Mindfulness of thoughts

A Meditation on Observing Thoughts, Non-Judgmentally

Transfuchsian/Adobe StockA Guided Meditation on Observing Thoughts

- 20:22

A Meditation on Observing Thoughts

- Take a few moments to settle into feeling the body as a whole, sitting and breathing, or lying down and breathing, riding the waves of the breath moment by moment, resting in awareness. An awareness that features the entirety of the body scape and the breath scape as they express themselves, moment by moment. Life unfolding here and now in the body, in awareness.

- And when you’re ready, if you care to, letting go of the breath and the body as a whole. Allowing them to recede into the background or rest in the wings, as we’ve been saying, still very much present but less featured while we invite the whole domain of thoughts and feelings and mood states to be center stage in the field of awareness.

- For a time attending to the stream of thought rather than being carried away by the content or emotional charge of individual thoughts, instead resting comfortably on the bank of the thoughts, river or the thought stream itself, allowing individual thoughts if and when they arise to be seen, felt, recognized and known, as thoughts as events in the field of awareness.

- Recognizing them as mental events, occurrences, secretions of the thinking mind, independent of their content and their emotional charge, even as that content and emotional charge are also seen and known.

- Seeing any and all of these fleeting thoughts as bubbles, eddies and currents within the stream, rather than as facts or as the truth of things, whatever the content, whatever the emotional charge, whatever their urgency or their tendency to reappear, whether they are pleasant or seductive, unpleasant or repulsive. Or neutral and therefore harder to detect at all.

- Expanding the metaphor, seeing any and all of these evanescent thought events more like clouds in the sky or bubbles coming off the bottom of a pot of boiling water. Or like writing on water, arising in a moment, lingering for the briefest of instances, and dissolving back into the formlessness from whence they came. Relating to their content as if it were of equal importance and relevance to say what you had for dinner three nights ago. Even if a thought is particularly compelling and insightful. Especially if it is particularly compelling and insightful.

- For now, just letting any and all thoughts come and go. Just let sounds come and go. Or sensations come and go. Not preferring some to others, nor pursuing some over others, not pursuing anything. Just resting in an awareness of thinking itself and the spaces between thoughts. Moment by moment, breath by breath, as we sit here or as we lie here.

- It might be helpful to be especially sensitive to the steady stream of commentary and advice you may be giving yourself as you sit here, and recognising it as such.

As scaffolding. As running commentary, taking a position in relationship to it that resembles turning down the sound on a television set, so that you’re just watching the game and aren’t being sucked into the endless stream of commentary and interpretation and opinion that is so characteristic of televised sports events.

As scaffolding. As running commentary, taking a position in relationship to it that resembles turning down the sound on a television set, so that you’re just watching the game and aren’t being sucked into the endless stream of commentary and interpretation and opinion that is so characteristic of televised sports events. - Rather, you now detect the individual secretions of commentary on your moment to moment experience merely is more thinking as thoughts,, as judgments and rest in the recognizing of them in the economists attending to each event as it arises in the stream without being pulled into the past or into the future or into opinions or fears or desires, simply seeing them and knowing them as thoughts and as emotions as mental events, not as the truth and not as you watching them proliferate endlessly as they do watching the mind secrete them and throw them off.

- Watching how easily thoughts manufacture or fabricate views, opinions, ideas, beliefs, plans, memories, stories, and how easily they proliferate.

If we feed them the one thought morphing into the next, then into the next, until we suddenly realize that we’ve been carried downstream and are no longer aware of the stream itself. The process of thinking and how in the noticing we are already back in the frame of attending to thinking, is thinking to thoughts, thoughts observing them, recognizing them, perhaps being carried away again.

If we feed them the one thought morphing into the next, then into the next, until we suddenly realize that we’ve been carried downstream and are no longer aware of the stream itself. The process of thinking and how in the noticing we are already back in the frame of attending to thinking, is thinking to thoughts, thoughts observing them, recognizing them, perhaps being carried away again. - And if so over and over again coming back to this moment to this frame in this moment to the field of thought itself beyond all the content of the endless thinking and proliferating and fabricating and the emotions that accompany them springing from whether they are pleasant unpleasant or neutral and from what’s going on in your life in this moment.

- Allowing all of this to be held to bare attention in awareness moment on breath by breath as we sit here or live here resting in the awareness itself south taking up residence in awareness itself in the knowing of thoughts thoughts and feelings as feelings in the accepting of thoughts thoughts and feelings feelings whatever their content whatever their emotional charge just as an experiment in cultivating greater intimacy with your own interiority with what’s on your mind and in your heart.

And with new dimensions of the possible.

And with new dimensions of the possible. - If we learn to observe carefully rather than identifying with the content of thoughts and feelings to see them more impersonally as weather patterns as ripples and waves on the surface of the vast and deep ocean of the mind. As we inhabit the whole of the mind that boundless essence of mine that already knows before I thought underneath thought beyond thought that is bigger than thought. Bigger than any feeling however powerful that is capable of making use of thought and emotion without being caught and imprisoned by unwise and unexamined habit patterns developed over a lifetime of ignoring these aspects of the mindscape of the landscape of our own being of our lives unfolding.

- So for the remainder of our time together, until you hear the sound of the bells resting in an awareness of the arising and passing away of thoughts and feelings in the mindscape some overwhelmingly obvious, some quite subtle, some masquerading as commentary, others as scaffolding, others as neither, and simply returning over and over again to the frame, whenever the mind is carried off, not looking for thoughts or emotions or mood indicators, just resting in awareness and letting the mall come to you.

- Letting them arise on their own in the field of awareness to whatever degree they do. Moment by moment by moment, and breath by breath, as you sit here or as you live your life.

Adapted from Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Guided Mindfulness Meditation Series 3, available here. These guided meditations are designed to accompany Jon Kabat-Zinn’s book Meditation is Not What You Think and the other three volumes based on Coming to Our Senses.

Less stress, clearer thoughts with mindfulness meditation – Harvard Gazette

Those who learn its techniques often say they feel less stress, think clearer

By Liz Mineo Harvard Staff Writer

Date

Second of two parts

On a cold winter evening, six women and two men sat in silence in an office near Harvard Square, practicing mindfulness meditation.

Sitting upright, eyes closed, palms resting on their laps, feet flat on the floor, they listened as course instructor Suzanne Westbrook guided them to focus on the present by paying attention to their bodily sensations, thoughts, emotions, and especially their breath.

