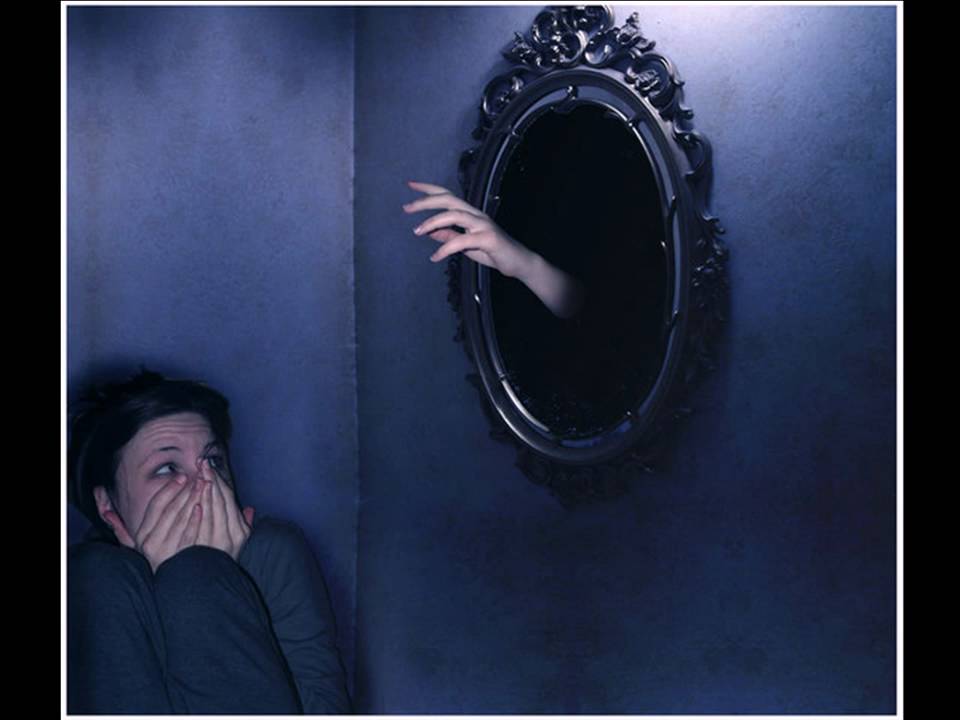

Fear of being possessed anxiety

You’re Not Alone — Outsmarting Anxiety & OCD

People with OCD typically struggle for 14-17 years before landing proper help. 14-17 YEARS! OCD creates all of these “what ifs” in our minds that often make us question reality. “What if I’m actually going crazy?” In our society, people commonly identify with OCD as if having it is a cool thing. We hear those around us talking about how “they are sooo OCD” because they like to be organized or wash their hands a tad more than the average person. Listening to others speak of OCD in such a nonchalant way can cause us to feel even more lonely.

What’s worse than people not getting it? People thinking they understand when they don’t. People passing OCD off as if it’s no big deal. I want to help end this misconception. I want people to better understand OCD themes so those who struggle and their families gain the respect they deserve for bearing this indescribable weight. Below are common OCD themes. Can you relate?

Contamination

Sure, people who struggle with contamination may wash their hands a lot or clean more often. But it is far more than that. It’s waking up every morning washing their hands until they feel just right. And feeling just right may not happen until hand wash #47, 55 minutes later, having to start over each wash if just one thing was out of order from the routine. Failing to wash their hands just right day after day results in bleeding hands and after the bleeding has stopped, looking raw and cracked. Fear of contamination results in taking scalding hot showers for 3 hours every morning and night to decontaminate. These folks often feel like they can’t go anywhere in public because they have no control over others. Just the thought of door handles, public bathrooms, or shaking people’s hands can send these folks into a panic attack. Sometimes, the fear of getting sick or passing an illness along to someone else is enough to send them into spiral.

Harm OCD

Harm OCD is not one that is commonly known, yet comes in a close second to the number of contamination cases I see. Why? Because these thoughts are not exactly ones that someone struggling is proud of, especially if they haven’t learned that these thoughts are a symptom of OCD. Harm thoughts often include thoughts of hurting a loved one, fear of stabbing Dad with a steak knife, fear of throwing a baby off a balcony. Even scarier yet, OCD makes you believe that the possibility of committing these horrendous acts of crime is just a matter of time before it happens. So folks struggling try to avoid anything that can remotely resemble a weapon or the person the thoughts are targeting. They even tend to avoid cutting up vegetables for dinner. They see horror video clips in their mind, where they can’t stop picturing murdering the person they care most about. Notably, people with Harm OCD are typically the sweetest people in the world. They are not actually going to harm a soul. How do I know? Well people who follow through on harmful acts are not those who panic at the very thought of following through. The people who harbor these thoughts are petrified by them, they hate every part of the experience, and sometimes they fear this possibility so much that it drives them to think that maybe the solution is harming themselves to avoid the possibility of harming someone else.

Why? Because these thoughts are not exactly ones that someone struggling is proud of, especially if they haven’t learned that these thoughts are a symptom of OCD. Harm thoughts often include thoughts of hurting a loved one, fear of stabbing Dad with a steak knife, fear of throwing a baby off a balcony. Even scarier yet, OCD makes you believe that the possibility of committing these horrendous acts of crime is just a matter of time before it happens. So folks struggling try to avoid anything that can remotely resemble a weapon or the person the thoughts are targeting. They even tend to avoid cutting up vegetables for dinner. They see horror video clips in their mind, where they can’t stop picturing murdering the person they care most about. Notably, people with Harm OCD are typically the sweetest people in the world. They are not actually going to harm a soul. How do I know? Well people who follow through on harmful acts are not those who panic at the very thought of following through. The people who harbor these thoughts are petrified by them, they hate every part of the experience, and sometimes they fear this possibility so much that it drives them to think that maybe the solution is harming themselves to avoid the possibility of harming someone else.

“Just Right” OCD

“It just doesn’t feel right.” Folks who experience this theme can’t explain why things don’t feel right to themselves or others. Things just need to feel right to them; otherwise, it feels like they need to do it over and over again until it feels “just so”. Unlike other OCD themes, “just right” doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with fearing something bad will happen. It just FEELS like you have to. Sometimes, hand washing can be mistaken for contamination OCD or for ordering/ symmetry OCD. “Just right” OCD has no logic to it’s thoughts. People who carry this theme may just be doing things over and over so they feel capable of moving on to other parts of their day. This person may feel incapable of getting to school or work on time. Maybe they even miss school or work entirely because they got caught up in a routine. “Just right” OCD stalls people’s daily lives until the “perfect” feeling arrives.

