Feel for others

Empathy Definition | What Is Empathy

Scroll To Top

What is Empathy?

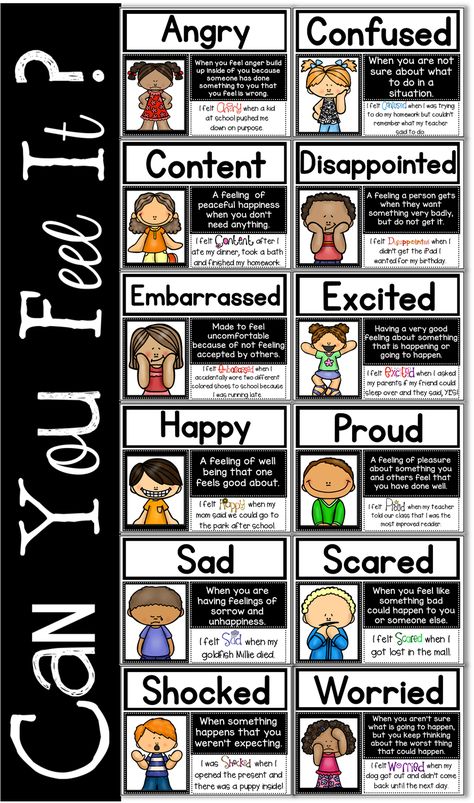

The term “empathy” is used to describe a wide range of experiences. Emotion researchers generally define empathy as the ability to sense other people’s emotions, coupled with the ability to imagine what someone else might be thinking or feeling.

