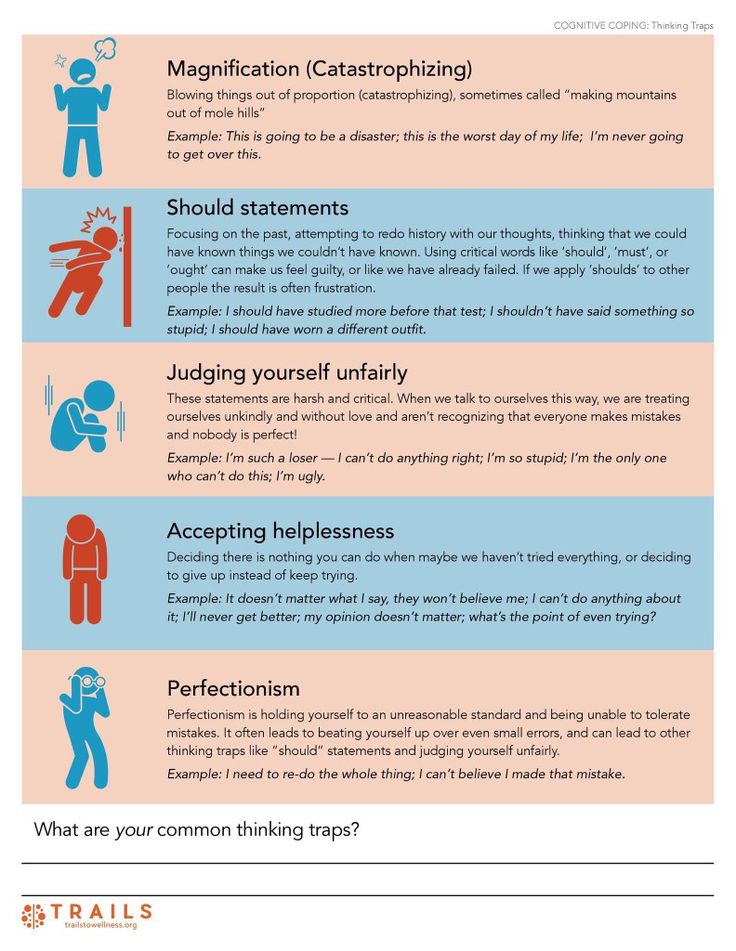

7. Magnification (Catastrophizing) or Minimization

Also known as the “Binocular Trick” for its stealthy skewing of your perspective, this distortion involves exaggerating or minimizing the meaning, importance, or likelihood of things.

An athlete who is generally a good player but makes a mistake may magnify the importance of that mistake and believe that he is a terrible teammate, while an athlete who wins a coveted award in her sport may minimize the importance of the award and continue believing that she is only a mediocre player.

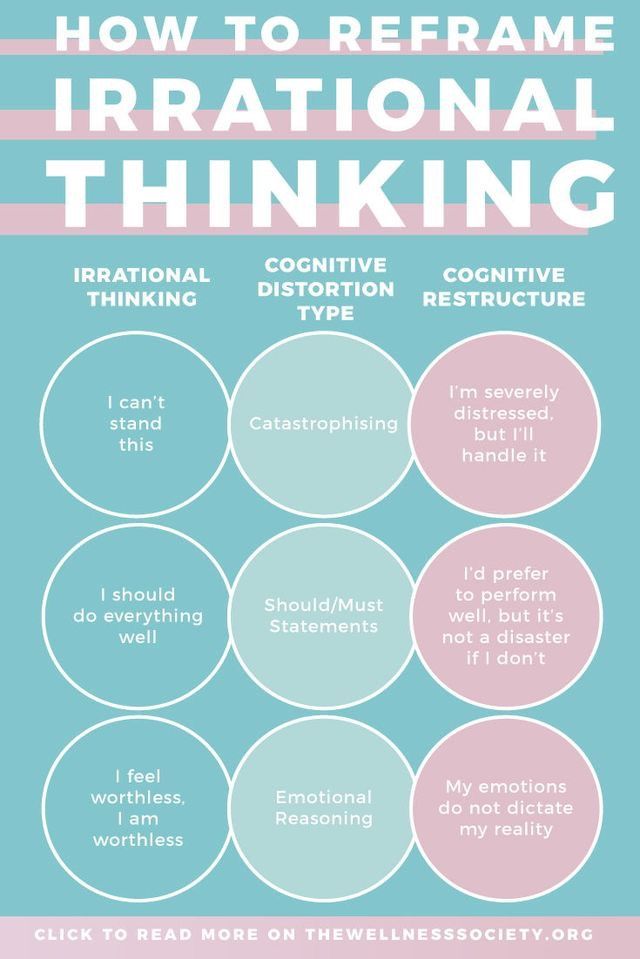

8. Emotional Reasoning

This may be one of the most surprising distortions to many readers, and it is also one of the most important to identify and address. The logic behind this distortion is not surprising to most people; rather, it is the realization that virtually all of us have bought into this distortion at one time or another.

Emotional reasoning refers to the acceptance of one’s emotions as fact. It can be described as “I feel it, therefore it must be true. ” Just because we feel something doesn’t mean it is true; for example, we may become jealous and think our partner has feelings for someone else, but that doesn’t make it true. Of course, we know it isn’t reasonable to take our feelings as fact, but it is a common distortion nonetheless.

” Just because we feel something doesn’t mean it is true; for example, we may become jealous and think our partner has feelings for someone else, but that doesn’t make it true. Of course, we know it isn’t reasonable to take our feelings as fact, but it is a common distortion nonetheless.