Scrupulosity (Religious or Moral OCD)

Scrupulosity is defined by a person experiencing moral or religious obsessions, typically causing them to feel like a terrible person. These individuals are overly concerned that they may act or have already acted in a sinful or morally obstructive way. They may experience excessive guilt or worry about whether or not they are following through on religious or moral teachings, being loyal to their higher power (e.g. God), blasphemy, sin, morality, right and wrong, thoughts of curse words, etc. They may feel the need to confess their thoughts, pray excessively, or repeatedly imagine sacred images or scripture in efforts to neutralize the thoughts. What’s most frustrating is that OCD targets this part of their life that is so highly valued. Worse yet, they cannot enjoy the religious or spiritual community due to the intrusive thoughts. Many times, it is helpful for therapists to speak with members of the clergy to gain a clear understanding of what is morally expected in their religious or spiritual community. Scrupulosity is often not in line with typical practices in their religion, causing significant confusion and distress.

These individuals are overly concerned that they may act or have already acted in a sinful or morally obstructive way. They may experience excessive guilt or worry about whether or not they are following through on religious or moral teachings, being loyal to their higher power (e.g. God), blasphemy, sin, morality, right and wrong, thoughts of curse words, etc. They may feel the need to confess their thoughts, pray excessively, or repeatedly imagine sacred images or scripture in efforts to neutralize the thoughts. What’s most frustrating is that OCD targets this part of their life that is so highly valued. Worse yet, they cannot enjoy the religious or spiritual community due to the intrusive thoughts. Many times, it is helpful for therapists to speak with members of the clergy to gain a clear understanding of what is morally expected in their religious or spiritual community. Scrupulosity is often not in line with typical practices in their religion, causing significant confusion and distress.

Relationship OCD

This type of OCD is INCREDIBLY frustrating to the person experiencing it. Oftentimes, a person in a very loving and committed relationship will begin to have doubts about whether or not they should be with their partner. It is hard to depict OCD thoughts from personal thoughts. Those who experience this may find themselves constantly and relentlessly checking in with themselves and their partner about the strength and value of the relationship. Folks may feel guilty about their uncertainty within the relationship so they confess to their partner. When OCD first begins to creep up, the sufferer’s partner often reassures them in their confidence regarding their relationship. As time goes on, partners become frustrated with the constant uncertainty and doubt about the OCD sufferer’s ability to commit, thus leaving the relationship in turmoil.

Order and symmetry

Everything has a place. Orders and systems are there for a reason. Rules have a purpose. For those with order and symmetry OCD, when things are out of place, anxiety spikes through the roof. Sometimes, magical thinking occurs where folks with this theme fear that if they do not keep to order or symmetry, something bad will happen. These individuals are fully aware that their fears are irrational, that one thing out of place does not cause harm to people they love. And yet, they can’t help but to abide by OCD’s made up rules just in case.

Rules have a purpose. For those with order and symmetry OCD, when things are out of place, anxiety spikes through the roof. Sometimes, magical thinking occurs where folks with this theme fear that if they do not keep to order or symmetry, something bad will happen. These individuals are fully aware that their fears are irrational, that one thing out of place does not cause harm to people they love. And yet, they can’t help but to abide by OCD’s made up rules just in case.

Unwanted sexual thoughts

This is as petrifying as it sounds. This may include incest, pedophilia, intrusive thoughts of being a different sexual orientation than you are or want to be, or any other intrusive sexual thought. One myth I want to bust right now is that people with unwanted sexual thoughts do not act on them. They live in constant fear because of them. Imagine loving your nephew and having thoughts of being sexually attracted to him. Imagine thoughts of having sex with your mom over and over. Imagine being happily married, yet having this excruciating doubt that you’re actually attracted to the opposite sex even when you’ve always been sure of your sexual orientation. A very common symptom of this type of OCD is frequently feeling sexually aroused when confronted with a trigger, which tricks sufferers even more so into believing the thoughts. I want people to know this is common and not indicative that the thoughts will come true. So what do people with this type of OCD do? They avoid, avoid, avoid as much as possible. They try to escape anything that triggers the thoughts to go off. They constantly check in with bodily sensations to ensure they do not feel aroused and consequently, may end up feeling unwanted arousal. They seek reassurance from others often and confess their thoughts or on the flip side, keep these thoughts secret for years. Their life becomes much smaller because soon enough, everything triggers them.

Imagine being happily married, yet having this excruciating doubt that you’re actually attracted to the opposite sex even when you’ve always been sure of your sexual orientation. A very common symptom of this type of OCD is frequently feeling sexually aroused when confronted with a trigger, which tricks sufferers even more so into believing the thoughts. I want people to know this is common and not indicative that the thoughts will come true. So what do people with this type of OCD do? They avoid, avoid, avoid as much as possible. They try to escape anything that triggers the thoughts to go off. They constantly check in with bodily sensations to ensure they do not feel aroused and consequently, may end up feeling unwanted arousal. They seek reassurance from others often and confess their thoughts or on the flip side, keep these thoughts secret for years. Their life becomes much smaller because soon enough, everything triggers them.

Obsessions related to perfectionism

Perfectionists often do well in school, in the workplace, with organization and order, and with making plans. All good qualities. When someone experiences OCD perfectionism, it most likely feels like success… until it feels debilitating. Perfectionism causes severe all or nothing thinking. People either want to complete the task at hand absolutely perfectly with no flaws in sight, but this requires checking upon checking, rewriting, rereading, redoing. It takes hours and hours, and it never actually feels perfect. Sooner or later, people find themselves feeling too overwhelmed to complete a task when trying to measure up next to “perfect”. It’s exhausting and feels impossible, so people stop trying altogether. A person’s bedroom may go from immaculately clean to a pig-sty. Students may go from having straight As to getting Ds and Fs on tests and assignments because it’s too draining to study or complete homework. Those working may stop completing projects or stay home from work altogether. The key is striving for excellence, not perfection, but for those with perfectionism OCD, it feels like an endless loop.

All good qualities. When someone experiences OCD perfectionism, it most likely feels like success… until it feels debilitating. Perfectionism causes severe all or nothing thinking. People either want to complete the task at hand absolutely perfectly with no flaws in sight, but this requires checking upon checking, rewriting, rereading, redoing. It takes hours and hours, and it never actually feels perfect. Sooner or later, people find themselves feeling too overwhelmed to complete a task when trying to measure up next to “perfect”. It’s exhausting and feels impossible, so people stop trying altogether. A person’s bedroom may go from immaculately clean to a pig-sty. Students may go from having straight As to getting Ds and Fs on tests and assignments because it’s too draining to study or complete homework. Those working may stop completing projects or stay home from work altogether. The key is striving for excellence, not perfection, but for those with perfectionism OCD, it feels like an endless loop.