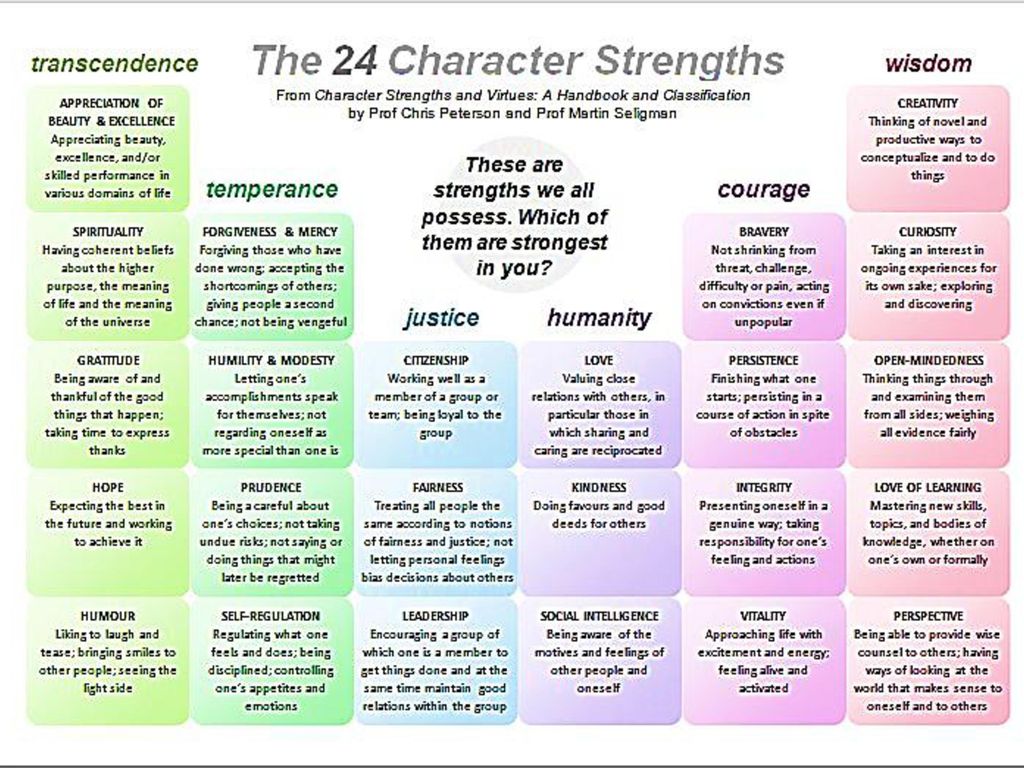

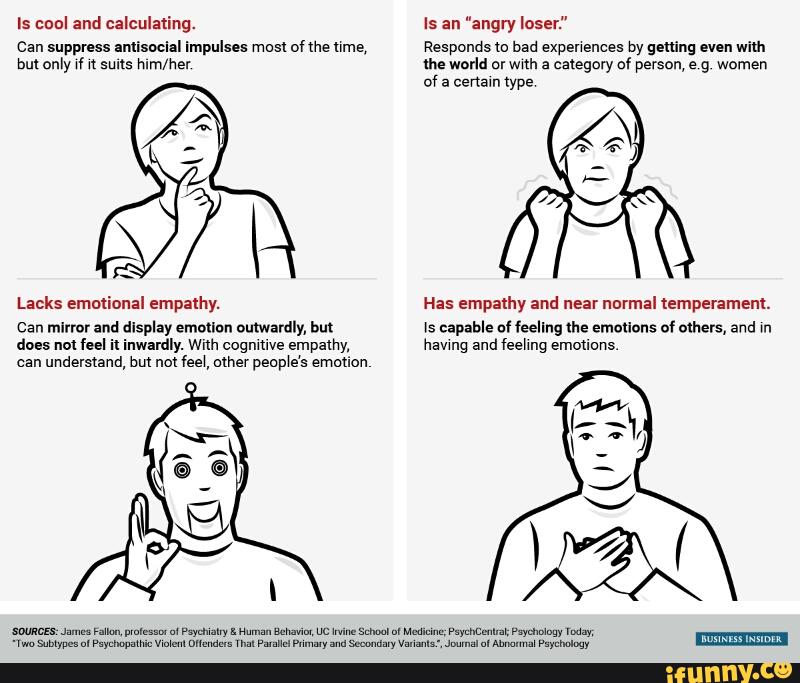

Contemporary researchers often differentiate between two types of empathy: “Affective empathy” refers to the sensations and feelings we get in response to others’ emotions; this can include mirroring what that person is feeling, or just feeling stressed when we detect another’s fear or anxiety. “Cognitive empathy,” sometimes called “perspective taking,” refers to our ability to identify and understand other people’s emotions. Studies suggest that people with autism spectrum disorders have a hard time empathizing.

Empathy seems to have deep roots in our brains and bodies, and in our evolutionary history. Elementary forms of empathy have been observed in our primate relatives, in dogs, and even in rats. Empathy has been associated with two different pathways in the brain, and scientists have speculated that some aspects of empathy can be traced to mirror neurons, cells in the brain that fire when we observe someone else perform an action in much the same way that they would fire if we performed that action ourselves. Research has also uncovered evidence of a genetic basis to empathy, though studies suggest that people can enhance (or restrict) their natural empathic abilities.

Having empathy doesn’t necessarily mean we’ll want to help someone in need, though it’s often a vital first step toward compassionate action.

For more: Read Frans de Waal’s essay on “The Evolution of Empathy” and Daniel Goleman’s overview of different forms of empathy, drawing on the work of Paul Ekman.

What are the Limitations?

Featured Articles

Why Practice It?

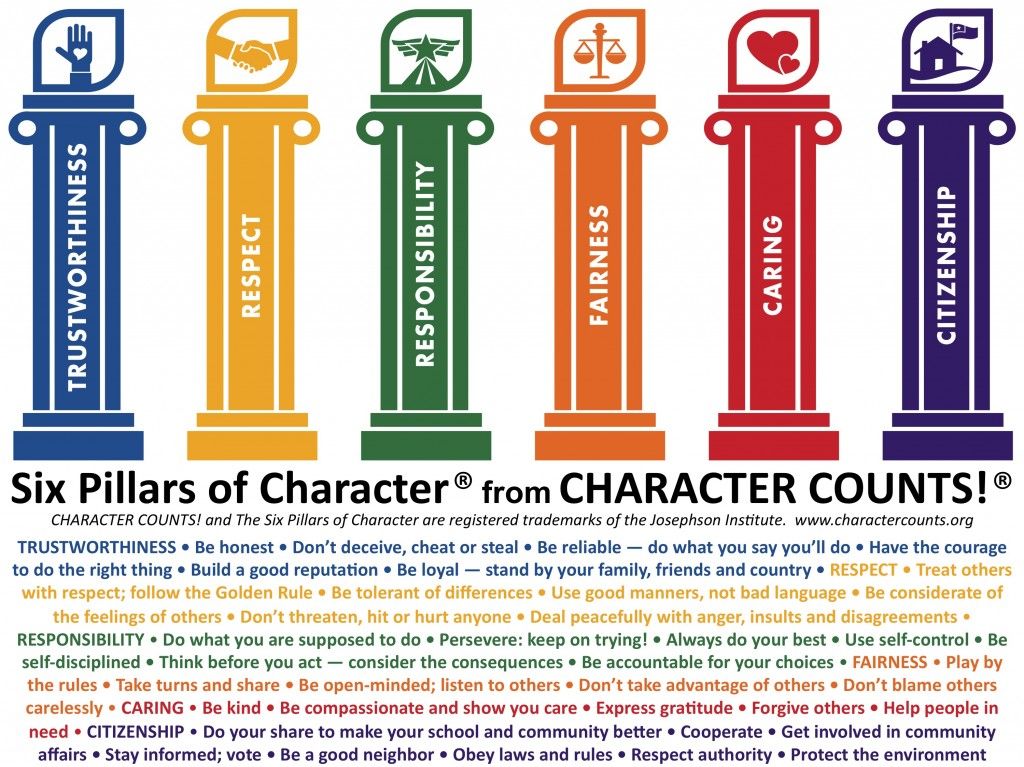

Empathy is a building block of morality—for people to follow the Golden Rule, it helps if they can put themselves in someone else’s shoes. It is also a key ingredient of successful relationships because it helps us understand the perspectives, needs, and intentions of others. Here are some of the ways that research has testified to the far-reaching importance of empathy.