“Our mind wanders all the time, either reviewing the past or planning for the future,” said Westbrook, who before retiring last June was an internal-medicine doctor caring for Harvard students. “Mindfulness teaches you the skill of paying attention to the present by noticing when your mind wanders off. Come back to your breath. It’s a place where we can rest and settle our minds.”

The class she taught was part of an eight-week program aimed at reducing stress.

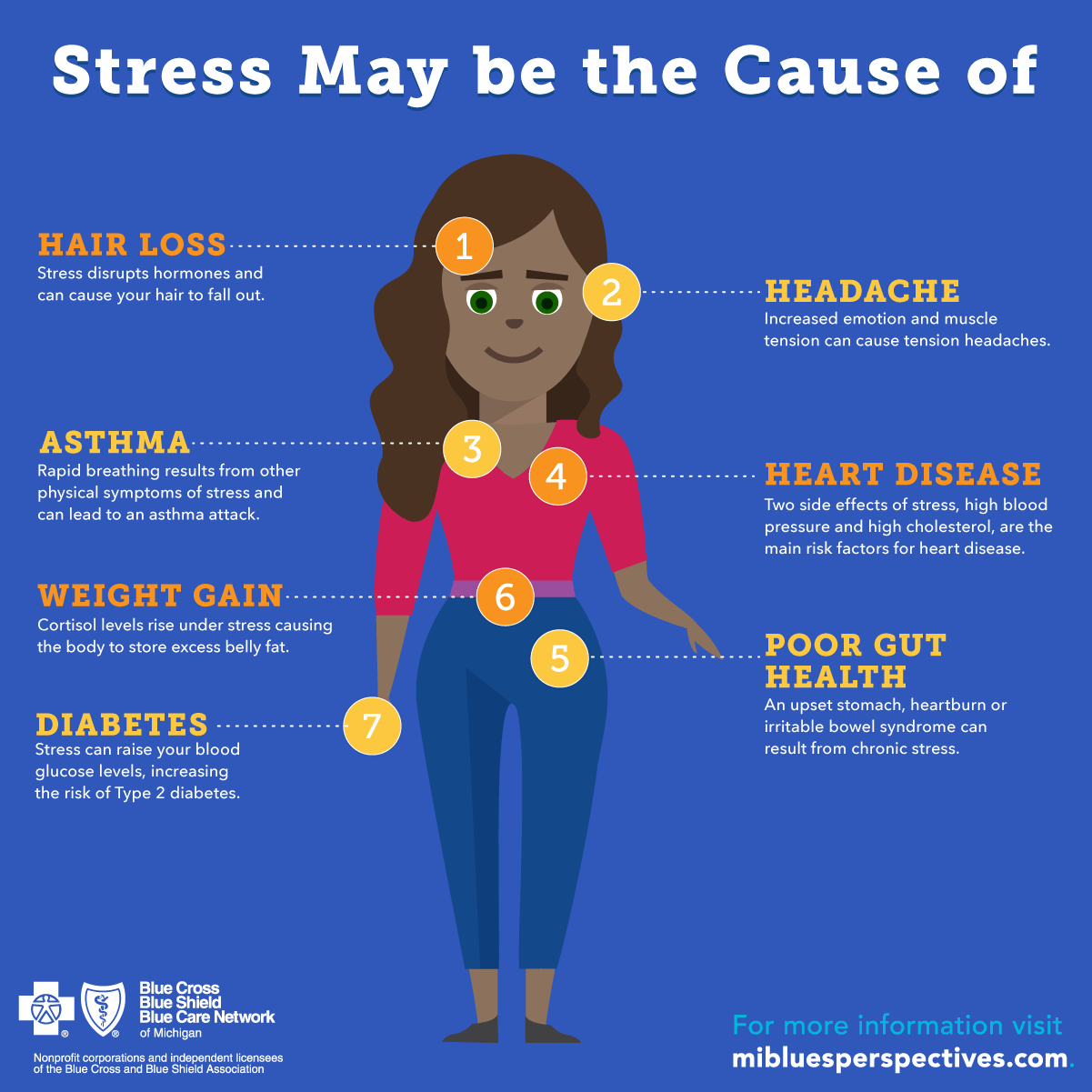

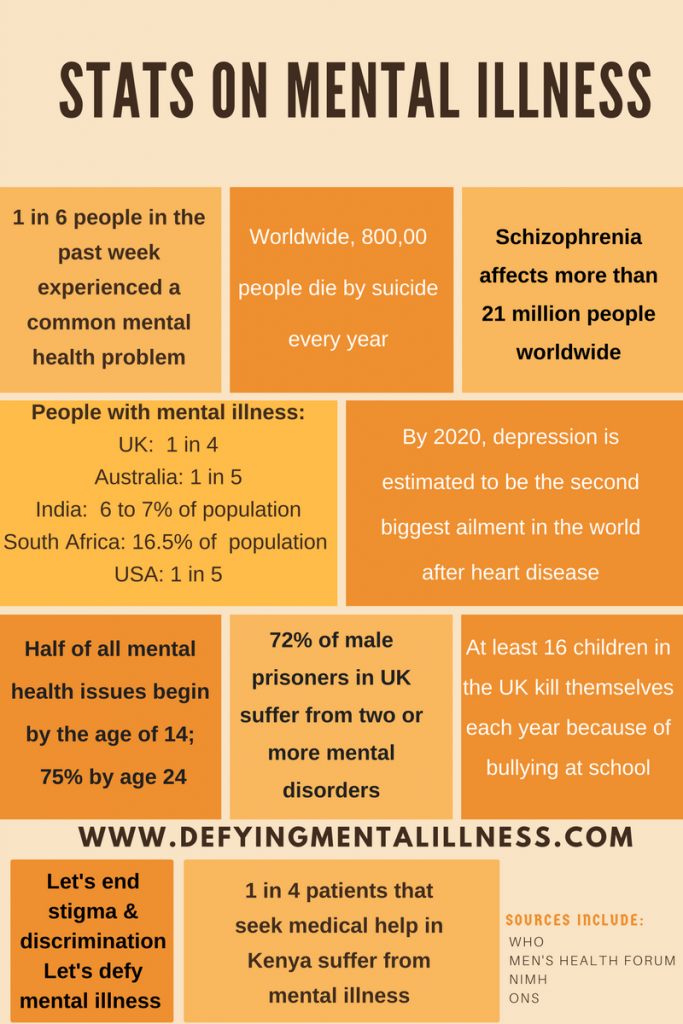

Studies say that eight in 10 Americans experience stress in their daily lives and have a hard time relaxing their bodies and calming their minds, which puts them at high risk of heart disease, stroke, and other illnesses. Of the myriad offerings aimed at fighting stress, from exercise to yoga to meditation, mindfulness meditation has become the hottest commodity in the wellness universe.