Relevant: What is Emotional Intelligence? + 18 Ways to Improve It

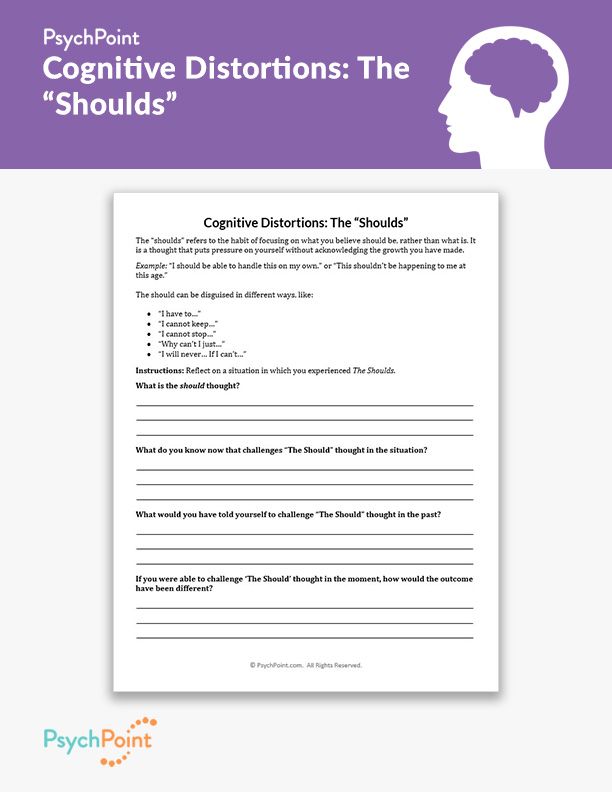

9. Should Statements

Another particularly damaging distortion is the tendency to make “should” statements. Should statements are statements that you make to yourself about what you “should” do, what you “ought” to do, or what you “must” do. They can also be applied to others, imposing a set of expectations that will likely not be met.

When we hang on too tightly to our “should” statements about ourselves, the result is often guilt that we cannot live up to them. When we cling to our “should” statements about others, we are generally disappointed by their failure to meet our expectations, leading to anger and resentment.

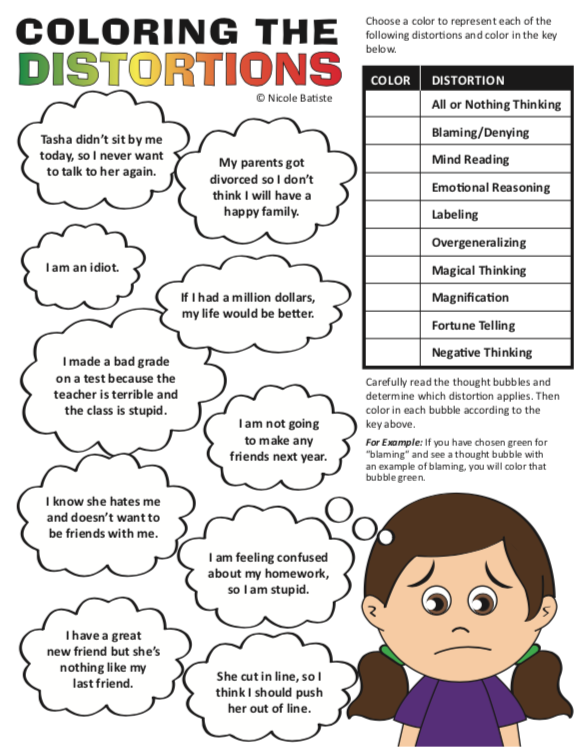

10. Labeling and Mislabeling

These tendencies are basically extreme forms of overgeneralization, in which we assign judgments of value to ourselves or to others based on one instance or experience.

For example, a student who labels herself as “an utter fool” for failing an assignment is engaging in this distortion, as is the waiter who labels a customer “a grumpy old miser” if he fails to thank the waiter for bringing his food. Mislabeling refers to the application of highly emotional, loaded, and inaccurate or unreasonable language when labeling.

11. Personalization

As the name implies, this distortion involves taking everything personally or assigning blame to yourself without any logical reason to believe you are to blame.

This distortion covers a wide range of situations, from assuming you are the reason a friend did not enjoy the girls’ night out, to the more severe examples of believing that you are the cause for every instance of moodiness or irritation in those around you.

In addition to these basic cognitive distortions, Beck and Burns have mentioned a few others (Beck, 1976; Burns, 1980):

12. Control Fallacies

A control fallacy manifests as one of two beliefs: (1) that we have no control over our lives and are helpless victims of fate, or (2) that we are in complete control of ourselves and our surroundings, giving us responsibility for the feelings of those around us. Both beliefs are damaging, and both are equally inaccurate.

No one is in complete control of what happens to them, and no one has absolutely no control over their situation. Even in extreme situations where an individual seemingly has no choice in what they do or where they go, they still have a certain amount of control over how they approach their situation mentally.

13. Fallacy of Fairness

While we would all probably prefer to operate in a world that is fair, the assumption of an inherently fair world is not based in reality and can foster negative feelings when we are faced with proof of life’s unfairness.

A person who judges every experience by its perceived fairness has fallen for this fallacy, and will likely feel anger, resentment, and hopelessness when they inevitably encounter a situation that is not fair.

14. Fallacy of Change

Another ‘fallacy’ distortion involves expecting others to change if we pressure or encourage them enough. This distortion is usually accompanied by a belief that our happiness and success rests on other people, leading us to believe that forcing those around us to change is the only way to get what we want.

A man who thinks “If I just encourage my wife to stop doing the things that irritate me, I can be a better husband and a happier person” is exhibiting the fallacy of change.

15. Always Being Right

Perfectionists and those struggling with Imposter Syndrome will recognize this distortion – it is the belief that we must always be right. For those struggling with this distortion, the idea that we could be wrong is absolutely unacceptable, and we will fight to the metaphorical death to prove that we are right.

For example, the internet commenters who spend hours arguing with each other over an opinion or political issue far beyond the point where reasonable individuals would conclude that they should “agree to disagree” are engaging in the “Always Being Right” distortion. To them, it is not simply a matter of a difference of opinion, it is an intellectual battle that must be won at all costs.

16. Heaven’s Reward Fallacy

This distortion is a popular one, and it’s easy to see myriad examples of this fallacy playing out on big and small screens across the world. The “Heaven’s Reward Fallacy” manifests as a belief that one’s struggles, one’s suffering, and one’s hard work will result in a just reward.

It is obvious why this type of thinking is a distortion – how many examples can you think of, just within the realm of your personal acquaintances, where hard work and sacrifice did not pay off?

Sometimes no matter how hard we work or how much we sacrifice, we will not achieve what we hope to achieve. To think otherwise is a potentially damaging pattern of thought that can result in disappointment, frustration, anger, and even depression when the awaited reward does not materialize.

To think otherwise is a potentially damaging pattern of thought that can result in disappointment, frustration, anger, and even depression when the awaited reward does not materialize.