- Seminal studies by Daniel Batson and Nancy Eisenberg have shown that people higher in empathy are more likely to help others in need, even when doing so cuts against their self-interest.

- Empathy is contagious: When group norms encourage empathy, people are more likely to be empathic—and more altruistic.

- Empathy reduces prejudice and racism: In one study, white participants made to empathize with an African American man demonstrated less racial bias afterward.

- Empathy is good for your marriage: Research suggests being able to understand your partner’s emotions deepens intimacy and boosts relationship satisfaction; it’s also fundamental to resolving conflicts.

(The GGSC’s Christine Carter has written about effective strategies for developing and expressing empathy in relationships.)

(The GGSC’s Christine Carter has written about effective strategies for developing and expressing empathy in relationships.) - Empathy reduces bullying: Studies of Mary Gordon’s innovative Roots of Empathy program have found that it decreases bullying and aggression among kids, and makes them kinder and more inclusive toward their peers. An unrelated study found that bullies lack “affective empathy” but not cognitive empathy, suggesting that they know how their victims feel but lack the kind of empathy that would deter them from hurting others.

- Empathy reduces suspensions: In one study, students of teachers who participated in an empathy training program were half as likely to be suspended, compared to students of teachers who didn’t participate.

- Empathy promotes heroic acts: A seminal study by Samuel and Pearl Oliner found that people who rescued Jews during the Holocaust had been encouraged at a young age to take the perspectives of others.

- Empathy fights inequality.

As Robert Reich and Arlie Hochschild have argued, empathy encourages us to reach out and want to help people who are not in our social group, even those who belong to stigmatized groups, like the poor. Conversely, research suggests that inequality can reduce empathy: People show less empathy when they attain higher socioeconomic status.

As Robert Reich and Arlie Hochschild have argued, empathy encourages us to reach out and want to help people who are not in our social group, even those who belong to stigmatized groups, like the poor. Conversely, research suggests that inequality can reduce empathy: People show less empathy when they attain higher socioeconomic status. - Empathy is good for the office: Managers who demonstrate empathy have employees who are sick less often and report greater happiness.

- Empathy is good for health care: A large-scale study found that doctors high in empathy have patients who enjoy better health; other research suggests training doctors to be more empathic improves patient satisfaction and the doctors’ own emotional well-being.

- Empathy is good for police: Research suggests that empathy can help police officers increase their confidence in handling crises, diffuse crises with less physical force, and feel less distant from the people they’re dealing with.

For more: Learn about why we should teach empathy to preschoolers.

Featured Articles

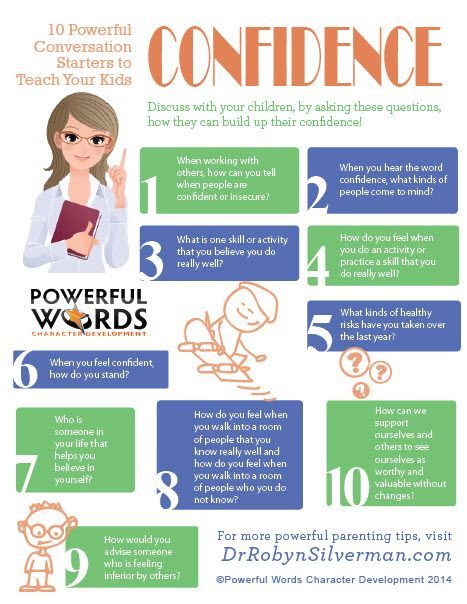

How Do I Cultivate It?

Humans experience affective empathy from infancy, physically sensing their caregivers’ emotions and often mirroring those emotions. Cognitive empathy emerges later in development, around three to four years of age, roughly when children start to develop an elementary “theory of mind”—that is, the understanding that other people experience the world differently than they do.

From these early forms of empathy, research suggests we can develop more complex forms that go a long way toward improving our relationships and the world around us. Here are some specific, science-based activities for cultivating empathy from our site Greater Good in Action:

- Active listening: Express active interest in what the other person has to say and make him or her feel heard.

- Shared identity: Think of a person who seems to be very different from you, and then list what you have in common.

- Put a human face on suffering: When reading the news, look for profiles of specific individuals and try to imagine what their lives have been like.

- Eliciting altruism: Create reminders of connectedness.

And here are some of the keys that researchers have identified for nurturing empathy in ourselves and others:

- Focus your attention outwards: Being mindfully aware of your surroundings, especially the behaviors and expressions of other people, is crucial for empathy. Indeed, research suggests practicing mindfulness helps us take the perspectives of other people yet not feel overwhelmed when we encounter their negative emotions.