Obsessive fears of losing control/ “going crazy”

Excessive fears about becoming possessed, having a psychotic break, becoming a mass murderer and enjoying it. All are intrusive thoughts under this theme’s umbrella. Folks experiencing this are terrified. They do everything possible to prevent their fears from occurring. These folks often check to make sure they are not seeing things. I’ve seen many avoid horror films, haunted houses, things related to halloween…not because they just aren’t interested. Because, “what if engaging in these activities increases my chances of going crazy?” Anything that reminds them of losing control in some way can cause mass amounts of anxiety.

Postpartum OCD

New moms and dads want nothing more than a healthy baby and to raise their child to be a respectful, happy, successful, and giving person. New parents dream of being able to come home from the hospital and spend joyous time with their family. Many of us have heard that this can be a struggle for some mothers. Postpartum anxiety and postpartum depression are struggles our society is familiar with, but postpartum OCD is not so widely known. This affects new mothers mostly, but new fathers can be affected too. Tormentingly, parents may have intrusive thoughts of hurting their baby, killing their baby, sexually abusing their baby, or emotionally damaging their baby. Due to how scary and real these thoughts may feel, parents avoid their newborn and then feel guilty for the disconnection. Imagine the guilt, shame, and distress during the precious first few months of a baby’s life.

Many of us have heard that this can be a struggle for some mothers. Postpartum anxiety and postpartum depression are struggles our society is familiar with, but postpartum OCD is not so widely known. This affects new mothers mostly, but new fathers can be affected too. Tormentingly, parents may have intrusive thoughts of hurting their baby, killing their baby, sexually abusing their baby, or emotionally damaging their baby. Due to how scary and real these thoughts may feel, parents avoid their newborn and then feel guilty for the disconnection. Imagine the guilt, shame, and distress during the precious first few months of a baby’s life.

Health OCD

It starts with one sensation in their body. Perhaps a few more pop up. The person with OCD begins to research on WebMD and strings together a diagnosis that reflects some symptoms they’ve had. The next thing they know, they are spending hours a day researching symptoms and searching for answers, excessively checking sensations in their body, asking for reassurance from everyone they are close to, especially their doctors. These folks may be afraid they have a serious illness or disease like cancer. Receiving confirmation from medical professionals that they do not have their feared illness is important, yet every time they get confirmation, it doesn’t feel like enough. Second, third, fourth, and fifth opinions feel needed. OCD convinces sufferers that it is FACT that something is wrong. And how petrifying does it sound to truly believe with all your heart that something is seriously wrong but the doctors can’t figure it out? These folks fear that if they cannot obtain certainty and confirmation from professionals, that something truly bad will happen.

These folks may be afraid they have a serious illness or disease like cancer. Receiving confirmation from medical professionals that they do not have their feared illness is important, yet every time they get confirmation, it doesn’t feel like enough. Second, third, fourth, and fifth opinions feel needed. OCD convinces sufferers that it is FACT that something is wrong. And how petrifying does it sound to truly believe with all your heart that something is seriously wrong but the doctors can’t figure it out? These folks fear that if they cannot obtain certainty and confirmation from professionals, that something truly bad will happen.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

I’m thinking that if you’ve read this, you either have OCD yourself, are generally an anxious person, or know someone you struggles with this beast. I hope reading these themes has helped you understand that OCD is far more complex than having to turn light switches on and off or washing your hands pretty often. OCD has the potential to ruin lives and unfortunately has so powerfully and negatively affected countless lives already. While it can take on different masks for those OCD affects, it can have similar negative impacts. OCD often affects the entire family. OCD draws in family members to participate in rituals and reassurance. It often ends up interfering with people’s ability to go to school or work. This illness affects appetite, sleep habits, energy levels, and after suffering for awhile, people with OCD may also be affected by depression as well. Those with OCD may retreat from social events or spending time with friends and relationships altogether. When severe, it has caused people to stay bed or house ridden.

OCD has the potential to ruin lives and unfortunately has so powerfully and negatively affected countless lives already. While it can take on different masks for those OCD affects, it can have similar negative impacts. OCD often affects the entire family. OCD draws in family members to participate in rituals and reassurance. It often ends up interfering with people’s ability to go to school or work. This illness affects appetite, sleep habits, energy levels, and after suffering for awhile, people with OCD may also be affected by depression as well. Those with OCD may retreat from social events or spending time with friends and relationships altogether. When severe, it has caused people to stay bed or house ridden.

If you know anyone else who can benefit from learning a bit more, please share this with them. I’ve had way too many clients tell me that they’ve had these symptoms for years and years not knowing what it was or what to do about it. So let’s help everyone we can get connected with knowledge and help as soon as possible.

OCD and Anxiety Clinic of Ontario

When we speak about scrupulosity, we tend to speak about the obsessions and compulsions that individuals with OCD have that pertain to religious themes, hyper-morality, pathological doubt/worry about possible sin, and excessive religious behaviour (Witzing 2020). There are many mental and behavioural compulsions that OCD sufferers use to cope with their religious obsessions. The mental compulsions may begin with overanalyzing and attempting to understand how to convince oneself that sin is forgivable (Grayson 2014). Other attempts may include thinking the sin is not a sin at all.

Typically, the symptoms usually revolve around moral and religious teachings of a particular religious group. This means that OCD suffers may focus their attention to themes related to situations that they ‘shouldn’t’ be doing, such as lying or being impure. Some themes may include blasphemy, sex, violence, and being pure. Some OCD sufferers may resonate with feeling of disgust with the intrusive thought (for example, the thought of having sex with god). They may judge themselves for having these thoughts, which in turn creates more of a downward spiral of despair and worry. They may even obsess about the content of the thought and further self-criticize. At times, people may think of these thoughts as an act of god or a demonic possession. Sometimes OCD sufferers may also just accept their thoughts without questioning them. Accepting them as completely valid may likely lead to further questioning (e.g. am I really at peace with god?). Thoughts like this, may spur obsessional rumination (thinking about the thought over and over).

They may judge themselves for having these thoughts, which in turn creates more of a downward spiral of despair and worry. They may even obsess about the content of the thought and further self-criticize. At times, people may think of these thoughts as an act of god or a demonic possession. Sometimes OCD sufferers may also just accept their thoughts without questioning them. Accepting them as completely valid may likely lead to further questioning (e.g. am I really at peace with god?). Thoughts like this, may spur obsessional rumination (thinking about the thought over and over).