Modeled after the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program created in 1979 by Jon Kabat-Zinn to help counter stress, chronic pain, and other ailments, mindfulness courses these days can be found in venues ranging from schools to prisons to sports teams. Even the U.S. Army recently adopted it to “improve military resilience.”

Harvard offers several mindfulness and meditation classes, including a spring break retreat held in March for students through the Center for Wellness and Health Promotion. The Office of Work/Life offers programs to managers and staff, as well as weekly drop-in meditation sessions on campus, online guided meditation resources, and even a meditation phone line, 4-CALM (at 617.384.2256).

“We were tasked to find ways for the community to cope with stress. And at the same time, so much research was coming out on the benefits of mindfulness and meditation,” said Jeanne Mahon, director of the wellness center. “We keep offering mindfulness and meditation because of the feedback. People appreciate to have the chance for self-reflection and learn about new ways to be in relationships with themselves.”

“We keep offering mindfulness and meditation because of the feedback. People appreciate to have the chance for self-reflection and learn about new ways to be in relationships with themselves.”

More than 750 students have participated in mindfulness and meditation programs since 2012, said Mahon.

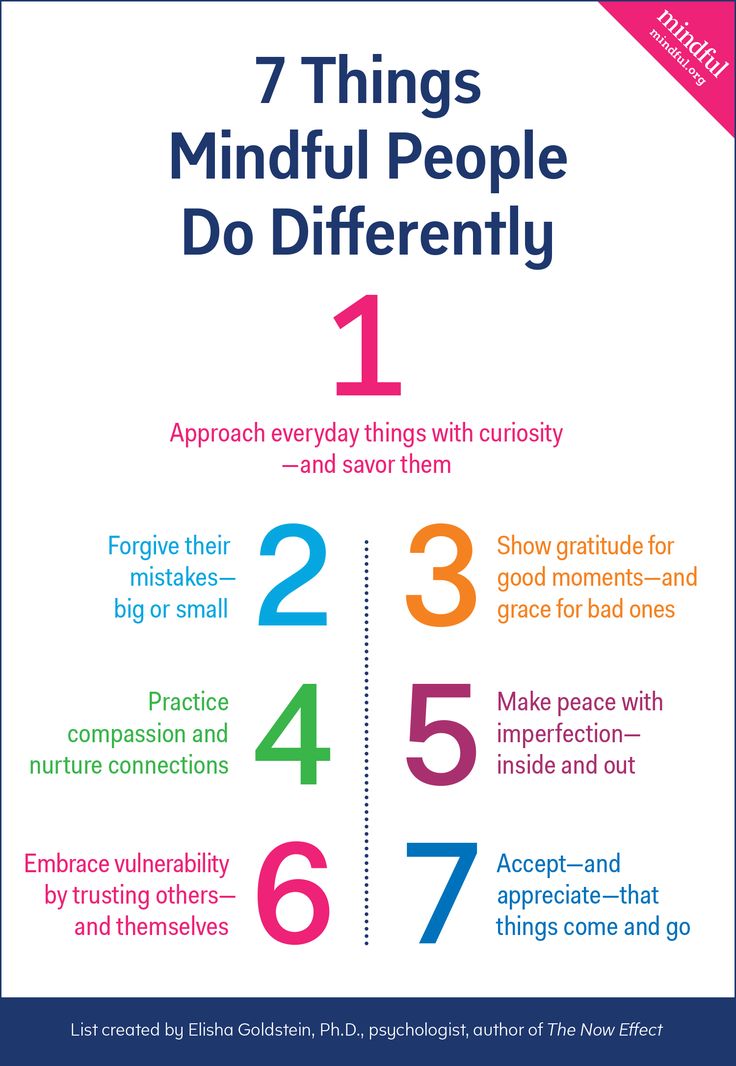

Part of mindfulness’ appeal lies in the fact that it’s secular. Buddhist monks have used mindfulness exercises as forms of meditation for more than 2,600 years, seeing them as one of the paths to enlightenment. But in the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program, mindfulness is stripped of religious undertones.

Mark Dennis (from left), Kelly Romirowsky, and Ayesha Hood practice meditation. Metta McGarvey (not pictured) teaches the practice of mindfulness, a workshop for educators inside the Gutman Conference Center.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer.

Mindfulness’ popularity has been bolstered by a growing body of research showing that it reduces stress and anxiety, improves attention and memory, and promotes self-regulation and empathy. A few years ago, a study by Sara Lazar, a neuroscientist and assistant professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and assistant researcher in psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, was the first to document that mindfulness meditation can change the brain’s gray matter and brain regions linked with memory, the sense of self, and regulation of emotions. New research by Benjamin Shapero and Gaëlle Desbordes is exploring how mindfulness can help depression.

A few years ago, a study by Sara Lazar, a neuroscientist and assistant professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and assistant researcher in psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, was the first to document that mindfulness meditation can change the brain’s gray matter and brain regions linked with memory, the sense of self, and regulation of emotions. New research by Benjamin Shapero and Gaëlle Desbordes is exploring how mindfulness can help depression.

The pioneer of scientific research on meditation, Herbert Benson, extolled its benefits on the human body — reduced blood pressure, heart rate, and brain activity — as early as 1975. He helped demystify meditation by calling it the “relaxation response.” Benson is director emeritus of the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and Mind/Body Medicine Distinguished Professor of Medicine at HMS.

In the 1980s, mindfulness had yet to become a buzzword, recalls Paul Fulton, a clinical psychologist who has practiced Zen and insight meditation (vipassana) for more than 40 years. In the mid-1980s, when he was working on his doctoral dissertation on the nature of “self” among Buddhist monks, speaking of mindfulness in a medical context among scientists was “disreputable,” he recalled.

In the mid-1980s, when he was working on his doctoral dissertation on the nature of “self” among Buddhist monks, speaking of mindfulness in a medical context among scientists was “disreputable,” he recalled.

“Gradually because of the research, it became chic, no longer disreputable,” said Fulton, a lecturer in psychology in the Department of Psychiatry at HMS and co-founder of the Institute for Meditation and Psychotherapy. “And now you can’t step a foot out of the house without being barraged by mindfulness.”