- Get out of your own head: Research shows we can increase our own level of empathy by actively imagining what someone else might be experiencing.

- Don’t jump to conclusions about others: We feel less empathy when we assume that people suffering are somehow getting what they deserve.

- Show empathic body language: Empathy is expressed not just by what we say, but by our facial expressions, posture, tone of voice, and eye contact (or lack thereof).

- Meditate: Neuroscience research by Richard Davidson and his colleagues suggests that meditation—specifically loving-kindness meditation, which focuses attention on concern for others—might increase the capacity for empathy among short-term and long-term meditators alike (though especially among long-time meditators).

- Explore imaginary worlds: Research by Keith Oatley and colleagues has found that people who read fiction are more attuned to others’ emotions and intentions.

- Join the band: Recent studies have shown that playing music together boosts empathy in kids.

- Play games: Neuroscience research suggests that when we compete against others, our brains are making a “mental model” of the other person’s thoughts and intentions.

- Take lessons from babies: Mary Gordon’s Roots of Empathy program is designed to boost empathy by bringing babies into classrooms, stimulating children’s basic instincts to resonate with others’ emotions.

- Combat inequality: Research has shown that attaining higher socioeconomic status diminishes empathy, perhaps because people of high SES have less of a need to connect with, rely on, or cooperate with others. As the gap widens between the haves and have-nots, we risk facing an empathy gap as well. This doesn’t mean money is evil, but if you have a lot of it, you might need to be more intentional about maintaining your own empathy toward others.

- Pay attention to faces: Pioneering research by Paul Ekman has found we can improve our ability to identify other people’s emotions by systematically studying facial expressions. Take our Emotional Intelligence Quiz for a primer, or check out Ekman’s F.A.C.E. program for more rigorous training.

- Believe that empathy can be learned: People who think their empathy levels are changeable put more effort into being empathic, listening to others, and helping, even when it’s challenging.

For more: The Ashoka Foundation’s Start Empathy initiative tracks educators’ best practices for teaching empathy. The initiative gave awards to 14 programs judged to do the best job at educating for empathy. The nonprofit Playworks also offers eight strategies for developing empathy in children.

What Are the Pitfalls and Limitations of Empathy?

According to research, we’re more likely to help a single sufferer than a large group of faceless victims, and we empathize more with in-group members than out-group members. Does this reflect a defect in empathy itself? Some critics believe so, while others argue that the real problem is how we suppress our own empathy.