According to Purdon & Clark’s text, Overcoming Obsessive Thoughts, there is no evidence that religion may cause obsessive compulsive disorder. What we are aware of is that your religious experience may influence the type of obsessions that you have (Witzing 2020). Sally Winston in her text, Overcoming Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts, argues, “the thoughts that you don’t want to have are the ones that get stuck…these are thoughts you fight- and because you fight them, they stick. If you are someone with strong religious beliefs, you sometimes come up with blasphemous thoughts.” She indicates that the thoughts you don’t want are neutral and the thoughts you care so much about are often likely stuck because you value them so highly (Winston 2019).

If you are someone with strong religious beliefs, you sometimes come up with blasphemous thoughts.” She indicates that the thoughts you don’t want are neutral and the thoughts you care so much about are often likely stuck because you value them so highly (Winston 2019).

Many OCD sufferers may believe that searching through faith will provide them with certainty. This may mean overanalyzing scriptures or passages or seeking guidance from religious leaders. In a lecture presented by Witzing in 2020, he argued that faith does not equal certainty, but rather faith is trusting god through the uncertainty. OCD tends to latch on to the doubt and it wants you to believe that uncertainty and doubt are dangerous (Witzing 2020). What we want to help our clients realize is that uncertainty is tolerable. He argues that faith is what you believe and not what you feel. He argues that your feelings are not facts.

Part of acceptance and commitment therapy is practicing your faith despite not knowing what the end result will be (e. g. being punished). This means that if you have sinned then we need to practice acceptance and moving on. Witzing states “if you wonder if you have sinned (e.g., ‘what if I…?’) or aren’t sure if you have, then you need to move on and go forward as if you didn’t (Witzing 2020). Keep moving forward.” Those who seek to recover would have to embrace exposure and response prevention combined with acceptance and commitment therapy. At no point during treatment would your religious beliefs be violated or undermine your faith. If you would like to find out more about our program, please feel free to contact us. We would be glad to provide more information.

g. being punished). This means that if you have sinned then we need to practice acceptance and moving on. Witzing states “if you wonder if you have sinned (e.g., ‘what if I…?’) or aren’t sure if you have, then you need to move on and go forward as if you didn’t (Witzing 2020). Keep moving forward.” Those who seek to recover would have to embrace exposure and response prevention combined with acceptance and commitment therapy. At no point during treatment would your religious beliefs be violated or undermine your faith. If you would like to find out more about our program, please feel free to contact us. We would be glad to provide more information.

Witzing, Ted, OCD Conference, IOCDF, 2020.

Grayson, Jon. Freedom for OCD, Berkley Publishing, 2014.

Winston, Sally. Overcoming Obsessive Unwanted Thoughts, New Harbinger Publications, 2019.

The Age of Anxiety: How We Became Obsessed with Security

In an effort to prevent possible dangers, we - as individuals and as a society - can literally deprive ourselves of the future. How to face your fears, understand the nature of their occurrence, tells the book by Frank Faranda "The Paradox of Fear", which was published by Alpina Non-Fiction

How to face your fears, understand the nature of their occurrence, tells the book by Frank Faranda "The Paradox of Fear", which was published by Alpina Non-Fiction

Last summer, I again experienced a long-forgotten pleasure - riding the waves . I'm not talking about small scallops that are easy to tame, but about the waves that imprint you in the sand and drag you about twenty meters. These are the ones I encountered one early evening at Marconi Beach on Cape Cod, tumbling in the waves with my twelve-year-old son.

The waves on the Marconi coast were already familiar to me. In my twenties, I spent summers on Cape Cod and rode them many times. In those days I was much stronger, but even now, when I returned here at a more mature age, I was seized by the same delight. To my surprise, my son also decided to enter the water. He usually doesn't like riding the waves, but I think he decided to join in the fun. There were people from ten to sixty years old, overwhelmed with delight. I didn't fully realize then that the pleasure I feel riding these waves is due to the proximity of danger, but in hindsight I believe it was.

I didn't fully realize then that the pleasure I feel riding these waves is due to the proximity of danger, but in hindsight I believe it was.

My son and I were blissful. We rode about six waves each, when suddenly, glancing in the direction of the horizon, we saw that a huge wave was swelling there. Along with the shaft came such a powerful rollback that it became difficult to move. I looked at my son - he was getting ready to ride the wave. I dived into the wave that hit me and rode it to the beach. She was huge and threw me out with force. When I managed to get up and look around, I saw my wife standing on the beach, pointing at her son. Her words slowly entered my mind: "He's in pain!" She was pointing at something, and I was trying to brush the water out of my eyes to focus my vision. I looked at my son. He stood holding one of his hands with the other. It was then that I saw: the arm was bent at the elbow, but in the wrong direction. I ran up to him and saw a swelling on his elbow. On the face - pain, fear. My excitement turned sour in my stomach, and then I only plunged step by step into a fog of despair and horror.

On the face - pain, fear. My excitement turned sour in my stomach, and then I only plunged step by step into a fog of despair and horror.

A huge part of our resources, personal and medical, is spent on correcting and eliminating the consequences of anxiety and its root cause - fear.

The arm ended up without surgery, and after two difficult months of recovery, the son was healthy again. In the months that followed, my wife and I spoke to him repeatedly about what had happened and how he felt. The only emotion I never admitted was the joy I experienced before the last wave hit. It seemed wrong to associate joy with such a frightening experience. I could not even think of discussing this with my wife, and even more so with my son. However, about a year later, when we were in the car together, the topic surfaced. I don't remember what prompted it, but it just happened. I confessed that riding those waves gave me a joy that I had not experienced in a very long time. We stopped at a traffic light, and I looked back at it anxiously. He turned to meet my eyes. A smile slowly formed on his face and he nodded, “I know. Me too". That's all. Nothing more needed to be said. Although we both knew how that day ended, we could not deny the previous elation. Unfortunately, joy has brought us too close to danger. But why did this happen? Why does joy often overwhelm us when we come close to the border of fear?

We stopped at a traffic light, and I looked back at it anxiously. He turned to meet my eyes. A smile slowly formed on his face and he nodded, “I know. Me too". That's all. Nothing more needed to be said. Although we both knew how that day ended, we could not deny the previous elation. Unfortunately, joy has brought us too close to danger. But why did this happen? Why does joy often overwhelm us when we come close to the border of fear?

As humans, fear is a complex, multilevel phenomenon. I began to study it largely because I wanted to uncover these secrets - both for myself and for my patients. As a psychologist, I listened every day to stories about the suffering caused by fear, and I began to understand that fear is a much more devastating feeling than I thought.

Modern paranoia. How fear became our constant companion

Unlike the fears of other animals, human fear takes on strange forms and proportions. Something about the being we evolved into radically changed the role of fear in life, not only in the personal, but also in the historical and social aspects. For us, fear is often no longer a reliable ally in the struggle for survival, as for other animals, but something that we protect ourselves from.