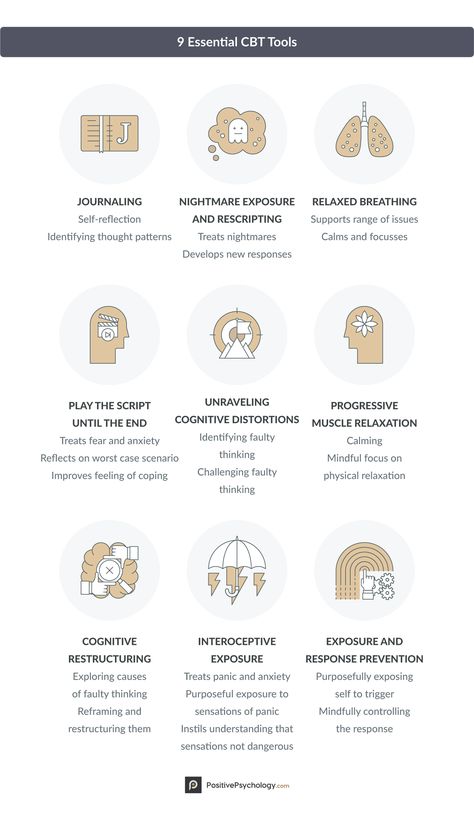

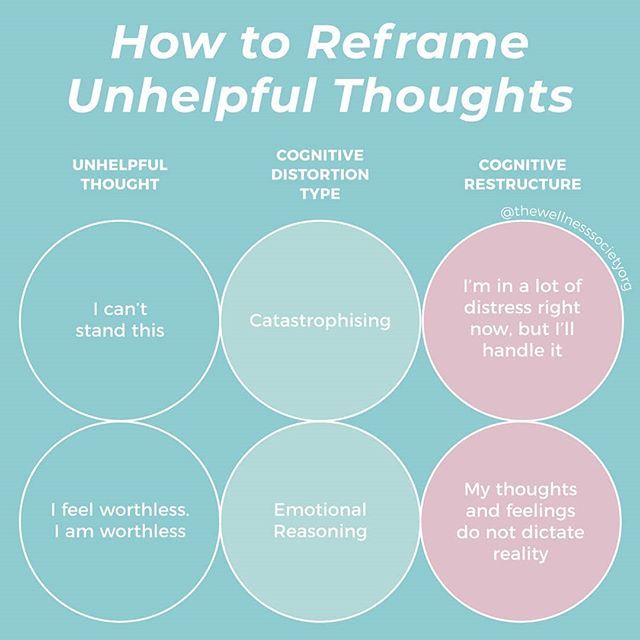

Changing Your Thinking: Examples of Techniques to Combat Cognitive Distortions

These distortions, while common and potentially extremely damaging, are not something we must simply resign ourselves to living with.

Beck, Burns, and other researchers in this area have developed numerous ways to identify, challenge, minimize, or erase these distortions from our thinking.

Some of the most effective and evidence-based techniques and resources are listed below.

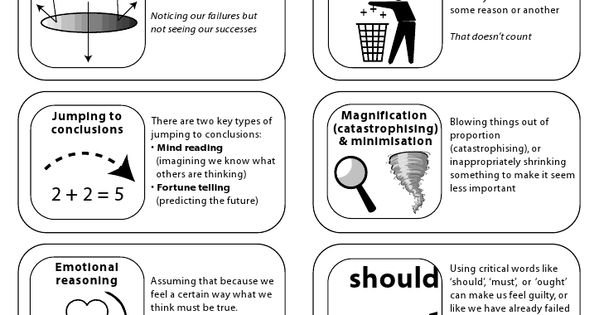

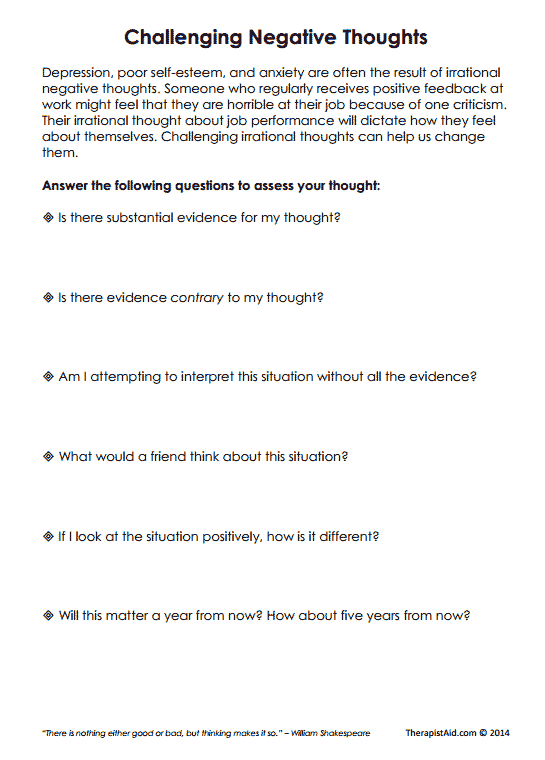

Cognitive Distortions Handout

Since you must first identify the distortions you struggle with before you can effectively challenge them, this resource is a must-have.

The Cognitive Distortions handout lists and describes several types of cognitive distortions to help you figure out which ones you might be dealing with.

The distortions listed include:

- All-or-Nothing Thinking;

- Overgeneralizing;

- Discounting the Positive;

- Jumping to Conclusions;

- Mind Reading;

- Fortune Telling;

- Magnification (Catastrophizing) and Minimizing;

- Emotional Reasoning;

- Should Statements;

- Labeling and Mislabeling;

- Personalization.

The descriptions are accompanied by helpful descriptions and a couple of examples.

This information can be found in the Increasing Awareness of Cognitive Distortions exercise in the Positive Psychology Toolkit©.