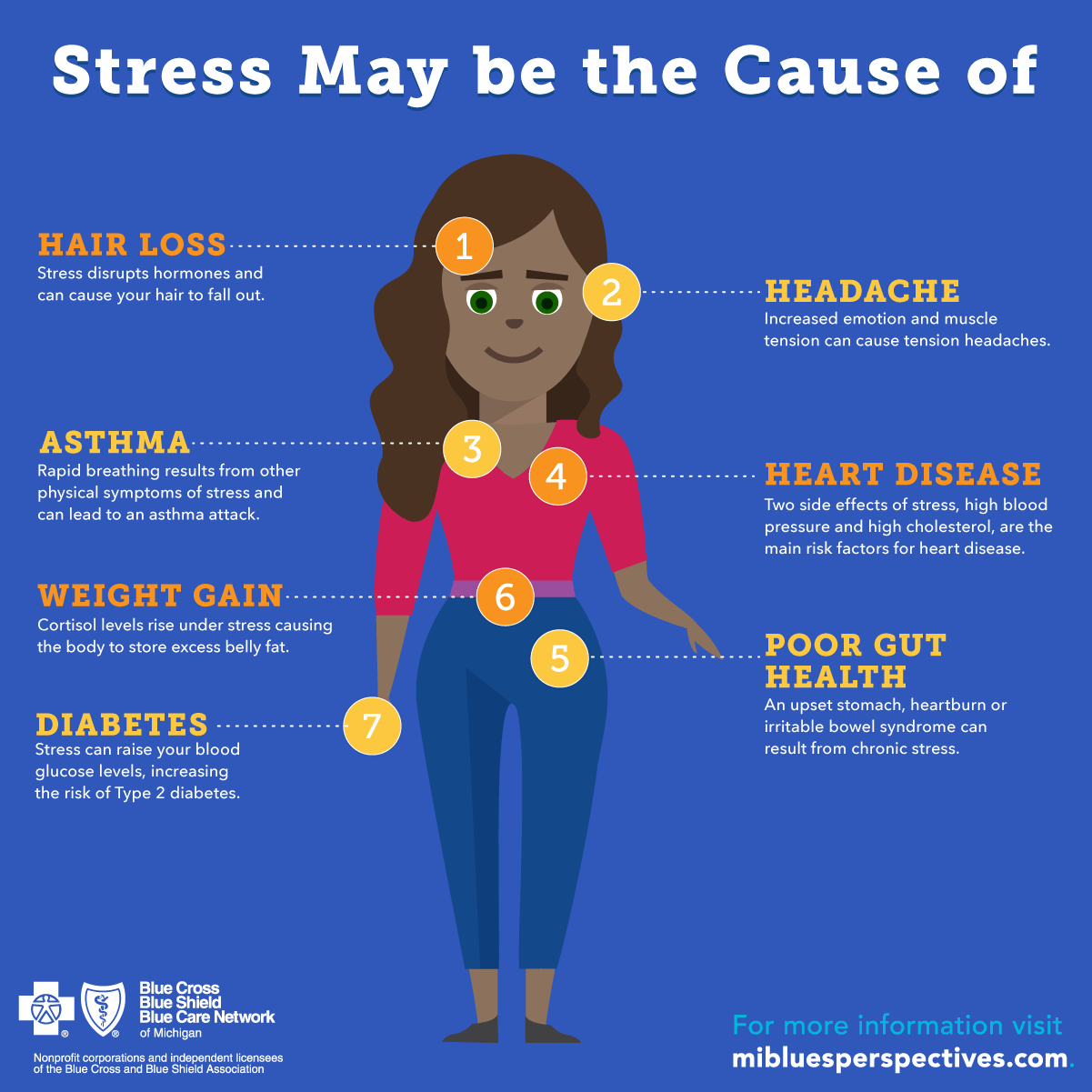

Empathy, after all, can be painful. An “empathy trap” occurs when we’re so focused on feeling what others are feeling that we neglect our own emotions and needs—and other people can take advantage of this. Doctors and caregivers are at particular risk of feeling emotionally overwhelmed by empathy.

In other cases, empathy seems to be detrimental. Empathizing with out-groups can make us more reluctant to engage with them, if we imagine that they’ll be critical of us. Sociopaths could use cognitive empathy to help them exploit or even torture people.

Even if we are well-intentioned, we tend to overestimate our empathic skills. We may think we know the whole story about other people when we’re actually making biased judgments—which can lead to misunderstandings and exacerbate prejudice.

Featured Articles

Six Habits of Highly Empathic People

If you think you’re hearing the word “empathy” everywhere, you’re right. It’s now on the lips of scientists and business leaders, education experts and political activists. But there is a vital question that few people ask: How can I expand my own empathic potential? Empathy is not just a way to extend the boundaries of your moral universe. According to new research, it’s a habit we can cultivate to improve the quality of our own lives.

But there is a vital question that few people ask: How can I expand my own empathic potential? Empathy is not just a way to extend the boundaries of your moral universe. According to new research, it’s a habit we can cultivate to improve the quality of our own lives.

But what is empathy? It’s the ability to step into the shoes of another person, aiming to understand their feelings and perspectives, and to use that understanding to guide our actions. That makes it different from kindness or pity. And don’t confuse it with the Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” As George Bernard Shaw pointed out, “Do not do unto others as you would have them do unto you—they might have different tastes.” Empathy is about discovering those tastes.

The big buzz about empathy stems from a revolutionary shift in the science of how we understand human nature. The old view that we are essentially self-interested creatures is being nudged firmly to one side by evidence that we are also homo empathicus, wired for empathy, social cooperation, and mutual aid.

Meet the Greater Good Toolkit

From the GGSC to your bookshelf: 30 science-backed tools for well-being.

Over the last decade, neuroscientists have identified a 10-section “empathy circuit” in our brains which, if damaged, can curtail our ability to understand what other people are feeling. Evolutionary biologists like Frans de Waal have shown that we are social animals who have naturally evolved to care for each other, just like our primate cousins. And psychologists have revealed that we are primed for empathy by strong attachment relationships in the first two years of life.

But empathy doesn’t stop developing in childhood. We can nurture its growth throughout our lives—and we can use it as a radical force for social transformation. Research in sociology, psychology, history—and my own studies of empathic personalities over the past 10 years—reveals how we can make empathy an attitude and a part of our daily lives, and thus improve the lives of everyone around us. Here are the Six Habits of Highly Empathic People!

Here are the Six Habits of Highly Empathic People!

Habit 1: Cultivate curiosity about strangers

Highly empathic people (HEPs) have an insatiable curiosity about strangers. They will talk to the person sitting next to them on the bus, having retained that natural inquisitiveness we all had as children, but which society is so good at beating out of us. They find other people more interesting than themselves but are not out to interrogate them, respecting the advice of the oral historian Studs Terkel: “Don’t be an examiner, be the interested inquirer.”

Curiosity expands our empathy when we talk to people outside our usual social circle, encountering lives and worldviews very different from our own. Curiosity is good for us too: Happiness guru Martin Seligman identifies it as a key character strength that can enhance life satisfaction. And it is a useful cure for the chronic loneliness afflicting around one in three Americans.

Cultivating curiosity requires more than having a brief chat about the weather. Crucially, it tries to understand the world inside the head of the other person. We are confronted by strangers every day, like the heavily tattooed woman who delivers your mail or the new employee who always eats his lunch alone. Set yourself the challenge of having a conversation with one stranger every week. All it requires is courage.