Melanie Denham, head coach of Harvard women’s rugby team, recently attended a mindfulness workshop, intrigued by the idea of incorporating the techniques into her players’ training regimen to help them cope with the pressures of “expectation and performance.”

“In and out of the classroom, these student-athletes are immersed in a highly competitive culture,” said Denham. “This is stressful. This kind of training can develop a more-skillful mind and a sense of focus and well-being that can help them better maintain control and awareness of their thoughts, emotions, and presence in the moment.”

“This is stressful. This kind of training can develop a more-skillful mind and a sense of focus and well-being that can help them better maintain control and awareness of their thoughts, emotions, and presence in the moment.”

The growing interest in the field is reflected in Harvard’s course catalog. This spring, Lazar is teaching “Cognitive Neuroscience of Meditation,” Ezer Vierba leads an expository freshmen writing course on “Buddhism, Mindfulness, and the Practical Mind,” and Metta McGarvey teaches “Mindfulness for Educators” at the Graduate School of Education.

Due to high demand, McGarvey, who holds a doctorate in human development and psychology, teaches a three-day workshop for educators. It offers tools to enhance their work and their focus through breathing practices and self-compassion exercises.

Mindfulness meditation made easy

-

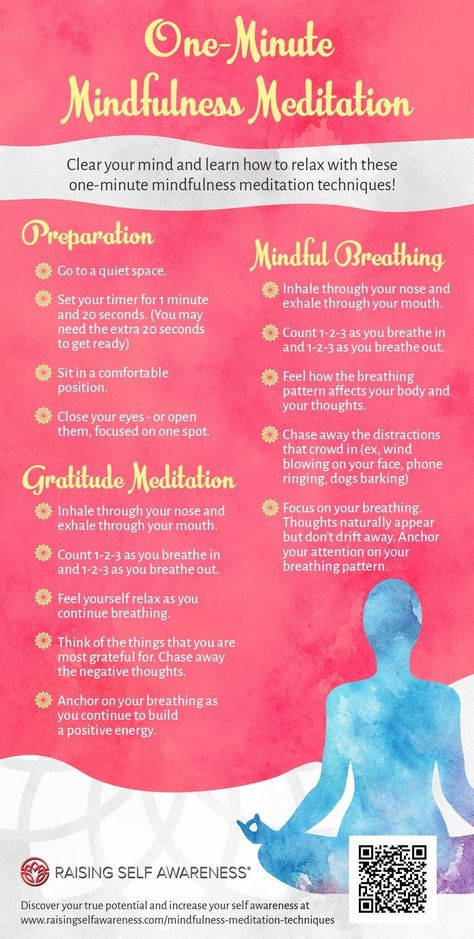

Settle in

Find a quiet space. Using a cushion or chair, sit up straight but not stiff; allow your head and shoulders to rest comfortably; place your hands on the tops of your legs with upper arms at your side.

-

Now breathe

Close your eyes, take a deep breath, and relax. Feel the fall and rise of your chest and the expansion and contraction of your belly. With each breath notice the coolness as it enters and the warmth as it exits. Don't control the breath but follow its natural flow.

-

Stay focused

Thoughts will try to pull your attention away from the breath. Notice them, but don't pass judgment. Gently return your focus to your breath. Some people count their breaths as a way to stay focused.

-

Take 10

A daily practice will provide the most benefits. It can be 10 minutes per day, however, 20 minutes twice a day is often recommended for maximum benefit.

“A lot of them are working in really tough environments, with all kinds of pressures,” said McGarvey. “The rates of burnout in some of the more challenging environments are very high. ”

”

Ayesha Hood, a police officer from Baltimore who is interested in running a day care center, attended McGarvey’s workshop last fall, and found it helpful. “As a police officer, I live in high stress, and as a public servant, I tend to neglect myself,” she said. “I want to calm myself and be conscious about it.”

Christine O’Shaughnessy, a former investment bank executive who lead workshops at Harvard, said, “All day we’re bombarded with social media, colleagues, work, children, etc. We don’t have time to spend it in quiet reflection. But if you practice it at least once a day, you’ll have a better day.”

To skeptics who still view mindfulness as hippie-dippy poppycock, O’Shaughnessy has four words: “Give it a try.” When she first signed up for a mindfulness workshop in 1999, she said she was skeptical too. But once she realized she was becoming calmer and less stressed, she converted. She eventually quit her job and became a mindfulness instructor. (She recently launched a free meditation app. )

)

“Doing mindfulness is like a fitness routine for your brain,” she said. “It keeps your brain healthy.”

Metta McGarvey teaches the practice of mindfulness, a workshop for educators inside the Gutman Conference Center.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Mindfulness practitioners admit the practice can offer challenges. It requires consistency because its effects can be better felt over time, and discipline to train the wandering mind to keep coming back to the present, without judgment. A 2014 study said that many people would rather apply electroshocks to themselves than be alone with their thoughts. Another study showed that most people find it hard to focus on the present and that the mind’s wandering can lead to stress and even suffering.

Related

Researchers study how it seems to change the brain in depressed patients

Using meditation techniques in classrooms can boost clarity and learning, Kabat-Zinn says

Mindfulness meditation programs help students decompress

Meditation study shows changes associated with awareness, stress

Despite the rising acceptance of mindfulness, many people still think the practice involves emptying their minds, taking mini-naps, or going into trances. Beginners often fall asleep, feel uncomfortable, struggle with difficult thoughts or emotions, and become bored or distracted. Adepts recommend practicing the process in a group with an instructor.

Beginners often fall asleep, feel uncomfortable, struggle with difficult thoughts or emotions, and become bored or distracted. Adepts recommend practicing the process in a group with an instructor.