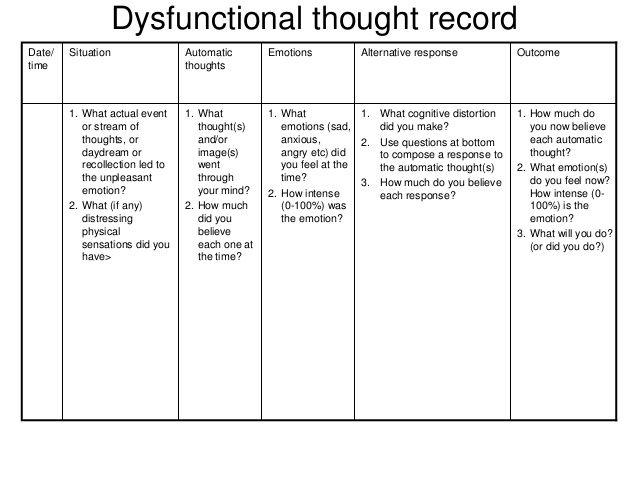

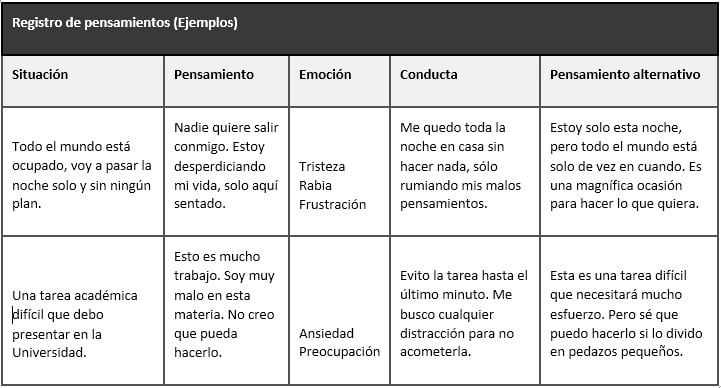

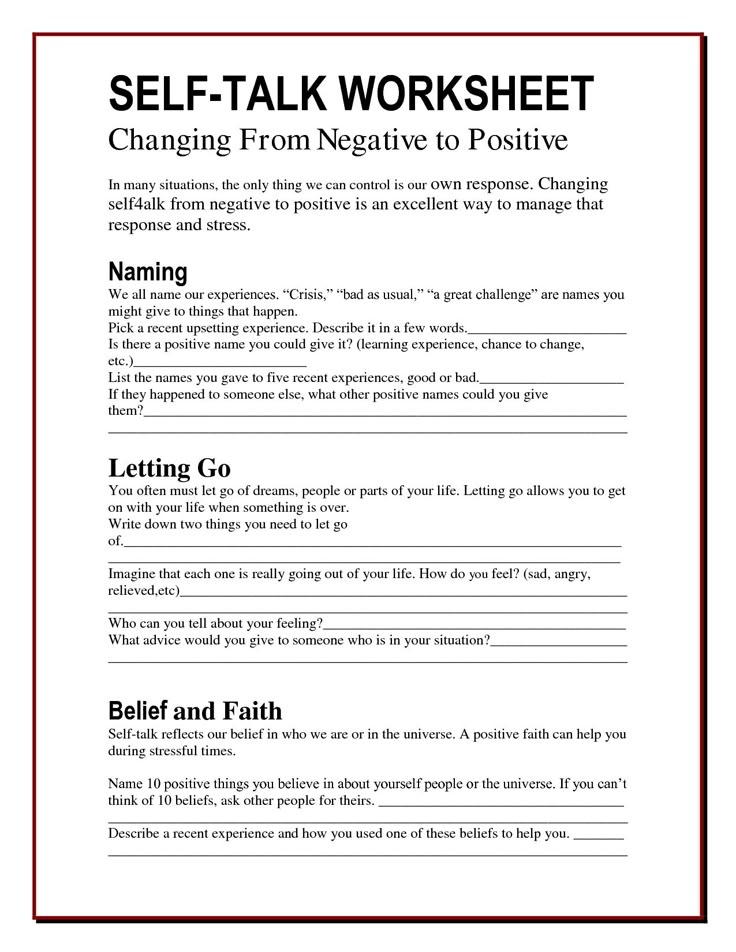

Automatic Thought Record

This worksheet is an excellent tool for identifying and understanding your cognitive distortions. Our automatic, negative thoughts are often related to a distortion that we may or may not realize we have. Completing this exercise can help you to figure out where you are making inaccurate assumptions or jumping to false conclusions.

The worksheet is split into six columns:

- Date/Time

- Situation

- Automatic Thoughts (ATs)

- Emotion/s

- Your Response

- A More Adaptive Response

First, you note the date and time of the thought.

In the second column, you will write down the situation. Ask yourself:

- What led to this event?

- What caused the unpleasant feelings I am experiencing?

The third component of the worksheet directs you to write down the negative automatic thought, including any images or feelings that accompanied the thought. You will consider the thoughts and images that went through your mind, write them down, and determine how much you believed these thoughts.

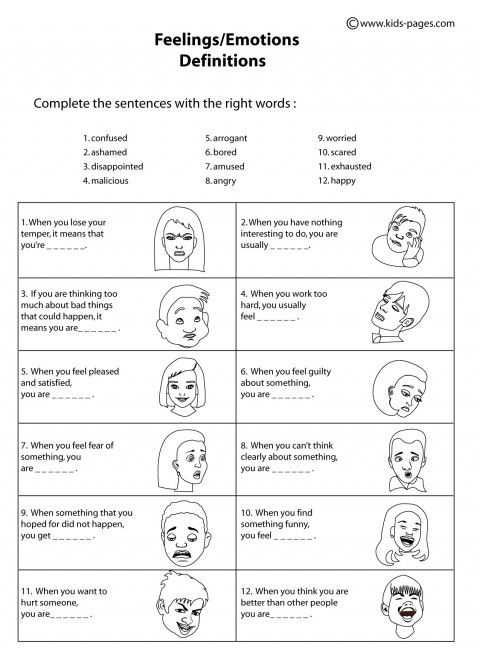

After you have identified the thought, the worksheet instructs you to note the emotions that ran through your mind along with the thoughts and images identified. Ask yourself what emotions you felt at the time and how intense the emotions were on a scale from 1 (barely felt it) to 10 (completely overwhelming).

Next, you have an opportunity to come up with an adaptive response to those thoughts. This is where the real work happens, where you identify the distortions that are cropping up and challenge them.

Ask yourself these questions:

- Which cognitive distortions were you employing?

- What is the evidence that the automatic thought(s) is true, and what evidence is there that it is not true?

- You’ve thought about the worst that can happen, but what’s the best that could happen? What’s the most realistic scenario?

- How likely are the best-case and most realistic scenarios?

Finally, you will consider the outcome of this event. Think about how much you believe the automatic thought now that you’ve come up with an adaptive response, and rate your belief. Determine what emotion(s) you are feeling now and at what intensity you are experiencing them.