Crucially, it tries to understand the world inside the head of the other person. We are confronted by strangers every day, like the heavily tattooed woman who delivers your mail or the new employee who always eats his lunch alone. Set yourself the challenge of having a conversation with one stranger every week. All it requires is courage.

Habit 2: Challenge prejudices and discover commonalities

We all have assumptions about others and use collective labels—e.g., “Muslim fundamentalist,” “welfare mom”—that prevent us from appeciating their individuality. HEPs challenge their own preconceptions and prejudices by searching for what they share with people rather than what divides them. An episode from the history of US race relations illustrates how this can happen.

Claiborne Paul Ellis was born into a poor white family in Durham, North Carolina, in 1927. Finding it hard to make ends meet working in a garage and believing African Americans were the cause of all his troubles, he followed his father’s footsteps and joined the Ku Klux Klan, eventually rising to the top position of Exalted Cyclops of his local KKK branch.

In 1971 he was invited—as a prominent local citizen—to a 10-day community meeting to tackle racial tensions in schools, and was chosen to head a steering committee with Ann Atwater, a black activist he despised. But working with her exploded his prejudices about African Americans. He saw that she shared the same problems of poverty as his own. “I was beginning to look at a black person, shake hands with him, and see him as a human being,” he recalled of his experience on the committee. “It was almost like bein’ born again.” On the final night of the meeting, he stood in front of a thousand people and tore up his Klan membership card.

Ellis later became a labor organiser for a union whose membership was 70 percent African American. He and Ann remained friends for the rest of their lives. There may be no better example of the power of empathy to overcome hatred and change our minds.

Habit 3: Try another person’s life

So you think ice climbing and hang-gliding are extreme sports? Then you need to try experiential empathy, the most challenging—and potentially rewarding—of them all. HEPs expand their empathy by gaining direct experience of other people’s lives, putting into practice the Native American proverb, “Walk a mile in another man’s moccasins before you criticize him.”

HEPs expand their empathy by gaining direct experience of other people’s lives, putting into practice the Native American proverb, “Walk a mile in another man’s moccasins before you criticize him.”

George Orwell is an inspiring model. After several years as a colonial police officer in British Burma in the 1920s, Orwell returned to Britain determined to discover what life was like for those living on the social margins. “I wanted to submerge myself, to get right down among the oppressed,” he wrote. So he dressed up as a tramp with shabby shoes and coat, and lived on the streets of East London with beggars and vagabonds. The result, recorded in his book Down and Out in Paris and London, was a radical change in his beliefs, priorities, and relationships. He not only realized that homeless people are not “drunken scoundrels”—Orwell developed new friendships, shifted his views on inequality, and gathered some superb literary material. It was the greatest travel experience of his life. He realised that empathy doesn’t just make you good—it’s good for you, too.

He realised that empathy doesn’t just make you good—it’s good for you, too.

We can each conduct our own experiments. If you are religiously observant, try a “God Swap,” attending the services of faiths different from your own, including a meeting of Humanists. Or if you’re an atheist, try attending different churches! Spend your next vacation living and volunteering in a village in a developing country. Take the path favored by philosopher John Dewey, who said, “All genuine education comes about through experience.”

Habit 4: Listen hard—and open up

There are two traits required for being an empathic conversationalist.

One is to master the art of radical listening. “What is essential,” says Marshall Rosenberg, psychologist and founder of Non-Violent Communication (NVC), “is our ability to be present to what’s really going on within—to the unique feelings and needs a person is experiencing in that very moment.” HEPs listen hard to others and do all they can to grasp their emotional state and needs, whether it is a friend who has just been diagnosed with cancer or a spouse who is upset at them for working late yet again.

But listening is never enough. The second trait is to make ourselves vulnerable. Removing our masks and revealing our feelings to someone is vital for creating a strong empathic bond. Empathy is a two-way street that, at its best, is built upon mutual understanding—an exchange of our most important beliefs and experiences.

Organizations such as the Israeli-Palestinian Parents Circle put it all into practice by bringing together bereaved families from both sides of the conflict to meet, listen, and talk. Sharing stories about how their loved ones died enables families to realize that they share the same pain and the same blood, despite being on opposite sides of a political fence, and has helped to create one of the world’s most powerful grassroots peace-building movements.

Habit 5: Inspire mass action and social change

We typically assume empathy happens at the level of individuals, but HEPs understand that empathy can also be a mass phenomenon that brings about fundamental social change.

Just think of the movements against slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries on both sides of the Atlantic. As journalist Adam Hochschild reminds us, “The abolitionists placed their hope not in sacred texts but human empathy,” doing all they could to get people to understand the very real suffering on the plantations and slave ships. Equally, the international trade union movement grew out of empathy between industrial workers united by their shared exploitation. The overwhelming public response to the Asian tsunami of 2004 emerged from a sense of empathic concern for the victims, whose plight was dramatically beamed into our homes on shaky video footage.