Something about the being we evolved into radically changed the role of fear in life, not only in the personal, but also in the historical and social aspects. For us, fear is often no longer a reliable ally in the struggle for survival, as for other animals, but something that we protect ourselves from.

In 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt warned us about fear. He delivered the now famous words in his first inaugural address to a nation paralyzed by despair and yearning for hope. Recovery from the economic collapse of the city stalled, and Roosevelt knew that in order to get out of the economic quagmire, the country must recognize the emotional underpinnings of this collapse. Roosevelt understood that fear played an important role in both despair and recovery potential. He knew that fear was crippling and destructive at times, even if the sense of impending danger was ultimately irrational. Roosevelt very eloquently described this when he said: “...Let me express my firm conviction that the only thing we should be afraid of is fear itself, nameless, reckless, causeless horror, paralyzing the efforts necessary to turn a retreat into an offensive. ".

".

The paralysis that Roosevelt spoke of has been experienced by most of us at some point in our lives. It is from this that countless self-help books try to free us. However, I was interested in the question: why, in principle, fear is such a serious problem for us and why we, Homo sapiens, have become so different from other animals in this respect. To answer these questions, I first looked at my patients. From this began a long journey, deeply immersing me in the history of the formation of today's man. Neuroscience, history, sociology, evolutionary biology, cognitive science, psychoanalysis, and comparative psychology are all involved in this study. The main question of this book is not “what to do with it?” but “how did it happen?”.

The inner watchman: when to listen to your own fear and intuition

The same scene plays out every day on every corner. I have watched her many times. A child of one or two years old tramples on the sidewalk. A mother is waiting nearby with an empty stroller, obviously ready to return home. She already said ten times: “Come on, we have to go, we need to go ... well, let's go?” Finally, like a bolt from the blue, the frightening words: "I'm leaving." Just two simple words with their unforgettable eerie melody: "I'm leaving." The child instantly freezes, turns around and looks at the mother, who takes the first step away from him. Without the slightest delay, the child cries out: “No! Wait!" - and runs to her, frightened, pitiful, obedient.

A child of one or two years old tramples on the sidewalk. A mother is waiting nearby with an empty stroller, obviously ready to return home. She already said ten times: “Come on, we have to go, we need to go ... well, let's go?” Finally, like a bolt from the blue, the frightening words: "I'm leaving." Just two simple words with their unforgettable eerie melody: "I'm leaving." The child instantly freezes, turns around and looks at the mother, who takes the first step away from him. Without the slightest delay, the child cries out: “No! Wait!" - and runs to her, frightened, pitiful, obedient.

Around this pivotal experience of uncertainty that comes to us very early in brief moments of fear in relationships, not only our personal psychology, but the very fabric of our society is formed. So much so that such great thinkers as Alan Watts and Paul Tillich have called our time an age of anxiety.