You can access the Automatic Thought Record Worksheet here.

Decatastrophizing

This is a particularly good tool for talking yourself out of catastrophizing a situation.

The worksheet begins with a description of cognitive distortions in general and catastrophizing in particular; catastrophizing is when you distort the importance or meaning of a problem to be much worse than it is, or you assume that the worst possible scenario is going to come to pass. It’s a reinforcing distortion, as you get more and more anxious the more you think about it, but there are ways to combat it.

First, write down your worry. Identify the issue you are catastrophizing by answering the question, “What are you worried about?”

Once you have articulated the issue that is worrying you, you can move on to thinking about how this issue will turn out.

Think about how terrible it would be if the catastrophe actually came to pass. What is the worst-case scenario? Consider whether a similar event has occurred in your past and, if so, how often it occurred. With the frequency of this catastrophe in mind, make an educated guess of how likely the worst-case scenario is to happen.

After this, think about what is most likely to happen–not the best possible outcome, not the worst possible outcome, but the most likely. Consider this scenario in detail and write it down. Note how likely you think this scenario is to happen as well.

Next, think about your chances of surviving in one piece. How likely is it that you’ll be okay one week from now if your fear comes true? How likely is it that you’ll be okay in one month? How about one year? For all three, write down “Yes” if you think you’d be okay and “No” if you don’t think you’d be okay.

Finally, come back to the present and think about how you feel right now. Are you still just as worried, or did the exercise help you think a little more realistically? Write down how you’re feeling about it.

This worksheet can be an excellent resource for anyone who is worrying excessively about a potentially negative event.

You can download the Decatastrophizing Worksheet here.

Cataloging Your Inner Rules

Cognitive distortions include assumptions and rules that we hold dearly or have decided we must live by. Sometimes these rules or assumptions help us to stick to our values or our moral code, but often they can limit and frustrate us.

Sometimes these rules or assumptions help us to stick to our values or our moral code, but often they can limit and frustrate us.

This exercise can help you to think more critically about an assumption or rule that may be harmful.

First, think about a recent scenario where you felt bad about your thoughts or behavior afterward. Write down a description of the scenario and the infraction (what you did to break the rule).

Next, based on your infraction, identify the rule or assumption that was broken. What are the parameters of the rule? How does it compel you to think or act?

Once you have described the rule or assumption, think about where it came from. Consider when you acquired this rule, how you learned about it, and what was happening in your life that encouraged you to adopt it. What makes you think it’s a good rule to have?

Now that you have outlined a definition of the rule or assumption and its origins and impact on your life, you can move on to comparing its advantages and disadvantages. Every rule or assumption we follow will likely have both advantages and disadvantages.

Every rule or assumption we follow will likely have both advantages and disadvantages.

The presence of one advantage does not mean the rule or assumption is necessarily a good one, just as the presence of one disadvantage does not automatically make the rule or assumption a bad one. This is where you must think critically about how the rule or assumption helps and/or hurts you.

Finally, you have an opportunity to think about everything you have listed and decide to either accept the rule as it is, throw it out entirely and create a new one, or modify it into a rule that would suit you better. This may be a small change or a big modification.

If you decide to change the rule or assumption, the new version should maximize the advantages of the rule, minimize or limit the disadvantages, or both. Write down this new and improved rule and consider how you can put it into practice in your daily life.

You can download the Cataloging Your Inner Rules Worksheet.

Facts or Opinions?

This is one of the first lessons that participants in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) learn – that facts are not opinions. As obvious as this seems, it can be difficult to remember and adhere to this fact in your day to day life.

As obvious as this seems, it can be difficult to remember and adhere to this fact in your day to day life.

This exercise can help you learn the difference between fact and opinion, and prepare you to distinguish between your own opinions and facts.

The worksheet lists the following fifteen statements and asks the reader to decide whether they are fact or opinion:

- I am a failure.

- I’m uglier than him/her.

- I said “no” to a friend in need.

- A friend in need said “no” to me.

- I suck at everything.

- I yelled at my partner.

- I can’t do anything right.

- He said some hurtful things to me.

- She didn’t care about hurting me.

- This will be an absolute disaster.

- I’m a bad person.

- I said things I regret.

- I’m shorter than him.

- I am not loveable.

- I’m selfish and uncaring.

- Everyone is a way better person than I am.

- Nobody could ever love me.

- I am overweight for my height.

- I ruined the evening.

- I failed my exam.

Practicing making this distinction between fact and opinion can improve your ability to quickly differentiate between the two when they pop up in your own thoughts.

Here is the Facts or Opinions Worksheet.

In case you’re wondering which is which, here is the key:

- I am a failure. False

- I’m uglier than him/her. False

- I said “no” to a friend in need. True

- A friend in need said “no” to me. True

- I suck at everything. False

- I yelled at my partner. True

- I can’t do anything right. False

- He said some hurtful things to me. True

- She didn’t care about hurting me. False

- This will be an absolute disaster. False

- I’m a bad person. False

- I said things I regret. True

- I’m shorter than him. True

- I am not loveable.

False

False - I’m selfish and uncaring. False

- Everyone is a way better person than I am. False

- Nobody could ever love me. False

- I am overweight for my height. True

- I ruined the evening. False

- I failed my exam. True

Putting Thoughts on Trial

This exercise uses CBT theory and techniques to help you examine your irrational thoughts. You will act as the defense attorney, prosecutor, and judge all at once, providing evidence for and against the irrational thought and evaluating the merit of the thought based on this evidence.

The worksheet begins with an explanation of the exercise and a description of the roles you will be playing.

The first box to be completed is “The Thought.” This is where you write down the irrational thought that is being put on trial.

Next, you fill out “The Defense” box with evidence that corroborates or supports the thought. Once you have listed all of the defense’s evidence, do the same for “The Prosecution” box. Write down all of the evidence calling the thought into question or instilling doubt in its accuracy.

Once you have listed all of the defense’s evidence, do the same for “The Prosecution” box. Write down all of the evidence calling the thought into question or instilling doubt in its accuracy.

When you have listed all of the evidence you can think of, both for and against the thought, evaluate the evidence and write down the results of your evaluation in “The Judge’s Verdict” box.

This worksheet is a fun and engaging way to think critically about your negative or irrational thoughts and make good decisions about which thoughts to modify and which to embrace.