Empathy will most likely flower on a collective scale if its seeds are planted in our children. That’s why HEPs support efforts such as Canada’s pioneering Roots of Empathy, the world’s most effective empathy teaching program, which has benefited over half a million school kids. Its unique curriculum centers on an infant, whose development children observe over time in order to learn emotional intelligence—and its results include significant declines in playground bullying and higher levels of academic achievement.

Beyond education, the big challenge is figuring out how social networking technology can harness the power of empathy to create mass political action. Twitter may have gotten people onto the streets for Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring, but can it convince us to care deeply about the suffering of distant strangers, whether they are drought-stricken farmers in Africa or future generations who will bear the brunt of our carbon-junkie lifestyles? This will only happen if social networks learn to spread not just information, but empathic connection.

Habit 6: Develop an ambitious imagination

A final trait of HEPs is that they do far more than empathize with the usual suspects. We tend to believe empathy should be reserved for those living on the social margins or who are suffering. This is necessary, but it is hardly enough.

We also need to empathize with people whose beliefs we don’t share or who may be “enemies” in some way. If you are a campaigner on global warming, for instance, it may be worth trying to step into the shoes of oil company executives—understanding their thinking and motivations—if you want to devise effective strategies to shift them towards developing renewable energy. A little of this “instrumental empathy” (sometimes known as “impact anthropology”) can go a long way.

Empathizing with adversaries is also a route to social tolerance. That was Gandhi’s thinking during the conflicts between Muslims and Hindus leading up to Indian independence in 1947, when he declared, “I am a Muslim! And a Hindu, and a Christian and a Jew.”

Organizations, too, should be ambitious with their empathic thinking. Bill Drayton, the renowned “father of social entrepreneurship,” believes that in an era of rapid technological change, mastering empathy is the key business survival skill because it underpins successful teamwork and leadership. His influential Ashoka Foundation has launched the Start Empathy initiative, which is taking its ideas to business leaders, politicians and educators worldwide.

His influential Ashoka Foundation has launched the Start Empathy initiative, which is taking its ideas to business leaders, politicians and educators worldwide.

The 20th century was the Age of Introspection, when self-help and therapy culture encouraged us to believe that the best way to understand who we are and how to live was to look inside ourselves. But it left us gazing at our own navels. The 21st century should become the Age of Empathy, when we discover ourselves not simply through self-reflection, but by becoming interested in the lives of others. We need empathy to create a new kind of revolution. Not an old-fashioned revolution built on new laws, institutions, or policies, but a radical revolution in human relationships.

What degree of empathy are you capable of - Citizen K - Kommersant

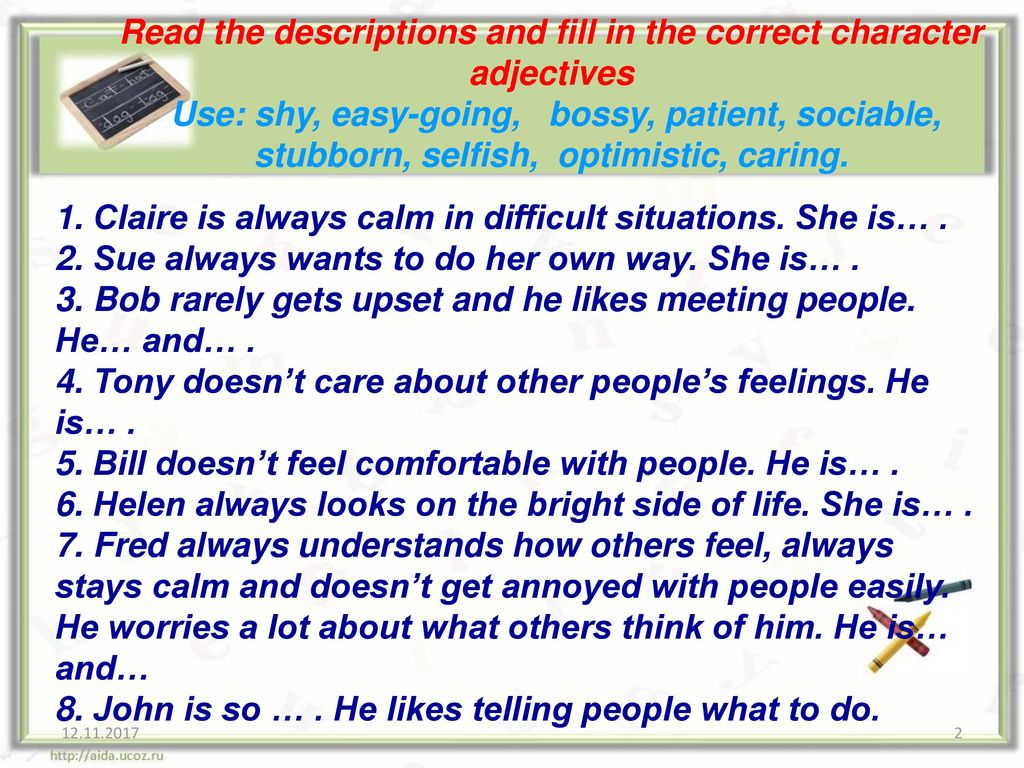

Below is a list of statements. You must give one of four answers to each question: strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree. It becomes clear pretty quickly which answer will bring you more points, so try to answer honestly.