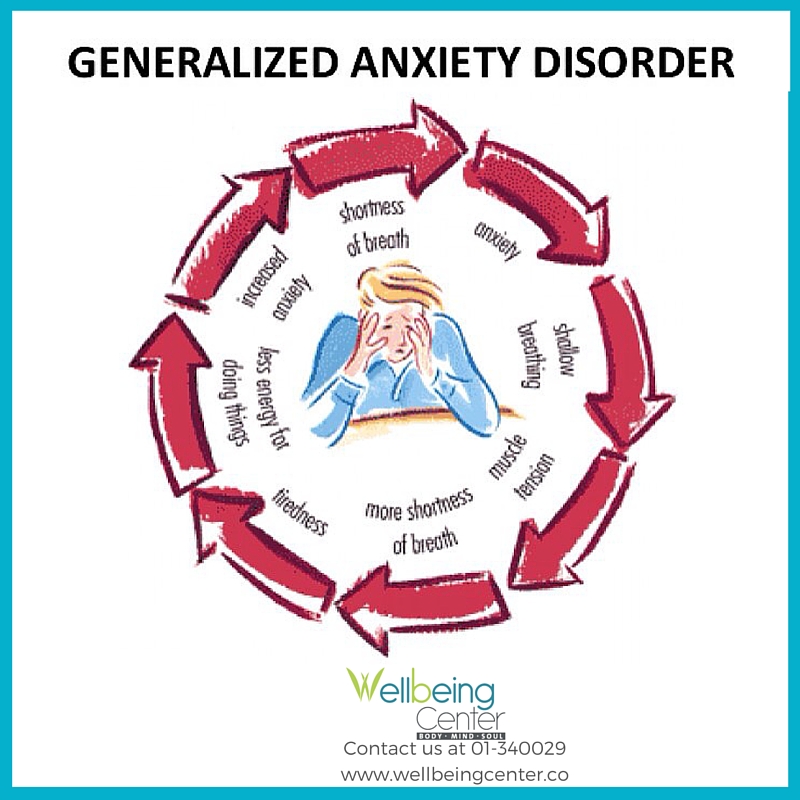

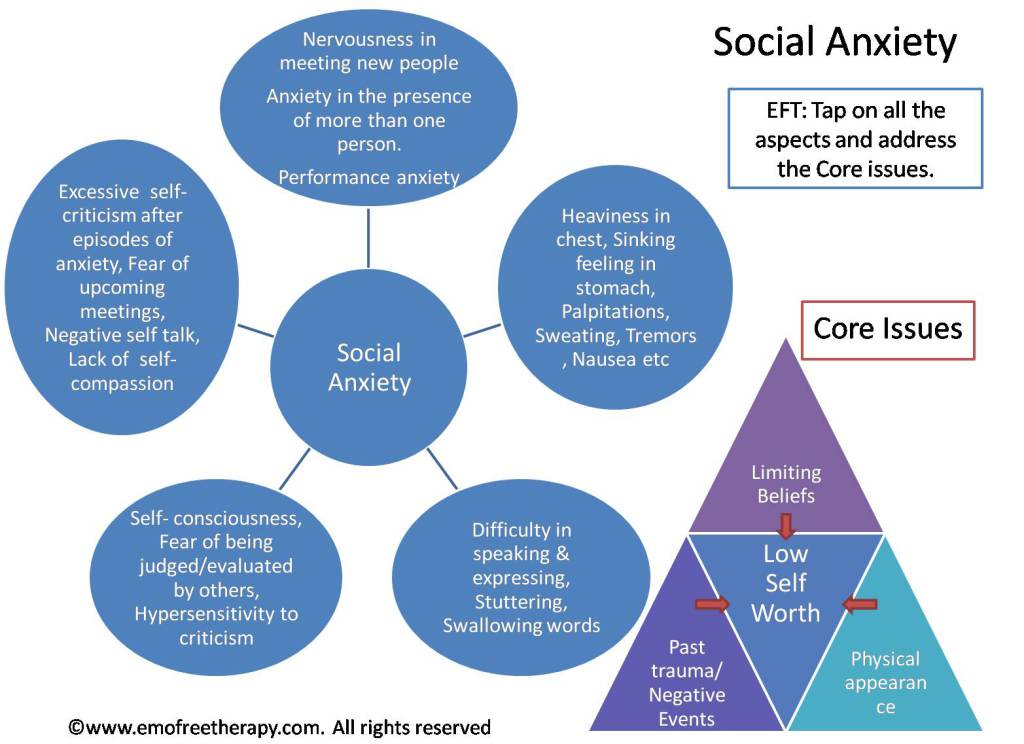

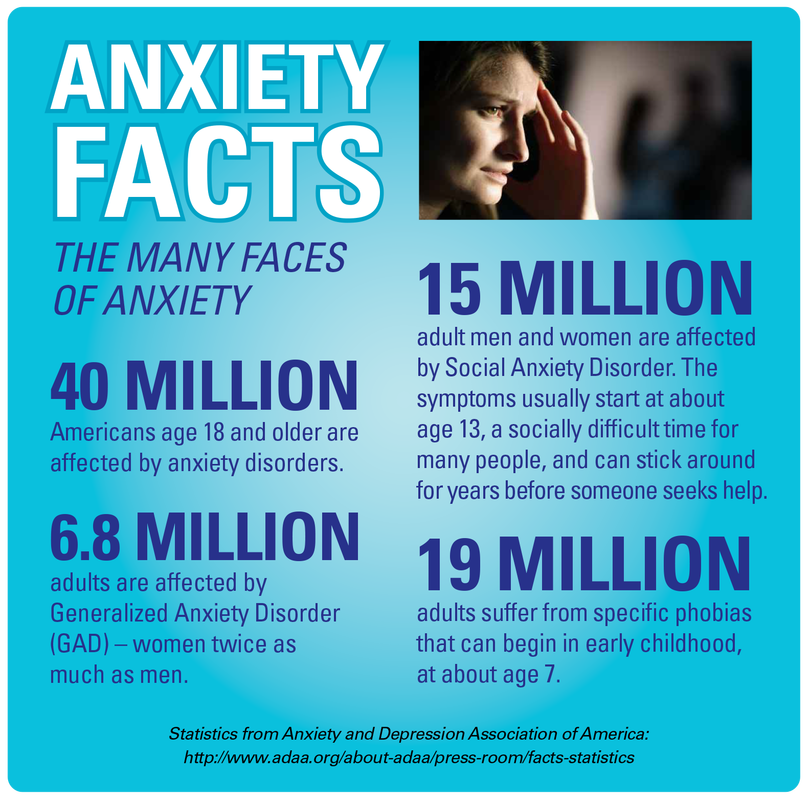

It is estimated that more than 50 million Americans aged 18 to 50, or 19% of the adult population, will be diagnosed with some form of anxiety disorder within a year of their lives. These statistics include generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, phobias, including social phobia and agoraphobia, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This proportion, already significant, approaches 31% when considering lifetime statistics. In my opinion, these are almost epidemic indicators. When you consider how many of us suffer from high levels of anxiety but fall short of diagnostic criteria, the data is even more staggering.

These statistics include generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, phobias, including social phobia and agoraphobia, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This proportion, already significant, approaches 31% when considering lifetime statistics. In my opinion, these are almost epidemic indicators. When you consider how many of us suffer from high levels of anxiety but fall short of diagnostic criteria, the data is even more staggering.

Obviously, a huge part of our resources, personal and medical, is spent on correcting and eliminating the consequences of anxiety and its root cause - fear. Hospital emergency rooms are overflowing with patients with panic disorder who mistakenly think they are having a heart attack, and the pharmaceutical industry is getting rich on drugs for generalized anxiety.

In addition to these symptoms and costs, there is a less obvious but more detrimental effect that plagues so many of us. Many areas of our life are inaccessible to us because of this fearfulness: our freedom is limited, well-being is undermined, we lose the ability to realize ourselves - to become ourselves or what we want to become. As we will see shortly, one of the particularly unpleasant aspects of fear is its amazing ability to operate in us imperceptibly.

Many areas of our life are inaccessible to us because of this fearfulness: our freedom is limited, well-being is undermined, we lose the ability to realize ourselves - to become ourselves or what we want to become. As we will see shortly, one of the particularly unpleasant aspects of fear is its amazing ability to operate in us imperceptibly.

I observed this effect of fear in one of my patients, I will call him Tim. When we first met, Tim looked quite prosperous. He was satisfied with his job and was in a serious relationship with a woman he liked; their only conflict was over his lack of ambition. Unlike his girlfriend, Tim was happy with everything, he did not pursue career opportunities and did not look for ways of self-expression - neither personal nor professional. This difference became a source of conflict between them - so serious that a friend took his word to see a psychotherapist and figure out "what's wrong with him."

The Inner Monkey: How Humans Learned to Show Power from Animals

I value creativity and ambition, but I don't think everyone should strive for it. In my opinion, there is nothing pathological about living your modest life quietly and calmly. This, however, is not the same as taking the path of least resistance out of fear.

In my opinion, there is nothing pathological about living your modest life quietly and calmly. This, however, is not the same as taking the path of least resistance out of fear.

All I knew about Tim at that time was that he was not interested in career growth. Tim specifically emphasized in a conversation with me that if he felt such a desire, he would pursue this goal, that is, it is not fear that holds him back - it's all about unwillingness. He said, “What do you want me to do? I just don't want it."

We settled on that until one day Tim admitted to me that he hadn't cried in fifteen years. A wave of sadness and compassion washed over me. He said he forbade himself to cry and it worked. The last time he cried was after a humiliating incident with a girl in high school. Having given time to his pain, we found out that, having stopped his feelings of resentment, he at the same time deprived himself of his desires. It was desire that seemed to get him into trouble. That part of him that sought to protect Tim from future emotional wounds consistently forced him to give up all desires. Fear of resentment, humiliation and pain created a very special protection. This defense remained completely unconscious and, acting invisibly, was extremely effective.

That part of him that sought to protect Tim from future emotional wounds consistently forced him to give up all desires. Fear of resentment, humiliation and pain created a very special protection. This defense remained completely unconscious and, acting invisibly, was extremely effective.

Given the pernicious prevalence of fear in our society, it is perhaps not surprising that we fight fear on all fronts. Personal growth gurus and self-help writers have developed countless systems and programs to overcome vulnerability to fear and anxiety. In every possible way, these guides to the world of personal growth help their clients and readers to face fear and make choices in favor of a whole range of needs, not limited to the need for security.

One of the most unpleasant aspects of fear is its amazing ability to work in us imperceptibly.