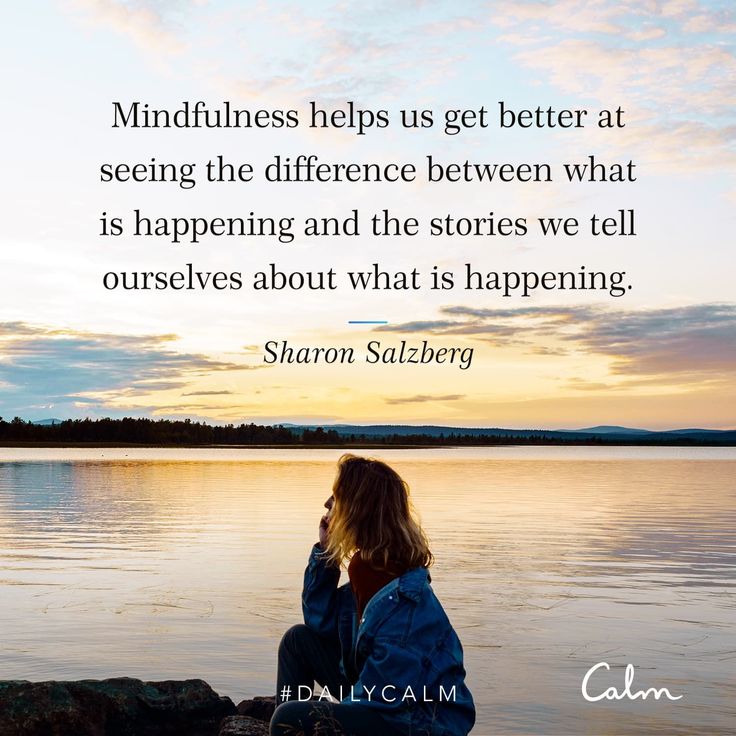

After the training session led by Westbrook, one participant said she couldn’t stop thinking about what was for dinner during the meditation practice; others nodded in agreement. Westbrook reassured her, saying that mindfulness is not about stopping thoughts or emotions, but instead about noticing them without judgment. Mindfulness builds resilience and awareness to help people learn how to ride life’s ups and downs and live happier and healthier lives, said Westbrook, who, after helping heal the bodies of thousands of patients in 36 years as a doctor, plans to devote her second career to caring for people’s spirits and souls, maybe as a chaplain.

“Mindfulness is not about being positive all the time or a bubblegum sort of happiness — la, la, la,” she said. “It’s about noticing what happens moment to moment, the easy and the difficult, and the painful and the joyful. It’s about building a muscle to be present and awake in your life.”

It’s about building a muscle to be present and awake in your life.”

For more information about the Mindfulness & Meditation program at Harvard University, visit its website. For a list of spring courses for Harvard faculty and staff, visit the Mindfulness at Work Program website.

how to learn to live life to the fullest - T&P

In the hustle and bustle of everyday life, we often lack the focus to become aware of all our experiences and truly understand what we want. Alpina Non-Fiction has published Andy Puddicombe's book Meditation and Mindfulness, in which the author explains how not to lose yourself in the endless streams of information and momentary emotions. "Theories and Practices" publishes an excerpt from the book.

Andy Puddicombe

Alpina Digital Publishing, 2011

Although mindfulness requires constant effort, it, like meditation, requires a special kind of effort, natural and effortless. It is only necessary to notice every time when thoughts or feelings force you to distract from reality, and at the same moment redirect your attention to where it is required. Whether you're focused on the taste of the food you're eating, the movement of your hands opening or closing the door, the weight of your body in a chair, the feel of the water washing over your skin in the shower, skin-to-skin contact with your baby, the smell of toothpaste while brushing your teeth, or just a glass of water that you are now drinking. Mindfulness applies to any little thing that is given to you in sensation, without a single exception. It does not matter whether it is active and non-physical activities, whether you indulge in them at home or on the street, at work or during leisure time, alone or in company. If you are just starting to understand the idea of engagement, all of this can be confusing at first.

It is only necessary to notice every time when thoughts or feelings force you to distract from reality, and at the same moment redirect your attention to where it is required. Whether you're focused on the taste of the food you're eating, the movement of your hands opening or closing the door, the weight of your body in a chair, the feel of the water washing over your skin in the shower, skin-to-skin contact with your baby, the smell of toothpaste while brushing your teeth, or just a glass of water that you are now drinking. Mindfulness applies to any little thing that is given to you in sensation, without a single exception. It does not matter whether it is active and non-physical activities, whether you indulge in them at home or on the street, at work or during leisure time, alone or in company. If you are just starting to understand the idea of engagement, all of this can be confusing at first.

People regularly ask me if they should now walk down the street with their eyes closed, focusing on their own breathing. No, please don't do this! So you can easily get under the car. Also, this is about general awareness, not about a specific process of meditation, so you should not close your eyes and focus on your breath. Remember: engagement means being fully aware of the current moment, understanding where you are and what you are doing. You will behave exactly the same as usual. All you have to do is stay on all the time, and the easiest way to do this is to choose a specific object and focus on it.

No, please don't do this! So you can easily get under the car. Also, this is about general awareness, not about a specific process of meditation, so you should not close your eyes and focus on your breath. Remember: engagement means being fully aware of the current moment, understanding where you are and what you are doing. You will behave exactly the same as usual. All you have to do is stay on all the time, and the easiest way to do this is to choose a specific object and focus on it.

Every time you realize that you have forgotten about him, you simply return your thoughts to the object of your attention. One of my favorite examples is brushing your teeth. This action is familiar to everyone, it lasts no more than two minutes, while without explanation it is clear what exactly you are focusing on, and with a high probability you will be able to complete this process while remaining involved. And this will be a big difference from the usual way for most people to carry out this simple hygienic procedure - on full automatic, thinking about what to do next.

To fully understand the difference between the two scenarios, it must be experienced. Try what it is. Perhaps you can easily focus on physical sensations, turning them into a focal point. It can be the sound of a brush scraping over the teeth, the sensations that the steady movement back and forth causes in the hand, the taste or smell of toothpaste. If you focus on one single sensation, your mind will feel calmer. And when you calm down, you may well notice a habit of being distracted by an extraneous thought or jumping from one thought to another. Maybe you notice that you spend too much or, on the contrary, too little effort directly on the procedure of brushing your teeth. There is a chance that you will even register a feeling of boredom. All these observations are useful in their own way, because they allow you to see your own consciousness as it really is. This concentration reflects the difference between a stable, calm mind and a mind that is out of control. Let's look at an example. Suppose you are about to drink a glass of water. Instead of gulping down water, try focusing on the experience you get. Seriously, when was the last time you tasted the water you drink? As soon as you take a glass in your hands, you get information about the temperature of the water and the material from which the glass is made. You can pay close attention to how the hand moves towards the mouth, to the taste of water filling the mouth. By learning to listen to your feelings, you will be able to follow how water moves through the throat and further into the stomach. If at some stage you notice that your mind wanders somewhere far away, just refocus your attention on how you drink.