You must give one of four answers to each question: strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree. It becomes clear pretty quickly which answer will bring you more points, so try to answer honestly.

| 1. | It is easy for me to start a conversation if someone wants to start it. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 2. | It seems difficult for me to explain something that I understand well if my explanation was not understood the first time. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 3. | I really enjoy taking care of people. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 4. | It's hard for me to figure out how to behave in a public place. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 5. | I am often told that I am too insistent on my point of view in conversations. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 6. | I don't worry too much if I'm late for a business or friendly meeting. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

7. | Friendships and romance are just too complicated for me, I don't get involved in such stories. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | strongly disagree |

| 8. | I often find it hard to tell if I am being rude or polite. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 9. | The subject of the conversation I will choose the things that interest me rather than those that could be interesting to the interlocutor. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

10. | As a child, I liked to cut worms and see what happens. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 11. | I can easily tell when someone doesn't say what they mean. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 12. | I find it hard to understand how certain things upset people so much. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 13. | It's easy for me to imagine myself in someone else's shoes. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 14. | I am very good with other people's feelings. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 15. | I easily single out those who feel uncomfortable or uncomfortable from a group of people. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 16. | If someone feels that what I say offends them, that is their problem, not mine. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

17. | If someone asks how I like his hairstyle, I will answer honestly, regardless of whether my answer will be pleasant to the asker. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 18. | I can't always understand why people feel offended by my words. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 19. | I can look at people crying and not get upset. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

20. | I am a very direct person, but people consider my frankness to be rude. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 21. | I am not embarrassed in public places. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 22. | People think that I understand well what they feel and think. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 23. | When I talk to people, I'm more interested in their opinion, not mine. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 24. | The sight of suffering animals upsets me. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 25. | I am able to make decisions without considering the feelings of others. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 26. | It is easy for me to recognize whether people are bored with me or interested. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

27. | I am saddened to hear of human suffering. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 28. | Friends usually tell me about their troubles - they think that I understand them. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 29. | I can feel when I'm being pushy, even if they don't tell me. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 30. | I am sometimes told that I tease people too much. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 31. | People often say I'm insensitive, and I usually don't understand why. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 32. | If I encounter strangers, I believe that they should take the first step towards getting to know each other. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 33. | Movies usually don't affect me emotionally. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

34. | I easily and quickly tune in to the feelings of others. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 35. | I usually understand what others mean. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | strongly disagree |

| 36. | I notice when someone hides their emotions. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 37. | I don't know much about accepted rules of conduct. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

38. | I have a good idea of what this or that person will do. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 39. | I am usually emotionally involved in my friends' troubles. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

| 40. | I tend to appreciate the other person's point of view, even if I don't agree with it. |

| totally agree | rather agree | rather disagree | totally disagree |

Sympathy. Why do we need sympathy, what is sympathy? When should you sympathize? Who do we sympathize with?

Empathy

Empathy is when I realize that I am experiencing about the same negative feelings as another person.

This feeling is not very pleasant, so I don't want to live it. But, I would like to be sympathized with if something unpleasant happens to me, which means that I should also be able to sympathize with other people.

I develop empathy by assessing the situation and the degree of its complexity, I try to put myself in the place of the person who is in it and feel what he feels.

In order not to live with other people's problems for a long time, I move away from sympathy, quickly transfer my attention to something else and try to forget about what happened.

I would like to share my feelings with others more often than bathe in them myself, and have more trust in my VS.

Sympathy

Sympathy is the experience of negative emotions that arose as a result of some event that did not happen to me. Sympathy is a kind of experience of what would happen to me in a given situation if I were in the place of the one with whom it really happened.

I don't want to have this feeling. Because it is unpleasant and darkens my life. Sometimes I can easily feign sympathy when it's the accepted norm to do so.

Because it is unpleasant and darkens my life. Sometimes I can easily feign sympathy when it's the accepted norm to do so.

I am very good at expressing my condolences and pretending to share the bitterness. But more often I try to avoid such situations, feel relieved that this did not happen to me and switch to other events.

Perhaps I will be more sincere if I do not show any false sympathy at all and confess that I do not feel any feelings. And if my sympathy is real, then I will be able not to plunge into this state for a long time.

Become the author of the project!

Dear participant of the Psycho Project No!

You can become the author of the project by making your invaluable contribution in the form of a publication about your experience of experiencing feelings.

Write a short (or long) story in the first person about how you feel most often.

When compiling the material, try to use questions for mini-speakers and a diagram about experiencing feelings.