Click here to see this worksheet for yourself (TherapistAid).

A Take-Home Message

Hopefully, this piece has given you a good understanding of cognitive distortions. These sneaky, inaccurate patterns of thinking and believing are common, but their potential impact should not be underestimated.

Even if you are not struggling with depression, anxiety, or another serious mental health issue, it doesn’t hurt to evaluate your own thoughts every now and then. The sooner you catch a cognitive distortion and mount a defense against it, the less likely it is to make a negative impact on your life.

The sooner you catch a cognitive distortion and mount a defense against it, the less likely it is to make a negative impact on your life.

What is your experience with cognitive distortions? Which ones do you struggle with? Do you think we missed any important ones? How have you tackled them, whether in CBT or on your own?

Let us know in the comments below. We love hearing from you.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. For more information, don’t forget to download our 3 Positive CBT Exercises for free.

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapies and emotional disorders. New York, NY: New American Library.

- Burns, D. D. (1980). Feeling good: The new mood therapy. New York, NY: New American Library.

- Burns, D. D. (1989). The feeling good handbook. New York, NY: Morrow.

- Burns, D. D., Shaw, B. F., & Croker, W. (1987). Thinking styles and coping strategies of depressed women: An empirical investigation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 25, 223-225.

- Feeling Good. (n.d.). About. Feeling Good. Retrieved from https://feelinggood.com/about/

- GoodTherapy. (2015). Aaron Beck. GoodTherapy LLC. Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/famous-psychologists/aaron-beck.html

- Summit for Clinical Excellence. (n.d.). David Burns, MD. Summit for clinical excellence faculty page. Retrieved from https://summitforclinicalexcellence.com/partners/faculty/david-burns/

- TherapistAid. (n.d.). Cognitive restructuring: Thoughts on trial. Retrieved from https://www.therapistaid.com/worksheets/putting-thoughts-on-trial.pdf

Berns - Nice And Easy

This is a way of analyzing your own cognitive distortions, which was invented and described in the book "Feeling Good" by David Burns.

Cognitive distortion is a systematic deviation in thinking and decisions.

"Feeling well" on Alpina's website

The most convenient way is to write the algorithm in Google forms so that you don't have to search for the right questions every time. My example.

My example.

1. Describe a situation that caused unpleasant emotions. It should be an emotionless description, like a security camera is watching you. nine0003

Ira said she didn't want to meet me

I overslept

Petya called me an idiot

2. Remember what emotions you experienced.

Irritation

Anger

Disappointment

Resentment

Sadness

3. How strong each emotion was from 1 to 10.

4. Describe the automatic thoughts that then arose. Do not try to interpret or rewrite them as you think - just write.

- It will never end and there is no way to get rid of it. I will spend my energy again, this will not lead to any result or money

- I am not appreciated

- Zhenya always reproaches me, even if I do something well

- She does not consider my needs and believes that I should solve problems that worries her faster than it happens

- Again, I was not asked. They always plan without asking my opinion

- I don't want to, but I agree because I have to

- There must be something wrong with me

5. Determine what disorders are in these thoughts

Determine what disorders are in these thoughts

Dichotomous thinking

Only black or white evaluation. There is no 90% success, and a silver medal is not a medal. “If I don’t succeed at least in some small way, then I am a failure.”

What to do? Stop going to extremes when evaluating different situations, evaluate events in percentage terms, gradually reducing the level of your maximalism and perfectionism. nine0016

Duty

Unreasonably high demands on oneself, other people and the world as a whole, deviation from which is unacceptable.

“It's terrible that I was wrong. I must always and in everything succeed.

What to do? To admit the possibility of mistakes, to recognize the uniqueness of other people, to replace shoulds with wishes, i.e. alternative healthy thoughts and reasonable preferences like “I would like to…, but this does not mean at all…”, “I want…, but this does not guarantee…”. nine0016

nine0016

Catastrophization

This is about exaggerating the scale of the problems: everything seems to be a complete failure. It is pointless to clarify the situation: after all, it is immediately clear that we are not facing some kind of problem, but everything, give up, a disaster.

"As soon as I get upset, everything is gone - from now on I will not succeed at all."

What to do? Stop making a big deal out of molehills, assess the likelihood of this or that event happening, and critically analyze your thoughts. nine0016

Thought filter and emotional reliance

“It doesn't matter that I got some good test results. It is important that among them there is one bad result, and it says that I am a lazy person who could not prepare properly.

"I'm a failure because I feel like this."

What to do? Switch attention to the positive aspects of the situation and to find ways to solve the problem, look at events from different points of view. nine0016

nine0016

Labeling

"I'm a loser", "He's a bore".

What to do? Understand that mistakes are normal, and a person does not become someone after a one-time behavior

Depreciation

Works in both directions: positive and negative. In the first case, you do not notice the benefits, in the second you smooth out the fakups.

“Indeed, this time I managed to get the job done. But this does not mean at all that I am capable - I just got lucky this time. nine0016

What to do? Recognize the true significance of events and realistically assess their individual qualities.

Personalization

Taking responsibility for events beyond your control.

The search for the cause of what is happening begins with oneself. The wife at home could yell at the master, or, for example, a bad cutlet from the stomach. But a person with a cognitive distortion knows exactly where the reason is - he is used to the fact that all the problems in the world are caused precisely by his actions. nine0016

But a person with a cognitive distortion knows exactly where the reason is - he is used to the fact that all the problems in the world are caused precisely by his actions. nine0016

“The repairman was rude to me; it's because I did something wrong."

What to do? Find evidence for your assumptions, look at a particular situation through the eyes of an independent observer.

Exaggeration and understatement

“A perfect mark on an exam doesn't mean I'm smart. But the average mark shows exactly that I am incapable.

What to do? Stop exaggerating the size of difficulties and see their real scale, especially since a person can withstand almost anything. nine0016

Overgeneralization

Inflating one case into law.

"Yesterday I couldn't make myself sit down to work: that means I can never make myself sit down at the table."

"I don't know how to meet people at all because I was embarrassed at the party yesterday. "

"

What to do? Start from real facts and concrete evidence, replace negative definitions with neutral ones.

The ability to read other people's minds

"He thinks I don't understand anything about this job."

It also works in the opposite direction: if I read other people's thoughts, then people easily read mine.

What to do? To understand the impossibility of knowing exactly what other people think and feel, and the impossibility of the opposite situation, to confirm their suspicions with real facts.