Suppose you are about to drink a glass of water. Instead of gulping down water, try focusing on the experience you get. Seriously, when was the last time you tasted the water you drink? As soon as you take a glass in your hands, you get information about the temperature of the water and the material from which the glass is made. You can pay close attention to how the hand moves towards the mouth, to the taste of water filling the mouth. By learning to listen to your feelings, you will be able to follow how water moves through the throat and further into the stomach. If at some stage you notice that your mind wanders somewhere far away, just refocus your attention on how you drink.

“Imagine what it would be like to be around someone who could give you their full attention.”

As you practice this approach in various situations, you will find that it is effective in calming the mind. Not only are you fully aware of the impressions you receive at any particular moment, you live life to the fullest in the full sense of the word, but you also calm down. And with peace comes clarity. You begin to understand how and why you think and feel, and why it happens the way you do. You begin to notice patterns and trends that are characteristic of your consciousness. As a result, you again get the opportunity to independently decide how to live. Instead of being mindlessly carried away by destructive, unproductive thoughts and emotions, you can respond to what is happening in the way that feels best to you.

And with peace comes clarity. You begin to understand how and why you think and feel, and why it happens the way you do. You begin to notice patterns and trends that are characteristic of your consciousness. As a result, you again get the opportunity to independently decide how to live. Instead of being mindlessly carried away by destructive, unproductive thoughts and emotions, you can respond to what is happening in the way that feels best to you.

Another popular question is how does this technique work in the presence of strangers? Wouldn't such concentration in the company of other people look like rudeness? These fears seem ridiculous to me: after all, such a question suggests that we are usually so focused on the words, feelings and emotions of others that we are not enough for anything else. You know, in reality, this is extremely rare. More often than not, we are so immersed in our own thoughts that we are not able to really hear the words of the interlocutor. Suppose you are walking down the street chatting with a friend. In principle, walking is an autonomous activity, and yet you spend some of your attention on not colliding with other passers-by, not accidentally entering the roadway, and so on. Only in those moments when you are not busy with relevant observations, you can switch your attention to communication with a friend. This, however, does not mean at all that you pay less attention to the interlocutor than usual - it simply means that you switch from one object to another with the necessary frequency, in this case from the environment to a conversation with a friend. In such a situation, your attention to your own thoughts and feelings will not be as complete as if you were sitting and meditating alone - at least at first, but the main thing is the firm intention to remain involved. The more often you practice, the easier it will be for you to practice and the more successful you will be able to keep your attention.

In principle, walking is an autonomous activity, and yet you spend some of your attention on not colliding with other passers-by, not accidentally entering the roadway, and so on. Only in those moments when you are not busy with relevant observations, you can switch your attention to communication with a friend. This, however, does not mean at all that you pay less attention to the interlocutor than usual - it simply means that you switch from one object to another with the necessary frequency, in this case from the environment to a conversation with a friend. In such a situation, your attention to your own thoughts and feelings will not be as complete as if you were sitting and meditating alone - at least at first, but the main thing is the firm intention to remain involved. The more often you practice, the easier it will be for you to practice and the more successful you will be able to keep your attention.

Involvement in the present will allow you to fully remain "in the same room" with the interlocutor. One woman who came to my clinic told me how she uses this method to contact a child and how it helps her to truly be with him. According to her, although she had been close to the baby in the same way before, her thoughts wandered somewhere all the time. Only when she learned to really feel involved in communication with the child did she realize the fullness of their interaction. Experiences like these can have a truly limitless impact on our interactions with others. Imagine what it's like to be next to a person who can give you all his attention without a trace, and how nice it will be to give him the same undivided attention in return.

One woman who came to my clinic told me how she uses this method to contact a child and how it helps her to truly be with him. According to her, although she had been close to the baby in the same way before, her thoughts wandered somewhere all the time. Only when she learned to really feel involved in communication with the child did she realize the fullness of their interaction. Experiences like these can have a truly limitless impact on our interactions with others. Imagine what it's like to be next to a person who can give you all his attention without a trace, and how nice it will be to give him the same undivided attention in return.

The beauty of mindfulness is that you don't have to spend extra time on it. You just have to learn to fully immerse yourself in the action that is being performed in the present, instead of wandering somewhere in an unknown distance. This is an answer to those who claim that they do not have free time to train their consciousness. A long time ago, I was told a story about an American meditation teacher who was studying as a monk in Thailand. He went there in the 1960s and 1970s, along with many others who were then following the hippie paths to Asia. During his wanderings, he became interested in meditation and decided that he was ready to spend all his time studying. After going to one of the most famous teachers in Thailand, he settled in a monastery and began his studies, eventually becoming a monk. His study schedule was very tight: he had to devote his time exclusively to studies and work. At the same time, meditation classes took about eight hours a day.

He went there in the 1960s and 1970s, along with many others who were then following the hippie paths to Asia. During his wanderings, he became interested in meditation and decided that he was ready to spend all his time studying. After going to one of the most famous teachers in Thailand, he settled in a monastery and began his studies, eventually becoming a monk. His study schedule was very tight: he had to devote his time exclusively to studies and work. At the same time, meditation classes took about eight hours a day.

If you have never lived in a monastery, eight hours may seem like a long time. However, in such places they fly by in the blink of an eye. Of course, students also devote the remaining time to the training of consciousness - in the form of awareness of the present and the application of engagement to everyday affairs.

As this Asian travel route gradually gained in popularity, the monastery was visited by numerous Western tourists during this man's training. Some of them stayed there for several weeks and then continued on their way. Living in the monastery, they, of course, constantly entered into conversations with representatives of Western countries who lived there. In the course of such conversations, our monk learned that in neighboring Burma there are monasteries, the inhabitants of which devote about 18 hours a day to meditation. Enthusiastic and dreaming of making progress in the study of meditation as soon as possible, he began to seriously consider moving. But he could not overcome his doubts in any way: after all, the teacher who taught him was very famous and respected. For several months he suffered, unable to decide whether to leave or stay. He believed that he would achieve enlightenment more quickly by meditating for 18 hours a day in one of the Burmese monasteries. Indeed, in his monastery, he was constantly busy with work - he was engaged in cleaning, collecting firewood for kindling, darning monastic robes, and so on; it seemed to him that after all this he had practically no time left for meditation.