Think of Oprah and her walking on hot coals. Although ember walking has been incorporated into the New Age movement, it goes back thousands of years. Similar rituals are woven into Western cultures, from ancient Greece to the United States. Regardless of the physiological component of this phenomenon (which makes it accessible to humans), walking on coals is a ritualized experience that gives the participant a new sense of power over their fear. After walking on hot coals, people report a surge of vitality and a surge in freedom of expression. However, this upgrade is rarely long-term.

Although ember walking has been incorporated into the New Age movement, it goes back thousands of years. Similar rituals are woven into Western cultures, from ancient Greece to the United States. Regardless of the physiological component of this phenomenon (which makes it accessible to humans), walking on coals is a ritualized experience that gives the participant a new sense of power over their fear. After walking on hot coals, people report a surge of vitality and a surge in freedom of expression. However, this upgrade is rarely long-term.

Culture has a variety of forms and ways to temporarily neutralize fears: from feeling proud, when our valor is rewarded with a medal pinned to our chest, to reading books that are in bookstores (both regular and online) in the section “Self-development literature”. The sheer abundance of such publications betrays our passion for courage and fear. Thousands of books annually promise us this relief. If there is one thing that all these books agree on, it is the belief that fear is the cause of the loss of vitality, as well as the lack of self-realization. One gets the impression that overcoming fear is an almost universal tool in Western society. Emmerson himself proclaimed this the recipe for a good life. He wrote: “He has not learned the lesson of life who has not overcome fear every day.” Fearlessness is a commodity we all value. Since the Marjorie Stoneman Douglas school shooting, we have seen firsthand the hideous power of fear to turn a person into a trembling lump. The sight of Officer Scott Peterson, a distinguished officer of the sheriff's department, frozen in front of the entrance to the school where children were being killed at the time was shockingly shameful and at the same time painfully understandable.

One gets the impression that overcoming fear is an almost universal tool in Western society. Emmerson himself proclaimed this the recipe for a good life. He wrote: “He has not learned the lesson of life who has not overcome fear every day.” Fearlessness is a commodity we all value. Since the Marjorie Stoneman Douglas school shooting, we have seen firsthand the hideous power of fear to turn a person into a trembling lump. The sight of Officer Scott Peterson, a distinguished officer of the sheriff's department, frozen in front of the entrance to the school where children were being killed at the time was shockingly shameful and at the same time painfully understandable.

In courage and its absence, I am not so much interested in questions about whether it helps to overcome fear or whether it can be developed in oneself, but about why we need it so much. Why has our culture, and countless ones that preceded it, created so many rituals to promote courage? Courage seems to be a bit like a winter coat: it may look quite attractive, but we certainly wouldn't have it if it wasn't for this damn cold. What in fear requires such decisive countermeasures? Isn't the purpose of fear to warn us of danger? Why has fear, critical to our survival, evolved into such a serious threat to us?

What in fear requires such decisive countermeasures? Isn't the purpose of fear to warn us of danger? Why has fear, critical to our survival, evolved into such a serious threat to us?

13 ideas for the weekend: what successful people do in their free time

13 photos

Paradox of fear. How an obsession with safety prevents us from living - analytical portal POLIT.RU How the obsession with security prevents us from living” (translated by Natalia Kolpakova).

The book presents a clinical psychologist's view of the place of fear in human evolution. Frank Faranda shows that most of our technological and social innovations are simply increasingly ingenious ways to escape from danger. However, no matter how many dangers, real or imagined, we neutralize, new ones come in their place. And the desire to get rid of these dangers turns into a source of constant stress and anxiety. For years, Dr. Frank Faranda has studied the state of fear in his patients, which has steadily led them to avoidance, alienation, overcontrol, and ultimately depression and anxiety. He began to wonder what they were afraid of and how rooted those fears might be in today's society. According to Frank Faranda, while fear is paramount to keep people safe and comfortable, it has become the greatest threat to humanity and collective survival. As a consequence, fear has become ingrained in our culture, creating new dangers and provoking isolation. With anxiety levels on the rise, it's time to shed light on our deepest fears and examine the society that creates fear.

He began to wonder what they were afraid of and how rooted those fears might be in today's society. According to Frank Faranda, while fear is paramount to keep people safe and comfortable, it has become the greatest threat to humanity and collective survival. As a consequence, fear has become ingrained in our culture, creating new dangers and provoking isolation. With anxiety levels on the rise, it's time to shed light on our deepest fears and examine the society that creates fear.

We offer you to read a fragment of the book.

The birth of fear

Human babies come into the world completely helpless. We depend on our caregivers not only for protection and physiological needs, but also for our psychological development. This is our difference from other animals. In what follows, we will take a closer look at how evolution has made us the way we are, but for now, suffice it to say that Homo sapiens is much more dependent on the world than other animals, including our primate relatives. Coming into the world in such a vulnerable state opens the way for a whole range of potential psychological problems. At the same time, our vulnerability and addiction often do not make themselves felt - except when something goes wrong.

Coming into the world in such a vulnerable state opens the way for a whole range of potential psychological problems. At the same time, our vulnerability and addiction often do not make themselves felt - except when something goes wrong.

After the bombing of London during World War II, many babies and older children were orphaned and placed in the London Foundling Hospital. At that time, the Austro-American physician and psychoanalyst René Spitz worked there. At first, Spitz was struck by the silence in the children's room of the hospital: although the many crumbs under the age of one were abandoned and alone, none of them cried. Spitz began to study these children - and became a pioneer in the world of children's needs and the importance of motherly love.

Spitz understood what happens to a baby who systematically lacks love. Complete neglect, similar to what these children experienced for many months, turned them into empty shells of human beings. The doctor called this condition anaclitic[1] depression - a depression that develops in the first year of life due to separation from the mother, giving the infant warmth, tactile contact, a sense of security.

To get a better idea of what these withered babies were like, I suggest you google a video about Ren Spitz and the "Foundation Home Babies". You will see that the life force in these little people has retreated into some secret depths, leaving darkness and desolation on the surface. These neglected babies no longer need the outside world, and no outside effort seems to be able to reach them.

It's not hard to see some similarity to April's struggle: if the world is too dangerous, the only reaction is to run. If physical escape is not possible, then isn't it wonderful that our nervous system finds a way to retreat to cover when physically present? Of course, these babies were far more unlucky than April. Extreme forms of deprivation, such as they experienced, are difficult to compensate for. What is common, however, is that from the very first moments of life, our well-being is in the hands of others. If other people do not bring us love and care, we suffer deeply. We have an addiction from which there is no safe escape.