Comparison

Constantly comparing yourself to other people in order to show your superiority, which leads to frustration.

What to do? Refuse comparisons, which are the source of unstable self-esteem, to understand that all people have strengths and weaknesses.

Intolerance to discomfort

Intolerance of unpleasant conditions, which leads to the avoidance of uncomfortable situations.

“Getting up early in the morning is terrible”, “I have to eat now, or it will be unbearable”, “If they refuse me, I won’t survive it.”

What to do? Rely on previous positive experience of similar situations, understand the real degree of discomfort.

One could - sounds like a must

A "Possibility Statement" is a consequence of everyday emotional turmoil. When the actual behavior of an individual is far below his standards, the "possible" and "impossible" cause feelings of self-disgust, shame and a guilt complex. nine0016

When people's actions fall below your expectations for them, there may also be a false, non-depressive lift. You can avoid this by making your demands realistic and not trying to measure your actions by the same limits that other people seem to use.

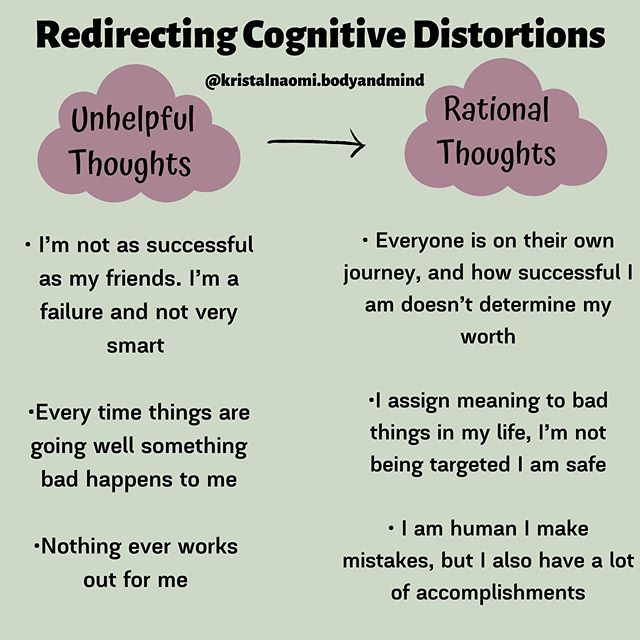

6. Now that you have seen the distortion, write a rationale for the situation. It will never end and there is no way to get rid of it. I will spend my energy again, it will not lead to results or money

I will spend my energy again, it will not lead to results or money

Answer: There is obligation and overgeneralization.

Sometimes it's worth taking on a job, even when it's unpleasant. Every job will eventually end. Even this one can be stopped right now, just by sending the guys a letter: sorry, but I'm tired and it's not worth it. But I won't do it, not because it can't be done, but because I don't want to.

Claim: I feel like I'm considered incompetent. nine0014 Answer: This is personalization and mind reading. I don’t know why the customer refused to work, maybe he just doesn’t have money or it doesn’t matter. It is more rational to ask directly, rather than speculate.

7. How do I now feel about the initial emotion on a scale of 0 to 10?

Done. Now the voltage level should be lower. Repeat if necessary. If you can't handle it, see a psychotherapist.

Jellyfish on how to choose a psychotherapist

11 cognitive distortions that make you think that everything in life is bad

What to do when the whole world is against you

Do you know the feeling when it seems that the whole world is against you?

When does it feel like you're surrounded by idiots? That nothing will change in your life and you will be a loser?

If you answered yes to any of the questions above, chances are you are a miserable whiner. But don't worry, it can be fixed. Surely you are a good person who simply allowed not the most pleasant thoughts to take over his mind. nine0003

At least that's what psychologist David Burns thinks in his book Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy, which helped popularize CBT. Burns identifies 11 common cognitive biases that make people feel completely miserable.

These distortions are erroneous thought patterns that make the world around you icteric and nauseating when you start thinking about how you feel about yourself and those you know. According to the postulates of cognitive behavioral therapy, the main reason why people feel unhappy is that their thoughts are on edge. Correct erroneous mental models, and you will get rid of negative feelings. nine0003

According to the postulates of cognitive behavioral therapy, the main reason why people feel unhappy is that their thoughts are on edge. Correct erroneous mental models, and you will get rid of negative feelings. nine0003

We at 1Gai.ru have collected 11 distortions that make people feel unhappy. With definitions from Burns and a checklist to help you recognize distortion in your own life.

1. All or Nothing Thinking

Alex Padurariu / unsplash.com

You think in black and white terms, as if there are no shades of gray in life.

"If I never write a bestseller, I'll be a failure all my life." nine0003

"What I believe is not perfect, so it's all a lie."

"She forgot about my birthday, so it's better not to build a relationship with her."

But the reality is that most things in our lives are not black and white. Such dualistic thinking is not true. Life is full of nuances. A goal can be worthwhile, even if it doesn't involve absolute success. And something good can always be found both in imperfect people and in imperfect philosophy. nine0003

And something good can always be found both in imperfect people and in imperfect philosophy. nine0003

See also

9 cognitive distortions that involuntarily change our behavior

2. Excessive generalization

Hannah XU / UNSPLASH.com

You generalize some specific shortage, failure or error and error and error and error and error and error and error project it onto yourself. Or you are projecting current feelings and some negative experience that you just had into the future.

Overgeneralization is when you give too much importance to discrete disorder. For example, you make a mistake in a work paper and decide that you are incompetent in the profession. Take it out on your kids and decide you're a bad parent. nine0003

Overgeneralization is often associated with the words "always" and "never": you make a harsh comment to your girlfriend and think: "I always ruin my relationship. " You skip one workout and immediately say, "I'll never get in shape."

" You skip one workout and immediately say, "I'll never get in shape."

You can apply generalization not only to yourself, but also to other people. Take a specific flaw and decide that it indicates the character of the person as a whole. For example, because your colleague whistles annoyingly, you think that he is inattentive. Completely forgetting that he always brings something delicious to meetings and helps troubleshoot software. nine0003

3. Mental filtering

Abigail / unsplash.com

You ignore the positive and focus entirely on the negative.

Your mind is like duct tape for negatives and Teflon for positives. Bad things are constantly stuck in your head, and good things float away into the realm of unconsciousness.