Some of them stayed there for several weeks and then continued on their way. Living in the monastery, they, of course, constantly entered into conversations with representatives of Western countries who lived there. In the course of such conversations, our monk learned that in neighboring Burma there are monasteries, the inhabitants of which devote about 18 hours a day to meditation. Enthusiastic and dreaming of making progress in the study of meditation as soon as possible, he began to seriously consider moving. But he could not overcome his doubts in any way: after all, the teacher who taught him was very famous and respected. For several months he suffered, unable to decide whether to leave or stay. He believed that he would achieve enlightenment more quickly by meditating for 18 hours a day in one of the Burmese monasteries. Indeed, in his monastery, he was constantly busy with work - he was engaged in cleaning, collecting firewood for kindling, darning monastic robes, and so on; it seemed to him that after all this he had practically no time left for meditation. In addition, he found school difficult, and he suspected that work was somehow interfering with his studies. In the end, he went to the teacher to warn him about his impending departure. He secretly hoped that, seeing his enthusiasm and enthusiasm, the teacher would give him the opportunity to stay and devote more time to meditation. However, when he heard it, he just nodded calmly.

In addition, he found school difficult, and he suspected that work was somehow interfering with his studies. In the end, he went to the teacher to warn him about his impending departure. He secretly hoped that, seeing his enthusiasm and enthusiasm, the teacher would give him the opportunity to stay and devote more time to meditation. However, when he heard it, he just nodded calmly.

“Each of us has 24 hours a day at our disposal, that is, the same amount of time that we can use in learning to consciously relate to reality”

The seeming indifference of the teacher angered our enthusiast. He sincerely did not understand what was happening. “Don’t you even want to know why I’m leaving?! he exclaimed.

“Okay, tell me,” the teacher replied, still indifferent.

— Because we don't have time to meditate here! the monk exclaimed. — In Burma, monks meditate 18 hours a day, while we only do eight. How can I make progress in my studies if all I do all day long is cook, clean and darn? We don't have time for anything else here!

It is said that the teacher looked at him attentively, but he asked the question with a smile.

— Do you think that you do not have time to be aware of what is happening? - he asked. “Do you think you don’t have enough time to understand?”

The student, immersed in an internal dialogue, at first did not even understand what he was talking about, and answered with irritation: — Of course. We are so busy with work that we have no time to be aware of the present.

The teacher laughed.

“So,” he said, “when you are sweeping the yard, you are not able to be aware of the process of sweeping? When you iron monastic robes, can't you give yourself over to the process of ironing? The meaning of mind training is awareness. You can be aware of what is happening with the same success when you sit with your eyes closed in the temple, as when you sweep the yard and your eyes are open at the same time!

The student fell silent, realizing how far his understanding of consciousness training was from the truth. Like many others, including myself, he believed that you can work on your consciousness only when you sit quietly and meditate. In practice, however, this process is much more diverse. The practice of mindfulness teaches us that we can use the same faculties of our mind in whatever we do. It doesn’t matter if we are engaged in manual labor or lead a sedentary lifestyle, engagement can be practiced just as well while riding a bicycle as sitting at home in an armchair. It doesn't matter what business we're in. Each of us has at our disposal 24 hours a day, that is, the same amount of time that we can use in learning to be conscious of reality. It doesn't matter if we are aware of physical sensations, emotions, thoughts, or their content - they are all different facets of awareness, for which we always have time.

In practice, however, this process is much more diverse. The practice of mindfulness teaches us that we can use the same faculties of our mind in whatever we do. It doesn’t matter if we are engaged in manual labor or lead a sedentary lifestyle, engagement can be practiced just as well while riding a bicycle as sitting at home in an armchair. It doesn't matter what business we're in. Each of us has at our disposal 24 hours a day, that is, the same amount of time that we can use in learning to be conscious of reality. It doesn't matter if we are aware of physical sensations, emotions, thoughts, or their content - they are all different facets of awareness, for which we always have time.

Do you remember how you used to draw in elementary school by connecting a series of dots? Remember those pictures where the image was marked with a whole row of little dots? Usually they were so close to each other that you only had to draw a line on paper, eventually getting the feeling that you created your own, personal masterpiece. This dotted picture is a clear illustration of how engagement can become more than just a once-a-day meditative exercise. Take a blank sheet of paper and try to draw a straight line across the entire sheet. I think even if you have an excellent eye, your hand will still tremble a couple of times. If you are not strong in such exercises, there will be a lot of irregularities. This line is a visual representation of how you experience awareness throughout the day. Living the moment consciously, you feel calm, focused and meaningful in your actions. Do not forget: even if you do not experience positive emotions, you still feel some emotional freedom, perspective, stability of sensations. However, like the line you drew on paper, the idea of constant awareness seems to many to be very shaky.

This dotted picture is a clear illustration of how engagement can become more than just a once-a-day meditative exercise. Take a blank sheet of paper and try to draw a straight line across the entire sheet. I think even if you have an excellent eye, your hand will still tremble a couple of times. If you are not strong in such exercises, there will be a lot of irregularities. This line is a visual representation of how you experience awareness throughout the day. Living the moment consciously, you feel calm, focused and meaningful in your actions. Do not forget: even if you do not experience positive emotions, you still feel some emotional freedom, perspective, stability of sensations. However, like the line you drew on paper, the idea of constant awareness seems to many to be very shaky.

“Try to think of mindfulness as a quality that you can use throughout the day. Remember that you should give yourself completely to every task, whatever it may be. However, then you realize that you have a normal working day ahead of you, and you become depressed.

You get out of bed, immediately trip over a cat and, cursing loudly, head to the bathroom. After breakfast, you already feel much better and think that, after all, the day is not so bad. But before you leave the house, you receive an email from your boss demanding that you work late today. “Of course, a little something - me!” you think. Leaving the apartment, you slam the door loudly, cursing to yourself.

When you get to the office, you find out that all employees, and not only you, have been asked to stay late at work, and you feel better. Then you see a large plate of cakes on the table. You smile, you are already drooling. “It must be someone’s birthday,” you think. “We should take a break and have some coffee.” But then the question of cakes begins to concern you seriously. You remember that you have been on a diet for quite a long time, which turned out to be very successful: in fact, should you eat these sweets? On the other hand, you are trying to learn to be kinder to yourself, maybe you should still allow yourself a single cake? You are completely confused.

You want cake... no, you don't want it. This is how day after day passes, and the events that take place are accompanied by a series of ups and downs for you. Throughout the day, only one thing stays the same: your own feelings determine your mood. In the absence of awareness and understanding, the power of feelings over you is limitless.