One of the wonders of child development is the ability of children to remain attuned to their caregivers, no matter what happens to them. Not only are we biologically programmed to maintain physical closeness with those who care for us - this aspect we call "attachment" - human attachment is also psychologically programmed to love and trust our parents. If something “bad” happens to a child in the arms of a parent, the blame is not placed on the parent. Children's logic is simple: "If I'm good, they give me candy, and if they didn't, then I'm bad." Psychoanalyst Ronald Fairbairn, an early follower of René Spitz, called it a moral defense. Children assign moral superiority to their parents. If the parent's actions cause pain or the child fails to get what he needs, then he blames it not on the parent, but on himself: "So I deserve it." In this way, the child manages to maintain a stronger bond with the caregiver. By taking “blame” on themselves, the child reinforces the perception of the parent as good, because this makes it easier to maintain a connection with him. It's hard to love a bad parent. It's easier to be bad yourself and love the good.

It's hard to love a bad parent. It's easier to be bad yourself and love the good.

I want to emphasize that we have developed ways to keep in touch even when the parent is extremely dysfunctional. This is both amazing from the point of view of evolutionary engineering - and extremely sad from the human. Very often, those who should be protecting us are the biggest threat to us; childhood, meant to be a time of play, becomes the perfect petri dish for growing fear.

Play is important

In the animal world, there are significant relationships between play, fear and vitality. Studies of animals as diverse as turtles and rats show that the lack of play in an animal's life puts its well-being at risk. In humans, there is additional evidence that lack or limitation of play is associated with increased levels of psychological dysfunction. And when we look at the factors that limit the game, we find that the first among them is fear.

In a series of studies, researchers looked at the background of men serving time for murder. Two facts attracted particular attention. Significantly more physical violence was observed in the group of killers than in the control group - and the companion of violence is fear. More surprising, however, was the striking lack of reports of childhood play in this group.

Two facts attracted particular attention. Significantly more physical violence was observed in the group of killers than in the control group - and the companion of violence is fear. More surprising, however, was the striking lack of reports of childhood play in this group.

Research leader Stuart Brown subsequently learned of the work of primatologist Jane Goodall: he was intrigued by a 1976 report about a pair of chimps, Passion and Pom, mother and daughter, who systematically killed and ate the newborn chimpanzees in their group. Brown contacted Goodall to talk about his findings. And she informed him that both Passion and Pom had indifferent mothers and at a young age showed a huge deformation of play behavior.

The interpretation of these curious discoveries requires maximum accuracy. The mere correlation between lack of play and homicidal tendencies in no way proves their causal relationship. However, for now, it is useful for us to note the importance of play in the life of mammals and to think further about what makes play part of the much larger whole within which we build our relationship with fear.

Play and risk

In the young of most animals, play is predominantly of a hard-contact nature. For humans, such "cruel" games are just one of a wide range of games, including games with objects, and symbolic/fantasy games, and brawls, and games by the rules. A risk game associated with "cruelty" is usually understood as any game in which the participants come extremely close to the brink of danger. It was this experience that I talked about in the introduction when I described riding the waves with my son. Such games are often divided into high-altitude play, play near dangerous objects, and play with speed. We climb a tree to the thinnest branch that can support our weight, walk along the edge of a narrow ledge, play with fire, or accelerate our bike downhill and let go of the handlebars.

The study of this type of play contributed to the understanding of how to keep children safe and defined childhood policy. Recent trends have led our families and communities to drastically reduce any activity that can be seen as a potential risk to children. This is largely due to increased supervision - and as we all know from our own childhood, the more supervision, the less fun. However, greater safety is also the result of the invention of new outdoor play equipment, where the hard contact with metal and concrete, as was the case in the past, has been replaced by a resilient coating that provides a softer landing.

This is largely due to increased supervision - and as we all know from our own childhood, the more supervision, the less fun. However, greater safety is also the result of the invention of new outdoor play equipment, where the hard contact with metal and concrete, as was the case in the past, has been replaced by a resilient coating that provides a softer landing.

A recent study by Scott Cook of the University of Missouri attempted to analyze not only what children do during risky play, but also how they feel. In this work, risky play is considered, on the one hand, as a result of inadequate risk assessment, an attempt to attract attention or an impulse of self-harm. On the other hand, it has been shown to provide a developmental arousal experience of emotional and biological value to the growing child. This approach is reinforced by research on neurodevelopment in children, revealing distinct areas of the brain that are stimulated by risky behavior.

In a risky game, an important point is made: there is a line between safety and danger that causes the highest excitement. Recall the case with my son: when he looked back and saw that the resulting wave was much larger than the previous six, on which we rode, he froze. The balance of security and threat has been upset. He was overcome with fear, but he overcame it. Unfortunately, the wave was too big for him. The only way to survive this wave was to playfully submit to it.

Recall the case with my son: when he looked back and saw that the resulting wave was much larger than the previous six, on which we rode, he froze. The balance of security and threat has been upset. He was overcome with fear, but he overcame it. Unfortunately, the wave was too big for him. The only way to survive this wave was to playfully submit to it.

Fear affects play as a limiter, and yet a dangerous game, play on the edge of fear, brings its evolutionary derivative - joy. Why did evolution mix this strange cocktail? To help us, to teach us how to deal with fear more easily? Is this an attempt to lessen our innate terror by giving us a sense of power over fear? Or is it her gift to us - the joy that comes when you manage to free yourself from fear?

Our animal cousins give us a hint, more specifically, how they use tough brawling games. Brawling consists of the wallowing, wrestling, biting and pinching that we see in animals, from mice and puppies to humans. The first interpretations of such a game emphasized its value as a teaching tool. This is a game battle model, a kind of preparation for real battles. Today's interpretations of game fights put the concept of relationship learning at the forefront. What stands out in these theories is the idea that, through brawling play, animals learn to flexibly adapt to unpredictable situations.0019 social conditions , accept the change of social roles. In role reversal, stress and fear are brought under control in safe situations. In addition, social roles are strung on an axis of social dominance. In the brawl game, the cubs learn to accept both a subordinate and a dominant position.

This is a game battle model, a kind of preparation for real battles. Today's interpretations of game fights put the concept of relationship learning at the forefront. What stands out in these theories is the idea that, through brawling play, animals learn to flexibly adapt to unpredictable situations.0019 social conditions , accept the change of social roles. In role reversal, stress and fear are brought under control in safe situations. In addition, social roles are strung on an axis of social dominance. In the brawl game, the cubs learn to accept both a subordinate and a dominant position.

It is this last element that I consider the most essential for understanding the connection between gambling and fear. There seems to be something very important about our relationship to submission—perhaps so important that this behavior (the play of dominance and submission) is built into the DNA of mammals, including us. As we shall see, the fear of alien domination is so terrible for an individual of our species that we are ready to do anything to avoid it.