See also

7 signs that will help you understand that you have low self-esteem

4. Devaluing the positive

Zac Durant / unsplash. com

com

You convince yourself that your positive qualities or successes do not count.

It has to do with mental filtering. The difference is that you recognize positive qualities in yourself or in another person, and then convince yourself that they mean nothing.

"My last idea was highly appreciated, but it won't get me any closer to a promotion."

"Yes, I lost a little weight this week, but it doesn't matter, I still look fat." nine0003

"This woman may have said that I look good, but probably only for the sake of appearances."

5. Mind reading

You jump to conclusions about what others think and feel without any hard evidence.

We can't read minds, but that doesn't stop us from trying. And when we do this, we usually assume - without any reason or evidence - that they think something bad about us.

“The boss didn’t say anything after my presentation… She probably thinks I did a bad job. ” nine0003

” nine0003

"This woman smirked at me because I'm unattractive."

"My friend didn't reply to my message because I'm not important to her."

6. Catastrophism

Carolina Heza / Unsplash

You make arbitrary and disturbing predictions about the future.

You make seemingly logical leaps between a catalytic cause and subsequent potential effects. And thus you create a chain, which eventually leads to an illogical final conclusion. For example:

“I got a D in math. This means that you can forget about a good GPA in the certificate. If there is no certificate, there will be no good work. You will have to live with your parents for the rest of your life.”

A little jump in this way of thinking seems reasonable. But it is unlikely that the chain leading from a low grade at the university to a lonely old age can be considered logical.

See also

28 psychological facts that really work

7.

Exaggeration and minimization

Exaggeration and minimization

Einar H. Reynis / unsplash.com

You exaggerate the negative and downplay the positive.

Seeing the world through a lens that magnifies the negative and minimizes the positive - a lens of constant pessimism - contributes to depression and decreased motivation. If you only see the flaws in your job (cold boss) and minimize the positives (nice colleagues), you'll find it hard to get out of bed every morning. nine0003

8. Emotional thinking

Joanna Nix-Walkup / unsplash.com

Sense-based reasoning: “I feel like an idiot, so I should be” or “I feel hopeless, so I never will get better."

After a terrible fight with your significant other, you think, "She's the worst person in my life and we have no future." And after a romantic date, they are sure: “She is the only one for me. I've never been so happy." nine0003

So which of these is true?

Feelings fluctuate. And while emotions can be a source of reasoning, they need to be trained to match your intelligence. People who engage in maladaptive emotional reasoning completely replace consciousness with feeling. As a result, the latter becomes their reality.

And while emotions can be a source of reasoning, they need to be trained to match your intelligence. People who engage in maladaptive emotional reasoning completely replace consciousness with feeling. As a result, the latter becomes their reality.

If they feel bad, there must be something wrong with them or with the world around them. But this is not always the case. Sometimes you feel sluggish for no specific reason. Sometimes you suffer from "emotional contagion", and a bad day at work starts to affect your relationship with your family. Sometimes circumstances overlap and form a cluster of chaos. But they also represent a deviation, not the norm, from which any conclusions can be drawn. nine0003

See also

Without a smartphone: 9 things to think about to pass the time

9. Statements of need

Jackson Simmer / unsplash.com from the “you should” category

“Must” are expectations and standards that are arbitrary in nature. We can feel guilty when we don't live the way we think we should (even if we don't have to). We get angry and upset when people and the way the world works do not match our expectations. Even if these expectations are unfair and unfounded. nine0003

We can feel guilty when we don't live the way we think we should (even if we don't have to). We get angry and upset when people and the way the world works do not match our expectations. Even if these expectations are unfair and unfounded. nine0003

10. Labeling

Andrew Coop / unsplash.com

This is an extreme form of overgeneralization in which you try to establish the "essence" of yourself or other people with a single word label.

If overgeneralization occurs when we draw general conclusions based on one particular belief or behavior, then in labeling we completely ignore ourselves or others, grouping difficult people into one-dimensional categories:

"You've lost your temper again, so you're a loser."

"Your brother didn't repay my debt, he's a swindler!"

"If someone belongs to political party X, he is a jerk."

See also

6 psychological reasons that will explain why you are a hypersensitive person

11.

Personalization and accusation

Personalization and accusation

mikerindersblog.org

You blame yourself for your zone of your responsibility. And you blame others, not noticing how you yourself could contribute to the conflict. nine0016

When errors and conflicts occur, their cause is complex. Often the problem occurs not only with you, but also with another person.

How to get rid of

So how to get rid of these inadequate mental scenarios?

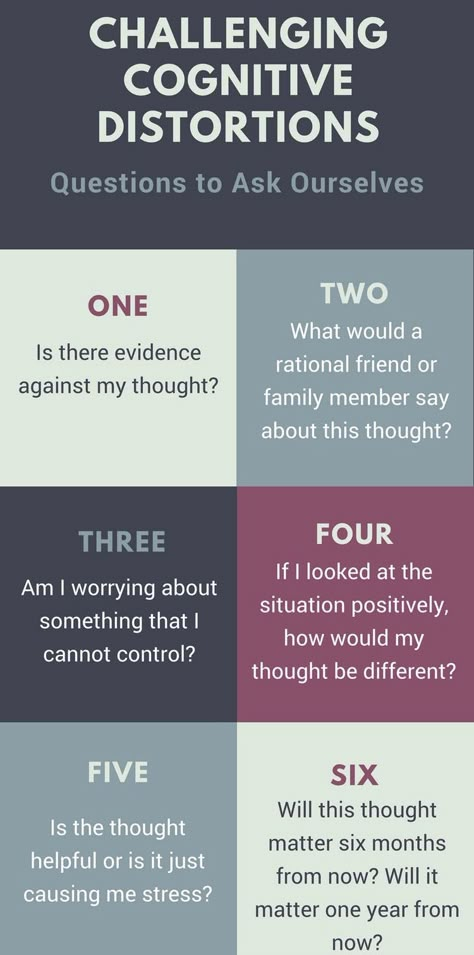

Step 1. Easy to recognize. Beware of cognitive distortions when talking to yourself and others.

Step 2. Challenge your negative thought patterns.

If you make a mistake at work and think you're a failure, ask yourself if that's true. Yes, the report turned out to be imperfect, but in other areas of life you are still doing well. You have a happy family. You are confidently moving towards your fitness goal. And most of the working days do not make such mistakes.