Well, now let's try to imagine what is happening differently. Imagine that a sheet of paper has already been marked with a series of small dots, stretching from one edge of the sheet to the other. Each point is located very close to the previous one. Imagine that you need to draw exactly the same straight line on this sheet. I think in this case the task will be much easier. When you draw a line on paper, you do not need to think about how to bring it to the edge, it is enough to focus on a distance of a couple of millimeters from one point to another. It turns out that drawing a straight line is not so difficult! If we continue the analogy with maintaining awareness and, consequently, emotional stability, this news will seem very inspiring to us.

Instead of trying to stay engaged during your daily ten minutes of morning meditation and then trying to stretch it out over the remaining twenty-three hours and fifty minutes until the next exercise, try to think of mindfulness as a quality that you can use throughout the day. Remember that you should give yourself completely to every task, whatever it may be. This means that in no case should you think about where you would prefer to be, what occupation attracts you the most at the moment, and generally dream that something in your life will change, that is, give up a habitual way of thinking that drives you into incessant stress. Instead, you should only think about what you are doing at the moment.

Thus, realizing that the working day begins, you should not fall into depression. All you have to do is to become aware of how you reacted to the truth revealed to you by watching the emotions arising from this realization arise and disappear. If you stumble over a cat, you shouldn't swear: it's better to bend over and make sure that everything is in order with the animal.

Think about your four-legged friend's health, not your own annoyance. Forgetting your disappointment, replacing it with a simple act of kindness, you will start the day in a new way. And then continue in the same spirit, moving from one task to another, filling each step with meaning, focus and understanding.

How to practice mindfulness and stop worrying

In any difficult times, the psychological state of people comes to the fore. One of the best practices for dealing with negative emotions is mindfulness. Understanding what it is and how to develop it

What is mindfulness

The last two years have been difficult: pandemic, lockdowns, economic crisis, military conflicts and political instability. People are constantly under pressure from notifications and news, workload, anxiety and sadness. In this state, the inertia of feelings and thoughts can be interrupted by awareness. This term refers to the concept of "mindfulness", which in a broad sense means the ability to calm down and plunge into what is happening right now.

It provides an opportunity to recognize anxiety or obsessive thoughts about the future and show kindness and compassion to yourself.

Diana Winston, director of mindfulness education at the University of California Psychological Research Center, emphasizes: “Mindfulness keeps us from getting lost in our thoughts, which can lead to more anxiety. We're trying to train our mind to be a little more stable." Winston recommends several easy practices to improve mindfulness.

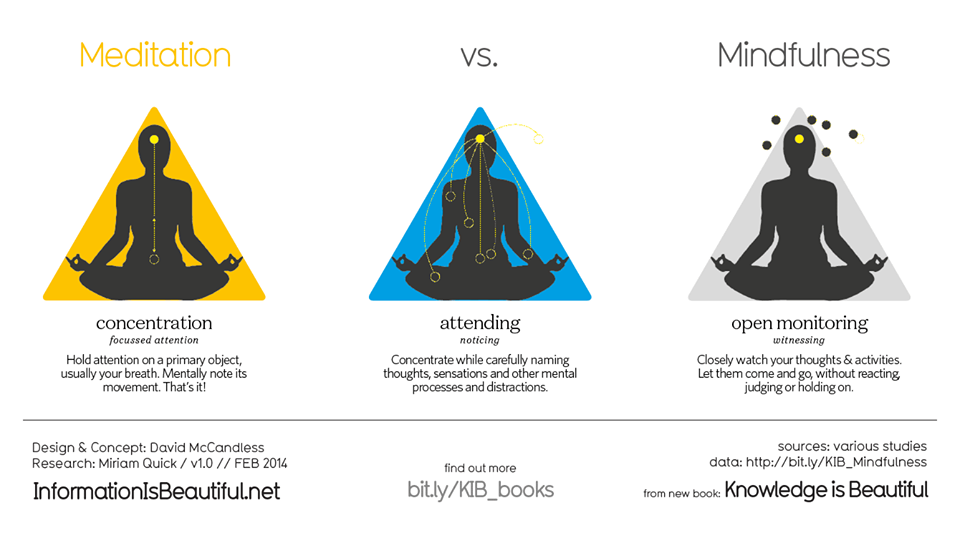

Mindfulness Meditation

The basis for developing mindfulness is meditation practice. It gives daily basis and structure. The easiest way to get started is to spend a few minutes in a place with little or no clutter. You can sit on a sofa or chair, close your eyes and take a moment to connect with yourself. Pay attention to your breathing.

Every time a thought distracts you, mentally examine it and then return to focusing on the breath. If following him is unpleasant or inconvenient, try to listen to the sounds around, to their appearance or attenuation.

For example, track the noise from a fan or an airplane flying in the distance.

Walking Meditation

If you don't like sitting meditation, don't worry, you're not alone. In that case, try walking meditation. Start by choosing a spot in your house or outdoors. Then walk no more than 100 meters and turn back. At the same time, carefully monitor the change in sensations in the feet and legs. Slow down, feel every step, try to notice even tiny muscle movements. If you get distracted, gently study the object that switched your thoughts, and then return to the fixation on walking again.

A long walk is more distracting, but it can also be used with this method. However, this kind of meditation is not for everyone. For some, anxiety or excitement awakens. If so, Winston recommends other activities that reduce distraction and help develop a more accurate connection to the present. It can be a walk in nature, sports, dancing or listening to music.

STAT: Stop, Breathe, Observe, Continue

Winston uses the abbreviation STAT to describe a "mini-mindfulness" exercise in which you suddenly stop everything you are doing, take a breath, observe how you feel, and then return to normal flow.

day. The whole process can take as little as 10 seconds. The bottom line is to fix what is happening in your body and thoughts at that moment. Focusing on the physical signs of stress, such as a racing heart or excessive sweating, develops mindfulness even better.

Combine mindfulness with repetitive actions

When mindfulness becomes a new habit, it is difficult at first to practice it throughout the day. Therefore, Winston recommends choosing one of the repetitive daily activities and turning it into a quick exercise. It can be an evening shower, brushing your teeth or opening the front door. Feel the hand turn the key and observe the accompanying sensations. Pay close attention to a simple action. Such a brief break can bring you back to the present moment and stop you from mentally checking your to-do list or thinking about what will happen later.

What if staying in the present moment is really hard?

Sometimes the present moment is terrible. Then it may be necessary to get angry and express those feelings.